Abstract

Objective: The Serious Illness Care Program was developed to support goals and values discussions between seriously ill patients and their clinicians. The core competencies, that is, the essential clinical conversation skills that are described as requisite for effective serious illness conversations (SICs) in practice, have not yet been explicated. This integrative systematic review aimed to identify core competencies for SICs in the context of the Serious Illness Care Program. Methods: Articles published between January 2014 and March 2023 were identified in MEDLINE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, and PubMed databases. In total, 313 records underwent title and abstract screening, and 96 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. The articles were critically appraised using the Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Guidelines, and data were analyzed using thematic synthesis. Results: In total, 53 articles were included. Clinicians’ core competencies for SICs were described in 3 themes: conversation resources, intrapersonal capabilities, and interpersonal capabilities. Conversation resources included using the conversation guide as a tool, together with applying appropriate communication skills to support better communication. Intrapersonal capabilities included calibrating one's own attitudes and mindset as well as confidence and self-assurance to engage in SICs. Interpersonal capabilities focused on the clinician's ability to interact with patients and family members to foster a mutually trusting relationship, including empathetic communication with attention and adherence to patient and family members views, goals, needs, and preferences. Conclusions: Clinicians need to efficiently combine conversation resources with intrapersonal and interpersonal skills to successfully conduct and interact in SICs.

Keywords: clinical competence, health communication, palliative care, serious illness conversations, serious illness care program, systematic review

Introduction

Effective and empathetic communication is a core competency for healthcare professionals, perhaps none more so than for those working with seriously ill patients. It is argued that competence to hold serious illness conversations (SICs) can be taught, learnt, and applied in clinical practice.1,2 Despite myriad studies affirming the importance of developing clinical conversation skills, clinicians have described lacking confidence when it comes to talking to patients about emotional or sensitive topics and feeling uncertain about how to develop competence in discussing such matters.3,4 This can result in clinicians avoiding difficult conversations altogether, thereby restricting opportunities for the provision of person-centered and goal-concordant care.4,5

The Serious Illness Care Program (SICP), inclusive of the Serious Illness Conversation Guide (SICG), was developed by Ariadne Labs (Boston, Massachusetts, USA) to augment discussions around seriously ill patients’ values, goals, preferences, and priorities. 6 The SICP includes structured tools, training, and technical support for program implementation at clinical and organizational levels. 6 The SICP aims to promote more, better, and earlier conversations between clinicians and patients with serious illness 4 and can be undertaken using different formats, including in-person, over the telephone, and using digital mediums. 6 The SICP was initially designed and studied for patients in oncology care and is now being used among diverse patient groups, clinical settings, and professional user groups.7,8 This is encouraging as more patients and family/caregivers in need of SIC have access to them; however, this also poses a challenge for clinicians as it is unclear what essential competencies are needed to use the SICP and SICG to accomplish successful SIC. Competence as a concept is complex to define and several variants exist. 9 It has been described as a multifaceted concept covering more than knowledge acquisition alone, since it includes the understanding and application of knowledge, clinical skills, interpersonal skills, problem-solving, clinical judgment, and technical skills. 10 For this study, core competencies are defined as a mixture of attributes comprising applied knowledge, skills, and attitudes 11 that qualify a clinician to perform SIC competently.

The SICP includes clinician training to build confidence and self-efficacy in conducting SIC. Studies exploring the effect of the SICP have found that targeted SIC resulted in more goal-concordant discussions and improved experiences of palliative care provision for healthcare professionals. 12 While these advancements are promising, there continues to be confusion surrounding the core competencies, that is, the essential clinical conversation attributes that are required to have SIC. Generating a clear outline of the core competencies for SIC in the context of the SICP is critical to inform current and future training approaches, learning strategies, and clinical requisites. This integrative systematic review aimed to identify core competencies for SICs in the context of the SICP.

Methods

Study Design

To ensure methodological rigor and minimize the risk of bias this integrative systematic review was conducted as per the guidelines set out by The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) and has been reported using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Checklist. 13 This study was not registered and the protocol has not been published.

Search Strategy

The bibliographic databases MEDLINE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, and PubMed were searched on the 20th of March 2023. The search terms were developed in collaboration with a university librarian and included: “serious illness program*” OR “serious illness care” OR “serious illness conversation*” OR “serious illness model” OR “serious illness communication.” The full search terms and limiters for each database are provided in Supplemental Material A. The reference lists of the included studies were hand-searched to ensure the completeness of the review. Additionally, Ariadne Labs provided a list of known publications (n = 44) related to the SICP and/or SICG. The sensitivity of the search strategy was confirmed through the identification of seminal publications from the SICP, SICG, and Ariadne Labs in the search results.

Eligibility Criteria

To collect data relevant to the study aim, description/s of core competencies for SIC were sought in articles pertaining to the SICP and/or SICG. Inclusion criteria were developed to ensure that the articles contained information relevant to the study aim (Table 1). As the SICP was established following a literature review from 2014, the search was restricted to articles published between 1 January 2014 and 20 March 2023. If articles were not connected to Ariadne Labs’ SICP/SICG or did not explicitly describe at least one competence related to conducting SIC, they were excluded. Conference papers and letters to the editor were not eligible for inclusion.

Table 1.

Inclusion Criteria.

| Inclusion criteria |

|---|

| (1) Publication date: 1 January 2014 to 20 March 2023 |

| (2) Publication language: English |

| (3) Related to Ariadne Labs’ SICP and/or SICG |

| (4) Meaningful description of (at least one) competency for serious illness conversations |

SICP = Serious Illness Care Program; SICG = Serious Illness Care Guide.

Selection Process

Following the removal of duplicate publications, the first author (SP) scanned all titles, abstracts, keywords, and, if required, the full-text article, to identify those that met the inclusion criteria. Two authors (SP and RB) then screened all full-text articles against the inclusion criteria. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion until a consensus was reached.

Data Collection

Original source data from the methods, results, discussion, and/or conclusions sections of the included articles were eligible for extraction. Original source data were text that was presented as findings, descriptions, interpretations, or ideas written by the author/s of the paper. A data extraction template was developed to gather general information about the article’s characteristics, including the aim, context, study design, and affiliation with the SICP/SICG. A further extraction template was used to organize data describing SIC competencies. To calibrate this process, data from a random sample of six articles were extracted. The second author (RB) then extracted data from all articles, which was then verified by the first author (SP) for consistency and uniformity. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion and reappraisal.

