Abstract

Background

Identify individuals who are at risk of Type 2 diabetes, who also are at a greater risk of developing cardiovascular disease is important. The rapid worldwide increase in diabetes prevalence call for Primary Health Care to find feasible prevention strategies, to reduce patient risk factors and promote lifestyle changes. Aim of this randomized controlled trial was to investigate how a nurse-lead Guided Self-Determination counselling approach can assist people at risk of type 2 diabetes to lower their coronary heart disease risk.

Methods

In this randomized controlled study, 81 people at risk of developing type 2 diabetes were assigned into an intervention group (n = 39) receiving Guided Self-Determination counselling from Primary Health Care nurses over three months and a control group (n = 42) that received a diet leaflet only. Measurements included the Finnish Diabetes Risk Score questionnaire and biological measurements of Hemoglobin A1c protein, Body Mass Index, fasting blood glucose, Blood pressure, Cholesterol, High-density lipoprotein, and triglycerides, at baseline (time1), 6 (time2) and 9 months (time 3).

Results

A total of 56 participants, equal number in intervention and control groups, completed all measurements. A significant difference between the intervention and control groups, in coronary heart disease risk was not found at 6 nor 9-months. However, within-group data demonstrated that 55.4% of the participants had lower coronary heart disease risk in the next ten years at the 9-month measurement. Indicating an overall 18% relative risk reduction of coronary heart disease risk by participating in the trial, with the number needed to treat for one to lower their risk to be nine. Within the intervention group a significant difference was found between time 1 and 3 in lower body mass index (p = 0.046), hemoglobin A1c level (p = 0.018) and diastolic blood pressure (p = 0.03).

Conclusions

Although unable to show significant group differences in change of coronary heart disease risk by this 12-weeks intervention, the process of regular measurements and the guided self-determination counselling seem to be beneficial for within-group measures and the overall reduction of coronary heart disease risk factors.

Trial registration

This study is a part of the registered study ‘Effectiveness of Nurse-coordinated Follow-Up Programme in Primary Care for People at Risk of T2DM’ at www.ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04688359) (accessed on 30 December 2020).

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12889-024-20538-1.

Keywords: Prediabetes, Type 2 diabetes, Cardiovascular heart diseases, Guided self-determination, Health promotion

Introduction

The risk of developing cardiovascular disease (CVD) rises with age [1]. Furthermore, diagnosis of type 2 diabetes (T2D) increases the CVD risk in individuals to a level that is equivalent to someone who is 10 years older and does not have T2D. For T2D patients, CVD are the main cause of morbidity and mortality [1–3]. Individuals identified as being at T2D risk have a significantly increased likelihood, up to twelve times greater, of developing diabetes in the future compared to those with normal glycaemic tolerance [4]. Additionally, persons who are identified as being at risk for T2D or at the prediabetes stage may also have a higher risk of developing CVD compared to individuals with normal glucose metabolism [5, 6].

By 2045, it is projected that prediabetes symptoms would impact almost one in every ten individuals worldwide. Characterized by one or more of the following: impaired fasting glucose (IFG), impaired glucose tolerance without meeting the diagnostic criteria for T2D, and/or increased levels of HbA1c [7].

Prediabetes warning signs are accompanied by health risk indications that also may raise the risk of cardiovascular problems, such as high body mass index (BMI), high blood pressure and dyslipidaemia [8]. In addition, diabetes-related comorbidities including retinopathy and food ulcers [1] are not only a burden for individuals, but also a concern for the society [1]. By implementing health-promoting strategies aiming at reducing risks for individuals in the prediabetes stage, it is possible to effectively decrease the elevated health risks [7]. Identifying individuals in the prediabetes stage and offering them a comprehensive health promotion program that focuses on modifiable risk factors such as nutrition and physical inactivity has the potential to avoid the progression to diabetes [9]. Research on diabetes preventive programs, such as the National Diabetes Preventive Program in the US and the Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study, have demonstrated the lasting benefits of interventions that improve health in halting the progression of T2D [4, 10]. Prior research also suggests that the implementation of nurse-led programs in Primary Health Care (PHC) can help patients decrease their risk of both T2D and CVD [11]. Furthermore, lifestyle counselling has been proven to be both cost-effective and a secure method for reducing the likelihood of individuals with prediabetes progressing to T2D [12]. Implementing a nurse-led counselling program focused on proactive health promotion for those at risk of developing T2D within PHC settings could potentially help reduce the increasing prevalence of T2D [13].

Guided Self-Determination (GSD) is a counselling approach that draws upon research and concepts related to empowerment, self-determination, life skills, and humanistic principles [14, 15]. The objective of this method is to empower persons with chronic illnesses, equipping them with the essential abilities to proficiently navigate the challenges involved with self-managing their condition [14–16]. Reflection sheets are used as a supporting instrument to foster autonomy by assisting individuals in establishing goals for health promotion, deepening comprehension of values, recognizing opportunities, and fostering a readiness to change [14]. Healthcare professionals employ mirroring, active listening, and value-clarifying responses to support and motivate individuals in attaining their goals [14, 17]. The goal in GSD is to promote a reflection process, cooperation and motivate individuals to investigate and conquer the existing obstacles they encounter in their daily life [18–20].

The GSD counselling method acknowledges that conflicts may emerge due to an individual's perspective on life, their resistance to integrate their "disease/risk symptoms" into their daily life, and the impact of these symptoms on their overall welfare [14, 15, 19]. The rising prevalence of T2D and prediabetes and therefore CHD calls for further development and implementation of cost-effective and non-invasive counselling approaches, like the GSD, which may be easily included into PHC systems in a sustainable way. Prior lifestyles interventions using other methods in their interventions [4, 10], have demonstrated to be cost effective and reduce risk of T2D later in life. However, they were time-consuming and lasting for extended intervention periods, like for the Finnish diabetes prevention study [10], with active intervention of one to six years with medium of 4-years [10]. The objective of this randomised controlled trial (RCT) was to investigate whether a short intervention of three times GSD counselling over 12 weeks, provided by PHC nurses to patients identified as being at risk of developing T2D, would lead to a reduction in CHD risk factors in the intervention group compared to the control group.

Materials and methods

Recruitment of participants

Participants were selected from a pool of 220 participants who had previously taken part in a prediabetes screening study. The recruitment took place at the three largest PHC clinics in North Iceland [21, 22]. The power estimates for sample size were derived using a population size of 21,000 individuals aged 18–75 years living in the research area in the year 2019, as reported by Statistics Iceland [23]. In the calculation of sample size to establish eligibility for allocation in the RCT the confidence interval (CI) level was set at 85% with a margin of error of 5%. A minimum sample size of 206 participants in the screening study was needed to conduct this RCT, and at least 30 in each group at time 1 measurement. Although a larger sample, at 378 would be good and provided CI level of 95% with a 5% margin of error, this was not a viable sample size to recruit, given the population size and dispersion in the sparsely populated research area at the time of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Individuals between the ages of 18 and 75 who resided in the service area of the participating PHC clinics, were eligible for participation. Participants were required to not have a diagnosis of T2D and had fluent proficiency in either Icelandic or English. The enrolment criteria were based on achieving a score of ≥ 9 points on the Finnish diabetes risk score scale (FINDRISC), in addition either or both, BMI ≥ 30 kg/m[2] and/or HbA1c of ≥ 40 mmol/mol. The FINDRISC scoring scale estimates the risk of developing T2D within the next 10 years, using eight questions and assigns a score ranging from 0 to 26 points, with increasing risk with higher scores [21, 24].

