Abstract

Enchondromas are a common tumor in bone that can occur as multiple lesions in enchondromatosis, which is associated with deformity of the affected bone. These lesions harbor somatic mutations in IDH and driving expression of a mutant Idh1 in Col2 expressing cells in mice causes an enchondromatosis phenotype. Here we compared growth plates from E18.5 mice expressing a mutant Idh1 with control littermates using single cell RNA sequencing. Data from Col2 expressing cells were analysed using UMAP and RNA pseudo-time analyses. A unique cluster of cells was identified in the mutant growth plates that expressed genes known to be upregulated in enchondromas. There was also a cluster of cells that was underrepresented in the mutant growth plates that expressed genes known to be important in longitudinal bone growth. Immunofluorescence showed that the genes from the unique cluster identified in the mutant growth plates were expressed in multiple growth plate anatomic zones, and pseudo-time analysis also suggested these cells could arise from multiple growth plate chondrocyte subpopulations. This data supports the notion that a subpopulation of chondrocytes become enchondromas at the expense of contributing to longitudinal growth.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-76539-y.

Subject terms: Mechanisms of disease, Cancer, Cartilage development

Introduction

Enchondromas are one of the most common benign tumors occurring in bone, occurring in about 3% of the population1,2. They are composed of cells derived from growth plate chondrocytes and can occur as solitary lesions or as multiple lesions in enchondromatosis syndromes. Enchondromas can progress to malignant chondrosarcomas, an occurrence that is more common in multiple enchondromatosis. Somatic mutations in IDH1 and IDH2, the genes encoding isocitrate dehydrogenase proteins are present in the majority of enchondromas and in at least half of chondrosarcomas3–5. The IDH genes encode for enzymes that convert isocitrate to alpha-ketoglutarate (a-KG), a component in the citric acid cycle and a metabolic fuel. IDH 1 and 2 reside in the cytoplasm and mitochondria, respectively. The mutant IDHfound in enchondromas, and chondrosarcoma produces D-2-hydroxyglutarate (D-2-HG)6. IDH1 and IDH2mutations in tumors are heterozygous, because their wild-type activities are essential for cellular respiration and metabolic function3,4,7,8. D-2-HG is sometimes called an “oncometabolite”6, and is shown to have epigenetic effects related to histone and DNA hypermethylation; stabilize Hypoxia Induced Factor one alpha (Hif-1α) protein; impair cellular differentiation; increase cell proliferation; and increase the expression of stem cell markers9–12. However, the effect of mutant IDH is cell type dependent13 and its role in chondrocytes is not completely elucidated.

Mice expressing the Idh1-R132Q mutation driven by regulatory elements of type 2 collagen (Col2a1-Cre; ldh1LSL−R132Q L/WT) show a delay in growth plate terminal differentiation but exhibit perinatal lethality. A temporally regulated mouse, Col2a1-Cre/ERT2; ldh1LSL−R132Q L/WT, in which Cre expression is induced in Col2 expressing cells by tamoxifen after weaning, developed multiple enchondroma lesions. Thus, an Idhsomatic mutation gives rise to growth-plate cells that persist in the bone as enchondromas, failing to undergo normal differentiation5.

While bulk expression profiling showed differences between chondrocytes expressing a mutant and wild type Idh14,15, such analyses cannot identify changes in subpopulations of cells. To determine how a mutant Idh might change the behavior of specific subpopulations of growth plate cells, we undertook single cell RNA sequencing to compare growth plates from Col2a1-Cre; ldh1LSL−R132Q L/WT animals with those from control littermates. Because the growth plates and enchondromas that develop in adult Col2a1-Cre/ERT2; ldh1LSL−R132Q L/WT mice contain very few cells, it was not technically feasible to use these animals for single cell RNA analysis.

Results

Single-cell RNA analysis identified eight chondrocyte subtypes in embryonic growth plate

