Abstract

Introduction: The Radical Remission Multimodal Intervention (RRMI) was developed by Kelly A. Turner, PhD, after analyzing more than 1500 cases of cancer survivors experiencing radical remission (a.k.a. spontaneous regression) across all cancer types and extracting key lifestyle factors shared by these cancer survivors. The RRMI workshops provide instruction on these lifestyle factors to participants with cancer and give them tools to help navigate their cancer recovery journey. This pilot study aimed to evaluate the effect of the RRMI on the quality of life (QOL) of people with cancer. Methods: This was a pre-post outcome study. Data were collected, between January 2019 and January 2022, from 200 eligible adults of all cancer types, who attended the RRMI workshops (online and in-person). Participants were asked to complete questionnaires online, at baseline (i.e., before the intervention) and at month 1 and month 6 post-intervention. The RRMI workshops were led by certified Radical Remission health coaches. Participants completed the RRMI with personalized action plans for them to implement. The primary outcome QOL measure was the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy—Spiritual Well-Being Scale (FACIT-Sp). Mixed-effects regression models were used to examine differences in FACIT-Sp score between month 1 and baseline, as well as month 6 and baseline. Models controlled for baseline score, covariates (including age, ethnic group, and body mass index), timepoints (month 1 or 6), training type (online or in-person), adherence score, and interaction between timepoints and adherence score. Results: 92% of participants were women, 77% were Non-Hispanic White, 88% were living in the US, and 66.5% were not living alone. One-quarter had breast cancer. Mean age ± SD was 55.3 ± 11.5 years. Final mixed-effects model analyses showed a significant increase in FACIT-Sp score of 9.5 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 6.2-12.8) points at month 1 (P < .0001) and 9.7 (95% CI: 6.4-13.0) points at month 6 (P < .0001) compared with baseline, a 7.7% and 10.8% improvement, respectively. Conclusion: The RRMI was found to significantly improve the overall QOL of participants at month 1. This improvement was maintained at month 6 post-intervention. Our findings suggest that people with cancer can benefit from the RRMI.

Keywords: radical remission multimodal intervention, RRMI, quality of life, FACIT-Sp, lifestyle factors, integrative oncology, integrative cancer therapies, lifestyle medicine, plant-based diet, integrative medicine

Introduction

Multidisciplinary approaches to cancer treatments have been reported to show improved clinical outcomes among cancer patients.1,2 The goal of the multidisciplinary team which comprises a group of experts and healthcare professionals 2 is to deliver personalized treatment, while also empowering patients in their cancer care. 2 The latter includes educating patients in essential lifestyle factors that has the potential to transform their health, and help maintain or improve their quality of life (QOL).

Lifestyle factors are increasingly accepted in the medical literature to have a positive impact on cancer prevention, prognosis, and survival. 3 Modifiable lifestyle factors including diet, physical activity, stress, social support, sleep, and mind-body connection, among others, have been shown to favorably impact health, including cancer, outcomes. 3 Findings from a study by Ornish et al, 4 suggest that intensive changes in diet and lifestyle could affect the progression of early prostate cancer. Researchers have also shown that a similar plant-based diet and Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) program may help slow the progression of advanced prostate cancer over a period of 4 months. 5 Their findings suggest that the progression of the disease can be slowed or even reversed, without further surgery, radiation, or chemotherapy. 5 Additionally, a 6-month pilot clinical trial investigating the effect of adopting a plant-based diet, reinforced by stress management training, provided preliminary evidence that such lifestyle-factor changes may attenuate disease progression and have therapeutic potential for clinical management of recurrent prostate cancer. 6 These findings showed the potential for modifying cancer progression and outcome with changes in lifestyle factors.

Qualitative research by Turner on more than 1,500 cases of cancer survivors experiencing radical remission, also referred to as spontaneous remission or spontaneous regression,7 -9 has led to the identification of 9 key lifestyle factors which she refers to as “healing factors,” (outlined below) that were consistently reported by cancer survivors of all cancer types who experienced Radical Remission (RR).7,10 The occurrence of RR can be found in most types of cancer and has been defined in the literature as the partial or complete disappearance of a malignant tumor in the absence of treatment, or in the presence of therapy considered insufficient to exert a major influence on the disease progression.11,12

The Radical Remission Multimodal Intervention (RRMI), developed by Kelly A. Turner, Ph.D., comprises the key lifestyle factors she identified in her research on RR survivors.7 -9 According to Turner, thousands of RRMI participants reported in their evaluation forms, upon completion of the RRMI, that the intervention has helped improve the quality of their lives and their coping ability to live with cancer (K. Turner, personal communication, November 21, 2023). QOL is a major concern of cancer patients. People living with cancer experience a variety of challenges and symptoms due to the disease, as well as side effects to the treatments received.13 -16 Cancer pain is one of the greatest causes of reduced QOL in people with cancer. 17 Integrative management strategies, including acupuncture, massage, music therapies, and mind-body practices, have shown promise in reducing cancer pain.18 -20 Addressing QOL, including reducing cancer pain, is an important component of cancer care, as it contributes to enhanced health outcomes and overall well-being of the patient, including decreased treatment side effects and longer survival.16,21 -23 Improving QOL is an integral component of healing or disease recovery. 24

More recently, Turner has trained health coaches in the RRMI in order to educate more people with cancer about these lifestyle factors. We hypothesized that the RRMI will be associated with significant improvement in the QOL of adults with cancer, who participated in structured RRMI workshops, at 6 months after the intervention compared to before. Secondarily, we hypothesized that improvements will also be observed at month 1 post-intervention compared to baseline. Impact of the RRMI on QOL subscale measures such as emotional well-being and social and family well-being, at both month 1 and month 6, was also explored. Additionally, we explored the relationship between adherence to these factors and QOL.

Methods

Study Design

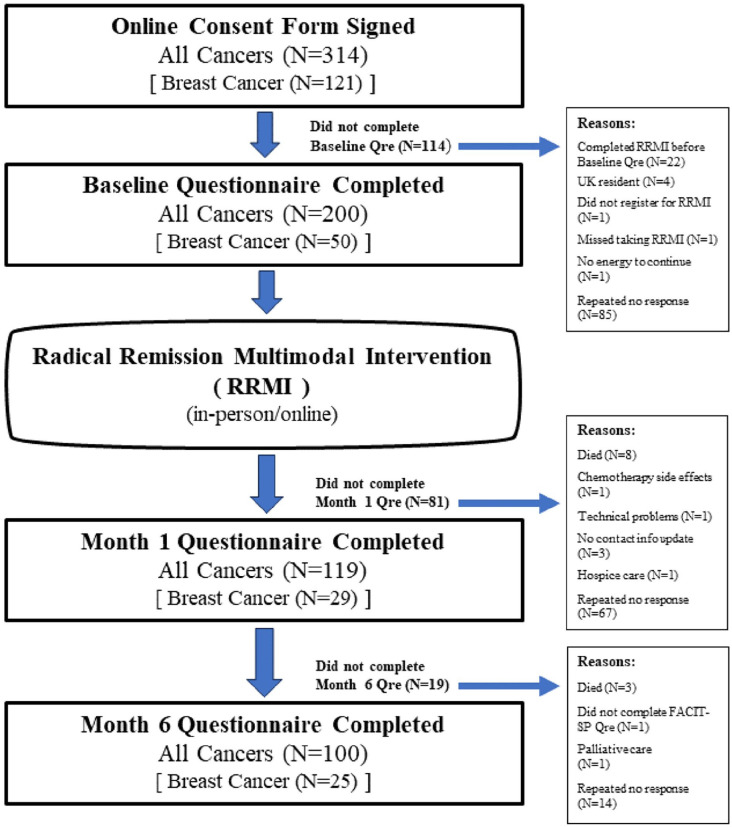

For this pilot study, to test our study hypotheses, and to explore the impact of the RRMI on the QOL subscale measures of our target population, we conducted a prospective pre-post outcome pilot study, between January 2019 and January 2022, on a convenience sample of adults with cancer who attended the RRMI workshops (on-line or in-person). Participants completed online questionnaires at baseline or pre-intervention (i.e., within a week prior to participation in the program), and at least 1 month and 6 months post-intervention. This simple and low-cost study design allows for measuring baseline levels of outcome measures of interest before the intervention and the assessment of how these measures change after the intervention at month 1 and month 6. The study design and participant enrollment flowchart is presented in Figure 1. Through our automated online tracking system and website, HARIS (Harvard Automated Research Information System), all potential participants were provided information about the purpose, any risks involved, and benefits of the study, study eligibility criteria, as well as the importance of their full cooperation if they chose to participate. These details were also included in the consent document, which each participant read and signed online before entering the study. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health (Protocol#: IRB18-1239) on December 10, 2018.

