Abstract

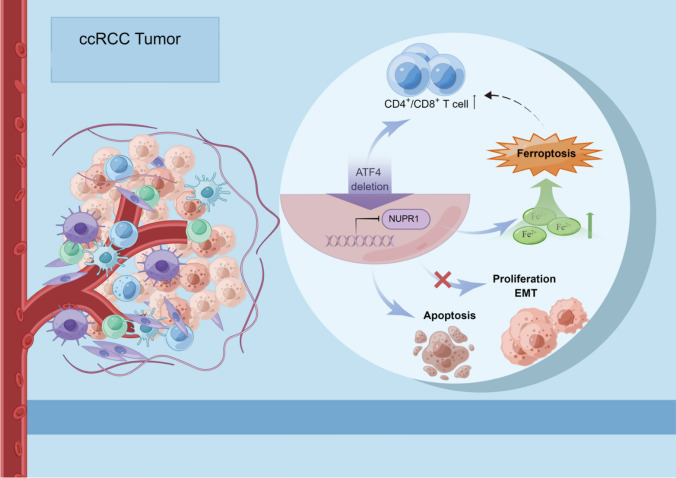

Cancer cells encounter unavoidable stress during tumor growth. The stress-induced transcription factor, activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4), has been reported to upregulate various adaptive genes involved in salvage pathways to alleviate stress and promote tumor progression. However, this effect is unknown in clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC). In this study, we found that ATF4 expression was remarkably upregulated in tumor tissues and associated with poor ccRCC outcomes. ATF4 depletion significantly impaired ccRCC cell proliferation, migration, and invasion in vitro and in vivo by inhibiting the AKT/mTOR and epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT)-related signaling pathway. RNA sequencing and functional studies identified nuclear protein 1 (NUPR1) as a key downstream target of ATF4 for repressing ferroptosis and promoting ccRCC cell survival. In addition, targeting ATF4 or pharmacological inhibition using NUPR1 inhibitor ZZW115 promoted antitumor immunity in syngeneic graft mouse models, represented by increased infiltration of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Furthermore, ZZW115 could improve the response to the PD-1 immune checkpoint blockade. The results demonstrate that the ATF4/NUPR1 signaling axis promotes ccRCC survival and facilitates tumor-mediated immunosuppression, providing a set of potential targets and prognostic indicators for ccRCC patients.

Graphical abstract

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12672-024-01485-0.

Keywords: ccRCC, ATF4, NUPR1, Ferroptosis, Immunosuppression

Introduction

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is the sixth leading cause of cancer-related deaths globally, with a slight increase in associated morbidity and mortality in recent years [1, 2]. Approximately 30% of RCC patients are initially diagnosed with advanced or metastatic disease due to occult early symptoms and a lack of markers [3], and approximately 75–80% of the pathological RCC types are clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) [4]. The loss or mutation of the von Hippel Lindau (VHL) gene is generally considered to be one of the obligate initiating steps in the development of ccRCC [5]. The best understood function of VHL is the ubiquitination of the prolyl hydroxylated transcription factors hypoxia inducible factors 1 and 2 alpha (HIF1α and HIF2α), with their subsequent proteolytic degradation. HIF1α and 2α regulate transcription of a number of genes involved in angiogenesis, metabolism and chromatin remodeling. More studies have shown that vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and platelet derived growth factor (PDGF) mRNA are increased in ccRCC and HIF mediated transcription of proangiogenic factors including VEGF was shown to facilitate the development of neovasculature [6–11]. It has been shown that the VHL regulates some other pathways and processes including AKT, nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NK-kB) tank-binding kinase-1 (TBK1), the primary cilium and mitosis. ccRCC is characterized by near-universal loss of most or all of chromosome 3p [12–14]. Several other genes including Polybromo 1 (PBRM1), SET domain containing 2 (SETD2) and BRCA associated protein 1 (BAP1), all found on chromosome 3p, are mutated at a relatively high frequency in ccRCC [15–17], and are likely associated with both convergent and divergent phenotypic characteristics in ccRCC.

Although surgery is potentially curative for ccRCC when detected at an early stage, postoperative recurrence remains common, and tyrosine kinase inhibitors and immunotherapy for advanced ccRCC remain unsatisfactory owing to drug resistance [18]. Consequently, it is crucial to acquire in-depth insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying ccRCC occurrence and development to identify new targets and develop therapies for its treatment.

Rapidly growing tumors with excessive proliferation escalate the demand for protein synthesis, which contributes to endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress [19–21], and cells in the tumor core suffer from a lack of oxygen and nutrients due to insufficient and defective vascularization. Consequently, sets of adaptive genes are activated in response to these challenges [22], and there is a common downstream effector protein, ATF4, that is frequently upregulated in cancer cells. It controls the expression of target genes, most of which are involved in various salvage pathways that relieve stress and promote cell survival [23]. Recent studies have revealed that ATF4 is required for distinct steps to increase amino acid availability in the autophagic pathway, and it may enhance mTOR activity by upregulating adaptive genes [24, 25]. It is thus evident that ATF4 plays a pivotal role in alleviating stress during rapid tumor growth. Our study shows that ATF4 may influence the tumor progression via the transcriptional regulation of NUPR1 in ccRCC. NUPR1 is also known as p8 and is a candidate of metastasis 1 (COM1) and is overexpressed in various cancers in response to several cellular stress factors. Remarkably, multiple types of cancer can be prevented by genetically inactivating NUPR1 [26–34]. Mechanistically, NUPR1 may promote tumor progression by activating the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, and it is also a critical repressor of ferroptosis that blocks ferroptotic cell death by diminishing iron accumulation and subsequent oxidative damage via LCN2 expression [35–37]. Ferroptosis is a form of regulated cell death characterized by iron-dependent lipid peroxidation [38]. Various metabolic processes, such as those associated with iron and amino acids, have been suggested to be related to ferroptosis [39]. Dysfunction of ferroptosis is closely related to tumor progression [40]. Moreover, a recent study demonstrated that ferroptosis is related to the tumor microenvironment (TME) features and may play a key role in the response to immunotherapy [41]. ATF4 is reported to be an adaptive regulator of cancer cell responses to various stresses, including ER stress during ferroptosis by erastin [42, 43]. However, the functions and regulatory mechanisms of ATF4 remain largely unknown in ccRCC, and studies concerning ferroptosis in ccRCC are insufficient. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the role of ATF4 in ccRCC, especially the function in ferroptosis and tumor immunology.

Materials and methods

Cell culture, reagents, and transduction

The human embryonic kidney cell line HEK293T, the human kidney proximal tubular epithelial cell line HKC, ccRCC cell lines A498 (vhl mutated), ACHN (vhl wild-type), Caki-1(vhl wild-type), 786-O (vhl mutated), SN12 (vhl wild-type), and murine RCC cell line (RenCa) were purchased in September 2015 from the National Platform of Experimental Cell Resources for Sci-Tech (Beijing, China) and authenticated in January 2019 using a previously described method [44]. All cell lines were cultured in the recommended medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Evergreen Co. Ltd., China) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin at 37 °C in 5% CO2 under mycoplasma-free conditions. pLKO-shATF4 plasmids with short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) targeting human and murine ATF4 were designed by Invitrogen. The target shATF4 sequences in humans and mice are enumerated in Supplementary Table S1. Plasmid construction and transduction were performed using a method described previously [44]. Chemical reagents, including erastin (CAS No. 571203–78-6), ferrostatin-1 (CAS No. 347174–05-4), ZZW115 (CAS No. 801991–87-7), and anti-PD1 (CAS No. 946414–94-4) were purchased from MedChem Express (Shanghai, China).

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) and analysis

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Research Ethics Committee of the PLA General Hospital. A total of 199 pairs of ccRCC and normal tissue specimens were included from previously constructed tissue microarrays (TMAs) in our laboratory. Immunostaining of the TMA and xenograft tumor tissues was performed as previously described [45]. The primary antibodies included rabbit anti-ATF4 (Proteintech; 10,835–1-AP), rabbit anti-NUPR1 (Proteintech; 15,056–1-AP), rabbit anti-CD4 (Abcam; ab183685), rabbit anti-CD8 alpha (Abcam; ab217344), rabbit anti-cleaved caspase-3 (Cell Signaling Technology; #9661), mouse anti-granzyme B (Santa Cruz; sc-8022), and rabbit anti-Ki-67 (Cell Signaling Technology; #9129). TMA samples were classified according to the intensity of ATF4 or NUPR1 staining, and their expressions were scored as follows: 0, negative; 1, very weak; 2, moderate; and 3, strong. Cases with scores of 0/1 and 2/3 were defined as the ATF4 or NUPR1 low- and high-expression groups, respectively. Tumor-infiltrating immune cells were evaluated as previously described [46].

Real-time PCR

In accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol, total RNA was extracted from cells using the PARISTM Kit (Applied Biosystems) and then reverse-transcribed to obtain cDNA. With the Applied Biosystems 7500 Detection system, real-time PCR was performed. Relative mRNA levels were normalized to human peptidylprolyl isomerase A (PPIA) and calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method [47]. Supplementary Tables S2 and S3 specify the primer sequences and reaction conditions of mixtures for real-time PCR.

Immunoblotting and Antibody

Western blot was performed as described previously [44]. Primary antibodies included rabbit anti-ATF4 (Proteintech; 10,835–1-AP), rabbit anti-mTOR (Cell Signaling Technology; #2983S), rabbit anti-phospho-mTOR (Ser2448) (D9C2) XP® (Cell Signaling Technology; #5536S), rabbit anti-S6K (Proteintech; 14,485–1-AP), rabbit anti-phospho-S6K (Proteintech; 28,735–1-AP), rabbit anti-4EBP1 (Cell Signaling Technology; #9644S), rabbit anti-phospho-4EBP1 (Cell Signaling Technology; #2855S), rabbit anti-N-cadherin (Proteintech; 22,018–1-AP), rabbit anti-E-cadherin ((Proteintech; 20,874–1-AP), rabbit anti-vimentin (Proteintech; 10,366–1-AP), rabbit anti-cleaved caspase-3 (Cell Signaling Technology; #9661), rabbit-anti-BCL2 (Cell Signaling Technology; #3498S), rabbit anti-AKT (Cell Signaling Technology; #4685S), rabbit anti-phospho-Akt (Ser473) (D9E) XP® (Cell Signaling Technology; #4060S), and rabbit anti-NUPR1 (Proteintech; 15,056–1-AP).

