Abstract

Background

Dysglycemia and insulin resistance increase type 2 diabetes (T2D) and cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk, yet associations with specific glucose-insulin homeostatic biomarkers have been inconsistent. Vitamin D and marine omega-3 fatty acids (n-3 FA) may improve insulin resistance. We sought to examine the association between baseline levels of insulin, C-peptide, HbA1c, and a novel insulin resistance score (IRS) with incident cardiometabolic diseases, and whether randomized vitamin D or n-3 FA modify these associations.

Methods

VITamin D and OmegA-3 TriaL (NCT01169259) was a randomized clinical trial testing vitamin D and n-3 FA for the prevention of CVD and cancer over a median of 5.3 years. Incident cases of T2D and CVD (including cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, stroke, and coronary revascularization) were matched 1:1 on age, sex, and fasting status to controls. Conditional logistic regressions adjusted for demographic, clinical, and adiposity-related factors were used to assess the adjusted odds ratio (aOR) per-standard deviation (SD) and 95%CI of baseline insulin, C-peptide, HbA1c, and IRS (Insulin×0.0295 + C-peptide×0.00372) with risk of T2D, CVD, and coronary heart disease (CHD).

Results

We identified 218 T2D case-control pairs and 715 CVD case-control pairs including 423 with incident CHD. Each of the four biomarkers at baseline was separately associated with incident T2D, aOR (95%CI) per SD increment: insulin 1.46 (1.03, 2.06), C-peptide 2.04 (1.35, 3.09), IRS 1.72 (1.28, 2.31) and HbA1c 7.00 (3.76, 13.02), though only HbA1c remained statistically significant with mutual adjustments. For cardiovascular diseases, we only observed significant associations of HbA1c with CVD (1.19 [1.02, 1.39]), and IRS with CHD (1.25 [1.04, 1.50]), which persisted after mutual adjustment. Randomization to vitamin D and/or n-3 FA did not modify the association of these biomarkers with the endpoints.

Conclusions

Each of insulin, C-peptide, IRS, and HbA1c were associated with incident T2D with the strongest association noted for HbA1c. While HbA1c was significantly associated with CVD risk, a novel IRS appears to be associated with CHD risk. Neither vitamin D nor n-3 FA modified the associations between these biomarkers and cardiometabolic outcomes.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12933-024-02470-1.

Keywords: Insulin resistance, Type 2 diabetes, Cardiovascular disease, Vitamin D, Omega-3 fatty acids

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) are leading causes of morbidity and mortality in the US and globally. Insulin resistance is an important underlying mechanism for these conditions [1]. However, assessing insulin resistance using the gold standard hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp is time- and labor-intensive, has not become adopted in routine clinical practice, and is not recommended for the diagnosis and management of T2D. Prior studies demonstrated that single markers of insulin resistance, such as Homeostatic Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance (HOMA-IR), predict risks of T2D and CVD, independently of glycemic markers such as fasting glucose or HbA1c [2–4]. In addition to insulin measures, C-peptide, a polypeptide produced from the cleavage of proinsulin into biologically active insulin, may also relate to cardiometabolic outcomes [5, 6]. C-peptide levels may better reflect long-term insulin secretion and beta cell function, due to its greater serological stability as a result of minimal hepatic metabolism and constant rate of renal clearance [7]. A recent study suggests that a novel insulin resistance score (IRS) that combines insulin and C-peptide was better able to classify individuals as insulin resistant compared with traditional approaches such as HOMA-IR [8]. Furthermore, assessing simultaneous changes in circulating insulin and C-peptide levels over time may help in identifying individuals who are at elevated cardiometabolic risk due to insulin resistance and provide them with intensive and/or tailored therapies. Existing studies assessing biomarkers of insulin resistance with incident CVD and T2D have been inconsistent, with some showing positive associations [6, 9, 10] whereas others showed no associations [11–13], particularly when adjusting for traditional cardiometabolic risk factors. Thus, additional research into the predictive capabilities of these biomarkers, particularly in a contemporary low-risk general population is warranted.

At the same time, interventions that ameliorate insulin resistance may reduce long-term risk of cardiometabolic diseases. Studies have suggested that supplementation with marine omega-3 fatty acids (n-3 FA) may improve insulin sensitivity, although the effect on risk of incident T2D remains controversial [14]. N-3 FA may reduce the risk of CVD, particularly CHD, as shown in observational studies of fish/omega-3 intake and biomarkers [15, 16], as well as some RCTs of marine omega-3 fatty acid supplementation [17–19]. Additionally, a prior meta-analysis suggested that fish oil supplementation may improve insulin sensitivity among individuals with underlying metabolic dysfunction [20]. Vitamin D has also been identified to improve markers of insulin resistance [21, 22], was associated with lower risk of T2D and CVD in some observational studies [23, 24], and may modestly reduce the incidence of diabetes [25], though its role in cardiovascular outcomes may be relatively limited [26]. One study also showed that vitamin D treatment led to a 50% increased likelihood of reverting from prediabetes to normoglycemia [25]. However, fewer studies have examined the relationship between these interventions among individuals with varying degrees of insulin resistance.

The VITamin D and OmegA-3 TriaL (VITAL, NCT01169259) [17] was a 2 × 2 factorial design randomized controlled trial that investigated the efficacy of n-3 FA (1 g/day) and vitamin D3 (2000 IU/day) for the primary prevention of CVD and cancer. Using a nested case-control design within VITAL, we aimed to assess the association of 4 biomarkers of glucose-insulin homeostasis with the risk of incident cardiometabolic diseases, and whether these associations may be modifiable by the randomized treatments (e.g. vitamin D or n-3 FA). We hypothesized that higher baseline levels of insulin, C-peptide, HbA1c, and the novel IRS would be positively associated with incident CVD, CHD, and T2D, but these associations would be attenuated among participants assigned to active n-3 FA or vitamin D treatment compared to those assigned to placebo.