Figure 1.

Study design and participant enrollment flowchart.

Eligibility Criteria and Recruitment

Participants were eligible for the study if they reported having been diagnosed with any cancer (other than non-melanoma skin cancer), aged 18 years or more, are citizens of the United States and non-European countries, had signed-up for the RRMI workshops either online or in-person, and had easy access to broadband internet. Citizens of countries in Europe were excluded due to higher costs needed to conform to the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). 25 Participants were not compensated for their participation.

Study recruitment was undertaken with the assistance of Turner and the Radical Remission Project staff, including through word of mouth, emailing, postering, social media, and advertising. The Radical Remission Project staff also contacted a network of oncology naturopaths, integrative medicine physicians and the Cancer Support Community, among others, to promote the workshops and to recruit participants. All participants who signed up for RRMI were informed about the study and offered an opportunity to participate. Those who expressed interest were provided more information, including eligibility criteria, as well as other pertinent information about the study, as mentioned above. Study staff were also available to answer questions via email or via telephone. Once all questions were answered to the full satisfaction of the potential participants, and if they still agreed to participate, they were asked to type their name and date of consent in the spaces provided, and check a box on the online consent form to indicate their consent.

Participants who signed the online informed consent form, were asked to complete the CSA (Calender of Study Activities) questionnaire where, among others, they indicated when their workshop will start and when the workshop will end. Based on the information provided, HARIS generated a CSA for each participant. Participants were provided with a schedule of when they were due to complete their baseline, month 1 and month 6 questionnaires. They were also reminded at least 3 times to complete their baseline (pre-intervention), and month 1 and month 6 (post-intervention) questionnaires. Those failing to complete their questionnaires were contacted by the study Research Coordinator to inquire if they needed help completing the questionnaires so assistance could be provided if needed. Participants were free to indicate at any time if they preferred not to answer any questions on the study questionnaires, or not to proceed with the study. Participants needing medical support were referred to their treating physicians or primary care physicians. Those needing psychological support, were provided a toll-free psychological help number to call if they were in distress. Participants were informed to report to study personnel should there be any issues related to their participation in the study. Any issues presented were reported in the event evaluation form and submitted to the Institutional Review Board of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. Among other information, this form included space for a description of the issue, a classification of seriousness, and assessment of potential relationship to the intervention. Summaries of non-serious adverse events were submitted to the Institutional Review Board of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health at least annually at continuing review.

Sample Size and Power Calculation

The primary outcome measure of interest was the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy—Spiritual Well-Being Scale (FACIT-Sp) 26 score. Our initial sample size estimation showed that 43 people with cancer would provide 80% power at a two-sided 5% level of significance to detect an effect size of 0.44 point in the change of FACIT-Sp scores between baseline and 6 months after completing a 9-week intervention. 27 This change was observed in a study between groups of cancer patients receiving early palliative care and those not receiving the intervention over a period of 4 months. 27 We expected a dropout rate of 25%. Hence a minimum of 57 participants were needed to ensure that we meet our minimum sample size of 43 participants for this study. Due to high response rate to recruitment efforts, we received IRB approval to enroll more than 57 participants. Data collected from 200 people with various cancer types were used in the study analyses (Figure 1). To avoid multiple testing, analysis of available cases focused on changes observed at the primary timepoint of 6 months. Secondarily, we examined changes observed at 1 month following completion of the RRMI. We also examined the impact of the RRMI on a sub-group of 50 participants with breast cancer at 1 month and at 6 months post-intervention compared to baseline (Figure 1).

The Radical Remission Multimodal Intervention (RRMI)

The RRMI was developed to teach the 9 lifestyle factors from the book Radical Remission 10 to participants living with cancer and to guide them to implement healthful lifestyle changes in their cancer recovery journey. In 2020, as a result of Turner and White’s additional analysis of 500 new RR cases from 2014 to 2020, a 10th lifestyle factor–exercise/movement—was added to the RRMI. 28 However, the 10th lifestyle factor, which is also very important for cancer recovery29,30 was not included in this evaluation because this factor was added after study implementation was initiated. The 9 lifestyle factors evaluated in this study are:

Having strong reasons for living,

Embracing social support,

Using herbs and supplements,

Radically changing your diet,

Releasing suppressed emotions,

Following your intuition,

Increasing positive emotions,

Taking control of your health (a.k.a. empowerment), and

Deepening your spiritual connection.

A summary of the RRMI lifestyle factors, main points, aims, and activities provided by Turner and her coaches are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Radical Remission Multimodal Intervention: Lifestyle Factors, Main Points, Aims and Activities.

| Lifestyle factor # | Main point | Aim | Activity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Having Strong Reasons for Living | The RRS* research showed that “having a strong reason for living” is very different from “not wanting to die.” Some were afraid of death, while others had accepted the possibility, but the one thing they all had in common was a strong commitment to life. | This session aims to help participants identify their purpose or strong reasons for living. Tools provided to help participants identify their strong commitment to life included a visualization of long-term versus short-term life goals. After reflecting and comparing the two, purpose begins to arise and they are able to identify reasons they want to live (people they want to spend time with, places they want to travel, personal experiences and goals they want to achieve). After the reflection, they are asked to set goals to help them stay accountable to implementing their purpose. Additionally, a discussion is facilitated about meaning, purpose, and joy. | The participants are asked to imagine two scenarios and write detailed descriptions of their life in each. 1. Imagine that you have perfect health, $20 billion, and are guaranteed wild success in whatever you choose to do. How would you spend the rest of your life? 2. Imagine that in exactly 1.5 y, you will die unexpectedly without any prior symptoms. Your financial situation is the same as it is now. How will you spend the next 1.5 y? Finding similarities between the two scenarios would lead them to identify their strong reasons. |

| Embracing Social Support | RRS described receiving love and support as a different skill than giving love and support. You can be good at one (usually giving) and not good at the other. | This session aims to help participants identify their strongest and weakest forms of support from the people in their lives. Tools provided to help participants identify and appreciate the roles that their friends, family, co-workers, etc., play in their healing, include strategies to engage support in specific ways that focus on the positive aspects of these relationships and reduce expectations that may have a negative impact. A discussion about giving support versus receiving support and the importance of balance between the two. | A “Healing Circle or Energy Circle” group is formed, and a worksheet is provided to explore positive sources of support, as well as weaker areas that may need to be made stronger. |

| Using Herbs & Supplements | Under the guidance of a trained professional the three main categories of supplements that RRS took were identified as immune-boosting, detoxifying, and improving digestion and absorption of nutrients. Emphasis is made to work with a licensed professional for testing and assessment. | This session aims to help participants understand the role of the three supplement categories that arose in the research: immune-boosting, detoxifying, and digestive. Tools are provided to help participants gain knowledge and understanding of these types of supplements and why to discuss them with their practitioner. Additional discussion is facilitated about how to research and find a licensed, prescribing practitioner. | Discussion is made of a very small sampling of supplements that RRS take in the three aforementioned categories, with a worksheet to make notes of personal information in this area and then further discussion with partners or small groups. Resources for finding a qualified professional are included on the worksheet. |

| Radically Changing Your diet | RRS made many different changes when it came to their diets, many of them very specific (e.g., vegan, ketogenic, etc.), but the overall sweeping trends were that they all greatly reduced (or sometimes eliminated) meat, wheat (meaning gluten or refined grains), sweets (refined sugars), and dairy products. They replaced these things with vegetables and fruit, with at least 50% of each meal or snack being comprised of vegetables or fruits. RRS also drank filtered water. | This session aims to help participants identify the different dietary theories adopted by RRS. Tools are provided to help participants review their current diet and how to improve the quality of their meals and snacks by adding in more fruits, vegetables, and filtered water. | The participants are asked to reflect on their last three meals and diagram them as a pie chart indicating how much of that meal/plate consisted of vegetables, fruit, grains, proteins, etc. The second step is to reimagine an improved meal with ½ the plate vegetables or fruit, and approximately ¼ protein, and ¼ grain or healthy fat. |

| Releasing Suppressed Emotions | The RRS talked about how illness represents a blockage at either the body, mind, or spirit level. In contrast, they talked about how health represents movement or freedom. This is a theory, not a proven fact, but it was something that came up in every interview Dr. Turner conducted. The emphasis is on the need to feel all feelings completely and then release them fully. | This session aims to help participants define the term suppressed emotions (stress, trauma, nostalgia etc.). Tools provided help participants identify areas in their life that create emotional blockages, how to feel them in their bodies, and then how to effectively release them. | Simple instruction is provided on the autonomic nervous system and a sample of Emotional Freedom Technique (EFT) as a means of managing stress. The worksheet asks them to explore situations that may be causing them stress, anxiety, feelings of sadness, anger or resentment, and then think of ways they can healthfully release those feelings and emotions. |

