Summary

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are ubiquitous synthetic chemicals that threaten public health, and serum albumin binding of PFAS represents one major variable influencing PFAS toxicokinetics. In this protocol, we describe a differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF) assay suitable for the rapid determination of the relative binding affinities of serum albumin proteins to different PFAS. Herein, we address common experimental challenges related to PFAS solubility constraints, the high background fluorescence of DSF with serum albumins, and the limitations of using DSF-derived dissociation constants (KD) to quantify PFAS-albumin interactions.

For complete details on the use and execution of this protocol, please refer to Jackson et al.1

Subject areas: Health Sciences, High Throughput Screening, Systems biology, Environmental sciences

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Protocol for the rapid determination of protein-PFAS relative binding affinities

-

•

Instructions for the safe preparation of PFAS chemical stocks

-

•

Guidance for handling PFAS solubility constraints

-

•

Guidance in the interpretation and utility of DSF KD values

Publisher’s note: Undertaking any experimental protocol requires adherence to local institutional guidelines for laboratory safety and ethics.

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are ubiquitous synthetic chemicals that threaten public health, and serum albumin binding of PFAS represents one major variable influencing PFAS toxicokinetics. In this protocol, we describe a differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF) assay suitable for the rapid determination of the relative binding affinities of serum albumin proteins to different PFAS. Herein, we address common experimental challenges related to PFAS solubility constraints, the high background fluorescence of DSF with serum albumins, and the limitations of using DSF-derived dissociation constants (KD) to quantify PFAS-albumin interactions.

Before you begin

This protocol specifically describes the evaluation of human serum albumin (HSA) binding affinity for perfluoro(4-methoxybutanoic) acid (PFMBA, CAS-RN 863090-89-5) using differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF). We have also used this assay to measure bovine, porcine, and rat serum albumin binding affinities for a variety of PFAS congeners and fatty acids, and our assay protocol may be readily adapted to measure PFAS binding with other soluble proteins of interest.2

DSF is an in vitro assay that can be used to measure protein-ligand interactions by evaluating the thermal denaturation of a protein and quantifying changes in thermal stability of the protein when bound to increasing concentrations of a ligand.3,4 Advantages of DSF for measuring protein-ligand interactions include the rapid nature of the assay, requirement of relatively small protein volumes, and widely available quantitative real-time PCR instrumentation.3 The DSF assay and data analysis that we describe here can be completed in a single day.

In this protocol, we address challenges in using DSF to measure binding affinity for serum albumin, which is a protein that exhibits high levels of background fluorescence, and address challenges associated with the evaluation of PFAS chemicals, due to their surfactant nature and solubility constraints. While DSF offers several advantages over other techniques for the measurement of protein-ligand binding, more traditional applications of DSF employ hydrophobic indicator dyes that are incompatible with surfactants, including PFAS.

Guidance for the safe handling of PFAS chemicals is also included in this protocol (before you begin, step-by-step method details). PFAS comprise a diverse class of thousands of different chemical structures, many of which pose safety risks due to their toxicity, reactivity, and/or volatility. Before handling any PFAS chemical, users should read all available chemical hazard information. All PFAS handling should occur in a chemical fume hood, wearing appropriate PPE, and any PFAS chemical stock or container holding PFAS should not be removed from the fume hood unless it is covered and tightly sealed.

Herein, we describe an assay which can be used to calculate DSF dissociation constant (Kd) values for albumin-PFAS binding. DSF Kd values are calculated under different experimental conditions than absolute Kd values derived from equilibrium methods.1,4 Therefore, DSF Kd values are interpreted as relative binding affinities, which allow the direct comparison of HSA binding affinities across different PFAS chemicals generated under the same experimental conditions (expected outcomes, quantification and statistical analysis, limitations). The experimental methods and data analysis described in this protocol have been optimized for compatibility with serum albumin and PFAS, and can be used to fill critical data gaps in understanding protein-PFAS interactions.

Prepare protein and fluorescent dye stocks

Timing: 3 h

Here, we detail buffer and reagent preparation steps necessary before the start of the experiment. If not being used in experiments immediately, store aliquots of these stocks at −20°C. Prior to use in DSF experiments, thaw these aliquots on ice and in the dark.

Note: It is crucial that salt concentrations and pH of buffer solutions, as well as protein stock concentrations, are replicated exactly and are consistent across all experimental wells. Differences in experimental conditions, (i.e.: buffer conditions, experimental pH, and protein/ligand concentrations) can influence protein-PFAS binding affinities.

-

1.Prepare 1× and 2× HEPES-buffered saline (HBS) solution (1 h).

-

a.Prepare 2× HBS buffer in sterile Milli-Q A10 water (18 Ω; < 5 ppb total oxidizable organics). Add reagents and mix for a final concentration of 280 mM NaCl, 50 mM HEPES, and 0.75 mM Na2HPO4. q.s. to final volume with Milli-Q A10 water. Confirm solution pH at 7.4 and adjust with HCl or NaOH if needed.

-

b.Aliquot and label half of the 2× HBS buffer stock and store at 20°C–25°C.

-

c.Dilute the remaining 2× buffer stock to 1× concentration (140 mM NaCl, 25 mM HEPES, 0.38 mM Na2HPO4) by adding an equal volume of Milli-Q A10 water. Reconfirm solution pH at 7.4 after dilution.

-

d.Label the 1× HBS buffer and store at 20°C–25°C.

-

a.

Note: HBS concentrations in the 1× HBS stock will be the final concentrations of HBS in all assay media. The 2× HBS buffer is used to allow the dilution of certain PFAS stocks that require the addition of a chemical solvent to solubilize the PFAS in aqueous solution (Test chemical and positive control preparation, troubleshooting 1).

-

2.Prepare 1 mM human serum albumin (HSA) stock in HBS 1× (1 h).

-

a.Weigh lyophilized HSA for a final concentration of 1 mM HSA. Add HSA in small increments (∼50–80 mg at a time) to HBS 1× in a conical tube and mix on a nutating rocker to reconstitute.Note: For example: For a 5 ml final volume of a 1 mM HSA stock, add 330 mg of HSA, and q.s. to 5 mL with HBS 1×. The typical DSF experiment requires approximately 0.13–0.20 mM HSA.Note: To prevent clumping of the protein stock, we recommend adding the lyophilized HSA in small increments (∼50–80 mg at a time) to a conical tube containing half of the final desired buffer volume (in this example, 2.5 mL HBS 1×). Between HSA additions, mix until completely dissolved on a nutating rocker. After all lyophilized HSA is dissolved in solution, q.s. to the final desired volume with HBS 1×.Note: Use the same protein batch and stock to complete all experiments if possible, to avoid discrepancies that may be caused by differences in protein quality across batches (troubleshooting 2).

-

b.In microcentrifuge tubes, make 500 μL aliquots of 1 mM HSA stock and store at −20°C.

CRITICAL: Do not vortex the protein stock, as this will cause bubbling and protein denaturation.

CRITICAL: Do not vortex the protein stock, as this will cause bubbling and protein denaturation.

-

a.

-

3.GloMelt fluorescent dye preparation (30 min).

-

a.Briefly vortex and centrifuge 200× GloMelt dye stock (Biotium Cat # 33022-1).

-

b.Dilute GloMelt dye from 200× stock to 10× working stock in HBS 1×.Note: GloMelt dye is light sensitive. Keep GloMelt in the dark by covering with foil when thawing and using, as much as possible.

-

c.Create 200 and/or 400 μL aliquots of 10× GloMelt dye working stock (ideal volumes for one or two 96-well plates, respectively) in microcentrifuge tubes and store aliquots at −20°C until use.

-

a.

-

4.Rox [5(6)-Carboxy-X-rhodamine; Cas 198978-94-8] reference dye preparation (30 min).

-

a.Briefly vortex and centrifuge 40 μM Rox dye stock (Biotium Cat # 33022-1).

-

b.Dilute Rox dye from 40 μM stock to 4.0 μM Rox working stock in HBS 1×.Note: Rox dye is light sensitive. Keep Rox in the dark by covering with foil when thawing and using, as much as possible.

-

c.Create 200 and/or 400 μL aliquots of 4.0 μM Rox working stock (ideal volumes for one or two 96-well plates, respectively) in microcentrifuge tubes and store at −20°C until use.Note: Rox dye is an inert passive reference dye, with a fluorescence signal that remains consistent over time in the thermocycler. Dividing GloMelt fluorescence by Rox fluorescence yields a normalized value for data analysis that can decrease replicate variability. Rox should be used as a reference dye when piloting experiments with new proteins. Once performance and reproducibility have been optimized, (i.e. average coefficient of variance across Glo Melt fluorescence readings is less than 5% across replicate wells), the use of Rox becomes optional (quantification and statistical analysis).

