Abstract

Background

Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) intervention has been widely used to reduce the burden of symptoms in cancer patients, and its effectiveness has been proven. However, the effectiveness of MBSR on depression, anxiety, fatigue, quality of life (QOL), posttraumatic growth (PTG), fear of cancer recurrence (FCR), pain, and sleep in breast cancer patients has not yet been determined. This study aims to determine the role of mindfulness-based stress reduction therapy in patients with breast cancer.

Objectives

The objective was to systematically review the literature to explore the effect of MBSR on anxiety, depression, QOL, PTG, fatigue, FCR, pain, stress and sleep in breast cancer patients. To explore the effect of 8-week versus 6-week MBSR on the 9 indicators. Data were extracted from the original RCT study at the end of the intervention and three months after baseline to explore whether the effects of the intervention were sustained.

Methods

We conducted searches on PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, and China National Knowledge Infrastructure from inception to November 2023. Eligible studies included randomized controlled trials of breast cancer patients who received mindfulness stress reduction intervention, reporting outcomes for anxiety, depression, fatigue, QOL, PTG, FCR, pain, stress, and sleep. Two researchers conducted separate reviews of the abstract and full text, extracted data, and independently evaluated the risk of bias using the Cochrane ‘Bias Risk Assessment tool’. The meta-analysis utilized Review Manager 5.4 to conduct the study, and the effect size was determined using the standardized mean difference and its corresponding 95% confidence interval.

Results

The final analysis included 15 studies with a total of 1937 patients. At the end of the intervention, the interventions with a duration of eight weeks led to a significant reduction in anxiety [SMD=-0.60, 95% CI (-0.78, -0.43), P < 0.00001, I2 = 31%], depression [SMD=-0.39, 95% CI (-0.59, -0.19), P = 0.0001, I2 = 55%], and QOL [542 participants, SMD = 0.54, 95% CI (0.30, 0.79), P < 0.0001, I2 = 49%], whereas no statistically significant effects were found in the intervention with a duration of six weeks. Similarly, in 3 months after baseline, the interventions with a duration of eight weeks led to a significant reduction in depression and QOL, however, no statistically significant effects were found at the 6-week intervention. MBSR led to a significant improvement in PTG at end of intervention [MD = 6.25, 95% CI (4.26, 8.25), P < 0.00001, I2 = 0%] and PTG 3 months after baseline. We found that MBSR reduced the fatigue status at end of intervention, but had no significant effect on fatigue status 3 months after baseline. There was no significant difference in improving pain, stress, and FCR compared to usual care.

Conclusions

In terms of effects on QOL, anxiety, depression, and fatigue, the 8-week MBSR intervention showed better results than the 6-week MBSR intervention. The intervention of MBSR on PTG was effective, and the effect lasted until 3 months after baseline. Future studies could further identify the most effective intervention components in MBSR.

Trial registration

PROSPERO registration number: CRD42023483980.

Keywords: Mindfulness-based stress reduction, Breast cancer, Quality of life, Posttraumatic growth, Fear of cancer recurrence, Pain, Sleep, Meta-analysis

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most diagnosed cancer and the leading cause of cancer death in women, accounting for 23% of total cancer cases and 14% of cancer deaths [1]. The treatment of breast cancer has changed dramatically, resulting in improved survival rates. However, because most treatment methods destroy both tumor and normal cells, economic pressure, and individual fear of death, breast cancer patients usually suffer from significant physical and psychological issues, such as stress, depression, anxiety, worry, despair, fatigue [2, 3].

Despite improvements in treatment and prognosis, many cancer survivors face the possibility of cancer recurrence. For certain individuals, uncertainty leads to heightened fear of cancer recurrence (FCR), which is defined as the “fear, worry, or concern about cancer returning or progressing” [4]. FCR is one of the most common, persistent, and devastating psychological problems in breast cancer patients [5]. In addition to the fear of recurrence, cancer patients face severe sleep and pain distress. The negative effects of these cancers can reduce the quality of life (QOL) [6]. Therefore, looking for targeted interventions to reduce FCR, improve physical and mental health, and improve QOL has become a key issue that breast cancer patients need to solve.

As positive psychology research increases, many studies emphasize not only the negative effects of traumatic events but also the positive changes they trigger, such as post-traumatic growth (PTG). Studies [7] have shown that PTG can not only help cancer patients improve their cognition and coping levels, and improve their mental health, but also enhance their confidence in fighting the disease, and improve their treatment compliance. Therefore, the search for interventions that can improve PTG has positive implications.

Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) is developed by Professor Jon Kabat-Zinn [8] at the University of Massachusetts Medical School. MBSR is designed to help individuals consciously focus on the present moment and be curious, open, and receptive to the experience of the moment in a non-judgmental way [9, 10]. Studies [11] have shown that MBSR can reduce anxiety and depression in cancer patients. Complications such as missing breasts due to surgery can lead to noticeable physical and appearance changes in breast cancer patients compared to patients with other cancers. This obvious change in physical appearance can make patients feel their body image is poor, and the psychological status of breast cancer patients is further damaged. Breast cancer patients need psychological intervention to reduce the discomfort caused by the disease, therefore, this study aims to explore the efficacy of MBSR in breast cancer patients.

Studies have currently shown that the MBSR program is effective and safe in improving the anxiety [12] and depression [13] in breast cancer patients. However, some studies have reported conflicting results from MBSR anxiety [13] and depression [12] in breast cancer. The reason for the controversy may be that, in previous MBSR meta-analyses, it has not been specified whether the data collected after the intervention was short-term or long-term, and how long the intervention lasted was unclear. In addition, some new RCTs have emerged [14–18]. In addition, to our knowledge, only a few clinical trials have consistently found positive effects of MBSR on QOL, pain, sleep, FCR and PTG in breast cancer patients. Therefore, research on the value of MBSR in breast cancer patients is necessary. The review aims to quantify the impact of MBSR on breast cancer patients. The objective was to systematically review the literature to explore the effect of MBSR on anxiety, depression, QOL, PTG, fatigue, FCR, pain, stress, and sleep in breast cancer patients. To explore the effect of 8-week versus 6-week MBSR on the 9 indicators. Data were extracted from the original RCT studies at the end of the intervention and three months after baseline to explore whether the effects of the intervention were sustained.

Method

This project has been prospectively registered in the PROSPERO system evaluation database, registration number: CRD42023483980.

Literature search criteria

We systematically searched PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, China National Knowledge Infrastructure. The search terms used were related to breast cancer (key words: breast cancer, breast neoplasms, breast tumors, cancer of breast, human mammary carcinoma; Mesh term: breast neoplasm); mindfulness-based stress reduction (key words: mindfulness-based stress reduction, MBSR, mindfulness-based intervention; Mesh term: mindfulness-based stress reduction).

Inclusion criteria

(1) Study type: RCT of breast cancer patients using MBSR; (2) Study population: Breast cancer patients aged 18 years and above, regardless of cancer stage; (3) The intervention group was treated with MBSR (meditation, zazen, body scanning, mindfulness yoga, etc.), while the control group was treated with routine nursing and waiting control; (4) Meta-analysis indicators: stress, anxiety, depression, fatigue, QOL, pain, sleep, FCR and PTG.