Migration and invasion assay

As described in our previous research [48]. Cells were seeded into an upper transwell chamber (8 μm, Corning), which was coated with 20 μL of Matrigel (Corning) before cell seeding for the invasion assay. After incubation, the chamber membranes were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with 1% crystal violet for 15 min, and the number of migrated or invaded cells was analyzed by calculating six random fields. All experiments were conducted at least three times.

Cell proliferation and viability assay

Cell proliferation and viability were measured by MTT assay kit (ab211091, abcam) or Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK8) (HY-K0301, MedChemExpress) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

For MTT assay, the media was discarded and aspirated from cell cultures, 50 µL of serum-free media and 50 µL of MTT solution were added into each well. After incubation at 37 °C for 3 h, another 150 µL of MTT solvent was added into each well. The plate was wrapped in foil and shaken on an orbital shaker for 15 min. Occasionally, pipetting of the liquid may be required to fully dissolve the MTT formazan. The absorbance at OD = 590 nm was read within 1 h.

For CCK8 assay, Cell suspension (100 μL/well) was seeded in the 96-well plate and cultured for 24 h. Different concentrations of the drug were added to be tested to the culture plate which was incubated for an appropriate period of time. 10 μL of CCK-8 solution was added to each well (be careful not to produce bubbles) and incubated for 1–4 h. The absorbance at 450 nm was measured. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Flow cytometry for cell apoptosis analysis and lipid reactive oxygen species (ROS) analysis

An Annexin V-FITC/PI kit (Abbkine Scientific Co., Ltd, KTA0002) was used to investigate the apoptotic effect of ATF4 knockdown and the NUPR1 inhibitor. Lipid ROS were stained with C11-BODIPY 581/591 (RM02821, ABclonal Technology Co., Ltd, Wuhan, China) and analyzed using flow cytometry and fluorescence microscopy in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocols. The mean fluorescence intensity was estimated using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ). All samples were analyzed in triplicate, and the data were analyzed using FlowJo version 10 software. Fluorescence imaging was performed using TissueFAXS (TissueGnostics GmbH, Vienna, Austria) with a Zeiss Axio Imager Z2 microscope system.

Cell immunofluorescence: Terminal-deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated nick end labeling (TUNEL) and Fe2+ level assays

Cells were placed in culture dishes overnight for adhesion, and the relevant treatment was then applied. The TUNEL Apoptosis Detection Kit (Green Fluorescence; Abbkine Scientific Co., Ltd, KTA2010) or FerroOrange (Dojindo Laboratories, Beijing, China) was used in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions to determine cellular apoptosis or Fe2+ levels. Fluorescence images were obtained using TissueFAXS (TissueGnostics GmbH, Vienna, Austria). A quantitative analysis of the mean fluorescence signal intensity was conducted using the ImageJ software. All samples were analyzed in triplicate.

Animal modeling and treatment

The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the PLA General Hospital. Tumor cells (1 × 106) with PBS or Matrigel (Corning) were implanted into the kidneys of male BALB/c (nude) mice (Vital River, Beijing, aged 4–5 weeks) for the xenograft model or syngeneic graft. After three weeks, the mice were sacrificed, and bioluminescent imaging was performed. For the anti-PD1 treatment, the mice received 200 µg of anti-PD1 via intraperitoneal injection on days 8, 11, 14, 17, and 20, and for the NUPR1 inhibitor ZZW115 treatment, mice received 1 mg/kg ZZW115 via intraperitoneal injection daily (treatment on days 8–21). The maximal tumor size/burden permitted by our institutional review board is mean tumor diameter 20 mm and 15% of body weight in adult mice (~ 25 g). The maximal tumor size/burden in our study was not exceeded.

Anesthesia and euthanasia

Before the operation, the mice received anesthesia with 2% isoflurane inhalation at 4L/min fresh gas flow. We may adjust the gas flow according to the condition of mice and keep the mice warm after operation to promote analepsia. The 1% pentobarbital was injected intraperitoneally (100 mg/kg) for mice euthanasia.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented herein as mean ± standard error of measurement (SEM) from at least three independent experiments. ANOVA, Mann–Whitney U, or Student’s t-test was used when appropriate to perform comparisons. The Kaplan–Meier method, log-rank test, and multivariate Cox proportional hazard models were used to detect survival differences and identify independent prognostic factors. Statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS 22.0 (SPSS Inc., USA). The level of significance was set at *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001.

Results

ATF4 expression is upregulated in ccRCC and associated with poor outcomes

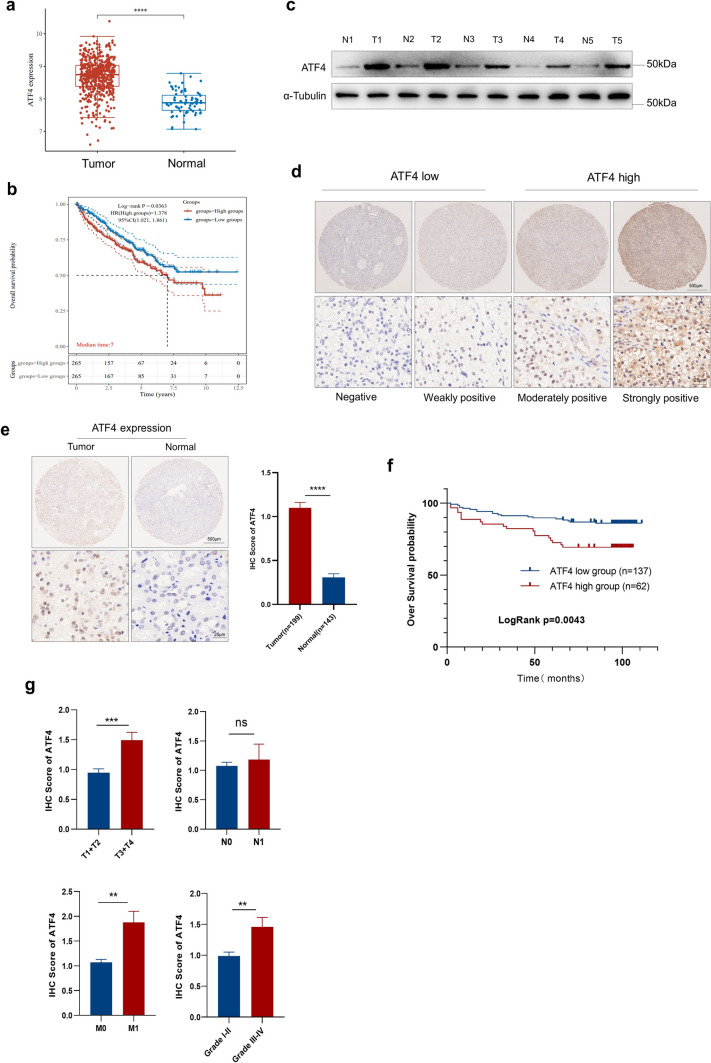

To evaluate ATF4 expression and its potential clinical role in ccRCC, we investigated the mRNA expression of ATF4 in ccRCC by analyzing the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) data, indicating that ATF4 expression was significantly higher in ccRCC tumor tissues than in normal tissues (Fig. 1a). ATF4 expression was also associated with prognosis, and the overall survival (OS) probability of the ATF4 high-expression group was found to be significantly higher than that of the ATF4 low-expression group (Fig. 1b). Western blot experiments on five paired ccRCC tissues and normal tissues from patients revealed that ATF4 was upregulated in tumor tissues (Fig. 1c).

Fig. 1.

ATF4 expression is upregulated in ccRCC and is associated with poor outcomes. a The mRNA levels of ATF4 were analyzed in the ccRCC tissues in the TCGA dataset compared with the normal controls. b Kaplan–Meier analysis of OS for all ccRCC patients with low or high ATF4 expression levels in the TCGA dataset. c Western blot experiment was performed to evaluate the protein level of ATF4 in five paired ccRCC tissue samples (“T” means tumor tissue, and “N” means paired normal tissue). d Representative images of ATF4 IHC staining with high or low expression level in ccRCC tumor tissues by TMAs. (e) IHC representative images and analysis of ATF4 expression in tumor tissues (n = 199) and normal tissues (n = 143) by TMAs. f Kaplan–Meier analysis of ccRCC over survival based on ATF4 expression level in ccRCC TMAs. The p-value was calculated using the log-rank test. g Comparison of ATF4 IHC scores among groups with different tumor TNM stages and tumor grades. The p-values were calculated using the Mann–Whitney U test. h Association of ATF4 expression with clinical and pathological characteristics of 199 ccRCC patients in TMAs. The data are presented in terms of means ± SEM. The p-values were estimated using the Mann–Whitney U test (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001)

We then evaluated ATF4 expression in ccRCC by conducting an IHC staining analysis of a TMA consisting of 199 ccRCC and 143 normal tissue samples. A variable ATF4 staining intensity was detected in ccRCC tumor tissues using TMAs (Fig. 1d), and patients were divided into low- and high-expression groups based on the IHC score according to ATF4 expression level. The IHC score for ATF4 in tumor tissues was higher than in normal tissues (Fig. 1e). The Kaplan–Meier analysis revealed that ATF4 high expression was significantly correlated with a shorter OS (p = 0.0043; Fig. 1f). Consistently, ATF4 expression also correlated with various features of tumor progression, including T stage, M stage, and histological grade. Quantitative analyses based on IHC scores indicated that high ATF4 expression was significantly associated with advanced T stage (T3 and T4), M1 stage, and advanced tumor grade (III and IV; Fig. 1g, Table 1). Taken together, these findings suggest that ATF4 expression is upregulated in ccRCC and associated with poor outcomes.