Methods

Study population

Detailed study protocol and primary findings from VITAL have been published previously and highlighted above [17]. In total, VITAL enrolled 25,871 participants, consisting of men ≥ 50 or women ≥ 55 years of age, who were free of CVD and cancer (except nonmelanoma skin cancer) at baseline. All participants gave written informed consent prior to being enrolled, and ethical approval was provided by the Institutional Review Board of the Mass General Brigham, including for the present analysis.

We designed two nested case-control studies of incident T2D and CVD, respectively, within VITAL. Among individuals who provided blood samples (N = 16,956), we identified 469 confirmed T2D cases and 782 confirmed CVD cases [including 465 incident coronary heart disease (CHD) events]. Risk-set sampling was used to match cases in a 1:1 fashion on age (+/-5 years), sex, and fasting status to controls who were free of these conditions at the time of follow-up. After excluding individuals with missing insulin, C-peptide, or HbA1c values or who were subsequently found to have developed CVD or T2D prior to the time of randomization, 218 T2D cases and 715 CVD cases along with their controls were included.

Biomarker measurements

Participants who agreed to participate in blood collection were each mailed a blood collection kit, including a freezer pack along with an informed consent and were instructed to get their blood drawn at a local healthcare provider’s office or clinical laboratory. Blood samples were shipped overnight within 24 h of venipuncture to the central laboratory in Boston where the samples were centrifuged and separated into the plasma, serum, red blood cells, and buffy coat fractions and stored in nitrogen freezers (− 170 °C) all within 36 h of venipuncture. Samples were stored under these conditions until the time of biomarker measurement. Assays used for the measurement of insulin and C-peptide have been previously described [27]. Briefly, intact insulin and C-peptide were enriched from serum samples using monoclonal antibodies and eluted with a robotic liquid handler. The proteins were then measured using a multiplexed liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry assay. The range of detection for this particular assay ranged from 18 to 1920 pmol/l for insulin and from 36 to 9006 pmol/l for C-peptide, with intra-assay variation being less than 11% for both proteins. Calibration was performed using the World Health Organization (WHO) standard code 83/500 (National Institute for Biological Standards and Control [NIBSC]) and C-peptide (Anaspec). The insulin resistance score (IRS) was calculated using the following equation: IRS = Insulin×0.0295 + C-peptide×0.00372 [8, 10]. The ability of IRS to quantify insulin resistance was confirmed by comparing its discriminatory ability against direct measurement of insulin resistance using a modified version of the insulin suppression test [8]. Glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) was measured on red blood cells using an enzymatic assay on the Abbott Architect c8000 platform. Lipids were measured using standard assays. Biomarker measurements were performed by Quest Diagnostics. Fasting status was determined by self-report and defined as follows: participants who reported time since last meal as < 8 h before blood draw were defined as non-fasting, whereas those who had not eaten for ≥ 8 h before blood draw were defined as fasting. Serum glucose measurements were only available for a small subset of our population, and therefore we could not adjust for this variable in our models nor calculate measures such as HOMA-IR.

Outcome assessment

Participants received follow-up questionnaires at 6 months and 1 year after randomization and annually thereafter to collect information on the new occurrence of medical conditions including T2D. For each participant who reported a new diagnosis of T2D, a supplementary questionnaire was used to collect date of diagnosis, glycemic testing parameters, symptoms at diagnosis, and use of anti-diabetic medications. In addition, written permission was obtained prior to contacting the participant’s healthcare provider for medical records pertaining to the diagnosis. The clinician was also mailed a supplementary questionnaire to confirm disease onset, symptoms, and additional diagnostic testing. The response rate was high with 93.4% of participants who reported incident diabetes responding to either the supplemental questionnaire, providing medical records, or having a physician-completed questionnaire. On the basis of responses to the supplemental questionnaire, 82.0% of those with confirmed T2D reported use of antidiabetic agents. After all medical records and/or supplementary questionnaires were obtained, a study physician, blinded to the randomized treatment assignment, reviewed the records and made a final determination of case status. Confirmation was based upon American Diabetes Association diagnostic criteria [28]. This approach to T2D confirmation has been validated in our previous mail-based clinical trials. Because the vast majority of diabetes diagnosed at age ≥ 50 years is type 2, incident diabetes in VITAL is considered T2D. Individuals who did not have a known diabetes diagnosis at the time of randomization but had a HbA1c of 6.5% or higher were excluded from the analysis. Ascertainment of CVD was described previously [29]. This endpoint was comprised of a composite of non-fatal myocardial infarction (MI), non-fatal stroke, death from cardiovascular causes, and coronary revascularization. Total CHD was comprised of fatal and non-fatal MI and coronary revascularization. Participants who developed one of these conditions had their medical records reviewed centrally by an endpoints committee consisting of physicians blinded to the treatment assignment.

Statistical analyses

Spearman correlation coefficients were calculated to assess the pair-wise correlations between the glucose-insulin biomarkers and BMI among T2D and CVD controls.

