Abstract

Background

Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) are rare neoplasms that originate from peptidergic neurons and neuroendocrine cells. Due to their increasing incidence, effective treatment strategies are required. Surufatinib, a novel small-molecule inhibitor with antiangiogenic and immunomodulatory effects, has shown promise in clinical trials for advanced NETs. However, the efficacy and safety of surufatinib are influenced by multiple factors, and there is currently a lack of sufficient real-world studies to explore these potential influencing factors.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective study on 133 patients with NETs who were treated with surufatinib at Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center. Patients were histologically confirmed to have primary NETs. Statistical analyses, including Cox regression models and Kaplan-Meier curves, were conducted to assess the impact of the primary tumor site on progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS).

Results

Patients with gastroenteropancreatic NETs (GEP-NETs) exhibited significantly longer PFS and OS compared to extraGEP-NETs patients. Subgroup analyses also revealed variations in survival outcomes among patients with liver metastases depending on the primary tumor site. Adverse events (AEs), including proteinuria and increased bilirubin, were more common in GEP-NETs patients. These findings emphasize the importance of considering primary tumor site in treatment decisions for NETs.

Conclusions

Primary tumor site is a critical factor influencing the efficacy of surufatinib in NETs. Clinicians should consider this factor when determining treatment strategies.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12885-024-13089-6.

Keywords: GEP-NETs, Surufatinib, Primary tumor site, Efficacy

Introduction

Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) are rare tumors originating from neuroendocrine cells and peptidergic neurons, expressing neuroendocrine markers, and capable of producing biologically active amines and/or peptides [1]. Both domestic and international research data indicate a continuous increase in the incidence of NETs, which exhibit a more significant increasing trend compared with other types of tumors. The incidence of NETs in the United States increased 6.4-fold between 1973 and 2012, reaching 6.98 per 100,000 person-years [2]. NETs can occur throughout the body, with gastroenteropancreatic NETs (GEP-NETs) being the most common, followed by those in the lungs and other sites [3]. NETs in different locations exhibit high heterogeneity, making the diagnosis and treatment of these tumors complex [4].

Surgical resection is the primary treatment method for localized NETs, but most patients present with distant metastases at diagnosis, and systemic therapy is necessary for these patients [5]. The main drugs used for systemic treatment of NETs include somatostatin analogues (SSAs), sunitinib, everolimus (a mTOR inhibitor), and chemotherapy [5–7]. Additionally, due to the high expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in NETs and the rich vascular composition of the tumor microenvironment, this provides a basis for the use of antiangiogenetic treatment in NETs [8, 9].

A novel small-molecule inhibitor, surufatinib, acts by targeting VEGF receptors-1 (VEGFR-1), VEGFR-2, VEGFR-3, fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) 1 and macrophage colony stimulating factor 1 (CSF1) receptor, exerting antiangiogenic and immunomodulatory effects [10, 11]. This dual mechanism of action may enhance the antitumor efficacy of surufatinib [12]. SANET-p, a phase III clinical trial conducted in patients with advanced, progressive, well-differentiated pancreatic NETs showed that surufatinib significantly prolonged patients’ progression-free survival (PFS) compared to the placebo group (10.9 versus 3.7 months; p = 0.0011), with approximately 84% of patients experiencing tumor regression benefits [8]. SANET-ep, another study evaluated surufatinib treatment in a phase III clinical trial for G1/G2 grade advanced non-pancreatic NETs patients, demonstrating that surufatinib significantly prolonged median PFS compared to placebo (9.2 months versus 3.8 months) with a favourable safety profile and a high degree of patient tolerability [13]. Based on the results of these two studies, surufatinib has been approved by the China National Medical Products Administration for the treatment of advanced NETs patients [14].

However, in clinical practice, due to the high heterogeneity of NETs, only 10-20% of patients had a partial response (PR) or complete response (CR) to surufatinib [8, 13]. Exploring clinical factors that may affect the efficacy of surufatinib is crucial. Therefore, we initiated a real-world retrospective study aimed at evaluating whether NETs originating from different primary sites would affect the efficacy of surufatinib.

Methods

Participants and eligibility

This retrospective study was conducted on patients with NETs who received treatment with surufatinib at Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center from December 2015 to November 2023. All patients had histologically confirmed primary NETs. A total of 133 patients were included in the study after excluding those with multiple primary tumors (≥ 2) and those with missing data on TNM staging, grade, treatment, pathological, laboratory, and survival data.

Follow-up work ended on January 31, 2024. The study received approval from the Institutional Review Board of the Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center.

Data collection

The hospital records and medical examination results of these patients were retrospectively reviewed. Data for each patient included age at diagnosis, sex, family history, T-N-M stage, sites of metastasis, number of organs involved, grade, primary tumor site, recurrence status, levels of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), alanine transaminase (ALT), C-reactive protein (CRP), aspartate transaminase (AST), creatinine (CRE), Ki67, prior antitumor therapies such as chemotherapy, everolimus, surgery, radiotherapy, somatostatin analogues (SSA), immunotherapy, whether combination therapy was used, number of lines treated with surufatinib, adverse events (AEs), imaging evaluation results, date of starting surufatinib treatment, date of progression, and death. In addition, we calculated lactate dehydrogenase-to-albumin ratio (LAR), systemic inflammatory response index (SIRI), platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), prognostic nutritional index (PNI), neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), and systemic immune inflammation index (SII) based on the patients’ routine blood and biochemical examination results. Details regarding the calculation methods of these indicators were provided in the Supplementary Material. The medical examination results of the patients were generally acquired within two weeks preceding the initiation of surufatinib treatment.

Outcome Assessment

The primary endpoint of our study was PFS, which is defined as the time from the start of surufatinib treatment to either disease progression or death from any cause, whichever comes first. The secondary study endpoints included overall survival (OS), disease control rate (DCR), objective response rate (ORR), and AEs. OS was defined as the duration from disease diagnosis to death from any cause. ORR was defined as the proportion of patients who achieved CR or PR based on diagnosis. DCR was defined as the proportion of patients who achieved CR, PR, or stable disease (SD) based on diagnosis. Response assessment was evaluated using RECIST version 1.1, and toxicity was graded according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 5.0.