-

a.

Prepare test chemical and positive control stocks

Timing: 1 h

Here, we detail chemical stock preparation steps necessary before the start of the experiment. Always handle neat PFAS and solubilized PFAS stocks inside a chemical fume hood.

-

5.PFAS chemical stock preparation (30 min).

-

a.To prepare a 20 mM Perfluoro(4-methoxybutanoic) acid stock (PFMBA, CAS-RN 863090-89-5, MW: 280.04 g/mol), begin with HBS 1× in a conical tube.

-

b.In the fume hood, add PFMBA to the conical tube, for a final concentration of 20 mM PFMBA. Cap the tube, seal lid with parafilm, and then mix on a nutating rocker until homogenous.Note: For example: For a final volume of 5 mL of 20 mM PFMBA stock, add 28 mg of PFMBA, and q.s. to 5 mL with HBS 1×.

CRITICAL: Many PFAS are highly toxic, reactive, and/or volatile, and must be handled with care. Always work with PFAS in a chemical fume hood and with appropriate PPE (gloves, lab coat, goggles, etc.). Read all chemical hazard information for each PFAS congener before handling.Note: With increasing CF2 chain length, PFAS congeners increase in hydrophobicity. For some longer chain PFAS congeners, this may necessitate the use of a polar solvent (methanol, dimethyl sulfoxide, etc.) to dissolve into solution at the desired concentration.Note: Some PFAS congeners may require heating in a water bath to dissolve into solution (troubleshooting 1).

CRITICAL: Many PFAS are highly toxic, reactive, and/or volatile, and must be handled with care. Always work with PFAS in a chemical fume hood and with appropriate PPE (gloves, lab coat, goggles, etc.). Read all chemical hazard information for each PFAS congener before handling.Note: With increasing CF2 chain length, PFAS congeners increase in hydrophobicity. For some longer chain PFAS congeners, this may necessitate the use of a polar solvent (methanol, dimethyl sulfoxide, etc.) to dissolve into solution at the desired concentration.Note: Some PFAS congeners may require heating in a water bath to dissolve into solution (troubleshooting 1). -

c.Store PFMBA stock at 4°C until use.

-

a.

-

6.Positive control compound stock preparation (30 min).Note: Octanoic acid (OA, CAS-RN 124-07-2, MW: 144.21 g/mol) requires a solvent to fully dissolve in aqueous solution.

-

a.To prepare 10 mM OA stock solution, begin with methanol in a conical tube.

-

b.Add OA required for a final concentration of 10 mM (in this example, 14.4 mg OA) and mix on nutating rocker until homogenous.

-

c.If needed, slowly add milliQ H2O and mix until homogenous.

-

d.Slowly add HBS to q.s. to final volume, mixing intermittently, until homogenous.Note: For example: For a final volume of 10 mL of 10 mM OA stock, add 3 mL of methanol, 14.4 mg of OA, 2 mL of Milli-Q A10 water, and 5 mL of 2× HBS, added to the conical tube in that order.Note: For any test or positive control chemical that requires a chemical solvent, a solvent-matched control is necessary on the plate (Plan an experimental plate, troubleshooting 3).

-

e.Store OA stock at 20°C–25°C until use.Note: For this example, we are using OA as the positive plate control, but any chemical that yields replicable results reliably can be used as a positive control.

-

a.

Plan an experimental plate

Timing: 1 h

In this subsection, we describe experimental planning steps to facilitate organized preparation for each experiment. These steps detail the creation of an experimental “plate plan”, which serves as a guide detailing the contents of each well in the 96-well plate, and the generation of a “well-by-well composition” template, which details the volumes of each reagent needed in each well.

-

7.Use a 96-well template to make a “plate plan” for the experimental plate (Figure S1) (30 min).

-

a.Each control and test chemical concentration will be run in triplicate on every plate.

-

b.Controls on all plates will include: no protein controls (NPC; containing Glo, Rox, and HBS), protein-only controls (HSA only; containing Glo, Rox, HSA, and HBS), ligand controls (LC; containing Glo, Rox, HBS, PFMBA or other PFAS test chemical), and positive controls at 3 concentrations (PC1, PC2, PC3; containing Glo, Rox, HSA, OA or another ligand with known affinity for the protein, and HBS).

CRITICAL: When any test or positive control chemical requires a chemical solvent to increase aqueous solubility, include additional solvent controls (SC; containing Glo, Rox, HSA, chemical solvent, and HBS) with matching concentrations of chemical solvent for each corresponding chemical stock.Note: For the PFAS we have evaluated in this DSF assay so far, we have not observed assay interference due to ligand-induced dye activation.1 However, compound-induced dye activation is a common source of DSF assay interference.7 Therefore, when piloting a new PFAS test chemical, include a ligand control (LC; containing the PFAS test chemical, Glo, Rox, and HBS) to confirm that there is no ligand interference in the assay (expected outcomes).

CRITICAL: When any test or positive control chemical requires a chemical solvent to increase aqueous solubility, include additional solvent controls (SC; containing Glo, Rox, HSA, chemical solvent, and HBS) with matching concentrations of chemical solvent for each corresponding chemical stock.Note: For the PFAS we have evaluated in this DSF assay so far, we have not observed assay interference due to ligand-induced dye activation.1 However, compound-induced dye activation is a common source of DSF assay interference.7 Therefore, when piloting a new PFAS test chemical, include a ligand control (LC; containing the PFAS test chemical, Glo, Rox, and HBS) to confirm that there is no ligand interference in the assay (expected outcomes). -

c.Each time protein binding is measured with a new PFAS chemical, run a “screening plate” first to evaluate the proper concentration range necessary for determining the concentration-response relationship of changes in denaturation temperature.Note: On the screen plate, a log (10×) PFAS concentration interval including 100 μM, 300 μM, 1000 μM, 3000 μM, and 10,000 μM concentrations is most often useful.Note: Many PFAS chemicals are limited in aqueous solubility, and thus PFAS concentration ranges on the plate should be adjusted as needed to encompass only concentrations in which the chemical is solubilized.

-

i.After running a screen plate to empirically determine the solubility range of the test chemical under these experimental conditions, run at least two additional “full plates” to capture the full extent of binding (from no change to maximum observed change in protein melt temperature).Note: On these “full plates”, intermediate PFAS concentrations are added to fill in gaps in concentrations and accurately define the concentration response curve. Having a minimum of 3–5 data points at PFAS concentrations between no effect (protein melt temperature is equal to baseline) and maximum effect (plateaued or no change in protein melt temperature with increased PFAS concentrations), is ideal for assessing concentration-response. In many cases, a plateau at high ligand concentrations is not observed, and curve-fitting software is used to estimate the top of the curve during data analysis (quantification and statistical analysis).Note: Inclusion of a “no effect” concentration on the plate is beneficial for curve fitting. If the lowest concentration on the plate (100 μM) causes a significant increase in melting temperature from baseline, analysis at lower concentrations that do not elicit any change in melting temperature will be needed on subsequent plates. A second screen plate with lower concentrations of test compound may be appropriate in this situation.

-

i.

-

a.

-

8.Plan well-by-well composition of plate (30 min).

-

a.Each well in the assay will contain 20 μL of total reaction mix, including 2 μL of GloMelt dye and 2 μL of Rox dye. Wells will also include the volume of protein needed to achieve optimal protein concentration for the assay, and varying volumes of PFAS test chemical or positive control chemical to reach the desired final volume. All wells have a q.s. of 20 μL with HBS 1× (or HBS 1× with the appropriate solvent concentration) (Figure S2).

-

a.

Note: In a following step, we perform serial dilutions to generate 2–4 different working stocks of PFAS (and/or positive control chemical), between 0.5–20 mM, which will be used to accomplish the desired PFAS concentrations across the plate (Reagent preparation).

