Key Points

Question

How frequently are reports of drug-related supply chain issues associated with drug shortages in the US vs Canada?

Findings

In this cross-sectional study, there were 104 reports of drug-related supply chain issues that occurred from 2017 to 2021 in both countries. Within 12 months of the reported supply chain issues, 49.0% were associated with drug shortages in the US compared with 34.0% in Canada.

Meaning

Drug shortages were less frequent in Canada compared with in the US after drug-related supply chain issues were reported in both countries. These findings inform ongoing policy development and highlight the need for international cooperation between countries to curb the effects of drug shortages and improve the resiliency of the supply chain for drugs.

Abstract

Importance

Drug shortages are a persistent public health issue that increased during the COVID-19 pandemic. Both the US and Canada follow similar regulatory standards and require reporting of drug-related supply chain issues that may result in shortages. However, it is unknown what proportion are associated with meaningful shortages (defined by a significant decrease in drug supply) and whether differences exist between Canada and the US.

Objective

To compare how frequently reports of drug-related supply chain issues in the US vs Canada were associated with drug shortages.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Longitudinal cross-sectional study conducted from January 2023 to March 2024 using drug-related reports of supply chain issues from 2017 to 2021 that were less than 180 days apart in Canada and the US. Shortages were assessed using data from the IQVIA Multinational Integrated Data Analysis database, comprising 89% of US and 100% of Canadian drug purchases.

Exposure

Country (Canada vs US), timing of report issuance (before vs after the COVID-19 pandemic), and characteristics of the supply chain prior to the reports of drug-related supply chain issues (including World Health Organization essential medicine status, Health Canada tier 3 medicine [moderate risk classification], whether there was sole-source manufacturing of the drug, the formulation, the price per unit, ≥20 years since drug approval, and the number of therapeutic alternatives).

Main Outcomes and Measures

A drug shortage (a decrease of ≥33% in monthly purchased standardized drug units) within 12 months, relative to the average units purchased during the 6 months prior to the report of supply chain issues to a US or Canadian reporting system.

Results

Among the 104 drug-related reports of supply chain issues in both countries, 49.0% (95% CI, 39.3%-59.7%) were associated with drug shortages in the US vs 34.0% (95% CI, 25.0%-45.0%) in Canada (adjusted hazard ratio [HR], 0.53 [95% CI, 0.36-0.79]). The lower risk of drug shortages in Canada vs the US was consistent before the COVID-19 pandemic (adjusted HR, 0.47 [95% CI, 0.30-0.75]) and after the pandemic (adjusted HR, 0.31 [95% CI, 0.15-0.66]). After combining reports of supply chain issues in both countries, the shortage risk was double for sole-sourced drugs (adjusted HR, 2.58 [95% CI, 1.57-4.24]) and nearly half for Canadian tier 3 medicines (moderate risk) (adjusted HR, 0.56 [95% CI, 0.32-0.98]).

Conclusions and Relevance

Drug-related reports of supply chain issues were 40% less likely to result in meaningful drug shortages in Canada compared with the US. These findings highlight the need for international cooperation between countries to curb the effects of drug shortages and improve resiliency of the supply chain for drugs.

This longitudinal cross-sectional study compares how frequently reports of drug-related supply chain issues were associated with drug shortages in the US compared with Canada.

Introduction

There are persistent global drug shortages, in part because drug-related supply chains are increasingly globalized1,2; these drug shortages are associated with delayed or missed treatment and adverse outcomes.3,4,5,6,7,8 In addition, pandemics and natural disasters disrupt global drug production, further affecting supply chains. However, countries differ in policy and regulatory authority, which may affect whether supply chain issues develop into drug shortages.

For instance, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Safety and Innovation Act of 2012 required that manufacturers report any “…interruption of the manufacture of the drug that is likely to lead to a meaningful disruption in…supply” to the FDA, albeit without penalties for the failure to report.9 The FDA has regulatory flexibilities to prevent shortages after reported issues, including working with manufacturers to address quality concerns, expediting applications to restore production, extending expiration dates, or relaxing import regulations.10,11

Canada represents a good comparator for the effectiveness of US policies because Canada has similar regulatory standards and manufacturing inspections with strong cooperation between both national regulators. Although medical insurance coverage is structured differently in Canada, prescription drug coverage is similar to the US in that half of the prescriptions are reimbursed through public insurance and half through private insurance.12 Canada passed drug shortage legislation similar to the FDA Safety and Innovation Act that required reporting of supply chain issues to Health Canada (Canada’s drug regulatory agency).13 However, Health Canada has a more proactive regulatory approach (vs the FDA) to track supply and demand issues and work with stakeholders to mitigate unexpected shocks.14,15

Both the US and Canada passed new shortage policies during the COVID-19 pandemic that have not yet been assessed or compared. For example, the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act enhanced the authority of the FDA to prioritize applications and inspections for drugs during shortages, and requires greater transparency of the supply chains and the sources of the ingredients.16 The pandemic-related shortage policies implemented in Canada include competitive government bidding, improved importation regulations, and supply chain expansion.17 In addition, Canada was one of the first countries to mandate public reporting of supply chain issues by manufacturers.12

Given the growing prevalence of drug shortages globally, the destabilizing effect of the pandemic, and the implementation and proposal of new policies to mitigate shortages, the objective of this study was to compare how frequently drug-related reports of supply chain issues in the US vs Canada were associated with drug shortages overall and stratified by the years prior to the COVID-19 pandemic (2017-2020) and the years during the pandemic (2020-2021).

Methods

We conducted a population-based study using a longitudinal cross-section of drugs used in both the US and Canada from 2017 through 2021. The University of Pittsburgh institutional review board approved the study as “nonhuman subjects” research that did not require informed consent. We followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.18

Policy Background and Approach

The FDA and Health Canada define a drug shortage as an event wherein the supply of a drug does not meet demand; both countries require manufacturers to report supply chain issues that could affect supply such as failures in good manufacturing practice, ingredient shortages, or shipping delays.9,19 In the US, manufacturers report to the FDA, which then makes an assessment and publicly posts reports (eFigure 1 in Supplement 1). The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) also collects information from US clinicians about supply issues and verifies the information with the manufacturers. In Canada, the manufacturers report directly to a public reporting website that Health Canada uses to inform its response.19

The current study addresses the extent to which drug-related reports of supply chain issues are associated with drug shortages. This is an important outcome because when reports of supply chain issues are made, regulatory flexibilities and local efforts may address the issues prior to the depletion of supplies and prevent actual drug shortages. In addition, the likelihood of drug-related reports of supply chain issues being associated with drug shortages were compared between Canada and the US, which are 2 countries with different policy and health care environments but with similar regulatory and payer systems for prescription drugs. To make these comparisons, drugs with new reports of supply chain issues in both countries were selected and compared with subsequent drug shortages (defined as decreases in national supply).

