Abstract

The transcription factor Pax5 activates genes essential for B-cell development and function. However, the regulation of Pax5 expression remains elusive. The adaptor Rack1 can interact with multiple transcription factors and modulate their activation and/or stability. However, its role in the transcriptional control of B-cell fates is largely unknown. Here, we show that CD19-driven Rack1 deficiency leads to pro-B accumulation and a simultaneous reduction in B cells at later developmental stages. The generation of bone marrow chimeras indicates a cell-intrinsic role of Rack1 in B-cell homeostasis. Moreover, Rack1 augments BCR and TLR signaling in mature B cells. On the basis of the aberrant expression of Pax5-regulated genes, including CD19, upon Rack1 deficiency, further exploration revealed that Rack1 maintains the protein level of Pax5 through direct interaction and consequently prevents Pax5 ubiquitination. Accordingly, Mb1-driven Rack1 deficiency almost completely blocks B-cell development at the pro-B-cell stage. Ectopic expression of Pax5 in Rack1-deficient pro-B cells partially rescues B-cell development. Thus, Rack1 regulates B-cell development and function through, at least partially, binding to and stabilizing Pax5.

Keywords: Rack1, Pax5, Ubiquitination, B-cell development, BCR signaling.

Subject terms: B cells, Haematological cancer

Introduction

B lymphocytes recognize foreign microbial antigens and mediate the production of antigen-specific antibodies, thereby providing humoral protection against infections [1]. The enormous adaptive potential of B cells results from successful rearrangements of the immunoglobulin (Ig) heavy chain (HC) and light-chain (LC) genes in the bone marrow (BM), leading to the generation of immature B cells expressing a membrane IgM B-cell receptor (BCR) [2]. Upon migration to peripheral lymphoid organs, these immature B cells, namely, transitional 1 (T1) and transitional 2 (T2) cells, differentiate into distinct mature B-cell types. The innate-like B1 cells in the pleural and peritoneal cavities and the marginal zone (MZ) B cells in the spleen respond vigorously to toll-like receptor (TLR) agonists and provide the first line of defense against pathogens by secreting IgM in a T-cell-independent manner [3, 4]. In contrast, follicular (FO) B cells in the spleen and lymph nodes are less responsive to TLR agonists and differentiate into germinal center (GC) B cells in T-cell-dependent immune responses to protein antigens [5]. Affinity-based selection in the GC subsequently leads to the clonal expansion of B cells expressing high-affinity B-cell receptors, which then differentiate into proliferating, antibody-secreting plasmablasts (PBs) [5]. Later, PBs differentiate into nonproliferating plasma cells (PCs) that secrete high amounts of antibodies [6].

B-cell development, from early pro-B cells to Ig-secreting PCs, is regulated by various extracellular signals and a panel of transcription factors [1]. Among the various transcriptional regulators, paired box 5 (Pax5) is essential for B-cell commitment [7], development [8], and function [9]. A mouse model expressing a patient-specific Pax5 mutant with impaired DNA binding showed pro-B accumulation and a simultaneous reduction in B cells at later developmental stages [10]. At the molecular level, Pax5 is exclusively expressed at all stages of B-cell development within the hematopoietic system [11]. It represses B lineage ‘inappropriate’ genes and simultaneously activates genes required for B-cell development and function [8, 9, 12–14]. One target gene of Pax5 is CD19, which encodes the costimulatory receptor of BCR signaling. Intriguingly, the transcription of CD19 depends entirely on Pax5 [15]. In mature B cells, Pax5 also restrains the expression of a negative regulator of phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) signaling, namely, phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN), likely by controlling the abundance of PTEN-targeting miRNAs [9]. Furthermore, chromosomal translocations involving PAX5 frequently occur in various human B-cell lymphomas and reportedly promote lymphomagenesis through stimulation of BCR signaling [16–20]. However, the regulation of Pax5 expression remains elusive.

The receptor for activated C kinase 1 (Rack1) contains seven Trp‒Asp (WD) repeats and functions as an adaptor protein. It can interact with multiple transcription factors and modulate their activation and/or stability. For example, Rack1 binds to STAT1 and STAT3 and facilitates their activation in response to type I interferons and growth factors, respectively [21, 22]. Rack1 also binds to Smad3 and hinders its ability to bind to DNA to modulate TGF-β1 signaling [23, 24]. On the other hand, Rack1 induces HIF-1α degradation [25, 26] but stabilizes Nanog [27] through direct interaction. Despite these findings, the role of Rack1 in the transcriptional control of B-cell fates has not been reported.

In this study, we report that Rack1 promotes B-cell development and function through, at least partially, direct binding to and stabilizing Pax5.

Results

Rack1 contributes to B-cell development

To explore the role of Rack1 in B cells, we crossed mice carrying the floxed Rack1 allele with mice expressing Cre recombinase under the control of the CD19 promoter to establish a B-cell-specific Rack1 knockout model, namely, Rack1f/f; CD19-Cre. Immunoblotting (IB) analysis of whole-cell lysates revealed Rack1 deficiency in splenic total B cells, but not thymocytes, purified from Rack1f/f;CD19-Cre mice compared with their counterparts isolated from littermate Rack1f/f mice (Fig. S1). Splenic CD19+B220+CD21intCD23hi FO B and CD19+B220+CD21hiCD23low/− MZ B cells from Rack1f/f and Rack1f/f; CD19-Cre mice were further sorted. PCR analysis revealed varied deletion efficiencies of the Rack1 allele in MZ B cells from different Rack1f/f; CD19-Cre mice but greater than 80% recombination efficiency in FO B cells from all Rack1f/f; CD19-Cre mice (Fig. S2). With this model, we first assessed B-cell development in the BM. Flow cytometry analysis revealed that compared with their control littermates, Rack1f/f; CD19-Cre mice presented fewer total CD19+B220+B cells in the BM (Fig. 1A, B). Among B220+ cells, the frequency of B220lowIgM− pro/pre-B and B220lowCD43+ pro-B increased, that of B220lowIgM+ immature B and B220lowCD43- pre-B/immature B remained unchanged, whereas that of B220hiIgM+ mature B and B220hiCD43− mature B/recirculating B decreased in the BM of Rack1f/f; CD19-Cre mice (Fig. 1A, C). Accordingly, the number of Pro-B cells remained unchanged, whereas the number of all the other subsets decreased (Fig. 1D). In the periphery, Rack1f/f;CD19-Cre mice presented a lower number of total splenic B cells than their control littermates did (Fig. 1E, F). Among splenic B cells, the frequencies of CD21intCD23hi FO B, CD21hiCD23low/− MZ B, IgMhiIgDlow T1 B, IgMhiIgDhi T2 B, and IgMlowIgDhi mature B cells were comparable between Rack1f/f and Rack1f/f; CD19-Cre mice (Fig. 1E, G). However, the number of all these splenic B-cell subsets in Rack1f/f; CD19-Cre mice decreased due to a reduction in total splenic B cells (Fig. 1E, H). Furthermore, Rack1f/f; CD19-Cre mice presented a more pronounced reduction in CD5+CD23−B1a cells, although the frequency of CD5−CD23−B1b and CD5−CD23+ B2 cells among leukocytes also decreased (Fig. 1I, J, K).

Fig. 1.

Rack1 contributes to B-cell development. A–D Flow cytometry analysis of B-cell development in the BM of 8-∼12-week-old Rack1f/f and Rack1f/f; CD19-Cre mice. Representative gating strategy (A), the number of CD19+B220+ total B cells (B), the frequency of B220lowIgM−pro/pre-B, B220lowIgM+ immature B, B220hiIgM+ mature B, B220lowCD43+ pro-B, B220lowCD43−pre-B/immature B, and B220hiCD43−mature B/recirculating B among B220+ cells (C), and the numbers of different B-cell subsets (D) are shown. The error bars represent the means ± SDs (n = 5 mice per group). P values were determined by two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test (B) or two-way ANOVA (C, D). The data are representative of two independent experiments. E–H Flow cytometry analysis of total splenic B cells in 8∼12-week-old Rack1f/f and Rack1f/f; CD19-Cre mice. Representative gating strategy (E), the number of CD19+B220+ total B cells (F), the frequency of CD21intCD23hi FO B, CD21hiCD23low/−MZ B, IgMhiIgDlow T1 B, IgMhiIgDhi T2 B, and IgMlowIgDhi mature B cells among total B cells (G), and the number of different B-cell subsets (H) are shown. The error bars represent the means ± SDs (n = 5 mice per group). P values were determined by two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test (F) or two-way ANOVA (G, H). The data are representative of two independent experiments. I–K Flow cytometry analysis of peritoneal B cells in 8-∼12-week-old Rack1f/f and Rack1f/f; CD19-Cre mice. Representative gating strategy (I), the frequencies of CD5+CD23−B1a, CD5−CD23−B1b, and CD5−CD23+ B2 cells among total B cells (J), and the frequencies of different B-cell subsets among peritoneal leukocytes (K) are shown. The error bars represent the means ± SDs (n = 5 mice per group). P values were determined by two-way ANOVA (J, K). The data are representative of two independent experiments

