Abstract

Introduction

Contact with the dust of cement consisting of toxic components brings about inflammatory damage (often irreversible) to the body of a human being. The circulatory system exhibits sensitivity to inflammatory changes in the body, and one of the earliest changes may be observed in the blood parameters like mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH) and mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC). MCHC and MCH are possibly easily accessible and affordable parameters that can detect harmful changes in the body before any irreversible damage occurs.

Objectives

This research aimed to seek the changes in MCHC and MCH upon occupational contact with the toxic dust of cement.

Methods

The execution of this research was done in the Department of Physiology, Dhaka Medical College, Bangladesh, and a cement plant in Munshiganj, Bangladesh. This research was carried out between September 2017 and August 2018. Individuals (20 to 50 years old, 92 male adults) participated and were grouped into the group with occupational cement dust impact (46 subjects) and the group without occupational dust of cement impact (46 subjects). Data was collected in a pre-designed questionnaire. An independent sample t-test was conducted to analyze statistical and demographic data like body mass index and blood pressure. A multivariate regression model was applied to note the impact of cement dust on the group working in this dusty environment. Again, a multivariate regression model was employed to observe whether the duration of exposure to this dust affected MCHC and MCH. The significance level was demarcated at p < 0.05 Stata-15 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, US) for statistical analysis, and GraphPad Prism v8.3.2 (Insight Venture Management, LLC, New York, NY, US) was employed to present the data graphically when required.

Results

There was a reduction in MCHC by 0.58 g/dL and MCH levels by 0.68 pg in the cement dust-exposed subjects when compared to controls, but not significant (95% CI: -0.93, 2.10; p = 0.448 and 95% CI: -0.37, 1.73; p = 0.203, respectively). However, MCHC was reduced significantly by 0.51 g/dL (p = 0.011) with the duration of exposure to the dust.

Conclusion

The study showed that MCHC was significantly reduced with the duration of exposure to cement dust in cement plant workers. Such alterations may hamper heme synthesis, hemolysis, and inflammatory changes in the body.

Keywords: accessible, affordable, contact, cytokines, dust, early change, hemoglobin, inflammation, prevention, toxic metals

Introduction

Potential hazards threaten the health of individuals in the place of their work [1]. These hazards include physical hazards (ionizing radiation and noise), ergonomic and psychological hazards (high workload and stress), and chemical hazards (vapors, gases, and dust). When exposed to such agents, the body becomes prone to several occupation-related diseases and complications like cancers, musculoskeletal disorders, and respiratory diseases [1,2]. Industries dealing with silica, lead, and copper are responsible for the emission of toxic substances during the processing or extraction of these elements [3]. Such industries include battery, smelting, mining, ceramics, foundry, glass, and cement [4,5]. Cement is an inseparable component of building infrastructure [6]. The requirement for cement continues to rise as the economy and urbanization increase, particularly in low- to middle-income countries. The ever-growing patterns of urbanization, the need for infrastructure development, and the rise in world population are set to raise the global demand for cement by the year 2050 by about 12% to 23% of that in 2020 [7]. Southeast Asia and Africa are more likely to witness this global rise in demand for cement [8,9].

The composition of cement dust includes aluminum oxide (3%-5%), hexavalent chromium, silicon oxide (17%-25%), calcium oxide (60%-67%), potassium, iron oxide, sulfur, sodium, lead, copper, and magnesium oxide [10]. Dust of cement may enter the body of humans via inhalation, skin, and swallowing [11,12]. There have been reports of aluminum oxide exposure causing peroxidation of lipids in various tissues, leading to renal failure, anemia, and neurotoxicity [13,14]. Chromium in the form of Cr(IV), another toxic component, is reported to be a potent oxidizing agent that causes free radical generation and a rise in inflammation. This leads to deteriorating effects on the liver and respiratory and renal systems [15,16]. Accumulative oxidative damage to components of cells and alterations in functions of cells have been attributed to continuous reactive oxygen species (ROS) efflux [17,18].

Excessive exposure to lead is related to raised blood pressure, anemia, infertility, and damaging effects on the nervous and renal systems [5,19]. Although the carcinogenic impact of lead is unclear, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) considers lead a possible human carcinogen [5,20]. Another effect of lead is shortening red blood cells' (RBCs’) lifespan, which leads to reticulocytosis and anemia [21,22]. Chronic exposure to harmful components such as lead hinders the body from producing hemoglobin by disrupting the pathway's heme synthesis enzymes, which raises the risk of developing anemia [23]. A deficiency of iron that occurs due to lead absorption may also cause anemia [24].

Occupational exposure to silica, a significant constituent of this dust, is responsible for the development of an irreversible disease of the lung known as silicosis. Due to the engulfment of silica (entering via inhalation in the respiratory tract), the subject develops nodular lesions, lung fibrosis, and inflammation. Silicosis may lead to respiratory tract infection, pneumothorax, and respiratory failure [25]. In China alone, over 230,000 workers are exposed directly to respirable crystalline silica, and silicosis is one of the most prevalent diseases in the country [26]. Silicosis cases are also increasing in glass, nanomaterial, and jewelry-making industries [27,28]. Globally, respirable crystalline silica has become a threat to the development of silicosis in millions of workers. However, silicosis diagnosis depends on abnormalities of pulmonary functions and irreversible alterations observed radiographically. Early detection by use of biomarkers is a necessity for the health of these individuals. Even though various biomarkers have been noted for silicosis in occupationally exposed subjects and animal experiments, these lack diagnostic specificity and sensitivity, require high technological support, and are unsuitable for conducting in a large population. Routine blood parameters are probably a non-invasive marker for the routine assessment of the health of these workers [29-36].

Dust inhalation is also related to another occupational disease called pneumoconiosis. This occupational disease is responsible for high morbidity. Like silicosis, pneumoconiosis is evaluated clinically through the observation of radiological alterations. Early diagnosis is of much benefit to preventing extensive damage to workers' lungs from dust exposure [37]. Pneumoconiosis is one of the irreversible damages that may occur due to the inhalation of cement dust and is an outcome of inflammatory changes in the respiratory system. Studies have been conducted to find easily accessible biomarkers to determine inflammatory changes early in the respiratory system, possibly leading to pneumoconiosis [38,39]. The hemoglobin concentration in each liter of blood is represented by mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC) [38-40]. Over the years, studies have emerged concerning the clinical application of MCHC. Several research works have noted an association between MCHC and diseases like hepatorenal syndrome, acute myocardial infarction, and depression [41-43]. Relationships have also been reported between MCHC and lung disease [44,45]. The poor prognosis of lung carcinoma has been associated with lowered MCHC [45]. A decrease in MCHC has been linked to a rise in mortality in individuals suffering from acute pulmonary embolism [44]. Hemoglobin-related parameters have been reported to vary in recent research in pneumoconiosis patients [46].

The human hematopoietic system is a good indicator in toxicological research since it exhibits extreme sensitivity to alterations in the surrounding environment in which increasing metabolic demands cause rapid production and breakdown of cells [47]. Previous studies have linked a decrease in MCHC to lung diseases [44,45]. A reduction in MCHC has been noted in the advanced stages of pneumoconiosis [38]. Studies have observed alterations in hematological parameters on cement dust exposure [47-52]. However, the modifications in MCHC and mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH) of workers having contact with cement dust remain unclear. This research aims to note the MCH and MCHC alterations in those exposed to dust during cement production. Since toxic cement components promote oxidative stress and inflammation and reduce hemoglobin synthesis, they may encourage anemia [52-56]. Also, changes in these parameters may act as an early detection tool that is easy to conduct and affordable for assessing harmful changes in these workers.

Objective of the study

The research objective is to note the effect occupational exposure to cement dust has on the hematological parameters of MCHC and MCH in a Bangladeshi cement factory.

Problem statement of this study

Pneumoconiosis is one of the irreversible damages that may occur due to the inhalation of cement dust and is an outcome of inflammatory changes in the respiratory system. Studies have been carried out to find easily accessible biomarkers to determine inflammatory changes early in the respiratory system, which possibly lead to pneumoconiosis [15,24,27-29]. Being in contact with components like silica, hexavalent chromium, and lead may bring about oxidative stress [29-31]. The hematopoietic system may be impacted early in inflammatory damage [57-59]. Components of cement like lead may hamper the synthesis of hemoglobin and absorption of iron, contributing to the reduction in hemoglobin synthesis and leading to the development of anemia [60,61]. Changes in MCHC and MCH would suggest morphological changes in RBC hinting toward anemic changes in the circulation [62,63]. These biomarkers may, thus, be used on a broad scale to determine the toxic effect of cement dust on impoverished workers who often can neither afford nor have access to high-end scientific laboratory-based marker tests [38].

