Abstract

Precision oncology tailors treatment strategies to a patient’s molecular and health data. Despite the essential clinical value of current diagnostic methods, hematoxylin and eosin morphology, immunohistochemistry, and gene panel sequencing offer an incomplete characterization. In contrast, highly multiplexed tissue imaging allows spatial analysis of dozens of markers at single-cell resolution enabling analysis of complex tumor ecosystems; thereby it has the potential to advance our understanding of cancer biology and supports drug development, biomarker discovery, and patient stratification. We describe available highly multiplexed imaging modalities, discuss their advantages and disadvantages for clinical use, and potential paths to implement these into clinical practice.

Significance: This review provides guidance on how high-resolution, multiplexed tissue imaging of patient samples can be integrated into clinical workflows. It systematically compares existing and emerging technologies and outlines potential applications in the field of precision oncology, thereby bridging the ever-evolving landscape of cancer research with practical implementation possibilities of highly multiplexed tissue imaging into routine clinical practice.

The Promise of Precision Oncology: Molecular Profiling to Optimize Cancer Therapy

Precision oncology is built on the premise that tumors exhibit specific molecular alterations that can be targeted with drugs designed to interfere with resulting deregulated pathways, thereby providing a more effective treatment. Cancer originates from the acquisition and accumulation of cell- and patient-specific genetic mutations, resulting in heterogeneous cancer cells within and between individuals (1). Rather than basing treatment decisions on the anatomical localization and histology of a tumor, precision oncology aims at a treatment strategy that takes into account the molecular profile of a cancer. Therefore, precision oncology is expected to result in fewer side effects than current therapies and to yield superior survival outcomes. The first steps toward this goal have been made using classical immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis of tumor tissue sections coupled with genomic and other bulk omics analyses. However, conventional IHC and immunofluorescence are limited to visualize a maximum of three and seven markers, respectively. Recently developed highly multiplexed tissue imaging (HMTI) methods have overcome spectral limitations, pushing multiplexing capacities to higher numbers. These advances allow the detection of dozens of markers within tissue samples at up to subcellular resolution. These methods further provide multiscale information ranging from molecular data in single cells to the spatial structure of tumors. The resulting novel layers of information provide information on in situ tumor biology that can guide drug development, advance biomarker discovery, and refine patient stratification. In this review, we discuss the current state of the art of HMTI and how these approaches may be integrated into the clinical setting. We focus on antibody-based, protein-level imaging methods that provide single-cell resolution. We do not review the exciting potential of digital pathology, antibody-independent spatial mass spectrometry, or spatial transcriptomic methods (2).

Current Status of Precision Oncology

Although surgical resection, along with untargeted treatments such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy, remains the backbone of cancer patient care, targeted therapies are routine in clinical practice. These form the foundation of precision oncology. The selective estrogen receptor modulator tamoxifen was the first targeted therapy to be approved by the FDA in 1977, paving the way for today’s hormone-modulating therapies (3). Current targeted therapies may be hormone-modulating therapies, monoclonal antibody–based therapeutics, small-molecule inhibitors, or immunotherapies (Fig. 1). The advent of high-throughput DNA sequencing and subsequent initiation of consortia, such as The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and the International Cancer Genome Consortium, led to the systematic identification of targetable cancer-driver mutations (4). Based on the knowledge of key cancer genomic alterations, small-molecule inhibitors have been developed and approved for clinical use. These inhibitors specifically target deregulated cellular (signaling) pathways that drive the progression of cancer. This class of therapeutics include inhibitors of kinases (e.g., imatinib), the DNA damage response pathways (e.g., olaparib), the proteasome (e.g., bortezomib), modulators of apoptosis (e.g., venetoclax), epigenetic modifications (e.g., vorinostat), and metabolism (e.g., everolimus; ref. 5). Rituximab was the first monoclonal antibody approved for cancer therapy and is primarily used to treat patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (6). Trastuzumab, which is specifically used to treat patients with HER2 amplification, was the first monoclonal antibody approved for use in solid tumors (7). In antibody–drug conjugates, the antibody component is directed against a cancer-specific target resulting in selective delivery of the linked payload to cancer cells. Currently, more than 200 FDA-approved targeted therapies are available for the treatment of patients with cancer, and more than 1,000 agents are being tested in clinical trials worldwide.

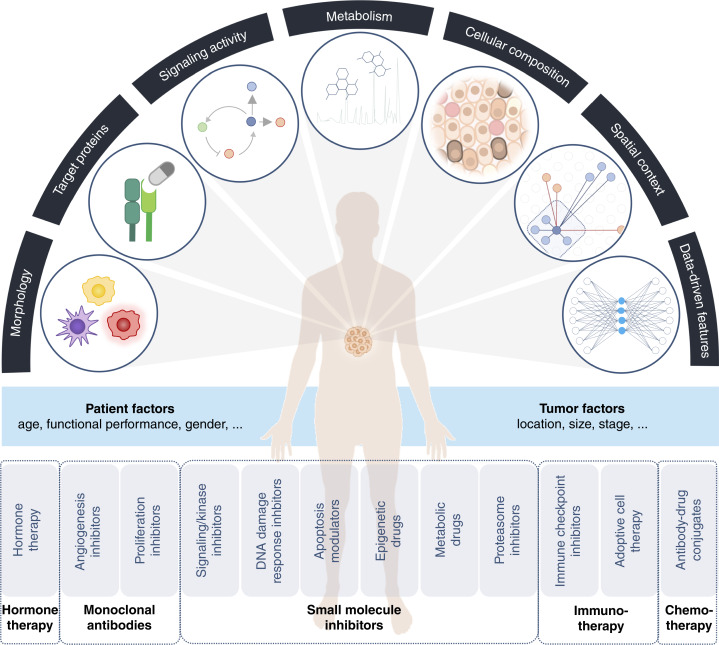

Figure 1.

Potential transformation of precision oncology through highly multiplexed tissue imaging. Using HMTI various types of information can be derived from a tissue sample including its cellular composition, presence of target proteins, signaling pathway activity, metabolism, intercellular interactions (e.g., immune cell infiltration), and spatial context. Further, complex features can be derived from the collected data using machine learning algorithms. Consideration of molecular tumor characteristics as well as personal factors guide selection of a targeted therapy in precision medicine. (Created with BioRender.com.)

In recent years, the focus of cancer research has broadened beyond a tumorcentric view to include the tumor microenvironment (TME), an ecosystem populated by tumor and normal cells such as immune, stromal, and nerve cells. The cells of the TME interact dynamically to influence all aspects of tumor biology and their intercellular interactions and communication can be targeted by therapeutic approaches. The discovery of coinhibitory receptors, used by tumor cells to evade the immune response, revolutionized cancer treatment and checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy is routinely used for the treatment of certain cancer types (8). The reactivation of antitumor T-cell immunity provides long-lasting response in 10% to 60% of patients depending on the cancer indication (9). For example, anti-CTLA-4 antibody ipilimumab and anti-PD-1 antibody nivolumab are used to treat unresectable stage IV melanoma (10). Another form of immunotherapy is adoptive cell therapy in which patient-derived immune cells are activated and expanded ex vivo before being reinjected into the patient. In chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy, a patient’s T cells are modified to express CARs that specifically target tumor cells. CAR T-cell therapy is FDA-approved for the treatment of lymphoma and multiple myeloma (11) but currently shows limited effectiveness in the treatment of solid tumors. Cancer-promoting elements in the TME can also be targeted. For instance, bevacizumab, a monoclonal antibody that targets VEGF-A, was originally approved for treating metastatic colorectal cancer but is now used to inhibit angiogenesis in various cancer types (12). As our understanding of TME functions expands, the number of therapies targeting different aspects of the TME will increase.

Given the many available targeted drugs, genomic characteristics are now routinely clinically evaluated to guide treatment decisions for patients with some cancer types. For example, disease drivers can be identified using mutation-specific antibodies (13), and genetic testing now ranges from focused panels that target known genetic variations to broader panels covering hundreds of genes as well as whole-exome sequencing or whole-genome sequencing (14). The combined use of genomic profiling and genetically matched targeted therapies has led to improved outcomes in various types of cancer (15). Examples of successful targeted therapies include those that target BRAFV600-mutated melanoma (16), HER2-amplified breast and gastric cancer, EGFR-mutant lung cancers (17), and IDH1/2-mutated low-grade gliomas (18).