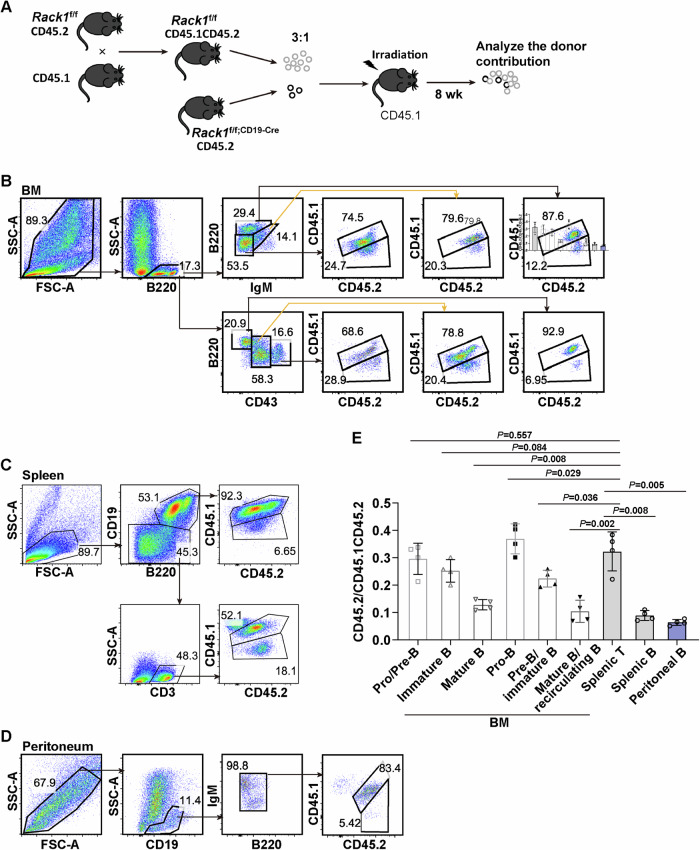

A cell-intrinsic role of Rack1 in B-cell homeostasis

To verify whether Rack1 maintains B-cell homeostasis in a cell-intrinsic way, we generated BM chimeras by transferring congenitally marked CD45.1CD45.2 Rack1f/f and CD45.2 Rack1f/f; CD19-Cre BM cells at a ratio of 3:1 into sublethally irradiated CD45.1 recipients. After 8 weeks of BM reconstitution, flow cytometry analysis was used to examine the chimerism of B lineage cells (Fig. 2A). Compared with the CD45.1−CD45.2+ to CD45.1+CD45.2+ ratio in splenic CD19−B220−CD3+ T cells of the chimeras (Fig. 2C, E), that in BM B220lowCD43+ pro-B was slightly greater (Fig. 2B, E), that in BM B220lowIgM−pro/pre-B remained unchanged (Fig. 2B, E), that in BM B220lowIgM+ immature B and BM B220lowCD43−pre-B/immature B was slightly lower (Fig. 2B, E), whereas that in BM B220hiIgM+ mature B (Fig. 2B, E), BM B220hiCD43−mature B/recirculating B (Fig. 2B, E), splenic total B (Fig. 2C, E), and peritoneal total B (Fig. 2D, E) was significantly lower. Thus, chimerism partially abrogated the role of Rack1 in B-cell development but simultaneously exaggerated its role in mature B cells.

Fig. 2.

A cell-intrinsic role of Rack1 in B-cell homeostasis. A Schematic representation of the BM transplantation experiment. B–D Exemplary flow cytometric analysis of CD45.1 and CD45.2 expression on various subsets in the BM (B), spleen (C), and peritoneal cavity (D) of chimeric mice 8 weeks after BM transplantation. E Quantification of the CD45.1−CD45.2+ to CD45.1+CD45.2+ ratios in the indicated subsets. The error bars represent the means ± SDs (n = 4 chimeric mice). P values compared with those of T cells were determined via two-tailed paired Student’s t-test

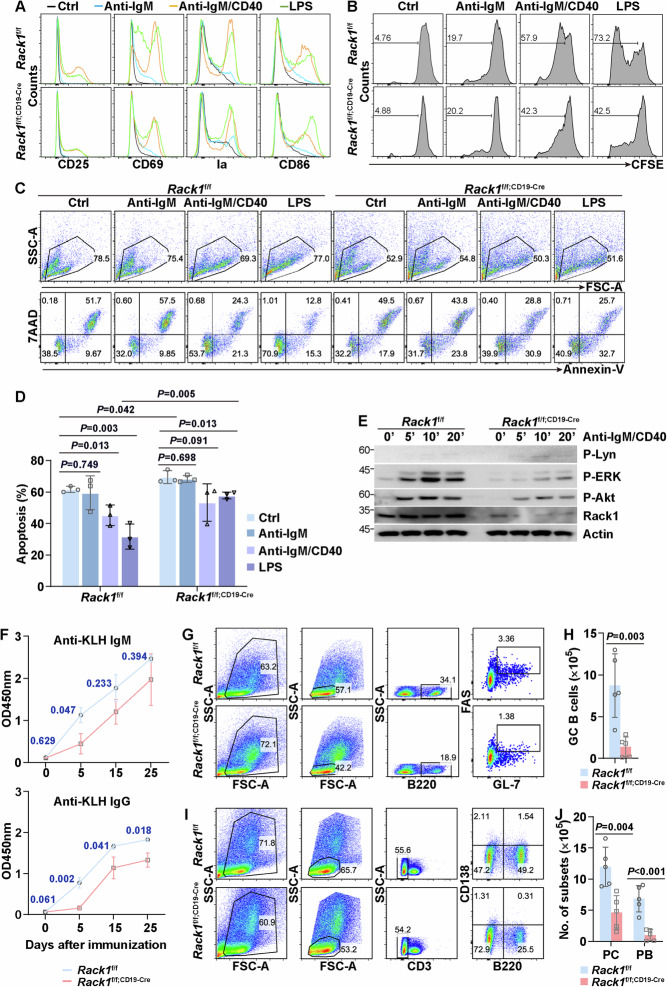

Rack1 augments BCR and TLR signaling in mature B cells

We next explored how Rack1 affects the response of mature B cells to BCR or TLR stimulation. First, we checked B-cell activation. The ability of anti-IgM to upregulate CD25, CD69, MHC-II molecule Ia, and CD86 was weak (Fig. 3A). The combination of anti-IgM and anti-CD40 antibodies significantly induced the upregulation of CD25, CD69, Ia, and CD86, which were all partially impaired in the absence of Rack1 (Fig. 3A). The TLR4 agonist LPS also upregulated these molecules. Although Rack1 deficiency had marginal effects on the LPS-induced upregulation of CD25, Ia, and CD86, it partially blocked the LPS-induced upregulation of CD69 (Fig. 3A). In line with these data, anti-IgM only weakly promoted B-cell proliferation, as demonstrated by CFSE dilution (Fig. 3B). Both anti-IgM plus anti-CD40 antibody and LPS significantly induced B-cell proliferation, which was partially abrogated in the absence of Rack1 (Fig. 3B). Without any stimulation, B cells undergo apoptosis in vitro. Anti-IgM plus anti-CD40 and LPS significantly blocked B-cell apoptosis, although anti-IgM alone had no effect (Fig. 3C, D). Rack1 deficiency slightly enhanced the apoptosis of B cells without any stimulation and hindered the reversal effects of anti-IgM plus anti-CD40 and LPS (Fig. 3C, D). Accordingly, anti-IgM plus anti-CD40 stimulation-triggered activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) and Akt diminished in the absence of Rack1, whereas the activation of the upstream tyrosine kinase Lyn, a key component of BCR signaling, remained largely unchanged (Fig. 3E). In this context, we immunized Rack1f/f and Rack1f/f;CD19-Cre mice with the T-cell-dependent antigen keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH) in complete Freund’s adjuvant to study the role of Rack1 in specific antibody production. The two genotypes of mice had comparable background levels of anti-KLH IgM and anti-KLH IgG (Fig. 3F). Five days after immunization, the upregulation of anti-KLH IgM and anti-KLH IgG was impaired in Rack1f/f; CD19-Cre mice compared with Rack1f/f mice (Fig. 3F). The reduction in anti-KLH IgM in Rack1f/f; CD19-Cre mice failed to reach statistical significance 15 and 25 days after immunization, whereas that of anti-KLH IgG remained significant at all time points detected (Fig. 3F). Moreover, the numbers of B220+Fas+GL-7+ germinal center (GC) B cells (Fig. 3G, H), CD3−CD138+B220+ plasmablasts (PBs) (Fig. 3I, J), and CD3−CD138+B220−plasma cells (PCs) (Fig. 3I, J) in the spleen after the third KLH immunization were reduced in the absence of Rack1.

Fig. 3.

Rack1 augments BCR and TLR signaling in mature B cells. A Total B cells were purified from 8∼12-week-old Rack1f/f and Rack1f/f; CD19-Cre mice were treated with anti-IgM, anti-IgM plus anti-CD40, or LPS or left untreated for 48 h. Then, the expression of CD25, CD69, Ia, and CD86 was examined via flow cytometry. The data are representative of three independent experiments. B Total B cells were purified from 8∼12-week-old Rack1f/f and Rack1f/f; CD19-Cre mice were labeled with CFSE, followed by BCR or TLR stimulation as indicated for 72 h. Then, CFSE dilution was measured via flow cytometry. The data are representative of three independent experiments. C, D Total B cells were purified from 8∼12-week-old Rack1f/f and Rack1f/f; CD19-Cre mice were treated with anti-IgM, anti-IgM plus anti-CD40, LPS, or left untreated for 48 h. Then, apoptosis was detected by flow cytometry after Annexin-V/7-AAD staining. The error bars represent the means ± SDs (n = 3 mice per group). P values were determined by two-way ANOVA. The data are representative of two independent experiments. E Total B cells were purified from 8∼12-week-old Rack1f/f and Rack1f/f; CD19-Cre mice were treated with anti-IgM plus anti-CD40 for various periods of time as indicated. Then, whole-cell lysates were prepared and subjected to IB with the indicated antibodies. P-Lyn phospho-Lyn at Tyr507, P-ERK phospho-ERK1/2 at Thr202/Tyr204, P-Akt phospho-Akt at Ser473. The data are representative of three independent experiments. F 8∼12-week-old Rack1f/f and Rack1f/f; CD19-Cre mice were immunized with KLH in complete Freund’s adjuvant for primary immunization (day 0) and in incomplete Freund’s adjuvant on days 10 and 20. The serum was collected on days 5, 15, and 25. The levels of anti-KLH IgM and anti-KLH IgG were determined via ELISA. The error bars represent the means ± SDs (n = 5 mice per group). P values were determined by two-way ANOVA. The data are representative of two independent experiments. G–J The mice in (F) were sacrificed on day 25. B220+Fas+GL-7+ GC B cells (G, H), CD3−CD138+B220+ PB (I, J), and CD3−CD138+B220−PC (I, J) in the spleen were analyzed via flow cytometry. The error bars represent the means ± SDs (n = 5 mice per group). P values were determined by two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test (H) or two-way ANOVA (J). The data are representative of two independent experiments

