Abstract

Rationale

Cardiovascular events after chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) exacerbations are recognized. Studies to date have been post hoc analyses of trials, did not differentiate exacerbation severity, included death in the cardiovascular outcome, or had insufficient power to explore individual outcomes temporally.

Objectives

We explore temporal relationships between moderate and severe exacerbations and incident, nonfatal hospitalized cardiovascular events in a primary care–derived COPD cohort.

Methods

We included people with COPD in England from 2014 to 2020, from the Clinical Practice Research Datalink Aurum primary care database. The index date was the date of first COPD exacerbation or, for those without exacerbations, date upon eligibility. We determined composite and individual cardiovascular events (acute coronary syndrome, arrhythmia, heart failure, ischemic stroke, and pulmonary hypertension) from linked hospital data. Adjusted Cox regression models were used to estimate average and time-stratified adjusted hazard ratios (aHRs).

Measurements and Main Results

Among 213,466 patients, 146,448 (68.6%) had any exacerbation; 119,124 (55.8%) had moderate exacerbations, and 27,324 (12.8%) had severe exacerbations. A total of 40,773 cardiovascular events were recorded. There was an immediate period of cardiovascular relative rate after any exacerbation (1–14 d; aHR, 3.19 [95% confidence interval (CI), 2.71–3.76]), followed by progressively declining yet maintained effects, elevated after one year (aHR, 1.84 [95% CI, 1.78–1.91]). Hazard ratios were highest 1–14 days after severe exacerbations (aHR, 14.5 [95% CI, 12.2–17.3]) but highest 14–30 days after moderate exacerbations (aHR, 1.94 [95% CI, 1.63–2.31]). Cardiovascular outcomes with the greatest two-week effects after a severe exacerbation were arrhythmia (aHR, 12.7 [95% CI, 10.3–15.7]) and heart failure (aHR, 8.31 [95% CI, 6.79–10.2]).

Conclusions

Cardiovascular events after moderate COPD exacerbations occur slightly later than after severe exacerbations; heightened relative rates remain beyond one year irrespective of severity. The period immediately after an exacerbation presents a critical opportunity for clinical intervention and treatment optimization to prevent future cardiovascular events.

Keywords: COPD, cardiovascular disease, electronic health records, epidemiology

At a Glance Commentary

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

The relationship between chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) exacerbations and cardiovascular events is recognized. However, many studies have been post hoc analyses of clinical trials and self-controlled studies, including patients with more severe disease, showing an increased relative magnitude of effect of cardiovascular events in the short term after a COPD exacerbation but with mixed results on the importance of exacerbation severity and relative effects of cardiovascular events. To date, the temporal relationship between COPD exacerbations and cardiovascular disease has not been described with a focus on routine care settings to reflect various COPD phenotypes.

What This Study Adds to the Field

We used a generalizable, primary care–defined COPD cohort to determine relative and absolute rates for a wide range of nonfatal cardiovascular events after moderate and severe COPD exacerbations, split into short time periods, over one-year follow-up. The period immediately after hospitalization for an exacerbation presents an acute, critical opportunity for clinical intervention and treatment optimization to prevent future cardiovascular events. Heightened relative effects remain one year later irrespective of exacerbation severity. This study illustrates that postexacerbation intervention approaches should include the management of cardiopulmonary risk to reduce the risk of COPD and cardiovascular events in the short and long terms.

The pathophysiological links between chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and cardiovascular disease (CVD) are recognized and believed to be related to underlying systemic inflammation (1), hyperinflation, or arterial stiffness and common risk factors (2, 3). COPD is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events independently of age, sex, smoking history, and other confounders (4, 5). In addition to the association in stable COPD (5), studies have shown that the time of an exacerbation of COPD offers a period of heightened cardiovascular risk (6).

Previous studies examining the relationship between COPD exacerbations and CVD focused on COPD exacerbation frequency (7–10), subgroup analyses by effect modifiers such as baseline CVD status (8, 9, 11–13), and within-patient self-controlled designs exploring relative effects comparing stable with postexacerbation periods (8, 9, 11, 13–16). Few studies have defined a range of individual outcomes (13, 15); those that have focused solely on stroke and myocardial infarction (MI) (6, 8, 14, 15, 17), atrial fibrillation (AF) (16), and/or composite outcomes (9, 12, 18). Few have investigated exacerbation severity, through either primary care–managed versus hospitalized events (8, 9, 12) or medication status (11, 14, 18). Although studies have established effects across multiple periods in the first year (8, 9, 12, 14, 16, 18), to our knowledge, this is the first study to use a generalizable primary care–defined COPD cohort to determine absolute risk (percentage) and rates of specific nonfatal cardiovascular events after both moderate and severe COPD exacerbations across multiple intervals, over long-term follow-up.

EXACOS-CV (Exacerbations of COPD and Their Outcomes on Cardiovascular Diseases) is a multicountry program that seeks to further characterize the association of COPD exacerbation and CVD through retrospective longitudinal cohort studies across various databases and country contexts (19). Here, we explore the temporal relationship between moderate (primary care–managed) and severe (hospitalized) exacerbations with nonfatal cardiovascular events among people with COPD in England using the United Kingdom’s Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) Aurum database. Our aim was to determine the absolute and relative rates of cardiovascular events (individual and composite) at multiple intervals across long-term follow-up after COPD exacerbation.

Methods

Data Source

We used routinely collected electronic health record (EHR) data from the CPRD Aurum database. CPRD is a pseudonymized primary care database covering 20% general practitioner (GP)–registered patients in England (20). CPRD Aurum is broadly representative in terms of age and sex (21). Linked data from the Office for National Statistics for mortality, socioeconomic data from the Index of Multiple Deprivation, and secondary care data from Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) were obtained from CPRD.

Study Population and Study Design

We conducted an open cohort study including people with both new diagnoses of and long-standing diagnoses of COPD. People were eligible to be included in the cohort if they 1) were aged 40 years or older; 2) had a COPD diagnosis, the definition of which is based on a validated algorithm (86.5% predictive positive value) (22); 3) were eligible for linkage with HES and Office for National Statistics data; 4) had smoking histories (i.e., current or ex-smokers); 5) had continuous GP practice registration with data of acceptable quality in the year before the start of follow-up; and 6) had data recorded after January 1, 2014. The index date in the exacerbation group (exposed) was the date of the first exacerbation after meeting eligibility criteria. For the nonexacerbating group (unexposed), the index date was the latest of COPD diagnosis date, 40th birthday, at least one year of continuous data of acceptable quality, and January 1, 2014. Follow-up was from the index date until December 31, 2019, or earlier if patients died or transferred GP practice (Figure 1). Minimum follow-up was one day.