| Following Your Intuition | Intuition is part of the human body–it is located in the cerebellum and also in the gut. There are over 100 million neurons (similar cells that are in your brain) in your gut, and recent research has shown that the neurons in your gut can act independently of your brain – which is why we can get a “bad feeling in our gut.” | This session aims to guide participants to hone and trust their intuition. Tools provided to help participants do this include simple suggestions to listen and note down the feeling/instinct and the results of acting on it or not acting on it. | Guided Imagery is facilitated to get participants in a very relaxed state and lead them on a journey to access their internal wisdom/intuition in which they are asked to use their imagination to go to a safe place and receive a message from a being or creature. The message received is what their intuition is trying to tell them. |

| Increasing Positive Emotions | RRS described this factor as a muscle that needs daily exercise, and they reported it became easier to feel joyful and happy with daily practice. When your body feels stress or fear, it goes into “fight-or-flight” mode, and therefore cannot heal itself. Positive emotions help you get out of this frame of mind and into a “rest and repair” state, which significantly improves your immune system’s ability to heal. | This session aims to demonstrate the value and importance of the mind-body connection. Tools provided include a short guided imagery session in which participants imagine sucking on a lemon slice and then they are asked how their body responded. Unanimously the response is puckering or salivating. | Through laughter yoga, funny photos or jokes, the participants are asked to laugh “for their own health.” They are also asked to list 20 things they are grateful for and 20 happy memories. After completing this they are asked to pick two things they will make time for in the coming week(s). |

| Taking Control of Your Health (Empowerment) | RRS moved from being passive to being active, if they were not active to begin with. They “assumed responsibility for all aspects of their lives, including recovery: thus, medical personnel were often referred to as consultants.” | This session aims to demonstrate the importance of being active, rather than passive, when it comes to their health care. Tools provided to help participants determine their level of active involvement include visualizing their health care team as a board of directors with themselves as the CEO. Additionally, participants are encouraged to check in on their mindset about their healing team and to consider their doctors as experts in their field of expertise, rather than as experts on their bodies. They are also briefed on how to use PubMed to research their diagnosis and treatment. | Participants are asked to complete an Empowerment Wheel in which they rate their satisfaction and wholeness with different aspects of their life, such as health, happiness, purpose, family, etc. They are then asked to share the results and pick an aspect they would like to strengthen as a way to foster empowerment in life. |

| Deepening Your Spiritual Connection | RRS reported that connection with something larger than the self led to instantaneous beneficial effects on their bodies and emotions. Many practiced once a day, and described their spiritual connection practice as a physical and emotional experience, not a set of beliefs. | This session aims to demonstrate the many ways that individuals use to connect to something larger than themselves, and that by doing so they may release stress and embody peace. Tools are provided to help participants identify their spiritual practice including a discussion of ways to connect to nature, through creative endeavors, and the practice of meditation and prayer. Additionally, information is provided on how epigenetics affects gene expression and ways that meditation can reduce stress and turn on health-promoting genes. | The participants are led through three different types of secular meditations so they can experience different types. They are then asked to write about how they felt and which practice they liked best. |

| Exercise & Movement** | RRS moved their bodies or exercised regularly, as soon as they were strong enough and physically able. Exercise did come up as a healing factor in initial RR research but wasn’t a factor all survivors utilized to the fullest extent based on the notion that exercise must be strenuous. Upon further review of old and new cases, Dr. Turner found that all RRS added exercise and movement back into their routines as soon as they were strong enough and able to do so. | This session aims to have participants reframe exercise from something strenuous and intense to any physical movement, such as household activities, daily walks, etc. Tools provided to help participants include tips on making exercise a lifelong habit, discussion on the importance and types of daily movement, and that simply the perception of movement can have physical beneficial effects. | Participants are invited to participate in chair yoga, lymph drainage exercises, or some other type of group movement. The worksheet engages participants in discussion of options for adding movement and physical activity in their daily routines. |

In general, the RR workshop is offered at a minimum of 10 instructional hours, and typically 1 hour is devoted per module (that is, 1 hour per healing factor, and there are 10 healing factors). Those 10 hours can be offered over the course of 2 weekend days (for example, Saturday and Sunday), often with additional hours of instruction offered before and after each days’ modules in order to allow for introduction time and conclusion/goal-setting time. A typical weekend RR workshop runs from 9 am to 5 pm on Saturday and Sunday. If the RR workshop is offered over 6 weeks, it is typically offered - for example - on Tuesday evenings from 6 to 8 pm over the course of 6 consecutive weeks (for a total of 12 hours of instruction).

RRS: Radical Remission Survivors

Although this factor is not part of the evaluation in this study, it is now an important part of the RRMI lifestyle factors identified by Turner, and thus is added to this table to present the current complete intervention.

The study intervention consisted of the RRMI workshops, offered in English, with a specific curriculum to teach the 9 lifestyle factors. The length of the workshops, conducted either in-person or online (live or pre-recorded), varies (~10-20 hours long) depending on whether they were offered over the weekend, or over a period of 6 or more weeks, with a range of 4 to 150 participants per workshop. The larger workshops were broken into smaller groups during specific sections of the workshop wherein group interaction was encouraged. The 9 lifestyle factors were presented in varying order in each RRMI workshop, as there is no order of importance known at this time to indicate 1 factor being more beneficial than another. The priority of the factors is specific to each individual and where they feel they most need to make changes.8,10,28

The workshops were led by certified RR health coaches. In order to be accepted into the RR Health Coach and Workshop Instructor Training, all applicants must already be licensed psychotherapists, psychologists, doctors, nurses, social workers, mental health counselors, or certified life or health coaches from a program accredited either by the National Board Certified Health & Wellness (NBHWC) or the International Coaching Foundation (ICF). Exceptions are made for individuals with substantial mental health counseling experience (e.g., a pastor with 20 years of experience).

The RR health coaches were trained to present the proprietary workshop slides by Turner and her senior coaches in a 40-hour training program. The program also involves 10 additional hours of practice coaching and studying for the final exam. Coaches were educated on the material as well as on how to facilitate each activity with the intent to help participants create a personal “game plan,” that is, a list of micro-goals in order to implement each factor into daily life after the conclusion of the workshop.

Through social support and group interaction, the coaches led group discussions to encourage the sharing of personal experiences, resources, success stories, and obstacles. Important workshop components included activity worksheets for each lifestyle factor to guide each participant to brainstorm actions for how that particular factor could be implemented. Additionally, a summary “game plan” worksheet was provided and completed during the workshop, where each participant set 1-week, 1-month, 6-month, and 12-month personalized goals to outline action steps to be followed at the end of the workshop. Typically, the trainers do not receive many follow-up questions post-intervention, other than some brief follow-up questions via email.

Training duration, as reported by participants, varied and details are presented in Supplemental Table 1. Overall, 68% of participants completed the intervention (in-person or online) in less than 2 weeks. Given training duration was not normally distributed, and most participants completed the 10-hour intervention in less than 2 weeks, this cut off point (i.e., <2 weeks or ≥2 weeks) was used to include training duration as a bivariate variable in the mixed-effects regression analyses models described below.

Data Collection

Data were collected online and tracked using the Harvard Automated Research Information System (HARIS) administered and managed by Aumtech. 31 HARIS is an automated research tracking system used to track about 1400 participants of the Lifestyle Validation Study at Harvard over a period of 4 years. 32 HARIS and its related website were adapted for use with the current study. It reminded participants to complete all study questionnaires at designated pre-agreed timepoints. At baseline, month 1 and month 6, HARIS automatically emailed reminders as well as provided a link to the questionnaires that were due to be completed at that time point.

Data were collected using the following questionnaires at baseline, and at a minimum of 1 month post-intervention (mean = 62 days; range = 30-165 days) and 6 months post-intervention (mean = 250 days; range = 180-516 days).

Calendar of Study Activities Questionnaire: Questions asked included the start and end dates of the RRMI workshops, name(s) of the coach(es), and participants’ cancer types.

Participant Information Questionnaire: Questions asked included birthdate, education status, annual income, ethnicity, marital status, and living situation.

Disease Diagnosis and Treatment Questionnaire: Questions asked included type(s) of cancer diagnosed, treatments, if received (conventional and/or alternative), and dates when these treatments were received.