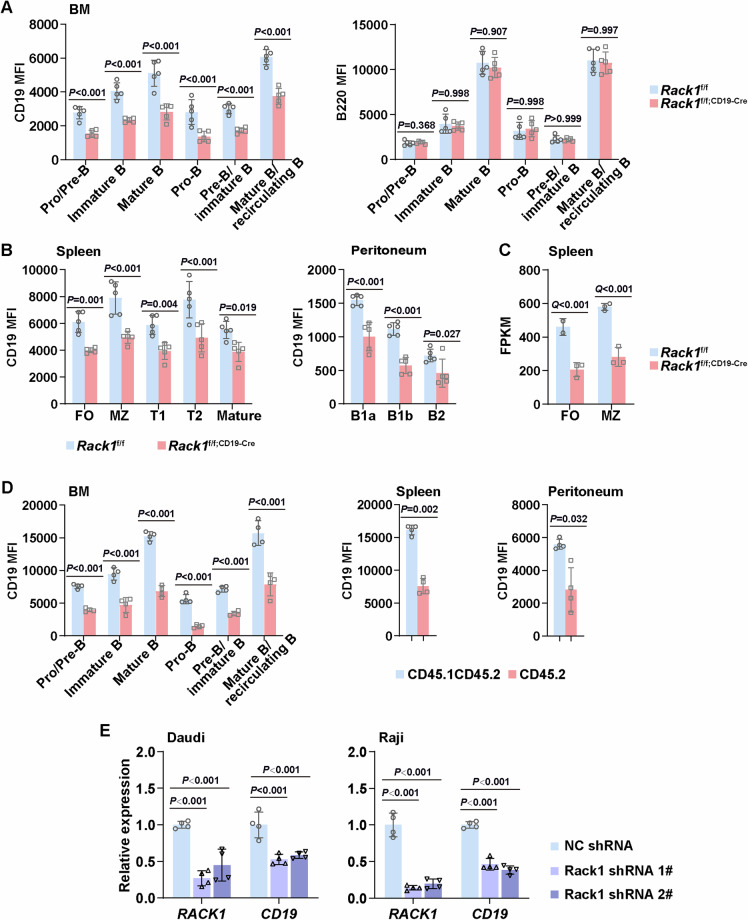

Rack1 is essential for CD19 expression

Next, we explored the mechanism(s) underlying impaired BCR signaling in the absence of Rack1. We reexamined the flow cytometry data of B-cell development in the BM of Rack1f/f and Rack1f/f; CD19-Cre mice and noted that Rack1 deficiency led to a reduced mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of CD19, but not that of B220, in all the subsets examined (Fig. 4A). Similarly, B-cell subsets in the spleen and peritoneal cavity of Rack1f/f; CD19-Cre mice presented a lower CD19 MFI than did their counterparts in Rack1f/f mice (Fig. 4B). Bulk RNA sequencing of sorted splenic FO B and MZ B cells from Rack1f/f and Rack1f/f;CD19-Cre mice revealed that a reduction in CD19 expression occurred at the mRNA level (Fig. 4C). The reduced CD19 expression in the absence of Rack1 is cell autonomous because such a defect was also observed in chimeras (Fig. 4D). Accordingly, silencing endogenous Rack1 with short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) in Daudi and Raji cells, which are human B lymphocytes from Burkitt’s lymphoma patients, led to reduced mRNA levels of CD19 (Fig. 4D). Thus, Rack1 is essential for CD19 expression.

Fig. 4.

Rack1 is essential for CD19 expression. A Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of CD19 and B220 in the subsets examined in Fig. 1C. The error bars represent the means ± SDs (n = 5 mice per group). P values were determined by two-way ANOVA. The data are representative of two independent experiments. B MFI of CD19 in the subsets examined in Fig. 1G, J. Error bars represent the mean ± SD (n = 5 mice per group). P values were determined by two-way ANOVA. The data are representative of two independent experiments. C Splenic FO B and MZ B cells from 8∼12-week-old Rack1f/f and Rack1f/f; CD19-Cre mice (n = 3 per group) were sorted and subjected to bulk RNA sequencing. The fragment/kb of transcript/million mapped reads (FPKM) values of Cd19 (mean ± SD) in these two subsets are shown with false discovery rate (Q) values above. Notably, one Rack1f/f FO B-cell sample failed to pass quality control and was not included. D MFI of CD19 in the subsets examined in Fig. 2. Error bars show the means ± SDs (n = 4 chimeric mice). P values were determined by two-way ANOVA (BM) or two-tailed paired Student’s t-test (spleen and peritoneal cavity). E At 96 h after infection with lentiviral vectors carrying the indicated shRNAs, Daudi and Raji cells were subjected to quantitative RT‒PCR analysis to examine RACK1 and CD19 expression (n = 4 per group). P values were determined by one-way ANOVA. The data are representative of two independent experiments

Rack1 maintains the protein level of Pax5

Our aforementioned data indicate that Rack1 deficiency leads to a reduced mRNA level of CD19. The transcription of CD19 depends entirely on Pax5 [15]. Intriguingly, Rack1 deficiency had no effect on the mRNA level of Pax5 in either FO B or MZ B cells, as revealed by bulk RNA sequencing (Fig. 5A). Pax5 target genes reported by different groups vary dramatically, possibly because of the different B-cell subsets analyzed, different strategies of Pax5 deletion, and different postmortem intervals [8, 9, 12−14]. We identified 37 Pax5-regulated genes in mature B cells reported in at least two previous studies (Table S1). On the basis of our bulk RNA-sequencing data, we checked the expression of these genes in FO B cells because this subset exhibited better CD19-Cre-mediated recombination of the conditional Rack1 allele than did MZ B cells (Fig. S2). As expected, more than half of the Pax5-repressed genes tended to be upregulated in the absence of Rack1, whereas all Pax5-activated genes tended to be downregulated (Table S1 and Fig. S3), suggesting impaired Pax5 function in the absence of Rack1. Indeed, KEGG enrichment analysis of genes significantly differentially expressed between Rack1-deficient and Rack1-sufficient FO B cells revealed aberrant “efferocytosis”, “complement and coagulation cascades”, “osteoclast differentiation”, “ECM-receptor interaction”, “hematopoietic cell lineage”, “platelet activation”, etc. (Fig. S4), indicating defective maintenance of B-cell features. An impaired PI3K-Akt signaling pathway was also observed in the absence of Rack1 (Fig. S4). Furthermore, flow cytometry analysis revealed that peritoneal cavity B1a, B1b, and B2 cells in Rack1f/f; CD19-Cre mice tended to express more CD11b, a lineage marker for myeloid cells, than their counterparts in littermate Rack1f/f mice did (Fig. S5). These findings prompted us to investigate how Rack1 deficiency might affect the protein level of Pax5. IB analysis of total splenic B cells purified from Rack1f/f and Rack1f/f; CD19-Cre mice revealed that Rack1 deficiency led to a reduction in Pax5 and CD19 at the protein level (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Rack1 maintains the protein level of Pax5. A According to the bulk RNA-sequencing data shown in Fig. 4C, the FPKM values of Pax5 (mean ± SD) in splenic FO B and MZ B cells are shown with the Q values above. B IB analysis of Pax5, CD19, Rack1, and β-actin expression in splenic total B cells purified from 8-∼12-week-old Rack1f/f and Rack1f/f; CD19-Cre mice. The data are representative of three independent experiments. C Samples shown in Fig. 4E were subjected to quantitative RT‒PCR analysis of PAX5 expression. The error bars represent the means ± SDs. P values were determined by one-way ANOVA. The data are representative of two independent experiments. D At 96 h after infection with lentiviral vectors carrying the indicated shRNAs, Daudi and Raji cells were subjected to IB analysis to examine Pax5, CD19, Rack1, and β-tubulin expression. The data are representative of two independent experiments. E–G In vivo tumorigenicity experiments with Daudi (n = 12 per group) and Raji (n = 11 per group) cells with or without Rack1 knockdown. Images (E), volumes (F), and weights (G) of the subcutaneous tumors are shown. The error bars represent the means ± SDs. P values were determined via two-tailed paired Student’s t-test. H–J Forty-seven clinical lymphoma tissues, ten adjacent normal lymph node tissues, and ten spleen tissues were examined for Rack1 and Pax5 staining on tissue microarray slides. Representative paired samples (H, scale bar: 50 μm), comparison of Rack1 and Pax5 protein levels between clinical lymphoma tissues and normal tissues, including normal lymph node tissues and spleen tissues (I), and Spearman’s rank correlation of Rack1 and Pax5 protein levels in clinical lymphoma tissues (J) are shown. The error bars represent the means ± SDs, with P values determined via two-tailed paired Student’s t-test

Similarly, Rack1 knockdown was associated with an unchanged mRNA level of Pax5 (Fig. 5C) but reduced protein levels of Pax5 and CD19 (Fig. 5D) in Daudi and Raji cells. Pax5 promotes B-cell lymphomagenesis [20, 28]. Indeed, Pax5 knockdown in Daudi and Raji cells resulted in impaired in vivo tumor growth (Fig. S6). In this context, we explored how Rack1 might affect the oncogenic growth of Daudi and Raji cells. A soft agar assay revealed that Rack1 knockdown hindered the colony-forming ability of Daudi and Raji cells (Fig. S7). Furthermore, Rack1 knockdown led to impaired in vivo tumor growth (Fig. 5E–G). Accordingly, immunohistochemistry (IHC) revealed that, compared with adjacent normal lymph node tissues and spleen tissues, clinical lymphoma tissues presented elevated protein levels of Rack1 and Pax5 (Fig. 5H, I). Notably, the protein level of Rack1 was positively associated with that of Pax5 (Fig. 5H, J).