Statistical analysis

The Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the clinical and demographic characteristics as well as other categorical variables between patients with GEP-NETs and those with NETs originating from other primary sites (extraGEP-NETs). Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression models were employed to estimate the risk of disease progression or death. Survival curves were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and differences between the curves were assessed by log-rank test. All statistical tests were two-sided, and a p-value below 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. IBM SPSS 25.0 and R software version 4.2.1 were utilized for conducting the statistical analyses.

Results

Overview of patient characteristics

Baseline characteristics of NETs patients from different primary tumor sites are presented in Tables 1 and 2. The gender distribution between GEP-NETs and extraGEP-NETs groups was comparable, with a predominance of males over females in both groups. The median age for patients in both groups was 50 years. Approximately half of the patients presented without lymph node metastasis at diagnosis, while the majority exhibited distant metastasis (74.7% vs. 71.4%). In the GEP-NETs group, 65.9% of patients were classified as G2, with G1 and G3 accounting for 12.1% and 22.0%, respectively. In contrast, the extraGEP-NETs group had a higher proportion of G3 patients (59.5%) compared to G2 (31.0%) and G1 (9.5%) patients. The distribution of ki67 in patients was similar to grade. Approximately 28.6% and 21.4% of patients in the respective groups experienced tumor recurrence. The majority of patients exhibited normal levels of ALT, AST, LDH, and CRE before receiving surufatinib treatment. In the GEP-NETs group, patients received chemotherapy, everolimus, surgery, radiotherapy, SSA, and immunotherapy at the rates of 39.6%, 27.5%, 38.5%, 9.9%, 31.9%, and 8.8%, respectively. The corresponding rates for the extraGEP-NETs group were 35.7%, 11.9%, 28.6%, 14.3%, 9.5%, and 11.9%, respectively. Surufatinib monotherapy was predominantly utilized in both groups, while combination therapy included surufatinib combined with chemotherapy, immunotherapy, or both. Among all NETs patients receiving surufatinib treatment, the median LAR was 5.78. Patients were stratified into LAR high and LAR low groups based on the median, with proportions detailed in Table 2. Similar grouping methods were applied to PLR, NLR, PNI, SII, SIRI, and other indicators.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients

| Overall (N = 133) |

GEP-NETs (N = 91) |

ExtraGEP-NETsa (N = 42) |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.671 | |||

| 0 | 41 (30.8%) | 27 (29.7%) | 14 (33.3%) | |

| 1 | 92 (69.2%) | 64 (70.3%) | 28 (66.7%) | |

| Age | 0.042 | |||

| < 65 | 116 (87.2%) | 83 (91.2%) | 33 (78.6%) | |

| ≥ 65 | 17 (12.8%) | 8 (8.8%) | 9 (21.4%) | |

| Family History | 0.207 | |||

| 0 | 115 (86.5%) | 81 (89.0%) | 34 (81.0%) | |

| 1 | 18 (13.5%) | 10 (11.0%) | 8 (19.0%) | |

| T | 0.817 | |||

| 1/2 | 43 (32.3%) | 30 (33.0%) | 13 (31.0%) | |

| 3/4 | 90 (67.7%) | 61 (67.0%) | 29 (69.0%) | |

| N | 0.569 | |||

| 0 | 65 (48.9%) | 46 (50.5%) | 19 (45.2%) | |

| 1 | 68 (51.1%) | 45 (49.5%) | 23 (54.8%) | |

| M | 0.688 | |||

| 0 | 35 (26.3%) | 23 (25.3%) | 12 (28.6%) | |

| 1 | 98 (73.7%) | 68 (74.7%) | 30 (71.4%) | |

| Number of organs involved | 0.206 | |||

| > 2 | 59 (44.4%) | 37 (40.7%) | 22 (52.4%) | |

| ≤ 2 | 74 (55.6%) | 54 (59.3%) | 20 (47.6%) | |

| Grade | < 0.001 | |||

| G1 | 15 (11.3%) | 11 (12.1%) | 4 (9.5%) | |

| G2 | 73 (54.9%) | 60 (65.9%) | 13 (31.0%) | |

| G3 | 45 (33.8%) | 20 (22.0%) | 25 (59.5%) | |

| Recurrence | 0.385 | |||

| 0 | 98 (73.7%) | 65 (71.4%) | 33 (78.6%) | |

| 1 | 35 (26.3%) | 26 (28.6%) | 9 (21.4%) | |

Abbreviations GEP, gastroenteropancreatic; NET, neuroendocrine tumors

ExtraGEP-NETsa: NETs originated in biliary system, lung, peritoneum, abdominal cavity, liver, uterus and cervix, larynx, thyroid, pelvis, kidneys, adrenal glands, head and neck, thymus and mediastinum

Table 2.

Baseline laboratory outcomes and treatment information of patients

| Overall (N = 133) |

GEP-NETs (N = 91) |

ExtraGEP-NETsa (N = 42) |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LDH | 0.042 | |||