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Human serum albumin, fraction V, high purity | MilliporeSigma | Cat # 126658; CAS-RN 70024-90-7 |

| GloMelt Dye | Biotium | Cat # 33022-1 |

| Rox reference dye | Biotium | Cat # 33022-1 |

| Octanoic acid | Alfa Aesar | CAS-RN 124-07-2 |

| Perfluoro(4-methoxybutanoic) acid (PFMBA) | Synquest Laboratories | Product # 2121-3-87; CAS 863090-89-5 |

| NaCl | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat #S271-10; CAS-RN 7647-14-5 |

| HEPES | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat # BP310-1; CAS-RN 7365-45-9 |

| Na2HPO4 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat #S374-3; CAS-RN 7558-79-4 |

| Methanol | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat # A454-4; CAS-RN 67-56-1 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| Protein Thermal Shift Software 1.4 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat # 4466038 |

| GraphPad Prism v.10 | GraphPad Software | https://www.graphpad.com/features; RRID: SCR_002798 |

| Other | ||

| StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR system | Applied Biosystems | Cat # 4376600 |

| MicroAmp Fast Optical 96-well Reaction Plate with Barcode, 0.1 mL | Applied Biosystems | Cat # 4346906 |

| MicroAmp optical adhesive film | Applied Biosystems | Cat # 4311971 |

| MicroAmp adhesive film applicator | Applied Biosystems | Cat # 4333183 |

| Eppendorf centrifuge 5804 R | Eppendorf | Cat # 022623508 |

Note: Using the Adhesive Film Applicator is important for the safe handling of PFAS (step-by-step method details).

Materials and equipment

Alternatives: Here we give the recipe for the HEPES-buffered saline solution optimal for experiments measuring serum albumin binding of PFAS. However, if working with another protein of interest, this buffer may be replaced with an alternative temperature-stable buffer with the appropriate ionic strength and pH best suited to the protein and experimental question, which can be determined experimentally.

2× HEPES-Buffered Saline (HBS 2×) Recipe

| Reagent | Final concentration | Amount |

|---|---|---|

| NaCl | 280 mM | 16.4 g |

| HEPES | 50 mM | 11.9 g |

| Na2HPO4 | 0.76 mM | 0.11 g |

| Milli-Q A10 H2O | N/A | q.s. to 1 L |

| Total | N/A | 1 L |

Store at 20°C–25°C until use for up to 12 months.

PCR thermocycling programming

| Steps | Temperature | Ramp rate | Holding time | Cycles |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hold | 37°C | N/A | 10 min | 1 |

| Step and Hold | 37°C–99°C | +0.2°C | N/A | 310 |

| Hold | 99°C | N/A | 15 s | 1 |

Note: A particular challenge working with serum albumins is that these proteins have a high surface hydrophobicity (exposed hydrophobic residues) which contributes to a high level of background fluorescence in the assay. The initial 10 min hold step in this protocol allows for the empirical resolution of this challenge in the assay, as the background fluorescence decreases during this initial pre-cycling hold step. In the “Step and Hold” phase, the frequency of cycles in the assay and the ramp rate are important for protein denaturation and should be replicated exactly.

CRITICAL: The timing of the instrument run may be dependent upon the amount of time that it takes the RT-PCR instrument to complete the run. On our instrument, the heating ramp rate increases at a rate of 0.2°C/s, and our average run takes approximately 140 min to complete. On different RT-PCR instruments, settings may need to be adjusted accordingly to achieve the same or an optimal heating rate.

Step-by-step method details

Reagent preparation

Timing: 2–4 h

We describe all reagents needed to run the assay here. This step includes bringing reagents up to room temperature (20°C–25°C), creating a master mix, and serial dilution of chemicals to working stock concentrations.

-

1.

Remove an aliquot of HSA, GloMelt dye, and Rox reference dye from freezer storage and thaw on ice and in the dark.

CRITICAL: It is important to thaw stocks on ice to preserve the structural integrity of the protein. Thawing reagents on ice will take approximately 1–2 h.

Note: GloMelt and Rox dyes are light sensitive and need to be covered while thawing. An ice bucket with a lid, or a sheet of aluminum foil, works well to cover the aliquots as they thaw.

-

2.Inside a chemical fume hood, mix PFMBA and OA stocks on nutating rocker at 20°C–25°C until homogenous (troubleshooting 1).

-

a.Leave chemicals mixing on nutating rocker until ready to load the plate.

-

a.

-

3.Outside of the fume hood, create a master mix, containing Glo, Rox, HSA, and HBS 1×.Note: Pipetting a master mix into each well, instead of pipetting each component individually, will reduce repetitive pipetting of small volumes, decrease error, and save time.

-

a.Reference the plate plan detailing well-by-well composition to calculate the volume of master mix needed for the experiment (before you begin, Figure S2).

-

b.Calculate the volume of master mix needed by adding the volumes of each component (Glo, Rox, HSA, HBS) needed in each well and multiplying by the number of wells that need master mix to determine the final volume needed.

-

c.Add 10% to the calculated volume of master mix to account for experimental error that may cause loss of material.Note: For example: In our sample plate, each well needs 10 μL of master mix (including 2 μL Glo, 2 μL Rox, 2.5 μL HSA, and 3.5 μL HBS 1×). There are 30 wells that need master mix, and we add 10% to get 33 wells. In total, we need 330 μL of master mix (Figures S1 and S2).

-

d.Thoroughly mix the HSA aliquot (1 mM) by pipetting until homogenous and add the appropriate volume of HSA stock to the master mix tube. Repeat this step with GloMelt dye and Rox dye.

-

e.Pipette or vortex to mix HBS 1× stock and add the appropriate volume of HBS 1× to the master mix tube.

-

f.Thoroughly mix by pipetting once all reagents have been added to the master mix.

-

g.Put master mix on ice and cover to protect from light until ready to load the plate.

Pause point: Master mix can be frozen for use at a later date (troubleshooting 2).

Pause point: Master mix can be frozen for use at a later date (troubleshooting 2).

-

a.

-

4.Prepare serial dilutions of PFMBA stock in fume hood.

-

a.Reference the plate plan detailing well-by-well composition to calculate the volume of each PFMBA working stock needed to load the plate (before you begin, Figure S2).

-

b.Calculate the total volume of each PFMBA stock needed, by adding the volumes of each working stock needed in each well.

-

c.Add 10% to the calculated volume of each PFMBA working stock to account for experimental error that may cause loss of material.Note: If 10% of the final volume of stock needed is less than 5 μL, add 5 μL instead of 10% to ensure there is enough material to complete your experiment.Note: For example: In the sample plate (Figure S1), wells with final concentrations of 100 and 300 μM PFMBA will be loaded with 2 mM working stock of PFMBA. To achieve a final concentration of 100 μM PFMBA in each well, 1 μL of the 2 mM stock is needed, while 3 μL of the 2 mM PFMBA stock are needed to achieve a concentration of 300 μM PFMBA.

-

a.

Thus, to load triplicate wells at each concentration (100 and 300 μM PFMBA), we need enough 2 mM PFMBA stock for 3 wells containing 1 μL (3 × 1 = 3 μL) and 3 wells containing 3 μL (3 × 3 = 9 μL). Therefore, we will need 3 μL + 9 μL = 12 μL of 2 mM PFMBA stock. To account for possible experimental error, we add 5 μL for a total of 17 μL of 2 mM PFMBA stock (Figure S2).

-

d.

Pipette or invert to thoroughly mix the PFMBA stock created in ‘before you begin’ (prepare test chemical and positive control stocks).

-

e.Perform serial dilutions to generate each working stock of PFMBA, diluting each subsequent working stock into labeled microcentrifuge tubes of HBS 1×.

-

i.Mix each dilution thoroughly before drawing from it to generate the next diluted stock.

-

i.

-

f.Leave PFMBA stocks in fume hood at 20°C–25°C until ready to add PFMBA to the plate.Note: Always dilute stocks into HBS 1×. If a chemical solvent was required to make up the experimental PFAS chemical, ensure that there are appropriate solvent-matched controls for each concentration of PFAS stock used on the plate (troubleshooting 3).

-

5.

Prepare serial dilutions of OA stock. Repeat step 4 to generate working stocks of OA.

Load the plate

Timing: 1–2 h

Load the plate with all reagents needed to run the assay. This step directly references the plate plan detailing well-by-well composition from “before you begin” (Figure S2).

-

6.

Place MicroAmp Fast Optical 96-well Reaction Plate into a frozen holding tray or ice bucket.

-

7.

Mix HBS 1× aliquot by vortexing or pipetting. Load each well with the specified volume of HBS 1×, according to the plate plan.

Note: Pay careful attention to details regarding chemical solvents used for each test compound. Make sure solvent concentrations are considered in all controls and experimental wells.

Note: Consider designating different sides/surfaces of the well for each component being pipetted; this may help avoid pipette tip contamination and preserve pipette tips for repeated use.7

-

8.

Thoroughly mix the master mix by pipetting, and load each well with the specified volume of master mix, according to the plate plan.

-

9.

Thoroughly mix the OA aliquots by pipetting, and load each positive control well with the specified volume of OA, according to the plate plan.

-

10.