Allocation into intervention and control groups

The 81 eligible participants, who satisfied the enrolment criteria, were allocated a numerical identity by the first author (EA). These identifiers were then placed in separate jars based on age (below or over 50 years) and gender. The second author (AKS) picked a pair of numbers from each of the two jars. The first number in each pair belonged to the intervention group, while the second number belonged to the control group. This procedure persisted until all the numbers were selected. Subsequently, the author EA reached out to the participants to arrange a single measurement session, either at the nearest PHC station or at the research centre. The allocation ratio was in favour of the intervention, with a ratio of 1.08:1.00. This preference was taken for any potential dropouts throughout the intervention. Of the 81 eligible 64 participated in time 1 measurement or 79%.

The intervention group

The GSD counselling approach intervention had not been previously employed in Iceland. Hence, the six nurses, two assigned to each PHC clinic who were implementing the intervention, attended a one-day workshop on GSD in March 2020 at the research centre, facilitated by the last-author BCHK. The seminar included ongoing assessment and feedback. Prior to starting the intervention, an online meeting was conducted with the six nurses and BCHK to enhance their proficiency in providing GSD counselling. The participants were given a notebook to record their thoughts and comments in, as well as a sheet with prompts and questions for reflection, mirroring, and active listening during the GSD intervention. During the intervention period, the nurses were contacted by EA over an encrypted Microsoft Teams© channel and phone. They were asked if they had any questions regarding the delivery of GSD or if they needed any assistance. In addition, the nurses had the option to communicate with EA or BCHK by phone or through the Teams channel for any inquiries.

The GSD intervention started in late December 2021 and finished in April 2022. The duration of each GSD counselling section (intervention) was approximately 60 min, with 4–6 weeks intervals in total of 12–16 weeks. Between counselling sections, the participants were instructed to complete the GSD reflection sheets that were given to them during their first GSD counselling with the nurse [19]. The sixteen GSD reflection sheets handed to participants had previously been used in a study with individuals at risk of developing T2D and with manifest T2D in Norway. The sheets were then translated from Norwegian to Icelandic for the purpose of this research. During each consultation session, the participants engaged in discussions with the nurse on their notes on the reflection sheets, while also establishing objectives for their health promotion. Following the measurements at time 1 (baseline), the intervention group was notified by EA that a nurse from the nearest PHC would contact them for three GSD consultations, spanning a duration of three to four months.

The control group

The control group were at time 1, following the measurements, given a booklet from the Icelandic Directorate of Health [25] on healthy diet choices, and informed that the next part of the research would be repeated measurements that would take place in 6 and 9 months from time 1 measurement.

Instruments, and biological measurement

Primary outcome, the Icelandic Heart Association coronary heart disease risk calculator

For more than 50 years, the Icelandic Heart Association has gathered data from a comprehensive health survey, which includes statistics on the prevalence and death rates of coronary heart disorders (CHD) [26]. An outcome of this scientific research is the development of an open access heart disease risk calculator (ICE-HEART), which evaluates an individual's probability of CHD over the course of the following decade [27]. The ICE-HEART is comparable to the SCORE risk calculator developed by the European Society of Cardiology [27]. The ICE-HEART CHD risk calculator (http://risk.hjarta.is/risk_calculator/) provides an estimate of an individual's probability, expressed as a percentage, of developing CHD during the following 10 years. This estimate is compared to the average probability of CHD for individuals of the same gender (male/female) and age [27].

The primary outcome of this RCT was set as a change in the relative risk (RR) of CHD, when compared to individuals of the same age and gender, both within and between the intervention and control groups. This was assessed using the open access online ICE-HEART CHD risk calculator [27]. The calculator incorporates measures of age (within the range of 35–75 years), height (ranging from 150–200 cm), weight (between 45–120 kg), systolic blood pressure (ranging from 100–200 mmHg), total cholesterol (CHOL) levels (ranging from 4–10 mmol/L), high density lipoprotein (HDL) levels (ranging from 0.5–2.5 mmol/L), and triglycerides (TRG) levels (ranging from 0.5–4.5 mmol/L). Furthermore, the variables required for the assessment of CHD risk include the levels of physical activity, smoking patterns, presence of diabetes, and family history of CHD [27].

The height was recorded using a portable measuring tape, rounded to the nearest 0.1 cm, while the weight was measured on a digital scale, rounded to the nearest 100 g. The measurements were taken when the person was wearing light clothes [28].

The cholesterol (CHOL), high-density lipoprotein (HDL), and triglycerides (TRG) levels were measured using a Mission® cholesterol meter. In addition, ICE-HEART provides computed tests for low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and the ratio of total cholesterol to high-density lipoprotein (CHOL/HDL).

Participants' blood pressure (BP) was measured at the end of each section after they had been seated for a duration of 10 min. Utilizing the Medisana® upper arm meter for measuring [29]. The treatment threshold for systolic pressure is commonly set as ≤ 140 mm/Hg and for diastolic pressure as < 90 mmHg [30]. Research indicates that elevated BP raises the likelihood of developing CVD [31, 32].

Secondary outcomes and definition of T2D and prediabetes level

The Body Mass Index (BMI) ≥ 30 kg/m[2] was one of the inclusion criteria, calculated using height and weight, reported in kg/m2. A BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 indicates overweight and a BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 indicates obesity [32]. The measurements of waist circumference, taken 2 cm above the navel, and hip circumference at the widest point, as well as height in centimetres, were recorded using a measuring tape with a capacity of either 1.5 or 3 m. The accuracy of the measuring tapes was frequently assessed. The waist-to-height ratio WHtR was computed by dividing the waist measurement in cm by the height measurement in cm. The WHtR is not influenced by gender or ethnicity. Previous study suggests that it may be a more accurate predictor of diabetes risk compared to BMI. A WHtR ratio of less than 0.5 indicates no increased overall health risk, while a ratio between 0.5 and 0.6 indicates an elevated risk. A WHtR ratio of 0.6 or above indicates a very high overall health risk [31, 33, 34]. Previous studies have suggested that the WHtR is a more effective screening tool than the Waist-to-Hip ratio (WHR) for identifying individuals at risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and T2D. This is because an elevated WHtR is a stronger indicator of both conditions compared to an elevated WHR [22, 31, 34–36].

WHO has approved the HbA1c level as a diagnostic test of T2D [37]. We employed the DCA Vantage® system (manufactured by Siemens Medical Solutions Diagnostics Europe Limited, based in Dublin, Ireland) to analyse capillary blood samples. The American Diabetes Association classifies HbA1c levels between 39 and 47 mmol/mol (5.7 – 6.4%) as prediabetes, whereas levels of 48 mmol/mol (6.5%) or more are considered indicative of T2D [38].

Fasting glucose (FBG) was measured using a capillary blood sample and the OneTouch® Verio Flex blood glucose meter. The latest advice for diagnostic purposes for T2D is to utilize plasma or fasting plasma glucose [39]. The objective was to conduct a screening for alterations in blood glucose levels during the duration of the RCT. Normal glucose level is defined as being less than 5.5 mmol/l (< 100 mg/dl). Prediabetes is classified as having a glucose level between 5.5–6.9 mmol/l (100–125 mg/dl), whereas diabetes is diagnosed when the glucose level exceeds 7 mmol/l (≥ 126 mg/dl) [40].

Participants in addition answered questions regarding background characteristics, and the FINDRISC tool to record changes over the RCT time [41]. FINDRISC is a questionnaire consisting of eight questions. Each question is scored on a scale of 0 to 26 points. A higher score implies a higher chance of developing T2D in the following 10 years. The FINDRISC has been authorized as a diagnostic test for assessing the risk of developing T2D [42].