Data Source and Study Population

A cross-sectional study was conducted using data from IQVIA’s Multinational Integrated Data Analysis (MIDAS) database, comprising 89% of US and 100% of Canadian drug purchases.20 The study population was drugs purchased in both the US and Canada with at least 1 incident report of supply chain issues from January 2017 to September 2021 (to ensure ≥3 months of data to define outcomes) (Figure 1). The drugs were identified at the molecule formulation level (eg, oral valsartan; parenteral labetalol). The data were aggregated by country and reported in total standardized units (eg, 1 pill or capsule, vial, or 5 mL of oral liquid). The drugs not fully captured in the MIDAS database were excluded, including over-the-counter medications, radiopharmaceuticals, antidotes, and antigens (eTable 1 in Supplement 1) as well as topical products (eTable 2 in Supplement 1).

Figure 1. Episodes of Supply Chain Issues in the US and Canada.

aThe drugs were classified using the active ingredient (molecule) formulation.

bA detailed list of the nonprescription products appears in eTable 1 in Supplement 1.

cThese reports were at the drug strength, formulation, and manufacturer level and thus the numbers were higher compared with the US.

dIdentified from the US Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA’s) public drug shortage website under the “discontinuations” tab. The archived reports were sourced from the Wayback Machine (an internet archive website).

eIdentified from the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists public drug shortage website.

fIdentified from the FDA’s product recall database. The archived reports were sourced from the Wayback Machine.

gIdentified from the FDA’s public drug shortage website under the “current/resolved shortages” tab. The archived reports were sourced from the Wayback Machine.

hIdentified from the Health Canada public drug shortage website.

iThese episodes occurred more than 90 days from another US report (on the FDA website or the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists website) and were excluded given the likely differences in reporting and the lack of similar reporting mechanisms in Canada.

Drugs with incident reports of supply chain issues in both countries were identified using information from the FDA,21 the ASHP,22 and Health Canada.23 Although the US reports are at the drug formulation level, the Health Canada reports are at the manufacturer, drug formulation, and dosage level (called a Drug Identification Number). Thus, for the same drug in both countries, the number of reports expected in Canada would be higher. Given complementary information, reports from the FDA and the ASHP were merged for the same drug formulation within 90 days. Index dates in the US were defined as the first posting date to either the FDA or the ASHP website (eFigure 2 in Supplement 1).

To remain consistent, reports to Health Canada were combined for the same drug formulation within 90 days. To ensure problems occurred in both countries, supply chain issue reports were only included if they occurred for the same drug formulation within 180 days in both the US and Canada.24 Recalls and discontinuations that did not occur within 90 days of a report from the FDA or the ASHP were excluded because these events are different in nature from shortages,21 and because Health Canada does not have a complementary reporting system. To understand the reasons for drug shortages, both Canadian and US data were used; the Canadian data (characterized by structured predefined variable types) were contrasted with the US data, which included free text that was mapped to the FDA Safety and Innovation Act categories.

Outcome Measure of Interest

The primary outcome was a drug shortage within 12 months after a report of drug-related supply chain issues to a US and a Canadian reporting system. All drug shortages studied were preceded by a supply chain issue report. Country-specific index dates were defined using the first report in each location. Reports issued before January 2017 were excluded. Based on previous literature,24,25 shortages were defined as a decrease of 33% or greater in monthly purchased standardized drug units within 12 months, relative to average units purchased during the 6 months prior to the report. This cutoff was informed by previous work,1,24 and is higher than the changes expected due to seasonality.

Covariates

Several drug characteristics were defined that may be associated with shortage risk. Variables from the MIDAS database included drug formulation, the number of manufacturers (sole-source manufacturer vs ≥2 manufacturers), and the number of available alternatives matched by formulation within the same drug class during the 6 months before issuance of a report. The average unit price in each country was calculated in the MIDAS database by dividing gross sales by purchased units. Years since approval and generic availability were sourced from Drugs@FDA (December 2023) and the Canadian Drug Product Database (December 2023). Indicators for World Health Organization essential medicine status were also created using the full electronic list (June 2022). Canadian tier 3 medicine (defined using historical lists from November 2023) denotes drugs with the greatest potential effects on Canada’s drug supply and health care system (eTable 2 in Supplement 1).26

Statistical Analyses

We constructed Kaplan-Meier curves for time to first drug shortage for Canada vs the US using country-specific index dates. Survival proportions underlying these curves were then used to estimate the unadjusted cumulative incidence of shortages at 12 months. Drugs were right censored after 12 months (on December 2021, which is the end date for the data used in this analysis) or at the end date of the report of supply chain issues.

To compare cumulative risk of drug shortage for Canada vs the US, Cox proportional hazards models were specified for time to first drug shortage and adjusted for the covariates listed in the prior subsection. To allow for slight differences in reporting and duration, country-specific index dates were used so that US drug shortages were attributed to US reports and vice versa for Canada. A robust variance estimator was used to account for the clustering of US and Canadian reports that were within 180 days from each other.

To test for heterogeneity during COVID-19, a separate model was fitted that included interaction terms for all reports issued before and after March 2020. A type I error rate of .05 was assumed (P value), hypothesis tests were 2-sided, and no adjustments were made for multiple testing. The analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc), Stata version 16.1 (StataCorp), and R Studio version 4.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Sensitivity Analyses

Sensitivity analyses using different drug shortage definitions were conducted to assess the influence of methodological assumptions on findings. First, shortages were redefined as decreases of 33% or greater within 6 months or 18 months (vs 12 months) and among reports of supply chain issues with a duration of 12 months or longer in both countries. Severe drug shortages (defined as decreases of ≥66% within 12 months) were similarly assessed. To determine the effects of US recalls or discontinuations, the analyses were repeated and the cohort was expanded to also include recalls or discontinuations that did not appear in the shortage reports from the FDA or the ASHP.

