Abstract

Hispanic men have the highest prevalence of obesity relative to other racial and ethnic subgroups; however, this population is consistently underrepresented in weight management interventions. This systematic review aims to provide an overview of behavioral weight management interventions adapted for Hispanic men and describe their tailoring strategies and efficacy. Six online databases were selected for their abundant collection of high-quality, peer-reviewed literature and searched for studies which evaluated and reported weight outcomes for a cohort of adult (>18 years) Hispanic men. Of 6,508 unique publications screened, 12 interventions met inclusion criteria, the majority of which were published in the past 10 years. Only one study regarding an intervention tailored for Hispanic men was a randomized controlled trial adequately powered to assess a weight-based outcome; the remaining assessed feasibility or utilized quasi-experimental methods. Intervention characteristics and tailoring strategies varied considerably, but content was most frequently based on the Diabetes Prevention Program. Tailoring strategies commonly focused on improving linguistic access and incorporating social or family support. Follow-up varied from 1 month to 30 months and mean change in weight, the most common outcome, ranged from 0.6 to −6.3 kg. Our findings reveal a need for more fully powered randomized controlled trials evaluating the efficacy of interventions systematically tailored specifically for Hispanic men. Although the majority were not fully powered, these interventions showed some efficacy among their small cohorts for short-term weight loss. Future directions include exploring how to tailor goals, concepts, and metaphors included in interventions and comparing individual to group delivery settings.

Keywords: Hispanic, Latino, weight, diabetes, lifestyle

Introduction

The prevalence of overweightness and obesity in Hispanic men—79% and 40%, respectively—is among the highest compared to men of other racial and ethnic subgroups in the United States (Pagoto et al., 2012; Valdez & Garcia, 2021). By extension, the prevalence of obesity-related comorbidities such as type II diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), and dyslipidemia is higher among Hispanic men compared to non-Hispanic white men and non-Hispanic Black men (Alemán et al., 2023). Structural and social factors, as well as chronic stress, predispose Hispanic men to obesogenic risk factors, including poor diets and physical inactivity (Velasco-Mondragon et al., 2016). Notably, Hispanics who were born in the United States or spent long periods of their life in the United States have the highest prevalence of obesity compared to those who were foreign-born or spent less time living in the United States (Carmen et al., 2015). It has been hypothesized that this is due to the obesogenic environment of the United States. Of pertinence to addressing these risks, prior research has demonstrated that Hispanic men also express significantly less weight-related concern than other populations (Pagoto et al., 2012; Valdez & Garcia, 2021).

The Hispanic population remains the largest and fastest growing demographic in the United States, accounting for 62.1 million people censused in 2020— a growth of 23% in one decade (Jones et al., 2022; Passel et al., 2022). Despite the growing burden of obesity among Hispanic men, there is a dearth of research assessing the unique health experiences of Hispanic men in relation to weight management (Ghazal Read & Borelli Smith, 2018). Hispanic men remain significantly underrepresented in published weight loss trials and there is a lack of knowledge regarding effective obesity management for this population (Garcia et al., 2017; Pagoto et al., 2012). As such, there is an urgent need to identify the behavioral interventions that have focused on weight management specifically among Hispanic men.

The relationship between social determinants of health, behavioral risk factors, and obesity is fundamental to the development of successful weight loss interventions among Hispanics. As such, behavioral weight loss interventions are often culturally tailored to overcome structural and social obstacles (Perez et al., 2013). For example, a recently published systematic review analyzed the efficacy of culturally adapted weight loss interventions in Latina women in the United States; the most common strategies employed by reviewed studies included recruiting bilingual and bicultural research staff, delivering interventions in Spanish, referencing traditional Hispanic foods, incorporating Latin dancing, and including family members (Morrill et al., 2021). Among fifteen studies that were included, only eight led to significant improvements in body mass index (BMI) or weight and the majority of included studies were limited in duration and feasibility (Morrill et al., 2021). Because modest weight loss improves cardiovascular disease outcomes, glycemic control, blood pressure, and dyslipidemia, further development of these interventions is essential (Magkos et al., 2016; Morrill et al., 2021; Wing et al., 2011). Despite their unique gender and cultural needs, to our knowledge, a review of culturally adapted behavioral weight loss interventions among Hispanic men does not yet exist.

The objective of this study was to provide an overview of behavioral weight management interventions tailored for Hispanic men and published to-date. Through a systematic review of the literature, we identified the various strategies used to tailor interventions for this population and described their efficacy in relation to weight reduction. Results can serve as a reference for the development and optimization of weight management interventions tailored for Hispanic men.

Methods

This methodology was prepared according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Statement and registered in advance with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) (registration number: CRD42022343322) (Page et al., 2021). This study was determined to be exempt from Institutional Review Board (IRB) oversight by the Weill Cornell Medicine IRB committee.

Study Population

We herein use the term “Hispanic” to classify persons of Mexican, Cuban, South or Central American, Puerto Rican, or other Spanish culture or origin, regardless of race, but recognize the continued evolution of terms used to denote self-identity in racial and ethnic groups. Our search aimed to acknowledge the diversity of existing terms, including Hispanic, Latino/a, Latinx and Latine. We recognize the heterogeneity of the Hispanic population in relation to several dimensions, including Hispanic origin; however, these descriptors were not included here given they were not reported in most interventions selected for review.

Search Strategy and Eligibility Criteria

We comprehensively searched the following databases for manuscripts published up until July 19, 2024: MEDLINE (Ovid), Embase (Ovid), CINAHL (EbscoHost), PsycINFO (EbscoHost), Cochrane Library (Wiley), and Scopus (Elsevier). These databases were selected as they are high-quality and have a broad collection of peer-reviewed manuscripts. Reference lists from extracted articles and from existing literature reviews were used. Only publications written in English were included. Supplementary Table 1 details the keys terms searched.

Inclusion criteria were: (1) Study sample includes Hispanic/Latino adult (>18-year-old) men living in the United States; (2) Evaluation of behavioral or lifestyle intervention with the goal of weight loss or weight gain prevention; (3) Outcomes measure the effectiveness of weight management or cultural tailoring. Studies that recruited both men and women or children were included if results for Hispanic men were reported individually. Those conducted on a special subset of the target population (e.g., only individuals with an existing health condition such as diabetes mellitus 2, cancer, or NAFLD) were not included. Interventions aiming to prevent chronic disease (i.e., diabetes mellitus 2) were included if weight reduction was a primary goal. Interventions that included a pharmacological or surgical component were not included. Supplementary Table 2 further delineates the inclusion and exclusion criteria used.

Study Selection and Data Extraction

Publications resulting from the search were uploaded by KP to Covidence, a reference and systematic review management software. Four reviewers used the predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria to screen the primary literature pool in two stages. First, a title and abstract screening was conducted. Manuscripts not eliminated in this phase then underwent a whole text screening to produce the final literature pool. At least two individuals reviewed each manuscript at both stages and made the decision of whether to include each manuscript. Disagreements were resolved by reaching a consensus at meetings including all four reviewers.

Manuscripts which met all inclusion criteria were reviewed during the data extraction phase. Basic information about each study, including author and publishing date, objectives, setting, study design and methodology, results, and participant characteristics were transferred to a data table. This data table was informed by previously published systematic reviews regarding weight loss interventions (Corona et al., 2016; Perez et al., 2013). The Ecological Validity Framework was used to systematically evaluate how interventions were tailored for Hispanic men. This framework, developed by Bernal and Saez-Santiago, outlines 7 dimensions of an intervention that can be modified to optimize cultural sensitivity: language, persons, metaphors, content, concepts, goals, methods, and context (Bernal & Sáez-Santiago, 2006). These dimensions are further described in Supplementary Table 3. Intervention methodology details which matched one of these tailoring strategies were included in the data table. Two members of the research team analyzed each manuscript and extracted data into a standardized table independently. Differences in the extracted data were reconciled by a third research team member to ensure fidelity of information provided. If there were multiple manuscripts associated with one intervention, such as a protocol published separately from results, these were all referenced when extracting data regarding a specific intervention.