Data collection

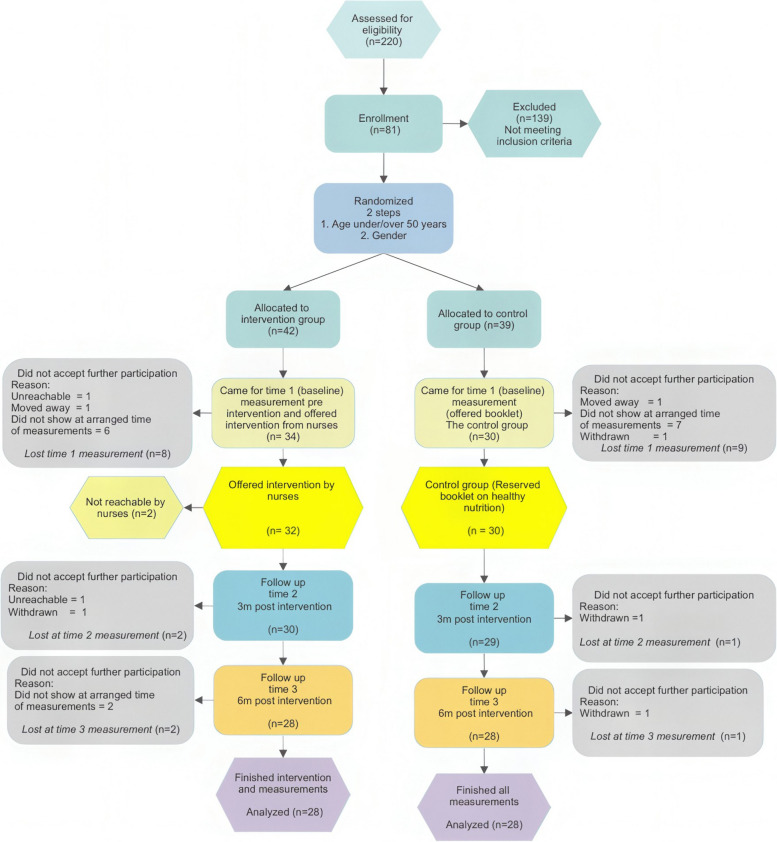

Baseline measurements were collected from the end of October 2021 to the middle of December 2021, and the next measurement in late spring 2022, and the last in late autumn 2022. Figure 1 displays a visual representation of the measurement timeline. Each participant was given a document with the current biological measures as well as one-time prior measurement at each session. Consequently, they were able to see and compare the differences between the present measurement and a previous measurement.

Fig. 1.

Flow Chart of eligible participants in the intervention

To reduce the number of dropouts, those who did not appear at the scheduled time for measurements were given the opportunity to reschedule their appointment at least two more times before being classified as dropouts. Researcher EA personally interacted with and performed all the measurements on every participant.

Statistical analysis

The ICE-HEART calculator available online at http://risk.hjarta.is/risk_calculator/, was used to calculate predicted CHD risk for each participant. The ICE-HEART risk calculator includes defined lower and upper limits of values for the variables. The calculator automatically adjusted variables to the highest/lowest applicable score if a participant’s value went outside the range of the ICE-HEART variables. The ICE-HEART calculator provides an individual's estimated CHD risk, in the next 10 years, in percentages as well as the average risk for the same age and gender. To be able to compare the risk of participants of different ages and genders, the individual risk of each person was divided by the risk of the ICE-HEART same age and gender risk. This enabled calculation of mean CHD risk of each group of participants in comparison with the mean CHD risk of the ICE-HEART cohort. The outcomes were reported as the ratio of the risk for each participant divided by risk of an individual of same age and gender, according to the ICE-HEART risk calculator. Calculations for each participant were verified twice to avoid any potential input mistakes.

The study participants' changes in CHD risk were assessed from time 1 to time 3. This allowed for the calculation of the "control event risk" (CER), "experimental event rate" (EER), and subsequently the "absolute risk reduction" (ARR) using the formula CER-EER = ARR. The Number Needed to Treat (NNT) for a favourable result is defined as the outcome of the ARR. The relative risk (RR) was determined by dividing the chance of an adverse outcome in the intervention group by the probability of an unfavourable outcome in the control group. Relative risk reduction (RRR) is a measure that quantifies the extent to which the risk of negative outcomes is lowered by an intervention compared to a control group [43]. The absence of any change in CHD risk between time 1 and time 3 was considered a poor outcome. This was because the goal was to decrease the risk, and reporting no change was seen as a more careful and cautious approach to presenting the results of this RCT. Descriptive statistics were employed to analyse continuous data and calculate means, standard deviations, and ranges. The groups were compared using chi-squared calculations, and changes in risk between measurements were calculated using crosstabs for odds ratio (OR), RR, and NNT calculations. The independent t-test was employed to compare the means of continuous variables between groups.

The General Linear Model of repeated measurements was used to calculate the interaction between and within groups throughout time. Due to the potential sensitivity of small sample sizes to sphericity, a mixed ANOVA, was added in analysing the data [44].

Data was analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics 27 and for mixed ANOVA the R version 4.3.1 (2023–07-16 ucrt), using rstatix, lme4, mixed effect model and lemerTest. Missing data, was if applicable, excluded listwise. Statistically significant difference was set at p ≤ 0.05 (two tailed).

Ethical considerations

The present study was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and with the approval of the Icelandic National Bioethics Committee (VSN), (VSN-19–080-V1 approved 14/01/2020). All participants received verbal and written information and signed an informed consent form before participating. This study is registered at www.ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01688359) on 30th December 2020. It is titled ‘Effectiveness of Nurse-coordinated Follow-Up Programme in Primary Care for People at Risk of T2DM’. The CONSORT 2010 criteria are utilized for reporting the randomized trial [45].

Results

Participant characteristics at enrolment

Out of the 81 participants who met the enrolment criteria, 42 were assigned to the intervention group and 39 were assigned to the control group. At baseline (time 1) 34 (81%) in the intervention- and 30 (76.9%) in the control group participated. Furthermore, the dropout rate from time 1 to time 3, was 17.5% in the intervention and 6.7% in the control group, see Flow Chart in Fig. 1. Most dropouts occurred during the period between enrolment and time 1, with a dropout rate of 8% for the intervention and 9% for the control group. Four participants voluntarily withdrew from the study, citing the ongoing Covid-19 epidemic (I:0/C:1) and a diagnosis of T2D (I:1/C:2) as reasons. A total of 56 participants, with 28 in each group, completed the intervention and all measurements.