Advancing Precision Oncology through Highly Multiplexed Tissue Imaging

Pathology, at its core, studies cellular arrangement, morphology, and contextual presentation within healthy and diseased tissues. Numerous scoring systems for cancer hinge upon observable transformations in cellular appearance and their deviations from the norm. State-of-the-art precision oncology adopts a complementary approach, primarily focusing on genetic and molecular changes across millions of cells to guide treatment decisions. As precision oncology has advanced, efforts have been made to integrate genetic analyses into spatial information from pathology. For instance, in melanoma, BRAF mutations are often identified through genetic analysis and subsequently confirmed using a V600E-mutation specific antibody in IHC analysis. Both the molecular and morphological perspectives provide crucial data about the state of disease and therapy options. In an ideal scenario, patient-derived tumor tissue would be analyzed to identify the targetable biological features that drive tumor progression. This will likely require collection of genomic, transcriptomic, metabolomic, and proteomic information in a spatially resolved manner. HMTI methods have the potential to harmonize current clinical pathology and precision oncology, merging the morphological/spatial and molecular dimensions into a cohesive picture and eventually revealing tumor-promoting and targetable features. A meta-analysis demonstrated that prediction of patient response to immunotherapy can indeed be improved by employing a multiplexing biomarker strategy over single-plex methods, such as IHC, tumor mutational burden, or gene expression profiling across different types of solid tumors (19). This underscores the importance of incorporating additional markers and spatial characteristics such as PD-1/PD-L1 proximity, CD8+ T-cell density, and co-expression with T-cell activation and exhaustion markers to improve prediction of therapy response. While it is impossible to predict the future, the information that can be gained from highly multiplexed tissue imaging makes it highly likely that quantitatively measured protein expression in the context of spatial information will be critical for the future implementation of precision medicine.

Analysis of Tumor Features for Precision Oncology

Cancer arises as a result of the deregulation of biological processes at the molecular and cellular level, and understanding this deregulation can guide the choice or development of precision treatments. Although a tumor typically originates in a specific cell type and due to recurrent genomic alterations, tumors are characterized by genomic instability and hence heterogeneity in the cells that form local and larger cell communities. Differences in the cellular microenvironment across intratumoral regions further contribute to differences in gene expression and signaling states in individual tumor cells. Consequently, even cancers driven by a mutation in the same gene in different patients often diverge phenotypically. Tumor heterogeneity can be broken down into heterogeneity at the level of individual features including cell morphology, protein abundance, signaling activity, metabolism, cellular phenotypes and composition, and spatial context that alone or combined can inform on therapy (Fig. 1). Individual features may also combine to form abstract representations, which do not have a direct biological interpretation, and which may be identified computationally to provide actionable information. The following paragraphs provide an overview of features extractable from clinical tumor tissue samples using HMTI, along with examples of their application in current clinical practice.

Morphology

Pathologists routinely perform a morphological assessment of cellular characteristics. Numerous tumor grading and staging systems rely on the aberrant appearance of cell nuclei, deviations in cellular architecture from normal tissue, and the degree of cellular differentiation. In diffuse gliomas, for instance, histological features including mitotic activity, nuclear atypia, vascular proliferation, and the presence of necrosis distinguish low- from high-grade tumors, thus guiding critical treatment decisions (20). Morphological features form the basis of current pathology and will continue to be a cornerstone of tissue analysis in future. HMTI techniques allow derivation of morphological information about cells including eccentricity, size and nuclear shape; high-resolution HMTI methods may even provide a similar level of detail as traditional H&E. A recent study highlights that hyperdimensional molecular data can also encode morphological features and pathological annotations from hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining (21). Importantly, H&E can also be directly applied to the identical tissue section used for HMTI, enabling H&E based morphological and molecular analysis simultaneously (22).

Target Proteins

A key focus of precision oncology is the phenotypic characterization of tumor cells to determine the presence of proteins that can be targeted by available drugs. In breast cancer, for example, the presence of hormone receptors defines the luminal breast cancer subtypes and patients with these subtypes are treated with hormone-modulating therapy to selectively target hormone-dependent tumors. Similarly, the level of PD-L1 influences response to anti-PD-1/PD-L1 treatment and affects treatment decisions in immunotherapy in a range of tumor subtypes (23). Assessment of target protein levels by IHC is routinely incorporated into precision oncology and frequently complemented by genomic testing. While traditional IHC offers insights into one marker at a time, HMTI enables evaluation of multiple target proteins simultaneously. Additionally, antibodies targeting mutated protein variants (e.g., BRAFV600E-specific antibodies) may facilitate decision-making when selecting from multiple therapy options or prioritizing genomic test results.

Signaling Pathway Activity

In many cases, quantifying a target protein is not sufficient to infer efficacy of the corresponding therapeutic agent, e.g., abundances of kinases are largely unrelated to their activity and evaluation of protein abundance can thus overestimate or underestimate drug effectiveness (24). Like IHC, HMTI methods allow the detection of phosphorylated and mutated proteins, which are more indicative of the activity status than total abundance (e.g., BRAFV600E- or phospho-ERK-specific antibodies). HMTI can also capture information on downstream signaling or alternate pathways, which could provide guidance for the selection of treatment combinations. For example, sensitivity to HER2-targeted therapies in breast cancer patients can be lost upon compensatory activation of EGFR or its ligands (25), and, in melanoma, the simultaneous inhibition of BRAF and MEK kinases within the same pathway, known as vertical inhibition, has proven effective in overcoming resistance caused by MEK activation (26). However, the evaluation of phosphorylated proteins as a measure of pathway activity has not been implemented in routine clinical practice yet.

Metabolism

Deregulated metabolism is a hallmark of cancer that is tightly linked to the aberrant oncogenic signaling within and between cells in the TME, influencing therapy response and drug resistance (27–31). For example, hypoxic TMEs favor tumor growth and drive metabolic T-cell dysfunction through mechanisms related to glucose deprivation (32). Although analysis of metabolites in tumors is not routine in clinical testing, techniques like magnetic resonance spectroscopy are used to evaluate patients with gliomas to detect alterations in choline, creatine, and N-acetylaspartate levels, indicative of cellular, proliferation, energy metabolism, and neuronal integrity (33). Key metabolic enzymes such as isocitrate dehydrogenase mutations or lactate dehydrogenase associated with anaerobic glycolysis are frequently assessed to discern glioma subtypes (20). Recognizing the importance of metabolism, clinical trials are currently underway to assess the efficacy of metabolic enzyme inhibition through administration of small-molecule drugs or the implementation of dietary regimens (34–40). By measuring key proteins regulating metabolism, HMTI can enable metabolic profiling (41), alone or in conjunction with multiphoton redox ratio imaging (42) and stimulated Raman scattering (43, 44), which enable direct metabolic imaging.

Cellular Composition

The cancer cells in a tumor consist of genetically diverse subpopulations, each with distinct phenotypes and clinical relevance (45–48). When more than 15% of cells in non–small cell lung cancer exhibit a fusion of the ALK gene, targeted therapy tailored to this rearrangement may be considered (51). In the case of breast cancer, patients are diagnosed with positive hormone receptor status if at least 1% of cells express estrogen or progesterone receptor, leading to tamoxifen treatment. Interestingly, the up to 99% of hormone receptor negative cells remain unexplored by existing clinical markers; here HMTI could provide valuable additional insights. The frequencies and phenotypes of non-tumor cells in the TME strongly influence disease outcome and progression. For example, high levels of some types of cancer-associated fibroblasts are correlated with poor survival for patients with lung adenocarcinoma (50, 51), whereas infiltration of inflammatory immune cells is often a positive predictor of patient outcome (52). Overall, HMTI methods will be able to provide information to enable clinicians to incorporate complete cellular composition into decision making.

Spatial Context and Intercellular Signaling

Although tumors do not have the structural characteristics of healthy tissue, cells in tumors do adopt distinct spatial patterns correlated with therapy response and with immune system function (53–58). For example, topographical distances between exhausted and regulatory T cells and tumor cells were used to develop a spatial score prognostic for immunotherapy response in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (57), and, in patients with colorectal cancer, disruption of cellular neighborhoods is associated with inferior outcome (58). Other multicellular structures, such as tertiary lymphoid structures, stratify melanoma patients into responders and non-responders to immunotherapy (59, 60). HMTI is uniquely equipped to provide data on spatial context of individual and groups of cells, which cannot be obtained from single-plex IHC; using the appropriate markers, HMTI enables comprehensive intercellular signaling assessment.

Data-Driven Markers

Omics’ approaches are reshaping the field of precision oncology from a “one-gene, one-drug” approach to a “multi-gene, multi-drug” paradigm (61). Using machine learning approaches to analyze spatial HMTI data obtained on large (retrospective) patient cohorts can identify novel biomarkers that are reflective of the multivariate and combinatorial nature of tumors (62, 63). In clinical practice, neuropathologists already employ a random-forest algorithm for a DNA methylation-based classification of central nervous system tumors when conventional methods do not yield a distinct diagnosis (64). In addition, the FDA recently approved the first convolutional neural network-based software for cancer detection and grading of prostate biopsies using whole-slide H&E images (65). Currently, such algorithms only aid pathologists in final decision-making. In contrast to the currently prevailing biological insight–driven approach, complex patterns identified in the raw data through algorithms such as artificial intelligence might be highly predictive but difficult to interpret biologically at first. However, these patterns may have the potential to pinpoint and identify novel disease mechanisms, thereby being transformed into more interpretable features aiding in the development of innovative therapies.