We assessed the association between each biomarker and T2D or CVD in per-SD increments. As a sensitivity analysis, we also assessed log-transformed insulin, C-peptide, and IRS biomarkers in per-SD increments given their non-normal distributions. We also analyzed for non-linear associations by categorizing participants into quartiles based on the distribution in the control group, with the lowest quartile as the reference group. We additionally assessed for non-linearity by including a spline term in our model and comparing this model with a linear model using likelihood ratio test. Conditional logistic regression models were used to calculate the adjusted odds ratio (aOR) and 95% confidence interval (CI). Covariates that were controlled for in our models were selected based on their established associations with T2D or CVD from the prior literature. For the T2D analysis, Model 1 included the matching factors (age, sex and fasting status). Model 2 additionally adjusted for race/ethnicity, smoking status, alcohol consumption, systolic blood pressure, HDL cholesterol, family history of T2D, use of antihypertensives, use of lipid-lowering agents, and randomized treatment (omega-3, vitamin D, or placebo). Model 3 additionally adjusted for BMI, whereas Model 4 additionally adjusted for HbA1c (when pertaining to the exposure being insulin, C-peptide, and IRS) and for insulin and C-peptide when pertaining to HbA1c. For the CVD analysis, our covariates were: Model 1: matching factors; Model 2 additionally adjusted for race/ethnicity, smoking status, alcohol consumption, systolic blood pressure, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, diabetes status, family history of CVD, use of antihypertensives, use of lipid-lowering agents, and randomized treatment (omega-3, vitamin D, or placebo); Model 3 additionally adjusted for BMI; Model 4: for insulin, C-peptide, or the IRS, additionally adjusted for HbA1c; for HbA1c, additionally adjusted for insulin and C-peptide. Missing values generally accounted for < 5% of the total data. To maximize the number of participants that can be included in the analysis, multiple imputation with chain equations were performed to account for missing values. We additionally compared these results to when single imputation (using the median value for continuous variables or the reference category for categorical variables) or complete case analysis (i.e. excluding participants who had missing values) were performed.

We additionally calculated the association for per-SD increment in each of the biomarkers with risk of incident T2D or CVD, stratified by randomized treatment, and interactions between baseline biomarker levels with randomized treatment (n-3 FA/vitamin D) on risk of T2D or CVD. P-values for interaction were derived from the cross-product interaction term coefficient (biomarker per-SD increment×binary variable for the assigned treatment) added to the overall multivariable model.

Statistical analyses were conducted using R v3.6.2 (R Project for Statistical Computing) and SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc). Two-tailed P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant, unless otherwise stated.

Results

Participant selection for the present analysis are detailed in Supplementary Fig. 1a and 1b. Baseline characteristics stratified by T2D and CVD case-control status are displayed in Table 1. All four biomarkers, particularly IRS and HbA1c, were higher among individuals who developed T2D compared to controls. CVD cases had a higher prevalence of CVD risk factors as well as medication usage when compared to controls. Additionally, insulin and C-peptide levels were similar in individuals who developed CVD vs. controls; however, HbA1c and IRS were higher in CVD cases.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants by type 2 diabetes or cardiovascular disease case-control status

| Characteristic | Type 2 diabetes | Cardiovascular disease | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | Control | P-value | Case | Control | P-value | |

| N | 218 | 218 | 715 | 715 | ||

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age, y | 65.5 ± 5.9 | 66.1 ± 5.4 | 0.29 | 71.3 ± 8.1 | 70.6 ± 7.5 | 0.09 |

| Men, N (%) | 126 (57.8) | 126 (57.8) | 1.00 | 415 (58.0) | 415 (58.0) | 1.00 |

| Ethnicity, N (%) | 0.07 | 0.77 | ||||

| White | 161 (73.9) | 175 (80.3) | 604 (85.2) | 598 (84.3) | ||

| Black | 51 (23.4) | 33 (15.1) | 78 (11.0) | 87 (12.3) | ||

| Other | 6 (2.8) | 10 (4.6) | 27 (3.8) | 29 (3.7) | ||

| Clinical values | ||||||

| Smoking status, N (%) | 0.09 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Never | 116 (53.2) | 111 (50.9) | 323 (45.8) | 351 (50.0) | ||

| Former | 83 (38.1) | 98 (45.0) | 322 (45.9) | 325 (46.1) | ||

| Current | 19 (8.7) | 9 (4.1) | 60 (8.5) | 26 (3.7) | ||

| BMI, kg/m2 | 31.6 ± 6.1 | 27.3 ± 4.7 | < 0.001 | 28.5 ± 6.3 | 27.6 ± 5.5 | 0.009 |

| Hypertension, N (%) | 141 (65.0) | 119 (54.8) | 0.03 | 487 (68.1) | 417 (58.3) | < 0.001 |

| Prior diabetes, N (%) | 0 | 0 | - | 156 (21.8) | 124 (17.3) | 0.03 |

| Family history of CVD, N (%) | - | - | - | 118 (16.5) | 104 (14.5) | 0.31 |

| Family history of T2D, N (%) | 106 (52.5) | 74 (35.4) | 0.002 | - | - | - |

| Laboratory values | ||||||

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 197.7 ± 40.7 | 207.2 ± 38.8 | 0.02 | 200.2 ± 42.9 | 202.6 ± 39.6 | 0.28 |

| LDL-C, mg/dL | 121.4 ± 34.6 | 127.9 ± 33.4 | 0.05 | 122.4 ± 37.3 | 123.2 ± 33.4 | 0.63 |

| HDL-C, mg/dL | 45.8 ± 14.8 | 54.0 ± 16.9 | < 0.001 | 49.8 ± 17.7 | 53.3 ± 18.4 | < 0.001 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 158.0 ± 87.8 | 126.5 ± 58.9 | < 0.001 | 143.7 ± 84.5 | 132.2 ± 71.6 | 0.007 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 75.5 ± 26.1 | 76.7 ± 23.3 | 0.60 | 71.5 ± 22.6 | 74.1 ± 21.2 | 0.03 |

| Omega-3 index (EPA + DHA), % | 2.5 ± 0.8 | 2.6 ± 0.9 | 0.72 | 2.49 ± 0.8 | 2.57 ± 0.9 | 0.07 |

| 25-hydroxy vitamin D (ng/mL) | 28.0 ± 9.5 | 30.2 ± 11.1 | 0.03 | 30.4 ± 9.6 | 30.7 ± 10.1 | 0.57 |

| Medications | ||||||

| Use of antihypertensives, N (%) | 135 (62.2) | 115 (53.2) | 0.06 | 454 (63.8) | 385 (54.1) | < 0.001 |