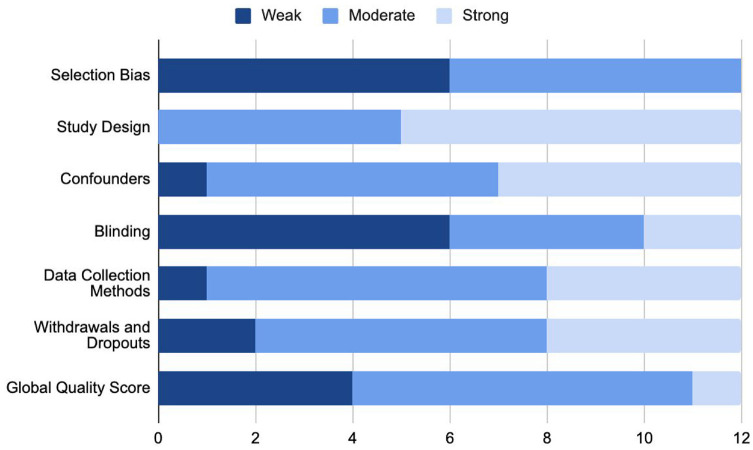

Quality Assessment

Publications included in this study underwent risk of bias and quality assessment using the Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies. This tool has been validated for quality assessment during systematic literature reviews and has excellent interrater agreement for global study rating (Armijo-Olivo et al., 2012; Thomas et al., 2004). Two members of the research team each conducted a quality assessment using the EPHPP tool, and their responses were reconciled by a third team member. Each study was assessed for selection bias, study design, confounders, blinding, data collection methods, withdrawals and dropouts, intervention integrity, and data analysis. Based on this assessment, each study was then given a global rating of strong, moderate, or weak that was agreed upon by all reviewers.

Data Synthesis

All collected data was synthesized using thematic analysis. Prominent themes among the included interventions were summarized in narrative format. Meta-analysis was not possible given heterogeneity in study design, target population, and results reported. In addition, most results (8/12) from these trials were not powered to detect statistical significance and as a result it was difficult to draw conclusions about their efficacy. Qualitative synthesis focused mainly on describing methods and tailoring strategies implemented to target the Hispanic male population.

Results

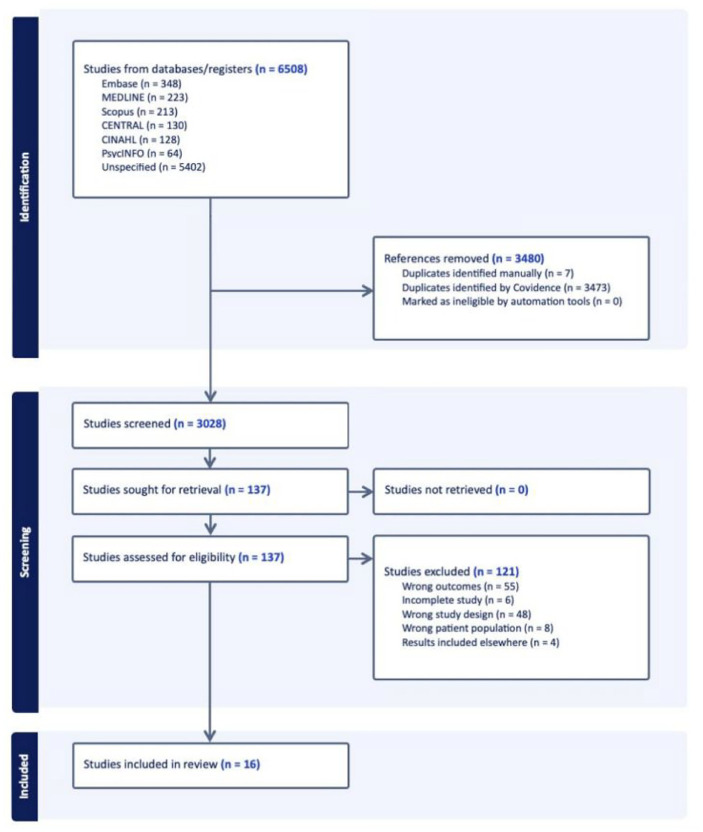

Of 6,508 publications initially screened, 137 full text articles were reviewed, of which 16 met final inclusion and exclusion criteria describing 12 unique interventions (Baltaci et al., 2022; Frediani et al., 2021; Garcia et al., 2019; Gary-Webb et al., 2018; Guerrero et al., 2023; Mitchell et al., 2015; O’Connor et al., 2020; Rocha-Goldberg et al., 2010; Rosas et al., 2015, 2022; Singh et al., 2020; West et al., 2008). Figure 1 presents a complete flow diagram for the reviewed articles.

Figure 1.

Literature Selection Flowchart

Note. A description of the literature screening and inclusion process, in Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flowchart style (Page et al., 2021).

Characteristics of Included Studies

All studies included were published after 2008, and the majority (n = 10) were published within the past 10 years (Baltaci et al., 2022; Frediani et al., 2021; Garcia et al., 2019; Gary-Webb et al., 2018; Guerrero et al., 2023; Mitchell et al., 2015; O’Connor et al., 2020; Rosas et al., 2015, 2022; Singh et al., 2020). Five studies focused specifically on Hispanic men, only one of which was a fully powered randomized controlled trial (Rosas et al., 2022). The remaining studies were either feasibility studies (Frediani et al., 2021; Garcia et al., 2019; Gary-Webb et al., 2018; Guerrero et al., 2023; Mitchell et al., 2015; O’Connor et al., 2020; Rocha-Goldberg et al., 2010) and/or used one-armed quasi-experimental designs (Frediani et al., 2021; Gary-Webb et al., 2018; Rocha-Goldberg et al., 2010; Singh et al., 2020) and/or obtained a sample beyond Hispanic men, including those identifying as other race/ethnicities (Gary-Webb et al., 2018; West et al., 2008), genders (Guerrero et al., 2023; Mitchell et al., 2015; Rocha-Goldberg et al., 2010; Rosas et al., 2015; Singh et al., 2020; West et al., 2008) or age-groups (Baltaci et al., 2022; O’Connor et al., 2020; Guerrero et al., 2023; Singh et al., 2020). Total number of Hispanic men included in an intervention arm across all studies was 535. Most studies required that participants have a BMI-based inclusion criteria (Frediani et al., 2021; Garcia et al., 2019; Gary-Webb et al., 2018; Mitchell et al., 2015; O’Connor et al., 2020; Rosas et al., 2015, 2022; West et al., 2008) often requiring a BMI of at least 25 kg/m2, but inclusion criteria were otherwise variable. Several studies sampled those with additional diabetes risk factors (Frediani et al., 2021; Gary-Webb et al., 2018; West et al., 2008), cardiovascular risk factors (Rocha-Goldberg et al., 2010; Rosas et al., 2015, 2022), or parents of children at risk for obesity (Baltaci et al., 2022; Guerrero et al., 2023; O’Connor et al., 2020; Singh et al., 2020). Four studies recruited patients who identified Spanish as their primary language (Baltaci et al., 2022; Mitchell et al., 2015; Rocha-Goldberg et al., 2010; Rosas et al., 2015). The included studies varied considerably in their setting. The majority primarily recruited participants from clinical sites (O’Connor et al., 2020; Rocha-Goldberg et al., 2010; Rosas et al., 2015, 2022; Singh et al., 2020; West et al., 2008) and the remaining studies recruited participants from community sites (Baltaci et al., 2022; Frediani et al., 2021; Garcia et al., 2019; Gary-Webb et al., 2018; Guerrero et al., 2023; Mitchell et al., 2015). Notably, one study aimed to sample farmworkers and recruited participants at their workplace (Mitchell et al., 2015). Sample sizes of Latino men varied substantially (7-186). Given the heterogeneity of these studies, and the dearth of adequately powered results, a meta-analysis was not possible. Table 1 describes study characteristics in further detail.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Included Studies

| Author (date published) | Study title | Study type | Intervention sample size a , population | Comparator sample size, comparator type | Primary study objective | Intervention setting, recruitment site | Study eligibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baltaci et al. (2022) | Padres Preparados, Jóvenes Saludables: intervention impact of a randomized controlled trial on Latino father and adolescent energy balance-related behaviors | Two-armed randomized controlled trial | N = 77, Target population consisted of Hispanic adult men and adolescents | N = 70, Delayed treatment-control group | To assess whether Latino father and adolescent energy balance related behaviors (diet and physical activity behaviors), father BMI, and adolescent BMI percentile differed from baseline to postintervention. | Intervention was held at Minneapolis and St. Paul metropolitan area, in community centers. Recruitment was conducted at local community service centers, churches, and through social media. | Inclusion criteria for fathers/caregivers: Identifying as Latino, speaking Spanish, and having meals at least three times a week with their adolescent. |

| Frediani et al. (2021) | Metabolic Changes After a 24-Week Soccer-Based Adaptation of the Diabetes Prevention Program in Hispanic Males: A One-Arm Pilot Clinical Trial | Pilot cohort trial | N = 25, Target population consisted of Hispanic adult men. | N/A | To determine feasibility, safety, and the cardiometabolic effects of a lifestyle intervention (adapted National Diabetes Prevention Program [NDPP] plus recreational soccer) for a cohort of Latino men. | Intervention was held at a local soccer field in Atlanta, GA. Recruitment was conducted from local Atlanta area Latino organizations using social media, emails, and fliers. | Inclusion Criteria: Hispanic/Latino men aged 35–55 years, BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2, elevated risk for diabetes (a score ≥9 in the Center for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] prediabetes risk calculator), not engaged in regular soccer practice or other physical activity or lifestyle intervention program in the last year, ability to read in English or Spanish and to provide informed consent. Exclusion Criteria: Reported type 2 diabetes diagnosis or medication, BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2, resting blood pressure ≥170/100 at screening, any mobility issues or contraindications for high intensity interval training (HIIT) physical activity program. |

| Garcia et al. (2018) | A gender- and culturally sensitive weight loss intervention for Hispanic males: The ANIMO randomized controlled trial pilot study protocol and recruitment methods | Pilot two-armed randomized controlled trial | N = 20, Target population consisted of Hispanic adult men. | N = 23, Waitlist control | Test the effects, feasibility, and acceptability of a gender- and culturally sensitive weight loss intervention among Hispanic men compared to a waitlist control group. | Intervention was conducted at The University of Arizona Collaboratory for Metabolic Disease Prevention and Treatment, in Tucson AZ. Site is in an underserved area of Tucson. Recruitment occurred at local swap meets/outdoor marketplaces in Tucson, through family and friend referral, and through social media. |