Background information of participants

There was no significant difference between the intervention and control groups at enrolment. In both groups participants had a high educational level, and the majority were employed either half- or full-time. Females were in majority, and all participants except one were at increased health risk according to WHtR. However, it is worth noting that only one reported being a smoker, enrolment characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Background information on enrolment and score of FINDRISC

| Intervention group (n = 28) | Control group (n = 28) | p value* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 8 | 8 | 1.0 |

| Female | 20 | 20 | ||

| Age* | < 50 years | 8 | 6 | |

| 50–59 years | 7 | 11 | ||

| 60–69 years | 9 | 8 | ||

| 70–75 years | 4 | 3 | ||

| Mean** | 55.7(± 11.8) | 57.2(± 9.4) | .601 | |

| WHR* |

Low health risk Men: < 0.94 / Women: < 0.80 |

4 | 1 | .160 |

|

Higher health risk Men: ≥ 0.94 / Women ≥ 0.80 |

24 | 27 | ||

| WHtR* | < .5 low increased health risk | 1 | 0 | .124 |

| ≥ .5 Increased health risk | 27 | 28 | ||

| Weight (kg) | Mean** | 99.03 (± 16.34) | 98.15 (± 16.70) | .842 |

| BMI* | 25–30 kg/m2 | 2 | 4 | .388 |

| > 30 kg/m2 | 26 | 24 | ||

| Mean** | 33.89 (± 4.03) | 34.24 (± 4.46) | .757 | |

| Smoking* | Yes | 1 | 0 | .600 |

| No | 22 | 23 | ||

| Stopped smoking | 5 | 5 | ||

| Coronary-CHD family member* | Yes | 9 | 15 | .105 |

| No | 19 | 13 | ||

| Educational level* | Elementary /junior high | 8 | 7 | .055 |

| Upper secondary school/vocational training | 11 | 4 | ||

| University degree | 9 | 17 | ||

| Occupational status* | Working part or full time | 18 | 22 | .572 |

| Unemployed | 1 | 1 | ||

| Pensioner (disabled/elderly) | 7 | 3 | ||

| Other or did not answer | 2 | 2 | ||

| HbA1c | Mean** | 36.21 (± 4.47) | 36.54 (± 4.13) | .781 |

| FINDRISC | Mean score** | 13.7 (± 3.4) | 14.8 (± 4.0) | .253 |

*Chi-square test

**independent t test

Primary outcome (The ICE-HEART risk calculator)

Table 2 shows the mean CHD risk of the ICE-HEART cohort and the intervention- and control groups (not individuals) changes from time 1 to time 3. For these small groups of participants of the intervention and control, the measurements between groups did not detect a statistically significant difference in the risk of CHD in the next ten years, from time 1 to 3. General linear model of repeated measurements indicated plausible sphericity. A Mixed ANOVA indicated that the assumption of homogenous variance (Levance) was satisfied, but the data was not normally distributed due to the presence of a few extreme values (3 in total). The sole variable that had a noteworthy impact in the mixed effect model was family history. Hence, it is not possible to infer that GSD intervention, administered in three consultations spanning short duration, had a beneficial impact on lowering the risk of CHD in this limited group that completed the RCT. At time 1, the risk of CHD for each participant in this RCT varied from 0.1% to 25.3%. Compared to the computed CHD risk for individuals in the ICE-HEART cohort, matched for age and gender, that varied from 0.1% to 7.3%. At time 1, participants had a CHD risk that was up to 11.8 times higher than that of individuals of the same age and gender according to the ICE-HEART cohort.

Table 2.

Comparation of mean calculated CHD risk of same age and gender of ICE-HEART cohort and CHD risk for the intervention and control groups at time 1, 2 and 3

| ICE-HEART Risk: Same age and gender mean risk (± SD) | Time 1: Baseline Mean CHD risk* (± SD) | Time 2: 6 months Mean CHD risk* (± SD) | Time 3: 9 months Mean CHD risk* (± SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention group (n = 28) | 2.40 (± 2.45) | 3.29 (± 2.38) | 2.96 (± 2.39) | 3.05 (± 2.44) |

| Control group (n = 28) | 2.42 (± 2.10) | 3.39 (± 1.81) | 3.71 (± 2.80) | 2.90 (± 1.77) |

| p-value** | .981 | .860 | .282 | .789 |

*Mean CHD risk adjusted for same age and gender, using GLM of repeated measures calculations, (Standard Deviation) and **Huynh–Feldt within-subjects effects, p-values between groups using independent t-test of measure of significant difference between intervention and control groups at each measurement

Figure 2 shows changes in the groups mean CHD risk according to the ICE-HEART calculator and therefore does not have zero on the y-axis. For the intervention group CHD risk was lower at time 2 than before the intervention (time 1) but did not reach significant difference, see Fig. 2. But surprisingly a decrease in CHD risk was found significant between time 2 and 3 for the control group, paired sample t-test for the control group showed t(27) = 2.39 p = 0.024, with mean difference of 0.81(± 1.80) and 95%CI [0.12, 1.51]. The control group also showed a significantly lower CHD risk from time 1 to time 3, t(27) = 2.26 p = 0.032 with a mean change of 0.49(± 1.14) 95%CI [0.05, 0.93].

Fig. 2.

Changes from time 1 to time 3 of mean individual CHD risk in each group

According to the ICE-HEART calculator the mean CHD risk for same age and gender for both groups was M = 2.41 SE (0.30) and 95%CI [1.81, 2.02]. Both the intervention and control groups had significantly higher mean CHD risk at time 1, than the ICE-HEART cohort calculations risk for the same age and gender behind the ICE-HEART. Significant difference of CHD risk was found between this RCT’s cohort compared to ICE-HEART cohort, p < 0.001 95%CI [2.46, 4.53].

Calculations of changes in CHD risk between time 1 and time 3, found significant lower CHD risk for the total sample (n = 56) in this RCT; M = 0.354 (± 1.08), t(55) = 2.53 p = 0.014 with 95%CI [0.08, 0.65]. But failed to find significant lower CHD risk within-groups. However, for 50% of the intervention group and 60.7% of the control group the CHD-risk had reduced from time 1 to time 3. Odds Ratio for one-point lower CHD-risk outcome at time 3, than at time 1, by participating in the RCT was 0.65, 95% CI [0.22, 1.87]. The CHD relative risk reduction (RRR) was 17.6% and absolute risk reduction (ARR) 10.7% from time 1 to time 3. NNT for one to benefit from the participation in the GSD was nine. For participants in both groups at time 3, lower CHD risk was found for 31 participants (I:14/C:17).

Secondary outcomes

Outcomes of biomarkers at each time point are reported in Table 3. Even though the general measurements became better, the changes did not reach significant difference between groups.

Table 3.

Secondary biological outcomes

| Outcomes | Intervention group (n = 28) | Control group (n = 28) | Mean difference 95% Confidence interval [95%CI] | Repeated measured, between groups p-value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HbA1c mmol/mol | ||||

| Time 1(baseline) | 38.36 (± 4.45) | 39.50 (± 3.95) | -1.14 [-3.40, 1.11] | .998 |

| Time 2 | 39.46 (± 4.96) | 40.25 (± 4.65) | -.79 [-3.36, 1.79] | |

| Time 3 | 38.11 (± 4.24) | 39.39 (± 4.03) | -.1.29 [-3.50, .93] | |

| Fastening blood glucose | ||||

| Time 1 (baseline) | 5.70 (± 1.17) | 5.51(± 0.72) | .19 [-.33, .71] | .940 |

| Time 2 | 5.57 (± 0.78) | 5.60(± 0.65) | -.03 [-.42, .35] | |

| Time 3 | 5.51 (± 0.89) | 5.65(± 1.15) | -.13 [-.68, .42] | |

| Weight in Kg | ||||

| Time 1 (baseline) | 98.16 (± 17.32) | 97.84 (± 17.01) | .33 [-8.87, 9.52] | .979 |

| Time 2 | 97.54 (± 17.28) | 97.22 (± 17.95) | .33 [-9.11, 9.77] | |

| Time 3 | 95.54 (± 16.62) | 96.55 (± 18.75) | -1.01 [-10.51, 8.48] | |

| BMI kg/m2 | ||||

| Time 1 (baseline) | 33.58 (± 4.52) | 34.15 (± 4.68) | -.57 [-3.04, 1.89] | .786 |

| Time 2 | 33.40 (± 4.69) | 33.88 (± 4.79) | -.48 [-3.02, 2.05] | |

| Time 3 | 32.70 (± 4.49) | 33.70 (± 4.49) | -.93 [-3.50, 1.64] | |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | ||||