| Use of lipid-lowering agents, N (%) | 95 (44.2) | 73 (34.3) | 0.04 | 317 (45.4) | 286 (40.9) | 0.10 |

| Use of hypoglycemic agents/insulin, N (%) | 0 | 0 | - | 130 (18.2) | 105 (14.7) | 0.07 |

| Aspirin use, N (%) | 94 (43.7) | 92 (43.4) | 0.95 | 375 (53.4) | 356 (50.7) | 0.31 |

| Randomized treatment arm | ||||||

| Omega-3 fatty acid, N (%) | 118 (54.1) | 101 (46.3) | 0.10 | 362 (50.6) | 353 (49.4) | 0.63 |

| Omega-3 fatty acid placebo, N (%) | 100 (45.9) | 117 (53.7) | 353 (49.4) | 362 (50.6) | ||

| Vitamin D, N (%) | 114 (52.3) | 94 (43.1) | 0.06 | 340 (47.6) | 354 (49.5) | 0.46 |

| Vitamin D placebo, N (%) | 104 (47.7) | 124 (56.9) | 375 (52.5) | 361 (50.5) | ||

| Glucose-insulin homeostatic biomarkers | ||||||

| HbA1c (%) | 6.0 ± 0.3 | 5.5 ± 0.4 | < 0.001 | 5.9 ± 1.0 | 5.8 ± 0.7 | < 0.001 |

| Insulin, pmol/L, median (IQR) | ||||||

| Fasted > 8 h | 75.7 (48.6-128.5) | 55.6 (27.8–83.3) | < 0.001 | 48.6 (20.8–90.3) | 48.6 (20.8–76.4) | 0.06 |

| Fasted ≤ 8 h | 139.6 (75.7-298.6) | 69.5 (45.6-152.8) | < 0.001 | 83.3 (41.7-173.6) | 83.3 (34.7-187.5) | 0.50 |

| C-peptide, pmol/L, median (IQR) | 725.9 (439.6-1125.5) | 466.2 (306.4–666.0) | < 0.001 | 366.3 (193.1-653.6) | 369.6 (201.2-566.1) | 0.50 |

| Insulin resistance score, pmol/L, median (IQR) | 70.2 (21.2–98.7) | 25.4 (10.5–64.3) | < 0.001 | 23.9 (6.6–76.9) | 17.7 (6.1–60.0) | 0.05 |

BMI: body mass index; BP: blood pressure; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate; HbA1c: glycated hemoglobin, HDL-C: high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

Values are mean ± SD unless otherwise specified

Spearman correlation coefficients among controls showed moderate to strong correlations between insulin, C-peptide, and IRS in the range of 0.6–0.8 (Supplementary Fig. 2a and 2b). On the other hand, each of these biomarkers were only modestly correlated with BMI (0.2–0.3) and weakly correlated with HbA1c (0.1–0.2).

Type 2 diabetes outcome

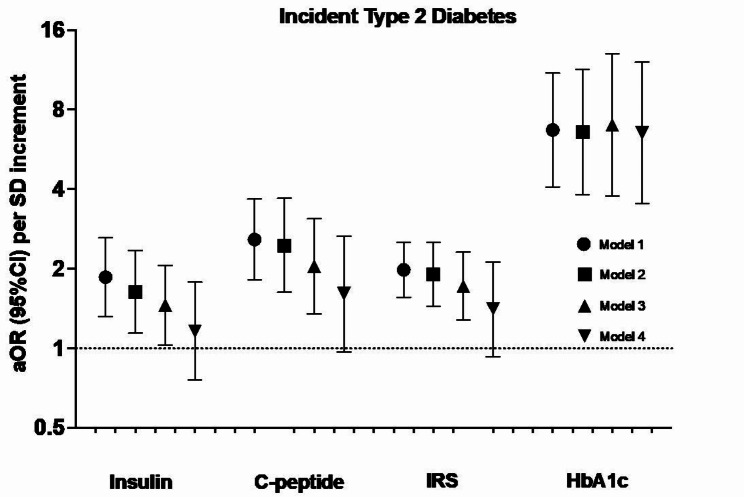

With respect to incident T2D, higher baseline levels of insulin, C-peptide, IRS, and HbA1c were all associated with higher risk, after multivariable-adjustment (Model 3 in Fig. 1). Per-SD increment, the aOR (95%CI) for insulin, C-peptide, IRS, and HbA1c were 1.46 (1.03, 2.06), 2.04 (1.35, 3.09), 1.72 (1.28, 2.31), and 7.00 (3.76, 13.02), respectively, with similar findings in the categorical analyses (Supplementary Table 1). Associations for insulin, C-peptide, and IRS were attenuated after further adjustment for HbA1c and no longer statistically significant (Model 4 in Fig. 1). On the other hand, further adjustment for insulin and C-peptide did not materially alter the association between HbA1c and incident T2D, 6.53 (3.53, 12.10). Associations were similar when assessing per-SD increment of the log-transformed insulin, C-peptide, and IRS biomarkers (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Association between glucose-insulin homeostasis biomarkers and incident type 2 diabetes (N = 218 events) in the VITAL trial. Model 1 includes the matching factors age, sex, and fasting status. Model 2 is additionally adjusted for race/ethnicity, smoking status, alcohol consumption, systolic blood pressure, HDL cholesterol, family history of T2D, use of antihypertensives, use of lipid-lowering agents, and randomized treatment arm (omega-3, vitamin D, or placebo). Model 3 is additionally adjusted for BMI. For insulin, C-peptide, and IRS, model 4 is additionally adjusted for HbA1c. For HbA1c, model 4 is additionally adjusted for insulin and C-peptide. aOR: adjusted odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; HbA1c: glycated hemoglobin; IRS: insulin resistance score