Exclusion criteria

(1) Republished articles; (2) Articles with incomplete data; (3) The article lacks the original data.

Quality evaluation and data extraction

The Cochrane Handbook 5.1.0 criteria were used to independently evaluate the quality of seven aspects of the included literature. Information was extracted from the included studies. Literature quality evaluation and data extraction were carried out independently by two researchers.

Data analysis

RevMan 5.3 software was used for statistical analysis of the data. χ2 test was used to analyze the heterogeneity among the included studies. If P ≥ 0.1 and I2 < 50%, fixed-effect model was used. If P < 0.1 and I2 ≥ 50%, random effects model was used and subgroup analysis was used to explore the source of heterogeneity. If the outcome indicators were continuous variable data and were measured by the same tools, weighted mean difference (WMD) and 95% CI were used. Otherwise, standardized mean difference (SMD) and 95% CI were used. In addition, sensitivity analysis was performed for each study by one-by-one elimination method to evaluate the stability of the meta-analysis results.

Subgroup analysis was conducted for length of the intervention (i.e., eight weeks or six weeks) to explore which length of the intervention was most beneficial for patients with breast cancer.

Results

Research identification and selection

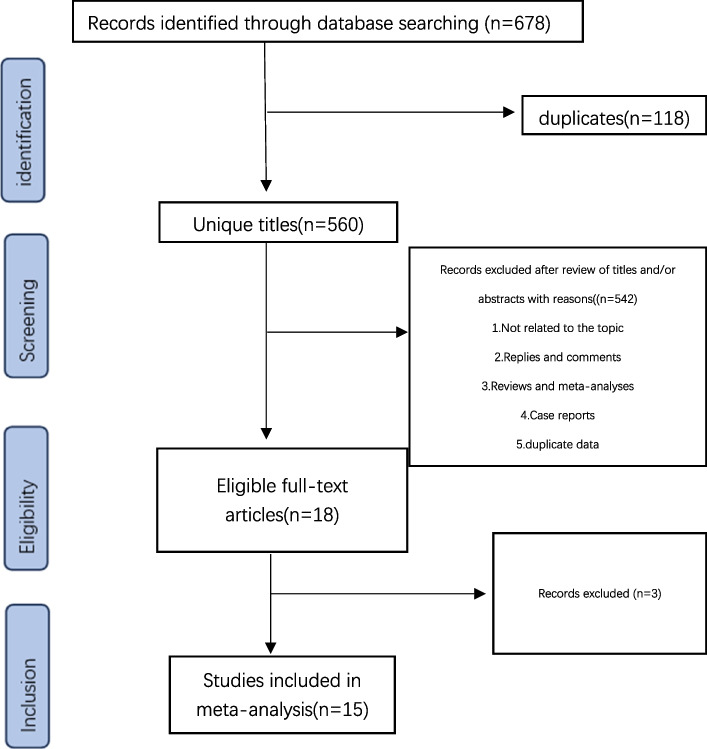

According to Fig. 1 and 678 studies were found initially. Among them, 118 were duplicates, and 542 were omitted after reviewing their titles and abstracts. Upon further examination of the full texts, 3 studies were discarded, while 15 studies [14–28] were deemed suitable for inclusion in the current meta-analysis.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram for search and selection of the included studies

Characteristics of studies

The characteristics of the included studies are summarized in Table 1. These studies included a total of 2032 participants, with 1019 in the intervention group and in 1013 the control group. Of these, five were conducted in the US, five in China, and the other five from UK, Canada, Denmark, Sweden, Iran. Patients with breast cancer were aged 48.37 years with diagnosis stages of 0 to 3. HADS, POMS, STAI-S, SCL-90r, BAI, SAS, and CEC were employed to evaluate anxiety prevalence among study participants. HADS, POMS, CES-D, BDI, SDS, and PHQ-9 were employed to evaluate depression prevalence among study participants. FACT-B, and SF-36 were employed to evaluate quality of life among study participants. PTGI was employed to evaluate posttraumatic growth levels among participants. FSI, BFI, RPFS-CV, POMS, and MFSI were employed to evaluate fatigue prevalence among participants. BPI, BCPT, and SF-36 were employed to evaluate pain prevalence among participants. QLACS and CARS were employed to evaluate fear of cancer recurrence prevalence among participants. PSS was employed to evaluate stress prevalence among participants. PSQI was employed to evaluate sleep levels among participants.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studies included in this meta-analysis

| Author year, country | sample | age | cancer stage | range of study duration | CG | Time point | Outcome variables | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Henderson 2012 [14] USA | 53/52 | 20–65 | N-II | Not reported | UC | 8week, 16week | FACT-B, CEC | |

| Hoffman 2012 [15] UK | 114/115 | 49.0 ± 9.26/50.1 ± 9.14 | N-III | 2005–2006 | Wait-listed control/UC | 8week,12wk | POMS, FACT-B | |

| Wurtzen 2013 [16] Denmark | 168/168 | 53.9 ± 10.1/54.4 ± 10.5 | I-III | Jun 2007-Jul 2009 | UC | 6mon, 12mo | SCL-90r, CES-D | |

| Lengacher 2014 [17] USA | 40/42 | 58.2 | N-III | Mar 2006 to Jul 2007 | UC | 6week | STAI, CES-D, SF-36, PSS, CARS | |

| Bower 2015 [18] USA | 39/32 | 46.1(28.4–60)/47.7(31.1–59.6) | N-III | Not reported | UC | baseline,6 and 12 wk. | PSS, CES-D, FSI, PSQI, BCPT, QLACS | |

| Lengacher 2016 [19] USA | 152/147 | 56.6 | N-III | Apr 2009-Mar2013 | UC | 6week,12 week | BPI, FSI, CES-D, STAI-S, CARS, SF-36 | |

| Kenne 2017 [20] Sweden | 62/52 | 57.2 ± 10.2 | early-stage breast cancer | Not reported | UC、Active control | 3mo | HADS, MSAS, SF-36, SoC, PTGI | |

| Zhang 2017 [21] China | 30/30 | 48.67 ± 8.49/46.00 ± 5.12 | I-III | 2014–2015 | UC | 8week, 3mon | PSS, STAI, PTGI | |

| Witek-Janusek 2019 [22] USA | 63/61 | 55.1 ± 9.8 | early-stage breast cancer | Not reported | ACC | 12week | PSS, CES-D, MFSI, PSQI | |

| Mirmahmoodi 2020 [23] Iran | 22/22 | 44.14 ± 11.19/45.62 ± 10.11 | Not reported | Aug2017 to Nov 2019 | UC | 8week |

BAI, PSS, BDI PSQI, BFI, HADS |

|

| Qixi Liu 2022 [24] China | 28/34 | Not reported | Not reported | July 2019 to January 2021. | UC, and combined group | 8week | PSQI, BFI, HADS | |

| Shergill 2022 [25] Canada | 31/39 | 51.3 ± 11.4/55.1 ± 9.6 | Patients with CNP | Jau2014-Nov2017 | UC | 8week, 3mon | PHQ-9, FFMQ, BPI | |

| Weimin Liu 2022 [26] China | 61/63 | 24.71 ± 3.69/23.69 ± 3.16 | I-II | July28,2021,to April 21,2022 | UC | 8week, 20week | HADS, RPFS-CV, BPI, FACT-B | |

| Wang 2023 [27] China | 106/105 | 48.97 ± 8.52/49.97 ± 7.88 | Not reported | Jan 2018 to Dec 2020 | UC | 8week | SAS, SDA, FACT-B | |

| Zhu 2023 [28] China | 50/51 | 47.96 ± 8.51/49.78 ± 7.48 | breast cancer under early chemotherapy. | February 2017 to June 2018 | UC | 8week | FACT-B, SAS, SDS, PTGI | |