| < 250 | 111 (83.5%) | 80 (87.9%) | 31 (73.8%) | |

| ≥ 250 | 22 (16.5%) | 11 (12.1%) | 11 (26.2%) | |

| CRP | 0.693 | |||

| < 3 | 73 (54.9%) | 51 (56.0%) | 22 (52.4%) | |

| ≥ 3 | 60 (45.1%) | 40 (44.0%) | 20 (47.6%) | |

| ALT | 0.724 | |||

| < 40 | 116 (87.2%) | 80 (87.9%) | 36 (85.7%) | |

| ≥ 40 | 17 (12.8%) | 11 (12.1%) | 6 (14.3%) | |

| AST | 0.716 | |||

| < 35 | 110 (82.7%) | 76 (83.5%) | 34 (81.0%) | |

| ≥ 35 | 23 (17.3%) | 15 (16.5%) | 8 (19.0%) | |

| CRE | 0.409 | |||

| < 73 | 95 (71.4%) | 67 (73.6%) | 28 (66.7%) | |

| ≥ 73 | 38 (28.6%) | 24 (26.4%) | 14 (33.3%) | |

| Ki67 | < 0.001 | |||

| < 3 | 15 (11.3%) | 11 (12.1%) | 4 (9.5%) | |

| > 20 | 45 (33.8%) | 20 (22.0%) | 25 (59.5%) | |

| 3–20 | 73 (54.9%) | 60 (65.9%) | 13 (31.0%) | |

| LAR | 0.315 | |||

| ≤ 5.8 | 108 (81.2%) | 76 (83.5%) | 32 (76.2%) | |

| > 5.8 | 25 (18.8%) | 15 (16.5%) | 10 (23.8%) | |

| PLR | 0.974 | |||

| ≤ 340.6 | 120 (90.2%) | 82 (90.1%) | 38 (90.5%) | |

| > 340.6 | 13 (9.8%) | 9 (9.9%) | 4 (9.5%) | |

| NLR | 0.752 | |||

| ≤ 6.2 | 121 (91.0%) | 82 (90.1%) | 39 (92.9%) | |

| > 6.2 | 12 (9.0%) | 9 (9.9%) | 3 (7.1%) | |

| PNI | 0.179 | |||

| ≤ 58.1 | 115 (86.5%) | 76 (83.5%) | 39 (92.9%) | |

| > 58.1 | 18 (13.5%) | 15 (16.5%) | 3 (7.1%) | |

| SII | 0.838 | |||

| ≤ 1080.9 | 109 (82.0%) | 75 (82.4%) | 34 (81.0%) | |

| > 1080.9 | 24 (18.0%) | 16 (17.6%) | 8 (19.0%) | |

| SIRI | 0.747 | |||

| ≤ 2.5 | 112 (84.2%) | 76 (83.5%) | 36 (85.7%) | |

| > 2.5 | 21 (15.8%) | 15 (16.5%) | 6 (14.3%) | |

| Treatment b | ||||

| Chemotherapy | 51 (38.3%) | 36 (39.6%) | 15 (35.7%) | 0.672 |

| Everolimus | 30 (22.6%) | 25 (27.5%) | 5 (11.9%) | 0.046 |

| Surgery | 47 (35.3%) | 35 (38.5%) | 12 (28.6%) | 0.267 |

| Radiotherapy | 15 (11.3%) | 9 (9.9%) | 6 (14.3%) | 0.456 |

| SSA | 33 (24.8%) | 29 (31.9%) | 4 (9.5%) | 0.005 |

| Immunotherapy | 13 (9.8%) | 8 (8.8%) | 5 (11.9%) | 0.574 |

| Treatment c | ||||

| Monotherapy | 82 (61.7%) | 57 (62.6%) | 25 (59.5%) | 0.731 |

| Combined chemotherapy | 30 (22.6%) | 21 (23.1%) | 9 (21.4%) | 0.833 |

| Combined immunotherapy | 11 (8.3%) | 10 (11.0%) | 1 (2.4%) | 0.172 |

| Combined chemotherapy and immunotherapy | 10 (7.5%) | 3 (3.3%) | 7 (16.7%) | 0.011 |

| Treatment lines | 0.131 | |||

| First line | 39 (29.3%) | 23 (25.3%) | 16 (38.1%) | |

| ≥ Second line | 94 (70.7%) | 68 (74.7%) | 26 (61.9%) |

Abbreviations GEP, gastroenteropancreatic; NET, neuroendocrine tumors; SSA, somatostatin analogues; LAR, lactate dehydrogenase-to-albumin ratio; PLR, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio; NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; PNI, prognostic nutritional index; SII, systemic immune inflammation index; SIRI, systemic inflammatory response index

ExtraGEP-NETsa: NETs originated in biliary system, lung, peritoneum, abdominal cavity, liver, uterus and cervix, larynx, thyroid, pelvis, kidneys, adrenal glands, head and neck, thymus and mediastinum. Treatmentb: treatment prior to surufatinib; Treatmentc: initiation of treatment with surufatinib

Association between primary tumor sites and survival

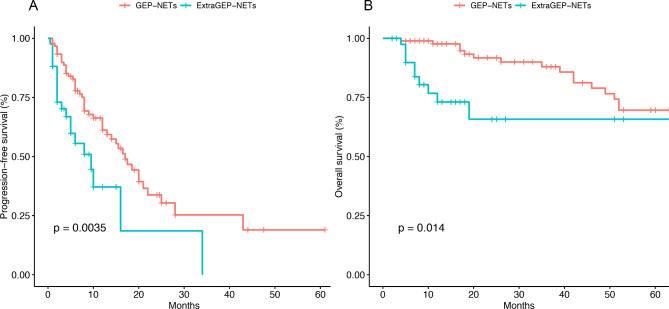

The median follow-up time for patients was 22.1 months. The relationship between the clinical characteristics of patients with NETs and PFS was analyzed. Univariate Cox regression analysis identified that family history, grade, primary tumor site, Ki67, PLR, and NLR significantly impacted patients’ PFS. Incorporating these factors into a multivariate Cox regression analysis showed that, except for NLR, family history, grade, primary tumor site, Ki67, and PLR were also significant predictors of worse PFS (Table 3). Specifically, family history, primary tumor site, PLR, and G3 (Ki67 > 20) were statistically significant, while G2 (Ki67 range 3–20) was not. The median PFS for patients in the GEP-NETs group and extraGEP-NETs group were 9 months and 3.8 months, respectively. The 6-month and 1-year PFS rates for GEP-NETs group patients were 77.8% and 61.2%, respectively (Fig. 1A). For patients in the extraGEP-NETs group, the 6-month and 1-year PFS rates were 55.5% and 37.1%, respectively (Fig. 1A).

Table 3.