Inclusion Criteria: Self-identify as Hispanic, age 18–64 years, BMI 25–50 kg/m2, ability to provide informed consent and complete health risk assessment prior to participation, speak, read, and write English and/or Spanish. Exclusion Criteria: Uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, history of bariatric surgery, reported medical condition or treatment that could affect body weight or ability to engage in structured physical activity, congestive heart failure, angina, uncontrolled arrhythmia, resting systolic blood pressure of ≥150 mmHg or resting diastolic blood pressure of ≥100 mmHg, eating disorder, alcohol or substance abuse, psychological issues under current treatment, exercise on ≥3 days per week for ≥20 min per day over the past 3 months, weight loss of ≥5% or participation in a weight reduction diet program in the past 3 months, circumstances prohibiting attendance to all scheduled assessments. |

| Gary-Webb et al. (2018) | Translation of the National Diabetes Prevention Program to Engage Men in Disadvantaged Neighborhoods in New York City: A Description of Power Up for Health | Pilot, one-armed trial |

N = 8 Target population consisted of adult men of any race or ethnicity. |

N/A | To adapt the National Diabetes Prevention Program (NDPP) curriculum to be more relevant to men from disadvantaged neighborhoods and to implement a pilot study in recreation centers in disadvantaged neighborhoods. | Intervention was held in local New York City Parks recreation centers across New York City. These sites were in disadvantaged neighborhoods with predominantly low-income residents. Recruitment sites included local businesses and barbershops, senior centers, libraries, schools, community organizations, and residencies near recreation centers. |

Inclusion Criteria: 18 years or older, BMI of 25 kg/m2 or higher, not previously diagnosed with type 1 or type 2 diabetes. Must also have one of the following: A blood test results in the prediabetes range within the past year OR received a high-risk result (score of 5 or higher) on the Prediabetes Risk Test (ADA). |

| Guerrero et al. (2023) | A Hybrid Mobile Phone Feasibility Study Focusing on Latino Mothers, Fathers, and Grandmothers to Prevent Obesity in Preschoolers | Pilot, one-armed trial |

N = 34 Target population consisted of Hispanic men, women, and children. |

N/A | To pilot the feasibility of a mobile phone childhood obesity intervention for family caregivers of Latino preschool-aged children. | Recruitment occurred at Women, Infants, and Children and Early Education Centers in East Los Angeles. | Inclusion Criteria: Self-identified as an individual of Latino descent, had a 2- to 5-year-old child/grandchild, lived with or cared for the child/grandchild at least 20 h/week (where the relationship did not have to be biological), spoke Spanish or English, and had the ability and willingness to participate in the intervention and agreed to complete the baseline and post-baseline data collection protocols. Exclusion Criteria: Child had a medical condition related to overweight status such as Prader-Willi Syndrome, was taking weight loss medication, or was concurrently participating in a weight loss program. |

| Mitchell et al. (2015) | Pasos Saludables: A Pilot Randomized Intervention Study to Reduce Obesity in an Immigrant Farmworker Population | Pilot randomized controlled trial | Total recruited Hispanic men: N = 71 N of Hispanic men in intervention group unspecified Target population consisted of Hispanic men and women. |

N of Hispanic men unspecified Waitlist control |

Evaluate the efficacy of a workplace-based diet and physical activity intervention among a Latino farmworker population, evaluated as a reduction of measures of obesity and blood glucose, behavioral changes, and participant satisfaction. | Intervention was delivered at farm sponsored clinic sites. Recruitment occurred at two workplace locations of a California berry grower in Oxnard and Watsonville. |

Inclusion Criteria: Current farmworker employed by the grower with which study staff was collaborating, age 18 – 60 years, BMI 20 - 38 kg/m2, intention to remain in area for 6 months, willingness to attend 10 weekly sessions, ability to speak and read Spanish at a basic level, enrolment in medical insurance. Exclusion Criteria: Diagnosis of diabetes, currently pregnant, breastfeeding, or trying to conceive, participating in therapeutic diets or taking medications that affect weight, any medical condition that limits activity, have a spouse/cohabitant enrolled in study. |

| O’Connor et al. (2020) | Feasibility of Targeting Hispanic Fathers and Children in an Obesity Intervention: Papas Saludables Ninos Saludables | Pilot, two-arm randomized controlled trial |

N = 14 Target population consisted of Hispanic adult male “father figures” and their child. |

N = 13 Waitlist control |

To test the feasibility of the culturally adapted Papás Saludables Ninos Saludables program and research protocol among low-income Hispanic children and fathers. | Intervention and recruitment were conducted at Texas Children’s Health Plan (TCHP) Center for Children and Women primary care clinics in Houston, TX. TCHP is a Medicaid and CHIP provider with majority of clinic patients identifying as Hispanic. |

Inclusion Criteria: Male “father-figure”, self-identified as Hispanic or Latino, of a 5 –11-year-old child, able to read or write in Spanish or English, BMI between 25 and 40 kg/m2. Exclusion Criteria: BMI over 40 kg/m2, did not pass the 2015 American College of Sports Medicine exercise participation health screening, a medical clearance deemed necessary and not provided, a disease affecting dietary intake, physical activity, cognitive functioning, or psychiatric functioning. |

| Rocha-Goldberg et al. (2010) | Hypertension Improvement Project (HIP) Latino: results of a pilot study of lifestyle intervention for lowering blood pressure in Latino adults | Pilot cohort trial |

N = 7 Target population consisted of Hispanic adult men and women. |

N/A | To assess the feasibility of a culturally tailored behavioral intervention aimed at improving hypertension-related health behaviors in Hispanic/Latino adults. | Intervention was conducted in Durham, NC, at the Lincoln Community Health Center (a federally funded primary care clinic serving many low-income Hispanics/Latinos) and El Centro Hispano (ECH) (a community organization for the local Hispanic/Latino population). Recruitment occurred through health care provider referral, as well as at Hispanic/Latino businesses, organizations, and health fairs. Printed media advertisements were placed in Spanish newspapers. |

Inclusion Criteria: Hispanic/Latino men and women, age 18 years or older, Spanish as their primary language, presence of prehypertension or hypertension (defined as BP 120/80 mmHg) or taking antihypertensive medication. Exclusion criteria: Pregnant or nursing, inability to attend the intervention sessions. |

| Rosas et al. (2015) | The Effectiveness of Two Community-Based Weight Loss Strategies among Obese, Low-Income US Latinos | Three-arm randomized controlled trial | Case Management (CM): N = 20 Case Management + Community Health Worker (CM + CHW): N = 19 Target population consisted of male and female Hispanic adults. |

N = 9 Offered modified CM intervention after follow-up period. |

Evaluate the effect of intensive lifestyle interventions for weight loss among Latino immigrants and determine whether community health care workers provide additional benefits. | Intervention and recruitment were conducted at the Fair Oaks Clinic in San Mateo County, CA, located in a neighborhood with a high prevalence of low-income Hispanic individuals. Home visits were also conducted for CM + CHW participants. | Inclusion Criteria: Spanish-speaking male and female patients using the Fair Oaks clinic and residing in the neighborhood, BMI 30–60 kg/m2 and one or more coronary heart disease risk factors. Exclusion Criteria: Unwilling to attempt weight loss, serious, unstable medical conditions or other circumstances that would inhibit engagement in the intervention or retention over the 2 years of follow-up (uncontrolled psychiatric disorders, advanced heart failure, uncontrolled substance abuse, pregnant, planned move, or refusal of home visits). |

| Rosas et al. (2022) | HOMBRE: A Trial Comparing 2 Weight Loss Approaches for Latino Men | Investigator-blinded randomized controlled trial |