Table 1.

Association of ATF4 expression with clinical and pathological characteristics of 199 ccRCC patients in TMAs

| Characteristic | ATF4 expression | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| High(n = 62) | Low(n = 137) | ||

| Age | 53.60 ± 9.99 | 53.68 ± 9.41 | 0.955 |

| BMI | 25.66 ± 3.41 | 25.68 ± 3.16 | 0.961 |

| Sex | 0.069 | ||

| Male | 53 (85.48%) | 100 (72.99%) | |

| Female | 9 (14.52%) | 37 (27.01%) | |

| T stage | 0.0012* | ||

| T1 + T2 | 37 (59.68%) | 113 (82.48%) | |

| T3 + T4 | 25 (40.32%) | 24 (17.52%) | |

| N stage | 0.3319 | ||

| N0 | 59 (92.19%) | 131(95.62%) | |

| N1 | 5 (7.81%) | 6 (4.38%) | |

| M stage | 0.0122* | ||

| M0 | 56 (90.32%) | 135 (98.54%) | |

| M1 | 6 (9.68%) | 2 (1.46%) | |

| Fuhrman | 0.0010* | ||

| Grade I–II | 41 (66.13%) | 119 (86.86%) | |

| Grade III + IV | 21 (33.87%) | 18 (13.14%) | |

*P < 0.05 indicates a significant association among the variables

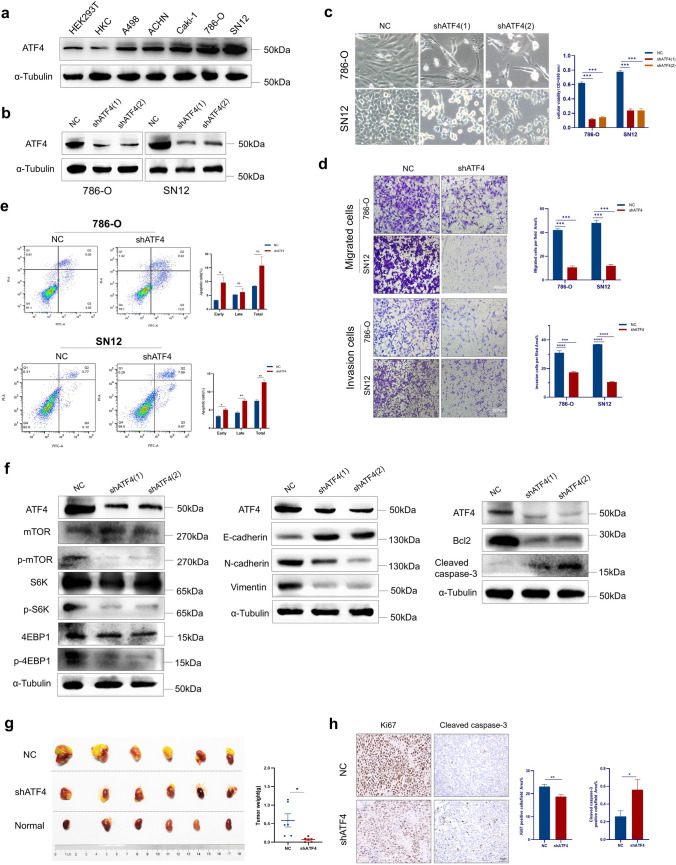

ATF4 knockdown attenuates ccRCC cell proliferation, migration, and invasion and induces apoptosis

To investigate the functional role of ATF4 in ccRCC cells, we first examined the protein expression of ATF4 in normal renal epithelial cells (HEK293T and HKC) and ccRCC cell lines (A498, ACHN, Caki-1, 786-O, and SN12). The results revealed that a higher ATF4 expression was detected in ccRCC cell lines compared with HEK293T and HKC cell lines (Fig. 2a). Among these cell lines, the top two highest expressions of ATF4 were observed in the SN12 and 786-O cell lines, which were then used for further studies in vitro.

Fig. 2.

ATF4 knockdown attenuates ccRCC cell proliferation, migration, and invasion and induces apoptosis. a Relative ATF4 protein levels in HEK293T, HKC cells, and a panel of ccRCC cell lines. b ATF4 expression levels in 786-O and SN12 cells transduced with shATF4 or NC for four days were detected via Western blot. c The indicated cells are transduced with shATF4 for four days, followed by bright-field imaging (left) and quantification (right). Optical density (OD) values at 590 nm were used to compare cell growth ability between different groups. d Transwell assay indicates impaired abilities of migration and invasion of 786-O and SN12 cells treated with shATF4. Representative graphs (left). Bar graph showing the statistical results (right). e Effect of ATF4 knockdown on the apoptosis rate in 786-O and SN12 cells. f Western blot analysis of mTOR, EMT, and apoptosis-related gene expression in 786-O cells with NC and shATF4. g BALB/c nude mice underwent orthotopic implantation of SN12 cells, stably expressing control shRNA or shATF4, and then tumor masses were resected on day 21. Tumor weights were expressed in terms of mean ± SEM, n = 6 for each group. h H&E and IHC analyses of tissues harvested from the mice tumor masses stained for ki67, and cleaved caspase-3. All functional assays above were independently repeated thrice in triplicate. The data are presented herein as mean ± SEM. p-values were calculated using the two-tailed Student’s t-test (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001)

Two lentiviral vectors with shRNA against ATF4 (shATF4) were constructed, the efficacy of which was confirmed by Western blot on day 4 after lentivirus transduction (Fig. 2b). It was showed that ATF4 knockdown inhibited cell proliferation by MTT assay (Fig. 2c) and impaired migration and invasion abilities by transwell assay (Fig. 2d). Flow cytometry (Fig. 2e) analyses consistently revealed that ATF4 knockdown induced remarkable early apoptosis in both 786-O and SN12 cells.

The important role of EMT has been firmly established in the pathogenesis of metastasis and tumor cell migration. The Akt/mTOR pathway can induce EMT via transcription factors such as Snail, Zeb, and Twist through down regulation of E-cadherin [49]. We then detected several markers related to mTOR, EMT, and apoptosis by Western blot. ATF4 knockdown was found to exert a remarkable effect on the phosphorylation of S6 kinase (S6K) and 4EBP1, a readout of mTORC1 signaling. The increased expression of E-cadherin was observed in 786-O cells transduced with shATF4, together with the concomitant decreased expression of N-cadherin and vimentin. In addition, shATF4-treated cells exhibited an increase in cleaved caspase-3 activity and a reduction in Bcl-2 expression compared with the NC group (Fig. 2f).

In vivo, the orthotopic implantation model in BALB/c nude mice was established by transplanting Luc-labelled SN12 cells, stably transfected with NC or shATF4 under the right kidney capsule. On day 21 after injection, tumor signals by bioluminescent imaging and tumor weight in the shATF4 group were significantly lower than in the NC group (Supplementary Figure S1, Fig. 2g). Consistent with the in vitro results, IHC for tumor tissues showed lower Ki-67 and higher cleaved caspase-3 expressions in shATF4 group (Fig. 2h). Altogether, these findings suggest that ATF4 may serve a pro-survival function by promoting the mTOR signaling pathway and EMT and inhibiting apoptosis in ccRCC.

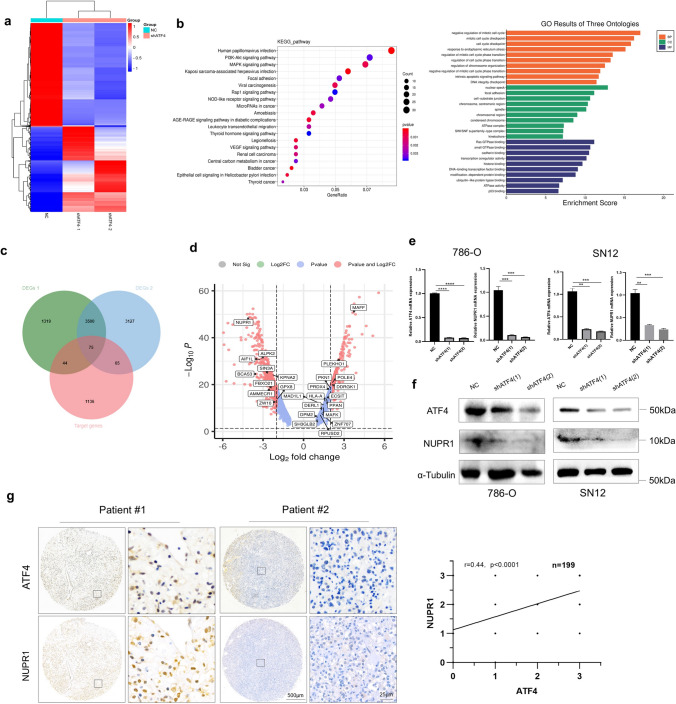

ATF4 deficiency downregulates NUPR1 expression in ccRCC

To verify the molecular mechanisms or signaling pathways involved in ATF4-mediated pro-survival in ccRCC, an RNA-seq analysis of 786-O cells was performed after ATF4 knockdown. A heatmap analysis of differentially expressed genes (DEGs, |fold change|> 2) showed overall changes (Fig. 3a). A Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis and gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis were performed to examine the functional role of ATF4 in ccRCC, which indicated that ATF4 may participate in the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, mitotic cell cycle progress and focal adhesion in ccRCC (Fig. 3b). Overactivation of the mTOR pathway usually leads an abnormal mitotic in cancer cells, and the Aurora kinase A (Aur-A), a member of the mitotic serine/threonine Aurora kinase family, has been shown positive association with p-mTOR in multiple cancer types [50]. The negative regulation of mitotic cell cycle may reveal a downregulation of mTOR pathway. For the focal adhesion, more recent researches provide the evidence that focal adhesion kinase may regulate EMT, which may be associated with the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway [51, 52]. In summary, the results as KEGG and GO enrichment showed are consistent with the previous findings in the Fig. 2f. Target genes transcriptionally regulated by ATF4 were acquired based on chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) results from other studies in the database. A Venn diagram of target genes and DEGs was drawn to screen the potential genes, and 75 potential genes were identified and shown in the DEG volcano plot (Fig. 3c), among which NUPR1 showed the most remarkable fold change (Fig. 3d; http://www.bioinformatics.com.cn).