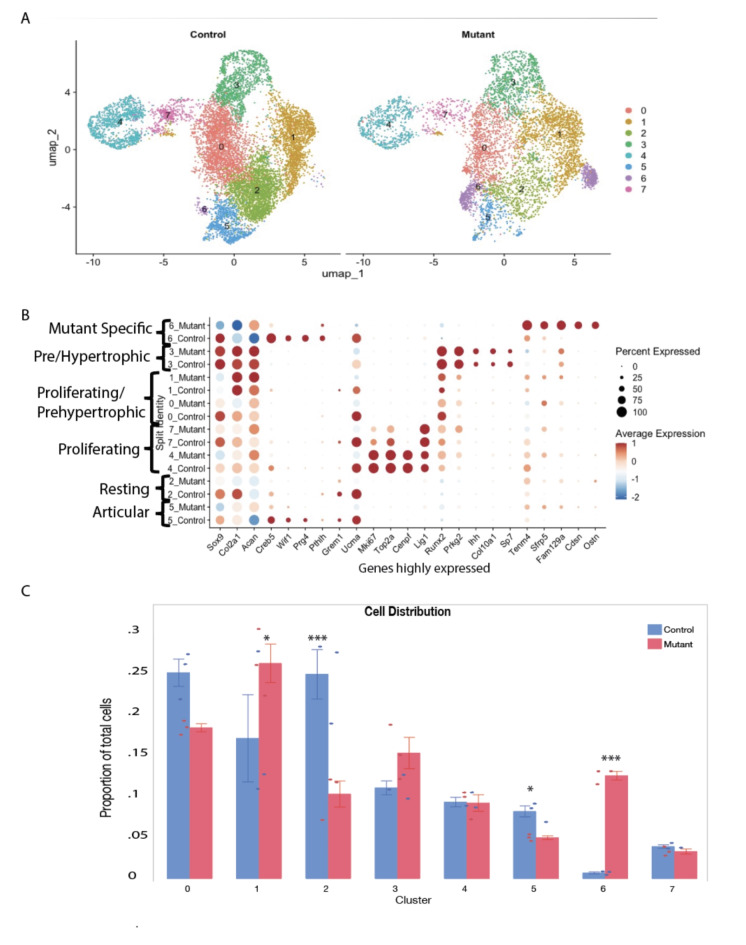

To investigate how the expression of a mutant Idh1 alters cell populations in growth plate chondrocytes in a way that could cause the development of enchondromas, we performed single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) analysis using embryonic growth plate chondrocytes from E18.5 Col2a1-Cre; ldh1LSL−R132Q L/WT (Idh1 mutant knock-in) and ldh1LSL−R132Q L/WT (Cre negative) controls. Cells from three animals were used for each genotype. 6061 cells from mice expressing the mutant Idh1 and 10,562 cells from control animals were analyzed (supplementary materials, Table S1). The Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) dimensionality reduction method was used to visualize similar cells together in two-dimensional space, and this clustering via the Louvain method was performed at a resolution of 0.28. Chondrocytes express genes that function to produce a specialized extracellular matrix including collagen type two and glycosaminoglycan16. Genes expressed by all chondrocytes, Col2a1, Acan and Sox9 showed abundant expression in all the cells from control or mutant animals in this analysis (Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. 2). Growth plate chondrocytes undergo a tightly regulated differentiation pathway including low proliferating chondrocytes, also termed resting chondrocytes and articular chondrocytes. Adjacent to the resting cells, proliferating chondrocytes, sometimes termed as column-forming flat chondrocytes are present, which differentiate into pre-hypertrophic chondrocytes which have a nominal proliferation rate. Pre-hypertrophic chondrocytes undergo a rapid volumetric increase to differentiate into hypertrophic chondrocytes (HC)17–23. Analysis revealed eight clusters within the chondrocyte population (Fig. 1A and Supplementary Fig. 1A and B). Growth plate chondrocyte subtype types were annotated based on the marker genes expressed (Supplementary Fig. 2 and their trajectory in Supplementary Fig. 3),

Fig. 1.

ScRNA-Seq analysis of growth plates expressing mutant Idh1 and littermate controls expressing wild-type Idh1. A UMAP visualization of cell clusters from scRNA sequence analysis of Control (left) and Mutant (right) shows 7 clusters; B dot plot showing the expression of selected top markers for each cluster and cell type annotation. Dot size represents the percentage of cells expressing a specific marker, while the red (higher) and blue(lower) colors indicates the average expression level for that gene, in that cluster; C bar graph showing the percentage of cells in each cluster from Control and Mutant. Statistical analysis was performed using 2-way repeated measure ANOVA; *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.0001. n = 3.

Cluster 5 showed enrichment for Wnt inhibitory factor 1 (Wif1) and Creb5, thus was annotated as articular chondrocytes24. Cluster 2 was highly enriched in Grem1 along with Upper zone of growth plate and cartilage matrix associated protein (Ucma), thus annotated as resting chondrocytes25. Cluster 4 and 7 show increased expression of cell cycle genes, such as Mki67, Top2a, Cenpf and and Lig1and are designated as proliferating chondrocytes26. Runt-related transcription factor 2 (Runx2) induces chondrocyte maturation, enhances chondrocyte proliferation through Ihhinduction and is expressed by proliferating and prehypertrophic chondrocytes18, and was highly expressed in Clusters 0 and 1. Cluster 3 was enriched in Protein Kinase CGMP-Dependent 2 (Prkg2) which is required for the proliferative to hypertrophic transition of the growth plate chondrocytes27, Indian hedgehog (Ihh)28, and Collagen type X (Col10a1)29 and Sp7, thus annotated as prehypertrophic. These genes are expressed in both prehypertrophic chondrocytes and preosteoblasts, consistent with the potential for differentiated growth plate chondrocytes to become osteoblasts30. Markers of terminal hypertrophic cells (markers such as Mmp1331) were not present in our data set (supplementary Fig. 2), consistent with hypertrophic chondrocytes being beyond the volume of conventional single cell sequencing approaches32.