FACT-B The breast cancer version functional Assessment of cancer therapy, CEC Courtauld Emotional Control Scale, POMS Profile of mood states, SCL-90r The Symptom Checklist-90-r, CES-D Center for Epidemiological studies Depression Scales, STAI State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, SF-36 Short-Form General Health Survey with 36 items, PSS Perceived Stress Scale, CARS Concerns about Recurrence Scale, FSI Fatigue Symptom Inventory, PSQI Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, BCPT Breast Cancer Prevention Trail Symptom Checklist, QLACS Quality of Life in Adult Cancer Survivors, BPI Brief Pain Inventory, HADS The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, MSAS Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale, SoC Sense of Coherence, PTGI Posttraumatic Growth Inventory, MFSI Multidimensional Fatigue Scale Index, BAI Beck Anxiety Inventory, BDI Beck Depression Inventory, BFI Brief Fatigue Inventory, PHQ-9 The Neuropathic Pain Symptom Inventory, FFMQ Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire, RPFS-CV The Chinese version of the validated Piper fatigue assessment scale. SAS Self-rating Anxiety Scale, SDS Self-rating Depression Scale

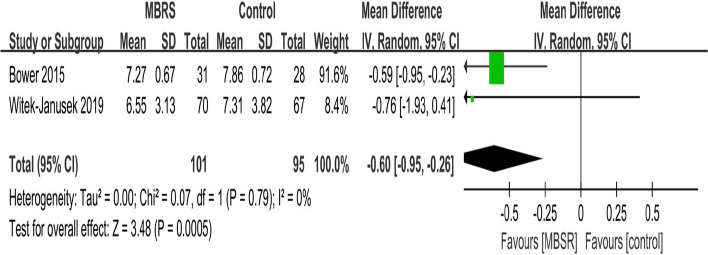

Risk of bias evaluation of the included studies

Figure 2 presents a concise overview of the findings from the comprehensive meta-analysis for each dimension. For the domain of random sequence generation (selection of bias), 66.7% (10/15) were rated as low and 33.3% (5/15) were rated as unclear; for the domain of allocation concealment (selection bias), 53.3% (8/15) were rated as low and 46.7% (7/15) were rated as unclear; most studies did not use blinding of participants 93.3% (14/15) and personnel 86.7% (13/15); however, blinding is often not possible due to the nature of the psychological intervention; for the domain of incomplete outcome data (attrition bias), 73.3% (11/15) were rated as low, 20.0% (3/15) were rated as high, and 6.6% (1/15) were rated as unclear; for the domain of selective reporting (reporting bias), 33.3% (5/15) were rated as low, 33.3% (5/15) were rated as high, and 33.3% (5/15) were rated as unclear; for the domain of other bias, 86.7% (13/15) were rated as low and 13.3% (2/15) were rated as high.

Fig. 2.

Summary of bias risk: evaluation of the authors’ assessments on the bias risk for each study included

Analysis of overall effects

Anxiety

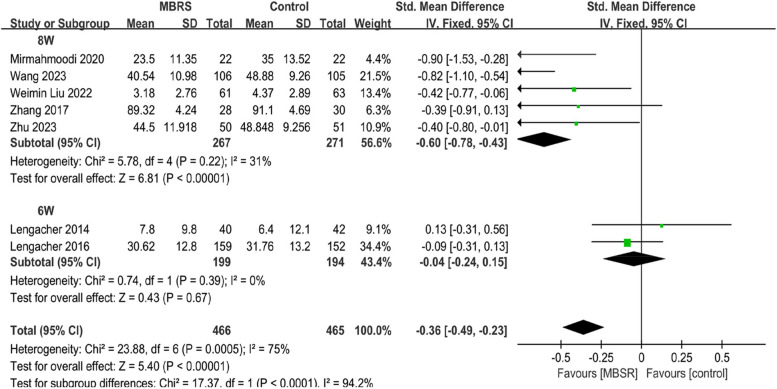

To investigate the end-of-intervention effect of MBSR on anxiety, the meta-analysis included 7 studies [17, 19, 21, 23, 26–28], including 931 patients with breast cancer. The random effects model was adopted. MBSR yielded a substantial improvement in the anxiety for breast cancer patients when compared to the control group; this effect was statistically significant [SMD=-0.40, 95% CI (-0.68,-0.12), P < 0.00001]. Importantly, subgroup analysis found that heterogeneity resulted from differences in lengths of intervention (P < 0.0001, I2 = 4.2%). In particular, the interventions with duration of eight weeks [538 participants, SMD=-0.60, 95% CI (-0.78, -0.43), P < 0.00001, I2 = 31%] significantly improved anxiety, while the intervention with a duration of six weeks was not found to have a statistically significant effect [393 participants, SMD=-0.04, 95% CI (-0.24, 0.15), I2 = 0%]. Figure 3.

Fig. 3.

The end-of -intervention effect of MBSR on anxiety

To investigate the effect of MBSR on anxiety 3 months after baseline, the meta-analysis included 6 studies [14, 16, 19–21, 26], including 974 patients with breast cancer. The random effects model was adopted. MBSR yielded a substantial improvement in the anxiety for breast cancer patients when compared to the control group; this effect was statistically significant [SMD=-0.73, 95% CI (-1.42, -0.04), P = 0.04], but after the analysis is tested for robustness, the results may be biased. Figure 4.

Fig. 4.