Results

This study was conducted from January 2023 to March 2024 using drug-related reports of supply chain issues from 2017 to 2021 that were less than 180 days apart in Canada and the US. There were 5876 purchased drugs reported in the MIDAS database and 1198 met the inclusion criteria (Figure 1). Among these, there were 10 772 drug-related reports of supply chain issues in Canada at the manufacturer, drug formulation, and dosage level and 1018 in the US at the drug formulation level. After merging reports based on the drug formulation and removing reports that did not occur in both countries, 96 unique drugs were identified with at least 1 report of concurrent supply chain issues (88 drugs had 1 report and 8 drugs had 2 reports) yielding a final sample size of 104 drug-related reports of supply chain issues.

Either no reason or an unspecified reason for the supply chain issue was provided for 25 reports (24%) in the US (Table). All 104 reports in Canada had a reason listed, half (53 [51%]) of which were for disruption of the manufacture of the drug. Most reports of supply chain issues were for drugs that received approval 20 years ago or longer (89 in the US [86%] and 85 in Canada [82%]). Drugs with a sole-source manufacturer made up 1 in 5 reports (21 in the US [20%] and 29 in Canada [28%]) and generic drugs accounted for more than 90% of reports in both countries (Table). We did not observe any substantial time trends in reporting (Figure 2A).

Table. Characteristics of Included Reports of Supply Chain Issues in the US and Canada From 2017 to 2021.

| Reports of supply chain issues, No. (%) (N = 104)a |

|

|---|---|

| By date of COVID-19 public health emergency | |

| Before (January 2017-February 2020) | 74 (71) |

| During (March 2020-September 2021) | 30 (29) |

| By therapeutic class in the IQVIA MIDAS databaseb | |

| Nervous system | 20 (19) |

| Cardiovascular system | 13 (13) |

| Anti-infective for systemic use | 14 (13) |

| Antineoplastic and immunomodulating agents | 12 (12) |

| Alimentary tract and metabolism | 12 (12) |

| Blood or blood-forming organs | 6 (6) |

| Musculoskeletal system | 6 (6) |

| Respiratory system | 6 (6) |

| Sensory organs | 5 (5) |

| Genitourinary system and sex hormones | 4 (4) |

| Systemic hormonal preparations (excludes sex hormones and insulin) | 3 (3) |

| Otherc | 3 (3) |

| By reason for supply chain issue | |

| US | |

| Manufacturing, packaging, or shipping issues | 42 (40) |

| No reason or an unspecified reason | 25 (24) |

| Discontinuation of the manufacture of the drug | 19 (18) |

| Other eventsd | 12 (12) |

| Business decision | 2 (2) |

| Impurities or lack of sterility | 4 (4) |

| Canada | |

| Disruption of the manufacture of the drug | 53 (51) |

| Other eventse | 30 (29) |

| Manufacturing issues or delay in shipping | 15 (14) |

| Business decision | 3 (3) |

| Requirements related to good manufacturing practices | 3 (3) |

| By duration of supply chain issue, median (IQR), mo | |

| US | 17 (12-31) |

| Canada | 16 (4-29) |

| World Health Organization essential medicinef | 54 (52) |

| Tier 3 medicine (moderate risk) in Canadag | 21 (20) |

| By average drug price per unit, US$h,i | |

| US | |

| <1 | 30 (29) |

| 1-4.99 | 20 (19) |

| 5-9.99 | 15 (14) |

| ≥10 | 39 (38) |

| Canada | |

| <1 | 31 (30) |

| 1-4.99 | 28 (27) |

| 5-9.99 | 13 (13) |

| ≥10 | 32 (31) |

| ≥20 y Since drug approval | |

| US (approved by the Food and Drug Administration) | 89 (86) |

| Canada (approved by Health Canada) | 85 (82) |

| Sole-source manufacturerh | |

| US | 21 (20) |

| Canada | 29 (28) |

| Drug formulation | |

| Oral | 31 (30) |

| Parenteral | 63 (61) |

| Other formulationj | 10 (10) |

| No. of alternatives for unavailable drugh,k | |

| US | |

| 0 | 6 (6) |

| 1 | 8 (8) |

| 2-5 | 24 (23) |

| 6-10 | 35 (34) |

| ≥11 | 31 (30) |

| Canada | |

| 0 | 3 (3) |

| 1 | 10 (10) |

| 2-5 | 37 (36) |

| 6-10 | 36 (35) |

| ≥11 | 18 (17) |

| Generic drug | |

| US | 98 (94) |

| Canada | 96 (92) |

| Brand-name drug | |

| USl | 6 (6) |

| Canadam | 8 (8) |

Abbreviation: MIDAS, Multinational Integrated Data Analysis.

Defined using data from the US Food and Drug Administration, the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP), and Health Canada. Data are expressed as No. (%) unless otherwise indicated. The included reports were restricted to those that occurred 180 days apart or sooner in both the US and Canadian databases. Of the 96 drugs with any report of supply chain issues, 88 (92%) had 1 episode and 8 (8%) had 2 episodes, thus equaling 104 total reports.

Assigned by the World Health Organization, the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical level 1 (ATC1) is a unique code used to classify drugs based on body system.

Drug products listed as treating “various” (ATC1 V) or “other” (ATC1 K).

Included regulatory delays, shortages of ingredients, demand increases, or other reasons.

Included increases in the demand for the drug, shortages of an active ingredient, shortages of an inactive ingredient or component, or reason listed as “other.”

Defined using the agency’s database of essential medicines (downloaded in June 2022). A full list of included medicines appears in eTable 2 in Supplement 1.

Identified using historical lists from Health Canada (November 2023). Shortages of tier 3 medicines have the greatest potential effects on Canada’s drug supply and health care system. Medical necessity and low availability of alternative supplies, ingredients, or therapies determine the degree of the effects of the shortages.

Measured 6 months prior to the issuance of the first report of supply chain issues within each episode.

Calculated as total sales of former manufacturer divided by total units available in the 6 months before the issuance of any report of supply chain issues. Sales were exclusive of drug rebates and were not adjusted for inflation.

Ophthalmic, optic, or inhaled products.

Proxied using the total number of unique molecules of the same formulation in each ATC level 3 (drugs classified based on body system and mechanism of action).

Manually assigned using the Drugs@FDA data files (downloaded in December 2023). Drugs were characterized as brand-name if all approvals that occurred prior to the issuance of a supply chain issue report were under New Drug Application licenses.

Manually assigned using the Health Canada Drug Product database (downloaded in December 2023).

