Abstract

Background

This case study examines the application of Integrated Enhanced Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (I-CBTE) for a patient with severe, longstanding anorexia nervosa and multiple comorbidities, including organic hallucinosis, complex post-traumatic stress disorder (CPTSD), and severe self-harm. Such complex presentations often result in patients falling between services, which can lead to high chronicity and increased mortality risk. Commentaries from two additional patients who have recovered from severe and longstanding anorexia nervosa are included.

Case study

The patient developed severe anorexia nervosa and hallucinosis after a traumatic brain injury in 2000. Despite numerous hospitalisations and various psychotropic medications in the UK and France, standard treatments were ineffective for 17 years. However, Integrated Enhanced Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (I-CBTE) using a whole-team approach and intensive, personalised psychological treatment alongside nutritional rehabilitation proved effective.

Methods

In this paper, we describe the application of the I-CBTE model for individuals with severe, longstanding, and complex anorexia nervosa, using lived experience perspectives from three patients to inform clinicians. We also outline the methodology for adapting the model to different presentations of the disorder.

Outcomes

The patient achieved and maintained full remission from her eating disorder over the last 6 years, highlighting the benefit of the I-CBTE approach in patients with complex, longstanding eating disorder histories. Successful treatment also saved in excess of £360 k just by preventing further hospitalisations and not accounting for the improvement in her quality of life. This suggests that this method can improve outcomes and reduce healthcare costs.

Conclusion

This case study, with commentaries from two patients with histories of severe and longstanding anorexia nervosa, provides a detailed description of the practical application of I-CBTE for patients with severe and longstanding eating disorders with complex comorbidities, and extensive treatment histories. This offers hope for patients and a framework for clinicians to enhance existing treatment frameworks, potentially transforming the trajectory of those traditionally deemed treatment resistant.

Recommendations

We advocate the broader integration of CBT for EDs into specialist services across the care pathway to help improve outcomes for patients with complex eating disorders. Systematic training and supervision for multidisciplinary teams in this specialised therapeutic approach is recommended. Future research should investigate the long-term effectiveness of I-CBTE through longitudinal studies. Patient feedback on experiences of integrated models of care such as I-CBTE is also needed. In addition, systematic health economics studies should be conducted.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s40337-024-01116-7.

Keywords: Anorexia nervosa, Integrated enhanced cognitive behavioural therapy (I-CBTE), Severe and Enduring Eating Disorder (SEED), Severe and Longstanding Anorexia Nervosa (SE-AN), Comorbidities, Inpatient, Case study, Treatment effectiveness, Formulation, Compulsory treatment, Illness duration, Terminal anorexia

Plain language summary

This case study, with commentaries from two other patients who have recovered from severe and longstanding anorexia nervosa, examines the use of Integrated Enhanced Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (I-CBTE) for a patient with severe and longstanding anorexia nervosa and multiple comorbidities. The patient had a history of multiple hospitalisations and was treated with various psychotropic medications without success for 17 years. However, she responded to I-CBTE. The model integrates multidisciplinary treatment to address the eating disorder and co-occurring conditions effectively. The patient achieved and maintained full remission from her eating disorder over the last 6 years, highlighting the effectiveness of the I-CBTE approach in patients with complex, longstanding and severe eating disorders. This intervention is cost-effective and has significant financial advantages for healthcare systems. The authors recommend further research into the long-term effectiveness of I-CBTE and broader integration of CBT for ED into clinical services and existing treatment frameworks to enhance care for patients with severe and longstanding eating disorders. Systematic training and supervision for multidisciplinary teams is needed and patient feedback on experiences of integrated models of care such as I-CBTE is also needed. Finally, systematic health economics studies should be conducted.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s40337-024-01116-7.

Introduction

The second of the linked papers examines the application of Integrated Enhanced Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (I-CBTE) for a patient, Lorna, with severe, enduring anorexia nervosa (SE-AN) and comorbidities such as traumatic brain injury (TBI), organic hallucinosis, depression, complex post-traumatic stress disorder (CPTSD), emotionally unstable or organic personality disorders and self-harm [1]. Patients with such complex presentations often fall between services, resulting in substantial risk of chronicity and mortality. Commentaries and lived experience examples of two other patients are included. Lyn, received I-CBTE and recovered after more than 30 years of severe and longstanding anorexia nervosa, without complex co-morbidities (see Additional File 1) and Mollie, who is autistic, recovered after 12 years and 10 inpatient admissions and compulsory treatment for SE-AN (see Additional File 2).

There is significant controversy regarding the optimal treatment for patients with severe and longstanding eating disorders [2]. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) [3] does not address this issue in the evidence-based recommendations for England and Wales. Traditional inpatient treatment as usual (TAU) has been criticised for poor outcomes and high financial and psychosocial costs [4, 5]. Furthermore, the separation of inpatient and community care teams makes patients more likely to experience unplanned admissions and discharges, therapy interruptions, and changes in the therapeutic models. Severe and enduring eating disorder (SEED) pathways have been developed widely in the National Health Service (NHS) based on the assumption that patients with longstanding illnesses do not benefit from inpatient treatment or full weight restoration, despite evidence to the contrary [6–9]. The notion of focusing on improving quality of life (e.g. through education and employment), rather than full weight restoration and recovery [10, 11] is, in our opinion, a contradiction in terms. There is no consensus among clinicians regarding the definition and treatment of patients with longstanding EDs [12, 13]. Patients have raised concerns that SEED pathways have become a ‘management of decline’ and are campaigning for more effective treatments [2, 14]. More research is therefore urgently needed, as well as the development of novel conceptualisations of treatments that move beyond historic approaches that render patients institutionalised, traumatised, and disempowered [15].

Patients with EDs exhibit significant heterogeneity, which may explain why up to 50% of diagnosed individuals do not improve from first-line treatment. Research is increasingly showing that personalised approaches have longer-lasting and more effective outcomes than average-based treatments [16, 17].

This detailed case study aims to illustrate the practical application of I-CBTE and demonstrates its potential to provide hope and effective treatment for patients with SE-AN. The paper outlines the formulation-based MDT treatment process, the key elements of the I-CBTE model, and how to personalise these components for individual patients. We aim for clinicians to use this guide to effectively apply the I-CBTE approach to patients with severe, longstanding EDs, complex comorbidities, and multiple admissions in their own practice.

Additionally, the two linked papers and Lyn and Mollie’s commentaries (see Additional Files 1 & 2) contribute to the academic dialogue by challenging the controversial concept of terminal anorexia [23] which has caused alarm among patients [24–26] and could have been relevant for Lorna at certain times.

Method

In the first linked paper, Lorna provided a personal narrative of her lived experience of having a severe, longstanding eating disorder and other mental and physical co-morbidities [1]. This second paper details the personalised application of the I-CBTE model, illustrating the main components of treatment through a comprehensive clinical description of Lorna’s case with the aim of helping services apply the model for their patients. Lorna kept detailed personal notes and clinical reports of her treatment spanning decades which together with the I-CBTE clinical notes helped reduce memory bias. We only reported the coping strategies and aspects of MDT treatment that she found helpful as evidenced by entries in historical clinical notes and her formulation document.

We also include two patients’ commentaries on this paper. Lyn’s commentary describes her personal narrative of living with severe and longstanding anorexia nervosa for more than three decades and how recovery was possible with I-CBTE in tandem with an emphasis on full weight restoration (see Additional File 1). Mollie’s commentary on this paper, highlights the value of a formulation-driven, holistic and multi-disciplinary I-CBTE approach delivered seamlessly across the inpatient, day-patient and community pathway which enabled her to recover when she would have been deemed ‘untreatable’ and a ‘candidate for palliative care’ after 10 admissions in 12 years. Her I-CBTE treatment was effective despite having to use compulsory treatment during her last admission in 2020. Mollie was subsequently diagnosed with autism (see Additional File 2). Lyn and Mollie’s personal narratives and commentaries provide further lived experiences and insights into the benefits of the model for their recovery journey from SE-AN. Overall, the three lived experience examples of Lorna, Lyn and Mollie, each with very different clinical presentations, highlight the human aspects of the condition and the transformative potential of effective personalised treatment models such as I-CBTE. We discuss clinical implications and generalisability of the I-CBTE model for other patients with severe and longstanding eating disorders.