Cardiovascular outcomes

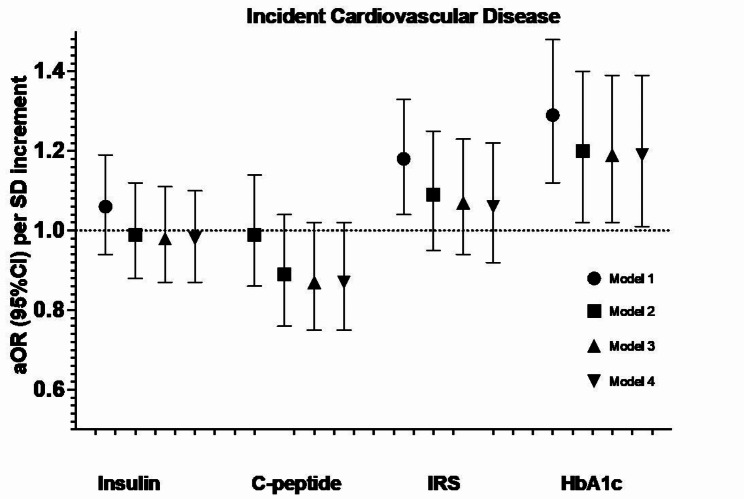

After a median of 5.3 years (range 3.8–6.1) of follow-up, we identified and matched 715 cases of incident CVD (including 423 cases of CHD). After accounting for matching factors (Model 1 in Fig. 2), we found that insulin and C-peptide were not associated with incident CVD, whereas IRS and HbA1c were associated with an increased risk, with aOR (95%CI) of 1.18 (1.04, 1.33) and 1.29 (1.12, 1.48), respectively. Further adjustment for other cardiovascular risk factors attenuated the association for both IRS and HbA1c, with only HbA1c remaining statistically significant (Model 2). This association was not materially altered with further adjustment for BMI (e.g. Model 3) or for insulin and C-peptide (e.g. Model 4). Associations were consistent when the biomarkers were examined categorically (Supplementary Table 2) as well as when insulin, C-peptide, and IRS were log-transformed (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Association between glucose-insulin homeostasis biomarkers and incident cardiovascular disease (N = 715 events) in the VITAL trial. Cardiovascular disease included non-fatal myocardial infarction, non-fatal stroke, and cardiovascular death. Model 1 includes the matching factors, namely age, sex, and fasting status. Model 2 is additionally adjusted for race/ethnicity, smoking status, alcohol consumption, baseline diabetes status, systolic blood pressure, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, family history of cardiovascular disease, use of antihypertensives, use of lipid-lowering agents, and randomized treatment arm (omega-3, vitamin D, or placebo). Model 3 is additionally adjusted for BMI. For insulin, C-peptide, and IRS, model 4 additionally adjusts for HbA1c. For HbA1c, model 4 additionally adjusts for insulin and C-peptide. aOR: adjusted odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; HbA1c: glycated hemoglobin; IRS: insulin resistance score

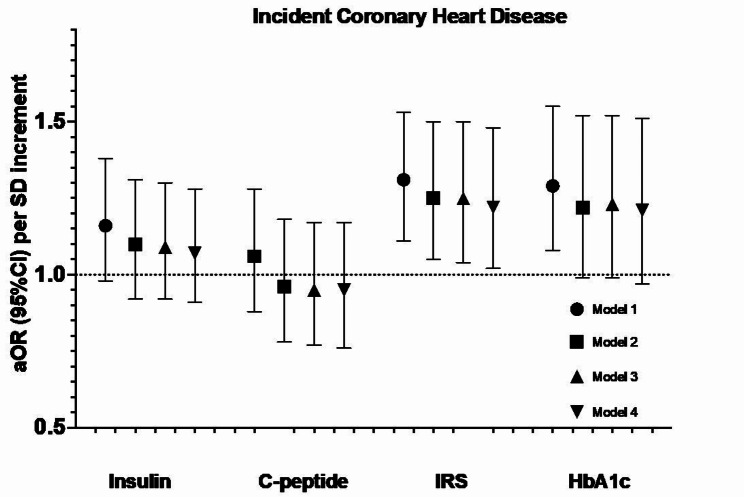

With respect to the CHD outcome, insulin and C-peptide were not associated with incident CHD (Fig. 3). IRS was associated with a higher risk of CHD after multi-variable adjustment, with aOR (95%CI) per-SD increment of 1.25 (1.04, 1.50). This association was not appreciably attenuated with additional adjustment for HbA1c, 1.22 (1.02, 1.48). HbA1c was significantly associated with incident CHD after accounting for matching factors, though this association was attenuated and no longer statistically significant after accounting for other cardiovascular risk factors. We observed similar patterns of associations in the categorical analysis (Supplementary Table 2) and when insulin, C-peptide, and IRS were log-transformed (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

Association between glucose-insulin homeostasis biomarkers and incident coronary heart disease (N = 423 events) in the VITAL trial. Coronary heart disease is defined as the composite of non-fatal myocardial infarction, coronary revascularization, and coronary deaths. Model 1 includes the matching factors, namely age, sex, and fasting status. Model 2 is additionally adjusted for race/ethnicity, smoking status, alcohol consumption, baseline diabetes status, systolic blood pressure, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, family history of cardiovascular disease, use of antihypertensives, use of lipid-lowering agents, and randomized treatment arm (omega-3, vitamin D, or placebo). Model 3 is additionally adjusted for BMI. For insulin, C-peptide, and IRS, model 4 additionally adjusts for HbA1c. For HbA1c, model 4 additionally adjusts for insulin and C-peptide. aOR: adjusted odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; HbA1c: glycated hemoglobin; IRS: insulin resistance score

Sensitivity analysis

To assess the robustness of our findings in light of missing covariates, we compared our main results using multiple imputation to when single imputation or complete case analysis were performed. Associations were broadly consistent irrespective of which approach was used to account for missing values (Supplementary Tables 3–6). Additionally, the inclusion of a spline term to each of our models to test for non-linearity was not statistically significant, suggesting that there was no major deviation from a linear relationship between each of our biomarker-disease associations. When we applied a more stringent P-value cut-off derived using false discovery rate (FDR) correction, all four of the biomarkers were associated with incident T2D in Model 3, whereas only HbA1c retained statistical significance after mutual adjustment (Model 4). On the other hand, none of the biomarkers achieved statistical significance after FDR correction for their associations with incident CVD or CHD.

