Abstract

Quaternary ammonium compounds (QACs) are a biologically active group of chemicals with a wide range of different applications. Due to their strong antibacterial properties and broad spectrum of activity, they are commonly used as ingredients in antiseptics and disinfectants. In recent years, the spread of bacterial resistance to QACs, exacerbated by the spread of infectious diseases, has seriously threatened public health and endangered human lives. Recent trends in this field have suggested the development of a new generation of QACs, in parallel with the study of bacterial resistance mechanisms. In this work, we present a new series of quaternary 3-substituted quinuclidine compounds that exhibit potent activity across clinically relevant bacterial strains. Most of the derivatives had minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs) in the low single-digit micromolar range. Notably, QApCl and QApBr were selected for further investigation due to their strong antibacterial activity and low toxicity to human cells along with their minimal potential to induce bacterial resistance. These compounds were also able to inhibit the formation of bacterial biofilms more effectively than commercial standard, eradicating the bacterial population within just 15 min of treatment. The candidates employ a membranolytic mode of action, which, in combination with the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), destabilizes the bacterial membrane. This treatment results in a loss of cell volume and alterations in surface morphology, ultimately leading to bacterial cell death. The prominent antibacterial potential of quaternary 3-aminoquinuclidines, as exemplified by QApCl and QApBr, paves the way for new trends in the development of novel generation of QACs.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-77647-5.

Keywords: Quaternary ammonium salts, 3-substituted quinuclidine, Biological activity, Mode of antibacterial action

Subject terms: Chemistry, Medicinal chemistry, Drug discovery and development

Introduction

The unique biological potential and physicochemical properties of quaternary ammonium compounds (QACs) play a central role in modern healthcare making them indispensable components in the fight against microbial pathogens and in maintaining public health1. Since their initial introduction as highly effective agents for disinfecting surgical surfaces, QACs have quickly become ingredients in numerous commercial products covering a wide range of applications and industries2. Due to their extensive use, QACs are produced in high volumes generating approximately $1.8 billion in sales which is expected to grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 4.2–4.7% over the next several years3,4.

Since QACs are ionic compounds, two distinct parts of the structure can be differentiated: the positively charged cationic amphiphile and the corresponding counterion. While the counterion primarily influences solubility, numerous studies have consistently shown its minimal impact on bioactivity4. In contrast, the cationic amphiphile constitutes the bioactive core, with its chemical composition and physicochemical attributes significantly influencing bioactivity5. The hydrophilic moiety of the cationic amphiphile comprises a polar head characterized by a positively charged nitrogen as a part of the quaternary ammonium cation. Conversely, the hydrophobic components consist of alkyl and/or aryl substituents, which play pivotal roles in determining optimal biological activity. Typically, elongated alkyl chains function as dynamic extensions forming integral elements within the structure6.

One of the most important features of QACs is their ability to disrupt the cell membranes of microorganisms, leading to their inactivation and eventual death. The proposed mechanism of action involves adsorption to the membrane, which is triggered by an electrostatic interaction between the positively charged nitrogen of the QACs and the negatively charged groups on the membrane surface7–9. Consequently, concentration-dependent adsorption, followed by subsequent penetration of alkyl chains, disrupts the membrane’s structural integrity, resulting in heightened permeability and leakage of intracellular components. With increasing concentrations of QACs, this disruption impairs vital cellular processes like osmoregulation and nutrient uptake, ultimately leading to cellular dysfunction10–12. In addition, QACs can inhibit the bacterial respiratory chain, which further impairs energy production13. The cumulative effect of membrane damage and cellular dysfunction eventually leads to bacterial cell death. This mechanism underlines the strong antimicrobial effect of quaternary ammonium compounds and their crucial role in fighting the spread of microbial infections1.

However, despite their potent antimicrobial effects, their widespread use has led to the emergence of bacterial resistance, presenting a significant challenge in infection control and public health14. Additionally, studies have shown that these compounds can be toxic to various organisms, including aquatic and terrestrial species, raising concerns about their safety and ecological impact15.

The development of resistance to QACs primarily stems from prolonged exposure to these compounds at subMIC concentrations, allowing bacteria to adapt and evolve mechanisms to circumvent their antimicrobial effects16. One of the key mechanisms of resistance involves the upregulation of Qac efflux pumps, which actively remove QACs from bacterial cells, thereby reducing their intracellular concentration and rendering them less effective. Additionally, alterations in membrane composition and charge can hinder the binding of QACs to bacterial cell membranes, diminishing their ability to disrupt membrane integrity and exert antimicrobial activity17.

To address the growing concern of QACs resistance, several innovative strategies aimed at circumventing or overcoming resistance mechanisms have been proposed. One such strategy involves structural modifications which can be used to develop analogs with enhanced antimicrobial potency or altered modes of action that bypass resistance mechanisms4,18. Such modifications may include altering the length or branching of alkyl or aryl groups5, addition of more positive nitrogen centers19–21, introducing novel functional groups, or designing molecules that degrade rapidly2,22. These design choices promote faster degradation, reducing bacteria’s exposure time to the active agents and thus effectively combating resistance23.

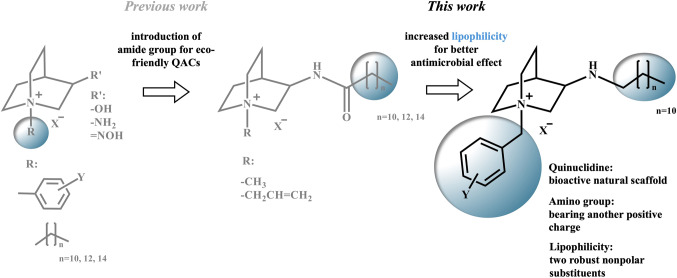

In our recent research on 3-substituted quinuclidine QACs, we have proposed promising solutions to overcome some challenges in the field. We focused on using the natural bioactive scaffold quinuclidine as a base for quaternization, resulting in a class of compounds bearing polar substituents at the C-3 position and lipophilic substituent at the quaternary center24–27. This approach confirmed that quaternizing natural scaffolds is a viable strategy for crafting new broad-spectrum antimicrobials (Fig. 1). Concerned with their high toxicity and ecological impact, we subsequently explored a second class of derivatives. These derivatives feature a quinuclidine backbone substituted at the C-3 atom with an amide group, extended by long alkyl chains of varying lengths and methyl or allyl substituent at the quaternary center28.

Figure 1.

Overview of 3-substituted quinuclidine QACs structures form our previous and current work where X = Br/I, and Y = Cl/Br/NO2/CH3.

Introducing amide functionality at the targeted site within the structure results in compounds that can undergo spontaneous or enzyme mediated degradation, consequently mitigating their adverse environmental impact and reducing the likelihood of resistance development. Despite demonstrating their potential susceptibility to protease cleavage, the antimicrobial activity of these candidates proved to be lower than initially anticipated. Thus, our findings suggested that careful consideration of substituents at this position of quinuclidine backbone might yield derivatives that hold promise in overcoming antimicrobial resistance, improving biodegradability, and reducing toxicity relative to traditional QACs28.

Inspired by results of these studies and driven by the further pursuit for biologically potent 3-substituted quinuclidine QACs, here we synthesized quaternary salts of 3- dodecylaminoquinuclidine with benzyl substituents at the quaternary center to acquire further insights that can aid the development of novel antimicrobial agents with enhanced efficacy and safety profiles.

Results and discussion

Synthesis

Previous investigations have shown that introducing an amide group into the structure of QACs can provide new functionalities, such as biodegradability, but can also negatively impact antibacterial activity. These compounds, while gaining desired properties, often exhibit reduced effectiveness as antimicrobial agents28,29. Wuest and coworkers have explored the role of multiple positive charges in QACs, finding that compounds with more than one positive nitrogen atom exhibit better antimicrobial activities and are less prone to intrinsic resistance mechanisms2,30,31. This enhanced activity is likely due to the additional positive charge, which strengthens electrostatic interactions with the negatively charged groups on bacterial membranes. The increased positive charge may reduce the likelihood of these compounds being recognized and neutralized by bacterial resistance elements, thereby enhancing their effectiveness as antimicrobial agents.

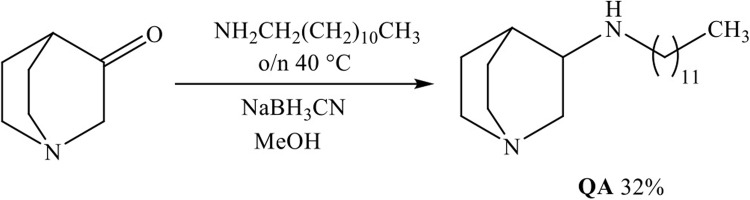

To mitigate the negative effects of the amide group, we synthesized 3-aminoquinuclidine (QA) with a dodecyl chain attached to the nitrogen atom of the amino group at the C-3 position of the quinuclidine ring. These compounds contain amine functionality, which under physiological conditions can bear an additional positive charge, similar to QACs with multiple positive nitrogen centers. QA was prepared through the reductive amination of commercially available quinuclidine-3-one with dodecyl amine, as shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2.

Preparation of QA.

Understanding that the choice of the quaternizing agent is crucial for determining the bioactivity of QACs5, it is also essential to consider other factors that contribute to their effectiveness. One such factor is maintaining an optimal hydrophilic-hydrophobic balance32, which has been consistently observed as vital for the bioactivity of these compounds. Increased hydrophobicity, for instance, can significantly enhance the interaction between QACs and lipid membranes during the later stages of membrane penetration, thereby improving the antibacterial effect33 but can also diminish water solubility.

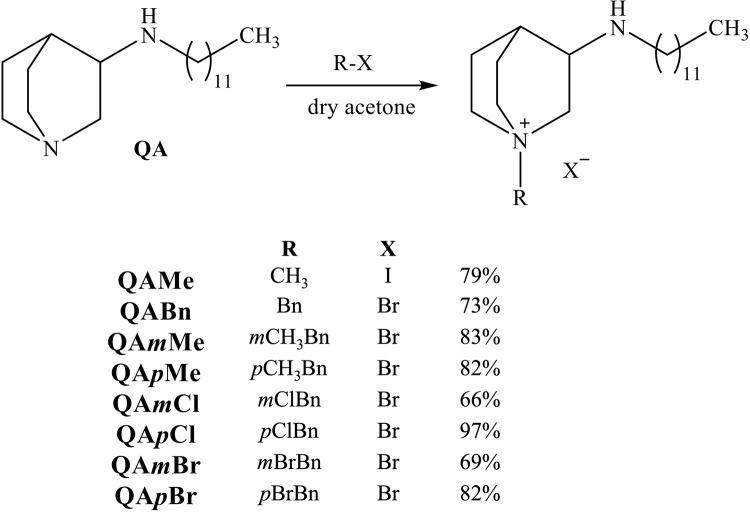

The approach that implements these findings, e.g. more positive centers and an optimal hydrophilic-hydrophobic balance, has the potential to yield compounds with potent antimicrobial efficacy and less susceptibility to resistance mechanisms, providing a promising path for the development of new antimicrobials. For this reason, quaternary products of QA were synthesized using methyl iodide, benzyl bromide or differently para- and meta- substituted benzyl bromides. The reactions were carried out in dry acetone under inert atmosphere as shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3.

