Key Points

-

•

Germ line ERG LOF variants predispose to cytopenias and HMs.

-

•

Somatic genetic rescue of ERG pathogenic variants in hematopoietic tissues impacts diagnosis, disease severity, and potential for correction.

Visual Abstract

Abstract

The genomics era has facilitated the discovery of new genes that predispose individuals to bone marrow failure (BMF) and hematological malignancy (HM). We report the discovery of ETS-related gene (ERG), a novel, autosomal dominant BMF/HM predisposition gene. ERG is a highly constrained transcription factor that is critical for definitive hematopoiesis, stem cell function, and platelet maintenance. ERG colocalizes with other transcription factors, including RUNX family transcription factor 1 (RUNX1) and GATA binding protein 2 (GATA2), on promoters or enhancers of genes that orchestrate hematopoiesis. We identified a rare heterozygous ERG missense variant in 3 individuals with thrombocytopenia from 1 family and 14 additional ERG variants in unrelated individuals with BMF/HM, including 2 de novo cases and 3 truncating variants. Phenotypes associated with pathogenic germ line ERG variants included cytopenias (thrombocytopenia, neutropenia, and pancytopenia) and HMs (acute myeloid leukemia, myelodysplastic syndrome, and acute lymphoblastic leukemia) with onset before 40 years. Twenty ERG variants (19 missense and 1 truncating), including 3 missense population variants, were functionally characterized. Thirteen potentially pathogenic erythroblast transformation specific (ETS) domain missense variants displayed loss-of-function (LOF) characteristics, thereby disrupting transcriptional transactivation, DNA binding, and/or nuclear localization. Selected variants overexpressed in mouse fetal liver cells failed to drive myeloid differentiation and cytokine-independent growth in culture and to promote acute erythroleukemia when transplanted into mice, concordant with these being LOF variants. Four individuals displayed somatic genetic rescue by copy neutral loss of heterozygosity. Identification of predisposing germ line ERG variants has clinical implications for patient and family diagnoses, counseling, surveillance, and treatment strategies, including selection of bone marrow donors and cell or gene therapy.

In this Plenary Paper, Zerella and colleagues describe a novel bone marrow failure syndrome associated with a tendency to hematological malignancy (HM), reflecting a germ line haploinsufficiency of ETS-related gene (ERG). ERG is a transcription factor that is known to be critical for hematopoiesis. Initially identified in 3 family members with inherited thrombocytopenia, a large international collaboration yielded 14 other unrelated individuals with diverse ERG mutations. The pathophysiology underlying the surprising finding that the patients were also predisposed to HM remains to be further delineated.

Introduction

Tightly controlled regulation of hematopoiesis is essential to ensure adequate supply of healthy blood cells and the ability to respond to increased demand. Transcription factors (TFs), including ETS-related gene (ERG), TAL bHLH transcription factor 1, erythroid differentiation factor (TAL1), LYL1 basic helix-loop-helix family member (LYL1), LIM domain only 2 (LMO2), GATA binding protein 2 (GATA2), RUNX family transcription factor 1 (RUNX1), Meis homeobox 1 (MEIS1), Spi-1 proto-oncogene (SPI1/PU.1), Fli-1 proto-oncogene, ETS transcription factor (FLI1), and growth factor independent 1B transcriptional repressor (GFI1B), form part of a network that, in varying combinations, control the regulation of hematopoietic stem or progenitor cells.1,2 This TF network is important for regulating cellular self-renewal, lineage specification, differentiation, and migration. Dysregulation can lead to cellular malfunction, impaired differentiation programs, and aberrant stem cell self-renewal, all of which have implications for human disease. Highlighting this, recurrent somatic variants within several of these TFs, including chromosomal rearrangements, point mutations, and insertions and deletions, are detected in hematological malignancies (HM). Furthermore, germ line pathogenic variants in RUNX1 (familial platelet disorder with predisposition to myeloid malignancies, RUNX1-FPD; Monarch Disease Ontology [MonDO]: 0011071), GATA2 (GATA2 deficiency with susceptibility to myelodysplastic syndrome [MDS]/acute myeloid leukemia [AML]; MonDO: 0042982), and FLI1 (bleeding disorder, platelet-type, 21; Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man: 617443) are associated with the development of hematological disorders typified by an increased risk for cytopenias and/or HMs. The roles of other members of this key hematopoietic TF network in predisposing to HMs remain to be identified.3

ERG, a member of the ETS TF family, was first reported to be critical for normal hematopoiesis in 2008.4 Like most ETS TFs, ERG demonstrates various homeostatic functions by binding to specific GGA(A/T) motifs to regulate genes in hematopoietic and nonhematopoietic contexts. This includes binding at gene regulatory sites with other key hematopoietic transcriptional regulators, including with products of the HM predisposition genes GATA2 and RUNX1.5 In normal hematopoiesis, ERG is essential for maintaining quiescence and preventing differentiation of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs),6 thereby promoting HSC self-renewal after hematopoietic stress (eg, bone marrow [BM] transplantation)7 and supporting definitive hematopoiesis, adult HSC function, and the maintenance of peripheral blood (PB) platelet numbers.4

The perturbation of hematopoiesis by aberrant ERG expression and the contribution of ERG overexpression to HMs have been well documented,8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 particularly in AML.19, 20, 21, 22 The consequences of dysregulated ERG are also evident in other diseases, including cardiovascular disease,23, 24, 25, 26 prostate cancers,27,28 Ewing's sarcoma,29 and B-cell acute lymphoid leukemia (B-ALL),30 the latter 3 via chromosomal translocations and genomic rearrangements. The first report of disease owing to a germ line ERG variant was heterozygous Erg (S322P) that causes thrombocytopenia in a mouse model.4 More recently, germ line loss-of-function (LOF) ERG variants have been associated with a predisposition to primary lymphedema.31

To our knowledge, we report for the first time germ line ERG variants in patients with a range of malignant and nonmalignant hematological phenotypes. This discovery marks the identification of the third ETS TF with autosomal dominant pathogenic germ line variants and HM and/or bone marrow failure (BMF) (in addition to ETS variant transcription factor 6 [ETV6]32 and FLI133,34) and adds to the growing list of master hematopoietic TFs already included in germ line–targeted sequencing panels for HM predisposition (RUNX1, CEBPA, GATA2, ETV6, MECOM, PAX5, and IKZF1).35 Our findings suggest a pathogenic role for ERG haploinsufficiency or hypomorphic actions in contrast with the prototypical oncogenic nature of ERG, thereby defining ERG deficiency syndrome as a new disease entity.9 This paradox implies that the consequence of dysregulated ERG may not be consistent across all spatial and temporal cellular contexts, a phenomenon that is not uncommon in hereditary HM predisposition (eg, GATA2).36 It also implies a strict expression threshold at which point dysregulation of ERG may upset the stoichiometry within a TF complex, leading to predisposition for and/or initiation of HM-related disease. We systematically examined the functional implications of ERG variants on DNA binding, subcellular localization, and transactivation of gene expression and focused on specific variants to demonstrate their effect on ERG-mediated myeloid differentiation and cytokine independence ex vivo and their impact on ERG-driven leukemia in an in vivo murine model.

Methods

Human and animal ethics

Samples were obtained from the Australian Familial Haematological Conditions Study, which was approved by the Women's and Children's Health Network Human Research Ethics Committee, Adelaide, Australia (approval 2020/HRE00981). All other patient samples and data were covered by local institutional human research ethics committees. Mouse experiments were done with approval from the Hudson Animal Ethics Committee in conjunction with the Monash University Animal Research Platform and the Monash Health Translation Precinct Animal Facility.

Gene discovery

Genomic DNA was extracted (QIAamp DNA Mini Kit, Qiagen), exonic sequences captured using xGen (Integrated DNA Technologies), and libraries sequenced using NextSeq 550 (Illumina) to an average depth of 50× (hair) and 100× (blood). In addition, polymerase chain reaction–free, short-read whole genome sequencing was performed at the Australian Genome Research Facility (Melbourne, Australia). Variant calling was performed using GATK (v3) (details in the supplemental Methods).

Identification of additional ERG variants in hematological cohorts

To identify additional kindreds with blood phenotypes and rare ERG variants, we contacted collaborators with existing genomic data obtained through routine clinical testing and research studies. GeneMatcher37 was used to further expand our patient cohort. All patient samples and data were covered by the local institutional human research ethics committees in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Luciferase assay

An integrin, alpha-2b (ITGA2B), in a pGL4.10-Luc vector was kindly donated by Marie-Christine Kopp (University of Sydney).33 K562 cells were seeded, transfected (Lipofectamine 2000), and then lyzed after 20 hours (Dual-Luciferase Reporter kit, Promega). pUC18 was used to normalize the amount of transfected DNA. Luciferase levels were measured using the Explorer Multimode Microplate Reader (Promega).

Immunofluorescence staining

COS-7 cells were transiently transfected with pcDNA3.1-ERG (Myc-tag) wild-type (WT) or variant expression vector, fixed after 20 hours (4% paraformaldehyde), and probed with anti-Myc antibody (9B11; New England Biolabs) and Alexa Fluor 488 Rabbit anti-mouse (A27023) secondary antibody. Fluorescent cells (100) were classified as nuclear (protein only in nucleus) or cytoplasmic (protein in nucleus and cytoplasm).