Materials and methods

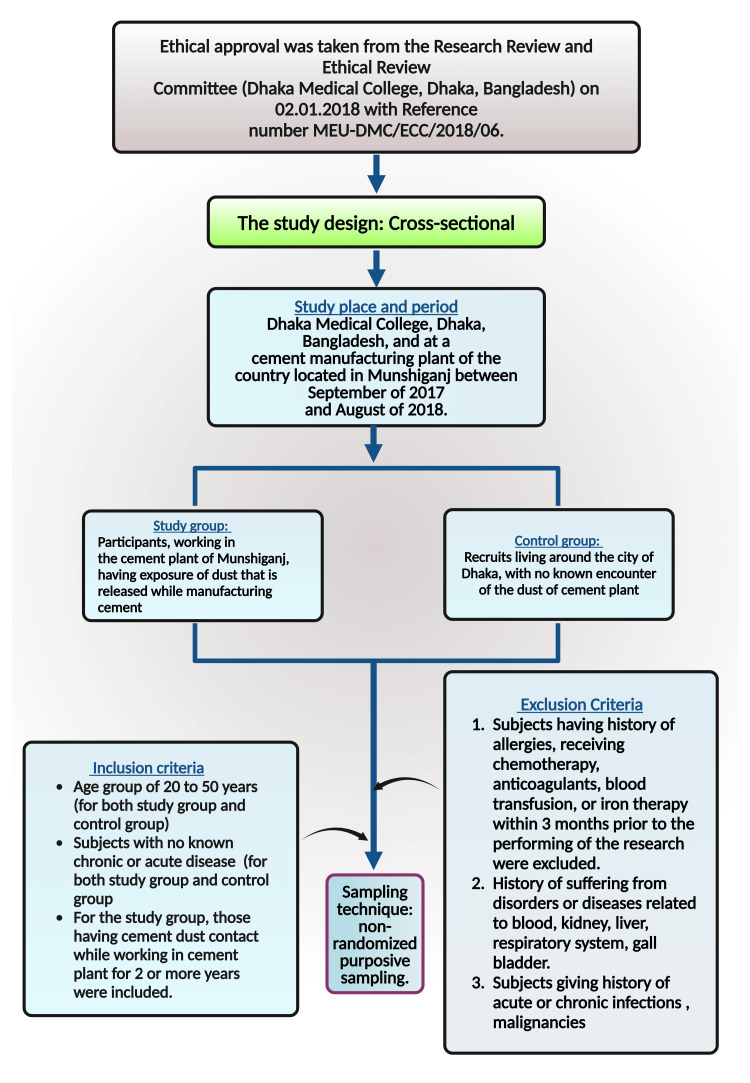

Study design

This research was a cross-sectional study.

Study place and period

The research was conducted at Dhaka Medical College, Bangladesh, and at a cement manufacturing plant in Munshiganj between September 2017 and August 2018.

Study population

The population of this research work was divided into a study group (participants working in the cement plant of Munshiganj, having exposure to dust that is released while manufacturing cement) and a control group (recruits living around the city of Dhaka, with no known encounter of the dust of cement plant). In line with a study performed earlier [52], recruits from sections like crushing, bagging, loading, and milling parts of the cement plant were chosen since these parts of the plant have the most dust release. As for the control group, those chosen had no history of traveling to areas with cement dust or other toxic dust exposure within six months before this study. Their occupation and residence were taken to ensure they were further free from such dust contact.

Selection criteria

The recruit's selection depended on the following inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria include individuals in the age group of 20 to 50 years (inclusion criteria for both the study and control groups) and subjects with no known chronic or acute disease (criteria of inclusion into the study for both the study and control groups). When choosing the study group, those who had contact with cement dust while working in a cement plant for two or more years were included. This was in line with research done previously to assess the effect of cement toxic dust on the cellular component of human blood since chronic inflammation may produce its effects slowly, taking years to cause changes in the body [58].

Exclusion Criteria

The exclusion criteria (applied for both the study and control groups) include subjects having a history of allergies and receiving chemotherapy, anticoagulants, blood transfusion, or iron therapy within three months before the performance of the research. The research excluded those with a history of suffering from disorders or diseases related to the blood, kidneys, liver, respiratory system, or gall bladder. Subjects with a history of acute or chronic infections and malignancies were also excluded.

Sampling technique

The sampling technique applied for this research was non-randomized purposive sampling.

Sample collection

Three milliliters of blood from each participant was taken and mixed with anticoagulant ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) [64]. Blood examination and MCHC and MCH tests were performed in the Department of Laboratory Medicine (Dhaka Medical College) with an automated hematology analyzer (Horiba Pentra DX (Horiba ABX SAS, Montpellier, France)). Validation of this analyzer was assessed by studies done by Hur et al. and Kim et al. [65,66]. Hur et al. noted that its specificity and sensitivity were 93.7% and 89.8%, respectively [65]. Kim et al. observed that the Pentra DX hematology analyzer showed better-flagging performance and better correlation with manual analysis when compared to the Sysmex XE-2100 (Sysmex, Kobe, Japan) hematology analyzer [66].

Data collection

After ensuring that the inclusion criteria were met, the study population answered a structured questionnaire adapted from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration's standard questionnaire [67,68] and modified Kuppuswamy socio-economic scale [69]. The questionnaire was completed through a face-to-face interview. The first segment of the questionnaire for both the study and control group included queries regarding age, locality, and sex. Also included were queries about alcohol intake, drugs consumed, medical conditions of the participants, and medical conditions like bronchial asthma, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus existing within their family. To ensure that the control group was free from exposure to cement dust, their history of travel, residence and work location, and occupation were taken. Table 1 exhibits the drugs regarding which information was taken and Table 2 presents the medical condition history of the subjects to ensure that the participants were not taking any medication therapy or suffering from any chronic disease that may bring changes to the hematological system.

Table 1. The history of drug consumed to determine inclusion into the study; exhibiting the drug history that influenced the study subject selection.

| Drugs that participants were inquired about |

| Steroids |

| Drugs that suppress allergy |

| Drugs taken to control diabetes mellitus |

| Drugs taken to control hypertension |

| Chemotherapy |

| Therapy with iron |

| Drugs that reduce blood coagulation |

| Drugs used to dilate bronchi |

| Supplementation with nutrients like vitamins |

Table 2. The medical history taken to determine inclusion into the study subjects; exhibiting the medical history that influenced the study subject selection.

| Medical conditions that participants were inquired about |

| If subjects are suffering from any allergies |

| If they are having bronchial asthma |

| If the subjects are diagnosed with diabetes mellitus |

| If they are suffering from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) |

| If they have any malignancies |

| If they have been diagnosed with hypertension |

| If the subjects suffer from any acute or chronic infections (acute/chronic) |

| If the subjects have any kidney diseases |

| If they have any liver hepatic diseases |

| If the subjects suffer from a deficiency of iron |

| If the subjects have taken any blood transfusion within three months before becoming a part of the study |

| If the participants have undergone any surgeries before the study: surgery done on them recently |

| If the participants suffer from thalassemia |

Workers of the cement plant (study group) answered the questionnaire's next segment regarding the duration of their exposure to cement dust and the section of the cement plant they worked in. Questions were also made regarding their knowledge of personal protective equipment (PPE), the significance of using PPE, and the health hazards that can develop when exposed to this dust. The last segment of the questionnaire was dedicated to collecting anthropometric measurements like weight, height, and body mass index (BMI), as well as systemic and general physical examination findings like recording blood pressure and pulse values. The study group worked in plant sections with maximum dust emission, such as sections for milling, crushing, bagging, and loading, like previous research [52].

Ethical approval

This research work's ethical approval was obtained from the Research Review and Ethical Review Committee (Dhaka Medical College, Dhaka, Bangladesh) on 02.01.2018 with reference number MEUDMC/ECC/2018/06. Details regarding the research and procedure to be performed were explained to the study participants, and following this, written consent was obtained from each of them.

Research work's impact

This research work may aid in finding a blood parameter for detecting inflammation in the body due to being exposed to dust or cement early, which is inexpensive, accessible, and easy to test. Measures may be taken early to prevent further damage to various body organs due to inflammatory changes. An affordable test may be easily performed for workers living in poverty on a large scale. The policymakers and owners of companies would be motivated to include, as part of the routine health investigations, such low-cost parameters to determine any damages to workers' health.

