Abstract

Several clinical trials have been conducted to evaluate the use of flavopiridol (FP) to treat a variety of cancers, and almost all cancer drugs were found to be associated with toxicity and side effects. It is not clear whether the use of FP will affect the female reproductive system. Granulosa cells, as the important cells that constitute the follicle, play a crucial role in determining the reproductive ability of females. In this study, we investigated whether different concentrations of FP have a toxic effect on the growth of immortalized human ovarian granulosa cells. The results showed that FP had an inhibitory effect on cell proliferation at a level of nanomole concentration. FP reduced cell proliferation and induced apoptosis by inducing mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress, as well as increasing BAX/BCL2 and pCDK1 levels. These results suggest that toxicity to the reproductive system should be considered when FP is used in clinical applications.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-77032-2.

Keywords: Human ovarian granulosa cells, Flavopiridol, Oxidative stress, Apoptosis, Cell cycle arrest

Subject terms: Cancer, Cell biology

Introduction

The process of oocyte growth, maturation, and ovulation involves the interaction and signal regulation among multiple cell types. The oocyte affects the function and differentiation of granulosa cells, which in turn provide oocytes with the necessary energy and substances1–3. Several substances produced by granulosa cells can be utilized as nutrients to support oocyte growth and maturation2–4, while oocytes can secrete GDF9 and BMP15 to regulate the function of surrounding somatic cells and promote the proliferation of granulosa cells by binding to surface receptors, in which gap junctions play an important role in information transmission and substance transport5,6. The interaction between granulosa cells and oocytes jointly regulates the process of follicular growth, maturation, and ovulation.

Cycle-dependent protein kinases are serine/threonine (Ser/Thr) protein kinases, among them, CDK serves as a catalytic subunit, while cyclin is a regulatory subunit. They form different Cyclin-CDK complexes and participate in the regulation of cell cycle and transcriptional activity7. The CDK1, CDK2, CDK4, and CDK6 are mainly involved in the regulation of cell cycle progression, while CDK8, CDK9, CDK12, CDK13, and CDK19 mainly regulate gene transcription8. FP is a plant-derived flavonoid, originally extracted from a native plant in India; it has now been synthesized artificially9. A large number of studies have shown that FP can be used as an inhibitor of CDK1, CDK2, CDK4, CDK6, CDK7, and CDK9; it regulates a variety of cell functions including its obvious cell cycle arrest effect10. Previous studies have shown that FP has a significant inhibitory effect on lymphoma, leukemia, thyroid cancer and mantle cell lymphoma. Also, its anti-proliferative effect in various cancers is mediated by cell cycle arrest, followed by apoptosis7. In clinical trials, FP showed some side effects, such as diarrhea and increased transaminase following administration11,12. Therefore, in this study, we explored whether FP can also cause side effects or toxicity to the female reproductive system.

In addition to the mitotic (M) phase, the cell cycle includes G1, S, and G2 phases. CDK1 plays a major role in controlling the initiation, progression, and termination of the cell cycle13. Inhibition of CDK1 activity may prevent cells from entering mitosis, as it is the main protein kinase that drives cell cycle progression, and cyclinB-CDK1 is the key component of the M-phase promoting factor, which can promote M phase initiation. Inhibition of cyclinB-CDK1 activity leads to G2/M phase arrest, growth inhibition and apoptosis14. Cell cycle arrest will lead to cell growth inhibition and apoptosis; mitochondrial dysfunction can also trigger apoptosis and autophagy, affecting intracellular ROS homeostasis and DNA damage. The DNA damage response (DDR) mainly includes repairing the non-homologous terminal junction and homologous pathway of DNA damage when the cell cycle is arrested, and it will continue until the DNA damage is repaired during cell cycle arrest; otherwise, the pathway of cell death is activated by damaged cells15. One of the important biological signals of toxic reactions is ROS. Cellular metabolic dysfunction can be caused by excessive levels of ROS. It is of great significance for cell survival to stimulate cells to produce antioxidant proteins to resist oxidative damage, inhibit ROS imbalance and maintain homeostasis.

This study was aimed at clarifying whether FP displays reproductive toxicity in the female reproductive system. Therefore, the immortalized human granulosa cell line SVOG was pretreated with different concentrations of FP in the culture medium, to observe whether it had toxic effects on SVOG cells, and further explore the mechanism of its toxicity to granulosa cells.

Results

FP inhibits SVOG cell viability and proliferation

First, we investigated whether FP (ranging from 25 nM to 500 nM)-containing culture affected the proliferation of SVOG cells. Light microscopy images of SVOG cells exposed to FP are shown in Fig. 1A. With increasing FP concentrations, the detached SVOG cells increased while adherent cells were decreased when compared with the control (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

FP inhibits SVOG cell growth and viability. (A) The typical images of SVOG cells exposed to various concentrations of FP for 24 h. Scale: 100 μm. (B) The relative viability of SVOG cells after FP treatment was revealed by CCK8 assay measuring the OD 450 nM. ns P > 0.05, *P < 0.05, ****P < 0.0001.

We next treated SVOG cells with different concentrations of FP and performed CCK8 experiments. The results showed that FP prominently inhibited SVOG cell growth and viability in a dose-dependent manner as indicated in Fig. 1B (100% (control group, n = 4) vs. 93.91 ± 2.877% (FP-25 nM, n = 4), ns P > 0.05; vs. 96.36 ± 1.269% (FP-50nM, n = 4), *P < 0.05; vs. 82.64 ± 1.156% (FP-100nM, n = 4), ****P < 0.0001; vs. 67.96 ± 0.9099% (FP-200nM n = 4), ****P < 0.0001; vs. 55.25 ± 1.350% (FP-300nM, n = 4), ****P < 0.0001; vs. 56.02 ± 1.206% (FP-400nM, n = 4), ****P < 0.0001; vs. 50.13 ± 0.9087% (FP-500nM, n = 4), ****P < 0.0001; and the IC50 value of FP on SVOG cells at 24 h was 500 nM). When the concentration was in the range of 25–100 nM, the viability of SVOG cells was slightly inhibited, and the inhibition became more obvious with increased concentrations (Fig. 1B). Treatment concentrations above 300nM caused up to 50% cell death; consequently, the concentrations at 50 nM and 200 nM were used to explore the effect of FP on SVOG cells. We also used the primary mouse ovarian granulosa cells for cell viability tests and showed that FP exposure significantly decreased the cell viability, as shown in Fig. S1.

