Abstract

Background

Refugees escaping political unrest and war are an especially vulnerable group. Arrival in high-income countries (HICs) is associated with a ‘new type of war’, as war refugees experience elevated rates of psycho-social and daily stressors.

Purpose

The purpose of this scoping review is to examine literature on psycho-social stressors amongst young war refugees in HICs and impact of stressors on intergenerational transmission of trauma within parent-child dyads. The secondary objectives are to identify the pre-migration versus post-migration stressors and provide a basis to inform future research projects that aim to lessen the burden of stress and inform evidence-based improvements in this population.

Methods

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Scoping Review Extension (PRISMA-ScR) guided the reporting of this review that was performed using a prescribed scoping review method. Extracted from five databases, 23 manuscripts published in 2010 or later met the inclusion criteria.

Results

Three themes emerged: pre-migration stressors, migration journey stressors and uncertainty, and post-migration stressors. While post-migration environments can mitigate the health and well-being of war refugees, socio-cultural barriers that refugees often experience at the host country prevent or worsen their psycho-social recovery.

Conclusion

To assist the success of war refugees in HICs, therapeutic interventions must follow an intersectional approach and there needs to be a wider application of trauma informed models of care. Findings of this review may help inform future intervention studies aiming to improve the psycho-social health of this population.

Keywords: Adolescents, immigrants, international health, mental health, children and young people

Introduction

According to projections by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), “117.2 million people will be forcibly displaced or stateless in 2023” (Global Appeal, 2023, para. 4), including over 33 million refugees. UNCHR defines refugees as “people who have fled war, violence, conflict or persecution and have crossed an international border to find safety in another country” (Refugees, n.d.-b, p. 1). Particularly, Russia's invasion of Ukraine has triggered an unprecedented rise in the number of global refugees ( Global Appeal, 2023 ). While Russia's invasion of Ukraine is an acutely relevant issue (Basic, 2022), the urgency to escape armed conflict is not a unique phenomenon. Notable refugee crises caused by civil and political unrest and war have been and continue to be witnessed throughout the twenty-first century in countries such as Syria, Afghanistan, Venezuela, South Sudan, and Myanmar (7 of the World's, n.d.). Groups escaping such conflict are an especially vulnerable population, as they disproportionately experience psycho-social pathologies such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety and mood disorders while facing challenges to their personal identity and sense of belonging (Hodes & Vostanis, 2018).

Few war refugees have the opportunity for relocation to developed countries such as Canada and the United States (Betancourt et al., 2015; Global Trends - Forced Displacement in 2018 - UNHCR, n.d.). The World Bank designated 81 countries as ‘high-income’ economies in 2023 as defined by a Gross National Income (GNI) per capita of $13,205 USD or greater (World Bank, n.d.). These developed countries host approximately 26% of the world's refugees (Refugees, 2023).

Despite well developed social systems and high population quality of life in developed countries (Standard of Living, 2023), refugees to these countries often face a “new type of war” maneuvering barriers such as inadequate access to healthcare, psycho-social trauma, separation from family and difficulty adjusting to their new life (Betancourt et al., 2015). They often arrive with little more than they can carry, and leave behind family and friends (Refugees, n.d.-b). The “immigrant paradox” even suggests that more acculturated youth who have spent greater amounts of time in the destination country experience increased mental distress when compared to less acculturated new-coming refugee youth (Patel et al., 2017). This paradox implies high levels of cumulative psycho-social stressors in the destination country. Thus, it is imperative to identify and understand the nature of the psycho-social stressors so that they may be addressed in future research aiming to improve the mental health and well-being of war refugees in developed countries.

Approximately 40% of the global refugee population comprises children and teenagers under 18 (Refugees, 2023). For young war refugees, the quality of their relationship with caregivers, often their parents, becomes paramount as they navigate the challenges of displacement, trauma, and resettlement while contending with the general difficulties of this developmental period (Basic, 2022; Kanji & Cameron, 2010). Parents who experience post-traumatic stress symptoms may exhibit insensitive caregiving, hostile-intrusive behaviour, or emotional numbing, which can hinder their ability to effectively support their children's well-being (Betancourt et al., 2015; Flanagan et al., 2020). Maternal post-traumatic stress has been associated with adverse psychosocial outcomes in children, highlighting the importance of exploring the parent-child interaction as a potential risk factor for worsening health outcomes among young war refugees in developed countries (van Ee et al., 2012).

Objectives

Recent literature reviews in this topic area include a practitioner review describing mental health problems in refugees (Hodes & Vostanis, 2018), a systematic review and meta-analysis describing the level of anxiety, PTSD, and depression among refugees in developed countries, (Henkelmann et al., 2020), and a systematic review examining the socio-ecological triggers and protective factors of refugee health (Scharpf et al., 2021). However, a literature review gap continues to exist in outlining the main themes of psycho-social stressors as experienced by war refugees in developed countries and elucidating the intergenerational transmission of trauma through parent-child interactions. This scoping review intends to fill this gap by providing answers to the following primary questions: a) What are the psycho-social stressors amongst war refugees in developed countries, and b) What is the impact of psycho-social stressors amongst war refugees in developed countries on the intergenerational transmission of trauma within the parent-child dyad? The secondary objectives of this review include the identification of pre-migration versus post-migration stressors, understanding the intergenerational transmission of psycho-social distress and trauma, and inform future intervention research projects that aim to lessen the burden of stress and improve psycho-social health in this population.

Methods

Arksey and O’Malley's (2005) scoping review method with the refinement suggested by Levac et al. (2010) coupled with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Scoping Review Extension (PRISMA-ScR) guided the conduct and presentation of the scoping review. Arksey and O’Malley's (2005) scoping review method has five stages: 1) identifying the research question, 2) identifying relevant studies, 3) study selection, 4) charting the data, 5) and collating, summarizing, and reporting the results (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005). In stage one, we identified that search questions as stated in the objectives section above. In Stage two, five electronic databases were searched using a systematic search strategy.

