Abstract

Background

The triglyceride to high density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio (TG/HDL-C) is a confirmed predictive factor for insulin resistance and is suggested to be closely related to metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD), but previous research is inconclusive. The association between TG/HDL-C and MAFLD incidence was further explored in this large-sample, long-term retrospective cohort study.

Methods

Individuals who participated in the Kailuan Group health examination from July 2006 to December 2007 (n = 49,518) were included. Data from anthropometric and biochemical indices, epidemiological surveys, and liver ultrasound examinations were collected and analysed statistically, focusing on the association between TG/HDL-C and the incidence of MAFLD.

Results

During a mean follow-up period of 7.62 ± 3.99 years, 24,838 participants developed MAFLD. The cumulative MAFLD incidence rates associated with the first to fourth quartiles of TG/HDL-C were 59.16%, 65.04%, 71.27%, and 79.28%, respectively. The multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression model revealed that the hazard ratios (HRs) (95% CIs) for MAFLD in the second, third, and fourth quartiles were 1.20 (1.16–1.25), 1.50 (1.45–1.56), and 2.02 (1.95–2.10) (P for trend < 0.05), respectively, and the HR (95% CI) corresponding to an increase of one standard deviation in TG/HDL-C was 1.10 (1.09–1.11) (P < 0.05). Subsequent subgroup and sensitivity analyses yielded results similar to those of the main analyses.

Conclusions

TG/HDL-C is independently associated with MAFLD risk, with higher TG/HDL-C indicating greater MAFLD risk.

Keywords: Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease, TG/HDL-C ratio, Cohort study

Introduction

Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) is defined as a continuum of diseases ranging from simple steatosis with or without mild inflammation to metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) with necroinflammation and faster progression of liver fibrosis. Its global prevalence is as high as 25%, making it the most common cause of chronic liver disease worldwide, and the continued progression of MAFLD leads to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma [1].

A previous study showed that the presence of metabolic syndrome (MetS) is the strongest risk factor for MAFLD [2]. The definition of MetS typically includes obesity, hyperglycaemia, hypertension and dyslipidaemia characterized by elevated triglyceride (TG) and/or decreased high-density lipoprotein (HDL-C) levels [3]. Previous research has shown that TG/HDL-C, which has been proven to be a predictor of insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease and hypertension, is also related to the occurrence of MAFLD [4–8]. However, previous studies on the relationship between the TG/HDL-C ratio and MAFLD have several limitations, such as a small number of participants, a limited population, and a short follow-up time, which may lead to a decreased statistical power or an underestimation of the incidence rate. Additionally, cross-sectional studies have limited the interpretation of causality [8–11]. Therefore, the relationship between the TG/HDL-C ratio and MAFLD needs further research.

The Kailuan Study is a large-scale cohort study based on functional community populations involving risk factor investigation and intervention (registration number: ChiCTR-TNRC-11001489, registration date: 2011-08-24). Since 2006, the Kailuan Group has organized current and retired employees to conduct biennial health examinations. The same methods were used for each check-up to collect anthropometric, biochemical, and epidemiological data from participants and to follow up on the incidence of MAFLD and other diseases, which provided an opportunity to explore the association between the TG/HDL-C ratio and the incidence of MAFLD. The present study utilized data from the Kailuan Study to explore the association between TG/HDL-C and MAFLD incidence, and a comprehensive description of the study design and methodology was provided in a previous study [12].

Materials and methods

Data source

From July 2006 to December 2007 (referred to as 2006 annual), 11 hospitals affiliated with Kailuan Medical and Health Group (including Kailuan General Hospital, Kailuan Linxi Hospital, Kailuan Tangjiazhuang Hospital, Kailuan Fangezhuang Hospital, Kailuan Zhaogezhuang Hospital, Kailuan Lujiatuo Hospital, Kailuan Jinggezhuang Hospital, Kailuan Linnancang Hospital, Kailuan Qianjiaying Hospital, Kailuan Majiagou Hospital, and Kailuan Hospital Branch) conducted the first health examinations for Kailuan Group’s current and retired employees, collecting anthropometric, biochemical, epidemiological survey data and liver ultrasound examination data. Subsequently, trained medical staff conducted follow-up examinations at the same location and in the same order as the 2006 examination for the same group of people every two years, collecting anthropometric, biochemical, and epidemiological survey data according to the same standards as the first examination. From 2006 to 2007, a total of 101,510 Kailuan in-service and retired employees underwent health examinations, and baseline data for 49,518 participants were ultimately included in this study. This study adhered to the Helsinki Declaration and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kailuan General Hospital (Approval No: 200605). All the participants signed informed consent forms.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) current and retired employees who participated in the 2006–2007 Kailuan health examination; (2) had a normal cognitive function; and (3) independently completed the questionnaire and signed the informed consent form for this study.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) missing TG and HDL-C data; (2) previous liver diseases (such as fatty liver, viral hepatitis, or cirrhosis); (3) excessive alcohol consumption (exceeding 70 g/week (females) or 140 g/week (males)); (4) a history of malignant tumours or cardiovascular diseases; and (5) not participating in subsequent health examinations.