EMSA

Human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) cells were seeded, transiently transfected (Lipofectamine 3000), and lysates were prepared (RIPA 9806S, Cell Signaling Technology). Both biotin-labeled and unlabeled double-stranded DNA oligonucleotides containing an ERG binding site were synthesized (5' biotin-GGCACTCACTTCCGGCTTGGCCGTCGA-3'). Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) were performed using the LightShift Chemiluminescent EMSA kit (ThermoFisher) with 20 pmol probe.

ERG overexpression in FLCs

Fetal liver cells (FLCs) harvested from embryonic day 14.5 WT C57BL/6 mouse embryos were transduced (supplemental Methods, available on the Blood website) with MSCV-IRES-mCherry–based retrovirus containing either the ERG WT or ERG variants (P116R, M219I, D345N R370P, Y372∗, and Y373C).8 Transduced cells were cultured in StemSpan (STEMCELL Technologies) supplemented with interleukin-3 (IL-3) (10 ng/mL), IL-6 (10 ng/mL), Flt3L (50 ng/mL), SCF (50 ng/mL), and TPO (50 ng/mL). Fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis was performed weekly for 4 to 6 weeks. For cytokine independence assays, all cytokines were removed when cell populations reached 80% to 90% mCherry+. Cell viability and survival were measured every 3 days for 12 days.

In vivo leukemia model driven by ERG overexpression

MSCV-ERG-IRES-mCherry retrovirus–transduced FLCs (method as per “ERG overexpression in FLCs”) were cultured for 3 days before IV injection into sublethally irradiated 8-week-old C57BL/6 mice. The mice received neomycin water for 3 weeks after irradiation, and their blood was monitored every 2 weeks for mCherry expression.

Results

Identification of BMF and/or HM families and individuals with rare ERG variants

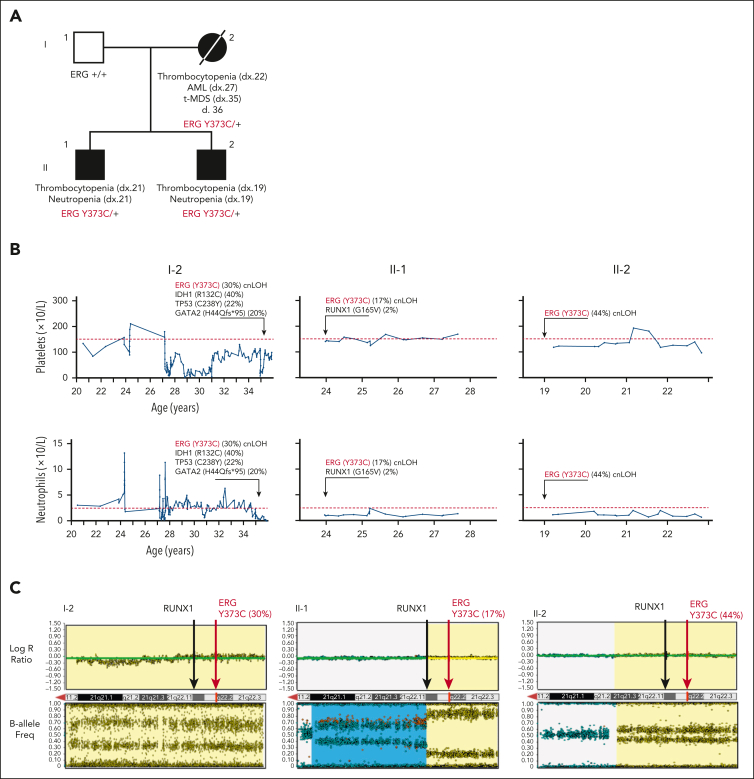

Family 1 presented with a range of hematological abnormalities that included thrombocytopenia, neutropenia, and AML (Figure 1A-B; supplemental Figure 1). Patient I-2 developed AML at 27 years of age. The patient entered morphologic remission, subsequently developed therapy-related MDS, and died at the age of 36 years (supplemental Figure 1). A gene panel analysis (supplemental Table 1) was conducted for all 3 affected family members and showed no germ line pathogenic variants in known BMF/HM predisposition genes. Whole exome sequencing analysis on the unaffected father confirmed the absence of any germ line variants that may explain the phenotypes seen in both children. Cytogenetic analysis identified a constitutional mosaic trisomy 8 in patient I-2 (supplemental Table 2), which was not present in either of her children and may have contributed to the myeloid malignancy progression. A pathogenic somatic RUNX1 (G165V) variant was identified in individual II-1 at a low variant allele frequency (VAF) (2%) that may be an early indicator or marker of clonal progression to malignancy. Platelet morphology studies for individual II-1 identified minor platelet abnormalities, including a slight increase in alpha granule numbers, a slight dilation of the open canalicular system, and mildly enlarged platelets, despite no noticeable mean platelet volume abnormalities (supplemental Figure 2A-B).

Figure 1.

Germ line ERG variant identified in a family with hematological conditions. (A) Pedigree of family 1 containing the ERG (Y373C) variant that segregates with thrombocytopenia and AML. Age of onset (years). (B) History of platelet and neutrophil counts of affected family members (patient 15, 16, and 17) (I-1, II-1, and II-2). Absolute neutrophil or platelet counts per microliter of blood from complete blood examinations plotted with age (years). Normal lower limit for neutrophils and platelets is marked with a dotted red line. (C) Log R ratio and B-allele plots of single-nucleotide polymorphism–array analysis. All individuals show a cnLOH event that encompasses the entire ERG gene (yellow highlight). Individual II-1 (patient 16) had a second cnLOH event (blue highlight). Log R ratios (top panels) show no loss of copy number, and B-allele frequencies (bottom panels) show regions of LOH, together demonstrating cnLOH. Samples used: patient I-2, BM cytogenetic pellet; II-1 and II-2, PB mononuclear cells. d, died; dx, diagnosed.

Whole exome sequencing analysis of all 4 individuals revealed heterozygosity of a novel ERG variant (chr21g.38383725T>C (hg38); c.1118A>G; p.Y373C) in the 3 affected individuals in that a highly conserved amino acid was altered, and it segregated with thrombocytopenia (Table 1; supplemental Figure 3A-B). This variant was absent in the general population (Genome Aggregation Database [gnomAD])38 and was predicted to disrupt DNA binding (supplemental Figure 3C). Interestingly, single-nucleotide polymorphism arrays identified copy neutral loss of heterozygosity (cnLOH) events on chromosome 21q that favored the ERG WT copy in all 3 carriers, strongly suggesting somatic genetic rescue (SGR) of the germ line deleterious ERG variant (c.1118A>G; VAF 30% [I-2], 17% [II-1], and 44% [II-2]; Figure 1C; supplemental Figure 3D). Intriguingly, cnLOH encompassed the entire RUNX1 gene in 2 patients (I-2 and II-2), and the recombination breakpoint in the most telomeric event in individual II-1 was within the RUNX1 gene (Figure 1C). With the addition of whole genome sequencing, we confirmed the presence of the cnLOH events, and the absence of deleterious variants in RUNX1, including noncoding and structural variations, that might explain the phenotype (supplemental Figure 4). Note, cnLOH favoring the WT is not a commonly described mechanism of somatic reversion in RUNX1-FPD.39

Table 1.

Rare heterozygous ERG variants and population variants

| Patient no. | Sex | ERG variant (479 aa) | VAF (%) | gnomAD v4.0.0 |

REVEL | Hematological-related phenotype |

Nonhematological phenotype |

Age onset of first phenotype (y) | Germ line ERG (inherited/de novo) (Sample) |

Somatic variants | Chr 21q cnLOH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | E20Vfs∗13 | 60 | 0 | NA | MDS | 38 | Yes (MSC) | No | ||

| 2 | F | P116R | 56 | 69 0.004% |

0.36 | Thrombocytopenia, thrombocytopathy, and platelet aggregation disorder | Hypertension, diabetes, cataract | 73 | No | ||

| 3 | V127Efs∗82 | 50 | 0 | NA | ALL | <18 | Yes | ||||

| 4 | I126T | 59 | 1 0.00016% |

0.512 | Chronic thrombocytopenia | Not reported in clinical records | <14 | Yes (SF) | FLT3-ITD and IDH1 | ||

| AML | 40 | ||||||||||

| 5 | M | R302C | 40 | 10 0.00068% (1× R302L) (17× R302H) |

0.365 | CLL | Not reported in clinical records | Unknown | Yes (hair) | ||

| 6 | F | P306L | 44 | 0 (6× P306W) | 0.394 | None | Lymphedema | <1 | Yes (inherited) (PB) |

No | |

| 7 | M | P306L | 57 | 0 (6× P306W) | 0.394 | None | Lymphedema | Yes | |||

| 8 | F | M341V | 45 | 0 | 0.45 | Severe congenital aplasia and abnormal B cells | Prematurity for acute fetal distress (33 wk) | 0 | Yes (inherited) (SF) |