Preparation and structures of N-substituted quaternary QA derivatives.

The prepared QA and its eight quaternary derivatives are compounds which have not been described in the literature so far. They were synthesized in moderate to good yields and their structures were determined by 1D and 2D NMR and HRMS analyses (Supporting information).

Antibacterial activity

Minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs)

The antibacterial activity of 3-substituted aminoquinuclidine salts was investigated by determining the minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) on representative Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. These values were compared with the MICs of commercially available standard QACs, cetylpyridinium chloride (CPC) and benzododecinium bromide (BAB), as well as the precursor QA, which served as a non-quaternized control.

As shown in Table 1, the non-quaternized control showed no relevant antibacterial activity compared to the QACs, demonstrating that rational quaternization is indeed a powerful tool to obtain potent antibacterial agents34. However, the choice of quaternizing agent significantly impacts bioactivity. For example, the QAMe compound, which features simple methylation, did not reach the full antibacterial potential observed with QABn. This indicates that more robust and hydrophobic quaternizing agents may be required to achieve optimal antibacterial efficacy.

Table 1.

Minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs/ M) of antimicrobial agents against the panel of selected bacteria.

M) of antimicrobial agents against the panel of selected bacteria.

Minimal inhibitory concentrations (

| |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gram-positive bacteria | Gram-negative bacteria | ||||||||

| Compound | Staphylococcus aureus ATCC25923 | Staphylococcus aureus ATCC33591 | MRSA Clinical isolate | Bacillus cereus ATCC14579 | Listeria monocytogenes ATCC7644 | Enterococcus faecalis ATCC29212 | Escherichia coli ATCC25922 |

Salmonella enterica

Food isolate |

Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC27853 |

| QA | 63 | 63 | 31 | 31 | 31 | 31 | 63 | 31 | > 125 |

| QAMe | 16 | 31 | 63 | 31 | 63 | 125 | 63 | 63 | > 125 |

| QABn | 8 | 8 | 8 | 31 | 8 | 4 | 16 | 16 | 125 |

| QA m Me | 2 | 4 | 4 | 16 | 4 | 2 | 8 | 8 | 63 |

| QA p Me | 4 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 8 | 8 | 63 |

| QA m Cl | 2 | 4 | 4 | 16 | 4 | 2 | 8 | 8 | 63 |

| QA p Cl | 4 | 2 | 4 | 16 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 31 |

| QA m Br | 8 | 4 | 4 | 16 | 4 | 2 | 8 | 8 | 31 |

| QA p Br | 2 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 31 |

| Commercial QACs | |||||||||

| CPC | 4 | 6 | 8 | 16 | 8 | 8 | 16 | 63 | 250 |

| BAB | 10 | 25 | 25 | 13 | 10 | 15 | 63 | 50 | > 125 |

Nevertheless, we must consider QAMe (MICs ≥ 16 µM) alongside two structurally similar QACs, which showed minimal activity against Staphylococcus aureus with MICs ≥ 100 µM26,28. One of these analogues carries amino group in the C-3 position and long alkyl chains in the quaternary center, the other is functionalized with a non-polar dodecyl chain in continuation of the amide group at the C-3 position and methyl or allyl substituent at the quaternary center (Fig. 1). It seems that a sole amino group at C-3 position is insufficient to obtain fully bioactive structure instead a non-polar functionality in the continuation of the amino group seems to be required. Taken together, these structure-activity insights indicate the importance of the functional group and the correct hydrophilic-hydrophobic balance at the C-3 position for efficacy. Besides having the optimal hydrophilic-hydrophobic balance, the amino functional group in QAMe can further enhance the antibacterial properties due to its ionization state, which is similar to the double positive charge of bisQACs under measurement conditions. Therefore, it can be hypothesized that, among other known structural determinants, the functionality at the C-3 atom of the quinuclidine backbone is indeed an important point that requires special attention in the development of future QACs.

On the contrary, benzylated derivatives, featuring a highly hydrophobic benzyl ring at the quaternary center, displayed robust antibacterial activity, often achieving single-digit micromolar values (Table 1). These broad-spectrum activities were either much better or equivalent to conventional BAB or CPC, thus underlining the antibacterial potential of the new candidates. Notably, QABn exhibited higher MICs compared to derivatives with a halogen atom or a methyl group in the para- or meta- position on the benzyl ring, suggesting that the substituents on the benzyl ring and their position also play a role in enhancing antibacterial activity. For example, QApCl and QApBr demonstrated particularly potent activities against Gram-negative Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica, with MICs of 4 and 8 µM, respectively. Similar results were observed with 3-hydroxyiminoquinuclidine QACs bearing a benzyl ring at the quaternary center and chloride or bromide substituents at the meta and para positions24. These derivatives, despite lacking long alkyl chains, exhibited potent activity against S. aureus and E. coli, also achieving single-digit MIC values. The role of electron-donating elements on the benzyl ring might be responsible for increased activities. This is supported by earlier reports from Ali et al., where derivatives with 2,6-dichloro and 2-methoxy substituents on the phenyl ring showed excellent antimicrobial and wound healing properties35.

To explore their antimicrobial potential against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), which is known to harbor qac resistance genes, this collection of QACs was tested against clinically isolated and hospital-acquired HA-MRSA strains (ATTC33591) (Table 1). Based on the determined MICs, QApCl and QApBr once again exhibited compelling activity, underscoring the importance of para- position substitution. These findings suggest that para-substituted derivatives could be particularly effective in overcoming resistance mechanisms in MRSA, making them promising candidates for further development in the fight against antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections.

Given the potent activities of QApCl and QApBr against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, they were selected for a more comprehensive investigation of their antibacterial potential and mechanism of action.

Potential for resistance development

The possibility of developing resistance, especially to quaternary ammonium compounds (QACs), is a major challenge in microbiology and public health16. Resistance to these compounds primarily arises from the plasma efflux system encoded by qac genes, which relies on the cellular ATP pool’s availability. Consequently, reduced minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) under conditions of limited ATP supply suggest that the tested QACs may act as substrates for the efflux system36.

To further evaluate the potential of QApCl and QApBr to induce bacterial resistance, we assessed their MICs against Staphylococcus aureus ATCC33591, a known carrier of qac resistance genes, in the presence of the protonophore carbonyl cyanide-3-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP). Previous research has demonstrated that CCCP, at concentrations below the MIC, can indeed diminish the efflux activity of S. aureus ATCC33591 by reducing the cellular ATP level37. Therefore, evaluating MICs in the presence of CCCP may offer valuable insights into whether synthesized QACs act as substrates for Qac efflux pumps and the extent to which they contribute to bacterial resistance.

Table 2 illustrates the determined minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) for QApCl and QApBr in the presence and absence of CCCP. Interestingly, the MICs remained unchanged regardless of the presence of CCCP, indicating that these compounds did not exhibit a reduction in MICs. This observation suggests that QApCl and QApBr may not trigger known resistance mechanisms associated with efflux system.

Table 2.

Minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs/ M) of candidate compounds QApCl and QApBr against Staphylococcus aureus ATCC33591 in Mueller Hinton broth without (black) and in the presence (red) of carbonyl cyanide-3-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP).

M) of candidate compounds QApCl and QApBr against Staphylococcus aureus ATCC33591 in Mueller Hinton broth without (black) and in the presence (red) of carbonyl cyanide-3-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP).

Furthermore, the lack of change in MIC values in the presence of CCCP implies that these compounds are not substrates for the efflux pumps affected by ATP depletion induced by CCCP. This finding is significant as it suggests that QApCl and QApBr may exert their antibacterial activity through mechanisms independent of QAC efflux pumps and different from commercial BAB or CPC which both exhibit 32 and 16×MICs reduction during the CCCP treatment28. Additionally, this finding highlights the potential of these compounds as promising antimicrobial agents that are less susceptible to resistance development through known efflux mechanisms.

Minimal biofilm inhibition concentrations (MBICs)

Bacterial biofilms consist of individual bacteria embedded in extracellular polymeric substances (EPS). Due to the genetic diversity within biofilm populations and the protective role of EPS, bacteria in biofilms exhibit heightened resistance to antibacterial agents38. Notably, many human pathogens responsible for healthcare-associated infections, posing severe threats to human health through colonization of wounds and medical devices, are known for their ability to form biofilms39. Consequently, there is considerable interest among scientists in developing novel antibacterial agents with potent antibiofilm activities.

The antibiofilm activity of QACs has been extensively documented, expanding their application to long-term antimicrobial materials and coatings40. Two mechanisms have been proposed: firstly, QACs inhibit bacterial adhesion to surfaces, thus suppressing biofilm formation; secondly, QACs actively eradicate bacteria within biofilms.

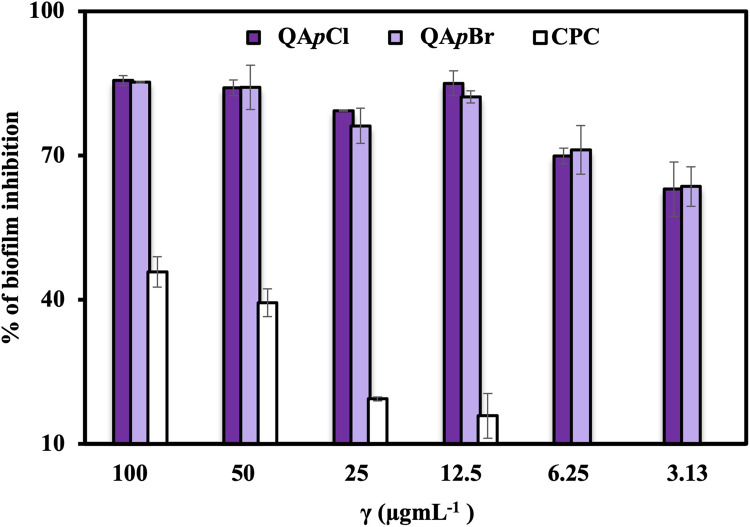

The minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs) demonstrated the potent antibacterial activity of two candidates, QApCl and QApBr. Consequently, we investigated their antibiofilm activity against Staphylococcus aureus ATCC25923 in comparison to conventional CPC. The S. aureus was chosen due to documented cases of persistent S. aureus biofilm infections associated with high mortality rates41. Figure 4 clearly demonstrates the greater ability of QApCl and QApBr to suppress the formation of bacterial biofilms compared to commercial QAC.