The effect of MBSR on anxiety 3 months after baseline

Depression

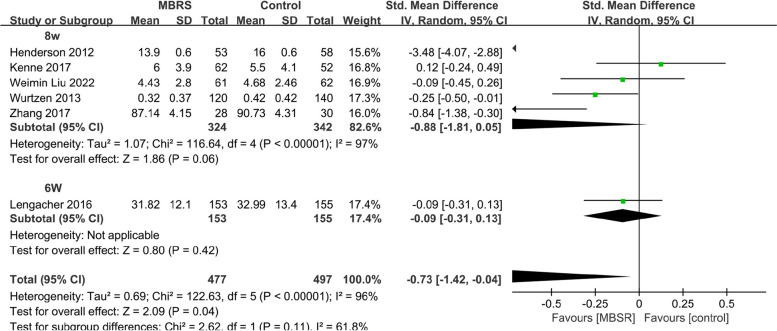

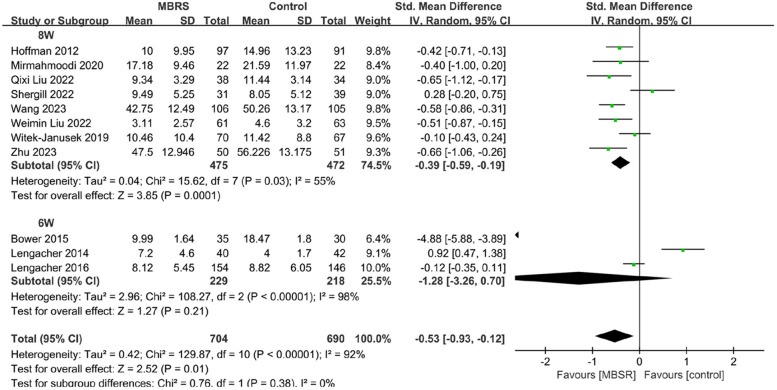

To investigate the end-of-intervention effect of MBSR on depression, The meta-analysis included 11 studies [15, 17–19, 22–28], including 1394 patients with breast cancer. The random effects model was adopted. MBSR yielded a substantial improvement in the depression for breast cancer patients when compared to the control group; this effect was statistically significant [SMD=-0.53, 95% CI (-0.93, -0.12), P = 0.01]. In particular, the interventions with duration of eight weeks [947 participants, SMD=-0.39, 95% CI (-0.59, -0.19), P = 0.0001, I2 = 55%] significantly improved depression, while the intervention with a duration of six weeks was not found to have a statistically significant effect [477 participants, SMD=-1.28, 95% CI (-3.26,0.70)]. Figure 5.

Fig. 5.

The end-of-intervention effect of MBSR on depression

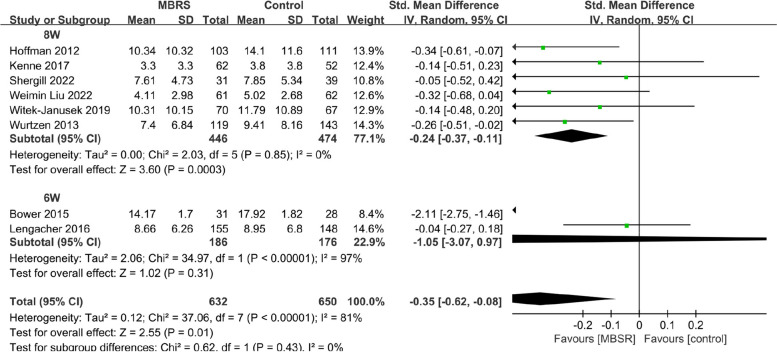

To investigate the effect of MBSR on depression 3 months after baseline, the meta-analysis included 8 studies [15, 16, 18–20, 22, 25, 26], including 1282 patients with breast cancer. The random effects model was adopted. MBSR yielded a substantial improvement in the depression for breast cancer patients when compared to the control group; this effect was statistically significant [SMD=-0.35, 95% CI (-0.62, -0.08), P = 0.01]. In particular, the interventions with duration of eight weeks [920 participants, SMD=-0.24, 95% CI ( -0.37, -0.11), P = 0.0003, I2 = 0%] significantly improved depression, while the intervention with a duration of six weeks was not found to have a statistically significant effect [362 participants, SMD=-1.05, 95% CI (-3.07, 0.97)]. Figure 6.

Fig. 6.

The effect of MBSR on depression 3 months after baseline

QOL

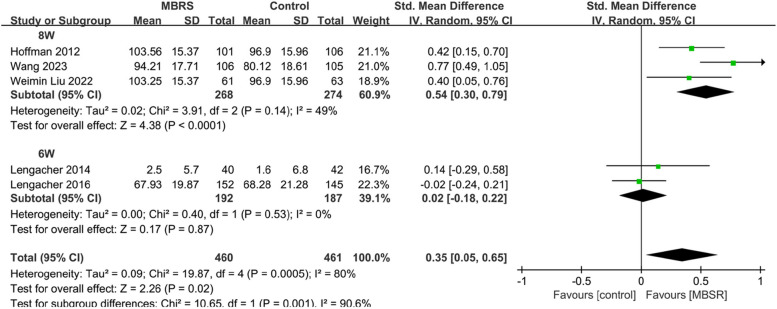

To investigate the end-of-intervention effect of MBSR on QOL, the meta-analysis included 5 studies [15, 17, 19, 26, 27], including 921 patients with breast cancer. The random effects model was adopted. MBSR yielded a substantial enhancement in the QOL for breast cancer patients when compared to the control group; this effect was statistically significant [SMD = 0.35, 95% CI (0.05, 0.65), P = 0.02], but after sensitivity analysis by one-by-one elimination method, the results may be biased. Importantly, subgroup analysis found that heterogeneity resulted from differences in lengths of intervention (P = 0.001, I2 = 90.6%). In particular, the interventions with duration of eight weeks [542 participants, SMD = 0.54, 95% CI (0.30, 0.79), P < 0.0001, I2 = 49%] significantly improved QOL, while the intervention with a duration of six weeks was not found to have a statistically significant effect [379 participants, SMD = 0.02,95%CI(-0.18,0.22),I2 = 0%]. Figure 7.

Fig. 7.

The end-of -intervention effect of MBSR on QOL

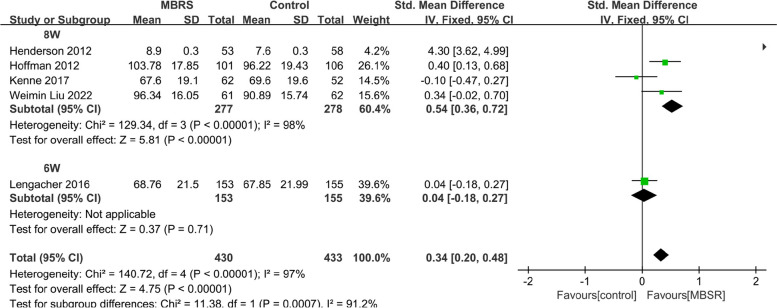

To investigate the effect of MBSR on QOL 3 months after baseline, the meta-analysis included 5 studies [14, 15, 19, 20, 26], including 863 patients with breast cancer. The random effects model was adopted. MBSR yielded a substantial enhancement in the QOL for breast cancer patients when compared to the control group; this effect was statistically significant [SMD = 0.34, 95% CI (0.20,0.48), P < 0.00001]. Additionally, the interventions with duration of eight weeks [555 participants, SMD = 0.54, 95% CI (0.36, 0.72), P < 0.00001] led to a significant improvement in QOL, whereas no statistically significant effects were found in the intervention with a duration of six weeks [308 participants, SMD = 0.04, 95% CI (-0.18, 0.27)]. Figure 8.

Fig. 8.

