SUMMARY BOX.

Over a year has passed since large-scale armed conflict erupted in Sudan in April 2023, plunging the country into full-scale war and a severe humanitarian, infrastructure and healthcare crisis.

Sudan faces the worst conflict-induced humanitarian crisis globally, with the world’s largest internal displacement crisis, acute hunger and the looming threat of famine.

The war has devastated Sudan’s healthcare infrastructure, leading to closures and disruptions in medical services, particularly in war-affected areas.

The war is pushing the country into an emerging health crisis, with transitioning from a double to a quadruple burden of diseases, including communicable diseases, non-communicable diseases, physical injuries and trauma.

There is an urgent need for coordinated action, informed by lessons from past conflicts, that strengthens local partnerships, enhances coordination among local, bilateral and multilateral actors, and supports community-driven initiatives to address the escalating crisis in Sudan.

Introduction

Contextual background

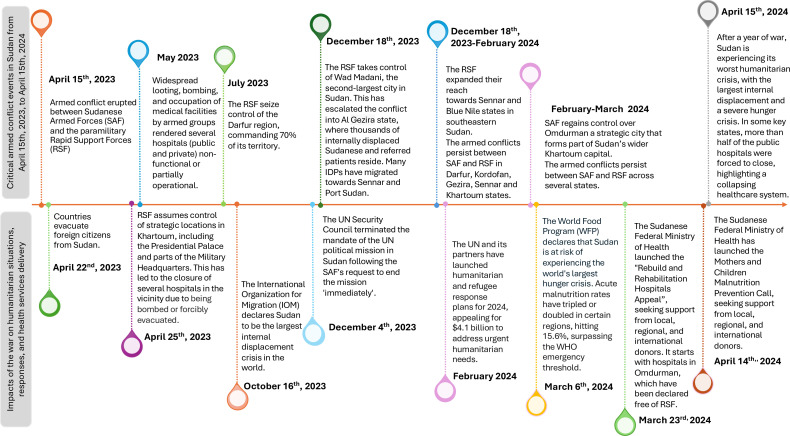

A year following the eruption of large-scale armed conflict on 15 April 2023, between the Sudanese Armed Forces and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces, the country’s humanitarian, infrastructure and healthcare systems have been plunged into a grim crisis. The shifting territorial control dynamics between the two warring factions are making political outcomes increasingly unpredictable and further deteriorating the humanitarian conditions (figure 1). Sudan is currently home to the worst humanitarian crisis globally, in terms of mass displacement and acute hunger.1 Both the nation’s infrastructure and healthcare systems were significantly affected.2

Figure 1. Timeline of critical armed conflict events in Sudan from 15 April 2023 to 15 April 2024, and their impact on humanitarian situations, responses and health services.

This commentary highlights Sudan’s severe health and humanitarian crisis, precipitated by the ongoing conflict. We assess the conflict’s impact on the health system and potential risks to the country’s health profile. We share stories of resilience from across the conflict-affected nation and emphasise the critical need for urgent investment and local partnerships with bilateral and multilateral actors to address the crisis and restore the health system.