Figure 4.

The percentage (%) of Staphylococcus aureus ATCC25923 biofilm inhibition in relation to mass concentration ( g mL−1) of the antibacterial agents: QApCl, QApBr and CPC.

g mL−1) of the antibacterial agents: QApCl, QApBr and CPC.

These candidates effectively inhibited biofilm formation across all tested concentrations, ranging from 3.13 to 100 µg mL−1, with inhibition percentages exceeding 70%. Remarkably, they exhibited pronounced inhibition at the two lowest concentrations, where CPC showed no activity. This finding is particularly noteworthy considering that CPC is typically recognized as a potent antibacterial agent, often used in mouthwash solutions to eradicate and inhibit Streptococcus mutans, the primary bacteria responsible for cavities41,42. Streptococcus mutans forms intricate and multidimensional structures on oral mucosa and tooth enamel, contributing to cavity development43. Taken together, these findings underscore the potential of new compounds as potent alternatives to existing antibacterial agents, particularly in applications requiring effective biofilm inhibition.

Bacterial growth kinetic analysis

Bacterial growth kinetic analysis elucidates how bacterial populations evolve over time under specific conditions, influenced by factors such as temperature, pH, oxygen levels, nutrient availability, and the presence of inhibitory substances like antibiotics or toxins44. When subjected to an antibacterial agent, the growth curve deviates from the standard pattern, notably in comparison to the untreated control. Typically, the discrepancy between the curves is observed during the lag phase, wherein bacterial growth may be delayed or halted as bacteria adapt to the antibacterial agent45. Subsequently, during the exponential phase, the antibacterial agent often induces a reduction in the rate of bacterial growth compared to the untreated control. Instead of the anticipated rapid and exponential growth, the bacterial population may exhibit slower growth or even remain relatively constant as the antibacterial agent continues to exert its inhibitory effects.

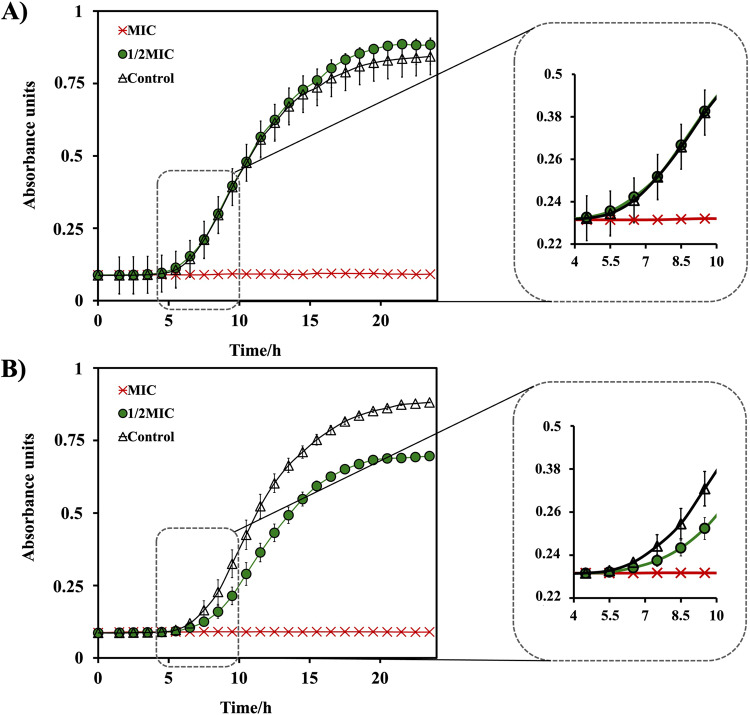

Considering the role of the bacterial growth curves in evaluating the effectiveness of antibacterial agents within defined measurement conditions, our study aimed to explore potential variations in bacterial growth curves when treated with QApCl and QApBr. The findings depicted in Fig. 5 distinctly illustrate the contrasting growth curves observed in the presence of the antibacterial agents. Notably, as the growth curves span a 24-hour incubation period, it becomes apparent that both agents effectively suppress bacterial growth at their respective MICs. However, intriguingly, at half the MIC concentration, QApBr demonstrates a notable reduction in bacterial growth compared to QApCl. This observation suggests a differential impact of the two agents on bacterial proliferation, emphasizing the importance of further investigation into their antibacterial mechanisms and potency.

Figure 5.

Time-resolved growth curves of Escherichia coli ATCC25922 during a 24-hour exposure to (A) QApCl and (B) QApBr, respectively. The inserts in the graphs provide enhanced resolution of the growth curves at MIC and ½ MIC, clearly depicting a halt in bacterial growth at ½ MIC for QApBr.

Cytotoxicity

The drawback of quaternary ammonium compounds (QACs) lies in their toxicity, which restricts their widespread use and application. Consequently, recent attention in the scientific community has shifted towards the development of environmentally friendly variants that exhibit easy degradation and lower toxicity towards both terrestrial and aquatic organisms2,28,46,47. Given the common utilization of QACs as disinfectants and antiseptics, ensuring their safety for potential use in humans and animals is paramount.

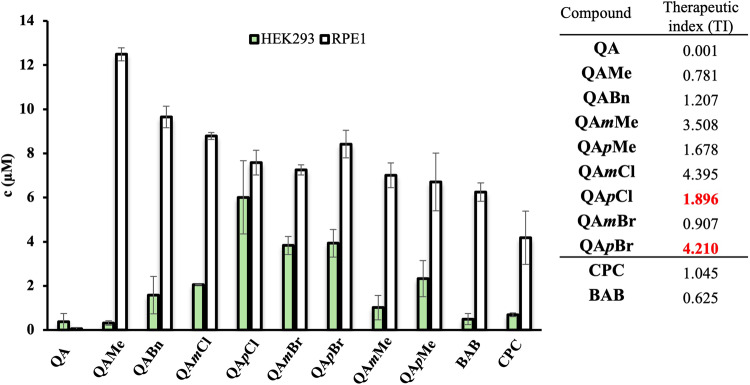

Hence, we determined the cytotoxicity of all newly synthesized QACs using healthy cell lines, human embryonic kidney (HEK293) and retinal pigment epithelial cells (RPE1), respectively. We further compared obtained IC50 with MICs for Gram-positive representative, namely Staphylococcus aureus ATCC25923 to obtain therapeutic index which provides insight into the safety of our compounds as potential therapeutic agents. The candidates expressing IC50 higher than the corresponding MIC were declared to be the least toxic for healthy cells and potentially safe for selected application. The resultant IC50 values, illustrated in Fig. 6, reveal distinct toxicity profiles for all QACs.

Figure 6.

The toxicity of quaternary 3-aminoquinuclidine salts expressed as concentration ( M) at which 50% of HEK293 and RPE1 cells are dead (IC50). The obtained therapeutic indices (TI) are presented in corresponding table and were calculated as ratio of IC50 value towards RPE1 reference cell line and MIC determined for Staphylococcus aureus ATCC25923.

M) at which 50% of HEK293 and RPE1 cells are dead (IC50). The obtained therapeutic indices (TI) are presented in corresponding table and were calculated as ratio of IC50 value towards RPE1 reference cell line and MIC determined for Staphylococcus aureus ATCC25923.

We can also observe different selectivity of QACs against two human cell lines. Specifically, HEK293 cells are generally more sensitive to all QACs evidenced by low IC50 values. On the other side, RPE1 cells display higher resistance to QACs, and given their epithelial origin and resemblance to keratinocytes, RPE1 could be taken as a reference cell line. Higher therapeutic indices of selected QACs in contrast to commercial standard, CPC, suggest their higher safety, with QApBr recognized as more prominent candidate compound.

Taken together, these findings are reassuring and support the potential application of QApCl and QApBr as ingredients in topical solutions, disinfectants, and antiseptics, given their selective toxicity profiles and efficacy. We have to note the strong therapeutic index of QAmCl which was expected given its higher IC50 value compared to MIC. However, QAmCl was not considered as candidate due to its diminished antibacterial potential.

Mode of antibacterial action

Atomic force and scanning electron microscopies

The antibacterial mechanism of QACs is primarily based on their membranolytic properties leading to the disruption of the bacterial cell envelope and subsequent cell lysis7,48. Gram-positive bacteria protect their cell contents with a membrane covered by a thick layer of peptidoglycan, whereas Gram-negative bacteria have an additional outer membrane that restricts the access of QACs to their target site. This difference explains the increased efficacy of QACs against Gram-positive bacterial strains.

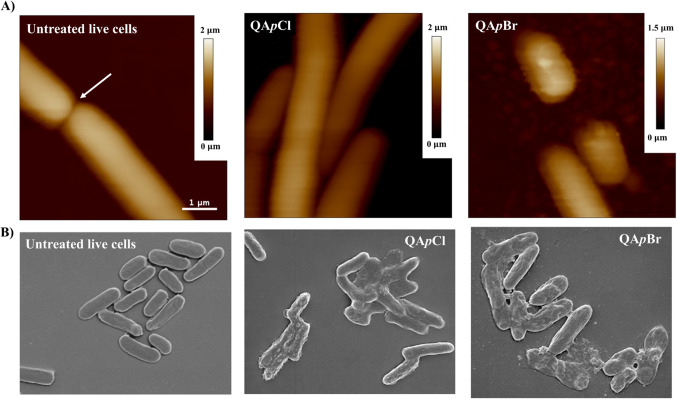

Motivated by the previously demonstrated antibacterial efficacy of the QAC candidates, QApCl and QApBr, against a panel of both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, we wanted to further investigate their mode of action against most common representative bacterial pathogens. Atomic force microscopy (AFM) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) were used to evaluate the morphological changes of Escherichia coli after the treatment with selected QACs in comparison to untreated cells (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Panel A: Height atomic force microscopy images before and after three-hour long treatment of Escherichia coli DH5α cells - untreated viable E. coli DH5α cells upon division (white arrow), E. coli DH5α cells after treatment with a 4 MIC concentration of QApCl and E. coli DH5α cells after treatment with a 4

MIC concentration of QApCl and E. coli DH5α cells after treatment with a 4 MIC concentration of QApBr. Scale bar for all AFM data is given in the first image. Panel B: Scanning electron microscopy data – untreated E. coli DH5α cells, cells treated with 16

MIC concentration of QApBr. Scale bar for all AFM data is given in the first image. Panel B: Scanning electron microscopy data – untreated E. coli DH5α cells, cells treated with 16 MIC concentration of QApCl and 8

MIC concentration of QApCl and 8 MIC concentration of QApBr. Scalebar corresponding to 1 μm is given below each image.