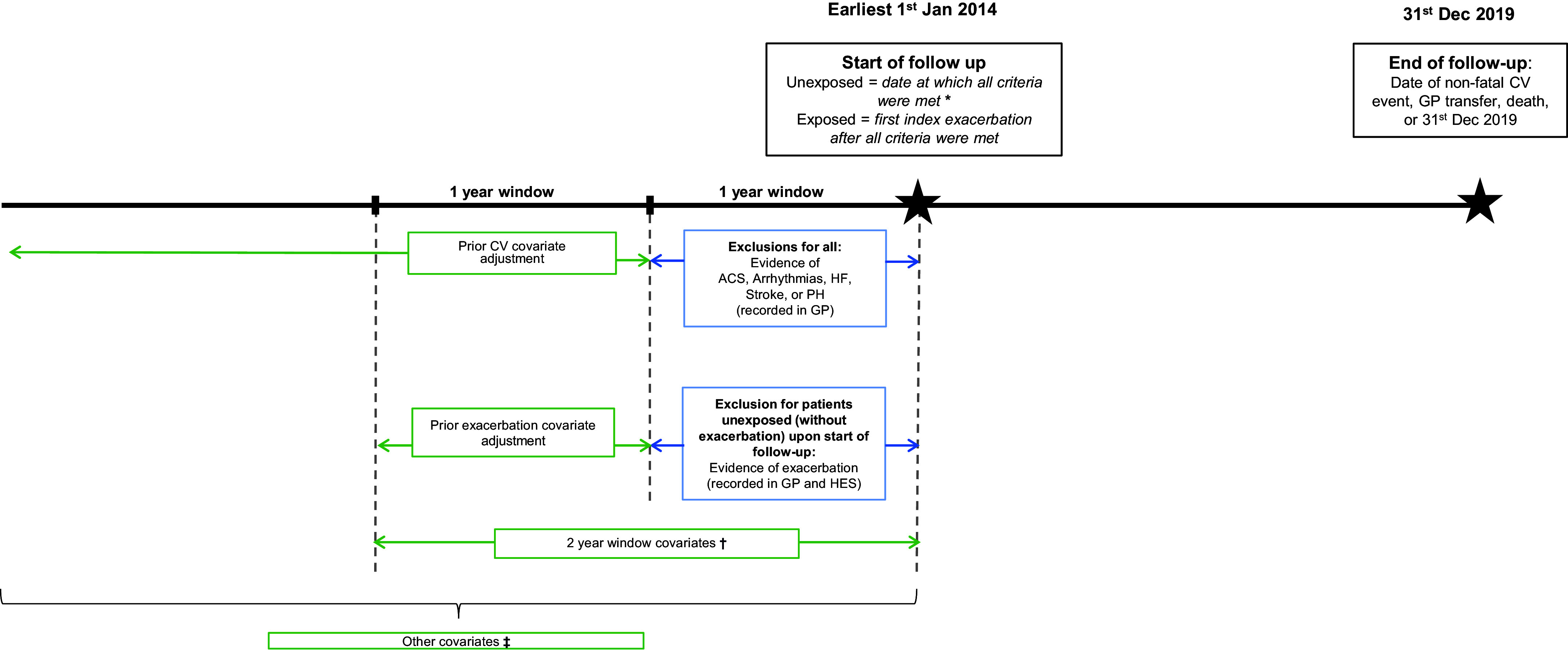

Figure 1.

Study timeline with exclusion criteria and periods of covariate measurement. *Upon index date: “acceptable” data quality; age 40 years; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) diagnosis; former or current smoker; HES, Office for National Statistics, and Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) linkage eligibility; and continuous 1-year GP registration. †Two-year window covariates: Medical Research Council dyspnea score, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease grade, COPD and CV medications, venous thromboembolism, and chronic kidney disease. ‡Other covariates defined as all time unless specified: age, sex, IMD, ethnicity, recent smoking history, body mass index (previous 5 yr), type 2 diabetes, current asthma (period of 3 years before a 2-year period before COPD diagnosis), depression or depressive symptoms, anxiety, and hypertension. ACS = acute coronary syndrome; CV = cardiovascular; GP = general practitioner; HES = Hospital Episode Statistics; HF = heart failure; PH = pulmonary hypertension.

Exclusion criteria

For primary outcome analyses, patients were excluded if in the year before index they had evidence of any type of cardiovascular event (composite outcome) and, in the unexposed group, also had exacerbations (Figures 1 and E1 in the online supplement for an inclusion diagram and see Table E8.1 for exclusion details). For secondary outcome analyses, patients were excluded if they had evidence of that specific outcome of interest only in the year before index.

Exposure

The exposure was any exacerbation (moderate or severe), whichever came first after meeting eligibility criteria. We repeated analyses distinguishing first moderate or first severe exacerbation in the study period. A moderate exacerbation was defined as a COPD-related primary care (GP) visit with either a code for exacerbation (including lower respiratory tract infection SNOMED CT codes; SNOMED International) and/or prescription for respiratory antibiotics and oral systemic corticosteroids not on the same day as an annual review. This definition has been validated in the CPRD (23). A severe exacerbation was defined as a hospitalization with an acute respiratory event code including COPD or bronchitis as a primary diagnosis or a secondary diagnosis of COPD, as previously validated in HES (24). We considered exacerbations to be the same event if recorded within 14 days, in which case the highest degree of severity was chosen.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the first of any nonfatal cardiovascular event as determined in HES data using International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, codes in the primary diagnostic position across all episodes in a single hospitalization. The composite outcome comprised acute coronary syndrome (ACS; including MI and unstable angina), arrhythmias, heart failure (HF), ischemic stroke, and pulmonary hypertension (PH). Secondary outcomes were by each individual cardiovascular component of the original composite outcome (see Table E8.2 for extended outcome definitions). The date of admission was the date of outcome.

Covariates

We had a “core” set of covariates for which we adjusted models, including age, sex, Index of Multiple Deprivation, smoking history, body mass index, type 2 diabetes, current asthma, depression, anxiety, hypertension, venous thromboembolism, COPD medication, and CVD medication. In sensitivity analyses only, in addition to the core set of covariates, we adjusted for a “sensitivity” set of covariates, including Medical Research Council (MRC) dyspnea score, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) grade, and chronic kidney disease, because of missing data (see Table E8.3 for extended covariate definitions). We chose covariates for models on the basis of 1) clinical expertise, 2) previous literature demonstrating relationships between selected covariates and cardiovascular events, and 3) previous research we have done on the COPD–CVD relationship using similar covariates (as appropriate).

Code Lists

Code lists for primary care covariates were generated using SNOMED CT and British National Formulary ontologies; we used our standardizable, reproducible methodology, available at GitHub for drug code lists (25) and for medical and/or phenotype code lists. Code lists for hospital events used International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, codes. All code lists are available in our GitHub repository.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were performed in Stata version 17 (StataCorp LLC). Baseline characteristics were described overall and by exacerbation status. Absolute risk (percentage) and crude incidence rates were calculated across follow-up for patients with exacerbations (of any severity and by severity) and for patients without exacerbations.

Prespecification of subperiod hazards

We anticipated the effect of exacerbation on cardiovascular events would not be constant over time (i.e., violating the Cox proportional-hazards assumption). We visualized the instantaneous hazard of the event over time and assessed event rates across time to prespecify the following six subperiods, focusing within the first year: 1–14 days, 14–30 days, 30 days to 3 months, 3–9 months, 9 months to 1 year, and 1 year to the end of follow-up (see Appendix E8 for extended methodology).

Survival analyses

Cox regression was used to investigate time from the index date to the first composite nonfatal cardiovascular event, comparing patients with and those without exacerbations, adjusted for all “core set” covariates. Before running final multivariable models, we examined covariates for potential collinearity, and no collinearity was found (see Table E8.4). Models were fitted with and without stratification of time (according to the six prespecified subperiods). We applied Bonferroni corrections to the significance level for time-stratified models (see Table E8.5 and see Appendix E8 for extended methodology).

Sensitivity Analyses

We undertook extensive sensitivity analyses. Specifically, we 1) reran our core analysis to include covariates for which we had extensive missing data (GOLD stage, ethnicity, chronic kidney disease, and MRC dyspnea scores); 2) ran our model including patients with evidence of cardiovascular events in the year before the index date; 3) included patients with only a single exacerbation in the follow-up period before the outcome to investigate patients whose outcomes were not related to subsequent exacerbations; 4) removed PH as an outcome in the composite event; 5) included all-cause death within the composite event; 6) included all-cause mortality as a competing risk with the composite event; and 7) included patients whose cardiovascular outcomes occurred on the same day as their exacerbations.

Exploratory Analyses

We calculated the proportion of patients who had their cardiovascular outcomes within the same hospitalization as their exacerbations.