FP exposure increases apoptosis of SVOG cells

Cell death can take a variety of forms, one of which is apoptosis. Shown here are typical images of flow cytometry detection of cell apoptosis by Annexin V/PI staining after SVOG cells at different concentrations of FP for 24 h. (Fig. 2A). It includes necrotic cells (upper left, Annexin V- and PI+), apoptotic cells (lower right, Annexin V+, and PI-), normal cells (lower left, Annexin V- and PI-), and late apoptotic or necrotic cells (upper right, Annexin V+, and PI+). Flow cytometry showed that the percentages of early apoptotic cells and late apoptosis or necrosis cells were dose-dependently increased as indicated in Fig. 2B (Early apoptosis: 1.580 (control group, n = 3) vs. 1.527 ± 0.3965 (FP-50nM, n = 3 ), ns P>0.05; vs. 2.543 ± 0.1378 (FP-200nM, n = 3), *P < 0.05; Late apoptosis: 1.343 (control group, n = 3) vs. 1.200 ± 0.2512 (FP-50nM, n = 3), ns P>0.05; vs. 2.700 ± 0.1963, n= (FP-200nM), **P < 0.01). 200 nM FP treatment group showed significantly increased apoptosis compared with the control group.

Fig. 2.

FP exposure triggers apoptosis of SVOG cells. (A) The typical images of flow cytometry detection of cell apoptosis by Annexin V/PI staining after SVOG cells were treated with different concentrations of FP for 24 h. (B) The proportion of cells in early apoptosis and late apoptosis. ns P > 0.05, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. (C) SVOG cells incubated with 0 nM, 50 nM or 200 nM FP for 24 h and stained with DAPI (blue)/PI (red) double-staining assay. Scale: 100 μm. (D) Fluorescence intensity analysis of PI staining levels of SVOG cells. ns P > 0.05, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. (E) Fluorescence intensity analysis of DAPI staining levels of SVOG cells. ns P > 0.05, **P < 0.01. (F) The relative mRNA expression levels of apoptosis-associated genes (BAX/BCL2), normalized by that of the housekeeping gene as the internal control. ns P > 0.05, ****P < 0.0001. (G) Western blot of apoptosis-associated proteins (BAX and BCL2) after treatment with different concentrations of FP for 24 h. (H) The expression level of proteins related to apoptosis in each group. ns P > 0.05, *P < 0.05.

Also, DAPI was co-stained with PI to further detect apoptosis and necrosis of SVOG cells (Fig. 2C). The relative fluorescence intensity in the 200 nM group was significantly enhanced compared with the control group as indicated in Fig. 2D (1 (control group, n = 5) vs. 3.295 ± 0.8074 (FP-50nM, n = 5), **P < 0.01; vs. 5.330 ± 1.157 (FP-200nM, n = 5), *P < 0.05), and Fig. 2E (1 (control group, n = 5) vs. 1.847 ± 0.4908 (FP-50nM, n = 5), ns P>0.05; vs. 3.816 ± 1.046 (FP-200nM, n = 5), **P < 0.01).

In addition, we detected the relative mRNA expression levels of apoptosis-associated genes (BAX/BCL2), and the housekeeping gene was used as the internal control to normalize the results. The results showed that the relative mRNA expression was significantly higher in the groups treated with 200 nM FP as indicated in Fig. 2F (1 (control group, n = 3) vs. 2.071 ± 0.5020 (FP-50nM, n = 3), ns P>0.05; vs. 4.075 ± 0.02487 (FP-200 nM, n = 3), ****P < 0.0001), and as revealed by Western blotting; the BAX/BCL2 levels in the control group were significantly lower than those in the FP-treated group as shown in Fig. 2G and H (Figs. 1 and 2H (control group, n = 5) vs. 1.507 ± 0.2436 (FP-50nM, n = 5), ns P>0.05; vs. 2.029 ± 0.2523 (FP-200 nM, n = 5), *P < 0.05). We also used primary mouse ovarian granulosa cells for verification and found that the level of BAX/BCL2 levels in the control group was significantly lower than that in the FP treatment group (Fig.S1B,C). Original blots are presented in Supplementary Fig. 3. Therefore, these results suggest that FP can induce SVOG cell apoptosis.

FP exposure increases ROS levels and damages mitochondria in SVOG cells

We next investigated whether FP can affect the level of oxidative stress in SVOG cells. In this experiment, a 12-well plate was incubated with a DCFH-DA probe for 25 min in an incubator following treatment with 0 nM, 50 nM, or 200 nM FP for 24 h. We assayed the effects of different concentrations of FP on intracellular ROS levels in SVOG cells using a DCFH-DA probe. We conducted fluorescence intensity analysis of DCFH-DA staining levels using ImageJ software (Fig. 3A). The relative fluorescence intensity in the 50 or 200 nM groups was significantly enhanced compared with the control group (Figs. 1 and 3B (control group, n = 5) vs. 1.406 ± 0.08700 (FP-50nM, n = 5), **P < 0.01; vs. 8.259 ± 1.183 (FP-200nM, n = 5), ***P < 0.001. The results suggested that the oxidative stress of SVOG cells increased significantly after FP treatment.

Fig. 3.

FP exposure increases ROS level and mitochondrial damage of SVOG cells. (A) Effects of different concentrations of FP exposure on intracellular ROS levels in SVOG cells, assayed with a DCFH-DA probe. Scale: 100 μm. (B) Fluorescence intensity analysis of DCFH-DA probe staining levels of SVOG cells. The control group was designated as 1, to evaluate the relative fluorescence intensity in other groups. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. (C) The relative mRNA expression levels of antioxidative genes (GPX1, PRDX2, CAT, and SOD2), normalized by that of the housekeeping gene as the internal control. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. (D) Representative images of MMP after treatment with different concentrations of FP for 24 h, as revealed by JC-1 staining (red: JC-1 aggregate signal, green: JC-1 monomer signal). Scale: 100 μm. (E) The ratios of red fluorescence intensities to green fluorescence intensities after exposure to different concentrations of FP for 24 h. *P < 0.05, ****P < 0.0001.

