Abstract

Background

Cataract surgery requires a high level of dexterity and experience to avoid serious intra- and post-operative complications. Proper surgical training and evaluation during the learning phase are crucial to promote safety in the operating room (OR). This scoping review aims to report cataract surgery training efficacy for patient safety and trainee satisfaction in the OR when using virtual reality simulators (EyeSi [Haag-Streit, Heidelberg, Germany] or HelpMeSee [HelpMeSee foundation, Jersey city, New Jersey, United States]) or supervised surgical training on actual patients programs in residents.

Methods

An online article search in the PubMed database was performed to identify studies proposing OR performance assessment after virtual-reality simulation (EyeSi or HelpMeSee) or supervised surgical training on actual patients programs. Outcome assessment was primarily based on patient safety (i.e., intra- and post- operative complications, OR performance, operating time) and secondarily based on trainee satisfaction (i.e., subjective assessment).

Results

We reviewed 18 articles, involving 1515 participants. There were 13 using the EyeSi simulator, with 10 studies conducted in high-income countries (59%). One study used the HelpMeSee simulator and was conducted in India. The four remaining studies reported supervised surgical training on actual patients, mostly conducted in low- middle- income countries. Training programs greatly differed between studies and the level of certainty was considered low. Only four studies were randomized clinical trials. There were 17 studies (94%) proposing patient safety assessments, mainly through intraoperative complication reports (67%). Significant safety improvements were found in 80% of comparative virtual reality simulation studies. All three supervised surgery studies were observational and reported a high amount of cataract surgeries performed by trainees. However, intraoperative complication rates appeared to be higher than in virtual reality simulation studies. Trainee satisfaction was rarely assessed (17%) and did not correlate with training outcomes.

Conclusions

Patient safety assessment in the OR remains a major concern when evaluating the efficacy of a training program. Virtual reality simulation appears to lead to safer outcomes compared to that of supervised surgical training on actual patients alone, which encourages its use prior to performing real cases. However, actual training programs need to be more consistent, while maintaining a balance between financial, cultural, geographical, and accessibility factors.

Keywords: Learning, Ophthalmic surgery, Patient safety, Prevention, Simulation, Surgical education, Surgical skills, Training programs, Trainee satisfaction, Virtual reality

Background

Cataract surgery is the most common surgical procedure in ophthalmology, with 20 million operations performed worldwide each year [1]. Cataract surgery represents 80–85% of all ophthalmic surgeries [2], and it is therefore a key element of surgical training in ophthalmology. Patient safety is closely related to the quality of this training. In most countries, cataract surgical training is based on traditional “learning on patients” apprenticeship models, where surgeries are performed on real patients in the operating room (OR). Training, however, has been undergoing a revolutionary change with the addition of virtual reality simulation-based (VRS) training, and the availability of VRS surgical training facilities has increased in many university hospitals [3, 4]. Postgraduate ophthalmology trainees who have not yet completed their specialty training (i.e., residents), can, however, struggle to find access to virtual reality simulators. This is mainly due to cost, as few virtual reality simulators are commercially available, and they can be expensive to use [5]. Thus, some residents may have no choice but to participate in traditional supervised surgical training on actual patients [6, 7].

There is a lack of evidence that skills learned during supervised cataract surgery on actual patients training leads to improved patient safety. In fact, no previous reviews of training efficacy include supervised surgical training programs. Moreover, supervised cataract surgical training outcomes have never been assessed alongside VRS training outcomes. We believe that such an assessment is valuable. There are two widely used virtual reality (VR) simulators that should be chosen for such a comparison: the EyeSi VR Magic (Haag-Streit, Heidelberg, Germany) and HelpMeSee (HMS, [HelpMeSee foundation, Jersey city, New Jersey, United States]) as each VR simulator varies greatly from each other, most notably for accessibility issues.

Supervised cataract surgery trainings on actual patients are offered in countries with high cataract surgery demand and a shortage of eye surgeons [6]. These are at the trainees’ expense and do not include VRS. The EyeSi and HMS virtual reality simulators have each been specifically designed for cataract surgery training, but the training design, purpose, and accessibility differ between the two simulators. EyeSi is a widespread, commercially-available cataract surgery simulator designed for phacoemulsification and vitreoretinal surgery self-guided training [8] that is mostly used in high-income countries (HICs) [9]. HMS focuses on resource-limited areas in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). HMS establishes local training centers mainly for manual small incision cataract surgery (MSICS), although phacoemulsification and vitrectomy modules are available. HMS training sessions are supervised by certified instructors. Courses are not limited to medical doctors, but also to allied health personnel where allowed, and they include a reimbursement system for trainees operating in resource-limited areas [6]. Despite their significant use, reports of HMS simulator outcomes are sparse compared to those of the EyeSi simulator. Although not included in this review, other simulation training methods for cataract surgery learning have been studied with encouraging efficacy results [10, 11], these include wet-lab training (i.e., using organic animal tissues, such as porcine eyes), and less frequently, dry-lab training (i.e., using synthetic materials). The efficacy of VRS over wet-lab and dry-lab training methods vary between studies, although efficacy results tend to be higher for VRS [12, 13].

Skill transfer in the OR and patient safety outcomes represent the two highest factors in Kirkpatrick’s model for the assessment of training program efficacy [14]. There is a lack of data on skill transfer from a simulation-based training to the OR in ophthalmology, as reported in 2015 [8]. In 2020, Lee et al. reported higher efficacy with the EyeSi virtual reality simulator compared to other training modalities for cataract surgery [12]. This finding was confirmed in Nayer et al.’s review, who added that there was less evidence of efficacy for other virtual reality simulators (MicroVisTouch [ImmersiveTouch, Chicago, IL, USA] and an in-house virtual reality phacoemulsification simulator). The HMS simulator was not included in these studies [15]. A review including six randomized controlled trials (RCTs) reported the higher efficacy of VRS training compared to no supplementary training in postgraduate trainees with uncertain evidence. The results were less consistent compared to those with wet-lab training [13]. Also, the assessment of trainee satisfaction during training represents the first level of Kirkpatrick’s model for training program efficacy and provides a complementary subjective assessment [8].

In order to provide a comprehensive picture of cataract surgery training efficacy and assessment in residents, this scoping review aimed to report on and evaluate the impact of three different widely used methods of surgical training (i.e., supervised surgery on actual patients, EyeSi virtual reality simulator, and HMS virtual reality simulator) primarily on patient safety in the OR, including complications and OR performance, and secondarily, on trainee satisfaction.

Materials and methods

The proposed scoping review was conducted in accordance with the JBI methodology for scoping reviews [16].

A comprehensive research strategy was designed to retrieve all articles of interest by combining [cataract surgery OR phacoemulsification OR MSICS OR ECCE] AND [Virtual Reality training AND (EyeSi OR HelpMeSee)] OR [live-surgery training program OR hands-on training program OR supervised training program] in the PubMed database. All studies published from inception to September 2023 with an English abstract and available full text were reviewed. All abstracts were read by one author (L.D.) who retrieved potentially eligible trials to be read independently in full by two authors (L.D. and T.B.). Eligibility was decided by committee. All selected studies proposed an assessment of OR performance (objective and/or subjective) after EyeSi or HMS or supervised surgery on actual patients trainings. Performance outcomes had to be assessed on patients operated in the OR. Studies reporting only performance outcomes outside of the OR (i.e., VRS performance, wet-lab performance) were excluded. Participants had to be ophthalmology trainees who had not yet completed their specialty training, or residents. All types of studies were included except reviews and meta-analyses.

Outcome evaluation was based on assessment of:

-

Patient safety (primary outcome):

- Intraoperative complications.

- Postoperative complications.

- Operating time in the OR.

- Surgical performance in the OR (objective assessment).

-

Trainee satisfaction (secondary outcome):

- Surgical performance in the OR (subjective assessment including performance improvement, comfort, and self-confidence in the OR).

Search results were compiled using Zotero (6.0.26) software (Zotero, Fairfax, Virginia, United States). Two experienced reviewers (LD, TB) screened the retrieved articles and extracted data from each eligible study using a standardized data extraction sheet following presence or absence of inclusion and exclusion criteria.

For each selected study, first author, publication date, study type, and country were retrieved. The following information on the methods were reported: training modality (EyeSi, HMS, or supervised surgical training on actual patients), defined groups (if applicable), number of participants per group, previous experience in phacoemulsification/MSICS, number of surgeries performed during the study, OR skills assessed, assessment tool, use of satisfaction questionnaire, and training sequence. The outcomes for each study were also reported for further discussion.