Statistical analysis plan

Demographic characteristics were determined by employing descriptive analysis. Cross-tabulation was performed for categorical variables like BMI, and an independent sample t-test was done for continuous variables. Multivariate regression analysis was done to see the exposure to dust effect in a study group in comparison to the participants of the control group. Adjustment by age and BMI (category) was done for the regression model. A multiple regression model (adjusted for age and BMI) was also used to assess the impact of exposure duration over the years in the study group. p-value < 0.05 was considered to be significant in this analysis. Stata-15 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, US) was used for the statistical analysis, and GraphPad Prism v8.3.2 (Insight Venture Management, LLC, New York, NY, US) was used for the graphical presentation. Figure 1 illustrates the materials and method of this research work.

Figure 1. Illustration of the materials and methods employed in this study.

The premium version of BioRender (https://biorender.com/) was used to draw this figure, which was accessed on September 17, 2024, with license number ZS27BDWWI5 [70].

Image credit: Susmita Sinha.

Results

The information on the demography of the participants is shown in Table 3. The total number of participants in the study group was 46, and the same number of participants was enrolled in the control group. The mean age was comparable in the study group and control group, which was 33.2 (±8.37) and 33.5 (±7.96) years, respectively. BMI category distribution revealed that the study group participants with normal BMI were 76.1% while 23.9% had a BMI above average. The BMI of the control group showed that 63.0% of the participants had a BMI within the normal range, while 37.0% had a BMI above the normal range. Slight variations were noted in the blood pressure readings between the two groups. Here, the study group participants had a mean systolic blood pressure of 117.7 ± 15.2 mmHg and diastolic blood pressure of 71.7 ± 9.61 mmHg. In comparison, for the control group, the systolic blood pressure was 113.0 ± 12.2 mmHg, and the diastolic blood pressure of the control group was 70.9 ± 9.21 mmHg. Those enrolled in the study group (cement plant workers) had been exposed to cement dust for an average of 7.17 years.

Table 3. Demographic information of the participants enrolled. The presentation of the data was done as the mean ± SD or number with percentage in the parenthesis. The p-value was estimated using a chi square for 2 x 2 contingency observation, and an independent sample test was performed for continuous observation.

SBP: systolic blood pressure; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; BMI: body mass index.

| Variables | Study group (n) | Control group (n) | p-value |

| BMI (kg/m2) | - | - | - |

| Normal | 35 (76.1%) | 29 (63.0%) | 0.174 |

| Above normal | 11 (23.9%) | 17 (37.0%) | |

| Age | 33.2 (±8.37) | 33.5 (±7.96) | 0.839 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 71.7 (±9.61) | 70.9 (±9.21) | 0.659 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 117.7 (±15.2) | 113.0 (±12.2) | 0.108 |

| Exposure duration (years) | 7.17 (±2.82) | - | - |

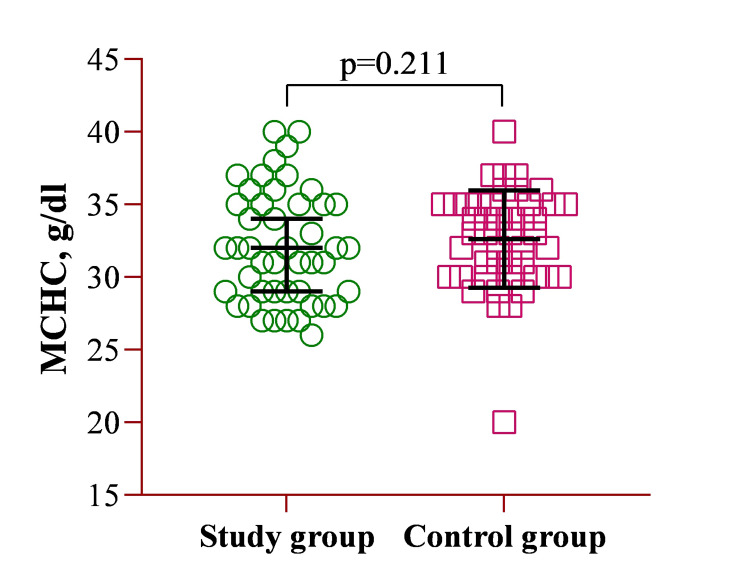

The mean MCHC concentration for the study group was 32.1 ± 3.85 g/dL, while for the control group, it was 32.6 ± 3.35 g/dL. A multivariate regression analysis revealed no significant difference between the two groups (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Illustration of the CBC parameter of MCHC.

MCHC: mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration; CBC: complete blood count.

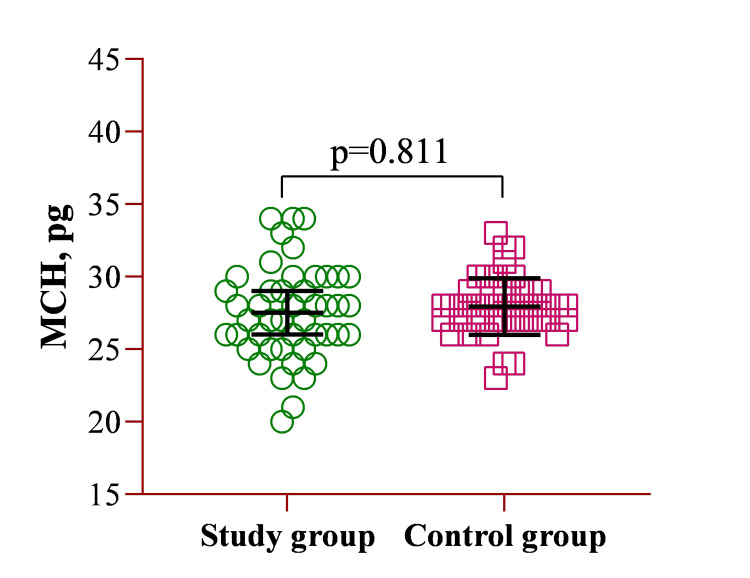

Similarly, comparing the mean MCH values between the study group (27.5 ± 3.19 pg) and the control group (27.9 ± 1.95 pg) showed no statistically significant difference. Despite slight variations in the mean values, the results suggest that MCH levels were comparable between both groups, as confirmed by the statistical analysis (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Illustration of the CBC parameter of MCH.

MCH: mean corpuscular hemoglobin; CBC: complete blood count.

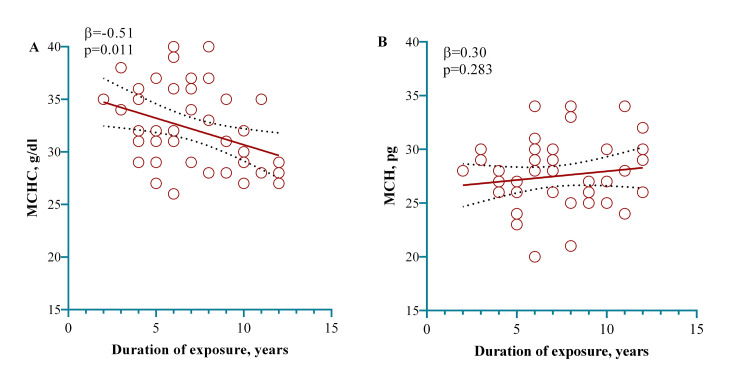

A multivariate regression model was employed to see the association with the dust of cement contact duration within the study group participants. The model showed that contact with cement dust occupationally, for one year in a plant manufacturing cement, exhibited a significant decrease in MCHC by 0.51 g/dL (p = 0.011), as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. A model showing that one year of exposure working in a cement factory significantly decreased the MCHC. The relationship (linear) between contact with the dust of cement and MCHC (A) and MCH (B) was examined here. The indication of relationship linearity is shown employing the dots in red, in which individual observations are represented by the dots in red. Calculating the p-value was done using a multivariate regression model adjusting for age and BMI (categorical) in the regression model.

MCHC: mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration; MCH: mean corpuscular hemoglobin; BMI: body mass index.

Discussion

This research study examined the impact of occupational contact with cement dust on blood parameters MCHC and MCH. Dust exposure indicates possible bodily inflammatory alterations due to contact with the dust. The significant decrease in MCHC with duration was independent of socio-demographic characteristics [71].

