Abstract

Background

Novel advancements in wearable technologies include continuous measurement of body composition via smart watches. The accuracy and stability of these devices are unknown.

Objectives

This study evaluated smart watches with integrated bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) sensors for their ability to measure and monitor changes in body composition.

Methods

Participants recruited across BMIs received duplicate body composition measures using 2 wearable bioelectrical impedance analysis (W-BIA) model smart watches in sitting and standing positions, and multiple versions of each watch were used to evaluate inter- and intramodel precision. Duplicate laboratory-grade octapolar bioelectrical impedance analysis (8-BIA) and criterion DXA scans were acquired to compare estimates between the watches and laboratory methods. Test-retest precision and least significant changes assessed the ability to monitor changes in body composition.

Results

Of 109 participants recruited, 75 subjects completed the full manufacturer-recommended protocol. No significant differences were observed between W-BIA watches in position or between watch models. Significant fat-free mass (FFM) differences (P < 0.05) were observed between both W-BIA and 8-BIA when compared to DXA, though the systematic biases to the criterion were correctable. No significant difference was observed between the W-BIA and the laboratory-grade BIA technology for FFM (55.3 ± 14.5 kg for W-BIA versus 56.0 ± 13.8 kg for 8-BIA; P > 0.05; Lin’s concordance correlation coefficient = 0.97). FFM was less precise on the watches than DXA {CV, 0.7% [root mean square error (RMSE) = 0.4 kg] versus 1.3% (RMSE = 0.7 kg) for W-BIA}, requiring more repeat measures to equal the same confidence in body composition changes over time as DXA.

Conclusions

After systematic correction, smart-watch BIA devices are capable of stable, reliable, and accurate body composition measurements, with precision comparable to but lower than that of laboratory measures. These devices allow for measurement in environments not accessible to laboratory systems, such as homes, training centers, and geographically remote locations.

Keywords: body composition, dual energy X-ray absorptiometry, bioelectrical impedance, wearable, smart watch, fat-free mass, validation, precision

Introduction

Obesity has increasingly become a global burden and accounts for approximately 60% of cardiovascular disease (CVD) death, while the risks of CVD and cancer mortality increase by 6 and 7%, respectively, with each 2-year period spent with obesity (1, 2). The United States is reported to have the greatest number of adults with obesity and highest proportion of age-standardized children with obesity (1). Considered to be a chronic disease, obesity develops over time as a result of overnutrition and lack of physical activity (3). Weight loss, even at modest levels, early in the progression towards obesity can prevent or reverse the comorbidities associated with excess adiposity (4). These findings prompt the need to identify strategies to support and encourage effective weight management or weight loss to reduce the health burden associated with obesity.

Developing strategies to manage weight reduction and reduce obesity risks are focusing on evidence-based and informed interventions, where individuals actively participate in managing their diet, activity, and subsequent disease risks (3). Wearable technologies provide consumers with continuous access to information to help manage their health on a personal basis, as well as improve the tracking and access to data for physician use (5). For example, self-monitoring of behaviors, particularly through access to data from wearables, improves self-awareness and increases visibility of behavior patterns, which resulted in an increase in physical activity in nearly 60% of users (5). Greater engagement with these self-monitoring tools is associated with increased adherence to target outcomes, including weight loss or body recomposition (5, 6).

Wearable devices have focused on tracking physical activity (steps or heartbeat), sedentary time, sleep quality, and caloric consumption. Preliminary analyses of the benefits of wearables show that use of these trackers improves physical activity more than diet or sleep (7). Specifically, a randomized control trial found that wearables decreased sedentary time by an average of 68 minutes compared to controls, while a meta-analysis of the effects of wearable activity trackers showed an increase of more than 2500 daily steps (8, 9). More recent wearable devices using bioimpedance technology have been developed that are capable of assessing body composition (10, 11). Given the potential of a wearable activity tracker to improve body composition by increasing physical activity, it is of interest to understand the value of an autonomous, wearable, body composition assessment tool in improving diet, physical activity, and body composition (12, 13).

Though wearable technologies show promise for improving the overall health of the user, ex-users of wearables cite questionable accuracy of provided data as a significant driver in the discontinued use of the technology (14). Since wearables offer the opportunity to monitor changes in body composition between medical visits, it is necessary to ensure that these accessible devices provide accurate body composition measures compared to methods commonly used in medical practice. Thus, we sought to explore the accuracy of 2 consumer-grade bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA)–based wearable watches for the assessment of body composition in a young, healthy population as compared to the criterion method, DXA. We further compared the BIA measures on the watches to those from a laboratory-grade BIA device.

Methods

This analysis was a cross-sectional convenience sample of healthy, adult volunteers. We aimed to recruit a diverse sample of 110 adults with equal stratifications by sex, BMI (<18.5, 18.5–24.9, 25–29.9, and ≥30 kg/m2), and geographic location (Baton Rouge, LA, and Honolulu, HI). All participants were recruited between July 2021 and November 2021 using methods including web advertisements, posted flyers, and word of mouth. Participants completed a pre-evaluation screening questionnaire during the recruitment process to ensure good health in order to participate. The primary racial background was self-reported by participants. Prospective participants were excluded if they could not stand for 2 minutes without aid, could not lie supine for 10 minutes without movement, had metal implants, or had significant body shape–altering procedures (e.g., liposuction, amputations, or breast augmentation or reduction). Female participants were also excluded if pregnant or breastfeeding. Participants included in the data set were scanned at the Pennington Biomedical Research Center Metabolism and Body Composition Laboratory or the University of Hawai’i Cancer Center (UHCC) Body Composition Laboratory. Participants were scheduled for arrival at the testing facilities during the mornings (08:00–10:00) following an overnight fast. As a reflection of real-world accuracy of the wearable BIA devices, hydration was not assessed or controlled. The study protocols were approved by institutional review boards at both sites and all participants provided written informed consent.

Anthropometric measurements

Height and mass were measured to the nearest 0.1 cm and 0.1 kg, respectively, using a stadiometer and digital scale combination (Seca 264), with participants wearing lightweight, form-fitting clothes. For height measurement, participants stood barefoot with their backs against the stadiometer with their heels together and touching the wall plate. Participants stood erect with their back and buttocks touching the measurement surface and oriented their head to look straight ahead, with the orbitale-tragion line forming a horizontal line. Weight and height measurements were collected in duplicate and the results were averaged.