Description of the integrated enhanced cognitive behavioural therapy (I-CBTE) model

Our work with Lorna began when she had already spent almost 20 years being repeatedly hospitalised without any improvement. This happened at the same time as the introduction of I-CBTE programme on our specialist ED unit (SEDU) [9]. This model addresses the problem of multiple fragmentations in mental health systems. It utilises a multidisciplinary team (MDT)-based inpatient programme that helps patients achieve a healthy weight through intensive psychological treatment and integration of treatment across the care pathway. Originally developed by Fairburn as an outpatient therapy for bulimia nervosa [18, 19], CBT-Enhanced has been adapted by the Dalle Grave for patients with severe AN requiring more intensive treatment [20–22].

The I-CBTE model is integrated, inclusive, intensive, and individualised and has been adapted for patients with severe EDs who do not respond to outpatient treatment. The model expands on the CBT for ED approach and is integrative because it is a ‘whole systems approach’ informed by a biopsychosocial formulation. Evidence-based treatments for the range of maintaining factors and comorbidities are incorporated in a coordinated manner and delivered by an MDT, ideally in-house or where needed seamlessly across the inpatient, day, and outpatient care pathways and across the life span. I-CBTE collaboratively involves patients, family, friends, the MDT, other treatment providers, and stakeholders. The treatment is intensive in a stepped-care approach, requires MDT (rather than a single therapist) interventions, and is delivered with increased intensity and higher dosages of interventions (e.g. multiple therapy sessions per week) depending on the patient’s needs. Individualised care implies that the model is patient-led (e.g. respecting their choices and preferences), with personalised formulation of needs, goals, and precision treatment.

Components of I-CBTE compared with TAU

We introduced the I-CBTE approach in Oxford specialised eating disorder unit (SEDU, ‘Cotswold House’) in 2017. This programme offers evidence-based psychological treatment across inpatient, day-patient, and community settings, with a structured timeline of 13 weeks of inpatient treatment, 7 weeks of stabilisation as a day-patient, and up to 40 weeks of outpatient care as recommended by Dalle Grave [20].

Key innovations included the introduction of MDT admission planning meetings. This preparation process aimed to empower patients by promoting a sense of control and autonomy, fostering therapeutic alliance and trust before admission, and is crucial for successful engagement and treatment outcomes. Additionally, we improved the rate of weight restoration to 1–1.5 kg per week.

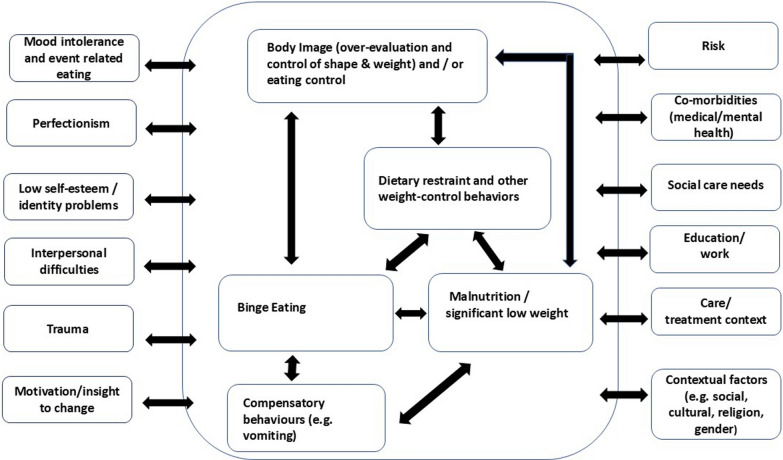

CBT for eating disorders identifies a comprehensive range of maintaining factors (Fig. 1) such as body image and/or eating control, dietary restraint and other weight control behaviours, malnutrition, binge eating, compensatory behaviours (e.g. over-exercising, vomiting), mood intolerance and event-related eating, perfectionism, low self-esteem/identity issues, and interpersonal relationship difficulties. To accommodate the complexity of inpatients, we added additional maintaining factors such as unresolved trauma and any medical and mental health comorbidities to the formulation. The model is flexible to include motivation to change/insight, risks, social care needs, education/employment, the care/treatment context, and other contextual and diversity factors (e.g. gender, culture, and religion).

Fig. 1.

Formulation diagram with key maintaining factors that needs to be personalised for each patient

While CBT for EDs is a psychological model typically delivered by one therapist, [18] MDT involvement is essential for patients with SEED [22]. In partnership with the patient, all team members need to work together to address individual maintaining factors. Qualified psychologists provided evidence-based, personalised therapy to address patients’ unique combinations of maintaining factors, including depression, OCD, trauma, etc. Psychologists joined family sessions when clinically indicated. Psychological treatment was enhanced through the development of a rolling 20-week MDT group programme focussing in more depth on the key maintaining factors in the formulation (e.g. body image, self-esteem, perfectionism, interpersonal difficulties, nutrition, Dialectical Behaviour Therapy skills (DBT) for mood intolerance). Rolling 10-week formulation groups (later co-presented with Lorna after she was well and discharged) were popular with patients and staff, and introduced them systematically to the formulation diagram and helped them to ‘idea storm’ coping strategies for each of the maintaining factors.

Patient experience was improved by making the ward rounds more collaborative, person-centred, less anxiety-provoking, and focussing on formulation-based goals [23].

The transition from TAU to I-CBTE marked a shift towards an evidence-based, patient-centred approach to treating severe EDs and pioneered integration of psychological and medical treatments to improve patient outcomes. The differences between inpatient TAU and I-CBTE treatment approaches are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1.

The differences between inpatient TAU and I-CBTE treatment approaches

| TAU in England [24] | I-CBTE [9] | |

|---|---|---|

| Preparation for admission | Rarely | Yes |

| Time-limited admission | No | Yes: 13 weeks inpatient & 7 weeks day treatment |

| Weight restoration goal | Variable (mean discharge BMI in the UK = 17) | Min BMI: 20 |

| Speed of weight restoration | 0.5–1 kg/week | 1–1.5 kg/ week |

| Individual psychological approach |

Eclectic Often BMI dependent |

I-CBTE & evidence-base therapies for co-morbidities commencing with the co-creation of a formulation soon after admission (irrespective of BMI) |

| Number of psychological therapy sessions per week | Variable (often linked to a minimum BMI of 15) | 1–2 individual sessions & family sessions irrespective of BMI starting with a collaborative formulation |

| Groups | Eclectic | I-CBTE formulation based including DBT principles (4 groups per week, 80 groups per 20-week cycle) |

| MDT approach | Eclectic | Whole team I-CBTE |

| Weight stabilisation | Variable | Yes, day hospital |

| Aftercare | Variable | Seamless handover to day and/or outpatient I-CBTE |

Although many patients have benefited from the I-CBTE approach [9], few wish to share their experiences publicly. However, individual case studies, such as Lorna’s, provide invaluable insights beyond the aggregated data. Lyn and Mollie’s commentaries illustrate their lived experiences and similar improvements from SE-AN through I-CBTE after many years of severe and potentially life-threatening illnesses (see Additional Files 1 & 2).

Detailed case study: Lorna

The first of the two linked papers describes in detail Lorna’s lived experience of her physical and mental health recovery journey [1]. In summary, she had a complex psychiatric history that began in 2000, following a horse-riding accident when she was 18-years-old and suffered a TBI. She was in a coma for several days, and brain scans showed multiple lesions following the head injury, particularly affecting the right parietal lobe, temporal lobe, and claustrum. Prior to the accident, she was highly functioning, excelling in both academia and sports. There is no family history of mental illness.