The effect of MBSR on QOL 3 months after baseline

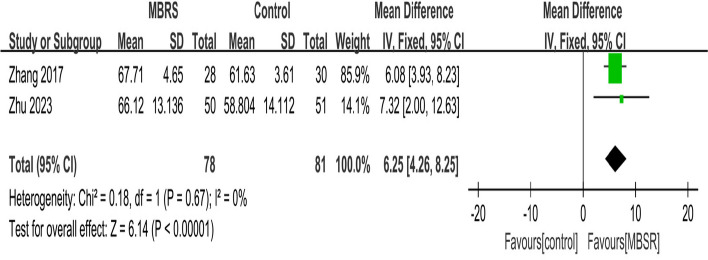

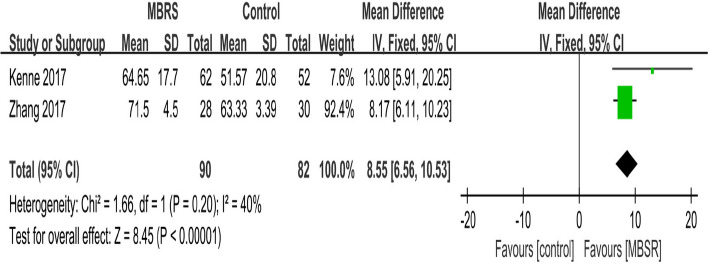

PTG

To investigate the end-of-intervention effect of MBSR on PTG, the meta-analysis included 2 studies [21, 28], including 159 patients with breast cancer. The fixed effects model was adopted. MBSR yielded a substantial enhancement in the PTG for breast cancer patients when compared to the control group; this effect was statistically PTG [MD = 6.25, 95% CI (4.26, 8.25), P < 0.00001]. Figure 9.

Fig. 9.

The end-of -intervention effect of MBSR on PTG

To investigate the effect of MBSR on PTG 3 months after baseline, the meta-analysis included 2 studies [20, 21], including 172 patients with breast cancer. The fixed effects model was adopted. MBSR yielded a substantial enhancement in PTG for breast cancer patients when compared to the control group; this effect was statistically significant [MD = 9.38, 95%CI(5.23, 13.52), P < 0.00001]. Figure 10.

Fig. 10.

10 The effect of MBSR on PTG 3 months after baseline

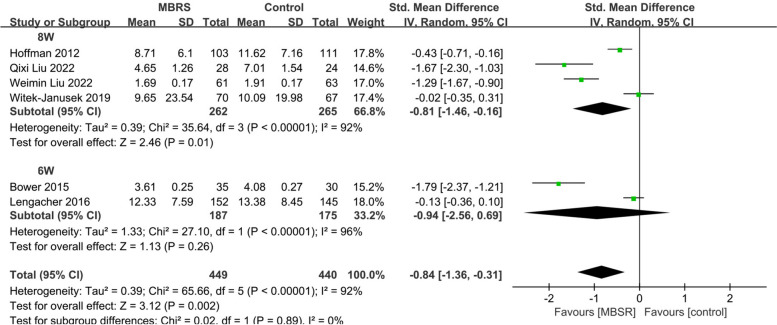

Fatigue

To investigate the end-of-intervention effect of MBSR on fatigue, the meta-analysis included 6 studies [15, 18, 19, 22, 24, 26], including 889 patients with breast cancer. The random effects model was adopted. MBSR yielded a substantial improvement in the fatigue for breast cancer patients when compared to the control group; this effect was statistically significant [SMD=-0.84, 95% CI (-1.36, -0.31), P = 0.002]. In particular, the interventions with duration of eight weeks [537 participants, SMD=-0.81, 95% CI (-1.46, -0.16), P = 0.01] significantly improved fatigue, while the intervention with a duration of six weeks was not found to have a statistically significant effect [362 participants, SMD=-0.94, 95% CI (-2.56, 0.69)]. Figure 11.

Fig. 11.

The end-of-intervention effect of MBSR on fatigue

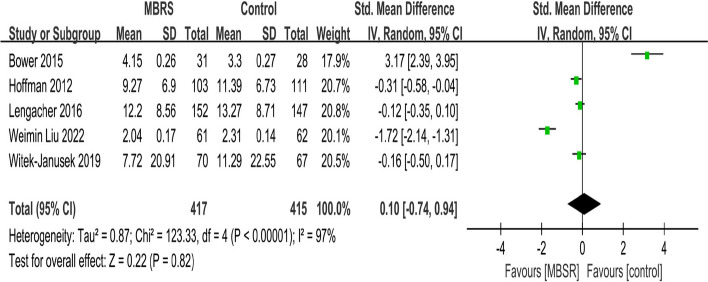

To investigate the effect of MBSR on fatigue 3 months after baseline, the meta-analysis included 5 studies [15, 18, 19, 22, 26], including 832 patients with breast cancer. The random effects model was adopted. There was no significant difference between MBSR and the control group [SMD = 0.10, 95% CI (-0.74, -0.94), P = 0.82]. Figure 12.

Fig. 12.

The effect of MBSR on fatigue 3 months after baseline

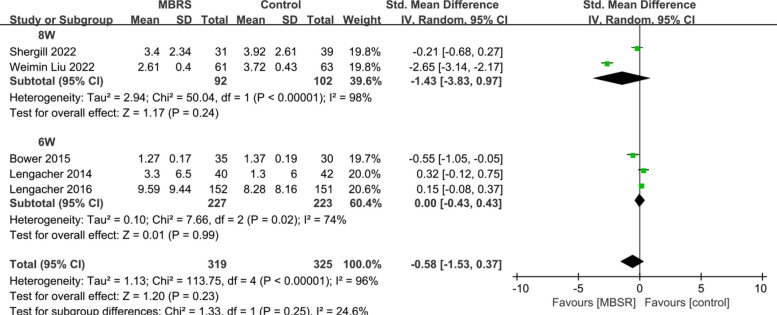

Pain

To investigate the end-of-intervention effect of MBSR on pain, the meta-analysis included 5 studies [17–19, 25, 26], including 644 patients with breast cancer. The random effects model was adopted. There was no significant difference between MBSR and the control group [SMD=-0.58, 95%CI (-1.53, 0.37), P = 0.23]. Figure 13.

Fig. 13.

The end-of -intervention effect of MBSR on pain

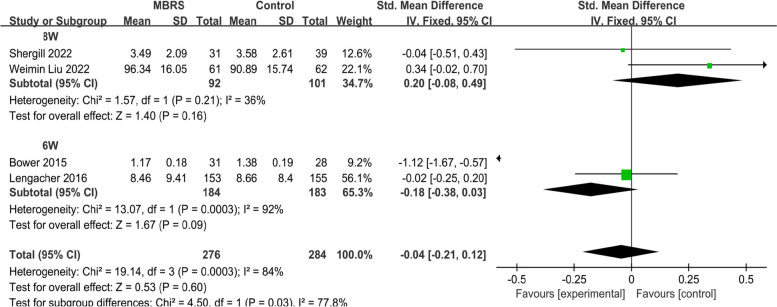

To investigate the effect of MBSR on pain 3 months after baseline, the meta-analysis included 4 studies [18, 19, 25, 26], including 560 patients with breast cancer. The random effects model was adopted. There was no significant difference between MBSR and the control group [SMD=-0.04, 95% CI (-0.21, 0.12), P = 0.6]. Figure 14.

Fig. 14.

The effect of MBSR on pain 3 months after baseline

FCR

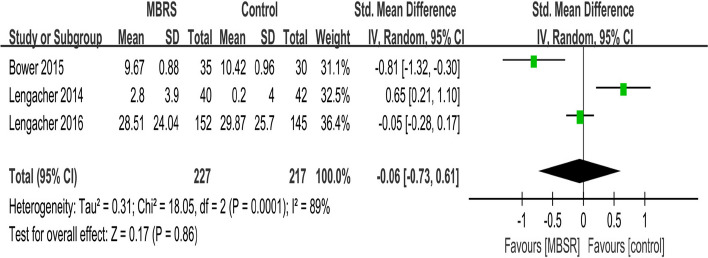

To investigate the end-of-intervention effect of MBSR on FCR, the meta-analysis included 3 studies [17–19], including 544 patients with breast cancer. The random effects model was adopted. There was no significant difference between MBSR and the control group [SMD=-0.06, 95% CI (-0.73, 0.61), P = 0.86]. Figure 15.