Figure 2. Supply Chain Issues and Associations With Drug Shortages Within 12 Months.

aThe drugs were classified using the active ingredient (molecule) formulation. For the primary analysis, the index date of each supply chain issue was defined separately for the US and Canada using the minimum report date within each country to allow for differences in reporting.

bThe supply chain issues are grouped using the minimum reporting date in the US or Canada (whichever occurred first) for descriptive purposes only. Among the 104 supply chain issues included, 47 (45%) were not associated with drug shortages (within 12 months of the first report in the US or Canada), 26 (25%) were associated with shortages in the US only (within 12 months of the first US report), 10 (10%) were associated with shortages in Canada only (within 12 months of the first report in Canada), and 21 (20%) were associated with shortages in both the US and Canada (within 12 months of the first report in Canada and the US).

Drug Shortages by Country and Supply Chain Characteristics

There were 26 reports (25%) of supply chain issues associated with drug shortages in the US only, 10 (10%) in Canada only, and 21 (20%) in both countries. Drug shortages in 1 country vs both countries did not differ based on baseline characteristics (eTable 3 in Supplement 1). We also did not observe time trends in reports associated with shortages only in the US, only in Canada, or in both countries (Figure 2B).

At 12 months, 49.0% (95% CI, 39.3%-59.7%) of reports of supply chain issues were associated with drug shortages in the US vs 34.0% (95% CI, 25.0%-45.0%) of reports of supply chain issues in Canada (Figure 3). The lower risk of drug shortages in Canada was consistent at each month of follow-up. Unadjusted Kaplan-Meier curves by supply chain characteristics and country appear in eFigures 3 to 9 in Supplement 1.

Figure 3. Unadjusted Cumulative Incidence of Drug Shortages Within 12 Months After Reports of Supply Chain Issues in the US and Canada for 2017 to 2021.

Drug shortages were defined as decreases in purchased units that were 33% or greater relative to the average value during the 6 months prior to the issuance of a report for incident supply chain issues. To account for censoring, Kaplan-Meier curves were used to estimate the cumulative percentage of reports associated with drug shortages within each country by 12 months.

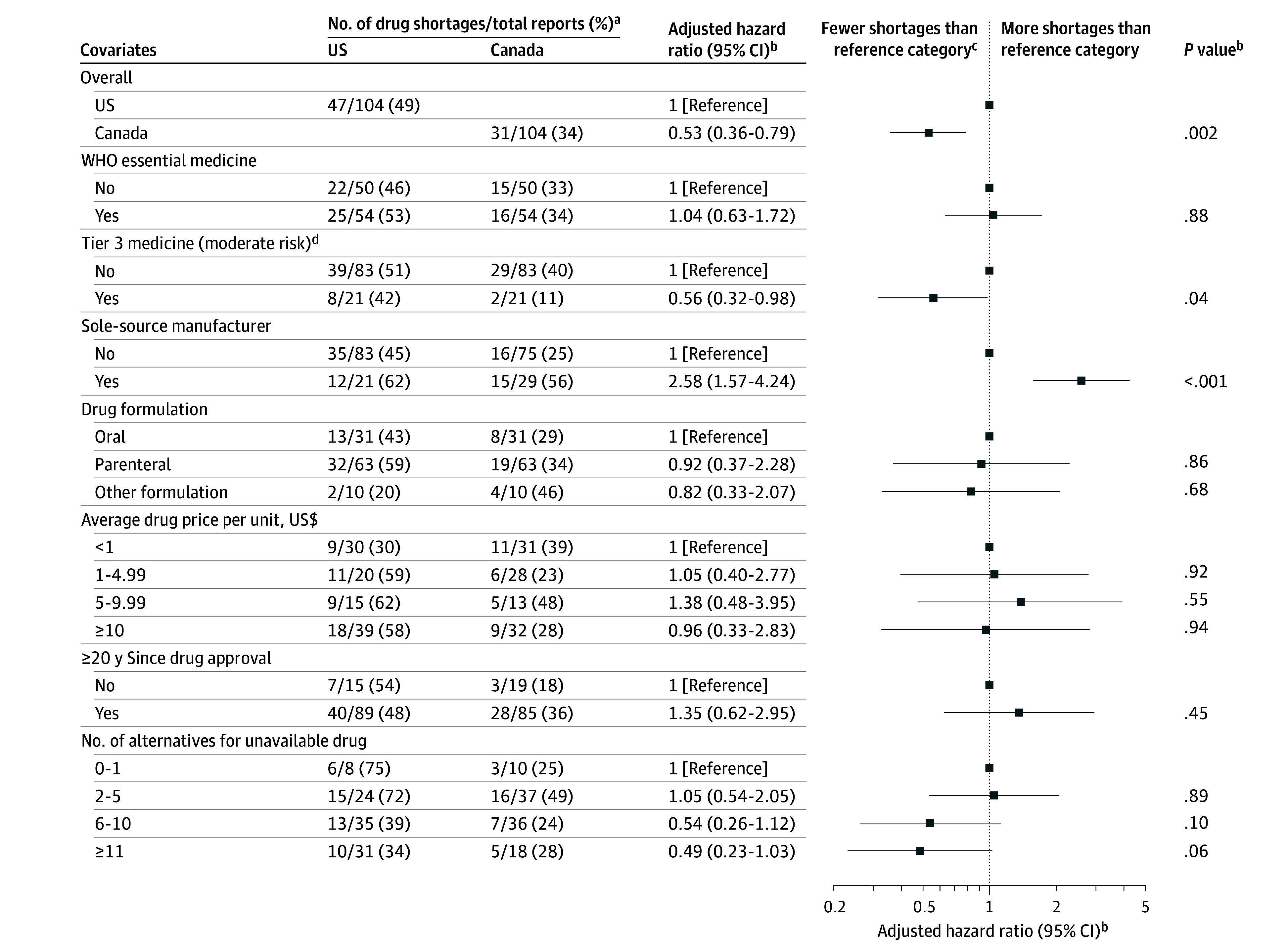

The adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) comparing drug shortages in Canada vs the US by supply chain characteristics appear in Figure 4 (the full regression output appears in eTable 4 in Supplement 1). After adjusting for other drug characteristics from 2017 to 2021, reports of supply chain issues were approximately 40% less likely to be associated with drug shortages in Canada compared with the US (adjusted HR, 0.53 [95% CI, 0.36-0.79]). After combining reports of supply chain issues from both the US and Canada, the shortage risk was double for drugs with a sole-source manufacturer (adjusted HR, 2.58 [95% CI, 1.57-4.24]) and nearly half for Canadian tier 3 (moderate risk) medicines (adjusted HR, 0.56 [95% CI, 0.32-0.98]).