Wearable bioelectrical impedance analysis

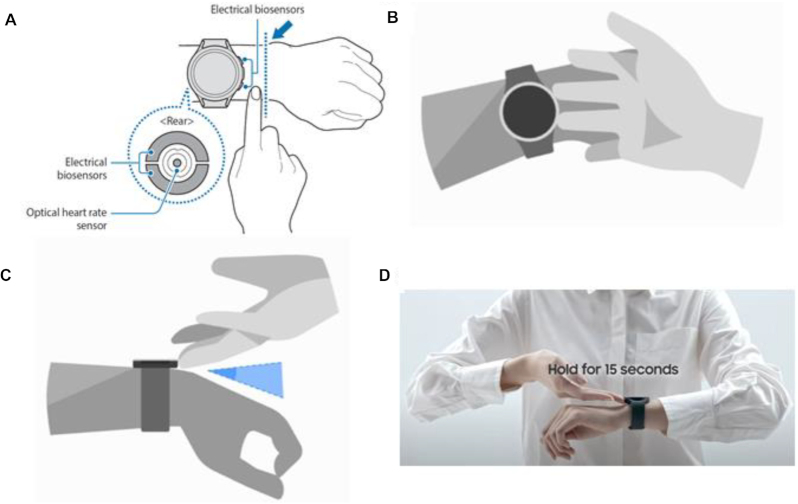

The candidate watches included the Samsung Galaxy Watch 4 and Samsung Galaxy Watch 4 Classic (Samsung Electronics Co., Ltd). Six watches (3 Samsung Galaxy and 3 Samsung Galaxy Classic) were provided to each testing site for evaluations of the real-world inter- and intradevice accuracy and precision. Users placed the device on the left wrist (based on the device configuration and manufacturer recommendations) with the right-hand testing buttons located on the right side of the watch directly above the top of the radius to facilitate a loop connection with the contralateral (right) arm. The wrist strap was tightened to ensure complete electrode contact with the skin on the wrist. Sample images of the proper testing position, finger contacts, and posture are presented in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Samsung watch sensor placement and testing position. (A) Proper alignment of electrodes to wrist; (B) manufacturer-recommended testing position, with 2 fingers of the right hand in contact with the side electrodes; (C) positioning of hands to avoid contact; and (D) recommended testing position.

The wearable bioelectrical impedance analysis (W-BIA) devices use a single 50-kHz frequency electrical current, conducted through the body water located in the fat-free mass (FFM) of the upper body from the left to right arm. It utilizes 4 electrodes, with 2 (chromium silicone carbon nitride) located on the back side of the watch (in contact with the wrist) and 2 (stainless steel) on the buttons on the side of the watch for contact with the right fingers. This allows for a loop for conducting the 50-kHz electrical current to determine impedance of the upper body, with measurements of impedance collected based on the electrical conductivity of the FFM component of the measurement loop. The tetrapolar electrode configuration with separate source electrodes placed outside the detector electrodes reduces the effect of the higher current density at the electrodes, ensuring a uniform current distribution (15).

To overcome the differences in current density based on the proximity of the small-scale electrodes, the watch alters the current and sensing electrodes with each test using an internal analog front-end (AFE) chip capable of swapping the measurement paths (personal communication with manufacturer). The switching matrix diagram of this W-BIA configuration is presented in Supplemental Figure 1. This method allows for compensation of system errors due to interference or “parasitic” resistance (16). The source and current electrodes on the back side of the watch are separated by a distance of 0.5 mm, which is considerably less than the 5-cm distance recommended by the European Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, which will result in an increase in the measured impedance (17, 18). While the small cross-section of the wrist, in addition to the effects of the electrode placement on current flow, will likely result in an increase in measured impedance, accounting for this additional impedance using the AFE chip approach and the prediction algorithm may support the ability to utilize the shorter-distance electrode separation that is becoming common in W-BIA technologies (15, 18, 19). Thus, proprietary, manufacturer-derived algorithms were used to estimate the FFM, fat mass (FM), percent body fat (PBF), total body water (TBW), skeletal muscle mass (SMM), and basal metabolic rate (BMR) based on the height, weight, age, sex, and measured impedance. This method differs from those used in previous handheld (upper-body loop-based) BIA devices in that different algorithms must be modeled to compensate for the contact resistance generated from the small-scale electrodes in use (20, 21).

For each test performed, a random watch of the 6 available devices was selected to assess the accuracy of each device and model. The user ID, height, and weight were entered into the watch in the body composition testing option. Participants were required to sit for 5 minutes to allow for fluid equilibration and normalization of their resting heart rate. Prior to each test, participants raised their arms to chest level and, with their right palm facing upwards, placed the middle and ring fingers of the right hand on the 2 electrodes on the right side of the watch, creating a loop from the left wrist electrodes to those in contact with the right hand. The technician then started the body composition test, which, according to manufacturer recommendations, requires 15 seconds for the measurement to complete properly. Tests were performed in duplicate for test-retest precision, while the first measurement was selected for accuracy testing.

In a subanalysis performed at UHCC to assess accuracy and precision based on the watch (intramodel), model (intermodel), and testing position, data were collected in duplicates in the standing position, the seated position, and seated with repositioning (removing the watch and replacing on the wrist for test number 2), using all 3 sample watches provided for each model (a total of 6 watches, measured in random order). To compare standing to sitting results, participants first completed a single test after standing for 10 minutes using each watch model. Participants were required to sit for 5 minutes prior to completing seated tests. For seated tests, precision was assessed with and without reposition of the watch, resulting in 3 (seated, seated repeat, seated with repositioning) seated tests for each watch model. The aims of these analyses were to identify any precision or body-composition differences associated with different watch testing postures or positions.

Octapolar bioelectrical impedance analysis

A standing bioelectrical impedance analysis was performed using a whole-body segmental multifrequency (1, 5, 50, 250, 500, and 1000 kHz) InBody 770 (InBody), previously shown to have good agreement for body composition measures across BMI categories when compared to DXA (22). The octapolar bioelectrical impedance analysis (8-BIA) technology has also been previously validated for TBW measures as compared to deuterium dilution (23). Prior to each measurement, participants cleaned their hands and feet with manufacturer-provided cleansing wipes. After standing for 10 minutes, participants were instructed to step onto the foot electrodes located on the standing platform. Weight was measured and recorded by the built-in weight scale and height was entered based on the anthropometric assessment. Complete details of the 8-BIA system and testing procedure have been described elsewhere (24). Briefly, participants grasped the handles with the palms and thumbs contacting the electrodes, extending the arms outwards from the torso at an angle of 15° to 45° to ensure no contact between the arms and the torso. Participants remained in the testing position for the duration of the 60-second test. Afterwards, participants stepped off the device and the testing procedure was repeated. The body composition estimates validated included FFM, FM, PBF, SMM, TBW, and BMR.

DXA scans

The primary aim was to validate the accuracy of W-BIA to the criterion body composition method, DXA. As a secondary analysis, the body composition variables from the W-BIA device were compared to both 8-BIA and DXA to determine whether the performance of BIA differed by format (W-BIA to 8-BIA) or technique (BIA to DXA). DXA technology passes calibrated X-ray beams with dual photon energy through the body, with the resulting attenuation being used to discriminate bone mass, fat, and lean soft tissue (25). Each participant completed duplicate whole-body DXA scans on a Hologic Discovery/A system (Hologic Inc.) by a certified DXA radiology technician. DXA scans were analyzed at UHCC by a trained technologist using Hologic Apex version 5.6, with the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Body Composition Analysis calibration option disabled. DXA systems were calibrated according to standard Hologic procedures (26, 27). Participants wore the same form-fitting clothes as used across all assessments. As per International Society for Clinical Densitometry guidelines, offset scanning was performed for subjects too wide to fit in the DXA scan field. Calibration phantoms were shared across sites as part of a previous study protocol to ensure calibration between DXA systems (28). Body composition measurements from DXA included FFM, FM, PBF, and SMM, and these measurements were considered the criterion for the evaluation of accuracy of the W-BIA devices.