Quality of Life (QOL) Questionnaire: The QOL Questionnaire that constitutes the primary outcome used for this study is the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy—Spiritual Well-Being Scale (FACIT-Sp). 26 The FACIT-Sp scale measures spiritual well-being in cancer patients, across a wide range of religious traditions, including those who identify themselves as “spiritual yet not religious.” 26 The FACIT-Sp includes (1) the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy - General (FACT-G) (a 27-item questionnaire designed to measure 4 domains of health-related QOL in cancer patients: physical well-being (PWB), social and family well-being (SWB), emotional well-being (EWB), and functional well-being (FWB);26,33 and (2) the spiritual well-being subscale referred to as the FACIT-Sp-12 consisting of 12 items and 3 sub-domains (peace, meaning, and faith).34,35 A total FACT-G score is obtained by summing individual subscale scores (PWB + EWB + SWB + FWB). The FACT-G and the FACIT-Sp-12 scores were computed as previously specified. 36 Scoring took into consideration missing values also as specified. 36 A total FACIT-Sp score is derived by summing the FACIT-G scores and the FACIT-Sp-12 scores; 37 score ranges from 0 to 156, with higher scores indicating better QOL.26,33

Participation and Practice Questionnaire: Questions asked included information on which modules were completed, as well as the degree to which lessons learned in each module were practiced following completion (based on a scale of 0 to 10, where 10 means practiced fully, and 0 not practiced at all). Hence, for the 9 modules, total maximum achievable adherence score is 90. Missing responses to any module were imputed using the averaged score for all other completed responses.

Medical Records: Medical records were requested from study participants who reported they were diagnosed with breast cancer at baseline, and at 6 months (if updated records were available, and participants were willing to share). Data of interest from medical records would include date at diagnosis; disease stage at first diagnosis; and details of the tumors. However, the number of medical records obtained were too few, and hence available data were very limited and could not be used for this study.

Statistical Analysis

Summary statistics including percentages, means, and standard deviations were used to describe the RRMI as reported by study participants (Supplemental Table 1), and to describe participant characteristics, including BMI, cancer diagnosis, and treatments used at baseline, month 1, and month 6 (Table 2). Supplemental Table 2 presents the characteristics of participants with breast cancer using similar summary statistics.

Table 2.

Characteristics of All Cancer Participants in the RRMI Study at Baseline (Pre-Intervention), and at Month 1 and Month 6 (Post-Intervention).

| Characteristics | Baseline (N = 200) | Month 1 (N = 119) | Month 6 (N = 100) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (Mean ± SD) | 55.3 ± 11.5 | 54.8 ± 11.5 | 56.3 ± 10.7 |

| Weight, kg (Mean ± SD) | 66.4 ± 14.8 | 66.5 ± 15.4 | 66.5 ± 14.4 |

| Height, cm (Mean ± SD) | 165.3 ± 7.7 | 165.2 ± 7.4 | 164.8 ± 6.8 |

| BMI, kg/m2 (Mean ± SD) | 24.2 ± 4.7 | 24.3 ± 4.8 | 24.4 ± 4.7 |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Female | 184 (92.0%) | 110 (92.4%) | 95 (95.0%) |

| Male | 16 (8.0%) | 9 (7.6%) | 5 (5.0%) |

| Ethnic Group, n (%) | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 154 (77.0%) | 94 (79.0%) | 81 (81.0%) |

| Other | |||

| Asian | 5 (2.5%) | 2 (1.7%) | 1 (1.0%) |

| Black or African American | 5 (2.5%) | 2 (1.7%) | 2 (2.0%) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 3 (1.5%) | 2 (1.7%) | 1 (1.0%) |

| Multi | 12 (6.0%) | 7 (5.9%) | 4 (4.0%) |

| Missing | 21 (10.5%) | 12 (10.1%) | 11 (11.0%) |

| Educational Status, n (%) | |||

| Above college | 99 (49.5%) | 64 (53.8%) | 50 (50.0%) |

| College or below | 86 (43.0%) | 47 (39.5%) | 42 (42.0%) |

| Missing | 15 (7.5%) | 8 (6.7%) | 8 (8.0%) |

| Living Situation, n (%) | |||

| Not living alone | 133 (66.5%) | 83 (69.8%) | 67 (67.0%) |

| Living alone | 54 (27.0%) | 28 (23.5%) | 25 (25.0%) |

| Missing | 13 (6.5%) | 8 (6.7%) | 8 (8.0%) |

| Country of residence, n (%) | |||

| US | 176 (88.0%) | 105 (88.2%) | 88 (88.0%) |

| Non-US | |||

| Australia | 3 (1.5%) | 2 (1.7%) | 2 (2.0%) |

| Canada | 9 (4.5%) | 6 (5.0%) | 4 (4.0%) |

| Kuwait | 1 (0.5%) | 1 (0.8%) | 1 (1.0%) |

| New Zealand | 4 (2.0%) | 3 (2.5%) | 3 (3.0%) |

| South Africa | 1 (0.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Other | 3 (3.0%) | 1 (0.8%) | 2 (2.0%) |

| Missing | 3 (3.0%) | 1 (0.8%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Use of Treatment, n (%) | |||

| Conventional treatment alone | 20 (10.0%) | 7 (5.9%) | 8 (8.0%) |

| Alternative treatment alone | 18 (9.0%) | 13 (10.9%) | 12 (12.0%) |

| Both treatments | 53 (26.5%) | 27 (22.7%) | 23 (23.0%) |

| None | 10 (5.0%) | 7 (5.9%) | 8 (8.0%) |

| Missing | 99 (49.5%) | 65 (54.6%) | 49 (49.0%) |

| Income, n (%) | |||

| Below USD 100 K per year | 75 (37.5%) | 46 (38.7%) | 42 (42.0%) |

| USD 100 K or more per year | 75 (37.5%) | 43 (36.1%) | 32 (32.0%) |

| Missing | 50 (25.0%) | 30 (25.2%) | 26 (26.0%) |

| Cancer Diagnosis, n (%) | |||

| Breast Cancer | 50 (25.0%) | 29 (24.4%) | 25 (25.0%) |

| Non-Breast Cancer | 150 (75.0%) | 90 (75.6%) | 75 (75.0%) |

| Colon/Rectal | 11 (5.5%) | 5 (4.2%) | 4 (4.0%) |

| Leukemia | 3 (1.5%) | 2 (1.7%) | 1 (1.0%) |

| Lymphoma | 8 (4.0%) | 6 (5.0%) | 5 (5.0%) |

| Ovary | 10 (5.0%) | 4 (3.4%) | 5 (5.0%) |

| Prostate | 5 (2.5%) | 4 (3.4%) | 3 (3.0%) |

| Skin | 14 (7.0%) | 10 (8.4%) | 10 (10.0%) |

| Other | 45 (22.5%) | 25 (21.0%) | 20 (20.0%) |

Characteristics of all cancer participants who provided data at month 1 and those who did not were compared using t-tests for continuous and normally distributed variables and Fisher’s exact tests or Chi-square tests for categorical variables (Supplemental Table 3). This analysis was also conducted for participants who provided data at month 6 and those who did not (Supplemental Table 3). As mentioned, the primary QOL outcome measure was the FACIT-Sp scores, while other outcome measures (i.e., FACIT-G, PWB, EWB, SWB, FWB, and FACIT-Sp-12) were secondary. The distributions of the differences and percentage differences in FACIT-Sp and other scores, between month 1 and baseline, as well as between month 6 and baseline, were examined. Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were applied as some of these measures did not follow a normal distribution.

Longitudinal patterns were studied using mixed-effects models. The outcome measures in these models were differences in scores between month 1 and baseline, and between month 6 and baseline. All models included timepoints (month 1 or month 6), training type (online or in-person), adherence score, and interaction between timepoints and adherence score, along with the corresponding baseline scores as fixed effects and participants as random effects. Potential covariates considered were age, BMI, gender (male or female), ethnic group (Non-Hispanic White or Other), education (college and below or above college), living situation (living alone or not living alone), training duration (<2 weeks or ≥2 weeks), country of residence (US or Non-US), use of conventional medicine (yes or no), and use of alternative medicine (yes or no). Those who received both treatments were coded as “yes” within each treatment category, and those did not receive any treatment were coded as “no” within each treatment category. Only covariates that were significantly associated with each outcome measure were included in the final models (Tables 3 and 4). Supplementary models also considered age, BMI and ethnic group, as the published literature suggested their potential association with the QOL scores 38 (Supplementary Table 4). To ensure the validity of the models, residual plot analyses were performed, revealing no major violations of model assumptions. Effect sizes were calculated for the differences and percent differences in the primary QOL outcome measure, FACIT-Sp scores. Similar analyses were conducted on our sub-sample of women with breast cancer (all breast cancer participants were females, as such gender was not included in the model as a covariate) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Facit-Sp Total Score of All Cancer and Breast Cancer Participants at Baseline (Pre-Intervention), and at Month 1 and Month 6 (Post-Intervention).