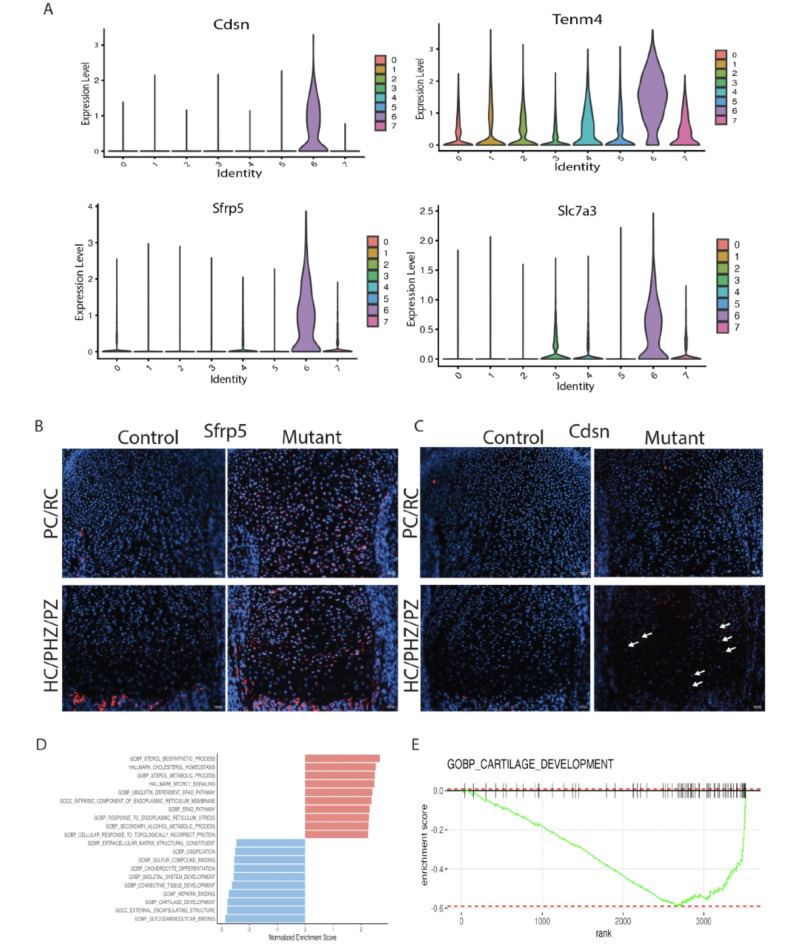

A distinct chondrocyte population is identified in Idh1 mutant cells

Cluster 6 was contributed primarily by Idh1 mutant cells and was found in all the biological replicates from mutant animals (Supplementary Fig. 1A). About 12% of Idh1 mutant cells and less than 1% of control cells contributed to this cluster (p < 0.0001, Fig. 1B). This cluster was enriched in Teneurin-4 (Tenm4)33, Corneodesmosin (Cdsn)34, Secreted Frizzled Related Protein 5 (Sfrp5)35 and solute carrier family 7 member 3 (Slc7a3) (Fig. 2A). Tenm4 is a transmembrane protein that can suppresses chondrogenic differentiation33. Sfrp5can inhibit the Wnt signaling pathway, and it is expressed in proliferating and pre-hypertrophic growth plate cells35. Using immunofluorescence, we found that Sfrp5 protein expression was restricted to the proliferating and pre-hypertrophic in control samples, however the number of cells expressing and region of expression was expanded in the mutant samples (Fig. 2B). Cdsn is an extracellular glycoprotein essential for maintaining the skin barrier in adult skin and normal hair follicle formation that is not characteristically expressed in chondrocytes36. Its expression was detected in the mutant samples (Fig. 2C), suggesting a role for this gene in the development of enchondromas. To verify its role in the growth plate in mature animals and in murine enchondromas, we undertook immunohistochemistry using adult samples from our prior study5, finding that Cdsn is expressed at a higher level in mutant growth plates than controls, and it is expressed by cells from enchondromas (Supplementary Fig. 4). The amino acid transporter protein solute carrier family 7 member 3 (Slc7a3) is a sodium-independent cationic amino acid transporter that mediates the uptake of the cationic amino acids arginine, lysine and ornithine in a sodium-independent manner, and is upregulated due to glutamine deprivation37. Chondrocytes with an Idh1 mutation utilize glutamine as a cell energy source15 and its upregulation is consistent with the notion that it drives glutamine in enchondroma precursor cells.

Fig. 2.

ScRNA-Seq analysis reveals distinct cluster contributed by the mutant Idh1 expressing chondrocytes: A violin plots showing the expression of top feature genes in the distinct cluster 6—Cdsn, Tenm4, Sfrp5, and Slc7a3. B, C Immunofluorescence for Sfrp5 and Cdsn from representative mutant and control growth plates; B Sfrp5 protein expression was detected in resting (RC), proliferating (PC) and prehypertrophic (pHC) chondrocytes in the mutant while it was restricted to few cells in the PC and pHC chondrocytes in the control; C Cdsn protein was detected in PC and pHC zones in Idh1 mutant and absent in the control growth plates; D Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) of cluster 6 showing upregulated (shown in red) and downregulated (shown in blue) pathways; E GSEA plot showing that cartilage development is downregulated in cluster 6.

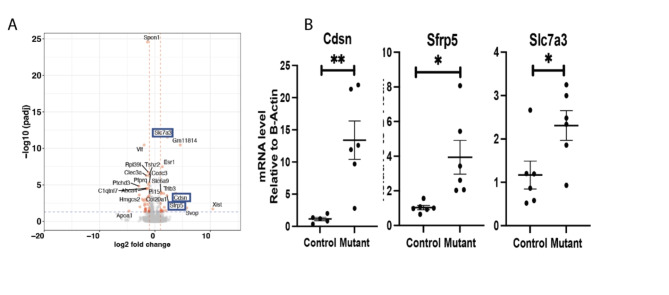

Matn1, Col9a1, Cnmd and Matn3were the most downregulated genes in Cluster 6 from the mutant cells. These genes encode for proteins important in cell-matrix interaction38. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) for cluster 6 genes, showed several downregulated pathways in this cluster (Fig. 2D and E) including ones involved in cartilage development extracellular matrix structural constituents, ossification, chondrocyte differentiation, and skeletal system development. There upregulation of cholesterol homeostasis pathways, sterol metabolic process and mTORC1signaling pathways (Supplementary Fig. 5). Some of genes identified as highly expressed in cluster 6, such as Slc7a3, Cdsn and Sfrp5 were also identified as differentially regulated in bulk RNA sequencing analysis (Fig. 3A). Since a gene that is highly expressed in cell subpopulation can be identified in bulk sequencing as they are not expressed in other cell subpopulations, this finding is constant with the notion that these genes are primarily expressed in this unique cluster. Trp53 loss cab increase chondrocyte proliferation39, and could contribute to the development of enchondromas in the mutant growth plates. While we found low levels of Trp53 expression in all our samples, there was a modest decrease in expression in the mutant growth plates consistent with a potential role for this tumor suppression in enchondroma formation (Supplementary Fig. 6). To determine if the differential expression we identified could be detected in human enchondroma samples, we analyzed published expression profilin of enchondromas and normal chondrocytes deposited in Gene Expression Omnibus database GSE308354. While the numbers of samples were small, this showed a trend towards the same differences in expression as shown in our single cell data (Supplementary Fig. 7).

Fig. 3.

Bulk RNA sequencing from micro-dissected growth plates detects upregulation of genes in cluster 6. A Volcano plot showing differential expression between mutant and control growth plates: Sfrp5, Cdsn and Slc7a3 were significantly upregulated, marked in blue box; B realtime quantitative RT-PCR confirming upregulated gene expression of Sfrp5, Cdsn and Slc7a3.