Univariate analysis and multivariate analysis of PFS

| Characteristics | Univariate analysis HR (95% CI) |

P | Multivariate analysis HR (95% CI) |

P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.052 | |||

| 0 | 1 | |||

| 1 | 1.80 (0.96, 3.37) | |||

| Age | 0.597 | |||

| < 65 | 1 | |||

| ≥ 65 | 1.23 (0.58, 2.58) | |||

| Family History | 0.007 | |||

| 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 1 | 2.50 (1.35, 4.62) | 2.50 (1.31, 4.60) | 0.005 | |

| T | 0.145 | |||

| 1/2 | 1 | |||

| 3/4 | 1.51 (0.85, 2.70) | |||

| N | 0.099 | |||

| 0 | 1 | |||

| 1 | 1.52 (0.92, 2.52) | |||

| M | 0.278 | |||

| 0 | 1 | |||

| 1 | 1.36 (0.77, 2.43) | |||

| Number of organs involved | 0.398 | |||

| > 2 | 1 | |||

| ≤ 2 | 0.81 (0.49, 1.33) | |||

| Grade | 0.001 | |||

| G1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| G2 | 1.12 (0.49, 2.56) | 1.50 (0.64, 3.50) | 0.350 | |

| G3 | 4.93 (2.03, 11.94) | 5.20 (2.12, 12.8) | 0.001 | |

| Primary site | 0.006 | |||

| GEP-NETs | 1 | 1 | ||

| ExtraGEP-NETsa | 2.21 (1.29, 3.79) | 2.10 (1.15, 3.90) | 0.015 | |

| Recurrence | 0.602 | |||

| 0 | 1 | |||

| 1 | 1.15 (0.67, 1.99) | |||

| LDH | 0.116 | |||

| < 250 | 1 | |||

| ≥ 250 | 1.75 (0.91, 3.38) | |||

| CRP | 0.376 | |||

| < 3 | 1 | |||

| ≥ 3 | 1.25 (0.76, 2.04) | |||

| ALT | 0.413 | |||

| < 40 | 1 | |||

| ≥ 40 | 1.34 (0.68, 2.64) | |||

| AST | 0.977 | |||

| < 35 | 1 | |||

| ≥ 35 | 1.01 (0.54, 1.90) | |||

| CRE | 0.559 | |||

| < 73 | 1 | |||

| ≥ 73 | 1.17 (0.70, 1.96) | |||

| Ki67 | 0.001 | |||

| < 3 | 1 | 1 | ||

| > 20 | 4.93 (2.03, 11.94) | 5.20 (2.12, 12.80) | 0.001 | |

| 3–20 | 1.12 (0.49, 2.56) | 1.50 (0.64, 3.50) | 0.350 | |

| Chemotherapy | 0.466 | |||

| 0 | 1 | |||

| 1 | 1.20 (0.73, 1.98) | |||

| Everolimus | 0.130 | |||

| 0 | 1 | |||

| 1 | 1.55 (0.89, 2.70) | |||

| Surgery | 0.648 | |||

| 0 | 1 | |||

| 1 | 0.89 (0.54, 1.48) | |||

| Radiotherapy | 0.978 | |||

| 0 | 1 | |||

| 1 | 0.99 (0.47, 2.08) | |||

| SSA | 0.313 | |||

| 0 | 1 | |||

| 1 | 0.75 (0.43, 1.32) | |||

| Immunotherapy | 0.142 | |||

| 0 | 1 | |||

| 1 | 1.91 (0.86, 4.24) | |||

| Treatment c | 0.080 | |||

| Monotherapy | 1 | |||

| Combined chemotherapy | 0.46 (0.21, 1.01) | |||

| Combined immunotherapy | 1.10 (0.39, 3.09) | |||

| Combined chemotherapy and immunotherapy | 1.72 (0.73, 4.05) | |||

| Treatment lines | 0.696 | |||

| First line | 1 | |||

| ≥ Second line | 1.118 (0.634,1.971) | |||

| LAR | 0.163 | |||

| ≤ 5.8 | 1 | |||

| > 5.8 | 1.55 (0.86, 2.81) | |||

| PLR | 0.001 | |||

| ≤ 340.6 | 1 | 1 | ||

| > 340.6 | 5.36 (2.50, 11.5) | 3.30 (1.19, 9.20) | 0.022 | |

| NLR | 0.007 | |||

| ≤ 6.2 | 1 | 1 | ||

| > 6.2 | 3.01 (1.47, 6.15) | 1.70 (0.64, 4.50) | 0.284 | |

| PNI | 0.821 | |||

| ≤ 58.1 | 1 | |||

| > 58.1 | 0.93 (0.47,1.83) | |||

| SII | 0.925 | |||

| ≤ 1080.9 | 1 | |||

| > 1080.9 | 0.97 (0.50, 1.87) | |||

| SIRI | 0.464 | |||

| ≤ 2.5 | 1 | |||

| > 2.5 | 1.27 (0.68, 2.38) |

Abbreviations GEP, gastroenteropancreatic; NET, neuroendocrine tumors; SSA, somatostatin analogues; LAR, lactate dehydrogenase-to-albumin ratio; PLR, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio; NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; PNI, prognostic nutritional index; SII, systemic immune inflammation index; SIRI, systemic inflammatory response index

ExtraGEP-NETsa: NETs originated in biliary system, lung, peritoneum, abdominal cavity, liver, uterus and cervix, larynx, thyroid, pelvis, kidneys, adrenal glands, head and neck, thymus and mediastinum. Treatmentc: initiation of treatment with surufatinib

Fig. 1.

Progression-free survival (A) and overall survival (B) analysis of patients with GEP-NETs and extraGEP-NETs

Furthermore, we analyzed the impact of clinical characteristics of NETs patients on OS.

Univariate analysis revealed that N stage, M stage, number of organs involved, grade, primary site, recurrence, ALT, AST, Ki67, surgery, and PLR influenced OS with statistical significance. While multivariate analysis showed that G3 (Ki67 > 20), tumor primary site, recurrence, and PLR are independent prognostic factors for OS and have significant statistical significance (Table 4). Similarly, in the multivariate analysis, G2 (Ki67 range 3–20) did not show significant statistical significance. The 6-month and 1-year OS rates for patients in the GEP-NETs group were 98.9% and 97.6%, respectively (Fig. 1B). For patients in the extraGEP-NETs group, the 6-month and 1-year OS rates were 89.7% and 79.1%, respectively (Fig. 1B).

Table 4.