Statistical methods

The statistical analysis was performed using SAS version 9.4 for Windows (SAS Institute). Data are expressed as means ± SD. The %CV and root mean square error (RMSE) were calculated for the matched test-retest measurements, when available (29). We first quantified the test-retest precision of all technologies, including the test-retest precision of each Samsung watch on the same location on the wrist while in the seated position. We evaluated for the presence of site bias by including study site as a potential independent variable associated with outcome. As a subsample of the study, in the UHCC participants we assessed the test-retest precision of the watches between standing and sitting measurements (with a 5-minute equilibration period following sitting) and assessed the seated test-retest precision when the watch was removed and immediately placed on the same portion of the wrist. We also assessed the precision between all 6 watches (3 Samsung Galaxy and 3 Samsung Galaxy Classic) in this UHCC subsample.

A Kolmogorov-Smirnov test with Lilliefors-correction and a Shapiro-Wilk test were performed to confirm normal distributions of data. One-way repeated-measures ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc comparisons were performed to examine the relationships between body composition measures with W-BIA compared to those available on 8-BIA and the criterion for body composition (DXA); these included FFM, FM, PBF, and SMM. Paired-sample t-tests were performed to examine the relationships between body composition measures available exclusively on W-BIA and 8-BIA (TBW, BMR). Constant error (CE) between methods was calculated as the mean difference from each alternate method to the criterion (CE = alternate − criterion). Linear regression was performed to compare slopes to the line of identity. Ordinary least squares regression provides correction to the criterion using the assumption that DXA serves as the clinical criterion method and, therefore, has no measurement error. Pearson’s product moment correlation coefficients were assessed based on the scale from Hopkins et al. (30) and categorized as moderate (0.31–0.49), large (0.50–0.69), very large (0.70–0.89), and near perfect (0.90–1.00). Lin’s concordance correlation coefficients (CCC) were calculated to assess accuracy and precision in body composition estimates by W-BIA compared to 8-BIA and DXA and categorized as poor (<0.90), moderate (0.90 to 0.95), substantial (0.95 to 0.99), and almost perfect (>0.99) (31). Bland-Altman analyses were performed to evaluate the agreement and potential bias between methods for all measures of body composition. To evaluate proportional bias, linear regression analysis was performed for each variable, with the mean difference between models as the dependent variable and the mean of the 2 measurements as the independent variable.

We also compared the raw impedance measures between the W-BIA and 8-BIA. Because the measurement loop of the W-BIA (arm-to-arm) differs from that of the 8-BIA (whole-body), we compared the W-BIA impedance to the whole-body impedance, as well as the arm-to-arm impedance, by combining the segmental impedances of the right arm, left arm, and trunk from 8-BIA.

The tests used to describe the accuracy of the W-BIA to 8-BIA and DXA include an ANOVA and t-tests for mean differences, CCC for overall agreement, and Bland-Altman tests for bias and limits of agreement. To compare the percentages of similarity of the 8-BIA and W-BIA to those of the criterion DXA system, we calculated the mean percentage difference (MPD) and %CV (32).

MPD is calculated as follows:

| (1) |

Here, the criterion (DXA) and the estimate (W-BIA and 8-BIA) were entered for each of the available variables of FFM, FM, PBF, and SMM. The calculation of SD across the entire data set allows for the determination of the %CV, which provides a method of comparing results of multiple methods to the criterion (32). The %CV is calculated as follows:

| (2) |

Results

Our recruitment sample included 110 participants. A breakdown of the available data for accuracy and precision analyses are presented in Supplemental Figure 2. One participant was excluded due to a missing DXA scan. For the W-BIA, no significant differences were observed between watch models, the sample used for testing, or assessment site. Of the sample, tests for 34 participants were completed at 10 seconds instead of the manufacturer-recommended 15 seconds required for measurement. This was likely the result of movement by the individual during the test, causing a loss of contact between electrodes that prevented the test from completing. Further examination of the W-BIA data completed at 10 seconds for the FFM variable showed that when compared to the DXA measurement, 9 values exceeded the 95% limits of agreement, while 10 values exceeded the limits of agreement between 8-BIA and W-BIA. The entire data set, including 10- and 15-second measurements, is presented in the Bland-Altman plot in Supplemental Figure 3. Additionally, we removed the 15-second measurements to highlight the error associated with the 10-second measurement time and emphasize the importance of completing the manufacturer-recommended testing time.

Given the inaccuracies noted above with 10-second measurements and to ensure accurate results based on the manufacturer protocol, we report on the results of the sample with complete 15-second measurements; thus, the final analysis included 75 participants (41 female; age, 39.7 ± 16.1 years; height, 167.9 ± 9.2 cm; weight, 81.6 ± 23.9 kg; BMI, 28.7 ± 7.3 kg/m2). Summary characteristics are presented in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Subject characteristics (n = 75; 41 female)1

| Variable | Mean ± SD or n (%) | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 39.7 ± 16.1 | 18.0 | 77.4 |

| Height, cm | 167.9 ± 9.2 | 148.7 | 198.3 |

| Weight, kg | 81.6 ± 23.9 | 38.8 | 147.1 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 28.7 ± 7.3 | 16.6 | 46.4 |

| DXA FFM, kg | 58.7 ± 15.6 | 29.5 | 97.1 |

| DXA FM, kg | 23.0 ± 13.3 | 6.0 | 65.1 |

| DXA PBF, % | 26.9 ± 9.9 | 9.4 | 47.4 |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Asian | 26 (34.7) | — | — |

| NH black | 8 (10.7) | — | — |

| Hispanic | 1 (1.3) | — | — |

| NHOPI | 11 (14.7) | — | — |

| NH white | 29 (38.7) | — | — |

| BMI, kg/m2 | |||

| <18.5 | 5 (6.7) | — | — |

| 18.5–24.9 | 19 (25.3) | — | — |

| 25.0–29.9 | 20 (26.7) | — | — |

| ≥30.0 | 31 (41.3) | — | — |

Percentage values are rounded. Abbreviations: FFM, fat-free mass; FM, fat mass; Max, maximum; Min, minimum; NH, non-Hispanic; NHOPI, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander; PBF, percent body fat.

Test-retest precision analyses in the sitting position were available for 70 participants as a result of incomplete second measurements. There were no precision differences observed (P > 0.05). In the UHCC subsample, a comparison of the body composition estimates included 41 participants with all 3 watches for each W-BIA model, for a total of 246 measurements. Comparisons showed no significant inter- and intra-model precision error differences (all P values > 0.05).

Additionally, no significant differences (all P values > 0.05) were observed between the precision of standing compared with sitting, sitting with repeat, or sitting with repositioning. After confirming there were no differences based on testing position, we combined the results of the 2 watch models and selected the first of the 6 randomized tests taken at UHCC to be used for the final analysis. Then, we combined measurements taken at UHCC with measurements taken at the Pennington Biomedical Research Center (where 1 watch from each model was selected at random for each participant) to obtain the complete data set on 75 participants.