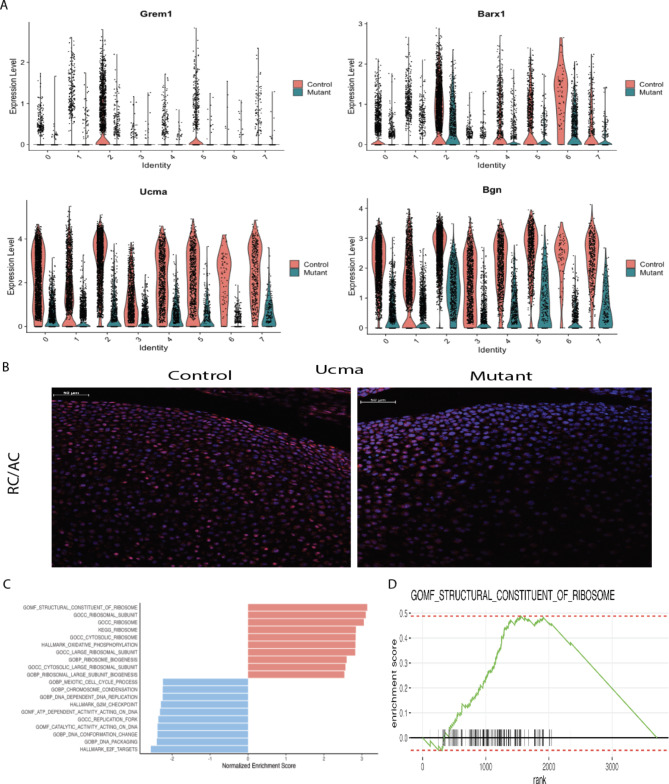

Two cell populations, cluster 2 and 5 were under-represented in Idh1 mutant animals

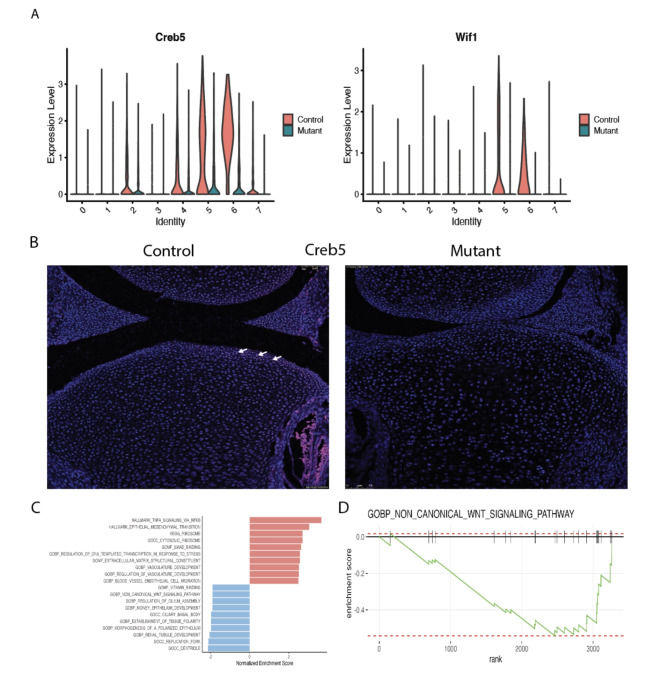

In addition to identifying a cluster of cells uniquely present in the Idh1 mutant animals, we identified two cell populations which were composed of s fewer Idh1 mutant cells. Cluster 2 is composed of about 10% from mutant, while 24% from control cells (Supplementary Table S2). This cluster expresses Grem1, Barx1, Ucma and Bgn (Fig. 4A). Ucmais normally expressed in differentiated chondrocytes20,40, , and immunofluorescence verified that mutant growth plate has decreased Ucma expression compared to the controls (Fig. 4B). The GSEA analysis of this cluster identifies pathways which upregulated in ribosome biogenesis, protein biosynthetic processes as well as peptide metabolic process (Fig. 4C and D and supplementary Fig. 8). Chondrocytes require high translational capacity to meet the demands of proliferation, matrix production, and differentiation41. Thus, this cluster may play a role in longitudinal bone growth, and growth plates lacking cells in this subpopulation may be responsible for the observed short limb phenotype. Cluster 5 also showed a significant decrease in the mutant cells (Figs. 1C and 5A). This cluster expressed genes characteristic of articular chondrocytes, and immunofluorescence of Creb5, a gene expressed in this cluster shows very few articular chondrocytes staining in the mutants compared to the control (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 4.

Cell populations (cluster 2, resting chondrocytes) that are underrepresented in the mutant growth plates. A Violin plots showing the expression of top genes in cluster 2, Grem1, Barx1, Ucma, and Bgn. B immunofluorescence for Ucma protein—it’s expression was detected in articular chondrocytes and resting chondrocytes in the control growth plate while in the mutant, Ucma expression is almost absent in these regions; C GSEA of cluster 2 showing upregulated (shown in red) and downregulated (shown in blue) pathways; D GSEA plot showing that molecular function of structural constituent of ribosome pathway is upregulated in this cluster 2.

Fig. 5.

Cell populations (cluster 5, articular chondrocytes) that are underrepresented in the mutant growth plates. A Violin plots showing the expression of top genes in cluster 5, Creb5 and Wif1; B immunofluorescence for Creb5 protein—its expression was detected in articular chondrocytes in the control growth plate while in the mutant, Creb5 expression is almost absent. Arrows show positively stained cells; C GSEA of cluster 5 showing upregulated (shown in red) and downregulated (shown in blue) pathways. D GSEA plot showing that in this cluster 5, biological process of non-canonical WNT signaling pathway is downregulated.