Cement dust contact harms human health, and the damages are often irreversible. A study by Shanshal and Al-Qazaz noted abnormal spirometry readings and a significant lowering of the function of the lung (p < 0.001) in the case of occupational contact with the dust of cement in comparison to control subjects [72]. Similar outcomes of reduced lung function, particularly abnormal peak expiratory flow (PEF), were observed by Omidianidost et al. in cement plant workers [73]. Grain warehouse workers in Costa Rica were reported to suffer from raised concentrations of respirable dust higher than the standard cut-off mark [74]. Impairment of renal function (p < 0.05) was noted by Bama et al. in Indian workers in the construction industry having been in contact with rock dust [75]. Dust emitted from the welding industry contains high volumes of heavy metals like manganese, nickel, hexavalent chromium, and aluminum [76,77]. Personnel working in rice mills are also at risk of exposure to a speck of rice dust, which may contain microbes, endotoxins, elements, and spores [78]. Therefore, respiratory tract diseases and poor lung function are common among rice mill workers primarily present in Bangladesh and India compared to those not in contact with such dust [79,80].

Dust like that in the streets also poses a threat to the health of human beings because of bioaccumulation, toxicity, and persistence. City street dust consists of zinc, chromium, copper, cadmium, arsenic, nickel, manganese, lead, and mercury above the safety levels marked by world soil background values. The health risk levels of heavy metal of street dust determined by the United States of America Environmental Protection Agency's health risk evaluation model were 5.71 × 10-3 in adults and 2.57 × 10-2 in children [81,82]. Barium, lead, and copper levels were noted by Liu et al. to be high in road dust [83]. The air surrounding mercury mines and compact fluorescent lamps were heavily polluted with mercury [84,85]. Mercury has been suggested to be a possible carcinogen in research [86]. Long-term and transient contact with chromium-containing dust has been linked to respiratory tract carcinoma and respiratory function deterioration [87].

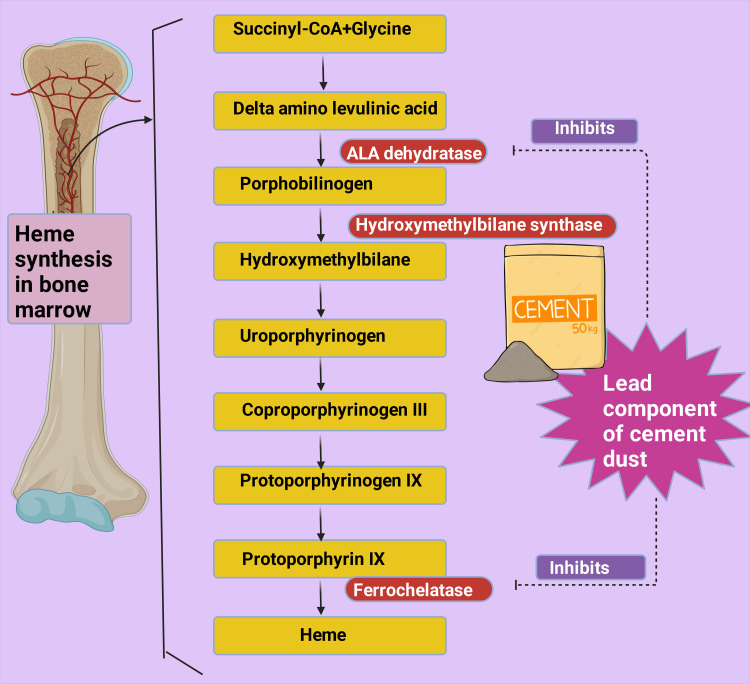

Several mechanisms may be at play that led to the study's findings. One possible pathophysiology may be due to anemia resulting from chronic inflammation. Toxic dust components may trigger inflammatory cytokines like interleukins and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), which have been noted to rise in cement dust exposure [88]. A study reported that patients with lung conditions like pneumoconiosis, which is aggravated by occupational dust inhalation, have higher levels of cytokines like TNF-α and interleukin-8 when compared to control subjects [89]; another study found raised levels of TNF-α and interleukin-1 in individuals with pneumoconiosis [90]. Anemia in inflammation may be attributed to developing resistance to erythropoietin [91,92]. In chronic inflammation, cytokines like TNF-α and interleukin-1 hampered erythropoiesis [93]. Erythropoietin resistance may result in a decrease in MCHC [38]. Lead is a component of cement dust, which has a deteriorating effect on heme synthesis by blocking the enzymes of the heme synthesis path and increasing the chance of anemia development [94]. Enzymes like ferrochelatase and delta-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase (ALA dehydratase) are inhibited by lead, which in turn blocks heme formation (Figure 5) [95-97]. Erythropoietin formation is also disrupted by this heavy metal, which prevents the maturation of RBCs [98,99]. Pyrimidine 5'-nucleotidase deficiency occurs in the presence of lead, resulting in hemolysis [100,101]. A reduced hemoglobin level was reported by Ukaejiofo et al. (p < 0.0001) in workers who handle lead occupationally in comparison to controls [102].

Figure 5. Depiction of the heme production steps in which enzymes like ferrochelatase and delta-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase (ALA dehydratase) are inhibited by lead, which blocks heme formation.

The premium version of BioRender (https://biorender.com/) was used to draw this figure, which was accessed on September 14, 2024, with agreement license number ND27B0I06W [70].

Image credit: Rahnuma Ahmad.

A study done by Kargar-Shouroki et al. on workers of a battery-producing factory in Iran noted a significant reduction in MCH and MCHC in those exposed to lead at work [103]. Absorption of lead leads to iron deficiency [24]. Studies have noted that chronic exposure to harmful components such as lead hinders the body from producing hemoglobin by disrupting the enzymes of the pathway for heme synthesis, which raises the risk of developing anemia [92]. Deficiency of iron that occurs due to lead absorption may also cause anemia [24]. Iron deficiency is often found in individuals with chronic inflammation [104]. A deficiency of iron can reduce MCHC significantly. The research observed an association between deficiency of iron and MCHC [105].

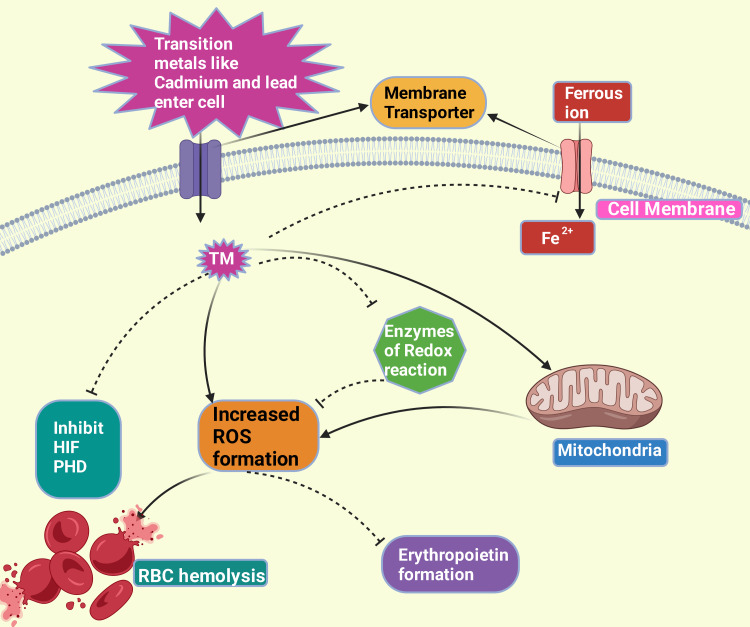

Cadmium and lead exposure may raise lead bioavailability, affecting the enzymes of heme formation steps [56,93]. Both cadmium and lead aggravate inflammation as they compete with intracellular iron, increasing the quantity of free iron that is not bound. This may promote hydrogen peroxide, superoxide, or metal systems and form ROS intermediates [106-108].

An animal study on rodents showed that cadmium exposure resulted in hemolysis [109]. Transient metals like cadmium inhibit hypoxia-inducible factor-1 and erythropoietin induction by generating intermediates of ROS, resulting in oxidative hemolysis (Figure 6) [106,110-112]. Heavy metals in cement dust may release highly reactive species, causing DNA damage, protein depletion, and lipid peroxidation. These metals can displace metals that are endogenous from carrier protein ligands. Hydroxyl ions may be produced by the Fenton reaction, giving rise to nitrite [113]. Copper(II), zinc(II), and manganese(II) cause redox reactions and aggravate cytotoxicity [114].

Figure 6. This figure explains how the entry of transition metal promotes reactive oxygen species (ROS) production either by inhibiting the scavengers of ROS or employing their redox reactivity or via disruption of the electron transport chain of the mitochondria; inhibits entry of iron into a cell; inhibits HIF and PHD. The ROS, in turn, inhibits erythropoietin formation and causes red blood cell hemolysis.