Results of the test-retest precision assessment are presented in Table 2. Comparing FFM precision to DXA (CV, 0.7%; RMSE, 0.4 kg) and 8-BIA (CV, 0.6%; RMSE, 0.3 kg), the precision error on the W-BIA (CV, 1.3%; RMSE, 0.7 kg) was higher, with similar trends observed for FM and PBF. Due to the proportion of incomplete 10-second tests on the W-BIA, it is recommended to ensure the test completes without an error notice being reported on the watch screen. Additionally, the recommendation of duplicate assessments may be warranted to identify potential testing errors.

TABLE 2.

Test-retest precision of body composition measures (n = 70)1

| Variable | W-BIA (Galaxy) | W-BIA (Classic) | 8-BIA | DXA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| %CV | RMSE | %CV | RMSE | %CV | RMSE | %CV | RMSE | |

| FFM, kg | 1.3 | 0.7 | 1.2 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 0.4 |

| FM, kg | 4.7 | 1.2 | 2.4 | 0.6 | 1.3 | 0.3 | 1.7 | 0.4 |

| PBF, % | — | 1.2 | — | 0.7 | — | 0.4 | — | 0.5 |

Abbreviations: 8-BIA, octapolar bioelectrical impedance analysis; FFM, fat-free mass; FM, fat mass; PBF, percent body fat; RMSE, root mean square error; W-BIA, wearable bioelectrical impedance analysis.

Tables 3 and 4 show the means for the measured body composition variables, along with the mean differences, correlations, and Lin’s CCC, for both W-BIA (Table 3) and 8-BIA (Table 4) compared to DXA. Results showed near perfect correlations for both W-BIA and 8-BIA to DXA, though the 3 devices provided statistically significant differences for measures of FFM [F(2148) = 44.8; P < 0.001]. Post hoc comparisons showed significant differences (both P values < 0.001) compared to DXA (58.7 ± 15.6 kg), with mean differences of −3.4 ± 3.2 kg for W-BIA and −2.7 ± 3.3 kg for 8-BIA, though no differences were observed between BIA methods (P = 0.17). A similar trend was observed for FM, with significant differences [F(2148) = 33.4; P < 0.001] between both BIA methods compared to DXA (both P values < 0.001), with no significant difference between W-BIA and 8-BIA (P = 0.14). Statistically significant differences were observed for both PBF [F(2,148) = 42.8; P < 0.001] and SMM [(F(2148) = 211.9; P < 0.001], with post hoc comparisons revealing significant differences between all 3 devices (all P values < 0.001). Despite these differences, the data for all comparisons showed no significant intercept and slopes nearing 1, meaning that the offsets were correctable using the linear regression equation.

TABLE 3.

Assessment of mean differences and agreement of W-BIA and DXA (criterion) by variable (n = 75)1

| Variable | Measurement (mean ± SD) | Constant error (mean ± SD) | Correlation | Agreement | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DXA | W-BIA | Pearson r | CCC (95% CI) | MPD ± SD, % | %CV | ||

| FFM, kg | 58.7 ± 15.6 | 55.3 ± 14.52 | -3.4 ± 3.2 | 0.98 | 0.96 (0.94, 0.97) | 97.2 ± 2.5 | 2.6 |

| FM, kg | 23.0 ± 13.3 | 26.2 ± 13.92 | 3.2 ± 3.3 | 0.97 | 0.96 (0.94, 0.97) | 109.7 ± 11.7 | 10.6 |

| PBF, % | 26.9 ± 9.9 | 30.9 ± 9.32 | 4.0 ± 3.6 | 0.93 | 0.93 (0.90, 0.95) | 109.9 ± 11.5 | 10.5 |

| SMM, kg | 27.2 ± 8.1 | 29.4 ± 8.32 | 2.2 ± 1.7 | 0.98 | 0.87 (0.82, 0.90) | 104.5 ± 3.6 | 3.4 |

Comparisons were made using 1-way repeated measures ANOVA with post hoc group comparisons. Abbreviations: CCC, Lin’s concordance correlation coefficient; FFM, fat-free mass; FM, fat mass; MPD, mean percentage difference; PBF, percent body fat; SMM, skeletal muscle mass; W-BIA, wearable bioelectrical impedance analysis.

Mean value significantly (P < 0.001) differs from DXA.

TABLE 4.

Assessment of mean differences and agreement of 8-BIA and DXA (criterion) by variable (n = 75)1

| Variable | Measurement (mean ± SD) | Constant error (mean ± SD) | Correlation | Agreement | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DXA | 8-BIA | Pearson r | CCC (95% CI) | MPD ± SD, % | %CV | ||

| FFM, kg | 58.7 ± 15.6 | 56.0 ± 13.82 | −2.7 ± 3.3 | 0.98 | 0.96 (0.94, 0.97) | 98.0 ± 2.4 | 2.8 |

| FM, kg | 23.0 ± 13.3 | 25.4 ± 15.92 | 2.4 ± 3.4 | 0.99 | 0.96 (0.94, 0.97) | 104.0 ± 6.9 | 9.7 |

| PBF, % | 26.9 ± 9.9 | 29.3 ± 11.72 | 2.4 ± 3.3 | 0.97 | 0.93 (0.90, 0.95) | 104.2 ± 6.9 | 9.4 |

| SMM, kg | 27.2 ± 8.1 | 31.4 ± 8.32 | 4.2 ± 1.5 | 0.98 | 0.87 (0.82, 0.90) | 108.5 ± 3.2 | 3.0 |

Comparisons were made using 1-way repeated measures ANOVA with post hoc group comparisons. Abbreviations: 8-BIA, octapolar bioelectrical impedance analysis; CCC, Lin’s concordance correlation coefficient; FFM, fat-free mass; FM, fat mass; MPD, mean percentage difference; PBF, percent body fat; SMM, skeletal muscle mass.

Mean value significantly (P < 0.001) differs from DXA.