Univariate analysis and multivariate analysis of OS

| Characteristics | Univariate analysis HR (95% CI) |

P | Multivariate analysis HR (95% CI) |

P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.128 | |||

| 0 | 1 | |||

| 1 | 0.56 (0.27, 1.16) | |||

| Age | 0.670 | |||

| < 65 | 1 | |||

| ≥ 65 | 0.78 (0.24, 2.57) | |||

| Family History | 0.101 | |||

| 0 | 1 | |||

| 1 | 2.30 (0.91, 5.78) | |||

| T | 0.972 | |||

| 1/2 | 1 | |||

| 3/4 | 0.99 (0.46, 2.12) | |||

| N | 0.013 | |||

| 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 1 | 2.37 (1.19, 4.69) | 3.57 (0.71, 18.09) | 0.124 | |

| M | 0.021 | |||

| 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 1 | 2.47 (1.09–5.59) | 1.40 (0.35, 5.59) | 0.638 | |

| Number of organs involved | 0.005 | |||

| > 2 | 1 | 1 | ||

| ≤ 2 | 0.36 (0.18, 0.74) | 1.57 (0.27, 9.07) | 0.615 | |

| Grade | 0.001 | |||

| G1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| G2 | 0.82 (0.30, 2.24) | 1.42 (0.42, 4.81) | 0.575 | |

| G3 | 3.56 (1.21, 10.44) | 4.74 (1.15, 19.55) | 0.032 | |

| Primary site | 0.024 | |||

| GEP-NETs | 1 | 1 | ||

| ExtraGEP-NETsa | 2.60 (1.18, 5.70) | 2.43 (1.02, 5.81) | 0.046 | |

| Recurrence | 0.001 | |||

| 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 1 | 3.62 (1.56, 8.43) | 4.13 (1.10, 15.44) | 0.035 | |

| LDH | 0.050 | |||

| < 250 | 1 | |||

| ≥ 250 | 2.39 (1.07, 5.37) | |||

| CRP | 0.102 | |||

| < 3 | 1 | |||

| ≥ 3 | 1.75 (0.90, 3.42) | |||

| ALT | 0.006 | |||

| < 40 | 1 | 1 | ||

| ≥ 40 | 3.10 (1.47, 6.53) | 0.98 (0.34, 2.84) | 0.975 | |

| AST | 0.022 | |||

| < 35 | 1 | 1 | ||

| ≥ 35 | 2.32 (1.17, 4.63) | 2.04 (0.72, 5.78) | 0.179 | |

| CRE | 0.556 | |||

| < 73 | 1 | |||

| ≥ 73 | 0.79 (0.36, 1.75) | |||

| Ki67 | 0.001 | |||

| < 3 | 1 | 1 | ||

| > 20 | 3.56 (1.21, 10.44) | 4.74 (1.15, 19.55) | 0.032 | |

| 3–20 | 0.82 (0.30, 2.24) | 1.42 (0.42, 4.81) | 0.575 | |

| Chemotherapy | 0.289 | |||

| 0 | 1 | |||

| 1 | 0.69 (0.35, 1.38) | |||

| Everolimus | 0.454 | |||

| 0 | 1 | |||

| 1 | 1.31 (0.65, 2.65) | |||

| Surgery | 0.007 | |||

| 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 1 | 0.36 (0.17, 0.77) | 1.06 (0.351, 3.20) | 0.918 | |

| Radiotherapy | 0.051 | |||

| 0 | 1 | |||

| 1 | 0.30 (0.07, 1.27) | |||

| SSA | 0.458 | |||

| 0 | 1 | |||

| 1 | 1.30 (0.65, 2.57) | |||

| Immunotherapy | 0.258 | |||

| 0 | 1 | |||

| 1 | 1.80 (0.69, 4.67) | |||

| Treatment c | 0.484 | |||

| Monotherapy | 1 | |||

| Combined chemotherapy | 0.58 (0.20, 1.66) | |||

| Combined immunotherapy | 0.92 (0.21, 3.92) | |||

| Combined chemotherapy and immunotherapy | 2.33 (0.52, 10.41) | |||

| Treatment lines | 0.233 | |||

| First line | 1 | |||

| ≥ Second line | 0.588 (0.245,1.407) | |||

| LAR | 0.106 | |||

| ≤ 5.8 | 1 | |||

| > 5.8 | 2.03 (0.91, 4.54) | |||

| PLR | 0.027 | |||

| ≤ 340.6 | 1 | 1 | ||

| > 340.6 | 2.86 (1.24, 6.60) | 3.34 (1.20, 9.29) | 0.021 | |

| NLR | 0.057 | |||

| ≤ 6.2 | 1 | |||

| > 6.2 | 2.67 (1.16, 6.16) | |||

| PNI | 0.062 | |||

| ≤ 58.1 | 1 | |||

| > 58.1 | 0.16 (0.02,1.14) | |||

| SII | 0.201 | |||

| ≤ 1080.9 | 1 | |||

| > 1080.9 | 1.68 (0.78, 3.61) | |||

| SIRI | 0.149 | |||

| ≤ 2.5 | 1 | |||

| > 2.5 | 1.80 (0.84, 3.87) |

Abbreviations GEP, gastroenteropancreatic; NET, neuroendocrine tumors; SSA, somatostatin analogues; LAR, lactate dehydrogenase-to-albumin ratio; PLR, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio; NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; PNI, prognostic nutritional index; SII, systemic immune inflammation index; SIRI, systemic inflammatory response index

ExtraGEP-NETsa: NETs originated in biliary system, lung, peritoneum, abdominal cavity, liver, uterus and cervix, larynx, thyroid, pelvis, kidneys, adrenal glands, head and neck, thymus and mediastinum. Treatmentc: initiation of treatment with surufatinib

Subgroups analysis for survival

To further explore the impact of primary tumor site on the efficacy of surufatinib, we conducted a subgroup analysis of patients in the GEP-NETs group. We assessed the effect of primary tumors located in the stomach, intestines, and pancreas on patient survival. In the GEP-NETs subgroup, the number of patients with primary tumors in the stomach, intestines, and pancreas were 4, 28, and 59, respectively. Kaplan-Meier analysis showed no significant difference in OS and PFS among patients with primary tumors from these three sites (Fig. 2). However, patients with primary tumors in the stomach tended to have higher risks of tumor progression and death.

Fig. 2.