This figure was drawn using the premium version of BioRender (https://biorender.com/), accessed on September 14, 2024, with agreement license number NX27B0RZ5D [70].

PHD: prolyl hydroxylase domain enzymes; HIF: hypoxia-inducible factor; Fe2+: ferrous ion; TM: transition metal; RBC: red blood cell.

Image credit: Rahnuma Ahmad.

Several studies agree with our research. The hematocrit and hemoglobin levels have been reported to decrease significantly upon contact with dust or cement by Mojiminiyi et al. [48]. Another study on MCHC levels in pneumoconiosis patients noted a significant decrease in MCHC with the advancing stage of pneumoconiosis. They suggested that with the progress of inflammation and damage, there was a decrease in MCHC. Our study also found a reduction in MCH levels (although not significant) upon cement dust contact when compared to controls, and an insignificant negative association was also noted between MCH and duration of contact with the dust. Jacob et al. found that MCH was reduced significantly in occupational contact with this cement dust [115]. They attributed the change to a hemolytic reaction aggravated by chromium present in cement dust along with nickel, copper, and lead. They also mentioned that cement dust bioaccumulation has been reported to cause osteonecrosis and cortex thinning in the bones of animals, reducing epiphysis cartilage gradually [116,117]. This may also occur in humans and reduce absorbed dietary iron storage [115]. However, Mandal and Suva observed a rise in MCH and MCHC [118]. Such variation may be due to differences in the occupational group, extent and duration of contact with the dust of cement, and nutritional status of the workers. Table 4 gives the key findings of this study.

Table 4. The key findings of this narrative review.

MCH: mean corpuscular hemoglobin; MCHC: mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration.

| Key findings of this paper |

| Dust of cement may have damaging and often irreversible negative impacts on human health |

| Several transition metals are components of this dust including lead, hexavalent chromium, and cadmium |

| Such metals promote inflammation, inhibit heme synthesis, compete with iron absorption, and cause the formation of reactive oxygen species |

| This study observed a reduction in MCH and MCHC in subjects with cement dust contact compared to the control subjects. Moreover, a significant decrease in MCHC was noted with increasing duration of cement dust contact in those occupationally exposed to this dust |

| Such alterations in MCHC may suggest the impact of inflammatory changes on the hematological system and may be used to detect early changes due to inflammation in the human body |

| Checking parameters like MCH and MCHC is easy to perform, affordable, and accessible and thus may be included as part of the routine physical examination of the occupational dust of cement-exposed workers |

| Early detection of inflammation is necessary to prevent irreversible damage to the health of workers, and in addition, awareness needs to be developed among these workers concerning the harmful effects of being in contact with the dust of cement, and they must be encouraged to use personal protective gear while working in this dusty environment |

Limitations of the study

This research has certain limitations. The cause-effect relationship could not be obtained since the study was cross-sectional. Due to financial, time, and technical constraints, we could not research the association of each heavy metal to MCH and MCHC levels in the participants. Due to the mentioned constraints, we could not find the pathophysiology, which was dose- and time-dependent. Our research did not conduct tests to obtain the study subjects' erythropoietin, iron, and ferritin levels. Therefore, the direct link connecting to the reduction in MCHC could not be assessed. Due to time and financial limitations, the research was executed on those working in a single plant manufacturing cement.

Recommendation for future research

The study involved the workers of one factory producing cement in the country. A wide-scale, long-term, and follow-up study needs to be performed to recognize the connection between cement dust contact and MCHC and MCH. The association between each of the constituents of cement dust, MCHC, and MCH should also be studied. Policymakers and cement company owners should consider parameters like MCHC alterations, particularly those with over one year of cement dust exposure. They should encourage workers to take this accessible and affordable test for early inflammatory change detection in the body when working in a dusty environment for a prolonged time. Factory owners and those who make policies should also educate the workers regarding the importance of using PPE like masks, helmets, and gloves to lessen dust exposure [119]. Monitoring the dust emitted by the cement plants and the emission level should be limited as much as possible [120].

Conclusions

Disruption of homeostasis within the body may occur due to occupational contact with toxic dust emitted during cement production through inflammatory changes and oxidative stress. Exposure to metals like lead and chromium (components of cement dust) may inhibit enzymes of heme synthesis, compete with iron absorption, and promote inflammation and production of ROS. Inflammatory mediators like TNF-α can hamper erythropoiesis. The ROS also may cause damage to DNA, depletion of protein, and peroxidation of lipids. These metals can displace metals that are endogenous from carrier protein ligands. Hydroxyl ions may be produced by the Fenton reaction, giving rise to nitrite. This study observed a significant decrease in MCHC with the duration of exposure to the dust of cement, which may indicate a change in the hematological system related to hemoglobin. The inflammatory mediators may bring about organ damage. Several parameters for detecting inflammation in the body require high-tech laboratories and are expensive to perform. Determination of MCHC is an easily performable, affordable, and accessible test that can be included in routine health checkups of workers who encounter this dust. Any changes should be observed, and necessary steps should be taken to safeguard their health so that further inflammatory damage does not occur and these workers can remain in the workforce for a long time in good health.

Disclosures

Human subjects: Consent was obtained or waived by all participants in this study. Research Review and Ethical Review Committee (Dhaka Medical College, Dhaka, Bangladesh) issued approval MEUDMC/ECC/2018/06.

Animal subjects: All authors have confirmed that this study did not involve animal subjects or tissue.

Conflicts of interest: In compliance with the ICMJE uniform disclosure form, all authors declare the following:

Payment/services info: All authors have declared that no financial support was received from any organization for the submitted work.

Financial relationships: All authors have declared that they have no financial relationships at present or within the previous three years with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work.

Other relationships: All authors have declared that there are no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Author Contributions

Concept and design: Mainul Haque, Rahnuma Ahmad, Md. Ahsanul Haq, Susmita Sinha, Miral Mehta , Santosh Kumar, Qazi Shamima Akhter

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Mainul Haque, Rahnuma Ahmad, Md. Ahsanul Haq, Susmita Sinha, Miral Mehta , Santosh Kumar, Qazi Shamima Akhter

Drafting of the manuscript: Mainul Haque, Rahnuma Ahmad, Md. Ahsanul Haq, Susmita Sinha, Miral Mehta , Santosh Kumar, Qazi Shamima Akhter

Critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Mainul Haque, Rahnuma Ahmad, Md. Ahsanul Haq, Susmita Sinha, Miral Mehta , Santosh Kumar, Qazi Shamima Akhter

Supervision: Mainul Haque, Rahnuma Ahmad, Md. Ahsanul Haq, Susmita Sinha, Miral Mehta , Santosh Kumar, Qazi Shamima Akhter