Thoroughly mix the GloMelt dye aliquot by pipetting, and load each No Protein Control (NPC) and Ligand Control (LC) well with 2 μL of GloMelt dye.

-

11.

Repeat step 10 to load NPC and LC wells with Rox reference dye.

Note: All other wells will be loaded with master mix, and therefore will not need Glo or Rox dyes pipetted separately.

-

12.

Move the plate into the fume hood.

-

13.

Thoroughly mix PFMBA aliquots by pipetting, and ensure that each aliquot does not look cloudy before pipetting into wells on the plate (troubleshooting 1).

-

14.

Load each well with the specified volume of PFMBA, according to the plate plan.

-

15.

Place MicroAmp Optical Adhesive Film over the top of the plate and use the MicroAmp Adhesive Film Applicator to secure it tightly.

CRITICAL: Due to the potential for many PFAS to be toxic and/or volatile chemicals, it is important to use the plate seal applicator, and ensure that the plate is sealed tightly. Do not remove the plate from the fume hood until the plate seal is secure.

-

16.

Centrifuge sealed plate in 96-well plate centrifuge for 20–30 s (troubleshooting 4).

Pause point: The fully loaded and sealed plate can be covered in foil and kept on ice or stored in the refrigerator (4°C) until the plate is run. Plates can be stored for a maximum of 1–2 h.

Run the plate in RT-PCR

Timing: 2 h 30 min

Specific instructions to set up the parameters for the StepOne Real-Time PCR instrument to run the plate are detailed in this step. If using a different RT-PCR system to run these experiments, the relevant PCR thermocycling conditions are shown above (materials and equipment). GloMelt fluorescence (λEx = 468, λEm = 507 nm) is detected using the FAM/SYBR filter, and Rox fluorescence (λEx = 588, λEm = 608 nm) is detected using the ROX channel.

-

17.

Turn on the StepOne Real-Time PCR instrument and place the plate into the instrument.

-

18.

Open the StepOne software and log into the program.

Note: This step may differ depending on the version of software loaded on the PCR instrument. We recommend selecting the “Login as Guest” option when the program opens.

-

19.

Under “Setup” on the homepage, select the “Advanced Setup” button (Figure S3).

-

20.On the left-hand side of the screen, select the “Experimental Properties” tab and choose an experimental name including the protein and PFAS test compound being run.

-

a.Under the “Which instrument are you using to run this experiment?” menu, select “StepOne Plus Instrument (96 wells)”.

-

b.Under the “What type of experiment do you want to set up?” menu, select “Melt Curve”.

-

c.Under the “Which reagents do you want to use to detect the target sequence?” menu, select “SYBR Green Reagents”.

-

d.Under the “Which ramp speed do you want to use in the instrument run?” menu, select “Standard (∼2 h to complete a run)”.

-

a.

-

21.On the left-hand side of the screen, select the “Plate Setup” tab (Figure S4).

-

a.In the “Define Targets and Samples” tab, under “Define Targets” choose “SYBR” from the “Reporter” dropdown list as Target 1.

-

i.Make sure the “None” is selected under the “Quencher” dropdown list.

-

i.

-

b.Under the “Define Samples” section, choose “Add New Sample” to add sample names for each of the triplicate treatments.Note: For example, “NPC” would be the sample name for the no protein control wells, “HSA only” would be the sample name for the protein only control wells, PFMBA100 would be the sample name for wells containing 100 μM PFMBA, etc.

-

c.At the top of the “Plate Setup” page, select the “Assign Targets and Samples” tab. Assign each specified sample name to the corresponding wells outlined on the 96-well plate plan created in “before you begin” (Figure S5).

-

d.Highlight the 3 NPC wells and under the “Assign Target(s) to the Selected Wells” section select “Assign -> Task: N” to designate these wells as negative controls.

-

e.Highlight all remaining wells and under the “Assign Target(s) to the Selected Wells” section select “Assign -> Task: U” to designate these wells as unknowns or test wells.

-

f.In the bottom left-hand corner, under the “Select the dye to use as the passive reference” section, choose “ROX” from the dropdown menu.

-

a.

-

22.On the left-hand side of the screen, select the “Run Method” tab (Figure S6).

-

a.Edit the default parameters in the box labeled “Melt Curve Stage” to define the parameters for the assay.

-

i.Select the “Step and Hold” option at the top of the box.

-

ii.If the default protocol on PCR instrument has more than 2 steps, delete steps until there are only 2 remaining.

-

iii.For step one, set an initial hold step at 37°C for 10 min

-

iv.For step 2, select a +0.2°C step and hold ramp profile from 37°C-99°C (which increases the temperature at 0.2°C increments and holds until all measurements are taken). Add a final hold step at 99°C for 15 s.

-

i.

-

b.Directly underneath the “Graphical View” tab, change the “Reaction Volume Per Well” to 20 μL.

-

a.

-

23.

Double check all parameters to ensure that all instructions have been followed. Then select the “Run” tab on the left-hand side of the screen and click the green “Start Run” button.

Note: After inputting the run method settings into the RT-PCR program, the settings can be saved as a template on the thermocycler for future use.

Note: A prompt will appear to save the experimental file before the run can be started.

-

24.

Ensure that the StepOne RT-PCR tray rises to secure the plate and that the countdown timer begins at the top of the screen to the left of the words “Run Status”, to confirm that the run has been successfully started.

Note: The experimental run should take ∼2 h.

Pause point: After running the plate, there is an option to pause until ready to analyze the data.

-

25.Save the experimental file in the StepOne program and export the data (troubleshooting 2). For users with a different PCR instrument, export the raw RFU data from both the FAM/SYBR and ROX filters.

-

a.Select “Export” at the top of the screen, and check the boxes titled “Sample Setup, Raw Data, Results, and Multicomponent data” under the “Export Properties” tab.

-

b.Select “One File” in the dropdown menu under the “Export Properties” tab.

-

c.To the right of “Export File Name:”, type a name to save the file under (ideally containing the date, protein, and PFAS chemical(s) on the plate). To the right of “Export File Location:” select “Browse” and choose a file location to save the data.

-

d.Navigate to the “Customize Export” tab, and to the right of “Customize:” select “Multicomponent Data” from the dropdown menu. In the “Organize Data” section, select “Across Columns”. Select all boxes for wells on the plate that contained reaction mix.

-

e.Select “Start Export” in the bottom right corner of the window.

-

f.Once the data has been successfully exported, select “Close Export Tool”. Save the analysis file, by selecting “File -> Save”, before closing the StepOne program.

-

a.

Expected outcomes

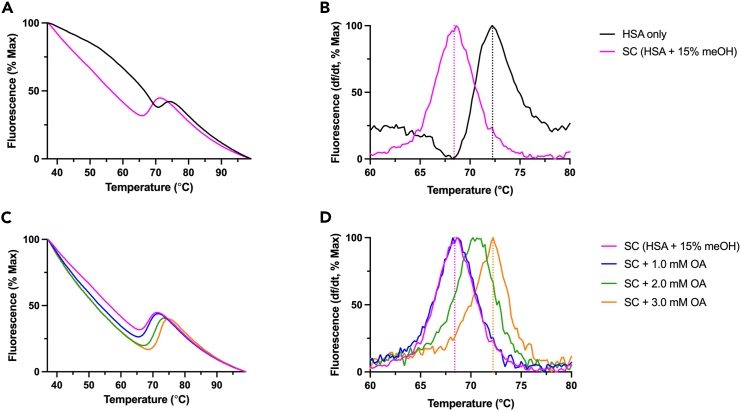

In this DSF assay, measuring HSA binding to PFMBA, results should demonstrate a stabilization of the protein with increasing concentrations of the experimental ligand as demonstrated by an increase in protein melting temperature with increasing concentrations of ligand in the well (Figure 1). Graphs shown in (Figure 1) represent expected results for raw fluorescence curves (Figures 1A and 1C) and first derivative curves (Figures 1B and 1D), depicting HSA binding to PFMBA. In some iterations of this assay, with different soluble proteins and/or PFAS chemicals, destabilization of the protein may also be observed with high concentrations of the ligand (troubleshooting 5). In some rare cases, certain ligands can cause a ligand-induced destabilization of the protein, which would result in a decrease in protein melting temperature with increasing concentrations of ligand in the well.3,8

Figure 1.

