Abstract

Aims

The evidence base within trauma and orthopaedics has traditionally favoured quantitative research methodologies. Qualitative research can provide unique insights which illuminate patient experiences and perceptions of care. Qualitative methods reveal the subjective narratives of patients that are not captured by quantitative data, providing a more comprehensive understanding of patient-centred care. The aim of this study is to quantify the level of qualitative research within the orthopaedic literature.

Methods

A bibliometric search of journals’ online archives and multiple databases was undertaken in March 2024, to identify articles using qualitative research methods in the top 12 trauma and orthopaedic journals based on the 2023 impact factor and SCImago rating. The bibliometric search was conducted and reported in accordance with the preliminary guideline for reporting bibliometric reviews of the biomedical literature (BIBLIO).

Results

Of the 7,201 papers reviewed, 136 included qualitative methods (0.1%). There was no significant difference between the journals, apart from Bone & Joint Open, which included 21 studies using qualitative methods, equalling 4% of its published articles.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that there is a very low number of qualitative research papers published within trauma and orthopaedic journals. Given the increasing focus on patient outcomes and improving the patient experience, it may be argued that there is a requirement to support both quantitative and qualitative approaches to orthopaedic research. Combining qualitative and quantitative methods may effectively address the complex and personal aspects of patients’ care, ensuring that outcomes align with patient values and enhance overall care quality.

Keywords: Qualitative, Bibliometric review, Person-centred care, Qualitative methods, orthopaedic and trauma, orthopaedic research, clinicians, patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs), randomized controlled trials, hip and knee arthroplasties, orthopaedic and sports medicine, hip and knee arthroplasties, National Joint Registry, healthcare professionals’

Introduction

A central tenet of healthcare is the use of evidence-based research to inform clinical practice.1 Continual development and research are necessary to improve care quality and optimize outcomes for service users. Clinical research methods can be divided into two main categories, quantitative and qualitative (Table I).2 Quantitative research collects numerical data and analyzes it using statistical analysis, producing objective, empirical data that can be measured and expressed to test hypotheses, make predictions, or identify patterns.3 Qualitative research collects non-numerical data, such as words or images. It explores subjects’ experiences, opinions, or attitudes.4

Table I.

Differences of quantitative versus qualitative research.

| Variable | Quantitative research | Qualitative research |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose | Answer “how many/much” or “how often” questions | Answer “why” questions |

| Data type | Number/ statistical results | Observations, words, symbols, etc |

| Approach | Measure and test, fixed and universal, “factual” | Observe and interpret, dynamic and subjective |

| Analysis | Statistical analysis | Grouping of common data/non-statistical analysis |

Both methods are required in research when exploring multifaceted and complex questions surrounding patient care and understanding the impact care provided has on individual patients and the broader patient population.5 Despite recognizing the value of qualitative approaches in specific areas, clinical research in trauma and orthopaedics overwhelmingly utilizes quantitative methods.6 Incorporating both quantitative and qualitative methodologies is vital within trauma and orthopaedics. These two approaches are distinct in the types of questions they seek to address.7 For instance, quantitative methods (such as randomized controlled trials (RCTs)) are powerful tools to assess the effects of interventions and treatments. However, critical limitations arise when such studies exclusively rely on quantitative methodologies, as they overlook the subjective experiences of patients undergoing these interventions and can fail to gauge their perceived success.8 These specific research inquiries can only be effectively tackled through qualitative methodologies. Qualitative research diverges from quantitative by drawing upon patients’ narratives, opinions, and emotions as primary data sources. This approach enhances the pertinence and robustness of findings while pinpointing practical ways to implement findings in clinical practice.9,10 To establish a culture of evidence-based practice in the field, it is imperative to recognize that both quantitative and qualitative research traditions make indispensable contributions.11 These two methods are complementary, and their combined application is essential to enable comprehensive explorations and enhancements of all dimensions of care quality.

Orthopaedic research has been criticized regarding its alignment with the clinical priorities and needs of patients.12,13 In response, there has been concerted efforts to involve public and patients in the inception, design, execution, and dissemination of research, exemplified by initiatives like The James Lind Alliance Priority Setting Partnership14 and research funders such as the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR),15 which emphasize the need to actively involve patients and public in research design and conduct.

Despite these advancements, qualitative studies are scarce in prominent orthopaedic journals. It may be argued that qualitative methodologies, to a certain extent, remain largely overlooked or considered relevant only to nursing and allied professional-related roles and topics. To explore this, a comprehensive bibliometric search took place to identify the amount of qualitative research published in orthopaedic journals.16

This bibliometric search was conducted and reported in accordance with the preliminary guideline for reporting bibliometric reviews of the biomedical literature (BIBLIO).17

Methods

A comprehensive bibliometric search occurred in March 2024 by two independent researchers (LEM, TWW). The top 16 orthopaedic and sports medicine journals from 2023 were identified, according to a combination of the Thomson Reutors impact factor and SCImago Journal Ranking (Table II).18 Each journal’s full online archives and the databases, CINAHL, Cochrane, and PubMed were searched using the search terms “qualitative, qualitative approach, qualitative methods”. The search included all available published papers in the journals, regardless of date published. The searches were not limited by historical time constraints or geographical limitations. The decade each eligible article was published was recorded to enable a comparison between decades and identify if there is an increase in numbers of qualitative research published over time. All included journals published articles in English. Ethical approval was not required to undertake this bibliometric search and review.