References

- 1.Interaction of occupational and personal risk factors in workforce health and safety. Schulte PA, Pandalai S, Wulsin V, Chun H. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:434–448. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Occupational health and safety hazards faced by healthcare professionals in Taiwan: a systematic review of risk factors and control strategies. Che Huei L, Ya-Wen L, Chiu Ming Y, Li Chen H, Jong Yi W, Ming Hung L. SAGE Open Med. 2020;8:2050312120918999. doi: 10.1177/2050312120918999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Toxicity of heavy metals and recent advances in their removal: a review. Abd Elnabi MK, Elkaliny NE, Elyazied MM, et al. Toxics. 2023;11:580. doi: 10.3390/toxics11070580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Current status of trace metal pollution in soils affected by industrial activities. Kabir E, Ray S, Kim KH, et al. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3356731/pdf/TSWJ2012-916705.pdf. ScientificWorldJournal. 2012;2012:916705. doi: 10.1100/2012/916705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Evaluation of blood lead levels and their effects on hematological parameters and renal function in Iranian lead mine workers. Rahimpoor R, Rostami M, Assari MJ, Mirzaei A, Zare MR. Health Scope. 202094;95917 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Achieving net zero greenhouse gas emissions in the cement industry via value chain mitigation strategies. Miller SA, Habert G, Myers RJ, Harvey JT. One-Earth. 2021;4:1398–1411. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Projecting future carbon emissions from cement production in developing countries. Cheng D, Reiner DM, Yang F, et al. Nat Commun. 2023;14:8213. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-43660-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sustainable cement production—present and future. Schneider M, Romer M, Tschudin M, Bolio H. Cem Concr Res. 2011;41:642–650. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Climate technology & development: energy efficiency and GHG reduction in the cement industry: case study of sub-Saharan Africa. [ Oct; 2024 ];Ionita R, Wurtenberger L, Mikunda T, de Coninck H. https://climatestrategies.org/publication/policy-brief-climate-technology-development-energy-effiiciency-and-ghg-reduction-in-the-cement-industry-sub-saharan-africa/ Climate Strategies. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cement dust exposure and perturbations in some elements and lung and liver functions of cement factory workers. Richard EE, Augusta Chinyere NA, Jeremaiah OS, Opara UC, Henrieta EM, Ifunanya ED. J Toxicol. 2016;2016:6104719. doi: 10.1155/2016/6104719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Occupational cement dust exposure and inflammatory nemesis: Bangladesh relevance. Ahmad R, Akhter QS, Haque M. J Inflamm Res. 2021;14:2425–2444. doi: 10.2147/JIR.S312960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Effect of exposure to cement dust among the workers: an evaluation of health related complications. Rahmani AH, Almatroudi A, Babiker AY, Khan AA, Alsahly MA. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6026423/pdf/OAMJMS-6-1159.pdf. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2018;6:1159–1162. doi: 10.3889/oamjms.2018.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Human health risk assessment for aluminium, aluminium oxide, and aluminium hydroxide. Krewski D, Yokel RA, Nieboer E, et al. J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev. 2007;10 Suppl 1:1–269. doi: 10.1080/10937400701597766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.A systematic review on oxidant/antioxidant imbalance in aluminum toxicity. Mohammadirad A, Abdollahi M. Int J Pharmacol. 2011;7:12–21. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mechanism of chromium-induced toxicity in lungs, liver, and kidney and their ameliorative agents. Chakraborty R, Renu K, Eladl MA, et al. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022;151:113119. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2022.113119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hexavalent-chromium-induced oxidative stress and the protective role of antioxidants against cellular toxicity. Singh V, Singh N, Verma M, et al. Antioxidants (Basel) 2022;11:2375. doi: 10.3390/antiox11122375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.RONS and oxidative stress: an overview of basic concepts. Aranda-Rivera AK, Cruz-Gregorio A, Arancibia-Hernández YL, Hernández-Cruz EY, Pedraza-Chaverri J. Oxygen. 2022;2:437–478. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reactive oxygen species in inflammation and tissue injury. Mittal M, Siddiqui MR, Tran K, Reddy SP, Malik AB. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;20:1126–1167. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.5149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lead toxicity: a review. Wani AL, Ara A, Usmani JA. Interdiscip Toxicol. 2015;8:55–64. doi: 10.1515/intox-2015-0009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.International Agency for Research on Cancer. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. 1987. Overall evaluation of carcinogenicity: an updating of IARC monographs. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blood zinc protoporphyrin, serum total protein, and total cholesterol levels in automobile workshop workers in relation to lead toxicity: our experience. Pachathundikandi SK, Varghese ET. Indian J Clin Biochem. 2006;21:114–117. doi: 10.1007/BF02912924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lead toxicity and pollution in Poland. Charkiewicz AE, Backstrand JR. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:55–64. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17124385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Toxicity of lead: a review with recent updates. Flora G, Gupta D, Tiwari A. Interdiscip Toxicol. 2012;5:47–58. doi: 10.2478/v10102-012-0009-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anemia risk in relation to lead exposure in lead-related manufacturing. Hsieh NH, Chung SH, Chen SC, et al. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:389. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4315-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Silicosis. Leung CC, Yu IT, Chen W. Lancet. 2012;379:2008–2018. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60235-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Early detection methods for silicosis in Australia and internationally: a review of the literature. Austin EK, James C, Tessier J. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:8123. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18158123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Characterization of nano-to-micron sized respirable coal dust: particle surface alteration and the health impact. Zhang R, Liu S, Zheng S. J Hazard Mater. 2021;413:125447. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.125447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Evaluation of cytotoxic, genotoxic and inflammatory responses of micro- and nano-particles of granite on human lung fibroblast cell IMR-90. Ahmad I, Khan MI, Patil G, Chauhan LK. Toxicol Lett. 2012;208:300–307. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2011.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Serum levels of inflammatory mediators as prognostic biomarker in silica exposed workers. Blanco-Pérez JJ, Blanco-Dorado S, Rodríguez-García J, et al. Sci Rep. 2021;11:13348. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-92587-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Effects of occupational silica exposure on oxidative stress and immune system parameters in ceramic workers in Turkey. Anlar HG, Bacanli M, İritaş S, et al. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2017;80:688–696. doi: 10.1080/15287394.2017.1286923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blood levels of IL-Iβ, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, and MCP-1 in pneumoconiosis patients exposed to inorganic dusts. Lee JS, Shin JH, Lee JO, Lee WJ, Hwang JH, Kim JH, Choi BS. Toxicol Res. 2009;25:217–224. doi: 10.5487/TR.2009.25.4.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.A rapid point of care CC16 kit for screening of occupational silica dust exposed workers for early detection of silicosis/silico-tuberculosis. Nandi SS, Lambe UP, Sarkar K, Sawant S, Deshpande J. Sci Rep. 2021;11:23485. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-02392-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Serum concentrations of Krebs von den Lungen-6, surfactant protein D, and matrix metalloproteinase-2 as diagnostic biomarkers in patients with asbestosis and silicosis: a case-control study. Xue C, Wu N, Li X, Qiu M, Du X, Ye Q. BMC Pulm Med. 2017;17:144. doi: 10.1186/s12890-017-0489-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Neopterin as a new biomarker for the evaluation of occupational exposure to silica. Altindag ZZ, Baydar T, Isimer A, Sahin G. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2003;76:318–322. doi: 10.1007/s00420-003-0434-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Influence of silica particles on mucociliary structure and MUC5B expression in airways of C57BL/6 mice. Yu Q, Fu G, Lin H, et al. Exp Lung Res. 2020;46:217–225. doi: 10.1080/01902148.2020.1762804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.MUC5B promoter polymorphisms and risk of coal workers' pneumoconiosis in a Chinese population. Ji X, Wu B, Jin K, et al. Mol Biol Rep. 2014;41:4171–4176. doi: 10.1007/s11033-014-3100-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pneumoconiosis: current status and future prospects. Qi XM, Luo Y, Song MY, et al. Chin Med J (Engl) 2021;134:898–907. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000001461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.The clinical usefulness of mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration in patients with pneumoconiosis. Peng YF, Zhang QS, Luo WG. Int J Gen Med. 2023;16:3171–3177. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S417962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Anemia: evaluation and diagnostic tests. Cascio MJ, DeLoughery TG. Med Clin North Am. 2017;101:263–284. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2016.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.El Brihi J, Pathak S. StatPearls [Internet] Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Normal and abnormal complete blood count with differential. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Association between mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration and future depressive symptoms in women. Lee JM, Nadimpalli SB, Yoon JH, Mun SY, Suh I, Kim HC. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2017;241:209–217. doi: 10.1620/tjem.241.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Higher mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration is associated with worse prognosis of hepatorenal syndrome: a multicenter retrospective study. Sheng X, Chen W, Xu Y, Lin F, Cao H. Am J Med Sci. 2022;363:25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.amjms.2021.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lower mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration is associated with poorer outcomes in intensive care unit admitted patients with acute myocardial infarction. Huang YL, Hu ZD. Ann Transl Med. 2016;4:190. doi: 10.21037/atm.2016.03.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.The association between mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration and prognosis in patients with acute pulmonary embolism: a retrospective cohort study. Ruan Z, Li D, Hu Y, Qiu Z, Chen X. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2022;28:10760296221103867. doi: 10.1177/10760296221103867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lower mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration is associated with unfavorable prognosis of resected lung cancer. Qu X, Zhang T, Ma H, Sui P, Du J. Future Oncol. 2014;10:2149–2159. doi: 10.2217/fon.14.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Serum concentration of prostaglandin E2 as a diagnostic biomarker in patients with silicosis: a case-control study. Milovanović AP, Milovanović A, Srebro D, Pajic J, Stanković S, Petrović T. J Occup Environ Med. 2023;65:546–552. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000002848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Haematological and cytogenetic studies in workers occupationally exposed to cement dust. Jude AL, Sasikala K, Kumar RA, Sudha S, Raichel J. http://krepublishers.com/02-Journals/IJHG/IJHG-02-0-000-000-2002-Web/IJHG-02-2-069-138-2002-Abst-PDF/IJHG-02-2-095-099-2002-Jude/IJHG-02-2-095-099-2002-Jude_Ab.pdf Int J Hum Genet. 2002;2:95–99. [Google Scholar]