Eligibility criteria

Peer-reviewed papers were deemed eligible if they: a) included content on the experiences of young war-driven refugees in developed countries as designated by the World Bank (World Bank Country, n.d.); b) were written in the English language; c) were published in 2010 or later; and d) Included participants within the age range of 0 to 25 years. This range was chosen to capture the comprehensive experiences of infants, children, adolescents, and young adults affected by war and displacement. . The decision to include papers as far back as 2010 was to capture the exponential rise in war refugees during this decade, driven primarily by the Syrian civil war of 2011. Papers were excluded if they were biological in nature, examined drug treatments of stress, studied war refugees settling exclusively in middle or low-income countries, did not include participants within the age range of 0 to 25 years or were non-peer-reviewed.

Information sources

Databases used in our search were PubMed, Scopus, Sociological abstracts, Nursing & Allied Health and Psycnet. The search terms used in this review were: refugee/refugees, adolescent, minor, parent, child, youth, developed country/ies, western, global north, risk factor, mental health, mental illness, psycho-social/psychological and social, and stressors.

Search

An example of a full electronic search strategy is as follows: (((refugee[Title/Abstract]) AND (adolescent[Title/Abstract] OR minor[Title/Abstract] OR parent[Title/Abstract] OR child[Title/Abstract] OR youth[Title/Abstract])) AND (“high-income” OR western OR “global north” OR developed)) AND (“risk factor*"[Title/Abstract] OR “mental health” OR “mental illness"[Title/Abstract] OR psycho-social[Title/Abstract] OR psycholog*[Title/Abstract] OR social[Title/Abstract]) AND (“stressor” [Title/Abstract] limiting to papers published 2010 or later.

Selection of manuscripts of evidence

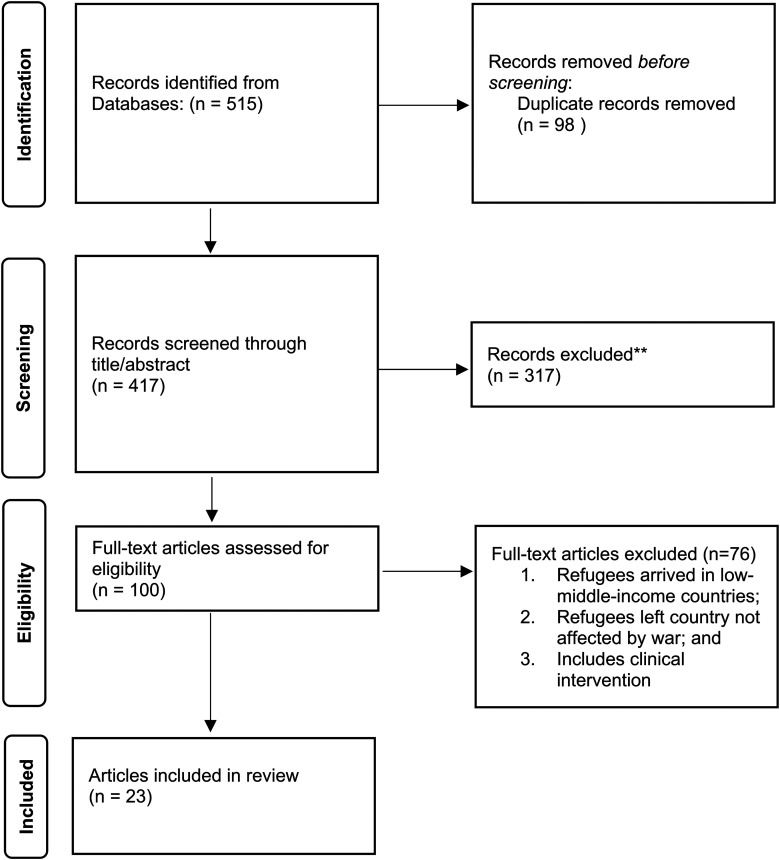

In stage 3, a total of 515 manuscripts were retrieved; of which 417 manuscripts were retained after removing 98 duplicates. The abstracts of these manuscripts were independently screened by two members of our team in round 1 against the inclusion criteria, a process that led to the retention of 100 manuscripts after eliminating 317 manuscripts that were deemed to be irrelevant to our review. In round 2, full text of the remaining 100 manuscripts were reviewed for fit by two members of our team, resulting in the retention of 23 manuscripts after excluding 76 full-text manuscripts that did not meet the eligibility criteria. The reference lists of the 23 retained manuscripts were reviewed to check for titles that could be relevant for this review, but additional manuscripts relevant to this scoping review were found. Finally, the remaining manuscripts were verified by a third member of our team to ensure relevance in manuscript selection (See Fig 1. PRISMA flow chart).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart.

Data charting process

In stage 4, data from the retained 23 manuscripts were charted using citation of manuscript, manuscript type (i.e., systematic review, qualitative, quantitative, mixed methods, cross-sectional, survey, interview, practitioner review, government report, letter to the editor, focus group), and key contributions made to this review (i.e., how they furthered the understanding of psycho-social stressors experienced by the war refugees in developed countries). In stage 5, all manuscripts were grouped under three general themes: 1) pre-migration stressors, 2) migration journey stressors and uncertainty, and 3) post-migration stressors.

Data items

Data were abstracted on manuscript characteristics, including the reason for leaving the country of origin (i.e., war and/or violence), destination country income level (developed versus developing), and psycho-social approach (stressors as opposed to sources of resilience). In some cases, review manuscripts included studies with both developed and developing destination countries or refugees from war and non-war origin countries. Such manuscripts were not excluded, but care was taken to extract evidence from these manuscripts that was specific to the characteristics relevant to this review's objectives (e.g., developed countries, war refugees).

Synthesis of results

Retained manuscripts were first read to identify common themes. Once it was evident that there were three distinct periods of psycho-social stressors (pre-migration, migration journey, post-migration), sub-themes were generated and placed under each of these main themes. Next, each manuscript was read, and evidence was extracted and included under the relevant sub-theme for ease of analysis. This scoping review comprises 23 manuscripts, 17 of which are research studies and six are review papers. For a comprehensive narrative summary of the included manuscripts see Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Key contributions from manuscripts included in this review.