Table II.

Included top orthopaedic and sports medicine journals based on impact factor and SCImago journal ranking.

| No. | Impact factor (2023) | Journal title | SJR |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 18.6 | British Journal of Sports Medicine | 1 |

| 2 | 7.1 | American Journal of Sports Medicine | 3 |

| 3 | 4.6 | The Bone & Joint Journal | 5 |

| 4 | 4.435 | Journal of Arthroplasty | 7 |

| 5 | 4.33 | Arthroscopy - Journal of Arthroscopic and Related Surgery | 8 |

| 6 | 4.578 | Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery | 9 |

| 7 | 7.0 | Osteoarthritis and Cartilage | 10 |

| 8 | 3.8 | Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy | 11 |

| 9 | 3.925 | Acta Orthopedica | 17 |

| 10 | 5.853 | Bone & Joint Research | 18 |

| 11 | 4.16 | Spine Journal | 19 |

| 12 | 2.8 | Bone & Joint Open | 24 |

| 13 | 4.837 | Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research | 38 |

SJR, SCImago Journal Ranking.

The Journal of Sport and Health Science, Sports Medicine, and the Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle were excluded from the results (Table III), as the qualitative research they included were unrelated to the trauma and orthopaedic speciality.

Table III.

Journals excluded from search.

| No. | Impact factor (2023) | Journal title | SJR |

|---|---|---|---|

| 14 | 9.8 | Sports Medicine | 2 |

| 15 | 8.9 | Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle | 4 |

| 16 | 13.077 | Journal of Sport and Health Science | 6 |

SJR, SCImago Journal Ranking.

The title and abstract of search results from each journal were manually screened against the eligibility criteria (Table IV). The full text of studies identified for potential inclusion were retrieved and examined against the eligibility criteria.

Table IV.

Eligibility criteria.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Article focused on trauma and orthopaedic surgical specialities. | Articles focusing on other clinical specialities. |

| Research using a qualitative methodology or approach at any point in the study process, including nominal group, focus group, open-ended questionnaire, interviews, and data collected in participants’ own words. | Research solely using patient-reported outcome measures as a form of participant feedback data. |

| Research using either patients or clinicians or healthy volunteers in participant sample. | |

| Systematic literature reviews, scoping reviews, editorial, and opinion articles using or discussing qualitative research or qualitative methods. |

Eligible studies included qualitative approaches or methodologies at any point in study processes. Literature reviews and editorials/opinion pieces using or discussing qualitative research were also identified. There was no restriction on method of qualitative approach, nor when it featured within the study. The qualitative methodology could be used for initial study design or within the main body of study data collection.

Notably, the word “qualitative” often had different meanings. For example, some papers used the term “qualitative methods” when describing subjective clinical assessments of an injury, imaging, or anatomy. Systematic literature reviews frequently used the term “qualitative methods” to describe analysis of search results by researchers. These alternative meanings of “qualitative” meant each journal initially identified large lists of articles including the search terms. Further investigation and full-text reading were needed to ensure the results were accurate.

The objective was to identify the number of published articles using or discussing qualitative methods or approaches. It was not to conduct a quality appraisal of the results; therefore, with the exception of the decade it was published, no additional data were extracted.

Results

The 12 orthopaedic and trauma journals identified 7,201 articles containing the search terms. After titles and abstracts were screened, 169 records were assessed as potentially eligible. These full articles were screened against the eligibility criteria, resulting in 23 systematic literature reviews, ten editorials or opinion pieces, and 136 research studies using qualitative research methods in the study process (Table V).

Table V.

Breakdown of search results from each orthopaedic journal and the percentage of qualitative research published within the journals published articles.