Results

A total of 213,466 people with diagnoses of COPD were included (see Figure E1). At the start of follow-up, 67,018 (31.4%) had no exacerbations, and 146,448 (68.6%) had any type of exacerbation, of whom 119,124 first had moderate (GP-managed) exacerbations and 27,324 first had severe (hospitalized) exacerbations (81.3% and 18.7% of any exacerbation, respectively). Baseline characteristics are detailed in Table 1 and medications at index in Table 2.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Patients by Exacerbation Status at Index

| Exacerbation by Severity |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariate at Index | Total (n = 213,466) | No Exacerbation (n = 67,018 [31.4%]) | Any Exacerbation (Moderate or Severe) (n = 146,448 [68.6%]) | Moderate (n = 119,124 [55.8%]; 81.3% of Any Exacerbations) | Severe (n = 27,324 [12.8%]; 18.7% of Any Exacerbations) |

| Study follow-up, yr, median (IQR) | 2.4 (0.9–4.5) | 2.6 (1.0–5.4) | 2.3 (0.9–4.2) | 2.6 (1.1–4.4) | 1.2 (0.3–2.9) |

| All range (0–6 yr) | |||||

| Age at entry, yr, mean (SD) | 68.8 (11.2) | 66.6 (11.2) | 69.8 (11.0) | 69.3 (11.0) | 72.3 (10.9) |

| Female sex | 102,025 (47.8) | 27,833 (41.5) | 74,192 (50.7) | 60,878 (51.1) | 13,314 (48.7) |

| Smoking status | |||||

| Ex-smoker | 118,152 (55.3) | 34,865 (52.0) | 83,287 (56.9) | 68,095 (57.2) | 15,192 (55.6) |

| Current smoker | 95,314 (44.7) | 32,153 (48.0) | 63,161 (43.1) | 51,029 (42.8) | 12,132 (44.4) |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| White | 161,351 (75.6) | 48,622 (72.6) | 112,729 (77.0) | 92,072 (77.3) | 20,657 (75.6) |

| South Asian | 3,200 (1.5) | 1,031 (1.5) | 2,169 (1.5) | 1,816 (1.53) | 353 (1.3) |

| Black | 1,787 (0.8) | 730 (1.1) | 1,057 (0.7) | 864 (0.7) | 193 (0.7) |

| Mixed | 668 (0.31) | 271 (0.4) | 397 (0.3) | 314 (0.3) | 83 (0.3) |

| Other | 624 (0.29) | 262 (0.4) | 362 (0.3) | 306 (0.3) | 56 (0.2) |

| Missing/unstated | 45,836 (21.5) | 16,102 (24.0) | 29,734 (20.3) | 23,752 (19.9) | 5,982 (21.9) |

| Index of Multiple Deprivation quintile | |||||

| Least deprived | 29,468 (13.8) | 10,116 (15.1) | 19,352 (13.2) | 15,977 (13.4) | 3,375 (12.4) |

| 2 | 36,927 (17.3) | 12,032 (18.0) | 24,895 (17.0) | 20,445 (17.2) | 4,450 (16.3) |

| 3 | 39,206 (18.4) | 12,813 (19.1) | 26,393 (18.0) | 21,448 (18.0) | 4,945 (18.1) |

| 4 | 47,171 (22.1) | 14,832 (22.1) | 32,339 (22.1) | 26,050 (21.9) | 6,289 (23.0) |

| Most deprived | 60,551 (28.4) | 17,185 (25.6) | 43,366 (29.6) | 35,120 (29.5) | 8,246 (30.2) |

| Missing | 143 (0.1) | <50 (suppressed) | 103 (0.1) | 84 (0.1) | <50 (suppressed) |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| BMI | |||||

| Underweight (<18.5 kg/m2) | 9,753 (4.6) | 2,345 (3.5) | 7,408 (5.1) | 4,900 (4.1) | 2,508 (9.2) |

| Normal (18.5 to <25 kg/m2) | 64,600 (30.3) | 19,510 (29.1) | 45,090 (30.8) | 35,741 (30.0) | 9,349 (34.2) |

| Overweight (25 to <30 kg/m2) | 65,070 (30.5) | 20,474 (30.6) | 44,596 (30.5) | 37,548 (31.5) | 7,048 (25.8) |

| Obese (⩾30 kg/m2) | 58,909 (27.6) | 17,393 (26.0) | 41,516 (28.4) | 35,089 (29.5) | 6,427 (23.5) |

| Missing/unknown | 15,134 (7.1) | 7,296 (10.9) | 7,838 (5.4) | 5,846 (4.9) | 1,992 (7.3) |

| Chronic kidney disease | |||||

| No (eGFR > 60% or uAlb < 3 mg/mmol) | 141,714 (66.4) | 43,756 (65.3) | 97,958 (66.9) | 80,340 (67.4) | 17,618 (64.5) |

| Yes | 27,874 (13.1) | 7,043 (10.5) | 20,831 (14.2) | 15,930 (13.4) | 4,901 (17.9) |

| Missing | 43,878 (20.6) | 16,219 (24.2) | 27,659 (18.9) | 22,854 (19.2) | 4,805 (17.6) |

| Type 2 diabetes | 38,453 (18.0) | 10,242 (15.3) | 28,211 (19.3) | 22,496 (18.9) | 5,715 (20.9) |

| Depression/depressive symptoms | 141,232 (66.2) | 38,639 (57.7) | 102,593 (70.1) | 83,509 (70.1) | 19,084 (69.8) |

| Anxiety | 54,804 (25.7) | 14,761 (22.0) | 40,043 (27.3) | 32,912 (27.6) | 7,131 (26.1) |

| Current asthma | 27,476 (12.9) | 6,533 (9.8) | 20,943 (14.3) | 17,810 (15.0) | 3,133 (11.5) |

| Hypertension | 102,659 (48.1) | 29,541 (44.1) | 73,118 (49.9) | 58,889 (49.4) | 14,229 (52.1) |

| Venous thromboembolism | 2,889 (1.4) | 713 (1.1) | 2,176 (1.5) | 1,482 (1.2) | 694 (2.5) |

| Prior prevalent CVD | 39,014 (18.3) | 10,079 (15.0) | 28,935 (19.8) | 23,442 (19.7) | 5,493 (20.1) |

| Acute coronary syndrome | 15,089 (7.1) | 4,016 (6.0) | 11,073 (7.6) | 8,767 (7.4) | 2,306 (8.4) |

| Arrhythmias | 18,036 (8.5) | 4,753 (7.1) | 13,283 (9.1) | 11,481 (9.6) | 1,802 (6.6) |

| Heart failure | 3,672 (1.7) | 898 (1.3) | 2,774 (1.9) | 2,375 (2.0) | 399 (1.5) |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 942 (0.4) | 165 (0.3) | 777 (0.5) | 594 (0.5) | 183 (1.7) |

| Ischemic stroke | 9,795 (4.6) | 2,303 (3.4) | 7,492 (5.1) | 5,673 (4.8) | 1,819 (6.7) |

| COPD prognosis | |||||

| Exacerbation frequency in the 1-yr window preceding 1 yr to index | |||||

| 0 | 160,411 (75.2) | 57,544 (85.9) | 102,867 (70.2) | 82,809 (69.5) | 20,058 (73.4) |

| 1 | 32,436 (15.2) | 7,564 (11.3) | 24,872 (17.0) | 20,706 (17.4) | 4,166 (15.3) |

| 2 | 11,725 (5.5) | 1,503 (2.2) | 10,222 (7.0) | 8,577 (7.2) | 1,645 (6.0) |

| ⩾3 | 8,894 (4.2) | 407 (0.6) | 8,487 (5.8) | 7,032 (5.9) | 1,455 (5.3) |

| GOLD grade of airflow limitation | |||||

| 1 (mild) | 52,389 (24.5) | 19,747 (29.5) | 32,642 (22.3) | 28,839 (24.2) | 3,803 (13.9) |

| 2 (moderate) | 88,112 (41.3) | 28,645 (42.7) | 59,467 (40.6) | 50,677 (42.5) | 8,790 (32.2) |

| 3 (severe) | 32,590 (15.3) | 7,026 (10.5) | 25,564 (17.5) | 19,533 (16.4) | 6,031 (22.1) |

| 4 (very severe) | 6,664 (3.1) | 1,040 (1.6) | 5,624 (3.8) | 3,438 (2.9) | 2,186 (8.0) |

| Missing/unknown | 33,711 (15.8) | 10,560 (15.8) | 23,151 (15.8) | 16,637 (14.0) | 6,514 (23.8) |

| MRC dyspnea score | |||||

| 1 | 34,068 (16.0) | 14,254 (21.3) | 19,814 (13.5) | 17,779 (14.9) | 2,035 (7.5) |

| 2 | 72,120 (33.8) | 22,703 (33.9) | 49,417 (33.7) | 42,711 (35.9) | 6,706 (24.5) |

| 3 | 47,124 (22.1) | 10,346 (15.4) | 36,778 (25.1) | 29,846 (25.1) | 6,932 (25.4) |

| 4 | 22,664 (10.6) | 3,594 (5.4) | 19,070 (13.0) | 13,600 (11.4) | 5,470 (20.0) |

| 5 | 4,903 (2.3) | 603 (0.9) | 4,300 (2.9) | 2,651 (2.2) | 1,649 (6.0) |

| Missing/unknown | 32,587 (15.3) | 15,518 (23.2) | 17,069 (11.7) | 12,537 (10.5) | 4,532 (16.6) |

Definition of abbreviations: BMI = body mass index; CVD = cardiovascular disease; eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate; GOLD = Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; IQR = interquartile range; MRC = Medical Research Council; uAlb = microalbuminuria.