| Baseline | Month 1 | Month 6 | Difference between month 1 and baseline | Percent difference between month 1 and baseline | Difference between month 6 and baseline | Percent difference between month 6 and baseline | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer Type | N | Mean (SD) | N | Mean (SD) | N | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) effect size | Unadjusted P-value* | Fitted mean (95% CI) | Adjusted P-value** | Mean (SD) effect size | Mean (SD) effect size | Unadjusted P-value* | Fitted mean (95% CI) | Adjusted P-value** | Mean (SD) effect size |

| All Cancer | 199 | 110 (22.9) | 117 | 119 (20.5) | 100 | 119 (23.3) | 7.0 (13.1) 0.53 |

<.0001 | 9.5 (6.2, 12.8) | <.0001 | 7.7 (14.1) 0.55 |

9.0 (18.6) 0.48 |

<.0001 | 9.7 (6.4, 13.0) | <.0001 | 10.8 (26.5) 0.41 |

| Breast Cancer | 50 | 109 (27.5) | 29 | 121 (18.5) | 25 | 117 (22.8) | 9.2 (14.3) 0.64 |

0.0015 | 14.2 (6.9, 21.5) | 0.0008 | 11.1 (17.3) 0.64 |

6.7 (21.3) 0.31 |

0.2727 | 8.4 (1.0, 15.9) | 0.0287 | 13.2 (43.5) 0.30 |

Unadjusted P-values were from Wilcoxon signed rank test.

Adjusted P-values were from the mixed-effects regression analyses. All mixed-effects models included timepoint (month 1 or month 6 post-intervention), training type (in-person or online), adherence score, adherence score by timepoint interaction, and corresponding baseline measure as fixed effects. Model for emotional well-being also included an additional covariate, living situation (living alone or not living alone), as a fixed effect.

Table 4.

Other Quality of Life Measures of All Cancer Participants at Baseline (Pre-Intervention), and at Month 1 and Month 6 (Post-Intervention).

| Baseline | Month 1 | Month 6 | Difference between month 1 and baseline | Percent difference between month 1 and baseline | Difference between month 6 and baseline | Percent difference between Month 6 and Baseline | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome Measures | N | Mean (SD) | N | Mean (SD) | N | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Unadjusted P-value* | Fitted Mean (95% CI) | Adjusted P-value** | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Unadjusted P-value* | Fitted mean (95% CI) | Adjusted P-value** | Mean (SD) |

| FACT-G score | 199 | 76.3 (15.6) | 118 | 81.9 (14.3) | 100 | 81.8 (16.3) | 3.6 (9.3) | <.0001 | 5.2 (3.0, 7.4) | <.0001 | 5.9 (13.6) | 4.8 (11.9) | .0002 | 5.5 (3.2, 7.7) | <.0001 | 7.8 (20.0) |

| Physical well-being (PWB) score | 200 | 21.6 (5.7) | 118 | 22.6 (5.4) | 100 | 22.7 (5.3) | 0.1 (4.3) | .4490 | 0.3 (−0.6, 1.1) | .5308 | 4.1 (28.3) | 0.2 (3.5) | .6384 | 0.4 (−0.4, 1.2) | .3155 | 2.5 (22.0) |

| Social Well-Being (SWB) score | 200 | 20.0 (5.3) | 119 | 20.7 (5.3) | 100 | 20.5 (5.4) | 0.6 (3.5) | .1050 | 0.9 (0.1, 1.8) | .0282 | 4.9 (21.8) | 1.0 (4.6) | .0465 | 1.0 (0.1, 1.8) | .0274 | 9.1 (30.7) |

| Emotional Well-Being (EWB) score | 199 | 16.4 (4.5) | 119 | 18.6 (3.4) | 100 | 18.5 (3.8) | 1.8 (3.3) | <.0001 | 1.7 (1.0, 2.4) | <.0001 | 18.6 (39.1) | 2.1 (3.8) | <.0001 | 1.6 (0.9, 2.3) | <.0001 | 21.4 (41.2) |

| Functional Well-Being (FWB) score | 200 | 18.4 (5.3) | 119 | 20.1 (4.9) | 100 | 20.2 (5.7) | 1.1 (3.9) | .0042 | 1.9 (1.0, 2.9) | .0001 | 9.6 (27.0) | 1.5 (5.3) | .0026 | 2.0 (1.0, 2.9) | .0001 | 13.0 (34.8) |

| Sp12 total score | 199 | 33.2 (9.3) | 118 | 37.2 (7.8) | 100 | 37.4 (8.6) | 3.3 (6.2) | <.0001 | 4.1 (2.8, 5.4) | <.0001 | 20.5 (81.0) | 4.3 (8.3) | <.0001 | 4.0 (2.7, 5.4) | <.0001 | 34.8 (152) |

| Meaning score | 200 | 12.6 (3.3) | 119 | 13.7 (2.7) | 100 | 13.5 (3.2) | 0.9 (2.3) | <.0001 | 1.3 (0.9, 1.7) | <.0001 | 13.9 (38.9) | 0.9 (2.8) | .0014 | 0.9 (0.5, 1.4) | <.0001 | 15.7 (58.3) |

| Peace score | 200 | 10.3 (3.5) | 119 | 11.7 (2.9) | 100 | 11.9 (3.1) | 1.1 (2.5) | <.0001 | 1.4 (0.9, 1.9) | <.0001 | 17.0 (35.6) | 1.7 (3.1) | <.0001 | 1.5 (1.0, 2.0) | <.0001 | 23.0 (58.7) |

| Faith score | 199 | 10.8 (4.4) | 118 | 12.2 (3.7) | 100 | 11.9 (4.1) | 0.9 (2.8) | .0010 | 1.3 (0.7, 2.0) | <.0001 | 23.3 (91.3) | 1.4 (3.2) | <.0001 | 1.4 (0.7, 2.0) | <.0001 | 36.1 (117) |

FACT-G: Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy—General. FACT-G = Physical well-being (PWB) + social and family well-being (SWB) + emotional well-being (EWB) + functional well-being (FWB). FACIT-Sp-12 = Meaning score + Peace score + Faith score. FACIT-Sp total score or FACIT-Sp score = FACT-G score + FACIT-Sp-12 score (FACIT-Sp score ranges between 0 and 156; higher score means better QOL).

Unadjusted P-values were from Wilcoxon signed rank test.

Adjusted P-values were from the mixed-effects regression analyses. All mixed-effects models included timepoint (month 1 or month 6 post-intervention), training type (in-person or online), adherence score, adherence score by timepoint interaction, and corresponding baseline measure as fixed effects. Model for emotional well-being also included an additional covariate, living situation (living alone or not living alone), as a fixed effect.

Two-sided tests with a type I error of 0.05 were used. Since FACIT-Sp scores were the only primary outcome, no multiple comparison adjustment was made. All analyses were conducted using SAS Version 9.4.

Results

Table 2 displays the characteristics of all cancer participants recruited at baseline (pre-intervention), and month 1 and month 6 post-intervention. At baseline, the majority of participants were women (92%), Non-Hispanic White (77%), living in the US (88%), and not living alone (66.5%). The percentage of income < or ≥100 000 USD were similar (37.5% and 37.5%). The mean age ± SD was 55.3 ± 11.5 years, and the mean BMI ± SD was 24.2 ± 4.7. About 50% of the participants had above-college education. A diagnosis of breast cancer was reported by 25% of participants (characteristics of breast cancer participants are presented in Supplemental Table 2). Twenty participants (10.0%) received conventional treatments alone, while 18 (9.0%) received alternative treatment methods alone; 53 (26.5%) participants utilized both treatment methods. The number of participants who completed study questionnaires at month 1 and month 6 were 119 and 100, respectively (Table 2), although not all participants answered every question on the FACIT questionnaires. Characteristics of participants who did not complete month 1 and month 6 questionnaires are shown in Supplemental Table 3. The only significant difference in the distribution of participants across baseline characteristics, between the groups of participants who did and did not provide data (at month 1 and at month 6), was in the type of treatments received, and only between the groups of participants who did and did not complete data at month 1 (Fisher’s exact test; P = .047). Out of a maximum adherence score of 90, the average score ± SD at month 1 was 68.4 ± 20.7 and at month 6 was 72.5 ± 20.0.