Progression-free survival (A) and overall survival (B) analysis of the GEP-NETs patients subgroup

Since the liver is the most common site of distant metastasis in NETs patients, we also performed a subgroup analysis of these patients. The results indicated that among patients with liver metastasis, those with primary GEP-NETs had a longer OS compared to those with primary NETs from other sites (HR: 5.684; 95% CI, 2.061–15.677; P < 0.001). These results are shown in Fig. 3B. There was no significant difference in PFS between the two groups (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

Progression-free survival (A) and overall survival (B) analysis of the patients with liver metastases subgroup

Efficacy analysis and AEs

As depicted in Fig. 4, among the 133 patients who underwent at least one response assessment, the ORR was 10.5%. The ORR was 12.1% in patients with GEP-NETs, which was higher than that in patients with extraGEP-NETs (7.1%). A total of 14 patients achieved PR, with 11 of them having tumors originating from the GEP. 81 patients were assessed as having SD after treatment. The DCR for all patients was 71.5%, with a higher DCR observed in patients with GEP-NETs compared to those with extraGEP-NETs (72.5% vs. 69.1%).

Fig. 4.

The objective response rate (A) and disease control rate (B) analysis all patients

Table 5 summarized the incidence of any grade AEs and grade 3 AEs in all NETs patients. No grade 4–5 AEs were observed in patients. Our study reported a total of 27 grade 3 AEs related to surufatinib treatment, including proteinuria, blood bilirubin increased, hypertension, diarrhea, aminotransferase increased, hemorrhage, blood creatinine increased, vomiting, and thrombocytopenia. The most common AEs of any grade in patients with GEP-NETs included proteinuria (14.3%), blood bilirubin increased (11.0%), and hypertension (9.9%). The proportion of AEs in patients with extraGEP-NETs was lower. Only 8 patients experienced any grade of AE, of which 3 cases (7.1%) were proteinuria, while the remaining 5 cases were hypertension, fatigue, blood creatinine increased, abdominal distension, and blood thyroid stimulating hormone increased, respectively.

Table 5.

AEs of all patients

| GEP-NETs (N = 91) |

ExtraGEP-NETsa (N = 42) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Event | Any Grade | Grade ≥ 3 | Any Grade | Grade ≥ 3 |

| Proteinuria | 13 (14.3%) | 6 (6.6%) | 3 (7.1%) | 3 (7.1%) |

| Blood bilirubin increased | 10 (11.0%) | 4 (4.4%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Hypertension | 9 (9.9%) | 4 (4.4%) | 1 (2.4%) | 0 (0%) |

| Diarrhoea | 4 (4.4%) | 2 (2.2%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Aminotransferase increased | 3 (3.3%) | 2 (2.2%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| hemorrhage | 3 (3.3%) | 3 (3.3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Hypoalbuminaemia | 2 (2.2%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Fatigue | 2 (2.2%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.4%) | 0 (0%) |

| Hypertriglyceridaemia | 1 (1.1%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Blood creatinine increased | 1 (1.1%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.4%) | 1 (2.4%) |

| Vomiting | 1 (1.1%) | 1 (1.1%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Oedema peripheral | 1 (1.1%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 1 (1.1%) | 1 (1.1%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Abdominal distension | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.4%) | 0 (0%) |

| Blood thyroid stimulating hormone increased | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.4%) | 0 (0%) |

Abbreviation AE, adverse event; GEP, gastroenteropancreatic; NET, neuroendocrine tumors

ExtraGEP-NETsa: NETs originated in biliary system, lung, peritoneum, abdominal cavity, liver, uterus and cervix, larynx, thyroid, pelvis, kidneys, adrenal glands, head and neck, thymus and mediastinum

Due to the potential concurrent use of other treatments such as chemotherapy and immunotherapy among the patients receiving surufatinib, we conducted an efficacy and safety analysis specifically on patients treated with surufatinib monotherapy to eliminate confounding factors. Similarly, the ORR (8.8% vs. 4.0%) and DCR (71.9% vs. 68.0%) were higher in the GEP-NETs group compared to the extraGEP-NETs group. Detailed results of this efficacy analysis and a summary of adverse reactions are provided in the supplementary materials.

Discussion

Due to the increasing incidence of NETs, poor prognosis, and the fact that patients are often diagnosed at an advanced stage, effective treatment strategies for NETs clearly remain an unmet medical need [5]. In recent years, as comprehension of the biological traits and the tumor microenvironment of NETs deepens, the development of molecular targeted therapies for NETs has been promoted against the background of previously limited systemic therapeutic options. NETs are highly vascularized and express various pro-angiogenic molecules, including VEGF, FGF, and PDGF [15]. Additionally, another characteristic of NETs is their capability to elude the immune response, aiding in the advancement of the tumor. The main mechanism involved in immune evasion is the activation of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) promoted by CSF-1 [16]. Surufatinib, as an orally available small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor, possesses multiple mechanisms of action. It inhibits tumor angiogenesis by targeting VEGFR-1/2/3 and FGFR-1, and also regulates TAMs by inhibiting CSF-1R, thus targeting immune system evasion. Over the past few years, surufatinib has been used primarily in patients with progressive, well-differentiated NETs with unresectable, locally advanced, or metastatic disease [14].

Clinical trial results have indicated that surufatinib demonstrates good clinical efficacy compared to placebo, while its ORR ranges only from 10–19% [8, 13]. Therefore, exploring indicators that may influence the efficacy of surufatinib is crucial. Previous studies have suggested that treatment-related hemorrhage, proteinuria, and hypertension within the first 4 weeks of surufatinib treatment, as well as baseline radiologic features such as high ASER-peri, high enhancement pattern, and well-defined tumor margins, could serve as viable predictive biomarkers for surufatinib [17, 18]. However, due to the high heterogeneity of NETs, some characteristics of the tumor itself can also affect drug efficacy. Since NETs are distributed throughout the body but most commonly occur in GEP, we concerned whether GEP-NETs and extraGEP-NETs would have an impact on the efficacy of surufatinib. In this study, we found that patients with GEP-NETs treated with surufatinib had lower risks of disease progression and death compared to those with extraGEP-NETs. Additionally, patients generally exhibited good tolerance to surufatinib monotherapy and combination therapy with other drugs, with no new safety concerns beyond previously known toxicities. From what we know, this is the first study to report differences in the efficacy of surufatinib between GEP-NETs and extraGEP-NETs.