Results of DSF measurement of HSA binding to PFMBA

Graphs depict (A) the fluorescence of HSA (0.2 mM) only, and HSA with increasing concentrations of PFMBA from 0.5 to 8.0 mM, normalized to the percentage maximum fluorescence and plotted as a function of temperature from 37°C to 99°C, and (B) first derivative of fluorescence curves shown in (A), normalized to percent maximum fluorescence and plotted as a function of temperature from 37°C to 99°C, (C) the fluorescence of HSA alone and HSA with increasing concentrations of PFMBA from 0.5 to 8.0 mM, normalized to the percentage maximum fluorescence and plotted as a function of temperature from 70°C to 90°C, and (D) first derivative of fluorescence curves shown in (C), normalized to percent maximum fluorescence and plotted as a function of temperature from 70°C to 90°C. Melting temperatures increase with increasing concentrations of PFMBA from 0.5 to 8.0 mM PFMBA. Concentrations of PFMBA in each treatment are denoted by increasing wavelength of color from magenta to red, and defined in the figure legend. In first derivative curves (B and D), melting temperature is defined as the peak in fluorescence (change in fluorescence/change in temperature), represented by a dotted line in the first (HSA only) and final (HSA + 8.0 mM PFMBA) curves.

Similarly, when measuring HSA binding to the control compound OA, results should demonstrate a stabilization of the protein with increasing concentrations of OA (Figure 2). Graphs shown in (Figure 2) represent expected results for raw fluorescence curves (Figures 2A and 2C) and first derivative curves (Figures 2B and 2D), depicting HSA interactions with the chemical solvent in the solvent control treatment (SC), and HSA binding to the positive control (PC) ligand, OA. Ligands that are used as positive controls (i.e.: OA) should be compounds that have been analyzed in preliminary binding studies with the protein of interest, and ΔTm values for the three tested PC concentrations should match those preliminary results. Any ΔTm values that differ by 1°C or more than the expected value for that concentration of PC are failed controls. PC failure can look different depending on the source of the error, but may indicate issues such as failure to thoroughly mix reagents before pipetting, bubbles in the well, pipetting error, etc.

Figure 2.

Results of DSF measurement of HSA binding to positive control ligand OA

Graphs depict (A) the fluorescence of HSA (0.2 mM) only in black, and the solvent control (SC) representing HSA with 15% meOH in magenta, normalized to the percentage maximum fluorescence and plotted as a function of temperature from 37°C to 99°C, and (B) truncated first derivative of fluorescence curves shown in (A), normalized to percent maximum fluorescence and plotted as a function of temperature from 60°C to 80°C, (C) the fluorescence of the SC and SC with increasing concentrations of OA from 1.0 to 3.0 mM, normalized to the percentage maximum fluorescence and plotted as a function of temperature from 37°C to 99°C, and (D) truncated first derivative of fluorescence curves shown in (C), normalized to percent maximum fluorescence and plotted as a function of temperature from 60°C to 80°C. Melting temperatures increase with increasing concentrations of OA, from 1.0 to 3.0 mM OA. Concentrations of OA in each treatment are denoted by increasing wavelength of color from magenta to orange, and defined in the figure legend. In first derivative curves (B and D), melting temperature is defined as the peak in fluorescence (change in fluorescence/change in temperature), represented by a dotted line in the first (SC) and final (SC + 3.0 mM OA) curves.

In wells that include a chemical solvent to dissolve a ligand, the inclusion of the solvent can result in the destabilization of the protein, demonstrated by a decreased melting temperature of the solvent control compared to the protein only control (Figures 2A and 2B). Our previous work has shown that the destabilization of serum albumin by up to 30% methanol in HBS (or up to 5.0 M dimethyl sulfoxide) does not alter the final ΔTm or DSF Kd values.1

Expected results for both no protein controls (NPC) and ligand controls (LC) are very low levels of fluorescence intensity across the plate, at less than 5% of the fluorescence seen in HSA only controls. Fluorescence intensity above this 5% threshold would be indicative of failed NPC or LC controls. It is not uncommon for readings from NPC wells to report negative RFU values. Fluorescence profiles for NPC and LC wells should appear as a flat line, or a line with a slight negative slope. Any discernable pattern of change over time (i.e.: curved pattern of increase and decrease of fluorescence seen in wells containing protein) would also be indicative of a failed NPC or LC control. If impactful ligand-dye interactions exist for a specific ligand, we anticipate fluorescence would be significantly altered in LC controls, potentially above the 5% threshold, but these curves should still exhibit minimal change with increasing temperature and no characteristic pattern or curve. In our experience, ligand-dye interactions that impact fluorescence readings have not been observed for any PFAS ligands tested. Unlike other applications of the DSF assay which most often employ SYPRO Orange indicator dye to interact with hydrophobic regions of the protein, the GloMelt dye employed in our assay responds to an alteration in the micro-viscosity upon protein-ligand binding, and is therefore less likely to cause interference in the DSF assay protocol we describe here.3,9

Raw DSF data produced by this protocol with HSA (and other serum albumins) exhibit relatively high levels of initial background fluorescence (Figure 1A). While this background fluorescence is high, the raw data should exhibit a clearly defined melting transition (Figure 1C), and first derivative data should exhibit a clearly distinguishable peak (Figures 1B and 1D). If raw data do not include a clearly defined melting transition, please refer to (troubleshooting 2). In this protocol, we describe methods that have been optimized for compatibility with serum albumins and PFAS chemicals, and describe a modified data analysis protocol to empirically resolve challenges pertaining to the high background fluorescence of HSA when calculating the Tm (quantification and statistical analysis).

The high initial fluorescence typical in this protocol differs from standard DSF results, in which initial background fluorescence at low temperatures is relatively low (see Biotium protocol for more details). The high initial fluorescence seen in this protocol is likely related to the surface hydrophobicity of human serum albumin (and other homologous serum albumins), which is comprised mainly of alpha-helices (∼67%), and contains multiple binding sites.10 Proteins that contain high surface hydrophobicity, or hydrophobic residues that are exposed in the protein’s native state,4,11 or proteins that have high alpha-helical propensity,12,13,14 may exhibit increased initial background fluorescence in the DSF assay. This high background signal necessitates the use of additional data analysis steps, which are discussed in (quantification and statistical analysis).

Replicate wells of the same experimental treatment should be closely aligned with one another, exhibiting similar melt profiles (Figure 3A). Occasionally, triplicate wells for an experimental condition can display high replicate variability (Figures 3B and 3C). High replicate variability could be an indication of several different problems, including pipetting error, failure to thoroughly mix reagents, solubility issues, and/or bubbles in one or more experimental wells. Statistical analysis of variability across experimental replicates described herein is necessary for the identification of any experimental outliers for removal (quantification and statistical analysis; troubleshooting 6).

Figure 3.

Raw fluorescence of triplicate samples can display high replicate variability

(A) Graph depicts good replicate results with similar melt profiles.

(B) Graph depicts replicate wells in which fluorescence profiles do not align closely across replicates, and it is likely that one or more of the replicates may be an outlier.

(C) Graph depicts replicate wells in which the fluorescence profiles align well for 2 of the 3 replicates, whereas the third replicate (in blue) does not align well and is likely an outlier. In all cases, replicate wells should always be evaluated to determine if there are any experimental or statistical outliers.

When calculating DSF Kd values, it is important to remember that these values are not absolute binding affinity values and therefore cannot be directly compared to published Kd values calculated using other methods, such as equilibrium dialysis. Published Kd values for serum albumin binding of PFAS vary by orders of magnitude (10-2 to 10-6 M) for individual PFAS chemicals across studies, due to differences in experimental conditions and techniques that influence the binding relationship.1,15,16 In general, while still within the range of previously published Kd values, DSF Kd values derived from ΔTm data tend to represent lower binding affinities than Kd values derived from other methods.1,4,17 The fact that DSF Kd values reflect lower affinity binding is attributed at least in part to the fact that DSF Kd values are calculated across a range of protein melting temperatures, as opposed to determination at a single lower temperature.1,4,17 Therefore, it is important to interpret DSF Kd values only as relative HSA-PFAS binding affinities or in comparison to other PFAS congeners run in this assay (limitations).

Quantification and statistical analysis

To begin data analysis, assess the quality of the data, and determine the melting temperatures (Tm) of the protein across the different experimental conditions, as well as the ΔTm between each experimental condition and its respective control. If using the StepOne Plus RT-PCR instrument, we recommend using the Protein Thermal Shift software (V.1.4) for determining the Tm and ΔTm values. The Tm of the protein is defined as the temperature at which the maximum increase in fluorescence occurs, or the maximum change in fluorescence over change in time (df/dt), the temperature at which half of the protein sample is denatured.1,3 To use the Protein Thermal Shift software to quantify the data, upload the .eds file from the StepOne Plus RT-PCR instrument into the program and follow the steps outlined in the protocol provided by Applied Biosystems to analyze the results, and to calculate the ΔTm values representing the change in melting temperature between the native protein and the PFAS-bound protein at each PFAS concentration (see Applied Biosystems protocol for more details). Utilize the “Replicate Results” functionality of the analysis software to determine if any replicate values are outliers that need to be removed from the final analysis. If you do not have access to the Protein Thermal Shift Software, ΔTm values can be calculated manually, using the raw fluorescence (RFU) data exported from the RT-PCR instrument.1 Here, we detail the major steps required to successfully calculate Tm and ΔTm values, which are most relevant for users without the Protein Thermal Shift software, which completes these steps for the user. Due to the high initial background fluorescence observed with HSA, we recommend data transformation, truncation, smoothing, and normalization steps to aid in the determination of the protein Tm value .