- 48.The effect of cement dust exposure on haematological and liver function parameters of cement factory workers in Sokoto, Nigeria. Mojiminiyi FB, Merenu IA, Ibrahim MT, Njoku CH. Niger J Physiol Sci. 2008;23:111–114. doi: 10.4314/njps.v23i1-2.54945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hematological changes in cement mill workers. Meo SA, Azeem MA, Arian SA, Subhan MM. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/257875964_Hematological_changes_in_cement_mill_workers. Saudi Med J. 2002;23:1386–1389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hematological parameters are acutely effected by cement dust exposure in construction workers. Farheen A, Hazari MA, Khatoon F, Sultana F, Qudsiya SM. Ann Med Physiol. 2017;1:31–35. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Toxic metals in cement induced hematological and DNA damage as well as carcinogenesis in occupationally-exposed block-factory workers in Lagos, Nigeria. Yahaya T, Oladele E, Salisu T, et al. Egyptian J Basic Applied Sci. 2022;9:499–509. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Effects of cement dust on the hematological parameters in Obajana cement factory workers. Emmanuel TF, Ibiam UA, Okaka ANC, Alabi OJ. https://eujournal.org/index.php/esj/article/view/6274 European Sci. 2015;11 [Google Scholar]

- 53.Association between PM10 concentrations and school absences in proximity of a cement plant in northern Italy. Marcon A, Pesce G, Girardi P, et al. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2014;217:386–391. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2013.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Impact of cement dust pollution on respiratory systems of Lafarge cement workers, Ewekoro, Ogun State, Nigeria. Chukwu MN, Ubosi NI. Glob J Pure Appl Sci. 2016;22:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cancer mortality and incidence in cement industry workers in Korea. Koh DH, Kim TW, Jang SH, Ryu HW. Saf Health Work. 2011;2:243–249. doi: 10.5491/SHAW.2011.2.3.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.The association of cadmium and lead exposures with red cell distribution width. Peters JL, Perry MJ, McNeely E, Wright RO, Heiger-Bernays W, Weuve J. PLoS One. 2021;16:0. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0245173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Inflammatory modulation of HSCs: viewing the HSC as a foundation for the immune response. King KY, Goodell MA. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:685–692. doi: 10.1038/nri3062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Impact of inflammation on early hematopoiesis and the microenvironment. Takizawa H, Manz MG. Int J Hematol. 2017;106:27–33. doi: 10.1007/s12185-017-2266-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Effects of exposure to cement dust on hemoglobin concentration and total count of RBC in cement factory workers. Ahmad R, Akhter QS. J Bangladesh Soc Physiol. 2018;13:68–72. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Relation between anemia and blood levels of lead, copper, zinc and iron among children. Hegazy AA, Zaher MM, Abd El-Hafez MA, Morsy AA, Saleh RA. BMC Res Notes. 2010;3:133. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-3-133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Clinical and molecular aspects of lead toxicity: an update. Mitra P, Sharma S, Purohit P, Sharma P. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2017;54:506–528. doi: 10.1080/10408363.2017.1408562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chaudhry HS, Kasarla MR. StatPearls [Internet] Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Microcytic hypochromic anemia. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Relationship between red blood cell indices (MCV, MCH, and MCHC) and major adverse cardiovascular events in anemic and nonanemic patients with acute coronary syndrome. Zhang Z, Gao S, Dong M, et al. Dis Markers. 2022;2022:2193343. doi: 10.1155/2022/2193343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.An overview of complete blood count sample rejection rates in a clinical hematology laboratory due to various preanalytical errors. Noor T, Imran A, Raza H, Umer S, Malik NA, Chughtai AS. Cureus. 2023;15:0. doi: 10.7759/cureus.34444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Optimization of laboratory workflow in clinical hematology laboratory with reduced manual slide review: comparison between Sysmex XE-2100 and ABX Pentra DX120. Hur M, Cho JH, Kim H, Hong MH, Moon HW, Yun YM, Kim JQ. Int J Lab Hematol. 2011;33:434–440. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-553X.2011.01306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Evaluation of ABX Pentra DX 120 and Sysmex XE-2100 in umbilical cord blood. Kim H, Hur M, Choi SG, et al. Int J Lab Hematol. 2013;35:658–665. doi: 10.1111/ijlh.12110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.US Department of Labour. Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Appendix C to § 1910.134: OSHA Respirator Medical Evaluation Questionnaire (Mandatory) [ Sep; 2023 ]. 2024. https://www.osha.gov/laws-regs/regulations/standardnumber/1910/1910.134AppC https://www.osha.gov/laws-regs/regulations/standardnumber/1910/1910.134AppC

- 68.Appendix F to § 1910.1051 - Medical Questionnaires (Non-Mandatory) [ May; 2024 ]. 2013. US Department of Labour. Occupational Safety and Health Administration, 1910.1051 App F-Medical Questionnaires (Non-Mandatory) [ Oct; 2023 ]. 2019. https://www.osha.gov/laws-regs/regulations/standardnumber/1910/1910.1051AppF https://www.osha.gov/laws-regs/regulations/standardnumber/1910/1910.1051AppF

- 69.BioRender. [ September; 2024 ]. 2024. http://www.biorender.com. BioRender. [ Sep; 2024 ]. 2024. http://www.biorender.com http://www.biorender.com

- 70.Socioeconomic status of the patients with acute coronary syndrome: data from a district-level general hospital of Bangladesh. Ahmed B, Shiraji KH, Chowdhury MHK, Uddin MG, Islam SN, Hossain S. Cardiovasc J. 2017;10:17–20. [Google Scholar]