Next, we explored whether FP treatment can cause intracellular antioxidant stress response. In the FP-treated group, qRT-PCR showed remarkably lower levels of expression of genes encoding glutathione peroxidase 1 (GPX1) (1 (control group, n = 3) vs. 0.2791 ± 0.07240 (FP-50 nM, n = 3), ***P < 0.001; vs. 0.2708 ± 0.01019 (FP-200nM, n = 3), ****P < 0.0001), peroxiredoxin 2 (PRDX2) ( 1 (control group, n = 3) vs. 0.4748 ± 0.01795 (FP-50nM, n = 3), ****P < 0.0001; vs. 0.4652 ± 0.02921 (FP-200 nM n = 3), ****P < 0.0001), catalase (CAT) (1 (control group, n = 3) vs. 0.2849 ± 0.04245 (FP-50nM, n = 3), ****P < 0.0001; vs. 0.1122 ± 0.003401 (FP-200nM, n = 3), ****P < 0.0001, and superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) (1 (control group, n = 3) vs. 0.4257 ± 0.06703 (FP-50nM, n = 3), **P < 0.01; vs. 0.4041 ± 0.05585 (FP-200nM, n = 3), ***P < 0.001) (Fig. 3C).

Next, we showed that the mitochondrial membrane potential is decreased by excessive oxidative stress, which damages their function. JC-1 staining was used to detect the MMP of SVOG cells. With this staining mitochondria with high membrane potential show red fluorescence, while mitochondria with low membrane potential show green fluorescence. The ratio of JC-1 aggregate/monomer in fluorescence of live SVOG cells was recorded to measure mitochondrial membrane potential (Fig. 3D). A significant decrease in SVOG fluorescence ratio was observed in FP-exposed cells when compared to control cells (Figs. 1 and 3E (control group, n = 3) vs. 0.5173 ± 0.1518 (FP-50nM, n = 3), *P < 0.05; vs. 0.1901 ± 0.04871 (FP-200nM, n = 3), ****P < 0.0001).

These results revealed that FP-exposed cells display increased oxidative stress and impaired mitochondrial function.

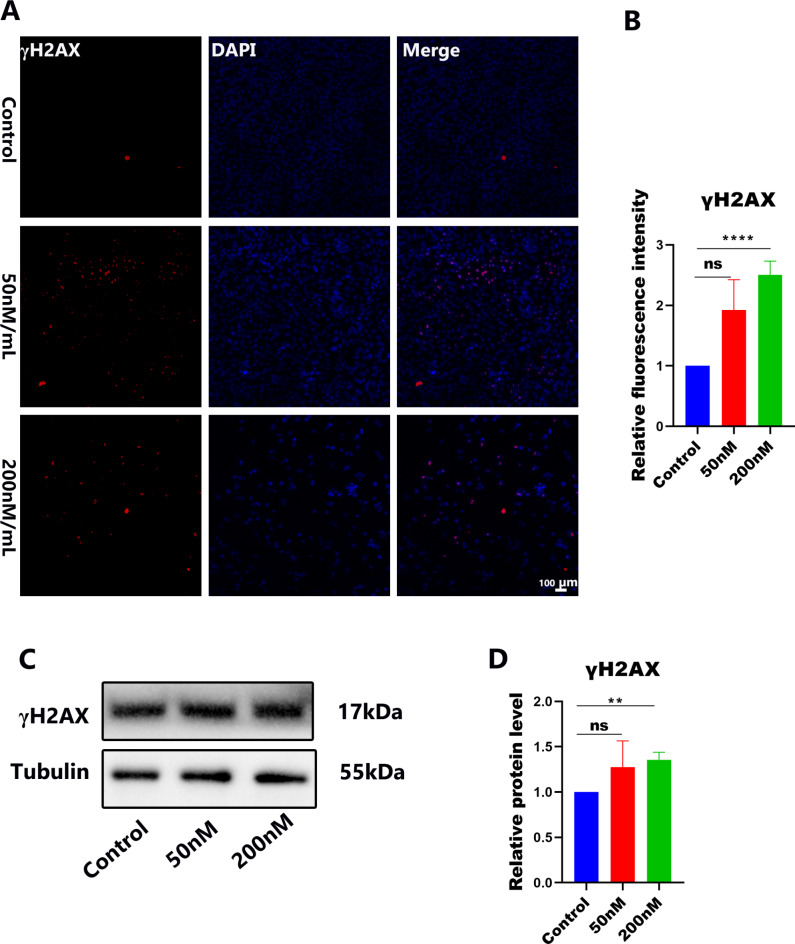

FP exposure increases the DNA damage in SVOG cells

Unrepaired DNA damage can also cause apoptosis; by labeling the relative level of expression of γH2AX, it was verified that FP could induce DNA damage in SVOG cells (Fig. 4A, Fig. S2A). In the cells exposed to FP, we observed a greater relative fluorescence of γH2AX compared to the control culture cells, and the fluorescence signal increased with the increase of FP concentration (Figs. 1 and 4B (control group, n = 6) vs. 1.527 ± 0.3965 (FP-50nM, n = 6), ns P>0.05; vs. 2.543 ± 0.1378 (FP-200nM, n = 6), ****P < 0.0001; Fig. S2B, 6.633 (control group, n = 30) vs. 13.87 ± 0.9207 (FP-50nM, n = 30), ****P < 0.0001; vs. 21.90 ± 0.9888 (FP-200nM, n = 30), ****P < 0.0001). Western blotting results showed that the expression level of γH2AX protein in the FP-treated group for 24 h was higher than that in the control group (Fig. 4C,D) (Figs. 1 and 4D (control group, n = 4) vs. 1.275 ± 0.2883 (FP-50nM, n = 4), ns P>0.05; vs. 1.355 ± 0.08336 (FP-200nM, n = 3), **P < 0.01). Original blots are presented in Supplementary Fig. 4. This result indicates that FP caused DNA damage in SVOG cells.

Fig. 4.

FP exposure increases DNA damage of SVOG cells. (A) The typical images with γH2AX (red) and DAPI (blue) staining levels of SVOG cells. Scale: 100 μm. (B) Fluorescence intensity analysis of γH2AX staining levels of SVOG cells. ns P > 0.05, ****P < 0.0001. (C) Western blot of γH2AX protein in cells exposed to different concentrations of FP for 24 h. (D) The expression level of γH2AX protein in each group. ns P > 0.05, **P < 0.01.

FP arrests the cell cycle at the G2/M phase in SVOG cells

CDKs, CDK4, CDK6, CDK7, and CDK9 can all be inhibited by FP, an inhibitor of cyclin-dependent kinases. When CDK1 binds to Cyclin B, CDK1 is activated, and phosphorylated Cyclin B binds CDK1 to initiate cell progression to the M phase.