The accessibility of each training modality was reported according to the number of studies available, the number of countries and participants per countries involved, and facilitated access (duration, mentoring). The number of surgeries performed per participant in the selected studies was calculated as a surgical ratio (number of surgeries performed/number of participants). Costs and financial information were also reported when available.

Results

Study selection

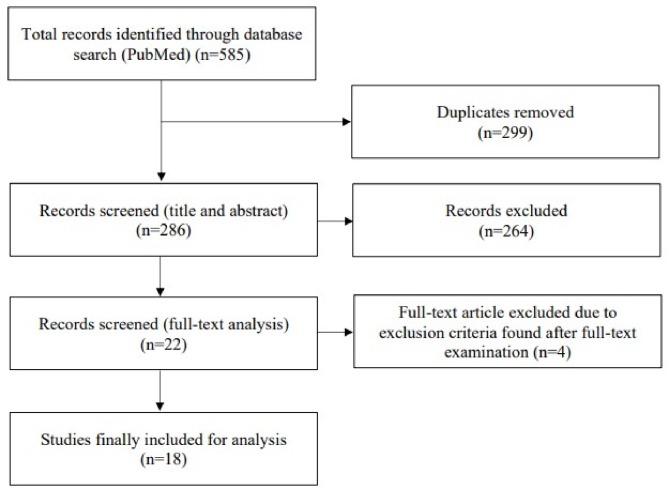

The database identified 585 articles. After removing 299 duplicates, 286 articles were reviewed based on title and abstract. Of these, 184 were excluded by the first reviewer (L.D.) for being out of the scope of this study (i.e., not about cataract surgery, not about surgical training, not evaluating ophthalmology trainees, not about EyeSi, HMS, or hands-on training on actual patients with supervision, not evaluating OR performance). There were 22 articles considered relevant and reviewed independently by L.D. and T.B.: 16 for the EyeSi simulator, two for the HMS simulator and four for supervised surgical training. Four articles were excluded for being of an inappropriate study type (i.e., review, metanalysis) or for exclusion criteria found after full-text examination. In total, 18 articles including 1515 participants were assessed for review. There were 13 evaluating the EyeSi simulator, one involving the HMS simulator, and four with supervised surgical training on actual patients. A study selection flowchart is presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart representing study selection

General information

Study setting

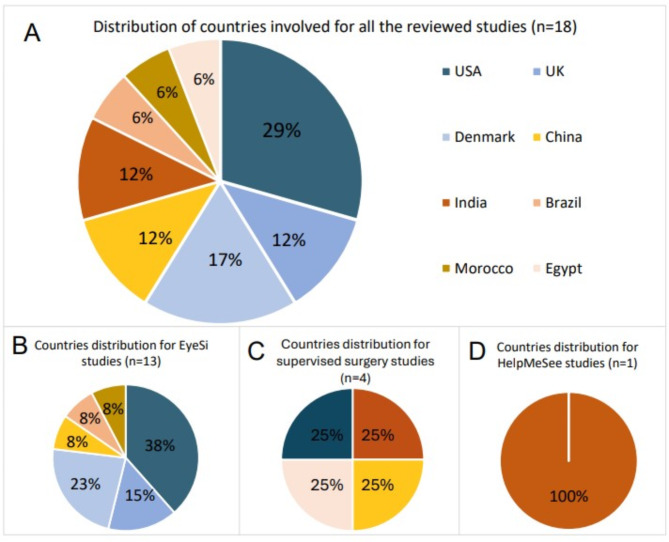

The reviewed studies were published from 2011 to 2023 and conducted in eight different countries. EyeSi studies took place in the United States (n = 5) [17–21], Denmark (n = 3) [21–23], the United Kingdom (n = 2) [24, 25], Morocco (n = 1) [26], China (n = 1) [27], and Brazil (n = 1) [28]. The HMS study took place in India [29]. The four studies which reported supervised training on actual patients took place in rural communities in China [30], India [31], Egypt [32], and the United States [33] (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Country distribution for all the reviewed studies (A), EyeSi studies (B), supervised surgery studies (C) and HelpMeSee studies (D)

Study design

Ten studies were randomized clinical trials (n = 4) [17, 23, 26, 29] or comparative studies (n = 6) [18–21, 25, 28], all using virtual reality simulators. In these studies, the control group was either a wet-lab training group [17] or a “without virtual reality simulator” group. The latter could involve wet-lab training in common with the simulator group [18–20], or no planned training [21, 26, 29], or the participants training themselves immediately before simulation training [23]. In two studies, participants who performed cataract surgeries prior to the purchase of an EyeSi simulator were included in the control [25, 28]. Four EyeSi studies were noncomparative and observational [22, 24, 27, 34]. Of the four supervised training studies, one was a case report [32] and the three others were retrospective non-comparative observational studies [30, 31, 33].

Surgical intervention and previous surgical experience

The EyeSi simulator was exclusively used for phacoemulsification training, the HMS simulator for MSICS. Two supervised surgical training studies evaluated phacoemulsification [31, 32] and one MSICS [30].

Three EyeSi studies required no previous phacoemulsification experience [19, 20, 28] and one study only minimal experience [24]. One EyeSi study voluntarily divided surgeons into four different levels of experience, including novice, intermediate, experienced, and expert participants (0, 1–75, 76–999, and > = 1000 independent phacoemulsifications previously performed, respectively) [23]. Only limited experience in MSICS prior to the study (< 20 MSICS procedures) was required in the HMS study [29]. No previous surgical experience requirements were imposed for the other included study. However, very low experience levels (< 20 cataract surgeries performed) were reported in three studies [21, 30, 34] and previous experience without details in the three other studies [17, 27, 31].

Number of participants and number of surgeries performed

The median number of participants in supervision surgical training studies was two [1–989], and one of the four supervised surgery studies did not specify the number of participants [33]. Two studies included only one and two participants, respectively [30, 32]. One study retrospectively reported the outcomes of 989 participants over a 9-year period after a specific phacoemulsification training program in Indian centers [31]. The median number of participants in VRS studies was 19 [3-265]. One EyeSi study was a 7-year audit database retrospective analysis which included 265 participants [25]. Apart from this study, the range of participants was three to 38. The median number of procedures performed per participant (surgical ratio) was 167 [58-1034] for supervised surgical training, and 20 [1-301] for VRS training (20 [20] for the HMS study and 18 [1-301] for EyeSi).

Training program modalities

VRS training programs varied greatly between studies. Numerous studies included didactic lectures prior to the training, lasting from 10 min to 2 h [19, 22, 27, 29, 34]. Warm-up sessions [22, 23, 26, 34], wet-lab [19, 20, 24] or dry-lab [29] sessions sometimes preceded the VRS program. Prior extraocular surgery practice was also included [24]. Training on the simulator variously included: (1) preselected modules to be performed without time limits [22, 23, 28, 34]; (2) preselected modules with milestones to be reached granting access to the next module, with [19] or without time limits [17, 18, 27]; and (3) only a minimum duration of practice on the simulator [20, 21, 24, 26, 29]. The modules proposed and training duration were not specified in one study [25]. HMS included e-Book reading, e-learning courses, classroom instructions, dry-lab activities, VRS (80% of the program), and a supervised surgery phase on actual patients [29]. Hands-on training courses with supervised surgery phases on actual patients lasted several weeks (up to 3 months) [30]. Additional training preparations included didactic lectures [30–32], wet-lab activities [30, 31], OR, or video observations [31, 32], conference attendance, and discussions [31]. supervised surgeries on actual patients were conducted as a stepwise approach in the OR [31] and sometimes included postoperative examination as part of the training [32].

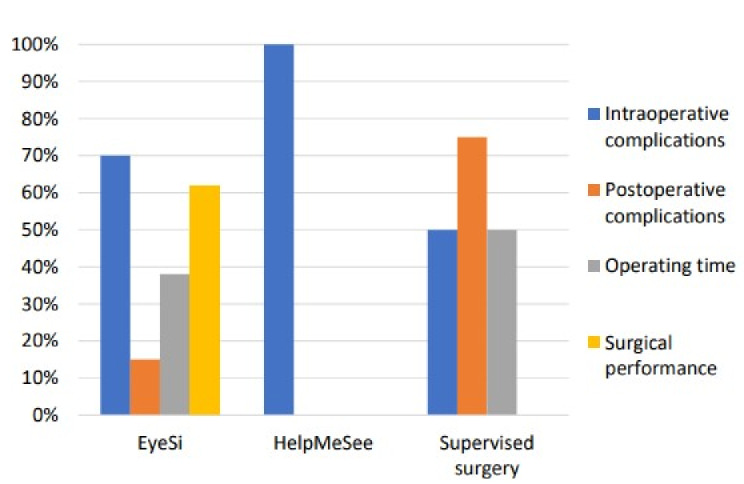

The characteristics and outcomes of the selected studies are detailed in Table 1. The distribution of patient safety assessment parameters used according to surgical training type is presented in Fig. 3.