Humanitarian crisis intensification

As of February 2024, Sudan has 6.8 million internally displaced persons (IDPs), originating from 12 out of the country’s 18 states, with 19% living in informal settlements, marking it the world’s largest internal displacement crisis, surpassing that of Syria.3 Additionally, 1.5 million persons have been displaced outside the country, and 24.8 million people, nearly half of the country’s population, require humanitarian aid and protection.1 3 Moreover, Sudan faces acute hunger, with 18 million people acutely food insecure, including four million children under the age of 5 suffering from malnutrition.4 The situation is currently classified on the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) scale as crises (IPC3) or indicating emergency (IPC4 indicating), with projections indicating a potential imminent escalation to famine level (IPC5).5 The humanitarian situation is expected to worsen due to the failure to de-escalate the conflict between the armed factions and a rise in organised violence.1 Consequently, the United Nations (UN) has labelled this war as a ‘forgotten war’ and ‘one of the worst humanitarian nightmares in recent history’.6 Reports detail the extreme challenges confronting both IDPs and residents trapped in their homes. To combat severe hunger, many have adopted desperate measures, including consuming mud and peanut shells, or boiling grass and leaves with spices—a stark testament to the crisis’s severity.7 8 Garang Achien Akok, a displaced individual from the Al Lait refugee camp in North Darfur, describes his family’s struggle for survival: ‘Sometimes we don’t eat for days,’ he shared, describing the extreme agony and helplessness as he watched his wife and children dig for soil, roll it into balls and swallow it with water to stave off hunger. ‘I keep telling them not to do it, but it’s hunger. There is nothing I can do’.7 A health official poignantly notes, ‘The conflict has turned Sudan’s breadbasket into battlefields. Hundreds of thousands of children who have managed to dodge bullets and bombs are now facing death by starvation and disease’.9 Displacement is perilous, with many risking their lives searching for refuge. Individuals often find themselves caught in violent crossfires, subjected to ruthless looting, or enduring gruelling escapes from conflict zones. Tragically, numerous individuals fleeing to Egypt have perished from severe heatwaves and dehydration, with entire families lost in the desert.10

Impact on healthcare system

Pre-war Sudan’s health system, encompassing the WHO health system ‘building blocks’ framework—service delivery, financing, health workforce, medical supplies, health information systems and governance—faced several challenges.11 It was underfunded, fragmented and characterised by critical shortages in the health workforce, as well as significant disparities in access, quality and affordability of care.11 An overwhelming 95.94% of the population had to pay out-of-pocket for healthcare services.12 Additionally, the country faced critical shortages in its health workforce; in 2019, the density of physicians, nurses, midwives and other health workers stood at only 3.6, 14 and 9.1 per 10 000 people, respectively, far below the WHO minimum threshold density of 22.8 health professionals.11 Nonetheless, the country was slowly progressing to meet the Sustainable Development Goals.13 The current war has further deteriorated the health system and ushered in new challenges most notably in the service delivery and health workforce. The health infrastructure has been significantly impacted, with the WHO reporting that 70% of public and private healthcare facilities in war-affected states were forced to close by the end of 2023.14 Data from the Sudan Federal Ministry of Health (FMOH) indicates that over 30% of the public hospitals are no longer in service within a year of the war starting (table 1). Khartoum State, the epicentre of the conflict, suffered the greatest impact on its health system. As the armed conflict erupted, thousands of inhabitants and patients from Khartoum State sought refuge in Gezira State, located approximately 200 km southeast of Khartoum drawn by its relatively available medical infrastructure and proximity. However, by the end of 2023, the fighting had spread into Gezira State, jeopardising not only its residents but also the IDPs and patients who had fled there for safety. Similar to Khartoum State, where 58.5% of public hospitals were forced to close, the conflict’s expansion into Gezira State led to repeated attacks and looting of medical facilities. Consequently, several hospitals in Gezira State (56.2% of public hospitals) were either shut down or forced to reduce services, worsening conditions for existing IDPs (table 1). Other conflict-affected regions are situated in the southern and western parts of the country, particularly in Darfur and Kordofan. In these regions, the operational capacities of hospitals in some states have been affected to varying degrees. Central Darfur has borne the brunt of the impact, with around 40% of its public hospitals forced to close, experiencing severe disruptions in the provision of medical services. Meanwhile, North Darfur, White Nile and North Kordofan have faced comparatively moderate challenges, with 33%, 26.8% and 16.2% of their public hospitals forced to close, respectively (table 1). In these conflict-affected states, medical facilities are forced to close due to a confluence of factors: ongoing insecurity, destruction and looting of medical facilities, a critical shortage of healthcare workers, and challenges in procuring essential supplies.2 15 For instance, in regions affected by war where ambulances have been looted, residents have resorted to using donkey carts and wheelbarrows as makeshift ambulances to transport patients.16 A donkey cart driver from Tamboul, Gezira State shares, ‘I transported a pregnant woman in labour in my cart from a village 15 kilometres away from here.’ This, along with many other stories, highlights the resilience of residents in coping with the healthcare crisis.16 In Sudan’s conflict zones, healthcare workers confront severe challenges that far exceed their regular duties. Unpaid for months,17 18 targeted with violence and facing critical staff shortages,12 they are hindered in their efforts to provide essential care, reflecting a profound human cost beyond mere statistics. For instance, a nurse at Port Sudan Teaching Hospital highlighted the desperation for any remuneration: ‘We just need something small to keep going.’18 A doctor from Gezira State described his reality: ‘I'm struggling to make ends meet and am torn between fleeing for my safety and staying to help those in need.’ These experiences are not isolated; many healthcare workers are leaving the country in search of stability.17 Furthermore, the war has exacerbated the affordability of healthcare services, which were already heavily reliant on out-of-pocket payments. The conflict has intensified this financial burden through looting and increased poverty.19 The country’s health information systems have been severely compromised due to the deliberate targeting of telecommunications and health information systems, along with violence against healthcare workers. These targeted disruptions have made data collection and communication exceedingly difficult, impeding the gathering of crucial baseline health system data.15 20