-

1.Analyze raw fluorescence (RFU) data for outliers.

-

a.For users analyzing data manually, we recommend calculating the coefficient of variation (%CV = SD/mean x 100) across triplicate wells for each treatment group, for all RFU readings on the plate.

-

i.Across all readings from replicate wells, triplicate wells with an average CV of 5% or higher, or maximum CV is 15% or higher, should be investigated for outliers.

-

i.

-

a.

Note: Triplicate wells should be closely aligned and exhibit a similar melt profile (Figure 3A; troubleshooting 6). If triplicate wells of an experimental condition yield a high CV value that could be indicative of an outlier, users need to statistically evaluate the Tm of those wells to determine whether any of the replicates are truly outliers. If none of the replicate wells show the same fluorescence profile or experimental errors were recorded, then all three may need to be removed as outliers and run again on another plate (Figure 3B). If two of the triplicate wells show similar profiles, then the remaining replicate may need to be removed as an outlier (Figure 3C). If the Tm of a sample replicate is more than three standard deviations away from the average Tm of all other wells of that experimental condition, then the replicate is considered a statistical outlier and should be removed from final analyses.

Note: A minimum of 4 replicate ΔTm values, across a minimum of 2 experimental plates, should be included in final DSF Kd and EC50 calculations.

-

2.

Transform initial RFU data (Figure 4A) by calculating first derivative data (change in fluorescence divided by change in time or df/dt) across all datapoints in the RFU dataset (Figure 4B).

-

3.

After transformation, truncate the first derivative data to remove background fluorescence and highlight the protein melting region of interest (Figure 4C).

-

4.

Smooth the data transformed and truncated data using the Savitzky-Golay or similar method (Figures 4C and 4D), and normalize the data to percentage maximum fluorescence (Figure 4D).18

Note: For example, to calculate df/dt for each experimental well, take the RFU value from PCR cycle 2 and subtract the RFU from PCR cycle 1, and divide that number by the change in temperature between these 2 readings (0.2°C) to obtain the df/dt. Repeat this across all PCR readings for all experimental samples.

Note: Transformation of the data to the first derivative is very important to clearly determine the melting temperature. Data truncation establishes a baseline of low background fluorescence to highlight the “peak” of the derivative curve that represents the Tm of the protein. Smoothing and normalization steps aid in removing noise in the data. Failure to truncate, smooth, or normalize data could result in difficulty determining the protein Tm, and could yield errors in Tm calculation.

-

5.

Calculate Tm values for each sample, by identifying the temperature at which there is the greatest df/dt value (change in fluoresence per unit time; Figure 4D).

-

6.

Calculate ΔTm values by subtracting the Tm value of the control treatment (HSA alone or the matched solvent control) from each experimental treatment Tm value (Figure 4D).

Figure 4.

Determination of ΔTm values from raw fluorescence (RFU) data

Graphs depict (A) the fluorescence (RFU) of HSA only in black, and HSA with 8.0 mM PFMBA in magenta, plotted as a function of temperature from 37°C to 99°C, (B) the first derivative of fluorescence curves shown in (A), plotted as a function of temperature from 37°C to 99°C, (C) truncated first derivative of fluorescence curves shown in (B), smoothed using the Savitzky-Golay method, and plotted as a function of temperature from 60°C to 90°C, and (D) truncated and smoothed first derivative of fluorescence curves shown in (C), normalized to the percentage maximum fluorescence and plotted as a function of temperature from 60°C to 90°C. Melting temperature is defined as the peak in df/dt fluorescence, represented by a dotted line in (A) and (D).

After calculating Tm and ΔTm values for all PFAS concentrations on the plate (for a minimum of 2 independent plates), GraphPad Prism or alternative softwares can be used to determine binding affinity. We recommend the use of GraphPad Prism software for the calculation of DSF Kd and EC50 values with DSF data, as this is the most straightforward and established way to complete this analysis.1,4 Vivoli et al. (2014) describes how to conduct this data analysis in GraphPad Prism, in a well-written and detailed protocol, which can be referenced for more details.4 Further, Vivoli et al. (2014) thoroughly details different equations and parameters for data analysis that should be explored to determine the best binding model that most appropriately fits the collected data.4 In this protocol, we use the single site ligand binding model described in Vivoli et al. (2014), as this binding model has most often resulted in the best fit to our experimental binding data.1,2,4 However, it is critical to evaluate different binding model equations, to determine which equation yields the best fit to the collected data. Here we detail data analysis steps for GraphPad Prism users, however, if GraphPad Prism is not available, these analysis steps could be readily adapted to develop scripts in R or Python to complete these nonlinear regression analyses.

-

7.Input DSF ΔTm results into GraphPad Prism program.

-

a.Create an XY table, with “Numbers” selected under “Options X” and “Enter 6 replicate values in side-by-side columns” selected under “Options Y”.

-

i.If you have run more than two full plates with samples in triplicate, enter the correct number of replicate values to reflect the numbers of samples.

-

i.

-

b.In the X column, enter each molar concentration of PFAS from the experimental plates.

-

c.In the Y columns, enter the corresponding replicate ΔTm values for each molar concentration of PFAS.

-

a.

-

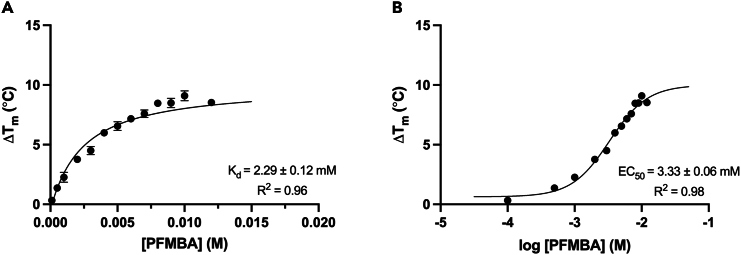

8.Plot ΔTm values against the concentration of PFAS in each well, and use non-linear regression modeling to calculate a DSF dissociation constant (Kd) (Figure 5A).

-

a.Select ΔTm data and choose “Analyze”, and under “XY analyses” select “Nonlinear regression (curve fit).

-

b.Under the “Model” tab, in the top left-hand corner of the screen, select the dropdown next to the “+” option to select “Create new equation”.

-

c.Enter a name for the equation, and define Y according to the single-site ligand binding model published by Vivoli et al. (2014), as follows:

-

a.

Note: In this equation, P = protein concentration, Kd = dissociation constant, Top = melting temperature at infinite ligand concentration, and Bottom = baseline protein melting temperature (no ligand concentration).

Note: The value for P needs to be defined by the user in GraphPad Prism.

Note: Analyze the resulting curve fit to determine if this binding model is correct for the data. If the R2 value of the curve fit is less than 0.90, this may indicate that another model may be more appropriate for the data.

-

9.

Perform a Log10 transformation on the X values (PFAS concentrations) in the dataset.

-

10.Using the log-transformed data, fit a concentration-response curve to calculate an EC50 value for protein-PFAS binding (Figure 5B).1

-

a.The GraphPad Prism preset equation, a 4-parameter variable slope model, entitled “log(agonist) vs. response – Variable slope (four parameters)”, should be used for the curve fitting.

-

a.

Note: Evaluating the success of the automated curve-fitting software is always necessary. The modeling software will automatically estimate the top of the curve. Occasionally, empirically attaining the plateau portion of the curve may not be possible, due to chemical solubility restraints and other factors. If the software-estimated top of the curve seems like an unrealistic value, this type of result may suggest that there are not enough data points collected to properly fit the curve, and may require additional data collection. The most reliable EC50 calculations will result from curves that contain at least 3–5 PFAS concentrations in the slope portion of the curve. An R2 value of 0.9 or greater is indicative of a good curve fit to the data.

Figure 5.