None | |

| 9 | F | M341V | 45 | 0 | 0.45 | MDS | 56 | No | |||

| 10 | D345N | 24 | 1 0.00012% |

0.3149 | MDS | No | |||||

| 11 | D363A | 34 | 0 | 0.6209 | MDS | No | |||||

| 12 | M | R370H | 45 | 0 | 0.881 | Neutropenia | 0 | Yes (SF) | None (blood at 18 y) | ||

| Pancytopenia | 18 | ||||||||||

| 13 | M | R370P | 44 | 0 | 0.888 | MDS (asymptomatic thrombocytopenia and leukopenia) | Deformation (avascular necrosis) of femoral head, severe aortic valve insufficiency with secondary heart failure | 29 | Yes (hair) | None | No |

| 14 | M | Y372∗ | 48 | 0 | NA | Congenital pancytopenia, and BMF | 0 | Yes (de novo) (PB) |

|||

| 15 | F | Y373C | 30 | 0 | 0.852 | AML, thrombocytopenia, and t-MDS (RAEB2) | Not reported in clinical records | 27 | Yes (hair) | IDH1 (R132C) (40%) TP53 (C238Y) (22%) GATA2 (H442Qfs∗95) (20%) |

Yes |

| 16 | M | Y373C | 17 | 0 | 0.852 | Thrombocytopenia and neutropenia | Not reported in clinical records | 21 | Yes (inherited) (hair) |

RUNX1 (G165V) (2%) | Yes (2 events) |

| 17 | M | Y373C | 44 | 0 | 0.852 | Thrombocytopenia and neutropenia | Not reported in clinical records | 19 | Yes (inherited) (hair) |

None | Yes |

| 18 | K380N | 46 | 0 | 0.642 | Anemia, thrombocytopenia, pancytopenia, macrocytic anemia, abnormality of the spleen, and eosinophilic infiltration of the esophagus | Hemangioma, hepatosplenomegaly, gastrointestinal inflammation, erythema, and capillary malformation | >18 | Yes (de novo) (PB) |

No | ||

| 19 | F | Y388C | 50 | 0 | 0.90 | None | Lymphedema | 8 | Yes (inherited) (PB) |

No | |

| 20 | F | Y388C | 33 | 0 | 0.90 | None | Lymphedema (bilateral intermittent lower limb swelling) | 50 | Yes (PB) | Yes | |

| 21 | G394W | 15 | 0 (3× G394R) | 0.661 | t-AML after treatment for DLBCL and prostate cancer | DLBCL and prostate cancer | Yes (PB) | No | |||

| Population | M219I | 372 0.023% (1 hom) |

0.058 | NA | Yes | ||||||

| Population | P275S | 254 0.016% (3 hom) |

0.223 | NA | Yes | ||||||

| Mouse | S322P | 0 | 0.574 | ALL and thrombocytopenia | Yes | ||||||

| ETV6 | R370S | 0 | 0.803 | ALL | No | ||||||

| COSMIC | R385H | 0 (2× R385C) | 0.674 | NA | 2× BrCa, 1× biliary, 1× upper aerodigestive tract | No | |||||

| Population | P404A | 236 0.015% |

0.086 | NA | Yes |

Rare ERG variants (NP_891548.1) from similar phenotypic groups, including BMF and/or HM and lymphedema, among population variants (gnomAD >200),38 a germ line thrombocytopenic mouse mutation,1 a paralogous ETV6 pathogenic variant (thrombocytopenia),49 and COSMIC mutation (somatic).41 Information unavailable (blank); gnomAD v4.0.0, alternative variants at the same amino acid position (brackets).

Chr, chromosome; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; COSMIC, Catalogue Of Somatic Mutations In Cancer; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; F, female; hom, homozygous; M, male; NA, not applicable; MSC, mesenchymal stromal cells; PB, peripheral blood; REVEL, Rare Exome Variant Ensemble Learner; SF, skin fibroblasts; t-MDS, therapy-related myelodysplastic syndrome.

Through international collaborations and GeneMatcher37 (genotype matching resource), we identified an additional 13 rare ERG heterozygous variants associated with BMF- or HM-related disease and 2 associated with lymphedema that were identified in a primary lymphoedema cohort in the 100 000 Genomes Project.40 This included 15 probands; 12 were confirmed germ line variants, including 2 de novo (Table 1; supplemental Table 2; supplemental Figure 5), and germ line samples were not available for the remaining 3 variants. Three variants were predicted to cause premature protein termination and 10 were missense variants that clustered within the ETS domain (310-395 aa). For 4 missense variants, the Rare Exome Variant Ensemble Learner (REVEL) scores indicated pathogenicity (score >0.85; Table 1; supplemental Figure 6). To determine the prevalence of rare ERG variants in different study cohorts, we tabulated the number of patients screened, phenotypes encompassed, and number of ERG variants found, including multiple cohorts without rare ERG variants (supplemental Table 3). Because of the wide range of phenotypes covered by different research cohorts, the associated ascertainment biases, and the inconsistent variant filtering strategies, determining the prevalence or penetrance of germ line pathogenic ERG variants to different phenotypes remains to be determined and requires the incorporation of additional well-defined cohort studies and systematic analyzes.

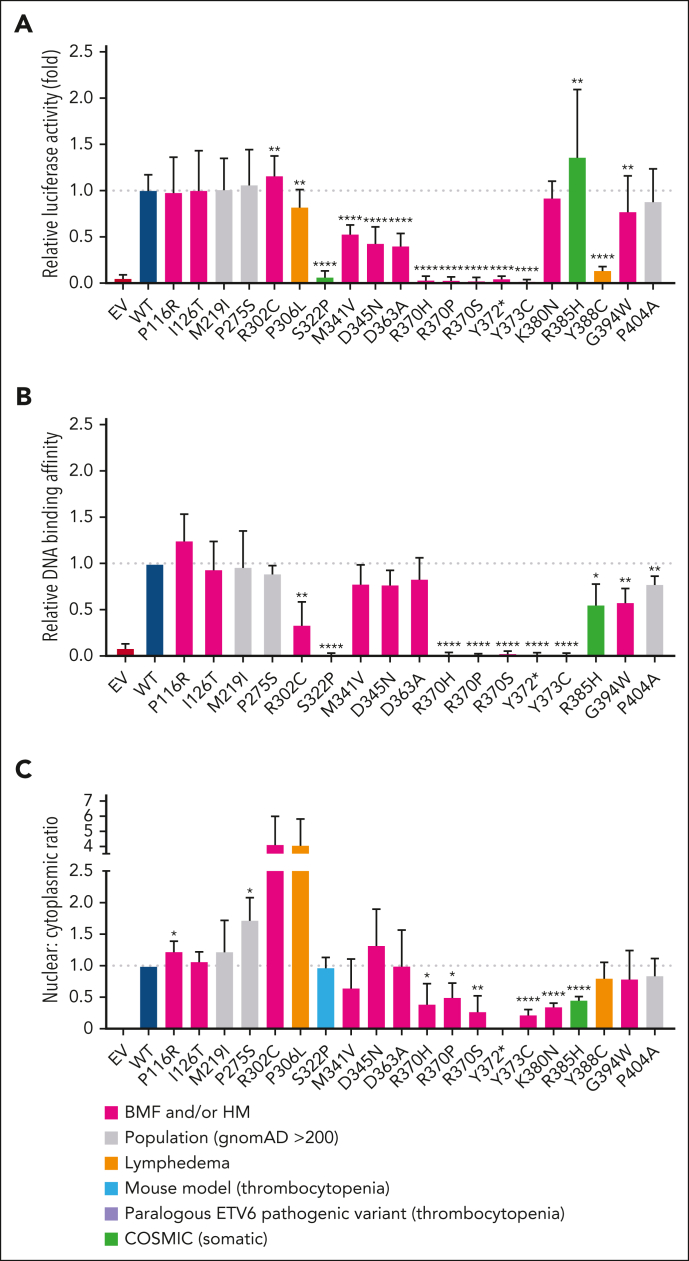

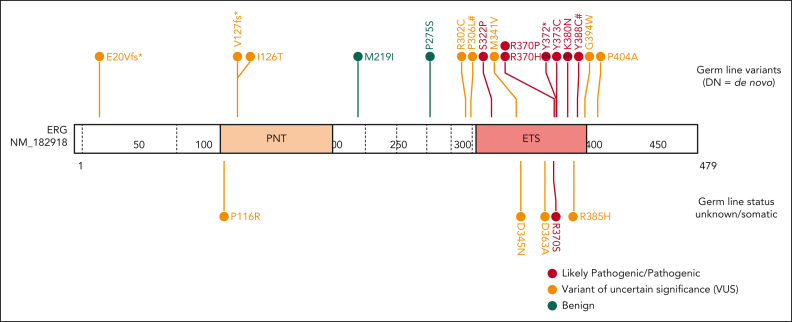

In vitro functional characterization of ERG variants

The impact of ERG variants on transactivation, DNA binding, and nuclear localization was examined (Figure 2). Western blot analysis showed all ERG variants produced protein, except for Y372∗, which was unstable (supplemental Figure 7). To assess transactivation ability, assays were performed using a platelet-specific ITGA2B promoter-luciferase reporter in K562 myeloid cells. Most ETS domain variants showed either complete LOF (S322P, R370H/P/S, Y372∗, Y373C, and Y388C) or were hypomorphic (M341V, D345N, and D363A) when compared with the WT (Figure 2A). In contrast, a somatic variant (R385H), reported in multiple cancers in the COSMIC (Catalogue Of Somatic Mutations In Cancer),41 and R302C increased transactivation. ERG variants observed more than once in the population (ie, >0.00012% gnomAD27; supplemental Figure 8) showed no impact on the transactivation ability in this assay (Figure 2A; Table 1).

Figure 2.