Table 1. Number of operating public hospitals and reduction percentage (%) in 18 states of Sudan from 15 April 2023 to 15 April 2024.

| Sudan states (n=18 states) | Number of public hospitals operating in Sudan before 15 April 2023 (before the war) | Number of public hospitals operating in Sudan from 15 April 2023* to 18 December 2023† | Change status | Reduction (%) in operating public hospitals since the start of the war compared with before the war | Number of public hospitals operating in Sudan after 18 December 2023† | Change status | Reduction (%) in operating public hospitals after 18 December 2023, compared with before the war |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blue Nile | 18 | 18 |

|

0.0% | 18 |

|

0.0% |

| White Nile | 41 | 41 |

|

0.0% | 30 |

|

26.80% |

| Sennar | 37 | 37 |

|

0.0% | 37 |

|

0.0% |

| South Kordofan Kordofan | 14 | 13 |

|

7.10% | 13 |

|

7.10% |

| West Kordofan | 20 | 20 |

|

0.0% | 19 |

|

5% |

| North Kordofan | 37 | 31 |

|

16.20% | 31 |

|

16.20% |

| South Darfur | 21 | 19 |

|

9.50% | 19 |

|

9.50% |

| North Darfur | 24 | 16 |

|

33.3 | 16 |

|

33.3 |

| West Darfur | 10 | 10 |

|

0.0% | 10 |

|

0.0% |

| East Darfur | 5 | 5 |

|

0.0% | 5 |

|

0.0% |

| Central Darfur | 10 | 10 |

|

0.0% | 6 |

|

40% |

| Gezira | 89 | 89 |

|

0.0% | 39 |

|

56.20% |

| Nile River | 42 | 42 |

|

0.0% | 42 |

|

19% |

| Northern State | 34 | 34 |

|

0.0% | 34 |

|

0.0% |

| Al Qadarif | 30 | 30 |

|

0.0% | 30 |

|

0.0% |

| Kassala | 29 | 27 |

|

6.90% | 27 |

|

6.90% |

| Khartoum | 53 | 22 |

|

58.50% | 22 |

|

58.50% |

| Red Sea | 26 | 26 |

|

0.0% | 26 |

|

0.0% |

| Total‡ | 540 | 480 |

|

11.10% | 377 |

|

30.20% |

The cells marked with a green dot indicate states with no change in the numbers of operating public hospitals. Cells marked with yellow dots indicate states with <10% reduction; orange dots indicate a reduction of 10%–40%; red dots indicate a reduction of >40% in the numbers of operating public hospitals, respectively.

15 April 2023 marks the start of the war, beginning in Khartoum State, where the capital Khartoum is located.

18 December 2023 marks the date the Rapid Support Forces seized control of Wad Madani, Sudan’s second largest and a strategic city, located in Gezira State, where thousands of internally displaced Sudanese and referred patients sought refuge following the outbreak of war.

Table data is provided by the Sudan Federal Ministry of Health which only pertains to public hospitals. Private hospitals are not included in the data.