| Citation (First author, year) | Manuscript Type | Key Contributions to Review from Manuscript |

|---|---|---|

| Betancourt, 2015a | Focus groups qualitative analysis | Identifies risk factors amongst Somali refugees in Boston |

| Patel et al., 2017 | Quantitative self-report data | Links war-related events and acculturative stressors in HIC to conduct problems and low GPA |

| Hodes & Vostanis, 2018 | Practitioner review | Identifies migration journey difficulties |

| Henkelmann et al., 2020 | Systematic review with meta-analyses and meta-regression. | Reports prevalence rates of anxiety, depression, PTSD, and anxiety for refugees in HICs |

| Scharpf et al., 2021 | Systematic review | Mental health contributing factors across socio-ecological levels and stages of refugee experience |

| Dangmann et al., 2021 | Cross-sectional, questionnaire-based quantitative | Evidence of post-migration stressors mediating relationship between traumatic events and health-related quality of life |

| George & Jettner, 2016a | Two-group, cross-sectional design | Pre-migration trauma shows strongest influence on psychological distress as compared to daily post-migration stressors |

| Bogic, 2012a | Quantitative multicentre survey | Association between mental health disorders and pre-and-post migration stressors amongst long-settled war refugees |

| Rossiter et al., 2015 | Qualitative: Semi-structured interviews | Highlights systemic barriers towards Canadian integration |

| Basic, 2022 | Qualitative interviews | Reveals the nature of power dynamics amongst unaccompanied refugees through personal narratives |

| Thommessen et al., 2015 | Qualitative: Interpretative phenomenological analysis | Identifies risks and protective factors of unaccompanied asylum-seeking youth through lived-experience narratives |

| Drummond Johansen & Varvin, 2020 | Qualitative exploration | Shows the intersection between familial war experiences and impaired identity development |

| Javanbakht et al., 2021 | Mixed methods, qualitative and quantitative (grant report) | Reports on correlation between maternal and paternal stress and childhood mental health outcomes for Syrian refugees |

| Flanagan et al., 2020 | Systematic review | Describes correlation and mechanisms between parental trauma exposure and child well-being |

| Atrooz et al., 2022 | Quantitative survey | Analyzes the gender-specific state of well-being in Texan-settled Syrian refugees |

| Kartal et al., 2019 | Quantitative | Examines the relationship between host-language acquisition and mental health outcomes |

| Kanji & Cameron, 2010 | Qualitative: Hermeneutic photography/photo conversation data collection and analysis | Identifies themes describing daily life experiences of Muslim Afghan refugee children settled in Canada |

| Hoffman, 2020 | Mixed methods, qualitative and quantitative | Relationship between maternal torture exposure and youth mental health |

| Javanbakht, 2018 | Letter to the editor: Cross sectional quantitative | Shows elevated initial rates of anxiety and PTSD symptoms upon resettlement to the United States |

| Van Ee et al., 2012 | Qualitative | Shows effects of maternal PTSD symptoms on infant & child psycho-social problems |

| Fegert et al., 2018 | Review: German government advisory council abridged report | Develops recommendations on addressing needs of refugee families exposed to traumatic events |

| MacMillan et al., 2015 | Qualitative descriptive study | Examines rates of play in refugee children pre-and-post migration |

Table 2.

Narrative summary describing study characteristics for included manuscripts.

Discussion

Our review suggests that psycho-social stressors can be classified into three main categories: pre-migration, migration journey and post-migration stressors. Although these categories act in unison and are deeply interrelated, the unique stressors found in these three main periods differentially predispose refugees to mental health distress and disorders. While pre-migration and migration journey stressors will be briefly covered, post-migration stressors are the primary focus of this discussion, as they are indicative of stressors experienced by war refugees to developed countries. In addition, 16 out of the 23 of the manuscripts that we examined on this scoping review had a larger focus on post-migration stressors.

Theme 1: pre-migration stressors

Pre-migration stressors are stressful experiences before flight from a war-torn country (Dangmann et al., 2021). Evidence suggests that pre-migration trauma has a greater influence on psychological distress than daily stressors (George & Jettner, 2016a) (See Table 3). In a sample of 854 war-exposed former Yugoslavian refugees in Germany, Italy and the United Kingdom, pre-migration war factors accounted for greater variance in the rates of PTSD (14.2% of variance compared to 12.8% for post-migration) (Bogic et al., 2012a). The findings also suggested that post-migration stressors increasingly affect rates of anxiety disorders (11% war factors, 11.5% post-migration factors) and mood disorders (12.2% war factors, 16.1% post-migration factors). Further, a dose-response correlation between potentially traumatic experiences (PTE) and the prevalence of anxiety and mood disorders. Particularly, combat experience in this sample was inversely correlated with levels of PTSD and anxiety disorders. Having military training and a newfound purpose in protecting their country and family allows refugees to increasingly cope with PTEs. These findings may be indicative of post-traumatic growth, suggesting that these previous soldiers may utilize their war experiences to provide meaning in the face of adversity (The Graying of Trauma, 2014).

Table 3.

Manuscripts contributing to the three themes.

| Theme #1: Pre-migration stressors | Citation |

|---|---|

| Contributions to theme | |

| Definition of pre-migration stressors | (Dangmann et al., 2021) |

| Potentially greater influence of pre-migration trauma as compared to daily stressors on psychological distress | (George & Jettner, 2016) |

| Pre-migration stressors have greatest effects on PTSD | (Bogic et al., 2012) |

| Narratives of PTSD in Canada | (Rossiter et al., 2015) |

| Level of exposure to war mediates acculturative stresses | (Patel et al., 2017) |

| Theme #2: Migration journey stressors and uncertainty | |

| Correlation between migration journey, migration certainty and mental illness | (Henkelmann et al., 2020) |

| Migrant-related stress is correlated with anxiety and mood disorder in war refugees | (Bogic et al., 2012) |

| Migration journey can take months or years of laborious travel | (Hodes & Vostanis, 2018) |

| Traumatic narratives of migration journey | (Basic, 2022) |

| Longitudinal studies show higher mental illness when rejected asylum | (Scharpf et al., 2021) |

| Increased anxiety as war refugees await results of asylum application | (Thommessen et al., 2015) |

| Theme #3: Post-migration stressors | |

| Importance of host language acquisition | (Atrooz et al., 2022) |

| Host language acquisition inversely correlated with mental illness | (Kartal et al., 2019) |

| Narratives of educational impairments from language barriers | (Kanji & Cameron, 2010) |

| Lack of employment and language skill due to imminent financial need | (Rossiter et al., 2015) |

| Lack of parental host language acquisitions creates sociocultural barriers | (Betancourt et al., 2015) |

| Worries of family members left behind amongst unaccompanied refugees | (Thommessen et al., 2015) |

| Supportive living environments reduces stress levels | (Hodes & Vostanis, 2018) |

| Separation from immediate family increases PTSD symptoms | (Scharpf et al., 2021) |

| Perceived discrimination harms health and wellbeing | (Dangmann et al., 2021) |

| Harmful effects from negative media portrayals of refugees | (Basic, 2022) |

| Ethnocultural minorities express frustration upon not being accepted by society | (Drummond Johansen & Varvin, 2020) |

| Explanation of the immigrant paradox | (Patel et al., 2017) |

| Parent-offspring interactions can increase psychopathology and unhealthy development | (Flanagan et al., 2020) |

| Triad of symptoms experienced by traumatized parents | (van Ee et al., 2012) |

| Inability for traumatized adults to carry out parental responsibilities | (Fegert et al., 2018) |

| Lack of family cohesion can worsen childhood development | (MacMillan et al., 2015) |