N = 186 Target population included Hispanic adult men. |

N = 180 12-month self-directed lifestyle change program. |

Compare in-person to virtual intervention approaches for sustaining clinically significant weight loss (>5%) at 18 months among overweight or obese Latino men. | Intervention was delivered online and in person at family and internal medicine clinics in Northern California. Recruitment was conducted at these same clinic sites. |

Inclusion Criteria: Self-identified as Latino, BMI ≥27 kg/m2, 1 or more cardiometabolic risk factors. Exclusion Criteria: Severe psychiatric or medical comorbidities. |

| Singh et al. (2020) | Incorporating an Increase in Plant-Based Food Choices into a Model of Culturally Responsive Care for Hispanic/Latino Children and Adults Who Are Overweight/Obese | Cohort trial |

N = 13 Target population consisted of Hispanic male and female adults and children. |

N/A | To examine whether the Healthy Eating Lifestyle (HELP) intervention prevented an increase in adiposity levels in obese/overweight children and parents and to determine strengths, weaknesses, effectiveness, and opportunities for the HELP program through a stakeholder analysis of program staff. | Intervention was conducted at the Department of Family Medicine and Diabetes Education of Adventist Health White Memorial (AH-WMMC) Medical Center in the East LA catchment area. The primary method for recruitment was pediatric referral from the AH-WMMC service area. Other methods included flyers and advertisements in the AH-WMMC system, hospital magazines, and news outlets (television, paper). |

Inclusion Criteria: A parent of an obese/overweight child 5–12 years of age, no medical restrictions for both child and parent to participate in the HELP diet and physical activity intervention. No family members were excluded from participation. |

| West et al. (2008) | Weight loss of black, white, and Hispanic men and women in the Diabetes Prevention Program | Randomized controlled trial | Lifestyle intervention: N = 41 Metformin: N = 34 b Target population consisted of adult men and women of multiple racial and ethnic groups. |

N = 44 Standard lifestyle recommendations + placebo provided. |

Evaluate weight loss outcomes for African American, Hispanic, and white men and women in the lifestyle and metformin treatment arms of the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) by race-gender group to facilitate researchers translating similar interventions to minority populations, as well as to provide realistic weight loss expectations for clinicians. | Intervention delivered at 27 clinical centers, with specific intervention and recruitment settings varying by site. | Inclusion: BMI of ≥24 kg/m2, age ≥25 years, impaired glucose tolerance (plasma glucose concentration of 95–125 mg/dl in fasting state and 140–199 mg/dl 2 hours after a 75-g oral glucose load). |

Note. BMI = body mass index; NDPP = National Diabetes Prevention Program; CDC = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; HIIT = high intensity interval training; TCHP = Texas Children’s Health Plan; ECH = El Centro Hispano; CHW = community health worker; AH-WMMC = Adventist Health White Memorial Medial Center.

Reported sample sizes are for target populations consisting of Hispanic adult men specifically, unless otherwise noted. b Data not included in this analysis given our focus on behavioral interventions.

Characteristics of Included Interventions

The majority of interventions had intensive phases, lasting 1 to 12 months, followed by maintenance phases extending the intervention to a range of 2 months to 2 years (Baltaci et al., 2022; Frediani et al., 2021; Garcia et al., 2019; Guerrero et al., 2023; Rosas et al., 2015, 2022; Singh et al., 2020; West et al., 2008). The remaining interventions consisted of only a single phase and ranged from 6 to 16 weeks. Interventions most often consisted of weekly group sessions lasting 45 to 150 minutes. Notably, one study supplemented group sessions with individual sessions (Rosas et al., 2015), while two others consisted explicitly of individual sessions (Garcia et al., 2019; West et al., 2008).

Intervention content and structure was most often theoretically informed by the DPP (Frediani et al., 2021; Garcia et al., 2019; Gary-Webb et al., 2018; Rosas et al., 2015, 2022; West et al., 2008). Several interventions engaged participants in physical activity and/or cooking during the sessions. Some of the interventions had remarkably unique components, such as incorporating the DPP curriculum into twice weekly soccer matches (Frediani et al., 2021), encouraging Hispanic men to be change agents for their children (O’Connor et al., 2020; Singh et al., 2020), and coordinating community health worker home visits and photovoice activities in which pictures of participants’ food and physical activity were leveraged for goal setting and problem-solving (Rosas et al., 2015). Others incorporated supplementary mobile health educational materials (Garcia et al., 2018; Guerrero et al., 2023). Table 2 describes intervention characteristics in further detail.

Table 2.

Intervention Characteristics of Included Studies

| Author (publishing date) | Intervention format | Intervention goals/recommendations | Tailoring modalities (✓—included, X—not included) | Theoretical framework |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baltaci et al. (2022) | Intervention consisted of 2 months of 2.5 hour weekly group sessions. Educational content included food preparation, parenting skills, nutrition, and physical activity | Improve individual, social, physical, and environmental factors related to fathers’ and adolescents’ energy balance related behaviors (diet and physical activity behaviors) to prevent overweight and obesity among Latino adolescents. | Language - ✓ People - ✓ Metaphors - ✓ Content - ✓ Concepts - ✓ Goals—X Methods - ✓ Context - ✓ |

Program was based on social-cognitive theory. |

| Frediani et al. (2021) | Biweekly group soccer practices held over a 12-week period. Sessions were led by trained bilingual coaches and consisted of soccer-based physical activity drills and discussions of NDPP a health education modules. This was followed by a 12-week maintenance phase. | Lifestyle change program with the goal of diabetes prevention through dietary changes and physical activity. No specific benchmarks for improvement were set. | Language - ✓ People - ✓ Metaphors - ✓ Content - ✓ Concepts ✓ Goals—X Methods - ✓ Context—X |

NDPP a modules, delivered as they were originally designed. |

| Garcia et al. (2018) | Intensive phase consisted of 12 weeks of 30–45-min individual counseling sessions guided by a trained bilingual Hispanic male lifestyle coach. Participants also received tailored lesson materials modelled after the DPP

b

. Maintenance phase consisted of bi-weekly counseling phone calls for another 12-weeks |

Participants were prescribed a calorie and fat gram goal to reduce total energy intake to 1200–1800 calories per day dependent on their initial body weight. Participants were provided with culturally tailored meal plans and grocery lists to make small, practical dietary changes of ∼100 calories/meal each day. Weekly exercise goals were also set, with the duration increasing from 15 to 40 min, 5 days a week, over the course of the program. | Language - ✓ People - ✓ Metaphors - ✓ Content - ✓ Concepts - ✓ Goals - ✓ Methods - ✓ Context - ✓ |

Gender and culturally tailored program based on the DPP b . Lesson materials based on social-cognitive theory and problem-solving theory. Tailoring based on ecological validity framework (Bernal, Sáez-Santiago, 2006). |

| Gary-Webb et al. (2018) | 16-week intervention with weekly hour-long educational sessions based on the NDPP a . Curriculum was delivered in all-male group settings by trained lifestyle coaches. | Diabetes prevention through healthy eating and increased physical activity without specific benchmarks. | Language - ✓ People - ✓ Metaphors - ✓ Content - ✓ Concepts - ✓ Goals—X Methods - ✓ Context - ✓ |

NDPP a adapted for Black and/or Latino men from disadvantaged neighborhoods. |

| Guerrero et al. (2023) | Intervention consisted of 1 month of weekly 1-hour in-person group sessions, supplemented by 1 month of “booster” educational mobile content, to support parenting skills and promote evidence based and age-appropriate nutritional practices in either English or Spanish. | Promote healthy children by educating families about parenting behaviors, healthy diet, and physical activity recommendations. | Language - ✓ People - ✓ Metaphors—X Content - ✓ Concepts - ✓ Goals—X Methods - ✓ Context—X |

Program was based on social-cognitive and family-based theories and uses a group strategy to promote peer-to-peer learning, and observational and social support strategies to support behavioral changes. |

| Mitchell et al. (2015) | Intervention group participated in 90-minute sessions consisting of 20 minutes of moderate physical activity and an hour of education over 10 weekly sessions. Topics included hydration, healthy diet, measuring progress, mental health, physical activity, and sharing these lifestyle changes with others. Sessions were conducted at easily accessible work-sponsored clinic sites. | Five steps to live better specifies the following goals: (1) drink water; (2) eat fruits and vegetables; (3) measure (what you eat and your waist); (4) move; and (5) share (the message). Participants set their own individual goals to make lifestyle changes. | Language - ✓ People - ✓ Metaphors—X Content - ✓ Concepts –✓ Goals –✓ Methods - ✓ Context –✓ |