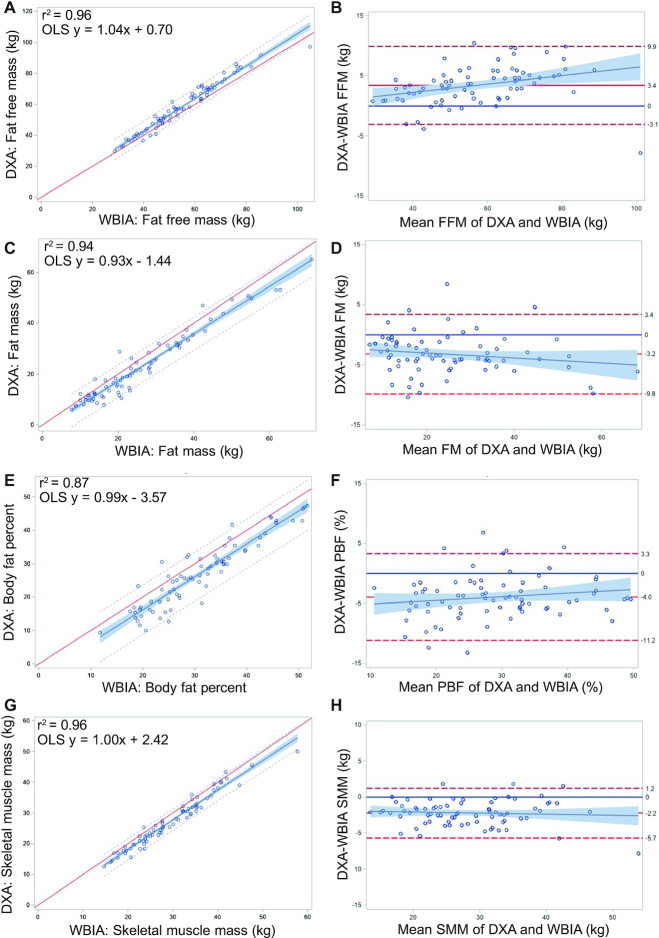

Given the relative agreement between the W-BIA and 8-BIA, the trends observed were relatively similar across comparisons. The underestimation for FFM by both devices showed a significant (P < 0.05) bias across body sizes. No other significant biases were observed for the W-BIA compared to DXA. Despite a higher correlation for FM in the 8-BIA, the trend towards larger FM errors at higher levels of adiposity was not observed in the W-BIA. This error in the 8-BIA FM also resulted in a proportional bias (P < 0.05) in PBF measurements as compared to DXA, depending on the degree of adiposity. Overall, the mean difference for overestimation of SMM for the W-BIA (2.2 ± 1.7 kg) was better than that observed with 8-BIA (4.2 ± 1.5 kg), with no significant bias (P > 0.05) for either device when compared to DXA. When examining the overall agreement of the W-BIA and 8-BIA to DXA, the SD of the MPD showed better agreement for 8-BIA for FFM, FM, and PBF, supporting the greater overall accuracy of the 8-BIA compared to DXA. The overall wide limits of agreement (Figure 2 for the W-BIA and Supplemental Figure 4 for the 8-BIA) observed for both the W-BIA and 8-BIA as compared to DXA indicate that there will be some large individual errors that exist in these comparisons. This is likely the result of the differences in measurement techniques between DXA and BIA, as well as the electrode placement and algorithms used within BIA devices. These findings highlight the importance to physicians of collecting clinical measurements at baseline.

FIGURE 2.

(A, C, E, G) Linear regression and (B, D, F, H) Bland-Altman plots for comparisons of W-BIA to DXA data for (A, B) FFM, (C, D) FM, (E, F) PBF, and (G, H) SMM (n = 75). For linear regression plots, OLS regression lines are solid, with 95% predictions (small dashes) and CIs (shading). Abbreviations: FFM, fat-free mass; FM, fat mass; OLS, ordinary least squares; PBF, percent body fat; SMM, skeletal muscle mass; W-BIA, wearable bioelectrical impedance analysis device.

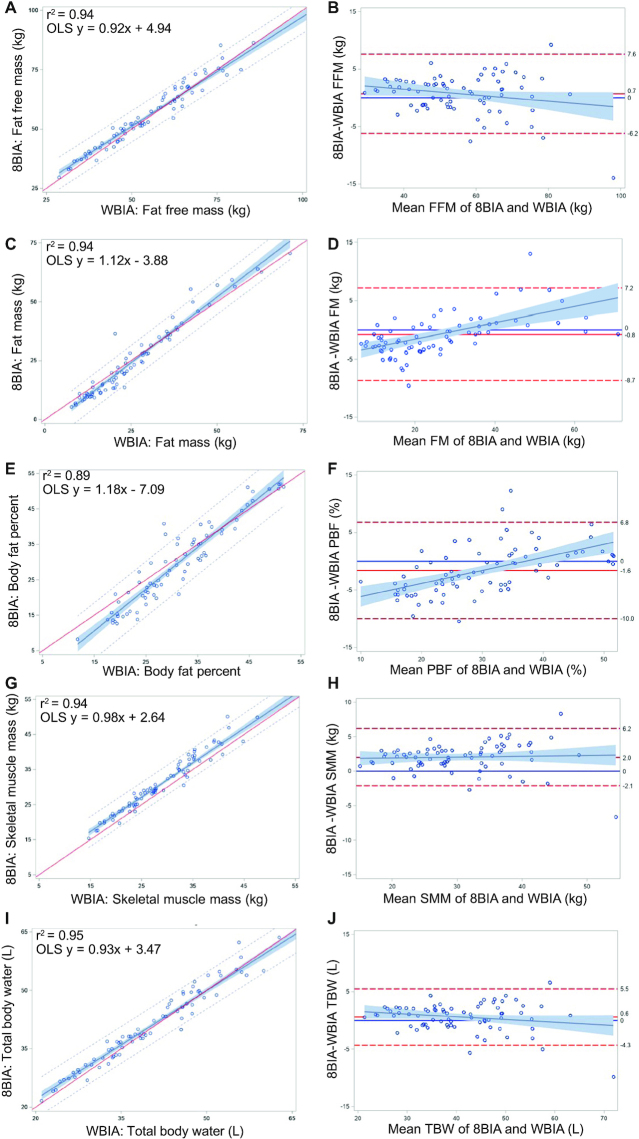

Table 5 shows the means for the measured body composition variables for W-BIA and 8-BIA, as well as the mean differences, correlations, and Lin’s CCC. The W-BIA showed no significant mean differences for FFM, FM, TBW, or BMR; however, mean differences (P < 0.05) were observed for PBF and SMM. The correlations were high for all variables (r > 0.97), with the exception of PBF (r = 0.93), with moderate agreement for PBF and SMM and substantial agreement for FFM, FM, TBW, and BMR. Bland-Altman tests (Figure 3) revealed nonsignificant biases for FFM, SMM, and TBW; however, significant biases were observed for FM and PBF, with greater underestimation of FM (and PBF) at higher levels of adiposity and with underestimation at lower levels of adiposity likely occurring as a result of an incomplete measurement of the trunk, where most fat is stored (33). While the FFM measurements showed a small mean difference (−0.7 ± 3.4 kg) between W-BIA (55.3 ± 13.8 kg) and 8-BIA (56.0 ± 13.8 kg), the wider limits of agreement showed that some individuals exhibit larger errors across the sample.

TABLE 5.

Assessment of mean differences and agreement of W-BIA to 8-BIA by variable (n = 75)1

| Variable | Measurement (mean ± SD) | Difference (mean ± SD) | Correlation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8-BIA | W-BIA | Pearson r | CCC (95% CI) | ||

| FFM, kg | 56.0 ± 13.8 | 55.3 ± 13.8 | −0.7 ± 3.4 | 0.97 | 0.97 (0.95, 0.98) |

| FM, kg | 25.4 ± 15.9 | 26.2 ± 13.9 | 0.8 ± 4.0 | 0.97 | 0.96 (0.95, 0.98) |

| PBF, % | 29.3 ± 11.7 | 30.9 ± 9.32 | 1.6 ± 4.2 | 0.93 | 0.91 (0.87, 0.94) |

| SMM, kg | 31.4 ± 8.3 | 29.4 ± 8.32 | −2.0 ± 2.1 | 0.97 | 0.94 (0.91, 0.96) |

| TBW, L | 41.1 ± 10.2 | 40.5 ± 10.6 | −0.6 ± 2.5 | 0.97 | 0.97 (0.95, 0.98) |

| BMR, cal | 1578.8 ± 298.2 | 1561.6 ± 312.9 | −17.2 ± 74.0 | 0.97 | 0.97 (0.95, 0.98) |

Mean difference comparisons were made using 1-way repeated measures ANOVA with post hoc group comparisons (FFM, FM, PBF, SMM) and dependent-sample t-tests (TBW, BMR). Abbreviations: 8-BIA, octapolar bioelectrical impedance analysis; BMR, basal metabolic rate; cal, calories; CCC, Lin’s concordance correlation coefficient; FFM, fat-free mass; FM, fat mass; PBF, percent body fat; SMM, skeletal muscle mass; TBW, total body water; W-BIA: wearable bioelectrical impedance analysis.

Mean value significantly (P < 0.05) differs from 8-BIA.

FIGURE 3.

(A, C, E, G, I) Linear regression and (B, D, F, H, J) Bland-Altman plots for comparisons of W-BIA to 8-BIA for (A, B) FFM, (C, D) FM, (E, F) PBF, (G, H) SMM, and (I, J) TBW (n = 75). For linear regression plots, OLS regression lines are solid with 95% predictions (small dashes) and CIs (shading). Significant (P < 0.05) biases were observed for (D) FM and (F) PBF. Abbreviations: 8-BIA, octapolar bioelectrical impedance analysis; FFM, fat-free mass; FM, fat mass; OLS, ordinary least squares; PBF, percent body fat; SMM, skeletal muscle mass; TBW, total body water; W-BIA, wearable bioelectrical impedance analysis device.

In Supplemental Figure 5, we present the linear regressions of the raw impedance measures between the W-BIA and 8-BIA devices. We observed overall good agreement between the W-BIA and whole-body 8-BIA (r2 = 0.85). Because the 8-BIA measurement likely includes more of the trunk region than the W-BIA, in addition to the electrode configuration issues noted previously, we observed slightly higher impedance values on the 8-BIA but better agreement to arms and trunk segmental impedance (r2 = 0.89), highlighting the effect that lower-body impedance has on this previously described relationship (11). While it is possible that the effect of the electrode placement and technical configuration could have impacted the precision of the W-BIA, which was larger than the precision of the 8-BIA using the same technology, we were unable to assess this effect in the current study. Regardless, the differences in measured impedance between the BIA devices appear to be overcome using the proprietary algorithm developed by the W-BIA device manufacturer. Thus, while hand-to-hand BIA technologies have previously been problematic in their agreement to criterion assessment methods, the improvements in the technology of the W-BIA devices appear to make them comparable to the 8-BIA technology in our study sample (20, 21, 33).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to assess the precision and accuracy of 2 user-based W-BIA watches for the assessment of body composition in comparison to DXA and a field-based bioimpedance technology (8-BIA) in a sample of healthy adults. Our results show that while the body composition estimations provided by the W-BIA watches were significantly different from those provided by DXA, they were not significantly different from those provided by 8-BIA. The agreement observed between BIA devices supports the conclusion that the lack of agreement to DXA may be the result of the BIA technique as opposed to the format of BIA used. Because BIA measures FFM through proprietary algorithms based on the conductance of electrical currents through TBW, BIA studies have consistently shown individual errors compared to DXA, regardless of the technical advances to these devices (34). That said, the correctable mean differences and high correlations observed between the W-BIA watches and the more expensive commercial and clinical methods support the use of these watches as complimentary tools in between clinical measurements.

Only 1 known prior study has explored a W-BIA device for accuracy in body composition assessments. Manci et al. (10) compared a W-BIA device (InBody Band, InBody) to an 8-BIA device (InBody 720, InBody) and observed no significant differences for FFM, FM, and PBF; however, a significant difference was observed in SMM, as also seen in our study in comparisons to the InBody 770, though the W-BIA had a better agreement for SMM to DXA. The results of our study reflect the strong agreement found between other portable methods developed to assess body composition (11, 35). Prior studies have established the accuracy of 8-BIA compared to DXA in healthy adults across a wide age range, as well as across all BMI categories, although the same finding was not observed in our study (22). While 8-BIA provides significant clinical advantages over W-BIA due to its ability to provide a greater number of outputs, provide segmental measurements, and assess fluid imbalances resulting from edema, the strong agreement between these BIA technologies highlights the value of wearable devices as an adjunct technology (36, 37). Given the relative interchangeability of results between W-BIA and 8-BIA (with slightly better agreement for 8-BIA to DXA), we believe that W-BIA has the potential to improve the precision and accuracy of measurements using this simplified technology and provide a practical body composition measure for the end user (38).

However, this is the first study to examine the accuracy of W-BIA to a clinical assessment method, DXA, which is a well-studied clinical tool capable of predicting metabolic disease and mortality risks, assessing visceral adiposity, and monitoring bone density related to fracture risks (25, 39). The results showed wide limits of agreement for both W-BIA and 8-BIA to DXA, indicating that errors exist for some individuals when comparing to a criterion. That said, we showed that W-BIA could provide relatively accurate complementary data for users to assess changes in body composition between routine medical checkups. An explanation for the differences observed in body composition as measured by the W-BIA compared to DXA is that the wearable bioimpedance technology utilizes a single 50-kHz frequency to estimate TBW based on data from healthy subjects, where deviations from normal physiological parameters (including extreme obesity) can lead to inaccurate estimations of body composition (40). This also highlights the differences between the technologies, with BIA devices being a doubly indirect method of electrical conductivity of body water to predict body composition, with DXA utilizing attenuation of X-rays to quantify bone and soft-tissue composition (25, 40).

Previous studies have shown that the agreement of hand-to-hand BIA measurements shows limited accuracy compared to DXA measurements of body composition (20). Because these BIA devices only measure the upper-body conductivity, regional distributions of fat and muscle, particularly at higher adiposity, likely account for the errors in measurement that occur when compared to whole-body measurement techniques (33). While the use of raw impedance compared to a combination of resistance, reactance, and impedance may also serve as a potential limitation to the accuracy of the device, it appears that this effect may be more likely in cases of disease (41). Additionally, the inclusion of age and gender as prediction variables has been shown to have both advantages and disadvantages in terms of model accuracy (42, 43). Though the manufacturer-recommended test time of 15 seconds is longer than those of previous wearable iterations, the W-BIA in our study showed a strong agreement to the 8-BIA across body sizes, indicating an improvement in this technology (11).

We also found that the precision of measurements was consistent across testing positions. Impedance measures can be influenced by orthostatic fluid shifts related to posture, with this W-BIA method being performed in the seated position likely contributing to small fluid shifts compared to standing or supine measurements (44). Because of the high precision between measurements, some of the error observed in the precision measurements may be the result of “parasitic” resistance, resulting from movement or incomplete electrode contact throughout testing (33, 45).