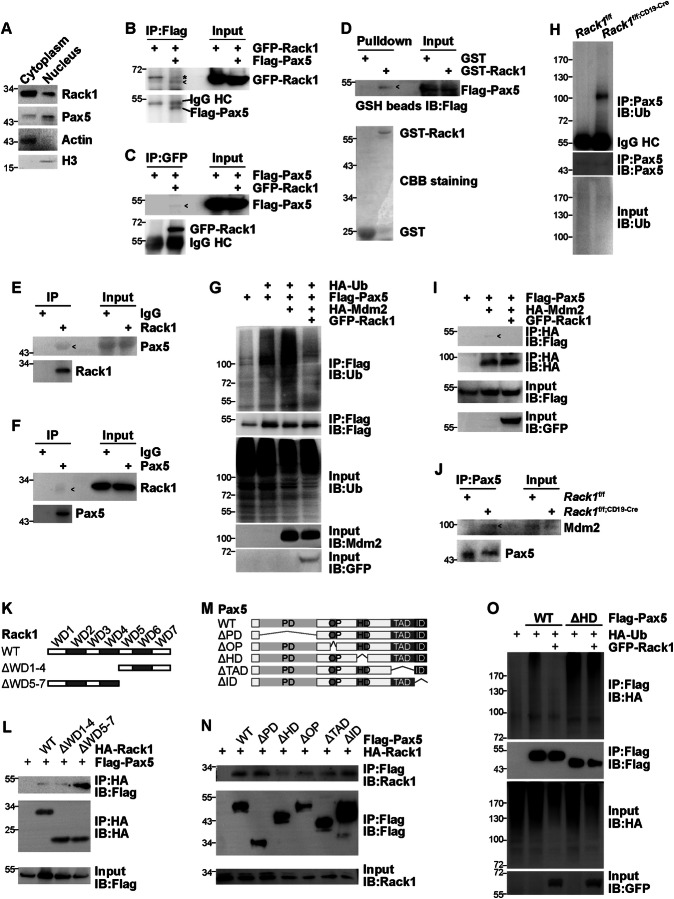

Rack1 maintains the protein level of Pax5 through direct binding

As Rack1 is a multifunctional scaffold protein, it is possible that Rack1 maintains the protein level of Pax5 by directly binding to it. To test this hypothesis, we first examined the possible subcellular colocalization of Rack1 and Pax5. Nuclear fractionation and subsequent immunoblotting revealed that Rack1 was predominantly cytoplasmic, with a considerable fraction in the nucleus, whereas Pax5 was predominantly nuclear, with a considerable fraction in the cytoplasm of splenic B cells (Fig. 6A), which is in line with the immunohistochemistry data (Fig. 5H). Computer-guided homology modeling and molecular docking were subsequently employed to explore the possible interaction between Rack1 and Pax5. The 3-D modeling structure of mouse Pax5 was obtained via the alphafold structure prediction method (Fig. S8A). The 3-D optimized structure of mouse Rack1 was obtained via a computer-guided homology modeling method (Fig. S8B). Furthermore, the 3-D complex structure of mouse Pax5 and Rack1 was obtained via the distance geometry method (Fig. S8C). Accordingly, coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP) revealed the interaction between exogenous tagged Rack1 and Pax5 in HEK-293T cells (Fig. 6B, C). Next, we tested whether Rack1 directly interacts with Pax5 by performing an in vitro GST pull-down assay. We detected substantial amounts of exogenous Flag-Pax5 in the lysates of HEK-293T cells, which was precipitated specifically by GST-Rack1 but not by GST alone (Fig. 6D). The possible physiological interaction of Rack1 with Pax5 in B cells was further analyzed via the immunoprecipitation of endogenous proteins. Pax5 was present in immunoprecipitates obtained from splenic total B cells with an antibody against Rack1, whereas no Pax5 coprecipitated with a control antibody (Fig. 6E). Moreover, endogenous Rack1 in total splenic B cells coprecipitated with endogenous Pax5 (Fig. 6F).

Fig. 6.

Rack1 maintains the protein level of Pax5 through direct binding. A The subcellular localization of Rack1 and Pax5 in splenic B cells was examined via nuclear-cytoplasmic fractionation and subsequent IB. beta-actin is a cytoplasmic marker, and histone H3 is a nuclear marker. B, C At 24 h after the transfection of HEK-293T cells with the indicated mammalian expression vectors, the cell lysates were harvested and subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) with the indicated antibodies. The precipitates were then subjected to IB with the indicated antibodies. Notably, exogenous Flag-Pax5 encodes the longest isoform of Pax5, with a molecular weight of 52 kDa. D GST or GST-Rack1 bound to glutathione-Sepharose (GSH) beads was incubated with lysates of HEK-293T cells expressing Flag-Pax5. The precipitates were subjected to IB with an anti-Flag antibody. E, F IB analysis of the interaction between endogenous Rack1 and endogenous Pax5 in lysates of splenic total B cells after IP with an anti-Rack1 Ab (E control antibody: rabbit IgG) or an anti-Pax5 Ab (F control antibody: rabbit IgG). G At 24 h after transfection with the indicated mammalian expression vectors, HEK-293T cells were treated with 20 µM MG132 for 6 h. Ubiquitination of Flag-Pax5 was analyzed by IB after IP with an anti-Flag antibody. H Splenic total B cells purified from 8∼12-week-old Rack1f/f and Rack1f/f; CD19-Cre mice were treated with 20 µM MG132 for 6 h. Ubiquitination of endogenous Pax5 was analyzed via IB after IP with an anti-Pax5 antibody. I At 24 h after the transfection of HEK-293T cells with the indicated mammalian expression vectors, the interaction between Flag-Pax5 and HA-Mdm2 with Rack1 overexpression was analyzed via IB after IP with an anti-HA antibody. J IB analysis of the interaction between endogenous Pax5 and endogenous Mdm2 in lysates of total splenic B cells after IP with an anti-Pax5 Ab. K Diagrammatic representation of deletion mutants of Rack1 used in domain-mapping experiments. WD, Trp-Asp repeat. L The interaction between Pax5 and HA-tagged Rack1 WT or truncated mutants in HEK-293T cells was analyzed via IB after IP with an anti-HA antibody. M Diagrammatic representation of deletion mutants of Pax5 used in domain-mapping experiments. PD paired domain, OP octapeptide motif, HO partial homeodomain, TAD transactivation domain; ID inhibitory domain. N The interaction between Rack1 and Flag-tagged Pax5 WT or truncated mutant Pax5 in HEK-293T cells was analyzed via IB after IP with an anti-Flag antibody. O HEK-293T cells transfected with the indicated plasmids were treated with 20 µM MG132 for 6 h. Ubiquitination of Flag-tagged Pax5 WT or ΔHD was analyzed by IB after IP with an anti-Flag antibody. All data in this figure are representative of two independent experiments. *, nonspecific band; ˂, coprecipitated band; HC heavy chain

To this end, we used HEK-293T cells to explore whether Rack1 affects Pax5 ubiquitination. We propose that mouse double minute 2 (Mdm2) might be a ubiquitination E3 ligase for Pax5. Under partially denaturing conditions, immunoprecipitation revealed that exogenous Pax5 underwent ubiquitination. Mdm2 overexpression augmented the ubiquitination of exogenous Pax5, which was blocked by Rack1 overexpression (Fig. 6G). Furthermore, Rack1 deficiency led to increased ubiquitination of endogenous Pax5 in splenic total B cells (Fig. 6H). Accordingly, coimmunoprecipitation analysis revealed an interaction between tagged Mdm2 and Pax5 in HEK-293T cells, which was abrogated by Rack1 overexpression (Fig. 6I). More importantly, coimmunoprecipitation analysis confirmed increased binding of endogenous Mdm2 to endogenous Pax5 in Rack1-deficient total splenic B cells (Fig. 6J).

We further analyzed the Rack1/Pax5-interacting regions. Rack1 contains seven WD repeats, whereas Pax5 is composed of five functional domains: the paired domain (PD), octapeptide motif (OP), partial homeodomain (HD), transactivation domain (TAD), and inhibitory domain (ID) [10]. With expression constructs encoding Rack1 truncated mutants without WD repeats 1∼4 (ΔWD1-4) or 5∼7 (ΔWD5-7) (Fig. 6K), co-IP analysis of HEK-293T cells demonstrated that Pax5 coprecipitated with either deletion mutant of Rack1 (Fig. 6L). Thus, multiple WD repeats can play a redundant role in anchoring Pax5. We subsequently generated expression constructs encoding Pax5 truncation mutants lacking each of its five functional domains (Fig. 6M). Co-IP analysis of HEK-293T cells revealed that, among wild-type (WT) Pax5 and its mutants, the HD-truncated mutant (ΔHD) presented the weakest interaction with Rack1 (Fig. 6N). Thus, HD is the major domain by which Pax5 anchors Rack1. GFP-Rack1 did not affect the ubiquitination of Flag-Pax5 ΔHD in HEK-293T cells under the conditions it potently inhibited that of Flag-Pax5 WT (Fig. 6O). Together, these data indicate that Rack1 prevents Pax5 ubiquitination through direct binding.