She was hospitalised on many occasions (See Table 2) and never out of hospital for more than 6 months, over a span of 17 years, because of AN, acute mental health crises, and incidents of life-threatening self-harm. She struggled with chronic malnutrition and required repeated emergency medical treatments, often against her will. Lorna experiences residual visual, auditory, and tactile hallucinations, but these do not interfere with her functioning.

Table 2.

History of admissions (excluding multiple admissions to acute mental health wards, A&E and general hospitals)

| Year | Event/Treatment | Description | Legal status | Medication | Psychological Treatment | Length of stay (LOS, months) & Estimation of cost of psychiatric admissions* | Discharge BMI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | Traumatic Brain Injury | Patient suffered a brain injury from a horse-riding accident, leading to the onset of AN and other mental health issues | Sodium Valproate | 19.2 (as a jockey before the TBI) | |||

| 2001 | First Admission SEDU A | Initial admission to a SEDU, marking the beginning of over 30 psychiatric admissions | Informal | Citalopram | Some group therapies |

4 months ~ £60 k |

15 |

| 2002–2007 | SEDU B Repeated admissions | Multiple admissions to SEDU B and acute wards, including treatments like electroconvulsive therapy and various treatments | Compulsory | Olanzapine, Diazepam, Zopiclone | Psycho-dynamic group therapy, a CBT group, 1:1 therapy (humanist existential model) |

6 months ~ £90 k 9 months ~ £135 k 12 months ~ £180 k & shorter admissions |

18 (but water loading 4 kg) |

| 2011 | Hospital admissions in Paris | Collapsed while teaching, leading to further hospital admissions and detainment in a mental institution in Paris | Compulsory | Valium, Omeprazole | None | 2 months | 12 |

| 2011–12 | Return to England (SEDU C) | After severe deterioration in Paris, returned to England for treatment at SEDU C. Discharged self and returned to Paris, experiencing severe symptoms and hallucinations | Compulsory | Valium, Omeprazole | 1:1 therapy (Cognitive analytical therapy) |

2 months ~ £30 k 3 months ~ £45 k |

12 |

| 2012–2016 | SEDU C Repeated admissions | Multiple admissions to SEDU C in England, with continued struggle in treatment and care, leading to severe mental and physical deterioration | Compulsory | Olanzapine, Sodium Valproate |

Same groups as in previous admissions 1:1 art therapy (6 sessions) |

5 months ~ £75 k 6 months ~ £90 k 8 months ~ £120 12 months ~ £180 + shorter admissions |

17.5 (at final admission, a variety of BMIs at previous admissions, including > 14) |

| 2017–2018 | I-CBTE at Cotswold House (Oxford) SEDU | Introduction to I-CBTE, leading to significant improvements in health and well-being | Informal |

Olanzapine, Sertraline Lithium |

I-CBTE & support from the whole MDT |

5 months ~ £75 k |

20 |

| 2018–2020 | Ongoing community treatment | Seamless transition to continued care in the community with I-CBTE therapy, dietary support, and consultant psychiatrist, leading to significant recovery | Informal |

Olanzapine Sertraline Lithium |

I-CBTE | 12 months | 20 |

*Estimation of psychiatric inpatient cost is based on a conservative mean £500/day since 2000

Throughout her medical history, she had multiple changes in her diagnoses, and in addition to AN, she was diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder, schizophrenia, psychotic depression, various types of personality disorder (e.g. emotional unstable personality disorder, organic personality disorder), organic hallucinosis, and CPTSD which highlights the complex nature of her condition but caused confusion and inconsistency in her treatment. She was treated with multiple psychotropic medications and received an eclectic combination of individual and group therapies (Table 2). Her admissions represented typical TAU in the UK SEDUs.

The total cost of her psychiatric admissions prior to the I-CBTE treatment was in excess of £1million (based on a conservative estimate of £500/bed day on average) in 17 years, approximately £60 k/year. Since completing I-CBTE treatment, she has not had any admissions in 6 years and saved approximately £360 k for the NHS on psychiatric admissions alone, not to mention an improved quality of life, ability to work and flourish, and her life being saved.

Formulation-informed multidisciplinary treatment

The I-CBTE formulation was at the centre of Lorna’s treatment and encouraged her to consider why she became ill and what the maintaining factors were. She had a background in research and found this useful because it helped to justify and understand the illness rather than blaming herself. A personalised version of the formulation diagram (Fig. 1) provided a ‘helicopter overview’ of her key maintaining factors and guided her and the MDT (including dieticians, family therapists, nursing staff, occupational therapists, psychologists, psychiatrists) in terms of goal setting and the development of a detailed MDT treatment plan. The staff helped her develop a range of old and new coping skills and strategies (‘tools in her toolbox’) for each maintaining factor and to ultimately become her own therapist. Similarly, other patients, including Lyn and Mollie found the personal formulation very helpful (See Additional Files 1 & 2).

Every member of the multidisciplinary team at Cotswold House contributed towards my treatment. I could speak to someone on each shift about how I was doing. In this way, I built trust with the team, as they all said the same thing, which supported my recovery journey.

The I-CBTE model worked because it was built on my strengths and flexible to my particular situation ... I accrued a bundle of go-to resources to help me deal with life’s continual ups-and-downs... [1]

Body-image and overevaluation of weight and shape and control

Lornas’ ED involved an extremely negative body image and a strong ‘need for control’. She presented with weight-checking behaviours (e.g. frequent weighing), shape checking (e.g. measuring body parts, checking for a flat stomach), and shape avoidance behaviours (e.g. wearing baggy clothes and avoiding looking at certain body parts). She engaged in comparison making behaviours with others (i.e. a competition to be the thinnest) and herself (e.g. when she was at a lower weight). Her artwork illustrated distorted perceptions of her body and beliefs of being fat. According to her notes, therapy and psychoeducation helped her develop a range of coping strategies, including setting goals for self-care, using self-talk techniques, and building a new identity separate from her appearance (i.e. to become a ‘survivor’ and to transition from a ‘chrysalis to being a butterfly’). Members of the MDT coordinated their interventions to improve her body image. For example, to help with between-therapy session tasks, the assistant occupational therapist took her shopping to explore which clothes and jewellery she liked wearing and made her feel more comfortable in her body. The importance of the whole team approach was also highlighted by other patients (see Additional Files 1 & 2).

Dietary restriction and other weight control behaviours

Patients restrict their food and drink intake for many reasons. For Lorna, it was to manage her weight, to regain a sense of control, a method of ‘self-destruction’, to ‘purify’ herself and to gain a sense of achievement. Obsessions with food restriction, weight control and over-exercising helped to deal with the voices, frustration with the brain injury, and ‘bad’ emotions of shame and guilt. Alongside psychological therapy to address the underlying reasons for restricting (e.g. trauma, emotional dysregulation, low self-esteem), the dietetic, medical, and nursing teams played a key role in helping her restore weight through psychoeducation, maintaining her safety with alternative skills for emotional regulation and distress tolerance, implementing meal plans, and transitioning to independent shopping and social eating. Calorie counting, to distract from the hallucinations, required further neurological assessments and management with medication and cognitive behavioural and Dialectical Behaviour Therapy (DBT) strategies. A collaborative approach with Lorna was essential to replace the sense of control provided by dietary restriction and weight control behaviours.

Malnutrition and secondary effects of being underweight

Similar to other patients who experienced repeated admissions with partial weight restoration, Lorna found it difficult to accept that full weight restoration was essential for recovery. Helping her understand the science and sharing outcome data helped her take a plunge and work towards full weight restoration. Supported by the MDT, she engaged in nutritional groups and mealtime planning with a dietician, and healthcare assistants helped her manage post-meal discomfort using new strategies such as painting and writing. She achieved a BMI of 20 at discharge and continued her progress in the community, stabilising at approximately a BMI of 22. Weight restoration meant that the secondary psychological (e.g. rigid and black-and-white thinking), physical (e.g. exhaustion, dehydration, dizziness, feeling weak, and cold), and social effects of malnutrition went into remission.