Functional characterization of ERG variants. (A) ERG variants residing in the ETS domain reduce transactivation. K562 cells were transfected with pcDNA3 empty vector (EV) or pcDNA3-ERG (WT or variants). All constructs were cotransfected with a luciferase reporter plasmid driven by an ITGA2B promoter (quadruplicate replicates, repeated 3 times). Fold change (mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM]) in comparison with the WT is plotted. Pairwise comparisons are shown (∗P < .05 in comparison with WT). (B) ETS domain variants reduce ERG DNA binding affinity. EMSA of WT ERG and variants. Transfected HEK293 whole cell lysates were prepared and bound to an oligonucleotide containing an ETS DNA consensus sequence. Probes were visualized using chemiluminescence. Pairwise comparisons are shown (∗P < .05 compared with WT). (C) ERG ETS domain variants alter subcellular localization. A Myc-tag was added to WT ERG and variants. COS-7 cells were transfected with pcDNA3 EV, pcDNA3-ERG-Myc (WT), and pcDNA3-ERG-Myc variants. Cells were stained for a Myc-tag and DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole). The nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio of each variant was quantified and the fold change (mean ± SEM) in comparison with the WT was plotted. Pairwise comparisons are shown (∗P < .05 compared to WT). Nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio was obtained from 3 independent experiments. In all comparisons, a Student t test was used (∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗∗P < .001 in comparison with WT).

EMSA were performed to measure the effect of ERG variants on DNA binding (Figure 2B; supplemental Figure 9). Several ETS domain variants (S322P, R370H/P/S, Y372∗, and Y373C) entirely ablated DNA binding, consistent with R370 and Y373 being critical contacts for DNA binding (supplemental Figures 3C and 10).42

Immunofluorescence was used to quantify the effect of ERG variants on subcellular localization (Figure 2C). R302C and P306L displayed an increased nuclear to cytoplasmic localization ratio, but this effect was not statistically significant. Conversely, ETS domain variants R370H/P/S, Y372∗, Y373C, K380, and R385H reduced nuclear protein localization (∗P < .05; Figure 2C; supplemental Figure 11A). Equivalent amino acid residues to ERG (R370, Y373) in this highly conserved ETS domain in ETV6 (R399)43 and FLI (Y343),44 respectively, are similarly critical for proper nuclear localization of these TFs (supplemental Figure 11B).

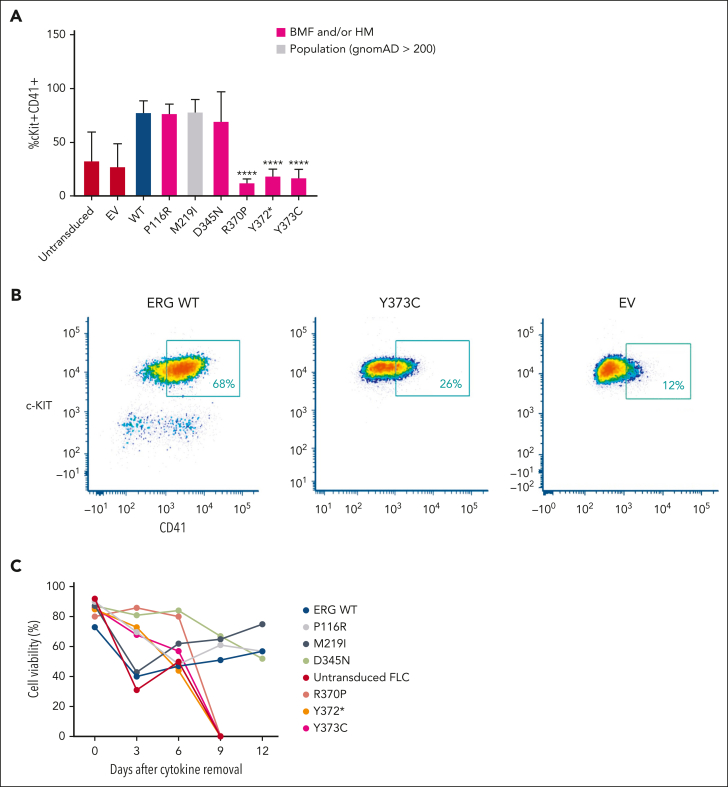

ERG LOF variants failed to drive myeloid differentiation and expansion of cytokine-independent stem or progenitor cells in FLC cultures

Retroviral-driven expression of WT ERG in FLCs drives the expansion of an immature stem or progenitor cell population with megakaryocytic features as demonstrated by intermediate cKIT+ and high CD41+ cell surface expression8 (Figure 3A-B). Several representative variants, including 3 complete LOF variants, 1 hypomorphic variant, and 2 WT-like variants from in vitro assays, were chosen to study their effect on ex vivo ERG-driven megakaryocytic expansion and cytokine-independent cell growth. Like the WT, P116R, a population (ie, benign) variant (M219I), and a hypomorphic variant (D345N) also drove this expansion. Strikingly, the ETS domain complete LOF variants (R370P, Y372∗, and Y373C) did not show expansion of this immature stem or progenitor cell population after 4 to 5 weeks in culture, thereby replicating nontransduced FLCs or FLCs transduced with an empty MSCV-IRES-mCherry control retrovirus empty vector.

Figure 3.

ERG LOF variants fail to drive megakaryocytic differentiation and cytokine independence. (A) In vitro differentiation of FLCs that overexpress WT ERG and variants. Immature stem or progenitor cell population with megakaryocytic features were stained using antibodies against cKIT+ and CD41+ with the percentage of double positive cells measured by flow cytometry (6 independent experiments). Pairwise comparisons are shown (∗∗∗∗P < .001 in comparison with WT). In all comparisons, a Student t test was used. (B) Example of gating strategy for cKIT+ and CD41+ expression on ERG WT– or variant-transduced FLCs. Cells were first gated for viability and mCherry expression. (C) Cell viability of FLC culture after cytokine removal measured over time.

Furthermore, we observed that ERG WT and the P116R, M219I, and D345N variants were each able to induce cytokine independence in FLCs after 6 weeks in culture, thereby driving cell survival in the absence of essential cytokines. Conversely, ETS domain complete LOF variants (R370P, Y372∗, and Y373C) were not able to drive cytokine-independent growth with all cells dying within 9 days of cytokine removal (Figure 3C), thereby replicating nontransduced FLCs.

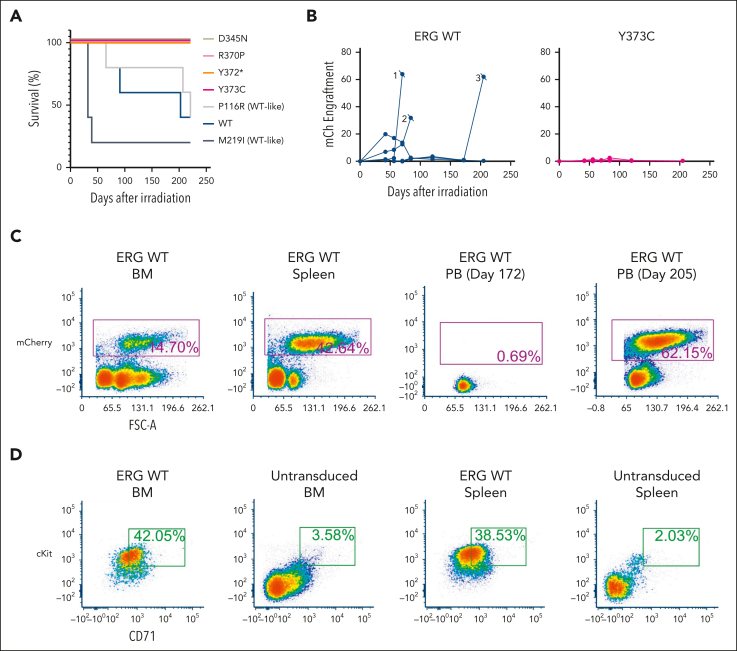

Complete LOF ERG variants failed to drive leukemia in an ERG overexpression mouse model

Overexpression of ERG in murine FLCs, followed by transplantation into sublethally irradiated C57BL/6 mice, led to the development of a well-described erythro-megakaryocytic leukemia that is characterized by an accumulation of immature erythroblasts that infiltrate the BM, spleen, liver, and lung.8,10,45 Enforced expression of ERG WT, a WT-like variant (P116R), and a population variant (M219I) in murine FLCs similarly drove the development of erythro-megakaryocytic leukemia (Figure 4A) by mCherry engraftment (Figure 4B) within 220 days after transplantation in 10 of 15 animals. Moribund mice displayed a large liver and spleen (supplemental Figure 12A), and flow cytometric analysis of the BM and spleen revealed a cKit+CD71+mCherry+ leukemic cell population consistent with ERG-driven erythro-megakaryocytic leukemia (Figure 4C-D), as previously described.8 Histology further confirmed leukemic cell infiltration in the BM, spleen, and liver (supplemental Figure 12B). In contrast, all mice (20/20) that received the ERG ETS domain complete (R370P, Y372∗, and Y373C) or hypomorphic (D345N) variants showed no signs of disease or mCherry+ PB cells in the first 220 days, thereby demonstrating LOF in this in vivo assay. Notably, 1 variant (D345N) is hypomorphic in transactivation assays (Figure 2A), acts WT-like in cytokine independence assays (Figure 3A,C), and has complete LOF in this murine erythroleukemia assay (Figure 4A). Hence, the choice of assay(s) is critical in ERG functional studies, especially when applying to variant classification for diagnostic and clinical applications.