Table 1.

Characteristic and outcome distribution within the selected studies, according to surgical training type

| Characteristic and outcome distribution | EyeSi VRS studies (n = 13) |

HMS VRS studies (n = 1) |

Supervised surgery studies (n = 4) |

Total (n = 18) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | ||||

| No. of participants | 504 | 19 | 992* | 1515 |

| Study design | ||||

| RCT | 3 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| Retrospective comparative | 6 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| Prospective noncomparative | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Retrospective noncomparative | 3 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| Case report | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Surgical intervention | ||||

| Phacoemulsification | 13 | 0 | 2 | 15 |

| MSICS | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Previous experience in cataract surgery | ||||

| Yes | 8 | 1 | 2 | 11 |

| No | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Not available | 1 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| Patient safety outcomes (No. comparative studies) | ||||

| Intraoperative complications | 9 (8) | 1 (1) | 2(0) | 12 |

| Postoperative complications | 2 (1) | 0 | 3(0) | 5 |

| Operating time in the OR | 4 (3) | 0 | 1(0) | 5 |

| Surgical performance in the OR | 8 (6) | 0 | 0 | 8 |

| None of the above outcomes | 0 | 0 | 1(0) | 1 |

| Trainee satisfaction outcomes | ||||

| Surgical performance in the OR | 3(2) | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| No. comparative studies with significant results for patient safety outcomes (%) | ||||

| Intraoperative complications | 7 (88%) | 1 | / | 8 |

| Postoperative complications | 1 (100%) | / | / | 1 |

| Operating time in the OR | 2 (66%) | / | / | 2 |

| Surgical performance in the OR | 4 (67%) | / | / | 4 |

HMS, HelpMeSee; MSICS, manual small incision cataract surgery; OR: operating room; RCT, randomized controlled trial; VRS: virtual reality simulation

*The number of participants was available in only three out of the four studies

Fig. 3.

Proportion of studies assessing patient safety parameters according to simulation training method

Primary outcome of the study

Intraoperative complications

We found 12 studies (67%) reporting intraoperative complications, including 10 VRS studies (nine with EyeSi, one with HMS) [17–21, 24–26, 28, 29] and three supervised surgery studies [30, 32, 33]. Of the ten EyeSi studies, four reported significant decreases in the number of intraoperative complications after VRS training, mostly for posterior capsular rupture (PCR) and vitreous prolapse [19, 25, 26, 28]. One study reported a lower PCR rate compared to that of first year residents in the literature [24]. The median PCR rate in the reported studies was 2.6% [1–10%]. A decrease in errant continuous curvilinear capsulorhexis (CCC) was found after intensive CCC training [18]. The number of intraoperative errors during MSICS decreased after the HMS training program [29].

The median PCR rate in supervised surgery trainings was 8% [2–15%], including cases of vitreous loss [30, 32, 33]. In two of these studies, the intraoperative complication rate decreased at the end of the training period (lasting 2 weeks and 2 to 3 months, respectively) [30, 32].

Postoperative complications

Postoperative findings were reported in three out of the four supervised surgery training studies (n = 2) [30, 32, 33]. Only two VRS studies (EyeSi) included postoperative complication assessment [19, 24]: One reported no significant decrease in postoperative complications after passing two beginner modules on the EyeSi simulator [19]; the other did not report any postoperative complication in a single group that trained for 50 h on the EyeSi simulator [24].

In three supervised surgery training studies, postoperative findings were reported in patient records or participant logbooks. Significant visual acuity improvement (uncorrected, with pinhole or best corrected visual acuity) was observed [30, 32, 33]. One study reported 25% of borderline or poor pinhole correction visual acuity, which was mainly related to refractive errors (42%), preexisting ocular comorbidities (25%), posterior capsular opacification (6%), macular edema (4%) or corneal edema 1% [30].

Operating time

Five studies reported operating times: four comparative studies (EyeSi) [17, 20, 21, 26] and one case report (supervised surgery on actual patients) [32]. Two EyeSi studies reported reduced operating times in the simulation group compared to the control group (no simulation) [21, 26]. In the first EyeSi study, a minimum of 2 h of VRS per year was required, while in the other EyeSi study, a 30-hour simulation program was performed over 6 weeks. In this latter study, operating time became comparable with the control group during the last five cataract surgeries (out of 25) [26]. One study reported shorter times for performing CCC in a wet-lab control group [17] compared to the VRS group that attended a 4-module course on the simulator [17]. One study reported a difference only after the first 10 cases of cataract surgery were performed in favor of the VRS group [20]. In the supervised surgery case, operating times decreased during the 4-week course [32].

Surgical performance

Surgical performance assessment was primarily reported in the EyeSi studies (eight out of the 13 studies) [20] and was the main outcome in six [17, 18, 21, 26, 27, 34]. Three studies specifically assessed CCC performance [17, 18, 26]. The first study did not find any differences in CCC performance when comparing VRS to wet-lab training courses [17]. The second study reported less errant CCC in trainees who completed an intensive CCC course on the EyeSi [18]. The third study reported trainees from the simulation group less likely to have a small and poorly centered CCC [13, 26].

Several other parameters, such as total ultrasound time or cumulative dissipated energy, were assessed [21, 26]. One study reported improvement in cumulative dissipated energy management after VRS [26], another study reported lower percentage phaco power [21].

Objective Structured Assessment of Cataract Surgical Skill (OSACSS) was used in two studies to grade each step of the surgery on video records. One study correlated OSACSS with a validated test score on EyeSi simulator [34]. The other study reported significant improvement of OSACSS in novices and intermediate trainees after performing a validated test on the simulator. Results were not significant for experienced and expert trainees [23].Thomsen AS et al. used a motion tracking system to evaluate path length and number of movements during OR surgery. The motion tracking score correlated with the simulator test score [22].

In the Pokroy et al. study, surgical performance was assessed as a secondary outcome by senior surgeons using a survey. They reported less need for intervention by an attending physician and improvement of CCC performance in the simulator group [20].

Surgical training methods, participant distribution, and results for patient safety assessment are listed in Tables 2 and 3 for comparative and non-comparative studies, respectively.

Table 2.

Characteristics and outcomes of comparative studies comparing the effect of training (VR simulation only) to other simulation model or no training for patient safety parameters

| Author | Year | Type of surgery | Simulation training | Control training | No. of participants | No. of surgeries |

Previous surgical experience | Primary outcomes | Primary outcome results for simulation vs. control group (p value) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SG | CG | SG | CG | ||||||||

| Adnane+ | 2020 | PKE | 5 h/week on EyeSi during 6 weeks | No training | 6 | 6 | 150 | 150 | No | OT; errant CCC rate; PCR rate; CDE |

OT: 20 vs. 37 min (p < 0.05*); CCC: 6.7 vs. 14.7% (p value not specified); PCR rate: 8 vs. 24.7% (p = 0.001*); CDE: 8.1 +/- 1.8 vs.18.7 +/- 2.2 (p < 0.001*) |

| Belyea | 2011 | PKE | ≥ 2 h/year on EyeSi from its acquisition | No training (before acquisition of EyeSi) | 17 | 25 | 286 | 306 | Yes (< 20 PKE in mean) | Phaco time; percentage phaco power; complication rate |