Data are expressed as n (%) except as indicated.

Table 2.

Baseline Medications by Exacerbation Status

| Exacerbation by Severity |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prescription in the 24 mo Preceding Index Date | Total (n = 213,466) | No Exacerbation (n = 67,018 [31.4%]) | Any Exacerbation (Moderate or Severe) (n = 146,448 [68.6%]) | Moderate (n = 119,124 [55.8%]; 81.3% of Any Exacerbations) | Severe (n = 27,324 [12.8%]; 18.7% of Any Exacerbations) |

| Any cardiovascular medication | 148,117 (69.4) | 42,660 (63.7) | 105,457 (72.0) | 84,882 (71.3) | 20,575 (75.3) |

| Positive inotropes (digoxin) | 3,090 (1.5) | 756 (1.1) | 2,334 (1.6) | 2,124 (1.8) | 210 (0.8) |

| Diuretics | 57,329 (26.9) | 14,473 (21.6) | 42,856 (29.3) | 33,661 (28.3) | 9,195 (33.7) |

| Antiarrhythmic drugs | 1,783 (0.8) | 435 (0.7) | 1,348 (0.9) | 1,057 (0.9) | 291 (1.1) |

| β-blockers | 35,117 (16.5) | 11,192 (16.7) | 23,925 (16.3) | 19,755 (16.6) | 4,170 (15.3) |

| Hypertension and heart failure drugs | 85,314 (40.0) | 25,059 (37.4) | 60,255 (41.1) | 49,197 (41.3) | 11,058 (40.5) |

| Nitrates, CCBs, other antianginals | 73,138 (34.3) | 20,633 (30.8) | 52,505 (35.9) | 42,192 (35.4) | 10,313 (37.7) |

| Anticoagulants | 12,050 (5.6) | 3,198 (4.8) | 8,852 (6.0) | 7,519 (6.3) | 1,333 (4.9) |

| Antiplatelets | 59,325 (27.8) | 15,936 (23.8) | 43,389 (29.6) | 34,232 (28.7) | 9,157 (33.5) |

| Statins | 98,264 (46.0) | 28,219 (42.1) | 70,045 (47.8) | 56,967 (47.8) | 13,078 (47.9) |

| Any COPD medication | 166,936 (78.2) | 41,505 (61.9) | 125,431 (85.7) | 101,829 (85.5) | 23,602 (86.4) |

| Oral therapies | |||||

| PDET4 inhibitors | 40 (0.0) | <40 (suppressed) | <40 (suppressed) | <40 (suppressed) | <40 (suppressed) |

| Theophyllines | 7,343 (3.4) | 758 (1.1) | 6,585 (4.5) | 4,584 (3.9) | 2,001 (7.3) |

| Long-acting, inhaled therapies | |||||

| No long-acting therapies | 48,920 (22.9) | 26,565 (39.6) | 22,355 (15.3) | 18,421 (15.5) | 3,934 (14.4) |

| ICS monotherapy | 12,493 (5.9) | 5,093 (7.6) | 7,400 (5.1) | 6,463 (5.4) | 937 (3.4) |

| LABA monotherapy | 3,923 (1.8) | 1,388 (2.1) | 2,535 (1.7) | 2,211 (1.9) | 324 (1.2) |

| LAMA monotherapy | 25,657 (12.0) | 9,146 (13.7) | 16,511 (11.3) | 13,802 (11.6) | 2,709 (9.9) |

| LABA/LAMA dual therapy | 8,873 (4.2) | 2,149 (3.2) | 6,724 (4.6) | 5,417 (4.6) | 1,307 (4.8) |

| LAMA/ICS or LABA/ICS dual therapy | 45,498 (21.3) | 12,924 (19.3) | 32,574 (22.2) | 27,646 (23.2) | 4,928 (18.0) |

| ICS/LABA + LABA triple therapy | 68,102 (31.9) | 9,753 (14.6) | 58,349 (39.8) | 45,164 (37.9) | 13,185 (48.3) |

| Short-acting, inhaled therapies | |||||

| No short-acting therapies | 186,410 (87.3) | 60,139 (89.7) | 126,271 (86.2) | 102,444 (86.0) | 23,827 (87.2) |

| SABA | 15,217 (7.1) | 3,823 (5.7) | 11,394 (7.8) | 9,590 (8.1) | 1,804 (6.6) |

| SAMA | 2,564 (1.2) | 950 (1.4) | 1,614 (1.1) | 1,346 (1.1) | 268 (1.0) |

| SABA/SAMA | 9,275 (4.3) | 2,106 (3.1) | 7,169 (4.9) | 5,744 (4.8) | 1,425 (5.2) |

Definition of abbreviations: CCB = calcium channel blocker; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ICS = inhaled corticosteroid; LABA = long-acting β-agonist; LAMA = long-acting muscarinic antagonist; PDET4 = phosphodiesterase type 4; SABA = short-acting β-agonist; SAMA = short-acting muscarinic antagonist.

Data are expressed as n (%); n (%) described for the COPD and cardiovascular prescription categories may be mutually exclusive, as they can be taken in combination elsewhere in the table (e.g., a patient prescribed a long-acting inhaler, a short-acting inhaler, oral therapy, and a cardiovascular medication).