During previous admissions… I managed to convince the doctors that I did not need to put on much weight at all. The physicians then entertained this idea and never attained a healthy weight. I did not even know what a healthy weight was. The breakthrough came at Cotswold House, where I realised that if any kind of future or life was possible, I needed to put on a lot more weight and be this new thing—a ‘healthy weight’. I learned that doing this would allow my body to heal, and it would give me the chance to finally live well. Suddenly, I had options: not just an eating disorder but a future [1].

Compensatory behaviours

Lorna identified overexercising and the use of appetite suppressants (e.g. compulsively chewing gum and drinking fizzy drinks) as key maintaining factors. Treatment helped her to stop and learn healthy alternatives to replace these behaviours. By the time she was discharged, she no longer had the inclination to use these behaviours.

Mood intolerance and event-related eating

Lorna’s ED and self-harm were partly coping strategies to numb and regulate intolerable emotions and feelings of shame, guilt, low mood, frustration, and impatience with herself. Self-harm incidents were extreme acts of aggression for not meeting her own standards, for internalising anger towards her family, and for ‘being angry at being angry’. Her medication (and reminders), individual therapy, I-CBTE groups, and the MDT helped her find new ways to express her emotions (e.g. writing poems, cathartic painting), problem-solving to deal with situations, and use DBT skills [25] for mood intolerance.

Perfectionism

In her family, high standards provided an ‘exemplary, necessary method of living’. Striving for perfectionism reflected her ambitions and competitiveness, including a desire to become an Olympic champion, and meant that she could never appreciate or be satisfied with her performance. Achievements were replaced with higher targets. The MDT supported her in challenging her perfectionism and developing skills to build a new outlook for herself and her world. In this regard, overcoming perfectionism required a wide variety of new strategies, such as learning to identify ‘vicious cycles of perfectionism’, setting and celebrate smaller achievable goals, setting goals for other areas of her life, developing a better work/life balance, using kind rather than critical self-talk, and ‘rewarding herself for rewarding herself’.

Low self-esteem and identity problems

Lorna exhibited many negative cognitive processes of a core low self-esteem such as discounting any positive qualities and achievements, selective attention to her ‘defects’, and applying double and higher standards for herself than for others. The individual therapy and self-esteem groups taught her many skills to improve her self-esteem, and she was able to replace negative core beliefs (for example, ‘I am bad, not good enough, insufficient, always wrong’) with new helpful self-beliefs (for example, ‘I am a survivor and a butterfly’).

Interpersonal difficulties

Lorna was estranged from her family during long periods of her life, and they declined formal family therapy sessions. However, changing the language and offering ‘meetings to manage Lorna’s transition to the community’, rather than calling it ‘family therapy’, helped to engage her family and enabled her to successfully transition back into her family and to rebuild fulfilling relationships. Regular family Sunday lunches were introduced with the family and continue to this day.

Trauma

Components of trauma-focused CBT, as recommended by NICE [26], were integrated into Lorna’s treatment, such as psycho-education about trauma reactions; strategies for managing arousal and flashbacks; development of a trauma narrative; safety planning; processing trauma-related emotions such as guilt, shame, and anger; restructuring trauma-related meanings; and re-establishing adaptive functioning, such as engaging in work. Integrating art and paintings into therapy allowed her to process and express the unsayable through other means than self-harm wounds. Painting was a helpful distraction strategy, provided a window for others into her internal pain and trauma, and was an important part of the healing process.

...I used my art (painting and poetry) to express the most difficult issues, about trauma, abuse, dissociation and amnesia. David would ask me to paint what I could not speak about. I was able to go away and paint a picture (abstract or figurative), which opened the unmentionables. We then discussed this painting, and approached the topic from a creative angle, which made it more possible to process. In this way, I began dealing with the most difficult roots of my illness [1].

Motivation and insight to change

Lorna’s motivation, insight, and commitment to change fluctuated, and, for long periods, the team had to hold the hope that recovery was possible. For example, she resisted achieving a healthy weight, but with education and support from the staff, her trust in the team and herself grew, which in turn helped her motivation. She felt increasingly motivated to recover, as she began to experience that weight gain and progress on various historic maintaining factors were realistic and attainable targets.

Risks

Lorna had a very high risk of suicide with a history of severe self-harm and multiple suicide attempts. Her extreme self-harm had many functions.

Self-harm was a method of communication, but nobody was listening. Maybe I did not exist; only the men telling me to destroy myself were real [1].

The coping strategies that she found most helpful were talking to staff and finding distraction techniques which worked best e.g. ice packs on her wrist, listening to music to distract from the ‘aural cacophony’ and using self-statements (e.g. ‘I’ve had periods of not doing it, which shows that it is possible to resist the urges and stay safe’), reminding herself that there were things she wanted to do in this world, which she couldn’t if she destroyed herself. In this regard, spending time in nature with her dog and horses after discharge provided sustained relief and reminded her that she had a purpose and was needed. Writing and making art to express how she felt was all-important.

My paintings allowed me to express myself in some other means than my wounds. The abstract images I created embodied my feelings and gave me a voice other than self-injury. I could show the ward doctor the paintings and he could then understand my illness since I would paint how I felt [1].

Medical and psychiatric comorbidities

For many years, my eating disorder provided a (flawed) coping mechanism for the mental health difficulties I was having. After decades of unsuccessful treatment, the holistic, expansive care I received in Oxford helped me ...[1]

Lorna’s case underscores the necessity for integrating evidence-based treatments for both psychiatric and medical comorbidities which, if left untreated, complicate treatment and hampers outcomes [27]. Lorna’s treatment included interventions and principles from trauma-focused CBT; DBT for emotional dysregulation, distress tolerance, and self-harm; and CBT principles for the eating disorder and psychosis. Writing or creating art about her psychotic and trauma experiences were therapeutic and helped clinicians to understand what she was experiencing.

The TBI left her with organic hallucinosis and a range of visual and auditory (e.g. piercing sounds, noises, and voices), olfactory (e.g. smells that others could not smell), and tactile (being touched by a physical presence) hallucinations that contributed to her self-harm behaviour. Joining meetings of a Hearing Voices Network provided support and made her feel accepted by people with unique feelings and experiences.

Optimising her psychotropic medication was essential. We recommended Olanzapine as this has been shown to be beneficial in both hallucinosis and AN [28, 29]. In addition, Lithium was introduced because of its mood-stabilising and neuroprotective properties. The antidepressant was not changed. The combination of medications reduced the intensity of hallucinations and high levels of distress, enabling her to engage in psychological therapy. She had a history of discontinuing antipsychotic medications owing to partial symptom relief and negative side effects. During treatment, she learned to identify early warning signs, such as thoughts and urges to be “uncontaminated by chemicals” or wanting “to be free from psycho-pharmaceuticals”, indicating that she was about to stop her medication. Techniques such as self-talk, reminders to take prescribed medications, and strategies to manage side effects all improved her compliance.

Social care needs

Social insecurities (e.g. housing and financial problems) can delay recovery. For several years, Lorna had no home beyond university or hospital, and the housing difficulties contributed to cycles of relapse. As part of the I-CBTE model, the MDT supported her in finding accommodation near her family which helped to facilitate sustainable discharge.

Education/employment

Treatment helped Lorna reverse her malnutrition, reduce self-harm and make progress on various maintaining factors including developing as a whole person separate from the ED. Exploring new career opportunities, however, was not a straightforward journey. There were setbacks including when Lorna fractured a hip and was severely incapacitated for a period of time. Engaging in education and work opportunities provided the foundations for a new recovery identity and ongoing health because she knew she had to be well to become and sustain the person she dreamed of being.

Care and treatment context

Unfortunately, systems of care can contribute to EDs becoming severe and chronic. Compared to admissions in previous SEDUs, Lorna’s prognosis improved significantly when she received treatment in the Oxford SEDU that promoted full weight restoration, offered in-house evidence-based treatments delivered by qualified clinicians for all comorbidities and seamlessly across the inpatient and community pathway. Unlike, previous admissions, she was treated by an MDT that believed, and had experienced, that patients could recover from an ED irrespective of severity, duration or complexity.