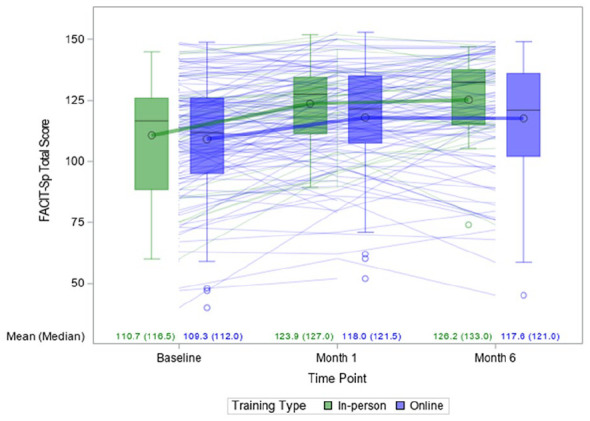

On average, all cancer participants had a 7.0 ± 13.1 point improvement (7.7% increase, effect size = 0.53) on FACIT-Sp scores at month 1 and a 9.0 ± 18.6 point improvement (10.8% increase, effect size = 0.48) at month 6, compared with baseline, when unadjusted for other covariates (P < .0001 in both cases) (Table 3). The mixed-effects model regression analyses controlling for baseline FACIT-Sp score, timepoints, training type, adherence score, and timepoints and adherence score interaction, showed similar findings as the unadjusted analyses (Table 3). Although the distribution of participants across treatments received differed between those who did and did not provide data at month 1 (Supplemental Table 3), the use of conventional medicine (yes or no) and use of alternative medicine (yes or no) were not found to be significantly associated with outcome measures of interest. Thus, as mentioned above, these variables, and others found not to be significantly associated with outcomes measures of interest, were excluded from the final models. The improvement in FACIT-Sp scores remained consistent (estimated difference in score between month 1 and baseline = 9.5 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 6.2-12.8; P < .0001) and between month 6 and baseline = 9.7 (95% CI: 6.4-13.0; P < .0001). The improvement did not differ significantly between training types (P = .13; Figure 2). Gender was also found not to have a significant effect (P = .2364).

Figure 2.

Boxplot and trajectory of FACIT-Sp* total scores over time by training type.

*FACIT-Sp: Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy—Spiritual Well-Being Scale

Breast cancer participants had a 9.2 ± 14.3 point improvement (11.1% increase, effect size = 0.64) on FACIT-Sp scores at month 1 and a 6.7 ± 21.3 point improvement (13.2% increase, effect size = 0.30) at month 6, compared with baseline, when unadjusted for other covariates (P = .0015 and P = .2727, respectively; Table 3). Our final mixed regression models for breast cancer participants showed significant improvements [estimated difference in score between month 1 and baseline = 14.2 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 6.9-21.5; P = .0008) and between month 6 and baseline = 8.4 (95% CI: 1.0-15.9; P = .0287; Table 3].

Furthermore, results from the mixed-effects model regression analyses showed that all QOL measures for all cancer participants were significantly higher at month 1 compared with baseline, except for physical well-being score (P = .53 for physical well-being score, and P < .05 for all other measures; Table 4). Similar findings were observed at month 6 (P = .32 for physical well-being score, and P < .05 for all other measures). The percentage increase in QOL scores ranged from 2.5% (for physical well-being) to 36% (for Faith score) at month 6 compared with baseline. Additionally, emotional well-being score increased by 21.4% (<0.0001) at month 6 compared with baseline.

The living situation was significantly associated with the emotional well-being score: participants living with a partner, family member, or pet had an average change in FACIT-Sp score of 1.5 points higher than those living alone (P = .0087).

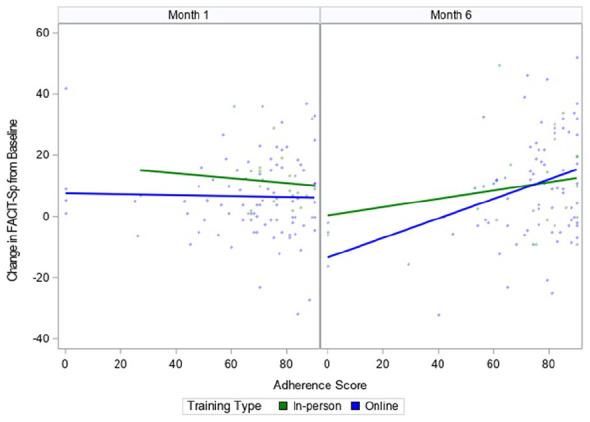

Figure 3 illustrates the relationship between the change in FACIT-Sp scores from baseline and adherence scores at both month 1 and month 6.

Figure 3.

The relationship between adherence scores and changes from baseline (pre-intervention) in FACIT-Sp* scores, at month 1 and month 6 (post-intervention), by training type.

*FACIT-Sp: Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy—Spiritual Well-Being Scale

At month 1, adherence score did not appear to be associated with the change in FACIT-Sp scores for both training types (i.e., in-person and online). However, by month 6, participants with higher adherence scores had a greater change in FACIT-Sp scores (P = .0002 for the main effect of adherence score; and P = .0003 for the interaction term between adherence score and timepoint). These effects were consistent across training types.

Supplemental Table 4 shows the results from models that also included age, ethnic group and BMI as covariates. These 3 covariates were not associated with changes of any QOL scores.

Discussion

This study found that the RRMI workshops were successful in improving the QOL of adult participants with cancer. The primary QOL outcome scores increased significantly from baseline by 7.7% at month 1 and remained significant at month 6 with an increase from baseline of 10.8%. The QOL sub-domain measures of social and family well-being, emotional well-being, and functional well-being all showed significant improvements, while the physical well-being measure did not. Additionally, the sub-measures of meaning, peace, and faith were all significantly higher at month1 and month 6, compared with baseline. Changes in QOL over time were independent of gender, ethnicity, BMI, and age

At month 1, the effect size of the difference is medium for all cancer participants (0.53) and for breast cancer participants (0.64). Our initial sample size estimation was to detect an effect size of 0.44 points in the change of FACIT-Sp scores between baseline and 6 months. The observed effect size for all cancer participants at month 6 is 0.48, slightly larger than 0.44. However, for breast cancer participants, we did not have a large enough sample size, and the effect size is small (0.31), which can be noted as a limitation.

Findings from this study suggest that a safe, low-cost, and relatively easy to implement intervention such as the RRMI has the potential to significantly improve the QOL of individuals with cancer. Higher QOL is associated with improved well-being and cancer prognoses, including decreased side effects,21,22 decreased morbidity, 23 and increased lifespan. 23 Cancer survivors generally report having more comorbid conditions, higher physical symptom burden, especially fatigue, insomnia and pain, compared with the general population. 39

In addition, individuals with cancer often experience higher levels of psychological distress.11,40,41 Negative emotions experienced by them include fear (e.g., of dying and recurrence), trauma, anxiety, grief, worry, hopelessness/helplessness, and a loss of peace.24,40,42 -45 Such conditions of stress have been shown to weaken the immune system’s response to cancer in various studies. 41 In general, these conditions of stress are detrimental to the conditions that need to prevail for cancer patients to heal. Stressful life events, including increased financial burdens, 15 and their related emotional responses, are most likely to result in detrimental long-term or permanent changes in several factors, including emotional well-being (e.g., increased anxiety and depression symptoms)44,46; physiological well-being (e.g., hormonal imbalances, digestive issues, and continued immune suppression; decreased apoptosis, decreased enzymes that degrade chemical carcinogens, and reduced ability to repair cellular DNA).45,47,48 Changes in behavior (e.g., greater alcohol and tobacco consumption, lower physical activity levels as well as poorer dietary and sleep quality) are also observed in cancer patients.46,49,50 The RRMI raises participants’ awareness to the role of stress in impeding disease recovery. It provides ways in which cancer patients can recognize, accept and manage their stress, so healing or disease recovery can occur.10,28

The RRMI significantly increased cancer participants’ emotional well-being at month 6 compared with baseline. This finding suggests that the information and tools provided by the RRMI and introduced to cancer participants with the aim of helping to improve emotional well-being (Table 1) are likely to have a positive impact. In addition to increased emotional well-being associated with the RRMI, our current findings indicate that not living alone (including living with pets), is associated with higher emotional well-being as compared with living alone. Furthermore, the significant increase in social and family well-being at month 6 compared with baseline also appears to reflect a positive influence of the RRMI’s approach in helping all cancer participants recognize the importance of social support (Table 1). Companionship and social support are critical contributors to higher emotional and social well-being. After cancer diagnosis, larger social networks and greater social support/integration have been related to higher QOL, 51 while socially isolated individuals experience increased risk of all-cause and cancer mortality. 52

Meaning, peace, and faith scores were also significantly increased at month 6 compared with baseline. The tools provided by the RRMI in these areas (Table 1) also appear to improve the meaning, peace and faith scores. This is of particular importance, given that a cancer diagnosis may threaten people’s sense of meaning in life and affect their life purpose and priorities. 53 Regaining or discovering their meaning in life, and accepting their disease, have been shown to improve individuals’ cancer coping strategies and psychological well-being. 54 Sense of peace is also strongly associated with mental health. 55 Increased sense of peace, that is, reduced stress, also triggers healing. 56

There is substantial evidence that links greater spiritual well-being with better health outcomes, and ability to cope with illness, including terminal illness.23,37 Low spiritual well-being in people with cancer has been associated with worse physical and mental health, among other dysfunctions.37,57 High spiritual well-being is positively correlated with fighting spirit and negatively correlated with feelings of helplessness/hopelessness. 37 Given that the RRMI showed significant increases in FACIT-Sp and FACIT-Sp-12 scores at month 6 compared with baseline, it is likely that RRMI participants find hope, along with a reawakening of their fighting spirit, to commit to living. These attributes have been reported to improve QOL, and extend the lifespan of cancer patients.58 -60

A cancer diagnosis can make it difficult for individuals to feel that they have control over their lives.61,62 The RRMI empowers people to be active in taking responsibility for all aspects of their lives, and to include their intuition in their decision-making processes (Table 1). These are key RRMI lifestyle factors, and are likely contributing factors toward the increased QOL observed in this study.