MIC concentration of QApBr. Scalebar corresponding to 1 μm is given below each image.

The strain selected for measurements was E. coli DH5α, due to its ability to be immobilized without compromising the cell viability. The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) for both compounds was determined prior to microscopy measurements and was found to be consistent with the values observed for E. coli ATCC25922, namely 8 µM for QApCl and 4 µM for QApBr. Height AFM image of untreated, viable E. coli DH5α in their characteristic rod shape with smooth, intact surfaces indicative of division (white arrow) is shown on panel A (Fig. 7).

Once the viability of the immobilized bacteria was confirmed, the cells were exposed to a 4×MIC concentration of the candidate compounds for three hours to accelerate the time-dependent membrane disruption. Interestingly, height AFM images of treated cells pointed out different extent of damage depending on candidate compound (panel A, Fig. 7). Cells treated with 4×MIC concentration of QApCl were unable to proliferate as evidenced by cellular elongation, while the cell surface seemed preserved. In contrast, treatment with QApBr resulted in pronounced damage manifested by a roughened cell surface and loss of characteristic rod shape which led to increased adhesion between the sample and the AFM probe tip significantly aggravating the measurement.

In contrast to AFM measurements, the inspection of both untreated and treated cells using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) necessitates fixation and air drying49,50. Although these procedures can alter cell morphology, panel B in Fig. 7 illustrates significant differences between untreated E. coli DH5α cells and those treated with candidate QACs. Despite the potential morphological alterations due to sample preparation, the untreated cells exhibit their characteristic morphology. Conversely, the presence of membrane bulges in the treated cells confirms the membranolytic activity of both selected compounds. Although both compounds act as membranolytic agents, QApBr demonstrates potent efficacy, causing more extensive cellular damage and complete membrane disruption, as evidenced by the leakage of intracellular contents observed on the sample surface.

Uptake of propidium iodide (PI)

Bacterial membrane damage upon treatment can also be evidenced by fluorescent labeling, most commonly using red fluorescent nuclear dye propidium iodide (PI). Due to its molecular size, PI cannot penetrate the intact cell membranes of viable cells. It therefore serves as a marker to distinguish cells with damaged membranes51.

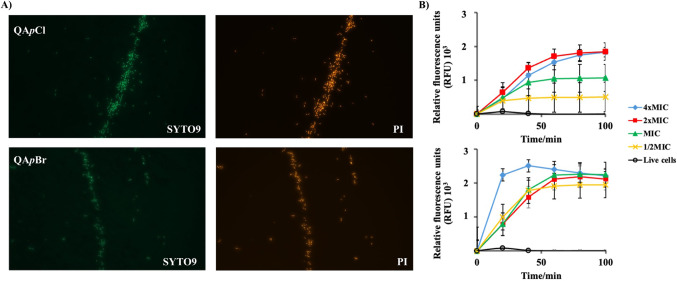

To further investigate membranolytic potency of candidate QACs, treated Escherichia coli DH5α cells were fluorescently labelled with a mixture of two fluorophores, SYTO9 and PI. When treated culture is simultaneously stained, SYTO9, unlike PI, penetrates all cells, regardless of their membrane integrity, and emits green fluorescent signal upon binding to the nucleic acid. Comparison of the optical fluorescence microscopy images provides information on the quantity of the bacterial cell population with the compromised cell membranes52.

Figure 8, panel A, shows the population of fluorescently labelled E. coli DH5α cells after exposure to 4×MIC concentration of QApCl and QApBr. While atomic force microscopy did not indicate severe membrane damage subsequent to QApCl treatment, the distribution of fluorescently PI and SYTO9 labelled cells was nearly identical for both candidates, suggesting their membranolytic mechanism of action. Given the low single-digit micromolar values exhibited by the candidate compounds against a representative Gram-negative bacterium, it is noteworthy that these compounds exhibit strong antibacterial activity. This is particularly interesting considering the composition of the cell envelope in Gram-negative strains.

Figure 8.

Panel A: Escherichia coli DH5α cells stained with the mixture of SYTO9 and propidium iodide (PI) nucleic fluorophores subsequent to exposure of 4×MIC concentration of QApCl and QApBr. Panel B: Spectrofluorimetric determination of propidium iodide (PI) uptake during the time of Staphylococcus aureus ATCC25923 treatment with different concentrations of selected candidate compounds QApCl (upper graph) and QApBr (lower graph).

The observed membranolytic activity of the QAC candidates against E. coli DH5α prompted us to investigate their efficacy against Staphylococcus aureus ATCC25923, a representative Gram-positive strain characterized by the absence of an outer membrane. Moreover, negatively charged teichoic acid anchored in the peptidoglycan matrix can interact electrostatically with the QAC backbone, facilitating their membranolytic effect.

To determine how selected QACs affect the S. aureus ATCC25923 membrane, we used different fluorescence-based techniques, namely spectrofluorimetric determination of propidium iodide (PI) uptake and temporal monitoring of treated culture by flow cytometry. Figure 8, panel B, depicts relative fluorescence units (RFU) of PI over six-hour long treatment of S. aureus ATCC25923 with different concentrations of QApCl and QApBr. The evaluation of PI fluorescence intensity for both the treated cells and the untreated control points out almost immediate membrane damage. In addition, QApBr was found to be more effective, as indicated by a continuously high PI fluorescence intensity for each concentration tested.

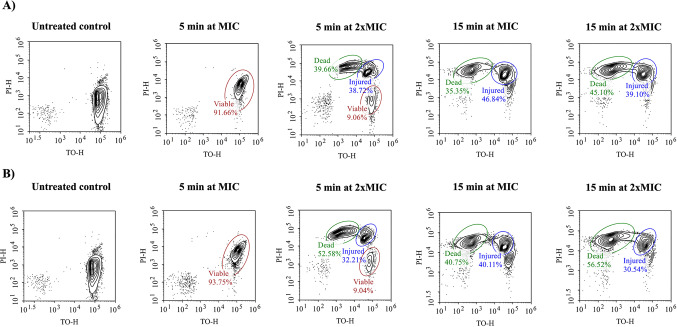

The treatment of S. aureus ATCC25923 with MIC and 2×MIC concentrations of QApCl and QApBr was further analyzed by flow cytometry. Given the previously indicated prompt membrane damage, these measurements were performed at shorter time intervals. Flow cytometric analysis showed that after only 15 min of treatment with MIC concentration of both candidates, no viable cells were present, while half of the bacterial population was dead (Fig. 9) which was consistent with spectrofluorimetric analysis.

Figure 9.

Time-dependent flow cytometry detection of live and dead Staphylococcus aureus ATCC25923 bacterial cells upon the treatment with the antibacterial agents (A) QApCl and (B) QApBr at MIC and 2×MIC concentrations.

The investigation of the antibacterial mode of action of QApCl and QApBr highlights their potential to combat both Gram-positive and Gram-negative pathogenic bacteria. At the same time, their lower toxicity to human cells and reduced potential to trigger bacterial resistance mechanisms points out these compounds as promising new antibacterial agents.

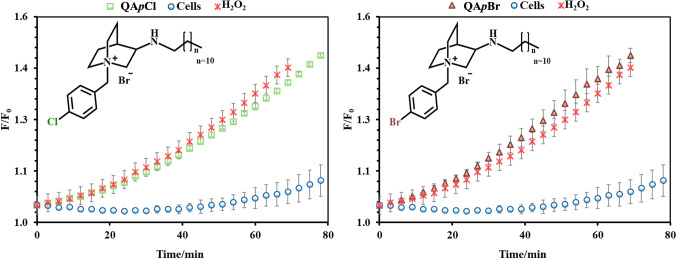

Generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS)

A promising strategy to eradicate bacteria while simultaneously targeting multiple crucial bacterial pathways involves the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS)53. Previous studies have demonstrated that exposure to quaternary ammonium compounds (QACs) can induce ROS production by inhibiting key bacterial enzymes. Notably, enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (CAT), which play vital roles in scavenging ROS, are inhibited by QACs during treatment. This inhibition is more pronounced with longer alkyl chains in QACs, resulting in increased ROS generation54. The ROS accumulation triggered by QACs can cause extensive damage to cellular components, potentially leading to apoptosis and cell death55.

Led by these investigations, we aimed to assess ROS generation resulting from QApCl and QApBr treatments, comparing these results to the background ROS levels produced by untreated live cells and hydrogen peroxide as a positive control (Fig. 10). Notably, all treatments led to high ROS production, eventually saturating the instrument’s detector. However, differences between the candidates are apparent and consistently demonstrate distinct profiles. Although both compounds induce ROS generation, the extent of ROS production varies between them. Specifically, QApCl treatment results in lower ROS generation compared to QApBr and the hydrogen peroxide control. For example, ROS production from QApCl continues beyond the 80-minute exposure time, while ROS production from hydrogen peroxide and QApBr ceases around 70 min due to detector saturation.

Figure 10.

The generation of reactive oxygen speces (ROS) upon treatment with QApCl and QApBr. The results are compared with untreated live cells and cells treated with hydrogen peroxide control.

These findings may explain the stronger antibacterial activity of QApBr, suggesting an additional mechanism of action that induces faster bacterial death due to higher toxicity. This indicates that QApBr could be more effective in situations requiring stronger oxidative stress to eliminate resilient bacterial strains.

In conclusion, the comparative analysis of ROS generation by QApCl and QApBr enhances our understanding of their bioactive profiles, guiding their appropriate application in antimicrobial strategies. Further research is warranted to explore the underlying mechanisms driving these differences and to optimize the use of these compounds in various clinical and environmental settings.