Impact of the war on the country’s health profile: the emerging quadruple burden of diseases

Health profile pre-war and new challenges

Prior to the war, the country’s health profile was characterised by a double burden of diseases—predominantly communicable diseases, marked by recurrent outbreaks and non-communicable diseases (NCDs).11 The war has not only further deteriorated Sudan’s compromised health profile but has also brought about new health challenges, such as conflict-related physical injuries and trauma.20 21 This signals a grave transition from a double burden of diseases to a quadruple burden—comprising communicable diseases, NCDs, physical injuries and trauma—further exacerbating the health crisis. The surge in IDPs and the collapse of environmental sanitation have significantly worsened the burden of communicable diseases.22 This worsening situation is evidenced by outbreaks of cholera, measles, dengue fever, chikungunya22 and even the rise in cases of rabies in war-ravaged areas.23 Furthermore, the war is anticipated to increase the vulnerability of individuals living with NCDs and increase the susceptibility of many others to them. Factors exacerbating this include displacement and instability, which result in limited access to medical services for screening and follow-up, challenges in obtaining chronic disease medications, interruptions in treatment and difficulties in adequately storing medications such as insulin due to power outages. A rise in war-related fatalities and physical injuries has been documented. While precise figures are challenging to obtain, the United Nations has referenced data from the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project, reporting 14 790 conflict-related fatalities.21 However, independent reports indicate even higher casualties, with experts suggesting 10 000–15 000 fatalities in a city-wide massacre in the West Darfur capital of El Geneina alone, indicating that the numbers reported by the UN are grossly underestimating the fatalities.24 The exact number of non-fatal injuries remains unclear due to difficulties in tracking numbers caused by displacement and a fragile health informatics infrastructure. Furthermore, the war is set to worsen the burden of war-related trauma, intensifying psychological effects from exposure to traumatic events, violence, war-related stressors like displacement, and the increase in gender-based violence (GBV).20 The transition from a double burden of disease to a quadruple burden of diseases will occasion health services demand exceeding the capacity of the country’s healthcare system. This will reverse the progress made in strengthening the healthcare system11 13 and disrupt the FMOH efforts to address health needs amidst the conflict.25

Addressing the quadruple burden of disease during the war

To effectively address health challenges during wartime, strategies must encompass the inherent fragility of health systems and the exacerbating humanitarian crisis. These strategies should leverage the robust resources of the WHO and draw on historical insights. Key strategies include:

A. Integration of WHO frameworks and tools

Leveraging the WHO’s robust array of frameworks,26 guidance27 and technical resources28 such as the Health Systems Resilience Toolkit,29 bridging the conceptual frameworks and their operationalisation. This toolkit encapsulates a broad spectrum of strategies, designed to enhance health systems’ capacity to forecast, prevent, detect, absorb, adapt and respond to diverse risks and shock events, including those arising from wars and severe health events. It goes beyond managing the acute phase of crisis response to facilitate the long-term recovery and rebuilding of health infrastructure.29

B. learning from global experiences

Drawing on global precedents from conflict-affected and resource-stretched contexts, adopting proven strategies that have successfully managed diverse disease burdens during conflicts and humanitarian crises is crucial. This approach is supported by empirical evidence from Lebanon,30 Syria31 and Ethiopia’s32 adaptive health responses, all of which demonstrate the effectiveness of governance-centred, capacity-oriented and community-driven approaches.30 Additionally, insights from South Africa’s management of its quadruple disease burden underscore the importance of strategies that ensure sustainable access to care and employ an integrated, whole-system approach (a multisectoral and multidisciplinary approach) to address health challenges comprehensively.33