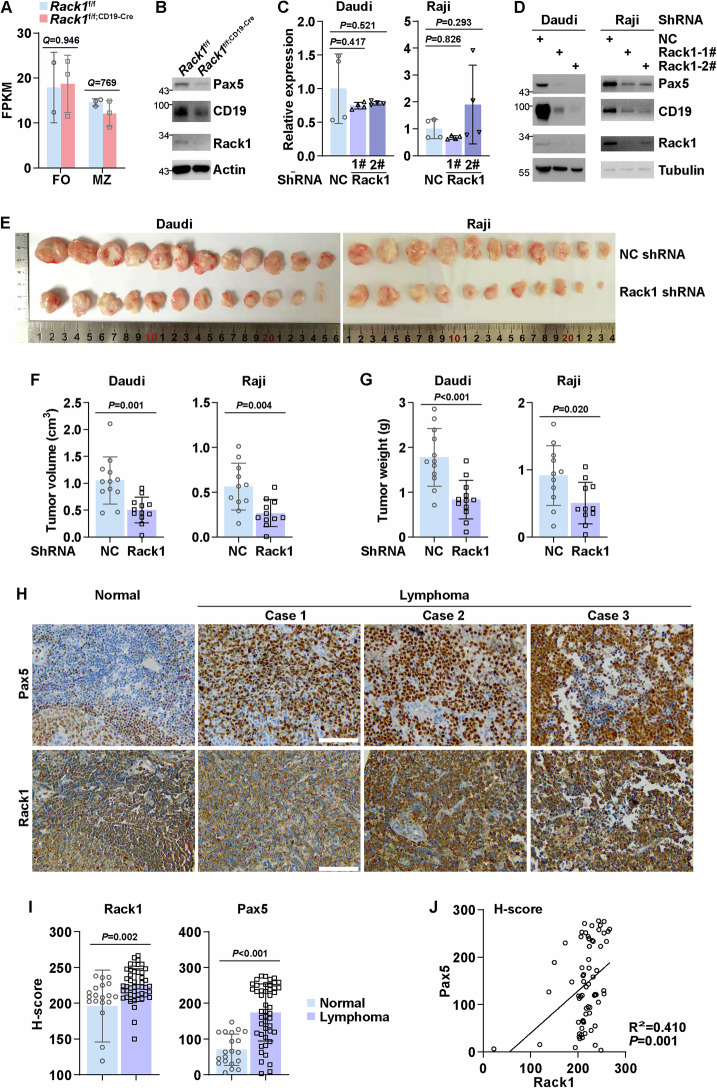

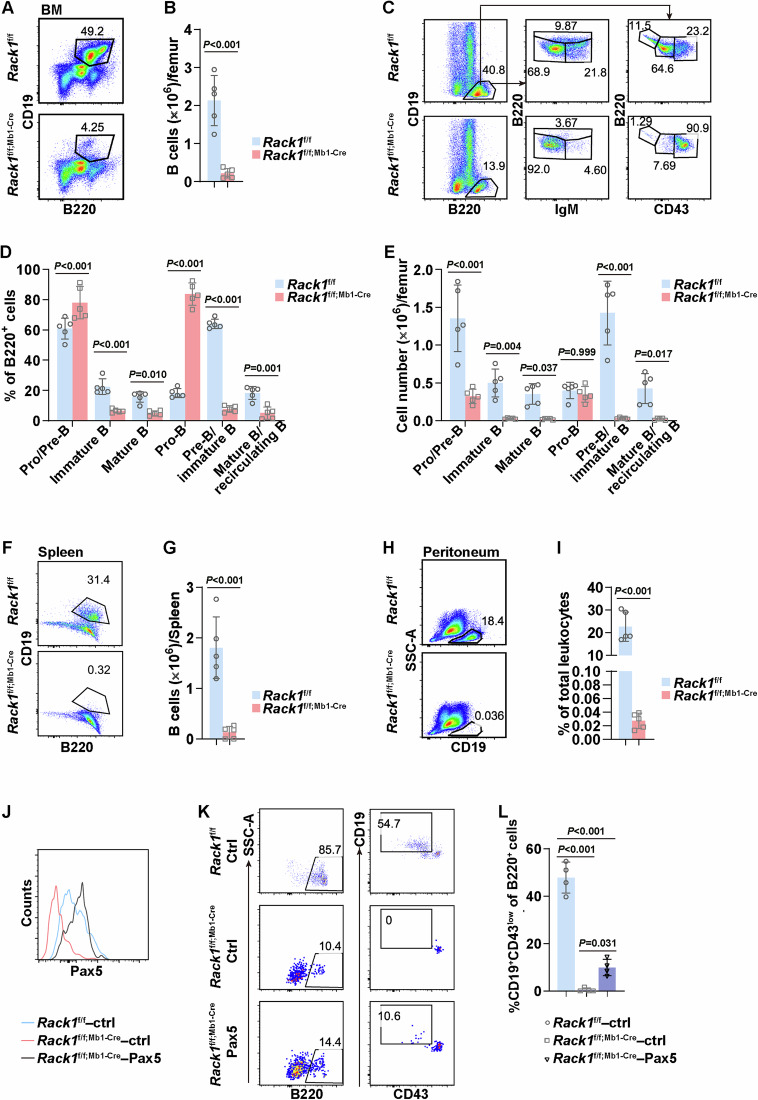

Rack1 is indispensable for early B-cell development through maintaining Pax5 protein levels

In CD19-Cre transgenic mice, Cre expression is activated at the late stage of pro-B [29]. Therefore, deletion of the Rack1 gene in pro-B cells of Rack1f/f; CD19-Cre mice should be partial. Our aforementioned data demonstrated that Rack1 maintains the protein level of Pax5. Given that Pax5 is essential for the transition from pro-B cells to pre-B cells [30], the role of Rack1 in B-cell development has been underestimated in Rack1f/f; CD19-Cre mice. In this scenario, we crossed Rack1f/f mice with Mb1-Cre transgenic mice, in which efficient deletion of loxP-site flanked alleles occurs at the very early stage of Pro-B [31]. Rack1f/f; Mb1-Cre mice appeared healthy. Then, we assessed B-cell development in the BM. Flow cytometry analysis demonstrated that Rack1f/f;Mb1-Cre mice presented a significantly lower frequency and number of CD19+B220+ total B cells in the BM than their littermate controls did (Fig. 7A, B). In detail, the frequency of B220lowIgM−pro/pre-B and B220lowCD43+ pro-B increased, whereas that of all the other subsets decreased in the BM of Rack1f/f; Mb1-Cre mice (Fig. 7C, D). Rack1f/f; Mb1-Cre mice and their littermate controls presented comparable numbers of pro-B cells in the BM (Fig. 7C, E). However, the number of all the other subsets decreased in the BM of Rack1f/f; Mb1-Cre mice (Fig. 7C, E). Accordingly, few B cells remained in the spleen (Fig. 7F, G) or peritoneal cavity (Fig. 7H, I) of Rack1f/f; Mb1-Cre mice. Therefore, B-cell development in Rack1f/f; Mb1-Cre mice was arrested at the pro-B-cell stage.

Fig. 7.

Rack1 is indispensable for early B-cell development through maintaining Pax5 protein levels. A–E Flow cytometry analysis of B-cell development in the BM of 4-week-old Rack1f/f and Rack1f/f; Mb1-Cre mice. Representative gating strategies for total B cells (A) and different B-cell subsets (C), the number of total B cells (B), the frequency of different B-cell subsets (D), and the number of different B-cell subsets (E) are shown. The error bars represent the means ± SDs (n = 5 mice per group). P values were determined by two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test (B) or two-way ANOVA (D, E). The data are representative of three independent experiments. F–I Flow cytometry analysis of total B cells in the spleen (F, G) and peritoneal cavity (H, I) of 4-week-old Rack1f/f and Rack1f/f; Mb1-Cre mice. A representative gating strategy (F, H), the number of total splenic B cells (G), and the frequency of peritoneal B cells among peritoneal leukocytes (I) are shown. The error bars represent the means ± SDs (n = 5 mice per group). P values were determined by two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test (G, I). The data are representative of three independent experiments. J–L Sorted CD19−B220+CD43hi pro-B cells from Rack1f/f and Rack1f/f; Mb1-Cre mice were stimulated with IL-7 for 24 h, followed by transduction with empty control (ctrl) or Pax5 ectopic expression retrovirus. Pax5 protein levels in transduced (GFP+) cells were examined by flow cytometry 24 h later (J). GFP+ cells were subsequently sorted and cultured in the presence of IL-7 for 7 d, followed by flow cytometry analysis of B-cell differentiation. The error bars represent the means ± SDs (n = 4 mice per group). P values were determined by one-way ANOVA (L). The data are representative of two independent experiments

To address whether a reduced protein level of Pax5 is the major factor involved in B-cell developmental arrest in Rack1f/f; Mb1-Cre mice, we performed a Pax5 complementation experiment. CD19−B220+CD43hi pro-B cells from Rack1f/f; Mb1-Cre mice were sorted and transduced with an MSCV-Pax5-IRES-GFP retroviral vector (Pax5 ectopic expression). CD19−B220+CD43hi pro-B cells from Rack1f/f and Rack1f/f; Mb1-Cre mice transduced with MSCV-IRES-GFP (empty vector) served as controls. The protein level of Pax5 in Rack1-deficient pro-B cells was lower than that in their Rack1-sufficient counterparts, which was fully reversed by MSCV-Pax5-IRES-GFP transduction (Fig. 7J). When CD19−B220+CD43hi pro-B cells from Rack1f/f mice efficiently differentiated into CD19+B220+CD43low cells, CD19−B220+CD43hi pro-B cells from Rack1f/f; Mb1-Cre mice failed to differentiate. As anticipated, retrovirus-mediated ectopic expression of Pax5 in these Rack1-deficient pro-B cells partially restored the generation of CD19+B220+CD43low cells (Fig. 7K, L). Thus, Rack1 is indispensable for early B-cell development through, at least partially, maintaining Pax5 protein levels.

Discussion

This work indicates that Rack1 plays a pivotal role in B-cell biology. Mb1-driven Rack1 deficiency almost completely blocks B-cell development at the pro-B-cell stage. Few peripheral B cells can be found in Rack1f/f; Mb1-Cre mice. The effects of CD19-driven Rack1 deficiency on B cells are less pronounced. Approximately half of the various splenic B-cell subsets remain in Rack1f/f; CD19-Cre mice. In the peritoneum, the reduction in B cells seems to be more drastic. Among peritoneal B cells, B1a cells are the most sensitive to Rack1 deficiency. Intriguingly, the chimerism of CD45.1CD45.2 Rack1f/f and CD45.2 Rack1f/f; CD19-Cre BM cells partially abrogated the role of Rack1 in B-cell development but simultaneously exaggerated its role in mature B cells. Thus, the pro-B accumulation in Rack1f/f; CD19-Cre mice might be partially due to compensation for the reduction in peripheral B cells. These data also suggest additional effects of Rack1 on mature B cells. Indeed, Rack1 augments BCR and TLR signaling in mature B cells. CD19-driven Rack1 deficiency hinders the generation of GC, PB, and PC cells. In addition, Rack1 knockdown led to impaired colony-forming ability and in vivo tumor growth of Daudi and Raji cells.

On the basis of the aberrant expression of Pax5-regulated genes, including CD19, upon Rack1 deficiency, we showed that Rack1 maintains the protein level of Pax5 without affecting its mRNA level. Most of the effects observed upon Rack1 deficiency can be attributed to reduced protein levels of Pax5. Indeed, B-cell-specific Rack1 deficiency phenocopies B-cell-specific Pax5 deficiency. Importantly, ectopic expression of Pax5 in Mb1-driven Rack1-deficient pro-B cells partially rescued defective B-cell development, confirming that a reduced protein level of Pax5 is a key factor in B-cell developmental arrest in the absence of Rack1. Notably, the reversal effects were weak, even though retroviral transduction-mediated Pax5 ectopic expression led to a Pax5 protein level comparable to that in Pro-B cells from Rack1f/f mice. Pro-B cells from Pax5 knockout mice survive well on stromal ST2 cells in the presence of IL-7 [32]. However, Pax5-deficient pro-B cells might undergo apoptosis in vitro without the support of stromal cells. In our culture system, only IL-7 was used. It is highly possible that Rack1-deficient pro-B cells initiate apoptosis before transduction, which dampens the effects of Pax5 ectopic expression.