In a cross-sectional study of 160 Syrian youth in Norway, Dangmann et al. (2021) identified pre-migration PTEs as the main determinant of mental distress and post-migration stressors. An earlier qualitative study of 14 refugee youth in Canada used semi-structured interviews to help demonstrate the potentially harmful effects of these PTEs (Rossiter et al., 2015). As one youth refugee explained, “When I hear noises, like a loud boom, I react…. Should I run, should I take cover, or you don’t know which direction, ‘cause in the refugee camp people just start running from some direction and you see someone running, [shouting] “They’re shooting, they’re coming” (Rossiter et al., 2015, p. 754). In the same sample, refugee youth confirmed the association between these pre-migration PTEs and increased potential for gang involvement and substance abuse: “It's a coping mechanism…. You know, they want to get high … or get drunk and forget about what's going on at home or . .. school…. They’ve been in refugee camps…. I think once they get back into the real world, they figure out how hard it is for them to start over again and a lot of them … don’t have the strength or the support system to do that.” (Rossiter et al., 2015, p. 754). In a sample of 184 adolescent refugees and immigrant newcomers to the United States (time of residence = 3.5 years on average), greater exposure to war-related events pre-migration was associated with greater self-reported anxiety, conduct issues, and reduced academic achievement as measured by their grade-point average (Patel et al., 2017). Although the post-migration factor of acculturative stressors was a protective factor associated with better outcomes for these students, the relationship between self-reported anxiety and conduct problems was mediated by the level of exposure to war. In other words, the greater one's exposure to war, the less the acculturative stressors could act as a protective factor towards refugee adolescent adjustment in the new country resulting in greater difficulties in the classroom and everyday life.

Theme 2: migration journey stressors and uncertainty

After escaping a war-torn country, refugees continue to experience a variety of stressors and uncertainty along the migration journey (See Table 3). Both stress and uncertainty have consistently been reported to be associated with increased prevalence of mental illness (Henkelmann et al., 2020). The migration journey is a time of severe uncertainty and can also predispose refugees to varying levels of psycho-social stress. Using quantitative face-to-face interviews, Bogic et al. (2012b) demonstrated that more significant migration-related stress is associated with increased rates of anxiety and mood disorders amongst 854 war-affected refugees in Germany, Italy, and the United Kingdom (Bogic et al., 2012b). Some refugees may anticipate war and can pre-plan their exit journeys (Hodes & Vostanis, 2018). If they are financially fortunate enough, they can travel via train or plane and seek asylum through legal means; others are not so fortunate. Many refugees require “people smugglers” and are exposed to prolonged, laborious journeys (Hodes & Vostanis, 2018). In these cases, refugees may be exposed to various dangers, including abuse, assault, theft from their smugglers and exposure to dangerous physical elements such as traversing in freezing weather and through rough seas. The war escape journey can take weeks, months or even years (Hodes & Vostanis, 2018). During this time, migrants can be detained and separated from family and friends.

Qualitative interviews of six young people in Sweden who fled the wars in Iraq, Syria and Afghanistan further elucidate these migration difficulties (Basic, 2022). Filled with traumatizing experiences of separation from families, slave labour, detention and witnessing the death of fellow refugees, these narratives describe experiences akin to the wartime narratives (Basic, 2022). Familial separation was described as an especially traumatic stressor. Their escape from war occurred in various stages, lasting anywhere from 50 days to 13 months. One youth “Emin” considered the migration journey as an extension of the war itself. His 50-day journey out of Afghanistan involved traversing via “Iran, Turkey, the Balkans and Western Europe” to finally arrive in Sweden (Basic, 2022, p.11). Another youth “Enis” described his journey from the Middle East as “one of the most difficult experiences” (Basic, 2022, p.12). He explained, “I saw someone drown and someone else get shot and met people who had no money left. They had no hope of continuing the journey and could neither go on nor go back the way they came./ . . . /I can tell you; we had many sleepless nights” (Basic, 2022, p. 12). “Enis” explains that he couldn’t remember all the countries he had passed through and that at one point, the smugglers instructed him to climb a mountain while carrying an unknown woman, demonstrating the lack of power experienced while putting his life in the hands of human smugglers (Basic, 2022).

After an arduous migration journey, refugees must experience the uncertainties associated with migration and long-lasting asylums, which have been shown to increase the prevalence of mental illness (Henkelmann et al., 2020). As explained in a systematic review of risk factors among refugee children and adolescents, minors who experienced asylum rejection had higher levels of PTSD, depression, and anxiety than those who were granted asylum (Scharpf et al., 2021). In another study, Thommessen et al. (2015) carried out semi-structured interviews with six male refugees from Afghanistan arriving in Sweden as unaccompanied minors and reported that all six refugees expressed concern and anxiety during their initial months in Sweden while awaiting the results of their asylum application. Alone, tired, and traumatized, these difficulties were exacerbated by having to leave their families behind. Bogic et al. (2012a) also reported that temporary residence status is associated with increased rates of anxiety and mood disorders, PTSD and substance use disorders. These findings may reflect the importance of perceived acceptance by the host country, especially when family structure and support are absent.