Critical Appraisal

All articles were evaluated by the first author (SP) to assess methodological quality and risk of bias as per the JBI critical appraisal checklists. 14 The checklist that was most consistent with the study design was selected to evaluate the included articles (ie, cross-sectional, case-control, qualitative, etc). As JBI does not yet offer a checklist for mixed methods studies they provided advice via email that multiple checklists should be completed for studies reporting more than one method. Each article was assessed by answering “yes,” “no,” “unclear,” or “not applicable” to the checklist criteria. A random sample (approximately 20%) of the studies were reviewed by RB for comparative evaluation. Any inconsistencies between the reviewers (eg, selection of checklist, quality assessment criteria) were resolved through discussion. As different checklists were used for different study designs the quality assessments were not used to exclude articles but were instead used to provide information regarding the quality and comparability of the included articles to better evaluate their content.

Data Analysis

Thematic synthesis analysis was selected for this study as it allows for the identification and aggregation of patterns across diverse textual sources.15,16 As described by Thomas and Harden, 15 this method comprises 3 stages: free coding, thematic organization, and analytic thematic development. First, textual data were inductively explored for descriptions of SIC competencies and coded accordingly. Next, similar codes were grouped and descriptive subthemes were formulated. Finally, analytical themes were constructed to provide novel interpretations that extended beyond surface-level descriptions to generate new insights from the existing literature. The preliminary themes were discussed among the author group and all authors agreed upon the final results.

Results

Study Selection

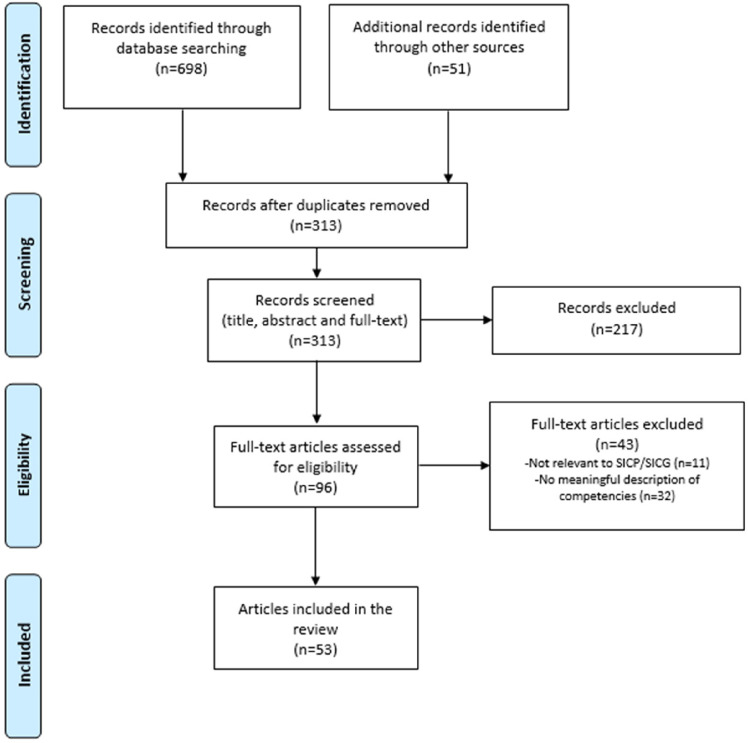

The search revealed 698 studies. Fifty-one additional studies were located through the reference list review (n = 7) and the list of articles provided by Ariadne Labs (n = 44). Of these 749 articles, 436 were duplicates. In total, 53 articles met the inclusion criteria (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Study Characteristics

The majority of the included articles originated from the United States (n = 40) and Canada (n = 10). The remaining articles were from the United Kingdom (n = 1), Sweden (n = 1), and Denmark (n = 1). Of the included articles, 13 used qualitative methods, 15 used some form of mixed methods, and 16 used quantitative methods. Nine articles were categorized using the JBI criteria as text and opinion articles. Detailed JBI critical appraisal checklist responses are presented in online Supplemental Material B. The list of included articles and a summary of their characteristics are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of Included Articles.

| Author/s, Year | Clinical context | Clinicians/users | Country | Critical appraisal checklist/s |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andersson et al, 2022 17 | Acute care hospitals | Physicians | Sweden | Qualitative research |

| Baran et al, 2019 18 | Primary care | Primary care clinicians | USA | Text and opinion |

| Beddard-Huber et al, 2021 19 | General | Physicians, nurse practitioners, nurses, allied health | Canada | Text and opinion |

| Bernacki et al, 2015 20 | Oncology | Nurse practitioners, physician assistants | USA | Text and opinion |

| Borregaard Myrhøj et al, 2022 21 | Multiple myeloma | Physicians, nurses | Denmark | Qualitative research |

| Daly et al, 2022 22 | Family medicine | Physicians, nurses, other clinical staff | USA | Analytical cross-sectional studies |

| Daubman et al, 2020 23 | Multiple contexts | Clinicians—not specified | USA | Analytical cross-sectional studies |

| DeCourcey et al, 2021 24 | Pediatrics | Physicians, nurse practitioners, nurses, psychosocial clinicians | USA | Qualitative research |

| Gace et al, 2020 25 | General medical inpatient | Physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, nurses, social workers | USA | Cohort studies |

| Geerse et al, 2019 26 | Oncology | Physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants | USA | Qualitative research |

| Geerse et al, 2021 27 | Oncology | Physicians, nurse practioners, physician assistants | USA | Analytical cross-sectional studies and qualitative research |

| Greenwald et al, 2020 28 | General medical inpatient | Physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants | USA | Cohort studies |

| Greenwald et al, 2021 29 | Hospital setting | Clinicians—not specified | USA | Quasi-experimental studies |

| Hafid et al, 2021 30 | Primary care | Physicians, residents, nurse practitioners, nurses, social workers | Canada | Qualitative research and quasi-experimental studies |

| Jain et al, 2020 31 | Not stated | Clinicians—not specified | USA | Text and opinion |

| Jacobsen et al, 2022 32 | Not stated | Clinicians—not specified | USA | Text and opinion |

| Karim et al, 2022 33 | Oncology | Physicians, physician assistants, nurse practitioners | USA | Text and opinion |

| King et al, 2022 34 | Internal medicine | Physicians | Canada | Analytical cross-sectional studies |

| Ko et al, 2020 35 | Oncology | Physicians | Canada | Analytical cross-sectional studies |

| Kumar et al, 2020 36 | Outpatient oncology | Physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants | USA | Analytical cross-sectional studies and qualitative research |

| Kumar et al, 2023 37 | Oncology | Physicians, advance practice providers | USA | Quasi-experimental studies |

| Lagrotteria et al, 2021 38 | Tertiary hospitals | Physicians, nurse practitioners, social workers | Canada | Qualitative research |

| Lakin et al, 2019 39 | Primary care | Physicians, nurses, social workers | USA | Qualitative research |

| Lakin et al, 2021 40 | General medicine | Physicians, nurses, physician assistants | USA | Quasi-experimental studies |

| Lally et al, 2020 41 | Hospitalised patients in a complex care management program. | Nurses | USA | Quasi-experimental studies |