Program framework was based on the “Cinco Pasos para Vivir Mejor” (Five Steps to Live Better) campaign developed by the Mexican government (“Cinco pasos”, 2024). Program content was based on the “Your Heart, Your Life” program, created by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (“Your heart, your life”, 2024) |

| O’Connor et al. (2020) | Weekly 90-minute sessions held over 10 weeks. Programming consisted of a group session with fathers and children, separate break-out discussions for fathers and children (Dad’s Club and Kid’s Club), and a joint physical activity component (Sports Club) for fathers and children. | Weight loss and obesity prevention through increased physical activity and improved nutrition without specific benchmarks. Modeling of healthy behaviors for children. | Language - ✓ People - ✓ Metaphors—X Content - ✓ Concepts - ✓ Goals - ✓ Methods - ✓ Context - ✓ |

Adaptation of "Healthy Dads Healthy Kids" program, based on social-cognitive theory and Family Systems Theory (Morgan et al., 2014). |

| Rocha-Goldberg et al. (2010) | Intervention consisted of 6 weekly 90–120-minute education sessions, during which an interventionist helped participants set individualized personal goals and action plans for weight management. Every other session involved a recipe demonstration; on the alternate week a 20-minute facilitated moderate exercise session was conducted. | Patients developed individual goals for lifestyle change to manage weight. | Language - ✓ People - ✓ Metaphors—X Content - ✓ Concepts—X Goals - ✓ Methods - ✓ Context - ✓ |

Intervention was based on the PREMIER and HIP trials, which are informed by social-cognitive theory, transtheoretical states of change model, and motivational enhancement approaches (Appel et al., 2003; Dolor et al., 2009). |

| Rosas et al. (2015) | Case Management (CM) Arm: Participants paired with case managers for 2 years. Initial 12-month intensive phase consisted of 12 2-hour group sessions and four 30-minute individual sessions with case managers, subsequent 12-month maintenance phase consisted of 3 group sessions and 1 individual session. Case Management + Community Health care Worker (CM + CHW) Arm: Participants received the same case management interventions plus five community health care worker home visits during the initial 12-month intensive phase and two home visits during the subsequent 12-month maintenance phase. |

Lifestyle change program focused on nutrition and physical activity. Specific goals were individualized and set in collaboration with each participant. | Language - ✓ People - ✓ Metaphors—X Content –✓ Concepts –✓ Goals –✓ Methods –✓ Context –✓ |

DPP b , tailored based on the previous Heart to Heart trial, which employed social-cognitive theory and the transtheoretical model of behavior change (Ma et al., 2009). |

| Rosas et al. (2022) | Intervention groups participated in 12 weekly sessions during the intensive phase. They were given the option to participate in coach-facilitated group sessions using online video conferences, in-person coach-facilitated group sessions, or a self-directed curriculum. Coach involvement varied based on delivery modality, with the self-directed group having the least amount of coach involvement. Participants were encouraged to increase moderate-intensity physical activity, wear activity monitors and track diet. Education focused on understanding calories and fat intake, making healthy food choices, and addressing barriers to weight loss. Maintenance phase involved 8 months of biweekly to monthly contacts from coaches. Control group had access to 12 prerecorded videos of a similar program to be viewed independently. Only on request was coach support provided. |

To sustain clinically significant weight loss (>5% loss from baseline) at 18 months, and a minimum of 150 min/week of moderate-intensity physical activity. | Language - ✓ People - ✓ Metaphors—X Content - ✓ Concepts –✓ Goals—X Methods –✓ Context - ✓ |

A group-based adaptation of the DPP b based on social-cognitive theory, tailored by a Latino Patient Advisory board to the Latino population. |

| Singh et al. (2020) | 6-week intensive educational phase followed by a 3-month maintenance phase. Parent−child dyads completed this program together. Dietary education consisted of family cooking classes and supermarket tours centered on a four-tiered food guide to plant-based eating. Physical activity intervention consisted of pedometer goals and education. | Four-tiered food guide was referenced to set goals, with the highest tier involving eating whole plant foods with minimal processing. There were no strict vegetarian categories. The goal for each participant was to transition from one tier to the next through dietary changes. | Language - ✓ People - ✓ Metaphors—X Content - ✓ Concepts - ✓ Goals - ✓ Methods - ✓ Context - ✓ |

Intervention informed by the Curriculum for Culturally Responsive Health Care: The Step-by-Step Guide for Cultural Competence Training, and The National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities Research Framework (Alvidrez et al., 2019; Ring et al., 2008). Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) cultural competence training domains were used to tailor the delivery of this intervention (Frediani et al., 2021). |

| West et al. (2008) | Control: Standard lifestyle recommendations were provided at annual individual sessions. Lifestyle Intervention: Program consisted of a 16-session core curriculum focused on promoting healthy dietary and physical activity changes. Curriculum was delivered by case managers in individual sessions over 6 months, supplemented by group sessions. The 24-month maintenance period consisted of bimonthly individual sessions. |

Achieve and maintain a weight reduction of at least 7% of initial body weight through healthy diet and physical activity, and to maintain a level of physical activity of at least 150 min/week through moderate-intensity activities. | Language - ✓ People - ✓ Metaphors—X Content - ✓ Concepts—X Goals—X Methods - ✓ Context - ✓ |

DPP b intervention, delivered as originally designed. |

Note. NDPP = National Diabetes Prevention Program; HIP = hypertension improvement program; CHW = community health worker; AH-WMMC = Adventist Health White Memorial Medial Center.

National Diabetes Prevention Program (Albright & Gregg, 2013). b Diabetes Prevention Program (“The Diabetes Prevention Program”, 1999).

Use of Tailoring Strategies

Tailoring strategy use is summarized in Table 3 and described below.

Table 3.

Cultural Tailoring Strategies of Included Studies

| Author (publishing date) | Language | People | Metaphors | Content | Concepts | Goals | Methods | Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baltaci et al. (2022) | Program offered in English and Spanish | Sessions were led by trained bilingual facilitators, one male and one female, who were parents themselves. | Program was held in a familiar community center setting | Surveys were provided to fathers in Spanish. | Education for parents focused on parenting skills related to parent-child interactions and food- and activity-related parenting practices. Education for youth focused on building strong family communication and connections. Parent and youth joint activities involved explanations of basic nutrition and physical activity concepts and hands-on practice/discussion based on their experiences. | Flyers, announcements, and social media were used to recruit participants at local community service centers and churches. The format, length, session structure, and content of the Padres program was designed based on Latino fathers’ preferences communicated in father advisory board meetings and focus group discussions. Additionally, two bilingual community educators were involved in curriculum development. During the intervention sessions, participants prepared culturally tailored, simple recipes. Mothers were also encouraged to attend sessions and complete data collection. |

Group physical activities were those that could be done easily indoors or outdoors regardless of time and resource constraints. | |

| Frediani et al. (2021) | Program offered in English and Spanish. | Coaches were all English and Spanish speaking. | Intervention delivered at local soccer fields in the community. | All participant communication, from recruitment to intervention, was tailored to be culturally and regionally responsive. A closed and encrypted chat (WhatsApp platform) was created for each cohort and for the full group to facilitate peer support, communication, and session attendance. | "Football is Medicine”, the idea that football can be used as therapy and for the prevention and treatment of type 2 diabetes cardiovascular disease, severe obesity, and other pathologies. | Participants were recruited from local Atlanta area Latino organizations using online (social media, websites, email listservs) and print (fliers) advertisement methods. Soccer was used to facilitate physical activity at each practice. Coaches provided attendance encouragement through WhatsApp, and participants also used it to post encouraging messages and provide support (pictures of their dietary choices, activities outside of soccer sessions). Participants were encouraged to bring family and/or friends as spectators for additional social support. Coach assignment and session scheduling was tailored to the group’s preference based on field availability and location convenience. | ||