Interaction with randomized treatment

The interaction term for the randomized treatment arm (e.g. vitamin D, n-3 FA, or placebo) was not statistically significant for any of the four glucose-insulin homeostatic biomarkers that were assessed, with respect to either T2D, CVD, or CHD (Pinteraction>0.05).

Discussion

In the present analysis of two case-control studies nested within VITAL, we found all four of the glucose-insulin homeostatic biomarkers examined were associated with incident T2D after adjusting for demographics, cardiovascular risk factors, medication use, and adiposity. Moreover, we observed that HbA1c was associated with an increased risk of CVD and the novel IRS was associated with an increased risk of CHD. Finally, we did not find evidence that randomized treatment with vitamin D/n-3 FA at the doses examined in the trial significantly influenced their associations with outcomes.

We found that a relatively novel measure of insulin resistance, the IRS, was associated with incident T2D and CHD. Compared to the more commonly used HOMA-IR, the IRS does not utilize fasting glucose. Comparison of the performance of these two measures of insulin resistance is relatively limited. In one study, IRS was shown to be superior for predicting the presence of insulin resistance compared to HOMA-IR, though data on incident cardiometabolic outcomes are not available [8]. Because only a small subset of participants in the current study had fasting glucose measurements, we could not directly compare IRS to HOMA-IR on its utility as a biomarker for insulin resistance. Our findings for IRS are corroborated by a prior study done in the UK that showed that fasting insulin and homeostasis model assessment for insulin sensitivity (HOMA-S) were stronger predictors for incident CHD and stroke, compared to fasting glucose and HbA1c [30].

Our study provides novel insights on the relationship between circulating C-peptide levels and cardiometabolic outcomes, which has been less studied compared to other markers of glucose-insulin homeostasis. In prior studies, C-peptide was associated with increased all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in a non-diabetic US population, independent of baseline glucose or insulin levels [5]. In a Spanish population that was normoglycemic at baseline, higher C-peptide levels predicted incident CHD and MI [31]. On the other hand, in a cohort of Japanese American men, C-peptide was not associated with incident CHD after adjusting for other cardiovascular risk factors [11]. Similar to this latter study, we also did not find an appreciable association between C-peptide levels and incident CVD or CHD. A meta-analysis of cohort studies showed that C-peptide was associated with greater risk of CVD mortality, though with significant heterogeneity (I2 = 81.8%) and was only statistically significant in the US studies and not European studies. The precise mechanism of C-peptide in atherosclerosis and CVD has been debated, as in experimental studies, C-peptide has been shown to demonstrate both pro-atherosclerotic and anti-atherosclerotic properties [32]. The varying associations from prior studies on C-peptide and incident CVD may also be influenced by study design, study population (who may have varying degrees of insulin resistance), duration of follow-up, and degree of statistical adjustment for other cardiovascular risk factors. More studies are warranted to determine the role that elevated C-peptide may play in the development of CVD.

With respect to T2D, a prospective cohort in the Netherlands found that C-peptide was associated with higher risk, independent of glucose or insulin levels [6]. Our present analysis also observed a positive association between C-peptide and incident T2D, which maintained borderline statistical significance after adjusting for HbA1c, whereas we found that circulating insulin levels was attenuated and no longer significantly associated with T2D after adjusting for HbA1c. As alluded to above, this may be due to the ability of C-peptide to better capture long-term insulin secretion and beta cell function, when compared to directly measured insulin, which is subject to greater fluctuations in levels due to hepatic clearance [7]. Future studies are needed to understand the independent role of C-peptide in T2D risk prediction.

Hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia have been implicated as causal risk factors for CVD and CHD [1]. Mendelian randomization (MR) studies have shown that single nucleotide polymorphisms linked to higher fasting glucose and insulin levels are both associated with increased risks of CHD and MI, and less consistently with higher risk of stroke [33], similar to our findings. High insulin levels acts directly or as a compensatory mechanism for underlying insulin resistance to promote the development of endothelial dysfunction and hypertension, atherogenic dyslipidemia, and systemic inflammation, all of which accelerates the development of atherosclerosis even among individuals without hyperglycemia [34]. This was observed in our study, where we noted that further adjustment for HbA1c did not materially alter the association between insulin, C-peptide, and IRS with respect to incident CHD. In contrast, further adjustment for HbA1c tended to attenuate the association between each of these biomarkers and incident T2D. In two prospective cohorts of US men and women, HbA1c was found to be a strong predictor of incident T2D, independent of baseline fasting glucose [35]. More studies are warranted to examine the interplay between these biomarkers to determine their role in long-term T2D and CVD pathogenesis.

The growing global burden of cardiometabolic diseases highlights the importance of discovering low-cost yet effective treatments for insulin resistance, which represents a central risk pathway for these conditions. To our knowledge, our study is among the first to examine the modification of the association between glucose-insulin homeostatic biomarkers with cardiometabolic outcomes by two commonly used dietary supplements within the context of a RCT. We did not find an appreciable effect modification by randomized treatment with vitamin D or n-3 FA at the doses examined. In the overall VITAL study [17], randomization to n-3 FA did not significantly reduce the primary CVD outcome, but significantly reduced total CHD. Moreover, the beneficial treatment effect appeared to be greater among Black individuals compared to Whites, despite similar levels of dietary and circulating n-3 FA [17]. Prior large-scale observational studies consistently found a higher rate of insulin resistance and T2D when comparing Blacks to Whites [36], which may suggest a greater benefit of n-3 FA in individuals with insulin resistance, though additional confirmatory studies are needed.