Data collection

Baseline data collection

The collection methods for anthropometric indices, biochemical indicators, epidemiological investigations, and other data can be found in the published literature of Kailuan Research [13]. Anthropometric indicators included height, weight, and waist circumference (WC). Biochemical indicators included triglyceride (TG), total cholesterol (TC), high-density lipoprotein (HDL-C), low-density lipoprotein (LDL-C), fasting blood glucose (FBG), blood pressure, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), uric acid (UA), and hypersensitive C-reactive protein (Hs-CRP). Epidemiological indicators included alcohol consumption, smoking status, physical exercise status, past medical history, education level, etc.

Assessment of outcomes

Follow-up physical examinations were focused on new-onset MAFLD and survival status. Follow-up commenced at the time of their first participation in the 2006 annual health examination and terminated upon the occurrence of MAFLD, death, or loss to follow-up, with a follow-up endpoint of 31st December 2020. The diagnostic criteria for MAFLD were based on the “Guidelines of Prevention and Treatment for Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A 2018 update” [14], which stipulates that individuals with two of the following three abdominal ultrasound manifestations have diffuse fatty liver: (1) diffuse increase in the echogenicity of the liver relative to the kidney; (2) gradual attenuation of far-field echoes in the liver; and (3) unclear visualization of the intrahepatic duct structure. Experienced imaging professionals conducted fasting abdominal ultrasound examinations for the participants. The equipment used was a PHILIPS HD-15 colour ultrasound diagnostic apparatus with a frequency of 3.5 MHz.

Other related definitions

The remaining variables were defined as follows: (1) body mass index (BMI; kg/m2) = weight/height2; (2) smoking was defined as smoking at least 1 cigarette per day on average in the past year; (3) physical exercise was defined as exercising at least 3 times a week for a duration of at least 30 min each time; (4) hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure (SBP) measurement ≥ 140 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥ 90 mmHg or SBP ≤ 140 mmHg and DBP ≤ 90 with a history of clearly diagnosed hypertension or antihypertensive drug use; and (5) diabetes was defined as an FBG of ≥ 7.0 mmol/L or FBG < 7.0 mmol/L with a confirmed diagnosis of diabetes or antidiabetic drug use.

Follow-up and terminal events

Follow-up physical examinations were focused on new-onset MAFLD and survival status. Follow-up commenced at the time of their first participation in the 2006 annual health examination and terminated upon the occurrence of MAFLD, death, or loss to follow-up, with a follow-up endpoint of 31st December 2020.

Statistical analysis

The collected physical examination data were uniformly entered by a specialist and uploaded to the server stored in the computer room of Kailuan General Hospital in Tangshan, Hebei, to construct an Oracle 10.2 g database. The software used for statistical analysis was SAS (version 9.4). The normally distributed data are reported as the mean ± standard deviation, and one-way ANOVA was used for comparisons between groups. The nonnormally distributed data are reported as the median (25th percentile and 75th percentile), and the Kruskal–Wallis H test was used for intergroup comparisons. The enumeration data are reported as cases (%), and the chi-square test was used for comparisons between groups.

The participants were divided into 4 groups according to TG/HDL-C quartiles. The incidence of MAFLD in the 4 groups was described in terms of person-year incidence. The Kaplan⁃Meier method was used to calculate the cumulative incidence rate of MAFLD in each group, and the log-rank test was applied to compare groups for significant differences in cumulative incidence rates. The dose‒response relationship between continuously varying TG/HDL-C and the risk of developing MAFLD was calculated using restricted cubic spline (RCS) regression. The Cox proportional hazards model was used to calculate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) for the associations between various TG/HDL-C ratio subgroups and MAFLD incidence. Subsequent stratified analyses were used to clarify the risk of MAFLD in different populations. The associations between different quartiles of the TG/HDL-C ratio and the development of MAFLD were analysed again after controlling for competing risks of death. Sensitivity analysis was applied to further test the stability of the statistical results. P values less than 0.05 (using a two-sided test) were considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

General characteristics of the study participants

A total of 101,510 individuals participated in the 2006 annual health check-up, and data for 49,518 participants were included in the statistical analyses after applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Fig. 1). The mean age of the participants was 50.10 ± 12.86 years; 36,117 males and 13,401 females were included. The participants were divided into 4 groups according to the TG/HDL-C quartile: 12,384 participants in the first quartile group (T1 group; TG/HDL-C < 0.52), 12,526 participants in the second quartile group (T2 group; 0.52 ≤ TG/HDL-C < 0.75), 12,289 participants in the third quartile group (T3 group; 0.75 ≤ TG/HDL-C < 1.13), and 12,319 participants in the fourth quartile group (T4 group; TG/HDL-C ≥ 1.13). Statistically significant (P < 0.05) between-group differences were observed for participants’ age, proportion of males, BMI, WC, SBP, DBP, FBG, TG, TC, HDL-C, LDL-C, ALT, Hs-CRP, UA, smoking status, physical activity status, hypertension status, diabetes status, high school education status and above, lipid-lowering drug use, and TG/HDL-C (Table 1). The data showed that participants in the subgroup with a higher TG/HDL-C ratio also had a greater proportion of males; greater BMI, WC, SBP, DBP, FBG, TG, TC, LDL-C, ALT, Hs-CRP, and UA; and greater proportions of smoker status, hypertension status, and diabetes status.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of participants

Table 1.