In order to determine whether FP exposure can affect cell proliferation, we used flow cytometry to monitor the progression of SVOG cells through their cell cycle (Fig. 5A). After culturing for 24 h, the percentage of SVOG cells in the G2/M (p < 0.05) phase in the FP exposure group was significantly increased compared with the control group. We performed a detailed analysis of the S-phase, including incorporation of BrdU to unambiguously discriminate late S from G2/M phase cells (Fig. S2C). FP can lead to the arrest of proliferation of SVOG cells in the G2/M phase, and, within a certain concentration range, the higher the concentration of the drug, the stronger the blocking effect (Fig. 5B, G0/G1: 66.06% (control group, n = 3) vs. 63.52 ± 1.375% (FP-50nM, n = 3), ns P>0.05; vs. 61.91 ± 0.1320% (FP-200nM, n = 3), **P < 0.01; S: 16.15% (control group, n = 3) vs. 16.70 ± 0.7108% (FP-50nM, n = 3), ns P>0.05; vs. 13.90 ± 0.2034% (FP-200nM, n = 3), *P < 0.05; G2/M: 17.56% (control, n = 3 group) vs. 20.38 ± 0.6199% (FP-50nM, n = 3), *P < 0.05; vs. 24.17 ± 0.06658%, (FP-200nM n = 3), ****P < 0.0001; Fig. S2D, G0/G1: 62.70% (control group, n = 3) vs. 66.73 ± 2.466% (FP-50nM, n = 3), ns P>0.05; vs. 68.03 ± 7.834% (FP-200nM, n = 3), ns P>0.05; S: 27.20% (control group, n = 3) vs. 19.53 ± 1.997% (FP-50nM, n = 3), *P < 0.05; vs. 11.26 ± 4.599% (FP-200nM, n = 3), *P < 0.05; G2/M: 8.380% (control, n = 3 group) vs. 11.33 ± 0.08819% (FP-50nM, n = 3), **P < 0.01; vs. 17.44 ± 3.673%, (FP-200nM n = 3), *P < 0.05). We detected the pCDK1 protein levels after exposure to different concentrations of FP for 24 h by Western blot. Compared to the control group, FP treatment significantly increased the level of pCDK1 protein expression (Fig. 5C and D) Figs. 1 and 5D (control group, n = 3) vs. 1.651 ± 0.4446% (FP-50nM, n = 3), ns P>0.05; vs. 2.055 ± 0.1386% (FP-200nM, n = 3), **P < 0.01). Original blots are presented in Supplementary Fig. 5. After SVOG cell treatment with FP, the expression of pCDK1 increased, and SVOG was blocked in the G2/M phase, resulting in an increase of the G2/M ratio compared to the control.

Fig. 5.

FP arrests the cell cycle at the G2/M phases. (A) Representative flow cytometry diagram for cell cycle detection after treatment with FP. (B) Analysis of cell cycle ratio after FP treatment by flow cytometry. ns P>0.05, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001 (C) Western blot of pCDK1 protein in cell exposed to different concentrations of FP for 24 h. (D) The expression level of pCDK1 protein in each group. ns P > 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Discussion

Several clinical trials have been conducted on the effects of FP for the treatment of leukemia, multiple myeloma, sarcoma and other solid tumors11,16–19, but its toxicity on the reproductive system is not known. Granulosa cells constitute an important part of follicles, which determine female reproduction20. Studies have shown that the health and function of somatic follicular cells can reflect the oocytes’ health and ability, and vice versa. In this study, the human ovarian granulosa cell line (SVOG) was selected to study whether the use of FP will have a certain effect on the female reproductive system. We demonstrated that FP reduced cell proliferation, induced mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress, increased BAX/BCL2 and pCDK1, and induced cell cycle arrest at the G2/M phase in vitro (Fig. S3).

FP’s anti-tumor effect is typically achieved by blocking the cell cycle and inducing apoptosis, and it has a direct inhibitory effect on CDK through competitive inhibition of ATP phosphorylation21. In the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia with FP, it has been found that it inhibits a variety of CDKs and leads to the decrease of MCL1 protein expression, and finally induces cell apoptosis22,23. It has also been described in the previous literature that FP is an effective cell cycle pan-inhibitor and may be used as a radio sensitizer for some cancer types, including esophageal and ovarian cancer cell lines24,25. The pharmacological mechanism of cancer drug therapy is to inhibit cell proliferation and spread and the therapeutic effect of cancer was evaluated according to the inhibition of cancer cell proliferation and spread. Typically, when using anticancer drugs, some of the normal cells will also be damaged, resulting in side effects. In this study, different concentrations of FP were added to the culture medium to pretreat SVOG and observe its effects on cell proliferation, cell cycle block, and apoptosis. We first set the concentration range of FP to 25–500 nM for observing the cell morphology and detecting the viability of SVOG cells. Under the inverted microscope, we directly observed morphological changes, multi-antennae and blackening death of the cells treated with FP. It had a toxic effect on cells, and with the increase in concentration of FP, the number of adherent cells of SVOG cells decreased gradually, and the number of detached cells in the culture medium increased. We showed that FP can inhibit cell proliferation and increase cell death. In this concentration range, CCK8 was used to detect the viability of SVOG cells. The results showed that FP prominently inhibited SVOG cell growth and viability in a dose-dependent manner, and the IC50 value of FP on SVOG cells at 24 h was 50 nM. Apoptosis (or programmed cell death) is a physiological event that responds to multiple stimuli. After flow cytometry analysis, we found that the apoptosis rate of SVOG cells treated with flavanol was significantly higher than that of the control group. Also, qRT-PCR indicated that relative mRNA levels of apoptotic genes in the 200 nM group were significantly higher, and as a result the BAX/BCL2 level in the control group was significantly lower than that in the FP-treated group as revealed by Western blotting. These results indicate that FP can induce apoptosis of SVOG cells. Therefore, when females use FP as an anticancer drug, it should be considered whether it will affect the normal ovarian granulosa cells and whether it has toxic side effects on the female reproductive system.