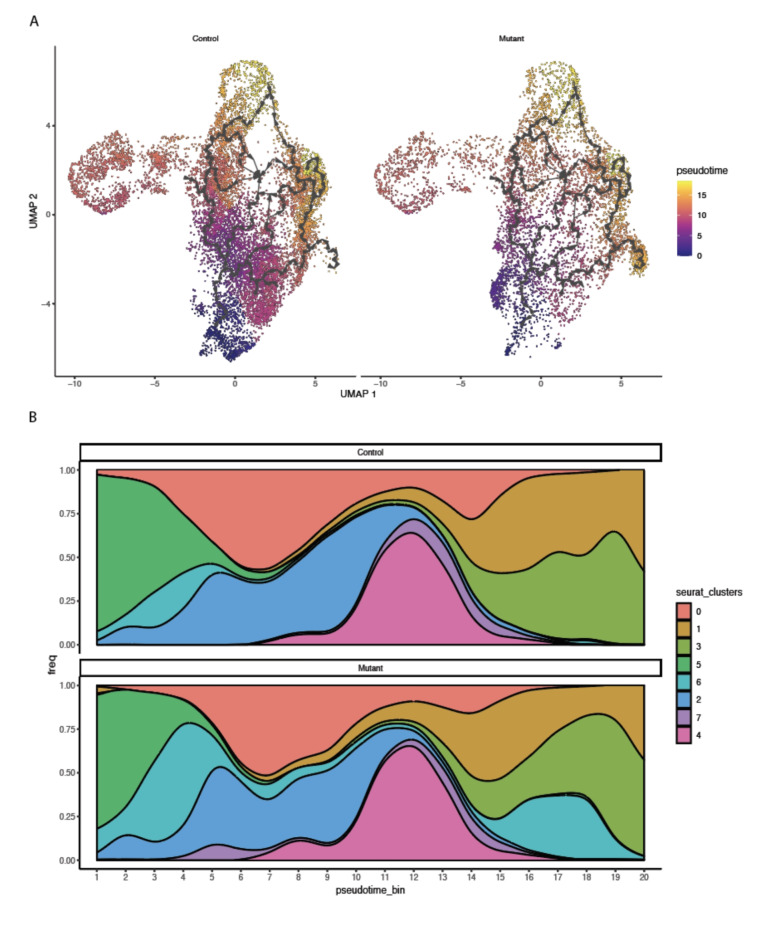

Pseudotime analysis shows differences between mutant and control growth plates

To investigate additional differences between control and Idh1 mutant chondrocytes that might be identified using single cell analysis, cells were ordered using pseudotime analysis in an unsupervised manner. The results showed that cluster 5 (articular chondrocytes) and cluster 2 (resting chondrocytes) were at early stages, while proliferating and prehypertrophic chondrocytes were from middle to late stages in the pseudotime scale, respectively (Fig. 6A). Interestingly, cluster 6 cells were split into early and mid-late scale suggesting that some of these cells remained at a less differentiated stage (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

Pseudotime analysis. A The UMAP plots show pseudotime trajectories of subtypes of chondrocytes; B population graph showing the cells in pseudotime bins arranged from left (early) to right (late), in 1–20 bins.

Discussion

The concept that enchondromas derive from growth plate cells that fail to undergo differentiation during longitudinal growth is supported by the anatomic finding that enchondromas exist adjacent to growth plates, and by data from mice in which enchondromas develop when genetic alterations identified in human tumors are driven in type two collagen expressing cells. Our data from single cell analysis is consistent with this notion and suggests that that there is a unique subpopulation of chondrocytes in the growth plates from mice expressing a mutant Idh1.

The unique cluster identified in the Idh1mutants expresses genes known to be upregulated and downregulated in enchondromas42. Immunofluorescence for the proteins corresponding to the genes expressed in this population are not anatomically located in a single location on the growth plate but distributed throughout several zones. The subpopulation of cells underrepresented in the mutant growth plate expresses genes that are known to play a role in longitudinal bone growth. It is possible that a shift from this subpopulation by mutant cells is to be responsible for the associated growth defectivity in limbs which contain multiple enchondromas. Cells in this subpopulation may play a more generalized role in longitudinal bone growth.

Single cell expression analysis is a powerful tool to identify populations of cells within a tissue and gene expression within individual cell subpopulations. This technique has been used to analyze a variety of tissues including tumors, developmental, and reparative processes. Here we used this approach to analyze growth plate cells expressing a mutation known to cause enchondromatosis. By comparing mutant and control cells, we identified a shift in cell subpopulations. This is consistent with the notion that enchondromas are formed by a shift in the fate of cells in the growth plate, leaving some cells to remain as enchondromas, and depleting some cells from populations responsible for longitudinal growth. Tumors can be made up of combinations of mutant and non-mutant cells43, and our single cell data, along with the information form localization of the genes expressed in the unique cluster found in mutant cells, is consistent with this possibility in enchondromas. Our data suggests that the study of specific cell populations may be more relevant to an understanding of specific pathologic processes. Furthermore, the data we generated can be used to further study and refine specific cell subpopulations and the role of genes expressed in these subpopulations’ role in growth pathogenies, or longitudinal long bone growth in general.

Materials and methods

Animals

All animals were used according to the approved protocol by Institutional Animal Care and Use committee of Duke University. All experiments were performed in compliance with NIH guidelines on the use and care of laboratory and experimental animals. The study is reported in accordance with ARRIVE (Animal Research: Reporting in Vivo Experiments) guidelines. Mice were euthanized by CO2 exposure. The generation of Idh1LSL/+5 and Col2a1-Cre animals was previously reported44.

Isolation of growth plate chondrocytes from embryonic growth plate

Using the Idh1R132Q lox-stop-lox (LSL) mouse, mutant Idh1 was expressed using Col2a1-Cre which will induce the expression in mouse chondrocytes. For single cell RNA seq, growth plate chondrocytes were harvested from the distal part of femur at E18.5 from Col2a1-Cre; Idh1R132Q LSL/+ and their litter mate controls expressing the wild type Idh1 followed by cell isolation using 2 mg/ml Pronase (Roche) digestion at 37 C shaker for 30 minutes with constant shaking, washed by PBS, and then digested by 3 mg/ml Collagenase IV (Worthington) for 1 hour at 37 C humidified incubator, washed with PBS, followed by 3 mg/ml Collagenase IV digestion again in petri dish at 37 C humidified incubator, and filtered using 45um cell strainer. The live cells were sorted and loaded on the 10x Genomics Chromium using the Chromium Single Cell 3’ Reagent V3 Kit and the sequencing libraries were constructed following the user guide.

scRNA-seq data pre-processing for 3′-end transcripts

Cell Ranger version V3.0.2 (10x Genomics) was used to process raw sequencing data before subsequent analyses. These RNA sequencing reads were then aligned against refdata-cellranger-mm10-3.0.0 transcriptome to quantify the expression of transcripts in each cell to create feature-barcode matrices. The analyses of processed scRNA-seq data were carried out in R version 4.1.0 using the Seurat v4 for downstream analysis45,46. This data is deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) under accession number GSE201606.