| Le et al, 2021 42 | Acute medicine | Physicians, nurses, allied health | Canada | Cohort studies |

| Locastro et al, 2023 43 | Hematology | Physicians, nurses, advance practitioners | USA | Qualitative research |

| Ma et al, 2020 44 | General internal medicine | Physicians, nurse practitioners | Canada | Quasi-experimental studies |

| Mandel et al, 2017 45 | Nephrology | Nephrologists, nurses, social workers, physicians | USA | Text and opinion |

| Mandel et al, 2023 46 | Dialysis | Physicians, social workers | USA | Qualitative research and analytical cross sectional studies |

| Massman et al, 2019 47 | Primary care | Physicians, physician assistants, nurses, medical assistants, social workers | USA | Quasi-experimental studies |

| McGlinchey et al, 2019 48 | U.K. healthcare setting | Clinicians—not specified | UK | Qualitative research |

| Miranda et al, 2018 49 | Oncology | Physicians, nurse practitioners | USA | Analytical cross sectional studies and qualitative research |

| Ouchi et al, 2020 50 | Emergency | Physicians | USA | Text and opinion |

| Paladino et al, 2019 51 | Oncology | Physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants | USA | Randomized controlled trials |

| Paladino et al, 2020 52 | Oncology | Physicians, advance practice clinicians | USA | Analytical cross sectional studies and qualitative research |

| Paladino et al, 2020 53 | Three health systems | Physicians, advance practice clinicians, nurses, social workers, chaplains | USA | Qualitative research and quasi-experimental studies |

| Paladino et al, 2021 54 | Acute and ambulatory care | Physicians, nurses, social workers | USA | Qualitative research |

| Paladino et al, 2021 55 | Primary care | Physicians, nurses, social workers | USA | Qualitative research |

| Paladino et al, 2022 56 | Three U.S. health systems | Physicians, advance practice clinicians, nurses, social workers, chaplains | USA | Qualitative research |

| Pasricha et al, 2020 57 | Intensive care | Physicians, nurses | USA | Analytical cross sectional studies and qualitative research |

| Rauch et al, 2023 58 | Education community health sites | Nursing students | USA | Qualitative research and quasi-experimental studies |

| Reed-Guy et al, 2021 59 | Glioblastoma | Physicians | USA | Analytical cross-sectional studies and qualitative research |

| Sanders et al, 2022 60 | Multiple contexts | Physicians | USA | Qualitative research and quasi-experimental studies |

| Sirianni et al, 2020 61 | COVID-19 | Physicians | Canada | Text and opinion |

| Swiderski et al, 2021 62 | Primary care/community health | Physicians | USA | Qualitative research |

| Tam et al, 2019 63 | Family medicine, internal medicine | Medical students | Canada | Qualitative research and quasi-experimental studies |

| Thamcharoen et al, 2021 64 | Advanced kidney disease | Researcher | USA | Analytical cross-sectional studies and qualitative research |

| Van Breemen et al, 2020 65 | Pediatrics | Physicians, nurse practitioners, nurses, counselors | Canada | Case reports |

| Vergo et al, 2022 66 | Rural tertiary care center | Internal medicine residents | USA | Quasi-experimental studies |

| Wasp et al, 2021 67 | Hematology-Oncology | Oncology fellows | USA | Qualitative research and quasi-experimental studies |

| Xu et al, 2022 68 | Primary care | Physicians | USA | Qualitative research |

| Zehm et al, 2021 69 | Education | Medical students and interns | USA | Qualitative research and quasi-experimental studies |

Thematic Synthesis

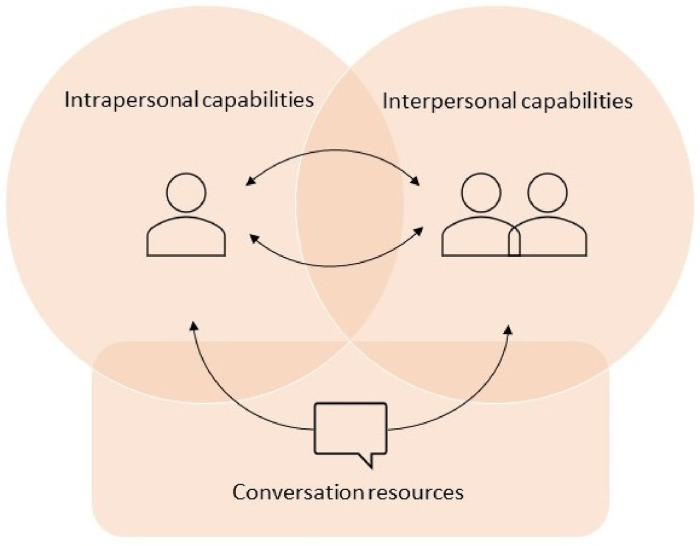

Core competencies for SIC are described in 3 themes: (1) conversation resources, (2) intrapersonal capabilities, and (3) interpersonal capabilities. The themes describe what the competencies are, and the subthemes describe how the competencies are applied. For an overview of themes and subthemes, see Table 3.

Table 3.

Overview of Core Competencies for SIC.

| Themes | Subthemes |

|---|---|

| Conversation resources | Communicating with SICG as a tool |

| Applying appropriate communication skills | |

| Intrapersonal capabilities | Calibrating attitudes and mindset |

| Feeling confident | |

| Interpersonal capabilities | Building connectedness |

| Demonstrating compassion | |

| Adjusting to preferences and conditions |

SIC, serious illness conversation; SICG, Serious Illness Conversation Guide.

Since competencies overlap and interlock, the themes and subthemes are not fully externally heterogeneous. Consequently, all competencies are important, and the clinician needs to be able to efficiently combine conversation strategies with intrapersonal and interpersonal skills to successfully conduct and interact in SIC. The 3 overarching core competencies and their relations are visualized in Figure 2. The arrows denote interactions between the 3 themes. The 2 arrows between the clinician—intrapersonal capabilities—and the meeting between clinician and patient—interpersonal capabilities—symbolize the circularity that exists between them. Meaning that intrapersonal capabilities can influence interpersonal capabilities and vice versa. Thus, having awareness of, and the ability to manage one's own attitudes and emotions can affect the success of the interpersonal aptitude of building connectedness, having an empathetic approach, and adapting the conditions to the patient as a person. Likewise, what happens in the interpersonal meeting influences the clinician's confidence and attitudes. The arrow going through conversation resources implies that efficient use of the SICG, together with applying appropriate communication skills, can influence the clinician's intrapersonal capability as well as enhance the success of the interpersonal meeting.

Figure 2.

Conceptual model of core competencies for serious illness conversations.

Conversation resources

Conversation resources included using the SICG as a tool while applying appropriate communication skills such as intentional silence, mirroring, and reflective questions. The content and structure of the SICG are followed in a flexible manner attuned to the clinician, patient, and family/caregivers.