Figure 4.

ERG variants are LOF in an in vivo leukemia model driven by ERG overexpression. (A) Enforced expression of ERG WT and WT-like variants (P116R, M219I) in mice led to the development of erythro-megakaryocytic leukemia within 220 days. (B) mCherry engraftment over time in the PB of mice. Numbering refers to 3 ERG WT mice that succumbed to disease (Figure 5A). (C) Infiltration of ERG WT/mCherry+ transplanted FLCs into recipient mouse BM, spleen, and PB as measured by fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis. Recipient mouse number 3 shown is representative of all ERG WT and WT-like (P116R, M219I) mice. (D) ERG WT and WT-like variant mice developed mCherry+ erythro-megakaryocytic leukemia with cKit+ and CD71+ expression. FACS plots of a representative ERG WT leukemia are shown. Nonleukemic (ie, mCherry–) BM and spleen cells are shown as comparison.

Classification of germ line ERG variants and their phenotypes

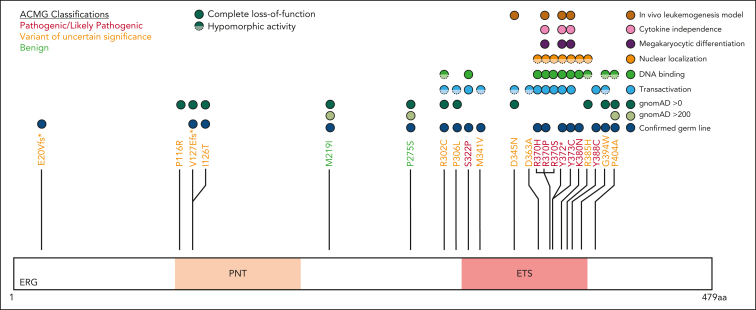

Based on clinical, in silico predictive and functional data, all ERG variants were classified using the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) and the Association for Molecular Pathology criteria and using heterozygous LOF variants (including missense) and the consequent haploinsufficiency as the disease mechanism46 (supplemental Table 2). The ERG ETS domain is highly conserved (average constraint score, 0.26; supplemental Figure 13; supplemental Table 4),47 and LOF variants across the protein are rare in the normal population (LOEUF = 0.23 and pLI = 1, gnomADv4.0.0; supplemental Figure 8),38 suggesting intolerance to haploinsufficiency.

Five variants associated with BMF/HM (R370H, R370P, Y372∗, Y373C, and K380N) demonstrated complete LOF in one or more functional assays and were classified as pathogenic, whereas Y388C (lymphedema) was classified as likely pathogenic (Figure 5; supplemental Table 5). Consistent with other BMF/HM predisposition genes, we observed variability in the clinical presentation associated with these variants. Thrombocytopenia, neutropenia, or pancytopenia was diagnosed in all patients with a likely pathogenic or pathogenic ERG variant (Table 1; supplemental Figure 14A; supplemental Table 2). Among this cohort, 28% developed an HM (AML and/or MDS) with a median age of onset of 29 years (supplemental Figure 14B). Longitudinal monitoring of individuals 10, 11, 15 (II-1), and 16 (II-2) consistently showed thrombocytopenia (platelets <150 × 109/L) and neutropenia (<2.0 × 109/L; supplemental Figure 14C-D).

Figure 5.

ACMG classification of germ line ERG variants.ERG variants were classified using the ACMG and the Association for Molecular Pathology criteria for cytopenias, HMs, and/or lymphedema (#). Based on functional assay criteria, variants with complete LOF in at least 1 functional assay were classified as PS3_Strong, variants with hypomorphic activity (<50%) in 1 or more functional assays were classified as PS3_Moderate, and variants with hypomorphic activity (>50%) in 1 or more assays were classified as PS3_Supporting. The PS3 and BS3 criteria were not applied when variants showed no change in functional assays or were not tested. PNT, pointed domain.

Ten variants were classified as variants of uncertain significance (VUS), including 4 variants (M341V, D345N, D363A, and G394W) that demonstrated complete LOF or were hypomorphic in transactivation, DNA binding, and/or erythroleukemia assays and 1 variant (V127Efs∗82) that is likely to be pathogenic based on complete LOF of other premature termination variants (ie, Y372∗ and lymphedema variants31; Figure 5). Seven VUSs were associated with HM (MDS, AML, ALL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma), 3 with BMF, and 1 with lymphedema. Note, 1 patient with thrombocytopenia who carried a germ line I126T variant also harbored a germ line pathogenic RUNX1 whole gene deletion (supplemental Table 2), likely explaining the phenotype; whether the ERG variant also contributed to the phenotype is unclear. Two variants (D345N and D363A) could not be verified as germ line because of unavailability of samples and have been reported multiple times as somatic with D363 being a hot spot for somatic variants in multiple cancers (supplemental Figure 15; supplemental Table 6). Somatic analysis of BM or blood identified variants in patients 2, 3, 7, 14, 15, and 16, 2 of whom (3 and 16) acquired IDH1 variants; no variants were found in patients 11 and 12 (Table 1).

Somatic ERG variants in HM and other cancers

The COSMIC was filtered for ERG variants that occurred ≤3 times (ie, very rare) in gnomAD v4.0.0. There were 64 unique ETS domain missense variants. Screening for somatic missense variants at the same amino acids affected by germ line ETS domain variants in this study revealed that all except 1 (Y373C) were considered to be somatic (supplemental Figure 15), adding weight to these amino acid substitutions being drivers of malignancy.

In a separate pediatric familial cancer cohort (St Jude Children’s Research Hospital), a single germ line ERG (V127Efs∗82) variant was identified (Table 1), in addition to several predicted pathogenic somatic ERG variants, predominantly in children with B-ALL, but also AML, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and some solid cancers (supplemental Table 6). Interestingly, ERG (V127Efs∗82) was identified both as a germ line and a somatic variant in different patients with B-ALL.

Discussion

We reported the discovery of ERG as a new autosomal dominant BMF and HM predisposition gene, expanding its disease phenotypes beyond recently reported primary lymphedema.31 ERG-based clinical disease resembles that of RUNX1,48 ETV649 and ANKRD2650 (thrombocytopenia, myeloid, and lymphoid HM), GATA236,51 (BMF, myeloid HM, lymphedema), and ERG’s most closely related ETS family member FLI1 (thrombocytopenia, but to date without reports of HM).33,34,52,53 These overlapping, but nonidentical, phenotypes are consistent with many of these TFs being part of a complex homeostatic network that is crucial for normal hematopoiesis.5 Furthermore, consistent with a role for ERG and GATA2 in the lymphatics and predisposing to lymphedema, in single cell studies, there is high expression of ERG and GATA2 in BM endothelial cells in contrast with RUNX1 for which no primary lymphatic phenotype has been described.54

Intriguingly, cnLOH favoring the WT allele was identified in all 3 ERG (Y373C) carriers in index family 1. SGR events such as these can complicate the detection of germ line variants from hematopoietic tissues by mimicking the lower VAFs of somatic variants. Consistent with this, individuals with either Y388C or S182Afs∗22 (recently published familial germ line ERG variant in a patient with lymphedema31) had cnLOH but no hematological disease (supplemental Figure 16). Notably, the patient with S182Afs∗22 presented with 4% VAF in the PB,31 which, upon further investigation, was caused by a cnLOH event that corrected 92% of cells. SGR may lead to asymptomatic carriers, milder symptoms, a later age of onset, or a missed diagnosis (hidden predisposition) and reveals the potential for disease prevention via cell and/or gene therapy.55,56 Hence, identified ERG variants should be tested in germ line, nonhematopoietic tissues, such as fibroblasts, mesenchymal stromal cells or hair, to confirm germ line or somatic status.

Functional studies demonstrated that all rare ERG variants within the ETS domain led to complete or hypomorphic LOF in transactivation, DNA binding, and/or subcellular localization, and selected variants similarly exhibited LOF in fetal liver hematopoietic cell growth assays ex vivo and leukemogenic assays in vivo. This is in contrast with the gain-of-function nature of common ERG fusions19, 20, 21,27,28 and hence shows that ERG can act as both a tumor suppressor gene and an oncogene. Notably, disease manifestations stemming from germ line LOF mechanisms extend to other members of the ETS family (ETV6 and FLI1).33,34,52,53 ETV6 and FLI1 variants often cluster in the ETS domain,32 and several are analogous to pathogenic ERG variants in our study (supplemental Figure 11B). For example, a single consanguineous family with 2 siblings affected with moderate thrombocytopenia and a lifelong bleeding history was described to have a rare FLI1 ETS domain missense variant in homozygosity (R324W, NM_002017.4).33 This variant (analogous to ERG R354) was hypomorphic in in vitro analyzes,33 similar to 3 variants in our study in the same region (M341V, D345N, and D363A) (Figure 2A). To date, we have not seen patients with homozygous ERG germ line variants or evidence of autosomal recessive disease, although this might be possible for hypomorphic variants.