In Seurat, the data was first normalized to a log scale after basic filtering for minimum gene and cell observance frequency cut-offs (http://satijalab.org/seurat). Initial quality control filtering metrics were applied to each sample dataset such to avoid empty and dying cells (i.e. n_Count_RNA ≥ 1000; nFeature_RNA ≥ 1000; log10Genespercount > 0.80%.mt < 10 and min.cells = 3). Total of 10,591 and 6069 cells from the controls and mutants were used in the following analyses, respectively. Principal components (PCs) were calculated using the most variably expressed genes and the first thirty PCs were carried forward for clustering and visualization. Cells were embedded into a K-nearest neighbor graph using the FindNeighbors function and grouped with the Louvain algorithm via the FindClusters function at resolutions of 0.3 to calculate the granularity of the clustering. The UMAP dimensionality reduction method was used to place similar cells together in two-dimensional space. Then, the cells were subset by Col2a1 expression > 2 from the integrated file, individual cell index was extracted and re-clustered at resolution 0.28. This led to total of 10,562 and 6061 cells from the controls and mutants, respectively. The statistical analysis for percentage of cells distribution was performed using 2-way repeated measure ANOVA in JMP Pro 16 with installed Full Factorial Repeated Measures ANOVA Add-In. Cluster biomarkers were identified using the FindAllMarkers function, and differentially expressed genes between clusters were identified using the Wilcoxon test (p-value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant).

Single-cell differential gene expression analysis and GSEA for clusters of interest

Single-cell differential gene expression analysis was conducted by Seurat “FindMarkers” function using “wilcox” (v1.14.0)47 as the test method (R package). GSEA was implemented with fgsea41 R package (v1.22.0) and the gene sets were imported from msigdbr R package (V7.5.1). Generally, the differential expressing genes with statistical significances (i.e., adjusted p-value < 0.10 and min.pct > 0.25 [i.e., minimum fraction of corresponding detected cells in either of the two populations]) were used for GSEA and the log2 fold changes were used as the pre-ranked scores. Four famous pathway/gene set databases were examined here (including Hallmark42, KEGG43, and Gene Ontology44). The pathways/gene sets with < 0.05 adjusted p-value were considered as significantly enriched pathways/sets.

Pseudotime analysis

Monocle 3 (v 1.2.9) was used for trajectory analysis48. The expression matrix was exported from the Seurat object and used as Monocle 3 input. Ordering of cells based on unsupervised learning and UMAP was used for dimensionality reduction. Then, pseudotime information was extracted from monocle3 data set. The pseudotime scale classified into 20 bins and number of cells were counted in each pseudotime bin. The population plot was generated using the function “ggstream” in Fig. 6B. Gene expression and pseudotime bins were extracted from the Seurat object, average gene expression was calculated, and cells were ordered in the scale of 0–50 pseudotime bins. The dot size indicates the number of cells in each pseudotime bin, and the blue-red color range indicates the expression level from low to high.

Bulk RNAseq

For Bulk RNAseq, E18.5 growth plate cartilages were harvested from distal part of femur and proximal part of tibia from Col2a1-Cre; Idh1R132Q LSL/+ and their litter mate controls. RNA was extracted using Norgen Biotech Single Cell RNA Purification Kit. Extracted total RNA quality and concentration was assessed on a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies) and Qubit 2.0 (Thermo Fisher Scientific), respectively. Only extracts with RNA integrity number greater than 7 were processed for sequencing. RNA-seq libraries were prepared using the commercially available KAPA Stranded mRNA-Seq Kit. In brief, mRNA transcripts were first captured using magnetic oligo-dT beads, fragmented using heat and magnesium, and reverse transcribed using random priming. During the second-strand synthesis, the cDNA/RNA hybrid was converted into to double-stranded cDNA (dscDNA) and dUTP incorporated into the second cDNA strand, effectively marking the second strand. Illumina sequencing adapters were then ligated to the dscDNA fragments and amplified to produce the final RNA-seq library. The strand marked with dUTP was not amplified, allowing strand-specificity sequencing. Libraries were indexed using a 6–base pairs index, allowing for multiple libraries to be pooled and sequenced on the same sequencing lane on a HiSeq 4000 Illumina sequencing platform. Before pooling and sequencing, fragment length distribution and library quality were first assessed on a 2100 Bioanalyzer using the High Sensitivity DNA Kit (Agilent Technologies). All libraries were then pooled in equimolar ratio and sequenced. Multiplexing 8 libraries on one lane of an Illumina HiSeq 4000 flow cell yielded about 40 million 50 bp single end sequences per sample. Once generated, sequence data were demultiplexed and Fastq files generated using Bcl2Fastq conversion software provided by Illumina. This data is deposited in the Geo database accession number GSE201606.

Bulk RNAseq analysis

RNA-seq reads were trimmed by Trim Galore (v 0.6.4) and mapped with STAR49 (v 2.6.1d), with parameters --twopassMode Basic --runDirPerm All_RWX and supplying the Ensembl GRCm38 annotation to mouse genome (GRCm38). The mapped reads were counted using featureCounts50(v 1.6.4). Bioconductor package DESeq251 v 1.28.1) was employed to analyze differential expressions (DE) with litter and genotype information. Gene Ontology and KEGG enrichment tests were performed to analyze enriched biological processes by clusterProfiler52 (v 3.16.1). The volcano plots were created by EnhancedVolcano (v 1.6.0). The coverage depth was normalized by deeptools53 (v 3.1.3) using RPKM for RNA-seq. TPM values were quantified from Salmon54 (v 1.2.1) quantification and summarized via tximport7 (v 1.16.1). This data is deposited in the GEO database accession number GSE201606.