Communicating with SICG as a tool

Using the guide effectively is a competence. 53 The SICG was described as a tool that could be used to have a value-oriented44,52 active listening conversation 19 by using the structure12,20,24,26,39,53,64 and asking the questions. Thus, the SICG offers a framework to structure SIC 53 with concrete language 53 and appropriate vocabulary.53,63,69 The guide demystified SIC 69 and provided an agenda that went beyond mere conversations about highly medicalized end-of-life treatment preferences 38 that is, focusing on goals instead of medical interventions. 39 Optimal use of the guide 53 included being able to elaborate upon the questions within it including enhancing their depth and breadth by asking questions such as “can you tell me more” and “what else.” 23 This also included asking clarifying and follow-up questions,19,20,23 and utilizing examples if the patient does not grasp the question. 19

To use the guide authentically, clinicians may need to adjust the guide to themselves 18 as well as their patient population and culture.18,45,63,68 Clinicians should adapt the language to flow naturally in the conversation48,55 by including normalizing elements,48,55 and avoiding reading the guide verbatim or having an interview-like conversation. 48 Adapting the guide to the patient required flexibility in thinking and operational style. This included language and format adjustments in accordance with patient needs 18 and what was important to the patient. 48 This means that clinicians should be able to incorporate the guide structure with patient responses. 23 Flexibility was required in the application of the guide to respond to patient signals. 63 “In the moment” use of the guide was described as desirable.19,65 The SICG could be used as a whole 65 but should not be seen as fixed. 48 Clinicians needed to choose when to use the guide questions23,55 and when to adjust the guide structure.50,55 Additionally, it was important to be ready to move “in” and “out” of the conversation to deal with present and urgent issues. 19 Moreover, all guide elements did not need to be covered during a single conversation. 31 Competence comes with practice, where the ability to actively listen without thinking about what to say 65 and using the SICG “on the fly” 38 advanced over time. Consequently, clinicians must find a balance between using the structure of the SICG and showing flexibility, 63 for example by adjusting formulations to suit the patient. 45 This is because people receive and share information in different ways and a one-size fits all framework may not function optimally. 24 Taken together, SIC competencies ranged from a basic reading of the guide to more advanced competencies consisting of variation, clinical judgement, and creativity. 66

Applying appropriate communication skills

Clinicians needed to be able to apply their unique communication skillset to appropriately navigate SIC. 31 Deep 65 and active listening were necessary competencies for SIC.19,34,61,65,67 Intentional silence 18 could be utilized as a communication skill, where the clinician could choose when to respond directly and when to use the power of silence.18,20,23,36,53 Using silence allowed patients to process information,20,40,54 express emotions20,26,40 and thoughts. 26 Speaking less than half of the time was a rule of thumb20,26,30,36,40,53,61,63 which created space for the patient's voice to be heard20,54 and for processing and reflection.20,21,52,63,65

Person-centered 54 and gentle relatable language should be used 52 that avoids medical jargon 31 and lengthy monologues. 26 Language and general tone could promote a supportive dialog 26 which meant using neutral language 19 and broader use of language—from medical to existential. 21 Using open-ended questions was preferable18,26,35,53,54 since they empowered patients to share their stories. 54 Additionally, it was important to create a respectful setting for SIC. 18 Mirroring was a conversation skill that clinicians could apply to support patients to articulate and reflect upon their thoughts and emotions. 23 Difficult emotions must be acknowledged. 40 As such, emotion handling skills,67,68 including addressing and responding to emotions18,20,23,26,36,45,53,63,65,68 were essential. Embracing deep listening, 65 avoiding looking away 36 and using silence53,54 were nonverbal communication skills that could be used to respond to emotions. However, premature reassurance should be avoided and responding to emotions should be addressed by providing further explanations, rather than information alone. 20

Intrapersonal capabilities

This theme included awareness of, and the ability to, interpret and calibrate the clinician's own attitudes and mindset to the SIC and the patient. Feeling confident comprised of self-assurance in engaging in SIC and included reflecting on clinicians’ comfort and possible discomfort.

Calibrating attitudes and mindset

The mindset and attitude of the clinician were connected to competence in having SIC. 53 Shifting values in the context of SICP was achievable. 53 Clinician attitudes toward SIC functioned both as an enabler and a barrier. 17 This could be understood as having attitudes that either facilitated (ie, supported successful SIC) or constrained (ie, hindered successful SIC) competent engagement in SIC. Constraining attitudes could be reluctance to have SIC, concerns about the guide 53 or causing suffering17,53 and anxiety, 56 including fears of taking away hope. 17 Furthermore, SIC could conflict with the professional role “to treat,” thereby hindering the adoption of SIC. 56 On the other hand, acknowledging the value of SIC53,63 and viewing SIC as meaningful,28,38,52 favorable, 22 important, 53 humanizing,38,62 and supportive in times of crisis 54 could be understood as facilitating attitudes (ie, supported successful mastery of SIC). Putting patient values in front of their own values 31 and building facilitating attitudes was necessary. 53 Additionally, attention to attitudes in relation to medical culture was needed. 27 Shifting clinical values from a “medical focus” to a “person focus” with patient values at the forefront was possible.38,53

Feeling confident

The clinician needed to broach SIC with comfort and confidence.30,40,53,55 Having the SICG can support the clinician,41,46,51,52 however, the individual skills of the clinician were vital to its implementation. 48 Confidence was required when soliciting values in relation to the patient's illness, 67 feeling comfortable when exploring patient values and goals, 55 and responding to emotions. 40 Furthermore, it was important to feel confident in using silence, 40 bringing up sensitive issues, 30 such as trajectories, fears and wishes, as well as when conveying serious updates, managing conflicts, responding to unacceptance, and counseling patient requests. 42 Uncertainty in how to express oneself47,51,58 and feeling discomfort 30 were barriers to successful SIC.30,47,51 Consequently, the clinician needed to know how to act in challenging situations, 40 such as when patients or family members expressed certain behaviors or emotions like crying, anger, denial, or avoidance. 20 Clinician confidence and investment in SIC allowed them to take responsibility for these conversations. 31 Discomfort and uncertainty could arise in the presence of strong emotions, low prognostic awareness by the patient, when delivering unwanted news and when worrying about upsetting the patient. 31

The discomfort was especially described in relation to discussing prognosis.23,27,33,55 Balancing hope and reality could be challenging 59 but it was vital for clinicians to have the capability to give honest statements 19 on what could lie ahead. 59 It was also important to acknowledge uncertainty and frame possibilities 45 and discuss hope and positivity even in relation to poor prognosis. 43 Recognizing reality while supporting hope was described as “gentle directness.” 26 Clinicians portray this in practice by using the dual approach of “hoping for the best and preparing for the worst,”35,45 discussing SIC from a “hope and worry” perspective,18,69 or using the wish, worry, wonder framework. 65

Becoming emotionally drained26,37,56,62 or feeling that engaging in SIC could bring back unpleasant memories from experiences of loss added another dimension to clinicians’ fears. 58 Moreover, clinician comfort when approaching and discussing prognosis varied and was contingent on the role of the clinician, their experiences, culture, practice, and institution. 23 Overall, reflecting on the root of one's discomfort in SIC was a vital competence, 31 including the clinicians’ own cultural beliefs, personal biases, and possible stereotypes. 58

Interpersonal capabilities

This theme focused on the clinician's ability to interact with the patient and family members to foster a mutually trusting relationship. It included empathetic communication, as well as attention and adherence to the situation and views of the patient and their family.