Comparison of general information of observation objects

| T1(n = 12384) | T2(n = 12526) | T3(n = 12289) | T4(n = 12319) | statistical value | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age(years) | 49.61 ± 13.44 | 49.86 ± 13.04 | 50.32 ± 12.70 | 50.59 ± 12.20 | F = 14.47 | < 0.001 |

| Male[n(%)] | 7984(64.47) | 9057(72.31) | 9159(74.53) | 9917(80.50) | χ2 = 825.21 | < 0.001 |

| BMI(kg/m2) | 22.90 ± 2.9 | 23.79 ± 2.94 | 24.36 ± 2.93 | 25.09 ± 2.93 | F = 1226.58 | < 0.001 |

| WC(cm) | 81.24 ± 9.51 | 83.48 ± 9.04 | 85.12 ± 8.95 | 87.66 ± 8.91 | F = 1090.75 | < 0.001 |

| SBP(mmHg) | 122.94 ± 19.60 | 126.04 ± 19.64 | 127.63 ± 19.56 | 129.74 ± 19.56 | F = 264.54 | < 0.001 |

| DBP(mmHg) | 78.72 ± 10.77 | 80.78 ± 10.92 | 81.83 ± 11.12 | 83.27 ± 11.12 | F = 375.48 | < 0.001 |

| FBG(mmol/L) | 5.08 ± 1.22 | 5.21 ± 1.27 | 5.29 ± 1.41 | 5.46 ± 1.70 | F = 155.83 | < 0.001 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 0.66(0.55 ~ 0.79) | 0.99(0.85 ~ 1.14) | 1.29(1.11 ~ 1.50) | 2.14(1.70 ~ 2.98) | χ2 = 37223.86 | < 0.001 |

| TC(mmol/L) | 4.75 ± 0.92 | 4.86 ± 0.96 | 4.94 ± 0.99 | 4.86 ± 1.31 | F = 61.90 | < 0.001 |

| HDL-C(mmol/L) | 1.77 ± 0.41 | 1.59 ± 0.34 | 1.46 ± 0.32 | 1.35 ± 0.33 | F = 3164.22 | < 0.001 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 2.12 ± 0.95 | 2.34 ± 0.88 | 2.38 ± 0.88 | 2.32 ± 0.98 | F = 193.13 | < 0.001 |

| ALT(U/L) | 15.00(11.00 ~ 20.80) | 17.00(12.00 ~ 22.00) | 17.00(12.00 ~ 22.00) | 18.00(13.00 ~ 24.00) | χ2 = 686.72 | < 0.001 |

| Hs-CRP(mg/L) | 0.59(0.20 ~ 1.97) | 0.66(0.23 ~ 1.90) | 0.71(0.28 ~ 2.07) | 0.87(0.31 ~ 2.40) | χ2 = 331.55 | < 0.001 |

| UA(mmol/L) | 256.53 ± 70.74 | 264.44 ± 72.09 | 272.99 ± 74.63 | 293.55 ± 83.09 | F = 553.64 | < 0.001 |

| Smoke[n(%)] | 3163(25.54) | 3406(27.19) | 3552(28.90) | 4331(35.16) | χ2 = 316.71 | < 0.001 |

| Physical activity[n(%)] | 1694(13.68) | 1662(13.27) | 1674(13.62) | 1880(15.26) | χ2 = 24.34 | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension[n(%)] | 3299(26.64) | 4179(33.36) | 4595(37.39) | 5139(41.72) | χ2 = 671.29 | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes[n(%)] | 458(3.70) | 618(4.93) | 734(5.97) | 1053(8.55) | χ2 = 289.06 | < 0.001 |

| High school and above[n(%)] | 3219(25.99) | 2453(19.58) | 2376(19.33) | 2437(19.78) | χ2 = 230.52 | < 0.001 |

| Taking lipid-lowering drugs [n(%)] | 49(0.40) | 41(0.33) | 53(0.43) | 99(0.80) | χ2 = 34.87 | < 0.001 |

| TG/HDL-C | 0.40(0.33 ~ 0.46) | 0.63(0.58 ~ 0.69) | 0.90(0.82 ~ 1.00) | 1.59(1.31 ~ 2.20) | χ2 = 46421.70 | < 0.001 |

Follow-up and incidence of MAFLD

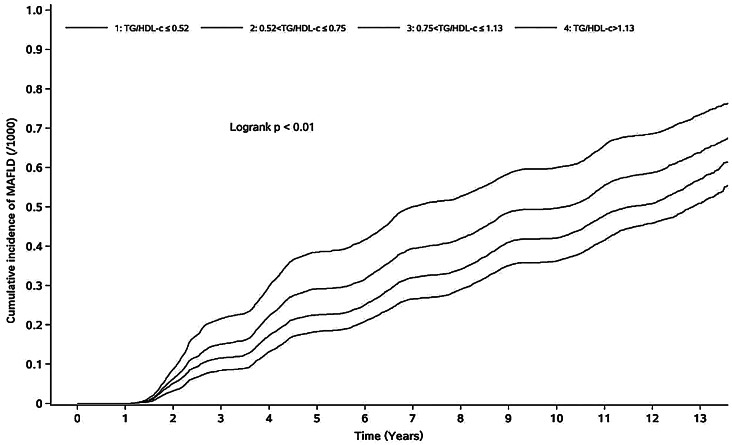

The average follow-up time for the 49,518 participants was 7.62 ± 3.99 years, and a total of 24,838 participants were diagnosed with MAFLD; 17,928 of those participants were male, and 6,910 were female. The person-year incidence rates of the individuals in the T1 ~ T4 groups were 48.34/1,000 person-years, 57.30/1,000 person-years, 70.69/1,000 person-years, and 93.08/1,000 person-years, respectively. The cumulative incidences of MAFLD in the T1 to T4 groups were 59.16%, 65.04%, 71.27% and 79.28%, respectively. The difference in cumulative incidence among the four groups was statistically significant according to the log-rank test (χ2 = 1785.71 p < 0.001) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Cumulative incidence of MAFLD in different TG/HDL-C groups