| Time 1 (baseline) | 142.7 (± 15.9) | 140.3(± 12.7) | 2.43 [-5.28, 10.14] | .965 |

| Time 2 | 135.8 (± 15.7) | 141.1(± 16.2) | -5.36 [-13.92, 3.20] | |

| Time 3 | 135.8 (± 15.7) | 141.1(± 16.2) | -1.89 [-11.17, 7.38] | |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | ||||

| Time 1 (baseline) | 89.2 (± 9.8) | 87.6 (± 11.0) | 1.64 [ -3.95, 7.24] | .997 |

| Time 2 | 86.7 (± 10.7) | 87.4 (± 11.1) | -.68 [ -6.52, 5.16] | |

| Time 3 | 82.9 (± 8.2) | 87.9 (± 10.8) | -4.89 [-10.05, 0.26] | |

| Cholesterol | ||||

| Time 1 (baseline) | 5.76 (± 1.76) | 5.81 (± 1.10) | -.04 [-.83, .74] | .930 |

| Time 2 | 5.82 (± 1.85) | 5.85 (± 1.71) | -.02 [-.98, .93] | |

| Time 3 | 5.56 (± 1.52) | 5.33 (± 1.33) | .24 [-.53, .99] | |

| HDL | ||||

| Time 1 (baseline) | 1.30 (± 0.46) | 1.27 (± 0.46) | .02 [-.22, .27] | .994 |

| Time 2 | 1.36 (± 0.44) | 1.29 (± 0.47) | .07 [ .18, .31] | |

| Time 3 | 1.22 (± 0.42) | 1.23 (± 0.42) | -.01 [-.23, .22] | |

| LDL | ||||

| Time 1 (baseline) | 3.47 (± 1.57) | 3.56 (± 1.30) | -.97 [-.87, .68] | .982 |

| Time 2 | 3.51 (± 1.78) | 3.51 (± 1.85) | .00 [-.97, .98] | |

| Time 3 | 3.52 (± 1.33) | 3.31 (± 1.38) | .22 [-.51, .95] | |

| Triglycerides | ||||

| Time 1 (baseline) | 2.09 (± 0.92) | 2.16 (± 1.00) | -.07 [-.59, .44] | .953 |

| Time 2 | 1.87 (± 0.95) | 2.01 (± 0.76) | -.14 [-.61, .32] | |

| Time 3 | 1.80 (± 0.74) | 1.77 (± 0.66) | .03 [-.34, .40] | |

The values for intervention- and control groups are means and standard deviation (SD)

*p-value are differences between groups from time 1 to time 3. Mean difference and 95% CI are independent t-test for total sample

Within the intervention group, there was a significant difference from time 1 to time 3: for the BMI (p = 0.046), the HbA1c level (p = 0.018) and the diastolic blood pressure (p = 0.03). Where for the control group only CHOL and TGL showed a tendency to significant difference from time 1 to time 3, both (p = 0.052).

Discussion

This RCT intervention found no statistically significant differences between the GSD intervention and control groups. The timeframe of 12–16 weeks of the GSD intervention and the total time of 9-months of this RCT, could only have been a motivation for a change process, as changes in lifestyle behaviour may require longer time [46]. By providing GSD in only three consultations, it may have been too short to demonstrate significant differences between groups [47]. However, the GSD approach have been found to promote lifestyle changes and may be a promising counselling method for people at T2D risk as here the NNT for a positive outcome in CHD risk was nine [20]. Also, in this RCT, the GSD was used for a group of people found at health risk aiming toward health promotion, where most prior research on GSD have focused on people with diseases [15, 48–50]. In addition, this RCT might have been influenced by unforeseen factors like the Covid-19 pandemic [51].

However, looking at the primary outcome of the ICE-HEART online calculator, results demonstrated that by participating in this RCT, 55% of the participants had lower CHD risk in the next ten years at time 3 measurement. Additionally, the absolute risk of CHD decreased by 10.7%. This is of interest as CVDs are the most common course of mortality [26]. The CVD risk increases with prediabetes as a meta-analyse comparing the absolute risk difference between those with prediabetes signs and those with normal blood sugar levels revealed a difference of 189.77 (95%CI: 117.97 – 271.85) in CVD risk. The difference for CHD and all-cause mortality risk was 4.62 (95%CI 5.42–78.549) [52].

The secondary outcomes showed not significant difference between groups. But, for the intervention group, diastolic blood pressure, BMI and HbA1c were significantly lower at time 3 than time 1. Lowering those outcomes may lower the risk of further development toward T2D and prevention of CVD [52]. Prior research indicates that the silent progression toward T2D may take several years and T2D risk may be reduced with preventive interventions [7].

The increase in BMI and T2D in Iceland is alarming [53]. For the BMI, being one of inclusion criteria for allocation, was found to be high in the prediabetes prevalence study (39.5% with BMI ≥ 30 kg/m[2]), this reflected the high BMI of the participants [21]. In addition, as BMI is a part of the ICE-HEART calculator, further studies are needed to find if the higher CHD mean risk in this trial reflects a higher mean CHD score in North Iceland, than found for same age and gender cohort behind the ICE-HEART calculator, which is based on data from the past 50 years [26, 27, 53],. This may indicate the need to further develop the ICE-HEART calculator. However, for the PHC the need for setting a public health agenda and strategy toward health promotion that might reduce risk factors is essential [27]. Therefore, the ICE-HEART CHD risk calculator, accessible online and easy-to-use, the calculator is useful for the PHC in consultations to provide individuals with their results of CHD risk, to increase the individual´s awareness of one´s own health status [27].

When preparing this trial, one of the objectives was to find individuals with undiagnosed T2D, but no one fulfilled these criteria, thus we could not compare individuals at T2D risk and undiagnosed individuals in this trail [21, 22]. However, with increasing prevalence of T2D it is important to establish that changes in lowering CHD risk factors and CVD risk can be made in PHC with low-cost interventions as GSD. Previous research has also shown that implementing uncomplicated lifestyle interventions in PHC settings can lower the relative risk of both CHD and T2D [46, 54, 55]. Additionally, it is important to mention that this RCT was conducted before the rise in use of Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) analogues, became as strong as has been observed [56].

To effectively combat the escalating global incidence of T2D and reduce the risk of CHD, it is crucial to raise awareness and empower individuals to take proactive actions to minimize their risk of developing these conditions [57]. To emphasize the need for setting a public health agenda and strategy toward health promotion that might reduce risk factors is essential [27]. In addition, research indicates that people showing indicators of prediabetes stage may be clustered to six groups of lower to higher risk of further progression to T2D. As the low-risk clusters may never proceed to T2D it may enable the PHC to focus on high-risk individuals and reduce risk of over-treatment [58]. The strong indicators of prediabetes risk of high BMI, high HbA1c and high score on FINDRISC may be used to find people at T2D risk. But, in using the FINDRISC score, considering that the cut-of-score of risk may vary between countries is important [21]. In prioritizing intervention for people at risk, methods like WHtR measurements, are a non-invasive way to give indication to higher health risk for the individual [22, 31, 34–36],. Lifestyle interventions have shown to lower the relative risk of T2D and found to be cost effective in the long run [12].