Time: 1.9 [0.1–7.2] vs. 2.4 [0.04–8.3] min (p < 0.002*); Phaco power: 25.3 vs. 28.2% (p < 0.0001*); Complication rate: 25.3 vs. 28.2% (p < 0.0001*) |

| Daly+ | 2013 | PKE | 4 CCC training modules on the EyeSi | Wet-lab training (CCC in silicone eyes) | 11 | 10 | 11 | 10 | Yes (half of the participants) | CCC performance (12-item score) | CCC performance score: -1.05 vs. 1.16 (p = 0.608) |

| Ferris | 2020 | PKE | After access to EyeSi simulator (selected centers) | Before access to or with no access to EyeSi simulator (selected centers) | / | / | 6848 after EyeSi | 6919 before EyeSi/ 2264 without EyeSi | Yes | PCR rate | PCR rate: after vs. before access to EyeSi: 2.6 vs. 3.5% (p = 0.001*); after vs. no access to EyeSi: 2.6 vs. 3.8% (p = 0.002*); before vs. no access to EyeSi: 3.5 vs. 3.8% (p = 0.55) |

| Lucas | 2019 | PKE | After the acquisition of EyeSi simulator (CAT-C level completed) | Before the acquisition of the simulator | 7 | 7 | 70 | 70 | No | Intraoperative complications rate in the first 10 PKE |

Total rate of complications after vs. before access to EyeSi: 12.9 vs. 27.1% (p = 0.031*); for PCR rate: 10 vs. 18.6% (p = 0.14) |

| McCannel | 2013 | PKE | Post-intervention cohort (some EyeSi use or intensive CCC training: 33 steps CCC training) | Baseline cohort: no EyeSi use | 23 | 25 | 603 | 434 | Not specified | Rate of errant CCC | -68% reduction of errant CCC in post intervention vs. baseline cohort (5 vs. 15.7%; p < 0.0001*) |

| Nair+ | 2021 | MSICS | 6-day training (35 h) with 80% HMS simulator and one supervised surgery phase on actual patients | Standard training from the institution with mentor surgeon | 10 | 9 | First 20 MSICS | First 20 MSCIS | Yes (< 20 MSICS) | Intraoperative errors during the first 20 MSICS | Number of total errors: 9.3 vs. 17.6 (p = 0.05*); rate of major errors: 4.9 vs. 10.1 (p = 0.02*) |

| Pokroy | 2013 | PKE |

6 h training on EyeSi within the first 18 months of residency. Wet lab in both groups |

No VRS training. Wet lab in both groups |

10 | 10 | 500 | 500 | No | OT; incidence of PCR during the first 50 PKE |

OT : 40.6 +/- 16.5 vs. 41.8 +/- 15.8 min (p = 0.1); PCR rate: 35 vs. 40% (p = 0.63) |

| Staropoli | 2018 | PKE |

CAT-A and CAT-B modules completed on EyeSi. Wet lab in both groups |

No simulation training. Wet lab in both groups |

11 | 11 | 501 | 494 | No | Intraoperative complication rate |

Complication rate: 2.4 vs. 5.1% (p = 0.037*); PCR rate: 2.2 vs. 4.8% (p = 0.032) |

| Thomsen | 2017 | PKE | Three cataract surgeries after proficiency-based test on EyeSi | Three cataract surgeries before proficiency-based test on EyeSi | 18 | 18 | 3 | 3 |

Novice = 0 Intermediate = 1–75 Experienced = 76–99 Expert = > 1000 |

Performance of the entire surgery (OSACSS score) | Improvement of OSCASS score after EyeSi test significant for novice (+ 5 points or + 32%) and intermediate (+ 9.8 points or + 38%) groups, not significant for experienced and expert groups |

+Randomized Control Trials; *Statistically significant (p < 0.05)

CAT, cataract; CCC, continuous curvilinear capsulorhexis; CDE, cumulated dissipated energy; CG, control group; HMS, HelpMeSee; MSICS, manual small incision cataract surgery; OSACSS, Objective Structured Assessment of Cataract Surgical Skill; OT, operating time; PCR, posterior capsular rupture; PKE, phacoemulsification; SG, simulation group; VR, virtual reality

Table 3.

Characteristics and outcomes of non-comparative studies reporting the effect of surgical training (VR simulation or supervised surgery on actual patients) on patient safety parameters

| Author | Year | Type of surgery | Cataract training | No. of participants | No. of surgeries | Previous surgical experience | Primary outcomes | Measurement tool | Results for primary outcomes (p value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baxter | 2013 | PKE | 3-year program: 50 h of EyeSi simulator + extraocular surgeries on actual patients (2 years); PKE training (1 year) | 3 | 903 | Yes (minimal) | Complication rate and case number after the first 2 years | Video record of PKE; report and analysis of complications to director | Number of cases: 150 after 6 months and 250 after 1 year; PCR rate of 1% after 6 months and 0.66% after one year |

| Farooqui | 2013 | PKE | 2-week program including wet lab; cataract surgeries on actual patients by Day 7 | 989 | 1,022,508 | Yes (MSICS mainly) | Report PKE surgeries performed by trainees over 9 years, for at least one year after the training | Not specified | 1,022,805 PKE performed in 9 years after training completion; 90% of participants continued to perform PKE after 9 years |

| Huang | 2013 | MSICS | 1-week wet lab, then surgery (up to 2–3 months) | 2 | 334 patients | Yes (very low) | Outcomes of cataract surgery performed by novices during training program | Patients examination by trained interviewers | Rate of good outcome (i.e., PHVA ≥ 6/18): 85%; rate of good uncorrected VA: 75%; rate of correctly estimated postoperative refraction: 25%; rate of PCR: 15% |

| Jacobsen | 2019 | PKE | 3 cataract surgeries on patients, then EyeSi training (validated test of 7 modules rated on 100 points); including surgeons of different levels of experience | 19 | 57 (including incomplete surgeries) | Yes | Correlation between VR performance and surgical performance (scored with adapted 13 items OSACSS) | Videos records (three masked assessors) | Correlation between total simulator score and OSACSS across all experience levels (R2 = 0.42; p = 0.003*) |

| Lynds | 2018 | MSICS | MSICS procedures performed by a resident as first surgeon with 1 attending between 2005 and 2012 | Not specified | 52 | Not speficied | Intra and postoperative outcomes and complications (reported) | Pre and post operative reports | Visual acuity improvement (p < 0.001); 9.6% peri operative complications and 23% post operative complications |

| Ripa | 2023 | PKE | 4-week training with at least 2 daily cataract surgeries on actual patients | 1 | 58 | Not specified | Report one trainee’s experience gain in training program | Logbook (patients details, procedures observed and performed) | PCR rate: 8.6%; decrease of operating time during last week of training compared to first week: 48.8 +/- 9.7 vs. 19.3 +/- 1.3 min (p = 0.046*) |

| Thomsen | 2017 | PKE | 3 cataract surgeries on patients, then EyeSi training (validated test of 7 modules rated on 100 points) | 11 | 33 | Yes | Correlation between OR performance and EyeSi simulator performance | Video records, motion tracking system | Correlation between simulation-based test score and motion tracking score (R2 = 0.43; p = 0.01*7) |

*Statistically significant (p < 0.05)

CAT, cataract; CCC, continuous curvilinear capsulorhexis; CDE, cumulated dissipated energy; MSICS, manual small incision cataract surgery; OR, operation room; OSACSS, Objective Structured Assessment of Cataract Surgical Skill; PHVA, pinhole visual acuity; PCR, posterior capsular rupture; PKE, phacoemulsification; VR, virtual reality

Secondary outcome of the study

Few of the selected studies used satisfaction questionnaires (n = 3). One study proposed a survey based on the International Council of Ophthalmology’s Ophthalmology Surgical Competency Assessment Rubrics (ICO-OSCAR) to be completed by the trainees as a “perceived difficulty” score [27]. Higher mean perceived difficulty scores were reported for important steps of the surgery in the group without prior EyeSi training. Two other studies proposed a satisfaction questionnaire as a secondary outcome. One study compared the impact of EyeSi and wet-lab training on performing CCC in a human patient, resulting in satisfaction scores equivalent between the groups, except for instrument use, for which the wet-lab group felt more prepared [17]. One study reported the confidence of trainees after VRS training, with 63% feeling somewhat prepared and 36% feeling well prepared for cataract surgery. For 91%, VRS training was considered mandatory before performing OR surgeries [19].

Discussion

This review assesses OR performance after cataract surgical training using either VRS (EyeSi or HMS) or supervised surgery training on actual patients, assessing patient safety as the primary outcome and trainee satisfaction as the secondary outcome.