| Journal title | Published articles identified in search, n | Articles identified from each journal archive search, n | Qualitative research papers, n | Systematic literature reviews/editorial or opinion articles, n | Qualitative research in journal, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| British Journal of Sports Medicine | 9,474 | 826 | 17 | 16 | 0.34 |

| American Journal of Sports Medicine | 11,685 | 798 | 5 | 0 | 0.04 |

| The Bone & Joint Journal | 16,550 | 233 | 7 | 1 | 0.04 |

| Bone & Joint Open | 513 | 61 | 21 | 0 | 4.00 |

| Journal of Arthroplasty | 10,762 | 802 | 7 | 0 | 0.06 |

| Arthroscopy - Journal of Arthroscopic and Related Surgery | 12,792 | 541 | 9 | 0 | 0.07 |

| Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery | 28,523 | 1,223 | 17 | 4 | 0.07 |

| Osteoarthritis and Cartilage | 16,335 | 1,110 | 14 | 3 | 0.10 |

| Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy | 8,641 | 486 | 7 | 1 | 0.09 |

| Acta Orthopedica | 8,885 | 147 | 2 | 0 | 0.02 |

| Bone & Joint Research | 870 | 95 | 5 | 1 | 0.60 |

| The Spine Journal | 14,522 | 652 | 10 | 3 | 0.08 |

| Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research | 13,907 | 227 | 15 | 4 | 0.13 |

| Total | 153,459 | 7,201 | 136 | 33 |

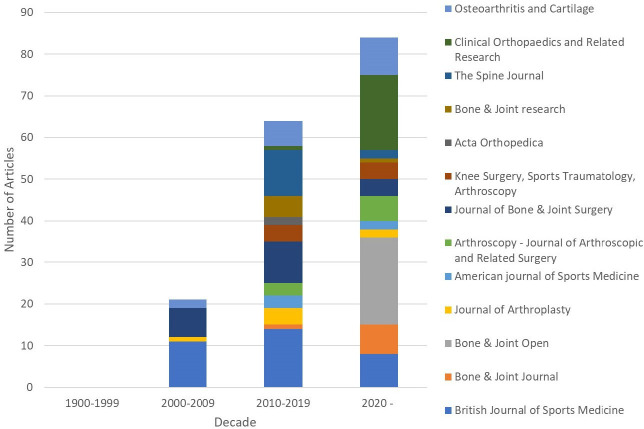

A PRISMA-style chart demonstrates the search process (Figure 1).19

Fig. 1.

PRISMA chart presenting the search process and results from the trauma and orthopaedic journals.

Articles including qualitative methods accounted for 0.1% of published articles out of the catalogue of work published by listed journals. Research studies using qualitative methodologies accounted for 0.08% of published articles within the included journals. In addition, 0.02% of published articles mentioned qualitative research within the paper. Bone & Joint Open included the greatest number of studies using qualitative methods; out of the available articles identified within their archives, 21 (4%) of these included qualitative methods.

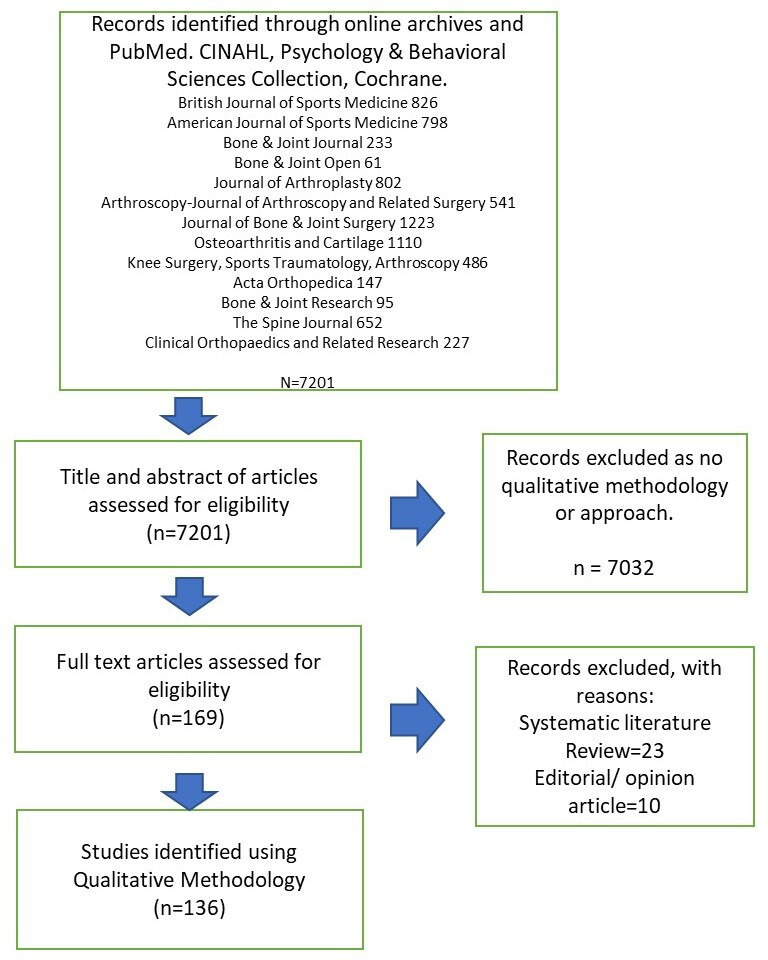

In the decade 2000 to 2009, 0.07% of published papers included qualitative methods in the journals; this rose to 0.14% between 2010 and 2019 (Table VI and Figure 2). The current decade is shown to predict the biggest increase so far, as the volume of qualitative research since 2020 already exceeds the previous decades’ data at 0.4% (Figure 3). However, it is important to note that along with the increase in qualitative research, there has also been marked increase in articles published overall. The ability to publish articles online in addition to printed copies resulted in over 15,000 more papers in the named journals in 2010 to 2019 compared to 2000 to 2009.