For the PHC the GSD may be a promising approach toward health promotion for people not yet with a manifest disease, though unable here to show significant difference between groups [59]. GSD may be tailored to increased health awareness for the public in preventing progress from prediabetes to a diabetes state. Preventions for T2D and CVD have been found cost effective [60]. Preventing or delaying progress to T2D actions as the GSD method, led by nurses, may therefore lower disease burden for individuals as well as having positive effects on the workload for doctors within the PHC, and lower cost for the society [19, 24, 48, 61, 62].As the GSD intervention was a completely new approach for the nurses who provided the counselling method, deeper educational and preparational processes might have been needed for the nurses. This needs further investigation. For the participants, in personal communication to the first author the participants expressed great satisfaction with being able to participate. Some said that participation had resulted in saving their lives, given them better health conditions, a better insight into one’s health, and awareness of healthy food choices. This is in line with results from prior research indicating that at improvements may be seen when person-centred approaches are used [15, 47, 48, 63].

We claim that the GSD can be recommended for the PHC as an alternative short intervention provided by nurses, even though unable to find significant difference between groups in this trail, the GSD method have been found to be effective for people with T1D, T2D and psychiatric challenges [59, 64], As well as increasing individuals at risk’s awareness of one’s own health status [47]. The GSD approach facilitates health promotion by assisting individuals in implementing changes in their everyday lives that may promote their health. Here the focus was on those identified as being at risk of illness, namely at the prediabetes stage. We claim that at the GSD may be a feasible option within the PHC, but the GSD needs to be integrated into general health promotion programs within the PHC. Additional research involving larger cohorts may be required to validate the efficacy of GSD in health promotion initiatives for individuals identified at risk for diseases such as elevated BMI, High cholesterol, hypertension, WtHR ≥ 0.5, all acknowledged as health-risk factors, to facilitate their capacity for change in health behaviours [20, 59, 65].

Strengths and limitations

Low dropout after first measurements and low number needed to treat to show success are found to be strength of this RCT.

Several challenges occurred during this RCT period and may have impeded the effectiveness of the study. Firstly, researching health promotion within the PHC context at the time of the Covid-19 pandemic restrictions may have influenced the results. For example, the pandemic may have impacted the willingness to participate, resulting in the highest dropout between enrolment and time 1. The daily life of participants may have been altered due to the pandemic, though dropout was low from time 1 to time 3 [51]. From time 1 to time 3 three rejected further participation (I:1/C:2) due to Covid pandemic. Some participants had to ask for a new pre-arranged time due to being sick of Covid-19. One in the control group had to withdraw further participation from the trial as a T2D diagnosis was revealed. But, for ethical reasons, participants were not obliged to give reason for dropout and those not attending the pre-arranged time did not have to give any reason.

Secondly, the small, self-selected sample with large age ranges, from 18 to 75 years, and short time frame of intervention, may have influenced that significant differences were not found between groups.

Thirdly, the intensity of the intervention, needing to take a break from work and fastening before coming for repeated measurements may have had an impact [64]. A limitation to this RCT is that in a small community participants could probability find out which group they belonged to. As the same study nurse met all the participants, informed the intervention group of the intervention, and took all measurements, this RCT was not blinded, that may have affected the results. This RCT might therefore be considered as a pragmatic RCT [66].

In addition, it might be regarded as “person centered care” and an intervention on its own for both groups that all participants met the same person repeatedly for all measurements [64]. Also, that all participants were provided results of one previous and present measurements might have caused bias in the research process, leading to awareness of changes between measurements. For the control group it could have affected measurements at time 3. In addition, research [17, 47, 59], has demonstrated positive results by participating in lifestyle research, as participation may have led to an increased awareness of own health status in both groups. Moreover, the information booklet and participation in outcome measurements may have been beneficial for the control group [64].

The participating nurses who provided the intervention had no prior experience of providing the GSD approach. Further studies are required on the teaching and preparation phase, to estimate if additional time was needed in integrating the new GSD counselling into practice. In addition, that the participants were not diagnosed with a disease, may have had an impact on their willingness to implement lifestyle changes into their daily life.

Conclusion

The GSD approach is a non-invasive and low-expensive counselling method for the PHC that resulted in reduction of BMI, HbA1c and diastolic blood pressure for the intervention group. The GSD approach facilitate behaviour change by assisting individuals in implementing changes in their everyday lives that may promote their health. This short GSD approach conducted by nurses can be recommended for people at increased health risk as a person-centred health promotion strategy. Although, this RCT failed to demonstrate significant differences between groups participation, it seems to be beneficial to lower CHD risk within the groups. Further studies are needed to explore deeper the use of GSD as a counselling approach for people at increased health risk toward health promotion in PHC. Using simple measurements to find people at CHD and T2D risk providing those found at risk with GSD counselling, may be a useful health promoting strategy.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

To all participants in the study. The statistical assistance of K. Ólafsson and B.E. Dagsdottir.

Limitation

Few participants had a negative impact on the research power. The covid-19 pandemic might also have had a negative impact on implementation of GSD and perhaps also willingness of participation.

Strength of the study

Low dropout after first measurement. To find people at risk simple measurements, using portable equipment, tests performed by nurses, may have positive effects on health promotion for people at T2D risk.

What this paper adds

This self-selected group at allegation was undiagnosed group but found at high CHD and T2D risk. GSD may be feasible and beneficial for prevention and health promotion within the PHC. It is possible to reduce CHD and T2D risk with simple low invasive and low-cost measurements.

What is already known on this subject

GSD has been tested with positive outcome for people with T2D, T1D and other conditions. Prediabetes stage includes increased CVD risk. The time lag from prediabetes stage to diagnoses of T2D may be approximately 7 years or more, indicating that there is time to have positive effects with health promoting interventions. Health promotion has shown positive effects on smoking habits, cholesterol, and other CHD risk factors.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA

Analysis of Variance

- ARR

Absolute Risk Reduction

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- BP

Blood Pressure

- CER

Control Event risk

- CHD

Coronary Heart diseases

- CHOL

Cholesterol

- CI

Confidence Interval

- CVD

Cardiovascular diseases

- EER

Experimental Event Rate

- FBG

Fasting Blood Glucose

- FINDRISC

Finnish Diabetes Risk score

- GLP-1

Glucagon-Like Peptide-1

- GSD

Guided Self Determination

- HbA1c

Hemoglobin A1c protein, Glycated Hemoglobin

- HDL

High density lipoprotein

- ICE-HEART

Icelandic heart Association's risk calculator (estimator of the probability to get coronary heart disease in the next 10 years)

- IFG

Impaired Fasting Glucose

- LDL

Low density lipoprotein

- NNT

Number needed to treat

- OR

Odds ratio

- PHC

Primary Health Care

- RCT

Random Control Trial

- RR

Relative Risk

- RRR

Relative Risk Reduction

- SD

Standard Deviation

- T2D

Type 2 Diabetes

- TRG

Triglycerides

- WHR

Waist-to-Hip Ratio

- WHtR

Waist-to-Height Ratio

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization, E.A., Á.K.S., T.S., M.G. and B.-C.H.K.; methodology, E.A., Á.K.S., T.S. and M.G.; software, E.A.; validation, E.A., Á.K.S., T.S., M.G. and B.-C.H.K.; formal analysis, E.A., Á.K.S. and T.S.; investigation, E.A.; resources, E.A. and Á.K.S.; data curation, E.A.; writing—original draft preparation, E.A., Á.K.S., T.S., M.G., and B.-C.H.K; writing—review and editing, E.A., Á.K.S., T.S., M.G. and B.-C.H.K.; visualization, E.A.; supervision, Á.K.S., T.S., M.G. and B.-C.H.K.; project administration, E.A., Á.K.S. and M.G.; funding acquisition, E.A. and Á.K.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the University of Akureyri research fund, Grant number R2003, R2223, the Akureyri Hospital research fund S193, and the Icelandic Nursing association scientific research fund B196.https://search.crossref.org/funding . NA

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Institutional Review Bord Statement: The present study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and with the approval of the Icelandic National Bioethics Committee (VSN), (VSN-19-080-V1 approved 14/01/2020). All participants received an informational letter and signed an informed consent form before participating. Trial registration: This study is a phase of the registered study ‘Effectiveness of Nurse-coordinated Follow-Up Programme in Primary Care for People at Risk of T2DM’ at www.ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01688359) (accessed on 30 December 2020).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Institutional review bord statement: The present study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and with the approval of the Icelandic National Bioethics Committee (VSN), (VSN-19-080-V1 approved 14/01/2020). All participants received an informational letter and signed an informed consent form before participating.