Figure 4. Supply Chain Characteristics Associated With Drug Shortages Within 12 Months in the US and Canada for 2017 to 2021.

WHO indicates World Health Organization.

aDrug shortages were defined as decreases in purchased units that were 33% or greater relative to the average value during the 6 months prior to the issuance of a report for incident supply chain issues.

bA multivariable Cox proportional hazards model was used to compare time to first drug shortage for reports in the US and Canada. Given the limited sample sizes, all reports were analyzed together for both countries across the entire study period (2017-2021). Interaction terms by country or period were not used to avoid overfitting (eg, the hazard ratio of 1.04 [95% CI, 0.63-1.72] for WHO essential medicine is interpreted as all reports having an additional risk of 4% for being associated with shortages within 12 months in either country from 2017-2021 vs all reports for nonessential drugs and after adjustment for all other drug characteristics in the model). The full regression output appears in eTable 4 in Supplement 1.

cFor example, there were fewer shortages in the “yes” category for the “WHO essential medicine” covariate vs the “no” reference category when combining all reports for both countries across the entire study period (2017-2021).

dDenotes drugs with the greatest potential effects on Canada’s drug supply and health care system (defined using historical lists from November 2023; additional information appears in eTable 2 in Supplement 1).

Drug Shortages by Pandemic Period

There were 30 reports of supply chain issues issued after March 2020 (eTable 5 in Supplement 1). Reports in the US issued after March 2020 were more likely to involve manufacturing, packaging, or shipping issues (15 [50%] after March 2020 vs 27 [37%] before March 2020) and other events such as increased demand or ingredient shortages (7 [23%] after March 2020 vs 5 [7%] before March 2020). Reports in Canada issued after March 2020 were more likely to involve disruptions of the manufacture of the drug (19 [63%] after March 2020 vs 34 [46%] before March 2020).

The frequency of drug shortages after reports of supply chain issues was lower after March 2020 in both countries (27.5% [95% CI, 14.8%-47.7%] in the US vs 29.1% [95% CI, 14.7%-52.3%] in Canada (eFigure 10 in Supplement 1). We did not observe statistically significant interactions by COVID-19 period for Canada vs the US (eTable 6 in Supplement 1). The lower risk of drug shortages in Canada vs the US was consistent before the COVID-19 pandemic (adjusted HR, 0.47 [95% CI, 0.30-0.75]) and after the pandemic (adjusted HR, 0.31 [95% CI, 0.15-0.66]).

Sensitivity Analyses

The sensitivity analyses using 6 months and 18 months (vs 12 months) to define shortages were consistent with the main results (eFigure 11 and eTable 7 in Supplement 1). Reports of supply chain issues had a lower risk of drug shortages in Canada at both 6 months (adjusted HR, 0.55 [95% CI, 0.36-0.83]) and 18 months (adjusted HR, 0.59 [95% CI, 0.40-0.86]). The results were numerically similar for severe shortages (decrease of ≥66%) (adjusted HR, 0.52 [95% CI, 0.28-0.97]; eFigure 12 and eTable 8 in Supplement 1).

In the US, recalls and discontinuations (n = 106 reports) were associated with a lower risk of drug shortages (12-month cumulative incidence of 21.6% [95% CI, 14.4%-31.7%]) compared with reports to the FDA or the ASHP (n = 104 reports) (12-month cumulative incidence of 49.0% [95% CI, 39.3%-59.7%]) (eFigure 13 and eTable 9 in Supplement 1). In Canada, no differences were observed in drug shortage risk for reports to Health Canada that occurred within 180 days of US-reported recalls or discontinuations (12-month cumulative incidence of 32.7% [95% CI, 23.0%-45.0%]) vs reports to Health Canada that coincided with reports to the FDA or the ASHP (12-month cumulative incidence of 34.0% [95% CI, 25.0%-45.0%]; eFigure 13 and eTable 10 in Supplement 1). An analysis limited to reports of supply chain issues with a duration of at least 12 months in both countries found similar results (adjusted HR, 0.43 [95% CI, 0.25-0.75]; eFigure 14 and eTables 11-12 in Supplement 1).

Discussion

In this study comparing the US and Canada, 1 in 12 drugs (8%) purchased in both countries experienced at least 1 report of supply chain issues from 2017 to 2021. Reports were approximately 40% less likely to be associated with drug shortages in Canada within 12 months vs in the US both before and during COVID-19. Certain medication characteristics (including drugs with a sole-source manufacturer) were associated with a higher risk of drug shortages in both countries.

The current findings are consistent with previous reports27 that suggest multiple country overlap of reports of supply chain issues and reflect the global nature of drug supply chains. However, consistent with the results from Mulcahy et al at RAND,1 we observed that the extent and severity of shortages differed across countries. Combined, these findings highlight the need for international cooperation on policy strategies that prevent shortages.1,10 Domestic production of drugs has been proposed as a solution to shortages, but the production of all medications domestically is cost prohibitive and may limit access.10 Importation of drugs on shortage may also decrease access and exacerbate international disparities in drug supply.6,28,29,30 Thus, coordinated or aligned strategies (eg, “nearshoring”) may prove to be beneficial to the global drug supply chain.

There are several potential reasons why we observed a lower risk of shortages in Canada vs in the US even though both countries largely have overlapping and similar regulatory processes.17,30 One key feature of the Canadian system is the level of cooperation between regulatory agencies and provincial public payers, who account for 42% of outpatient drug spending and fund all hospitals.31 This cooperation builds on regulatory frameworks similar to those in the US, but allows for some additional unique features such as coordinated discussions with wholesalers, the ability to limit prescriptions to a 30-day supply, coordinated drug pricing for public payers, expedited review of drugs in shortage, and expansion of the supply chain by allowing private labels.

During drug shortages in Canada, existing relationships enable established committees and task forces to cooperatively prioritize drugs for mitigation efforts. Although the US has some similar policies in place to address drug shortages, the policies may not be leveraged as effectively due to the lack of close cooperation between regulators and other health system partners that exists in Canada. This includes prioritization of tier 3 medications,26 which had a lower risk of shortage in the current study. Differences in stockpiles also could potentially explain the results in the current study. Health Canada developed a national stockpile of drugs likely to be affected by strains to the supply chain during the pandemic,32,33 whereas the US Strategic National Stockpile is intended for use during acute events (eg, terrorism or mass casualty events).34 Although identification of specific policies and strategies that worked in Canada is beyond the scope of this study, the lower risk of drug shortages in Canada suggests that this would be an informative exercise for US policymakers as they consider lessons from other countries in their response to drug shortages.