Analysis of risk factors for MAFLD

According to the multivariate Cox proportional hazards model, age, sex, WC, TC, LDL-C, UA, Hs-CRP, hypertension status, smoking status, physical activity status and ALT were found to be influential factors in the development of MAFLD (P < 0.05). Model 1 was a one-way analysis with HRs (95% CIs) of 1.20 (1.16–1.25), 1.50 (1.45–1.56), and 2.02 (1.95–2.10) in groups T2, T3 and T4, respectively, compared with those in group T1 (p for trend < 0.05). Model 2 was adjusted for age and sex, and the HRs (95% CIs) were 1.21 (1.16–1.25), 1.51 (1.45–1.57), and 2.03 (1.96–2.11) for groups T2, T3 and T4, respectively, compared with those in group T1 (P for trend < 0.05). Model 3 was further adjusted for WC, TC, LDL-C, ALT, UA, Hs-CRP, diabetes status, hypertension status, smoking status, physical activity status, high school education status and above and lipid-lowering drug use on the basis of Model 2; the HRs (95% CIs) for groups T2, T3 and T4 compared with those of group T1 were 1.13 (1.08 ~ 1.17), 1.32 (1.28 ~ 1.38), and 1.60 (1.54 ~ 1.66) (P for trend < 0.05) (Table 2). The HR (95% CI) corresponding to each standard-deviation increase in TG/HDL-C in Model 3 was 1.10 (1.09 ~ 1.11) (P < 0.05). The RCS was plotted using knots at the 5th, 50th, and 95th percentiles for the continuous TG/HDL-C variable. After adjusting for sex, age, WC, TC, LDL-C, ALT, UA, Hs-CRP, diabetes status, hypertension status, smoking status, physical activity status, high school education status and above, and lipid-lowering medication use, the risk of MAFLD was linearly associated with the TG/HDL-C ratio. The result of the linear hypothesis test of the association between the TG/HDL-C ratio and the risk of MAFLD was χ2 = 756.77 (P < 0.001), and the result of the nonlinear test was χ2 = 209.06 (P < 0.001), which indicated that there was a nonlinear relationship between the TG/HDL-C ratio and the risk of MAFLD (Fig. 3).

Table 2.

COX proportional hazards model analysis of the effect of TG/HDL-C level on MAFLD

| Events/total population | Person-year | Incidence density /103 person- years |

Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | ||||

| T1 | 5061/12,384 | 104693.28 | 48.34 | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| T2 | 5717/12,526 | 99772.65 | 57.30 | 1.20(1.16 ~ 1.25) | < 0.001 | 1.21(1.16 ~ 1.25) | < 0.001 | 1.13(1.08 ~ 1.17) | < 0.001 |

| T3 | 6433/12,289 | 90999.33 | 70.69 | 1.50(1.45 ~ 1.56) | < 0.001 | 1.51(1.45 ~ 1.57) | < 0.001 | 1.32(1.28 ~ 1.38) | < 0.001 |

| T4 | 7627/12,319 | 81936.45 | 93.08 | 2.02(1.95 ~ 2.10) | < 0.001 | 2.03(1.96 ~ 2.11) | < 0.001 | 1.60(1.54 ~ 1.66) | < 0.001 |

| P for trend | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||||

Note Model 1 was a one-way analysis; Model 2 adjusted for age and gender; Model 3 further adjusted for WC, TC, LDL-C, ALT, UA, Hs-CRP, diabetes, hypertension, smoking, physical activity, high school and above and taking lipid-lowering drugs on the basis of model 2

Fig. 3.