My presentation (in a previous SEDU) flummoxed my consultant, and all the medical team. They said I was “treatment resistant”, I needed “long-term hospitalisation”... They even talked about a need to keep me “sectioned for life” [1].

Challenges and breakthroughs

As in all treatments for patients with severe and longstanding EDs, there were challenges. Lorna’s recovery was not linear. Her psychological state, motivation and commitment to change fluctuated, and there was a severe self-harm incident, which delayed her discharge. The team approached this crisis as a setback and an opportunity to learn from.

Treating the ED in the context of a traumatic brain injury provided another layer of complexity. Her medical management and medication side effects were another challenge. Setbacks were expected and framed as learning opportunities for both the MDT and patient.

Alongside the challenges and consistency of 24/7 MDT inpatient care followed by seamless outpatient care for a year, there were important breakthroughs and turning points. We adopted Dalle Grave’s (personal communication) approach of SEDUs being ‘colleges of eating disorders’ where patients and staff are interested in learning together and sharing knowledge about the development, presentation and evidence-based treatment of EDs. Lorna’s cohort of patients was invited to join the staff for a presentation by an external speaker on the relapse rates of patients with and without full weight restoration. Listening to the research evidence helped her accept that weight restoration to a minimum BMI of 20 was necessary for staying well. Other key factors on the road to recovery were the seamless continuation of psychological therapy after discharge and rebuilding of her life and relationships.

Long-term outcomes

After being a ‘SEED patient’ for almost 20 years, the long-term outcomes for Lorna included no further hospitalisations since 2018. She has not self-harmed or made any suicide attempts and the ED remains in full remission. Her organic hallucinosis is managed by medication (Olanzapine, Aripiprazole, Lithium, Sertraline) for which she continues to receive outpatient psychiatric follow-up. She had a setback in 2023, following a cycling accident and another head injury, which temporarily exacerbated the hallucinations, but not the ED. Her weight is maintained within the healthy range (BMI, 22–23). As for her current level of functioning, she has fully engaged in life and leads a successful life as an artist, writer, filmmaker and a creative health researcher leading research projects about the brain, mental health and creativity. Similarly, Lyn and Mollie have maintained long-term remission and have successfully rebuilt their lives.

Discussion

This second linked paper illustrates the application of I-CBTE, using a real-life example of a patient who might have been categorised as having ‘SEED’, considered ‘too complex’, ‘treatment resistant’ and eligible for ‘palliative care’. Co-writing the two articles, with commentaries from Lyn who had SE-AN without complex comorbidities for more than 30 years (see Additional File 1) and Mollie, who had SE-AN for 12 years with 10 admissions and a subsequent diagnosis of autism (see Additional File 2), show that collaborating with individuals who have lived experiences provide a unique and insightful perspective on the recovery process even after many years of suffering and unsuccessful treatments. These case histories are consistent with previous findings that length of illness is not a predictor of poor outcomes, and that reversal of malnutrition is a key factor [8, 9, 30].

This case study complements our previous paper, which was the largest cohort study in the UK at the time of writing, involving 212 adults from 15 SEDUs. [9]. It was also the only study to compare treatment outcomes one year after discharge. Seventy percent of patients receiving I-CBTE achieved full remission, whereas less than 5% of TAU patients achieved full remission despite longer hospital stays. A 14.3% readmission rate in the I-CBTE group was significantly lower than that in the TAU group (~ 50%). Hay and Touyz’s definition would have categorised all patients receiving I-CBTE as SEED [31].

This case study illustrates the application of I-CBTE for a complex presentation and offers an in-depth analysis of the factors that contributed to a ‘SEED’ patient’s recovery, emphasising the importance of personalised and comprehensive biopsychosocial formulation and an MDT treatment approach. Lorna, Lyn and Mollie are three of the many patients who had positive outcomes in our study despite fitting the life-threatening SE-AN profile or, offering alternative case examples of the transformative benefits of this approach regardless of previous treatment failures, severity or duration of illness. Another example is a patient treated with I-CBTE who achieved full remission after more than 40 admissions, spanning 25 years.

Formulation-informed multidisciplinary treatment

The collaborative I-CBTE formulation is at the centre of the treatment [21, 32]. Every patient has a unique combination of maintaining factors and their proportional relevance is reflected in the formulation. Personalising the formulation diagram (Fig. 1) and co-writing the formulation encourages patients to become curious about the biopsychosocial maintaining factors of their eating difficulties and comorbidities. The formulation actively engages patients in their care, helps them to develop alternative coping skills to replace detrimental behaviours, and have a sense of ownership and agency. In this regard, see also Lyn and Mollie’s reflections on the crucial role of the formulation and the importance of learning new skills and ‘tools’ to replace harmful ways of coping (see Additional Files 1 & 2). Additionally, the formulation ensures continuity and consistency in the MDT’s understanding and treatment of the maintaining factors of each patient. This approach is also supported by recent meta-analyses that found personalization is an effective strategy to improve outcomes from psychological therapy [16, 17].

Body-image and overevaluation of weight and shape and control

Issues with body image and/or control are central features of EDs and addressing this is a key component of CBT for EDs [18]. Patients’ identity and self-evaluation could be disproportionately influenced by an overevaluation of the importance of their weight and shape, and its control, and culminate in varying experiences of feeling fat [33], body checking, body avoidance, and comparison making behaviours to the point where they marginalise other areas of their lives.

Dietary restriction and control of weight and shape is associated with an extreme need for control. Some patients have body-image difficulties, some have control issues, many have both. The relative importance of these maintaining factors will be unique and differ for example between neurodiverse patients, patients with avoidant restrictive food intake disorder or those who have experienced trauma. Consequently, issues with body-image and/or control require precise formulation-based interventions.

Dietary restriction and other weight control behaviours

The formulation and treatment plan must address the many reasons why patients attempt to restrict what they eat. Individual and group sessions offer psychoeducation and address dietary rules, reactions to rule-breaking and food avoidance [22]. Lorna’s case highlights too that food restriction and weight control behaviours were more than attempts to manage her weight or gain a sense of control, and that various other reasons (e.g. the need for self-destruction, to purify herself and gain a sense of achievement) had to be included in the formulation and treatment.

Malnutrition and secondary effects of being underweight

Low weight and malnutrition are key factors maintaining ED psychopathology in the transdiagnostic formulation of CBT for EDs [18]. Research has consistently shown that full weight restoration is crucial for recovery, long-term remission and weight stability [6–8, 34]. This was replicated in our study of 212 patients which showed that discharge BMI was a predictor of good outcomes alongside I-CBTE treatment, whereas age, severity, comorbidities, and length of illness were not [9]. In fact, unless malnutrition is addressed, patients remain entrenched in their disorder because of symptoms of malnourishment such as obsessive thoughts about food, rigid routines, and social withdrawal. Failure to achieve a healthy weight frequently results in relapse as demonstrated by Lorna’s lived experience.

Weight restoration is also the only way for the secondary psychological, physical, and social effects of malnutrition to go into remission and this is highlighted in Lyn’s reflections on the benefits of full weight restoration after being underweight for three decades. Her improved quality of life since recovery is reflected by her spending proportionally much more time on relationships, family, socialising and her interests/courses, versus on the eating disorder and her health. The proportional changes in weekly time spent on activities and preoccupations related to her health and the ED since recovery (5%), compared to when she had severe and longstanding anorexia nervosa (> 70%) are clearly illustrated in two pie charts (see Additional File 1). Similarly, the reversal of malnutrition was essential for improving Mollie’s quality of life, even though she found this very difficult with high level of anxiety during her treatment. This extreme weight related anxiety is a common reason for poor outcomes and need to be addressed in treatment. As our cases show, motivation to change improves during treatment. The risk of deterioration after discharge can be successfully managed by an integrated approach across the care pathway [9, 20]. Walsh et al. showed that the risk of deterioration is highest in the first 2–3 months after discharge, gradually tailoring down during the first year [35]. This is consistent with Dalle Grave’s recommendation of 7 weeks of intensive day treatment to help the maintenance of a healthy weight and ongoing outpatient psychological treatment to consolidate changes and support the patients rebuild their lives[20]. Our results replicated the importance of this gradual transition[9], and the lived experience testimonies in this paper highlight the importance of this.