Currently, there is limited research on the prognosis of patients with NETs based on the primary tumor site. Prior studies have indicated that the primary tumor site can affect the prognosis of patients with GEP-NETs with liver metastases, but the impact of the primary tumor site on GEP-NETs and extraGEP-NETs has not been elucidated [19]. However, some studies suggest that the OS of patients with GEP-NETs after resection of the primary tumor seems to be related to the patient’s histological staging system but not to the primary tumor site [20]. In our study, we found that the PFS and OS of patients treated with surufatinib were both associated with tumor grade and varied with different primary tumor sites. But subgroup analysis focusing on GEP-NETs revealed no significant differences in PFS and OS among patients with tumors originating from the stomach, intestines, or pancreas. Further investigation is needed to elucidate the underlying reasons behind these findings. Furthermore, we observed that the majority of patients were diagnosed with distant metastases, with the liver being the most common site of metastasis, consistent with literature reports [21]. Patients with liver metastases often have poor prognosis and require systemic therapy [22]. In this study, subgroup analysis was conducted on patients with liver metastases treated with surufatinib, revealing that although there was no significant difference in PFS between patients in the GEP-NETs and extraGEP-NETs groups, the former exhibited longer OS compared to the latter. This finding further confirms the impact of the primary tumor site on the efficacy of surufatinib.

We also analyzed the impact of surgery, radiotherapy, systemic treatments including chemotherapy, everolimus, SSA, immunotherapy, and combination therapies on survival outcomes in NETs patients prior to receiving surufatinib treatment. The multivariate analysis revealed that apart from surgery, which tended to benefit patients treated with surufatinib, other treatment modalities employed before surufatinib therapy initiation did not significantly affect disease progression or mortality. However, studies have indicated that benefits from surufatinib were observed in patients previously treated with systemic therapy as well as those who had not received systemic therapy [8, 13]. Moreover, prior chemotherapy, SSA, or everolimus treatment did not influence the benefits of surufatinib for patients. Nevertheless, due to the retrospective nature of this study, some recording errors in collecting clinical information were inevitable, and we did not include analysis of other treatment modalities such as sunitinib or peptide receptor radionuclide therapy received by the patients. Further prospective experiments with larger sample sizes are warranted to address these limitations.

In this study, we also included several indicators related to inflammatory response and immunotherapy to analyze their association with the prognosis of NETs. Previous studies have shown that elevated NLR and PLR before treatment with the programmed death receptor-1 antibody nivolumab were associated with shorter PFS and OS, as well as lower response rates in patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer [23, 24]. PNI has been identified as a reliable predictor of outcomes in gastrointestinal cancer patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy [25]. SII has been reported as a strong indicator of poor prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma patients, possibly reflecting the level of circulating tumor cells in the blood [26]. SIRI and LAR have been associated with OS in bladder cancer and colorectal cancer patients [27–29]. In NETs, higher levels of NLR and PLR and lower levels of PNI are adverse prognostic factors, while the role of LAR and SIRI in NETs have rarely been reported [30–32]. However, these studies were mostly small samples and focused on NETs in single sites such as pancreas, stomach, and lungs. Our study, on the other hand, revealed that in patients treated with surufatinib, those with PLR > 340.6 had shorter OS and PFS, while the other indicators were not associated with OS and PFS. The differences in results may be attributed to the fact that our analysis included NETs from all sites and the sample size was relatively small.

We noted that the most common AE observed in patients treated with surufatinib in both groups was proteinuria, which is consistent with previous reports. Additionally, a relatively high incidence of increased blood bilirubin was observed, while the frequencies of diarrhea and increased blood thyroid stimulating hormone were relatively lower, showing some discrepancy compared to reported results [8, 13]. Furthermore, as mentioned earlier, treatment-related hypertension, proteinuria, and hemorrhage may serve as biomarkers associated with poor prognosis with surufatinib. Our study results showed a higher frequency of these AEs in patients with GEP-NETs. We considered that this might be related to the difference in the duration of surufatinib use between the two groups of patients. In this study, the median duration of surufatinib use was 10 months (range: 1–59 months) for the GEP-NETs group and 3 months (range: 1–34 months) for the extraGEP-NETs group. We speculated that a longer treatment duration may lead to a higher frequency AEs. In the extraGEP-NETs group, the overall shorter duration of surufatinib use may result in patients discontinuing the drug or experiencing disease progression before the onset of AEs. Additionally, there were patients with a very short duration of surufatinib use, which may be due to various reasons, leading to loss of follow-up and resulting in some data bias.

Inevitably, there are certain constraints associated with this study. First, it is a retrospective study and the sample size of patients included in the study was small due to objective constraints. Next, the clinical characteristics of the patients lacked the results of somatostatin receptor and other laboratory results. Lastly, there is heterogeneity in baseline data between the two groups of patients regarding LDH, everolimus, SSA, combination therapy methods, Ki67 (grade), and age, leading to a possible degree of error in the results. Prospective studies with large sample sizes may partially address these issues.

In conclusion, our data indicate that the primary tumor site is an important factor influencing the efficacy of surufatinib in patients with NETs. Considering the primary tumor site before deciding whether to administer surufatinib to patients may lead to different clinical decisions for clinicians. This simple, easily determined factor warrants further prospective randomized studies to optimize the selection of patients for surufatinib treatment.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author contributions

Desheng Weng, Jingjing Zhao, and Yan Tang designed the study; Minxing Li and Songzuo Xie collected the data. Yuanyuan Liu, Xinyi Yang, and Yan Wang analyzed and interpreted the data; Jinqi You produced the figures; Yuanyuan Liu drafted the manuscript; Desheng Weng and Jingjing Zhao supervised and gave a critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read the manuscript and gave final approval to the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (No. 2023A1515010713, 2021A1515010443, and 2023A1515012467).

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Clinical data were obtained with the approval and consent of the Ethics Committee of Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center (Approval number: B2023-150-01). The Ethics Committee of Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center waived the requirement of informed consent for patients as the study was retrospective in nature and did not adversely affect the health and rights of the subjects.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Yuanyuan Liu, Xinyi Yang and Yan Wang contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Yan Tang, Email: tangyan@sysucc.org.cn.

Jingjing Zhao, Email: zhaojingj@sysucc.org.cn.

Desheng Weng, Email: wengdsh@sysucc.org.cn.