Highly Multiplexed Imaging Techniques and Analysis

Evaluating Technical Parameters for Clinical Application

To understand the heterogeneity of cancer cells, the composition of the TME, and the workings of single cells and multicellular assemblies, dozens of marker combinations must be analyzed in the spatial context of the patient tissue (66, 67). HMTI techniques enable the direct visualization and quantification of protein expression and spatial relationships within the TME. Notably, HMTI techniques closely resemble traditional IHC, providing a familiar framework for pathologists and oncologists. HMTI differs, however, from IHC in terms of multiplexing capacity, dynamic range and sensitivity, resolution, acquisition time, thus affecting the sample area that can be imaged in high throughput settings, and data type and size. We will discuss each of these technical parameters in more detail with regard to clinical requirements; downstream data analysis and interpretation are discussed in “Computational Analysis”.

Dynamic Range and Sensitivity

In clinical settings, a protein’s concentrations can vary widely, spanning at least two orders of magnitude and potentially up to four in cases of gene amplification (68). To detect proteins with the highest and lowest abundances simultaneously, it has been estimated that seven orders of magnitude are needed (69). The current gold standard IHC only covers one to two orders of magnitude, resulting in bimodal staining distributions rather than continuous concentration readouts in many cases (70, 71). Recognizing however that quantitative abundance of receptor expression better correlates with therapy response than mere presence or absence (72), started a transition toward more fine-grained expression scales for tumor evaluation. This shift is exemplified in breast cancer, where a recent clinical trial suggests classification not only as HER2-positive or -negative but to also to include HER2-low as a third category (73), making the ordinal HER2 scoring system ranging from 0 to 3 more clinically relevant (74). Aiming for continuous scales will require methods with a large dynamic range that provide quantitative readouts. This is provided by several HMTI methods. Additionally, the ability to monitor broad dynamic ranges may reduce the need for additional assays, particularly in cases of overexpression, where quantitative methods such as fluorescence in situ hybridization must be used to supplement IHC data (75). The sensitivity of HMTI refers to its ability to detect and measure a target analyte, often reported as the minimal concentration of antibodies required for detection. Particularly challenging and lowly expressed markers in clinical practice are PD-L1 and CTLA-4 relevant for immunotherapy decisions. Notably, these can still be detected across different HMTI platforms (76, 77). However, differing detection limits among assays complicate result standardization and the establishment of universal standards and thresholds is needed (78). Future requirements for the sensitivity of HMTI assays will heavily rely on the current gold standard IHC. To enable detection of identical low abundant biomarkers, amplification methods might have to be implemented for HMTI (79). Particularly in scenarios involving the detection of rare cells defined by low abundant markers, achieving high sensitivity and specificity in both assay performance and antibody selection is essential for ensuring the accuracy and reliability of assay results.

Resolution

The level of detail in an image varies depending on the resolution of the HMTI technique. HMTI methods with a resolution of 0.25 μm can resolve sub-cellular structures and morphological features, similar to IHC-based pathology. At around 1 μm resolution, marker readouts and membrane/cytoplasm/nuclear distribution can still be determined at the individual cell level. HMTI techniques with lower resolution lack the ability to discern single cells but do provide insights into tissue-level structures and expression. The clinical requirements for HMTI resolution will depend on the specific application. It is unlikely that HMTI will in the foreseeable future replace traditional low-plex image analysis; rather we expect that HMTI will be integrated alongside conventional pathology methods (e.g., H&E and HMTI could be done on the identical tissue section). As a result, morphological readout from HMTI methods may be less relevant than protein marker readout. Emerging evidence suggests that high-resolution features can be inferred from low-resolution images, enabling deep learning classifiers to accurately classify histopathological images at a resolution of 1 μm (80). Taken together, this implies that for most applications a single-cell resolution may suffice to guide clinical decision making. Single-cell resolution images have considerably reduced data size compared to sub-cellular resolution images and align with current standards in precision oncology where marker readouts are typically reported as a percentage of positive cells or distributions of individual cell phenotypes.

Multiplexing Capacity

The optimal number of markers will highly depend on the specific application and the clinical question to be answered by a technique. Although HMTI is not yet part of routine clinical practice, genetic testing provides a starting point for assessing multiplexing requirements. For example, commercially available RNA-based arrays use 21 genes to predict recurrence risk in breast (81). Gene panel sequencing tests assess up to a few hundred genes but in clinical practice <50 are routinely considered for decision making. As proteins are the active agents within cells, analysis of fewer than 50 proteins may provide similar classification. For classification of breast cancer subtypes, four protein markers are required. In the case of lung cancer, up to nine antibodies are required for a full assessment (82). With the expanding landscape of molecularly targeted therapies and biomarkers in preclinical research, higher multiplexing systems will be required to select the initial treatment. Hence, for defined classification tasks, a limited but growing number of markers may be sufficient. In scenarios where standard therapy has failed, multiple therapy options must be assessed; HTMI methods will allow such analyses to be done simultaneously. These considerations reflect current diagnostic tools, but as discussed in “Analysis of Tumor Features for Precision Oncology”, the high multiplexing capabilities of HTMI will enable determination of cell phenotypes, cell state, and spatial dependencies which should enable the derivation of novel predictive biomarkers. For example, using around 30 tumor-focused antibodies, we identified 14 patient-spanning tumor phenotypes that further subdivided existing clinical patient groups and associated with survival of patients with breast cancer (48). Moreover, higher multiplexity might be desired to include several antibodies against the same target and thus increase robustness and reproducibility.

Sampling Area

The area of a tumor sample that must be analyzed to accurately reflect properties of the whole tumor is currently unknown (21). We recently found that the extent of spatial segregation of cell phenotypes within a tissue influences optimal sampling design and that this parameter varies between tissues (83, 84). A total sampling area of 1.6 mm2 was sufficient to capture around 80% of cell phenotypes across different tissue samples, but the distribution of fields of view may differ dependent on spatial segregation of a given tissue. Thus, increased sampling will be required in cases of samples where tumors are heterogenous (21, 48). Looking forward, to accurately determine the optimal amount of tumor region analyzed, will need more comprehensive and systematic studies. Further, the focus in previous studies has been on the effects of sampling on measuring cellular frequencies, but the necessary tissue area to ensure consistent spatial relationships has not been analyzed (21). Moreover, sampling strategy can affect diagnosis: choosing regions of interest based on selection criteria or randomly can lead to different results (85). Guiding region selection for HMTI analysis by a pathologist may thus reduce the number of regions of interest compared to random sampling. Therefore, employing whole-slide H&E imaging to guide region selection for HMTI of multiple smaller regions is a promising approach. However, in the clinical setting, only fine-needle biopsies may be available for diagnostics depending on the tumor type, automatically limiting the measurement area. Ultimately, the required sampling area and strategy must be determined during the development of a biomarker.

Pros and Cons of Available HMTI Techniques

Clinical implementation of HMTI has been hindered by various challenges. These challenges include technical challenges, stemming from research instrumentation not geared for clinical use, the highly specialized skills needed to optimize, validate, and routinely and reproducibly perform highly multiplex staining, imaging, and data analysis (Table 1) and regulatory approval. As a result, none of the available HMTI technologies meet all criteria for routine clinical implementation yet. This currently limits use of HMTI technologies to research and translational applications.

Table 1.