As refugees arrive in the developed countries, both their status in the country and their sense of identity are put into question, as they are inextricably linked and decided upon by the country of residence. An individual who is an “asylum seeker” in Germany, may be an “irregular arrival” in Canada, or a “migrant worker” in the United Arab Emirates (Hodes & Vostanis, 2018). These labels can bring an increased identity-consciousness and identity stress, as refugees struggle to form a coherent sense of self in the new host country (Drummond Johansen & Varvin, 2020). Refugees may also experience stressful age disputes when adolescents’ claims to be under 18 years old are disbelieved and rejected by immigration authorities (Hodes & Vostanis, 2018). In many of these cases, the refugees would then be considered adults, and are thus denied from receiving the level of support and services they need and deserve (Hodes & Vostanis, 2018). Basic (2022) described the daily conditions of the refugees from Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria who resettled in Sweden as an existence of uncertainty, as they were unaware if they would be allowed to remain in Sweden and whether their parents would eventually join them in the host country. They experienced continuous conflict with the Swedish Migration agency and social services and reported difficulty with contacting their case workers by email or telephone. The experiences of these young refugees represent powerlessness as their identity is put into question by powerful authorities (Basic, 2022).

Theme 3: post-migration stressors

Of the three main identified periods for psycho-social stressors (Pre-migration, migration journey, and post-migration), post-migration stressors were the most extensively researched. Post-migration stressors can be defined as factors following resettlement or arrival in the host country (Dangmann et al., 2021). As explained by Henkelmann et al. (2020), a young refugees’ levels of distress and mental illness can be moderated by post-migration stressors (See Table 3).

Language barriers, host language acquisition

Refugees undergo acculturation when arriving in a new country, a process of cultural and psychological change due to contact with a new culture (Berry, 2005, p. 698). Host language acquisition is essential for adaptation, as language barriers hinder accessing health services, employment, social connections, and integration (Atrooz et al., 2022). Language proficiency is tied to mental health, with better proficiency linked to lower rates of PTSD, depression, and anxiety (Kartal et al., 2019). Among Syrian refugees in Texas, women experienced disproportionately higher mental distress than men, linked to their inability to speak English and subsequent confinement to unpaid home duties (Atrooz et al., 2022). In contrast, the language-adapted “breadwinner” Syrian men faced less social strain. In a Canadian study using “photo conversations” with Afghan refugees, a participant named “Azim” highlighted the challenges of language barriers in education (Kanji & Cameron, 2010). Unlike native English speakers, he struggled with multitasking in English, especially when taking notes and listening simultaneously. Language barriers can lead to educational segregation, discrimination, social exclusion, and poor mental health outcomes (Kartal et al., 2019).

Due to imminent financial stress, many refugees don’t acquire host language skills, limiting employment, socialization, and understanding of legislative changes, risking legal issues (Rossiter et al., 2015). In Australia, language barriers correlate with inaccurate mental health diagnoses and treatment challenges, as care providers struggle to build rapport and understand refugee patients (Kartal et al., 2019). Parental language barriers can also affect children's school experiences and communication between parents and children (Betancourt et al., 2015b). An example of this arose in a study using focus groups of Somali refugee families in Boston. In this instance, when a teacher called home about a student's misbehavior in class, the student intentionally misled his mother about the call's content, as the mother couldn’t understand the teacher due to language barriers. Clearly, learning the dominant language of the host country is a vital aspect of sociocultural adaptation.

Loss and separation

Even after gaining asylum, unaccompanied Swedish-settled refugees continue to worry about family members left behind (Thommessen et al., 2015). Unaccompanied minors’ distress lessens when experiencing less acculturation stress and living in supportive living arrangements (Hodes & Vostanis, 2018). Yet, in Australia, refugee youth separated from their immediate family showed more PTSD symptoms than those living with their immediate family (Scharpf et al., 2021). In a United States detention center, children apart from mothers had more emotional and behavioral problems than children with their mothers (Scharpf et al., 2021). Similarly, in the Netherlands, having even one parent absent led to increased emotional and behavioural problems (Scharpf et al., 2021). Despite these increased rates of behavioural problems being seemingly benign as compared to diagnosable PTSD, they can lead to educational dropouts, affecting future employment prospects in the new country (Scharpf et al., 2021).

Discrimination, stigmatization, and intrusion of identity

Even without concrete evidence of discrimination, perceived discrimination has harms to health and wellbeing (Dangmann et al., 2021). Negative media portrayal of young refugees is a significant stressor which unconsciously extends to many aspects of society (Basic, 2022). Analyzed media reports in Sweden demonstrated two main harmful representations of young refugees who have experienced war: generalizing them as rapists and “benefit fraudsters.” These youth further reported stigmatization through criticism from politicians for political appeal and through negative sentiments from public service officials such as police officers (Basic, 2022). As a young boy war refugee in Sweden described, “Many people in Sweden don’t like us…just read what they write about us on the Internet” (Basic, 2022, p. 17).

Following Al-Qaeda's September 11th, 2001 (9/11) attacks on America and the ensuing Afghan war beginning in October 2001, suspicion towards refugees, especially Muslims, increased (Hodes & Vostanis, 2018). Anti-Muslim bias, intensified by media, can compound the difficulties experienced by newcomers (Betancourt et al., 2015a). During focus groups, Somali youth in Boston reported increased discrimination and harassment post-9/11 (Betancourt et al., 2015a). One Somali mother recounted daily harassment of her daughter due to her wearing a hijab. Such attacks on identity can caused internalized racism and identity struggles. While the Somalian refugee youth tried to assimilate in school, many of their parents feared their children “becoming too Americanized” (Betancourt et al., 2015b, p. 10). There has also been a rise in physical attacks against asylum seekers in Europe (Hodes & Vostanis, 2018).

Despite experiencing discrimination, new refugees experience a longing to fit into their host countries (Thommessen et al., 2015). Afghan refugees in Sweden expressed an understanding that many other young people in a similar situation were not given the same opportunity to be granted asylum, and thus the refugees should take advantage of their opportune circumstances. Still, as ethnocultural minorities, many refugees express frustration that they are never truly accepted by society (Drummond Johansen & Varvin, 2020). In a qualitative study interviewing 16 war refugees exiled to Norway, a participant named Abdul explained his difficulties of feeling perpetually foreign through name-calling and maltreatment (Drummond Johansen & Varvin, 2020). These forms of discrimination can have serious mental health consequences, as they result in being portrayed as the “other” by the dominant cultural group and creates feelings of alienation (Drummond Johansen & Varvin, 2020).