On the other hand, Rack1 regulates multiple signaling pathways and might thereby promote the survival and differentiation of pro-B cells by binding partner(s) other than Pax5. Furthermore, Rack1 might regulate mature B cells via Pax5-independent mechanisms. For example, autophagy is dispensable for pro- to pre-B-cell transition but necessary at a basal level to maintain normal numbers of peripheral B cells, especially peritoneal B1a cells [33, 34]. Our previous studies revealed that Rack1 promotes autophagy in various types of cells [35, 36]. Thus, the strong reduction in peripheral B cells and the more pronounced reduction in peritoneal B1a cells in Rack1f/f;CD19-Cre mice might be partially due to defective autophagy. In addition, MZ B cells stringently depend on Pax5 function [9]. However, the frequency of MZ B cells among total splenic B cells was not altered in Rack1f/f;CD19-Cre mice compared with Rack1f/f mice. Other mechanisms regulated by Rack1 may compensate for the deficiency of Pax5 in MZ B cells. Another possibility is that Rack1 deletion in MZ B cells is not efficient, as shown by our recombination analysis data. Future studies are needed to address these issues.

Regarding the molecular mechanism by which Rack1 maintains the protein level of Pax5, further exploration revealed that Rack1 directly interacts with Pax5. Pax5 undergoes ubiquitination, which is blocked upon Rack1 overexpression and enhanced upon Rack1 deficiency. Moreover, Mdm2 has been identified as an E3 ligase for Pax5. Accordingly, the interaction between Mdm2 and Pax5 is blocked upon Rack1 overexpression and enhanced upon Rack1 deficiency. After mapping the Rack1/Pax5 interaction regions, we have shown that HD is the major domain by which Pax5 anchors Rack1. Because Pax5 ΔHD underwent more significant ubiquitination than Pax5 WT, the ubiquitination site is apparently not in the HD domain. Various residues within ubiquitin can be utilized to form polyubiquitin chains. Among them, K48-linked chains target proteins for degradation by the proteasome [37]. It is highly possible that Pax5 primarily undergoes K48-linked ubiquitination. Importantly, the ubiquitination of Pax5 ΔHD was not suppressed upon Rack1 overexpression. Thus, Rack1 regulates B-cell development and function through, at least partially, binding to and stabilizing the transcription factor Pax5.

Methods

Mice

Mice homozygous for a Rack1 conditional allele (Rack1f/f) on the C57BL/6 background [35, 36] were crossed with mice expressing a transgene encoding Cre recombinase driven by the CD19 (CD19-Cre mice, a gift from Dr. Susan K. Pierce, National Institutes of Health) or Mb1 (Mb1-Cre mice, Cat. No. C001056, Cyagen Biosciences Inc.) promoter and enhancer elements to generate mouse models with B-cell-specific deficiency of Rack1 (Rack1f/f; CD19-Cre and Rack1f/f; Mb1-Cre). The genotypes were determined via PCR of tissue-extracted DNA. Eight-∼12-week-old B6.SJL-CD45.1 mice and male nonobese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficient (NOD/SCID) mice were purchased from Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal, Inc. All the mice were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions. Animal care and experiments were performed in strict accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Institutes of Health publication 86-23, revised 1985) and were approved by the ethics committee of the Beijing Institute of Basic Medical Sciences (27 Taiping Road, Beijing 100850, China).

Generation of BM chimeras

To generate BM chimeras, Rack1f/f (CD45.2) mice were crossed with B6-CD45.1 mice to generate Rack1f/f (CD45.1CD45.2) mice. 3 × 106 BM cells from 8∼12-week-old Rack1f/f (CD45.1 CD45.2) and 1 × 106 BM cells from 8∼12-week-old Rack1f/f; CD19-Cre (CD45.2) mice were cotransferred into sublethally irradiated 8∼12-week-old recipients (9 Gy, CD45.1). The congenic markers CD45.1 and CD45.2 were used to distinguish cells from different donors and recipients.

Flow cytometry analysis

Single-cell suspensions were washed once with FACS washing buffer (2% FBS and 0.1% NaN3 in PBS). The cells were then incubated with fluorescence-conjugated antibodies against cell surface molecules for 30 min on ice. Antibodies against mouse B220/CD45R (clone No. RA3-6B2), CD19 (clone No. 6D5), CD43 (clone No. S11), IgM (clone No. RMM-1), IgD (clone No. 11-26 c.2a), CD21 (clone No. 7E9), CD23 (clone No. B3B4), CD5 (clone No. 53-7.3), CD138 (clone No. 281-2), GL-7 (clone No. GL-7), FAS (clone No. SA367H8), CD25 (clone No. 3c7), CD69 (clone No. H1.2F3), Ia (clone No. M5), and CD86 (clone No. GL-1) were purchased from BioLegend. After being washed with FACS buffer, the cells were fixed with 1% (w/v) paraformaldehyde in PBS and preserved at 4 °C. For the intracellular staining of Pax5, the cells were fixed/permeabilized with a Foxp3/Transcription Factor Staining Buffer Set (Cat. No. 00-5523-00, eBioscience) and stained for 30 min at 4 °C with a PE-conjugated anti-Pax5 (Cat. No. 649708, BioLegend) antibody. After being washed with permeabilization buffer, the cells were resuspended in FACS buffer and preserved at 4 °C. Flow cytometry was performed via a Becton Dickinson FACS Fortessa instrument, and the data were analyzed via FlowJo version 10. In combination with cell counting with Trypan blue staining, the number of B-cell subsets was calculated.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS)

Immediately before sorting, the cells were incubated with 0.2 μg/mL DAPI for discrimination of dead cells. Live singlets were then sorted via a Becton Dickinson FACS Aria III machine into 1 mL of RPMI-1640 containing 20% BSA.

PCR analysis of recombination efficiency

Splenic CD19+B220+CD21intCD23hi FO B and CD19+B220+CD21hiCD23low/− MZ B cells from 8∼12-week-old Rack1f/f and Rack1f/f; CD19-Cre mice were sorted, followed by genomic DNA isolation with a Mouse Direct PCR Kit (for genotyping, Cat. No. B40015, Selleck) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. PCR was performed with 2 × Taq Plus Master Mix II (Dye Plus, Cat. No. P213, Vazyme) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The PCR cycle conditions were adjusted to be within the linear amplification range. The forward primer 5′-GCCTCGACTGTGCCTTCTAG-3′ and the reverse primer 5′-TCACTAGGATCCTCTATTACATCTGCC-3′ were used. After 2% agarose gel electrophoresis, the PCR products were visualized on a UV transilluminator. The recombination efficiency was calculated via densitometric readings: (Rack1-deleted × 100%)/(Rack1-deleted + Rack1-floxed).

Total B-cell purification and in vitro stimulation

Splenic total B cells were isolated via negative selection via an EasySep Mouse B-Cell Isolation Kit (Cat. No. 19854, STEMCELL TECHNOLOGIES) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The resulting CD19+ splenic B-cell preparations were >95% pure, as determined by flow cytometry. Purified B cells were labeled with 1 μM carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE, Cat. No. 65-0850-84, eBioscience) at 37 °C for 20 min. After thorough washing, CD19+ splenic total B cells were cultured at 37 °C and 5% CO2 in RPMI-1640 medium containing 10% FBS, 10 μg/mL gentamycin, 10 mM HEPES (Cat. No. H4034, Sigma‒Aldrich), and 0.05 mM β-mercaptoethanol (Cat. No. 21985-023, Gibco) at a concentration of 5 × 106 cells/mL. B cells were stimulated with 5 μg/mL goat anti-mouse IgM F(ab’)2 fragment (Cat. No. 16-5092-85, eBioscience) with or without purified anti-mouse CD40 (clone HM40-3, Cat. No. 102902, eBioscience) or 5 μg/mL LPS (Cat. No. L7011, Sigma‒Aldrich) alone.

Apoptosis analysis

B cells were washed and resuspended in Annexin-V binding buffer (Cat. No. 00--0055--56) purchased from eBioscience, followed by staining with FITC-labeled Annexin-V (Cat. No. 640906) purchased from BioLegend for 20 min. Immediately before flow cytometry, 7-AAD viability staining solution (Cat. No. 420403) from BioLegend was added.

Bulk RNA sequencing

Splenic CD19+B220+CD21intCD23hi FO B and CD19+B220+CD21hiCD23low/− MZ B cells (7∼20 × 104/sample) from 8∼12-week-old Rack1f/f and Rack1f/f; CD19-Cre mice were sorted. Total RNA was extracted with TRIzol (Cat. No. 15596026; Thermo Fisher Scientific). The RNA amount and purity of each sample were quantified via a spectrophotometer (Cat. No. ND-1000, NanoDrop). The RNA integrity was assessed with a Bioanalyzer 2100 (Cat. No. G2939BA, Agilent) with a RIN > 7.0 and confirmed by electrophoresis with denaturing agarose gel. Total RNA (10 ng/sample) was used to prepare the low-input library via the SMART-Seq v4 Ultra Low Input RNA Kit (Cat. No. 634890, Clontech) following the manufacturer’s instructions. After library quality control was performed via a Bioanalyzer 2100, 2 × 150 bp paired-end sequencing was performed on an Illumina NovaSeq™ 6000 following the vendor’s recommended protocol. The bulk RNA-sequencing dataset has been deposited at GEO and is publicly available as of the date of publication. The accession number is GSE273420, with the reviewer token cfqryuqwpzsrzwp.