Fig. 3.

ATF4 deficiency downregulates NUPR1 expression in ccRCC. a Heatmap analysis of DEG function clustering in the ccRCC from NC and shATF4 groups. b Kyoto KEGG pathway enrichment and GO enrichment analysis among DEGs in 786-O cells. c Venn diagram illustrating overlap among DEGs and target gene lists. DEGs 1 (NC vs. shATF4-1), DEGs 2 (NC vs. shATF4-2), target genes (the predicted gene list transcription-regulated by ATF4). d Volcano plot depicting the gene expression differences between NC and shATF4 groups. The horizontal axis represents the log-ratio (gene expression fold change in different samples), while the vertical axis represents the probability for each gene of being differentially expressed. The 75 genes in (c) are shown. e NUPR1 was verified via qRT-PCR experiment in ATF4 knockdown 786-O and SN12 cells. Data are presented in terms of mean ± SEM, n = 3. The p-values were calculated using the two-tailed Student’s t-test (*p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001). (f) NUPR1 expression levels were detected by Western blot in ATF4 knockdown 786-O and SN12 cells. g Expression correlation of ATF4 and NUPR1 based on the IHC score in ccRCC tissue by TMAs (n = 199), representative IHC staining images in two ccRCC patients (left), the statistical result of correlation analysis (right)

The expression correlation between ATF4 and NUPR1 was identified based on ccRCC cases in the TCGA dataset (Supplementary Figure S2a). To verify whether NUPR1 is regulated by ATF4 in ccRCC, the relative mRNA and protein levels of NUPR1 were measured by qRT-PCR and Western blot in 786-O cells and SN12 cells. NUPR1 was found to be downregulated in the shATF4 group (Fig. 3e and f). IHC showed the same results in tumor tissues (Supplementary Figure S2b). Moreover, the linear regression analysis results based on the IHC score for 199 ccRCC tissues by TMAs demonstrated a significant correlation between NUPR1 and ATF4 expressions (Fig. 3g). Overall, our data suggest that ATF4 regulates NUPR1 expression during ccRCC progression.

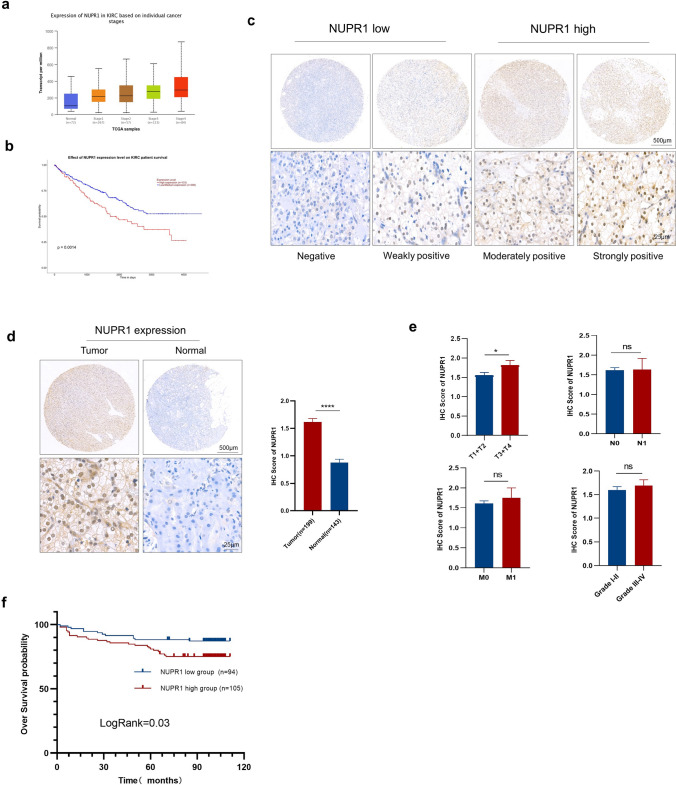

NUPR1 expression is correlated with an advanced stage and prognosis in patients with ccRCC

The data from TCGA revealed that NUPR1 mRNA was significantly upregulated in ccRCC compared with normal tissues and correlated with the tumor clinical stage (Fig. 4a). The OS probability of the NUPR1 high-expression group was significantly lower than the NUPR1 low- and medium-expression groups (Fig. 4b). NUPR1 expression was detected in 199 ccRCC and 143 normal tissues from TMAs via IHC staining. These patients were divided into NUPR1 low- and high-expression groups based on their IHC score according to the variable staining intensity (Fig. 4c). The IHC score for NUPR1 in tumor tissues was markedly higher than the score corresponding to normal tissues (Fig. 4d). NUPR1 expression was also found to be significantly associated with the T stage (Fig. 4e). The Kaplan–Meier analysis showed that the NUPR1 high-expression group was significantly correlated with shorter OS (Fig. 4f). In summary, these findings disclose that NUPR1 expression is upregulated in ccRCC and associated with poor outcomes.

Fig. 4.

NUPR1 expression correlates with the progression and prognosis of ccRCC patients. a The mRNA levels of NUPR1 at different clinical stages of ccRCC tissues in the TCGA dataset. b Kaplan–Meier analysis of OS for all ccRCC patients with low or high NUPR1 expression levels in the TCGA dataset. c Representative images of NUPR1 IHC staining with high or low expression levels in ccRCC tumor tissues by TMAs. d IHC representative images and analysis of NUPR1 expression in tumor tissues (n = 199) and normal tissues (n = 143) by TMAs. e The NUPR1 expression in different clinical TNM stages and histological grades of ccRCC patients (n = 199). f Kaplan–Meier analysis of OS for 199 ccRCC patients in TMAs with low or high NUPR1 expression levels. The data are represented as means ± SEM. The p-values were calculated using the two-tailed Student’s t-test, Mann–Whitney U test, or log-rank test (*p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001)

NUPR1 inhibitor ZZW115 reduces cell proliferation and metastasis and induces apoptosis and ferroptosis

The NUPR1 inhibitor ZZW115 binds strongly the nuclear localization signal (NLS) of NUPR1, which prevents NUPR1 from translocating to the nucleus. ZZW115 acts mechanistically by mimicking NUPR1 inactivation [53]. To explore whether NUPR1 acts as a tumor promoter and serve as a potential therapeutic target in ccRCC, cell viability and transwell assay were conducted to examine the effect of ZZW115 on ccRCC cell growth, migration, and invasion. In vitro experiments revealed that ZZW115 inhibited cell growth, migration and invasion and increased the cell death of 786-O and SN12 cells in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5a, b, and Supplementary Figure S3). TUNEL imaging and flow cytometry showed significantly more apoptotic cells in the ZZW115 group than in the control group (Fig. 5d and c). The Western blot analysis showed lower expression levels of p-AKT/p-mTOR, N-cad, and vimentin in ZZW115-treated 786-O cells than DMSO and increased expressions of E-cad and cleaved caspase-3 (Fig. 5e). In addition, the ZZW115 treatment induced the accumulation of lipid hydroperoxide, suggesting a promotion of ferroptosis (Fig. 5f). Altogether, these findings suggest that ATF4 knockdown may suppress tumor progression by decreasing NUPR1 expression.

Fig. 5.

ZZW115 inhibits cell growth by inducing apoptosis and ferroptosis. a Cell proliferation assay was performed in ccRCC cells (786-O and SN12) treated with ZZW115 for 24 h in a dose-dependent manner. Cell death was assayed using a CCK8 kit. b Transwell assay indicated impaired abilities of migration and invasion of 786-O and SN12 cells treated with ZZW115 (10 μM) for 24 h. Representative graphs (left). Bar graph showing the statistical results (right). c, d Representative images of TUNEL immunofluorescent staining and flow cytometry analyses for apoptosis of 786-O and SN12 cells treated with DMSO or ZZW115 (10 μM) for 24 h. e Western blot of EMT, apoptosis-related, and AKT/mTOR genes expression in 786-O cells with DMSO or ZZW115 (10 μM) for 24 h. f Levels of lipid ROS were analyzed in 786-O cells with DMSO or ZZW115 (10 μM) for 24 h. The data are presented as mean ± SEM, n = 3. The p-values were calculated using the two-tailed Student’s t-test (*p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001)

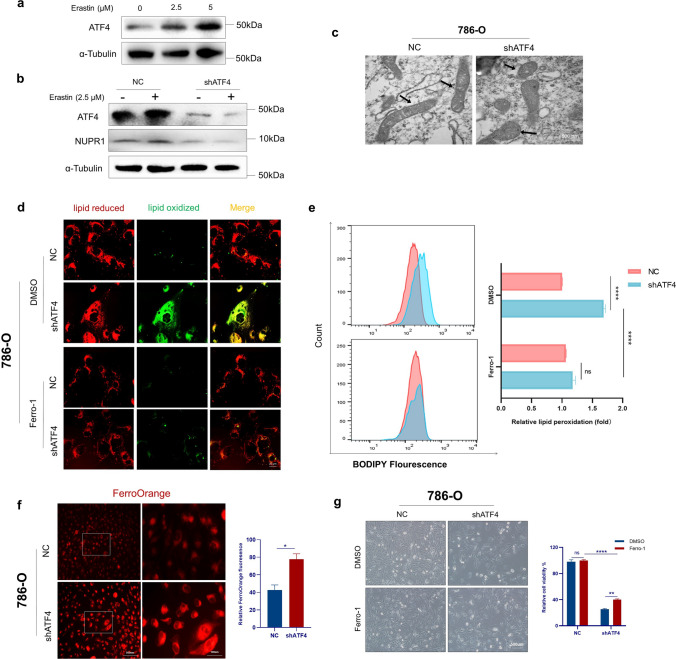

ATF4 knockdown induces ferroptosis by targeting NUPR1

NUPR1 is a critical repressor of ferroptosis, and an NUPR1 inhibitor induces ferroptosis in ccRCC. It was hypothesized that ATF4 knockdown could induce ferroptosis by downregulating NUPR1. Erastin dose-dependently induced cell death in ccRCC cells, which was partially rescued by the ferroptosis inhibitor ferrostatin-1 (Supplementary Figure S4a). Previous studies indicated that ATF4 could also have interaction with erastin-induced stress [42, 43]. Indeed, erastin was found to dose-dependently induce feedback upregulation of ATF4 expression, suggesting that ATF4 may be associated with ferroptosis (Fig. 6a). ATF4 knockdown simultaneously downregulated erastin-induced NUPR1 protein expression (Fig. 6b) and increased erastin-induced lipid peroxidation and cell death (Supplementary Figures S4b and S4c).