With drug shortages persisting beyond the end of the COVID-19 public health emergency, the current results are relevant to inform the design of policies that preserve access to essential medications. Although both countries require reporting of supply chain issues,9,13,19 the results suggest that reporting is still suboptimal in the US because the reasons are not standardized and almost 1 in 4 reports had no reason listed on the websites of the FDA and the ASHP. Mandatory reporting in Canada was associated with an almost 10-fold higher number of reports compared with the US and a higher share with information on reasons.

Although these differences may be explained by reporting mechanisms, it is also possible that mandatory reporting results in an increased number of false-positive reports, which do not result in shortages. Increased transparency on other supply chain factors that may increase the risk of drug shortages (eg, ingredient sources, manufacturing locations) remains a legislative priority.10,35 Exemplary policies from other high-income countries (such as New Zealand) include public reporting of the names and locations of all raw ingredient and finished dosage producers.36

Generic drug formulations comprised more than 90% of drug-related reports of supply chain issues in the current study, which is in line with existing evidence that low profitability of certain generic products contributes to drug shortages.5,6 Despite differences in how medical insurance is provided, prescription drug coverage in Canada is similar to that in the US, with approximately half of prescriptions reimbursed through public payers (ie, Health Canada, Medicare) and half by private insurance.37,38,39 Policymakers could consider strategies that create incentives for the manufacture of medically essential drugs with lower profit margins, such as add-on payments by public payers.40 Although total drug spending is higher in the US, Canada has higher per-unit prices on average for generic drugs.41,42 Assessment of the root economic causes of shortages for generic drugs is beyond the scope of the current study. However, future research could explore the role of reimbursement policies and assess the dynamics of pricing on medication supplies and patient access.

One in 12 drugs used in both Canada and the US were found to have at least 1 supply chain issue reported between 2017 and 2021. Although both countries were affected by drug-related supply chain issues during this period, reports were 40% less likely to result in meaningful drug shortages in Canada. These findings highlight the need for international cooperation between countries and may help to inform ongoing policy development to curb the effects of drug shortages.

Limitations

There are several limitations to the current study. First, because our dataset ended in 2021, we could not assess the full implementation of pandemic-related shortage policies. Future work is therefore needed to track responses to the ongoing crisis and the effects of new policies. In addition, future work could explore the dynamics of shortages in specific market segments (such as for controlled substances).

Second, although the MIDAS database is the most comprehensive dataset available, it does not fully capture over-the-counter drugs, several of which had drug shortages. In addition, drug purchases are a reliable but imperfect indicator of medication use. Future work is needed to assess downstream risk to patients when drug shortages occur. Our work explored supply-based drug shortages and may not have captured demand-driven drug shortages, such as the recent shortages with semaglutide.

Third, both countries post and collect reports of supply chain issues, but it remains unclear if there are significant differences in the thresholds for making these reports public. Of note, Canada likely has a lower threshold for reporting and any reports that are submitted are posted, but, importantly, all reports are provided by the manufacturers.

Conclusions

Drug-related reports of supply chain issues were 40% less likely to result in meaningful drug shortages in Canada compared with the US. These findings highlight the need for international cooperation between countries to curb the effects of drug shortages and improve resiliency of the supply chain for drugs.

eFigure 1. Conceptual Model

eFigure 2. Merging Algorithm for FDA, ASHP, and Health Canada Supply Chain Issue Reports

eFigure 3. Unadjusted Cumulative Incidence of Drug Shortages in the U.S. and Canada, by WHO Essential Medicine Status

eFigure 4. Unadjusted Cumulative Incidence of Drug Shortages in the U.S. and Canada, by Canadian “Tier 3” Status

eFigure 5. Unadjusted Cumulative Incidence of Drug Shortages in the U.S. and Canada, by Sole-Source Status

eFigure 6. Unadjusted Cumulative Incidence of Drug Shortages in the U.S. and Canada, by Formulation

eFigure 7. Unadjusted Cumulative Incidence of Drug Shortages in the U.S. and Canada, by Baseline Price per Unit

eFigure 8. Unadjusted Cumulative Incidence of Drug Shortages in the U.S. and Canada, by Age ≥20 Years

eFigure 9. Unadjusted Cumulative Incidence of Drug Shortages in the U.S. and Canada, by Number of Therapeutic Alternatives in ATC3 Class

eFigure 10. Unadjusted Cumulative Incidence of Drug Shortages in the U.S. and Canada, by COVID-19 Pandemic Period

eFigure 11. Unadjusted and Adjusted Cumulative Incidence of Drug Shortages in the U.S. and Canada, 2017-2021, Sensitivity Analyses Using Different Time Periods to Define Drug Shortages

eFigure 12. Unadjusted and Adjusted Cumulative Incidence of Drug Shortages in the U.S. and Canada, 2017-2021, Sensitivity Analyses of Severe (≥66% Decrease) Shortages

eFigure 13. Unadjusted Cumulative Incidence of Drug Shortages in the U.S. and Canada, 2017-2021, Sensitivity Analysis Including U.S. Recalls and Discontinuations

eFigure 14. Unadjusted and Adjusted Cumulative Incidence of Drug Shortages in the U.S. and Canada, 2017-2021, Sensitivity Analysis Restricted to 55 Supply-Chain-Issue Reports with a Duration ≥12 months in Both the U.S. and Canada

eTable 1. Excluded Non-Prescription Products

eTable 2. Covariate Definitions

eTable 3. Characteristics of Combined U.S.-Canadian Supply Chain Issue Reporting Episodes, by Shortage Status

eTable 4. Adjusted Cox Proportional Hazards Model, Time to Drug Shortage in the U.S. and Canada

eTable 5. Characteristics of Combined U.S.-Canadian Supply Chain Issue Reporting Episodes, by COVID-19 Pandemic Period

eTable 6. Adjusted Cox Proportional Hazards Model, Time to Drug Shortage in the U.S. and Canada, by COVID-19 Pandemic Period

eTable 7. Adjusted Cox Proportional Hazards Model, Sensitivity Analyses Using Different Time Periods to Define Drug Shortages

eTable 8. Adjusted Cox Proportional Hazards Model, Sensitivity Analysis of Severe (≥66% Decrease) Shortages

eTable 9. Characteristics of Combined U.S.-Canadian Supply Chain Issue Reporting Episodes, Sensitivity Analysis Including U.S. Recalls and Discontinuations

eTable 10. Adjusted Cox Proportional Hazards Model, Time to Drug Shortage in the U.S. and Canada, Sensitivity Analysis Including U.S. Recalls and Discontinuations

eTable 11. Characteristics of Combined U.S.-Canadian Supply Chain Issue Reporting Episodes, Sensitivity Analysis Restricted to 55 Supply-Chain-Issue Reports with a Duration ≥12 months in Both the U.S. and Canada

eTable 12. Adjusted Cox Proportional Hazards Model, Time to Drug Shortage in the U.S. and Canada, Sensitivity Analysis Restricted to 55 Supply-Chain-Issue Reports with a Duration ≥12 months in Both the U.S. and Canada

