Abstract

To evaluate the levels of YKL40, IL-6(interleukin-6), IL-8(interleukin-8), IL-10(interleukin-10), TNF-α (tumor necrosis factor-α) in OSAS (obstructive sleep apnea syndrome)children and explore the mechanism of YKL40 promoting inflammatory factors overexpression in tonsils. qPCR and ELISA were used to identify the expression of YKL40, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, and TNF-α in the tonsils of OSAS children. Primary tonsil lymphocytes (PTLCs) were cultured and recombinant human YKL40(rhYKL40)was used to stimulate PTLCs in different concentrations and at different time points. The activation of NF-κB in PTLCs was screened by western blotting. Relative mRNA of YKL40, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α was over expressed in OSAS-derived tonsil tissue and the levels of YKL40, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α was increased in OSAS-derived protein supernatant of tonsil tissue.The relative mRNA expression of IL-6, IL-8 and TNF-α increased under the treatment of YKL40 (100 ng/mmol for 24 h). The phosphorylation of p65 in NF-κB pathway was stimulated in the process. The levels of YKL40, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α increases in OSAS children, and YKL40 promotes the overexpression of IL-6, IL-8 and TNF-α in PTLCs via NF-κB pathway. The result implements that inflammation may play an important role in the pathogenesis of OSAS in children.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-74402-8.

Keywords: Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome, YKL40/ CHI3L1, Inflammatory factors, Interleukin, NF-κB pathway

Subject terms: Medical research, Pathogenesis, Diagnostic markers

Introduction

Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS) is a common disease among children of ages between 2 and 8 years old and has a prevalence ranging from 1.2 to 5.7%. OSAS is characterized by decreased oxygen saturation, hypercapnia, and sleep fragmentation, which inturn results in snoring, daytime sleepiness, poor attention span, hyperactivity, poor school performance, aggressiveness and even it affects the cardiovascular and metabolic systems1,2. The etiology of pediatric OSAS is found to be very complex, in addition to upper airway obstruction which is mainly caused by adenotonsillar hypertrophy (ATH) or other obstructive diseases, chronic persistent mild inflammation has been also considered as the most important contributor to the onset of OSAS and the degree of inflammatory response is correlated with the severity of OSAS3,4.

Increased plasma levels of IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, CRP, IL-9, basic-FGF, and RANTES have been reported in OSAS children. IL-10 level was in dispute in different papers3–7. Studies indicated that adults with OSAS had higher serum YKL40 level and the YKL40 level was correlated with apnea hypopnea index (AHI) or low PaO2value in OSAS adults8–10. From these studies we reasonably infer that there could be a possible relationship between OSAS and YKL40 in which repetitive cycles of hypoxemia/reoxygenation probably induce the synthesis and release of YKL40.So YKL40 may be considered a molecular biomarker for diagnosis and screening of OSAS. Besides, YKL40 is not only an inflammatory factor, but also a proinflammatory factor.

YKL40 could induce inflammatory factors such as IL-8 expression in bronchial epithelium11.

However, serum YKL40 level was estimated only in adults with OSAS. Study has not been reported whether YKL40 can increase and promote other inflammatory factors such as IL-6, IL-8, IL-10,TNF-α increase in children with OSAS. This project focuses on YKL40 and the correlation between YKL40 and these inflammatory factors as well as the possible effect of YKL40 on pediatric OSAS.

Materials and methods

68 children of 4–14 years old who underwent adenotonsillectomy(ATE) for OSAS or primary snoring (PS) were recruited in our hospital from January 2019 till June 2021. The primary inclusion criteria were: (a)Snoring lasted for more than 6 months, and the conservative treatment was ineffective; (b) PSG was performed before operation; (c)No previous history of tonsil and / or adenoidectomy. Exclusion criteria were: (a)acute inflammation or infection; (b) bronchial asthma; (c)immunodeficiency; (d) pulmonary or cardiac diseases; (e) obesity. Screening for overweight and obesity in school-aged children and adolescents was used as the basis for judgment by BMI according to the Health Industry standard of the People’s Republic of China12.

PASS 11 was used to calculate the proper sample sizes and group sample sizes of 9 and 9 achieve 80.659% power to reject the null hypothesis of equalmeans when the population mean difference is µ1 - µ2 = 4.5–0.7 = 3.9 with standard deviations. So the sample size has reached the statistical requirement criteria by statistical calculation.

The diagnosis of OSAS was defined as the obstructive apnea hypopnea index(OAHI) > 1 which has been confirmed by polysomnography(PSG) according to Chinese guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of childhood obstructive sleep apnea13. Primary snoring (PS) was considered in the presence of habitual snoring with OAHI ≤ 1. The size of tonsils was graded from 0 to 4 according to Michael Friedman’ report14. Tonsil size I implies tonsils are hidden within the pillars. Tonsil size II implies the tonsil extending to the pillars. Size III implies tonsils are beyond the pillars but not to the midline. Size IV implies tonsils extend to the midline. Adenoid size was graded from 0 to 4 according to A/N of X-ray15 or fiberendoscopic findings16. A/N: Grade I 0.5–0.6, Grade II 0.61–0.70, Grade III 0.71–0.8 and Grade IV > 0.80. Fiberendoscopic findings: Grade I 0–25%,II 26-50%,III 51-75%, IV 76-100%.

The research was approved by ethical standards of Ethics Committee of our hospital. Study purposes were consented by the participants and their guardians. The children involved in the study were adequately protected and the information disclosure was only done under reasonable request. We confirmed that all experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Reagents and tonsil tissue preparation

RNA simple Total RNA Kits were purchased from ZhongKe XinChuang(TIANGEN DP419,Beijing, China).The AMV First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit)(B532445 ), 2xSG Fast qPCR Master Mix(Low Rox, SYBR, B639272) were purchased from Sangon Biotech(Shanghai, China). ELISA kits of YKL40, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-10 were purchased from Invitrogen and ELISA kits of TNF-α were purchased from Immunoway (Beijing, China) .Recombinant Human YKL40 was purchased from R&D systems (2599-CH-050, Minneapolis, MN, USA). Phospho-NF-κB p65-S536 Rabbit pAb (polyclonal antibody)(P-P65), NF-κB p65 Rabbit mAb (monoclonal antibody) ( P65)and β-actin Rabbit mAb (β-actin )were purchased from ABclonal (Wuhan, China). Antibody of YKL40 was purchased from Abcam(Cambridge, MA, USA). NF-κB activator (N-3-oxo-dodecanoyl-L-Homoserine,3-oxo-C12-HSL, 3-oxo) and NF-κB inhibitor (Bay 11-7082, Bay) was purchased from APExBIO (Houston, TX, USA). Fetal Bovine serum (FBS)and Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 medium were purchased from Gibco(Invitrogen, CA, USA). RIPA Lysis Buffer was purchased from Ecotop Scientific (Guangzhou, China)0.100× Protease Inhibitor Cocktail was purchased from Sangon Biotech(Shanghai, China). All primers (Table 1) were designed and synthesized by Sangon Biotech( Shanghai, China).

Table 1.

Sequences of PCR primers and size of amplicons.

| Primer | Sequence | Size(bp) |

|---|---|---|

| YKL40 | FORWARD CTTTCCTGGTCGTCGTATCCTA | 81 |

| REVERSE CACAGTCCATAGAATCCTCGG | ||

| IL-6 | FORWARD GGTGTTGCCTGCTGCCTTCC | 95 |

| REVERSE GTTCTGAAGAGGTGAGTGGCTGTC | ||

| Il-8 | FORWARD AACTGAGAGTGATTGAGAGTGG | 147 |

| REVERSE ATGAATTCTCAGCCCTCTTCAA | ||

| IL-10 | FORWARD GCCAAGCCTTGTCTGAGATGATCC | 82 |

| REVERSE GCCTTGATGTCTGGGTCTTGGTTC | ||

| TNF-α | FORWARD TGGCGTGGAGCTGAGAGATAACC | 134 |

| REVERSE CGATGCGGCTGATGGTGTGG | ||

| β-actin | FORWARD GGCCAACCGCGAGAAGATGAC | 138 |

| REVERSE GGATAGCACAGCCTGGATAGCAAC |

Tonsil tissues of the enrolled children were removed by otorhinolaryngologic surgeons according to the standard operation. Tissues that were not required for pathologic diagnosis were collected and the capsules were separated.Tonsil tissues were divided into three parts separately for protein extraction, RNA extraction and cell culture.Two parts of approximately100mg tissues for protein and RNA extraction were cleaned by aicy phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and immediately delivered to laboratory with two labeled sterile enzyme-free frozen storage tubes in liquid nitrogen. Another portion of tonsil lymphoid tissue was cut into small pieces and washed with icy phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) plus 100×Penicillin-Streptomycin solution and immediately delivered in the solution to the laboratory within 10 min for cell culture.

ELISA in protein samples of tonsil tissues

Tonsil lymphatic tissue of 100 mg was prepared and triturated in liquid nitrogen, then 1 ml RIPA lysis buffer with PMSF and 100× Protease Inhibitor Cocktail(100:1) was added. The homogenized tissue mixture was placed on ice for 30 min and then in centrifuge at 4℃,12,000 rpm for 15 min. Protein of tonsil tissues was found in the supernatant. Protein concentration was determined using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay (Biosharp, China). The supernatant of tonsil tissue protein was collected and the concentrations of inflammatory mediators were determined by ELISA kits according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The sensitivity of YKL40, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, and TNF-α were 10.83 pg/ml,0.92 pg/ml, ≤ 5 pg/ml,1.0% pg/ml, and 2.3 pg/ml respectively. Optical density at 450 nm was determined using an Auto-Reader Model (SpectraMax i3x, MD, CA).

Real-time PCR of tonsil tissues

Tonsil lymphatic tissues of 100 mg was prepared and homogenized with 1 ml lysate RZ using a homogenizer and the samples were placed at 15–30℃ for 5 min for complete separation of the nucleic acid protein complex. Then total RNA was extracted according to RNA simple Total RNA Kit. Total RNA was diluted 5 times by ddH2O and the concentration was measured for three times. The RNA concentration was the average value of 3 times measured concentration, and the total RNA concentration was adjusted at 1 µg /µl. 1 µl (1 µg) total RNA was used for synthesizing the cDNA using the AMV First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit. The reaction was 42℃ 45 min,85℃ 5 min,4℃. The cDNA products were diluted to 60 µl with ddH2O 0.1 µl (16.7 µg) cDNA (concentration of cDNA < 20ng 20 µl rxn)was used for the real-time PCR reaction using 2xSG Fast qPCR Master Mix. The PCR reaction parameters were 95℃ 3 min, followed by 40 cycles at 95℃ 3 S,60℃ 30 S, then 95℃ 15 S, 60℃ 30 S, 95℃ 1s on a Thermo ScientificTM, ABI QuantStudio 5 (ABI Applied Biosystems). Β-actin was used as an internal control. The mRNA expression of genes was normalized to β-actin and expressed as relative fold of change using the formula of 2 −△△ Ct.

Primary tonsil lymphocyte culture

Lymphoid tissues for cell culture were immediately delivered to the laboratory within 10 min. The dissected tissue pieces were placed into a 6 cm petri dish with sterile, icy PBS plus 100× Penicillin-Streptomycin solution, and then dissociated by grinding the tissue through the sieve with a syringe plunge and transferred the contents into a 70 μm cell strainer. The suspension was pelleted (1,500 rpm for 5 min) and then the supernatant was abandoned. Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100× Penicillin-Streptomycin was added to suspend tonsil lymphocytes. The tonsil lymphocyte suspension was transferred into four 6-round well plates and 4/6 wells of each plate were divided into Control, 10ng/ml-YKL40,100ng/ml- YKL40,1000ng- YKL40 groups. In a 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C for 6 H,12 H ,24 H,48 H, the supernatant and cells were respectively collected after centrifugation in different groups.

Reagent experiments

To investigate the effect of rhYKL40 on PTLCs, PTLCs were incubated with a range of rhYKL40 concentrations for various periods of time. After centrifugation, PTLCs of different treatment groups were respectively collected. Total RNA of PTLCs was isolated using RNA simple Total RNA Kit. Then the RNA concentration was qualified using nanodrop. The optical density (OD) 260/280 = 1.9-2.0 indicated that the RNA purity was high. The total RNA concentration was adjusted at 500 µg/µl. 1 µl (500 µg) total RNA was used for synthesizing the cDNA using the AMV First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit. The reaction was 42℃ 45 min,85℃ 5 min,4℃. The cDNA products were diluted to 40 µl with sterilized ddH2O.1 µl (12.5 µg) cDNA was used for the real-time PCR reaction using 2xSG Fast qPCR Master Mix. Primers and PCR operation were according to 1.2.

Real-time PCR of PTLCs

PTLCs were collected and total RNA was extracted after 24 H treatment of control, 100ng/ml- YKL40, NF-κB activator(3-oxo), and NF-κB inhibitor (Bay 11-7082). All primers were shown in Table 1.The cDNA synthesis, PCR reaction and mRNA expression of genes were operated according to 1.2.

Western blotting

To investigate NF-κB activation of rhYKL40 in PTLCs, the cultures of PTLCs were divided into four groups: Control (YKL40 0ng/ml), YKL40 (rhYKL40 ,100ng/ml), NF-κB activator (N-3-oxo-dodecanoyl-L-Homoserine lactone)100 µM, pretreated for 1 h and then exposed to 100ng/ml rhYKL40)or NF-κB inhibitor(Bay 11-7082,5µM, pretreated for 1 h and then exposed to 100ng/ml rhYKL40) for 48 H.

The cells were collected and then the protein of cells was extracted in RIPA lysis buffer with PMSF and 100× Protease Inhibitor Cocktail. Cell protein concentration was measured using BCA protein assay. The protein concentration of each sample was adjusted to 2 µg/µl. 5× SDS-PAGE Sample Loading Buffer was added to the protein samples and stored in -20℃.

10 µl protein samples were equally loaded on 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel (SDS-PAGE) and the gel which contained the target protein according to the molecular weight of marker was cut into 1.5 to 2 cm width and then transferred onto the same width 0.22 μm polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane (Millipore). After blocking with 5% nonfat milk in TBST for 60 min, the membranes were incubated with primary antibodies against p65, p-p65 (1:1000 dilution), and β-actin (1:2000 dilution) overnight at 4˚C. This was followed by the addition of secondary antibodies conjugated with HRP(Ab clonal,1:5000 dilution) at 37 ˚C for 60 min. Detection was visualized using an ECL assay kit (Biosharp life sciences). The phosphorylation levels of P65 were analyzed with the NIH ImageJ program and were expressed as fold changes compared to the levels of β-actin.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses and data visualization were performed in GraphPad Prism (version 7). Data was reported as mean ± standard deviation or Median ± IQR (Inter quartile range). T test was used to determine the statistical significance of two groups. Shapiro-Wilk normality test was used to test the normality. Mann-Whitney U Test was used to analyze significant differences between skew distribution groups. Chi-square was used to evaluate the rates between two groups. Tukey’s honestly significant difference test was used to analyze significant differences between pairs of groups. Spearman coefficient was used to analyze the correlation between the relative expression of YKL40 and IL-6,IL-8,IL-10, and TNF-α. P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographic characteristics of children with primary snoring and OSAS

68 children who underwent tonsillectomy for Primary Snoring or OSAS were recruited for this study. Demographic characteristics and major parameters of PSG are presented in Table 2. There were no significant differences in age, sex, body mass index, and adenoids’size. Significant differences were found in OAHI, lowest oxyhemoglobin saturation, and tonsils’ size between the two groups. (Table 2)

Table 2.

Demographic Characteristics of Children with PS and OSAS.

| Characteristic | PS | OSAS | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| N=22 | N=46 | ||

| Age, years | 6.23±3.90 | 6.93±3.28 | 0.45 |

| Male No(%) | 14(64%) | 32(70%) | 0.62 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 18.17±5.79 | 18.65±5.08 | 0.42 |

| OAHI/hr | 0.42±0.41 | 4.50±5.35 | 0.000 |

| LoSpO2% | 91.82±2.82 | 88.17±5.91 | 0.007 |

| Tonsils’size(%) | ≥III (13.6%) | ≥III (39.1%) | 0.03 |

| Adenoid’size(%) | ≥III (81.8%) | ≥III (80.4%) | 0.89 |

OAHI:obstructive apnea/hypopnea index; LoSpO2%:lowest oxyhemoglobin saturation by pulse oximetry; BMI: body mass index.

-

1.1

The levels of inflammatory mediators in tissue supernatant of tonsils in children with PS and OSAS by ELISA assay.

Table 3 shows the levels of YKL40, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α in the tonsils of children. Mann-Whitney U Test was used to analyze significant differences between groups.The levels of YKL40, IL-6,IL-8, and TNF-α in the tonsils of children were higher in OSAS than in PS group( P < 0.05). The levels of IL-10 had no significant difference between PS and OSAS groups(P = 0.383).

Table 3.

Levels of inflammatory mediators in the tonsils of children with PS and OSAS, expressed in pg/ml(ELISA).

| Mediators | Levels in tonsils supernatant | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PS group | OSAS group | ||||

| Median | IQR | Median | IQR | ||

| YKL40 | 90.82 | 4.31 | 94.36 | 8.13 | 0.008 |

| IL-6 | 285.79 | 357.06 | 739.525 | 1799.64 | 0.011 |

| IL-8 | 4025.40 | 4866.71 | 8561.83 | 17339.09 | 0.044 |

| IL-10 | 29.82 | 33.29 | 50.90 | 217.20 | 0.383 |

| TNF-α | 532.75 | 2699.12 | 3706.82 | 20583.95 | 0.020 |

PS, primary snoring; OSAS, obstructive sleep apnea syndrome; IL, interleukin; TNF, tumor necrosis factor, pg/mL, picogram per milliliter;IQR (Inter quartile range).

-

1.2

The mRNA of YKL 40, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α Overexpressed in Tonsils of Children with OSAS.

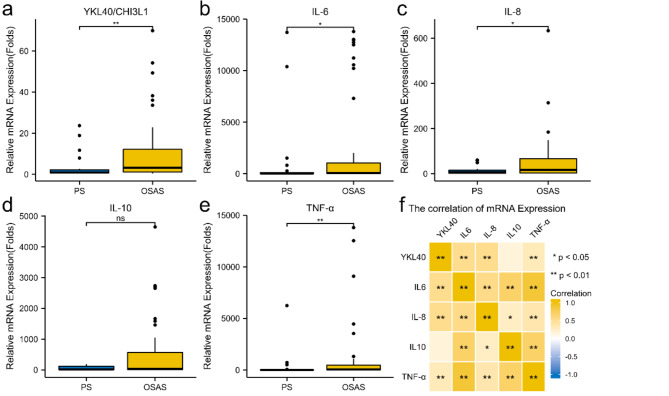

The relative mRNA expressions of YKL40, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α were higher in OSAS group. Significant difference(P < 0.05) was noted between the two groups (Fig. 1a, b, c and e). There was no significant difference in the relative mRNA expression of IL-10 between the two groups (Fig. 1d). The correlation of these inflammatory factors’ mRNA expression was shown in Fig. 1f. Significant correlation was noted between YKL40 and IL-6, YKL40 and IL-8, YKL40 and TNF-α(**P < 0.01). There was no correlation between the mRNA expression of YKL40 and IL-10.

Fig. 1.

Relative mRNA expression and the correlations of inflammatory mediators. a Relative mRNA expression of YKL40 in PS and OSAS groups (**P < 0.01). b Relative mRNA expression of IL-6 in PS and OSAS groups (* P < 0.05), c Relative mRNA expression of IL-8 in PS and OSAS groups (* P < 0.05) d Relative mRNA expression of IL-10 in PS and OSAS groups (ns P > 0.05) e Relative mRNA expression of TNF-α in PS and OSAS group (**P < 0.01). f Correlations among the inflammatory factors(* P < 0.05,**P < 0.01).

-

2.

YKL40 may induce mRNA overexpression of IL-6,IL-8 and TNF-α in a dose- and time-dependent manner.

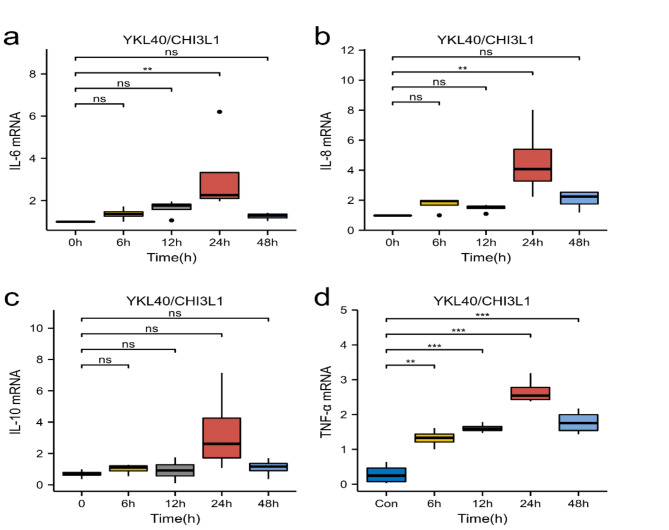

Real-time PCR was performed to examine the effect of YKL40 on the relative mRNA expression of IL-6,IL-8,IL-10, and TNF-α in PTLCs. The cells were stimulated with different concentrations of rhYKL40 for different time points. Inflammatory factors in PTLCs could be stimulated with rhYKL40 in a concentration and time-dependent condition. The relative mRNA expression of IL-6,IL-8,IL-10, and TNF-α in PTLCs reached a peak at a time point of 24 h (Fig. 2). The relative mRNA expression of IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α was higher at 24 h than control(0 h) and a significant difference was noted (**P < 0.01, Fig. 2a, b,d). The relative mRNA expression of IL-10 was higher at 24 h than control(0 h), but no significant difference was noted(ns, Fig. 2c).

Fig. 2.

The effect of YKL40/CHI3L1 with different time points on IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, and TNF-α mRNA in PTLCs. PTLCs were stimulated with rhYKL40 (100 ng/ml) at different time points as indicated. YKL40 stimulated the expression of IL-6 mRNA(a), IL-8 mRNA (b), IL-10 mRNA (c) and TNF-α mRNA (d) (**P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ns-P > 0.05).

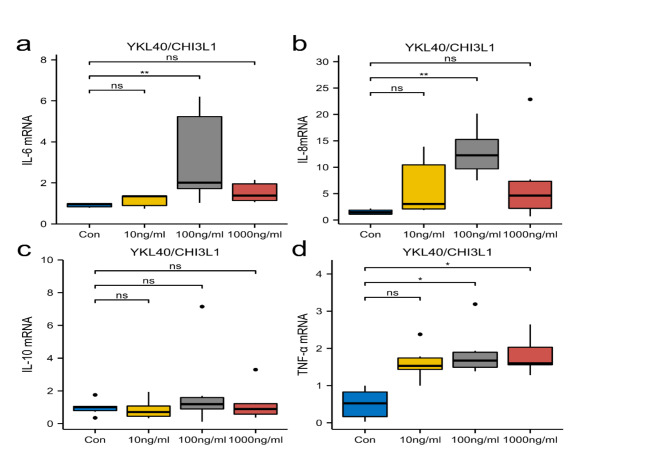

The relative mRNA expression of IL-6 and IL-8 was higher than control when the concentration was increased to 100 ng/ml and significant difference was noted (IL-6**P < 0.01, Fig. 3a, IL-8**P < 0.01, Fig. 3b). The relative mRNA expression of IL-10 was higher at 100 ng/ml YKL40 concentration, but no significant difference was noted(ns, Fig. 3c). The relative mRNA expression of TNF-α was higher at YKL40 concentration of 100 ng/ml and reached its peak at a concentration of 1000 ng/ml(*P < 0.05, Fig. 3d).

Fig. 3.

The effect of YKL40/CHI3L1 with different concentrations on IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, and TNF-α mRNA expression in PTLCs. PTLCs were stimulated with rhYKL40 (24 H) at various concentrations as indicated. YKL40 stimulated the expression of IL-6 mRNA(a), IL-8 mRNA (b), IL-10 mRNA (c), and TNF-α mRNA (d) in PTLCs.(* P < 0.05,**P < 0.01, ns-P > 0.05).

-

3.

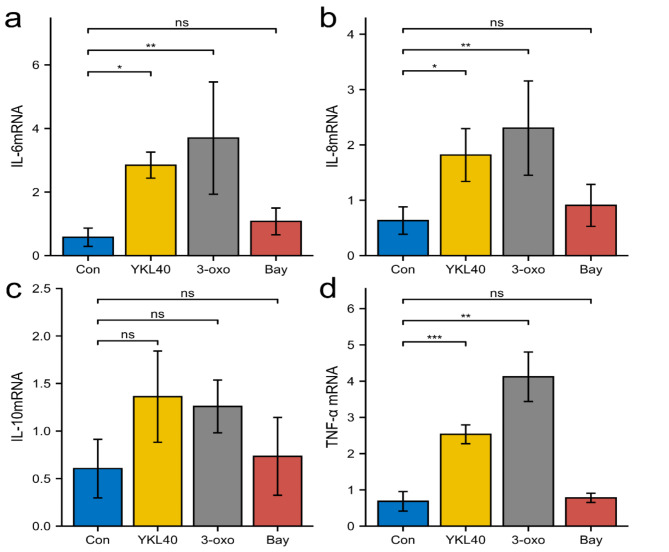

NF-κB pathway may be involved in YKL40 regulating IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α mRNA expression

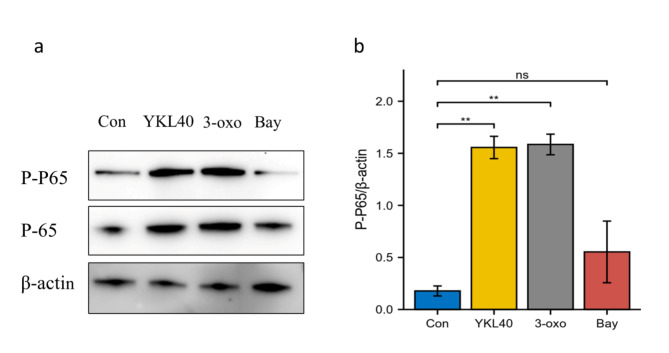

By western blotting, we found that rhYKL40 induced the phosphorylation of P65 in NF-κB pathway. rhYKL40(100ng/ml) stimulated the phosphorylation of P65 and NF-κB activator (3-oxo100uM), a positive control, stimulated the phosphorylation of P65 (Fig. 4a and b, *P < 0.05). NF-κB inhibitor (Bay) blocked the phosphorylation of P65, and there was no significant difference between the NF-κB inhibitor group and the control group by Dunn’s test (Fig. 4a and b, ns P > 0.05).

Fig. 4.

Involvement of p65 phosphorylation in PTLCs. a. Representative P-P65, P65 and β-actin blots in Con, rhYKL40, 3-oxo, Bay groups. b. Statistical plots between the four groups. The quantification of phosphorylated P65 was normalized by β-actin blots.(n = 6, ns P > 0.05,* P < 0.05,**P < 0.01).

To verify the involvement of the NF-κB pathway in rhYKL40 mediating IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, and TNF-α production, PTLCs were treated respectively with rhYKL40(100ng/ml), 3-oxo, Bay 11-7082. The result showed that treatment of PTLCs with rhYKL40 and 3-oxo caused a significant overexpression of IL-6,IL-8 and TNF-α mRNA (Fig. 5a, b,d). The stimulating effect of rhYKL40 on IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, and TNF-α mRNA were prominently offsetted by the NF-κB inhibitor (Bay), but there was no statistical difference between the inhibitor group and the control group (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, TNF-α mRNA relative expression in different treatment of PTLCs. MRNA relative expression in Con(Control), rhYKL40, 3-oxo and Bay. IL-6 mRNA(a), IL-8 mRNA (b), IL-10 mRNA(c), TNF-α mRNA (d) ( ns, P > 0.05, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001).

Discussion

Pediatric OSAS constitutes chronic and low-grade systemic inflammatory disease3.Besides, there is a local inflammatory microenvironment in pediatric OSAS. Goldbart AD reported that LT1-R and LT2-R were overexpressed in pediatric tonsillar tissue of OSAS17. Kim J found that childhood OSAS had higher cytokine concentration and mRNA expression of IL-6, IL-1α and TNF-α in tonsillar cells18.Vitor Guo Chen Li et al.found higher levels of IL-8 and IL-10 in palatine tonsils of pediatric OSAS19.

YKL40 is a special inflammatory factor consisting of 383 amino acids with a molecular weight of 40kDa20. YKL40 has been reported to have an association with inflammatory airway diseases, such as severe asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)21. YKL40 could interact with other inflammatory cytokines and regulate each other22–24.Injuries such as hypoxia may lead to elevated YKL408, and the relation between hypoxia and inflammation has been reported in previous researches25,26. In the previous study, we found there was higher YKL40 in the palatine tonsils of children with OSAS by IHC, qPCR and western blotting27.

In this study we found higher concentration of YKL40 and IL-6,IL-8,TNF-α in OSAS-derived tonsil protein supernatant as well as mRNA overexpression of YKL40, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α in OSAS-derived tonsil tissue. Moreover, we demonstrated a strong correlation between the YKL40 and IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α mRNA expression. IL-6 was strongly associated with IL-8 and TNF-α,and TNF-α was strongly associated with YKL40, IL-6, IL-8 and IL-10. The relation between YKL40 and IL-6, TNF-α was consistent with Caiqun Chen ’s findings in primary Sjögren’s syndrome28. But the relation between YKL40 and TNF-α was inconsistent with the research in CSF of anti-NMDAR encephalitis patients29. So the inconsistent association of inflammatory mediators may be due to OSAS which is comorbid with some upper airway inflammation disease.

To further clarify the relationship of YKL40 and IL-6, IL-8, IL-10,TNF-α, the rhYKL40 was used to treat PTLCs. We found rhYKL40 may induce IL-6, IL-8 and TNF-α mRNA overexpression in a dose- and time-dependent manners. The concentration of 100 ng/ml rhYKL40 was the most effective dose to stimulate the overexpression of IL-6 and IL-8. The relative expression of TNF-α mRNA was peaked at 1000ng/ml and expression of TNF-α was gradually increased in a dose-dependent trend in this research. We also found IL-6, IL-8 and TNF-α mRNA expressions were at peak time of 24 h. The peak time of rhYKL40 on these cytokines was consistent with Hao Tang’s result11. But the peak concentration was different from Hao Tang’s research. Different cell lines may cause different peak concentration of YKL40 on cytokines. Further experiments are needed to explore the relation among these proinflammatory cytokines in vitro and in vivo.

In mechanistic research, we found rhYKL40 induced phosphorylation of p65 in PTLCs. P65 phosphorylation could be stimulated by NF-κB activator and be strongly blocked by NF-κB inhibitor.

The NF-κB family of transcription factors plays a pivotal role in regulating cell and tissue inflammatory responses and the activation is induced under chronic hypoxia. Different molecules of the NF-κB signaling pathway are activated in different pathological processes. Lee P. Israel observed substantial overexpression of two classic NF-κB pathway subunits, p65 and p50, in the germinal centers of tonsils and adenoids from children with OSAS30. In inflammatory processes, signaling pathways may be stimulated depending on YKL40 and its receptor binding pattern23,31. Phosphorylated P65 into the nucleus exerts a pro-inflammatory effect and is associated with activation of the pro-inflammatory factor TNF-a and lower p-NF-κB p65 significantly decreased in the concentrations of TNF-a, iNOS, IL-632. Although the detection of phosphorylation of P65 or P50 indicates that NF-κB participates in YKL40 regulating the secretion of inflammatory factors, phosphorylation of P65 is the most commonly used in experiments. we selected phosphorylation of p65 in our experiment, but its receptor binding patterns involved in the process would be explored in the future.

In the experiment we also found phosphorylation of p65 mediated IL-6, IL-8 and TNF-α expression in PTLCs stimulated with rhYKL40. The procedure was strengthened by NF-κB activator and strongly blocked by NF-κB inhibitor.IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α are the downstream inflammatory cytokines of NF-κB pathway. This could explain the regulation of IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α by phosphorylation of p6533,34.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we first found that YKL40, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α significantly increased in tonsils of pediatric OSAS, and YKL40 could stimulate IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, TNF-α overexpression in PTLCs via NF-κB signaling pathways. Investigation of novel therapeutic strategies targeting YKL40 or NF-κB might open a new avenue for the treatment of pediatric OSAS in future. The limitation of this study would be the difficulty to complete the lymphocyte overexpression and knockdown vector construction, thus the direct mechanism of YKL40 stimulating inflammatory factors overexpression hasn’t been expounded. Further studies should be explored in the future.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Authors sincerely thank Zeng Wang, Ruiqing Chen, Jinan Lin, Junying Chen, Lengxi Fu, Yu peng Chen centralab and pathology department of the First Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University, for their kindness of experimental technical guidance. We also thank our colleagues Xiaohong Lin sleep laboratory for her assistance of PSG examination.

Author contributions

Sheng-nan Ye, Guo-hao Chen and Chang Lin designed the research. Ying-ge Wang and Min Huang collected the case data and the specimens. Ying-ge Wang performed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. Guo-hao Chen, Xiu-ling Fang interpreted the data.Ying-ge Wang and Sheng-nan Ye revised the manuscript and all of authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

The manuscript is under the Funding support of Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province (No.2021J01210).

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical standards

The research was approved by Ethics Committee of of the First Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University (IEC-FOM-013-2.0).

Informed consent

Approval No was MRCTA.ECFAH of FMU[2019]250. Informed consent was obtained from all participants and their guardians.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Guo-hao Chen, Email: 13705919709@163.com.

Sheng-nan Ye, Email: Yeshengnan63@qq.com.

References

- 1.Marcus, C. L. et al. American Academy of, Diagnosis and management of childhood obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Pediatrics130(3), 576–584 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Section on Pediatric Pulmonology, Subcommittee on Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome. Clinical practice guideline: Diagnosis and management of childhood obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Pediatrics109(4), 704–712 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gozal, D., Serpero, L. D., Sans Capdevila, O. & Kheirandish-Gozal, L. Systemic inflammation in non-obese children with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep. Med.9(3), 254–259 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li AM, Lam HS, Chan MH, So HK, Ng SK, Chan IH, Lam CW, Wing YK. Inflammatory cytokines and Childhood Obstructive Sleep Apnoea. Ann. Acad. Med. Singap.37, 649–654 (2008). [PubMed]