Analysis of bulk RNA-sequencing data

Reads obtained from the sequencing machines were filtered by Cutadapt (v1.9) [38] to remove reads containing adaptors, polyA and polyG, more than 5% unknown nucleotides, or more than 20% low-quality bases. The sequence quality was subsequently verified via FastQC (v0.11.9) [39]. After that, a total of more than 5.61 G bp/sample of cleaned, paired-end reads were produced. We aligned the reads of all the samples to the GRCm38 mouse reference genome via the HISAT2 package (v2.2.1) [40]. The mapped reads of each sample were assembled via StringTie with default parameters (v2.1.6) [41]. All the transcriptomes from all the samples were subsequently merged to reconstruct a comprehensive transcriptome via gffcompare software (v0.9.8) [41]. After the final transcriptome was generated, StringTie and Ballgown [41] were used to estimate the expression levels of all transcripts and determine the expression abundance of mRNAs by calculating FPKM values. Gene differential expression analysis was performed via DESeq2 software (v1.38.3) [42] between Rack1-sufficient and Rack1-deficient splenic FO B cells. Genes whose false discovery rate (Q) was less than 0.05 and absolute fold change ≥2 were considered differentially expressed genes. KEGG enrichment analysis was performed to identify signaling pathways enriched in DEGs via the R package clusterProfiler [43]. KEGG pathways with a P value < 0.05 and a Q value < 0.20 were considered statistically significant. In addition, the R package pheatmap was used to show the normalized expression of Pax5-regulated genes in mature B cells reported in at least two previous studies, and hierarchical cluster analysis was subsequently performed.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Forty-seven clinical B-cell lymphoma tissue samples, ten adjacent normal lymph node tissue samples, and ten spleen tissue samples on tissue microarray slides (Cat. No. LM801b; for detailed clinicopathological features, see Table S2) were obtained from US Biomax, Inc. Patient consent and approval from the local ethics committee were obtained for the use of the clinical materials used in this research. IHC was performed via standard protocols with citrate buffer (pH 6.0) pretreatment. Briefly, formaldehyde-fixed and paraffin-embedded sections were incubated with an antibody against Rack1 (Cat. No. 610178, BD Bioscience) or Pax5 (Cat. No. 12709, Cell Signaling Technology) at 4 °C overnight and then with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody at 37 °C for 30 min. The sections were finally incubated with diaminobenzidine and counterstained with hematoxylin for detection. The array images were captured with a panoramic scanner pannoramic (3DHISTECH) via CaseViewer 2.4 software (3DHISTECH). The H score was analyzed with Aipathwell software (Servicebio). H score = (percentage of weak intensity × 1) + (percentage of moderate intensity × 2) + (percentage of strong intensity × 3).

Immunoblotting (IB) and coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP)

MG132 (Cat. No. S2619, Selleck) was dissolved in DMSO. Whenever MG132 was used, an equal volume of DMSO was included as the control. Immunoblotting was carried out in RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5; 1% NP40; 0.35% DOC; 150 mM NaCl; 1 mM EDTA; and 1 mM EGTA supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails). After SDS‒PAGE, the proteins were transferred to Hybond-P polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. The membranes were initially incubated with primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight and then with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 h at 25 °C. The bound antibody was detected via SuperSignalTM West Pico PLUS Chemiluminescent Substrate. Co-IP was carried out in IP lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5; 2 mM EDTA; 1% NP40; 150 mM NaCl; supplemented with protease and phosphate inhibitor cocktail). A total of 1.0 mg of protein from each cell lysate/sample was then used for IP. The immunoprecipitated proteins were washed with IP lysis buffer containing 500 mM NaCl three times, followed by IB. Antibodies against phospho-Lyn (P-Lyn, Tyr507, Cat. No. 2731), phospho-extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (P-ERK, Thr202/Tyr204, Cat. No. 4370), phospho-Akt (P-Akt, Ser473, Cat. No. 4060), CD19 (Cat. No. 90176), and histone H3 (Cat. No. 4499) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. Antibodies against Rack1 (Cat. No. sc-10775) and protein A/G-plus agarose were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Antibodies against the Flag tag (Cat. No. F1804) and β-tubulin (Cat. No. T8328) were acquired from Sigma‒Aldrich. Antibodies against the HA tag (Cat. No. M180-3 for IP) and GFP (Cat. No. 598) were obtained from MBL International. Antibodies against β-actin (Cat. No. 66009-1-Ig), ubiquitin (Cat. No. 10201-2-AP), Mdm2 (Cat. No. 19058-1-AP), Pax5 (Cat. No. 26709-1-AP), and the HA tag (Cat. No. 51064-2-AP, for IB) were purchased from Proteintech.

Immunization and specific antibody detection by ELISA

The mice were immunized subcutaneously with 100 μg of KLH (Cat. No. H7017, Sigma‒Aldrich) in complete Freund’s adjuvant (Cat. No. F5881, Sigma‒Aldrich) for primary immunization (day 0) and with incomplete Freund’s adjuvant (Cat. No. F5506, Sigma‒Aldrich) on days 10 and 20. The serum was collected on days 5, 15 and 25. For the measurement of anti-KLH IgM and IgG, 96-well ELISA plates were coated with KLH (20 μg/mL) in PBS overnight at 4 °C. All steps were subsequently performed at 25 °C, and the wells were subsequently washed with PBS containing 0.1% Tween-20 three times before each step until coloring. Briefly, blocking buffer (PBS containing 0.1% Tween-20 and 10% BSA) was added for 1 h, followed by the serum diluted in blocking buffer for 2 h, biotin-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgM or IgG (Cat. No. ZB2055 and ZB2020, ZSGB-BIO) diluted in blocking buffer for 1 h, avidin-HRP (Cat. No. 00--4100--94, eBioscience) diluted in blocking buffer for 30 min in the dark, and tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) working buffer for ≤15 min. Coloring was stopped by the addition of 1 N H2SO4. The absorbance was measured at 450 nm (OD450) via an enzyme-labeled instrument (Cat. No. MULTISKAN MK3, Thermo Scientific).

Quantitative RT‒PCR

Total RNA was extracted with TRIzol and reverse transcribed with ABScript III RT Master Mix (Cat. No. RK20428, ABclonal). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed with Fast Start Essential DNA Green Master Mix (Cat. No. 48252200, Roche Diagnostics) in a LightCycler® 480 System (Roche Diagnostic). The Ct value was used to assess gene expression via the 2−ΔΔCt method. Fold amplification was normalized to the gene encoding β-actin. The primer sequences are listed in Table S3.

Culture, transfection, and transduction of cell lines

The cell lines were purchased from the Shanghai Institute for Biological Sciences and were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin and were maintained at 37 °C with 5% CO2. The mammalian expression vector encoding Flag-tagged Pax5 was obtained from the Public Protein/Plasmid Library (Cat. No. PPL02787). Other mammalian or prokaryotic expression vectors used in this study have been described [44, 45]. Truncated mutants of Pax5 were generated through overlap PCR and confirmed by DNA sequencing. Plasmid transfection was performed with jetPRIME (Cat. No. 101000046, Polyplus) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Lentivirus-based human Rack1 shRNAs (GATGTGGTTATCTCCTCAGAT and CAAGCTGAAGACCAACCACAT), human Pax5 shRNAs (GCACCCATGTAAATACCTTCT and GCTCATCCCTCCTTCTTTAGT), and nontargeting control shRNAs were obtained from Shanghai GeneChem. Lentiviral transduction (multiplicity of infection = 100) was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

In vivo xenograft experiment

Lentivirus-transduced Daudi and Raji cells were sorted on the basis of GFP expression. Because Rack1 (or Pax5) knockdown led to retarded cell proliferation, Daudi and Raji cells expressing different shRNAs against Rack1 (or Pax5) were combined to obtain enough cells for in vivo experiments. Male NOD/SCID mice were subcutaneously inoculated with sorted Daudi or Raji cells (1 × 106/0.2 mL of phosphate-buffered saline). The mice were sacrificed for evaluation of tumor volume and tumor weight 2 (Pax5 shRNA in Daudi), 3 (Pax5 shRNA in Raji), or 5 (Rack1 shRNA) weeks later.

Soft agar assay

The soft agar cloning assay was performed as described previously [46]. The cells were seeded into 6-well plates at a density of 5 × 103 per well. On day 28, MTT incorporation was included to make the colonies visible.

Glutathione S-transferase (GST) pull-down assays

GST and GST-Rack1 were expressed and purified with glutathione-Sepharose (GSH) beads according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Lysates of HEK-293T cells expressing Flag-Pax5 were incubated with GST or GST-Rack1 bound to GSH beads, and the adsorbed proteins were analyzed via IB.

Computer-guided homology modeling and molecular docking

On the basis of the alphafold structure prediction method, the 3-D theoretical structure of mouse Pax5 (UniProt code: Q02650) was constructed. Using the crystal structure of mouse Rack1 (PDB code: 7cpv) as a model, the 3-D theoretical structure was obtained via computer-guided homology modeling. Using the CVFF forcefield, the 3-D structures of mouse Pax5 and Rack1 were optimized via the steepest descent method, and the convergence criterion was set to 0.5 kcal/mol and 8000 iteration steps. The 3-D complex structure of the Pax5 and Rack1 interaction was then modeled via the molecular docking method. The homology modeling, molecular mechanism optimization, and docking methods were performed with Insight II 2000 software and an IBM workstation.

In vivo ubiquitination assay with IP

The cells were solubilized in modified lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1% SDS, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM DTT, and 10 mM NaF) supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail. The cell lysates were incubated at 60 °C for 10 min, followed by 10-fold dilution with modified lysis buffer without SDS. After sonication, the samples were incubated at 4 °C for 1 h with rotation, followed by centrifugation at 13,600 × g for 30 min at 4 °C. A total of 1.0 mg of protein from whole-cell lysates/sample was then used for IP. Immunoprecipitated proteins were washed with modified lysis buffer containing 0.1% SDS three times, followed by IB.

Retroviral transduction

The PCR-amplified coding sequence of Pax5 was cloned and inserted into the MSCV-IRES-GFP retroviral vector (Cat. No. 20672, Addgene) and confirmed by DNA sequencing. MSCV-IRES-GFP and MSCV-Pax5-IRES-GFP were separately transfected into HEK-293T cells along with the pCL-Eco packaging vector, which was a gift from Dr. Lin Sun (Renji Hospital, Shanghai, China). Cell-free supernatants containing viral particles were harvested after 48 h of culture. In vitro retroviral transduction of pro-B cells and subsequent B-cell differentiation were carried out as previously described [47, 48]. Briefly, sorted BM CD19−B220+CD43hi pro-B cells were stimulated for 24 h with 50 ng/mL IL-7 (Cat. No. 577806, BioLegend) and then infected with 2 μL of retroviral supernatant containing 8 μg/mL polybrene. The infection mixture was centrifuged for 1.5 h at 1800 rpm at 32 °C, followed by incubation at 37 °C for 24 h. Then, the GFP+ cells were sorted and cultured in the presence of 50 ng/mL IL-7 for 7 d prior to flow cytometry analysis of B-cell differentiation.

Statistics

The error bars represent the means ± standard deviations (SDs). Statistical calculations were performed via GraphPad Prism 8.3.0. The statistical details of the individual experiments are provided in the relevant figure legends. For all analyses, P values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Susan K. Pierce for providing the CD19-Cre mice, Dr. Lin Sun for providing the pCL-Eco packaging vector, and Mr. Libing Yin for FACS sorting.