Data sharing statement

References

- 1.Mulcahy AW, Rao P, Kareddy V, Agniel DM, Levin JS, Schwam D. Assessing relationships between drug shortages in the United States and other countries. Published October 27, 2021. Accessed September 11, 2024. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA1070-1.html

- 2.Park M, Conti RM, Wosińska ME, Ozlem E, Hopp WJ, Fox ER. Building resilience into US prescription drug supply chains. Accessed August 9, 2024. https://www.healthaffairs.org/content/forefront/building-resilience-into-us-prescription-drug-supply-chains

- 3.Hedlund NG, Isgor Z, Zwanziger J, et al. Drug shortage impacts patient receipt of induction treatment. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(6):5078-5105. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.13028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alpert A, Jacobson M. Impact of oncology drug shortages on chemotherapy treatment. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2019;106(2):415-421. doi: 10.1002/cpt.1390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hernandez I, Sampathkumar S, Good CB, Kesselheim AS, Shrank WH. Changes in drug pricing after drug shortages in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170(1):74-76. doi: 10.7326/M18-1137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alevizakos M, Detsis M, Grigoras CA, Machan JT, Mylonakis E. The impact of shortages on medication prices: implications for shortage prevention. Drugs. 2016;76(16):1551-1558. doi: 10.1007/s40265-016-0651-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vail E, Gershengorn HB, Hua M, Walkey AJ, Rubenfeld G, Wunsch H. Association between US norepinephrine shortage and mortality among patients with septic shock. JAMA. 2017;317(14):1433-1442. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.2841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Devine JW, Tadrous M, Hernandez I, et al. A retrospective cohort study of the 2018 angiotensin receptor blocker recalls and subsequent drug shortages in patients with hypertension. J Am Heart Assoc. 2024;13(1):e032266. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.123.032266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.US Food and Drug Administration . Food and Drug Administration Safety and Innovation Act of 2012. Accessed September 11, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/selected-amendments-fdc-act/food-and-drug-administration-safety-and-innovation-act-fdasia

- 10.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine . Building resilience into the nation’s medical product supply chains. Published 2022. Accessed September 11, 2024. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/26420/building-resilience-into-the-nations-medical-product-supply-chains [PubMed]

- 11.US Food and Drug Administration Drug Shortages Task Force . Drug shortages: root causes and potential solutions. Accessed August 9, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/media/131130/download

- 12.Canadian Institute for Health Information . Prescribed drug spending in Canada, 2018: a focus on public drug programs. Accessed September 11, 2024. https://www.cihi.ca/sites/default/files/document/pdex-report-2018-en-web.pdf

- 13.Health Canada . Mandatory reporting of drug shortages and discontinuances on track for spring 2017 implementation. Accessed August 9, 2024. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/news/2016/06/mandatory-reporting-of-drugs-shortages-and-discontinuances-on-track-for-spring-2017-implementation.html

- 14.Zhang W, Guh DP, Sun H, et al. Factors associated with drug shortages in Canada: a retrospective cohort study. CMAJ Open. 2020;8(3):E535-E544. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20200036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shukar S, Zahoor F, Hayat K, et al. Drug shortage: causes, impact, and mitigation strategies. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:693426. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.693426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.US Food and Drug Administration . Report to Congress: drug shortages CY 2022. Accessed August 9, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/media/169302/download

- 17.Lau B, Tadrous M, Chu C, Hardcastle L, Beall RF. COVID-19 and the prevalence of drug shortages in Canada: a cross-sectional time-series analysis from April 2017 to April 2022. CMAJ. 2022;194(23):E801-E806. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.212070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG, et al. ; STROBE initiative . Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(8):W163-W194. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00010-w1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Health Canada . Drug shortages in Canada: regulations and guidance. Accessed August 9, 2024. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-health-products/drug-products/drug-shortages/regulations-guidance.html

- 20.IQVIA . 2022 ACTS annual report. Accessed August 9, 2024. https://www.iqvia.com/-/media/iqvia/pdfs/library/publications/2022-acts-annual-report.pdf

- 21.US Food and Drug Administration . Recalls, market withdrawals, and safety alerts. Accessed August 9, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/safety/recalls-market-withdrawals-safety-alerts

- 22.American Society for Health-Systems Pharmacists . Current drug shortages. Accessed August 9, 2024. https://www.ashp.org/drug-shortages/current-shortages?loginreturnUrl=SSOCheckOnly

- 23.Health Canada . Drug shortages Canada. Accessed August 9, 2024. https://www.drugshortagescanada.ca/