With respect to T2D, observational studies of dietary fish/n-3 FA intake [37] as well as circulating n-3 FA biomarkers [38] have suggested a lower risk, though existing data from RCTs indicate an overall neutral effect for n-3 FA supplementation [14]. For vitamin D, observational and clinical trials [26] do not support a role for vitamin D in the prevention of CVD. On the other hand, recent MR studies [23] and a meta-analysis of RCTs [25] conducted among individuals with prediabetes support a possible role for vitamin D in the prevention of T2D. Additional well-powered interventional studies among individuals with underlying insulin resistance will be needed to confirm whether these two treatments play a role in the prevention of T2D and CVD.

The strengths of our study include the prospective ascertainment of T2D and CVD cases, nested within a large RCT conducted among a general population in the US, allowing for an examination of the associations of glucose-insulin biomarkers in a contemporary primary prevention setting. Furthermore, we assessed multiple glucose-insulin homeostatic biomarkers simultaneously, allowing for mutual adjustment and comparisons between their associations with cardiometabolic outcomes.

Several limitations warrant mentioning. Due to the observational nature of our study, we cannot rule out residual or unmeasured confounding and are therefore unable to demonstrate causality. However, as mentioned above, our findings are consistent with prior MR studies and lifestyle and pharmacological interventions that reduce cardiometabolic diseases and also improve circulating levels of these glucose-insulin homeostatic biomarkers. Biomarkers of glucose-insulin homeostasis were measured only at one timepoint and changes in these biomarkers over time may influence their associations with cardiometabolic outcomes. A significant proportion of participants in both of the nested case-control studies were not fasting at the time of blood draw, which may have influenced levels of insulin and C-peptide levels and hence the associations we observed, though we have attempted to minimize this by matching the cases and controls on fasting status.

In summary, we observed that all four of the glucose-insulin homeostatic biomarkers examined were associated with incident T2D, whereas HbA1c was associated with incident CVD and a novel marker of insulin resistance, IRS, was associated with incident CHD, even after controlling for other known cardiometabolic risk factors. We did not find vitamin D nor n-3 FA at the doses tested in VITAL modified the associations between these biomarkers and cardiometabolic outcomes. Our study suggests that these biomarkers may be useful to identify individuals at increased cardiometabolic risk, though developing effective treatments that can modify these biomarkers and reduce related cardiometabolic diseases requires further research.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank the VITAL participants and staff for their dedicated and conscientious collaboration. Pharmavite LLC of Northridge, California (vitamin D) and Pronova BioPharma of Norway and BASF (Omacor fish oil) donated the study agents, matching placebos, and packaging in the form of calendar packs. Quest Diagnostics performed the insulin-glucose hemostatic biomarker laboratory measurements at no additional costs to the VITAL study.

Author contributions

FQ, YG, JEM, ADP, and SM were involved in the conception, design, and conduct of the study. YG, CL, and YL performed the statistical analysis. FQ and SM wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors edited, reviewed, and approved the final version of the manuscript. SM is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Funding

The study was funded by the NIH grants R01AT011729, R01CA138962, R01DK112940, R01HL134811, R01HL160799, K24HL136852. The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of this study or the interpretation of the data. The opinions expressed in the manuscript are those of the study authors.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Competing interests

JL, JB, and MJM are Quest Diagnostics employees and/or have stock ownership. SM served as a consultant to Pfizer outside the current work. The other authors declare no relevant conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Frank Qian and Yanjun Guo contributed equally to this work.

Aruna D. Pradhan and Samia Mora contributed equally as senior authors.