Compensatory behaviours

Patients’ formulation and treatment need to identify and address any personal patterns of compensatory behaviours (e.g. purging, fasting, over-exercising), including their frequency and function. Learning and practising new non-harmful alternatives to purging and intense activity to manage emotions gave Lyn hope that ‘a different future was possible and achievable’ (See Additional File 1).

Mood intolerance and event-related eating

A focus on the role of emotional dysregulation or emotional overcontrol is key to the theoretical understanding of the development, maintenance and treatment of patients with EDs [25]. Similarly, a systematic review of comorbid PTSD with EDs found that maladaptive emotional regulation act as a mediating mechanism where ED behaviours enable the avoidance of trauma-related feelings and thoughts and reduce hyperarousal [36, 37] and is linked with higher rates of relapse. It is therefore crucial, to address emotional intolerance and dys/over-regulation, especially where this is associated with risk behaviours to self or others (e.g. through the use of DBT skills, etc.)

Perfectionism

The need to address clinical perfectionism in some patients with EDs was recognised by Fairburn [18], and have been confirmed in a recent systematic review and meta-analysis [38]. Perfectionism was a destructive maintaining factor in all three cases, that had to be addressed using CBT approaches [21, 22].

Low self-esteem and identity problems

Lorna exhibited several negative cognitive processes of a core low self-esteem that were addressed in individual and group I-CBTE sessions. Additionally, apart from low self-esteem, patients with EDs often struggle with a lack of identity separate from the ED and have negative core beliefs that require cognitive restructuring and the development of more functional core beliefs [39]. The notion of ‘becoming a butterfly’ as a new core self-belief and identity was a constant focus in therapy and encouraged by the nursing staff and between-session tasks (e.g. by asking: “What would the butterfly do in this situation?”). The development of a new identity and future, separate from the eating disorder, was equally important for Mollie and Lyn (see Additional Files 1 & 2).

Interpersonal difficulties

Longstanding EDs have a significant impact on families who may need support in their own right too. Interpersonal difficulties and family relationships can contribute to the development and maintenance of eating problems (see also Lyn and Mollie’s lived experiences in Additional Files 1 & 2). However, families and friends are increasingly seen as resources for recovery and involving families in treatment can improve outcomes [40–42]. Consequently, I-CBTE regards the involvement of families of adults, where possible, as important as the inclusion of families in the treatment of adolescents and children. Ideally, families need to be part of the recovery journey and co-evolve [43] with patients to maximise the likelihood of sustainable change.

Trauma

One of the main strengths of CBT for EDs is its focus on the here and now, with a future orientation. However, some patients with longstanding EDs requires therapy to consider their past unresolved traumas. For example, patients with symptoms of PTSD may have more severe ED presentations resulting in treatment dropout, symptom relapse, and poorer outcomes [37, 44]. Some patients with trauma histories purge or use laxatives ‘to feel clean’ or to get rid of the feeling of ‘having something in their body’. In these cases, the ED is unlikely to resolve without offering additional evidence-based treatment for trauma. Often, the most extreme trauma symptoms (including flashbacks, dissociation, and self-harm) can only be treated and managed in a safe hospital environment with a skilled MDT. Given that patients with trauma histories benefit from ED treatment, similarly to their unexposed peers, but are more likely to relapse, the trauma requires treatment in its own right [36]. Consequently, evidence-based therapy for trauma and trauma-informed care has to be integrated into the formulation and treatment. Further research is needed, but we concur with the views of clinicians and patients who favour an integrated approach rather than sequential diagnosis or parallel treatments for trauma and EDs in separate services [45]

Motivation to change and insight

Motivation to change is crucial in treating EDs, but standalone motivational interventions are insufficient to effectively improving ED psychopathology [46]. The relationship between motivation and maintenance factors is reciprocally dynamic. In I-CBTE, active patient involvement in formulating treatment goals and plans is crucial, focusing initially on the areas they are motivated to change, such as self-esteem and identity (including re-connecting with values, hopes, and dreams), addressing individual challenges, and improving interpersonal relationships [47]. Similarly, weight restoration, supportive psychoeducation, and dealing with cognitive inflexibility and body dissatisfaction can enhance motivation and insight into the need for change, which is illustrated by all three lived experience accounts. Mollie’s narrative also highlights the importance of clinicians ‘not giving up’ at times when patients are severely unwell, have lost all hope of getting better and ‘can’t fight for themselves’ (see Additional File 2). Her case also demonstrates that I-CBTE can be helpful for patients who are initially treated against their will.

Risks

Patients’ risk to themselves, others, and from others must be treated as a priority. The lifetime risk of self-harm in patients with AN is as high as 22% and even higher for patients with a history of suicide attempts. Patients with a history of ED admissions have a four-fold higher likelihood of subsequent independent admissions for self-harm [48, 49]. This mirrored Lorna’s presentation, who required multiple hospital treatments for self-injuries, either in its own right or during ED admissions. The high prevalence of self-harm and its positive correlation with attempted suicide means that the treatment of self-injury in patients should be a primary focus. I-CBTE provides a model for integrating such treatment based on a comprehensive formulation and management of all types of risk by the MDT. Lorna’s case demonstrates that full weight restoration is beneficial not only for physical health, but also for improving emotional regulation and reducing the risk of suicide. Sometimes compulsory treatment may be required to manage the risk but this should not exclude psychological treatment.

Medical and psychiatric comorbidities

The intractability and complexity of severe and longstanding EDs are not only due to illness duration or past failures [50, 51], but are also exacerbated by psychiatric and medical comorbidities [27]. Recent genetic studies elucidated the association between AN and a range of psychiatric disorders, including OCD, depression, and schizophrenia [52]. These discoveries highlight the need for effective treatment of any co-occurring disorders. In Lorna’s case, the long-term sequalae of TBI necessitated pharmacological treatment of her perceptual abnormalities, and this helped her access psychological treatment.

Some patients with severe and longstanding eating disorders have co-occurring (sometimes undiagnosed) autism. Being subsequently confirmed as autistic was a pivotal part of Mollie’s recovery journey (see Additional File 2). We recommend the early screening and identifying of patients with autism and to make adaptations to the evidence-based treatments as soon as neuro-diversity is suspected [53].

Social care needs

Social safety is a fundamental requirement for emotional wellbeing[54]. Social insecurities (e.g. financial or housing insecurities) increase stress and can delay recovery. For several years, Lorna’s housing difficulties contributed to cycles of relapse. A comprehensive treatment model therefore needs to take ‘a whole-person approach’ by improving patients’ overall general functioning including access to suitable housing and finding suitable education and employment. Addressing social care, as well as education and employment needs, require seamless MDT support across the care pathway.

Education/employment

Patients with SE-AN are more likely to be underemployed or unemployed [55] and chances of recovery increase with re-integration into the community and engaging in meaningful work and activities. Similarly, rebuilding one’s life after trauma and re-establishing adaptive functioning through education and work [26] are key components of trauma-focused CBT. The inpatient MDT supported Lorna in developing a new recovery identity that involved rethinking what career a ‘recovered Lorna’ wanted to have and this work continued with the community MDT. Lyn’s case demonstrates how work and employment can become a maintaining factor for the eating disorder and the importance of developing a healthy work-life balance (see Additional File 1), while Mollie’s case shows that education can help patients to develop new purpose and identity (see Additional File 2).