Materials and methods

Synthesis

General notes

Reagents and solvents for the preparation of compounds were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), Fluka. The reactions were monitored by thin-layer chromatography plates coated with aluminum oxide (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). TLC plates were visualized by UV irradiation (254 nm) or by iodine fumes. 1D and 2D 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Avance Neo 600 MHz/54 mm Ascend spectrometer equipped with a 5 mm inverse TCI Prodigy cryoprobe (Bruker Optics Inc, Billerica, MA, USA). Chemical shifts are given in ppm downfield from tetramethyl silane (TMS) as an internal standard and coupling constants (J) in Hz. Splitting patterns are designated as s (singlet), d (doublet), ddd (doublet of doublet of doublets), t (triplet), dt (doublet of triplets) or m (multiplet). Dodecyl hydrogen and carbon atoms are marked with an apostrophe. Benzyl hydrogen and carbon atoms are marked with an asterisk. Melting points were determined on a Melting Point B-540 apparatus (Büchi, Essen, Germany) and are uncorrected. HPLC analyses were performed on Agilent 1260 series instrument equipped with a quaternary pump, autosampler, column compartment and diode array detector (DAD). HPLC conditions: Zorbax Eclipse C18 column, 4.6 × 250 mm, 5 μm pore size; column temperature 25 °C; flow rate 1.0 mL/min; mobile phase A: 0.1% phosphoric acid, mobile phase B: CH3CN; 10/90/90/10/10% B in time intervals 0/10/15/20/25; the volume of injection 10 µL; UV detection at 220 nm. All prepared compounds have purity > 95%. HRMS analyses were carried out on Q Exactive™ Plus Hybrid Quadrupole-Orbitrap™ Mass Spectrometer.

Synthesis of 3-aminododecylquinuclidine QA

Quiniclidin-3-one (1 mmol), sodium cyanoborohydride (1.4 mmol) and dodecyl amine (1 mmol) were mixed in methanol overnight at 40 °C. Solvent was evaporated, residue made alkaline with 1 M NaOH and transferred in separation funnel. After extraction with chloroform, organic extracts were dried over anhydrous sodium sulphate, filtered and evaporated. Residue was purified with column chromatography (aluminum oxide, CHCl3:MeOH = 9:1) to acquire oily product.

3-aminododecylquinuclidine, QA, Yield: 32%. (Supporting information, S1-2, S19)

1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ/ppm: 0.88 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3 H, H12’) 1.21–1.37 (m, 19 H, H3’-H11’, H5b) 1.43–1.51 (m, 3 H, H2’, H7b) 1.63–1.71 (m, 1 H, H7a) 1.78–1.84 (m, 2 H, H5a, H4) 2.39 (ddd, J = 13.6, 4.8, 2.3 Hz, 1 H, H2b) 2.48–2.61 (m, 2 H, H6b, H8a) 2.68–2.92 (m, 5 H, H1’, H3, H6a, H8b) 3.13 (ddd, J = 13.2, 8.8, 2.2 Hz, 1 H, H2a); 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) δ/ppm: 14.12 (C12’) 20.01 (C5) 22.65; 25.15 (C4); 26.37 (C7); 27.46; 29.32; 29.55; 29.59; 29.64; 30.46 (C2’); 31.90; 47.10 (C1’) 47.68 (C8) 47.72 (C6) 55.22 (C3) 57.07 (C2); HRMS (Electrospray ionisation (ESI) m/z calcd for C19H39N2+ = 295.3108, found 295.3106.

General procedure for synthesis of quaternary compounds

N-dodecyl-3-amino-quinuclidine (1 mmol) was mixed with methyl iodide (1 mmol) or appropriate benzyl bromide (1 mmol) in dry acetone under nitrogen atmosphere. Reaction was monitored with thin-layer chromatography. Crude product was filtered off and washed extensively with diethyl ether.

3-dodecylamino-1-methylquinuclidinium iodide, QAMe, Yield: 79%, mp 110.8–111.5 °C. (Supporting information, S3-4, S20, S28)

1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ/ppm: 0.88 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3 H, H12’) 1.22–1.35 (m, 18 H, H3’-H11’) 1.43–1.50 (m, 2 H, H2’) 1.86–1.95 (m, 1 H, H5b) 1.98–2.07 (m, 1H, H7a) 2.09–2.18 (m, 1 H, H7b) 2.24–2.26 (m, 1 H, H4) 2.27–2.36 (m, 1 H, H5a) 2.47–2.57 (m, 2 H, H1’) 3.11 (dt, J = 12.5, 2.9 Hz, 1 H, H2b) 3.26–3.29 (m, 1 H, H3) 3.32 (s, 3 H, N-CH3) 3.52–3.59 (m, 1 H, H6b) 3.75–3.93 (m, 3 H, H8a, H6b, H8b) 4.15 (ddd, J = 12.3, 8.9, 2.9 Hz, 1 H, H3); 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) δ/ppm: 14.03 (C12’) 18.50 (C5) 22.61, 22.85 (C7) 23.82 (C4) 27.30, 29.28, 29.48, 29.55, 29.57, 29.60, 30.13 (C2’) 31.86, 47.40 (C1’) 52.60 (C3) 52.80 (CH3) 56.47 (C8) 57.82 (C6) 64.73 (C2); HRMS (Electrospray ionisation (ESI) m/z calcd for C20H41N2+ = 309.3264, found 309.3261.

3-dodecylamino-1-benzylquinuclidinium bromide, QABn, Yield: 73%, mp 70.2–70.4 °C. (Supporting information, S5-6, S21, S29)

1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) d/ppm: 0.88 (t, J = 6.7 Hz, 3 H, H12’) 1.20–1.33 (m, 18 H, H3’-H11’) 1.39–1.48 (m, 2 H, H2’) 1.74–1.83 (m, 1 H, H5b) 1.91–2.02 (m, 1 H, H7a) 2.02–2.09 (m, 1 H, H7b) 2.19–2.21 (m, 1 H, H4) 2.22–2.28 (m, 1 H, H5a) 2.43–2.54 (m, 2 H, H1’) 3.14–3.18 (m, 1 H, H2b) 3.22–3.28 (m, 1 H, H3) 3.51–3.58 (m, 1 H, H6b) 3.70–3.79 (m, 2 H, H8a, H6b) 3.93-4.00 (m, 1 H, H8b) 4.21 (ddd, J = 12.29, 8.99, 2.93 Hz, 1 H, H2a) 4.92 (d, J = 13.21 Hz, 1 H, CH2a) 4.99 (d, J = 13.20 Hz, 1 H, CH2b) 7.38–7.46 (m, 3 H, H2*, H4*, H6*) 7.63 (d, J = 6.60 Hz, 2 H, H3*, H5*); 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) d/ppm: 14.03 (C12’) 18.45 (C5) 22.62, 22.91 (C7), 24.64 (C4) 27.24, 29.28, 29.41, 29.52, 29.55, 29.57, 29.59, 29.87 (C2’) 31.86, 47.41 (C1’) 52.95 (C3) 53.86 (C8) 54.14 (C6) 61.11 (C2) 67.04 (CH2) 126.95 (C1*) 129.13 (C3*; C5*) 130.46 (C4*) 133.31 (C2*; C6*); HRMS (Electrospray ionisation (ESI) m/z calcd for C26H45N2+ = 385.3577, found 385.3572.

3-dodecylamino-1-(3-methylbenzyl)quinuclidinium bromide, QAmMe, Yield: 83%, mp 145.6–146.2 °C. (Supporting information, S7-8, S22, S30)

1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) d/ppm: 0.88 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3 H, H12’) 1.16–1.34 (m, 18 H, H3’-H11’) 1.37–1.45 (m, 2 H, H2’) 1.72–1.86 (m, 1 H, H5a) 1.89–2.12 (m, 2 H, H7) 2.12–2.30 (m, 2 H, H4, H5b) 2.31–2.40 (m, 3 H, CH3) 2.40–2.54 (m, 2 H, H1’) 3.09 (dt, J = 12.3, 3.1 Hz, 1 H, H2a) 3.16–3.26 (m, 1 H, H3) 3.44–3.57 (m, 1 H, H6a) 3.67–3.84 (m, 2 H, H6b, H8a) 3.92–4.06 (m, 1 H, H8b) 4.15–4.29 (m, 1 H, H2b) 4.80–4.98 (m, 2 H, CH2) 7.21–7.32 (m, 2 H, H4*, H6*) 7.36–7.43 (m, 2 H, H2*, H5*); 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) d/ppm: 14.07 (C12’) 18.40 (C5) 21.27 (CH3) 22.63, 22.87 (C7) 24.65 (C4) 27.26, 29.30, 29.43, 29.53, 29.57, 29.58, 29.61, 30.05 (C2’) 31.86 47.40 (C1’) 52.89 (C3) 53.83 (C6) 54.09 (C8) 61.33 (C2) 67.15 (CH2) 126.78 (C1*) 128.97 (C4*) 130.38 (C6*) 131.22 (C5*) 133.69 (C2*) 139.03 (C3*); HRMS (Electrospray ionisation (ESI) m/z calcd for C27H47N2Br+ = 399.3734, found 399.3732.

3-dodecylamino-1-(4-methylbenzyl)quinuclidinium bromide, QApMe, Yield: 82%, mp 128.6–129.1 °C. (Supporting information, S9-10, S23, S31)

1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) d/ppm: 0.83–0.95 (m, 3 H, H12’) 1.13–1.28 (m, 18 H, H3’-H11’) 1.36–1.39 (m, 1 H, H2’) 1.70–1.79 (m, 1 H, H5a) 1.87–2.11 (m, 2 H, H7) 2.12–2.30 (m, 2 H, H4, H5b) 2.37 (s, 3 H, CH3) 2.40–2.58 (m, 2 H, H1’) 3.01–3.06 (m, 1 H, H2a) 3.15–3.25 (m, 1 H, H3) 3.41–3.50 (m, 1 H, H8a) 3.65–3.82 (m, 2 H, H6a, H8b) 3.89–4.02 (m, 1 H, H8a) 4.11–4.28 (m, 1 H, H2b) 4.82–4.99 (m, 2 H, CH2) 7.21 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 2 H, H3*, H5*) 7.50 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 2 H, H2*, H6*); 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) d/ppm: 14.07 (C12’) 18.38 (C5) 21.25 (CH3) 22.63, 22.87 (C7) 24.70 (C4) 27.25, 29.29, 29.43, 29.52, 29.56, 29.57, 29.60, 30.05 (C2’) 31.86, 47.38 (C1’) 52.87 (C3) 53.71 (C6) 53.93 (C8) 61.20 (C2) 66.83 (CH2) 123.85 (C1*) 129.75 (C3*, C5*) 133.15 (C2*, C6*) 140.64 (C4*), HRMS (Electrospray ionisation (ESI) m/z calcd for C27H47N2Br+ = 399.3734, found 399.3731.