References

- 1.Ormazabal V, Nair S, Elfeky O, Aguayo C, Salomon C, Zuniga FA. Association between insulin resistance and the development of cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2018;17(1):122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ruijgrok C, Dekker JM, Beulens JW, Brouwer IA, Coupe VMH, Heymans MW, et al. Size and shape of the associations of glucose, HbA1c, insulin and HOMA-IR with incident type 2 diabetes: the Hoorn Study. Diabetologia. 2018;61(1):93–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kurl S, Zaccardi F, Onaemo VN, Jae SY, Kauhanen J, Ronkainen K, et al. Association between HOMA-IR, fasting insulin and fasting glucose with coronary heart disease mortality in nondiabetic men: a 20-year observational study. Acta Diabetol. 2015;52(1):183–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meigs JB, Porneala B, Leong A, Shiffman D, Devlin JJ, McPhaul MJ. Simultaneous consideration of HbA1c and insulin resistance improves Risk Assessment in White individuals at increased risk for future type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(8):e90–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patel N, Taveira TH, Choudhary G, Whitlatch H, Wu WC. Fasting serum C-peptide levels predict cardiovascular and overall death in nondiabetic adults. J Am Heart Assoc. 2012;1(6):e003152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sokooti S, Kieneker LM, Borst MH, Muller Kobold A, Kootstra-Ros JE, Gloerich J et al. Plasma C-Peptide and risk of developing type 2 diabetes in the General Population. J Clin Med. 2020;9(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Leighton E, Sainsbury CA, Jones GC. A practical review of C-Peptide testing in diabetes. Diabetes Ther. 2017;8(3):475–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abbasi F, Shiffman D, Tong CH, Devlin JJ, McPhaul MJ. Insulin resistance probability scores for apparently healthy individuals. J Endocr Soc. 2018;2(9):1050–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sarwar N, Sattar N, Gudnason V, Danesh J. Circulating concentrations of insulin markers and coronary heart disease: a quantitative review of 19 western prospective studies. Eur Heart J. 2007;28(20):2491–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Louie JZ, Shiffman D, McPhaul MJ, Melander O. Insulin resistance probability score and incident cardiovascular disease. J Intern Med. 2023;294(4):531–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wahab N, Chen R, Curb JD, Willcox BJ, Rodriguez BL. The Association of Fasting Glucose, insulin, and C-Peptide, with 19-Year incidence of Coronary Heart Disease in older Japanese-American men; the Honolulu Heart Program. Geriatr (Basel). 2018;3(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Schmiegelow MD, Hedlin H, Stefanick ML, Mackey RH, Allison M, Martin LW, et al. Insulin resistance and risk of Cardiovascular Disease in Postmenopausal women: a Cohort Study from the women’s Health Initiative. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2015;8(3):309–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jahromi MK, Ahmadirad H, Jamshidi S, Farhadnejad H, Mokhtari E, Shahrokhtabar T, et al. The association of serum C-peptide with the risk of cardiovascular events: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2023;15(1):168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown TJ, Brainard J, Song F, Wang X, Abdelhamid A, Hooper L, et al. Omega-3, omega-6, and total dietary polyunsaturated fat for prevention and treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mozaffarian D. Dietary and policy priorities for cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and obesity: a comprehensive review. Circulation. 2016;133(2):187–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Del Gobbo LC, Imamura F, Aslibekyan S, Marklund M, Virtanen JK, Wennberg M, et al. omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid biomarkers and coronary heart disease: pooling project of 19 cohort studies. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(8):1155–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manson JE, Cook NR, Lee IM, Christen W, Bassuk SS, Mora S, et al. Marine n-3 fatty acids and Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease and Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(1):23–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhatt DL, Steg PG, Miller M, Brinton EA, Jacobson TA, Ketchum SB, et al. Cardiovascular Risk reduction with Icosapent Ethyl for Hypertriglyceridemia. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(1):11–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu Y, Hu FB, Manson JE. Marine omega-3 supplementation and cardiovascular disease: an updated meta-analysis of 13 randomized controlled trials involving 127 477 participants. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8(19):e013543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gao H, Geng T, Huang T, Zhao Q. Fish oil supplementation and insulin sensitivity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lipids Health Dis. 2017;16(1):131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li X, Liu Y, Zheng Y, Wang P, Zhang Y. The effect of vitamin D supplementation on Glycemic Control in type 2 diabetes patients: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Nutrients. 2018;10(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Pramono A, Jocken JWE, Blaak EE, van Baak MA. The effect of vitamin D supplementation on insulin sensitivity: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(7):1659–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu L, Bennett DA, Millwood IY, Parish S, McCarthy MI, Mahajan A, et al. Association of vitamin D with risk of type 2 diabetes: a mendelian randomisation study in European and Chinese adults. PLoS Med. 2018;15(5):e1002566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang R, Li B, Gao X, Tian R, Pan Y, Jiang Y, et al. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and the risk of cardiovascular disease: dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;105(4):810–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang Y, Tan H, Tang J, Li J, Chong W, Hai Y, et al. Effects of vitamin D supplementation on Prevention of type 2 diabetes in patients with prediabetes: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(7):1650–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barbarawi M, Kheiri B, Zayed Y, Barbarawi O, Dhillon H, Swaid B, et al. Vitamin D supplementation and Cardiovascular Disease risks in more than 83000 individuals in 21 randomized clinical trials: a Meta-analysis. JAMA Cardiol. 2019;4(8):765–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taylor SW, Clarke NJ, Chen Z, McPhaul MJ. A high-throughput mass spectrometry assay to simultaneously measure intact insulin and C-peptide. Clin Chim Acta. 2016;455:202–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.American Diabetes Association Professional, Practice C, American Diabetes Association Professional, Practice C, Draznin B, Aroda VR, Bakris G, Benson G, et al. 2. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2022. Diabetes Care. 2022;45(Suppl 1):S17–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manson JE, Cook NR, Lee IM, Christen W, Bassuk SS, Mora S, et al. Vitamin D supplements and prevention of cancer and cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(1):33–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lawlor DA, Fraser A, Ebrahim S, Smith GD. Independent associations of fasting insulin, glucose, and glycated haemoglobin with stroke and coronary heart disease in older women. PLoS Med. 2007;4(8):e263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cabrera de Leon A, Oliva Garcia JG, Marcelino Rodriguez I, Almeida Gonzalez D, Aleman Sanchez JJ, Brito Diaz B, et al. C-peptide as a risk factor of coronary artery disease in the general population. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2015;12(3):199–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alves MT, Ortiz MMO, Dos Reis G, Dusse LMS, Carvalho MDG, Fernandes AP, et al. The dual effect of C-peptide on cellular activation and atherosclerosis: protective or not? Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2019;35(1):e3071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goodarzi MO, Rotter JI. Genetics insights in the relationship between type 2 diabetes and coronary heart disease. Circ Res. 2020;126(11):1526–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adeva-Andany MM, Martinez-Rodriguez J, Gonzalez-Lucan M, Fernandez-Fernandez C, Castro-Quintela E. Insulin resistance is a cardiovascular risk factor in humans. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2019;13(2):1449–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leong A, Daya N, Porneala B, Devlin JJ, Shiffman D, McPhaul MJ, et al. Prediction of type 2 diabetes by hemoglobin A1c in two community-based cohorts. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(1):60–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Howard G, Wagenknecht LE, Kernan WN, Cushman M, Thacker EL, Judd SE, et al. Racial differences in the association of insulin resistance with stroke risk: the reasons for geographic and racial differences in stroke (REGARDS) study. Stroke. 2014;45(8):2257–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen GC, Arthur R, Qin LQ, Chen LH, Mei Z, Zheng Y, et al. Association of oily and nonoily fish consumption and fish oil supplements with incident type 2 diabetes: a large population-based prospective study. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(3):672–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Qian F, Ardisson Korat AV, Imamura F, Marklund M, Tintle N, Virtanen JK, et al. n-3 fatty acid biomarkers and incident type 2 diabetes: an individual participant-level pooling project of 20 prospective cohort studies. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(5):1133–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.