This struggle with identity may form the basis of the “immigrant paradox” – the phenomenon whereby more acculturated youth often experience lower health and well-being compared to those less acculturated (Patel et al., 2017). One proposed explanation for this phenomenon is that residual untreated symptoms from war-associated traumas lead to a greater reliance on inefficient coping strategies such as numbing, suppression or avoidance. This paradox, mainly observed in America and Canada, needs more research. A focus must be placed on how immigration policies and community development can support an increased ability to thrive during the settlement in a new country (Patel et al., 2017).

Economic concerns

Economic concerns were repeatedly found to be harmful to refugees’ health and wellbeing (Dangmann et al., 2021). To acquire and sustain an immediate source of income, many refugees may forego acquiring sufficient employment and native language skills (Rossiter et al., 2015); a practice that limits future opportunities for socialization and integration and hinders future employment opportunities. Structural factors such as the refugee transportation loan repayment can further enforce a short-term financial mindset. The financial stresses are encapsulated in the following case during semi-structured interviews of 14 refugee youth in Canada, “My [older siblings] were working, paying for their [refugee] transportation loan and ours. So that was a bit challenging because they missed out on their education and even on their communication skill” (Rossiter et al., 2015, p.574). Another structural barrier is the lack of acknowledgement of foreign credentials, which leads to underemployment relative to academic qualifications (Rossiter et al., 2015). Lower-income refugee families were especially disadvantaged from the start, with single-parent families disproportionately represented amongst the unemployed/underemployed. Because of low familial income, many newcomers must live in social housing complexes, while some youth experience homelessness. Youth in the subsidized city housing reported being exposed to daily criminal activities, and these neighbourhoods have even been termed “zones of decay” for young refugees (Rossiter et al., 2015, p.756). Despite living in cheaper accommodations, one youth explained that her family could not afford the glasses she needed in the host developed country, as winter clothing and other necessities took priority (Rossiter et al., 2015). In a different study, financial challenges for Somali refugees in Boston were further compounded by an obligation to send money to loved ones back home, while also attempting to support their children with the sparse remaining resources (Betancourt et al., 2015b). One father expressed that their children often couldn’t grasp the financial pressures they faced. He emphasized that regardless of their earnings, the pressing needs of their family back home took precedence.

Parent-child interactions

The myriad of difficulties experienced by youth refugees exposed to PTEs may be further compounded by parent-offspring dyadic interactions, increasing psycho-social pathology and unhealthy development (Flanagan et al., 2020). This parent-offspring interaction can lead to the intergenerational transmission of trauma, otherwise called secondary traumatization, which describes the “impact of traumatic events, experienced by a parent, on child development and wellbeing” (Flanagan et al., 2020, p.2). Studies link parental trauma to children's conduct, peer, and emotional difficulties issues through mechanisms like maladaptive parenting, insecure attachment and ‘parentification’ (Flanagan et al., 2020; Drummond Johansen & Varvin, 2020).

Traumatized parents experience a triad of lingering symptoms such as reexperiencing, avoidance, and hyperarousal (van Ee et al., 2012), often failing in their parental responsibilities, resulting in an unsafe rearing environment (Fegert et al., 2018). In such families, tight living conditions can exacerbate issues like violence against children and neglect. A systematic review identified risk factors affecting second-generation children, including parental trauma exposure, trauma corollary, depression, having both parents exposed to trauma, and severity of symptoms (Flanagan et al., 2020; van Ee et al., 2012). Parental trauma is linked to poor psycho-social outcomes in children, even if they were unexposed to war (Flanagan et al., 2020). Parents, overwhelmed by their children's behavioural and emotional difficulties, may resort to violence (Fegert et al., 2018). This can create a cycle where adolescents and children rebel through aggressiveness, hyperactivity, and refusal to complete household tasks or schoolwork, which worsens parental treatment (Fegert et al., 2018). Ideally, parent-child interactions are characterized by mutual emotional connection (van Ee et al., 2012), but trauma can disrupt this connection, leading to children lacking the capacity for self-regulation. While play and bonding can aid family cohesion and development (MacMillan et al., 2015), many refugee parents, due to their trauma, can’t use these interventions, thus passing their trauma to their children (Betancourt et al., 2015a).

Attachment theory emphasizes the importance of a caring relationship for children's ideal emotional and social development (Cassidy et al., 2013). Ideally, secure attachment forms leading to a lifetime of feeling cared for by others, increased happiness, and positive self-appraisals (Sheinbaum et al., 2015). However, a systematic review looking at mechanisms of intergenerational transmission amongst war refugee families in developed countries suggests that parental trauma disrupts this attachment in children (Flanagan et al., 2020). Non-traumatized children, through repeated early interactions with inconsistent or unresponsive parental figures can develop attachment issues like traumatized refugee children (Sheinbaum et al., 2015). Such insecure attachment has significant negative lifelong implications, manifesting in a constant worry of being separated from or rejected by others, a preference for self-reliance and difficulties with intimacy and closeness with others (Brennan et al., 1998).

Drummond Johansen and Varvin (2020) interviewed 16 young war refugees who grew up in Oslo, Norway. A key observation was ‘parentification’ where children adopted a parental role by providing vital emotional support for their parents and family members. This role-reversal places a burden on the children, hindering their development even in seemingly supportive developed countries like Norway.

Limitations

A limitation of this scoping review is the possibility that some studies were missed as only 5 databases were used, and gray literature (i.e., organizational, and governmental documents and papers, newspaper sources, websites, to name a few) was not searched. As well only manuscripts written English were included where manuscripts in other languages could have further shed light on this topic of interest. Further, the quality of the reviewed studies was not assessed, and no limitations were placed on the quality of journals (i.e., by impact factor) as scoping reviews do not require appraisal of the reviewed literature.