Fig. 6.

Knockdown of ATF4 induces ferroptosis and inhibits cell proliferation by targeting NUPR1. a Western blot indicates ATF4 protein expression in 786-O cells following treatment with erastin (0–5 μM) for 24 h. b ATF4 knockdown inhibited erastin-induced (2.5 μM, 24 h) NUPR1 protein expression. c Scanning electron microscopy of 786-O cells transfected with NC or shATF4. Mitochondrion (arrow). d, e Representative immunofluorescent microscope images and flow cytometry analyses of lipid peroxidation levels reported by BODIPY-C11 in 786-O cells transfected with NC or shATF4 in the absence or presence of ferrostatin-1. f Representative immunofluorescent microscope images of FerroOrange (left) and statistical result (right) for relative Fe.2+ level of 786-O cells transfected with NC or shATF4. g 786-O cells were transduced with shATF4 for four days in the absence or presence of ferrostatin-1, followed by bright-field imaging (left) and quantification (right). OD values at 450 nm were used to compare cell growth ability between different groups. The data are presented as mean ± SEM, n = 3. The p-values were estimated using the two-tailed Student’s t-test (*p < .05, ** p < .01, ***p < .001, ****p < .0001)

Treatment with shATF4 induced an evident decrease in mitochondria volume, a distinct reduction (or disappearance) of mitochondrial cristae, and an increase in membrane density, which are described as morphological features in ferroptotic cells (Fig. 6c). Flow cytometry analysis demonstrated a remarkable increase in lipid peroxidation in the shATF4 group compared with the NC group, which was rescued by the ferroptosis inhibitor ferrostatin-1 (Fig. 6d and e).

To examine whether ATF4 knockdown increased Fe2+ levels, an analysis was conducted with the fluorescence probe FerroOrange. The results revealed a significant increase in the relative intracellular Fe2+ fluorescence intensity in shATF4-transfected 786-O compared with the NC group (Fig. 6f). Ferrostatin-1 increased cell viability compared with DMSO in the shATF4 group, partially rescuing cell death by ATF4 knockdown (Fig. 6g). Collectively, these findings indicate that ATF4 knockdown induces ferroptosis by increasing intracellular Fe2+ levels by downregulating NUPR1 expression in ccRCC cells.

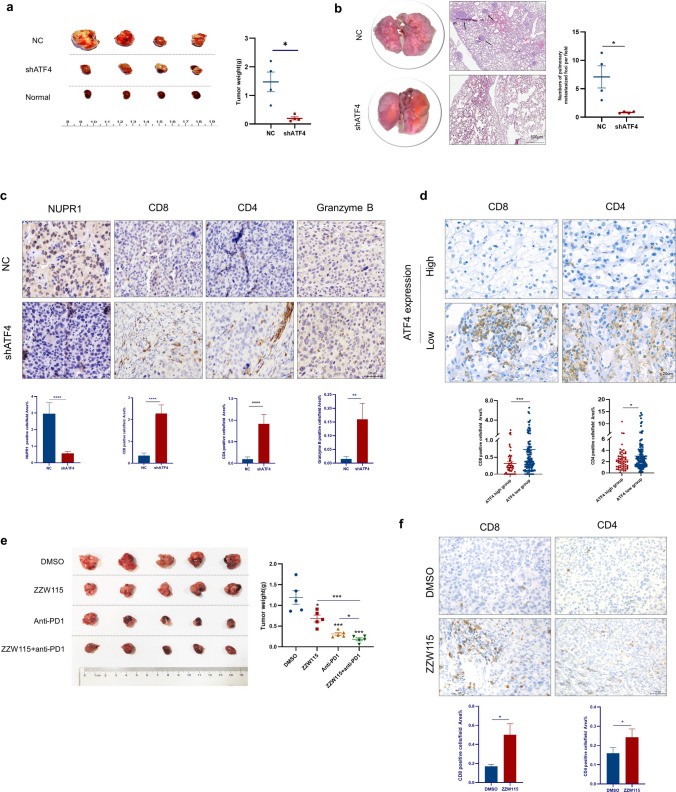

ATF4 knockdown increases the infiltration of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and promotes antitumor immunity in vivo

To investigate whether ATF4 knockdown promotes an antitumor immune response to inhibit tumor growth and metastasis, murine shATF4 (shATF4-M) for RenCa cells was generated and validated by Western blot and proliferation assays on day 4 after lentivirus transduction (Supplementary Figures S5a and S5b). An orthotopic implantation model was established by transplanting RenCa cells with negative control shRNA or shATF4-M into the kidney (Supplementary Figures S5c and S5d). ATF4 knockdown significantly reduced the tumor weight and lung metastasis (Fig. 7a and b).

Fig. 7.

ATF4 knockdown remodels TME and promotes antitumor immunity. a BALB/c mice underwent orthotopic implantation of RenCa cells, stably expressing control shRNA or shATF4 respectively, and then tumor masses were resected on day 14. N = 4 for each group. b Representative H&E staining images and quantitative analysis for the amount of lungs with metastatic nodules (black arrow indicates metastatic nodules). c IHC analysis of tissues harvested from the mice tumor masses stained for NUPR1, CD8, CD4, and granzyme B. d Representative images and statistical results of CD8 and CD4 IHC staining with ATF4 high or low expression level in ccRCC tumor tissues by TMAs (n = 199). e Tumor growth of RenCa cells with ZZW115 and/or anti-PD1 therapy treated in BALB/c mice. n = 5 for each group. f IHC analysis of tumor tissue harvested from the mice treated with DMSO or ZZW115 stained for CD8 and CD4. The data are represented in terms of mean ± SEM, and p-values were calculated using the Mann–Whitney U test (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001)

Genomic analysis has proven that ferroptosis is associated with programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression, immune cell infiltration, and immunotherapy sensitivity [41, 54]. Although ferroptosis may be involved in a diverse and complex TME, it remains largely unclear whether ATF4 influences TME and immunotherapy in ccRCC. The TME alterations were detected in the BALB/c mice, and intratumor infiltration of CD4−, CD8−, and granzyme B+ cells remarkably increased in tumors from the shATF4 group (Fig. 7c). The same tendency was observed in tumor tissues from TMAs (Fig. 7d).

Recent studies have proven that CD8+ T cells suppress tumor growth by inducing ferroptosis. Targeting tumor ferroptosis-associated metabolism may thus improve the efficacy of cancer immunotherapy. A synergistic effect has been reported between PD-L1 blockade antibodies and ferroptosis activators, which suppress tumor growth both in vitro and in vivo [55, 56]. The effect of ATF4 knockdown inducing ferroptosis suggests a treatment strategy of combining immunotherapy with ATF4 pathway inhibition. In this study, to assess the efficacy of the combinatorial therapy, xenograft tumors transplanted with RenCa cells were treated with ZZW115, anti-PD1, or both. The weight of combinatorial-treated tumors was found to be significantly decreased compared with either tumors treated with DMSO or a single agent (Fig. 7e). Consistent with ATF4 knockdown, treatment with ZZW115 remarkably promoted CD4+ and CD8+ T cell infiltration in vivo (Fig. 7f). Collectively, our data indicate that besides impairing proliferation and motility and enhancing apoptosis and ferroptosis in tumor cells, ATF4 knockdown may increase CD4+ and CD8+ T cell infiltration and promote antitumor immunity to suppress tumor growth in vivo, indicating the potential value of targeting ATF4 in treating ccRCC.