Structural modeling shows that several complete LOF variants (in DNA binding and transactivation assays) affect residues that contact DNA (supplemental Figure 9).42 In addition, the nuclear localization 2 region of the FLI1 protein is identical to this ETS domain region in ERG.44,57 Unsurprisingly, 6 variants within this paralogous region were unable to appropriately localize to the nucleus (Figure 2C; supplemental Figure 10). Therefore, because of the high conservation of the ETS domain in paralogous TFs, reported function-disrupting variants in 1 ETS TF are likely to affect protein function at the corresponding amino acid position in others. Indeed, paralogous amino acids cause similar loss of DNA binding and nuclear localization and several have been classified in ClinVar as pathogenic for their relevant disease phenotypes. Pathogenic variants and their functional analyzes in highly conserved paralogous genes and domains, such as ETS TFs and ETS domains, is topical for variant curation expert panel discussion in generating gene-specific guidelines.

In addition to germ line variants, ERG somatic variants are found in a proportion of sporadic cancers, including HM (B-ALL, MDS, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, AML, and T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia) and solid cancers (predominantly skin, gastrointestinal, breast, lung). Interestingly, the majority of the missense variants in HMs are located within the ETS domain with several variant hotspots, including ones we tested (ie, D345N, D363A), that were hypomorphic in our system; this raises the likelihood of a strict threshold for ERG activity in certain cellular contexts, including concurrent with other somatic variants. For germ line ERG HM cases, as for GATA2, we have not identified somatic variants on the other allele (ie, biallelic) as occurs for RUNX1,58 CEBPA,58,59 and ETV643).

Our data establishes a gene-disease association for ERG in the pathogenicity of BMF and HM, in addition to lymphedema. Six ETS domain variants in this study were classified as pathogenic or likely pathogenic, whereas 10 variants were classified as VUS (Figure 5). Addition of functional data criteria changed the ACMG classification of 5 ERG variants (3 VUS to likely pathogenic, 2 VUS to benign; supplemental Table 5), highlighting the importance of generating faithful functional assays. For the VUSs, despite their seemingly WT-like behavior in functional assays, it remains plausible that some may have critical functional consequences that were not detected in our overexpression systems. The functional consequences of these variants may impact via temporal and spatial mechanisms, and therefore caution is required when interpreting WT-like VUS because protein-protein interactions or target binding may vary in different cellular contexts. It is probable, however, that some variants classified as VUS (ie, I126T and P116R) are not monogenic, fully penetrant variants given their lack of functional consequence in the overexpression assays used in this study.

Our data (Table 2; Figure 6) defines ERG as a new predisposition gene to be added to germ line screening panels for BMF and HM syndromes. Demonstration of de novo germ line variants emphasizes testing for inheritance for family planning and counseling. We stress the importance of screening true germ line samples of patients and family members because we posit that SGR and the use of hematopoietic samples may mask asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic carriers, potentially missing more severe clinical presentation in other family members, including perinatal and neonatal lethality as has been observed in MECOM.60,61 Enticingly, SGR highlights the potential for preemptive cell therapy and/or gene editing strategies to prevent or alleviate ERG-related disease in the blood stem cell compartment. We only observed several inherited cases (4 small families), which may indicate low penetrance, mild phenotypes, and/or incomplete family data. However, of the 3 families in the Genomics England Rareservoir study with primary lymphedema carrying ERG premature termination variants31 and 2 missense ERG variants reported here, 4 showed familial inheritance and 1 was de novo. Whether lymphedema is a highly penetrant phenotype and hence seen in family units remains unanswered. Although ERG variants in lymphedema and HM phenotypes have not yet coincided, we anticipate that with a larger, more defined cohort study they will overlap, mirroring the history of GATA2 variants and Emberger syndrome (lymphedema and MDS).51

Table 2.

Summary of functional assays for phenotypic ERG variants in this study

| Variant | Phenotypes | Transactivation | DNA binding | Subcellular localization | FLC myeloid differentiation | FLC cytokine independence | Leukemogenesis assay | ACMG classification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | NA | ✓✓✓✓ | ✓✓✓✓ | ✓✓✓✓ | ✓✓✓✓ | ✓✓✓✓ | ✓✓✓✓ | NA |

| I126T | AML | ✓✓✓✓ | ✓✓✓✓ | ✓✓✓✓ | ND | ND | ND | VUS |

| P116R | Cytopenia | ✓✓✓✓ | ✓✓✓ | ✓✓✓✓ | ✓✓✓✓ | ✓✓✓✓ | ✓✓✓✓ | VUS |

| R302C | CLL | ✓✓✓✓ | ND | ✓✓✓✓ | ND | ND | ND | VUS |

| K380N | Cytopenia | ✓✓✓✓ | ✓✓✓ | ✓ | ND | ND | ND | P |

| P306L | Lymphedema | ✓✓✓ | ND | ✓✓✓✓ | ND | ND | ND | VUS |

| G394W | AML | ✓✓✓ | ✓✓✓✓ | ✓✓✓✓ | ND | ND | ND | VUS |

| M341V | Cytopenia | ✓✓ | ✓✓✓✓ | ✓✓✓✓ | ND | ND | ND | VUS |

| D345N | MDS | ✓✓ | ✓✓✓✓ | ✓✓✓✓ | ✓✓✓✓ | ✓✓✓✓ | ✖ | VUS |

| D363A | MDS | ✓✓ | ✖ | ✓✓✓✓ | ND | ND | ND | VUS |

| Y388C | Lymphedema | ✖ | ND | ✓✓✓✓ | ND | ND | ND | LP |

| R370H | Cytopenia | ✖ | ✖ | ✓✓ | ND | ND | ND | P |

| R370P | Cytopenia + MDS | ✖ | ✖ | ✓✓ | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | P |

| Y373C | Cytopenia + AML | ✖ | ✖ | ✓ | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | LP |

| Y372∗ | Cytopenia | ✖ | ✖ | ✓ | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | P |

| E20Vfs∗13 | MDS | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | VUS |

| V127Efs∗82 | ALL | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | VUS |

ERG variants are ordered in descending order of transactivation ability. Ticks (✓) indicate degree of WT-like activity in transactivation, DNA binding, subcellular localization, FLC myeloid differentiation, FLC cytokine independence, and leukemogenesis assays. ✖ indicates complete LOF in these assays.

CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; LP, likely pathogenic; NA, not applicable; ND, not determined; P, pathogenic.

Figure 6.

Functional consequences of rare ERG variants. Rare ERG variants from similar phenotypic groups, including BMF and/or HM and lymphedema, among population variants (gnomAD >200),38 a germ line thrombocytopenic mouse variant,1 a paralogous ETV6 pathogenic variant (thrombocytopenia),49 and Catalogue Of Somatic Mutations In Cancer mutation (somatic)41 are mapped onto the ERG protein (isoform, NP_891548.1; transcript, NM_182918.4). Functional characterization of each variant via transactivation, DNA binding, subcellular localization, FLC myeloid differentiation, FLC cytokine independence, and leukemogenesis assays are displayed.

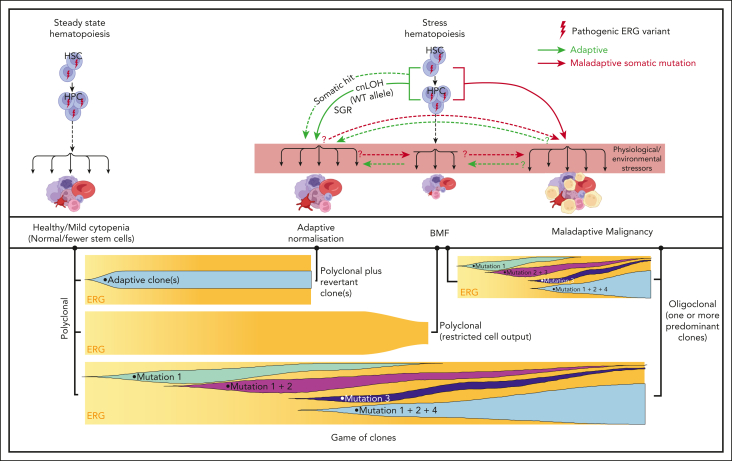

Our current disease model (Figure 7) proposes that, in ERG carriers, the interplay between physiological and environmental stressors impacts critical threshold-sensitive gene expression or biologic pathways that are required for normal hematopoiesis, which leads to BMF and adaptive (SGR) and/or maladaptive (hematological malignancy) selective processes. It is possible for both adaptive and maladaptive clones to be present in the same individual for whom context-dependent competitive fitness of the clone determines the physiological outcome, a game of clones. Notably, ERG expression is high in primary human HSCs and it drops during transition to hematopoietic progenitor cells (HPCs)62 and during differentiation. Analysis of the ERG downstream effectors and pathways impacted in primary BM and blood cells in ERG carriers and patients with BMF/HM is warranted to better understand disease initiation and progression. Clearly, describing these disease mechanisms, the phenotypic and mutational spectrum, and the natural history of diseases caused by ERG germ line variants has only just commenced for what may well be another pleiotropic and protean transcriptopathy. As population-scale genomic studies, such as the UK Biobank and All of Us, become popular, our study demonstrates that they should not become de rigueur. Careful clinical and laboratory observations with professional networking will remain important in describing new ERG-associated disease and other disease entities.

Figure 7.