Informed consent statement: Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Trial registration: This study is a part of the registered study ‘Effectiveness of Nurse-coordinated Follow-Up Programme in Primary Care for People at Risk of T2DM’ at www.ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01688359) (accessed on 30 December 2020)

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ke C, Lipscombe LL, Weisman A, et al. Change in the relation between age and cardiovascular events among men and women with diabetes compared with those without diabetes in 1994–1999 and 2014–2019: A population-based cohort study. Diabetes Care. 2023;46(10):e200–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wong ND, Sattar N. Cardiovascular risk in diabetes mellitus: epidemiology, assessment and prevention. Nature Rev Cardiology. 2023;20(10):685–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jyotsna F, Ahmed A, Kumar K, et al. Exploring the complex connection between diabetes and cardiovascular disease: analyzing approaches to mitigate cardiovascular risk in patients with diabetes. Cureus. 2023;15(8):e43882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Albright AL, Gregg EW. Preventing type 2 diabetes in communities across the US: The national diabetes prevention program. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44(4):S346–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dimova R, Tankova T, Chakarova N, Groseva G, Dakovska L. Cardiovascular autonomic tone relation to metabolic parameters and hsCRP in normoglycemia and prediabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2015;109(2):262–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fayed A, Alzeidan R, Esmaeil S, et al. Cardiovascular risk among Saudi adults with prediabetes: a sub-cohort analysis from the heart health promotion (HHP) study. Int J Gen Med. 2022;15:6861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tabák AG, Herder C, Rathmann W, Brunner EJ, Kivimäki M. Prediabetes: a high-risk state for diabetes development. Lancet. 2012;379(9833):2279–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jakupovic H, Schnurr TM, Carrasquilla GD, et al. Obesity and unfavourable lifestyle increase type 2 diabetes-risk independent of genetic predisposition. Diabetologia. 2019;62(Suppl. 1):S188. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schlesinger S, Neuenschwander M, Barbaresko J, et al. Prediabetes and risk of mortality, diabetes-related complications and comorbidities: umbrella review of meta-analyses of prospective studies. Diabetologia. 2022;65:275–85. 10.1007/s00125-021-05592-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Lindström J, Peltonen M, Eriksson JG, et al. Improved lifestyle and decreased diabetes risk over 13 years: Long-term follow-up of the randomised Finnish diabetes prevention study (DPS). Diabetologia. 2013;56:284–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gilis-Januszewska A, Lindstrom J, Tuomilehto J, et al. Sustained diabetes risk reduction after real life and primary health care setting implementation of the diabetes in Europe prevention using lifestyle, physical activity and nutritional intervention (DE-PLAN) project. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:n /a. 10.1186/s12889-017-4104-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glechner A, Keuchel L, Affengruber L, et al. Effects of lifestyle changes on adults with prediabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prim Care Diabetes. 2018;12(5):393–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu J, Li W, Yao H, Liu J. Proactive health: an imperative to achieve the goal of healthy China. China CDC Weekly. 2022;4(36):799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zoffmann V, Harder I, Kirkevold M. A person-centered communication and reflection model: sharing decision-making in chronic care. Qual Health Res. 2008;18(5):670–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zoffmann V, Kirkevold M. Realizing empowerment in difficult diabetes care: a guided self-determination intervention. Qual Health Res. 2012;22(1):103–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seidu S, Walker NS, Bodicoat DH, Davies MJ, Khunti K. A systematic review of interventions targeting primary care or community based professionals on cardio-metabolic risk factor control in people with diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2016;113:1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zoffmann V, Prip A, Christiansen AW. Dramatic change in a young woman’s perception of her diabetes and remarkable reduction in HbA1c after an individual course of guided self-determination. Case Reports. 2015;2015:bcr2015209906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zoffmann V, Jørgensen R, Graue M, Biener SN, Brorsson AL, Christiansen CH, Due‐Christensen M, Enggaard H, Finderup J, Haas J, Husted GR. Person‐specific evidence has the ability to mobilize relational capacity: A four‐step grounded theory developed in people with long‐term health conditions. Nurs Inq. 2023;30(3):e12555. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Zoffmann V, Hörnsten Å, Storbækken S, et al. Translating person-centered care into practice: a comparative analysis of motivational interviewing, illness-integration support, and guided self-determination. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99(3):400–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mathiesen AS, Zoffmann V, Lindschou J, et al. Self-determination theory interventions versus usual care in people with diabetes: a systematic review with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. Syst Rev. 2023;12(158):1–22. 10.1186/s13643-023-02308-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arnardóttir E, Sigurðardóttir ÁK, Graue M, Kolltveit BH, Skinner T. Using HbA1c measurements and the Finnish diabetes risk score to identify undiagnosed individuals and those at risk of diabetes in primary care. BMC Public Health. 2023;23(1):211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arnardóttir E, Sigurðardóttir ÁK, Graue M, Kolltveit BH, Skinner T. Can waist-to-height ratio and health literacy be used in primary care for prioritizing further assessment of people at T2DM risk? Int J Env Res and Pub Health. 2023;20(16):6606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Statistic Iceland. Statistical Information about Iceland. Available online: https://www.statice.is/. Accessed 1 Feb 2023.

- 24.Jølle A, Midthjell K, Holmen J, et al. Impact of sex and age on the performance of FINDRISC: The HUNT study in Norway. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2016;4(1):e000217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Olafsdottir, A.S., Gisladottir, E., Thorgeirsdottir, H., Thorsdottir, I., Gunnarsdottir, I., Steingrimsdottir, L., Halldorsson, Th.I. Nutrition - Recommendations from the directorate of health: Dietary recommendations. ISBN 978–9979–9527–7–0. Updated 2021.