Author contributions

JZ conceived the original ideas, designed the project, and wrote the manuscript with inputs from QC and TS. XZ, CM, JW, HY, HJ, MW, XF, GW, and GX performed the experiments. HD and WL provided key reagents. JF performed computer-guided homology modeling and molecular docking. TS, QC, and JZ supervised the investigation. XZ, CM, YL, QC, and JZ analyzed the data.

Funding

This study is supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81930027, 92169207, and 82172298).

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests. JZ is an editorial board member of Cellular & Molecular Immunology, but she has not been involved in peer review or decision-making related to the article.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Beijing Institute of Basic Medical Sciences. The use of the clinical materials was undertaken with the understanding and signed informed consent of each donor.

Footnotes

These authors contributed equally: Xueting Zhang, Chenke Ma.

Contributor Information

Taoxing Shi, Email: shitaoxing@sina.com.

Qianqian Cheng, Email: chengqianqian044271@126.com.

Jiyan Zhang, Email: zhangjy@bmi.ac.cn.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41423-024-01213-2.

References

- 1.Ripperger TJ, Bhattacharya D. Transcriptional and metabolic control of memory B cells and plasma cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2021;39:345–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bassing CH, Swat W, Alt FW. The mechanism and regulation of chromosomal V(D)J recombination. Cell. 2002;109:S45–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berland R, Wortis HH. Origins and functions of B-1 cells with notes on the role of CD5. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:253–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cerutti A, Cols M, Puga I. Marginal zone B cells: virtues of innate-like antibody-producing lymphocytes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:118–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Victora GD, Nussenzweig MC. Germinal centers. Annu Rev Immunol. 2012;30:429–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nutt SL, Hodgkin PD, Tarlinton DM, Corcoran LM. The generation of antibody-secreting plasma cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15:160–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nutt SL, Heavy B, Rolink AG, Busslinger M. Commitment to the B-lymphoid lineage depends on the transcription factor Pax5. Nature. 1999;401:556–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horcher M, Souabni A, Busslinger M. Pax5/BSAP maintains the identity of B cells in late B lymphopoiesis. Immunity. 2001;14:779–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Calderón L, Schindler K, Malin SG, Schebesta A, Sun Q, Schwickert T, et al. Pax5 regulates B-cell immunity by promoting PI3K signaling via PTEN downregulation. Sci Immunol. 2021;6:eabg5003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaiser FMP, Gruenbacher S, Oyaga MR, Nio E, Jaritz M, Sun Q, et al. Biallelic PAX5 mutations cause hypogammaglobulinemia, sensorimotor deficits, and autism spectrum disorder. J Exp Med. 2022;219:e20220498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fuxa M, Busslinger M. Reporter gene insertions reveal a strictly B lymphoid-specific expression pattern of Pax5 in support of its B-cell identity function. J Immunol. 2007;178:3031–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Delogu A, Schebesta A, Sun Q, Aschenbrenner K, Perlot T, Busslinger M. Gene repression by Pax5 in B cells is essential for blood cell homeostasis and is reversed in plasma cells. Immunity. 2006;24:269–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Revilla-i-Domingo R, Bilic I, Vilagos B, Tahoh H, Ebert A, Tamir IM, et al. The B-cell identity factor Pax5 regulates distinct transcriptional programs in early and late B lymphopoiesis. EMBO J. 2012;31:3130–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schebesta A, McManus S, Salvagiotto G, Delogu A, Busslinger GA, Busslinger M. Transcription factor Pax5 activates the chromatin of key genes involved in B-cell signaling, adhesion, migration, and immune function. Immunity. 2007;27:49–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nutt SL, Morrison AM, Dörfler P, Rolink A, Busslinger M. Identification of BSAP (Pax-5) target genes in early B-cell development by loss- and gain-of-function experiments. EMBO J. 1998;17:2319–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pasqualucci L, Neumeister P, Goossens T, Nanjangud G, Chaganti RS, Küppers R, Dalla-Favera R. Hypermutation of multiple proto-oncogenes in B-cell diffuse large-cell lymphomas. Nature. 2001;412:341–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Busslinger M, Klix N, Pfeffer P, Graninger PG, Kozmik Z. Deregulation of PAX-5 by translocation of the Eµ enhancer of the IgH locus adjacent to two alternative PAX-5 promoters in a diffuse large-cell lymphoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:6129–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lida S, Rao PH, Nallasivam P, Hibshoosh H, Butler M, Louie DC, et al. The t(9;14)(p13;q32) chromosomal translocation associated with lymphoplasmacytoid lymphoma involves the PAX-5 gene. Blood. 1996;88:4110–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morrison AM, Jäger U, Chott A, Schebesta M, Haas OA, Busslinger M. Deregulated PAX-5 transcription from a translocated IgH promoter in marginal zone lymphoma. Blood. 1998;92:3865–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cozma D, Yu D, Hodawadekar S, Azvolinsky A, Grande S, Tobias JW, et al. B-cell activator PAX5 promotes lymphomagenesis through stimulation of B-cell receptor signaling. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2602–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Usacheva A, Smith R, Minshall R, Baida G, Seng S, Croze E, et al. The WD motif-containing protein receptor for activated protein kinase C (RACK1) is required for recruitment and activation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 through the type I interferon receptor. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:22948–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang W, Zong CS, Hermanto U, Lopez-Bergami P, Ronai Z, Wang LH. RACK1 recruits STAT3 specifically to insulin and insulin-like growth factor 1 receptors for activation, which is important for regulating anchorage-independent growth. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:413–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Okano K, Schnaper HW, Bomsztyk K, Hayashida T. RACK1 binds to Smad3 to modulate transforming growth factor-β-stimulated α2(I) collagen transcription in renal tubular epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:26196–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhu Q, Chen L, Li Y, Huang M, Shao J, Li S, et al. Rack1 is essential for corticogenesis by preventing p21-dependent senescence in neural stem cells. Cell Rep. 2021;36:109639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu YV, Baek JH, Zhang H, Diez R, Cole RN, Semenza GL. RACK1 competes with HSP90 for binding to HIF-1α and is required for O2-independent and HSP90 inhibitor-induced degradation of HIF-1α. Mol Cell. 2007;25:207–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang J, Chen X, Hu H, Yao M, Song Y, Yang A, et al. PCAT-1 facilitates breast cancer progression by binding to RACK1 and enhancing oxygen-independent stability of HIF-1α. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2021;24:310–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cao J, Zhao M, Liu J, Zhang X, Pei Y, Wang J, et al. RACK1 promotes self-renewal and chemoresistance of cancer stem cells in human hepatocellular carcinoma through stabilizing Nanog. Theranostics. 2019;9:811–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oien DB, Sharma S, Hattersley MM, DuPont M, Criscione SW, Prickett L, et al. BET inhibition targets ABC-DLBCL constitutive B-cell receptor signaling through PAX5. Blood Adv. 2023;7:5108–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schmidt-Supprian M, Rajewsky K. Vagaries of conditional gene targeting. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:665–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thévenin C, Nutt SL, Busslinger M. Early function of Pax5 (BSAP) before the pre-B-cell receptor stage of B lymphopoiesis. J Exp Med. 1998;188:735–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hobeika E, Thiemann S, Storch B, Jumaa H, Nielsen PJ, Pelanda R, et al. Testing gene function early in the B-cell lineage in mb1-cre mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:13789–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nutt SL, Urbánek P, Rolink A, Busslinger M. Essential functions of Pax5 (BSAP) in pro-B-cell development: difference between fetal and adult B lymphopoiesis and reduced V-to-DJ recombination at the IgH locus. Genes Dev. 1997;11:476–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arnold J, Murera D, Arbogast F, Fauny JD, Muller S, Gros F. Autophagy is dispensable for B-cell development but essential for humoral autoimmune responses. Cell Death Differ. 2016;23:853–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Clarke AJ, Riffelmacher T, Braas D, Cornall RJ, Simon AK. B1a B cells require autophagy for metabolic homeostasis and self-renewal. J Exp Med. 2018;215:399–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhao Y, Wang Q, Qiu Q, Zhou S, Jing Z, Wang J, et al. RACK1 promotes autophagy by enhancing the Atg14L -Beclin 1-Vps34-Vps15 complex formation upon phosphorylation by AMPK. Cell Rep. 2015;13:1407–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qiu G, Liu J, Cheng Q, Wang Q, Jing Z, Pei Y, et al. Impaired autophagy and defective T-cell homeostasis in mice with T-cell-specific deletion of receptor for activated C kinase 1. Front Immunol. 2017;8:575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rahman S, Wolberger C. Breaking the K48-chain: linking ubiquitin beyond protein degradation. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2024;31:216–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martin M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet J. 2011;17:10–12. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thompson O, von Meyenn F, Hewitt Z, Alexander J, Wood A, Weightman R, et al. Low rates of mutation in clinical grade human pluripotent stem cells under different culture conditions. Nat Commun. 2020;11:1528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim D, Paggi JM, Park C, Bennett C, Salzberg SL. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat Biotechnol. 2019;37:907–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pertea M, Kim D, Pertea GM, Leek JT, Salzberg SL. Transcript-level expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with HISAT, StringTie and Ballgown. Nat Protoc. 2016;11:1650–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15:550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu T, Hu E, Xu S, Chen M, Guo P, Dai Z, et al. clusterProfiler 4.0: a universal enrichment tool for interpreting omics data. Innovation. 2021;2:100141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guo Y, Wang W, Wang J, Feng J, Wang Q, Jin J, et al. Zhang, Receptor for activated C kinase 1 promotes hepatocellular carcinoma growth by enhancing mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 7 activity. Hepatology. 2013;57:140–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu G, Wang Q, Deng L, Huang X, Yang G, Cheng Q, et al. Hepatic RACK1 deficiency protects against fulminant hepatitis through myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Theranostics. 2022;12:2248–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cui J, Wang Q, Wang J, Lv M, Zhu N, Li Y, et al. Basal c-Jun NH2-terminal protein kinase activity is essential for survival and proliferation of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8:3214–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ubieta K, Garcia M, Grötsch B, Uebe S, Weber GF, Stein M, et al. Fra-2 regulates B-cell development by enhancing IRF4 and Foxo1 transcription. J Exp Med. 2017;214:2059–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Seo W, Ikawa T, Kawamoto H, Taniuchi I. Runx1-Cbfβ facilitates early B lymphocyte development by regulating expression of Ebf1. J Exp Med. 2012;209:1255–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.