3-dodecylamino-1-(3-chlorobenzyl)quinuclidinium bromide, QAmCl, Yield: 66%, mp 129.2–130.1 °C. (Supporting information, S11-12, S24, S32)

1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) d/ppm: 0.88 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3 H, H12’) 1.24–1.31 (m, 18 H, H3’-H11’) 1.39–1.41 (m, 2 H, H2’) 1.75–1.84 (m, 1 H, H5b) 1.91-2.00 (m, 1 H, H7a) 2.03–2.11 (m, 1 H, H7b) 2.15–2.20 (m, 1 H, H4) 2.21–2.27 (m, 1 H, H5a) 2.39–2.53 (m, 2 H, H1’) 3.08–3.12 (m, 1 H, H2b) 3.17–3.24 (m, 1 H, H3) 3.48–3.56 (m, 1 H, H6b) 3.74–3.84 (m, 2 H, H8b, H6a) 3.94–4.02 (m, 1 H, H8b) 4.21 (ddd, J = 12.1, 9.2, 2.2 Hz, 1 H, H2a) 5.04 (d, J = 12.5 Hz, 1 H, CH2a) 5.10 (d, J = 13.2 Hz, 1 H, CH2b) 7.36 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 1 H, H6*) 7.41 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1 H, H4*) 7.60 (s, 1 H, H2*) 7.66 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 1 H, H5*); 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) d/ppm: 14.05 (C12’) 18.37 (C5) 22.63, 22.86 (C7) 24.59 (C4) 27.25, 29.28, 29.43, 29.52, 29.57, 29.60, 30.03 (C2’) 31.86, 47.39 (C1’) 52.86 (C3) 54.01 (C6) 54.15 (C8) 61.28 (C2) 65.72 (CH2) 129.03 (C1*) 130.45 (C4*) 130.68 (C6*) 131.79 (C2*) 132.81 (C5*) 134.95 (C3*); HRMS (Electrospray ionisation (ESI) m/z calcd for C26H44N2Cl+ = 419.3188, found 419.3184.

3-dodecylamino-1-(4-chlorobenzyl)quinuclidinium bromide, QApCl, Yield: 97%, mp 154.2–155.2 °C. (Supporting information, S13-14, S25, S33)

1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) d/ppm: 0.88 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3 H, H12’) 1.21–1.33 (m, 18 H, H3’-H11’) 1.37–1.42 (m, 2 H, H2’) 1.72–1.81 (m, 1 H, H5b) 1.90–1.98 (m, 1 H, H7a) 2.01–2.08 (m, 1 H, H7b) 2.15–2.17 (m, 1 H, H4) 2.20–2.24 (m, 1 H, H5a) 2.38–2.51 (m, 2 H, H1’) 3.06 (dt, J = 12.5, 2.9 Hz, 1 H, H2a) 3.16–3.21 (m, 1 H, H3) 3.43–3.51 (m, 1 H, H6b) 3.70–3.80 (m, 2 H, H8b, H6a) 3.90-4.00 (m, 1 H, H8a) 4.12–4.23 (m, 1 H, H2b) 5.03 (d, J = 13.2 Hz, 1 H, CH2a) 5.11 (d, J = 12.5 Hz, 1 H, CH2b) 7.37 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2 H, H2*, H6*) 7.63 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2 H, H3*, H5*); 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) d/ppm: 14.06 (C12’) 18.38 (C5) 22.64, 22.85 (C7) 24.67, 27.25, 29.30, 29.44, 29.53, 29.57, 29.59, 29.61, 30.02 (C2’) 31.86, 47.40 (C1’) 52.84 (C3) 53.89 (C6) 54.02 (C8) 61.22 (C2) 65.65 (CH2) 125.52 (C1*) 129.37 (C3*, C5*) 134.68 (C2*, C6*) 136.95 (C4*); HRMS (Electrospray ionisation (ESI) m/z calcd for C26H44N2Cl+ = 419.3188, found 419.3186.

3-dodecylamino-1-(3-bromobenzyl)quinuclidinium bromide, QAmBr, Yield: 69%, mp 142.8–143.4 °C. (Supporting information, S15-16, S26, S34)

1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) d/ppm: 0.88 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3 H, H12’) 1.14–1.34 (m, 18 H, H3’-H11’) 1.37–1.42 (m, 2 H, H2’) 1.74–1.86 (m, 1 H, H5b) 1.86–2.14 (m, 2 H, H7) 2.15–2.32 (m, 2 H, H4, H5a) 2.38–2.57 (m, 2 H, H1’) 3.07–3.13 (m, 1 H, H2a) 3.17–3.26 (m, 1 H, H3) 3.45–3.59 (m, 1 H, H6b) 3.70–3.88 (m, 2 H, H6a, H8b) 3.95–4.08 (m, 1 H, H8a) 4.17–4.32 (m, 1 H, H2b) 5.00-5.17 (m, 2 H, CH2) 7.28–7.32 (m, 1 H, H6*) 7.56–7.59 (m, 1 H, H5*) 7.70–7.79 (m, 2 H, H2*, H4*); 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) d/ppm: 14.07 (C12’) 18.36 (C5) 22.63, 22.85 (C7) 24.56, 27.25, 29.29, 29.43, 29.52, 29.57, 29.60, 30.02 (C2’) 31.86, 47.39 (C1’) 52.84 (C3) 53.97 (C6) 54.10 (C8) 61.24 (C2) 65.63 (CH2) 122.97 (C3*) 129.28 (C1*) 130.70 (C6*) 132.28 (C4*) 133.62 (C5*) 135.60 (C2*); HRMS (Electrospray ionisation (ESI) m/z calcd for C26H44N2Br+ = 463.2682, found 463.2680.

3-dodecylamino-1-(4-bromobenzyl)quinuclidinium bromide, QApBr, Yield: 82%, mp 133.8–134.7 °C. (Supporting information, S17-18, S27, S35)

1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) d/ppm: 0.88 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3 H, H12’) 1.14–1.34 (m, 18 H, H3’-H11’) 1.39–1.43 (m, 2 H, H2’) 1.72–1.82 (m, 1 H, H5b) 1.87–1.97 (m, 1 H, H7a) 1.99–2.08 (m, 1 H, H7b) 2.13–2.31 (m, 2 H, H4, H5a) 2.38–2.56 (m, 2 H, H1’) 3.07 (dt, J = 12.5, 3.0 Hz, 1 H, H2b) 3.15–3.22 (m, 1 H, H3) 3.43–3.53 (m, 1 H, H6b) 3.68–3.81 (m, 2 H, H6a; H8b) 3.86-4.00 (m, 1 H, H8a) 4.16 (ddd, J = 12.2, 8.9, 2.6 Hz, 1 H, H2b) 4.98–5.14 (m, 2 H, CH2) 7.50–7.54 (m, 2 H, H2*; H6*) 7.54–7.58 (m, 2 H, H3*; H5*); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) d/ppm: 14.07 (C12’) 18.35 (C5) 22.64, 22.83 (C7) 24.62 (C4) 27.24, 29.29, 29.43, 29.53, 29.57, 29.58, 29.61, 30.00 (C2’) 31.86, 47.38 (C1’) 52.82 (C3) 53.89 (C6) 53.98 (C8) 61.14 (C2) 65.62 (CH2) 125.24 (C4*) 125.99 (C1*) 132.32 (C2*; C6*) 134.90 (C3*; C5*); HRMS (Electrospray ionisation (ESI) m/z calcd for C26H44N2Br+ = 463.2682, found 463.2684.

Broth microdilution assay

The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of the newly synthesized quaternary 3-aminoquinuclidine compounds and the precursor of quaternization was tested on a panel of Gram-positive (Staphylococcus aureus ATCC25923, Staphylococcus aureus MRSA (clinical isolate), Staphylococcus aureus ATCC33591, Bacillus cereus ATCC14579, Listeria monocytogenes ATCC7644, Enterococcus faecalis ATCC29212) and Gram-negative (Escherichia coli ATCC25922, Salmonella enterica (food isolate), Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC27853) bacteria. The bacterial strains used for this study were obtained from BioGnost. The method for determining the MIC was performed according to the standardized protocol of the Clinical and Laboratory Standard Institute ref. The selected bacteria were grown overnight in Mueller-Hinton broth (MHB) at the desired optimal temperature for the tested strain. The next day, the culture was inoculated into fresh MHB and propagated further until the exponential growth phase was reached. The culture was then diluted again in MHB to a final concentration of 5 × 105 CFU/mL. An aliquot of 50 µL of the prepared bacterial cell culture was added to the wells of the 96-well plate containing twofold dilutions of the tested compounds in MHB (250 µM to 0.25 µM). After overnight incubation of the cells, the MIC values were visually determined as the lowest concentration that inhibited bacterial growth. Visual inspection of the MIC was verified with 2-(4-iodophenyl)-3-(4-nitrophenyl)-5-phenyltetrazolium chloride reagent (INT) (6 mg/mL), which turns purple in the presence of viable bacterial cells.

Biofilm inhibition assay

The efficacy of the selected QAC candidates in inhibiting bacterial biofilm formation was investigated using the representative Gram-positive bacterium Staphylococcus aureus ATCC25923. The overnight culture of the selected strain was diluted 10 times and further propagated in MHB. Once the culture reached the exponential growth phase, it was diluted to a final concentration of 5 × 106 CFU/mL and added to the wells of the previously prepared duplicates of 2-fold serial dilutions of the tested compounds (100 µg/mL to 3.25 µg/mL) in the wells of the 96-well plate. The minimum biofilm inhibitory concentrations (MBICs) were determined the following day using the crystal violet staining method. Briefly, MHB supernatant was aspirated from each analysed well and plates were dried in an incubator at 60 °C for 1 h. After the formed biofilm was immobilized, it was further incubated with 100 µL of 1% crystal violet (CV) solution at room temperature. After the stain was removed, wells were rinsed twice with sterile Milli-Q water. Residues of CV-stained biofilms were treated with 100 µL of 70% ethanol for 1 h at room temperature. If necessary, the contents of the wells were resuspended using the multichannel pipette prior to absorbance measurement. The absorbance of samples was measured using the ELx808 optical plate reader (Bio-Tek) at 595 nm. The results were expressed as a percentage of biofilm inhibition formation compared to the formed biofilm of the untreated control.

Time-resolved growth analysis

The effect of treatment with MIC and sub-MIC concentrations of the QAC candidates on the growth curve of the Escherichia coli ATCC25922 cell population was evaluated by in-time absorbance measurements for 24 h. Exponentially grown E. coli ATCC25922 population was diluted in MHB to the final concentration of 5 × 104 CFU/mL, upon which a 50 µL aliquot of prepared culture was added to the wells of the 96-well plate containing ½ MIC and MIC concentrations of the candidate compounds. Plates were incubated at 37 °C with constant shaking in the ELx808 optical reader (Bio-Tek). Optical density of tested samples was measured at intervals of 10 min for 24 h. Obtained growth curves of the cells in treatment were compared to the growth curve of untreated cells and represent the mean values of two independent experiments performed in triplicates.