References

- 1.Di Domenico A, Wiedmer T, Marinoni I, Perren A. Genetic and epigenetic drivers of neuroendocrine tumours (NET). Endocr Relat Cancer. 2017;24(9):R315–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dasari A, Shen C, Halperin D, Zhao B, Zhou S, Xu Y, et al. Trends in the incidence, prevalence, and survival outcomes in patients with neuroendocrine tumors in the United States. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(10):1335–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pozas J, Alonso-Gordoa T, Román MS, Santoni M, Thirlwell C, Grande E, et al. Novel therapeutic approaches in GEP-NETs based on genetic and epigenetic alterations. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 2022;1877(5):188804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oronsky B, Ma PC, Morgensztern D, Carter CA. Nothing but NET: a review of neuroendocrine tumors and carcinomas. Neoplasia. 2017;19(12):991–1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xu J. Current treatments and future potential of surufatinib in neuroendocrine tumors (NETs). Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2021;13:17588359211042689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ichikawa Y, Kobayashi N, Takano S, Kato I, Endo K, Inoue T. Neuroendocrine tumor theranostics. Cancer Sci. 2022;113(6):1930–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walter MA, Nesti C, Spanjol M, Kollár A, Bütikofer L, Gloy VL, et al. Treatment for gastrointestinal and pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours: a network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;11(11):Cd013700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu J, Shen L, Bai C, Wang W, Li J, Yu X, et al. Surufatinib in advanced pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours (SANET-p): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(11):1489–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang J, Jia Z, Li Q, Wang L, Rashid A, Zhu Z, et al. Elevated expression of vascular endothelial growth factor correlates with increased angiogenesis and decreased progression-free survival among patients with low-grade neuroendocrine tumors. Cancer. 2007;109(8):1478–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Syed YY, Surufatinib. First Approval Drugs. 2021;81(6):727–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang P, Shi S, Xu J, Chen Z, Song L, Zhang X, et al. Surufatinib plus Toripalimab in patients with advanced neuroendocrine tumours and neuroendocrine carcinomas: an open-label, single-arm, multi-cohort phase II trial. Eur J Cancer. 2024;199:113539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koumarianou A, Kaltsas G. Surufatinib - a novel oral agent for neuroendocrine tumours. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2021;17(1):9–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu J, Shen L, Zhou Z, Li J, Bai C, Chi Y, et al. Surufatinib in advanced extrapancreatic neuroendocrine tumours (SANET-ep): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(11):1500–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaderli RM, Spanjol M, Kollár A, Bütikofer L, Gloy V, Dumont RA, et al. Therapeutic options for neuroendocrine tumors: a systematic review and network Meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(4):480–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cives M, Strosberg JR. Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):471–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cai L, Michelakos T, Deshpande V, Arora KS, Yamada T, Ting DT, et al. Role of Tumor-Associated macrophages in the clinical course of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PanNETs). Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(8):2644–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li J, Cheng Y, Bai C, Xu J, Shen L, Li J, et al. Treatment-related adverse events as predictive biomarkers of efficacy in patients with advanced neuroendocrine tumors treated with surufatinib: results from two phase III studies. ESMO Open. 2022;7(2):100453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang J, Zhu H, Shen L, Li J, Zhang X, Bai C, et al. Baseline radiologic features as predictors of efficacy in patients with pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors with liver metastases receiving surufatinib. Chin J Cancer Res. 2023;35(5):526–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tierney JF, Poirier J, Chivukula S, Pappas SG, Hertl M, Schadde E, et al. Primary Tumor Site affects survival in patients with gastroenteropancreatic and neuroendocrine liver metastases. Int J Endocrinol. 2019;2019:9871319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Russolillo N, Vigano L, Razzore P, Langella S, Motta M, Bertuzzo F, et al. Survival prognostic factors of gastro-enteric-pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors after primary tumor resection in a single tertiary center: comparison of gastro-enteric and pancreatic locations. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015;41(6):751–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Das S, Dasari A, Epidemiology. Incidence, and prevalence of neuroendocrine neoplasms: are there global differences? Curr Oncol Rep. 2021;23(4):43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hallet J, Law C, Singh S, Mahar A, Myrehaug S, Zuk V, et al. Risk of Cancer-Specific death for patients diagnosed with neuroendocrine tumors: a Population-based analysis. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2021;19(8):935–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nøst TH, Alcala K, Urbarova I, Byrne KS, Guida F, Sandanger TM, et al. Systemic inflammation markers and cancer incidence in the UK Biobank. Eur J Epidemiol. 2021;36(8):841–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Diem S, Schmid S, Krapf M, Flatz L, Born D, Jochum W, et al. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) as prognostic markers in patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) treated with nivolumab. Lung Cancer. 2017;111:176–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang L, Ma W, Qiu Z, Kuang T, Wang K, Hu B, et al. Prognostic nutritional index as a prognostic biomarker for gastrointestinal cancer patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1219929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hu B, Yang XR, Xu Y, Sun YF, Sun C, Guo W, et al. Systemic immune-inflammation index predicts prognosis of patients after curative resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(23):6212–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ye K, Xiao M, Li Z, He K, Wang J, Zhu L, et al. Preoperative systemic inflammation response index is an independent prognostic marker for BCG immunotherapy in patients with non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Cancer Med. 2023;12(4):4206–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shu XP, Xiang YC, Liu F, Cheng Y, Zhang W, Peng D. Effect of serum lactate dehydrogenase-to-albumin ratio (LAR) on the short-term outcomes and long-term prognosis of colorectal cancer after radical surgery. BMC Cancer. 2023;23(1):915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu H, Lin T, Ai J, Zhang J, Zhang S, Li Y, et al. Utilizing the Lactate dehydrogenase-to-albumin ratio for Survival Prediction in patients with bladder Cancer after Radical Cystectomy. J Inflamm Res. 2023;16:1733–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xiang JX, Qian YR, He J, Lopez-Aguiar AG, Poultsides G, Rocha F, et al. Low Prognostic Nutritional Index is Common and Associated with poor outcomes following curative-intent resection for gastro-entero-pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Neuroendocrinology. 2024;114(2):158–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang L, Fu M, Yu L, Wang H, Chen X, Sun H. Value of markers of systemic inflammation for the prediction of postoperative progression in patients with pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2024;15:1293842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shi M, Zhao W, Zhou F, Chen H, Tang L, Su B, et al. Neutrophil or platelet-to-lymphocyte ratios in blood are associated with poor prognosis of pulmonary large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2020;9(1):45–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.