Importance of local investments in health systems

Despite the ongoing challenges, several initiatives have been essential in sustaining healthcare services and mitigating humanitarian crises. Community-led efforts, notably local charity kitchens (soup kitchens) providing free meals to individuals trapped in conflict zones, have attracted substantial support from the Sudanese diaspora, highlighting the essential role of community engagement in alleviating suffering.34 Other initiatives such as ‘Rebuild and Rehabilitation Hospitals Appeal’ and the ‘Mothers and Children Malnutrition Prevention Call,’ launched by the FMOH (figure 1) and have called for support from local, regional and international donors. These initiatives have garnered substantial community involvement, drawing significant contributions from civil society organisations, professional associations such as the Sudanese American Physicians Association (SAPA), and the Sudanese Doctors Association in Qatar. SAPA has notably rehabilitated three hospitals, including providing operational funding for the rehabilitation of Saudi Hospital in Omdurman, Khartoum State, one of only two in the region offering maternity care. Furthermore, SAPA established a hospital in Medani, Gezeira State, a facility with 80 beds, including six specialised intensive care unit beds, dedicated to providing free medical care to IDPs, focusing on children and women severely impacted by the ongoing war.35 The Sudanese Doctors Association in Qatar has also made substantial contributions by upgrading the Port Sudan Teaching Hospital and initiating telemedicine services to meet urgent healthcare needs at the onset of the conflict.36 Other initiatives, such as community-driven pharmaceutical distribution networks, have been facilitated by ‘Wafra,’ a social media group that shares updates on drug availability and directs citizens to purchase locations.37 A successful collaboration between WHO and health ministries from eight states has significantly improved primary healthcare access via mobile clinics, serving underserved areas.38 Strategically located near IDP sites, these clinics operate out of schools, closed health facilities, or even under trees, and have served 48 900 patients since launching. These units provide a comprehensive range of services free of charge, including treatments, follow-up care, minor surgeries, chronic disease management, and maternal and child health services like vaccinations and antenatal care. Additionally, they function as sentinel sites for disease surveillance, offer support for GBV survivors and mental health services, and facilitate referrals to specialised centres.38 These efforts, along with many others,39 40 not only showcase remarkable resilience but also underscore the critical importance of investing in local health systems. Expanding and supporting community-led health programmes, combined with fostering coordinated collaboration, can create a significant cascading effect in strengthening the country’s health system.

Call to action

Despite the national efforts, the healthcare system in Sudan during wartime continues to face significant challenges.25 These include difficulties in implementation and coordination, a fragile health information infrastructure, constraints due to limited, unstable and stretched resources, and shortages of healthcare workers.25 Furthermore, the humanitarian crisis in Sudan is severely underfunded, with donor pledges falling alarmingly short of what is required. Only 5% of the UN’s aid appeal for Sudan is funded, leaving a staggering $2.56 billion gap.41

Immediate support and specific steps:

1- Investment in healthcare despite conflict

The international and global community must prioritise investments in Sudan’s health system during this war. Such investments not only yield substantial benefits during the conflict but also serve as a promising and sustainable development strategy for countries transitioning out of conflict.42 Experiences from South Sudan have demonstrated that proactive investments during conflict can significantly enhance service coverage.43

2- Breaking down silos: local, bilateral, and multilateral collaboration

Collaboration among local stakeholders—government, civil society and non-governmental organisations—is crucial for effectively coordinating resources and aligning health strategies in Sudan. This critical collaboration fosters aid localisation, optimises resource use and ensures the development of a cohesive response agreed on by all stakeholders toward a unified goal.25

3- Community-driven approaches

We call on recognising the importance of bottom-up approaches and supporting initiatives that channel funds directly to communities, enhancing local capacities through participatory methods. This empowers communities and strengthens the bonds between them, civil society groups, and governmental bodies, ensuring a cohesive effort in healthcare provision. Community involvement is essential to ensure interventions are culturally relevant, widely accepted and sustainable.30

4- Scaled-up, localized and direct aid

Deliver direct financial and material support to address immediate healthcare needs and shortages.39 Aid must be scaled up significantly to meet the vast needs on the ground, ensuring that assistance is both adequate and effectively targeted.41

5- Capacity building and technology transfer

To foster self-sustaining, nationally owned and resilient processes,42 we call on the global health community to invest in on building local healthcare capacity through training, resource allocation and infrastructure development.42 Facilitate the transfer of medical technology and expertise to modernise Sudan’s healthcare facilities and systems.44