Setting and accessibility of the reported training

The general study setting differed greatly across the 18 included studies (see Fig. 2). EyeSi studies mostly took place in high-income countries (HICs) (77%). Due to the high cost of this commercially-available simulator, it has mainly been purchased in HICs, especially the United Kingdom and the United States [5]. Only a few EyeSi simulators are located in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), mainly in Turkey and China [5]. The HMS virtual reality simulator, on the other hand, is not commercially available, and as reported herein [29], primarily found in LMICs [35]. Specific courses for cataract surgery training are funded by HelpMeSee, Inc., or other foundations in resource-limited areas. The higher number of EyeSi simulators in HICs, over the lower number of HMS simulators in LMICs, illustrates the unequal access to this technology. Cost issues (i.e., acquisition and maintenance) has unsurprisingly been reported as one of the main barriers to the implementation and uptake of simulation-based training programs [36]. Alternative simulation techniques might be used in LMICs or resource-limited communities like synthetic eyes [37] or wet-lab courses on animal eyes [38, 39]. Low-cost virtual reality simulators have been used in oncology as an alternative to complex surgical procedures [40]. Other solutions might be to share the simulator costs across teaching centers [41] or remotely evaluate trainees to avoid travelling costs [42]. Nevertheless, virtual reality systems allow multiple procedures to be performed without wasting consumables, leading to lower recurring costs compared to wet-lab training [43]. Unfortunately, none of the reviewed studies did propose an evaluation of the training programs costs and the profitability of such an investment in trainees’ formation.

Differing access to virtual reality simulators (EyeSi) also exist within HICs [9, 44]. In the United Kingdom, less than half junior doctors report having access to a surgical skill simulator, depending on their location [44]. For those who have access, the time and finance allotted for simulation activity appears minimal [45–47].

Given such difficulty to accessing simulation devices, supervised surgical training on actual patients may represent a low-cost alternative for training. Although these studies mostly took place in LMICs, there are not many, which suggests that this type of training program is rarely reported, compared to simulation training programs.

Surgical intervention

Phacoemulsification was the main type of surgery assessed in the included studies (see Table 1). This high-tech and relatively expensive technique for lens removal has demonstrated high efficacy and low complication rates, making it the preferred type of intervention taught in developed countries and tertiary centers in developing countries [48, 49]. The machinery and instruments required, however, is not available everywhere. MSICS was proposed in three studies that took place in India (HMS study), rural China, and the United States (supervised surgery studies) [29, 30, 33].MSICS has shown comparable outcomes to phacoemulsification [50, 51], and it represents by far the most frequent type of surgery performed in areas with high demand for cataract surgery [52]. Of note, the supervised surgery study conducted in the United States proposed MSICS training for residents who wanted to spend time in LMICs [33]. The HMS virtual reality simulator offers MSICS training in LMICs to both ophthalmologists and non-ophthalmologists [53]. Nevertheless, a phacoemulsification simulation-based training course is also available on the HMS simulator, offering choices for surgeons in LMICs [54].

Study design

All the supervised surgery studies provided low evidence certainty (noncomparative and observational, including one case report) [30–32]. Thus, the results must be interpreted with care. VRS studies (EyeSi and HMS) were mainly comparative, lending results of higher certainty of evidence. However, small sample sizes and limitations of study design, implementation, and reporting were pointed out in a recent review including several of these studies [13]. Larger prospective studies are required to confirm patient safety improvement with the use of both EyeSi and HMS.

Outcome assessment and results of the studies

Primary outcomes

Intra- and post-operative complications

All the reviewed studies, except one [31], reported patient safety assessment parameters. Intraoperative complication rates were the most frequently used (67%) (see Table 1; Fig. 3). Intraoperative complications were associated with poor visual outcomes and increased risk of serious postoperative complications, like endophthalmitis or retinal detachment [55, 56], which make their assessment relevant. Postoperative complications, however, were rarely assessed, as reported in previous reviews [13, 15], probably for practical reasons as this requires additional follow-up visits [57, 58]. In the present review, post-operative complications were more frequently reported in supervised surgery studies where participant logbooks or patient records were used [30, 32, 33].

In the reviewed studies, the intraoperative complication rate were not systematically reduced after surgical training [20, 21]. In the literature, many studies struggled to demonstrate a clear decrease in intraoperative complication rate after VRS training [13, 59]. This could be due to the great heterogeneity of currently proposed training programs. Virtual reality simulators enable repeated training on one or several steps of the surgery without requiring any equipment or consumables, or risking injuring patients, which renders numerous training options possible. For instance, intensive targeted training on CCC (i.e., using 33 modules) has been seen to help reduce the rate of errant CCC in trainees [18]. This was not the case with shorter CCC VRS training programs (i.e., using four modules) [17]. In other surgical specialties, immersive VRS training programs were utilized and showed positive results for patient safety [60]. Considering the entire surgical procedure, spaced-out sessions on a virtual reality simulator (i.e., spread over more than 6 months [20, 21]) did not significantly reduce complication rates, while studies reporting high minimal training duration (> 30 h) concentrated in a shorter period of time (several weeks) did find such a reduction [24, 26, 29]. In two studies, supervised cataract surgeries on real patients were proposed, which could have improved surgical performance and contributed to a decrease in intraoperative complications [24, 29]. Some studies did not outline the training program and its duration [25]. Overall, training heterogeneity between studies made it difficult to draw strong conclusions about efficacy. Some aspects of training programs might have been overlooked and led to ineffective training, as reported in a recent study [61]. Simulation-based education programs can be embedded into a curriculum in simulation centers that adheres to specific accreditation standards to increase the positive outcomes of training on patient safety.

The supervised surgery studies reported intensive cataract surgery training with high number of surgeries performed by the trainees. Intra- and post-operative complications were frequently reported (75%): complication rates were relatively high compared to VRS studies (median PCR rate of 8% vs. 2.6%, respectively), and to those reported in the literature for resident-performed phacoemulsifications (1.8%) [62]. Also, the rate of complications in supervised surgery studies was consistent with the one found in rural areas from developing countries. This highlighted a disparity between those regions and wealthier urban areas in developing countries [30, 63]. The geographical location of supervised surgical training on actual patients tended to be associated with higher rates of complications and poorer outcomes for patients. Also, none of the supervised surgery studies assessed surgical performance, while they tracked the number of surgeries performed during and after the training.

Surgical performance

Objective assessment of surgical performance was proposed in 44% of the studies (n = 8) [17, 18, 20–23, 26, 34]. The OSACSS assessment score was used in two studies [22, 33]. The OSACSS scoring system is a recommended, fast-to-complete technical-skill scoring system in ophthalmic surgery, along with ICO-OSCAR [63]. It is commonly used to assess surgical performances on actual patients, beyond cataract surgeries [15, 50]. OSACSS construct validity has been demonstrated for trainee surgeons with low levels of experience in phacoemulsification surgery (less than 50 or 250 procedures performed) [64]. Interestingly, Thomsen et al. found significant improvement of OSACSS score after VRS training in novice and intermediate surgeons (i.e., less than 75 procedures performed), but not in more experienced ones [23]. This score has also been adapted and validated to evaluate cataract surgery during VRS [64] to indicate whether surgeons practicing on the simulator are ready to practice in the OR [65–67]. ICO-OSCAR-phaco, which is based on OSACSS, includes behavioral anchors for each level at each step of the surgery [68] and is the most widely-used tool for the assessment of phacoemulsification. Targeted assessment scores were also used, notably for CCC [17, 18]. There is currently no widely-accepted CCC assessment score, and other studies proposed using specific steps of the ICO-OSCAR score [69].

Motion tracking software parameters (total path length and number of movements) obtained from a video of the microscope view were used in one study [22]. This system differentiated novice from expert surgeons, as the former showed greater path length and number of movements during surgery [70]. Similarly, one recent study assessed instrument position under the microscope during a corneal suturing procedure. However, no difference was found between expert and novices, which was attributed to the short duration of the surgical step [71]. Body movements and muscular force have been assessed by simple video record, electromyogram (EMG) sensors, and appropriate dynamometer, respectively [71–73]. Finally, the parameters of the phacoemulsification machine were reported [23, 34]. Phacoemulsification parameters have a significant impact on patient safety. Although high cumulative dissipated energy (EDC) might not influence postoperative visual acuity results [74], it is associated with postoperative complications, like cystoid macular edema [75].

Overall, various assessment tools for the quality of cataract surgery have been developed and used among studies. Because of this variability of assessment tools, it was difficult to compare studies regarding training methods. Even though the ICO-OSCAR and OSACSS are the most commonly used, further standardization of measurement tools would aid in future comparison studies [64].