Table VI.

Number of articles including qualitative methodology published by decade in trauma and orthopaedic journals.

| Journal | 1900 to 1969 | 1970 to 1970 | 1980 to 1989 | 1990 to 1999 | 2000 to 2009 | 2010 to 2019 | 2020 to date | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| British Journal of Sports Medicine | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 14 | 8 | 33 |

| American Journal of Sports Medicine | N/A | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 5 |

| The Bone & Joint Journal | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 7 | 8 |

| Bone & Joint Open | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 21 | 21 |

| Journal of Arthroplasty | N/A | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 7 | |

| Arthroscopy - Journal of Arthroscopic and Related Surgery | N/A | N/A | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 6 | 9 |

| Journal of Bone Joint Surgery | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 10 | 4 | 21 |

| Osteoarthritis and Cartilage | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0 | 2 | 6 | 9 | 17 |

| Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 8 |

| Acta Orthopedica | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Bone & Joint Research | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 6 |

| The Spine Journal | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0 | 11 | 2 | 13 |

| Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 18 | 19 |

N/A, not applicable.

Fig. 2.

Number of qualitative research in orthopaedic journals by decade.

Fig. 3.

Institute of Medicine’s six dimensions of quality care.

The overall scarcity prompts questions about the prevalence of qualitative methodologies in orthopaedic research: are they underutilized? Are the research questions not conducive to qualitative inquiry? Alternatively, is there unconscious bias against publishing qualitative research in orthopaedic journals, suggesting that clinicians may believe that qualitative research methods are more suited to be published elsewhere?

Discussion

Nursing and allied professional research hold strong traditions of using qualitative methods.20 The role of the nurse and allied professionals is synonymous with a holistic view of the patient and family, and is underpinned by theories that are congruent with qualitative methodology.21 This rationale demonstrates that qualitative research is common within nursing and allied professional journals, and why qualitative methodologies are associated with these more “caring” and holistically focused disciplines. The medical and surgical mindset encourages clinicians to think in terms of cause and action, valuing concise quantitative results; qualitative research is sometimes considered “hopelessly subjective”, and “unscientific”.22 The quality of qualitative research has also been acknowledged as inconsistent in the past,23 which may have contributed to the perception of it being less valuable than quantitative methods.24 A holistic understanding of patient wellbeing extends beyond a biomedical model in all healthcare specialities, not least in trauma and orthopaedics. Acknowledging the intricate interplay of a patient’s biological, psychological, social, and economic circumstances is crucial for fostering a genuinely patient-centric healthcare environment and should be prioritized in every healthcare discipline.5,6,25

As presented in the results, Bone & Joint Open included by far the highest number of publications featuring qualitative methods among the listed journals. Bone & Joint Open was first published in 2020 and is dedicated to publishing high-quality clinical papers across a range of healthcare disciplines.26 By actively encouraging other healthcare professions to submit their research to Bone & Joint Open, the journal can include studies from those disciplines that have a strong history of using qualitative methods within their research. Importantly, though research using qualitative methods is evident in nursing journals and has increased overall over time, the rates across journals have fluctuated considerably, and the number of publications using qualitative methods were not as high as what could be assumed.20,23

A challenge lies in quantifying the impact of perceptions of care quality on patient outcomes and experiences. The NHS has integrated research and evidence-based practice as core strategies to enhance patient care. Therefore, it is essential to evaluate whether current research initiatives align with the priorities and concerns of the patients themselves. The merit of research findings and their scientific validity, often gauged through quantitative methods, may not always reflect the values and necessities perceived by patients.27 The Institute of Medicine’s (IOM) 2022 framework conceptualizes quality care as a complex construct comprising six dimensions:28 safety, effectiveness, timeliness, patient-centeredness, equity, and efficiency (Figure 3). These dimensions are guidelines for health professionals when considering how to holistically improve the standard of care provided through research and practice development endeavours.

Evaluating the measurement of quality in orthopaedic practice

Improving quality across all dimensions necessitates a collaborative, multidisciplinary approach that synergizes patient perspectives with clinical acumen. In the context of elective hip and knee arthroplasties, the success of these procedures has historically been gauged by the longevity and reliability of implants and rate of revisions.29-31 Over time, assessments have expanded to include readmission rates, mortality, and hospital stay duration, thereby furnishing a broader perspective on patient recovery and informing the evaluation of surgical wait times and criteria.32,33 However, these traditional metrics emphasize outcomes that may be more relevant to health professionals, potentially overlooking the patient’s subjective experience.