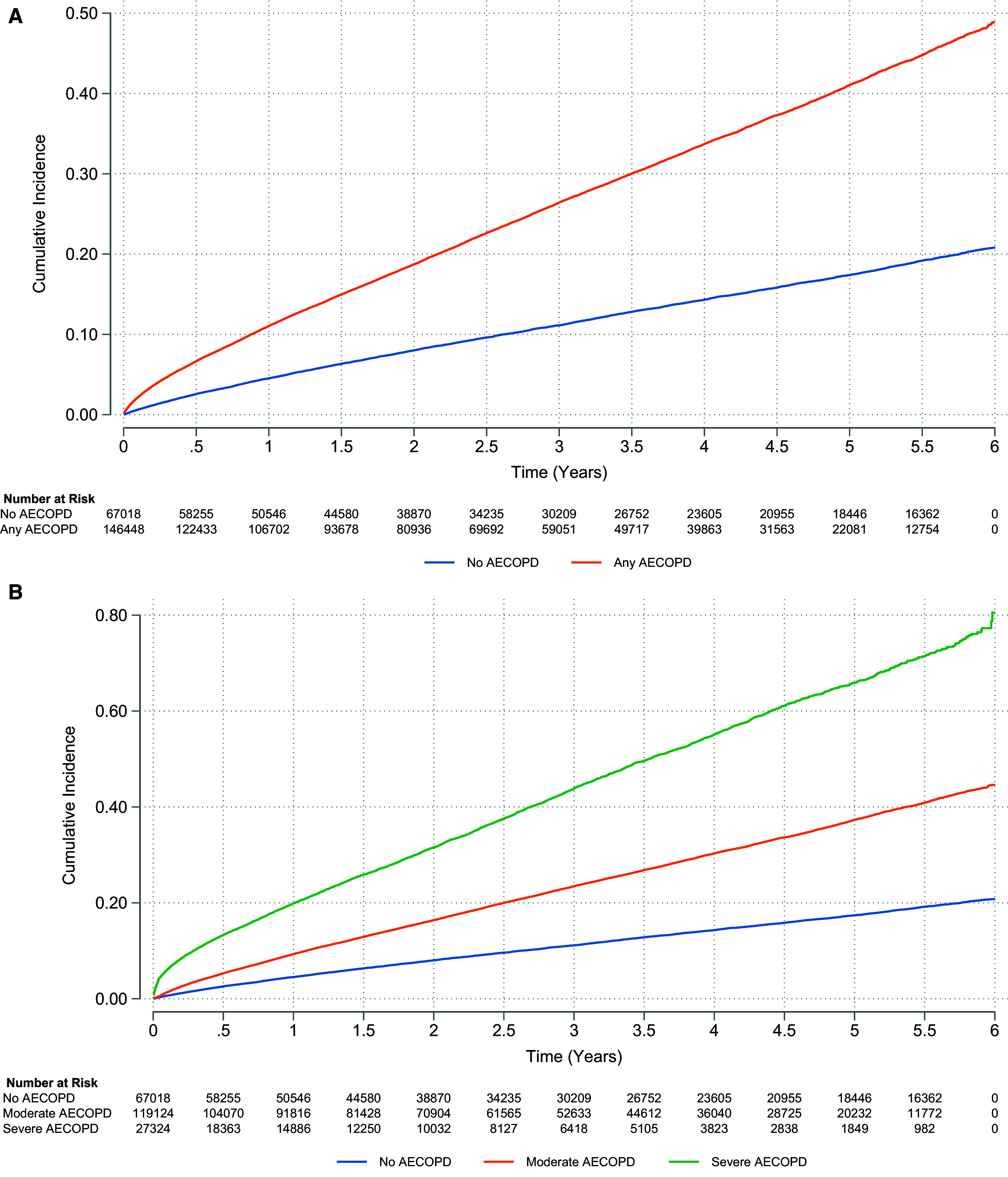

Exacerbation and Future Cardiovascular Events

A total of 40,773 cardiovascular events were recorded over a median of 2.40 years of follow-up (interquartile range, 0.94–4.45 yr) (Table 1), of which 4,108 (10.1%) were ACS, 20,080 (49.3%) arrhythmia, 12,694 (31.1%) HF, 1,492 (3.66%) PH, and 2,399 (5.88%) ischemic stroke. The cumulative incidence of composite cardiovascular event after any exacerbation is shown in Figure 2A and by exacerbation severity in Figure 2B (see Figures E2A and E2B for the first 100 d). Follow-up was similar among those with and without exacerbations; upon stratification, those with severe exacerbations had a median of 1.21 years of follow-up (interquartile range, 0.26–2.89 yr).

Figure 2.

(A and B) Cumulative incidence for composite cardiovascular events for the chronic obstructive pulmonary disease population for exacerbation dichotomized (A) and stratified by severity (B). (A) Moderate or severe exacerbation: unadjusted hazard ratio (HR), 2.36 (95% confidence interval [CI], 2.30–2.42); adjusted HR, 1.84 (95% CI, 1.79–1.90). (B) Moderate exacerbation: unadjusted HR, 2.11 (95% CI, 2.06–2.17); adjusted HR, 1.67 (95% CI, 1.62–1.72). Severe exacerbation: unadjusted HR, 4.07 (95% CI, 3.94–4.21); adjusted HR, 3.18 (95% CI, 3.06–3.29). See Figures E2A and E2B for any exacerbation and exacerbation by severity, respectively, for identical but subset plots focusing on the first 100 days of follow-up to illustrate cumulative incidence in the immediate exacerbation aftermath. AECOPD = acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Approximately 28 people experienced at least one cardiovascular event out of every 100 hospitalized exacerbations (7,564 of 27,324). About 22 people experienced cardiovascular events out of every 100 managed for an exacerbation in primary care (25,831 of 119,124) (see Table E2.1 for absolute risks [percentage] and rates).

Crude incidence rates of cardiovascular events

In the whole cohort over all follow-up time, the crude incidence rate of any cardiovascular event was 7.01 per 100 person-years (95% confidence interval [CI], 6.95–7.08). Among patients without exacerbations, the crude rate was 3.66 per 100 person-years (95% CI, 3.58–3.75). Among patients with any exacerbation, the crude rate of cardiovascular events was higher, at 8.79 per 100 person-years (95% CI, 8.70–8.88). The rate of a subsequent cardiovascular event was different by exacerbation severity. Among patients with moderate exacerbations, the rate was 7.79 per 100 person-years (95% CI, 7.69–7.88), whereas among patients with severe exacerbations, the rate was 15.7 per 100 person-years (95% CI, 15.3–16.0).

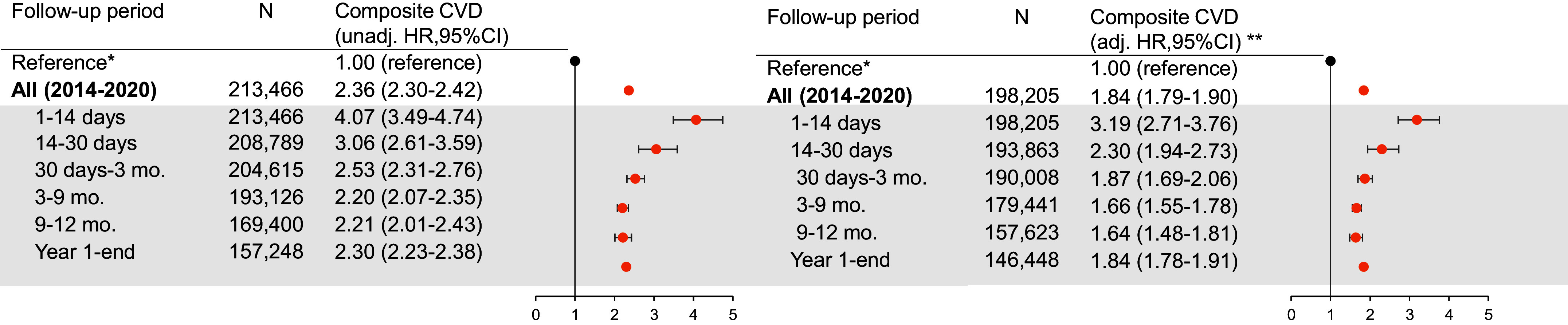

Hazard ratios for composite cardiovascular events

Compared with patients without exacerbations, those with exacerbations had a higher hazard of composite future cardiovascular event over the entire follow-up duration (Figure 3 and Tables E2.1–E2.3). When analyzing by subperiods of time, the relative rate of cardiovascular events peaked in the immediate two weeks after exacerbation (1–14 d; adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 3.19 [95% CI, 2.71–3.76]), followed by declining hazards thereafter but with an elevated hazard ratio (HR) maintained even after the first year (exceeding one year; aHR, 1.84 [95% CI, 1.78–1.91]).

Figure 3.

Forest plot illustrating the association between exacerbation and composite cardiovascular event, overall and by prespecified subperiod of clinical interest. N refers to the number of patients at risk in the respective period (i.e., the denominator). Events (i.e., the numerator) are available in Tables E2.1–E2.3. *The reference estimate representing patients without exacerbations for overall and subperiod effect estimates is an HR of 1.00 regardless of time strata. **Adjusted for all core set covariates. adj. = adjusted; CI = confidence interval; CVD = cardiovascular disease; HR = hazard ratio; unadj. = unadjusted.