RCS between TG/HDL-C and the risk of MAFLD

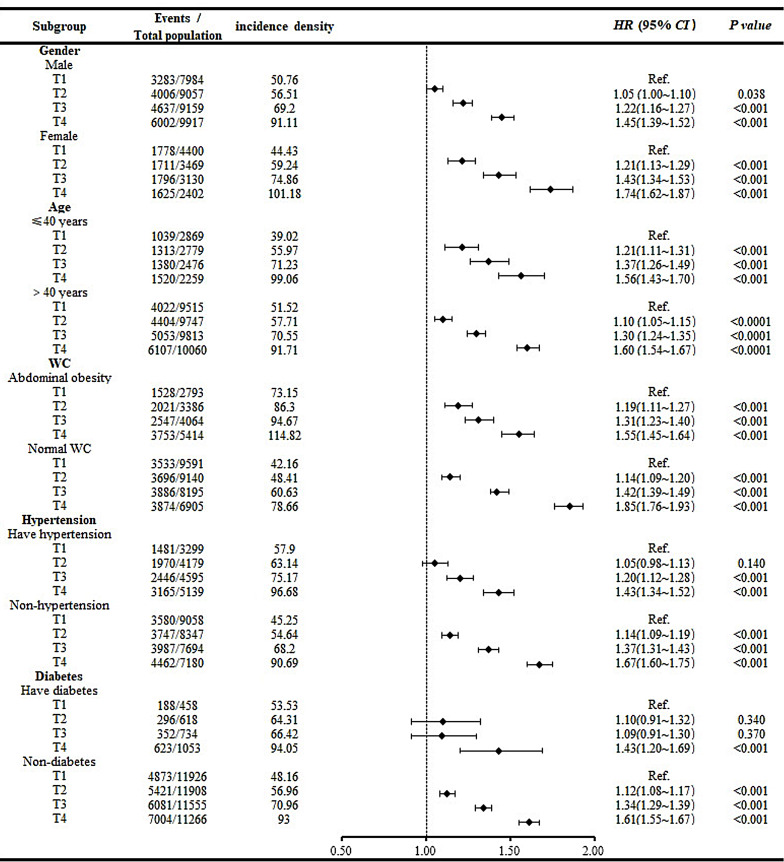

Stratified analysis

Stratified analyses were also conducted to further investigate the associations between the TG/HDL-C ratio and the development of MAFLD in populations with different characteristics. A Cox proportional hazards model was constructed with the occurrence of MAFLD as the dependent variable, TG/HDL-C quartile grouping as the independent variable and T1 as the control group. Cox proportional hazards models were constructed after the participants were stratified by sex, and the adjusted confounders were the same as those in Model 3 except for sex. In the age stratification, Cox proportional hazards analyses were repeated after the participants were divided into two groups based on whether they were older than 40 years of age, and the adjusted confounders were the same as those in Model 3 except for age. In the stratification based on WC, the overall group was divided into abdominal obesity and normal WC groups based on whether the male participants had a WC greater than or equal to 90 cm and whether the female participants had a WC greater than or equal to 85 cm. Cox proportional models were constructed again afterwards, with adjusted confounders identical to those of Model 3 except for WC. This study also included stratified analyses for hypertension status and diabetes status. In both stratified analyses, the adjusted confounders were the same as those in Model 3 except for the respective stratification factor. Each stratified analysis showed the same result as that of the main analysis: as the TG/HDL-C ratio increased, so did the risk of developing MAFLD. In addition, there are several other specific results in our stratified analyses: female participants had a greater risk of MAFLD than male participants did in the same TG/HDL-C groups according to sex. In terms of age, the risk of MAFLD in the young population was slightly greater in the T2 and T3 groups than in the older group at the same level and was slightly lower in the T4 group than in the older group. In terms of WC, we found that the MAFLD risk for participants in the T3 and T4 groups who had a normal WC was greater than that in participants with the same TG/HDL-C ratio who had abdominal obesity. Moreover, in terms of both hypertension and diabetes stratification, the risk of MAFLD was greater in the T4 group without metabolic disease than in the T4 group with metabolic disease (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Forest plot of subgroup analysis. Note Confounders adjusted for each stratification analysis were the same as in Model 3 except for this stratification factor

Competing risk model

Considering that the death of the participants would affect the overall incidence of MAFLD, we further analysed the risk of mortality via a competing risk model. After we adjusted for sex, age, WC, TC, LDL-C, ALT, UA, Hs-CRP, diabetes status, hypertension status, smoking status, physical activity status, high school education status and above, and lipid-lowering drug use, the results showed that, compared with those of the T1 group, the HRs (95% CIs) of the T2, T3, and T4 groups were 1.13 (1.08 ~ 1.17), 1.32 (1.27 ~ 1.37), and 1.61 (1.55 ~ 1.67), respectively (P for trend < 0.001) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Competing-risk model for death

| Number of deaths |

Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | ||

| T1 | 1138 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| T2 | 1172 | 1.20(1.15 ~ 1.24) | < 0.001 | 1.20(1.16 ~ 1.25) | < 0.001 | 1.13(1.08 ~ 1.17) | < 0.001 |

| T3 | 1290 | 1.49(1.43 ~ 1.54) | < 0.001 | 1.50(1.45 ~ 1.56) | < 0.001 | 1.32(1.27 ~ 1.37) | < 0.001 |

| T4 | 1278 | 1.99(1.93 ~ 2.07) | < 0.001 | 2.03(1.95 ~ 2.10) | < 0.001 | 1.61(1.55 ~ 1.67) | < 0.001 |

| P for trend | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||

Note The adjusted confounders were the same as that in model 3

Sensitivity analyses

Sensitivity analysis 1 was conducted as follows. A Cox proportional hazards model was constructed after excluding 3678 participants whose follow-up time was less than 2 years, and the adjusted confounders were the same as those in Model 3. Compared with those of the T1 group, the HRs (95% CIs) of the T2, T3, and T4 groups were 1.10 (1.06–1.15), 1.30 (1.25–1.35), and 1.56 (1.50–1.63), respectively (P for trend < 0.001). Sensitivity analysis 2 was conducted as follows. After excluding 242 participants taking lipid-lowering drugs at baseline, a Cox proportional hazards model was constructed, and the adjusted confounders were the same as those in Model 3 except for the use of lipid-lowering drugs; moreover, the HRs (95% CIs) of the T2, T3, and T4 groups compared with the T1 group were 1.13 (1.09–1.17), 1.33 (1.28–1.38), and 1.60 (1.55–1.67), respectively (P for trend < 0.001) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Sensitivity analysis

| Sensitivity analysis 1 | Sensitivity analysis 2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Events /total population |