Determination of DSF Kd and EC50 values from ΔTm data

Graphs depict (A) DSF-derived ΔTm values of HSA, as a function of the molar concentration of PFMBA. A non-linear regression curve is fitted to DSF data to calculate DSF Kd values. In (B), DSF-derived ΔTm values of HSA are plotted as a function of the log10 transformed molar concentration of PFMBA. A non-linear regression curve is fitted to these data to calculate EC50 values.

Limitations

The DSF Kd values generated with this assay can only be interpreted as relative binding affinities, as opposed to absolute binding affinities, and cannot be directly compared to the absolute Kd values generated using other methods.1,9 DSF-derived Kd values are distinctly different from most other Kd calculations, which experimentally determine absolute Kd values at a single temperature.4,9 As a result, DSF Kd values tend to represent lower binding affinities than Kds generated using other methods (including equilibrium methods), which is attributed at least in part to the fact that DSF Kd values are calculated at the protein melting temperature and across a temperature range as opposed to determination at a single experimental temperature.1,4,9,17

Calculated binding affinities for HSA binding of individual PFAS congeners often vary widely (by several orders of magnitude) across studies using different methods, due to differences in the experimental conditions and techniques used to determine binding affinity.4,16,19,20,21,22 Differences in experimental conditions (i.e.,: temperature, pH, buffer conditions, protein or ligand concentrations, etc.) across different methods used to derive absolute Kd values, such as equilibrium dialysis, also lead to serious challenges in the comparison of binding affinities across studies.16,23,24,25,26,27,28 Therefore, it is important to note that while DSF Kd values are generally lower than the absolute binding affinities calculated using traditional methods, the DSF Kd values are within the wide range of published binding affinities for serum albumin binding to PFAS.1,2,4,16,17,29,30,31 Due to the fact that Kd values for albumin-PFAS binding cannot be directly compared across most studies, due to these differences in experimental parameters, Kd values are most informative when interpreted as “relative binding affinities”, and interpretations should be focused on comparison to rank-order values or values derived using the same experimental procedure.

The DSF assay provides unique benefits relative to other methods in that it is rapid, low-cost, and uses widely available laboratory equipment.3,4,8,9 In general, the DSF assay is also compatible with automation and high-throughput formats, and therefore there is the potential for this assay to be scaled up as a high-throughput approach in 384-well format. However, it is critical to interpret DSF Kd values only as relative binding affinity values. This careful application allows the rapid comparative assessment of protein binding affinities across diverse PFAS ligands, to strengthen our understanding of toxicokinetics for 1000s of PFAS chemicals in which basic physiochemical properties currently remain undefined.32

The applicability of this DSF assay is restricted to water-soluble PFAS. It is not possible to evaluate protein binding affinities to PFAS congeners that are insoluble in aqueous solutions with DSF. In addition, PFAS chemicals with limited aqueous solubility may not be compatible with this assay, if solubility constraints prevent the analysis of binding across a concentration range in which a binding affinity can be confidently determined (for example, PFAS congeners with carbon chain lengths longer than C12 are incompatible with the assay).1 Further, the structural integrity of proteins can be disrupted by high concentrations of experimental ligand or certain solvents (i.e.: dimethyl sulfoxide).33 As such, PFAS congeners that require high concentrations of chemical solvents may not be compatible with this assay if the solvent is present at a concentration high enough to disrupt protein structure.

In addition to ligand solubility, this DSF assay requires a soluble protein of interest. The ideal protein for this assay will be stable in aqueous solution, contain a compact and globular structure, and will often consist of structural domains that contain a hydrophilic surface and hydrophobic core. If the protein lacks this globular structure, or lacks hydrophobic components capable of generating a robust fluorescent signal, the assay likely will not be compatible with that protein (see Biotium protocol for more details).

Raw RFU data derived using these DSF methods is not amenable to other standard Tm calculation protocols, due to the relatively high levels of background fluorescence seen with this protocol. Therefore, it is important to follow the data handling and preprocessing steps in the assay protocol to most accurately determine the melting temperatures for each protein of interest.

In the calculation of EC50 values using this protocol, it is important to note that these calculations are most accurate when experimental data are available for the complete concentration/response curve (beginning with a concentration of PFAS in which there is no observable change in melting temperature from baseline, and ending with concentrations in which there is a plateau in the maximum observed change in melting temperature). In scenarios in which the “top” of the curve (maximum ΔTm value) is not reached within the solubility range of the test chemical, standard built-in functionality of the curve-fitting software is used to estimate the top of the curve. This estimation allows for the most accurate prediction of the comparative EC50 value under these conditions, but final calculations made with estimated values yield increased uncertainty and are likely to be less accurate than an EC50 value calculated from a complete curve. The calculation of EC50 values using this protocol should be applied only to PFAS chemicals in which sufficient data can be collected across an appropriate range of concentrations to yield a reliable EC50 curve, as described in (quantification and statistical analysis).

The DSF assay for albumins is limited in that it does not yield ligand binding site-specific resolution and is therefore unable to inform about the binding site(s) to which the ligand is bound. There is ambiguity regarding the number of binding sites in which any single PFAS congener is bound by albumin. A limited number of experimental and predictive studies report different numbers of HSA binding sites in which different PFAS congeners can interact, with varying binding affinities.15,30,34 Therefore, as discussed in (quantification and statistical analysis), it is important that protocol users evaluate different modeling equations representing different binding scenarios to identify the equation that yields the best fit for the experimental dataset.4

Troubleshooting

Problem 1: PFAS stock appears cloudy

If the PFAS chemical stock appears cloudy after mixing on the nutating rocker for 30 min to 1 h, the chemical is likely coming out of solution in your mixture (Figure 6; before you begin).

Figure 6.

Representative images of a clear, homogenous PFAS stock and a cloudy, out-of-solution PFAS stock

Potential solution

Heat the stock in a water bath at 37°C until homogenous. If the stock is still cloudy after 30 min to 1 h of heating, heat can be increased to expedite the process. Be sure to check the melting point of the chemical before heating, to ensure that you keep the incubation temperature below the melting point for that chemical. The EPA CompTox Chemicals Dashboard is a good resource to check melting points (https://comptox.epa.gov/dashboard/).35 After heating, thoroughly mix the stock again before aliquoting for experimental use.

Problem 2: Indistinguishable unfolding transition in protein only controls

The concentration of protein that yields the optimal signal-to-noise ratio needs to be optimized in preliminary experiments for each protein of interest in this assay before measuring the binding affinity of that protein to PFAS. Different proteins will have a different optimal concentration for the assessment of protein-PFAS binding. If after initial protein optimization, the protein appears to have low fluorescence signal (relative to background) on the plate, it is possible that there is a problem with the quality of the protein batch (Figure 7; before you begin) or it is not compatible with the assay.

Figure 7.

Graphs depict an example of a protein batch which has low signal-to-noise ratio (rabbit serum albumin), in contrast to human serum albumin with adequate signal-to-noise ratio for reliable data analysis in our assay

Graphs depict (A) the raw fluorescence (RFU) of HSA (0.20 mM) in black, and RSA (0.25 mM) in magenta, plotted as a function of temperature from 37°C to 99°C, and (B) the fluorescence curves shown in (A), normalized to the percentage maximum fluorescence, as a function of temperature from 37°C to 99°C.

Potential solution

When possible, use the same batch or stock of the protein of interest, ordered from one company (the same lot if possible), for all experiments to avoid discrepancies caused by differences in protein quality across batches. If ordering a new batch or lot of protein, order the same product from the same company, and run a new protein optimization plate with the new stock to confirm that the baseline melting temperature matches the initial stock, and to determine what concentration of protein is required to optimize signal-to-noise ratio for this batch. We have commonly found different Tm values depending on albumin purification method, likely due to incomplete removal of endogenous fatty acids from “essentially fatty acid free” albumin.

If protein stocks have not changed, it is possible that protein structural integrity may have been degraded by freeze-thaw cycles. To prevent this issue, create one-time use aliquots of small volumes of the protein. If there is leftover protein to be saved at the end of an experiment, mark the tube to indicate it has gone through a freeze-thaw cycle. Throw away protein aliquots after 3 freeze-thaw cycles, or less if the protein of interest degrades rapidly. Don’t forget to thaw protein on ice to preserve structural integrity.

Problem 3: Ligand binding results in an unexpected decrease in protein melting temperature

If protein-ligand binding results in an atypical decrease in the protein melting temperature, this may be caused by failure to appropriately match experimental wells to their appropriate solvent controls when calculating ΔTm values (before you begin). In rare cases, ligand binding can destabilize the protein structure; if confirmed, the absolute value of the “backward” shift in Tm can be used to calculate Kd.