Operating time

Operating time was considered a primary outcome in this study as the prolonged duration of a surgery increases the likelihood of complications [76, 77]. Operating time was not systematically recorded, although it would not be difficult to measure. Several VRS studies did not show reduction in operating times after training [17, 20]. Those studies did not find significant results for other safety assessment parameters either, suggesting the design or structure of the training courses was not efficient. In the literature, phaco time modification after surgical simulation is rarely assessed [15]. VRS is widely used in other surgical specialties and is associated with reduced operating times. Nevertheless, such a reduction in surgical time does not yet correlate with improved surgical outcomes [78]. Only one small study showed a decrease in operating time for one participant [32].

Trainees’ previous experience

Eight comparative VRS studies included trainees with minimal surgical experience (< 20 complete cataract surgeries) [19–21, 23, 24, 26–28]. Those studies reported an improvement of patient safety outcomes. This was not the case for one VRS study including more experienced trainees [23]. Many of the included studies did not clearly detail trainee experience levels [17, 18, 24, 27, 32], so it is difficult to ascertain the impact of the training alone.

Secondary outcome

Assessment of trainees’ satisfaction was rarely reported. In fact, the studies were more likely to emphasize objective cataract surgery assessment. When subjective questionnaires were collected, the effect of VRS was not clearly demonstrated. Resident satisfaction with VRS training was similar to that of wet-lab training [17] and only a small percentage of trainees (36%) felt well prepared after VRS training [19]. Also, subjective questionnaires can provide different results from objective assessments [19], suggesting they might be affected by external factors (e.g., coffee service or time schedules) more than the specific learning outcomes.

Validated questionnaires have been designed to increase the reliability and reproducibility of trainees’ satisfaction assessment. They are based on literature review, the content validity index, and Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for reliability estimation [79, 80]. However, there is no such questionnaire available for ophthalmology simulation training. The use of the recommended ICO-OSCAR technical skill scoring system in ophthalmic surgery was proposed in one study to create a trainees’ “perceived difficulty” score [27]. Otherwise, “homemade” post-teaching questionnaires are used in some studies, in association with the objective assessment of one surgical skill [81, 82].

In this study, several results indicated that training with a virtual reality simulator can help increase patient safety in the OR, enhance the precision of hand movements during surgery, and increase trainees’ self-confidence [17, 19, 21, 24–29, 34]. There is no standardized protocol on how to use the simulator before beginning to operate on real patients. Virtual reality simulators can be useful to address specific needs when training on one particular step of the surgery is necessary. Supervised surgical training on actual patients enables trainees to perform a large number of cataract surgeries over several weeks. Surgeries performed on actual patients fulfill a high demand for lens extraction, although the rate of complications is high, notably at the beginning of the course. Surgery quality is poorly assessed, which could compromise patient safety while trainees are on the steep learning curve [30, 32, 33].

EyeSi, HelpMeSee and other VRS devices

Although EyeSi and HMS virtual reality simulators have both demonstrated construct validity [15, 83, 84] and have encouraging results for improved safety [13], it remains difficult to compare them to each other. The simulators differ in their haptic systems, focus on different surgical procedures, and their use around the world.

Other, less widely used VRS devices also exist. The MicroVisTouch has a robotic arm with a handpiece to control the instrument used in the simulation. This simulator has a tactile feedback interface and can perform corneal incisions, capsulorhexis, and phacoemulsification. Its construct validity still needs to be confirmed by further studies [15]. The Phacovision (Melerit Medical, Linkoping, Sweden) is a 3D personal computer with a handpiece for phacoemulsification, a nucleus manipulator, foot pedals, and microscope [85]. Other devices for phacoemulsification include the Phantom phaco-simulator and the cataract surgery simulator [86]. Construct validity was shown for this type of virtual reality simulator, although skill transfer to the OR has not yet been studied [85]. The HMS simulator also proposes tactile feedback [87], corneal incision and suturing training, among other ophthalmological surgical techniques [88], which is not available in EyeSi. Both simulators offer vitreoretinal surgery training modules [89].

According to the results of this study, supervised surgical courses on actual patients are associated with a relatively high risk of complications, which raises the question of the acceptability of such training programs. Nevertheless, supervised surgical courses on actual patients are rarely reported in the literature and need further exploration in the domain of surgical training. It is reasonable to wonder if a VRS phase prior to surgery on actual patients, as proposed in the HMS training curriculum and in one EyeSi study reported here [24, 29], could help reduce complication rates. Access to virtual reality simulators in resource-limited areas is difficult. However, HMS already proposes a fee-for-service basis approach for its MSICS training curriculum with differing rates based on the region. For example, in LMIC in Sub-Saharan Africa, there is no cost to the trainee [6]. The novel phacoemulsification simulation-based training course offered by HMS might help bring phacoemulsification expertise in LMICs [54]. Also, costs of simulation-based training should be evaluated by considering the number of complications avoided. For example, the potential savings of decreasing the PCR rate after EyeSi simulation training would equal the price of 20 EyeSi simulators within 4 years [25]. Both the EyeSi and HMS simulators can play a significant role in massive cataract surgical training, although they will probably evolve in different geographic areas and with different goals.

Study limitations

This study was limited by the small number of articles retained from the study selection and its descriptive design. Only VRS and supervised surgery studies were retained as training methods. Other simulation devices (i.e., wet lab and dry lab) should be considered, notably in areas with no access to VRS. The participants were exclusively residents. It has been demonstrated that skill transfer only improves in surgeons with limited cataract surgery experience (less than 75 completed surgeries) [23]. Thus, VRS may be more important for novice surgeons [29, 90]. In this review, only 6 studies required limited phacoemulsification experience in participants [19, 20, 23, 24, 28, 29]. Other aspects of surgical training might increase patient safety, such as non-technical skills assessment [64]. These are rarely assessed and should perhaps be included in future research on this subject.

Conclusions

This review evaluated patient safety as the primary parameter for the evaluation of training programs’ efficacy. Intraoperative complication rate was the most frequently used parameter. VRS training appeared to be the safest method for efficient cataract surgery learning, superseding supervised surgical training on actual patients. However, virtual reality simulators are sparsely distributed around the world with numerous access difficulties and lack of standardization between training programs. Supervised surgical training on actual patients, on the other hand, is more readily available but is associated with a higher risk of surgical complications. The role of each different training program should be further explored and clearly defined for learners. Overall, when learning cataract surgery, several factors should be considered such as the type of surgical training method and its impact on patient safety. These factors must be considered along with the financial, cultural, geographical, and accessibility factors for the trainees. Assessment of the profitability of one training program considering trainees formation and the reduction of complications rate would be interesting to add to this research.

Acknowledgements

None.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, L.D. and T.B.; Methodology, L.D. and R.Y.; Software, L.D., AS.T.; Validation, T.B., VC.L. and AS.T.; Formal Analysis, BA.H., D.G.; Investigation, L.D and D.G.; Resources, BA.H., A.L.; Data Curation, N.C. and R.Y.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, L.D.; Writing – Review & Editing, VC.L., T.B., AS.T., A.L., N.C.; Visualization, N.C., BA.H., A.S.; Supervision, AS.T., T.B., A.S.; Project Administration, T.B.; Funding Acquisition, n/a.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Two of the authors of the manuscript (V.C. Lansingh and B.A. Henderson) are currently employed by HelpMeSee, Inc. (Jersey City, New York).

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Gower EW, Lindsley K, Tulenko SE, Nanji AA, Leyngold I, McDonnell PJ. Perioperative antibiotics for prevention of acute endophthalmitis after cataract surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;2:CD006364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Muttuvelu DV, Andersen CU. Cataract surgery education in member countries of the European Board of Ophthalmology. Can J Ophthalmol. 2016;51:207–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lansingh VC, Ravindran RD, Garg P, Fernandes M, Nair AG, Gogate PJ, et al. Embracing technology in cataract surgical training - the way forward. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2022;70:4079–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khan A, Rangu N, Thanitcul C, Riaz KM, Woreta FA. Ophthalmic Education: The Top 100 Cited Articles in Ophthalmology Journals. J Acad Ophthalmol (2017). 2023;15:e132–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Setting standards in medical training, Training simulators, Haag-Streit Group., 2023. https://haag-streit.com/en/Products/Categories/Simulators_training/Training_simulators#; consulted on 4th January 2024.