Given the results of this study, the access to continuous monitoring of body composition provided by a wearable bioimpedance device gives users the opportunity to self-monitor their health and modify their diet and activity behaviors. As individuals become more aware of growing obesity rates, there is an increased desire to monitor body composition by individuals as well as medical professionals. Utilization of this technology has the potential to improve the engagement of users into health and weight-management practices, given that users properly enter their weight when completing assessments (46). Though this potential for error, along with the absolute error derived from these devices, may not provide a perfect comparison to the clinical methods, the ability to monitor these data informs the user of changes that could impact their long-term health risks. Given that wearable technologies provide the opportunity to increase monitoring and feedback regarding changes in body composition, this tool can increase self-awareness and motivation to engage in health-supporting behaviors. Access to data affords users the ability to implement interventions even when clinical testing is not available. This means that users can improve their health monitoring at home (between medical interventions), when traveling, or when working in remote environments where other assessments may not be available (46). Health-care and corporate wellness programs also continue to shift towards personal health management through the use of accessible technologies. Despite their clinical utility, the use of wearable technology continues to be underutilized in the health-care industry (47). With their low cost and convenience, these devices provide the opportunity for self-monitoring and involvement in personal health management. Providing patients with access to personal health-care information has the potential to improve physician-patient relationships, increase patient participation and engagement in healthy behaviors, and improve patient quality of life (47, 48).

Strengths of this study include the large range of age and BMI values in participants recruited for our sample. We also performed a rigorous analysis to assess the test-retest precision both with and without removing the watches between tests, showing the importance of proper measurement and duplication to ensure accurate results. A limitation of this study is that we only recruited a sample of healthy adults; thus, we were unable to assess the accuracy of this technology in individuals with muscle loss or clinical conditions where fluid accumulation occurs, both areas that could cause poorer agreement to DXA. We did not explore the variation in the accuracy of results based on incorrectly input height or weight values. We also did not evaluate the accuracy of the provided standard metabolic rate as opposed to the BMR, though prior work indicates that the accuracy of this estimation is relatively robust (35). The loss of 34 subjects due to completion of a 10-second measurement was also a limitation. With that in mind, we were able to examine the impact of the incomplete tests, and our results highlight the importance of completing the 15-second measurement to ensure accurate body composition estimations. These findings support the importance of proper height and weight measurements, testing times (in the morning, fasted, and postvoid), and test durations to ensure the results of real-world testing reflect those observed in this laboratory validation.

In conclusion, these results show the accuracy of W-BIA devices for the assessment of body composition and highlight the potential utility of using these technologies as part of an autonomous health-management strategy for individuals between medical visits or in situations where remote measurement may be necessary.

Acknowledgments

We thank the study participants for providing their time and participation in this study.

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows—JPB, SBH, and JAS: designed the research, wrote the paper, and have primary responsibility for the final content; JPB, YEL, NNK, MCW, and CM: conducted the research; JPB and BKQ: analyzed the data; and all authors: read and approved the final manuscript.

Data Availability

Deidentified data is available for researchers who meet the criteria for access to confidential data. For details and to request an application, please contact Nisa Kelly, nnkelly@hawaii.edu or visit https://shepherdresearchlab.org/contact/.

Footnotes

Author disclosures: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

This study and equipment were provided by an unrestricted grant from Samsung Electronics Co., Ltd (Seoul, South Korea) to JAS and SBH.

The sponsors had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Supplemental Figures 1–5 are available from the “Supplementary data” link in the online posting of the article and from the same link in the online table of contents at https://academic.oup.com/ajcn/.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

nqac200_sup1

References

- 1.Collaborators GO. Health effects of overweight and obesity in 195 countries over 25 years. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(1):13–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1614362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abdullah A, Wolfe R, Stoelwinder JU, De Courten M, Stevenson C, Walls HL, et al. The number of years lived with obesity and the risk of all-cause and cause-specific mortality. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40(4):985–996. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wharton S, Lau DCW, Vallis M, Sharma AM, Biertho L, Campbell-Scherer D, et al. Obesity in adults: a clinical practice guideline. Can Med Assoc J. 2020;192(31):E875–E891. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.191707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sarma S, Sockalingam S, Dash S. Obesity as a multisystem disease: Trends in obesity rates and obesity-related complications. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2021;23(S1):3–16. doi: 10.1111/dom.14290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dehghan Ghahfarokhi A, Vosadi E, Barzegar H, Saatchian V. The effect of wearable and smartphone applications on physical activity, quality of life, and cardiovascular health outcomes in overweight/obese adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Biol Res Nurs. [accessed 2022 Aug 7]. doi:10.1177/10998004221099556. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Barakat C, Pearson J, Escalante G, Campbell B, De Souza EO. Body recomposition: can trained individuals build muscle and lose fat at the same time? Strength Cond J. 2020;42(5):7–21. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maher C, Ryan J, Ambrosi C, Edney S. Users’ experiences of wearable activity trackers: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):880. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4888-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ellingson LD, Meyer JD, Cook DB. Wearable technology reduces prolonged bouts of sedentary behavior. Transl J Am Coll Sports Med. 2016;1(2):10–17. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ashur C, Cascino TM, Lewis C, Townsend W, Sen A, Pekmezi D, et al. Do wearable activity trackers increase physical activity among cardiac rehabilitation participants? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2021;41(4):249–256. doi: 10.1097/HCR.0000000000000592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manci E, Gumus H, Kayatekin BM. Validity and reliability of the wearable bioelectrical impedance measuring device. J Sports Perform Res. 2019;10(1):44–55. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jung MH, Namkoong K, Lee Y, Koh YJ, Eom K, Jang H, et al. Wrist-wearable bioelectrical impedance analyzer with miniature electrodes for daily obesity management. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):1238. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-79667-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou C, Mo M, Wang Z, Shen J, Chen J, Tang L, et al. A short-term effect of wearable technology-based lifestyle intervention on body composition in stage I–III postoperative breast cancer survivors. Front Oncol. 2020;10:2035. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.563566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nanda S, Hurt RT, Croghan IT, Mundi MS, Gifford SL, Schroeder DR, et al. Improving physical activity and body composition in a medical workplace using brief goal setting. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2019;3(4):495–505. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2019.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nuss K, Li K. Motivation for physical activity and physical activity engagement in current and former wearable fitness tracker users: a mixed-methods examination. Comput Hum Behav. 2021;121:106798. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shiffman C. Adverse effects of near current-electrode placement in non-invasive bio-impedance measurements. Physiol Meas. 2013;34(11):1513. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/34/11/1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chao G, Xiujun L, Meijer GCM. A system-level approach for the design of smart sensor interfaces. In: Rocha D, Sarro PM, Vellekoop MJ, editors. Vienna (Austria): Proceedings of the SENSORS, 2004 IEEE Conference; 2004; 210–4.