Comparison of multiplexed imaging technologies.

| Fluorescence-based methods with cyclic staining | Fluorescence-based methods with cyclic imager staining | Metal isotope-based methods | Enzyme-based methods | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cycIF | IBEX | CODEX | Immuno-SABER | IMC | MIBI | Opal IHC | |

| Reported number of markers | ∼60 proteins | ∼60 proteins | ∼60 proteins | ∼10 proteins | ∼40 proteins | ∼40 proteins | 7–9 proteins |

| Simultaneous marker readout | 4 per cycle | 4 per cycle | 3 per cycle | 4 per cycle | ∼40 | ∼40 | 1 per cycle |

| Resolution | ∼0.2 μm | ∼0.2 μm | ∼0.2 μm | ∼0.2 μm | 1 μm | ∼0.2 μm | ∼0.2 μm |

| Sensitivity | + | + | + | ++ | + | ++ | ++ |

| Dynamic range (logs) | 2–3 | 2–3 | 2–3 | 2–3 | 5 | 5 | 1–2 |

| Commercial solution | Miltenyi, Leica, Lunaphore, Canopy | — | Akoya, Ultivue | — | Standard BioTools | — | Akoya |

| Samples | FFPE, FF | FFPE | FFPE, FF | FFPE | FFPE, FF | FFPE, FF | FFPE, FF |

| Time-limiting step | Antibody staining and imaging cycles | Antibody staining and imaging cycles | Probe binding and imaging cycles | Probe binding and imaging cycles | Image acquisition | Image acquisition | Antibody staining cycles |

| Duration of time-limiting step | Less than one hour* | Few hours* | Less than one hour* | Few hours* | 20 minutes/mm2 | 1 hour/mm2 | Several minutes* |

| Key references | (90, 91) | (92) | (59) | (96) | (101) | (100) | (86) |

Broadly, technologies can be categorized into fluorescence-based reporter methods with cyclic staining or imaging, metal isotope-based reporter methods, and enzyme-based methods methods. Each method is compared based on the reported maximal number of markers, resolution, sensitivity, dynamic range, availability of commercial solutions, applicability to sample type, time-limiting step, duration of time-limiting step as well as key references. *depending on size of imaged area and resolution. IMC, imaging mass cytometry.

Abbreviations: FF, fresh frozen.

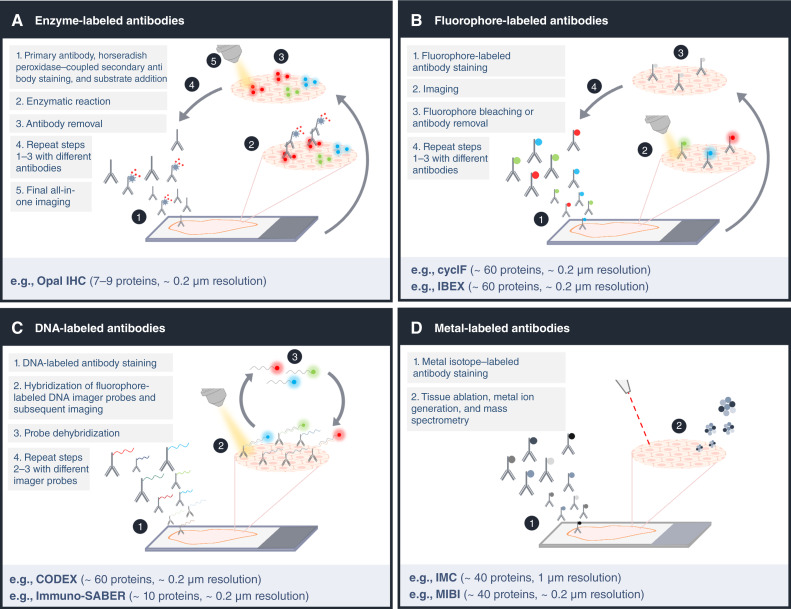

One of the most broadly used multiplexed enzyme-based approaches is the Opal IHC technology, based on enzyme-labeled secondary antibodies (Fig. 2A). In this multistep staining process, covalent binding of tyramide-coupled fluorophores to tyrosine residues in close proximity to the antigen of interest results in signal amplification (86). The primary or secondary antibody complex is removed, retaining the tyramide-conjugated fluorophore on the tissue, before the next antibody-tyramide-fluorophore combination is applied. Once all the staining cycles have been achieved, the data acquisition is performed in a single step. A substantial advantage of IHC-based approaches is that very low-abundance targets can be detected due to strong signal amplification (86). Additional advantages are ease of use, affordability, workflows known to diagnostics labs, and high intersite and intrasite reproducibility (86). Further, the process is fully automated, so data generation is time-efficient and cost-effective. Disadvantages are the limited multiplexicity, a low dynamic range, and that data quality of enzyme-based methods is affected by biomarker co-expression, enzyme–antibody pairing, sample thickness, multispectral unmixing, and biomarker detection order (86). Nevertheless, workflow optimization allows for the accurate detection of key biomarkers in various types of tissue as shown by the high correlation with single-plex detection data from chromogenic acquisitions (86–88).

Figure 2.

Comparison of multiplexed imaging technologies. A, Enzyme-based technologies such as Opal IHC use antibody-binding dependent enzymatic reactions for fluorescent deposition and detection, avoiding the issue of secondary antibody cross-reactivity. B, Fluorophore-labeled antibodies are used in cyclF and IBEX for marker detection in a direct or indirect manner, respectively. C, The DNA tag-based methods CODEX and immune-SABER rely on oligonucleotide tags for one-step antibody staining followed by multiple rounds of DNA imaginer probe hybridization. D, Metal-isotope tags are used to label antibodies for mass spectrometry-based IMC and MIBI methods. The metal isotopes are simultaneously detected via tissue ablation. (Created with BioRender.com.)

The low number of markers detected simultaneously using enzyme-based approaches can be overcome by using antibodies directly or indirectly labeled with a fluorescent reporter. Even though the spectral overlap of fluorophores limits the number of antigens that can be imaged simultaneously using conventional immunofluorescence (89), this hurdle can be addressed by using iterative cycles of tissue analysis. In iterative imaging, the number of fluorophores used per cycle is minimize to prevent interfering signals in each acquisition step. Fluorescent-based methods include cyclic immunofluorescence (CycIF; refs. 90, 91), iterative indirect immunofluorescence imaging (4i), iterative bleaching extends multiplexity (IBEX; ref. 92), and sequential immunofluorescence (seqIF; ref. 93). These methods employ repeated cycles of antibody incubation and binding, image acquisition, and signal inactivation by photobleaching or antibody removal to acquire conventional low-plex fluorescence images of a sample which are compiled into a high-dimensional representation (Fig. 2B; ref. 90). Advantages of fluorescence-based methods are that they enable the measurement of large tissue areas using slide scanners and that at least 60 markers can be imaged (and in principle even more). Recently, microfluidic based instruments have emerged that greatly reduce cycle time, enabling high-plex whole slide imaging in a day (93). Autofluorescence and a relatively low dynamic range can limit sensitivity and quantitativeness of all fluorescence-based methods, potentially causing false-positive results (94). Further, tissue integrity can be lost in a cycle- and tissue-dependent manner (95) and sequential staining alters antigenicity and signal-to-noise ratio over time (90). These practical limitations can make the optimization of staining protocols for many markers cumbersome.

In addition to microfluidic approaches, the limited throughput caused by repeated cycles of antibody incubation can be overcome by using antibodies conjugated with DNA barcodes (58, 96). In one such strategy, called co-detection by indexing (CODEX), the tissue is incubated with all DNA-barcoded antibodies simultaneously followed by cycles of readout of these barcodes by addition and removal of fluorescently labeled DNA imager probes (Fig. 2C). This strategy drastically reduces experimental time compared to most antibody cycling methods (97). A limitation of CODEX is low sensitivity due to direct coupling of the reporter to the antibody. Immunostaining with signal amplification by exchange reaction (immuno-SABER) improves sensitivity compared to CODEX by hybridization of orthogonal DNA concatemers that are complementary to the fluorescent imager strand. Despite being faster, DNA-barcode based antibody detection offers the same advantages as fluorescently labeled antibodies in terms of large field of view and the same challenges in terms of autofluorescence, signal spillover, and (to a lesser extend) tissue degradation through cycles.

Recently, hyperspectral methods that rely on the full emission spectrum rather than assigning a primary color to each fluorophore have become broadly available. The efficacy of these methods has been demonstrated by the development of a platform for the multiparametric assessment of circulating tumor cells (98). Using advanced instrumentation and computational methods, hyperspectral modalities can image of up to 21 channels at the same time (99), thereby overcoming issues associated with serial imaging approaches, though fluorescence-based challenges such as autofluorescence still exist. Similarly, the Orion platform uses fluorophores specifically designed for spectral extraction using discrete sampling techniques. This allows for an 18-plex IF staining in a single cycle, followed by H&E staining on the same section (22).

An alternative to fluorescence- and enzyme-based approaches are mass-spectrometry-based imaging methods that use mass tag-coupled antibodies (Fig. 2D). One type of mass-tag is non-biological metal isotopes. These do not have a background noise from tissue-derived “autofluorescence” (i.e., endogenous metals), and they do not alter the specificity of primary antibodies upon conjugation (100). Mass-tag-based methods differ in their modality to transferring the metal-isotopes bound to antibodies for mass spectrometry analysis. IMC uses a laser to introduce tissue into plasma to ionize metal isotopes (101), whereas multiplex ion beam imaging (MIBI) employs a directly ionizing primary ion beam (100). Due to low signal overlap between neighboring metal isotopes and high linear dynamic range, antibody panel design is highly flexible and panels can be optimized rapidly. Both IMC and MIBI are reproducible across serial sections (R2 = 0.94), allow the imaging of more than 40 antibodies simultaneously in a quantitative manner, and generate results concordant with single-plex IHC (102). A major drawback is a comparatively slower imaging speed to IF methods. An emerging mass-tag based approach uses matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization (MALDI) based detection of peptides linked to antibodies (MALDI-IHC). The main advantage is that this approach should make it possible to image hundreds of antibodies simultaneously, but both resolution and sensitivity will need further improvement for single cell resolved imaging (103). In addition to measurement of peptide-tagged antibodies, this approach also allows the direct detection and identification of a wide range of other molecule types including lipids, and metabolites in situ (104).