- 6.Broyles JR, Glick P, Hu J, Lim Y-W. Cataract blindness and Simulation-based training for Cataract surgeons: an Assessment of the HelpMeSee Approach. Rand Health Q. 2013;3:7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ní Dhubhghaill S, Sanogo M, Lefebvre F, Aclimandos W, Asoklis R, Atilla H, et al. Cataract surgical training in Europe: European Board of Ophthalmology survey. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2023;49:1120–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomsen AS, Subhi Y, Kiilgaard JF, la Cour M, Konge L. Update on simulation-based surgical training and assessment in ophthalmology: a systematic review. Ophthalmology. 2015;122:1111–30. e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oseni J, Adebayo A, Raval N, Moon JY, Juthani V, Chuck RS, et al. National Access to EyeSi Simulation: a comparative study among U.S. Ophthalmology Residency Programs. J Acad Ophthalmol. 2023;15:e112–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geary A, Wen Q, Adrianzén R, Congdon N, Janani R, Haddad D, et al. The impact of distance cataract surgical wet laboratory training on cataract surgical competency of ophthalmology residents. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21:219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeang LJ, Liechty JJ, Powell A, Schwartz C, DiSclafani M, Drucker MD et al. Rate of Posterior Capsule Rupture in Phacoemulsification Cataract Surgery by Residents with Institution of a Wet Laboratory Course. J Acad Ophthalmol (2017). 2022;14:e70–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Lee R, Raison N, Lau WY, Aydin A, Dasgupta P, Ahmed K, et al. A systematic review of simulation-based training tools for technical and non-technical skills in ophthalmology. Eye (Lond). 2020;34:1737–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin JC, Yu Z, Scott IU, Greenberg PB. Virtual reality training for cataract surgery operating performance in ophthalmology trainees. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;12:CD014953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirkpatrick D, Kirkpatrick J. Evaluating Training Programs. 3rd ed. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nayer ZH, Murdock B, Dharia IP, Belyea DA. Predictive and construct validity of virtual reality cataract surgery simulators. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2020;46:907–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peters M, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Munn Z, Trico A, Khalil H. Chapter 11: scoping reviews. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. JBI manual for evidence synthesis. JBI; 2020.

- 17.Daly MK, Gonzalez E, Siracuse-Lee D, Legutko PA. Efficacy of surgical simulator training versus traditional wet-lab training on operating room performance of ophthalmology residents during the capsulorhexis in cataract surgery. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2013;39:1734–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCannel CA, Reed DC, Goldman DR. Ophthalmic surgery Simulator Training improves Resident Performance of Capsulorhexis in the operating room. Ophthalmology. 2013;120:2456–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Staropoli PC, Gregori NZ, Junk AK, Galor A, Goldhardt R, Goldhagen BE, et al. Surgical Simulation Training reduces intraoperative cataract surgery complications among residents. Simul Healthc. 2018;13:11–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pokroy R, Du E, Alzaga A, Khodadadeh S, Steen D, Bachynski B, et al. Impact of simulator training on resident cataract surgery. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2013;251:777–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Belyea DA, Brown SE, Rajjoub LZ. Influence of surgery simulator training on ophthalmology resident phacoemulsification performance. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2011;37:1756–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thomsen ASS, Smith P, Subhi Y, Cour M, la, Tang L, Saleh GM, et al. High correlation between performance on a virtual-reality simulator and real-life cataract surgery. Acta Ophthalmol. 2017;95:307–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thomsen ASS, Bach-Holm D, Kjærbo H, Højgaard-Olsen K, Subhi Y, Saleh GM, et al. Operating room performance improves after proficiency-based virtual reality cataract surgery training. Ophthalmology. 2017;124:524–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baxter JM, Lee R, Sharp JAH, Foss AJE. Intensive cataract training: a novel approach. Eye. 2013;27:742–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ferris JD, Donachie PH, Johnston RL, Barnes B, Olaitan M, Sparrow JM. Royal College of Ophthalmologists’ National Ophthalmology Database study of cataract surgery: report 6. The impact of EyeSi virtual reality training on complications rates of cataract surgery performed by first and second year trainees. Br J Ophthalmol. 2020;104:324–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adnane I, Chahbi M, Elbelhadji M. Simulation virtuelle pour l’apprentissage de la chirurgie de cataracte. J Français d’Ophtalmologie. 2020;43:334–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ng DS-C, Sun Z, Young AL, Ko ST-C, Lok JK-H, Lai TY-Y, et al. Impact of virtual reality simulation on learning barriers of phacoemulsification perceived by residents. Clin Ophthalmol. 2018;12:885–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lucas L, Schellini SA, Lottelli AC. Complications in the first 10 phacoemulsification cataract surgeries with and without prior simulator training. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2019;82:289–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nair AG, Ahiwalay C, Bacchav AE, Sheth T, Lansingh VC, Vedula SS, et al. Effectiveness of simulation-based training for manual small incision cataract surgery among novice surgeons: a randomized controlled trial. Sci Rep. 2021;11:10945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang W, Ye R, Liu B, Chen Q, Huang G, Liu Y, et al. Visual outcomes of cataract surgery performed by supervised novice surgeons during training in rural China. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2013;41:463–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Farooqui JH, Mathur U, Pahwa RR, Singh A, Vasavada V, Chaudhary RM, et al. Training Indian ophthalmologists in phacoemulsification surgery: nine-year results of a unique two-week multicentric training program. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2021;69:1391–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ripa M, Sherif A. Cataract surgery training: report of a trainee’s experience. Oman J Ophthalmol. 2023;16:59–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lynds R, Hansen B, Blomquist PH, Mootha VV. Supervised resident manual small-incision cataract surgery outcomes at large urban United States residency training program. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2018;44:34–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jacobsen MF, Konge L, Bach-Holm D, la Cour M, Holm L, Højgaard-Olsen K, et al. Correlation of virtual reality performance with real-life cataract surgery performance. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2019;45:1246–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.HelpMeSee Simulation-basedT, Locations HMS. 2023. https://helpmesee.org/our-locations/. Accessed 23 Jan 2024.

- 36.Hosny SG, Johnston MJ, Pucher PH, Erridge S, Darzi A. Barriers to the implementation and uptake of simulation-based training programs in general surgery: a multinational qualitative study. J Surg Res. 2017;220:419–e4262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hind J, Edington M, Lockington D. Maximising cost-effectiveness and minimising waste in modern ocular surgical simulation. Eye (Lond). 2021;35:2335–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mishra D, Bhatia K, Verma L. Essentials of setting up a wet lab for ophthalmic surgical training in COVID-19 pandemic. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2021;69:410–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ezeanosike E, Azu-Okeke JC, Achigbu EO, Ezisi CN, Aniemeka DI, Ogbonnaya CE, et al. Cost-effective Ophthalmic Surgical Wetlab using the Porcine Orbit with a simple dissection protocol. OJOph. 2019;09:183–93. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bing EG, Parham GP, Cuevas A, Fisher B, Skinner J, Mwanahamuntu M, et al. Using low-cost virtual reality Simulation to Build Surgical Capacity for Cervical Cancer Treatment. J Glob Oncol. 2019;5:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Montrisuksirikun C, Trinavarat A, Atchaneeyasakul L-O. Effect of surgical simulation training on the complication rate of resident-performed phacoemulsification. BMJ Open Ophth. 2022;7:e000958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mamtora S, Jones R, Rabiolo A, Saleh GM, Ferris JD. Remote supervision for simulated cataract surgery. Eye (Lond). 2022;36:1333–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ng DS, Yip BHK, Young AL, Yip WWK, Lam NM, Li KK, et al. Cost-effectiveness of virtual reality and wet laboratory cataract surgery simulation. Med (Baltim). 2023;102:e35067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maubon L, Nderitu P, O’Brart DPS. Returning to cataract surgery after a hiatus: a UK survey report. Eye (Lond). 2022;36:1761–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lockington D, Saleh GM, Spencer AF, Ferris J. Cost and time resourcing for ophthalmic simulation in the UK: a Royal College of Ophthalmologists’ National Survey of regional Simulation leads in 2021. Eye (Lond). 2022;36:1973–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mondal S, Kelkar AS, Singh R, Jayadev C, Saravanan VR, Kelkar JA. What do retina fellows-in-training think about the vitreoretinal surgical simulator: a multicenter survey. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2023;71:3064–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Campbell S, Hind J, Lockington D. Engagement with ophthalmic simulation training has increased following COVID-19 disruption—the educational culture change required? Eye. 2021;35:2660–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gogate PM, Kulkarni SR, Krishnaiah S, Deshpande RD, Joshi SA, Palimkar A, et al. Safety and efficacy of phacoemulsification compared with manual small-incision cataract surgery by a randomized controlled clinical trial: six-week results. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:869–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Venkatesh R, Tan CSH, Sengupta S, Ravindran RD, Krishnan KT, Chang DF. Phacoemulsification versus manual small-incision cataract surgery for white cataract. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2010;36:1849–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dean WH, Murray NL, Buchan JC, Golnik K, Kim MJ, Burton MJ. Ophthalmic simulated Surgical Competency Assessment Rubric for manual small-incision cataract surgery. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2019;45:1252–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Riaz Y, De Silva SR, Evans JR. Manual small incision cataract surgery (MSICS) with posterior chamber intraocular lens versus phacoemulsification with posterior chamber intraocular lens for age-related cataract. Cochrane Database Syst Reviews. 2013. 10.1002/14651858.CD008813.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nair AG, Mishra D, Prabu A. Cataract surgical training among residents in India: results from a survey. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2023;71:743–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vision. 2020: the cataract challenge. Community Eye Health. 2000;13:17–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Phacoemulsification simulation-based training course (PSTC), HelpMeSee. 2023. https://helpmesee.org/pstc/. Accessed 25 Jan 2024.