To address this, in 2009 the NHS introduced patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) for individuals undergoing these procedures.34 This initiative, aimed at enhancing patient choice and transparency, seeks to incorporate the patient’s voice as a critical dimension in evaluating care quality. However, PROMs, typically employed in assessing joint arthroplasties, are limited in scope, addressing only a narrow spectrum of functional activities and daily living tasks, and reporting results using quantitative numerical methods. Moreover, they are prone to a ‘ceiling effect’, where the most active individuals’ capabilities may not be fully captured.35 Alternative approaches, such as physical performance tests and activity-monitoring devices, are gaining traction in recovery protocols, offering more nuanced understandings of functional ability, and sometimes revealing disparities with PROMs data.36,37

Without considering patient experiences from their perspective, it remains unclear whether PROMs or functional tests adequately reflect aspects of recovery that mean the most to patients, or if they predominantly address healthcare professionals’ preconceptions. Qualitative research has been instrumental in uncovering patient priorities not apparent in existing PROMs,38,39 indicating significant divergence between quantifiable health outcomes and the patient-perceived quality of care. This raises fundamental questions for healthcare providers: how can we ensure patient-centred care when the outcome measures may not fully capture what is genuinely significant to patients?

Considering the IOM’s framework for measuring care quality,29 the methodologies employed in trauma and orthopaedics capture five of the six dimensions. Routine data collection on complications, infection rates, readmissions, and mortality rates underscore the dimension of safety. Waiting times for surgeries serve as proxy for timeliness. Analyses by national programmes such as Getting It Right First Time (GIRFT)40 and the Atlas of Variation41 address equity by identifying disparities in care delivery and evaluating the value of healthcare for populations and individuals. Data on hospital stay lengths and insights from GIRFT contribute to efficiency metrics. Implant survival data, catalogued in the National Joint Registry in the UK,42 and PROMs provide insight on effectiveness from clinical and patient standpoints. However, despite the extensive research and literature on these themes, the one dimension that appears to be under-represented within trauma and orthopaedic journals is person-centred care, which is vital to the holistic measurement of healthcare quality.

Fostering patient-centred research in trauma and orthopaedics

Person-centred care is pivotal for focusing on care, support, and treatment aspects important to patients, families, and caregivers.43 To deliver this effectively, it is crucial to discern its key components directly from a broad and representative range of patients without relying on presumptions. Qualitative research methodologies are particularly suited to unearth these insights and are especially useful for ascertaining viewpoints from groups of patients whose voice is seldom heard. Within hip and knee arthroplasty pathways, one example could be related to age. Current practice is influenced by the predominantly older patient demographic who undergo the operation. However, it is unknown if the outcomes and goals valued by this group align with those of the increasing number of younger patients undergoing hip arthroplasties.44

Mixed-methods research, marrying quantitative and qualitative approaches, offers a comprehensive understanding of the applicability of treatments and the patient experiences therein.45 Large-scale studies like SCIENCE46 and CRAFFT47 have integrated qualitative sub-studies to capture patient narratives beyond standardized follow-up, enriching our understanding of patient and family experiences. However, this approach is marginalized to patients involved in a RCT and excludes the experiences of those receiving standard care not involved in research. Bone & Joint Open have published the protocols of some of these large-scale studies which embed qualitative aspects within the study design; however, these qualitative findings are then published elsewhere in high-impact non-orthopaedic journals.48

Nonetheless, the intrinsic value of qualitative research in providing nuanced insights into patient experiences and the multifaceted nature of care is gaining recognition,4 and as identified in the results, there has been an increase in qualitative research published over recent decades. One domain which values qualitative research is examining strategies to enhance patient engagement and maximizing recruitment into trials.8,49-51 While the necessity for surgical trials is uncontested, an overemphasis on what is deemed ‘scientifically’ rigorous could marginalize alternative research approaches.52 By framing the role of qualitative research to supplement quantitative studies, it overlooks its broader possible contributions to evidence-based practice in trauma and orthopaedics. It is incumbent upon research communities to acknowledge and integrate the rich insights offered by qualitative research to ensure that healthcare’s evolution continues to be based on the pillars of scientific rigour and embodies the essence of person-centred care.

This bibliometric review has limitations. The multitude of medical and surgical journals available means that it is impossible to search every archive; therefore, the examples of qualitative orthopaedic research that undoubtably feature in high-impact non-orthopaedic journals are not included within this search. Healthcare journals publish vast amounts of articles, the number of which are increasing year by year; therefore, no individual has the time to consume the amount of evidence available in every journal.53 Evidence suggests that the majority of clinicians primarily read articles published within two or three key journals of their own speciality and discipline;54,55 therefore, findings published in high-impact non-orthopaedic journals or journals from other disciplines mean that clinicians within the orthopaedic speciality are unaware of the published findings, resulting in them being unable to consider the information and how it could impact their practice and approach to person-centred care.