The production of ROS can cause oxidative eustress and oxidative distress, which is a leading cause of cell apoptosis26. ROS is a beneficial signal molecule with beneficial physiological functions, and the redox state of cells can be maintained in a steady state through the tight coupling system of antioxidants and antioxidant enzymes27, but excessive ROS is harmful and damages normal cell functions28–31. The balance of reactive oxygen species is essential for cell survival. There are many self-regulatory mechanisms in cells. When there is excessive oxidative stress, in order to reduce the damage caused by oxidative stress, cells establish an effective antioxidant system to inhibit the excessive accumulation of ROS32,33. Mitochondria are the main source of cellular ROS, and they play an important role in follicular development. Cells have various antioxidant defense systems, including glutathione peroxidase (GPX1),superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), and peroxiredoxin-2 (PRDX2)34,35. Excessive ROS can cause oxidative stress damage and affect the function of mitochondria36, decrease the mitochondrial membrane potential and cause DNA damage, inducing cell apoptosis33,37. In this study, we also detected the MMP of SVOG by using JC-1 staining to evaluate the mitochondrial membrane potential and damage to the function of SVOG cells. It was found that after FP treatment, the signal of the green JC-1 monomer was higher than that of the control, while the JC-1 aggregates exhibited lower fluorescence intensity than the control, showing compromised mitochondrial function.

Our results show that the oxidative stress of SVOG cells increased significantly after FP exposure. We explored whether FP treatment can cause intracellular antioxidant stress response. According to qRT-PCR results, cells treated with FP expressed a significantly lower level of some antioxidant genes such as GPX1, PRDX2, CAT, and SOD2. After FP treatment, the level of oxidative stress and antioxidant stress in SVOG cells was disrupted, and the cells were damaged by oxidative stress.

A complex network of DNA repair and DNA damage signaling pathways known as DNA damage response (DDR) enables cells to repair DNA damage and maintain the genome38. If the cells cannot recover and activate the DDR, the affected cells will die39. In this study, we verified the effect of FP on the DNA damage response of SVOG cells by the relative expression level of marker γH2AX. Compared with the control group, SVOG cells treated with FP had a higher γH2AX relative fluorescence signal intensity, and the fluorescence signal increased gradually with the increase of FP concentration. Western blotting results showed that the expression level of γH2AX protein in the FP-treated group for 24 h was slightly higher than that in the control group, but there was no significant difference. This result indicates that FP could cause DNA damage accumulation in SVOG cells.

Cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK), a member of the serine/threonine protein kinase family, is a major cell cycle regulator that binds to cyclins to form cyclin-CDK complexes, which phosphorylates hundreds of substrates and regulates cell cycle progression40–44. CDK1, also known as mitotic kinase, can bind to Cyclin B1 to form a heterodimer CyclinB1/CDK1 45. When CDK1 binds to CyclinB1, CDK1 is activated, phosphorylates key substrates, and enters the M phase to promote mitosis progression45–47. CDK1/cyclin B complex is a necessary protein kinase for the G2/M transition. It has been reported that FP exerts its anticancer function by inhibiting a variety of cyclin-dependent kinases (CDK)48. FP exerts its anticancer activity mainly through ATP competitive inhibition of CDK (CDK1, 2, 4, 6 and 7) and indirect inhibition of cyclin activity. FP controls cell cycle progression by targeting different cell cycle proteins and CDK proteins in the G1 and G2 phases49–51. We reviewed the existing research and found that FP can also reduce the level of p21 and p27, P21 encodes cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor protein, promotes CDK1 Thr14 Tyr15 phosphorylation, inhibits CyclinB-CDK1 activity, and blocks the transition of G2/M49. Therefore, in this study, we detected the expression of pCDK1 and found that FP exposure directly inhibited the activity of CDK1 and increased the expression of pCDK1. These results of cell cycle detection by flow cytometry showed that the ratios of G0/G1 and S phase in the FP treatment group were lower than that in the control group. However, the percentage of SVOG cells in the G2/M phase in the FP exposure group was significantly increased compared with the control group. FP exposure directly inhibited the activity of CDK1 and led to the phosphorylation of CDK1 Thr14 and Tyr15 sites. In addition, the FP-treated groups expressed significantly higher levels of pCDK1 than the control groups, according to Western blot analysis. These results suggest that FP treatment can increase the expression of pCDK1 and inhibit the activity of CDK1, causing CyclinB1 / CDK1 complex activity. Inhibition, which subsequently leads to the G2 phase block of SVOG cells, and finally the inhibition of cell proliferation. In addition, we used primary mouse ovarian granulosa cells to verify the key experiments, such as cell survival test and Western blotting detection of pCDK1 expression, as a supplement figure S1. The results showed that FP exposure affected cell viability and decreased cell viability. Western blotting results also showed that pCDK1 expression increased after FP exposure. Taken together, as an anticancer drug, one should consider its reproductive side effects. At present, there is no study on whether FP as an anticancer drug has toxic or other side effects on the female reproductive system. Therefore, this study is focused on whether the concentration of FP can affect the female reproductive system, considering its safe concentration in the treatment of cancer, and considering the protection of female fertility. The information will provide some data support for considering its reproductive toxicity in the treatment of cancer.

Conclusions

In summary, we have shown that FP, at nanomole concentration, effectively inhibits ovarian granulosa cell proliferation by inducing increased pCDK1 and G2/M arrest. FP exposure also increases the level of ROS and oxidative stress, induces mitochondrial dysfunction, increases DNA damage, increased BAX/BCL2, and finally cell apoptosis.

Materials and methods

This study was approved by the ethics committee of Guangdong Second Provincial General Hospital (2022-SZ-KY-008-01). We would like to confirm that all procedures and methodologies used in this study were carried out in strict compliance with the relevant guidelines and regulations as stipulated by the journal’s editorial policy.

Cell culture

The SVOG human ovarian granulosa cell line was created by introducing the SV40 large T antigen into primary HGL cells. This cell line is commonly used by researchers to study follicle function and related molecular mechanisms52,53. SVOG cells (Immortalization of human ovarian granule cell line provided by Professor Shen Yin, College of Life Sciences, Qingdao Agricultural University.) and primary mouse ovarian granulosa cells were cultured in vitro in 12-well plates (5000 cells/well) with 1.5 mL of DMEM medium containing high glucose (SH30022, Sangon) and 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (26010074, GIBCO), supplemented with 0.1 mg/ml streptomycin and 100 U/ml penicillin (SV30010, Sangon). The cells were cultured at a constant temperature of 37 °C and pH 7.