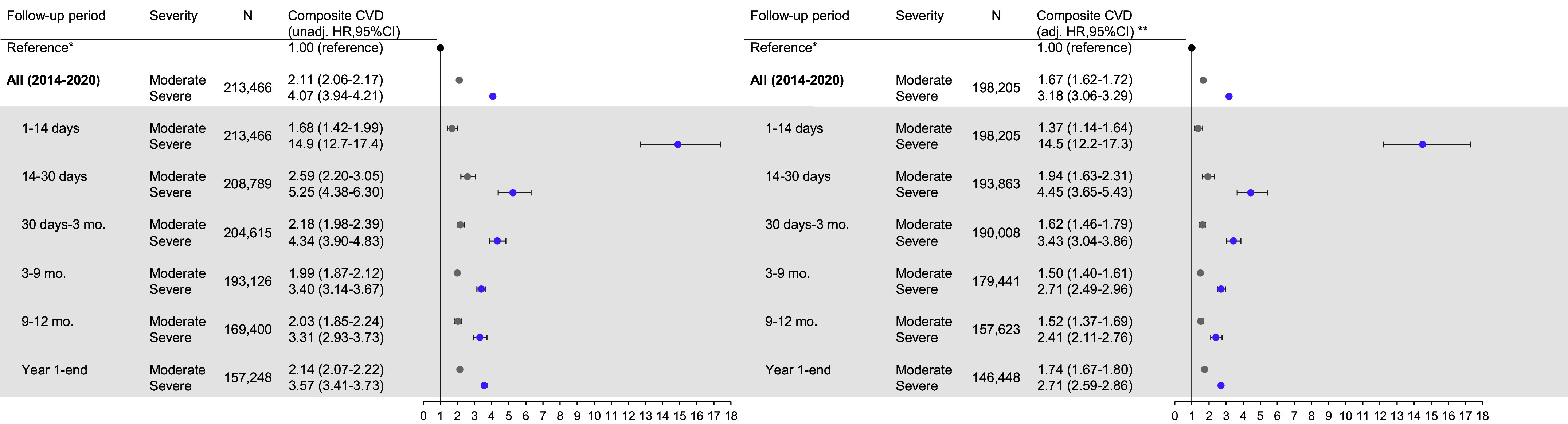

Compared with those without exacerbations, those with severe exacerbations had a higher rate of cardiovascular events in the immediate two weeks after exacerbation (1–14 d; aHR, 14.5 [95% CI, 12.2–17.3]) (Figure 4). For moderate exacerbations, the highest relative rate was in the 14- to 30-day period (14–30 d; aHR, 1.94 [95% CI, 1.63–2.31]) and was attenuated thereafter. For both moderate and severe exacerbations, rates remained statistically significant beyond one year after the exacerbation (aHR for moderate exacerbations, 1.74 [95% CI, 1.67–1.80]; aHR for severe exacerbations, 2.71 [95% CI, 2.59–2.86]) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Forest plot illustrating the association between exacerbation by severity and composite cardiovascular event, overall and by prespecified subperiod of clinical interest. N refers to the number of patients at risk in the respective period (i.e., the denominator). Events (i.e., the numerator) are available in Tables E2.1–E2.3. *Reference estimate representing patients without exacerbations for overall and subperiod effect estimates is an HR of 1.00 regardless of time strata. **Adjusted for all core set covariates. For definition of abbreviations, see Figure 3.

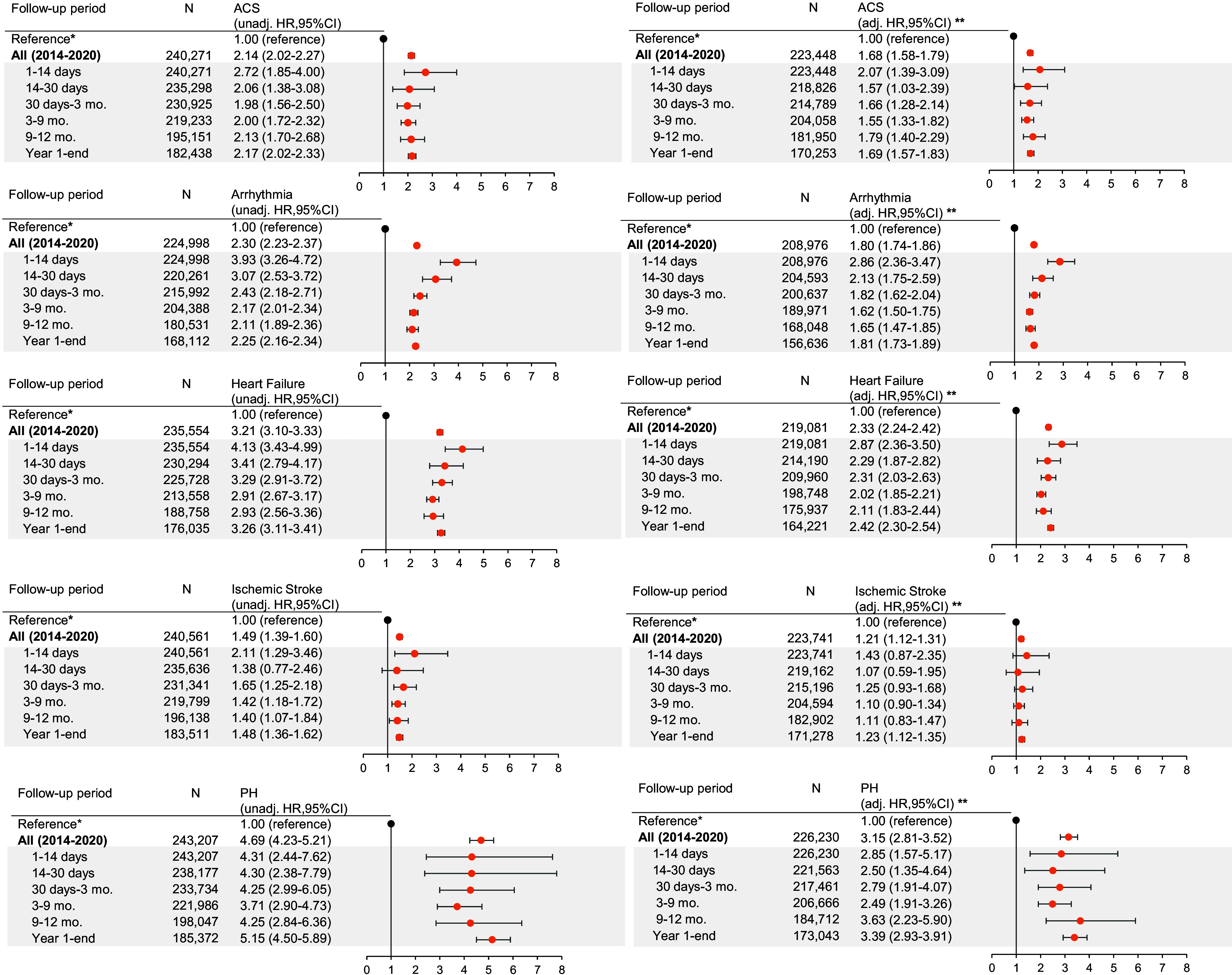

HRs for individual cardiovascular events

Compared with patients without exacerbations, patients who had any exacerbation had an increased relative rate of all individual cardiovascular outcomes, apart from ischemic stroke which had mixed results. HRs across follow-up were highest for PH (aHR, 3.15 [95% CI, 2.81–3.52]), followed by HF (aHR, 2.33 [95% CI, 2.24–2.42]). In the first 14 days after any exacerbation, the highest magnitudes of effects were observed for arrhythmias (aHR, 2.86 [95% CI, 2.36–3.47]), HF (aHR, 2.87 [95% CI, 2.36–3.50]), and PH (aHR, 2.85 [95% CI, 1.57–5.17]) (Figure 5 and Tables E9.1–E9.15).

Figure 5.

Forest plot illustrating the association between exacerbation by each secondary cardiovascular endpoint, overall and by prespecified subperiod of clinical interest. N refers to the number of patients at risk in the respective period (i.e., the denominator). Events (i.e., the numerator) are available in Appendix E9 tables. *Reference estimate representing patients without exacerbations for overall and subperiod effect estimates is an HR of 1.00 regardless of time strata. **Adjusted for all core set covariates. ACS = acute coronary syndrome; adj. = adjusted; CI = confidence interval; CVD = cardiovascular disease; HR = hazard ratio; PH = pulmonary hypertension; unadj. = unadjusted.

Sensitivity Analyses

When adjusting for sensitivity set covariates, HRs were comparable with the core set of covariate-adjusted models (see Tables E2.1–E2.3).

When including patients with prior cardiovascular events in the year before the index date, HRs of cardiovascular events after an exacerbation were lower compared with the main model (see Tables E3.1–E3.3).