Building connectedness

Creating a sense of connection was necessary when developing therapeutic relationships in which skillful communication could occur. 19 To build this connectedness in practice, the clinician needed to learn about the patient 35 as a person 31 and how to be engaged in a partnership.45,48 This included probing deeper to gain an understanding of what makes life meaningful for the patient. 61 Furthermore, clinicians needed to provide space for family members to share their stories and understanding of the situation. 50 Well-established relationships enhanced complex and emotional SIC,24,39 while poorly established relationships lowered trust. 39 The importance of building rapport,50,54,60 clinician–patient alliance, 68 relationships,39,52,60,68 closeness, 52 warmth, and comfort 26 were highlighted. The SICG could support connecting with patients, 60 relationship development, 62 building trust, and positive relationships. 57 The clinician could create a sense of connection in the way that they enacted the conversation 19 and by making it easier to have a challenging conversation by “smoothing the path.” 45 Using “we” statements facilitated opportunities to develop a shared understanding. 24

Building connection was furthermore linked to demonstrating strong rapport, which should be pursued early in the conversation. 54 This could be built by referring to shared patient and clinician histories,26,54 using humor in a hard situation, 26 and asking about and recognizing family members.21,26 Therapeutic alignment was central31,32,38,50 for building trust 50 and signaled that patient's experience was essential to the therapeutic relationship. 32 Moreover, attention to disparities in power dynamics between patient and clinician was required. 33 Consequently, an open and equal dialogue should be pursued. 21 Asking and seeking permission from patients and family members18–20,24,31,35,45,50,54,63,65,66 was another aspect of building connectedness. This included agreeing upon who should take part in the conversation, 45 whether illness progression and prognosis should be discussed,50,63 and whether to proceed further with the discussion.31,35,54 Seeking permission fostered psychosocial safety for the patient 18 and encouraged patients to maintain control over the discussion. 54

Demonstrating Compassion

Demonstrating compassion included empathy and appropriate self-disclosure. Interpersonal competencies linked to empathy and self-disclosure encompassed being candid without being emotionally distant.50,60 This meant that the physician needed to get to know the patient on a personal level. 32 Clinicians should take an empathetic approach to SIC28,31,32 with appropriate empathetic communication skills. 61 In addition to verbal empathy, a demonstration of nonverbal empathy was needed.18,35,54 Empathetic nonverbal techniques included sitting down, 35 being aware of one's facial expressions, 54 making eye contact, 35 and using therapeutic touch when appropriate. 54 Responding to emotion using silence could likewise demonstrate nonverbal empathy. 18 Demonstrating compassion when conducting SIC through telehealth could be challenging as it was not possible to see the whole person thus making it harder to respond to unspoken emotions and body language. 43

Regarding verbal empathy, the wording in the SICG itself supported empathetic communication.19,23,69 Demonstrating verbal empathy included using caring language, 54 understanding and naming emotions, stating respect, and offering support. 35 Empathetic statements or actions should be used when responding to emotion,20,31 offering recommendations, 50 and managing prognosis-related responses. 23 Thus, empathetic and compassionate communication 54 could support patient and family receptiveness and their ability to make choices that are best for them. 31 The clinician should demonstrate non-abandonment 31 and acknowledge the patient and family's emotions.18,20,53 Provision of reassurance was central, 26 but should be authentic. 31

Adapting to preferences and conditions

Adapting to preferences and conditions included trying to comprehend the patient from different viewpoints. This encompassed their holistic needs, 48 including personal ambitions and goals,25,45 as well as their health-related goals, including care preferences39,45 and priorities. 59 This also meant delving into patient concerns, 40 including their personal and health-related fears and worries, 45 by listening to patient expressions of illness understanding, losses, and uncertainties. 31 Adapting to patient preferences and conditions required the cultivation of a deep and nuanced discussion, 49 reflections,19,50,63 responding to expressed needs,48,50 and focusing on what was important to the patient.21,22,26,32,39,52,61

Adapting also included tailoring SIC to information preferences18,26,35,39,45,48,52,53 and making recommendations, planning and decisions with patient understanding, goals and values in mind.26,32,38–40,45,48,50,52,65 However, it was important to stress that it was not necessary to make decisions, solve problems, or reach conclusions about care.19,26,45 Moreover, clinicians must tailor the discussion to patient understanding, 52 receptiveness, 20 and readiness.45,53,55 At the same time, the role of the clinician also included guiding the patient's illness understanding 26 by gently clarifying misunderstandings 19 or unrealistic expectations, 57 filling in knowledge gaps, 45 and reframing patients’ expectations if necessary. 26 Clinicians should be aware that patient preferences could vary depending on cultural beliefs,31,42 which required respect 31 and culturally appropriate engagement in SIC 42 to build cultural safety. 33 Personal and societal characteristics and circumstances could vary, and clinicians should be mindful of language barriers,34,62 prior negative experiences of racism in healthcare, religions, health literacy, physical and cognitive ability, mental illness, poverty, or difficult family dynamics. 62 It was therefore important for clinicians to be prepared to manage and adapt SIC according to patient and family contexts. 62

Discussion

This integrative systematic review identified core competencies for SIC. Skilled use and intuitive modification of conversation resources were necessary to meet the specific and individual needs of patients. This involved engaging intrapersonal capabilities within and around oneself, including tuning into attitudes and emotions and developing comfort and confidence discussing sensitive subjects. The findings emphasized that interpersonal capabilities that build and strengthen relationships and trust are foundational competencies for SIC.

Conversation guides and resources can act as a roadmap during important healthcare discussions to ensure that essential topics are addressed comprehensively. The structure of the SICG supports clinicians to focus on discussing patient values, goals and priorities, instead of focusing solely on medicine, procedures, and treatments.12,70 Patients experience satisfaction when reflecting on wishes and goals of care, 71 and these discussions promote inclusion of people who are important to the patient, including their family, but also friends, caregivers, and others. 6 One of the benefits of using a structured approach to clinical conversations is that standards of communication can be innovated, maintained, measured, and evaluated. 72 This study revealed core competencies that describe not only “what” physicians do in SIC, but “how” they use and adapt structured conversation resources like the SICG. It is therefore important to further explore the balance between teaching a structured framework for these conversations while also promoting flexibility in clinicians’ approach to tailoring SIC for individual patients.