The use of herbs and nutritional supplements is also a RRMI lifestyle factor. Turner and White identified 3 main categories of supplements that RR survivors reported they took: immune-boosting, detoxifying, and those improving digestion and absorption of nutrients. 28 Herbal and nutritional supplements are widely used among cancer patients.62,63 RRMI participants are advised to take supplements only under the guidance of trained licensed health professionals. Additionally, RR survivors consistently reported increased intake of organic vegetables and fruits, and reduced intake of processed meats, red meat, and added sugars. 28 Making such dietary changes is also an important RRMI lifestyle factor. These dietary patterns are recommended by the American Cancer Society, the World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research, and the American College of Lifestyle Medicine.64,65 A predominantly plant-based dietary pattern is high in fiber, dense in essential nutrients, rich in bioactive compounds66,67 with various anti-cancer properties, 68 and has been shown to improve QOL. 69 Further, organically grown foods have also been reported to have higher concentrations of antioxidants and lower incidence of pesticide residues than conventionally grown foods. 70 The RRMI also emphasized the importance of working with licensed practitioners to identify foods that may trigger adverse reactions due to food sensitivities or intolerances.28,71

A significant greater change in FACT-Sp scores was observed with increased adherence scores at month 6, compared with month 1 (Figure 3). This suggests that a greater improvement on participants’ QOL is observed when the information and tools provided in all the RRMI modules (Table 1) were more actively practiced for at least 6 months. Disease recovery takes time. The consistent implementation of the RRMI key lifestyle factors (daily, and/or on a regular basis) over time is likely to start transforming a person’s mindset to promote mental, spiritual and overall health. These outcomes have been reported by RR survivors 72 who were highly committed to making these lifestyle changes.10,28,72

Current findings suggest that the RRMI may play an important role in improving QOL. Its incorporation as part of routine cancer care has the potential to safely complement standard oncological treatment, supporting improved health outcomes, increasing survival time, and reducing health care costs. 73 Contrary to expectations, our findings show no significant difference in outcomes when the RRMI workshops were attended online or in-person. Therefore, individuals with a broadband internet connection can potentially reap benefits even if their health or social circumstances limit their ability to attend in-person sessions. This means that the RRMI has the potential to influence cancer care across distances, at relatively low cost, giving hope and support to people newly diagnosed with cancer, as well as those living with cancer chronically and cancer survivors.

This study has limitations due to the use of a convenience sample that was not randomized into intervention and control groups, combining cancer types, lack of control for disease stage and progression, and does not provide long-term evaluation of the effects. Participants who chose not to participate for any reason, such as the cost of the intervention, lack of time or support from family members, and poor health, are not represented in this study. Hence, findings on the impact of the intervention on our outcome measures of interest cannot be attributed solely to the intervention, and thus cannot be considered conclusive. Additionally, they cannot be generalized to all cancer populations. However, the lifestyle factors identified are known to prevent, slow, halt, and reverse multiple chronic diseases such as diabetes, and cardiovascular disease,65,74 -80 including cancer,4,78,81,82 promoting disease recovery. Hence, they are likely to be generally beneficial in most disease states. Despite these limitations, this study provides valuable preliminary information on the impact of the RRMI on participants’ QOL, and data obtained serves as an important foundation for further research. This study’s findings are critical for the development of an intervention that can be tested in a fully powered randomized clinical trial that is able to control for cancer type and stage.

Conclusion

The pre-post RRMI study was found to improve the overall QOL of cancer participants at month 1 post-intervention. This improvement in QOL was maintained at month 6 post-intervention. Given improved QOL contributes to enhanced health outcomes and overall well-being, including decreased treatment side effects and increased survival time, our findings suggest that individuals with cancer can benefit from the RRMI.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-ict-10.1177_15347354241293197 for Effect of the Radical Remission Multimodal Intervention on Quality of Life of People with Cancer by Junaidah B. Barnett, George C. Wang, Wu Zeng, Ruth W. Kimokoti, Teresa T. Fung, Yuan H. Chen, Jerry Kantor, Wei Wang and Michelle D. Holmes in Integrative Cancer Therapies

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to recognize the following for their significant contributions to this important work:

All participants, who volunteered to participate in this study, in hope of helping others with cancer to better navigate their cancer recovery journey

Dr. Kelly Turner and her staff, (the late) Ms. Tara Flanagan Koening, Ms. Sarah Weldy, and Ms. Jess Hershey, Radical Remission Foundation, for assistance with study recruitment and follow-up of participants

Radical Remission health coaches for their role in conducting the RRMI, and recruiting study participants

Dr. Kelly Turner for providing Table 1, and review of manuscript to ensure all information provided regarding the RRMI are correct

Mr. Madhav Bidhe, Aumtech, Inc, for providing use of HARIS for the study, and it’s management by his staff without charge. Mr. Murali Sounderarjan, Aumtech, Inc, for adapting HARIS for this study, and helping manage online study data collection

Ms. Yueming Liu, Department of Statistics, Northwestern University, for her data analysis of the QOL data under the supervision of Dr. Wu Zeng

Dr. Maryam S. Farvid, Nutrition and Food Studies, George Mason University, for her review of the manuscript and critical input

All study team members who volunteered their time and expertise to ensure the high quality of this work

Footnotes

Author Contributions: JBB, GCW, MDH, WW, and WZ were responsible for conceptualizing and designing the evaluation component of the study. JBB oversaw and guided data collection, with inputs from other authors. RWK assisted with participant follow-up and data collection. WW, WZ and YHC conducted data cleaning, preliminary and final analyses, with input from all authors. JBB drafted the manuscript. All authors (JBB, GCW, WZ, RWK, TTF, JK, YHC, WW, and MDH) were responsible for the interpretation of data, critical review of the manuscript, and approval of the final manuscript for submission.

Data Availability Statement: The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was conducted through the voluntary contribution of all authors. Funding for data cleaning, preliminary and final data analyses was provided to WW and YC by the Radical Remission Foundation. Funding for publication of this article was also provided by the Radical Remission Foundation. Other contributions by the Radical Remission Foundation to this work are described in the ACKNOWLEDGMENTS section.

Ethics Statement: The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

ORCID iDs: Junaidah B. Barnett  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6034-2529

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6034-2529

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Huang YC, Kung PT, Ho SY, et al. Effect of multidisciplinary team care on survival of oesophageal cancer patients: a retrospective nationwide cohort study. Sci Rep. 2021;11:13243. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-92618-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hong NJ, Wright FC, Gagliardi AR, Paszat LF. Examining the potential relationship between multidisciplinary cancer care and patient survival: an international literature review. J Surg Oncol. 2010;102:125-134. doi: 10.1002/jso.21589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sharman R, Harris Z, Ernst B, et al. Lifestyle factors and cancer: a narrative review. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2024;8:166-183. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2024.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ornish D, Weidner G, Fair WR, et al. Intensive lifestyle changes may affect the progression of prostate cancer. J Urol. 2005;174:1065-1069. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000169487.49018.73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Saxe GA, Hébert JR, Carmody JF, et al. Can diet in conjunction with stress reduction affect the rate of increase in prostate specific antigen after biochemical recurrence of prostate cancer? J Urol. 2001;166:2202-2207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Saxe GA, Major JM, Nguyen JY, et al. Potential attenuation of disease progression in recurrent prostate cancer with plant-based diet and stress reduction. Integr Cancer Ther. 2006;5:206-213. doi: 10.1177/1534735406292042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Turner K. Spontaneous Remission of Cancer: Theories from Healers, Physicians, and Cancer Survivors. Doctoral dissertation. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses; (Accession Order No AAT 3444696). [Google Scholar]