Discussion

During tumor development, cancer cells encounter various stressful environmental conditions, such as hypoxia, nutrition deprivation and the effect of drugs [57–60], which requires the metabolic reprogramming of cancer cells. Cancer cells autonomously alter their flux through various metabolic pathways in order to meet the increased bioenergetic and biosynthetic demand as well as mitigate oxidative stress required for cancer cell proliferation and survival [61]. The most striking morphological feature of ccRCC cells is their clear cytoplasm due to lipid and glycogen accumulation, suggesting possible involvement of their metabolism in ccRCC progression [62]. Metabolomics studies have identified extensive remodeling of metabolism in ccRCC, characterized by genetic mutations in targets involved in metabolic pathways covering different processes, such as aerobic glycolysis (Warburg effect), tryptophan, glutamine, arginine, and fatty acids(FAs) metabolism [62], which allows tumor cells to survive in conditions of hypoxia and nutrition deprivation, to synthesize building blocks (proteins, DNA, membranes) for proliferation, and to escape host immunosurveillance and counteract oxidative stress [63, 64]. Lipid droplet formation and increased glutathione (GSH) have been identified as defining features in ccRCC, which counteract damaging ROS to sustain the viability and growth of the malignancy [65–69]. Emerging evidence show that the related genes serving as regulator of lipid-metabolism participate modulating the malignancy progression of ccRCC [70]. A recent study in metabolomics has uncovered a distinctive pattern of heightened absorption and utilization of glucose in ccRCC. This metabolic shift is accompanied by adaptive alterations such as transitioning from oxidative phosphorylation to glycolysis and a rise in lactate production (Warburg effect). The Warburg effect varies depending on the grade, leading to the activation of fatty acid oxidation to meet grade-specific metabolic requirements. The potential use of grade-specific metabolic therapies in ccRCC is also emphasized [62]. Besides so-called Warburg effect, pentose phosphate pathway (PPP), association with the upregulation of G6PDH and NDUFA4L2, is an alternative metabolic pathway rerouting the sugar metabolism [71, 72]. Blocking the flux through this pathway may serve as a novel therapeutic target. The combined analysis of metabolites and transcripts revealed that ccRCC with MUC1 expression exhibited a distinct metabolic shift, specifically involving alterations in the pathways of glucose and lipid metabolism. MUC1 promotes the transition from inflammation to cancer, boosts resistance to treatment, facilitates the spread of tumors, and plays a role in the advancement of cancer [73, 74]. A study through Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR)-based metabolomics combined with transcriptomics showed the increases of creatine, alanine, lactate and pyruvate, and decreases of hippurate, citrate, and betaine in ccRCC patients [75]. The comprehensive quantification of metabolic profiles in ccRCC patients would be an innovative strategy for choosing the optimal therapy for a specific patient [76]. ATF4, a stress-induced transcription factor, is usually elevated to regulate its target genes exerting corresponding functions, and this facilitates cancer cell survival, growth, development, and progression [23–25]. ATF4 activation modulated the expression of lipid metabolism-related genes and potentiated fatty acid oxidation and lipogenesis [77] and also promoted GSH biosynthesis through the mitochondrial one-carbon metabolism pathway [78]. In addition, ATF4 is identified a key role in regulating the response to the Tricarboxylic Acid (TCA) cycle inhibition and countering the associated redox and amino acid stress [79]. Depletion of p62 in the stroma reconfigures metabolic processes to withstand glutamine deficiency, leading to the elevation of ATF4 levels in order to support tumor growth mediated by Asparagine [59]. In further study and subsequent analysis, worse patient survival was shown to correlate with upregulation of pentose phosphate pathway and fatty acid synthesis pathway genes, and downregulation of TCA cycle genes [65]. Based on the above, ATF4 is bound to play a key role in the progression of ccRCC. In this study, ATF4 expression is upregulated in ccRCC and associated with poor outcomes, and ATF4 knockdown was found to diminish ccRCC cell proliferation, migration, and invasion by suppressing mTOR activity and the EMT pathway.

In addition, ccRCC is distinguished as one of the most heavily infiltrated tumors by the immune cells. The characteristics of the tumor microenvironment play a significant role in shaping the biology of the disease and can impact the effectiveness of systemic treatment [80]. CD8 + T cells derived from patients with RCC show impaired proliferation and are more prone to apoptotic cell death due to decreased levels of JAK3 and MCL-1 [81]. Distinct characteristics of the tumor microenvironment, encompassing angiogenesis and inflammatory markers, have demonstrated notable variations in their reactions to immune checkpoint blockade and anti-angiogenic treatments. The emergence of immunotherapy has changed the treatment strategy of many malignant tumors. Although several effective immune checkpoint blockade regimens have emerged as viable options in the evolving frontline treatments for metastatic ccRCC [80, 82], not all ccRCC patients respond to these treatments. Therefore, it is crucial to carefully choose the right patients and to determine key biomarkers that can predict the effectiveness of treatment. Recent study shows that the metabolic profile of serum samples can serve as a reliable indicator for predicting the response to therapy in NSCLC [83]. The antiangiogenic effects of bevacizumab may stem from its direct impact on angiogenic cytokines secreted by tumor cells, as well as its indirect influence on the secretion of pro-angiogenic factors by inflammatory stromal cells [84]. Recent studies suggest that MUC1 colocalized with PTX3, playing a role in the pathways of glucose and lipid metabolism in ccRCC, has the ability to influence the immunoflogosis through the activation of complement system classical pathway and the regulation of immune infiltrate, ultimately facilitating the establishment of an immune-suppressive microenvironment [85–87]. And also, many studies have shown that kynurenine (KYN) pathway plays an important role in cancer progression through the accumulation of immunosuppressive metabolites such as KYN [88]. Besides the findings above, more work involving other numerous metabolic pathways needs to be done to explore how the immune cells work and interact with cancer and other cancer-associated cells in such a complex tumor microenvironment [89].

As is known, ferroptosis is associated with iron-dependent lipid peroxidation. In view of metabolic abnormality in ccRCC, it is reasonable to hypothesize that ccRCC tumors would exhibit a higher susceptibility to ferroptosis. Indeed, early in vitro cell toxicity screens found that ccRCC derived cell lines were among the most vulnerable cancer cell lines to ferroptosis inducers [90, 91]. Several genes, for example SET-domain-containing 2 (SETD2), Acyl-CoA synthetase 3 (ACSL3), dipeptidyl peptidase 9 (DPP9), could modulate ferroptosis sensitivity in different manners [92–94]. Our data also revealed that ATF4 is required for NUPR1 expression in response to ferroptosis activators in ccRCC, and ATF4 knockdown triggered ferroptosis by increasing Fe2+ accumulation in ccRCC. Thus, the induction of ferroptosis could offer a potential therapeutic approach to treat ccRCC.

Ferroptotic cancer cells can release a set of immunostimulatory signals, allowing immune cells to properly locate the site of dying tumor cells [95]. Several studies have demonstrated that ferroptosis inducers could be associated with TME features and enhance the efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy [41, 54, 55, 96]. Immunostimulatory signals released by ferroptotic cancer cells can promote the phenotypic maturation of dendritic cells and increase the efficiency of macrophages, particularly M1-like tumor-associated macrophages, in the phagocytosis of ferroptotic cancer cells, strengthening CD8+ T cell-mediated tumor suppression. Interferon-γ secreted by CD8+ T cells repress solute carrier family7 member11 (SLC7A11) expression in cancer cells, which promotes cancer cell ferroptosis. In addition, the induction of ferroptosis can impair regulatory T (Treg) cells, myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), and M2-like TAMs, augmenting antitumor immunity [97]. Memory CD4+ T cells and M0 macrophages can be activated via ferroptosis-related lncRNA in hepatocellular carcinoma [98]. Recent studies have assessed correlations between specific molecular signatures, the tumor microenvironment and clinical outcome.

Multiple studies have showed that PBRM1 or BAP1 mutation may be associated with different inflamed immune microenvironment [99–102]. Metabolic changes mentioned above, including glucose uptake, increases in antioxidant biosynthesis, and accumulation of lipid droplets, are evolutionarily early events in tumorigenesis that occur in the background of widespread intratumoral genetic diversification and extensive immune infiltration [65, 103, 104]. Gene related to immune infiltration significantly was correlated with the variation of numerous metabolites, indicating that the immune microenvironment and metabolism coevolve in ccRCC tumors. In ccRCC, ATF4 is reasonable to modulate immune cell infiltration considering the role in metabolic reprogramming. Our study consistently confirmed, in vivo, that activated CD8+ T cells enhanced ferroptosis-specific lipid peroxidation in tumor cells. In turn, increased ferroptosis contributes to the antitumor efficacy of immunotherapy. Therefore, targeting the tumor ferroptosis pathway would be a therapeutic approach to use in combination with checkpoint blockade [55]. The present study confirms that ATF4 knockdown and NUPR1 inhibitor treatment increased CD4+ and CD8+ T cell infiltration, which is presumably a result of ferroptosis or consequence of metabolic changes by ATF4 knockdown. The potential beneficial effects of NUPR1 inhibitors in combination with anti-PD1 in ccRCC were confirmed via animal experiments. However, additional studies are required to identify these mechanisms experimentally.

Reports have described how ATF4 promotes ER stress-induced cell death by targeting downstream genes [105, 106], and in some contexts, ATF4 has been found to induce a pro-apoptotic effect by dimerizing with C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP) [107–109]. Interestingly, in our study, ATF4 knockdown promoted apoptosis in ccRCC cells, which suggests that ATF4 plays an anti-apoptotic function in a CHOP-independent manner. It was hypothesized that ATF4 knockdown could increase vulnerability to cellular stress during tumor growth, thereby resulting in the indirect induction of cell death. Consistently, inhibiting cell growth by ATF4 knockdown was partially rescued by ferrostatin-1 treatment (Fig. 6g). The transcriptional regulation of ATF4 is, therefore, complex, and multiple pathways may be involved in ATF4-mediated cell biological processes. ATF4 exhibits a dual functionality within tumor cells [110]. On the one hand, it regulates genes associated with amino acid transportation and metabolism, protection against oxidative stress, and maintenance of protein homeostasis [111, 112]. On the other hand, ATF4 can trigger apoptosis, cell-cycle arrest, and senescence [107, 108, 113–117]. ATF4 induces GADD34, leading to a negative feedback loop involving dephosphorylation of eIF2a and restoration of translation [112]. ATF4 exerts a dual effect on mTOR activity, whereby it promotes amino acid availability through autophagy and concurrently upregulates adaptive genes. Conversely, ATF4 also induces the expression of mTOR repressors, namely, SESN2, DDIT4, and REDD1 [118–120]. The ATF4-initiated transcriptional program concurrently diminishes the expression of the anti-apoptotic BCL2 protein while augmenting pro-apoptotic signaling mediated by the proteins BIM, NOXA, and PUMA [121, 122]. Consequently, the outcome of ATF4 activation is highly context-dependent.

Based on previous studies and the results obtained in this study, we conclude that NUPR1 is a potential key target gene of ATF4 and serves as a predictor of ccRCC [123]. ATF4 and NUPR1 were upregulated in ccRCC tissues and significantly associated with poor outcomes (Figs. 1c, f, 4a, e, and f), and the NUPR1 inhibitor, ZZW115, suppressed ccRCC tumor growth in vitro and in vivo (Figs. 5a and 7e). NUPR1, a stress-induced protein, engages in a positive feedback loop with ATF4. NUPR1 was found to present nuclear localization complexed to other protein(s) or nucleic acids in sub-confluent cells but localized throughout the whole cell in those grown to high density or an arrested Go state of the cells, indicating the nuclear import and export of NUPR1. It is reported that NUPR1 exists in the cell as part of protein complexes and directs their subcellular localization to regulate the protein function [124]. An architectural role in transcription, already proposed for NUPR1, is compatible with nuclear localization [125]. ATF4 is confirmed to regulate NUPR1 transcriptionally [126]. As our results confirm, NUPR1 and ATF4 present a nuclear localization, suggesting the function of transcription. However, a cytoplasmic localization of NUPR1 is reported in papillary carcinomas, which might reflect disease progression. NUPR1 expression is consistently associated with resistance to several drugs [127]. NUPR1 silencing reverses sorafenib resistance in ccRCC by targeting the PTEN/AKT/mTOR pathway [123]. And more relevant research on NUPR1 in ccRCC is rarely reported. Our study provides some evidence that NUPR1 play a role in promoting the ccRCC progression. Further investigations must be conducted to uncover the molecular mechanism of difference in the localization of NUPR1 based on cell density, environmental changes, tumor type, and other factors.