This call to action is not just a plea but a mandate to prioritise and sustain efforts that will strengthen Sudan’s healthcare system.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the conflict in Sudan has occasioned a grim humanitarian and health crisis. The mass displacement, acute hunger and the psychological and physical impacts of the war, along with the disruption of health service delivery due to hospital closures, underscore the urgent need for a robust international response. Despite these grave circumstances, the resilience and ingenuity demonstrated by Sudanese health workers and communities are commendable. Historical precedents indicate that strengthening health systems during periods of conflict is feasible, as evidenced by similar experiences in other regions. The global health community must collaborate closely with local partners to address the challenges posed by the ongoing war. The focus should be on strengthening local capacities to address the current crisis and build resilience and preparedness for the emerging quadruple disease burden. A renewed commitment is urgently needed—one that addresses the humanitarian crisis, mobilises resources and partners with local efforts to rebuild and restore the healthcare system. Investment in Sudan’s health system should not be contingent on a ceasefire because investing now is a more prudent decision than waiting until the situation deteriorates further. The global health community must not allow Sudan to become a ‘forgotten war’—this narrative must be averted, starting with the restoration of its health system.

Footnotes

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Handling editor: Fi Godlee

Patient consent for publication: Not applicable.

Ethics approval: Not applicable.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon request.

References

- 1.United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) Sudan situation report. 2024

- 2.Hashim A, Ahmed W, Elleithi A. A glimpse of light for Sudan’s pressured health system amid military coup violations. The Lancet. 2023;401:1493–4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00718-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.International Organization for Migration (IOM) Displacement tracking matrix | DTM sudan sudan’s internally displaced persons 2023 estimates. 2024

- 4.Integrated food security phase classification IPC Sudan: acute food insecurity projection update for october 2023-february 2024. 2024. https://www.ipcinfo.org/ipc-country-analysis/details-map/en/c/1156730/?iso3=SDN Available.

- 5.United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) Famine prevention plan Sudan. 2024

- 6.United Nations UN relief chief urges end to ‘humanitarian nightmare’ in Sudan. 2023

- 7.Michael M. OMDURMAN,Sudan; 2024. Reuters Special Report: Starving in Sudan. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Louis Mian SB, Formanek I, Roth R. People eating ‘grass and peanut shells’ in darfur, as hunger crisis engulfs war-ravaged Sudan. 2024. https://www.cnn.com/2024/05/03/africa/people-eating-grass-sudan-hunger/index.html Available.

- 9.Save the Children Child hunger in Sudan almost doubles in six months with three in every four children affected. 2024

- 10.Broadcast D. Heatwave kills dozens of sudanese en route to egypt. 2024. https://www.dabangasudan.org/en/all-news/article/heatwave-kills-dozens-of-sudanese-en-route-to-egypt Available.

- 11.Hassanain SA, Eltahir A, Freedom ELI. Peace, and justice: a new paradigm for the Sudanese health system after Sudan’s 2019 uprising. Economic Research Forum (ERF); 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ebaidalla EM, Ali MEM. Determinants and impact of household’s out-of-pocket healthcare expenditure in Sudan: evidence from urban and rural population. Mid East Dev J. 2019;11:181–98. doi: 10.1080/17938120.2019.1668163. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wharton G, Ali OE, Khalil S, et al. Rebuilding Sudan’s health system: opportunities and challenges. The Lancet. 2020;395:171–3. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32974-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization (WHO) Sudan health emergency: situation report no. 4. 2023:4.

- 15.Badri R, Dawood I. The implications of the Sudan war on healthcare workers and facilities: a health system tragedy. Confl Health. 2024;18:22. doi: 10.1186/s13031-024-00581-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Asharq Al-Awsat . Asharq Al Awsat; 2024. In sudan, donkey carts replace ambulances. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Siddig EA. The impact of sudan’s armed conflict on the fiscal situation and service delivery. 2023

- 18.Far from fighting, doctor strikes aggravate healthcare collapse in port sudan. 2023. https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/far-fighting-doctor-strikes-aggravate-healthcare-collapse-port-sudan-2023-08-27/ Available.