Drug treatment and cell viability assay

According to the therapeutic concentration of FP in clinical trials, in the phase I clinical trial of FP, 76 patients were treated with infusion to limit the toxicity of secretory diarrhea (50mg/m2/day×3 day), followed by a higher dose of antidiarrheal (78mg/m2/day×3 day), the plasma concentration of FP is 300-500nM54,55. According to this, the range of FP concentration used to detect cell viability in this study is 0-500nM. FP was purchased from MedChemExpress (MCE; HY-1005). Subsequently, the drug concentration was tested by gradient dilutions (final concentrations of 25 nM-500 nM). SVOG cells were cultured in 96-well plates with medium. After 24 h, the cells were observed for adhesion. Gradient concentrations of FP (0 nM, 25 nM, 50 nM, 100 nM, 200 nM, 300 nM, 400 nM or 500 nM) were added to the fresh culture medium for 24 h, ensuring that the final concentration of DMSO did not exceed 0.1%. The cells per well were incubated with 10 µL of Cell Counting Kit-8 reagent (CCK8, Beyotime, C1086) at 37 ℃ for 1 h, and cell viability was measured by determining the OD value at 450 nM. The IC50 values were calculated using GraphPad Prism 8.

Flow cytometry

Apoptosis Assays Kit (Beyotime, C1063) and BeyoClick™ EdU-488 cell proliferation assay kit (Beyotime, C0071S) was used to detect apoptosis and cell cycle stages by flow cytometry. The apoptosis rate of SVOG cells was assessed with Annexin V-FITC/PI Apoptosis Detection Kit. The cell cycle of SVOG cells was assessed with BeyoClick™ EdU-488 cell proliferation assay kit. SVOG cells were incubated in 6-well plates at a density of 1 × 105 cells per well and treated with FP at concentrations of 0 nM, 50 nM, or 200 nM for 24 h. After trypsin digestion, 1 × 105 SVOG cells were collected for each experiment and washed twice with pre-cooled PBS.

SVOG cells were suspended in a binding buffer for 15 min and then labelled with AnnexinV-FITC and PI at room temperature in the dark. Following incubation, a binding buffer was added to the cell mixture according to the instructions (Binding buffer, AnnexinV-FITC, and PI). Green (Annexin V-FITC) and red (PI) fluorescence were detected by flow cytometry. The excitation wavelength was 488 nM. Next, after FP treatment, 5 µL PI was mixed with 400 µL of binding buffer for staining of SVOG cells, and incubated for 25 min in the dark, then mixed with 5µL DAPI and 400 µL binding buffer for 10 min under the same conditions. After being washed with PBS thrice, the images were collected with the same setting by laser confocal scanning microscopy, and the fluorescence intensity was analyzed.

The BrdU working solution (20 µM) of 2 × preheated at 37 °C was added to the cell culture plate in equal volume with the culture solution, so that the final BrdU concentration in the cell cultures became 10 µM, and cells were further cultured for 2 h. After the BrdU labelling of cells was completed, a solution of 4% paraformaldehyde was applied to the cells. Next, Triton X-100 (9002-93-1, Hyclone) was used to permeabilize cells for 15 min. After blocking with BSA for 15 min, cells were then incubated with endogenous peroxidase sealer at room temperature for 20 min. SVOG cells were suspended in a binding buffer for 15 min and then labelled with PI at room temperature in the dark. Following incubation, 25 µL PI was added to the cell mixture in proportion as described in the instructions, PI and Brdu fluorescence signals were detected by flow cytometry. The excitation wavelength of BrdU is 488 nM, and the excitation wavelength of PI is 561 nM.

Intracellular ROS assessment

A reactive oxygen species assay kit (S0033, Beyotime) was used to determine ROS levels. After FP treatment (0, 50, and 200 nM), the SVOG cells were loaded with 10 mM DCFH-DA and cultured at 37 °C for 25 min in the dark. After washing with PBS three times to reduce background intensity, images were collected using laser confocal scanning microscopy with the same settings, and fluorescence intensity was analysed.

Mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) detection

Cells were seeded in 6-well plates and treated with 0 nM and 50 nM,200 nM FP, respectively, for 24 h. The mitochondrial membrane potential assay kit (Beyotime, C1056) was used following the manufacturer’s protocol. After washing with PBS three times to reduce background intensity, images were collected using laser confocal scanning microscopy with the same settings, and fluorescence intensity was analysed.

Immunofluorescence

Trypsin was used to digest cells, and a small amount of medium was dropped into the hole where the slide is placed on the 6-well plates, so that the slide and the petri dish are bonded together by the tension of the medium, and then slides are placed to prevent the floating when cell suspension was added, resulting in a double-layer cell patch. 6-well plates (1 × 103 cells/well) were used to culture SVOG cells treated with FP(0 nM, 50 nM, and 200 nM)for 24 h. A solution of 4% paraformaldehyde was applied to the cells after three washes with PBS. Next, Triton X-100 (9002-93-1, Hyclone) permeabilization followed for 25 min. After blocking with BSA for 1.5 h, the cells were incubated with primary antibody γH2AX (1:800;10856-1-AP, Proteintech) at 4 °C overnight. The cells were washed with PBS 2 times, and the secondary antibody (A32740, Invitrogen) was added at room temperature for 1 h and with DAPI for another 15 min. After washing with PBS three times to reduce background intensity, images were collected using laser confocal scanning microscopy with the same settings, and fluorescence intensity was analyzed.

RNA isolation and quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

To isolate total RNA from granulosa cells, we used the EZ-10 Spin Column Total RNA Isolation Kit from TransZol and the Vazyme Master Mix to reverse-transcribe the RNA into cDNA. The cycle and amplification conditions were set according to the instructions. The relative gene expression to GAPDH was calculated according to the 2−△△Ct method56. The primers are listed in Supplementary Table S1. We selected a set of 4–6 appropriate housekeeping genes, for normalization and quantification purposes. The raw data of qRT-PCR is listed in Supplementary Materials 1 and 2.

Western blotting

A previously described method was used to extract total proteins from SVOG cells57. Separation of the protein fraction was achieved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), which was then subsequently blotted onto PVDF membranes and blocked with 5% BSA powder dissolved in 1×TBST at room temperature for 1.5 h. The membrane was incubated with the primary antibody overnight at 4 °C. BAX (1:2500, Proteintech, China), BCL2 (1:800, Proteintech, China), pCDK1 (1:2000, Cell Signaling Technology, USA), α-Tubulin (1:1500, Proteintech, China), β-actin (1:2000, Proteintech, China), γH2AX (1:800, Proteintech, China), then was incubated with secondary antibodies Goat anti-rabbit lgG H&L (1:5000, Proteintech, China) and Goat anti-mouse lgG H&L(1:5000, Proteintech, China) at room temperature for 1 h. Finally, our chemiluminescence reaction was carried out using a high-signal ECL Western Blotting substrate (Tanon, 180–501, Shanghai, China). Protein bands were obtained by using a luminescent imaging system.