The purpose of this article was to highlight the absence of qualitative research within the orthopaedic speciality; therefore, the featured journals were speciality journals. It is difficult to ascertain how under-represented qualitative research is in these journals, as the actual volume of qualitative research being conducted relative to quantitative research is unknown, as are rates of submission, review, and acceptance of qualitative research compared with non-qualitative research. It could be that quantitative researchers greatly outnumber qualitative ones, however the amount of qualitative research published in orthopaedic journals is so minimal, there are likely some other contributing elements. Further research is required to explore the factors and circumstances of publication rates within orthopaedic journals, and the journal publication policies that guide editorial decisions.

In conclusion, this review sought to substantiate the indispensable role of qualitative research methodologies in trauma and orthopaedics, underscoring their potential to unveil patients’ nuanced experiences and expectations, which often remain unseen by quantitative data alone. A more holistic and empathetic understanding of patient outcomes and satisfaction can be achieved by embedding qualitative methods within trauma and orthopaedic research. This approach complements quantitative methods and enriches them, providing a comprehensive picture that is crucial for truly patient-centred care. The imperative to integrate these methodologies is further amplified by the increasing demand that patient voices and narratives guide clinical decisions and personalize care. Thus, the paucity of qualitative studies in prominent orthopaedic journals is not just a gap in research, but a missed opportunity to enhance the quality and relevance of orthopaedic practice.

Advocating a shift towards greater inclusion of qualitative research in orthopaedic journals may require addressing inherent biases and misconceptions about the value of qualitative data. As the field progresses, it is crucial to promote a balanced research paradigm that recognizes the symbiotic relationship between qualitative and quantitative methodologies. This balance may allow for a more robust and nuanced exploration of patient care, ensuring that outcomes reflect the complexities of individual patient experiences and lead to more effective clinical solutions. Therefore, the research community must champion this cause, fostering an environment where qualitative research is not only conducted but also published and valued on par with quantitative studies. This paradigm shift is key to advancing a more patient-centred approach in trauma and orthopaedics, enhancing both the science and the humanity of patient care.

Take home message

- Qualitative research can provide unique insights which illuminate patient experiences and perceptions of care. However, trauma and orthopaedic specialty journals overwhelmingly favour publishing research using quantitative methods, resulting in a scarcity of qualitative studies.

- This article presents a bibliographic review demonstrating the absence of qualitative methods within the top 12 rated orthopaedic and trauma journals based on 2023 impact factor and SCImago journal ranking.

- Qualitative research methods are essential to the culture of person-centred care and quality improvement within healthcare.

Author contributions

L. E. Mew: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft

V. Heaslip: Writing – review & editing, Investigation

T. Immins: Investigation, Writing – review & editing

A. Ramasamy: Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing

T. W. Wainwright: Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing

Funding statement

This literature review was supported by Milton Keynes University Hospital and Bournemouth University. Neither Milton Keynes University Hospital or Bournemouth University had any involvement in the study design, in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in writing of the manuscript; and in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

ICMJE COI statement

V. Heaslip reports being a visiting professor at Bournemouth University, who paid the open access for this manuscript. T. W. Wainwright discloses institutional research funding from Stryker, Zimmer Biomet, and the National Institute for Health Research; personal consulting fees from Enhanced Medical Nutrition, Firstkind, Encare, and Pharmacosmos; and personal honoraria from Mölnlycke Health Care and Johnson & Johnson Medical, all of which are unrelated to this work.

Data sharing

The data that support the findings for this study are available to other researchers from the corresponding author upon reasonable request

Ethical review statement

Health Research Authority (HRA) approval was not required for this study due to no identifiable or personal details being collected. This was confirmed by both the HRA and Milton Keynes Research and Development department.

Open access funding

The authors report that they received open access funding for this manuscript from Bournemouth University, UK.

© 2024 Mew et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) licence, which permits the copying and redistribution of the work only, and provided the original author and source are credited. See https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

Contributor Information

Louise E. Mew, Email: louise.mew@mkuh.nhs.uk.

Vanessa Heaslip, Email: v.a.heaslip@salford.ac.uk.

Tikki Immins, Email: TImmins@bournemouth.ac.uk.

Arul Ramasamy, Email: arul.ramasamy@nhs.net, arul49@doctors.org.uk.