| Garcia et al. (2018) | Program offered in English and Spanish. | English and Spanish-speaking Hispanic male coaches were from the local community and had a broad understanding of the complex sociocultural and socioeconomic barriers to weight management that participants faced. | The intervention was delivered in a space well-recognized and accessible to the study population. The research team ensured that visible décor and any passive information hanging on the walls was culturally and linguistically appropriate. | All participant communication was tailored to be culturally and regionally responsive. Communication was centralized around personalismo, simpatia, and respeto. Participants were reminded of individual appointments and other study activities via their preferred contact method (telephone, email, text messaging). | Risk-based communication was used when providing feedback on cardiometabolic lab values, because fear-appeal communication was identified as a motivator for behavior change. Participants received tailored lesson materials focused on behavioral strategies for adopting and maintaining healthy eating and physical activity behaviors. | Interventionists ensured that dietary changes considered cultural food choice preferences so that behavior changes were attainable. For instance, instead of replacing tortillas with an alternative food or eliminating it all together, portion control was suggested (substitution of corn tortillas for flour tortillas every other meal). Gender- and culturally bound norms related to strenuous work schedules and their impact on health were discussed at counseling sessions to encourage participants to achieve physical activity recommendations. | Recruitment was conducted in outdoor marketplaces (swap meets) frequented by target population. Intervention provided participants and their families with a free 3-month gym membership to facilitate physical activity. Family social support was identified as an important intervention component, thus spouses/significant others were invited to attend specific counseling sessions. Program addressed specific eating behavior issues including: access to healthy food, cost, meal preparation, portion control, and family/social events. Additional issues related to physical activity were addressed including: neighborhood safety, childcare to allow time for physical activity, and acceptance from other family members. Provided strategies to overcome these barriers (a list of neighborhood resources for physical activity). | Held discussions related to gender role strains (the role of the man in the household) during intervention sessions. In addition, issues related to access of healthy foods or safe spaces for physical activity were discussed within the context of socio-economic status. |

| Gary-Webb et al. (2018) | Program offered in English and Spanish. | Trained male lifestyle coaches who were Black and/or Latino led the program at each site, 1 was a bilingual community health specialist and held the curriculum in Spanish. Coaches modelled weight loss efforts and provided professional expertise in health education or fitness training. 3/4 coaches had personal experience with diabetes or weight issues. | Program was held in a recreational center in a familiar community setting. | Curricular materials and recruitment flyers were all available in English and Spanish. Text and phone were used to send participants reminders. Content featured sports quotes and references. Examples provided of healthy and unhealthy foods were those perceived as more commonly eaten by men, such as chips rather than ice cream. | Coaches explained healthy eating by using familiar food examples. Participants were taught to ask questions and learn to advocate for themselves (for example, asking local stores for healthier food options), given that some men felt that they must already know everything and cannot ask. | Participants and coaches were all male, which participants reported helped them feel that they didn’t have to act as "macho". Participants were provided with paper trackers for diet and exercise, a calorie counter book, pedometers, water bottles, and measuring utensils. After 4 sessions, participants were given a 6-month NYC Parks membership with access to the city’s recreation centers. Additionally, if participants had difficulties attending sessions due to transportation costs, they were given a transit pass. Study worked with the New York City Housing Authority, the administrator of NYC public housing, to mail flyers to residents living near each of the recreation centers. Study hired 2 male outreach workers from the targeted neighborhoods to distribute flyers to barbershops and other local businesses. They also presented at community board meetings, senior centers, schools, libraries, and community-based organizations. | Sites were chosen to be in areas accessible to target population. Sites already had accessible gym equipment, swimming pools (at some locations), fitness classes, and health-related programming. Additionally, the cost of membership to the recreation centers was reasonably affordable. Program included content on male-specific issues such as the connection between diabetes and erectile dysfunction. | |

| Guerrero et al. (2023) | Program offered in English and Spanish | Sessions led by Women, Infant, and Children health educators who were experienced and trusted health educators in their communities | Caregiver surveys were available in English and Spanish. Media educational content was also provided in English and Spanish on the Chorus mobile phone platform. Chorus is a web-based application, allowing users to access content without having to download an application to their phone. | This program was adapted to emphasize the role of collectivism and familism among Latino families. | Recruitment was conducted at Women, Infants, and Children and Early Childhood Education (ECE) Centers using research flyers. Program development was informed by qualitative data collected from Latino mothers, fathers, and grandparents of 2- to 5-year old children to explore the challenges and barriers to support healthy dietary and physical activity behaviors. Caregivers who were fathers were only asked to complete the first 2 weeks of the in-person sessions that were facilitated by a male WIC staff member, instead of all four weeks. Additionally, evening and Saturday sessions were held to provide more flexibility and encourage engagement from fathers, whose participation was limited by work schedules. | |||

| Mitchell et al. (2015) | Program offered in English and Spanish. | Intervention and recruitment conducted by English and Spanish-speaking Latina Promotoras. | A native Mexican specialist who is an expert in adapting materials to lower literacy groups developed culturally and linguistically appropriate materials. The content of the sessions was adapted from the “Your Heart, Your Life” program, created to improve heart health and reduce obesity among Latinos. This program was designed to be more accessible to lower literacy groups by not relying on written material. | The concept of "Cinco Pasos para Vivir Mejor" was referenced in this intervention. “Cinco Pasos para Vivir Mejor” is a social media campaign launched by the Mexican Government. The five steps are as follows: (1) drink water; (2) eat fruits and vegetables; (3) measure (what you eat and your waist); (4) move; and (5) share (the message) | Participants set individualized goals for lifestyle change. | Recruitment was conducted in collaboration with the farms where participants worked. During the intervention, high-impact moves were avoided, and music was always included to inspire movement. The actual exercises were kept simple and did not require special equipment, so participants could practice similar sessions at home. Participants were encouraged to make each concept relevant in their daily life by making weekly promises to improve lifestyle and tp collaborate as a group in order to help overcome boundaries to their promises. Participants were encouraged to bring relatives, friends, and children (free childcare provided) to the sessions. | Sessions conducted at easily accessible work-sponsored clinic sites. | |

| O’Connor et al. (2020) | Program offered in English and Spanish. | Program was delivered by three trained facilitators who were Spanish and English speaking. | The reading level of all program material was lowered. Questionnaires were made available in English and Spanish. Social media reminders were sent by Facebook posts. Each family was provided a set of culturally adapted game cards with a bag of sports equipment to encourage practicing sports skills at home. | Curriculum was enhanced with cultural values such as familismo (familism), respeto (respect), and colectivismo (collectivism). Foods, games, and physical activities were modified to those commonly known to Hispanic families (Rough and Tumble play in the context of respeto). | The main goal focused on health promotion for the family, teaching fathers and children how to be healthier and more active and providing an opportunity for fathers to spend time with their children. Encouraged fathers to be healthy role models for their family regarding eating and physical activity and taught fathers authoritative parenting to encourage healthy behaviors in their children. At home health goals/challenges such as trying a new fruit or vegetable with their children and engaging in rough and tumble play were reported by participants to be effective. | “Dad’s Club” all-male participant group met weekly. Mothers were engaged by inviting them to a Facebook Group for the program and sending them weekly videos of that week’s content by Facebook, text, or email. Program included a booster session midway through to reinforce concepts. Resources provided included: Cookbook of Healthy Hispanic Recipes, pedometers for step tracking/family challenges, MyFitnessPal for self-monitoring physical activity and dietary intake. The program was offered on Sunday afternoon, the time preferred by fathers due to busy work schedules, at the child’s primary care pediatric clinic. | Addressed barriers for participation and engagement for Hispanic fathers; discussed difficulties faced raising children in a different culture than your own. Due to concerns about unsafe neighborhoods and lack of public parks, indoor games and exercises were offered as an option. | |

| Rocha-Goldberg et al. (2010) | Program offered in English and Spanish. | Spanish-speaking Hispanic/Latino research assistants conducted participant recruitment and screening interviews. Interventionist was also Latina. | Traditional Hispanic/Latino food names from each country in Latin America were incorporated so that intervention materials could be used with people from different Latino countries of origin. All study materials were translated into Spanish. | Participants developed individually tailored goals for lifestyle change. | Recruitment was conducted during Hispanic/Latino events in the community, such as Hispanic/Latino Health Fairs. Most recruitment was conducted at a federally funded primary care clinic serving a large population of low-income Hispanics/Latinos and a local Hispanic/Latino community organization. To facilitate recruitment and ensure cultural appropriateness of recruitment efforts, investigators worked closely with these organizations. Recipes were adapted to those commonly used by Hispanics/Latinos, and physical activities were included that were traditional within the Hispanic/Latino culture, such as dancing. |