Potential solution

When running a plate in which chemical solvents have been used to increase the aqueous solubility of one or more ligands, carefully document the chemical solvent concentrations in each well, and ensure that the appropriate solvent-matched controls are run in triplicate wells on the plate. As depicted in Figure 2A, chemical solvents can cause a slight destabilization of the protein. When analyzing data and calculating ΔTm values, refer to your notes to ensure that the correct solvent-matched control Tm values are being utilized in these calculations.

Problem 4: Bubbles in wells after centrifuging the plate

Bubbles can appear in wells due to pipetting error at any step during the process, which can interfere with the assay fluorescence readings (step-by-step method details).

Potential solution

Look at the plate after centrifuging to ensure that there are no bubbles in the wells. If bubbles are present, centrifuge the plate for longer (recommended 1–3 min) to attempt to disrupt them. If bubbles are still present after centrifuging again, note which wells contain bubbles in a lab notebook and evaluate results for exclusion from final analysis.

Problem 5: Protein destabilization at high molar concentration of PFAS

PFAS are surfactants, and protein interactions with high concentrations of PFAS (or solvents such as dimethyl sulfoxide) have the potential to disrupt protein structure. If proteins increase in stability with increases in PFAS concentration, followed by a subsequent decrease in stability of the protein at high molar concentrations of PFAS (e.g., 10,000 μM), the protein may be disrupted by the high PFAS concentration (expected outcomes).

Potential solution

If these issues are detected at high concentrations of PFAS, the destabilizing concentrations of PFAS should be removed from the dataset. Concentrations of PFAS approaching the threshold of destabilization should be added to subsequent plates, to determine where the maximum shift occurs before destabilization, and those ΔTm values should be used to model the maximum change in melt temperature or the top of the curve.

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Scott M. Belcher (smbelch2@ncsu.edu).

Technical contact

Technical questions on executing this protocol should be directed to and will be answered by the technical contact, Scott M. Belcher (smbelch2@ncsu.edu).

Materials availability

This study did not generate any new unique reagents or materials.

Data and code availability

This study did not generate or analyze any dataset or code.

Acknowledgments

We would like to sincerely thank Dr. Thomas Jackson for his critical review and feedback on the manuscript.

Research reported in this publication was supported by grant 2022-FLG-3807 from the North Carolina Biotechnology Center and by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award number T32ES007046. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author contributions

S.M.B. conceptualized the original experimental design and methodology. S.M.B. and H.M.S. devised the experimental strategy. H.M.S. performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the original draft. S.M.B. and H.M.S. contributed to manuscript writing and review and approval of the final draft.

Declaration of interests

The methods described herein are part of US patent application number 17/704825 that was filed with the patent office by NC State University on 2022-09-29 for characterization of protein binding to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances.

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xpro.2024.103386.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Jackson T.W., Scheibly C.M., Polera M.E., Belcher S.M. Rapid characterization of human serum albumin binding for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances using differential scanning fluorimetry. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021;55:12291–12301. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.1c01200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Starnes H.M., Jackson T.W., Rock K.D., Belcher S.M. Quantitative cross-species comparison of serum albumin binding of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances from five structural classes. Toxicol. Sci. 2024;199:132–149. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfae028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Niesen F.H., Berglund H., Vedadi M. The use of differential scanning fluorimetry to detect ligand interactions that promote protein stability. Nat. Protoc. 2007;2:2212–2221. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vivoli M., Novak H.R., Littlechild J.A., Harmer N.J. Determination of protein-ligand interactions using differential scanning fluorimetry. JoVE. 2014;91 doi: 10.3791/51809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liberatore H.K., Jackson S.R., Strynar M.J., McCord J.P. Solvent suitability for HFPO-DA (“GenX” parent acid) in toxicological studies. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2020;7:477–481. doi: 10.1021/acs.estlett.0c00323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang C., McElroy A.C., Liberatore H.K., Alexander N.L.M., Knappe D.R.U. Stability of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in solvents relevant to environmental and toxicological analysis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022;56:6103–6112. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.1c03979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu T., Hornsby M., Zhu L., Yu J.C., Shokat K.M., Gestwicki J.E. Protocol for performing and optimizing differential scanning fluorimetry experiments. STAR Protoc. 2023;4 doi: 10.1016/j.xpro.2023.102688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vedadi M., Niesen F.H., Allali-Hassani A., Fedorov O.Y., Finerty P.J., Jr., Wasney G.A., Yeung R., Arrowsmith C., Ball L.J., Berglund H., et al. Chemical screening methods to identify ligands that promote protein stability, protein crystallization, and structure determination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:15835–15840. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605224103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gao K., Oerlemans R., Groves M.R. Theory and applications of differential scanning fluorimetry in early-stage drug discovery. Biophys. Rev. 2020;12:85–104. doi: 10.1007/s12551-020-00619-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.He X.M., Carter D.C. Atomic structure and chemistry of human serum albumin. Nature. 1992;358:209–215. doi: 10.1038/358209a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ericsson U.B., Hallberg B.M., DeTitta G.T., Dekker N., Nordlund P. Thermofluor-based high-throughput stability optimization of proteins for structural studies. Anal. Biochem. 2006;357:289–298. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2006.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blaber M., Zhang X.J., Matthews B.W. Structural basis of amino acid α helix propensity. Science. 1993;260:1637–1640. doi: 10.1126/science.8503008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akdogan Y., Reichenwallner J., Hinderberger D. Evidence for water-tuned structural differences in proteins: An approach emphasizing variations in local hydrophilicity. PLoS One. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maier R., Fries M.R., Buchholz C., Zhang F., Schreiber F. Human versus bovine serum albumin: A subtle difference in hydrophobicity leads to large differences in bulk and interface behavior. Cryst. Growth Des. 2021;21:5451–5459. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maso L., Trande M., Liberi S., Moro G., Daems E., Linciano S., Sobott F., Covaceuszach S., Cassetta A., Fasolato S., et al. Unveiling the binding mode of perfluorooctanoic acid to human serum albumin. Protein Sci. 2021;30:830–841. doi: 10.1002/pro.4036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.MacManus-Spencer L.A., Tse M.L., Hebert P.C., Bischel H.N., Luthy R.G. Binding of perfluorocarboxylates to serum albumin: A comparison of analytical methods. Anal. Chem. 2010;82:974–981. doi: 10.1021/ac902238u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee I.Y., McMenamy R.H. Location of the medium chain fatty acid site on human serum albumin. Residues involved and relationship to the indole site. J. Biol. Chem. 1980;255:6121–6127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Savitzky A., Golay M.J.E. Smoothing and differentiation of data by simplified least squares procedures. Anal. Chem. 1964;36:1627–1639. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lo M.-C., Aulabaugh A., Jin G., Cowling R., Bard J., Malamas M., Ellestad G. Evaluation of fluorescence-based thermal shift assays for hit identification in drug discovery. Anal. Biochem. 2004;332:153–159. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cimmperman P., Baranauskienė L., Jachimoviciūte S., Jachno J., Torresan J., Michailovienė V., Matulienė J., Sereikaitė J., Bumelis V., Matulis D. A quantitative model of thermal stabilization and destabilization of proteins by ligands. Biophys. J. 2008;95:3222–3231. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.134973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matulis D., Kranz J.K., Salemme F.R., Todd M.J. Thermodynamic stability of carbonic anhydrase: Measurements of binding affinity and stoichiometry using ThermoFluor. Biochemistry. 2005;44:5258–5266. doi: 10.1021/bi048135v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zubrienė A., Matulienė J., Baranauskienė L., Jachno J., Torresan J., Michailovienė V., Cimmperman P., Matulis D. Measurement of nanomolar dissociation constants by titration calorimetry and thermal shift assay – Radicicol binding to Hsp90 and ethoxzolamide binding to CAII. IJMS. 2009;10:2662–2680. doi: 10.3390/ijms10062662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen H., Wang Q., Cai Y., Yuan R., Wang F., Zhou B. Investigation of the interaction mechanism of perfluoroalkyl carboxylic acids with human serum albumin by spectroscopic methods. IJERPH. 2020;17:1319. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17041319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hebert P.C., MacManus-Spencer L.A. Development of a fluorescence model for the binding of medium- to long-chain perfluoroalkyl acids to human serum albumin through a mechanistic evaluation of spectroscopic evidence. Anal. Chem. 2010;82:6463–6471. doi: 10.1021/ac100721e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bischel H.N., MacManus-Spencer L.A., Luthy R.G. Noncovalent interactions of long-chain perfluoroalkyl acids with serum albumin. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010;44:5263–5269. doi: 10.1021/es101334s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]