Conclusion

This scoping review offered valuable insight into psycho-social stressors faced by war refugees in developed countries. A key theme was the challenge of “identity-consciousness” during migration status determination, leading to feelings of powerlessness (Basic, 2022; Betancourt et al., 2015b). Being labelled a “refugee” may be an exclusive term, leading to stigmatization compared to the general population (Basic, 2022; Drummond, Johansen & Varvin, 2020). The exploration of whether this identity stress is an inherent aspect of the identity formation process, or an indication of psycho-social maladjustment warrants further research investigation. As language barriers hinder acculturation (Atrooz et al., 2022), facilitating language learning can aid integration and psycho-social outcomes. Recovery programs should address trauma and promote education and language skills to counter post-migration stressors (Kartal et al., 2019). Visible and religious minorities have distinct needs requiring tailored interventions. Building social support systems and community affiliations becomes crucial (Betancourt et al., 2015b). Culturally sensitive research is essential to address trauma's intergenerational impact on war refugees in developed countries (Flanagan et al., 2020; Drummond Johansen & Varvin, 2020). While mainly transmitted through parental neglect, it is vital to consider the resilience and positive intentions of parents who are themselves victims of traumatic experiences. Despite hopes of a better life, refugees fleeing war to developed countries must face “a new type of war” while confronting unrelenting hegemonic power differentials at every step of their migration journey. An intersectional approach must be taken to reduce the psycho-social burden, considering factors such as arriving unaccompanied, religious minority status and having trauma-exposed parents.

This scoping review highlights the urgent need for specific policies and governmental resources to address the psycho-social stressors faced by young war refugees. Ensuring young refugees have access to culturally and linguistically appropriate mental health services is crucial. This can be achieved through initiatives such as integrating mental health screenings into routine health check-ups and providing funding for community-based mental health programs (Betancourt et al., 2015b). Implementing educational support programs that cater to the unique needs of young refugees is also vital. These programs should include language acquisition support, tutoring, and trauma-informed educational practices to help them adjust to new learning environments (Patel et al., 2017). Developing services that support refugee families, focusing on community and family-based interventions to improve communication and understanding between parents and children, can have significant positive outcomes (Betancourt et al., 2015b)

Facilitating comprehensive language acquisition programs to improve integration and mental health outcomes is necessary. Intensive language courses for refugees, incorporating culturally sensitive materials that address their specific experiences and needs, should be considered for funding (Atrooz et al., 2022; Rossiter et al., 2015). Addressing structural barriers to employment and providing economic support to alleviate financial strain is equally important. Streamlining the process for recognizing foreign qualifications and providing bridging programs to help refugees transition into the local job market can help mitigate this economic stress (Rossiter et al., 2015). Enhancing community-based social support systems to provide a sense of belonging and practical assistance is crucial. Fostering partnerships between NGOs, community groups, and public services to create robust support networks can significantly benefit young refugees. Establishing community hubs where young refugees can access various support services, including legal aid, employment assistance, and social activities, should be prioritized (Betancourt et al., 2015a).

Granting stable and permanent residency status to reduce psychological distress and uncertainty is critical. Prompt and fair asylum application processing and providing legal assistance to navigate the asylum process and understand rights and responsibilities are necessary steps to achieve this (Thommessen et al., 2015). This review underscores the pervasive psycho-social challenges that young war refugees face, highlighting the urgent need for targeted interventions and policy changes to support their integration and well-being in developed countries. Governments and NGOs should prioritize the implementation of the recommended programs and policies to address the identified stressors. Continuous evaluation and adaptation of these programs are essential to ensure they meet the evolving needs of refugee populations. Further studies are needed to evaluate the effectiveness of these interventions and explore innovative approaches to supporting young refugees. By implementing these recommendations, we can create a more inclusive and supportive environment for young war refugees, helping them overcome the challenges of displacement and build a better future in their host countries.

Author Biographies

Kateryna Metersky: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data Curation, Writing – Original Draft, Writing-Review & Editing, Visualization, Supervision, Project Administration, Funding Acquisition.

Adam Jordan: Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data Curation, Writing – Original Draft, Writing-Review & Editing, Visualization.

Areej Al-Hamad: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – Original Draft, Writing-Review & Editing, Visualization.

Maher El-Masri: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – Original Draft, Writing-Review & Editing, Visualization, Project Administration.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Toronto Metropolitan University,

ORCID iDs: Kateryna Metersky https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2738-0256

Adam Jordan https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2075-6169

Areej Al-Hamad https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6400-0750

Maher El-Masri https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9631-7683

References

- 7 of the world’s largest refugee crises & their effects on hunger. (n.d.). World Food Program USA. https://www.wfpusa.org/articles/largest-refugee-crises-around-world-effects-hunger/

- Arksey H., O’Malley L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Atrooz F., Chen T. A., Biekman B., Alrousan G., Bick J., Salim S. (2022). Displacement and isolation: Insights from a mental stress survey of Syrian refugees in Houston, Texas, USA. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(5), 1–12. 10.3390/ijerph19052547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basic G. (2022). Symbolic interaction, power, and war: Narratives of unaccompanied young refugees with war experiences in institutional care in Sweden. Societies, 12(3), 90. 10.3390/soc12030090 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berry J. W. (2005). Acculturation: Living successfully in two cultures. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 29(6), 697–712. 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2005.07.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt T. S., Abdi S., Ito B. S., Lilienthal G. M., Agalab N., Ellis H. (2015a). We left one war and came to another: Resource loss, acculturative stress, and caregiver-child relationships in Somali refugee families. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 21(1), 114–125. 10.1037/a0037538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt T. S., Abdi S., Ito B. S., Lilienthal G. M., Agalab N., Ellis H. (2015b). We left one war and came to another: Resource loss, acculturative stress, and caregiver-child relationships in Somali refugee families. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 21(1), 114–125. 10.1037/a0037538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogic M., Ajdukovic D., Bremner S., Franciskovic T., Galeazzi G. M., Kucukalic A., Lecic-Tosevski D., Morina N., Popovski M., Schützwohl M., Wang D., Priebe S. (2012a). Factors associated with mental disorders in long-settled war refugees: Refugees from the former yugoslavia in Germany, Italy and the UK. British Journal of Psychiatry, 200(3), 216–223. 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.084764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogic M., Ajdukovic D., Bremner S., Franciskovic T., Galeazzi G. M., Kucukalic A., Lecic-Tosevski D., Morina N., Popovski M., Schützwohl M., Wang D., Priebe S. (2012b). Factors associated with mental disorders in long-settled war refugees: Refugees from the former yugoslavia in Germany, Italy and the UK. British Journal of Psychiatry, 200(3), 216–223. 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.084764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan K. A., Clark C. L., Shaver P. R. (1998). Self-report measurement of adult attachment: An integrative overview. In Attachment theory and close relationships (pp. 46–76). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy J., Jones J. D., Shaver P. R. (2013). Contributions of attachment theory and research: A framework for future research, translation, and policy. Development and Psychopathology, 25(4 0 2), 1415–1434. 10.1017/S0954579413000692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dangmann C., Solberg Ø, Andersen P. N. (2021). Health-related quality of life in refugee youth and the mediating role of mental distress and post-migration stressors. Quality of Life Research, 30(8), 2287–2297. 10.1007/s11136-021-02811-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond Johansen J., Varvin S. (2020). Negotiating identity at the intersection of family legacy and present time life conditions: A qualitative exploration of central issues connected to identity and belonging in the lives of children of refugees. Journal of Adolescence, 80, 1–9. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2020.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fegert J. M., Diehl C., Leyendecker B., Hahlweg K., Prayon-Blum V., Schuler-Harms M., Werding M., Andresen S., Beblo M., Diewald M., Fangerau H., Gerlach I., Kreyenfeld M., Nebe K., Ott N., Rauschenbach T., Spieb C. K., Wa1lper S., & the Scientific Advisory Council of the Federal Ministry of Family Affairs, Senior Citizens, Women and Youth. (2018).