Thomas W. Wainwright, Email: twainwright@bournemouth.ac.uk.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings for this study are available to other researchers from the corresponding author upon reasonable request

References

- 1. Lohmander LS, Roos EM. The evidence base for orthopaedics and sports medicine: scandalously poor in parts. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(9):564–565. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-g7835rep. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lub V. Validity in qualitative evaluation: linking purposes, paradigms, and perspectives. Int J Qual Methods. 2015;14(5):1609406915621406. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Peat JK, Mellis C, Williams K, Xuan W. Health Science Research In Health science research: A handbook of quantitative methods Routledge; 2020. 10.4324/9781003115922 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pathak V, Jena B, Kalra S. Qualitative research. Perspect Clin Res. 2013;4(3):192. doi: 10.4103/2229-3485.115389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCormack B, Dulmen S, Eide H, Skovdahl K, Eide T. Person Centred Healthcare Research. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Klem N-R, Smith A, Shields N, Bunzli S. Demystifying qualitative research for musculoskeletal practitioners part 1: What is qualitative research and how can it help practitioners deliver best-practice musculoskeletal care? J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2021;51(11):531–532. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2021.0110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jones R. Why do qualitative research? BMJ. 1995;311(6996):2. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.6996.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rapport F, Storey M, Porter A, et al. Qualitative research within trials: developing a standard operating procedure for a clinical trials unit. Trials. 2013;14:54. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-14-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Esmail L, Moore E, Rein A. Evaluating patient and stakeholder engagement in research: moving from theory to practice. J Comp Eff Res. 2015;4(2):133–145. doi: 10.2217/cer.14.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. O’Mara-Eves A, Brunton G, McDaid D, et al. Community engagement to reduce inequalities in health: a systematic review, meta-analysis and economic analysis. Public Health Research. 2013;1(4):1–526. doi: 10.3310/phr01040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kinmonth A-L. Understanding and meaning in research and practice. Fam Pract. 1995;12(1):1–2. doi: 10.1093/fampra/12.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Buchbinder R, Maher C, Harris IA. Setting the research agenda for improving health care in musculoskeletal disorders. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2015;11(10):597–605. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2015.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bourne AM, Johnston RV, Cyril S, et al. Scoping review of priority setting of research topics for musculoskeletal conditions. BMJ Open. 2018;8(12):e023962. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gwilym SE, Perry DC, Costa ML. Trauma and orthopaedic research is being driven by priorities identified by patients, surgeons, and other key stakeholders. Bone Joint J. 2021;103-B(8):1328–1330. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.103B8.BJJ-2020-2578.R1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.No authors listed . National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR; 2021. [9 October 2024]. Briefing notes for researchers - public involvement in NHS, health and social care research.https://www.nihr.ac.uk/briefing-notes-researchers-public-involvement-nhs-health-and-social-care-research date last. accessed. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Johansson EE, Risberg G, Hamberg K. Is qualitative research scientific, or merely relevant? online. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2003;21(1):10–14. doi: 10.1080/02813430310000492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Montazeri A, Mohammadi S, M Hesari P, Ghaemi M, Riazi H, Sheikhi-Mobarakeh Z. Preliminary guideline for reporting bibliometric reviews of the biomedical literature (BIBLIO): a minimum requirements. Syst Rev. 2023;12(1):239. doi: 10.1186/s13643-023-02410-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.No authors listed . SCImago; [9 October 2024]. Journal and country rank.http://www.scimagojr.com date last. accessed. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gagliardi AR, Umoquit M, Webster F, Dobrow M. Qualitative research publication rates in top-ranked nursing journals: 2002-2011. Nurs Res. 2014;63(3):221–227. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0000000000000022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Remshardt M, Flowers DL. Understanding qualitative research. Am Nurse. 2007;2(9):20–32. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hennink M, Hutter I, Bailey A. Qualitative Research Methods. London, UK: Sage Publications; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ball E, McLoughlin M, Darvill A. Plethora or paucity: a systematic search and bibliometric study of the application and design of qualitative methods in nursing research 2008-2010. online. Nurse Educ Today. 2011;31(3):299–303. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kuper A, Reeves S, Levinson W. An introduction to reading and appraising qualitative research. BMJ. 2008;337:a288. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pelzang R. Time to learn: understanding patient-centred care. Br J Nurs. 2010;19(14):912–917. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2010.19.14.49050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.No authors listed . Bone & Joint Open; 2024. [9 October 2024]. Journal overview.https://boneandjoint.org.uk/journal/BJO/journal-overview date last. accessed. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lloyd K, White J. Democratizing clinical research. Nature. 2011;474(7351):277–278. doi: 10.1038/474277a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.No authors listed . Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; [9 October 2024]. Provide a framework for understanding healthcare quality.https://www.ahrq.gov/talkingquality/explain/communicate/framework.html date last. accessed. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wroblewski BM, Siney PD, Fleming PA. Charnley low-friction arthroplasty: survival patterns to 38 years. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89-B(8):1015–1018. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.89B8.18387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hooper GJ, Rothwell AG, Stringer M, Frampton C. Revision following cemented and uncemented primary total hip replacement: a seven-year analysis from the new zealand joint registry. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91-B(4) doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.91B4.21363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wyles CC, Jimenez-Almonte JH, Murad MH, et al. There are no differences in short- to mid-term survivorship among total hip-bearing surface options: a network meta-analysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(6):2031–2041. doi: 10.1007/s11999-014-4065-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ashby E, Grocott MPW, Haddad FS. Outcome measures for orthopaedic interventions on the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90-B(5):545–549. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.90B5.19746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Stambough JB, Nunley RM, Curry MC, Steger-May K, Clohisy JC. Rapid recovery protocols for primary total hip arthroplasty can safely reduce length of stay without increasing readmissions. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30(4):521–526. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2015.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Devlin NJ, Parkin D, Browne J. Patient-reported outcome measures in the NHS: new methods for analysing and reporting EQ-5D data. Health Econ. 2010;19(8):886–905. doi: 10.1002/hec.1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hamilton DF, Giesinger JM, MacDonald DJ, Simpson AHRW, Howie CR, Giesinger K. Responsiveness and ceiling effects of the forgotten joint score-12 following total hip arthroplasty. Bone Joint Res. 2016;5(3):87–91. doi: 10.1302/2046-3758.53.2000480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dayton MR, Judd DL, Hogan CA, Stevens-Lapsley JE. Performance-based versus self-reported outcomes using the hip disability and osteoarthritis outcome score after total hip arthroplasty. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2016;95(2):132–138. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0000000000000357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Crizer MP, Kazarian GS, Fleischman AN, Lonner JH, Maltenfort MG, Chen AF. Stepping toward objective outcomes: a prospective analysis of step count after total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32(9S):S162–S165. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2017.02.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Archibald G. Patients’ experiences of hip fracture. J Adv Nurs. 2003;44(4):385–392. doi: 10.1046/j.0309-2402.2003.02817.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zidén L, Scherman MH, Wenestam C-G. The break remains – elderly people’s experiences of a hip fracture 1 year after discharge. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32(2):103–113. doi: 10.3109/09638280903009263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.No authors listed . National Health Service England; 2023. [9 October 2024]. Getting It Right First Time (GIRFT)//gettingitrightfirsttime.co.uk date last. accessed. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.No authors listed . National Health Service England; 2023. [9 October 2024]. NHS Atlas Series.www.england.nhs.uk/rightcare/rightcare-resources/atlas/ date last. accessed. [Google Scholar]