- 26.Andersen K, Aspelund T, Gudmundsson EF, et al. Five decades of coronary artery disease in Iceland. data from the Icelandic Heart Association. Laeknabladid. 2017;103(10):411–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aspelund T, Thorgeirsson G, Sigurdsson G, Gudnason V. Estimation of 10-year risk of fatal cardiovascular disease and coronary heart disease in Iceland with results comparable with those of the systematic coronary risk evaluation project. Europe J Cardiovasc Prev Rehab. 2007;14(6):761–8. 10.1097/HJR.0b013e32825fea6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Erdem E, Aydogdu T, Akpolat T. Validation of the medisana MTP plus upper arm blood pressure monitor, for self-measurement, according to the European society of hypertension international protocol revision 2010. Blood Press Monit. 2011;16(1):43–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.SPRINT Research Group. A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(22):2103–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fuchs FD, Whelton PK. High blood pressure and cardiovascular disease. Hypertension. 2020;75(2):285–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ashwell M, Gunn P, Gibson S. Waist-to-height ratio is a better screening tool than waist circumference and BMI for adult cardiometabolic risk factors: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2012;13(3):275–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nuttall FQ. Body mass index: obesity, BMI, and health: a critical review. Nutr Today. 2015;50(3):117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mirzaei M, Khajeh M. Comparison of anthropometric indices (body mass index, waist circumference, waist to hip ratio and waist to height ratio) in predicting risk of type II diabetes in the population of yazd, Iran. Diabet Metabol Syndr Clin Res Rev. 2018;12(5):677–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Browning LM, Hsieh SD, Ashwell M. A systematic review of waist-to-height ratio as a screening tool for the prediction of cardiovascular disease and diabetes: 0· 5 could be a suitable global boundary value. Nutr Res Rev. 2010;23(2):247–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ke J, Wang J, Lu J, Zhang Z, Liu Y, Li L. Waist-to-height ratio has a stronger association with cardiovascular risks than waist circumference, waist-hip ratio and body mass index in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2022;183:109151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang F, Ren J, Zhang P, et al. Strong association of waist circumference (WC), body mass index (BMI), waist-to-height ratio (WHtR), and waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) with diabetes: A population-based cross-sectional study in Jilin province, China. J diabet res. 2021;2021(1):8812431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.World Health Organization. World health organization. Use of glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) in diagnosis of diabetes mellitus: Abbreviated report of a WHO consultation (no. WHO/NMH/CHP/CPM/11.1). Use of glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) in diagnosis of diabetes mellitus: abbreviated report of a WHO consultation. 2011. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/70523/WHO_NMH_CHP_CPM_11.1_eng.pdf. [PubMed]

- 38.American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2022 abridged for primary care providers. Clinical Diabetes. 2022;40(1):10–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sacks DB, Arnold M, Bakris GL, et al. Guidelines and recommendations for laboratory analysis in the diagnosis and management of diabetes mellitus. Clin Chem. 2023;69(8):808–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.American Diabetes Association. Addendum. 2. classification and diagnosis of diabetes: standards of medical care in Diabetes—2021. diabetes care 2021; 44 (suppl. 1): S15–S33. Diab Care. 2021;44(9):2182. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Meijnikman AS, De Block C, Verrijken A, Mertens I, Corthouts B, Van Gaal LF. Screening for type 2 diabetes mellitus in overweight and obese subjects made easy by the FINDRISC score. J Diabetes Complications. 2016;30(6):1043–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lindstrom J, Tuomilehto J. The diabetes risk score: a practical tool to predict type 2 diabetes risk. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(3):725–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ranganathan P, Pramesh CS, Aggarwal R. Common pitfalls in statistical analysis: absolute risk reduction, relative risk reduction, and number needed to treat. Perspect Clin Res. 2016;7(1):51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pallant J. SPSS survival manual: A step by step guide to data analysis using IBM SPSS. 7th.ed. Routledge: 2020.

- 45.Schulz KF. CONSORT 2010 statemen: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(8):834–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saaristo T, Moilanen L, Korpi-Hyövälti E, et al. Lifestyle intervention for prevention of type 2 diabetes in primary health care: one-year follow-up of the Finnish national diabetes prevention program (FIN-D2D). Diabetes Care. 2010;33(10):2146–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Graue M, Igland J, Oftedal BF. et al. Interprofessional follow-up for people at risk of type 2 diabetes in primary healthcare – a randomized controlled trial with embedded qualitative interviews. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2024;42(3):450–62. 10.1080/02813432.2024.2337071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Linnet Olesen M, Jørgensen R. Impact of the person-centred intervention guided self-determination across healthcare settings—An integrated review. Scand J Caring Sci. 2023;37(1):37–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Burke KM, Raley SK, Shogren KA, et al. A meta-analysis of interventions to promote self-determination for students with disabilities. Remedial and Special Ed. 2020;41(3):176–88. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jørgensen R, Munk-Jørgensen P, Lysaker PH, Buck KD, Hansson L, Zoffmann V. Overcoming recruitment barriers revealed high readiness to participate and low dropout rate among people with schizophrenia in a randomized controlled trial testing the effect of a guided self-determination intervention. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nomali M, Mehrdad N, Heidari ME, et al. Challenges and solutions in clinical research during the COVID-19 pandemic: a narrative review. Health science reports. 2023;6(8): e1482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cai X, Zhang Y, Li M, et al. Association between prediabetes and risk of all cause mortality and cardiovascular disease: Updated meta-analysis. BMJ: British Medical Journal (Online). 2020;15(370):m2297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Thórsson B, Aspelund T, Harris TB, Launer LJ, Gudnason V. Trends in body weight and diabetes in forty years in Iceland. Laeknabladid. 2009;95(4):259–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rosenzweig JL, Ferrannini E, Grundy SM, et al. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes in patients at metabolic risk: An endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(10):3671–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lönnberg L, Ekblom-Bak E, Damberg M. Reduced 10-year risk of developing cardiovascular disease after participating in a lifestyle programme in primary care. Ups J Med Sci. 2020;125(3):250–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.de Oliveira Almeida, G., Nienkötter, T.F., Balieiro, C.C.A. et al. Cardiovascular Benefits of GLP-1 Receptor Agonists in Patients Living with Obesity or Overweight: A Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2024;24:509–21. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 57.Chaudhary RS, Turner MB, Mehta LS, Al-Roub NM, Smith SC Jr, Kazi DS. Low awareness of diabetes as a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease in middle-and high-income countries. Diabetes Care. 2024;47(3):379–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Prystupa K, Delgado GE, Moissl AP, et al. Clusters of prediabetes and type 2 diabetes stratify all-cause mortality in a cohort of participants undergoing invasive coronary diagnostics. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2023;22(1):211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zoffmann V, Lauritzen T. Guided self-determination improves life skills with type 1 diabetes and A1C in randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;64(1–3):78–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Siegel KR, Ali MK, Zhou X, et al. Cost-effectiveness of interventions to manage diabetes: Has the evidence changed since 2008? Diabetes Care. 2020;43(7):1557–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Oftedal B, Kolltveit BH, Zoffmann V, Hörnsten Å, Graue M. Learning to practise the guided self-determination approach in type 2 diabetes in primary care: A qualitative pilot study. Nurs Open. 2017;4(3):134–42. 10.1002/nop2.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bernabe-Ortiz A, Perel P, Miranda JJ, Smeeth L. Diagnostic accuracy of the Finnish diabetes risk score (FINDRISC) for undiagnosed T2DM in Peruvian population. Prim Care Diabetes. 2018;12(6):517–25. 10.1016/j.pcd.2018.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Olsson L, Jakobsson Ung E, Swedberg K, Ekman I. Efficacy of person-centred care as an intervention in controlled trials–a systematic review. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22(3–4):456–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Graue M, Igland J, Haugstvedt A, et al. Evaluation of an interprofessional follow-up intervention among people with type 2 diabetes in primary care—A randomized controlled trial with embedded qualitative interviews. PLoS ONE. 2023;18(11): e0291255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Peterson KA, Hughes M. Readiness to change and clinical success in a diabetes educational program. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2002;15(4):266–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gamerman V, Cai T, Elsäßer A. Pragmatic randomized clinical trials: Best practices and statistical guidance. Health Serv Outcomes Res. 2019;19:23–35. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Institutional Review Bord Statement: The present study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and with the approval of the Icelandic National Bioethics Committee (VSN), (VSN-19-080-V1 approved 14/01/2020). All participants received an informational letter and signed an informed consent form before participating. Trial registration: This study is a phase of the registered study ‘Effectiveness of Nurse-coordinated Follow-Up Programme in Primary Care for People at Risk of T2DM’ at www.ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01688359) (accessed on 30 December 2020).