Potential of bacterial resistance development

The potential of QAC candidates to activate bacterial resistance mechanisms was investigated by determining the MIC of selected compounds in the presence of carbonyl cyanide-3-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP) (Sigma Aldrich). CCCP acts as an inhibitor of ATP synthesis pathways and prevents the elimination of toxic compounds from the cell mediated by the efflux pump. The bacterial strain used for this purpose was Staphylococcus aureus ATCC33591 (MRSA), which contains genes coding for the expression of efflux pumps. The optimal CCCP concentration used in this experiment was determined based on the previously determined MIC of CCCP against the selected bacteria. An exponentially grown culture of S. aureus ATCC33591 was diluted in MHB to a final concentration of 5 × 105 CFU/mL and added to the wells of the 96-well plate containing two-fold dilutions of the tested compounds (250 µM to 0.25 µM) and a final concentration of CCCP of 10 µM. The MICs of the candidate compounds in the presence of CCCP were recorded visually after overnight incubation and confirmed with the INT reagent.

Time-kill kinetics assay

Two independent exponentially grown Staphylococcus aureus ATCC25923 cultures were centrifuged at 4500 g for a total of 10 min at room temperature. The supernatant of MHB was discarded and the cell pellet from one tube was resuspended in sterile staining buffer (phosphate buffer, pH = 7.4, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% Tween-20). The cell pellet from another tube was treated with absolute ethanol for ten minutes and centrifuged again under the same conditions. The absolute ethanol was discarded, and the cells were resuspended in staining buffer. Both cell suspensions, viable and dead cells, were further diluted in staining buffer to a final concentration of 1 × 106 CFU/mL and served together with unstained cells as single-stained compensation controls. The tested QAC candidates were diluted in the staining buffer to the final concentration of 2×MIC and MIC. Treated bacteria were labelled according to the manufacturer’s instructions with a mixture of two fluorescent dyes, thiazole orange (TO) and propidium iodide (PI), both of which are components of the commercially available BD™ Cell Viability Kit (BD Biosciences, Promega). The viability of the cells during the treatment with the QAC candidates was measured using the NovoCyte Advanteon flow cytometer (Agilent Technologies) and compared with the untreated cells labelled in the same way.

Atomic force microscopy and optical fluorescence microscopy measurements

Adhesive Petri dishes (WPI, Sarasota, FL, USA) coated with Cell-Tak were prepared as previously described56. An overnight culture of Escherichia coli DH5α cells was diluted in fresh Mueller-Hinton broth and propagated for one hour. An aliquot of exponentially grown E. coli DH5α cells was incubated in the coated Petri dish for ten minutes. Unbound cells were thoroughly rinsed with culture medium, making sure that the sample did not desiccate. The remaining immobilized cells were incubated for one hour in culture medium at 37 °C. Once the viability (cell division) of the immobilized cells was confirmed, the dish contents were rinsed again with culture medium and the untreated control cells were immediately measured or treated with a 4×MIC concentration of the candidate compounds for three hours. All atomic force microscopy measurements were performed using the Nano-wizard IV system (Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA) operating in quantitative imaging (QI) mode utilizing the MLCT-BIO-DC (E) probe (Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA). All data was acquired at a 500 pN setpoint with the extend/retract speed up to 150 μm/s while the Z length was up to 3000 nm at 128 × 128 pixels resolution. The collected AFM data were plane and line fitted and low-pass filtered using the JPK data processing software.

To obtain images of fluorescently stained cells after treatment, the culture medium was replaced with sterile physiological saline solution. Treated cells were stained in the dark with the nucleic fluorophores from the LIVE/DEAD™ BacLight™ Bacterial Viability Kit (Thermofischer Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Fluorescence images were taken half an hour after staining using the IX73 inverted fluorescence optical microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Scanning electron microscopy measurements

Each side of a microscopy coverglass was subjected to ultraviolet (UV) radiation for 30 min in a laminar flow hood. The sterile coverglass was then coated with a Cell-Tak solution in 0.1 M NaHCO3, rinsed with deionized water (mQ water), and air-dried within the sterile environment of the laminar flow hood. An overnight culture of Escherichia coli DH5α was diluted 1:10 in fresh Mueller-Hinton broth (MHB) and incubated for an additional hour at 37 °C with shaking at 170 revolutions per minute (rpm) in an orbital shaker incubator.

Aliquots (1 mL) of the propagated cell culture were transferred into sterile microtubes for the following treatments: untreated control, treatment with 16x minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of quaternary ammonium compound QApCl, and treatment with 8x MIC of QApBr. Both untreated and treated cells were incubated at 37 °C with shaking at 600 rpm for one hour.

Subsequently, 50 µL of each prepared cell sample was transferred onto the previously coated sterile coverglasses and incubated in a closed sterile Petri dish within the laminar flow hood to ensure optimal cell adhesion without desiccation. Each coverglass was then rinsed three times with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and the cells were fixed with 1 mL of 2.5% glutaraldehyde solution. After fixation, the coverglasses were rinsed three times with PBS followed by three additional rinses with mQ water. The coverglasses were then air-dried in the sterile laminar flow hood and subsequently mounted onto round specimen stubs covered with conductive carbon adhesive tape. Finally, to improve conductivity of the prepared samples, the samples were coated using the direct current coater Q150T ES Plus manufactured by Quorum Technologies (Quorum Technologies, UK). All samples were sputtered with a 3 nm layer of platinum using argon while the sputter current was 15 mA. The SEM imaging was done using the SM-74190UEC microscope produced by JEOL (Tokyo, Japan). The measurements were done in Gentle Beam mode with a 2 kV accelerating voltage using the SEI detector. The working distance was kept between 4 mm and 6 mm.

Detection of reactive oxygen species

Overnight culture of Escherichia coli ATCC25922 cells was diluted in fresh Mueller Hinton Broth and propagated for one hour. The cell suspension was centrifuged at 4500 g for 10 min at room temperature. The supernatant was discarded and the remaining cell pellet was resuspended (1:10) in sterile phosphate buffer saline (PBS). Aliquot of diluted cells was added to the Eppendorf tube containg PBS solution of compound to be tested. 2 µL of 2,7-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH2-DA) stock solution (1 mg/mL) was added to each reaction mix tube. Samples were incubated for 30 min in the thermal shaker at 37 °C. Fluorescence signal intensity was measured in 3 min time intervals using Tecan Infinite Pro200 plate reader at the 492 nm excitation and 523 nm emission wavelengths. Hydrogen peroxide was used as positive control. Blank samples were prepared correspondingly to each concentration of compounds tested with PBS buffer containing no cells.

Cytotoxicity

Healthy human cell lines, namely human embryonic kidney cells (HEK293) and retinal pigment epithelial cells (RPE1) were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM, Capricorn Scientific) at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. The culture medium was supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS, Capricorn Scientific) and a 1% mixture of penicillin and streptomycin (Pen/Strep, Capricorn Scientific). Prior to the experiment, the fully confluent cells were detached with trypsin-EDTA (0.05%) solution (Capricorn Scientific) and gently resuspended in DMEM medium. The concentration of cells in the solution was determined using a cell counter (Scepter, Merck) and the cells were further diluted in DMEM to a final concentration of 1 × 105 cells/ml. Duplicate serial dilutions of the compounds to be tested (250 µM to 0.25 µM) were prepared in DMEM in 96-well plates. The cells diluted to the desired concentration were added to the prepared plate containing the compounds and incubated for 48 h at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. Upon the treatment, 20 µL of the reagent MTS (CellTiter 96® Aqueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay, Promega) was added to each well and cells were further incubated with the reagent for additional three hours. Absorbance was measured at 490 nm in ELx808 optical reader (Bio-Tek). The IC50 values were calculated using GraFit 6.0 software and are given as the mean of three independent experiments performed in duplicates.

Conclusion

Quaternary ammonium compounds (QACs) represent a potent class of antimicrobial agents with widespread use and application possibilities. However, fast pace in resistance development demands new QACs design with elucidation of resistance mechanism(s). Here, a new class of QACs based on rationally designed 3-substituted quinuclidine have been synthesized and biologically tested revealing potent broad-spectrum bactericidal candidates with low potential to induce bacterial resistance. Namely, two candidates, QApCl and QApBr were selected for further investigation of their mode of action mechanism. Our results point out membranolytic activities accompanied by high levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that together with QACs treatment contribute to potent bactericidal activities. Both candidate compounds can disrupt bacterial membrane in just 15 min of exposure resulting in almost complete annihilation of bacterial population. Taken together, our results contribute to QACs field indicating that carful design choices might lead to structures of potent biological activity and strong membranolytic mode of action accompanied by production of ROS.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the the Croatian Science Foundation grant numbers UIP-2020-02-2356 (M.Š.), IP-2016-06-3775 (I.P.), STIM-REI, Contract Number: KK.01.1.1.01.0003, a project funded by the European Union through the European Regional Development Fund – the Operational Programme Competitiveness and Cohesion 2014-2020 (KK.01.1.1.01) and institutional projects 641-01/23-02/0008 (M.Š.), 641-01/23-02/0010 (R.O.) funded by the Faculty of Science, University of Split.

Author contributions

I.P. designed the new compounds; A.R., and A.R.K. were responsible for the preparation, characterization and purity analysis of the compounds; D.C. determined the antibacterial activity and cytotoxicity; D.C. performed fluorescence measurements, D.C. and M.Š. analyzed and interpreted biological data; L.K. and D.C. collected and analyzed AFM and fluorescence microscopy data; L.K., D.C. and I.W. determined and analyzed SEM data; R.O., I.P. and M.Š. designed and directed the study, I.P. and M.Š. secured funding, M.Š. wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Declarations

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work the author(s) used ChatGPT in order to improve language and readability. After using this tool/service, the author(s) reviewed and edited the content as needed and take(s) full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Ines Primožič, Email: ines.primozic@chem.pmf.hr.

Matilda Šprung, Email: msprung@pmfst.hr.