Therapeutic interventions can also contribute to a stressed state [128]. Unsurprisingly, ATF4 mediates resistance to therapeutic agents in various cancers. Therefore, suppressing the ATF4/NUPR1 pathway may reduce the capacity for drug-induced stress in tumor cells, resulting in cell death induction, proliferation inhibition, and increased therapeutic efficacy. Above all, our data support that ATF4/NUPR1 axis plays a pro-survival role by activating the AKT/mTOR pathway and decreasing the apoptosis and ferroptosis cell death in ccRCC. Furthermore, the current study provides evidence that targeting ATF4/NUPR1 with or without a ferroptosis inducer may be a new effective treatment for ccRCC.

Conclusions

ATF4 knockdown inhibits proliferation and motility and induces apoptosis and ferroptosis via NUPR1 in ccRCC, increasing the infiltration of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and enhancing antitumor immunity. Therefore, targeting ATF4/NUPR1 may be a potential alternative therapeutic strategy for controlling ccRCC progression. Further studies are required to elucidate the mechanism whereby ATF4 exerts antitumor immunity.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author contributions

Xin Ma, Yan Huang, Hongzhao Li and Yongliang Lu conceived the project and designed the experiments. Weihao Chen and Yundong Xuan performed the cell experiments.Yongliang Lu, Yundong Xuan, Shengpan Wu and Hanfeng Wang conducted the plasmid construction and molecular experiments. Tao Guo, Chenfeng Wang and Shuo Tian provided the human tissue samples and clinical information. Yongliang Lu and Yundong Xuan performed the immunofluorescence assays. Yongliang Lu, Weihao Chen, Shengpan Wu, Xupeng zhao, Wenlei Zhao and Tao Guo performed the IHC and H&E staining. Yongliang Lu, Weihao Chen, Yundong Xuan, Shengpan Wu, Huaikang Li, Dong Lai and Tao Guo performed the animal experiments. Yongliang Lu, Xiubin Li and Xing Huang performed the bioinformatics analyses and conducted the RNA sequencing analysis. Yongliang Lu Weihao chen and Yan Huang analyzed and interpreted the data. Yan Huang, Hongzhao Li and Xin Ma supervised the overall execution of the experiments. The manuscript was written by Yongliang Lu with support from Baojun Wang, Xu Zhang, Yan Huang, Hongzhao Li and Xin Ma. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Project number: 82372704) and Youth Fund of Chinese PLA General Hospital (22QNFC090).

Data availability

The original data of RNA-seq that supports the findings of this study is available on request from us and other data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Research Ethics Committee of the PLA General Hospital. The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the PLA General Hospital. The study is reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines.

Consent to publication

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patients to publish this paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Yongliang Lu, Weihao Chen and Yundong Xuan have equally contributed to this work.

Contributor Information

Hongzhao Li, Email: urolancet@126.com.

Yan Huang, Email: dr.huangyan301@foxmail.com.