MALDI-IHC is just one example of rapid and innovative advances in the field of HMTI. The CosMx spatial molecular imaging method developed by Nanostring can detect up to 1,000 RNA transcripts and more than 60 proteins in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue sections at subcellular resolution simultaneously (105). This procedure involves staining the sample with a combination of RNA probes and oligonucleotide conjugated-antibodies that are detected in consecutive rounds of UV-photocleavable reporter hybridization. An alternative method with similar features is the Xenium technology from 10× Genomics, which also achieves spatially resolved protein detection alongside transcript measurement at single-cell resolution (106). Recently, spatial CITE-seq was introduced, which enables co-indexing of transcriptome and epitopes using antibody-derived DNA tags. It allows detection of at least 100 to 200 proteins (107). For metal-labeled antibodies, also multiplexed detection using X-ray fluorescence was demonstrated, potentially enabling rapid, multiplexed 3D analysis of tissues (108). In summary, multiple HMTI methods offer distinct advantages and challenges. Clinical implementation will require additional technology development to match clinical requirements, validation of robustness and methods of sample processing, and downstream data analysis. Furthermore, there are emerging technologies focused on metabolic imaging such as multiphoton redox and stimulated Raman scattering imaging (42, 44). However, these technologies are still in the early stages of development.

Computational Analysis

The current generation of HMTI technologies can image large areas of tissue at single-cell resolution, resulting in enormous amounts of data. To benefit patients, multichannel images must be reproducibly processed to extract and quantify features relevant to precision oncology decisions. Irrespective of the platform, HMTI data must be subjected to common steps of processing, image segmentation into cells, and feature extraction, which includes retrieval of biomarker information (Fig. 3). Prior to processing, interactive tools such as the napari image viewer, cytoviewer, or histoCAT can be used to visually evaluate patient sample images (109–111). Processing steps enhance the quality of the images using techniques such as noise reduction and background subtraction. Mass spectrometry–based techniques acquire high-plex data in a single step, but the cyclic fluorescence imaging techniques rely on multiple rounds of low-plex imaging and images must be registered to create a composite image. Furthermore, fluorescence-based images must be corrected for uneven illumination and additional sources of noise (112). To enable comparison of samples, data normalization steps are required to adjust for differences in experimental and imaging conditions (113).

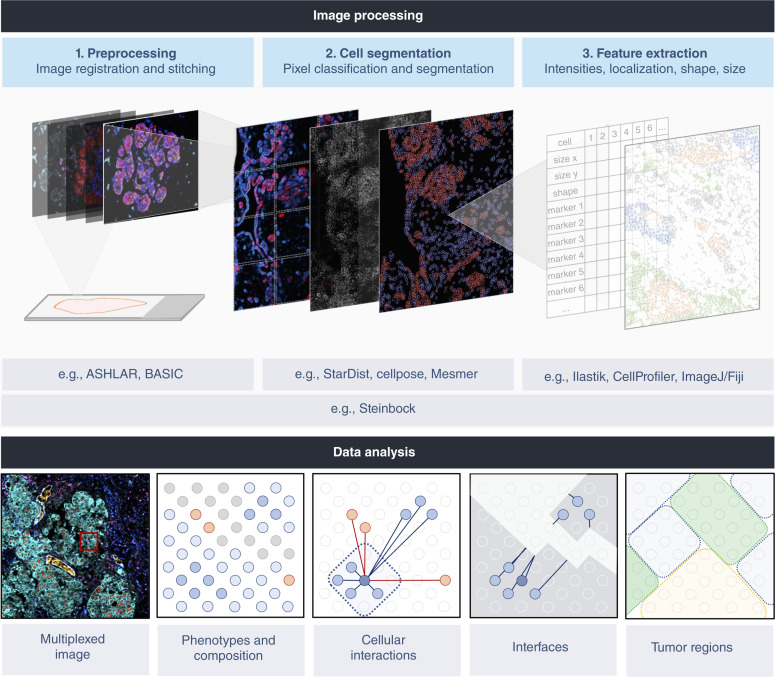

Figure 3.

Computational pipelines for multiplexed image processing. Multichannel images are computationally processed to identify and quantify features relevant to precision oncology decisions. Irrespective of platform, analysis of HMTI data shares common steps of preprocessing, cell segmentation, and feature extraction. For multiplexed imaging methods requiring multiple rounds of acquisition, image registration is needed to align different images. Imaging large tissue regions additionally requires stitching and illumination correction to avoid intensity discontinuity effects. This processing step generates a TIFF file that is input for pixel classification based on manual training or use of deep learning networks for subsequent cell segmentation. Features of individual cells can then be extracted including marker intensities, shape, and size. Downstream data analysis to visualize tissue images and to evaluate phenotypes, cellular interactions, and spatial features of the TME can be performed using a variety of computational tools. BioRender.com

Image segmentation is used to identify cell borders. Segmentation is either achieved by manually training a classifier such as available in Ilastik, CellProfiler, or ImageJ/Fiji to identify pixels as nuclear and membrane or by using fully automated deep learning methods such as StarDist (114), Cellpose (115), or Mesmer (116). When trained on large datasets, the deep learning algorithms can achieve high levels of accuracy and robustness across many cancer types, making them attractive for clinical workflows. Once segmentation has been achieved, tissue features, including cell shape, location, size, and mean marker intensities are extracted from the data. In this way, the presence of drug targets, active signaling pathways, and metabolic states in individual cells can be computed. Cells that express similar markers are grouped into phenotype clusters, which allows identification of different tumor and non-tumor cell subpopulations. In doing so, features of individual cells can be summarized in the form of cellular compositions. In addition, spatial context between different cell types or phenotypes can be computed and used to guide clinical decisions. Instead of guided analysis, these features can also be used for data-driven approaches aiming to stratify patients or to identify novel biomarkers using machine learning-based methods given available clinical features. In all scenarios, it is essential to co-analyze proper controls, e.g., referencing cohort data as a baseline, to determine the biomarker signal intensities between different cell types or between different samples.

Various tools and packages are available for analysis of single-cell and spatial information derived from HMTI. Most software has been specifically designed for particular HMTI platforms and compatibility with other analysis methods is often limited. Code-based analysis methods provide flexibility and allow for integration of various analytical approaches. Examples of such methods include Squidpy (117), Giotto (118), and the imcRtools and cytomapper packages (119, 120). Moreover, some individual tools have been combined to create more streamlined image-processing pipelines; examples are MCMICRO (121) and steinbock (120). To date, there is no software that meets the regulatory requirements for medical device software for clinical use.

File sizes and data handling are computational factors that will be challenging during implementation of HMTI into routine clinical practice. Whole-slide H&E images at 20× magnification result in a few gigabytes of data, and file sizes drastically increase with multiplexity (122). A whole slide 40-plex immunofluorescence image at 20× magnification typically results in tens to hundreds of gigabytes of data. In addition, multi-round imaging techniques have computational costs due to necessary image alignment steps. Metal-labeled antibody approaches are usually not used for whole-slide imaging given the slower imaging speed resulting in file sizes in the range of a few to tens of megabytes per mm2. Hence, effective image data life cycle management will be crucial during the transition to clinical use. Clinical data must be stored at least 10 years to meet regulatory demands (123–125), although those rarely accessed data can be stored in slow storage media. While the acquisition and storage of high numbers of whole-slide H&E and IHC images are routinely implemented in clinics, the necessary compute power to perform the above described HMTI data analysis steps are not routinely available. Hospitals that built compute infrastructure for digital pathology approaches will have an advantage since these infrastructures provide a template and can be used for HMTI data management and processing (122, 126).

The Future of Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment

The Potential of Highly Multiplexed Imaging for Precision Oncology

HMTI provides a wealth of information about the molecular and cellular composition of tissues including expression levels of drug targets and cell state markers, cellular morphology and composition, intercellular interactions and communication, and overall tissue architecture (Fig. 1; ref. 127). HMTI can inform on drug development at preclinical and clinical stages and can support patient stratification for prognostic or therapeutic purposes (Fig. 4; ref. 128). The following paragraphs aim to provide a comprehensive overview of the potential applications and implications of HMTI in precision oncology.