- Flanagan N., Travers A., Vallières F., Hansen M., Halpin R., Sheaf G., Rottmann N., Johnsen A. T. (2020). Crossing borders: A systematic review identifying potential mechanisms of intergenerational trauma transmission in asylum-seeking and refugee families. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 11(1), 1–13. 10.1080/20008198.2020.1790283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George M., Jettner J. (2016a). Migration stressors, psychological distress, and family—A Sri Lankan tamil refugee analysis. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 17(2), 341–353. 10.1007/s12134-014-0404-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- George M., Jettner J. (2016b). Migration stressors, psychological distress, and family—a Sri Lankan tamil refugee analysis. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 17(2), 341–353. 10.1007/s12134-014-0404-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Global Appeal 2023 . (2023). Global focus. http://reporting.unhcr.org/globalappeal2023

- Global trends—forced displacement in 2018—UNHCR . (n.d.). UNHCR Global Trends 2018. https://www.unhcr.org/globaltrends2018/

- The graying of trauma: Revisiting Vietnam’s POWs . (2014). Association for Psychological Science - APS. https://www.psychologicalscience.org/news/were-only-human/the-graying-of-trauma-revisiting-vietnams-pows.html

- Henkelmann J.-R., de Best S., Deckers C., Jensen K., Shahab M., Elzinga B., Molendijk M. (2020). Anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder in refugees resettling in high-income countries: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BJPsych Open, 6(4), e68.<missing element: > 10.1192/bjo.2020.54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodes M., Vostanis P. (2018). Practitioner review: Mental health problems of refugee children and adolescents and their management. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 60(7), 716–731. 10.1111/jcpp.13002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman S. J., Vukovich M. M., Gewirtz A. H., Fulkerson J. A., Robertson C. L., Gaugler J. E. (2020). Mechanisms explaining the relationship between maternal torture exposure and youth adjustment in resettled refugees: A pilot examination of generational trauma through moderated mediation. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 22(6), 1232–1239. 10.1007/s10903-020-01052-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javanbakht A., Rosenberg D., Haddad L., Arfken C. L. (2018). Mental health in Syrian refugee children resettling in the United States: War trauma, migration, and the role of parental stress. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 57(3), 209–211. 10.1016/j.jaac.2018.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javanbakht A., Stenson A., Nugent N., Smith A., Rosenberg D., Jovanovic T. (2021). Biological and environmental factors affecting risk and resilience among Syrian refugee children. Journal of Psychiatry and Brain Science, 6(e210003), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.20900/jpbs.20210003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanji Z., Cameron B. L. (2010). Exploring the experiences of resilience in muslim Afghan refugee children. Journal of Muslim Mental Health, 5(1), 22–40. 10.1080/15564901003620973 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kartal D., Alkemade N., Kiropoulos L. (2019). Trauma and mental health in resettled refugees: Mediating effect of host language acquisition on posttraumatic stress disorder, depressive and anxiety symptoms. Transcultural Psychiatry, 56(1), 3–23. 10.1177/1363461518789538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levac D., Colquhoun H., O'Brien K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science , 5(69), 1–9. 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacMillan K. K., Ohan J., Cherian S., Mutch R. C. (2015). Refugee children’s play: Before and after migration to Australia. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 51(8), 771–777. 10.1111/jpc.12849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel S. G., Staudenmeyer A. H., Wickham R., Firmender W. M., Fields L., Miller A. B. (2017). War-exposed newcomer adolescent immigrants facing daily life stressors in the United States. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 60, 120–131. 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2017.03.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Refugees, U. N. H. C. for. (n.d.-b). What is a refugee? UNHCR. https://www.unhcr.org/what-is-a-refugee.html

- Refugees, U. N. H. C. for. (2023). UNHCR - refugee statistics. UNHCR. https://www.unhcr.org/refugee-statistics/

- Rossiter M. J., Hatami S., Ripley D., Rossiter K. R. (2015). Immigrant and refugee youth settlement experiences: “A new kind of war.”. International Journal of Child, Youth & Family Studies, 6(4–1), 746–770. 10.18357/ijcyfs.641201515056 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scharpf F., Kaltenbach E., Nickerson A., Hecker T. (2021). A systematic review of socio-ecological factors contributing to risk and protection of the mental health of refugee children and adolescents. Clinical Psychology Review, 83(101930), 1–15. 10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheinbaum T., Kwapil T. R., Ballespí S., Mitjavila M., Chun C. A., Silvia P. J., Barrantes-Vidal N. (2015). Attachment style predicts affect, cognitive appraisals, and social functioning in daily life. Frontiers in Psychology, 6(296), 1–10. 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Standard of living by country | quality of life by country 2023. (2023). World Population Review. https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/standard-of-living-by-country [Google Scholar]

- Thommessen S. A. O., Corcoran P., Todd B. K. (2015). Experiences of arriving to Sweden as an unaccompanied asylum-seeking minor from Afghanistan: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Psychology of Violence, 5(4), 374–383. 10.1037/a0038842 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Ee E., Kleber R. J., Mooren T. T. M. (2012). War trauma lingers on: Associations between maternal posttraumatic stress disorder, parent-child interaction, and child development. Infant Mental Health Journal, 33(5), 459–468. 10.1002/imhj.21324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Bank Country and lending groups – world bank data help desk . (n.d.). https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups