Abstract

Based on recent collecting and a synthesis of ~100 years of historical data, 219 caddisfly species are reported from the state of Indiana. Seventeen species are reported herein from the state for the first time, including two previously thought to be endemic to the southeastern USA. Species records are also presented herein organized by drainage basin, ecoregion, glacial history, and waterbody type for two distinct time periods: before 1983 and after 2005. More species were reported from the state before 1983 than after 2005, despite collecting almost 3× the number of occurrence records during the latter period. Species occurrence records were greater for most families and functional feeding groups (FFGs) for the post-2005 time period, although the Limnephilidae, Phryganeidae, Molannidae, and Lepidostomatidae, particularly those in the shredder FFG, instead had greater records before 1983. This loss of shredders probably reflected the ongoing habitat degradation within the state. While species rarefaction predicts only a few more species to be found in Indiana, many regions still remain under-sampled and 44 species have not been collected in >40 years.

Key words: Biological diversity, conservation, distribution, insect, Upper Midwest

Introduction

The caddisflies (Trichoptera) constitute an important group of aquatic organisms due to their high overall abundance, high species richness, high ecological diversity, and differing sensitivities to various anthropogenic disturbances (Barbour et al. 1999; Morse et al. 2019). Determining caddisfly distributions and habitat affinities, therefore, is valuable for assessing water quality and other aspects of ecosystem integrity (Dohet 2002; Houghton and DeWalt 2021). Assessing changes in such data over time can be especially valuable (Houghton and Holzenthal 2010).

The caddisflies of the Upper Midwest region of the United States (MAFWA 2023) have been studied for nearly 100 years, starting with the Illinois fauna (Ross 1938, 1944), including more recent comprehensive studies of Kentucky (Floyd et al. 2012), Michigan (Houghton et al. 2018, Minnesota (Houghton 2012), Missouri (Moulton and Stewart 1996), Ohio (Armitage et al. 2011), and Wisconsin (Hilsenhoff 1995), and culminating with an overall checklist of the entire region (Houghton et al. 2022). The last paper included 131 new state species records combined from eight different states, including five from Indiana, demonstrating that even well-collected areas still contain undiscovered species.

Research on the Indiana caddisfly fauna encompasses two approximate time periods. The first period began in the 1930s and concluded with Waltz and McCafferty’s (1983) checklist of 190 species. Specimens from this period are housed primarily in the Purdue University Entomological Research Collection (PERC) and the Illinois Natural History Survey Insect Collection (INHS). After a ~20-year pause, caddisfly collecting renewed in the early 2000s with subsequent studies by DeWalt et al. (2016a) and Bolton et al. (2019), as well as many specimens accessioned into the PERC, INHS and, more recently, the Hillsdale College Insect Collection (HCIC). This nearly 100-year collecting history provided an opportunity to assess any changes in the caddisfly fauna over time.

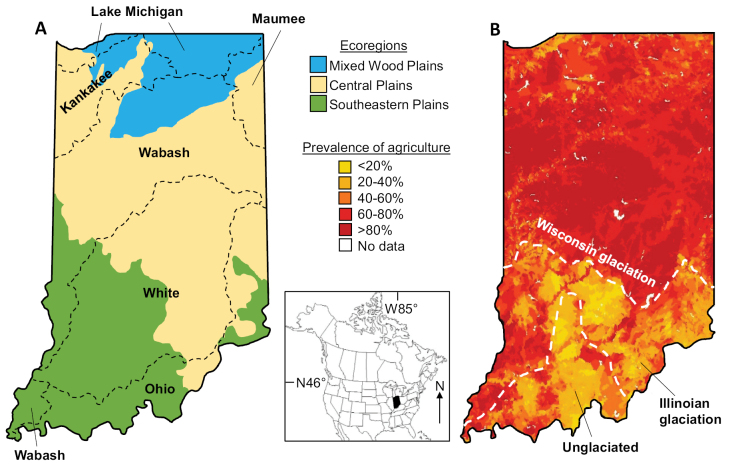

Indiana is composed of a single USEPA Level I ecoregion and three secondary ecoregions: Central Plains, Mixed Wood Plains, and Southeastern Plains (Fig. 1). The predominant land use is agriculture in the form of row crops and pasture, especially in the northern two thirds of the state. Land use corresponds strongly with glacial history, as the low-gradient environments and abundant glacial till of the more recent Wisconsin glaciation are more conducive to farming than the higher-gradient and more eroded older landscapes of the Illinoian glaciation and unglaciated regions.

Figure 1.

Location of the state of Indiana showing the approximate boundaries of drainage basins and ecoregions (A), and prevalence of agriculture and Pleistocene glacial history (B).

The primary objective of this study was to update the state caddisfly checklist for Indiana and relate the occurrences of all species to drainage basin, ecoregion, glacial history, and waterbody type. We also assessed the rarity of all Indiana species. Since >40 years had passed since the last state checklist, we assessed any notable changes to the fauna during this period. Further, we used species rarefaction to predict total species richness for the state and assessed the importance of collecting effort on a regional level.

Materials and methods

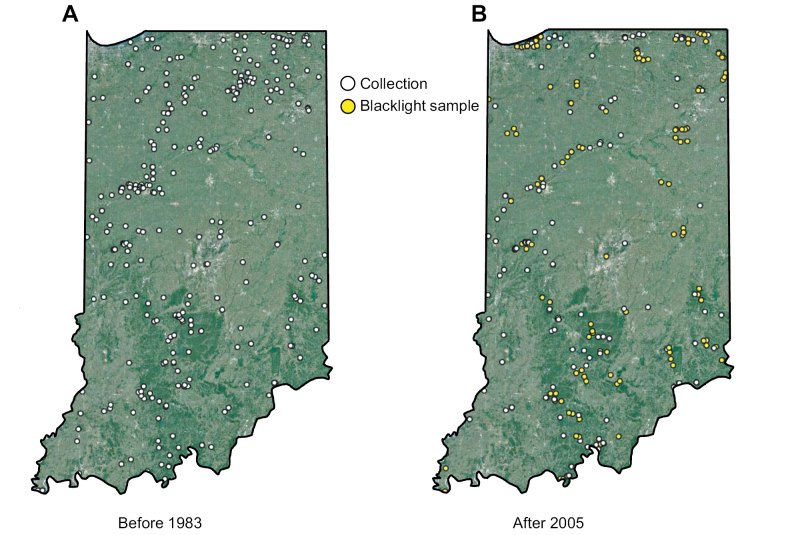

Our primary sampling devices included two types of ultraviolet light traps: an unattended 8-watt light placed over a white pan filled with ethanol, and an attended 12-watt light suspended from a white sheet with two pans filled with ethanol at its base. Such devices were set out at dusk near aquatic habitats and retrieved approximately two hours later (Houghton 2004; Wright et al. 2013; DeWalt et al. 2016a). The nocturnally active caddisfly adults were attracted to the lights and either fell into the pan or were hand-collected (Fabian et al. 2024). Sampling the winged adults is necessary for taxonomic and conservation studies since, unlike larvae, they are usually identifiable to the species level. Moreover, since adults are attracted to lights irrespective of their specific natal microhabitat or functional feeding group (FFG), inferences on ecology and biotic integrity can be made about an ecosystem without the sampling bias that affects benthic studies (Cao and Hawkins 2011). We and our colleagues collected 194 of these ultraviolet light samples from 2005–2023 (Fig. 2, Suppl. material 1). We also databased specimens from the INHS and PERC going back to the early 1900s. These specimens represented collections of unknown effort. Thus, Fig. 2 makes the distinction between “collections” (unknown effort) and “samples” (the ultraviolet light sampling regime described above). All specimens are housed in either the HCIC, INHS, or PERC institutional collection.

Figure 2.

Collecting localities of Indiana caddisflies before 1983 (A) and after 2005 (B). White markers represent collections of unknown sampling effort whereas yellow markers represent ~2 h ultraviolet blacklight samples. Base map © Google, NOAA.

We associated all 1116 unique collecting localities with drainage basin, ecoregion, glacial maximum, and waterbody type. Our approach for dividing the state into geographic and ecological regions was a balance between having divisions specific enough to reflect biological differences, yet large enough to maintain a consistent collecting effort between them. Thus, we divided the state by United States Environmental Protection Agency Level II ecoregions (https://www.epa.gov/eco-research/ecoregions-north-america) and Hydrologic Unit Code (HUC) 6 drainages (https://water.usgs.gov/GIS/huc.html). For the latter we combined smaller watersheds with a common outlet (e.g., the various HUC6 drainages all draining into the Ohio River) into their larger drainages (Fig. 1). While slightly nonstandard, we prefer this categorization over attempting to compare small drainages with minimal collecting effort to those with hundreds of collections. We also divided the state based on glacial maximum (Gray and Letsinger 2011). Lastly, we categorized specific sampling sites by lake or size of stream (https://www.epa.gov/waterdata).

To estimate total species richness for the state, a species rarefaction curve based on all species and samples collected was produced using the program EstimateS for Windows v. 9.1 (https://www.robertkcolwell.org/pages/estimates). In addition to the basic curve, two maximum species richness estimators were calculated. The abundance-based coverage estimator (ACE) predicted total species richness based on a proportion of rare to common species, defining “rare” as any species represented by <10 specimens. The incidence-based coverage estimator (ICE) made the same prediction, but defined “rare” as any species found in <10 samples.

To assess the importance of sampling effort in collecting species, simple linear regression models were calculated for the number of species collected from each of the primary watershed, ecoregion, glacial maximum, and waterbody type designations (dependent variable) based on the accumulated number of unique collections and samples combined (independent variable). Separate models were calculated for the pre-1983 and post-2005 time periods. The number of species associated with each geographic and habitat designation was treated as an independent observation even though each sample or collection was associated with designations of all four types.

Results

A total of 219 caddisfly species among 18 families and 62 genera were determined to occur in the state of Indiana, including 17 species reported for the first time herein (Table 1). An additional seven species were removed from the state checklist due to misidentified specimens, taxonomic changes, or dubious identifications lacking voucher specimens (Table 2). The determined species are based on 80,298 total specimens representing 5223 species occurrence records from 711 unique collecting events before 1983 and 405 events after 2005 (Suppl. material 1). Because a detailed taxonomic history, including all synonymies, and regional distributions of all 219 species have already been treated in Houghton et al. (2022) and Rasmussen and Morse (2023), we do not reproduce those data herein.

Table 1.

The 219 caddisfly species known to occur in Indiana based on all historical and contemporary collecting and sampling. All taxa are arranged alphabetically by order and family. Species reported from the state for the first time are in boldface font. Species records displayed based on those found before 1983 and after 2005. Rarity designation based on number of records after 2005: >20 = abundant, 6–20 = common, 1–5 = rare, 0 = data deficient to determine if the species still exists in the state. Most recent known collection year of data-deficient species are in the last column.

| Records before 1983 | Records after 2005 | Rarity | Most recent | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BRACHYCENTRIDAE (5) | ||||

| Brachycentruslateralis (Say, 1823) | 1 | 0 | Deficient | 1903 |

| Brachycentrusnumerosus (Say, 1823) | 9 | 4 | Rare | – |

| Micrasemarusticum (Hagen, 1868) | 3 | 4 | Rare | – |

| Micrasemascotti Ross, 1947 | 2 | 0 | Deficient | 1977 |

| Micrasemawataga Ross, 1938 | 0 | 2 | Rare | – |

| DIPSEUDOPSIDAE (2) | ||||

| Phylocentropuslucidus (Hagen, 1961) | 1 | 0 | Deficient | 1980 |

| Phylocentropusplacidus (Banks, 1905) | 3 | 6 | Common | – |

| GLOSSOSOMATIDAE (11) | ||||

| Agapetusgelbae Ross, 1947 | 2 | 0 | Deficient | 1946 |

| Agapetusillini Ross, 1938 | 1 | 2 | Rare | – |

| Agapetusspinosus Etnier & Way, 1973 | 0 | 1 | Rare | – |

| Glossosomaintermedium (Klapálek, 1892) | 3 | 2 | Rare | – |

| Glossosomanigrior Banks, 1911 | 1 | 6 | Common | – |

| Protoptilaerotica Ross, 1938 | 1 | 13 | Common | – |

| Protoptilageorgiana Denning, 1948 | 0 | 1 | Rare | – |

| Protoptilalega Ross, 1941 | 0 | 1 | Rare | – |

| Protoptilamaculata (Hagen, 1861) | 7 | 36 | Abundant | – |

| Protoptilapalina Ross, 1941 | 1 | 0 | Deficient | 1948 |

| Protoptilatenebrosa (Walker, 1852) | 1 | 0 | Deficient | 1936 |

| GOERIDAE (1) | ||||

| Goerastylata Ross, 1938 | 1 | 1 | Rare | – |

| HELICOPSYCHIDAE (1) | ||||

| Helicopsycheborealis (Hagen, 1861) | 30 | 59 | Abundant | – |

| HYDROPSYCHIDAE (38) | ||||

| Cheumatopsycheanalis (Banks, 1908) | 44 | 111 | Abundant | – |

| Cheumatopsycheaphanta Ross, 1938 | 3 | 4 | Rare | – |

| Cheumatopsycheburksi Ross, 1941 | 2 | 17 | Common | – |

| Cheumatopsychecampyla Ross, 1938 | 37 | 103 | Abundant | – |

| Cheumatopsychelasia Ross, 1938 | 1 | 1 | Rare | – |

| Cheumatopsycheminuscula (Banks, 1907) | 1 | 0 | Deficient | 1957 |

| Cheumatopsycheoxa Ross, 1938 | 24 | 58 | Abundant | – |

| Cheumatopsychepasella Ross, 1941 | 9 | 49 | Abundant | – |

| Cheumatopsychesordida (Hagen, 1861) | 4 | 15 | Common | – |

| Cheumatopsychespeciosa (Banks, 1904) | 7 | 2 | Rare | – |

| Diplectronametaqui Ross, 1970 | 2 | 3 | Rare | – |

| Diplectronamodesta Banks, 1908 | 26 | 18 | Common | – |

| Homoplectradoringa (Milne, 1936) | 3 | 3 | Rare | – |

| Hydropsycheaerata Ross, 1938 | 6 | 6 | Common | – |

| Hydropsychealternans (Walker, 1852) | 2 | 0 | Deficient | 1951 |

| Hydropsychearinale Ross, 1938 | 1 | 1 | Rare | – |

| Hydropsychebetteni Ross, 1938 | 31 | 88 | Abundant | – |

| Hydropsychebronta Ross, 1938 | 17 | 71 | Abundant | – |

| Hydropsychecheilonis Ross, 1938 | 14 | 31 | Abundant | – |

| Hydropsychecuanis Ross, 1938 | 8 | 8 | Common | – |

| Hydropsychedepravata Hagen, 1861 | 5 | 11 | Common | – |

| Hydropsychedicantha Ross, 1938 | 9 | 10 | Common | – |

| Hydropsychefrisoni Ross, 1938 | 4 | 11 | Common | – |

| Hydropsychehageni Banks, 1905 | 1 | 0 | Deficient | 1950 |

| Hydropsycheincommoda Hagen, 1861 | 44 | 68 | Abundant | – |

| Hydropsychemorosa Hagen, 1861 | 43 | 7 | Common | – |

| Hydropsychephalerata Hagen, 1861 | 13 | 23 | Abundant | – |

| Hydropsycheplacoda Ross, 1941 | 0 | 1 | Rare | – |

| Hydropsychescalaris Hagen, 1861 | 5 | 5 | Rare | – |

| Hydropsychesimulans Ross, 1938 | 27 | 66 | Abundant | – |

| Hydropsycheslossonae Banks, 1905 | 8 | 8 | Common | – |

| Hydropsychesparna Ross, 1938 | 17 | 58 | Abundant | – |

| Hydropsychevalanis Ross, 1938 | 8 | 1 | Rare | – |

| Macrostemumcarolina (Banks, 1909) | 10 | 11 | Common | – |

| Macrostemumtransversum (Walker, 1852) | 2 | 1 | Rare | – |

| Macrostemumzebratum (Hagen, 1861) | 14 | 11 | Common | – |

| Potamyiaflava (Hagen, 1861) | 46 | 92 | Abundant | – |

| HYDROPTILIDAE (42) | ||||

| Agrayleamultipunctata Curtis, 1834 | 5 | 12 | Common | – |

| Dibusaangata Ross, 1939 | 1 | 0 | Deficient | 1950 |

| Hydroptilaajax Ross, 1938 | 2 | 19 | Common | – |

| Hydroptilaalbicornis Hagen, 1861 | 1 | 2 | Rare | – |

| Hydroptilaamoena Ross, 1938 | 1 | 0 | Deficient | 1976 |

| Hydroptilaangusta Ross, 1938 | 8 | 66 | Abundant | – |

| Hydroptilaarmata Ross, 1938 | 7 | 77 | Abundant | – |

| Hydroptilaconsimilis Morton, 1905 | 6 | 56 | Abundant | – |

| Hydroptiladelineata Morton, 1905 | 2 | 0 | Deficient | 1937 |

| Hydroptilagrandiosa Ross, 1938 | 5 | 53 | Abundant | – |

| Hydroptilagunda Milne, 1939 | 0 | 10 | Common | – |

| Hydroptilahamata Morton, 1905 | 1 | 26 | Abundant | – |

| Hydroptilajackmanni Blickle, 1963 | 1 | 0 | Deficient | 1976 |

| Hydroptilaperdita Morton, 1905 | 10 | 72 | Abundant | – |

| Hydroptilascolops Ross, 1938 | 0 | 2 | Rare | – |

| Hydroptilaspatulata Morton, 1905 | 3 | 16 | Common | – |

| Hydroptilavala Ross, 1938 | 1 | 0 | Deficient | 1976 |

| Hydroptilawaubesiana Betten, 1934 | 16 | 128 | Abundant | – |

| Ithytrichiaclavata Morton, 1905 | 0 | 4 | Rare | – |

| Leucotrichiapictipes (Banks, 1911) | 0 | 1 | Rare | – |

| Mayatrichiaayama Mosely, 1937 | 1 | 1 | Rare | – |

| Neotrichiaminutisimella (Chambers, 1873) | 1 | 1 | Rare | – |

| Neotrichiaokopa Ross, 1939 | 0 | 1 | Rare | – |

| Neotrichiavibrans Ross, 1938 | 0 | 3 | Rare | – |

| Ochrotrichiaeliaga (Ross, 1941) | 3 | 0 | Deficient | 1975 |

| Ochrotrichiariesi Ross, 1944 | 1 | 0 | Deficient | 1945 |

| Ochrotrichiatarsalis (Hagen, 1861) | 6 | 26 | Abundant | – |

| Ochrotrichiawojcickyi Blickle, 1963 | 1 | 0 | Deficient | 1980 |

| Ochrotrichiaxena (Ross, 1938) | 3 | 0 | Deficient | 1976 |

| Orthotrichiaaegerfasciella (Chambers, 1873) | 5 | 63 | Abundant | – |

| Orthotrichiabaldufi Kingsolver & Ross, 1961 | 0 | 2 | Rare | – |

| Orthotrichiacristata Morton, 1905 | 5 | 43 | Abundant | – |

| Oxyethiracoercens Morton, 1905 | 2 | 2 | Rare | – |

| Oxyethiradualis Morton, 1905 | 0 | 1 | Rare | – |

| Oxyethiraforcipata Mosely, 1934 | 1 | 19 | Common | – |

| Oxyethiragrisea Betten, 1834 | 2 | 0 | Deficient | 1937 |

| Oxyethiranovasota Ross, 1944 | 0 | 1 | Rare | – |

| Oxyethiraobtatus Denning, 1947 | 0 | 4 | Rare | – |

| Oxyethirapallida (Banks, 1904) | 7 | 102 | Abundant | – |

| Oxyethiraserrata Ross, 1938 | 0 | 3 | Rare | – |

| Oxyethirazeronia Ross, 1941 | 0 | 8 | Common | – |

| Stactobielladelira (Ross, 1938) | 1 | 1 | Rare | – |

| LEPIDOSTOMATIDAE (3) | ||||

| Lepidostomaliba Ross, 1941 | 3 | 1 | Rare | – |

| Lepidostomasommermanae Ross, 1946 | 2 | 0 | Deficient | 1980 |

| Lepidostomatogatum (Hagen, 1861) | 0 | 11 | Common | – |

| LEPTOCERIDAE (43) | ||||

| Ceracleaalagma (Ross, 1938) | 4 | 12 | Common | – |

| Ceracleaancylus (Vorhies, 1909) | 6 | 5 | Rare | – |

| Ceracleaannulicornis (Stephens, 1836) | 1 | 1 | Rare | – |

| Ceracleacancellata (Betten, 1934) | 14 | 19 | Common | – |

| Ceracleadiluta (Hagen, 1861) | 6 | 0 | Deficient | 1975 |

| Ceracleaenodis Whitlock & Morse, 1994 | 0 | 1 | Rare | – |

| Ceracleaflava (Banks, 1904) | 3 | 5 | Rare | – |

| Ceracleamaculata (Banks, 1899) | 24 | 96 | Abundant | – |

| Ceracleamentiea (Walker, 1852) | 1 | 3 | Rare | – |

| Ceracleanepha (Ross, 1944) | 0 | 2 | Rare | – |

| Ceracleaophioderus (Ross, 1938) | 1 | 0 | Deficient | 1947 |

| Ceracleapunctata (Banks, 1894) | 0 | 4 | Rare | – |

| Ceraclearesurgens (Walker, 1852) | 4 | 0 | Deficient | 1975 |

| Ceracleaspongillovorax (Resh, 1974) | 2 | 0 | Deficient | 1974 |

| Ceracleatarsipunctata (Vorhies,1909) | 19 | 90 | Abundant | – |

| Ceracleatransversa (Hagen, 1861) | 19 | 42 | Abundant | – |

| Leptocerusamericanus (Banks, 1899) | 20 | 82 | Abundant | – |

| Mystacidesinterjectus (Banks, 1914) | 4 | 1 | Rare | – |

| Mystacidessepulchralis (Walker, 1852) | 13 | 23 | Abundant | – |

| Nectopsychealbida (Walker, 1852) | 4 | 9 | Common | – |

| Nectopsychecandida (Hagen) 1861 | 27 | 45 | Abundant | – |

| Nectopsychediarina (Ross, 1944) | 14 | 27 | Abundant | – |

| Nectopsycheexquisita (Walker, 1852) | 8 | 14 | Common | – |

| Nectopsychepavida (Hagen, 1861) | 6 | 41 | Abundant | – |

| Oecetisavara (Banks, 1895) | 7 | 27 | Abundant | – |

| Oecetiscinerascens (Hagen, 1861) | 27 | 85 | Abundant | – |

| Oecetisditissa Ross, 1966 | 8 | 11 | Common | – |

| Oecetisinconspicua (Walker, 1852) | 46 | 159 | Abundant | – |

| Oecetisimmobilis (Hagen, 1861) | 9 | 1 | Rare | – |

| Oecetisnocturna Ross, 1966 | 14 | 24 | Abundant | – |

| Oecetisochracea Curtis, 1825 | 2 | 2 | Rare | – |

| Oecetisosteni Milne, 1934 | 12 | 3 | Rare | – |

| Oecetispersimilis (Banks, 1907) | 7 | 47 | Abundant | – |

| Setodesoligius (Ross, 1938) | 3 | 2 | Rare | – |

| Triaenodesaba Milne, 1935 | 1 | 15 | Common | – |

| Triaenodesflavescens Banks, 1900 | 3 | 0 | Deficient | 1980 |

| Triaenodesignitus (Walker, 1852) | 3 | 26 | Abundant | – |

| Triaenodesinjustus (Hagen, 1861) | 12 | 50 | Abundant | – |

| Triaenodesmarginatus Sibley, 1926 | 3 | 34 | Abundant | – |

| Triaenodesmelacus Ross, 1947 | 1 | 16 | Common | – |

| Triaenodesnox Ross, 1941 | 3 | 2 | Rare | – |

| Triaenodesperna Ross, 1938 | 0 | 4 | Rare | – |

| Triaenodestardus Milne, 1934 | 17 | 57 | Abundant | – |

| LIMNEPHILIDAE (20) | ||||

| Anaboliabimaculata (Walker, 1852) | 4 | 2 | Rare | – |

| Anaboliaconsocia (Walker, 1852) | 7 | 3 | Rare | – |

| Frenesiamissa (Milne, 1935) | 5 | 1 | Rare | – |

| Hydatophylaxargus (Harris, 1869) | 5 | 0 | Deficient | 1980 |

| Ironoquiakaskaskia (Ross, 1944) | 1 | 0 | Deficient | unknown |

| Ironoquialyrata (Ross, 1938) | 1 | 0 | Deficient | 1978 |

| Ironoquiapunctatissima (Walker, 1852) | 3 | 10 | Common | – |

| Limnephilusindivisus Walker, 1852 | 8 | 4 | Rare | – |

| Limnephilusornatus Banks, 1897 | 2 | 0 | Deficient | 1946 |

| Limnephilusrhombicus (Linneaus, 1758) | 1 | 0 | Deficient | 1960 |

| Limnephilussubmonilifer Walker, 1852 | 16 | 4 | Rare | – |

| Platycentropusradiatus (Say, 1824) | 9 | 11 | Common | – |

| Pseudostenophylaxuniformis (Betten, 1934) | 3 | 2 | Rare | – |

| Pycnopsycheguttifera (Walker, 1852) | 6 | 14 | Common | – |

| Pycnopsycheindiana (Ross, 1938) | 7 | 30 | Abundant | – |

| Pycnopsychelepida (Hagen, 1861) | 6 | 5 | Rare | – |

| Pycnopsycheluculenta (Betten, 1934) | 4 | 0 | Deficient | 1981 |

| Pycnopsycherossi Betten, 1950 | 2 | 0 | Deficient | 1980 |

| Pycnopsychescabripennis (Rambur, 1842) | 9 | 3 | Rare | – |

| Pycnopsychesubfasciata (Say, 1828) | 15 | 17 | Common | – |

| MOLANNIDAE (4) | ||||

| Molannablenda Sibley, 1926 | 2 | 0 | Deficient | 1981 |

| Molannatryphena Betten, 1934 | 0 | 7 | Common | – |

| Molannaulmerina Navas, 1934 | 3 | 0 | Deficient | 1960 |

| Molannauniophila Vorhies, 1909 | 10 | 6 | Common | – |

| ODONTOCERIDAE (1) | ||||

| Mariliaflexuosa Ulmer, 1905 | 2 | 2 | Rare | – |

| PHILOPOTAMIDAE (7) | ||||

| Chimarraaterrima Hagen, 1861 | 10 | 12 | Common | – |

| Chimarraferia Ross, 1941 | 3 | 9 | Common | – |

| Chimarramoselyi Denning, 1948 | 1 | 0 | Deficient | unknown |

| Chimarraobscura (Walker, 1852) | 8 | 98 | Abundant | – |

| Dolophilodesdistinctus (Walker, 1852) | 6 | 6 | Common | – |

| Wormaldiamoesta (Banks, 1914) | 4 | 7 | Common | – |

| Wormaldiashawnee (Ross, 1938) | 1 | 2 | Rare | – |

| PHRYGANEIDAE (11) | ||||

| Agrypniastraminea Hagen, 1873 | 2 | 0 | Deficient | 1948 |

| Agrypniavestita (Walker, 1852) | 6 | 5 | Rare | – |

| Banksiolacrotchi Banks, 1943 | 1 | 6 | Common | – |

| Fabriainornata (Banks, 1907) | 1 | 0 | Deficient | 1966 |

| Oligostomisocelligera (Walker, 1852) | 1 | 0 | Deficient | 1978 |

| Phryganeacinerea Walker, 1852 | 1 | 4 | Rare | – |

| Phryganeasayi Milne, 1931 | 3 | 4 | Rare | – |

| Ptilostomisangustipennis (Hagen, 1873) | 1 | 0 | Deficient | 1950 |

| Ptilostomisocellifera (Walker, 1852) | 7 | 28 | Abundant | – |

| Ptilostomispostica (Walker, 1852) | 4 | 4 | Rare | – |

| Ptilostomissemifasciata (Say, 1828) | 2 | 9 | Common | – |

| POLYCENTROPODIDAE (20) | ||||

| Cernotinacalcea Ross, 1938 | 0 | 15 | Common | – |

| Cernotinaspicata Ross, 1938 | 4 | 24 | Abundant | – |

| Cyrnellusfraternus (Banks, 1913) | 17 | 67 | Abundant | – |

| Holocentropusflavus Banks, 1909 | 1 | 0 | Deficient | 1981 |

| Holocentropusglacialis Ross, 1938 | 5 | 4 | Rare | – |

| Holocentropusinterruptus Banks, 1914 | 4 | 1 | Rare | – |

| Neureclipsiscrepuscularis (Walker, 1852) | 18 | 50 | Abundant | – |

| Neureclipsispiersoni Frazer & Harris, 1991 | 1 | 2 | Rare | – |

| Nyctiophylaxaffinis (Banks, 1897) | 9 | 12 | Common | – |

| Nyctiophylaxmoestus Banks, 1911 | 5 | 57 | Abundant | – |

| Plectrocnemiacinerea (Hagen, 1861) | 20 | 48 | Abundant | – |

| Plectrocnemiaclinei (Milne, 1936) | 0 | 1 | Rare | – |

| Plectrocnemiacrassicornis (Walker, 1852) | 2 | 3 | Rare | – |

| Plectrocnemianascotius (Ross, 1941) | 0 | 4 | Rare | – |

| Plectrocnemiaremotus Banks, 1911 | 4 | 2 | Rare | – |

| Polycentropuscentralis Banks, 1914 | 7 | 24 | Abundant | – |

| Polycentropuschelatus Ross & Yamamoto, 1965 | 1 | 0 | Deficient | 1976 |

| Polycentropusconfusus Hagen, 1861 | 0 | 12 | Common | – |

| Polycentropuselarus Ross, 1944 | 1 | 0 | Deficient | 1963 |

| Polycentropuspentus Ross, 1941 | 0 | 1 | Rare | – |

| PSYCHOMYIIDAE (2) | ||||

| Lypediversa (Banks, 1914) | 3 | 42 | Abundant | – |

| Psychomyiaflavida Hagen, 1861 | 3 | 37 | Abundant | – |

| RHYACOPHILIDAE (6) | ||||

| Rhyacophilafenestra Ross, 1938 | 6 | 15 | Common | – |

| Rhyacophilaglaberrima Ulmer, 1907 | 1 | 0 | Deficient | 1948 |

| Rhyacophilaledra Ross, 1939 | 5 | 4 | Rare | – |

| Rhyacophilalobifera Betten, 1934 | 7 | 20 | Common | – |

| Rhyacophilaparantra Ross, 1948 | 6 | 1 | Rare | – |

| Rhyacophilavibox Milne, 1936 | 1 | 2 | Rare | – |

| THREMMATIDAE (3) | ||||

| Neophylaxayanus Ross, 1938 | 2 | 4 | Rare | – |

| Neophylaxconcinnus MacLachlan, 1871 | 13 | 22 | Abundant | – |

| Neophylaxfuscus Banks, 1903 | 3 | 0 | Deficient | 1958 |

| Total records | 1399 | 3824 | – | |

| Total genera | 60 | 59 | – | |

| Total species | 191 | 175 | – | |

Table 2.

The seven species listed as occurring in Indiana (Rasmussen and Morse 2023) that should be removed from the state checklist due to misidentified specimens, taxonomic changes, or dubious identification without voucher specimens.

| Taxon | Reference | Reason |

|---|---|---|

| Cheumatopsycheharwoodi Denning, 1948 | Waltz and McCafferty 1983 | Misidentified. Specimens are actually C.analis |

| Hydropsychealvata Denning, 1949 | Waltz and McCafferty 1983 | Junior synonym of H.incommoda (Korecki 2006 |

| Hydropsychebidens Ross, 1938 | Waltz and McCafferty 1983 | Junior synonym of H.incommoda (Korecki 2006) |

| Hydropsycheorris Ross, 1938 | Waltz and McCafferty 1983 | Junior synonym of H.incommoda (Korecki 2006) |

| Hydropsycherossi Flint et al., 1979 | Waltz and McCafferty 1983 | Junior synonym of H.simulans (Korecki 2006) |

| Hydropsychevenularis Banks, 1914 | Bright (1985) | Larval record without voucher specimens |

| Pycnopsycheantica (Walker, 1852) | Wojtowicz (1982) | Junior synonym of P.scabripennis (Green 2023) |

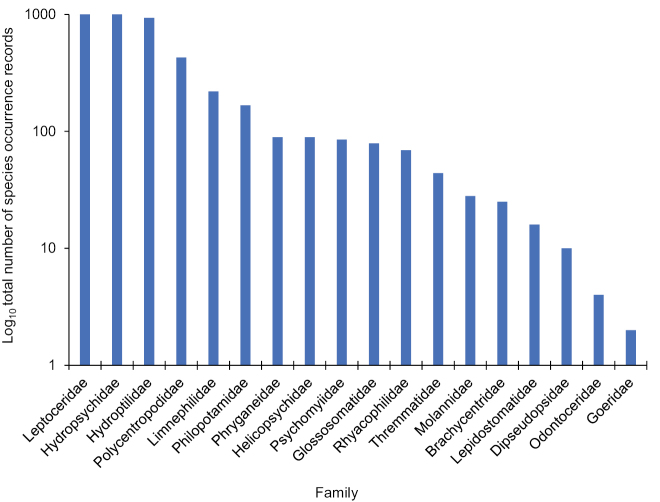

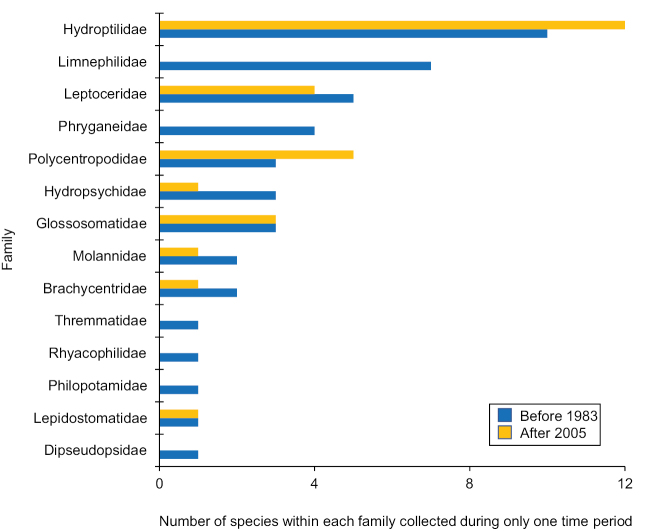

Of the known species, 100 (46%) were considered abundant or common, whereas 75 (34%) were considered rare, and 44 (20%) have not been collected in the last 40 years and, thus, were considered data deficient (Table 1). Leptoceridae (43 species), Hydroptilidae (42), and Hydropsychidae (38) were the most species rich families. They were also the families with the greatest number of total species occurrence records, collectively encompassing nearly 75% of all such records (Fig. 3). Species found only either before 1983 or after 2005 occurred in similar proportions for most families. The exceptions were the Limnephilidae and Phryganeidae, which collectively included 11 species found only before 1983 and none found only after 2005 (Fig. 4). The genera Fabria, Oligostomis (both Phryganeidae), and Hydatophylax (Limnephilidae) were found only before 1983, whereas Ithytrichia and Leucotrichia (both Hydroptilidae) were found only after 2005.

Figure 3.

Log10 number of species occurrence records for each of the 18 caddisfly families known from Indiana based on all historical and contemporary collecting and sampling.

Figure 4.

The 72 species collected either before 1983 or after 2005, but not during both periods, organized by family.

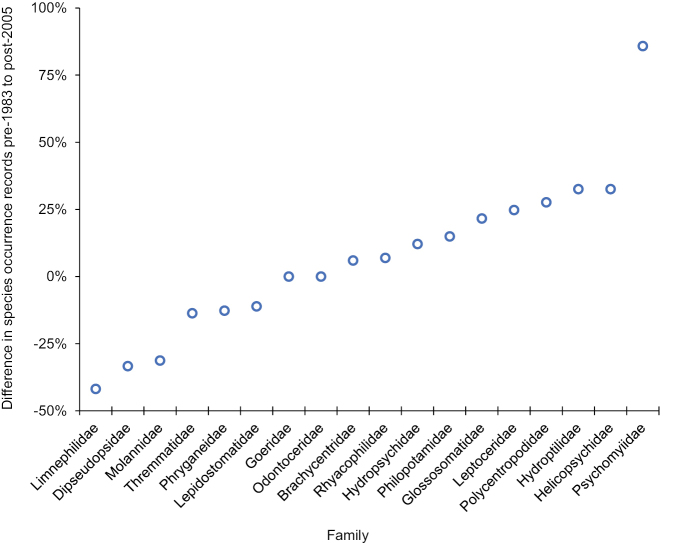

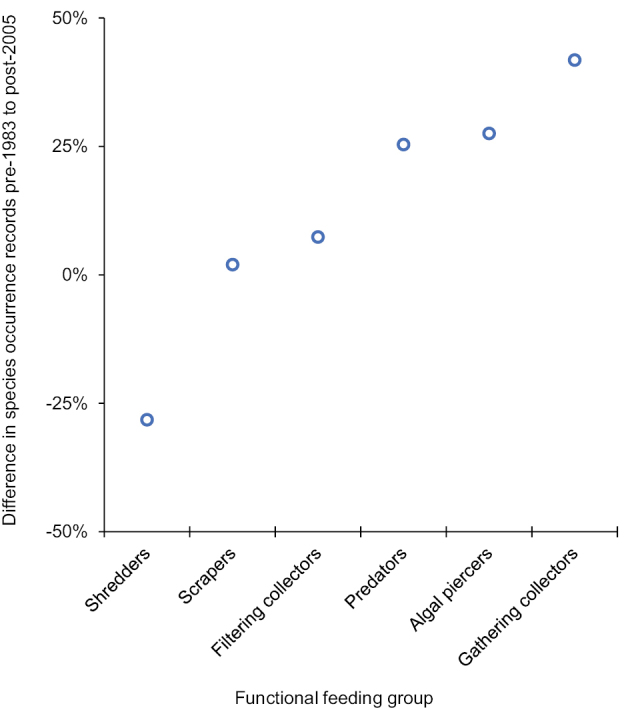

On average, species for 12 of the 18 families had an equal or greater number of occurrence records after 2005 than they did before 1983. The exceptions were the Lepidostomatidae (−11%), Phryganeidae (−12%), Thremmatidae (−13%), Molannidae (−31%), Dipseudopsidae (−33%), and Limnephilidae (−42%) (Fig. 5). Similarly, all FFGs had an equal or greater number of occurrence records after 2005 than they did before 1983, except for shredders which decreased by nearly 30% (Fig. 6).

Figure 5.

Mean difference between the two time periods of the study in the number of total species occurrence records among the 18 caddisfly families known from Indiana. Difference per species was calculated by subtracting the number of pre-1983 records from the number of post-2005 records and then dividing the result by the total number of records. These values were then averaged to determine the mean difference per family. A positive value signified a greater number of post-2005 records, whereas a negative value signified a greater number of pre-1983 records. Species occurrence data taken from Table 1.

Figure 6.

Mean difference between the two time periods of the study in the number of total species occurrence records among the five primary functional feeding groups (FFGs) known from Indiana. Difference per species was calculated by subtracting the number of pre-1983 records from the number of post-2005 records and then dividing the result by the total number of records. These values were then averaged to determine the mean difference per FFG. A positive value signified a greater number of post-2005 records, whereas a negative value signified a greater number of pre-1983 records. Species occurrence data taken from Table 1. FFG data taken from Merritt et al. (2019).

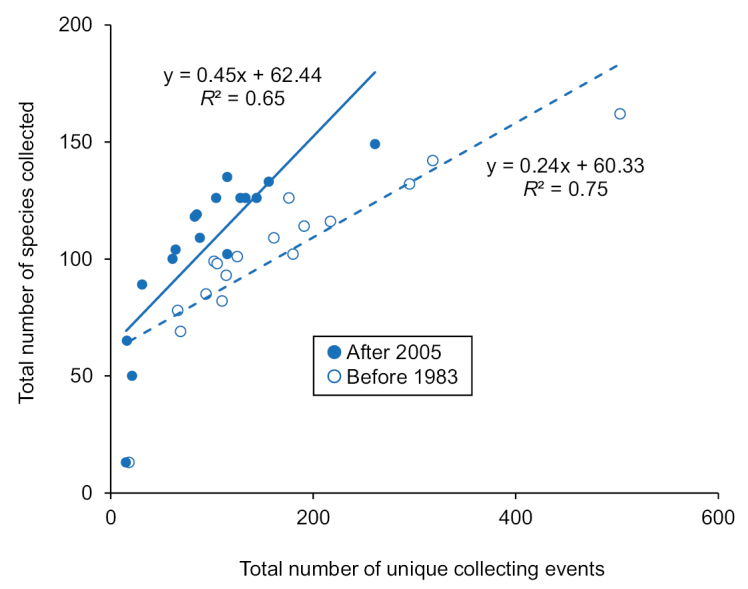

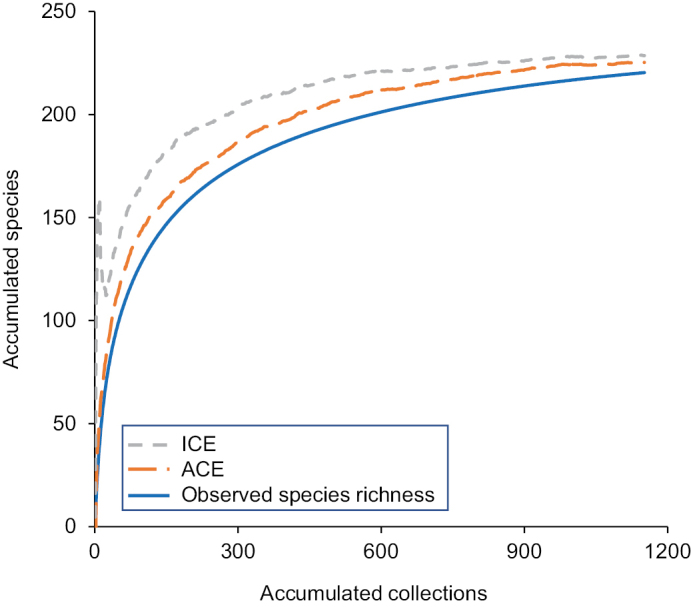

Individual associations between species and the various geographic and habitat designations are in Suppl. material 2 and summarized in Suppl. material 1. Overall species richness differences between the different designations were unremarkable, with the number of unique collecting events being a strong predictor of species richness for both pre-1983 and post-2005 time periods (Fig. 7). Fewer species were caught after 2005 (175) than before 1983 (191) despite having nearly 3× the species occurrence records in the post-2005 time period (Table 1). Total species richness for Indiana was predicted to be 225 and 228 species by ACE and ICE respectively (Fig. 8).

Figure 7.

Simple linear regression models of caddisfly species richness (dependent variable) based on the total number of combined collections and samples taken (independent variable) for the two time periods of the study based on all geographic and ecological subunits of Indiana (Suppl. material 2).

Figure 8.

Species rarefaction curves for all historical and recent collections and samples, showing the accumulated number of species and two estimators: the abundance-based coverage estimator (ACE) and the incidence-based coverage estimator (ICE) of actual species richness. For each series, 50 randomized combinations of sample order were calculated and a mean value determined and displayed.

Discussion

Overall species richness within the state was not particularly remarkable or regionally distinctive, which probably reflected a general lack of habitat diversity within Indiana relative to nearby states like Michigan or Wisconsin (Omernik and Griffith 2014). Indiana has no known endemic caddisflies (Rasmussen and Morse 2023). Total species richness of Indiana lagged behind that of the adjacent states of Michigan (319 species), Kentucky (296), Wisconsin (284), and Ohio (276), but was slightly ahead of Illinois (218) (Houghton et al. 2022). Perhaps the most noteworthy difference was the higher richness in the northern half of the state despite having higher agricultural disturbance than the southern half. The Lake Michigan watershed was particularly rich despite having one of the smallest areas. This difference may be due to the high sampling effort of the region. It may also be that the northern portion of Indiana has naturally high species richness due to naturally high groundwater input or its position as an ecotone between prairie and forest (Omernik and Griffith 2014; DeWalt et al. 2016b). In the absence of disturbance, Houghton and DeWalt (2023) predicted the Wisconsin glaciated area in the northern region of the state to have ~1.5× the caddisfly richness per stream than the Illinoian or unglaciated areas. The age of the habitats might also be important, as the more heterogeneous substrates left behind by the recent Wisconsin glaciation probably increased the microhabitat diversity of streams relative to the older eroded landscapes of the Illinoian and unglaciated regions (Benn and Evans 2010).

Differences in caddisfly species occurrence records between the pre-1983 and post-2005 sampling periods indicated the effects of continued habitat degradation in the state. The goal of the current study was to sample the caddisflies with a greater effort than had been done during the pre-1983 sampling period. It is difficult to state definitively that this goal has been accomplished due to the unclear effort of pre-1983 collections; however, the almost 3× greater number of species occurrence records overall and for most families and FFGs in the post-2005 sampling period suggested that it has. Most exceptions were species that were physically large, such as those of Limnephilidae, Molannidae, and Phryganeidae, and in the shredder FFG, such as those of Lepidostomatidae, Limnephilidae, and Phryganeidae. The other two decreasing families, Dipseudopsidae and Thremmatidae have only a few species and, thus, may be more prone to stochastic variation. Houghton and Holzenthal (2010) noted a similar decrease in species occurrence records for large shredders in the Limnephilidae and Phryganeidae in Minnesota. In a study of the Upper Midwest region of the USA, Houghton and DeWalt (2021) observed that >50% of richness loss in shredder species was explained by watershed disturbance, which was more than that of any other FFG. Since shredders are directly dependent on the input of their coarse allochthonous food source, it is expected that they would most directly correlate with intact habitat, especially that of the riparian zone (Houghton et al. 2011; Dohet et al. 2014; Entrekin et al. 2020; Houghton 2021; Williams and Houghton 2024). Moreover, larger caddisfly species in the Limnephilidae and Phryganeidae tend to be uni- or semivoltine (Merritt et al. 2019) and their longer larval period would expose them to habitat disturbances for more time than a multivoltine species would experience. Such a phenomenon has been previously noted for stoneflies in Illinois (DeWalt et al. 2005).

Collection data for new state species records are in Suppl. material 3. The majority of these records are not surprising, as they have previously been found in at least one state adjacent to Indiana. The two notable exceptions were Agapetusspinosus Etnier & Way, 1973 and Protoptilageorgiana Denning, 1948 (both Glossosomatidae). Both of these species were previously thought to be endemic to the southeastern USA, with A.spinosus known only from Alabama, South Carolina, and Tennessee, and P.georgiana from Alabama, Georgia, Maryland, North Carolina, and Virginia (Rasmussen and Morse 2023). Interestingly, both species were collected from the same site: Marble Creek, downstream of the Big Oaks Wildlife Refuge (BONWR) in Jefferson County (38.8983, −85.4646). The BONWR is one of the least disturbed habitats in Indiana and also one of the least studied, with no known previous collections from it.

Due to the recent sampling effort, most known Indiana species are still presumed extant in the state. Nonetheless, 44 species have not been seen in >40 years and remain data deficient. Eighteen of these species have not been collected in the state since the 1950s and, thus, could have been extirpated by the agricultural development that began after World War II (Omernik 1987). Most notably, Brachycentruslateralis (Say, 1823) has not been seen in Indiana for 121 years.

Future research should include additional sampling. While the species rarefaction curve only predicts a few more species to be found in Indiana, the strong relationship between sampling effort and species caught within the various geographic and habitat designations suggests that a “Wallacean Shortfall” – a lack of detailed data on species distributions (Lomolino 2004) – still remains within the state, and that additional sampling is needed. This shortfall may be pronounced in some autumn-emergent species of Lepidostomatidae and Limnephilidae, due to the difficulty of collecting during the autumn flight period. Since species records for both of these families have decreased since the pre-1983 time period, more autumn sampling is necessary to clarify the reason for this decrease. Conservation efforts in Indiana should probably focus on the 75 rare species, all of which have been collected during the last 2–6 years and are presumed to be extant. Specifically, more information on the life history and specific habitat needs of rare species is necessary to formulate more specific plans for their conservation. Lastly, known or suspected habitats of the 44 data-deficient species should be sampled to ascertain whether these species remain extant in Indiana.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the efforts of all who have collected, sorted, and identified Indiana caddisflies, including Kiralyn Brakel, Maliq Brock, Abrial Cocelli, Henrey Deese, Erin Flaherty, Janae Israel, Ryan Lardner, Caitlin Lowry, Jeremy Luce, Katelyn Mitchell, Evan Newman, Christina Peterson, Megan Phelps, Parker Reed, Joseph Ritzer, David Ruiter, Kayari Suganuma, Noah Youtz, and Molly Williams. Collecting from the Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore was granted under permit INDU-2013-SCI-007. Philip Hogan helped produce Fig. 1. The valuable comments of Bob Haack and Kiralyn Brakel improved an earlier version of the manuscript. Google Earth base maps were used following permission guidelines (https://www.google.com/permissions/geoguidelines/attr-guide/). This is paper #40 of the GH Gordon BioStation Research Series.

Citation

Houghton DC, DeWalt RE (2024) Updated checklist, habitat affinities, and changes over time of the Indiana (USA) caddisfly fauna (Insecta, Trichoptera). ZooKeys 1216: 201–218. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.1216.129914

Additional information

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Ethical statement

No ethical statement was reported.

Funding

Funding for this study came from Indiana Department of Natural Resources grants to DCH (64742) and RED (40777) and from the Hillsdale College biology department.

Author contributions

Conceptualization (DCH), obtaining funding (DCH and RED), sampling (DCH and RED), specimen identification (DCH and RED), data analysis (DCH), manuscript preparation (DCH), manuscript editing (DCH and RED). Both authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Author ORCIDs

David Houghton https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6946-4864

R. Edward DeWalt https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9985-9250

Data availability

All of the data that support the findings of this study are available in the main text or Supplementary Information.

Supplementary materials

Summary of our collection data by ecological regions and habitat types

This dataset is made available under the Open Database License (http://opendatacommons.org/licenses/odbl/1.0/). The Open Database License (ODbL) is a license agreement intended to allow users to freely share, modify, and use this Dataset while maintaining this same freedom for others, provided that the original source and author(s) are credited.

David C. Houghton, R. Edward DeWalt

Data type

xlsx

Historical (before 1983), recent (after 2005), and combined species occurrence records for the 219 known Indiana caddisfly species

This dataset is made available under the Open Database License (http://opendatacommons.org/licenses/odbl/1.0/). The Open Database License (ODbL) is a license agreement intended to allow users to freely share, modify, and use this Dataset while maintaining this same freedom for others, provided that the original source and author(s) are credited.

David C. Houghton, R. Edward DeWalt

Data type

xlsx

Specific collection data for the new Indiana state caddisfly species records reported herein

This dataset is made available under the Open Database License (http://opendatacommons.org/licenses/odbl/1.0/). The Open Database License (ODbL) is a license agreement intended to allow users to freely share, modify, and use this Dataset while maintaining this same freedom for others, provided that the original source and author(s) are credited.

David C. Houghton, R. Edward DeWalt

Data type

xlsx

References

- Armitage BJ, Harris SC, Schuster GA, Usis JD, MacLean DB, Foote BA, Bolton MJ, Garono RJ. (2011) Atlas of Ohio aquatic insects, Volume 1: Trichoptera. Ohio Biological Survey, Hilliard, Ohio.

- Barbour MT, Gerritsen J, Snyder BD, Stribling JB. (1999) Rapid Bioassessment Protocols for Use in Streams and Rivers: Periphyton, Benthic Macroinvertebrates, and Fish, 2nd ed. EPA841-B-99-002. Office of Water, US Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC.

- Benn DI, Evans DJ. (2010) Glaciers and Glaciation, 2nd ed. Arnold, London.

- Bolton MJ, Macy SK, DeWalt RE, Jacobus LM. (2019) New Ohio and Indiana records of aquatic insects (Ephemeroptera, Plecoptera, Trichoptera, Coleoptera: Elmidae, Diptera: Chironomidae). Ohio Biological Survey Notes 9: 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Bright GB. (1985) Notes on the caddisflies of the Kankakee River in Indiana. Indiana Academy of Science 95: 191–194. [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y, Hawkins CP. (2011) The comparability of bioassessments: a review of conceptual and methodological issues. Journal of the North American Benthological Society 30: 680–70. 10.1899/10-067.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DeWalt RE, Favret C, Webb DW. (2005) Just how imperiled are aquatic insects? A case study of stoneflies (Plecoptera) in Illinois. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 98: 941–950. 10.1603/0013-8746(2005)098[0941:JHIAAI]2.0.CO;2 [DOI]

- DeWalt RE, South EJ, Robertson DR, Marburger JE, Smith WW, Brinson V. (2016a) Mayflies, stoneflies, and caddisflies of streams and marshes of Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore, USA. ZooKeys 556: 43–63. 10.3897/zookeys.556.6725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeWalt R, Grubbs S, Armitage B, Baumann R, Clark S, Bolton M. (2016b) Atlas of Ohio aquatic insects: volume II, Plecoptera. Biodiversity Data Journal 4: e10723. 10.3897/BDJ.4.e10723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Dohet A. (2002) Are caddisflies an ideal group for the assessment of water quality in streams? In: Mey W. (Ed.) Proceedings of the 10th International Symposium on Trichoptera, 30 July–05 August, Potsdam, Germany.Nova Supplementa Entomologica, Keltern, Germany, 507–520.

- Dohet A, Hlúbiková D, Wetzel CE, L’Hoste L, Iffly JF, Hoffmann L, Ector L. (2014) Influence of thermal regime and land use on benthic invertebrate communities inhabiting headwater streams exposed to contrasted shading. Science of the Total Environment 505: 1112–1126. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.10.077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Entrekin SA, Rosi EJ, Tank JL, Hoellein TJ, Lamberti GA. (2020) Quantitative food webs indicate modest increases in the transfer of allochthonous and autochthonous C to macroinvertebrates following a large wood addition to a temperate headwater stream. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 8:114. 10.3389/fevo.2020.00114 [DOI]

- Fabian ST, Sondhi Y, Allen PE, Theobald JC, Lin H-T. (2024) Why flying insects gather at artificial light. Nature Communications 15: 689. 10.1038/s41467-024-44785-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Floyd MA, Moulton JK, Schuster GA, Parker CR, Robinson J. (2012) An annotated checklist of the caddisflies (Insecta: Trichoptera) of Kentucky. Journal of the Kentucky Academy of Science 73: 4–40. 10.3101/1098-7096-73.1.4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gray HH, Letsinger SL. (2011) A history of glacial boundaries in Indiana. Indiana Geological Survey Special Report 71. Indiana University, Bloomington.

- Green M. (2023) Revision, description, and diagnosis of adult and larval Pycnopsyche spp. (Trichoptera: Limnephilidae) using morphological and molecular methods. PhD dissertation, Clemson University, 436 pp. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations/3286/ [Google Scholar]

- Hilsenhoff WH. (1995) Aquatic insects of Wisconsin. Keys to Wisconsin genera and notes on biology, habitat, distribution and species. Publication No. 3, Natural History Museums Council, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 79 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Houghton DC. (2004) Minnesota caddisfly biodiversity (Insecta: Trichoptera): delineation and characterization of regions. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 95: 153–181. 10.1023/B:EMAS.0000029890.07995.90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houghton DC. (2012) Biological diversity of Minnesota caddisflies. ZooKeys Special Issues 189: 1–389. 10.3897/zookeys.189.2043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houghton DC. (2021) A tale of two habitats: whole-watershed comparison of disturbed and undisturbed river systems in northern Michigan (USA), based on adult Ephemeroptera, Plecoptera, and Trichoptera assemblages and functional feeding group biomass. Hydrobiologia 848: 3429–3446. 10.1007/s10750-021-04579-w [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Houghton DC, DeWalt RE. (2021) If a tree falls in the forest: terrestrial habitat loss predicts caddisfly (Insecta: Trichoptera) assemblages and functional feeding group biomass throughout rivers of the north-central United States. Landscape Ecology 36: 3061–3078. 10.1007/s10980-021-01298-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Houghton DC, DeWalt RE. (2023) The caddis aren’t alright: modeling Trichoptera richness in the northcentral United States reveals substantial species loss. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 11: 1163922. 10.3389/fevo.2023.1163922 [DOI]

- Houghton DC, Holzenthal RW. (2010) Historical and contemporary biological diversity of Minnesota caddisflies: a case study of landscape-level species loss and trophic composition shift. Journal of the North American Benthological Society 29: 480–495. 10.1899/09-029.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Houghton DC, Berry EA, Gilchrist A, Thompson J, MA Nussbaum. (2011) Biological changes along the continuum of an agricultural stream: influence of a small terrestrial preserve and the use of adult caddisflies in biomonitoring. Journal of Freshwater Ecology 26: 381–397. 10.1080/02705060.2011.563513 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Houghton DC, DeWalt RE, Pytel AJ, Brandin CM, Rogers SE, Ruiter DE, Bright E, Hudson PL, Armitage BJ. (2018) Updated checklist of the Michigan (USA) caddisflies, with regional and habitat affinities. ZooKeys 730: 57–74. 10.3897/zookeys.730.21776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houghton DC, DeWalt RE, Hubbard T, Schmude KL, Dimick JJ, Holzenthal RW, Blahnik RJ, Snitgen JL. (2022) Checklist of the caddisflies (Insecta: Trichoptera) of the Upper Midwest region of the United States. ZooKeys 1111: 287–300. 10.3897/zookeys.1111.72345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korecki J. (2006) Revision of the males of the Hydropsychescalaris group in North America (Trichoptera: Hydropsychidae). MS thesis, Clemson University, 211 pp. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/44/ [Google Scholar]

- Lomolino MV. (2004) Conservation biogeography. In: Lomolino MV, Heaney LR. (Eds) Frontiers of Biogeography: New Directions in the Geography of Nature.Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA, 293–296.

- MAFWA (2023) Midwest Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies. https://www.mafwa.org/ [Accessed 25 October 2023]

- Merritt RW, Cummins KW, Berg MB. (2019) An introduction to the aquatic insects of North America, 5th ed. Kendall/Hunt, Dubuque, IA.

- Morse JC, Frandsen PB, Graf W, Thomas JA. (2019) Diversity and ecosystem services of Trichoptera. Insects 10: e125. 10.3390/insects10050125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Moulton SR, Stewart KW. (1996) Caddisflies (Trichoptera) of the interior highlands of North America. Memoirs of the American Entomological Institute 56: 1–313. [Google Scholar]

- Omernik JM. (1987) Ecoregions of the conterminous United States. Annals of the Association of American Geologists 77: 118–125. 10.1111/j.1467-8306.1987.tb00149.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Omernik JM, Griffith GE. (2014) Ecoregions of the conterminous United States: evolution of a hierarchical spatial framework. Environmental Management 54: 1249–1266. 10.1007/s00267-014-0364-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen AK, Morse JC. (2023) Distributional checklist of Nearctic Trichoptera (2022 Revision). Florida A&M University, Tallahassee, FL, 541 pp. http://www.trichoptera.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Ross HH. (1938) Descriptions of Nearctic caddis flies (Trichoptera) with special reference to the Illinois species. Bulletin of the Illinois Natural History Survey 21: 101–183. 10.21900/j.inhs.v21.261 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ross HH. (1944) The caddis flies, or Trichoptera, of Illinois. Bulletin of the Illinois Natural History Survey 23: 1–326. 10.21900/j.inhs.v23.199 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Waltz RD, McCafferty WP. (1983) The caddisflies of Indiana. Agricultural Experimental Station Bulletin 978, Purdue University, Lafayette, IN.

- Williams MF, Houghton DC. (2024) Influence of a protected riparian corridor on the benthic aquatic macroinvertebrate assemblages of a small northern Michigan (USA) agricultural stream. Journal of Freshwater Ecology 39: 1–17. 10.1080/02705060.2024.2312807 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wojtowicz JA. (1982) A review of the adult and larvae of the genus Pycnopsyche (Trichoptera: Limnephilidae) with revision of the Pycnopsychescabripennis (Rambur) and Pycnopyschelepida (Hagen) complexes. PhD Dissertation, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, 292 pp. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/1492/ [Google Scholar]

- Wright DR, Pytel AJ, Houghton DC. (2013) Nocturnal flight periodicity of the caddisflies (Insecta: Trichoptera) in a large Michigan river. Journal of Freshwater Ecology 28: 463–476. 10.1080/02705060.2013.780187 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Summary of our collection data by ecological regions and habitat types

This dataset is made available under the Open Database License (http://opendatacommons.org/licenses/odbl/1.0/). The Open Database License (ODbL) is a license agreement intended to allow users to freely share, modify, and use this Dataset while maintaining this same freedom for others, provided that the original source and author(s) are credited.

David C. Houghton, R. Edward DeWalt

Data type

xlsx

Historical (before 1983), recent (after 2005), and combined species occurrence records for the 219 known Indiana caddisfly species

This dataset is made available under the Open Database License (http://opendatacommons.org/licenses/odbl/1.0/). The Open Database License (ODbL) is a license agreement intended to allow users to freely share, modify, and use this Dataset while maintaining this same freedom for others, provided that the original source and author(s) are credited.

David C. Houghton, R. Edward DeWalt

Data type

xlsx

Specific collection data for the new Indiana state caddisfly species records reported herein

This dataset is made available under the Open Database License (http://opendatacommons.org/licenses/odbl/1.0/). The Open Database License (ODbL) is a license agreement intended to allow users to freely share, modify, and use this Dataset while maintaining this same freedom for others, provided that the original source and author(s) are credited.

David C. Houghton, R. Edward DeWalt

Data type

xlsx

Data Availability Statement

All of the data that support the findings of this study are available in the main text or Supplementary Information.