Incidence density /103 person- years |

HR (95% CI) | P value | Events /total population |

Incidence density /103 person- years |

HR (95% CI) | P value | |

| T1 | 4671/11,799 | 45.04 | Ref | 5037/12,335 | 48.29 | Ref | ||

| T2 | 5081/11,690 | 51.67 | 1.10(1.06 ~ 1.15) | < 0.001 | 5700/12,485 | 57.33 | 1.13(1.09 ~ 1.17) | < 0.001 |

| T3 | 5668/11,312 | 63.46 | 1.30(1.25 ~ 1.35) | < 0.001 | 6408/12,236 | 70.70 | 1.33(1.28 ~ 1.38) | < 0.001 |

| T4 | 6561/11,039 | 82.28 | 1.56(1.50 ~ 1.63) | < 0.001 | 7561/12,220 | 92.95 | 1.60(1.55 ~ 1.67) | < 0.001 |

| P for trend | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||||

Note Sensitivity analysis 1: excluded 3678 subjects with less than two years of follow-up, adjusted for confounders as in model 3; sensitivity analysis 2: excluded 242 subjects taking lipid-lowering drugs at baseline, adjusted for confounders as in model 3 except for taking lipid-lowering drugs

Discussion

Over the past two decades, the disease burden of MAFLD in China has increased dramatically along with significant changes in individuals lifestyles; the estimated prevalence of MAFLD has risen abruptly from 23.8% at the beginning of the 21st century to 32.9% in 2018, and MAFLD is replacing viral hepatitis as the leading cause of chronic liver disease in China. Considering the ’massive population base of China coupled with population ageing, the predicted prevalence of MAFLD will result in a heavy disease burden in the coming decades if public health policies remain unchanged [15]. Therefore, early identification of people at high risk for MAFLD, increased vigilance against MAFLD, and a positive approach to improving and treating MAFLD at an early stage have become particularly important.

The results of this study showed that a higher TG/HDL-C ratio was associated with a greater risk of developing MAFLD. Analysis of the Cox proportional hazards model showed that after adjusting for potential confounders, the risk of MAFLD was increased 1.13-fold, 1.32-fold, and 1.60-fold in groups T2, T3, and T4, respectively, compared with that in group T1. The results of the subsequent RCS also suggested that there was a nonlinear relationship between the TG/HDL-C ratio and the risk of MAFLD and that the risk of MAFLD increased with an increasing TG/HDL-C ratio, which was generally in accordance with the results of the study by Wang et al. [16]. A previous study by Chen et al. [17]. on the association between the TG/HDL-C ratio and MAFLD in a nonobese population with normal lipid levels also yielded results similar to those of our study. However, unlike previous studies, our study focused on exploring the association between the TG/HDL-C ratio and the development of MAFLD, accounting for as many potential confounders as possible and ensuring that the sample size included in the statistical analysis was sufficiently large and the follow-up time was sufficiently long; in addition, subsequent sensitivity analyses were included to ensure the stability of the results. In general, the present study has addressed the various shortcomings of previous studies to a large extent; therefore, the results of our study are more convincing.

Stratified analyses were performed because the incidence of MAFLD may vary in populations of participants with heterogeneous characteristics. The results of each of the male and female strata in the sex stratification showed that the risk of MAFLD increased with an increasing TG/HDL-C ratio, but the risk of MAFLD was greater in female participants than in male participants in the same TG/HDL-C ratio groups, which was consistent with the results of a previous study [18]; this phenomenon became more pronounced with an increasing TG/HDL-C ratio in the present study. Cross-sectional studies [19] have shown that the risk of MAFLD in postmenopausal women is greater than that in premenopausal women. The overall mean age of the women in this study was 46.44 ± 11.28 years, which is close to the average age at menopause in Chinese women; thus, the above phenomenon may be related to the disappearance of the protective effect of oestrogen on the liver as a result of menopause. According to the age stratification, the risk of MAFLD in the younger participants was slightly greater than that in the older participants in the T2 and T3 groups despite having the same TG/HDL-C ratio, and the risk of MAFLD was slightly lower in the younger participants than that in the older participants in the T4 group. These findings suggest that young people should be concerned about their lipid health, especially in light of the decreasing age associated with MAFLD onset. After stratification according to WC, we found that the MAFLD risk for the participants in the T3 and T4 groups who had a normal WC was greater than that in participants with the same TG/HDL-C ratio group who had abdominal obesity; moreover, after stratification according to both hypertension and diabetes status, the risk of MAFLD was greater in the T4 subgroup without metabolic disease than in the T4 subgroup with metabolic disease. These results seem to differ, but we should still realize that, first, some hypoglycaemic and antihypertensive drugs can also treat MAFLD due to a common pathophysiological mechanism [20, 21]; therefore, active treatment of metabolic diseases is a necessary measure for decreasing the risk of MAFLD. Second, individuals who have abdominal obesity and suffer from metabolic diseases are likely to be more inclined to implement a healthy lifestyle, which is conducive to reducing the risk of several diseases, including MAFLD.

Because of the potential impact of death events on outcomes, we considered death a competing event and conducted the analysis again. The results shown by the mortality competing risk model were generally consistent with the main results, demonstrating again that an elevated TG/HDL-C ratio is a risk factor for MAFLD. In addition, considering the inverse causal relationship between lipid levels and MAFLD and the possible influence of lipid-lowering medication use on the results of this study, we conducted multivariate Cox regression analysis again after excluding participants with less than two years of follow-up and participants who were taking lipid-lowering drugs at baseline. Both of these analyses yielded the same results as those yielded by the main analysis, which confirmed the stability of the results in this study.