Latina interventionist was familiar with the cultural context of the participants (e.g., typical roles of men and women in Hispanic/Latino families). | ||

| Rosas et al. (2015) | Program offered in English and Spanish | Interventionists were all English and Spanish-speaking and bicultural. These included case managers, community health workers, and members of the local Fair Oaks community. | Individual steps from "virtual walking groups" were converted to collective miles travelled and used in a multi-media virtual travel adventure “Steps through the Americas” that presents health topics within the context of destinations in North and South America. | CHW approaches integrated with CM activities included building broad skills for navigating an obesogenic environment, fostering family support, enhancing participant success in food negotiations, mapping out neighborhood walking routes, and engaging participants in a modified photovoice activity. | Specific goals were individualized and tailored for each participant. | Individuals were identified for screening through outreach in the clinic and community, which is low-income and majority Latino. Take-home items were provided including pedometers, exercise compact disks, and free weights. Group setting with other community members from similar backgrounds facilitated the development of social support networks. Participants also developed collective efficacy and social support through “virtual walking groups.” Additionally, family and friends were included in session activities. Motivational interviewing, positive feedback, self-reflection, and flexible scheduling techniques were used. | CHW helped participants overcome environmental and social barriers such as acculturation, immigration status, food insecurity, limited opportunities for physical activity, and poverty. To maintain focus on obesity reduction, interventionists followed a protocol to refer patients to other health care services (primary care, mental health, diabetes clinic) and community resources (health insurance programs, immigration assistance) for issues not directly related to weight loss. | |

| Rosas et al. (2022) | Program offered in English and Spanish. | Intervention conducted by English and Spanish-speaking bicultural coaches. | Spanish subtitles were provided for pre-recorded videos. | Each video lesson featured a coach-facilitated group session with actors representing diverse demographic groups, including men and women. The MyPlate Visual was used to communicate food choices. | Participants could choose from three options for engaging with the intervention (online, in-person, or self-guided) using a structured handout that guided them through important decision domains including preferred level of coach and peer support, comfort with technology, and lifestyle factors (e.g., work, family schedule). Encouraged participants to discuss decision with a small group of participants, as well as identify challenges and solutions to intervention adherence. Participants were encouraged to watch pre-recorded videos with family for self-directed option. For the in-person option, they were encouraged to attend specific sessions with family given cultural importance of family support. Study provided digital weight scale, a wearable activity tracker, and the MyFitnessPal application for dietary tracking. This application was chosen because the Latino Patient Advisory Board determined it had high acceptability based on the language, ease of entering cultural foods, social networking, and availability on phone and computer. | Primary care setting for intervention delivery was chosen because a primary motivation for weight loss among men appeared to be reducing chronic disease risk factors and avoiding adverse health outcomes. Implementation in primary care offers the benefit of leveraging primary care provider support for adoption and maintenance of behavior change. | ||

| Singh et al. (2020) | Program offered in English and Spanish. | Interventionists were all English and Spanish speaking and Hispanic/Latino. Interactive cooking classes were conducted by expert bilingual staff (three registered dieticians/certified diabetes educators) from the local community. | All the program educational materials were developed for the targeted community with language considerations in mind. | Curriculum draws from theory-driven frameworks built upon cultural awareness, knowledge, skills, encounters, and proficiency. The “Familismo” effect in the Hispanic/Latino cultural context was considered when designing this family-based, culturally tailored intervention. | Program goal was individualized. Each participant was encouraged to transition from one tier of a plant-based food pyramid to the next. No strict vegetarian categories were required. | Recruitment flyers and advertisements in the AH-WMMC system, hospital magazine, and news media were provided in English and Spanish. English and Spanish language television was also used to broadcast recruitment materials. The dietary intervention consisted of cooking instruction and supermarket tours to implement a four-tiered food guide to plant-based eating. All cooking demonstrations were designed with the target population in mind; recipes were carefully aligned with the traditional fare of this community. | The educators took special care to ensure that the recipes taught in the program included only those ingredients that were easily accessible in the local neighborhood markets, making the program recommendations easily attainable. | |

| West et al. (2008) | Program offered in English and Spanish. | Case managers were often chosen from the same ethnic group as participants. | All study materials were translated into Spanish. Reference materials (e.g., fat and calories in commonly eaten foods) and lesson handouts included information about the types of foods and cooking methods used by various ethnic groups. | Individual case managers or “lifestyle coaches” allowed tailoring of intervention activities to the ethnically diverse population and those with low literacy. Individualization was provided through a “toolbox” of adherence strategies. Approximately $100 per participant per year was available for implementing toolbox strategies. For example, participants having trouble achieving or maintaining the activity goal might be loaned or given an aerobic dance tape, enrolled in a community exercise class or a cardiac rehabilitation program, or seen individually by an exercise trainer to begin a tailored exercise regimen. Similarly, participants might be given a cookbook, a scale, grocery store vouchers, or portion-controlled foods. | Lifestyle coaches were encouraged to work with each participant individually to identify their specific barriers to weight loss and possible solutions to these barriers, including addressing financial barriers with a $100 toolbox stipend. |

Note. ECE = early childhood education; CHW = community health worker; AH-WMMC = Adventist Health White Memorial Medial Center.

Language

All interventions provided an option for engagement in Spanish. One study dedicated a single site where the intervention was held entirely in Spanish (Frediani et al., 2021), whereas other studies paired bilingual interventionists with individual subjects based on their language needs.

People

Nearly all the interventions were led by bilingual personnel who could deliver the content in the participant’s language of choice (Baltaci et al., 2022; Frediani et al., 2021; Garcia et al., 2019; Gary-Webb et al., 2018; Guerrero et al., 2023; Mitchell et al., 2015; O’Connor et al., 2020; Rocha-Goldberg et al., 2010; Rosas et al., 2015, 2022; Singh et al., 2020) and explicitly identified as bicultural or Latino/a (Garcia et al., 2019; Gary-Webb et al., 2018; Mitchell et al., 2015; Rocha-Goldberg et al., 2010; Rosas et al., 2015, 2022; Singh et al., 2020; West et al., 2008). Notably, only four programs were led specifically by bilingual men (Baltaci et al., 2022; Frediani et al., 2021; Garcia et al., 2019; Gary-Webb et al., 2018).

Metaphors

Three interventions were delivered in familiar community settings, such as local parks and recreation centers or soccer fields (Baltaci et al., 2022; Frediani et al., 2021; Garcia et al., 2019; Gary-Webb et al., 2018). One study ensured that decor and information posted on the walls of their intervention site were linguistically and culturally appropriate (Garcia et al., 2019).

Content

Six interventions included educational materials described as culturally and linguistically adapted (Frediani et al., 2021; Garcia et al., 2019; Guerrero et al., 2023; Mitchell et al., 2015; O’Connor et al., 2020; Rocha-Goldberg et al., 2010; Singh et al., 2020; West et al., 2008), and some sent culturally tailored messages directly to participants through phone or social media (Frediani et al., 2021; Garcia et al., 2019; Gary-Webb et al., 2018; O’Connor et al., 2020); details about how content was culturally adapted was often not reported. Two studies made use of mobile health materials, one of which was web-based due to evidence that minority populations are high users of mobile phones but are less likely to be receptive to downloading applications (Garcia et al., 2018; Guerrero et al., 2023). One study adapted the reading level of their materials (O’Connor et al., 2020), while others made use of educational materials requiring no reading, such as the My Plate Visual, to communicate concepts to participants with limited literacy (Mitchell et al., 2015; Rosas et al., 2022).

Concepts

Several interventions drew upon the concept of familismo (familism), encouraging engagement or support from participant’s family members (Baltaci et al., 2022; Frediani et al., 2021; Garcia et al., 2019; Guerrero et al., 2023; Mitchell et al., 2015; O’Connor et al., 2020; Rosas et al., 2015, 2022; Singh et al., 2020). One study incorporated concepts of respeto (respect), and colectivismo (collectivism) into lessons, encouraging reciprocal reinforcement between fathers and sons (O’Connor et al., 2020). Another centered communication around cultural concepts of personalismo (personalism), simpatia (kindness), and respeto (respect) (Garcia et al., 2019), while a third study used the concept “Football is Medicine” to tie a culturally significant sport into health education (Frediani et al., 2021).

Goals

Several interventions developed made use of physical activity and nutrition goals. One study set goals related to fatherhood and activities with children (O’Connor et al., 2020). Another set goals related to portion control and ingredient substitution rather than elimination of culturally significant foods (Garcia et al., 2019). A number of studies had participants set their own individualized goals (Mitchell et al., 2015; O’Connor et al., 2020; Rocha-Goldberg et al., 2010; Singh et al., 2020).

Methods

Methodological adaptations were leveraged in all studies. To appeal to the target population, half of the interventions featured all-male participant groups (Frediani et al., 2021; Garcia et al., 2019; Gary-Webb et al., 2018; O’Connor et al., 2020; Rosas et al., 2022), and one aimed to provide flexibility by allowing participants to complete the interventions through synchronized video conferences or asynchronous prerecorded videos (Rosas et al., 2022). To facilitate social support, one study delivered the DPP curriculum between group-soccer activities and used WhatsApp group messaging (Frediani et al., 2021). Other methods included local supermarket tours and mapping out neighborhood walking routes for “virtual walking groups” (Singh et al., 2020). Three programs adapted recipes to feature ingredients familiar to Hispanic populations (Baltaci et al., 2022; Rocha-Goldberg et al., 2010; Singh et al., 2020). Resources were frequently utilized, such as providing a 6-month park membership with access to all of New York City (NYC) recreation centers, water bottles, calorie tracker books, and measuring utensils (Garcia et al., 2019). Families from one study were given a set of culturally adapted game cards with a bag of sports equipment to encourage family bonding and physical activity at home (O’Connor et al., 2020).