Fig. 15.

The end-of -intervention effect of MBSR on FCR

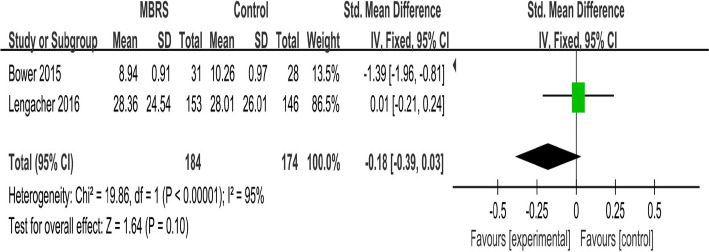

To investigate the effect of MBSR on FCR 3 months after baseline, the meta-analysis included 2 studies [18, 19], including 544 patients with breast cancer. The random effects model was adopted. There was no significant difference between MBSR and the control group [SMD=-0.18, 95%CI(-0.39, 0.03), P = 0.10], but after the analysis is tested for robustness, the results may be biased. Figure 16.

Fig. 16.

The effect of MBSR on FCR 3 months after baseline

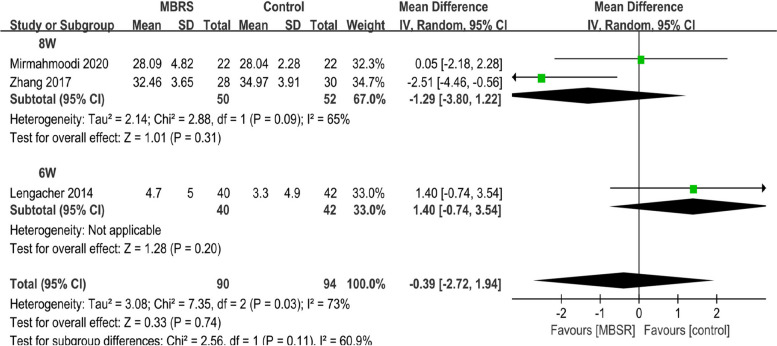

Stress

To investigate the end-of -intervention effect of MBSR on stress, the meta-analysis included 3 studies [17, 21, 23], including 184 patients with breast cancer. The random effects model was adopted. No significant difference was observed between MBSR and control groups [MD=-0.39, 95% CI (-2.72, 1.94), P < 0.74]. No studies were found that reported stress three months after baseline. Figure 17.

Fig. 17.

The end-of -intervention effect of MBSR on stress

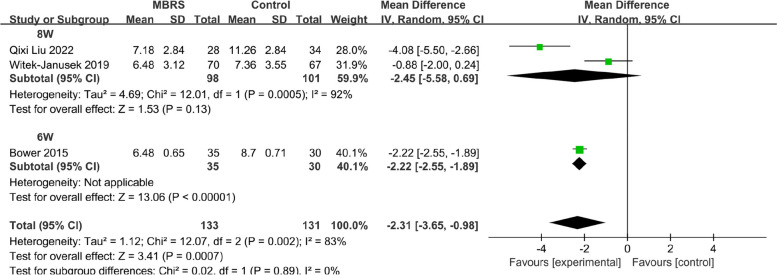

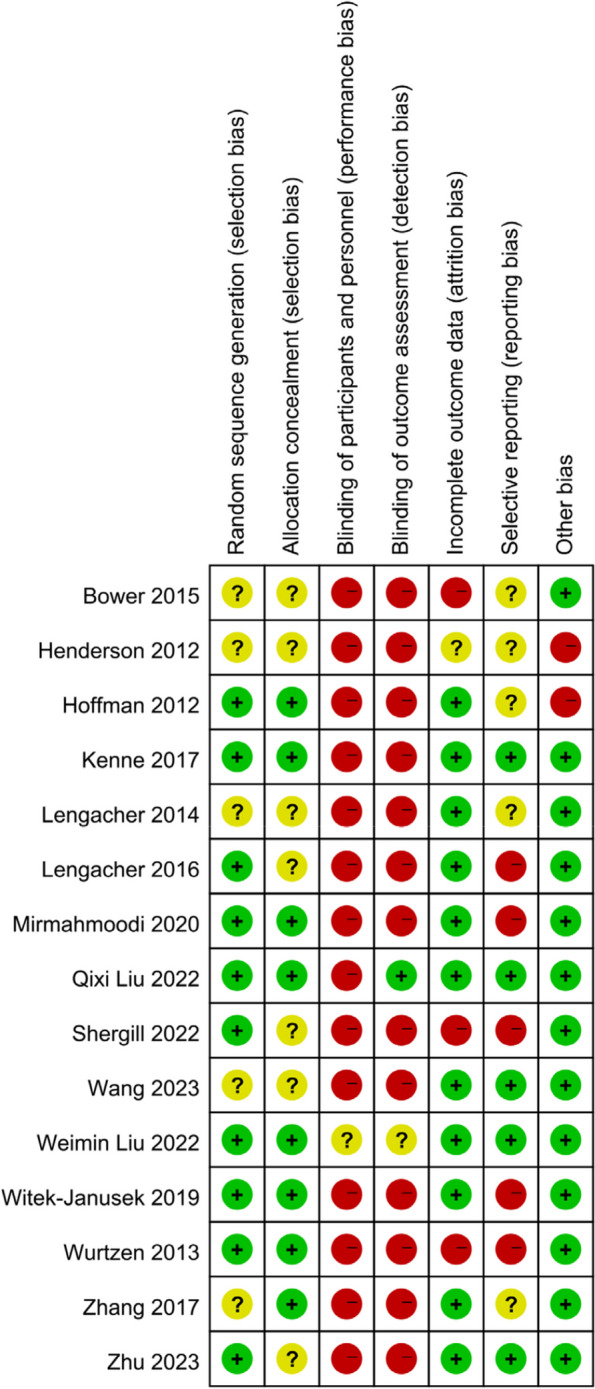

Sleep

To investigate the end-of-intervention effect of MBSR on sleep, the meta-analysis included 3 studies [18, 22, 24], including 264 patients with breast cancer. After the analysis is tested for robustness, the results may be biased. Figure 18.

Fig. 18.

The end-of -intervention effect of MBSR on sleep

To investigate the effect of MBSR on sleep 3 months after baseline, the meta-analysis included 2 studies [18, 22], including 274 patients with breast cancer. After the analysis is tested for robustness, the results may be biased. Figure 19.

Fig. 19.