- 19.United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights Situation of human rights in the sudan: report of the united nations high commissioner for human rights. 2024

- 20.International Rescue Committee Sudan crisis report: one year of conflict executive summary. 2024

- 21.Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED) SudanSituation update: escalating conflict in khartoum and attacks on civilians in al-jazirah and south kordofan. 2024

- 22.Aljaily SM, Hamed IAY, Mustafa KS, et al. Challenges and epidemiological implications of the first outbreak of dengue and chikungunya in Sudan. East Mediterr Health J. 2024;30:53–9. doi: 10.26719/emhj.24.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dabanga R. Measles spreading in sudan, rabies in south kordofan. 2024

- 24.Brachet E. Le Monde; 2024. What has happened is genocide’: massacres in the Sudanese city of el Geneina. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Awadalla HMI. How public health officials keep hope alive in sudan’s civil war. 2024. https://harvardpublichealth.org/global-health/as-sudan-civil-war-raged-its-health-ministry-kept-hope-alive Available.

- 26.Reduction UOfDR Sendai framework for disaster risk reduction 2015–2030. 2015

- 27.Organization WH Implementation guide for health systems recovery in emergencies: transforming challenges into opportunities. 2020

- 28.Organization WH Quality of care in fragile, conflict-affected and vulnerable settings: taking action. 2020 doi: 10.2471/BLT.19.246280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Organization WH Health systems resilience toolkit: a who global public health good to support building and strengthening of sustainable health systems resilience in countries with various contexts. 2022

- 30.Truppa C, Yaacoub S, Valente M, et al. Health systems resilience in fragile and conflict-affected settings: a systematic scoping review. Confl Health. 2024;18:2. doi: 10.1186/s13031-023-00560-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jamal Z, Alameddine M, Diaconu K, et al. Health system resilience in the face of crisis: analysing the challenges, strategies and capacities for UNRWA in Syria. Health Policy Plan. 2020;35:26–35. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czz129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gesesew H, Berhane K, Siraj ES, et al. The impact of war on the health system of the Tigray region in Ethiopia: an assessment. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6:e007328. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-007328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Amuyunzu-Nyamongo M. Noncommunicable diseases, injuries, and mental health: the triple burden in Africa. Pan Afr Med J. 2022;43:167. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2022.43.167.38392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Broadcats D. Charity kitchens in sudan capital resume activities ‘thanks to huge efforts of volunteers. 2024. https://www.dabangasudan.org/en/all-news/article/soup-kitchens-in-sudan-capital-resume-activities-thanks-to-huge-efforts-of-volunteers Available.

- 35.Sudanese American Physicians Association (SAPA) SAPA healthcare & emergency services projects. 2024. https://sapa-usa.org/ Available.

- 36.The Guardian Sudan’s doctors turn to social media as health infrastructure crumbles. 2023. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2023/may/10/sudans-doctors-turn-to-social-media-as-health-infrastructure-crumbles Available.

- 37.Hemmeda L, Tiwari A, Kolawole BO, et al. The critical pharmaceutical situation in Sudan 2023: A humanitarian catastrophe of civil war. Int J Equity Health. 2024;23:54. doi: 10.1186/s12939-024-02103-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.World Health Organization WHO-supported mobile clinics help improve access to primary health care in sudan. 2023. https://www.emro.who.int/sdn/sudan-news/who-supported-mobile-clinics-help-improve-access-to-primary-health-care-in-sudan.html Available.

- 39.The Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) From feasible to life-saving: the urgent case for cash at scale in. 2024

- 40.UNICEF Sudan Japan and unicef sudan join hands to ensure mothers and children in sudan have access to quality maternal and newborn health care services. 2024

- 41.The International Rescue Committee (IRC) IRC warns unfettered humanitarian access and scale-up of funding needed to avert catastrophic hunger crisis in sudan. 2024

- 42.Kruk ME, Freedman LP, Anglin GA, et al. Rebuilding health systems to improve health and promote statebuilding in post-conflict countries: A theoretical framework and research agenda. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70:89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Valadez JJ, Berendes S, Odhiambo J, et al. Is development aid to strengthen health systems during protracted conflict a useful investment? The case of South Sudan, 2011-2015. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5:e002093. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-002093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bowsher G, El Achi N, Augustin K, et al. eHealth for service delivery in conflict: a narrative review of the application of eHealth technologies in contemporary conflict settings. Health Policy Plan. 2021;36:974–81. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czab042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request.