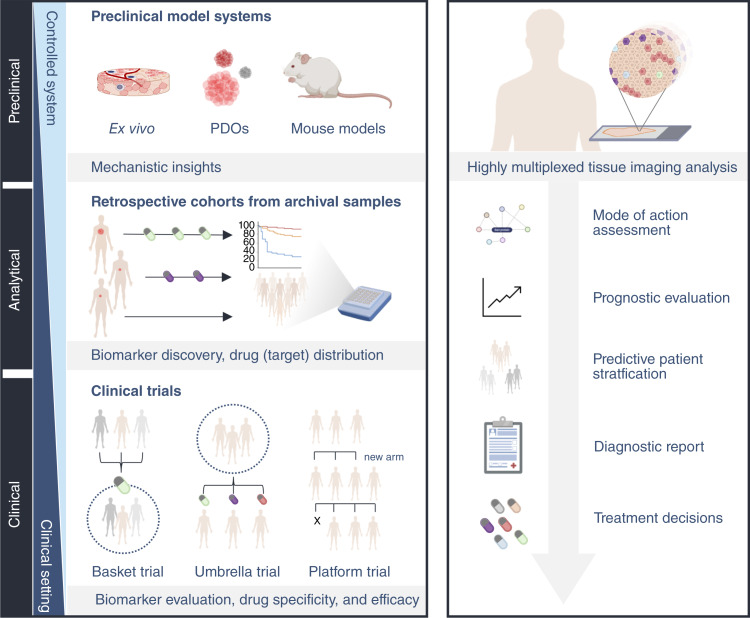

Figure 4.

The envisioned role of highly multiplexed tissue imaging in translational cancer research (left) and clinical practice (right). HMTI assays can be used to analyze preclinical model systems, including ex vivo cultures, patient-derived organoids, and mouse models, which serve as essential tools to study complex cellular systems in a controlled manner. Leveraging HMTI assays, it is possible to validate findings in retrospective cohorts of patients with known treatment response, survival, and relapse information. HMTI will facilitate precision oncology at various stages in routine clinical practice. This type of assay can be used to assess a drugs’ mode of action, to classify and stage tumors for prognostic evaluation, to predict treatment outcomes of a given therapy, to guide therapy decisions based on a comprehensive diagnosis, to evaluate pharmacodynamics, and to monitor tumor progression or regression during therapy. (Created with BioRender.com.)

Biomarker Discovery

HMTI technologies can analyze a large set of proteins relevant to a disease process, thus supporting the inference of disease biomarkers. Two general types of biomarkers can be used for HMTI-guided precision oncology: the first are those that can be readily interpreted by an oncologist, such as factors involved in oncogenic signaling pathways or a cell phenotype that could be targeted by a drug. The second are data-driven biomarkers identified through analyses of multiple markers in images derived from large patient cohorts, such as complex combinations of image parameters identified by deep-learning approaches as predictive of treatment success (129, 130). To identify biomarkers by HMTI, one must have access to cohorts that enable a specific clinical question to be addressed. In a first step, typically data-driven analysis of retrospective clinical cohorts is used to reveal tissue characteristics that differ between defined patient groups, including responders and nonresponders, and the biological influence of prior systemic or local therapies on the cellular tumor composition (131–133). HMTI can also be used to identify tissue features related to drug resistance, potentially helping to identify additional treatment options that overcome resistance (134). Reanalysis of failed clinical trials by HMTI can potentially rescue failed drugs by improved patient stratification and support future trials by only recruiting the most suitable patients. To validate a candidate biomarker, independent cohorts must be analyzed leveraging HMTI for patient stratification. The initial discovery phase may reveal nonrelevant protein targets. These might be replaced during diagnostic test development with informative and/or redundant markers to solidify the initial observations or reduce the number of markers needed.

Drug Response

During drug development, HMTI can be used for drug target discovery and validation (128). HMTI allows the visualization and quantification of drug targets in tumor and healthy tissues, providing insight into drug specificity and effectiveness. In clinical trials, HMTI-based analyses of patient samples pre- and post-treatment can yield a quantitative readout of the efficacy of tested drug doses, provide information about off-target effects, and shed light on heterogeneity of biological drug response (131–133). In addition, HMTI analyses could reveal how a drug influences tumor and normal cell types, enabling us to anticipate and mitigate potential side effects and provide insight into mechanisms of drug actions and compensatory mechanisms. HMTI could also support objective response assessment in clinical trials. Response assessment for solid tumors currently relies on radiographic imaging to assess tumor size (135), and flow cytometry or microscopy to assess immunotherapy and treatment responses in liquid tumors (136). In parallel, biopsy samples could be analyzed by HMTI to evaluate the in situ treatment response in more detail in clinical trial settings. The resulting data could be used to optimize ongoing treatment or to guide selection of novel treatment options. Importantly, HMTI data may allow the identification of patients who will benefit from a particular therapy, thereby helping to guide clinical trial designs and increasing the chance of their success by recruiting the most suitable patients.

Drug Distribution

HMTI may also be used to investigate drug biodistribution and effects on cells and their microenvironment, aiding in the optimization of drug formulations and delivery strategies. For this purpose, biologicals can often directly be labeled with a reporter molecule or tags detectable by specific antibodies without loss of functionality (137). For instance, fluorescently labeled antibodies directed against therapeutic monoclonal antibodies like trastuzumab can be used, and IMC can directly detect metal-based drugs such as cisplatin (138). Alternatively, auto-fluorescent drugs like doxorubicin may be directly detected in clinical tissue samples; the concentration of this drug has been associated with distance from blood vessels (139). A major challenge is the impact of tissue processing on drug metabolites in FFPE samples, leading to a preference for drug distribution studies in fresh frozen tissue samples. However, when not relying on the detection of metabolites, such as for therapeutic monoclonal antibody or metal-based drugs, HMTI techniques may be readily applicable to clinical FFPE samples. Thus, samples from large retrospective cohorts could be used to quantify and understand drug (or drug target) distribution. This analysis would elucidate concentrations at which cells and their neighborhood absorb the drug and how this influences biodistribution. Monitoring of drugs like doxorubicin, which rely on autofluorescent properties, may be affected by metabolites with altered fluorescent properties or autofluorescence of the tissue and necessitate additional validation steps.

Treatment Decisions

The strength of HMTI is that it leverages the same samples and workflow employed in clinical pathology (129). Like traditional IHC, analysis of standard biomarkers by HMTI could be used to inform first-, second-, and third-line treatment decisions as shown in breast cancer where levels of hormone receptors and HER2 measured by IHC and HMTI are highly correlated (48). Compared to IHC, though many HMTI methods offer broader dynamic ranges enhancing quantitative readouts. In many cancer types, such as lung cancer, current guidelines necessitate that many markers are evaluated to support the choice among available standard treatments (140). However, little biopsy material can complicate this analysis using standard single-plex IHC, since this approach requires consecutive sections. HMTI by contrast provides this comprehensive information from analysis of a single tissue section. Analyzing multiple markers on the same section can also facilitate integrating spatial relationships between different markers. Once standard-of-care treatments are exhausted, oncologists prescribe treatments or interventions that fall outside the established clinical treatment guidelines. HMTI provides information beyond the standard clinical evaluation: It offers insight into alternative treatment options that might be successful. Patients may then be treated off-label or enrolled in specific clinical trials aimed at evaluating these treatments in practical clinical settings. Gene panel analysis of tumors has become routine in these settings (141). Although identification of potential druggable gene alterations has improved treatment success, these are often not reflected on the protein (i.e., drug target) level. Further, a considerable number of druggable gene alterations may be identified. We have shown that HMTI can be used to identify those gene alterations that affect oncogenic processes and that HMTI data can be used to prioritize treatments suggested by genomic analysis making it highly complementary to gene-panel analysis approaches (142). Once fully established, HMTI could provide comprehensive personalized tumor analysis that will inform selection of tailored treatments.

Virtual Clinical Trials

Like IHC, HMTI can be used for biological interpretation of markers, but the true power of HMTI lies in its ability to capture high-dimensional multiscale and multivariate data. A possible application of HMTI is the digitization of hundreds of thousands of available biobanked patient samples. These images and associated clinical data would create an invaluable resource for researchers and clinicians. If proper standard marker panels and standardized processes were implemented, such a resource could support the execution of “virtual clinical trials” in which retrospective patient data are used to simulate and model different treatment scenarios to optimize clincial treatment strategies (143).