References

- 1.Dan, W., Gao, J., Qi, X., Wang, J. & Dai, J. Antibacterial quaternary ammonium agents: chemical diversity and biological mechanism. Eur. J. Med. Chem.243. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2022.114765 (2022) Elsevier Masson s.r.l. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Allen, R. A. et al. Ester- and amide-containing multiQACs: exploring multicationic soft antimicrobial agents. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett.27(10), 2107–2112. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2017.03.077 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.SkyQuest Technology Consulting Pvt. Ltd. Quaternary ammonium compounds market (SkyQuest). https://www.skyquestt.com/report/quaternary-ammonium-compoundsmarket

- 4.Vereshchagin, A. N., Frolov, N. A., Egorova, K. S., Seitkalieva, M. M. & Ananikov, V. P. Quaternary ammonium compounds (Qacs) and ionic liquids (ils) as biocides: from simple antiseptics to tunable antimicrobials. Int. J. Mol. Sci.22(13). 10.3390/ijms22136793 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Fedorowicz, J. & Sączewski, J. Advances in the Synthesis of biologically active quaternary ammonium compounds. Int. J. Mol. Sci.25(9), 4649. 10.3390/ijms25094649 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jennings, M. C., Minbiole, K. P. C. & Wuest, W. M. Quaternary ammonium compounds: an antimicrobial mainstay and platform for innovation to address bacterial resistance. ACS Infect. Dis.1(7), 288–303. 10.1021/acsinfecdis.5b00047 (2016) Am. Chem. Soc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alkhalifa, S. et al. Analysis of the destabilization of bacterial membranes by quaternary ammonium compounds: a combined experimental and computational study. ChemBioChem21(10), 1510–1516. 10.1002/cbic.201900698 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gilbert, P. & Moore, L. E. Cationic antiseptics: diversity of action under a common epithet. J. Appl. Microbiol.99(4), 703–715. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2005.02664.x (2005) Blackwell Publishing Ltd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maillard, J. Y. Bacterial target sites for biocide action. J. Appl. Microbiol.92(S1), 16S-27S (2002). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kwaśniewska, D., Chen, Y. L. & Wieczorek, D. Biological activity of quaternary ammonium salts and their derivatives. Pathogens9(6), 1–12. 10.3390/pathogens9060459 (2020) MDPI AG. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferreira, C., Pereira, A. M., Pereira, M. C., Melo, L. F. & Simões, M. Physiological changes induced by the quaternary ammonium compound benzyldimethyldodecylammonium chloride on Pseudomonas fluorescens. J. Antimicrob. Chemother.66(5), 1036–1043. 10.1093/jac/dkr028 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inácio, Â. S. et al. Quaternary ammonium surfactant structure determines selective toxicity towards bacteria: Mechanisms of action and clinical implications in antibacterial prophylaxis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother.71(3), 641–654. 10.1093/jac/dkv405 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang, C. et al. Quaternary ammonium compounds (QACs): a review on occurrence, fate and toxicity in the environment. Sci. Total Environ.518–519, 352–362. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.03.007 (2015) Elsevier. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mohapatra, S. et al. Quaternary ammonium compounds of emerging concern: classification, occurrence, fate, toxicity and antimicrobial resistance. J. Hazard. Mater. 445. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2022.130393 (2023) Elsevier B.V. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Liao, M., Wei, S., Zhao, J., Wang, J. & Fan, G. Risks of benzalkonium chlorides as emerging contaminants in the environment and possible control strategies from the perspective of ecopharmacovigilance. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 266. 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2023.115613. (2023). Academic Press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Buffet-Bataillon, S., Tattevin, P., Bonnaure-Mallet, M. & Jolivet-Gougeon, A. Emergence of resistance to antibacterial agents: the role of quaternary ammonium compounds - a critical review. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents.39(5), 381–389. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2012.01.011 (2012) (Elsevier B.V). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jennings, M. C., Forman, M. E., Duggan, S. M., Minbiole, K. P. C. & Wuest, W. M. Efflux pumps might not be the major drivers of QAC resistance in methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus. ChemBioChem18(16), 1573–1577. 10.1002/cbic.201700233 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morrison, K. R., Allen, R. A., Minbiole, K. P. C. & Wuest, W. M. More QACs, more questions: Recent advances in structure activity relationships and hurdles in understanding resistance mechanisms. Tetrahedron Lett.60(3). 10.1016/j.tetlet.2019.07.026 (2019) Elsevier Ltd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Schallenhammer, S. A. et al. Hybrid BisQACs: potent biscationic quaternary ammonium compounds merging the structures of two commercial antiseptics. ChemMedChem12(23), 1931–1934. 10.1002/cmdc.201700597 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kontos, R. C. et al. An Investigation into rigidity–activity relationships in BisQAC amphiphilic antiseptics. ChemMedChem14(1), 83–87. 10.1002/cmdc.201800622 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leitgeb, A. J. et al. Further investigations into rigidity-activity relationships in BisQAC amphiphilic antiseptics. ChemMedChem15(8), 667–670. 10.1002/cmdc.201900662 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.B. Belter, S. J. McCarlie, C. E. Boucher-van Jaarsveld, and R. R. Bragg. Investigation into the metabolism of quaternary ammonium compound disinfectants by bacteria. Microb Drug Resist. 10.1089/mdr.2022.0039 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Hoque, J. et al. Cleavable cationic antibacterial amphiphiles: synthesis, mechanism of action, and cytotoxicities. Langmuir28(33), 12225–12234. 10.1021/la302303d (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Radman Kastelic, A. et al. New and potent quinuclidine-based antimicrobial agents. Molecules. 24, 1–17. 10.3390/molecules24142675 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Odžak, R. et al. Quaternary salts derived from 3-substituted quinuclidine as potential antioxidative and antimicrobial agents. Open. Chem.15(1), 320–331 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Odžak, R. et al. Further Study of the Polar Group’s influence on the antibacterial activity of the 3-substituted quinuclidine salts with long alkyl chains. Antibiotics 12(8). 10.3390/antibiotics12081231 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Bazina, L. et al. Discovery of novel quaternary ammonium compounds based on quinuclidine-3-ol as new potential antimicrobial candidates. Eur. J. Med. Chem.163, 626–635. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.12.023 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Odžak, R., Crnčević, D., Sabljić, A., Primožič, I. & Šprung, M. Synthesis and biological evaluation of 3-amidoquinuclidine quaternary ammonium compounds as new soft antibacterial agents. Pharmaceuticals16(2). 10.3390/ph16020187 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Odžak, R., Primožić, I. & Tomić, S. 3-Amidoquinuclidine derivatives: synthesis and interaction with butyrylcholinesterase. Croat Chem. Acta80(1), 101–107 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paniak, T. J. et al. The antimicrobial activity of mono-, bis-, tris-, and tetracationic amphiphiles derived from simple polyamine platforms. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett.24, 5824–5828. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.10.018 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Black, J. W. et al. TMEDA-derived biscationic amphiphiles: an economical preparation of potent antibacterial agents. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett.24(1), 99–102. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.11.070 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Joondan, N., Caumul, P., Jackson, G. & Jhaumeer Laulloo, S. Novel quaternary ammonium compounds derived from aromatic and cyclic amino acids: Synthesis, physicochemical studies and biological evaluation. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 23510.1016/j.chemphyslip.2021.105051 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Takechi-Haraya, Y. et al. Effect of hydrophobic moment on membrane interaction and cell penetration of apolipoprotein E-derived arginine-rich amphipathic α-helical peptides. Sci. Rep.12(1). 10.1038/s41598-022-08876-9 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Joyce, M. et al. Natural product-derived quaternary ammonium compounds with potent antimicrobial activity, J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1–4. 10.1038/ja.2015.107 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Ali, I. et al. Synthesis and characterization of pyridine-based organic salts: their antibacterial, antibiofilm and wound healing activities. Bioorg. Chem.10010.1016/j.bioorg.2020.103937 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Jennings, M. C., Buttaro, B. A., Minbiole, K. P. C. & Wuest, W. M. Bioorganic investigation of multicationic antimicrobials to combat QAC-resistant staphylococcus aureus. ACS Infect. Dis.1(7), 304–309. 10.1021/acsinfecdis.5b00032 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sommers, K. J. et al. Quaternary phosphonium compounds: an examination of non-nitrogenous cationic amphiphiles that evade disinfectant resistance. ACS Infect. Dis.8(2). 10.1021/acsinfecdis.1c00611 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Bridier, A., Briandet, R., Thomas, V. & Dubois-Brissonnet, F. Resistance of bacterial biofilms to disinfectants: a review. Biofouling27(9), 1017–1032. 10.1080/08927014.2011.626899 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hoque, J. et al. Selective and broad spectrum amphiphilic small molecules to combat bacterial resistance and eradicate biofilms. Chem. Comm.51(71), 13670–13673. 10.1039/c5cc05159b (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saverina, E. A. et al. From antibacterial to antibiofilm targeting: an emerging paradigm shift in the development of Quaternary Ammonium Compounds (QACs). A ACS Infect. Dis.9(3), 394–422. 10.1021/acsinfecdis.2c00469 (2023) American Chemical Society. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tuon, F. F. et al. Antimicrobial treatment of staphylococcus aureus biofilms. Antibiotics 12(1). 10.3390/antibiotics12010087 (2023) MDPI. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Garrison, M. A., Mahoney, A. R. & Wuest, W. M. Tricepyridinium-inspired QACs yield potent antimicrobials and provide insight into QAC resistance. ChemMedChem 16(3) 463–466. 10.1002/cmdc.202000604 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Lemos, J. A. et al. The biology of streptococcus mutans. Microbiol. Spectr.7(1). 10.1128/microbiolspec.gpp3-0051-2018 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Theophel, K. et al. The importance of growth kinetic analysis in determining bacterial susceptibility against antibiotics and silver nanoparticles. Front. Microbiol.5(11), 544. 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00544 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yates, G. T. & Smotzer, T. On the lag phase and initial decline of microbial growth curves. J. Theor. Biol.244(3), 511–517. 10.1016/j.jtbi.2006.08.017 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brayton, S. R. et al. Soft QPCs: biscationic quaternary phosphonium compounds as soft antimicrobial agents. ACS Infect. Dis. 10.1021/acsinfecdis.2c00624 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Loftsson, T. et al. Soft Antimicrobial Agents: Synthesis and Activity of Labile Environmentally Friendly Long Chain Quaternary Ammonium Compounds. J. Med. Chem.46, 4173–4181. 10.1021/jm030829z (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tischer, M., Pradel, G., Ohlsen, K. & Holzgrabe, U. Quaternary ammonium salts and their antimicrobial potential: targets or nonspecific interactions?. ChemMedChem7(1), 22–31. 10.1002/cmdc.201100404 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kiernan, J. A. Formaldehyde, formalin, paraformaldehyde and glutaraldehyde: what they are and what they do. Micros Today8(1), 8–13. 10.1017/s1551929500057060 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dapson, R. W. Macromolecular changes caused by formalin fixation and antigen retrieval. Biotech. Histochem.82, 133–140. 10.1080/10520290701567916 (2007). no. 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]