When restricting the analysis to people who had only one exacerbation over follow-up, the results remained consistent, but there were modestly higher relative rates within the first two weeks (aHR for any exacerbation, 7.81 [95% CI, 6.65–9.17]; aHR for moderate exacerbation, 3.31 [95% CI, 2.78–3.95]; aHR for severe exacerbation, 27.7 [95% CI, 23.5–32.7]) (see Tables E4.2–E4.3 for time-stratified models and Table E4.1 across follow-up).

When defining the composite outcome without PH, HRs and 95% CIs were equivalent to those in the main model (see Tables E5.1–E5.3).

When including death in the composite outcome definition, absolute risks (percentage) and crude rates across follow-up were higher than in main models, particularly for severe exacerbation.

Relative rates were comparable with those in main models, except for the first month for severe exacerbation, which were slightly higher (aHR for 1–14 d, 17.2 [95% CI, 1.50–19.8]; aHR for 15–30 d, 7.71 [95% CI, 6.66–8.93]) (see Tables E6.1–E6.3).

When including all-cause death as a competing event, the HR of composite cardiovascular event was attenuated compared with main models across time (aHR for any exacerbation, 1.63 [95% CI, 1.57–1.68]; aHR for moderate exacerbation, 1.61 [95% CI, 1.55–1.66]; aHR for severe exacerbation, 1.73 [95% CI, 1.65–1.82]) (see Table E7.1 and Figures E3A and E3B for cumulative incidence function curves).

When we explored the inclusion of patients who had COPD exacerbations and cardiovascular events on the same day, relative rates were remarkably elevated in the first two weeks (see Tables E8.1–E8.3). Of these 9,597 patients, 9,401 (98%) had severe exacerbations.

Exploratory Analysis

We found that 0.2% of patients (13 of 6,274) experienced the cardiovascular outcome within the same hospitalization as for exacerbations.

Discussion

Principal Findings

This is the first study using a generalizable primary care–defined COPD cohort to determine absolute and relative rates of specific nonfatal cardiovascular events after both moderate and severe COPD exacerbations, split into relatively short time periods over long-term follow-up, with sufficient power to explore multiple individual cardiovascular outcomes temporally. We observed an increased, immediate risk for composite and individual cardiovascular outcomes after an exacerbation, a risk distinctively elevated with severe exacerbations compared with moderate exacerbations, with risk occurring later after a moderate exacerbation and with sustained risk even after one year of follow-up irrespective of severity. Scaling our findings up to the wider COPD population, approximately 28 people will experience at least one cardiovascular event out of every 100 hospitalized exacerbations and 22 out of every 100 primary care exacerbations.

We observed a distinctively higher magnitude of effect among patients with severe rather than moderate exacerbations. For all individual outcomes, HRs were highest after severe exacerbations in 1–14 days, attenuating but remaining statistically significant even after one year. The two-week HRs were highest for arrhythmia and HF. This heightened risk may be due to impaired gas exchange secondary to exacerbation, leading to a hypoxemic state or, alternatively, treatments used for exacerbation (e.g., increased short-acting β-agonist use or oral corticosteroids) may play a role (26). The attenuated and mixed associations across time for ischemic stroke could be explained by factors for stroke such as arrhythmia being identified and treated (27). It is likely that exacerbations requiring hospitalization are associated with a greater inflammatory response, and this may explain why we find an increased rate of events overall in this group. It is also possible that people are more heightened to their symptoms having been in the hospital and therefore have a lower threshold for seeking health care with ongoing or new symptoms. It is plausible that after severe exacerbations, patients have vigilant monitoring (8), but our exploratory analysis revealed that only 0.2% of patients with severe exacerbations experienced cardiovascular events within the same hospitalization as the exacerbation.

Cardiovascular events after moderate exacerbations occurred slightly later, with the highest risk for HF, PH, and ACS, not appearing until after two weeks, after 1 month, and after 3 months, respectively. The relative rate of arrhythmia was again highest in the 1–14 days after an exacerbation, and evidence of association was maintained across time. This may be for similar mechanistic reasons to those seen after a severe exacerbation. It could be that for HF, PH, and particularly ACS, it takes time for the accumulation of lower intensity inflammation to take effect, before imposing an increased cardiovascular risk, with longer term inflammatory mechanisms important. It is also possible that there is some misdiagnosis or delayed diagnosis or misclassification of cardiovascular and exacerbation events given the overlap in symptoms and a lack of cardiovascular investigations readily available in primary care (8, 28–30). There may also be a delay in health care–seeking behavior or a false reassurance that symptoms related to new cardiovascular events are being attributed to the COPD exacerbation. Given the delay, there may be opportunities to intervene or proactively diagnose these events earlier to start treatment and ultimately improve outcomes. There was no association between a moderate exacerbation and subsequent stroke.

Relative rates’ remaining elevated after one year is an interesting finding. Previous studies have had shorter follow-up, either between one and six months (8, 11, 13, 14, 18) or only up to one year (9, 15, 16), with time cuts of less than a week for many of the shorter length studies (8, 9, 12, 14, 16). These studies with multiple subperiods revealed no increase in risk within or by the first year (8, 9, 12, 14, 16), unlike the sustained associations we observed across time. Reasons for this discrepancy may be due partly to study cohorts. All studies included only patients with worse clinical prognoses, requiring people to have histories of exacerbation (8, 14, 16) or cardiovascular histories (18). Other studies were post hoc trial analysis in which there were specific inclusion criteria (9, 12).

Defining solely nonfatal events also allowed us to better understand the clinical implications and important time points for intervention after exacerbation. In post hoc analyses of clinical trials (9, 12, 13), a case-crossover study (11), and one small registry-based study (18), including mortality in outcomes revealed higher magnitudes of effect than our findings, particularly for severe exacerbations (9). We performed a sensitivity analysis including death as a competing event, observing overall attenuation of HR magnitude. We performed a sensitivity analysis including death as part of our composite endpoint, and we found higher absolute measures (risk percentage, rate) and comparable relative rates except for the first month for severe exacerbation. This aligns with what we anticipated, as we expanded the outcome definition (i.e., more events) and as the greater magnitude in relative effects within the first month for severe exacerbation reinforces the urgency of taking immediate preventive measures, particularly for exacerbations occurring in the hospital.

Studies exploring the risk of arrhythmias after COPD exacerbation are limited. Only three small studies have investigated an relationship between COPD exacerbation and cardiovascular events for AF. These studies were all small in size and did not include both primary care–managed and hospitalized exacerbations (13, 15, 16). Our subperiod HRs in the first 3 months are comparable with the 1- to 90-day incidence rates seen in a U.S. study examining AF with hospitalized exacerbation (16), but no association was observed past 90 days, unlike the sustained effect sizes we observed. These differences could be due to our broader definition of nonfatal arrhythmia, where 35% were AF/atrial flutter, and the remaining encompassed nonfatal cardiac arrest and other types of arrhythmias. Alternatively, the inclusion criteria of the U.S. study (16) required a history of AF and exacerbation; these patients are likely receiving treatment for their condition, which may reduce long-term cardiovascular risk. Our results are comparable with those of Halpin and colleagues’ post hoc, subgroup analysis among patients without cardiac disorder at baseline (1–180 days: 3.73 [95% CI, 0.77–17.9]) (13). In our sensitivity analyses including these patients with prior incident cardiovascular events, we observed dampened HRs, likely because people with recent cardiovascular history, if appropriately treated, have reduced cardiovascular risk. Interestingly, however, we did not observe differences in the distribution of cardiovascular medication status relative to the main cohort.

The general attenuation or lack of association for ischemic stroke is also novel and differs from most studies in which associations were observed (8, 11, 13, 15, 17). Again, these prior studies did not always include generalizable patient populations and were either post hoc analyses (13) or used self-controlled designs (8, 11, 15). Our results concur with two United Kingdom studies, a small study in The Health Improvement Network database (14) and an earlier case–control study using primary care data investigating the role of ischemic stroke with exacerbation frequency (10). The associations observed in previous studies could be due in part to residual confounding (17).