The Path of Highly Multiplexed Imaging to the Clinic

Prior to implementation of HMTI as a diagnostic tool, identification of diagnostic biomarkers aligning with multiplexed systems is essential. Although merging routine clinical biomarkers into a multiplexed framework may yield benefits, showcasing features that go beyond current standards will be necessary to trigger implementation of HMTI systems into routine clinical practice. Currently, all existing HMTI methods are limited to research use only, where they have proven to be valuable in advancing our understanding of complex disease mechanisms. The next step will be to broadly implement them in clinical trials to investigate their benefits for patients. Already there have been notable advances in commercial solutions for cyclic immunofluorescence and IMC, and these are now routinely used in clinical trials. To enable integration of HMTI into precision oncology diagnostics, regulatory approval as an in vitro diagnostic for assays, technology, and software is essential (144). A few laboratories have developed tests based on HMTI that are commercially available, such as the TissueCypher, a nine-plex test that identifies patients with Barrett’s esophagus who are likely to progress into cancer (145), but these tests are not yet approved for routine clinical diagnostics.

The path toward clinical implementation involves a design control process to ensure that the device meets the user needs, intended purpose, and the specific requirements using predefined acceptance criteria and verification steps (144). In the case of HMTI, each individual antibody clone included in the panel, as well as combinations of antibodies and all of them together must be validated. Moreover, the data analysis pipeline, from image processing to report generation, must be developed under life cycle requirements established for medical device software. This encompasses documented planning, requirements specification, design, verification, and long-term maintenance of the software to guarantee reproducible and consistent results. How the software is integrated with the laboratory system and problem-resolution processes at all stages must also be addressed. Once the design is finalized, the manufacturer must demonstrate the safety and performance of the HMTI device through a performance evaluation report. This report assesses analytic performance, scientific validity, and clinical performance (146).

For analytic performance validation, accuracy (i.e., results relative to the truth or current standard assay), precision and reproducibility (i.e., consistency of assay results), sensitivity and specificity (i.e., the ability of the assay to correctly identify true positive and true negative results, respectively), and limit of detection must be determined (146). The primary objective of the analytical performance evaluation is to ensure that the assay performs accurate and reliable measurement of each analyte over an extended period of time and ideally across geographic locations. HMTI offers a unique approach to antibody utilization, allowing for the use of different antibodies against the same target or complementary marker sets for a cell phenotype of interest. This approach has the potential to enhance robustness and reproducibility, even across different hospitals. Furthermore, HMTI will enable the implementation of antibody sets to assess and evaluate tissue processing and quality, thereby adding another layer of confidence to the obtained results. For many antibodies used in HMTI, equivalents exist in clinical diagnostic labs for IHC assays, and thus individual IHC assays will serve as the reference standard for HMTI assays with a multiplexed antibody panel. Cyclic staining methods will require additional verification of antigen stability, achieved by varying the order of antibody addition and re-imaging the same target across multiple cycles.

To demonstrate scientific validity, a relationship between a specific analyte and a medical condition or a treatment response must be shown. Generally, scientific literature is cited to support the relationship. As such, scientific validity bridges the gap between analytic performance validation, which focuses on the analyte itself, and the clinical performance evaluation, which centers on the test’s capability to achieve its intended purpose. For example, in HMTI, intended use could be to determine the activation status of signaling pathways targeted by drugs or to correctly stratify patients as responders and nonresponders.

To demonstrate clinical performance, patient cohort samples must be analyzed using the HMTI assay and associated clinical data can be used to evaluate diagnostic sensitivity and specificity (147). Even though clinical performance can be demonstrated with retrospective cohorts, the gold standard for clinical validity lies in prospective clinical trials. Two types of trials can be conducted for HMTI tests (148, 149). First, predetermined endpoints, such as correct stratification of patients into responder versus nonresponder groups or identification of proper standard-of-care treatment, can be used in classical predictive clinical trials. Second, to evaluate the clinical utility of an HMTI assay to identify optimal personalized treatment, innovative clinical trial designs will need to be employed. Examples of such designs include umbrella trials, which investigate multiple targeted therapies for a single cancer type, and platform trials, which explore multiple targeted therapies for multiple cancer types (Fig. 4). In these trials, one patient group will receive treatment based on the current standard of care, whereas the other group will be treated according to recommendations from analysis of HMTI data. An alternative to these trial types are N-of-1 trials in which an individual patient serves as the control and the effects of a given precision treatment on the disease are observed (150, 151). Importantly, clinical performance evaluation is a continuous process with constant monitoring of assay performance through post-market surveillance follow-up.

Taken together, the journey of implementing new technologies into clinical practice involves several critical steps. While HMTI technologies are not yet part of routine clinical care, genetic testing stands as an example of how these methods can transition toward routine clinical practice. Here, scientific validity took root with landmark projects like TCGA, demonstrating the role of genetic alterations in cancer using various technologies including next-generation sequencing (NGS; ref. 152). Subsequent studies revealed associations between patient outcomes and specific mutations, such as activating mutations in the EGFR gene which serve as predictive biomarkers for response to tyrosine kinase inhibitors (153, 154). Advancing further, NGS assays for detecting genetic alterations in solid tumors and targeted sequencing panels for comprehensive genomic profiling were validated. One notable outcome of this progress was the FDA approval in 2017 of the genomic profiling test developed by Foundation Medicine (155), successfully demonstrating clinical performance (156). Today, genetic testing is recommended in the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines for targeted therapy selection in specific cancer indications such as lung cancer.

In the clinical setting, time is a critical factor, and more rapid diagnosis results in faster initiation of treatment, ultimately reducing patient mortality (157). Pathology reports are on average provided within 2 days after surgery or biopsy, with treatment decisions usually made within a week (158). Decisions based on next-generation sequencing may take a few days up to 3 weeks (159) and to be compatible with clinical requirements, HMTI methods should ideally require a similar time frame. Therefore, for broad uptake, HMTI methods must be fully automated, from sample processing to clinical report generation. Within the Tumor Profiler observational trial, we showed that it is possible to generate clinical reports based on IMC within 3 days (142). To ensure successful clinical implementation, oncologists will need to be trained to facilitate the translation of complex HMTI findings into clinical practice. Molecular tumor boards at cancer centers bring together experts from diverse fields, including pathologists, molecular biologists, bioinformaticians, geneticists, and clinicians, to interpret genetic test results and implement genetics-guided cancer therapies. As HMTI is implemented, tumor boards will be instrumental in interpretation of data derived from these imaging modalities. The appropriate format for HMTI data presentation must be determined so that these data can be interpreted with all other available patient information to maximize patient benefit.

Future Perspectives

Cancer is a complex disease, unique to each individual, and it remains a challenge to match the right treatment combination to the right patient. Multiplexed imaging techniques offer a promising avenue for precision oncology as these techniques provide much more detailed information than traditional IHC methods while using the same samples and similar workflows. While integration with spatial transcriptomics and other omics methods may provide interesting biological insights in the future, it is worth noting that HMTI on its own has already begun to be used in specific clinical contexts. For example, multiplexed chromogenic assays that rely on tyramide signal amplification of a six-plex panel (PD-1, PD-L1, CD8, FOXP3, CD68, and a tumor marker) are being successfully used in some clinical laboratories in the context of immunotherapy (86, 160). IMC has been successfully implemented to support treatment decisions in the observational Tumor Profiler study (142). These successes suggest a trajectory toward the integration of HMTI into broader clinical workflows. It appears increasingly likely that future complementary or companion diagnostic tests will be based on a multiplexed approach. Nevertheless, prior to successful clinical implementation, the need for specialized instruments, additional training for pathologists, and additional diagnostic time and expenses as well as method and software development and validation must be addressed. Therefore, H&E and single-plex IHC will not be replaced by HMTI assays in the foreseeable future. However, as the number of molecularly targeted therapies increases, with adoption of digital pathology workflows in the clinical laboratories and with the emergence of novel biomarkers from HMTI research, we expect that HMTI assays will emulate the path of cancer genomics and become an indispensable tool for pathologists and oncologists within this decade.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for Natalie de Souza, Stefanos Voglis, Stéphane Chevrier, Jana Fischer, and Simon Häfliger for thorough and critical reading of the article. We apologize to the authors of the publications that could not be cited in the scope of this review. Data on clinical trials were obtained from the U.S. National Library of Medicine’s Database ClinicalTrials.gov (RRID:SCR_002309). B. Bodenmiller was funded by three SNSF grants (SNF project grant 310030_205007, SNF R’Equip grant 316030_213512, Innosuisse Bridge Grant 40B2-0_203478), an SPHN/PHRT Swiss Precision Oncology National Data Stream grant, Tumor Profiler Center funding, Skintegrity funding, Comprehensive Cancer Center Zürich Precision Oncology project funding, an NIH grant (UC4 DK108132), and the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Program under the ERC grant agreement no. 866074 (“Precision Motifs”).