Recruitment strategies were frequently tailored. One study recruited participants at Hispanic Health Fairs (Rocha-Goldberg et al., 2010). Another recruited participants from outdoor marketplaces (swap meets) frequented by the local Hispanic population (Garcia et al., 2019). A third had male outreach workers distribute flyers to barbershops and other community-based organizations frequented by Hispanic men and collaborated with the NYC Housing Authority to mail flyers to eligible residents (Gary-Webb et al., 2018).

Context

Ten interventions aimed to address issues related to the larger context in which these studies occurred, such as those related to access or barriers to participation (Baltaci et al., 2022; Garcia et al., 2019; Gary-Webb et al., 2018; Mitchell et al., 2015; O’Connor et al., 2020; Rocha-Goldberg et al., 2010; Rosas et al., 2015, 2022; Singh et al., 2020; West et al., 2008). One study considered the financial burden of participating in exercise programs and provided transit passes to cover transportation costs (Gary-Webb et al., 2018). Another referred participants to health care services and community resources such as health insurance programs and immigration assistance programs, as needed (Rosas et al., 2015). A third provided a $100 budget per participant to overcome individual barriers to participation (West et al., 2008). Several studies addressed the context of gender or family roles during intervention sessions by including content on male-specific health issues, addressing the relationship between gender role strain and weight loss efforts, or holding discussions on fatherhood and the difficulties of raising children in a different culture than their own (Baltaci et al., 2022; Garcia et al., 2019; Gary-Webb et al., 2018; O’Connor et al., 2020).

Weight Outcomes

Follow-up varied considerably among studies from1 month to 30 months. Mean change in weight was the most common outcome, ranging from 0.6 kg (at 14 weeks, no p value nor confidence interval [CI] provided) to −6.3 kg (at 12 weeks; 95% CI −8.1, −4.4; p < .01) (Garcia et al., 2019; Mitchell et al., 2015). Mean change in waist circumference was available for several studies, ranging from −0.2 cm (at 14 weeks, no p value nor CI provided) to −6.6 cm (at 24 weeks; 95% CI −8.0, −0.9) (Frediani et al., 2021; Mitchell et al., 2015). Mean change in BMI was assessed in a number of studies, ranging from 0.7 kg/m2 (at 24 months; 95% CI −1.4, 0) to −1.4 kg/m2 (at 24 weeks; 95% CI −1.8, −0.9) (Frediani et al., 2021; Rosas et al., 2015). Only one study assessed the proportion of participants that reached a 5% weight loss goal, finding that 27.4% reached that goal at 18 months, compared to 20.6% in control (p = .13) (Rosas et al., 2022). Notably, this was the only randomized controlled trial adequately powered to detect a statistical difference in the primary outcome of interest among Hispanic men. Most studies were not adequately powered to detect between-group differences in any weight-related outcome. Two studies nonetheless showed statistically significant differences between groups, including one tailored specifically for Hispanic men and another for fathers and their children (Garcia et al., 2019; O’Connor et al., 2020). Other studies showed statistically significant changes in a weight-related outcome within one group compared to baseline (O’Connor et al., 2020; Singh et al., 2020; West et al., 2008). Table 4 describes intervention outcomes in further detail.

Table 4.

Outcomes of Included Studies

| Author (publishing date) | Study participants (Mean age [SD]), Hispanic subgroup | Intervention timeline | Primary outcome | Additional outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baltaci et al. (2022) | 41.7 (7.3) | 8 week intervention Primary outcome reported at week 9 |

Adjusted difference between intervention and control BMI mean BMI change: 0.68 (0.89) kg/m2, p = .445 f |

|

| Frediani et al. (2021) | 41.9 (6.2) | 12-week intensive phase, 12-week maintenance phase Primary outcome reported at 24 weeks. |

Intervention Mean weight change: −3.8 kg (95% CI −5.2, −2.5) a |

Mean BMI change: −1.4 kg/m2 (95% CI −1.8, −0.9)

a

Mean waist circumference change: −6.6 cm (95% CI −8.0, −0.9) a |

| Garcia et al. (2018) | Intervention: 45.5 (10.4) Control: 41.0 (12.1) |

12-week intensive phase, 12-week maintenance phase Primary outcome reported at 12 weeks. |

Intervention Mean weight change: −6.3 kg (95% CI −8.1, −4.4,p< .01 compared to baseline,p< .01 compared to control) b Control Mean weight change: −0.8 kg (95% CI −2.5, 0.9) |

Intervention Mean waist circumference change: −4.7 cm (95% CI −6.2, −3.1,p< .01 compared to baseline,p< .01 compared to control) b Mean percentage of body fat change: −6.1% (95% CI −2.4, −0.89,p< .01 compared to baseline,p= .035 compared to control) b Control Mean waist circumference change: −0.39 cm (95% CI −1.9, 1.1) Mean percentage of body fat change: −0.5% (95% CI −1.2, 0.2) |

| Gary-Webb et al. (2018) | 51.7 (9.9) c | 16-week intervention Primary outcome reported at 16 weeks. |

Intervention Mean weight change among all participants: −4.4 kga,f Mean weight change among participants of Spanish-speaking cohort: −5.35 kg a,f |

|

| Guerrero et al. (2023) | Completers: 36.7 (± 7.2) Noncompleters: 39.1 (± 7.2) |

8-week intervention Primary outcome reported at 6 months |

Intervention Change in age-adjusted mean BMI: change = 0.1 kg/m2 a,f |

|

| Mitchell et al. (2015) | 30.2 (7.0) | 10-week intervention Primary outcome reported at 12–14 weeks. |

Intervention Mean change in weight: 0.6 kg a,d,f Control Mean change in weight: 1.9 kg d,f |

Intervention Mean BMI change: 0.3 kg/m2 a,d,f Mean change in waist circumference: −0.2 cm a,d,f Control Mean BMI change: 0.7 kg/m2 d,f Mean change in waist circumference: 0.68 cmd,f |

| O’Connor et al. (2020) | Intervention: 36.8 (7.61) Control: 36.1 (5.25) |

10-week intervention Primary outcome reported at 4 months. |

Intervention: Mean weight change: −2.0 kg (SD 2.57,p< .05 compared to baseline and compared to control) b Control Mean weight change: 0.6 kg (SD 1.53) |

Intervention Mean change in waist circumference: −1.6 cm (SD 1.76,p< .01 compared to baseline,p< .05 compared to control) b Mean BMI change: −0.45 kg/m2 (SD 0.86,p< .05 compared to control) b Control Mean change in waist circumference: 0.4 cm (SD 1.59) Mean BMI change: 0.2 kg/m2 (SD 0.56) |

| Rocha-Goldberg et al. (2010) | 46.1 (6.3) | 6-week intervention Primary outcome reported at week 6. |

Intervention Mean weight change: −1.32 kg (SD 1.95, d = 0.73) a |

Mean BMI change: −0.5 kg/m2 (SD 0.6, d = 0.82) a |

| Rosas et al. (2015) | Case Management (CM): 47.9 (11.9) e Case Management + Community Health care Worker (CM+CHW): 46 (10.7) e Control: 47.6 (10.5) e |

12-month intensive phase, 12-month maintenance phase Primary outcome reported at 24 months. |

CM Mean weight change: −4.3 kg (95% CI −8.7, 0.0, p = .99 compared to control, p = .99 compared to CM + CHW) CM + CHW Mean weight change: −4.5 kg (95% CI −9.7, 0.8, p = .0.99 compared to control, p = .99 compared to CM) Control Mean weight change: −4.4 kg (95% CI −11.9, 3.1) |

CM Mean BMI change: 0.7 kg/m2 (95% CI −1.4, 0, p = .90 compared to control, p = .99 compared to CM + CHW) Mean waist circumference change: −1.2 cm (95% CI −2.3, 0, p = .55 compared to control, p = .88 compared to CM + CHW) CM+CHW Mean BMI change: 0.7 kg/m2 (95% CI −1.6, 0.1, p = .91 compared to control, p = .99 compared to CM) Mean waist circumference change: −0.9 cm (95% CI −2.2, 0.4), p = .38 compared to control, p = .88 compared to CM) Control Mean BMI change: 0.6 kg/m2 (95% CI −1.8, 0.5) Mean waist circumference change: −1.7 cm (95% CI −3.2, −0.3) |

| Rosas et al. (2022) | Intervention: 47.0 (11.8) Control: 47.1 (12.1) |

12-week intensive phase, 8-month maintenance phase Primary outcome reported at 18 months. |

Intervention Mean weight change: −2.46 kg (SD 6.60, p = .06 compared to control) Control Mean weight change: −1.67 kg (SD 6.16) |