Care and treatment context

Systems of care can contribute to EDs becoming severe and chronic and should receive more attention in the literature. Patients with longstanding EDs are often trapped in care systems that are ill-equipped to treat them as our case study and Lyn and Mollie’s commentaries demonstrate (see Additional Files 1 & 2). These include service-level delays in diagnosis and treatment [56], poor inter-agency communication and working [10], a breakdown in the relationship between the patient and service, lack of clinician training, or ineffective treatments [15]. Lyn describes how negative experiences with her treatment team as a teenager ‘left her with a deep distrust of doctors’ and disengagement from services which lasted for the next 30 years (see Additional File 1). Many patients experience long waiting lists, underfunded and understaffed services, where patients may have to deteriorate to receive support [57], and a lack of research and funding for new treatments [2, 58]. Mollie’s recovery was delayed by professionals and treatment settings that were not equipped to offer her the individualised treatment that she needed. She required compulsory treatment which saved her life (see Additional File 2). In the context of discourses about ‘palliative care pathways’ Mollie, like Lorna’s, long-term survival rate could have been catastrophic if she had been treated by a different service and clinicians who might have believed it to be ethically inappropriate or too expensive to compulsory admit a patient for a 10th admission.

Prior to COVID-19, healthcare services in England and Scotland were only 15% funded to meet demand and referral rates [57]. Most services have limited MDTs and are unable to, adapt treatments for comorbidities, or ensure assertive outreach, with poor transitions between care settings. Unless care transitions are seamless, approximately 50% of patients relapse within a year of hospital discharge [9]. Our research has shown that if psychological and MDT treatments are delivered seamlessly across the care pathway relapse rates can be reduced to 15% and the majority of patients with SE-AN can achieve full remission. The pandemic presented a natural experiment, when this gradual transition was disrupted and the remission rates became much lower[9]. Seamless continuation of psychological treatment after discharge was key for all three patients (see Paper [1], Additional Files 1 & 2). However, Lyn’s experience shows that remote intensive support can be effective.

Contextual and diversity factors

Rather than applying the same approach to all patients, the formulation and treatment need to incorporate and adapt to the full range of human diversity, such as age, class, gender, race, religion, neurodiversity, sexual orientation, and socioeconomic status. Clinicians need to consider the social-economic context where factors such as soaring food and energy prices may hamper patients from adhering to a dietitian’s recommended meal plan. Similarly, undernourished patients may have higher energy bills because of being cold, which might increase financial pressures that maintain their EDs [59].

How I-CBTE can help patients with severe and enduring anorexia nervosa

I-CBTE offers a novel integrated approach which brings hope for patients with severe and longstanding eating disorders requiring intensive treatment. Implementing the model is not expensive but requires reviews of staffing mixes and training of all staff in the model. The insufficient number of psychologists in UK SEDUs is a major barrier to implementation. A summary of how I-CBTE can help patients with SE-AN is provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

How I-CBTE can help SE-AN patients

| Beneficial aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Intensive treatment | Patients with severe and longstanding EDs usually require intensive MDT inpatient treatment (including 1–2 individual therapy sessions per week & family sessions) |

| Personalised, collaborative & formulation-informed care | Personalised approaches are more effective and long-lasting. I-CBTE provides personalised psychiatric, psychological and social care treatment through collaboratively developed formulations, treatment goals and care plans. The flexible, non-judgmental approach focuses on all biopsychosocial factors, including past traumas, if they maintain the ED |

| Addressing motivation and insight | I-CBTE nurtures motivation as a dynamic process and addresses patient ambivalence throughout their treatment journey which enhances commitment to change. Collaboratively focusing on patients’ preferred treatment areas, boosts motivation and readiness to address other maintaining factors |

| Reversal of malnutrition | Weight restoration to a healthy weight is essential and achievable with I-CBTE. Discharge BMI predicts good outcomes, regardless of age, severity, comorbidities, or illness length |

| Comprehensive management of comorbidities | An integrative treatment approach for addressing the full spectrum of patients’ physical and mental health and social needs is essential to promote successful recovery trajectories [60]. Timings for interventions are collaboratively planned with patients and evidence-based treatments for psychiatric (e.g. PTSD) and medical comorbidities are integrated in the care plan |

| Inclusive | Including significant others such as friends and family as well as all relevant healthcare providers |

| Integrated MDT approach | MDT work is essential for severe and longstanding cases. Psychologists lead on the development of the formulation and offer evidence-based therapy for the ED and all co-morbidities. Dieticians, healthcare workers, and nurses address nutritional needs and support at mealtimes and encourage skills for coping and emotional regulation. Psychiatrists oversee the medical and psychiatric treatment of patients. Social workers may assist with deferral of studies, disability support and affordable housing |

| Seamless treatment across the care pathway and care systems | Seamless MDT care delivered across inpatient, day & community services and care systems, enhances treatment outcomes by providing continuity as patients transition through different phases of recovery and their lifespans |

Clinical implications

The I-CBTE model offers a comprehensive, personalised, and multidisciplinary approach to address severe and longstanding EDs. This model fosters a non-judgmental, collaborative treatment stance that prioritises patients’ strengths and interests and promotes resilience and autonomy. It integrates the work of the MDT and provides consistency across the patient’s recovery journey. Our service development and implementation of the I-CBTE model significantly improved recovery rates, and demonstrates long-term cost savings particularly for patients with complex conditions. For instance, Lorna, who had a severe and complex ED, has been admission-free for six years after completing treatment, saving the NHS approximately £360,000 in psychiatric admissions alone, not taking into account acute admissions and her improved quality of life. The magnitude of cost benefit is similar for Mollie too. Expanding the I-CBTE model could yield significant benefits not only for individuals but also for the NHS.

While there is a lack of RCT evidence supporting the integration of I-CBTE into intensive services, it is worth noting that no adult inpatient treatment model has undergone testing in RCTs. This is due to the high risk and complex patient population. Dalle Grave conducted a comparison between two versions of inpatient CBT for ED in a single centre trial [22], while our previous study in real-life settings examined the outcomes of I-CBTE in comparison to 15 SEDUs in the UK [9]. In addition, the model aligns perfectly with the established best practice guidelines in the UK [3, 60, 61].

Recommendations for implementing I-CBTE

I-CBTE provides a holistic and personalised treatment and the whole-person approach is essential for addressing the psychological, social, and medical aspects of care concurrently and tailored to each patient’s unique formulation, needs and preferences. All MDT members should be trained in I-CBTE principles using treatment manuals and online resources where appropriate. Ongoing supervision is essential for maintaining high treatment fidelity and effectiveness and aligning the team’s approach to patient care. Commissioners and service managers need to ensure appropriate staffing by transitioning from unqualified staff to qualified professionals to support the effective and sustainable implementation of the I-CBTE model. This will ensure high-quality, evidence-based care and improved patient outcomes. Co-production with patients with lived experiences will help to increase knowledge in the ED field, and improve quality, treatment and services for patients with severe and longstanding EDs and improve outcomes. Finally, integrated, evidence-based treatment must be delivered seamlessly across various treatment settings and care pathways to ensure consistent, coordinated and continues care throughout the patient’s treatment journey.

Future directions

Future research should investigate the long-term effectiveness of I-CBTE through longitudinal studies across diverse populations and explore remote technologies for intensive support as opposed to in-person day hospitals. Patient feedback on experiences of integrated models of care is important and this is also needed for I-CBTE. In addition, systematic health economics studies should be conducted.

In conclusion, the use of I-CBTE in treating SE-AN demonstrates significant promise, challenging the notion of intractability that is often associated with severe and longstanding EDs. This case study not only highlights the potential for recovery but also provides a comprehensive model for enhancing existing treatment frameworks to better serve this complex patient population. We conclude with Lorna’s words:

My story of recovery from a SEED demonstrates that it is possible to recover from a highly complex illness and live a meaningful, successful life, against all the odds... I became a butterfly: I grew from being the cumbersome caterpillar, locked into their cramped cocoon, into a beautiful being with wings, who can fly wherever she wishes. In other words, I did get better, thanks to eventually finding the treatment model that tuned into my strengths and allowed me to build a brand-new version of myself; that home-made miracle: recovery [1].

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We thank the multidisciplinary team at Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust who helped implement I-CBTE.