- 42.No authors listed . National Joint Registry; 2023. [9 October 2024]. 20th annual report.www.NJRcentre.org.uk date last. accessed. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gluyas H. Patient-centred care: Improving healthcare outcomes. Nurs Stand. 2015;30(4):50–57. doi: 10.7748/ns.30.4.50.e10186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Malcolm TL, Szubski CR, Nowacki AS, Klika AK, Iannotti JP, Barsoum WK. Activity levels and functional outcomes of young patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty. Orthopedics. 2014;37(11):e983–92. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20141023-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Heyvaert M, Hannes K, Maes B, Onghena P. Critical appraisal of mixed methods studies. J Mix Methods Res. 2013;7(4):302–327. doi: 10.1177/1558689813479449. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Papiez K, Tutton E, Phelps EE, et al. A qualitative study of parents’ and their child’s experience of a medial epicondyle fracture. Bone Jt Open. 2021;2(6):359–364. doi: 10.1302/2633-1462.26.BJO-2020-0186.R1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.No authors listed . NDORMS; 2020. [9 October 2024]. The CRAFFT study.https://crafft-study.digitrial.com date last. accessed. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Phelps EE, Tutton E, Costa ML, Achten J, Moscrop A, Perry DC. Protecting my injured child: a qualitative study of parents’ experience of caring for a child with a displaced distal radius fracture. BMC Pediatr. 2022;22(1):270. doi: 10.1186/s12887-022-03340-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Toye F, Williamson E, Williams MA, Fairbank J, Lamb SE. What value can qualitative research add to quantitative research design? an example from an adolescent idiopathic scoliosis trial feasibility study. Qual Health Res. 2016;26(13):1838–1850. doi: 10.1177/1049732316662446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Perry DC, Griffin XL, Parsons N, Costa ML. Designing clinical trials in trauma surgery. Bone Joint Res. 2014;3(4):123–129. doi: 10.1302/2046-3758.34.2000283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. O’Cathain A, Thomas KJ, Drabble SJ, Rudolph A, Hewison J. What can qualitative research do for randomised controlled trials? A systematic mapping review. BMJ Open. 2013;3(6):e002889. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Howard D, Davis P. The use of qualitative research methodology in orthopaedics – tell it as it is. J Orthop Nurs. 2002;6(3):135–139. doi: 10.1016/S1361-3111(02)00051-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Leopold SS. Editorial: Getting the most from what you read in orthopaedic journals. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2017;475(7):1757–1761. doi: 10.1007/s11999-017-5371-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Jones TH, Hanney S, Buxton MJ. The journals of importance to UK clinicians: a questionnaire survey of surgeons. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2006;6:24. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-6-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Krueger CA, Hsu JR, Belmont PJ. What to read and how to read it: a guide for orthopaedic surgeons. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016;98-A(3):243–249. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.O.00307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings for this study are available to other researchers from the corresponding author upon reasonable request