The mechanisms underlying the association between an increased risk of MAFLD and a greater TG/HDL-C ratio are currently unknown, but the following potential mechanisms may help explain the association. First, insulin resistance increases the TG/HDL-C ratio. The TG/HDL-C ratio has been shown to be strongly associated with insulin resistance in multiple ethnic groups [4, 22, 23]. Insulin resistance leads to impaired insulin-dependent inhibition of very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) secretion [24], which promotes the secretion of oversized and TG-enriched VLDL particles [25], accompanied by hypertriglyceridaemia and low HDL-C levels [26]. Insulin resistance is considered an important pathophysiological abnormality in the development of MAFLD [27]; thus, insulin resistance may mediate the relationship between the TG/HDL-C ratio and MAFLD. Second, adiponectin, which is specifically expressed and secreted by adipose tissue, can increase serum HDL-C levels and decrease serum TG levels [28]. Circulating adiponectin concentrations are reportedly lower in obese individuals than in nonobese individuals [29]; this increase has become increasingly common due to physical inactivity and overnutrition, and the resulting decrease in circulating adiponectin concentrations results in an increase in the TG/HDL-C ratio. Adiponectin also has a biological role in enhancing insulin sensitivity and ameliorating MAFLD [27], and a decrease in its circulating concentration inevitably leads to an impairment of the above biological effects, which in turn leads to a greater risk of MAFLD development.

This study has several advantages. (1) This study utilized a retrospective cohort design, which was effective at confirming the causal relationship between aetiology and disease. (2) The large number of participants included in this study and the long follow-up period resulted in high statistical validity. (3) Few participants in this study were lost to follow-up. However, this study also has several limitations. (1) Abdominal ultrasound was used as a diagnostic tool for MAFLD. Although liver tissue biopsy is currently the gold standard for diagnosing MAFLD, it is not suitable for medical check-ups. Abdominal ultrasonography is easier to perform because it is noninvasive, convenient, and inexpensive and has a high degree of sensitivity and specificity. (2) Although this study included adjustments for several MAFLD risk factors, confounders, such as dietary composition, were not considered. (3) The TG/HDL-C ratio was measured only once and may not fully reflect changes in the real life of the participants. (4) The observation subjects of this study were mainly male workers engaged in labor production in North China, with an average age of 50.10 ± 12.86 years, which cannot represent the incidence of MAFLD in the overall social population. Therefore, further research should be conducted to assess the relationship between the TG/HDL-C ratio and the development of MAFLD through better collection of physical examination data and more extensive follow-up.

Conclusions

In summary, the results of this study showed that the TG/HDL-C ratio was independently associated with the risk of MAFLD, and the higher the TG/HDL-C ratio was, the greater the risk of MAFLD. The findings of this study will contribute to the early identification of people at high risk of MAFLD. Through early interventions of lifestyle and various physiological indicators in high-risk groups, the incidence of MAFLD can be continuously reduced and the huge burden of liver-related diseases can be alleviated. In the future, the TG/HDL-C ratio may have potential as a noninvasive indicator for assessing the risk of MAFLD in clinical and epidemiologic studies, and based on the Kailuan study, we will focus on the impact of continuously varying TG/HDL-C on MAFLD in future work.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the members of the Kailuan Study Team for their contributions and the participants who contributed their data.

Abbreviations

- ALT

Alanine aminotransferase

- BMI

Body mass index

- DBP

Diastolic blood pressure

- FBG

Fasting blood glucose

- HDL-C

High-density lipoprotein

- Hs-CRP

Hypersensitive C-reactive protein

- LDL-C

Low-density lipoprotein

- METS

Metabolic syndrome

- MAFLD

Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease

- SBP

Systolic blood pressure

- TC

Total cholesterol

- TG

Triglyceride

- TG/HDL-C

Triglyceride to high density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio

- UA

Uric acid

- VLDL

Very low-density lipoprotein

- WC

Waist circumference

Author contributions

Conceived and designed the analysis: X. M.and J. J. Collected the data: J. Z., F. T., J. Y. Y. Z., J. D. Contributed data or analysis tools: L. C. Performed the analysis: H. C., J. J. Wrote the paper: X. M., J. J. Performed the manuscript review: L. C. *X. M. and J. J. contributed equally to this work.All authors have read and approved the content of the manuscript.