- 55.Onal S, Gozum N, Gucukoglu A. Visual results and complications of posterior chamber intraocular lens implantation after capsular tear during phacoemulsification. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging. 2004;35:219–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cao H, Zhang L, Li L, Lo S. Risk factors for acute endophthalmitis following cataract surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e71731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gunalda J, Williams D, Koyfman A, Long B. High risk and low prevalence diseases: Endophthalmitis. Am J Emerg Med. 2023;71:144–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Qureshi MH, Steel DHW. Retinal detachment following cataract phacoemulsification-a review of the literature. Eye (Lond). 2020;34:616–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rothschild P, Richardson A, Beltz J, Chakrabarti R. Effect of virtual reality simulation training on real-life cataract surgery complications: systematic literature review. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2021;47:400–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mao RQ, Lan L, Kay J, Lohre R, Ayeni OR, Goel DP, et al. Immersive virtual reality for Surgical training: a systematic review. J Surg Res. 2021;268:40–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Filipe H, Di Luciano A, Clements J, Grau A, Skou Thomsen A, Lansingh V, et al. Good practices in simulation-based education in ophthalmology – a thematic series. An initiative of the Simulation Subcommittee of the Ophthalmology Foundation Part IV: recommendations for incorporating simulation-based education in ophthalmology training programs. Pan Am J Ophthalmol. 2023;5:38. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ti S-E, Yang Y-N, Lang SS, Chee SP. A 5-year audit of cataract surgery outcomes after posterior capsule rupture and risk factors affecting visual acuity. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014;157:180–e1851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liu B, Xu L, Wang YX, Jonas JB. Prevalence of cataract surgery and postoperative visual outcome in Greater Beijing: the Beijing Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:1322–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wood TC, Maqsood S, Nanavaty MA, Rajak S. Validity of scoring systems for the assessment of technical and non-technical skills in ophthalmic surgery-a systematic review. Eye (Lond). 2021;35:1833–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Selvander M, Asman P. Cataract surgeons outperform medical students in Eyesi virtual reality cataract surgery: evidence for construct validity. Acta Ophthalmol. 2013;91:469–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Selvander M, Åsman P. Virtual reality cataract surgery training: learning curves and concurrent validity. Acta Ophthalmol. 2012;90:412–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Selvander M, Asman P. Ready for OR or not? Human reader supplements Eyesi scoring in cataract surgical skills assessment. Clin Ophthalmol. 2013;7:1973–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Golnik C, Beaver H, Gauba V, Lee AG, Mayorga E, Palis G et al. Development of a new valid, reliable, and internationally applicable assessment tool of residents’ competence in ophthalmic surgery (an American Ophthalmological Society thesis). Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2013;111:24–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 69.Kim TS, O’Brien M, Zafar S, Hager GD, Sikder S, Vedula SS. Objective assessment of intraoperative technical skill in capsulorhexis using videos of cataract surgery. Int J Comput Assist Radiol Surg. 2019;14:1097–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Smith P, Tang L, Balntas V, Young K, Athanasiadis Y, Sullivan P, et al. PhacoTracking: an evolving paradigm in ophthalmic surgical training. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013;131:659–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dormegny L, Neumann N, Lejay A, Sauer A, Gaucher D, Proust F, et al. Multiple metrics assessment method for a reliable evaluation of corneal suturing skills. Sci Rep. 2023;13:2920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Baird BJ, Tynan MA, Tracy LF, Heaton JT, Burns JA. Surgeon positioning during Awake laryngeal surgery: an ergonomic analysis. Laryngoscope. 2021;131:2752–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mallard J, Hucteau E, Schott R, Trensz P, Pflumio C, Kalish-Weindling M, et al. Early skeletal muscle deconditioning and reduced exercise capacity during (neo)adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with breast cancer. Cancer. 2023;129:215–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bui AD, Sun Z, Wang Y, Huang S, Ryan M, Yu Y, et al. Factors impacting cumulative dissipated energy levels and postoperative visual acuity outcome in cataract surgery. BMC Ophthalmol. 2021;21:439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Anastasilakis K, Mourgela A, Symeonidis C, Dimitrakos SA, Ekonomidis P, Tsinopoulos I. Macular edema after uncomplicated cataract surgery: a role for phacoemulsification energy and vitreoretinal interface status? Eur J Ophthalmol. 2015;25:192–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cheng H, Clymer JW, Po-Han Chen B, Sadeghirad B, Ferko NC, Cameron CG, et al. Prolonged operative duration is associated with complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Surg Res. 2018;229:134–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Guidolin K, Spence RT, Azin A, Hirpara DH, Lam-Tin-Cheung K, Quereshy F, et al. The effect of operative duration on the outcome of colon cancer procedures. Surg Endosc. 2022;36:5076–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nagendran M, Gurusamy KS, Aggarwal R, Loizidou M, Davidson BR. Virtual reality training for surgical trainees in laparoscopic surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Reviews. 2013. 10.1002/14651858.CD006575.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lau KL, Scurrah R, Cocks H. Instrument for the evaluation of higher surgical training experience in the operating theatre. J Laryngol Otol. 2023;137:565–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Vermeulen J, Buyl R, D’haenens F, Swinnen E, Stas L, Gucciardo L, et al. Midwifery students’ satisfaction with perinatal simulation-based training. Women Birth. 2021;34:554–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wilde C, Memon S, Ah-Kye L, Milligan A, Pederson M, Timlin H. A Novel Simulation Model significantly improves confidence in Canthotomy and Cantholysis among Ophthalmology and Emergency Medicine trainees. J Emerg Med. 2023;65:e460–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mak ST, Lam CW, Ng DSC, Chong KKL, Yuen HKL. Oculoplastic surgical simulation using goat sockets. Orbit. 2022;41:292–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Nair AG, Ahiwalay C, Bacchav AE, Sheth T, Lansingh VC. Assessment of a high-fidelity, virtual reality-based, manual small-incision cataract surgery simulator: a face and content validity study. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2022;70:4010–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Forslund Jacobsen M, Konge L, la Cour M, Holm L, Kjaerbo H, Moldow B, et al. Simulation of advanced cataract surgery - validation of a newly developed test. Acta Ophthalmol. 2020;98:687–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lam CK, Sundaraj K, Sulaiman MN. A systematic review of phacoemulsification cataract surgery in virtual reality simulators. Med (Kaunas). 2013;49:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lam CK, Sundaraj K, Sulaiman MN, Qamarruddin FA. Virtual phacoemulsification surgical simulation using visual guidance and performance parameters as a feasible proficiency assessment tool. BMC Ophthalmol. 2016;16:88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sankarananthan R, Prasad RS, Koshy TA, Dharani P, Bacchav A, Lansingh VC, et al. An objective evaluation of simulated surgical outcomes among surgical trainees using manual small-incision cataract surgery virtual reality simulator. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2022;70:4018–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.HelpMeSee suturing course. 2023. https://helpmesee.org/suturing/. Accessed 23 Jan 2024.

- 89.Deuchler S, Wagner C, Singh P, Müller M, Al-Dwairi R, Benjilali R, et al. Clinical efficacy of simulated vitreoretinal surgery to prepare surgeons for the Upcoming intervention in the operating room. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0150690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.la Cour M, Thomsen ASS, Alberti M, Konge L. Simulators in the training of surgeons: is it worth the investment in money and time? 2018 Jules Gonin lecture of the Retina Research Foundation. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2019;257:877–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.