Immunofluorescence

E18.5 hindlimbs were fixed in 4%PFA overnight at 4 C. The limbs were washed in PBS for 3 times and decalcified in 14%EDTA overnight at 4 C. The limbs were washed again in PBS and incubated in 30% sucrose overnight at 4 C and were embedded in Cryomatrix until the blocks became frozen in dry ice. The blocks were sectioned at 10 μm thickness for Immunofluorescence. The slides were brought to room temperature (RT) followed washes in PBS. Antigen retrieval was performed using 10 mg/ml Proteinase K treatment for 10 min at room temperature followed by washes in PBS. The sections were blocked using 5% donkey serum and 0.3% Triton-X-100 in PBS for 1 h at RT. Then the sections were diluted in the blocking serum and incubated overnight at 4 C. The antibodies: anti-Ucma, Cat# PA520768, 1/200; For anti-CDSN antibody, Mybiosource, Cat# MBS713765, 1/50 dilution; anti-Sfrp5 antibody, Thermofisher, product #PA5-71770, 1/100 dilution; anti-Creb5 antibody, Thermofisher, Cat#PA5-65593). After washing with PBS, sections were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with Alexa Fluor-594 secondary antibody (1:700, Jackson ImmunoResearch). The sections were washed with PBS before mounting with ProLong Glass Antifade Mountant with NucBlue Stain (Thermo Fisher Scientific, P36981), visualized by fluorescence microscopy (Axio Imager 2, Carl Zeiss).

Analysis of gene expression

Total RNA was extracted from cells or tissues using RNAeasy mini kits (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Total RNA was reverse transcribed in BioRad RT Reagent Kit to make cDNA. Quantitative real-time RT-PCR (BioRad) was performed using SYBR Premix (BioRad). Analysis of gene expression was performed using the ΔΔCt method. Data were normalized to expression of the beta-actin mRNA levels. Each experiment was performed in triplicates.

qRT-PCR Primer Sequence:

Sfrp5: FP—CCCTGGACAACGACCTCTGC; RP—CACAAAGTCACTGGAGCACATCTG.

Cdsn: FP—CTGATGGCCGGTCTTATTCT; RP—GCTGTTGGAGCCAGTCTTTC.

Slc7a3: FP—GGACTGTGTTATGCTGAATTTG; RP—CCAATGACGTAGGAGAGAATG.

Study approval

All the animal experiments were approved by Duke University’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Funded by a grant from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH): R01 AR066765.

Author contributions

Vijitha Puviindran—conducting experiments, acquiring, and analyzing data, and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. Eijiro Shimada—acquiring and analyzing data.Zeyu Huang—acquiring and analyzing data.Xinyi Ma—analyzing data and contributed to the writing of the manuscript.Xiaolin Wei—acquiring and analyzing data.Ga I Ban—analyzing data.Yu Xiang - acquiring and analyzing data.Hongyuan Zhang—analyzing data and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. Makoto Nakagawa—analyzing data.Jianhong Ou—acquiring and analyzing data and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. John Martin—analyzing data and contributed to the writing of the manuscript Yarui Diao—designing research studies and analyzing data.Benjamin A. Alman—designing research studies, analyzing data, and contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Data availability