Advanced intra- and interpersonal communication skills can be enhanced through training to promote the integration of patient values and goals into treatment decisions. 73 Training has been found to improve physicians’ understanding and expression of empathy and compassion by targeting specific behaviors and skills, such as detecting patients’ nonverbal emotional indicators, recognizing moments for compassion, conveyance of caring, and statements of validation and support. 74 Despite training in SIC, Wasp et al 75 concluded that physicians did not have full awareness of emotion regulation strategies in serious illness communication. Physicians described focusing on promoting reasonable hope in prognostic disclosure and building trusting and supportive relationships with patients. Yet, physicians’ own emotions in SIC were found to be variable and could conflict with their observed or expressed behavior. 75 It seems clinician-learners could benefit from the opportunity to critically explore and identify their conscious and subconscious communication competencies, to develop what Lane and Roberts have termed “contextual reflective competence.” 76 The findings from this study point toward the need for development of ongoing processes for reflection and support for clinicians to explore their beliefs, experiences and challenges in SIC as their intra- and interpersonal communication skills grow and develop.

SIC lives in the context of therapeutic alliance and relationships. Relational elements of communication are important and have a significant impact on building trust, improved adherence to treatment plans, and better overall health outcomes. 77 Relationship-centered communication interventions have been linked to improved patient satisfaction and reduced clinician burnout. 78 Patients and clinicians have both endorsed the importance of relationships in expressions and understandings of clinical empathy. 79 A clinician who is relationship-oriented has been described as someone who “seeks to diminish the status gap in order to connect person-to-person with the patient” 79 (Hall et al, p. 1240). Communication behaviors such as listening, understanding feelings and perspectives, and showing interest in the whole person are thought to augment patients’ experiences of empathy. 79 The person-centered alliance that can be built in SIC may also be viewed from an equity standpoint, as literature shows that people from underrepresented or marginalized communities are less likely to receive positive nonverbal rapport-building communication and interactions that build trustworthiness. 80 This is also important as it may diminish clinicians’ reliance solely on observed role modeling and self-practice to refine their capabilities. 81 However, such interventions require support and commitment across all levels of the care continuum, inclusive of clinicians, leadership, and organizational structures. 82 Developing a systems-level focus toward improving communication skills and delivering empathic and goal-concordant care may therefore better streamline and improve SIC experiences and outcomes. 83

Strengths and Limitations

A strength is that this review followed rigorous guidelines to identify relevant literature. Detailed descriptions of the search, selection, extraction, and analysis process have been provided and novel interpretations using thematic synthesis have been produced. There are several limitations to the review. This study only examined articles related to the SICP/SICG, so it is likely that these competencies will reflect some of the content from the program or guide. Competencies required for other serious illness communication training programs or guides (ie, not connected to Ariadne Labs’ SICP/SICG) were not explored as this was outside the study scope. It is possible that other care concepts and conversation models, for example, palliative care conversations and advanced care planning conversations, may cover related and/or comparable components. We suggest that future studies build upon these results to compare the conceptual and conversational aspects in relation to clinician competence. Lastly, 4 authors in the current study authored several included articles (SA (n = 1), JP (n = 16), EKF (n = 7), AS (n = 1)). To minimize the risk of bias, these authors were not involved in the article selection, data extraction or quality appraisal processes.

Conclusions

Core competencies for SIC encompass a combination of conversation resources, intrapersonal capabilities, and interpersonal capabilities. Clinicians’ aptitude in communication, relationship-building, self-efficacy, and use of resources impact their competence to undertake SIC. Future training in SIC could focus on enhancing these areas to improve the quality of these conversations for patients and clinicians.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-pal-10.1177_08258597241245022 for Core Competencies for Serious Illness Conversations: An Integrative Systematic Review by Susanna Pusa, Rebecca Baxter, Sofia Andersson and Erik K. Fromme, Joanna Paladino, Anna Sandgren in Journal of Palliative Care

Footnotes

Authorship: All authors made substantial contributions. SP performed the initial searches and screening in consultation with RB. SP and RB conducted the full-text article screening. SP evaluated the quality appraisals in consultation with RB. Data were extracted by SP and RB. All authors contributed to the analysis, interpretation, and final results. SP and RB wrote the manuscript draft, and all authors critically reviewed, edited, and revised the text. SP is the guarantor for the study. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Several authors (SA, AS, JP, and EKF) authored articles that were reviewed in this study. These authors were not involved in the article selection, data extraction or quality appraisal processes. EKF and JP are faculty in Ariadne Labs’ Serious Illness Care Program.

Data Management and Sharing: Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available. The full dataset of included studies is available from the respective publishers.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Kamprad Family Foundation for Entrepreneurship, Research, and Charity (Grant No. 20210163).

ORCID iDs: Susanna Pusa https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4773-8796

Rebecca Baxter https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6595-6298

Sofia Andersson https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1728-5722

Anna Sandgren https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3155-575X

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Bloom JR, Marshall DC, Rodriguez-Russo C, Martin E, Jones JA, Dharmarajan KV. Prognostic disclosure in oncology – current communication models: A scoping review. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2022;12(2):167-177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pease NJ, Sundararaj JJ, O’Brian E, Hayes J, Presswood E, Buxton S. Paramedics and serious illness: communication training. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2022;12(e2):e248-e255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bergenholtz H, Missel M, Timm H. Talking about death and dying in a hospital setting – a qualitative study of the wishes for end-of-life conversations from the perspective of patients and spouses. BMC Palliat Care. 2020;19(1):168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernacki RE, Block SD. Communication about serious illness care goals: A review and synthesis of best practices. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(12):1994-2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bailey S-JCK. Talking about dying: How to begin honest conversations about what lies ahead. 2018. https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/outputs/talking-about-dying-how-begin-honest-conversations-about-what-lies-ahead (accessed 5 March 2023).

- 6.Serious Illness Care: Ariadne Labs. 2023. [cited n.d.] https://www.ariadnelabs.org/serious-illness-care/ (accessed 2 March 2023).