Author contributions

DV proposed the idea for the manuscripts, AA and DV conducted the literature review DV and AA wrote the first draft, reviewed and edited the manuscript. These two authors equally contributed. LC provided lived experience input and authored the first linked paper. LR & MT provided lived experience commentaries in the supplementary section to illustrate different clinical presentations and lived experiences. All authors contributed to the revision of the manuscript and approved the final version.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

None required.

Consent for publication

The case study that is presented is that of co-author LC who has freely consented to contribute her lived experience expertise and personal journey to the paper. Similarly, co-authors, LR and MT, have freely consented to sharing their lived experience expertise and journeys in the Additional Files 1 & 2 respectively.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Collins L. Applying integrated enhanced cognitive behaviour Therapy (I-CBTE) to Severe and Longstanding Eating Disorders (SEED) Paper 1: I am no longer a SEED patient. J Eat Disord. 2024;12(1):139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Downs J, Ayton A, Collins L, Baker S, Missen H, Ibrahim A. Untreatable or unable to treat? Creating more effective and accessible treatment for long-standing and severe eating disorders. Lancet Psychiatry. 2023;10(2):146–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: Eating disorders: recognition and treatment. NG69. In. London, UK: NICE; 2017 [PubMed]

- 4.Goddard E, Hibbs R, Raenker S, Salerno L, Arcelus J, Boughton N, Connan F, Goss K, Laszlo B, Morgan J, et al. A multi-centre cohort study of short term outcomes of hospital treatment for anorexia nervosa in the UK. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morris J, Simpson AV, Voy SJ. Length of stay of inpatients with eating disorders. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2015;22(1):45–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maurel L, MacKean M, Lacey JH. Factors predicting long-term weight maintenance in anorexia nervosa: a systematic review. Eat Weight Disord. 2024;29(1):24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frostad S, Rozakou-Soumalia N, Darvariu S, Foruzesh B, Azkia H, Larsen MP, Rowshandel E, Sjogren JM. BMI at discharge from treatment predicts relapse in Anorexia Nervosa: a systematic scoping review. J Pers Med. 2022;12(5):836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Redgrave GW, Schreyer CC, Coughlin JW, Fischer LK, Pletch A, Guarda AS. Discharge body mass index, not illness chronicity, predicts 6-month weight outcome in patients hospitalized With Anorexia Nervosa. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12: 641861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ibrahim A, Ryan S, Viljoen D, Tutisani E, Gardner L, Collins L, Ayton A. Integrated enhanced cognitive behavioural (I-CBTE) therapy significantly improves effectiveness of inpatient treatment of anorexia nervosa in real life settings. J Eat Disord. 2022;10(1):98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reay M, Holliday J, Stewart J, Adams J. Creating a care pathway for patients with longstanding, complex eating disorders. J Eat Disord. 2022;10(1):128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Birch E, Downs J, Ayton A. Harm reduction in severe and long-standing Anorexia Nervosa: part of the journey but not the destination—a narrative review with lived experience. J Eat Disord. 2024;12(1):140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Broomfield C, Noetel M, Stedal K, Hay P, Touyz S. Establishing consensus for labeling and defining the later stage of anorexia nervosa: a Delphi study. Int J Eat Disord. 2021;54(10):1865–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dalle Grave R. Severe and enduring anorexia nervosa: No easy solutions. Int J Eat Disord. 2020;53(8):1320–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Downs J. Care pathways for longstanding eating disorders must offer paths to recovery, not managed decline. BJPsych Bull. 2023;48:177–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhu J, Hay PJ, Yang Y, Le Grange D, Lacey JH, Lujic S, Smith C, Touyz S. Specific psychological therapies versus other therapies or no treatment for severe and enduring anorexia nervosa. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2023;8(8):011570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harnas SJ, Knoop H, Sprangers MAG, Braamse AMJ. Defining and operationalizing personalized psychological treatment – a systematic literature review. Cognit Behav Ther. 2024. 10.1080/16506073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nye A, Delgadillo J, Barkham M. Efficacy of personalized psychological interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2023;91(7):389–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Shafran R. Cognitive behaviour therapy for eating disorders: a “transdiagnostic” theory and treatment. Behav Res Ther. 2003;41(5):509–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fairburn CG, Jones R, Peveler RC, Hope RA, O’Connor M. Psychotherapy and bulimia nervosa. Longer-term effects of interpersonal psychotherapy, behavior therapy, and cognitive behavior therapy. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50(6):419–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dalle Grave R. Multistep cognitive behavioral therapy for eating disorders. Plymouth: Jason Aronson; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dalle Grave R, Sartirana M, Calugi S. Complex cases and comorbidity in eating disorders. Berlin: Springer; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dalle Grave R, Calugi S, Conti M, Doll H, Fairburn CG. Inpatient cognitive behaviour therapy for anorexia nervosa: a randomized controlled trial. Psychother Psychosom. 2013;82(6):390–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yim SH, Jones R, Cooper M, Roberts L, Viljoen D. Patients’ experiences of clinical team meetings (ward rounds) at an adult in-patient eating disorders ward: mixed-method service improvement project. BJPsych Bull. 2023;47(6):316–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.NHS Standard Contract for Specialised Eating Disorders (adults) [https://www.england.nhs.uk/commissioning/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/2014/12/c01-spec-eat-dis-1214.pdf]

- 25.Linardon J, Fairburn CG, Fitzsimmons-Craft EE, Wilfley DE, Brennan L. The empirical status of the third-wave behaviour therapies for the treatment of eating disorders: a systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2017;58:125–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: Post-traumatic stress disorder. In; 2018. [PubMed]

- 27.Hambleton A, Pepin G, Le A, Maloney D. National Eating Disorder Research C, Touyz S, Maguire S: Psychiatric and medical comorbidities of eating disorders: findings from a rapid review of the literature. J Eat Disord. 2022;10(1):132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Han R, Bian Q, Chen H. Effectiveness of olanzapine in the treatment of anorexia nervosa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav. 2022;12(2): e2498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Phyland RK, McKay A, Olver J, Walterfang M, Hopwood M, Ponsford M, Ponsford JL. Use of olanzapine to treat agitation in traumatic brain injury: a series of n-of-one trials. J Neurotrauma. 2023;40(1–2):33–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Calugi S, El Ghoch M, Dalle Grave R. Intensive enhanced cognitive behavioural therapy for severe and enduring anorexia nervosa: a longitudinal outcome study. Behav Res Ther. 2017;89:41–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hay P, Touyz S. Classification challenges in the field of eating disorders: can severe and enduring anorexia nervosa be better defined? J Eat Disord. 2018;6:41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fairburn CG. Cognitive behavior therapy and eating disorders. Guilford: Guilford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Major L, Viljoen D, Nel P. The experience of feeling fat for women with anorexia nervosa: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. Eur J Psychother Counsell. 2019;21(1):52–67. [Google Scholar]

- 34.El Ghoch M, Calugi S, Chignola E, Bazzani PV, Dalle Grave R. Body fat and menstrual resumption in adult females with anorexia nervosa: a 1-year longitudinal study. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2016;29(5):662–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Walsh BT, Xu T, Wang Y, Attia E, Kaplan AS. Time course of relapse following acute treatment for Anorexia Nervosa. Am J Psychiatry. 2021;178(9):848–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Convertino AD, Mendoza RR. Posttraumatic stress disorder, traumatic events, and longitudinal eating disorder treatment outcomes: a systematic review. Int J Eat Disord. 2023;56(6):1055–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Day S, Hay P, Tannous WK, Fatt SJ, Mitchison D. A systematic review of the effect of PTSD and trauma on treatment outcomes for eating disorders. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2023;25(2):947–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stackpole R, Greene D, Bills E, Egan SJ. The association between eating disorders and perfectionism in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eat Behav. 2023;50: 101769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Conti JE, Joyce C, Hay P, Meade T. “Finding my own identity”: a qualitative metasynthesis of adult anorexia nervosa treatment experiences. BMC Psychol. 2020;8(1):110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dalle Grave R, Sartirana M, Sermattei S, Calugi S. Treatment of eating disorders in adults versus adolescents: similarities and differences. Clin Ther. 2021;43(1):70–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]