Single cell data and RNA sequencing is deposited in Geo database accession number GSE201606.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hong, E. D. et al. Prevalence of shoulder enchondromas on routine MR imaging. Clin. Imaging. 35 (5), 378–384 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walden, M. J., Murphey, M. D. & Vidal, J. A. Incidental enchondromas of the knee. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol.190 (6), 1611–1615 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amary, M. F. et al. IDH1 and IDH2 mutations are frequent events in central chondrosarcoma and central and periosteal chondromas but not in other mesenchymal tumours. J. Pathol.224 (3), 334–343 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pansuriya, T. C. et al. Somatic mosaic IDH1 and IDH2 mutations are associated with enchondroma and spindle cell hemangioma in Ollier disease and Maffucci syndrome. Nat. Genet.43 (12), 1256–1261 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hirata, M. et al. Mutant IDH is sufficient to initiate enchondromatosis in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 112 (9), 2829–2834 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dang, L. et al. Cancer-associated IDH1 mutations produce 2-hydroxyglutarate. Nature. 465 (7300), 966 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marcucci, G. et al. IDH1 and IDH2 gene mutations identify novel molecular subsets within de novo cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia: a Cancer and Leukemia Group B study. J. Clin. Oncol.28 (14), 2348–2355 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yan, H. et al. IDH1 and IDH2 mutations in gliomas. N Engl. J. Med.360 (8), 765–773 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao, S. et al. Glioma-derived mutations in IDH1 dominantly inhibit IDH1 catalytic activity and induce HIF-1alpha. Science. 324 (5924), 261–265 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Figueroa, M. E. et al. Leukemic IDH1 and IDH2 mutations result in a hypermethylation phenotype, disrupt TET2 function, and impair hematopoietic differentiation. Cancer Cell18 (6), 553–567 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Turcan, S. et al. IDH1 mutation is sufficient to establish the glioma hypermethylator phenotype. Nature. 483 (7390), 479–483 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu, W. et al. Oncometabolite 2-hydroxyglutarate is a competitive inhibitor of alpha-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases. Cancer Cell19 (1), 17–30 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lu, C. et al. Induction of sarcomas by mutant IDH2. Genes Dev.27 (18), 1986–1998 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang, H. et al. Intracellular cholesterol biosynthesis in enchondroma and chondrosarcoma. JCI Insight, 5 (11). (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Zhang, H. et al. Distinct roles of glutamine metabolism in Benign and malignant cartilage tumors with IDH mutations. J. Bone Min. Res.37 (5), 983–996 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DiFrisco, J., Love, A. C. & Wagner, G. P. Character identity mechanisms: a conceptual model for comparative-mechanistic biology. Biol. Philos.35 (4), 44 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kobayashi, T. et al. Indian hedgehog stimulates periarticular chondrocyte differentiation to regulate growth plate length independently of PTHrP. J. Clin. Invest.115 (7), 1734–1742 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lefebvre, V. & Smits, P. Transcriptional control of chondrocyte fate and differentiation. Birth Defects Res. C Embryo Today. 75 (3), 200–212 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tagariello, A. et al. Ucma—a novel secreted factor represents a highly specific marker for distal chondrocytes. Matrix Biol.27 (1), 3–11 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eitzinger, N. et al. Ucma is not necessary for normal development of the mouse skeleton. Bone. 50 (3), 670–680 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kato, K. et al. SOXC transcription factors induce cartilage growth plate formation in mouse embryos by promoting noncanonical WNT signaling. J. Bone Min. Res.30 (9), 1560–1571 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Surmann-Schmitt, C. et al. Wif-1 is expressed at cartilage-mesenchyme interfaces and impedes Wnt3a-mediated inhibition of chondrogenesis. J. Cell. Sci.122 (Pt 20), 3627–3637 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li, J. et al. Systematic reconstruction of molecular cascades regulating GP development using single-cell RNA-Seq. Cell Rep.15 (7), 1467–1480 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang, C. H. et al. Creb5 establishes the competence for Prg4 expression in articular cartilage. Commun. Biol.4 (1), 332 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ng, J. Q. et al. Loss of Grem1-lineage chondrogenic progenitor cells causes osteoarthritis. Nat. Commun.14 (1), 6909 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liddiard, K. et al. DNA ligase 1 is an essential mediator of sister chromatid telomere fusions in G2 cell cycle phase. Nucleic Acids Res.47 (5), 2402–2424 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koltes, J. E. et al. Transcriptional profiling of PRKG2-null growth plate identifies putative down-stream targets of PRKG2. BMC Res. Notes. 8, 177 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Akiyama, H. et al. Indian hedgehog in the late-phase differentiation in mouse chondrogenic EC cells, ATDC5: upregulation of type X collagen and osteoprotegerin ligand mRNAs. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun.257 (3), 814–820 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zheng, Q. et al. Type X collagen gene regulation by Runx2 contributes directly to its hypertrophic chondrocyte-specific expression in vivo. J. Cell. Biol.162 (5), 833–842 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nakashima, K. et al. The novel zinc finger-containing transcription factor osterix is required for osteoblast differentiation and bone formation. Cell108 (1), 17–29 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qin, X. et al. Runx2 is essential for the transdifferentiation of chondrocytes into osteoblasts. PLoS Genet.16 (11), e1009169 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.See, P. et al. A single-cell sequencing guide for immunologists. Front. Immunol.9, 2425 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Suzuki, N. et al. Teneurin-4, a transmembrane protein, is a novel regulator that suppresses chondrogenic differentiation. J. Orthop. Res.32 (7), 915–922 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matsumoto, M. et al. Targeted deletion of the murine corneodesmosin gene delineates its essential role in skin and hair physiology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.105 (18), 6720–6724 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Witte, F. et al. Comprehensive expression analysis of all wnt genes and their major secreted antagonists during mouse limb development and cartilage differentiation. Gene Expr. Patterns9 (4), 215–223 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jonca, N. et al. Corneodesmosomes and corneodesmosin: from the stratum corneum cohesion to the pathophysiology of genodermatoses. Eur. J. Dermatol.21 (Suppl 2), 35–42 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Karna, E. et al. Proline-dependent regulation of collagen metabolism. Cell. Mol. Life Sci.77 (10), 1911–1918 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yao, B. et al. Investigating the molecular control of deer antler extract on articular cartilage. J. Orthop. Surg. Res.16 (1), 8 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li, Y., Yang, S. T. & Yang, S. Trp53 controls chondrogenesis and endochondral ossification by negative regulation of TAZ activity and stability via beta-TrCP-mediated ubiquitination. Cell. Death Discov.8 (1), 317 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Surmann-Schmitt, C. et al. Ucma, a Novel secreted cartilage-specific protein with implications in osteogenesis*. J. Biol. Chem.283 (11), 7082–7093 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Trainor, P. A. & Merrill, A. E. Ribosome biogenesis in skeletal development and the pathogenesisof skeletal disorders. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis.1842 (6), 769–778 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shi, Z. et al. Exploring the key genes and pathways in enchondromas using a gene expression microarray. Oncotarget. 8 (27), 43967–43977 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Al-Jazrawe, M. et al. CD142 identifies neoplastic desmoid tumor cells, uncovering interactions between neoplastic and stromal cells that drive proliferation. Cancer Res. Commun.3 (4), 697–708 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Long, F. et al. Genetic manipulation of hedgehog signaling in the endochondral skeleton reveals a direct role in the regulation of chondrocyte proliferation. Development. 128 (24), 5099–5108 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Villani, A. C. et al. Single-cell RNA-seq reveals new types of human blood dendritic cells, monocytes, and progenitors. Science. 356 (6335) (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Macosko, E. Z. et al. Highly parallel genome-wide expression profiling of individual cells using nanoliter droplets. Cell161 (5), 1202–1214 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Finak, G. et al. MAST: a flexible statistical framework for assessing transcriptional changes and characterizing heterogeneity in single-cell RNA sequencing data. Genome Biol.16, 278 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cao, J. et al. The single-cell transcriptional landscape of mammalian organogenesis. Nature. 566 (7745), 496–502 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dobin, A. et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 29 (1), 15–21 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liao, Y., Smyth, G. K. & Shi, W. featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics. 30 (7), 923–930 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol.15 (12), 550 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yu, G. et al. clusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. Omics. 16 (5), 284–287 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ramírez, F. et al. deepTools2: a next generation web server for deep-sequencing data analysis. Nucleic Acids Res.44 (W1), W160–W165 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Patro, R. et al. Salmon provides fast and bias-aware quantification of transcript expression. Nat. Methods. 14 (4), 417–419 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Single cell data and RNA sequencing is deposited in Geo database accession number GSE201606.