Xin Ma, Email: mxin301@126.com.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, et al. Estimating the global cancer incidence and mortality in 2018: GLOBOCAN sources and methods. Int J Cancer. 2019;144(8):1941–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, et al. Cancer statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(1):7–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen HT, McGovern FJ. Renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(23):2477–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ricketts CJ, et al. SnapShot: renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2016;29(4):610-610.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Latif F, et al. Identification of the von Hippel-Lindau disease tumor suppressor gene. Science. 1993;260(5112):1317–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maxwell PH, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 modulates gene expression in solid tumors and influences both angiogenesis and tumor growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94(15):8104–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flamme I, Krieg M, Plate KH. Up-regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor in stromal cells of hemangioblastomas is correlated with up-regulation of the transcription factor HRF/HIF-2alpha. Am J Pathol. 1998;153(1):25–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krieg M, et al. Up-regulation of hypoxia-inducible factors HIF-1alpha and HIF-2alpha under normoxic conditions in renal carcinoma cells by von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor gene loss of function. Oncogene. 2000;19(48):5435–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maxwell PH, et al. The tumour suppressor protein VHL targets hypoxia-inducible factors for oxygen-dependent proteolysis. Nature. 1999;399(6733):271–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keith B, Johnson RS, Simon MC. HIF1α and HIF2α: sibling rivalry in hypoxic tumour growth and progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;12(1):9–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takahashi A, et al. Markedly increased amounts of messenger RNAs for vascular endothelial growth factor and placenta growth factor in renal cell carcinoma associated with angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 1994;54(15):4233–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network Analysis working group. Comprehensive molecular characterization of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Nature. 2013;499(7456):43–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Monzon FA, et al. Chromosome 14q loss defines a molecular subtype of clear-cell renal cell carcinoma associated with poor prognosis. Mod Pathol. 2011;24(11):1470–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Monzon FA, et al. Whole genome SNP arrays as a potential diagnostic tool for the detection of characteristic chromosomal aberrations in renal epithelial tumors. Mod Pathol. 2008;21(5):599–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peña-Llopis S, et al. BAP1 loss defines a new class of renal cell carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2012;44(7):751–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Varela I, et al. Exome sequencing identifies frequent mutation of the SWI/SNF complex gene PBRM1 in renal carcinoma. Nature. 2011;469(7331):539–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dalgliesh GL, et al. Systematic sequencing of renal carcinoma reveals inactivation of histone modifying genes. Nature. 2010;463(7279):360–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ljungberg B, et al. European association of urology guidelines on renal cell carcinoma: the 2022 update. Eur Urol. 2022. 10.1016/j.eururo.2022.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dejeans N, et al. Novel roles of the unfolded protein response in the control of tumor development and aggressiveness. Semin Cancer Biol. 2015;33:67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maurel M, et al. Controlling the unfolded protein response-mediated life and death decisions in cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2015;33:57–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Urra H, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and the hallmarks of cancer. Trends Cancer. 2016;2(5):252–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sullivan LB, Chandel NS. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species and cancer. Cancer Metab. 2014;2:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kilberg MS, Shan J, Su N. ATF4-dependent transcription mediates signaling of amino acid limitation. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2009;20(9):436–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luhr M, et al. The kinase PERK and the transcription factor ATF4 play distinct and essential roles in autophagy resulting from tunicamycin-induced ER stress. J Biol Chem. 2019;294(20):8197–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rozpedek W, et al. The role of the PERK/eIF2α/ATF4/CHOP signaling pathway in tumor progression during endoplasmic reticulum stress. Curr Mol Med. 2016;16(6):533–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sandi MJ, et al. p8 expression controls pancreatic cancer cell migration, invasion, adhesion, and tumorigenesis. J Cell Physiol. 2011;226(12):3442–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Emma MR, et al. NUPR1, a new target in liver cancer: implication in controlling cell growth, migration, invasion and sorafenib resistance. Cell Death Dis. 2016;7(6): e2269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guo X, et al. Lentivirus-mediated RNAi knockdown of NUPR1 inhibits human nonsmall cell lung cancer growth in vitro and in vivo. Anat Rec (Hoboken). 2012;295(12):2114–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim KS, et al. Expression and roles of NUPR1 in cholangiocarcinoma cells. Anat Cell Biol. 2012;45(1):17–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li J, et al. Knockdown of NUPR1 inhibits the proliferation of glioblastoma cells via ERK1/2, p38 MAPK and caspase-3. J Neurooncol. 2017;132(1):15–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zeng C, et al. Knockdown of NUPR1 inhibits the growth of U266 and RPMI8226 multiple myeloma cell lines via activating PTEN and caspase activation-dependent apoptosis. Oncol Rep. 2018;40(3):1487–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhou C, et al. Long noncoding RNA FEZF1-AS1 promotes osteosarcoma progression by regulating the miR-4443/NUPR1 axis. Oncol Res. 2018;26(9):1335–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yu J, et al. Oncogenic role of NUPR1 in ovarian cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2020;13:12289–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jiang L, et al. NUPR1 participates in YAP-mediate gastric cancer malignancy and drug resistance via AKT and p21 activation. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2021;73(6):740–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tang K, et al. Enhancement of gemcitabine sensitivity in pancreatic cancer by co-regulation of dCK and p8 expression. Oncol Rep. 2011;25(4):963–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jiang W, et al. CircRNA HIPK3 promotes the progression of oral squamous cell carcinoma through upregulation of the NUPR1/PI3K/AKT pathway by sponging miR-637. Ann Transl Med. 2021;9(10):860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu J, et al. NUPR1 is a critical repressor of ferroptosis. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu M, et al. Regulated lytic cell death in breast cancer. Cell Biol Int. 2022;46(1):12–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liang C, et al. Recent progress in ferroptosis inducers for cancer therapy. Adv Mater. 2019;31(51): e1904197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhou B, et al. Ferroptosis is a type of autophagy-dependent cell death. Semin Cancer Biol. 2020;66:89–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bai D, et al. Genomic analysis uncovers prognostic and immunogenic characteristics of ferroptosis for clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2021;25:186–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee AS. Glucose-regulated proteins in cancer: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14(4):263–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sun X, et al. HSPB1 as a novel regulator of ferroptotic cancer cell death. Oncogene. 2015;34(45):5617–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gao Y, et al. KLF6 suppresses metastasis of clear cell renal cell carcinoma via transcriptional repression of E2F1. Cancer Res. 2017;77(2):330–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hamanishi J, et al. Programmed cell death 1 ligand 1 and tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T lymphocytes are prognostic factors of human ovarian cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(9):3360–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Horikawa N, et al. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in ovarian cancer inhibits tumor immunity through the accumulation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23(2):587–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rao X, et al. An improvement of the 2ˆ(-delta delta CT) method for quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction data analysis. Biostat Bioinform Biomath. 2013;3(3):71–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen W, et al. GTSE1 promotes tumor growth and metastasis by attenuating of KLF4 expression in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Lab Invest. 2022;102(9):1011–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Karimi Roshan M, et al. Role of AKT and mTOR signaling pathways in the induction of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) process. Biochimie. 2019;165:229–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang W, et al. Aurora-A/ERK1/2/mTOR axis promotes tumor progression in triple-negative breast cancer and dual-targeting Aurora-A/mTOR shows synthetic lethality. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10(8):606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zheng D, et al. FAK regulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition in adenomyosis. Mol Med Rep. 2018;18(6):5461–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cicchini C, et al. TGFbeta-induced EMT requires focal adhesion kinase (FAK) signaling. Exp Cell Res. 2008;314(1):143–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lan W, et al. ZZW-115-dependent inhibition of NUPR1 nuclear translocation sensitizes cancer cells to genotoxic agents. JCI Insight. 2020;5(18): e138117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang S, et al. Comprehensive analysis of ferroptosis regulators with regard to PD-L1 and immune infiltration in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9: 676142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang W, et al. CD8(+) T cells regulate tumour ferroptosis during cancer immunotherapy. Nature. 2019;569(7755):270–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tang R, et al. Ferroptosis, necroptosis, and pyroptosis in anticancer immunity. J Hematol Oncol. 2020;13(1):110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Garris CS, Pittet MJ. ER stress in dendritic cells promotes cancer. Cell. 2015;161(7):1492–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Todoric J, et al. Stress-activated NRF2-MDM2 cascade controls neoplastic progression in pancreas. Cancer Cell. 2017;32(6):824-839.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Linares JF, et al. ATF4-induced metabolic reprograming is a synthetic vulnerability of the p62-deficient tumor stroma. Cell Metab. 2017;26(6):817-829.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Seton-Rogers S. Oncogenes: coping with stress. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017;17(2):76–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Martínez-Reyes I, Chandel NS. Cancer metabolism: looking forward. Nat Rev Cancer. 2021;21(10):669–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bianchi C, et al. The glucose and lipid metabolism reprogramming is grade-dependent in clear cell renal cell carcinoma primary cultures and is targetable to modulate cell viability and proliferation. Oncotarget. 2017;8(69):113502–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lucarelli G, et al. Metabolomic insights into pathophysiological mechanisms and biomarker discovery in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2019;19(5):397–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.De Marco S, et al. The cross-talk between Abl2 tyrosine kinase and TGFβ1 signalling modulates the invasion of clear cell Renal Cell Carcinoma cells. FEBS Lett. 2023;597(8):1098–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hakimi AA, et al. An integrated metabolic atlas of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2016;29(1):104–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Qiu B, et al. HIF2α-dependent lipid storage promotes endoplasmic reticulum homeostasis in clear-cell renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Discov. 2015;5(6):652–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tan SK, et al. Obesity-dependent adipokine chemerin suppresses fatty acid oxidation to confer ferroptosis resistance. Cancer Discov. 2021;11(8):2072–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wettersten HI, et al. Grade-dependent metabolic reprogramming in kidney cancer revealed by combined proteomics and metabolomics analysis. Cancer Res. 2015;75(12):2541–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.di Meo NA, et al. The dark side of lipid metabolism in prostate and renal carcinoma: novel insights into molecular diagnostic and biomarker discovery. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2023;23(4):297–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bombelli S, et al. 36-kDa annexin A3 isoform negatively modulates lipid storage in clear cell renal cell carcinoma cells. Am J Pathol. 2020;190(11):2317–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lucarelli G, et al. Metabolomic profile of glycolysis and the pentose phosphate pathway identifies the central role of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase in clear cell-renal cell carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2015;6(15):13371–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lucarelli G, et al. Integrated multi-omics characterization reveals a distinctive metabolic signature and the role of NDUFA4L2 in promoting angiogenesis, chemoresistance, and mitochondrial dysfunction in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Aging (Albany NY). 2018;10(12):3957–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lucarelli G, et al. MUC1 tissue expression and its soluble form CA15–3 identify a clear cell renal cell carcinoma with distinct metabolic profile and poor clinical outcome. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(22):13968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Milella M, et al. The role of MUC1 in renal cell carcinoma. Biomolecules. 2024;14(3):315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ragone R, et al. Renal cell carcinoma: a study through NMR-based metabolomics combined with transcriptomics. Diseases. 2016;4(1):7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.di Meo NA, et al. Renal cell carcinoma as a metabolic disease: an update on main pathways, potential biomarkers, and therapeutic targets. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(22):14360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wang C, et al. ATF4 regulates lipid metabolism and thermogenesis. Cell Res. 2010;20(2):174–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.van der Mijn JC, et al. Transcriptional and metabolic remodeling in clear cell renal cell carcinoma caused by ATF4 activation and the integrated stress response (ISR). Mol Carcinog. 2022;61(9):851–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ryan DG, et al. Disruption of the TCA cycle reveals an ATF4-dependent integration of redox and amino acid metabolism. Elife. 2021;10: e72593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Vuong L, et al. Tumor microenvironment dynamics in clear-cell renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Discov. 2019;9(10):1349–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gigante M, et al. miR-29b and miR-198 overexpression in CD8+ T cells of renal cell carcinoma patients down-modulates JAK3 and MCL-1 leading to immune dysfunction. J Transl Med. 2016;14:84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lasorsa F, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in renal cell carcinoma: molecular basis and rationale for their use in clinical practice. Biomedicines. 2023;11(4):1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ghini V, et al. Metabolomics to assess response to immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12(12):3574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tamma R, et al. Microvascular density, macrophages, and mast cells in human clear cell renal carcinoma with and without bevacizumab treatment. Urol Oncol. 2019;37(6):355.e11-355.e19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lucarelli G, et al. MUC1 expression affects the immunoflogosis in renal cell carcinoma microenvironment through complement system activation and immune infiltrate modulation. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(5):4814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lasorsa F, et al. Complement system and the kidney: its role in renal diseases, kidney transplantation and renal cell carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(22):16515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Netti GS, et al. PTX3 modulates the immunoflogosis in tumor microenvironment and is a prognostic factor for patients with clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Aging (Albany NY). 2020;12(8):7585–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lucarelli G, et al. Activation of the kynurenine pathway predicts poor outcome in patients with clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Urol Oncol. 2017;35(7):461.e15-461.e27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lasorsa F, et al. Cellular and molecular players in the tumor microenvironment of renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Med. 2023;12(12):3888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Yang WS, et al. Regulation of ferroptotic cancer cell death by GPX4. Cell. 2014;156(1–2):317–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zou Y, et al. A GPX4-dependent cancer cell state underlies the clear-cell morphology and confers sensitivity to ferroptosis. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):1617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Xue W, et al. Knockdown of SETD2 promotes erastin-induced ferroptosis in ccRCC. Cell Death Dis. 2023;14(8):539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Chang K, et al. DPP9 stabilizes NRF2 to suppress ferroptosis and induce sorafenib resistance in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Can Res. 2023;83(23):3940–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Klasson TD, et al. ACSL3 regulates lipid droplet biogenesis and ferroptosis sensitivity in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Metab. 2022;10(1):14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Friedmann Angeli JP, Krysko DV, Conrad M. Ferroptosis at the crossroads of cancer-acquired drug resistance and immune evasion. Nat Rev Cancer. 2019;19(7):405–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Yu B, et al. Magnetic field boosted ferroptosis-like cell death and responsive MRI using hybrid vesicles for cancer immunotherapy. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):3637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lei G, Zhuang L, Gan B. Targeting ferroptosis as a vulnerability in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2022;22(7):381–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Xu Z, et al. Construction of a ferroptosis-related nine-lncRNA signature for predicting prognosis and immune response in hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Immunol. 2021;12: 719175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Gao W, et al. Inactivation of the PBRM1 tumor suppressor gene amplifies the HIF-response in VHL-/- clear cell renal carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114(5):1027–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Nargund AM, et al. The SWI/SNF protein PBRM1 restrains VHL-loss-driven clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Cell Rep. 2017;18(12):2893–906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Clark DJ, et al. Integrated proteogenomic characterization of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Cell. 2019;179(4):964-983.e31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Wang T, et al. An empirical approach leveraging tumorgrafts to dissect the tumor microenvironment in renal cell carcinoma identifies missing link to prognostic inflammatory factors. Cancer Discov. 2018;8(9):1142–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Gerlinger M, et al. Intratumor heterogeneity and branched evolution revealed by multiregion sequencing. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(10):883–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Reznik E, et al. A landscape of metabolic variation across tumor types. Cell Syst. 2018;6(3):301-313.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Armstrong JL, et al. Regulation of endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced cell death by ATF4 in neuroectodermal tumor cells. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(9):6091–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Huang H, et al. Anacardic acid induces cell apoptosis associated with induction of ATF4-dependent endoplasmic reticulum stress. Toxicol Lett. 2014;228(3):170–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Han J, et al. ER-stress-induced transcriptional regulation increases protein synthesis leading to cell death. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15(5):481–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Matsumoto H, et al. Selection of autophagy or apoptosis in cells exposed to ER-stress depends on ATF4 expression pattern with or without CHOP expression. Biol Open. 2013;2(10):1084–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Teske BF, et al. CHOP induces activating transcription factor 5 (ATF5) to trigger apoptosis in response to perturbations in protein homeostasis. Mol Biol Cell. 2013;24(15):2477–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Wortel IMN, et al. Surviving stress: modulation of ATF4-mediated stress responses in normal and malignant cells. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2017;28(11):794–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Harding HP, et al. An integrated stress response regulates amino acid metabolism and resistance to oxidative stress. Mol Cell. 2003;11(3):619–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]