- 71.The effect of occupational chronic lead exposure on the complete blood count and the levels of selected hematopoietic cytokines. Chwalba A, Maksym B, Dobrakowski M, Kasperczyk S, Pawlas N, Birkner E, Kasperczyk A. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2018;355:174–179. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2018.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Consequences of cement dust exposure on pulmonary function in cement factory workers. Shanshal SA, Al-Qazaz HK. Am J Ind Med. 2021;64:192–197. doi: 10.1002/ajim.23211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Occupational exposure to respirable dust, crystalline silica and its pulmonary effects among workers of a cement factory in Kermanshah, Iran. Omidianidost A, Gharavandi S, Azari MR, Hashemian AH, Ghasemkhani M, Rajati F, Jabari M. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7230124/pdf/Tanaffos-18-157.pdf. Tanaffos. 2019;18:157–162. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dust exposure in workers from grain storage facilities in Costa Rica. Rodríguez-Zamora MG, Medina-Escobar L, Mora G, Zock JP, van Wendel de Joode B, Mora AM. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2017;220:1039–1045. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2017.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Renal impairments in stone quarry workers. Bama R, Sundaramahalingam M, Anand N. Cureus. 2023;15:0. doi: 10.7759/cureus.48743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Exposure to welding fumes, hexavalent chromium, or nickel and risk of lung cancer. Pesch B, Kendzia B, Pohlabeln H, et al. Am J Epidemiol. 2019;188:1984–1993. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwz187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Construction and calibration of an exposure matrix for the welding trades. Galarneau JM. Ann Work Expo Health. 2022;66:178–191. doi: 10.1093/annweh/wxab071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Red cell distribution width and mean corpuscular volume alterations: detecting inflammation early in occupational cement dust exposure. Ahmad R, Haq MA, Sinha S, Lugova H, Kumar S, Haque M, Akhter QS. Cureus. 2024;16:0. doi: 10.7759/cureus.60951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Frequency of respiratory symptoms among rice mill workers in Bangladesh: a cross-sectional study. Choudhury SA, Rayhan A, Ahmed S, et al. Health Sci Rep. 2023;6:0. doi: 10.1002/hsr2.1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Effect on pulmonary functions of dust exposed rice mill workers in comparison to an unexposed population. Biswas M, Pranav PK, Nag PK. Work. 2023;74:945–953. doi: 10.3233/WOR-205146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Health risk of heavy metals in street dust. Aguilera A, Bautista F, Goguitchaichvili A, Garcia-Oliva F. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2021;26:327–345. doi: 10.2741/4896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Health and ecological risk assessment of potentially toxic metals in road dust at Lalibela and Sekota towns, Ethiopia. Taye AE, Chandravanshi BS. Environ Monit Assess. 2023;195:765. doi: 10.1007/s10661-023-11406-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Pollution and health risk of potentially toxic metals in urban road dust in Nanjing, a mega-city of China. Liu E, Yan T, Birch G, Zhu Y. Sci Total Environ. 2014;476-477:522–531. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.01.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Human health risk of mercury in street dust: a case study of children in the vicinity of compact fluorescence lamp factory, Hanoi, Vietnam. Dinh QP, Addai-Arhin S, Jeong H, et al. J Appl Toxicol. 2022;42:371–379. doi: 10.1002/jat.4222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Air contamination by mercury, emissions and transformations-a review. Gworek B, Dmuchowski W, Baczewska AH, Brągoszewska P, Bemowska-Kałabun O, Wrzosek-Jakubowska J. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2017;228:123. doi: 10.1007/s11270-017-3311-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Possible mechanisms of mercury toxicity and cancer promotion: involvement of gap junction intercellular communications and inflammatory cytokines. Zefferino R, Piccoli C, Ricciardi N, Scrima R, Capitanio N. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2017;2017:7028583. doi: 10.1155/2017/7028583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Adverse human health effects of chromium by exposure route: a comprehensive review based on toxicogenomic approach. Shin DY, Lee SM, Jang Y, Lee J, Lee CM, Cho EM, Seo YR. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:3410. doi: 10.3390/ijms24043410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Particles internalization, oxidative stress, apoptosis and pro-inflammatory cytokines in alveolar macrophages exposed to cement dust. Ogunbileje JO, Nawgiri RS, Anetor JI, Akinosun OM, Farombi EO, Okorodudu AO. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2014;37:1060–1070. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2014.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Potential biomarker of coal workers' pneumoconiosis. Kim KA, Lim Y, Kim JH, Kim EK, Chang HS, Park YM, Ahn BY. Toxicol Lett. 1999;108:297–302. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4274(99)00101-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Abnormal secretion of interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor alpha by alveolar macrophages in coal worker's pneumoconiosis: comparison between simple pneumoconiosis and progressive massive fibrosis. Lassalle P, Gosset P, Aerts C, et al. Exp Lung Res. 1990;16:73–80. doi: 10.3109/01902149009064700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Iron deficiency or anemia of inflammation?: Differential diagnosis and mechanisms of anemia of inflammation. Nairz M, Theurl I, Wolf D, Weiss G. Wien Med Wochenschr. 2016;166:411–423. doi: 10.1007/s10354-016-0505-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Inflammation, serum C-reactive protein, and erythropoietin resistance. Bárány P. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2001;16:224–227. doi: 10.1093/ndt/16.2.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Erythropoietin resistance: the role of inflammation and pro-inflammatory cytokines. Macdougall IC, Cooper AC. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2002;17 Suppl 11:39–43. doi: 10.1093/ndt/17.suppl_11.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry Office of Innovation and Analytics, Toxicology Section. Toxicological Profile for Lead. Vol. 95222. Washington, D.C., United States: US Department of Health and Human Services; [ Oct; 2024 ]. 2020. Toxicological Profile for Lead. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Mechanisms of nephrotoxicity from metal combinations: a review. Madden EF, Fowler BA. Drug Chem Toxicol. 2000;23:1–12. doi: 10.1081/dct-100100098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Calcium supplementation during lactation blunts erythrocyte lead levels and delta-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase zinc-reactivation in women non-exposed to lead and with marginal calcium intakes. Pires JB, Miekeley N, Donangelo CM. Toxicology. 2002;175:247–255. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(02)00091-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Impact of chronic lead exposure on selected biological markers. Jangid AP, John PJ, Yadav D, Mishra S, Sharma P. Indian J Clin Biochem. 2012;27:83–89. doi: 10.1007/s12291-011-0163-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Latest status of cadmium accumulation and its effects on kidneys, bone, and erythropoiesis in inhabitants of the formerly cadmium-polluted Jinzu River Basin in Toyama, Japan, after restoration of rice paddies. Horiguchi H, Aoshima K, Oguma E, et al. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2010;83:953–970. doi: 10.1007/s00420-010-0510-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Adverse impact of heavy metals on bone cells and bone metabolism dependently and independently through anemia. Zhang S, Sun L, Zhang J, Liu S, Han J, Liu Y. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1002/advs.202000383. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2020;7:2000383. doi: 10.1002/advs.202000383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Pyrimidine 5' nucleotidase deficiency. Rees DC, Duley JA, Marinaki AM. Br J Haematol. 2003;120:375–383. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.03980.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Structure of pyrimidine 5'-nucleotidase type 1. Insight into mechanism of action and inhibition during lead poisoning. Bitto E, Bingman CA, Wesenberg GE, McCoy JG, Phillips GN Jr. https://www.jbc.org/action/showPdf?pii=S0021-9258%2819%2976364-9. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:20521–20529. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602000200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hematological assessment of occupational exposure to lead handlers in Enugu urban, Enugu State, Nigeria. Ukaejiofo EO, Thomas N, Ike SO. https://www.ajol.info/index.php/njcp/article/view/45363. Niger J Clin Pract. 2009;12:58–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Biochemical and hematological effects of lead exposure in Iranian battery workers. Kargar-Shouroki F, Mehri H, Sepahi-Zoeram F. Int J Occup Saf Ergon. 2023;29:661–667. doi: 10.1080/10803548.2022.2064090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Iron deficiency screening is a key issue in chronic inflammatory diseases: a call to action. Cacoub P, Choukroun G, Cohen-Solal A, et al. J Intern Med. 2022;292:542–556. doi: 10.1111/joim.13503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Evaluation of the efficiency of the reticulocyte hemoglobin content on diagnosis for iron deficiency anemia in Chinese adults. Cai J, Wu M, Ren J, et al. Nutrients. 2017;9:450. doi: 10.3390/nu9050450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Cadmium and platinum suppression of erythropoietin production in cell culture: clinical implications. Horiguchi H, Kayama F, Oguma E, Willmore WG, Hradecky P, Bunn HF. Blood. 2000;96:3743–3747. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Advances in metal-induced oxidative stress and human disease. Jomova K, Valko M. Toxicology. 2011;283:65–87. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Toxic metals and oxidative stress part I: mechanisms involved in metal-induced oxidative damage. Ercal N, Gurer-Orhan H, Aykin-Burns N. Curr Top Med Chem. 2001;1:529–539. doi: 10.2174/1568026013394831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Cadmium induces anemia through interdependent progress of hemolysis, body iron accumulation, and insufficient erythropoietin production in rats. Horiguchi H, Oguma E, Kayama F. Toxicol Sci. 2011;122:198–210. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfr100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Cadmium blocks hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1-mediated response to hypoxia by stimulating the proteasome-dependent degradation of HIF-1alpha. Chun YS, Choi E, Kim GT, et al. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267:4198–4204. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 and cardiovascular disease. Semenza GL. Annu Rev Physiol. 2014;76:39–56. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021113-170322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.The role of oxidative stress in hemolytic anemia. Fibach E, Rachmilewitz E. Curr Mol Med. 2008;8:609–619. doi: 10.2174/156652408786241384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Heavy metals and human health: mechanistic insight into toxicity and counter defense system of antioxidants. Jan AT, Azam M, Siddiqui K, Ali A, Choi I, Haq QM. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16:29592–29630. doi: 10.3390/ijms161226183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Metal-induced oxidative stress: an evidence-based update of advantages and disadvantages. Khalid M, Hassani S, Abdollahi M. Curr Opin Toxicol. 2020;20:55–68. [Google Scholar]

- 115.Haematological alterations among cement loaders in Port Harcourt, Nigeria. Jacob RB, Obianuju Mba C, Deborah Iduh P. Asian J Med Health. 2020;18:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 116.Effects of occupational dust exposure on the health status of Portland cement factory workers. Manjula R, Praveena RV, Clevin RR, Ghattargi CH, Dorle AS, Lalitha DH. Int J Med Public Health. 2013;3:192–196. [Google Scholar]

- 117.Bone lesions in growing swine fed 3% cement kiln dust as a source of calcium. Pond WG, Yen JT, Hill DA, Ferrell CL, Krook L. J Anim Sci. 1982;54:82–88. doi: 10.2527/jas1982.54182x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Haematological changes among construction workers exposed to cement dust in West Bengal, India. Mandal A, Suva P. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=1e155bb002bd27030620c56c9f76bc90aafe5b6b Prog Health Sci. 2014;4:88–94. [Google Scholar]

- 119.Knowledge and practices related to occupational hazards among cement workers in United Arab Emirates. Ahmed HO, Newson-Smith MS. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=b01487faa27506cd73bcd967809cf696b46b9d9a. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. 2010;85:149–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Dust emission monitoring in cement plant mills: a case study in Romania. Ciobanu C, Istrate IA, Tudor P, Voicu G. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:9096. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18179096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]