- 8. Turner K. Spontaneous/radical remission of cancer: transpersonal results from a grounded theory study. Int J Transpers Stud. 2014;33:42-56. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cole WH, Everson TC. Spontaneous regression of cancer: preliminary report. Ann Surg. 1956;144:366-383. doi: 10.1097/00000658-195609000-00007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Turner K. Radical Remission: Surviving Cancer Against All Odds. HarperOne; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Turner K. The “Spontaneous” remission of cancer: theories from doctors, healers, and cancer survivors. Paper presentation at the American Public Health Association’s 138th Annual Scientific Meeting Denver, CO, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Salman T. Spontaneous tumor regression. J Oncol Sci. 2016;2:1-4. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Heidrich SM, Brown RL, Egan JJ, et al. An individualized representational intervention to improve symptom management (IRIS) in older breast cancer survivors: three pilot studies. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2009;36:E133-E143. doi: 10.1188/09.ONF.E133-E143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Maughan TS, James RD, Kerr DJ, et al. British MRC Colorectal Cancer Working Party. Comparison of survival, palliation, and quality of life with three chemotherapy regimens in metastatic colorectal cancer: a multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1555-1563. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)08514-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nayak M, George A, Vidyasagar M, et al. Quality of life among cancer patients. Indian J Palliat Care. 2017;23:445-450. doi: 10.4103/IJPC.IJPC_82_17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jalili S, Ghasemi Shayan R. A Comprehensive evaluation of health-related life quality assessment through head and neck, prostate, breast, lung, and skin cancer in adults. Front Public Health. 2022;10:789456. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.789456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Faria M, Teixeira M, Pinto MJ, Sargento P. Efficacy of acupuncture on cancer pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Integr Med. 2024;22:235-244. doi: 10.1016/j.joim.2024.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Deng G. Integrative Medicine Therapies for pain management in cancer patients. Cancer. 2019;25:343-348. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0000000000000399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Woodbury A, Myles B. Integrative therapies in cancer pain. Cancer Treat Res. 2021;182:281-302. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-81526-4_18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Maindet C, Burnod A, Minello C, et al. Strategies of complementary and integrative therapies in cancer-related pain-attaining exhaustive cancer pain management. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27:3119-3132. doi: 10.1007/s00520-019-04829-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wedding U, Pientka L, Höffken K. Quality-of-life in elderly patients with cancer: a short review. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43:2203-2210. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nolazco JI, Chang SL. The role of health-related quality of life in improving cancer outcomes. J Clin Transl Res. 2023;9:110-114. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mueller PS, Plevak DJ, Rummans TA. Religious involvement, spirituality, and medicine: implications for clinical practice. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76:1225-1235. doi: 10.4065/76.12.1225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Namisango E, Luyirika EBK, Matovu L, Berger A. The meaning of healing to adult patients with advanced cancer. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20:1474. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20021474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mondschein C, Monda C. The EU's General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in a research context. In: Kubben P, Dumontier M, A Dekker. (eds) Fundamentals of Clinical Data Science. Springer; 2019:55-71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Peterman AH, Fitchett G, Brady MJ, Hernandez L, Cella D. Measuring spiritual well-being in people with cancer: the functional assessment of chronic illness therapy–Spiritual well-being scale (FACIT-Sp). Ann Behav Med. 2002;24:49-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, et al. Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383:1721-1730. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62416-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Turner K, White T, Radical Hope: 10 Key Healing Factors From Exceptional Survivors of Cancer & Other Diseases. Hay House Inc; 2021:368. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cormie P, Trevaskis M, Thornton-Benko E, Zopf EM. Exercise medicine in cancer care. Aust J Gen Pr. 2020;49:169-174. doi: 10.31128/AJGP-08-19-5027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Campbell KL, Winters-Stone KM, Wiskemann J, et al. Exercise guidelines for cancer survivors: consensus statement from international multidisciplinary roundtable. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2019;51:2375-2390. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000002116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. https://www.aumtech.com/ .

- 32. Gu X, Wang DD, Sampson L, et al. Validity and reproducibility of a semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire for measuring intakes of foods and food groups. Am J Epidemiol. 2024;193:170-179. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwad170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Webster K, Cella D, Yost K. The Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT) measurement system: properties, applications, and interpretation. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:79. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-1-79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Munoz AR, Salsman JM, Stein KD, Cella D. Reference values of the functional assessment of chronic illness Therapy-Spiritual Well-Being: a report from the American Cancer Society's studies of cancer survivors. Cancer. 2015;121:1838-1844. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. https://www.facit.org/measures/FACIT-Sp-12 .

- 36. https://www.facit.org/scoring .

- 37. Bredle JM, Salsman JM, Debb SM, Arnold BJ, Cella D. Spiritual well-being as a component of health-related quality of life: the functional assessment of chronic illness therapy—spiritual well-being scale (FACIT-Sp). Religions. 2011;2:77-94. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Laxy M, Teuner C, Holle R, Kurz C. The association between BMI and health-related quality of life in the US population: sex, age and ethnicity matters. Int J Obes (Lond). 2018;42:318-326. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2017.252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Götze H, Taubenheim S, Dietz A, Lordick F, Mehnert A. Comorbid conditions and health-related quality of life in long-term cancer survivors-associations with demographic and medical characteristics. J Cancer Surviv. 2018;12:712-720. doi: 10.1007/s11764-018-0708-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mayer M. Lessons learned from the metastatic breast cancer community. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2010;26:195-202. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2010.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zhang L, Pan J, Chen W, Jiang J, Huang J. Chronic stress-induced immune dysregulation in cancer: implications for initiation, progression, metastasis, and treatment. Am J Cancer Res. 2020;10:1294-1307. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Palesh O, Butler LD, Koopman C, et al. Stress history and breast cancer recurrence. J Psychosom Res. 2007;63:233-239. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.05.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Iwata M, Ota KT, Duman RS. The inflammasome: pathways linking psychological stress, depression, and systemic illnesses. Brain Behav Immun. 2013;31:105-114. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2012.12.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Cohen S, Janicki-Deverts D, Miller GE. Psychological stress and disease. JAMA. 2007;298:1685-1687. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.14.1685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Heffner KL, Loving TJ, Robles TF, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Examining psychosocial factors related to cancer incidence and progression: in search of the silver lining. Brain Behav Immun. 2003;17 (Suppl 1):S109-S111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. McEwen BS. Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators. New Engl J Med. 1998;338:171-179. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199801153380307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tsigos C, Kyrou I, Kassi E, Chrousos GP. Stress: endocrine physiology and pathophysiology. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Blackman MR. et al. (eds) Endotext. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Esterling BA, Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Bodnar JC, Glaser R. Chronic stress, social support, and persistent alterations in the natural killer cell response to cytokines in older adults. Health Psychol. 1994;13:291-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Antoni MH, Lutgendorf SK, Cole SW, et al. The influence of bio-behavioural factors on tumour biology: pathways and mechanisms. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:240-248. doi: 10.1038/nrc1820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lehrer S, Green S, Ramanathan L, Rosenzweig KE. Insufficient sleep associated with increased breast cancer mortality. Sleep Med. 2013;14:469. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2012.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Michael YL, Berkman LF, Colditz GA, Holmes MD, Kawachi I. Social networks and health-related quality of life in breast cancer survivors: a prospective study. J Psychosom Res. 2002;52:285-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kroenke CH, Kubzansky LD, Schernhammer ES, Holmes MD, Kawachi I. Social networks, social support, and survival after breast cancer diagnosis. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1105-1111. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.2846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Quinto RM, De Vincenzo F, Campitiello L, et al. Meaning in life and the acceptance of cancer: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:5547. doi:)10.3390/ijerph19095547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Roepke AM, Jayawickreme E, Riffle OM. Meaning and health: a systematic review. Appl Res Qual Life. 2014;9:1055-1079. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Madhumita. Psychological perspectives of mental health and inner peace. J Emerg Technol Innov Res. 2020;7:788-792. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Hannibal KE, Bishop MD. Chronic stress, cortisol dysfunction, and pain: a psychoneuroendocrine rationale for stress management in pain rehabilitation. Phys Ther. 2014;94:1816-1825. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20130597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Edmondson D, Park CL, Blank TO, Fenster JR, Mills MA. Deconstructing spiritual well-being: existential well-being and HRQOL in cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2008;17:161-169. doi: 10.1002/pon.1197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Roud PC. Psychosocial variables associated with the exceptional survival of patients with advanced malignant disease. J Natl Med Assoc. 1987;79:97-102. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Chida Y, Steptoe A. Positive psychological well-being and mortality: a quantitative review of prospective observational studies. Psychosom Med. 2008;70:741-756. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31818105ba [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Corn BW, Feldman DB, Wexler I. The science of hope. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:e452-e459. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30210-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]