Funding

None.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethical approval

The study was performed according to the guidelines of the Helsinki Declaration and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kailuan General Hospital (approval number: 2006-05). All participants agreed to take part in the study and provided informed written consent.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Xiangming Ma and Jianguo Jia contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Powell EE, Wong VW, Rinella M. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease [J]. Lancet. 2021;397(10290):2212–24. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32511-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friedman SL, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Rinella M, et al. Mechanisms of NAFLD development and therapeutic strategies [J]. Nat Med. 2018;24(7):908–22. 10.1038/s41591-018-0104-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang PL. A comprehensive definition for metabolic syndrome [J]. Dis Model Mech. 2009;2(5–6):231–7. 10.1242/dmm.001180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gasevic D, Frohlich J, Mancini GB, et al. The association between triglyceride to high-density-lipoprotein cholesterol ratio and insulin resistance in a multiethnic primary prevention cohort [J]. Metabolism. 2012;61(4):583–9. 10.1016/j.metabol.2011.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.He S, Wang S, Chen X, et al. Higher ratio of triglyceride to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol may predispose to diabetes mellitus: 15-year prospective study in a general population [J]. Metabolism. 2012;61(1):30–6. 10.1016/j.metabol.2011.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller M, Stone NJ, Ballantyne C, et al. Triglycerides and cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association [J]. Circulation. 2011;123(20):2292–333. 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182160726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turak O, Afsar B, Ozcan F, et al. The role of plasma Triglyceride/High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Ratio to Predict New Cardiovascular events in essential hypertensive patients [J]. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2016;18(8):772–7. 10.1111/jch.12758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fan N, Peng L, Xia Z, et al. Triglycerides to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio as a surrogate for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a cross-sectional study [J]. Lipids Health Dis. 2019;18(1):39. 10.1186/s12944-019-0986-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lu S, Kuang M, Yue J, et al. Utility of traditional and non-traditional lipid indicators in the diagnosis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in a Japanese population [J]. Lipids Health Dis. 2022;21(1):95. 10.1186/s12944-022-01712-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li R, Kong D, Ye Z, et al. Correlation of multiple lipid and lipoprotein ratios with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetic mellitus: a retrospective study [J]. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1127134. 10.3389/fendo.2023.1127134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Catanzaro R, Selvaggio F, Sciuto M, et al. Triglycerides to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio for diagnosing nonalcoholic fatty liver disease [J]. Minerva Gastroenterol (Torino). 2022;68(3):261–8. 10.23736/S2724-5985.21.02818-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao D, Cui H, Shao Z, et al. Abdominal obesity, chronic inflammation and the risk of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease [J]. Ann Hepatol. 2023;28(4):100726. 10.1016/j.aohep.2022.100726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu S, Huang Z, Yang X, et al. Prevalence of ideal cardiovascular health and its relationship with the 4-year cardiovascular events in a northern Chinese industrial city [J]. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012;5(4):487–93. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.111.963694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National workshop on fatty L, Alcoholic liver disease C, S O H C M, A. Fatty liver expert committee C M D A. [Guidelines of prevention and treatment for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a 2018 update] [J]. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi, 2018, 26(3): 195-203. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1007-3418.2018.03.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Zhou J, Zhou F, Wang W, et al. Hepatology. 2020;71(5):1851–64. 10.1002/hep.31150. Epidemiological Features of NAFLD From 1999 to 2018 in China [J]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Wang J, Li H, Wang X, et al. Association between triglyceride to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and liver fibrosis in American adults: an observational study from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2017–2020 [J]. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2024;15:1362396. 10.3389/fendo.2024.1362396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen Z, Qin H, Qiu S, et al. Correlation of triglyceride to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease among the non-obese Chinese population with normal blood lipid levels: a retrospective cohort research [J]. Lipids Health Dis. 2019;18(1):162. 10.1186/s12944-019-1104-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fukuda Y, Hashimoto Y, Hamaguchi M, et al. Triglycerides to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio is an independent predictor of incident fatty liver; a population-based cohort study [J]. Liver Int. 2016;36(5):713–20. 10.1111/liv.12977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee C, Kim J, Jung Y. Potential therapeutic application of estrogen in gender disparity of nonalcoholic fatty liver Disease/Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis [J]. Cells. 2019;8(10). 10.3390/cells8101259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Ferguson D, Finck BN. Emerging therapeutic approaches for the treatment of NAFLD and type 2 diabetes mellitus [J]. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2021;17(8):484–95. 10.1038/s41574-021-00507-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cusi K, Isaacs S, Barb D, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinology Clinical Practice Guideline for the diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver Disease in Primary Care and Endocrinology Clinical Settings: co-sponsored by the American Association for the study of Liver diseases (AASLD) [J]. Endocr Pract. 2022;28(5):528–62. 10.1016/j.eprac.2022.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou M, Zhu L, Cui X, et al. The triglyceride to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (TG/HDL-C) ratio as a predictor of insulin resistance but not of beta cell function in a Chinese population with different glucose tolerance status [J]. Lipids Health Dis. 2016;15:104. 10.1186/s12944-016-0270-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ren X, Chen ZA, Zheng S, et al. Association between triglyceride to HDL-C ratio (TG/HDL-C) and Insulin Resistance in Chinese patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes Mellitus [J]. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(4):e0154345. 10.1371/journal.pone.0154345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Poulsen MK, Nellemann B, Stodkilde-Jorgensen H, et al. Impaired insulin suppression of VLDL-Triglyceride Kinetics in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease [J]. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101(4):1637–46. 10.1210/jc.2015-3476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lucero D, Miksztowicz V, Macri V, et al. Overproduction of altered VLDL in an insulin-resistance rat model: influence of SREBP-1c and PPAR-alpha [J]. Clin Investig Arterioscler. 2015;27(4):167–74. 10.1016/j.arteri.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sparks JD, Sparks CE, Adeli K. Selective hepatic insulin resistance, VLDL overproduction, and hypertriglyceridemia [J]. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32(9):2104–12. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.241463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sakurai Y, Kubota N, Yamauchi T, et al. Role of insulin resistance in MAFLD [J]. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(8). 10.3390/ijms22084156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Christou GA, Kiortsis DN. Adiponectin and lipoprotein metabolism [J]. Obes Rev. 2013;14(12):939–49. 10.1111/obr.12064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arita Y, Kihara S, Ouchi N, et al. Paradoxical decrease of an adipose-specific protein, adiponectin, in obesity [J]. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;257(1):79–83. 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.