- 7.Baxter R, Fromme EK, Sandgren A. Patient identification for serious illness conversations: a scoping review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(7):4162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baxter R, Pusa S, Andersson S, Fromme EK, Paladino J, Sandgren A. Core elements of serious illness conversations: an integrative systematic review. BMJ Support Palliat Care. Published online February 13, 2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stoof A, Martens RL, van Merriënboer JJG, Bastiaens TJ. The boundary approach of competence: a constructivist aid for understanding and using the concept of competence. Hum Resour Dev Rev . 2002;1(3):345-365. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Norman GR, Neufeld VR. Assessing Clinical Competence. Springer; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moynihan S, Paakkari L, Välimaa R, Jourdan D, Mannix-McNamara P. Teacher competencies in health education: results of a Delphi study. PLoS One. 2015;10(12):e0143703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bernacki R, Paladino J, Neville BA, et al. Effect of the serious illness care program in outpatient oncology: a cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(6):751-759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Br Med J. 2021;372:n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joanna Briggs Institute critical appraisal tools. [cited n.d.] https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools (accessed 2 March 2023).

- 15.Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8(45). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harden A, Thomas J. Methodological issues in combining diverse study types in systematic reviews. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(3):257-271. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andersson S, Sandgren A. Organizational readiness to implement the serious illness care program in hospital settings in Sweden. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22(1):539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baran CN, Sanders JJ. Communication skills: delivering bad news, conducting a goals of care family meeting, and advance care planning. Prim Care. 2019;46(3):353-372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beddard-Huber E, Strachan P, Brown S, et al. Supporting interprofessional engagement in serious illness conversations: an adapted resource. J Hosp Palliat Nurs. 2021;23(1):38-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bernacki R, Hutchings M, Vick J, et al. Development of the serious illness care program: a randomised controlled trial of a palliative care communication intervention. BMJ Open. 2015;5(10):e009032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Borregaard Myrhøj C, Novrup Clemmensen S, Sax Røgind S, Jarden M, Toudal Viftrup D. Serious illness conversations in patients with multiple myeloma and their family caregivers-A qualitative interview study. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2022;31(1):e13537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Daly J, Schmidt M, Thoma K, Xu Y, Levy B. How well are serious illness conversations documented and what are patient and physician perceptions of these conversations? J Palliat Care. 2022;37(3):332-340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Daubman BR, Bernacki R, Stoltenberg M, Wilson E, Jacobsen J. Best practices for teaching clinicians to use a serious illness conversation guide. Palliat Med Rep. 2020;1(1):135-142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DeCourcey DD, Partin L, Revette A, Bernacki R, Wolfe J. Development of a stakeholder driven serious illness communication program for advance care planning in children, adolescents, and young adults with serious illness. J Pediatr. 2021;229:247-258.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gace D, Sommer RK, Daubman BR, et al. Exploring patients’ experience with clinicians who recognize their unmet palliative needs: an inpatient study. J Palliat Med . 2020;23(11):1493-1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Geerse OP, Lamas DJ, Sanders JJ, et al. A qualitative study of serious illness conversations in patients with advanced cancer. J Palliat Med. 2019;22(7):773-781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Geerse OP, Lamas DJ, Bernacki RE, et al. Adherence and concordance between serious illness care planning conversations and oncology clinician documentation among patients with advanced cancer. J Palliat Med. 2021;24(1):53-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Greenwald JL, Greer JA, Gace D, et al. Implementing automated triggers to identify hospitalized patients with possible unmet palliative needs: assessing the impact of this systems approach on clinicians. J Palliat Med. 2020;23(11):1500-1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Greenwald JL, Abrams AN, Park ER, Nguyen PL, Jacobsen J. PSST! I need help! development of a peer support program for clinicians having serious illness conversations during COVID-19. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(4):1094-1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hafid A, Howard M, Guenter D, et al. Advance care planning conversations in primary care: a quality improvement project using the serious illness care program. BMC Palliat Care. 2021;20(1):122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jain N, Bernacki RE. Goals of care conversations in serious illness: a practical guide. Med Clin North Am. 2020;104(3):375-389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jacobsen J, Bernacki R, Paladino J. Shifting to serious illness communication. Jama. 2022;327(4):321-322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karim S, Levine O, Simon J. The serious illness care program in oncology: Evidence, real-world implementation and ongoing barriers. Curr Oncol. 2022;29(3):1527-1536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.King S, Douglas M, Javed S, et al. Content of serious illness care conversation documentation is associated with goals of care orders-a quantitative evaluation in hospital. BMC Palliat Care. 2022;21(1):116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ko JJ, Ballard MS, Shenkier T, et al. Serious illness conversation-evaluation exercise: a novel assessment tool for residents leading serious illness conversations. Palliat Med Rep. 2020;1(1):280-290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kumar P, Wixon-Genack J, Kavanagh J, Sanders JJ, Paladino J, O'Connor NR. Serious illness conversations with outpatient oncology clinicians: understanding the patient experience. JCO Oncol Pract. 2020;16(12):e1507-e15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kumar P, Paladino J, Gabriel PE, et al. The serious illness care program: implementing a key element of high-quality oncology care. NEJM Catal Innov Care Deliv. 2023;4(2):1-15. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lagrotteria A, Swinton M, Simon J, et al. Clinicians’ perspectives after implementation of the serious illness care program: a qualitative study. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(8):e2121517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lakin JR, Benotti E, Paladino J, Henrich N, Sanders J. Interprofessional work in serious illness communication in primary care: a qualitative study. J Palliat Med . 2019;22(7):751-763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lakin JR, Arnold CG, Catzen HZ, et al. Early serious illness communication in hospitalized patients: a study of the implementation of the speaking about goals and expectations (SAGE) program. Healthc (Amst). 2021;9(2):100510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lally K, Tuya Fulton A, Ducharme C, Scott R, Filpo J. Using nurse care managers trained in the serious illness conversation guide to increase goals-of-care conversations in an accountable care organization. J Palliat Med. 2020;23(1):112-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Le K, Lee J, Desai S, Ho A, van Heukelom H. The surprise question and serious illness conversations: a pilot study. Nurs Ethics. 2021;28(6):1010-1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.LoCastro M, Sanapala C, Mendler JH, et al. Adaptation of serious illness care program to be delivered via telehealth for older patients with hematologic malignancy. Blood Adv . 2023;7(9):1871-1884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ma C, Riehm LE, Bernacki R, Paladino J, You JJ. Quality of clinicians’ conversations with patients and families before and after implementation of the serious illness care program in a hospital setting: a retrospective chart review study. CMAJ Open. 2020;8(2):E448-E454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mandel EI, Bernacki RE, Block SD. Serious illness conversations in ESRD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12(5):854-863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mandel EI, Maloney FL, Pertsch NJ, et al. A pilot study of the serious illness conversation guide in a dialysis clinic. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2023;40(10):1106-1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Massmann JA, Revier SS, Ponto J. Implementing the serious illness care program in primary care. J Hosp Palliat Nurs. 2019;21(4):291-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McGlinchey T, Mason S, Coackley A, et al. Serious illness care programme UK: assessing the ‘face validity’, applicability and relevance of the serious illness conversation guide for use within the UK health care setting. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miranda SP, Bernacki RE, Paladino JM, et al. A descriptive analysis of end-of-life conversations with long-term glioblastoma survivors. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2018;35(5):804-811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ouchi K, Lawton AJ, Bowman J, Bernacki R, George N. Managing code status conversations for seriously ill older adults in respiratory failure. Ann Emerg Med. 2020;76(6):751-756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Paladino J, Bernacki R, Neville BA, et al. Evaluating an intervention to improve communication between oncology clinicians and patients with life-limiting cancer: a cluster randomized clinical trial of the serious illness care program. JAMA Oncol . 2019;5(6):801-809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Paladino J, Koritsanszky L, Nisotel L, et al. Patient and clinician experience of a serious illness conversation guide in oncology: a descriptive analysis. Cancer Med. 2020;9(13):4550-4560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Paladino J, Kilpatrick L, O'Connor N, et al. Training clinicians in serious illness communication using a structured guide: evaluation of a training program in three health systems. J Palliat Med. 2020;23(3):337-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Paladino J, Mitchell S, Mohta N, et al. Communication tools to support advance care planning and hospital care during the COVID-19 pandemic: a design process. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2021;47(2):127-136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Paladino J, Brannen E, Benotti E, et al. Implementing serious illness communication processes in primary care: a qualitative study. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2021;38(5):459-466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Paladino J, Sanders J, Kilpatrick LB, et al. Serious illness care programme-contextual factors and implementation strategies: a qualitative study. BMJ Support Palliat Care. Published online February 15, 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pasricha V, Gorman D, Laothamatas K, Bhardwaj A, Ganta N, Mikkelsen ME. Use of the serious illness conversation guide to improve communication with surrogates of critically ill patients. A Pilot Study. ATS Sch. 2020;1(2):119-133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rauch L, Dudley N, Adelman T, Canham D. Palliative care education and serious illness communication training for baccalaureate nursing students. Nurse Educ . 2023;48(4):209-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Reed-Guy L, Miranda SP, Alexander TD, et al. Serious illness communication practices in glioblastoma: an institutional perspective. J Palliat Med. 2022;25(2):234-242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sanders JJ, Durieux BN, Cannady K, et al. Acceptability of a serious illness conversation guide to black Americans: results from a focus group and oncology pilot study. Palliat Support Care. 2023;21(5):788-792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sirianni G, Torabi S. Addressing serious illness conversations during COVID-19. Can Fam Physician. 2020;66(7):533-536. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Swiderski D, Georgia A, Chuang E, Stark A, Sanders J, Flattau A. I was not able to keep myself away from tending to her immediate needs: primary care Physicians’ perspectives of serious illness conversations at community health centers. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(1):130-136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tam V, You JJ, Bernacki R. Enhancing medical learners’ knowledge of, comfort and confidence in holding serious illness conversations. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2019;36(12):1096-1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Thamcharoen N, Nissaisorakarn P, Cohen RA, Schonberg MA. Serious illness conversations in advanced kidney disease: a mixed-methods implementation study. BMJ Support Palliat Care. Published online March 17, 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.van Breemen C, Johnston J, Carwana M, Louie P. Serious illness conversations in pediatrics: a case review. Children (Basel). 2020;7(8):102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vergo MT, Cullinan A, Wilson M, Wasp G, Foster-Johnson L, Low-Cost AR. Low-resource training model to enhance and sustain serious illness conversation skills for internal medicine residents. J Palliat Med. 2022;25(11):1708-1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wasp GT, Cullinan AM, Chamberlin MD, Hayes C, Barnato AE, Vergo MT. Implementation and impact of a serious illness communication training for hematology-oncology fellows. J Cancer Educ. 2021;36(6):1325-1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Xu L, Sommer RK, Nyeko L, Michael C, Traeger L, Jacobsen J. Patient perspectives on serious illness conversations in primary care. J Palliat Med. 2022;25(6):940-944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zehm A, Scott E, Schaefer KG, Nguyen PL, Jacobsen J. Improving serious illness communication: testing the serious illness care program with trainees. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2022;63(2):e252-e259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Andersson S, Granat L, Baxter R, et al. Translation, adaptation, and validation of the Swedish serious illness conversation guide. J Palliat Care. 2024;39(1):21-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bigelow S, Medzon R, Siegel M, Jin R. Difficult conversations: outcomes of emergency department nurse-directed goals-of-care discussions. J Palliat Care. 2024;39(1):3-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sanders JJ, Curtis JR, Tulsky JA. Achieving goal-concordant care: a conceptual model and approach to measuring serious illness communication and its impact. J Palliat Med. 2018;21(S2):S17-S27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Henselmans I, van Laarhoven HWM, van Maarschalkerweerd P, et al. Effect of a skills training for oncologists and a patient communication aid on shared decision making about palliative systemic treatment: a randomized clinical trial. Oncologist. 2020;25(3):e578-e588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Patel S, Pelletier-Bui A, Smith S, et al. Curricula for empathy and compassion training in medical education: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2019;14(8):e0221412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wasp GT, Kaur-Gill S, Anderson EC, et al. Evaluating physician emotion regulation in serious illness conversations using multimodal assessment. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2023;66(4):351-360.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lane AS, Roberts C. Contextualised reflective competence: a new learning model promoting reflective practice for clinical training. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22(1):71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Street RL J, Makoul G, Arora NK, Epstein RM. How does communication heal? Pathways linking clinician-patient communication to health outcomes. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;74(3):295-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Boissy A, Windover AK, Bokar D, et al. Communication skills training for physicians improves patient satisfaction. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(7):755-761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hall JA, Schwartz R, Duong F, et al. What is clinical empathy? Perspectives of community members, university students, cancer patients, and physicians. Patient Educ Couns. 2021;104(5):1237-1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Elliott AM, Alexander SC, Mescher CA, Mohan D, Barnato AE. Differences in physicians’ verbal and nonverbal communication with black and white patients at the end of life. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;51(1):1-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lai AT, Abdullah N. Conducting goals of care conversations: lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic. J Palliat Care. 2024;39(1):13-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Giannitrapani K, Garcia R, Teuteberg W, Brown-Johnson C. Implementing an interdisciplinary team-based serious illness care program (SICP) in Stanford healthcare (QI112). J Pain Symptom Manage. 2023;65(5):e627-e628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sanders JJ, Dubey M, Hall JA, Catzen HZ, Blanch-Hartigan D, Schwartz R. What is empathy? Oncology patient perspectives on empathic clinician behaviors. Cancer. 2021;127(22):4258-4265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-pal-10.1177_08258597241245022 for Core Competencies for Serious Illness Conversations: An Integrative Systematic Review by Susanna Pusa, Rebecca Baxter, Sofia Andersson and Erik K. Fromme, Joanna Paladino, Anna Sandgren in Journal of Palliative Care