The effect of MBSR on sleep 3 months after baseline

Discussion

At the end of intervention, the interventions with a duration of eight weeks led to a significant reduction in anxiety [SMD=-0.60, 95% CI (-0.78, -0.43), P < 0.00001, I2 = 31%], depression [SMD=-0.39, 95% CI (-0.59, -0.19), P = 0.0001, I2 = 55%], and QOL [542 participants SMD = 0.54, 95% CI (0.30, 0.79), P < 0.0001, I2 = 49%], whereas no statistically significant effects were found in the intervention with a duration of six weeks. Similarly, in 3 months after baseline, the interventions with a duration of eight weeks led to a significant reduction in depression and QOL, however, no statistically significant effects were found at the 6-week intervention. Similar to how MBSR works in cancer patients [29], an eight-week duration program performed better than a six-week duration program in breast cancer patients. Studies have shown that the left prefrontal cortex is more active in people who undergo MBSR training, and the thickness of the cortex such as the anterior cingulate gyrus, insula, and hippocampus increases and the density of gray matter increases, while the density of gray matter in the amygdala decreases. The response of these regions is closely related to the emotional regulation of practitioners and can improve the emotional regulation ability of practitioners [30]. MBSR focuses on the present moment, with patience, trust, non-judgment, acceptance, and an open attitude to the various symptoms. Practicing MBSR also allows patients to change their thinking patterns and reduce their negative emotions about the prognosis of the disease. In addition, In contrast to the 6-week MBSR adaptation, the 8-week MBSR also involves encouraging patients to internalize the practice process and develop a pattern of association that is appropriate to their individual circumstances, and it takes a certain period for an individual to go from exposure to internalization to having a positive impact on themselves. On the other hand, from the perspective of the mechanism of mindfulness, the training in mindfulness meditation and cognitive process emphasizes the strengthening of the momentary, non-judgmental and non-reactive awareness of internal and external experiences, thus helping to self-regulate emotions under painful situations, reduce thinking and elaboration of painful experiences, and ultimately improve patients’ negative emotions. However, this process still requires a certain period [29].

MBSR led to a significant improvement in PTG end of intervention [MD = 6.25, 95% CI (4.26, 8.25), P < 0.00001, I2 = 0%] and PTG 3 months after baseline, which was inconsistent with Wang’s research. The possible reason is that this study collected data at two-time points, namely at the end of the intervention and three months after baseline. MBSR improves PTG in breast cancer patients through multiple mechanisms of efficacy. Previous studies [31] have shown that PTG is related to patients’ negative emotions, and the alleviation of negative emotions is conducive to the development of PTG. Therefore, MBSR promotes positive change in individuals by reducing anxiety and depression in patients. Secondly, according to Lindsay’s Monitor and Acceptance Theory (MAT) [32], mindfulness can help individuals improve their level of attention monitoring and acceptance. Making them pay more attention to the present moment and deal with trauma-related psychological experiences with a more open and accepting attitude is conducive to the occurrence of PTG. In addition, the mindfulness meaning theory of Garland [33] indicates that mindfulness training can promote PTG by helping individuals recognize the positive significance of adversity to personal transformation and growth, thereby enabling them to reconstruct traumatic experiences into more positive and benign experience.

We found that MBSR reduced the fatigue status at end of the intervention, but had no significant effect on fatigue status 3 months after baseline, which was consistent with Chang’s [12] research. Importantly, this study found that at the end of the intervention, an eight-week duration program performed better than a six-week duration program at relieving fatigue. Mindfulness yoga increases the patient’s activity and improves physical fitness, thus reducing the patient’s fatigue.

However, as in Zhang’s [13] study, there was no significant difference in improving pain and stress compared to usual care. As in Wang’s [34] study, there was no significant difference in improving FCR. This study found that in terms of effects on QOL, anxiety, depression, and fatigue, the 8-week MBSR intervention showed better results than the 6-week MBSR intervention. The intervention of MBSR on PTG was effective, and the effect lasted until 3 months later. The main results of the study are highly stable after sensitivity analysis. Future studies could further identify the most effective intervention components in MBSR.

Strength and limitations

This study showed significant improvements in anxiety, depression, and QOL in breast cancer patients after MBSR, and the improvements persisted up to three months after baseline, which is encouraging. Second, this study analyzed the difference between 8-week MBSR and 6-week MBSR to explain the results of the meta-analysis. Thirdly, the endpoint of 3 months after baseline was determined after a thorough review of the literature. The endpoint of most of the original articles is 3 months after baseline, and the endpoint of all the original articles is 3 months up to 6 months after baseline. This classification standard of “up to 6 months after baseline” is often used in meta-analysis [28]. Finally, sensitivity analysis was conducted for each study in this paper through a one-by-one exclusion method, and the studies with possible bias were reported in the analysis results. It is worth noting that the main findings of this study have passed sensitivity analysis, and the research results are stable. However, because the interventions included in MBSR span a wide range, including meditation, movement exercises, psychoeducation, yoga, and home training through provided CDs or other materials, we do not yet know for sure which specific intervention is responsible. Additional original RCT studies for specific interventions are recommended. In addition, the research investigated short-term effects, but long-term effects are unknown. More relevant long-term information on MBSR should be collected in the future.

Authors’ contributions

Made substantial contributions to conception and design, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; XD, YL Involved in drafting the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content; XD, YL Given final approval of the version to be published. Each author should have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content; XD, YL, KF, Zh X, XxH, ZzhW Agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. XD, YL, KF, Zh X, XxH, ZzhW

Funding

None.

Data availability

The study was a systematic review and the data that the findings was extracted from the articles listed in Table 1.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Yan Liu, Email: cwx0609@sina.com.