- 24.Callaway Kim K, Rothenberger SD, Tadrous M, et al. Drug shortages prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(4):e244246. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.4246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gross AE, Johannes RS, Gupta V, Tabak YP, Srinivasan A, Bleasdale SC. The effect of a piperacillin/tazobactam shortage on antimicrobial prescribing and Clostridium difficile risk in 88 US medical centers. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65(4):613-618. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Santhireswaran A, Chu C, Kim KC, et al. Early observations of tier-3 drug shortages on purchasing trends across Canada: a cross-sectional analysis of 3 case-example drugs. PLoS One. 2023;18(12):e0293497. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0293497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Choi Y, Santhireswaran A, Chu C, et al. Effects of the July 2018 worldwide valsartan recall and shortage on global trends in antihypertensive medication use: a time-series analysis in 83 countries. BMJ Open. 2023;13(1):e068233. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-068233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rawson NSB, Binder L. Importation of drugs into the United States from Canada. CMAJ. 2017;189(24):E817-E818. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.170372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suda KJ, Kim KC, Hernandez I, Gellad WF, et al. The global impact of COVID-19 on drug purchases: a cross-sectional time series analysis. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2022;62(3):766-774,e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gaudette É. COVID-19’s limited impact on drug shortages in Canada. Can Public Policy. 2020;46(S3)(suppl 3):S307-S312. doi: 10.3138/cpp.2020-107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brandt J, Shearer B, Morgan SG. Prescription drug coverage in Canada: a review of the economic, policy and political considerations for universal pharmacare. J Pharm Policy Pract. 2018;11(1):28. doi: 10.1186/s40545-018-0154-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dill S, Ahn J. Drug shortages in developed countries—reasons, therapeutic consequences, and handling. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;70(12):1405-1412. doi: 10.1007/s00228-014-1747-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee SK, Mahl SK, Rowe BH, Lexchin J. Pharmaceutical security for Canada. CMAJ. 2022;194(32):E1113-E1116. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.220324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pesik N, Gorman S, Williams WD. The National Pharmaceutical Stockpile Program: an overview and perspective for the Pacific Islands. Pac Health Dialog. 2002;9(1):109-114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Canadian Generic Pharmaceutical Association . International pricing and Canada’s generic prescription medicines 2023. Accessed August 9, 2024. https://canadiangenerics.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/CGPA_International-Pricing-and-Canadas-Generic-Prescription-Medicines-2023.pdf

- 36.Årdal C, Baraldi E, Beyer P, et al. Supply chain transparency and the availability of essential medicines. Bull World Health Organ. 2021;99(4):319-320. doi: 10.2471/BLT.20.267724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Office of Inspector General . Drug spending. Accessed August 9, 2024. https://oig.hhs.gov/reports-and-publications/featured-topics/drug-spending/

- 38.Tadrous M, Martins D, Mamdani MM, Gomes T. Characteristics of high-drug-cost beneficiaries of public drug plans in 9 Canadian provinces: a cross-sectional analysis. CMAJ Open. 2020;8(2):E297-E303. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20190231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Demers V, Melo M, Jackevicius C, et al. Comparison of provincial prescription drug plans and the impact on patients’ annual drug expenditures. CMAJ. 2008;178(4):405-409. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.070587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Senate Committee on Finance . Testimony of Inmaculada Hernandez. Accessed August 9, 2024. https://www.finance.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/1205_hernandez_testimony.pdf

- 41.Bren L. Study: US generic drugs cost less than Canadian drugs. FDA Consum. 2004;38(4):9-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gaudette E. HPR18 international generic availability improvements between 2010 and 2021. Value Health. 2023;26(6):S214. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2023.03.1165 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure 1. Conceptual Model

eFigure 2. Merging Algorithm for FDA, ASHP, and Health Canada Supply Chain Issue Reports

eFigure 3. Unadjusted Cumulative Incidence of Drug Shortages in the U.S. and Canada, by WHO Essential Medicine Status

eFigure 4. Unadjusted Cumulative Incidence of Drug Shortages in the U.S. and Canada, by Canadian “Tier 3” Status

eFigure 5. Unadjusted Cumulative Incidence of Drug Shortages in the U.S. and Canada, by Sole-Source Status

eFigure 6. Unadjusted Cumulative Incidence of Drug Shortages in the U.S. and Canada, by Formulation

eFigure 7. Unadjusted Cumulative Incidence of Drug Shortages in the U.S. and Canada, by Baseline Price per Unit

eFigure 8. Unadjusted Cumulative Incidence of Drug Shortages in the U.S. and Canada, by Age ≥20 Years

eFigure 9. Unadjusted Cumulative Incidence of Drug Shortages in the U.S. and Canada, by Number of Therapeutic Alternatives in ATC3 Class

eFigure 10. Unadjusted Cumulative Incidence of Drug Shortages in the U.S. and Canada, by COVID-19 Pandemic Period

eFigure 11. Unadjusted and Adjusted Cumulative Incidence of Drug Shortages in the U.S. and Canada, 2017-2021, Sensitivity Analyses Using Different Time Periods to Define Drug Shortages

eFigure 12. Unadjusted and Adjusted Cumulative Incidence of Drug Shortages in the U.S. and Canada, 2017-2021, Sensitivity Analyses of Severe (≥66% Decrease) Shortages

eFigure 13. Unadjusted Cumulative Incidence of Drug Shortages in the U.S. and Canada, 2017-2021, Sensitivity Analysis Including U.S. Recalls and Discontinuations

eFigure 14. Unadjusted and Adjusted Cumulative Incidence of Drug Shortages in the U.S. and Canada, 2017-2021, Sensitivity Analysis Restricted to 55 Supply-Chain-Issue Reports with a Duration ≥12 months in Both the U.S. and Canada

eTable 1. Excluded Non-Prescription Products

eTable 2. Covariate Definitions

eTable 3. Characteristics of Combined U.S.-Canadian Supply Chain Issue Reporting Episodes, by Shortage Status

eTable 4. Adjusted Cox Proportional Hazards Model, Time to Drug Shortage in the U.S. and Canada

eTable 5. Characteristics of Combined U.S.-Canadian Supply Chain Issue Reporting Episodes, by COVID-19 Pandemic Period

eTable 6. Adjusted Cox Proportional Hazards Model, Time to Drug Shortage in the U.S. and Canada, by COVID-19 Pandemic Period

eTable 7. Adjusted Cox Proportional Hazards Model, Sensitivity Analyses Using Different Time Periods to Define Drug Shortages

eTable 8. Adjusted Cox Proportional Hazards Model, Sensitivity Analysis of Severe (≥66% Decrease) Shortages

eTable 9. Characteristics of Combined U.S.-Canadian Supply Chain Issue Reporting Episodes, Sensitivity Analysis Including U.S. Recalls and Discontinuations

eTable 10. Adjusted Cox Proportional Hazards Model, Time to Drug Shortage in the U.S. and Canada, Sensitivity Analysis Including U.S. Recalls and Discontinuations

eTable 11. Characteristics of Combined U.S.-Canadian Supply Chain Issue Reporting Episodes, Sensitivity Analysis Restricted to 55 Supply-Chain-Issue Reports with a Duration ≥12 months in Both the U.S. and Canada

eTable 12. Adjusted Cox Proportional Hazards Model, Time to Drug Shortage in the U.S. and Canada, Sensitivity Analysis Restricted to 55 Supply-Chain-Issue Reports with a Duration ≥12 months in Both the U.S. and Canada

Data sharing statement