- 5.Goldbart, A. D. & Tal, A. Inflammation and sleep disordered breathing in children: A state-of-the-art review. Pediatr. Pulmonol.43(12), 1151–1160 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ke, D. et al. Enhanced interleukin-8 production in mononuclear cells in severe pediatric obstructive sleep apnea. Allergy Asthma Clin. Immunol.15, 23 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chuang, H. H. et al. Relationships among and Predictive Values of Obesity, inflammation markers, and Disease Severity in Pediatric patients with Obstructive Sleep Apnea before and after Adenotonsillectomy. J. Clin. Med.9(2) (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Li, W., Yu, Z. & Jiang, C. Association of serum YKL-40 with the presence and severity of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Lab. Med.45(3), 220–225 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mutlu, L. C., Tülübaş, F., Alp, R., Kaplan, G., Yildiz, Z. D. & Gürel, A. Serum YKL-40 level is correlated with apnea hypopnea index in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci.21, 4161–4166 (2017). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang, Y., Su, X., Pan, P. & Hu, C. The serum YKL-40 level is a potential biomarker for OSAHS: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep. Breath.24(3), 923–929 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tang, H. et al. YKL-40 induces IL-8 expression from bronchial epithelium via MAPK (JNK and ERK) and NF-kappaB pathways, causing bronchial smooth muscle proliferation and migration. J. Immunol.190(1), 438–446 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.LiHui, S. X. & Chengye, J. Growth curve of body mass index of children and adolescents aged 0 to 18 years in China. J. Chin. Pediatr.47, 493–497 (2009). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ni X., & Working Group of Chinese Guideline for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Childhood OSA; Subspecialty Group of Pediatrics, Chinese Medical Association; Subspecialty Group of Respiratory Diseases, Society of Pediatrics, Chinese Medical Association. Society of Pediatric Surgery, Chinese Medical Association; Editorial Board of Chinese Journal of Otorhinolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery. Chinese guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of childhood obstructive sleep apnea (2020). Chin. J. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Surg.55, 729–747 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friedman, M., Ibrahim, H. & Bass, L. Clinical staging for sleep-disordered breathing. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg.127(1), 13–21 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fujioka, Y. L. & Girdany, M. Radiographic evaluation of adenoidal size in children: Adenoidal-nasopharyngeal ratio. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol.133, 401–404 (1979). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cassano, P., Gelardi, M., Cassano, M., Fiorella, M. L. & Fiorella, R. Adenoid tissue rhinopharyngeal obstruction grading based on fiberendoscopic findings: A novel approach to therapeutic management. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol.67(12), 1303–1309 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldbart, A. D. et al. Differential expression of cysteinyl leukotriene receptors 1 and 2 in tonsils of children with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome or recurrent infection. Chest126(1), 13–18 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim, B. R. et al. Increased cellular proliferation and inflammatory cytokines in.pdf. Pediatr. Res.66(4), 423–428 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen, F. V. et al. Inflammatory markers in palatine tonsils of children. Braz J. Otorhinolaryngol.86(1), 23–29 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vaananen, T. et al. YKL-40 as a novel factor associated with inflammation and catabolic mechanisms in osteoarthritic joints. Mediators Inflamm. 215140 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Letuve, S. et al. YKL-40 is elevated in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and activates alveolar macrophages. J. Immunol.181(7), 5167–5173 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mizoguchi, E. Chitinase 3-like-1 exacerbates intestinal inflammation by enhancing bacterial adhesion and invasion in colonic epithelial cells. Gastroenterology130(2), 398–411 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yeo, I. J., Lee, C. K., Han, S. B., Yun, J. & Hong, J. T. Roles of chitinase 3-like 1 in the development of cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, and inflammatory diseases. Pharmacol. Ther.203, 107394 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nielsen, A. R., Plomgaard, P., Krabbe, K. S., Johansen, J. S. & Pedersen, B. K. IL-6, but not TNF-α, increases plasma YKL-40 in human subjects. Cytokine55(1), 152–155 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eltzschig, H. K., Schwartz, R. S. & Carmeliet, P. Hypoxia and inflammation, New England. J. Med.364(7), 656–665 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ambler, D. R., Fletcher, N. M., Diamond, M. P. & Saed, G. M. Effects of hypoxia on the expression of inflammatory markers IL-6 and TNF-a in human normal peritoneal and adhesion fibroblasts. Syst. Biol. Reproduct. Med.58(6), 324–329 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang, Y. et al. Possible mechanism of CHI3L1 promoting tonsil lymphocytes proliferation in children with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Pediatr. Res.91(5), 1099–1105 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen, C., Liang, Y., Zhang, Z., Zhang, Z. & Yang, Z. Relationships between increased circulating YKL-40, IL-6 and TNF-alpha levels and phenotypes and disease activity of primary Sjogren’s syndrome. Int. Immunopharmacol.88, 106878 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen, J. et al. Elevation of YKL-40 in the CSF of Anti-NMDAR encephalitis patients is associated with poor prognosis. Front. Neurol.9 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Israel, L. P., Benharoch, D., Gopas, J. & Goldbart, A. D. A pro-inflammatory role for nuclear factor kappa B in childhood obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Sleep36(12), 1947–1955 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tran, H. T. et al. Chitinase 3-like 1 synergistically activates IL6-mediated STAT3 phosphorylation in intestinal epithelial cells in murine models of infectious colitis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis.20(5), 835–846 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu, W. H., Li, Y., Zhao, P., Li, H. & Yang, R. Quercetin administration following hypoxia-induced neonatal brain damage attenuates later-life seizure susceptibility and anxiety-related behavior: Modulating inflammatory response. Front. Pediatr.11, 10:791815 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hamilton, G. & Rath, B. Circulating tumor cell interactions with macrophages: Implications for biology and treatment. Transl. Lung Cancer Res.6(4), 418–430 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Choi, J. Y. et al. K284-6111 prevents the amyloid beta-induced neuroinflammation and impairment of recognition memory through inhibition of NF-kappaB-mediated CHI3L1 expression. J. Neuroinflam.15(1), 224 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.