Proposed model for ERG deficiency syndrome–associated phenotypes showing adaptive/maladaptive events in ERG heterozygous carriers. It is proposed that ERG carriers harbor a threshold of activity that is insufficient under certain physiological and environmental stressors, thus leading to a range of phenotypic outcomes (top panel). Malignant cells (yellow cells). Maladaptive and adaptive events observed in our study (arrow). Other potential (maladaptive/adaptive) somatic events seen in other BMF and/or HM predisposition genes63, 64, 65 (dotted arrow) or hypothetical events (question mark preceding dotted arrow). Game of clones (bottom panel). The development of different physiological outcomes in patients is the consequence of a game of clones in which context-dependent competitive fitness of the clone(s) determines progression and the observed outcome. Notably, adaptive and maladaptive events and subsequent clonal selection may occur simultaneously. The clonal output shown is based on mature blood cells, reflecting collectively the impact on mature and stem and progenitor cells.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: A.C. is an employee of and stockholder in Illumina, Inc. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

A complete list of the members of the ERG Variants Research Network appears in the supplemental Appendix.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the families and individuals for their participation in these studies. The authors also acknowledge the RUNX1 Research Program for their consumer voice and advocacy in germ line thrombocytopenia and leukemia predisposition and the Monash University Histology Platform, Monash University Animal Research Platform, and Monash Health Translation Precinct Animal Facility and Flowcore.

This research was supported by funding from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (grants APP1024215, APP1164601, APP1023059, and APP1182318); a Catalyst Grant for Model Organism/System Study through the Australian Functional Genomics Network, Medical Research Future Fund (MRFF) (grant MRF2007498); a Cancer Council Project Research Project (grant APP1125849); The Hospital Research Foundation (P.A.); Maddie Riewoldt’s Vision (MRV0017 fellowship [P.V.]); the University of South Australia, Centre for Cancer Biology funding (P.V. and C.C.H.); a MRFF Early to Mid-Career Researchers grant (APP2023357); the Royal Adelaide Hospital Research Fund (fellowship [P.A.]); The University of Adelaide Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship (J.R.Z.); the Leukaemia Foundation of Australia Strategic Ecosystem Research Partnerships grant (A.L.B., L.A.G., and C.C.H.); the Peter Nelson Leukemia Research Fellowship, Cancer Council South Australia (C.C.H.); the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (K.E.N. and N.O.); the Swiss Federal National Fund Scientific Research (CRSII5_177191/1); the UK Research and Innovation Medical Research Council (MR/P011543/1); and the British Heart Foundation (RG/17/7/33217 and PG/20/16/35047). Identification of ETS-related gene–associated lymphedema samples was made possible through access to data in the National Genomic Research Library, managed by Genomics England Limited (a wholly owned company of the Department of Health and Social Care). The National Genomic Research Library holds data provided by patients and collected by the National Health Service (NHS) as part of their care and data collected as part of their participation in research. The National Genomic Research Library is funded by the National Institute for Health Research and the NHS England. The Wellcome Trust, Cancer Research UK, and the Medical Research Council have also funded research infrastructure. This work was produced with the financial and additional support of Cancer Council South Australia Beat Cancer Project on behalf of its donors and the State Government of South Australia through the Department of Health (Principal Research Fellowship [H.S.S.]).

Authorship

Contribution: J.R.Z. wrote the manuscript and was involved in all aspects of the project including research design, manuscript preparation, and collecting and analyzing experimental and clinical data; A.L.B., C.L.C., H.S.S., and C.N.H. were involved in the research design, data analysis, manuscript writing and preparation, American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics–variant classification, and providing scientific insight; C.C.H., P.A., and P.V. contributed to different aspects of design and analysis of clinical and experimental data and manuscript writing and preparation; X.L., S.J.S., and L.T. helped to collect experimental data; M.B. and P.J.B. helped with sample preparation; L.A.-M. and K.S.K. performed bioinformatic analyses; S. Moore, R.H., W.T.P., and H.N. performed cytogenetic, somatic next-generation sequencing, and/or diagnostic arrays for family 1; S.B. and M.W.W. were involved in figure generation; S.F., L.L., F.S.d.F., S. Demirdas, S.d.M., H.A.-P., B.B., S. Mansour, K.G., A.K., S. Dobbins, P.G.N.J.M., K.E.N., N.O., D.D., R.M., A.C., J.M., D.B., J.F.-D., M.W.D., K.P., N.K.P., G.M.B., D.P., P.O., A.S., L.A.G., D.M.R., D.K.H., and J.S. provided clinical and variant information of patients; M.W.W. and the ERG Variant Research Network confirmed the absence of rare ERG variants in their cohorts; and all authors critically reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Footnotes

C.C.H., P.A., and X.L. are joint second authors.

H.S.S. and C.N.H. are joint senior authors.

Original data are available on request from the corresponding authors, Christopher N. Hahn (chris.hahn@sa.gov.au) and Hamish S. Scott (hamish.scott@sa.gov.au).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Contributor Information

Hamish S. Scott, Email: hamish.scott@sa.gov.au.

Christopher N. Hahn, Email: chris.hahn@sa.gov.au.

ERG Variants Research Network:

Panagiotis Baliakas, Piers Blombery, Lucy C. Fox, Jean Donadieu, Ana Rio-Machin, Orna Steinberg-Shemer, Neil V. Morgan, Joanne Y. Y. Ngeow, Julia Skokowa, Mark Pinese, and Mark J. Cowley