- 17.Kyle UG, Bosaeus I, De Lorenzo AD, Deurenberg P, Elia M, Manuel Gómez J, et al. Bioelectrical impedance analysis—Part II: utilization in clinical practice. Clin Nutr. 2004;23(6):1430–1453. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moon JR, Stout JR, Smith AE, Tobkin SE, Lockwood CM, Kendall KL, et al. Reproducibility and validity of bioimpedance spectroscopy for tracking changes in total body water: implications for repeated measurements. Br J Nutr. 2010;104(9):1384–1394. doi: 10.1017/S0007114510002254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Foster KR, Lukaski HC. Whole-body impedance—what does it measure? Am J Clin Nutr. 1996;64(3):388S–396S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/64.3.388S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rockamann RA, Dalton EK, Arabas JL, Jorn L, Mayhew JL. Validity of arm-to-arm BIA devices compared to DXA for estimating % fat in college men and women. Int J Exerc Sci. 2017;10(7):977. doi: 10.70252/VZLA3369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gibson A, Heyward V, Mermier C. Predictive accuracy of Omron body logic analyzer in estimating relative body fat of adults. Int J Sport Nutr Exercise Metab. 2000;10(2):216–227. doi: 10.1123/ijsnem.10.2.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hurt RT, Ebbert JO, Croghan I, Nanda S, Schroeder DR, Teigen LM, et al. The comparison of segmental multifrequency bioelectrical impedance analysis and dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry for estimating fat free mass and percentage body fat in an ambulatory population. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2021;45(6):1231–1238. doi: 10.1002/jpen.1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ng BK, Liu YE, Wang W, Kelly TL, Wilson KE, Schoeller DA, et al. Validation of rapid 4-component body composition assessment with the use of dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry and bioelectrical impedance analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2018;108(4):708–715. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqy158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Esco MR, Snarr RL, Leatherwood MD, Chamberlain NA, Redding ML, Flatt AA, et al. Comparison of total and segmental body composition using DXA and multifrequency bioimpedance in collegiate female athletes. J Strength Cond Res. 2015;29(4):918–925. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000000732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shepherd JA, Ng BK, Sommer MJ, Heymsfield SB. Body composition by DXA. Bone. 2017;104:101–105. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2017.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lu Y, Mathur AK, Blunt BA, Glüer CC, Will AS, Fuerst TP, et al. Dual X-ray absorptiometry quality control: comparison of visual examination and process-control charts. J Bone Miner Res. 1996;11(5):626–637. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650110510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hangartner TN, Warner S, Braillon P, Jankowski L, Shepherd J. The official positions of the International Society for Clinical Densitometry: acquisition of dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry body composition and considerations regarding analysis and repeatability of measures. J Clin Densitom. 2013;16(4):520–536. doi: 10.1016/j.jocd.2013.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bennett JP, Liu YE, Quon BK, Kelly NN, Wong MC, Kennedy SF, et al. Assessment of clinical measures of total and regional body composition from a commercial 3-dimensional optical body scanner. Clin Nutr. 2022;41(1):211–218. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2021.11.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Glüer C-C, Blake G, Lu Y, Blunt B, Jergas M, Genant H. Accurate assessment of precision errors: how to measure the reproducibility of bone densitometry techniques. Osteoporos Int. 1995;5(4):262–270. doi: 10.1007/BF01774016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hopkins W, Marshall S, Batterham A, Hanin J. Progressive statistics for studies in sports medicine and exercise science. Med Sci Sports. 2009;41(1):3. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31818cb278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McBride A. National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research Ltd; Hamilton (New Zealand): 2005. A proposal for strength-of-agreement criteria for Lin’s concordance correlation coefficient. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scott LE, Galpin JS, Glencross DK. Multiple method comparison: statistical model using percentage similarity. Cytometry. 2003;54B(1):46–53. doi: 10.1002/cyto.b.10016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lukaski HC, Siders WA. Validity and accuracy of regional bioelectrical impedance devices to determine whole-body fatness. Nutrition. 2003;19(10):851–857. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(03)00166-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bosy-Westphal A, Schautz B, Later W, Kehayias JJ, Gallagher D, Müller MJ. What makes a BIA equation unique? Validity of eight-electrode multifrequency BIA to estimate body composition in a healthy adult population. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2013;67(S1):S14–S21. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2012.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heymsfield SB, Kim JY, Bhagat YA, Zheng J, Kim I, Choi A et al. Mobile evaluation of human energy balance and weight control: Potential for future developments. In: Angelini ED, Bellazzi R, Besio W, Linguraru MG, editors. Milano (Italy):Proceedings of the 2015 37th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC); 8201–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Jaffrin MY, Morel H. Body fluid volumes measurements by impedance: a review of bioimpedance spectroscopy (BIS) and bioimpedance analysis (BIA) methods. Med Eng Phys. 2008;30(10):1257–1269. doi: 10.1016/j.medengphy.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nescolarde L, Yanguas J, Lukaski H, Alomar X, Rosell-Ferrer J, Rodas G. Localized bioimpedance to assess muscle injury. Physiol Meas. 2013;34(2):237. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/34/2/237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Naranjo-Hernández D, Reina-Tosina J, Min M. Fundamentals, recent advances, and future challenges in bioimpedance devices for healthcare applications. J Sensors. 2019;2019:9210258. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wilson JP, Kanaya AM, Fan B, Shepherd JA. Ratio of trunk to leg volume as a new body shape metric for diabetes and mortality. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e68716. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kyle U. Bioelectrical impedance analysis? Part I: review of principles and methods. Clin Nutr. 2004;23(5):1226–1243. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kyle U, Genton L, Mentha G, Nicod L, Slosman D, Pichard C. Reliable bioelectrical impedance analysis estimate of fat-free mass in liver, lung, and heart transplant patients. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2001;25(2):45–51. doi: 10.1177/014860710102500245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kotler DP, Burastero S, Wang J, Pierson RN. Prediction of body cell mass, fat-free mass, and total body water with bioelectrical impedance analysis: effects of race, sex, and disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 1996;64(3):489S–497S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/64.3.489S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Francisco R, Matias CN, Santos DA, Campa F, Minderico CS, Rocha P, et al. The predictive role of raw bioelectrical impedance parameters in water compartments and fluid distribution assessed by dilution techniques in athletes. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(3):759. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17030759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lozano-Nieto A, Turner AA. Effects of orthostatic fluid shifts on bioelectrical impedance measurements. Biomed Instrum Technol. 2001;35(4):249–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shin S-C, Lee J, Choe S, Yang HI, Min J, Ahn K-Y, et al. Dry electrode-based body fat estimation system with anthropometric data for use in a wearable device. Sensors. 2019;19(9):2177. doi: 10.3390/s19092177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang Y, Fang Y, Xu Y, Xiong P, Zhang J, Yang J, et al. Adherence with blood pressure monitoring wearable device among the elderly with hypertension: the case of rural China. Brain Behav. 2020;10(6):e01599. doi: 10.1002/brb3.1599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Appelboom G, Camacho E, Abraham ME, Bruce SS, Dumont EL, Zacharia BE, et al. Smart wearable body sensors for patient self-assessment and monitoring. Arch Public Health. 2014;72(1):28. doi: 10.1186/2049-3258-72-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Darwish A, Hassanien AE. Wearable and implantable wireless sensor network solutions for healthcare monitoring. Sensors. 2011;11(6):5561–5595. doi: 10.3390/s110605561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

nqac200_sup1

Data Availability Statement

Deidentified data is available for researchers who meet the criteria for access to confidential data. For details and to request an application, please contact Nisa Kelly, nnkelly@hawaii.edu or visit https://shepherdresearchlab.org/contact/.