Kui Fang, Email: fangkui158@126.com.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. Cancer J Clin. 2011;61(2):69–90. 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schmidt ME, Wiskemann J, Steindorf K. Quality of life, problems, and needs of disease-free breast cancer survivors 5 years after diagnosis. Qual Life Res. 2018;27(8):2077–86. 10.1007/s11136-018-1866-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang Y, Li Q, Zhou F, Song J. Effectiveness of internet-based support interventions on patients with breast cancer: a systematic review and narrative synthesis. BMJ Open. 2022;12(5):e057664. 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-057664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lebel S, Ozakinci G, Humphris G, Thewes B, Prins J, Dinkel A, Butow P. Current state and future prospects of research on fear of cancer recurrence. Psychooncology. 2017;26(4):424–7. 10.1002/pon.4103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Almeida SN, Elliott R, Silva ER, Sales CMD. Fear of cancer recurrence: a qualitative systematic review and meta-synthesis of patients’ experiences. Clin Psychol Rev. 2019;68:13–24. 10.1016/j.cpr.2018.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Infante JR, Peran F, Rayo JI, Serrano J, Domínguez ML, Garcia L, Duran C, Roldan A. Levels of immune cells in transcendental meditation practitioners. Int J yoga. 2014;7(2):147–51. 10.4103/0973-6131.133899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park CL, Cohen LH, Murch RL. Assessment and prediction of stress-related growth. J Pers. 1996;64(1):71–105. 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1996.tb00815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kabat-Zinn J, Lipworth L, Burney R. The clinical use of mindfulness meditation for the self-regulation of chronic pain. J Behav Med. 1985;8(2):163–90. 10.1007/BF00845519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guerra-Martín MD, Tejedor-Bueno MS, Correa-Casado M. Effectiveness of complementary therapies in Cancer patients: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(3):1017. 10.3390/ijerph18031017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sasaki Y, Cheon C, Motoo Y, Jang S, Park S, Ko SG, Jang BH, Hwang DS. Yakugaku Zasshi J Pharm Soc Japan. 2019;139(7):1027–46. 10.1248/yakushi.18-00215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li J, Li C, Puts M, Wu YC, Lyu MM, Yuan B, Zhang JP. Effectiveness of mindfulness-based interventions on anxiety, depression, and fatigue in people with lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2023;140:104447. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2023.104447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang YC, Yeh TL, Chang YM, Hu WY. Short-term effects of randomized mindfulness-based intervention in female breast cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Nurs. 2021;44(6):E703-14. 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang Q, Zhao H, Zheng Y. Effectiveness of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) on symptom variables and health-related quality of life in breast cancer patients-a systematic review and meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer: Official J Multinational Association Supportive Care Cancer. 2019;27(3):771–81. 10.1007/s00520-018-4570-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henderson VP, Massion AO, Clemow L, Hurley TG, Druker S, Hébert JR. A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness-based stress reduction for women with early-stage breast cancer receiving radiotherapy. Integr cancer Ther. 2013;12(5):404–13. 10.1177/1534735412473640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoffman CJ, Ersser SJ, Hopkinson JB, Nicholls PG, Harrington JE, Thomas PW. Effectiveness of mindfulness-based stress reduction in mood, breast- and endocrine-related quality of life, and well-being in stage 0 to III breast cancer: a randomized, controlled trial. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30(12):1335–42. 10.1200/JCO.2010.34.0331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Würtzen H, Dalton SO, Elsass P, Sumbundu AD, Steding-Jensen M, Karlsen RV, Andersen KK, Flyger HL, Pedersen AE, Johansen C. Mindfulness significantly reduces self-reported levels of anxiety and depression: results of a randomised controlled trial among 336 Danish women treated for stage I-III breast cancer. Eur J cancer (Oxford England: 1990). 2013;49(6):1365–73. 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lengacher CA, Shelton MM, Reich RR, Barta MK, Johnson-Mallard V, Moscoso MS, Paterson C, Ramesar S, Budhrani P, Carranza I, Lucas J, Jacobsen PB, Goodman MJ, Kip KE. Mindfulness based stress reduction (MBSR(BC)) in breast cancer: evaluating fear of recurrence (FOR) as a mediator of psychological and physical symptoms in a randomized control trial (RCT). J Behav Med. 2014;37(2):185–95. 10.1007/s10865-012-9473-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bower JE, Crosswell AD, Stanton AL, Crespi CM, Winston D, Arevalo J, Ma J, Cole SW, Ganz PA. Mindfulness meditation for younger breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. Cancer. 2015;121(8):1231–40. 10.1002/cncr.29194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lengacher CA, Reich RR, Paterson CL, Ramesar S, Park JY, Alinat C, Johnson-Mallard V, Moscoso M, Budhrani-Shani P, Miladinovic B, Jacobsen PB, Cox CE, Goodman M, Kip KE. Examination of broad symptom improvement resulting from mindfulness-based stress reduction in breast Cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncology: Official J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2016;34(24):2827–34. 10.1200/JCO.2015.65.7874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kenne Sarenmalm E, Mårtensson LB, Andersson BA, Karlsson P, Bergh I. Mindfulness and its efficacy for psychological and biological responses in women with breast cancer. Cancer Med. 2017;6(5):1108–22. 10.1002/cam4.1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang JY, Zhou YQ, Feng ZW, Fan YN, Zeng GC, Wei L. Randomized controlled trial of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) on posttraumatic growth of Chinese breast cancer survivors. Psychol Health Med. 2017;22(1):94–109. 10.1080/13548506.2016.1146405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Witek Janusek L, Tell D, Mathews HL. Mindfulness based stress reduction provides psychological benefit and restores immune function of women newly diagnosed with breast cancer: a randomized trial with active control. Brain Behav Immun. 2019;80:358–73. 10.1016/j.bbi.2019.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mirmahmoodi M, Mangalian P, Ahmadi A, Dehghan M. The effect of mindfulness-based stress reduction group counseling on psychological and inflammatory responses of the women with breast cancer. Integr cancer Ther. 2020;19:1534735420946819. 10.1177/1534735420946819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu Q, Wang C, Wang Y, Xu W, Zhan C, Wu J, Hu R. Mindfulness-based stress reduction with acupressure for sleep quality in breast cancer patients with insomnia undergoing chemotherapy: a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Oncol Nursing: Official J Eur Oncol Nurs Soc. 2022;61:102219. 10.1016/j.ejon.2022.102219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shergill Y, Rice DB, Khoo EL, Jarvis V, Zhang T, Taljaard M, Wilson KG, Romanow H, Glynn B, Small R, Rash JA, Smith A, Monteiro L, Smyth C, Poulin PA. Mindfulness-based stress reduction in breast cancer survivors with chronic neuropathic pain: a randomized controlled trial. Pain research and management. 2022;2022:4020550. 10.1155/2022/4020550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu W, Liu J, Ma L, Chen J. Effect of mindfulness yoga on anxiety and depression in early breast cancer patients received adjuvant chemotherapy: a randomized clinical trial. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2022;148(9):2549–60. 10.1007/s00432-022-04167-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang H, Yang Y, Zhang X, Shu Z, Tong F, Zhang Q, Yi J. Research on mindfulness-based stress reduction in breast Cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy: an Observational Pilot Study. Altern Ther Health Med. 2023;29(5):228–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhu P, Liu X, Shang X, Chen Y, Chen C, Wu Q. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for quality of life, psychological distress, and cognitive emotion regulation strategies in patients with breast Cancer under early Chemotherapy-a Randomized Controlled Trial. Holist Nurs Pract. 2023;37(3):131–42. 10.1097/HNP.0000000000000580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xie C, Dong B, Wang L, Jing X, Wu Y, Lin L, Tian L. Mindfulness-based stress reduction can alleviate cancer- related fatigue: a meta-analysis. J Psychosom Res. 2020;130:109916. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2019.109916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Janes AC, Datko M, Roy A, Barton B, Druker S, Neal C, Ohashi K, Benoit H, van Lutterveld R, Brewer JA. Quitting starts in the brain: a randomized controlled trial of app-based mindfulness shows decreases in neural responses to smoking cues that predict reductions in smoking. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2019;44(9):1631–8. 10.1038/s41386-019-0403-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schroevers MJ, Teo I. The report of posttraumatic growth in Malaysian cancer patients: relationships with psychological distress and coping strategies. Psycho-oncology. 2008;17(12):1239–46. 10.1002/pon.1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lindsay EK, Creswell JD. Mechanisms of mindfulness training: Monitor and Acceptance Theory (MAT). Clin Psychol Rev. 2017;51:48–59. 10.1016/j.cpr.2016.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garland EL, Farb NA, Goldin P, Fredrickson BL. Mindfulness broadens awareness and builds Eudaimonic meaning: a process model of mindful positive emotion regulation. Psychol Inq. 2015;26(4):293–314. 10.1080/1047840X.2015.1064294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang X, Dai Z, Zhu X, Li Y, Ma L, Cui X, Zhan T. Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on quality of life of breast cancer patient: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2024;19(7):e0306643. 10.1371/journal.pone.0306643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The study was a systematic review and the data that the findings was extracted from the articles listed in Table 1.