Authors’ Disclosures

B. Bodenmiller reports grants from SNSF, NIH, SPHN/PHRT, ERC, Tumor Profiler Center, Skintegrity, and Comprehensive Cancer Center Zürich during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Standard BioTools outside the submitted work; in addition, B. Bodenmiller has a patent for EP23214783 pending, a patent for EP21156709.4 pending, a patent for EP20152569.8 pending, a patent for EP19168471.1 pending, and a patent for WO2015128490 pending; and B. Bodenmiller co-founded and is a shareholder and member of the board of Navignostics, a highly multiplexed tissue imaging precision oncology spin-off company. No disclosures were reported by the other authors.

References

- 1. Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 2011;144:646–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Vandereyken K, Sifrim A, Thienpont B, Voet T. Methods and applications for single-cell and spatial multi-omics. Nat Rev Genet 2023;24:494–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jordan VC, Collins MM, Rowsby L, Prestwich G. A monohydroxylated metabolite of tamoxifen with potent antioestrogenic activity. J Endocrinol 1977;75:305–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. ICGC/TCGA Pan-Cancer Analysis of Whole Genomes Consortium . Pan-cancer analysis of whole genomes. Nature 2020;578:82–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhong L, Li Y, Xiong L, Wang W, Wu M, Yuan T, et al. Small molecules in targeted cancer therapy: advances, challenges, and future perspectives. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2021;6:201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dillman RO. Magic bullets at last! finally—approval of a monoclonal antibody for the treatment of cancer!!! Cancer Biother Radiopharm 1997;12:223–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Baselga J, Tripathy D, Mendelsohn J, Baughman S, Benz CC, Dantis L, et al. Phase II study of weekly intravenous trastuzumab (Herceptin) in patients with HER2/neu-overexpressing metastatic breast cancer. Semin Oncol 1999;26(4 Suppl 12):78–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Allison JP, Hurwitz AA, Leach DR. Manipulation of costimulatory signals to enhance antitumor T-cell responses. Curr Opin Immunol 1995;7:682–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhao B, Zhao H, Zhao J. Efficacy of PD-1/PD-L1 blockade monotherapy in clinical trials. Ther Adv Med Oncol 2020;12:1758835920937612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Seth R, Messersmith H, Kaur V, Kirkwood JM, Kudchadkar R, McQuade JL, et al. Systemic therapy for melanoma: ASCO guideline. J Clin Oncol 2020;38:3947–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ali SA, Shi V, Maric I, Wang M, Stroncek DF, Rose JJ, et al. T cells expressing an anti-B-cell maturation antigen chimeric antigen receptor cause remissions of multiple myeloma. Blood 2016;128:1688–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hurwitz H, Fehrenbacher L, Novotny W, Cartwright T, Hainsworth J, Heim W, et al. Bevacizumab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 2004;350:2335–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tetzlaff MT, Pattanaprichakul P, Wargo J, Fox PS, Patel KP, Estrella JS, et al. Utility of BRAF V600E immunohistochemistry expression pattern as a surrogate of BRAF mutation status in 154 patients with advanced melanoma. Hum Pathol 2015;46:1101–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yan W-H, Jiang X-N, Wang W-G, Sun Y-F, Wo Y-X, Luo Z-Z, et al. Cell-of-origin subtyping of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma by using a qPCR-based gene expression assay on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues. Front Oncol 2020;10:803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Massard C, Michiels S, Ferté C, Le Deley MC, Lacroix L, Hollebecque A, et al. High-throughput genomics and clinical outcome in hard-to-treat advanced cancers: results of the MOSCATO 01 trial. Cancer Discov 2017;7:586–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chapman PB, Hauschild A, Robert C, Haanen JB, Ascierto P, Larkin J, et al. Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. N Engl J Med 2011;364:2507–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Köhler J, Schuler M. Afatinib, erlotinib and gefitinib in the first-line therapy of EGFR mutation-positive lung adenocarcinoma: a review. Onkologie 2013;36:510–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mellinghoff IK, van den Bent MJ, Blumenthal DT, Touat M, Peters KB, Clarke J, et al. Vorasidenib in IDH1- or IDH2-mutant low-grade glioma. N Engl J Med 2023;389:589–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lu S, Stein JE, Rimm DL, Wang DW, Bell JM, Johnson DB, et al. Comparison of biomarker modalities for predicting response to PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint blockade: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol 2019;5:1195–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Antonelli M, Poliani PL. Adult type diffuse gliomas in the new 2021 WHO classification. Pathologica 2022;114:397–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lin J-R, Wang S, Coy S, Chen Y-A, Yapp C, Tyler M, et al. Multiplexed 3D atlas of state transitions and immune interaction in colorectal cancer. Cell 2023;186:363–81.e19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lin J-R, Chen Y-A, Campton D, Cooper J, Coy S, Yapp C, et al. High-plex immunofluorescence imaging and traditional histology of the same tissue section for discovering image-based biomarkers. Nat Cancer 2023;4:1036–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gennari A, André F, Barrios CH, Cortés J, de Azambuja E, DeMichele A, et al. ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for the diagnosis, staging and treatment of patients with metastatic breast cancer. Ann Oncol 2021;32:1475–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Arshad OA, Danna V, Petyuk VA, Piehowski PD, Liu T, Rodland KD, et al. An integrative analysis of tumor proteomic and phosphoproteomic profiles to examine the relationships between kinase activity and phosphorylation. Mol Cell Proteomics 2019;18(8 Suppl 1):S26–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ritter CA, Perez-Torres M, Rinehart C, Guix M, Dugger T, Engelman JA, et al. Human breast cancer cells selected for resistance to trastuzumab in vivo overexpress epidermal growth factor receptor and ErbB ligands and remain dependent on the ErbB receptor network. Clin Cancer Res 2007;13:4909–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Long GV, Stroyakovskiy D, Gogas H, Levchenko E, de Braud F, Larkin J, et al. Combined BRAF and MEK inhibition versus BRAF inhibition alone in melanoma. N Engl J Med 2014;371:1877–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kato Y, Lambert CA, Colige AC, Mineur P, Noël A, Frankenne F, et al. Acidic extracellular pH induces matrix metalloproteinase-9 expression in mouse metastatic melanoma cells through the phospholipase D-mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling. J Biol Chem 2005;280:10938–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. LeBleu VS, O’Connell JT, Gonzalez Herrera KN, Wikman H, Pantel K, Haigis MC, et al. PGC-1α mediates mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative phosphorylation in cancer cells to promote metastasis. Nat Cell Biol 2014;16:992–1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ohta T, Iijima K, Miyamoto M, Nakahara I, Tanaka H, Ohtsuji M, et al. Loss of Keap1 function activates Nrf2 and provides advantages for lung cancer cell growth. Cancer Res 2008;68:1303–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Komurov K, seng J-T, Muller M, Seviour EG, Moss TJ, Yang L, et al. The glucose-deprivation network counteracts lapatinib-induced toxicity in resistant ErbB2-positive breast cancer cells. Mol Syst Biol 2012;8:596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wangpaichitr M, Wu C, Li YY, Nguyen DJM, Kandemir H, Shah S, et al. Exploiting ROS and metabolic differences to kill cisplatin resistant lung cancer. Oncotarget 2017;8:49275–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Liu Y-N, Yang J-F, Huang D-J, Ni H-H, Zhang C-X, Zhang L, et al. Hypoxia induces mitochondrial defect that promotes T cell exhaustion in tumor microenvironment through MYC-regulated pathways. Front Immunol 2020;11:1906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Horská A, Barker PB. Imaging of brain tumors: MR spectroscopy and metabolic imaging. Neuroimaging Clin N Am 2010;20:293–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Brigandi RA, Zhu J, Murnane AA, Reedy BA, Shakib S. A phase 1 randomized, placebo-controlled trial with a topical inhibitor of stearoyl-coenzyme A desaturase 1 under occluded and nonoccluded conditions. Clin Pharmacol Drug Dev 2019;8:270–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. de Groot S, Vreeswijk MPG, Welters MJP, Gravesteijn G, Boei JJWA, Jochems A, et al. The effects of short-term fasting on tolerance to (neo) adjuvant chemotherapy in HER2-negative breast cancer patients: a randomized pilot study. BMC Cancer 2015;15:652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dorff TB, Groshen S, Garcia A, Shah M, Tsao-Wei D, Pham H, et al. Safety and feasibility of fasting in combination with platinum-based chemotherapy. BMC Cancer 2016;16:360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Enomoto K, Sato F, Tamagawa S, Gunduz M, Onoda N, Uchino S, et al. A novel therapeutic approach for anaplastic thyroid cancer through inhibition of LAT1. Sci Rep 2019;9:14616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Halford SER, Jones P, Wedge S, Hirschberg S, Katugampola S, Veal G, et al. A first-in-human first-in-class (FIC) trial of the monocarboxylate transporter 1 (MCT1) inhibitor AZD3965 in patients with advanced solid tumours. J Clin Oncol 2017;35(Suppl 15):2516. [Google Scholar]