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Wilson NK, Foster SD, Wang X, et al. Combinatorial transcriptional control in blood stem/progenitor cells: genome-wide analysis of ten major transcriptional regulators. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7(4):532–544. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thoms JAI, Truong P, Subramanian S, et al. Disruption of a GATA2-TAL1-ERG regulatory circuit promotes erythroid transition in healthy and leukemic stem cells. Blood. 2021;138(16):1441–1455. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020009707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zerella JR, Homan CC, Arts P, Brown AL, Scott HS, Hahn CN. Transcription factor genetics and biology in predisposition to bone marrow failure and hematological malignancy. Front Oncol. 2023;13 doi: 10.3389/fonc.2023.1183318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Loughran SJ, Kruse EA, Hacking DF, et al. The transcription factor Erg is essential for definitive hematopoiesis and the function of adult hematopoietic stem cells. Nat Immunol. 2008;9(7):810–819. doi: 10.1038/ni.1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diffner E, Beck D, Gudgin E, et al. Activity of a heptad of transcription factors is associated with stem cell programs and clinical outcome in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2013;121(12):2289–2300. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-07-446120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Knudsen KJ, Rehn M, Hasemann MS, et al. ERG promotes the maintenance of hematopoietic stem cells by restricting their differentiation. Genes Dev. 2015;29(18):1915–1929. doi: 10.1101/gad.268409.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ng AP, Loughran SJ, Metcalf D, et al. Erg is required for self-renewal of hematopoietic stem cells during stress hematopoiesis in mice. Blood. 2011;118(9):2454–2461. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-344739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carmichael CL, Metcalf D, Henley KJ, et al. Hematopoietic overexpression of the transcription factor Erg induces lymphoid and erythro-megakaryocytic leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(38):15437–15442. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1213454109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salek-Ardakani S, Smooha G, de Boer J, et al. ERG is a megakaryocytic oncogene. Cancer Res. 2009;69(11):4665–4673. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsuzuki S, Taguchi O, Seto M. Promotion and maintenance of leukemia by ERG. Blood. 2011;117(14):3858–3868. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-11-320515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xie Y, Koch ML, Zhang X, et al. Reduced Erg dosage impairs survival of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Stem Cell. 2017;35(7):1773–1785. doi: 10.1002/stem.2627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nikolova-Krstevski V, Yuan L, Le Bras A, et al. ERG is required for the differentiation of embryonic stem cells along the endothelial lineage. BMC Dev Biol. 2009;9:72. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-9-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu F, Patient R. Genome-wide analysis of the zebrafish ETS family identifies three genes required for hemangioblast differentiation or angiogenesis. Circ Res. 2008;103(10):1147–1154. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.179713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marcucci G, Baldus CD, Ruppert AS, et al. Overexpression of the ETS-related gene, ERG, predicts a worse outcome in acute myeloid leukemia with normal karyotype: a Cancer and Leukemia Group B study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(36):9234–9242. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.6137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Metzeler KH, Dufour A, Benthaus T, et al. ERG expression is an independent prognostic factor and allows refined risk stratification in cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia: a comprehensive analysis of ERG, MN1, and BAALC transcript levels using oligonucleotide microarrays. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(30):5031–5038. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.5328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baldus CD, Liyanarachchi S, Mrózek K, et al. Acute myeloid leukemia with complex karyotypes and abnormal chromosome 21: amplification discloses overexpression of APP, ETS2, and ERG genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(11):3915–3920. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400272101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zaliova M, Zimmermannova O, Dörge P, et al. ERG deletion is associated with CD2 and attenuates the negative impact of IKZF1 deletion in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 2014;28(1):182–185. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clappier E, Auclerc MF, Rapion J, et al. An intragenic ERG deletion is a marker of an oncogenic subtype of B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia with a favorable outcome despite frequent IKZF1 deletions. Leukemia. 2014;28(1):70–77. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martens JHA. Acute myeloid leukemia: a central role for the ETS factor ERG. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2011;43(10):1413–1416. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2011.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen S, Deniz K, Sung YS, Zhang L, Dry S, Antonescu CR. Ewing sarcoma with ERG gene rearrangements: a molecular study focusing on the prevalence of FUS-ERG and common pitfalls in detecting EWSR1-ERG fusions by FISH. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2016;55(4):340–349. doi: 10.1002/gcc.22336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim J, Park TS, Song J, et al. Detection of FUS-ERG chimeric transcript in two cases of acute myeloid leukemia with t(16;21)(p11.2;q22) with unusual characteristics. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2009;194(2):111–118. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weber S, Haferlach C, Jeromin S, et al. Gain of chromosome 21 or amplification of chromosome arm 21q is one mechanism for increased ERG expression in acute myeloid leukemia. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2016;55(2):148–157. doi: 10.1002/gcc.22321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kalna V, Yang Y, Peghaire CR, et al. The transcription factor ERG regulates super-enhancers associated with an endothelial-specific gene expression program. Circ Res. 2019;124(9):1337–1349. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.313788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shah AV, Birdsey GM, Randi AM. Regulation of endothelial homeostasis, vascular development and angiogenesis by the transcription factor ERG. Vascul Pharmacol. 2016;86:3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2016.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sperone A, Dryden NH, Birdsey GM, et al. The transcription factor Erg inhibits vascular inflammation by repressing NF-kappaB activation and proinflammatory gene expression in endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31(1):142–150. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.216473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dufton NP, Peghaire CR, Osuna-Almagro L, et al. Dynamic regulation of canonical TGFβ signalling by endothelial transcription factor ERG protects from liver fibrogenesis. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1):895. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01169-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kissick HT, On ST, Dunn LK, et al. The transcription factor ERG increases expression of neurotransmitter receptors on prostate cancer cells. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:604. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1612-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.García-Perdomo HA, Chaves MJ, Osorio JC, Sanchez A. Association between TMPRSS2:ERG fusion gene and the prostate cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Cent European J Urol. 2018;71(4):410–419. doi: 10.5173/ceju.2018.1752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yin T, Shao M, Sun M, et al. Gastrointestinal Ewing sarcoma: a clinicopathological and molecular genetic analysis of 25 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2024;48(3):275–283. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000002163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang J, McCastlain K, Yoshihara H, et al. Deregulation of DUX4 and ERG in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat Genet. 2016;48(12):1481–1489. doi: 10.1038/ng.3691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Greene D, Pirri D, Frudd K, et al. Genomics England Research Consortium. Genetic association analysis of 77,539 genomes reveals rare disease etiologies. Nat Med. 2023;29(3):679–688. doi: 10.1038/s41591-023-02211-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Feurstein S, Godley LA. Germline ETV6 mutations and predisposition to hematological malignancies. Int J Hematol. 2017;106(2):189–195. doi: 10.1007/s12185-017-2259-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stevenson WS, Rabbolini DJ, Beutler L, et al. Paris-Trousseau thrombocytopenia is phenocopied by the autosomal recessive inheritance of a DNA-binding domain mutation in FLI1. Blood. 2015;126(17):2027–2030. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-06-650887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saultier P, Vidal L, Canault M, et al. Macrothrombocytopenia and dense granule deficiency associated with FLI1 variants: ultrastructural and pathogenic features. Haematologica. 2017;102(6):1006–1016. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2016.153577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martin AR, Williams E, Foulger RE, et al. PanelApp crowdsources expert knowledge to establish consensus diagnostic gene panels. Nat Genet. 2019;51(11):1560–1565. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0528-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hahn CN, Chong CE, Carmichael CL, et al. Heritable GATA2 mutations associated with familial myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia. Nat Genet. 2011;43(10):1012–1017. doi: 10.1038/ng.913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sobreira N, Schiettecatte F, Valle D, Hamosh A. GeneMatcher: a matching tool for connecting investigators with an interest in the same gene. Hum Mutat. 2015;36(10):928–930. doi: 10.1002/humu.22844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Karczewski KJ, Francioli LC, Tiao G, et al. The mutational constraint spectrum quantified from variation in 141,456 humans. Nature. 2020;581(7809):434–443. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2308-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Glembotsky AC, Marin Oyarzún CP, De Luca G, et al. First description of revertant mosaicism in familial platelet disorder with predisposition to acute myelogenous leukemia: correlation with the clinical phenotype. Haematologica. 2020;105(10):e535. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2020.253070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Caulfield M, Davies J, Dennys M, et al. National Genomic Research Library Protocol v5.1; 2017. National Genomic Research Library. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sondka Z, Dhir NB, Carvalho-Silva D, et al. COSMIC: a curated database of somatic variants and clinical data for cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024;52(D1):D1210–D1217. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkad986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Adamo P, Ladomery MR. The oncogene ERG: a key factor in prostate cancer. Oncogene. 2016;35(4):403–414. doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nishii R, Baskin-Doerfler R, Yang W, et al. Molecular basis of ETV6-mediated predisposition to childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2021;137(3):364–373. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020006164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hu W, Philips AS, Kwok JC, Eisbacher M, Chong BH. Identification of nuclear import and export signals within Fli-1: roles of the nuclear import signals in Fli-1-dependent activation of megakaryocyte-specific promoters. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25(8):3087–3108. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.8.3087-3108.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thoms JAI, Birger Y, Foster S, et al. ERG promotes T-acute lymphoblastic leukemia and is transcriptionally regulated in leukemic cells by a stem cell enhancer. Blood. 2011;117(26):7079–7089. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-317990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17(5):405–424. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wiel L, Baakman C, Gilissen D, Veltman JA, Vriend G, Gilissen C. MetaDome: pathogenicity analysis of genetic variants through aggregation of homologous human protein domains. Hum Mutat. 2019;40(8):1030–1038. doi: 10.1002/humu.23798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hayashi Y, Harada Y, Harada H. Myeloid neoplasms and clonal hematopoiesis from the RUNX1 perspective. Leukemia. 2022;36(5):1203–1214. doi: 10.1038/s41375-022-01548-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang MY, Churpek JE, Keel SB, et al. Germline ETV6 mutations in familial thrombocytopenia and hematologic malignancy. Nat Genet. 2015;47(2):180–185. doi: 10.1038/ng.3177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pippucci T, Savoia A, Perrotta S, et al. Mutations in the 5’ UTR of ANKRD26, the ankirin repeat domain 26 gene, cause an autosomal-dominant form of inherited thrombocytopenia, THC2. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88(1):115–120. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ostergaard P, Simpson MA, Connell FC, et al. Mutations in GATA2 cause primary lymphedema associated with a predisposition to acute myeloid leukemia (Emberger syndrome) Nat Genet. 2011;43(10):929–931. doi: 10.1038/ng.923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stockley J, Morgan NV, Bem D, et al. Enrichment of FLI1 and RUNX1 mutations in families with excessive bleeding and platelet dense granule secretion defects. Blood. 2013;122(25):4090–4093. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-06-506873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Di Paola J, Porter CC. ETV6-related thrombocytopenia and leukemia predisposition. Blood. 2019;134(8):663–667. doi: 10.1182/blood.2019852418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McKinney-Freeman S, Hall T. Evaluation of Ranzoni, et al: integrative single-cell RNA-seq and ATAC-seq analysis of human developmental hematopoiesis. Cell Stem Cell. 2021;28(3):357–358. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2021.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Miyazawa H, Wada T. Reversion mosaicism in primary immunodeficiency diseases. Front Immunol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.783022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gutierrez-Rodrigues F, Sahoo SS, Wlodarski MW, Young NS. Somatic mosaicism in inherited bone marrow failure syndromes. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2021;34(2) doi: 10.1016/j.beha.2021.101279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lu J, Wu T, Zhang B, et al. Types of nuclear localization signals and mechanisms of protein import into the nucleus. Cell Commun Signal. 2021;19(1):60. doi: 10.1186/s12964-021-00741-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brown AL, Hahn CN, Scott HS. Secondary leukemia in patients with germline transcription factor mutations (RUNX1, GATA2, CEBPA) Blood. 2020;136(1):24–35. doi: 10.1182/blood.2019000937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dufour A, Schneider F, Metzeler KH, et al. Acute myeloid leukemia with biallelic CEBPA gene mutations and normal karyotype represents a distinct genetic entity associated with a favorable clinical outcome. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(4):570–577. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.6010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Niihori T, Tanoshima R, Sasahara Y, et al. Phenotypic heterogeneity in individuals with MECOM variants in 2 families. Blood Adv. 2022;6(18):5257–5261. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020003812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Venugopal P, Arts P, Fox LC, et al. Unravelling facets of MECOM-associated syndrome: somatic genetic rescue, clonal hematopoiesis and phenotype expansion. Blood Adv. 2024;8(13):3437–3443. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2023012331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Subramanian S, Thoms JAI, Huang Y, et al. Genome-wide transcription factor-binding maps reveal cell-specific changes in the regulatory architecture of human HSPCs. Blood. 2023;142(17):1448–1462. doi: 10.1182/blood.2023021120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Homan CC, Drazer MW, Yu K, et al. Somatic mutational landscape of hereditary hematopoietic malignancies caused by germline variants in RUNX1, GATA2, and DDX41. Blood Adv. 2023;7(20):6092–6107. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2023010045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Antony-Debré I, Duployez N, Bucci M, et al. Somatic mutations associated with leukemic progression of familial platelet disorder with predisposition to acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2016;30(4):999–1002. doi: 10.1038/leu.2015.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sahoo SS, Pastor VB, Goodings C, et al. Clinical evolution, genetic landscape and trajectories of clonal hematopoiesis in SAMD9/SAMD9L syndromes. Nat Med. 2021;27(10):1806–1817. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01511-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.