Statistical analysis

Each experiment was repeated at least 3 times. Comparison of control and FP treatment data was conducted by using GraphPad Prism T-test software (San Diego, CA, USA), bars mean ± Std. Error of Mean (SEM). An asterisk means important compared with the control group. Significant differences were analyzed by Turkey’s range test. ns P > 0.05, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank School of Life Sciences of Qingdao Agricultural University for providing the immortalized human ovarian granulosa cell line. We thank Prof Heide Schatten from the University of Missouri-Columbia for help editing the manuscript.

Author contributions

X.-Z.L.: Software, writing-original draft, methodology, software, data curation, formal analysis, visualization; W.S., Z.-H.Z., Y.-H.L., G.-L.X.: analyzed the data; formal analysis, validation; L.-J.Y.: validation; S.Y.: supervision; Q.-Y.S. and L.-N.C.: resources, funding acquisition; project administration, writing - review & editing. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Science and Technology Program of Guangzhou, China (202201020292, 2023A03J0258).

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical statements

This study was approved by the ethics committee of Guangdong Second Provincial General Hospital (2022-SZ-KY-008-01).

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Qing-Yuan Sun, Email: sunqy@gd2h.org.cn.

Lei-Ning Chen, Email: ivfboy@189.cn.

References

- 1.Da Broi, M. G. et al. Influence of follicular fluid and cumulus cells on oocyte quality: Clinical implications. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet.35, 735–751. 10.1007/s10815-018-1143-3 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albertini, D. F. A cell for every season: The ovarian granulosa cell. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet.28, 877–878. 10.1007/s10815-011-9648-z (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Albertini, D. F., Combelles, C. M., Benecchi, E. & Carabatsos, M. J. Cellular basis for paracrine regulation of ovarian follicle development. Reproduction121, 647–653. 10.1530/rep.0.1210647 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Da Silva-Buttkus, P. et al. Effect of cell shape and packing density on granulosa cell proliferation and formation of multiple layers during early follicle development in the ovary. J. Cell Sci.121, 3890–3900. 10.1242/jcs.036400 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Turathum, B., Gao, E. M. & Chian, R. C. The function of cumulus cells in oocyte growth and maturation and in subsequent ovulation and fertilization. Cells10. 10.3390/cells10092292 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Richani, D., Dunning, K. R., Thompson, J. G. & Gilchrist, R. B. Metabolic co-dependence of the oocyte and cumulus cells: Essential role in determining oocyte developmental competence. Hum. Reprod. Update27, 27–47. 10.1093/humupd/dmaa043 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang, M. et al. CDK inhibitors in cancer therapy, an overview of recent development. Am. J. Cancer Res.11, 1913–1935 (2021). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grison, A., Atanasoski, S. & Cyclins Cyclin-dependent kinases, and cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors in the mouse nervous system. Mol. Neurobiol.57, 3206–3218. 10.1007/s12035-020-01958-7 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Soner, B. C. et al. Induced growth inhibition, cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in CD133+/CD44+ prostate cancer stem cells by flavopiridol. Int. J. Mol. Med.34, 1249–1256. 10.3892/ijmm.2014.1930 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Venkataraman, G. et al. Induction of apoptosis and down regulation of cell cycle proteins in mantle cell lymphoma by flavopiridol treatment. Leuk. Res.30, 1377–1384. 10.1016/j.leukres.2006.03.004 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hofmeister, C. C. et al. A phase I trial of flavopiridol in relapsed multiple myeloma. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol.73, 249–257. 10.1007/s00280-013-2347-y (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dispenzieri, A. et al. Flavopiridol in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma: A phase 2 trial with clinical and pharmacodynamic end-points. Haematologica91, 390–393 (2006). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jin, S. et al. GADD45-induced cell cycle G2-M arrest associates with altered subcellular distribution of cyclin B1 and is independent of p38 kinase activity. Oncogene21, 8696–8704. 10.1038/sj.onc.1206034 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vairapandi, M., Balliet, A. G., Hoffman, B. & Liebermann, D. A. GADD45b and GADD45g are cdc2/cyclinB1 kinase inhibitors with a role in S and G2/M cell cycle checkpoints induced by genotoxic stress. J. Cell. Physiol.192, 327–338. 10.1002/jcp.10140 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang, L. et al. PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway inhibitors enhance radiosensitivity in radioresistant prostate cancer cells through inducing apoptosis, reducing autophagy, suppressing NHEJ and HR repair pathways. Cell. Death Dis.5, e1437. 10.1038/cddis.2014.415 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pinto, N. et al. Flavopiridol causes cell cycle inhibition and demonstrates anti-cancer activity in anaplastic thyroid cancer models. PLoS One15, e0239315. 10.1371/journal.pone.0239315 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arguello, F. et al. Flavopiridol induces apoptosis of normal lymphoid cells, causes immunosuppression, and has potent antitumor activity in vivo against human leukemia and lymphoma xenografts. Blood91, 2482–2490 (1998). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wiernik, P. H. Alvocidib (flavopiridol) for the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs25, 729–734. 10.1517/13543784.2016.1169273 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bose, P., Vachhani, P. & Cortes, J. E. Treatment of relapsed/refractory acute myeloid leukemia. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol.18. 10.1007/s11864-017-0456-2 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Srikumar, T. & Padmanabhan, J. Potential use of flavopiridol in treatment of chronic diseases. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol.929, 209–228. 10.1007/978-3-319-41342-6_9 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parker, B. W. et al. Early induction of apoptosis in hematopoietic cell lines after exposure to flavopiridol. Blood91, 458–465 (1998). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boffo, S., Damato, A., Alfano, L. & Giordano, A. CDK9 inhibitors in acute myeloid leukemia. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res.37. 10.1186/s13046-018-0704-8 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Bose, P. & Grant, S. Mcl-1 as a therapeutic target in acute myelogenous leukemia (AML). Leuk. Res. Rep.2, 12–14. 10.1016/j.lrr.2012.11.006 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kari, C., Chan, T. O., Rocha de Quadros, M. & Rodeck, U. Targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor in cancer: Apoptosis takes center stage. Cancer Res.63, 1–5 (2003). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sato, S., Kajiyama, Y., Sugano, M., Iwanuma, Y. & Tsurumaru, M. Flavopiridol as a radio-sensitizer for esophageal cancer cell lines. Dis. Esophagus17, 338–344. 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2004.00437.x (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aklima, J. et al. Effects of matrix pH on spontaneous transient depolarization and reactive oxygen species production in mitochondria. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol.9, 692776. 10.3389/fcell.2021.692776 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bhattacharyya, A., Chattopadhyay, R., Mitra, S. & Crowe, S. E. Oxidative stress: An essential factor in the pathogenesis of gastrointestinal mucosal diseases. Physiol. Rev.94, 329–354. 10.1152/physrev.00040.2012 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang, F. et al. Melatonin alleviates beta-zearalenol and HT-2 toxin-induced apoptosis and oxidative stress in bovine ovarian granulosa cells. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol.68, 52–60. 10.1016/j.etap.2019.03.005 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hardy, M. L. M., Day, M. L. & Morris, M. B. Redox regulation and oxidative stress in mammalian oocytes and embryos developed in vivo and in vitro. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health18. 10.3390/ijerph182111374 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Saller, S. et al. Norepinephrine, active norepinephrine transporter, and norepinephrine-metabolism are involved in the generation of reactive oxygen species in human ovarian granulosa cells. Endocrinology153, 1472–1483. 10.1210/en.2011-1769 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nickel, A., Kohlhaas, M. & Maack, C. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species production and elimination. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol.73, 26–33. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2014.03.011 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kroemer, G., Dallaporta, B. & Resche-Rigon, M. The mitochondrial death/life regulator in apoptosis and necrosis. Annu. Rev. Physiol.60, 619–642. 10.1146/annurev.physiol.60.1.619 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Limon-Pacheco, J. & Gonsebatt, M. E. The role of antioxidants and antioxidant-related enzymes in protective responses to environmentally induced oxidative stress. Mutat. Res.674, 137–147. 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2008.09.015 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bock, F. J. & Tait, S. W. G. Mitochondria as multifaceted regulators of cell death. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol.21, 85–100. 10.1038/s41580-019-0173-8 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lubos, E., Loscalzo, J. & Handy, D. E. Glutathione peroxidase-1 in health and disease: From molecular mechanisms to therapeutic opportunities. Antioxid. Redox Signal.15, 1957–1997. 10.1089/ars.2010.3586 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee, J. & Song, C. H. Effect of reactive oxygen species on the endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria during intracellular pathogen infection of mammalian cells. Antioxidants (Basel)10. 10.3390/antiox10060872 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Vaccaro, A. et al. Sleep loss can cause death through accumulation of reactive oxygen species in the gut. Cell181, 1307–1328. 10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.049 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Ciccia, A. & Elledge, S. J. The DNA damage response: Making it safe to play with knives. Mol. Cell.40, 179–204. 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.019 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gonfloni, S. DNA damage stress response in germ cells: Role of c-Abl and clinical implications. Oncogene29, 6193–6202. 10.1038/onc.2010.410 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sherr, C. J. Cancer cell cycles. Science274, 1672–1677. 10.1126/science.274.5293.1672 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Malumbres, M. Cyclin-dependent kinases. Genome Biol.15, 122. 10.1186/gb4184 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Malumbres, M. & Barbacid, M. To cycle or not to cycle: A critical decision in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer1, 222–231. 10.1038/35106065 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zheng, Z. L. Cyclin-dependent kinases and CTD phosphatases in cell cycle transcriptional control: Conservation across eukaryotic kingdoms and uniqueness to plants. Cells11. 10.3390/cells11020279 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.S, M. M. Cyclin-dependent kinases as potential targets for colorectal cancer: Past, present and future. Future Med. Chem.14, 1087–1105. 10.4155/fmc-2022-0064 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Malumbres, M. & Barbacid, M. Cell cycle kinases in cancer. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev.17, 60–65. 10.1016/j.gde.2006.12.008 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Salaun, P., Rannou, Y. & Prigent, C. Cdk1, Plks, auroras, and neks: The mitotic bodyguards. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol.617, 41–56. 10.1007/978-0-387-69080-3_4 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schafer, K. A. The cell cycle: A review. Vet. Pathol.35, 461–478. 10.1177/030098589803500601 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen, R., Keating, M. J., Gandhi, V. & Plunkett, W. Transcription inhibition by flavopiridol: Mechanism of chronic lymphocytic leukemia cell death. Blood106, 2513–2519. 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1678 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Blagosklonny, M. V., Darzynkiewicz, Z. & Figg, W. D. Flavopiridol inversely affects p21(WAF1/CIP1) and p53 and protects p21-sensitive cells from paclitaxel. Cancer Biol. Ther.1, 420–425. 10.4161/cbt.1.4.21 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jiang, J. et al. Flavopiridol-induced apoptosis during S phase requires E2F-1 and inhibition of cyclin A-dependent kinase activity. Cancer Res.63, 7410–7422 (2003). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu, K. et al. The role of CDC25C in cell cycle regulation and clinical cancer therapy: A systematic review. Cancer Cell. Int.20, 213. 10.1186/s12935-020-01304-w (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chang, H. M., Cheng, J. C., Klausen, C. & Leung, P. C. Recombinant BMP4 and BMP7 increase activin A production by up-regulating inhibin betaA subunit and furin expression in human granulosa-lutein cells. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab.100, E375–386. 10.1210/jc.2014-3026 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chang, H. M. et al. Activin A-induced increase in LOX activity in human granulosa-lutein cells is mediated by CTGF. Reproduction152, 293–301. 10.1530/REP-16-0254 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Senderowicz, A. M. et al. Phase I trial of continuous infusion flavopiridol, a novel cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, in patients with refractory neoplasms. J. Clin. Oncol.16, 2986–2999. 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.9.2986 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Motwani, M., Delohery, T. M. & Schwartz, G. K. Sequential dependent enhancement of caspase activation and apoptosis by flavopiridol on paclitaxel-treated human gastric and breast cancer cells. Clin. Cancer Res.5, 1876–1883 (1999). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.He, G. F. et al. The role of L-type calcium channels in mouse oocyte maturation, activation and early embryonic development. Theriogenology102, 67–74. 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2017.07.012 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liu, R. et al. Human amniotic mesenchymal stem cells improve the follicular microenvironment to recover ovarian function in premature ovarian failure mice. Stem Cell. Res. Ther.10, 299. 10.1186/s13287-019-1315-9 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.