Our observations of delayed and sustained temporal effects for ACS, HF, and PH are different from those reported in previous literature (8, 11, 13–15), particularly as no previous studies have explored the relative effects of PH after exacerbation in this way. In the two United Kingdom self-controlled studies stratifying on time after exacerbation, MI risk shortly returned to baseline by one week (14) and, in our previous self-controlled case series, by one month (8). Although there are studies that reported average three-month effect sizes for MI (11, 13), angina (13), and HF (13, 15), and for MI and HF up to one year (15), they did not measure multiple and subsequent subperiods, and again, are all post hoc trial analyses or self-controlled designs.

Strengths and Limitations

In general, completeness in diagnostic recording in CPRD is high, and missing information on exposure or outcome is unlikely (31). To limit misclassification we used standardizable methods (25) and, when possible, previously validated and/or tested methods (22–24, 32–35), including validated definitions for COPD and COPD exacerbations or used a pulmonologist and/or cardiologist to review all code lists and definitions. Our use of routine primary care data allows our results to be generalizable to the wider COPD population and representative of United Kingdom patients, given that COPD diagnosis and management in the United Kingdom takes place predominantly in primary care. We used primary care data to define prior CVD covariates to best capture existing, lifelong concomitant CVD with COPD.

Still, limitations are possible, and residual confounding is inevitable. We undertook sensitivity analyses to include variables with substantial missingness that we believed might be important, and this had a minimal effect on the effect sizes seen. Confounders were not time updated, and we are aware that in exploring stratified HRs beyond one year, time varying exposures should be included. However, given the relatively short follow-up time, we assumed covariate status would not change remarkably. Finally, we acknowledge that we explored many outcomes in this study and therefore applied Bonferroni corrections, reporting P values in the online supplement.

Although we recognize that individuals with lower socioeconomic status may have reduced healthcare access and/or reduced monitoring of their conditions, particularly around diagnosis of COPD, given the use of an open cohort in which 65.7% of the population had prevalent disease, we do not believe that first exacerbation recording is likely to differ by socioeconomic status in this dataset. Indeed, previous cardiovascular studies have shown this not to be the case (36). We acknowledge the possibility of misdiagnosis or misclassification of COPD exacerbations with cardiovascular events and that this misclassification could go in either direction (28, 37, 38). In particular, it could lead to an overestimation of cardiovascular hospitalization rate for hospitalized exacerbations and an underestimation of cardiovascular event rate in the no-exacerbation group. However, as with all EHR research, we are ultimately limited by the clinical accuracy and the ultimate diagnosis made by the physician seeing the patient. Data were not available to enable case review to adjudicate definitions. In a previous study, people with exacerbations were more likely to be prescribed diuretics than people without exacerbations (28). Given that diuretics can serve as an early indication of possible HF in COPD, this suggests that there could have been delayed HF misdiagnosed as COPD exacerbations diagnosis in COPD (28). Echocardiography, although a diagnostic standard for the diagnosis of HF, is not routinely undertaken in primary care and when performed in secondary care is usually returned to the GP in letter format rather than the detail entered in a coded format to the primary care record, and therefore we cannot always see the detail for research purposes. Echocardiography is also not routinely undertaken at the time of an admission for a COPD exacerbation. Previous research on the validation of HF with reduced ejection fraction within another United Kingdom primary care–based EHR database (The Health Improvement Network) demonstrated that there was little difference in positive predictive value when including a general HF code, guideline-directed medical therapy, and evidence of echocardiography (91.7%) compared with including only a general HF code and guideline-directed medical therapy, without evidence of echocardiography (87.5%) (39).

We acknowledge the challenges of diagnosing and defining PH in health data, and although we used routinely collected EHR data, we could access only the structured EHR data (i.e., not free text) and therefore may have missed detailed information around PH diagnosis. However, when removing PH from the composite analysis in a sensitivity analysis, effect estimates remained unchanged. We believe that these results are useful for hypothesis generation in future studies.

We were unable to include sleep apnea as a covariate because of data sparsity, although it is common in people with COPD and a risk factor for CVD (40). We found a prevalence of 2.3% of sleep apnea in our study, which is much lower than has been previously reported (40). Similarly, we were unable adjust for long-term oxygen because of data sparsity, despite its common use among people with COPD and its being an indicator of disease severity. In our cohort, only 0.45% of people had evidence of any long-term oxygen use. This underestimate is due to the way in which oxygen services are commissioned and recorded in the United Kingdom. Together, by not adjusting for sleep apnea and long-term oxygen, we may have overestimated the effect estimates, as these factors may explain some of the association we observe. However we adjusted for other severity markers in main analyses (i.e., COPD medications and exacerbation frequency) and in sensitivity analyses (i.e., GOLD grade of airflow limitation and MRC dyspnea score), so there is likely minimal residual confounding due to respiratory-related disease severity.

Although studies using EHR data are useful in studying populations generalizable to the wider population of patients seen in everyday clinical practice, they do have limitations, and results should be interpreted with caution. CPRD data were not collected for the purpose of research, and further studies, for example, pragmatic randomized controlled trials, should be performed to better understand the relationship between COPD exacerbations and CVD.

Clinical Implications

The time immediately after an exacerbation presents a finite, critical window of opportunity for intervention to prevent and treat cardiovascular events as well as to prevent future COPD exacerbations (7, 41). However, current guidance points to general cardiovascular guidelines, not considering complexities when considering a second organ system (1, 2, 42). Given the novel finding of sustained HRs beyond a year after exacerbation irrespective of exacerbation severity, long-term cardiovascular health should be prioritized in addition to reducing exacerbation events and optimizing COPD management. If we can proactively screen for cardiac state (e.g., using echocardiography) in patients with COPD, perhaps we can treat and or prevent future events. Incorporating routine screening for patients with histories of exacerbation documented in their GP records, even if the exacerbation occurred greater than a year prior, is worth considering. Heightened awareness for arrhythmia immediately after exacerbation should be considered.

Conclusions

Acute exacerbations of COPD are associated with an increased relative rate of cardiovascular events. The highest relative effects were observed in the immediate wake of an exacerbation but still maintained after one year. These findings highlight the interconnectedness of COPD and CVD. Although there is a clear window of opportunity for prompt clinical intervention and treatment optimization after an exacerbation, continued recognition and optimization is important for reducing this long-term cardiopulmonary risk. The prevention of COPD exacerbations may ultimately help reduce cardiovascular risk.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

This work is based on data from the CPRD obtained under license from the United Kingdom Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency. The data are provided by patients and collected by the National Health Service as part of their care and support. The interpretation and conclusions contained in this study are those of the authors alone.

Footnotes

Supported by AstraZeneca.

Author Contributions: E.L.G., J.K.Q., C.N., K.R., S.M., and J.M. conceptualized the study and designed the protocol. J.K.Q., N.S.P., and E.L.G. contributed to the development of the code lists that defined the study variables. E.L.G., C.K., and H.R.W. contributed to the methodology. E.L.G., H.R.W., C.K., and A.E.I. accessed and verified the data. E.L.G., H.R.W., C.K., and A.E.I. were responsible for data curation and management. E.L.G., H.R.W., C.K., and A.E.I. were responsible for formal analysis. E.L.G. wrote the original draft of the manuscript. E.L.G. and H.R.W. contributed to data visualization. All authors contributed to and approved the final manuscript. All authors had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Data availability statement: Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available. Data are available on request from the Clinical Practice Research Datalink. Their provision requires the purchase of a license, and this license does not permit the authors to make them publicly available to all.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.202307-1122OC on December 21, 2023

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1. Sethi S. Is it the heart or the lung? Sometimes it is both. J Am Heart Assoc . 2022;11:e027112. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.122.027112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Morgan AD, Zakeri R, Quint JK. Defining the relationship between COPD and CVD: what are the implications for clinical practice? Ther Adv Respir Dis . 2018;12:1753465817750524. doi: 10.1177/1753465817750524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Balbirsingh V, Mohammed AS, Turner AM, Newnham M. Cardiovascular disease in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a narrative review. Thorax . 2022;77:939–945. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2021-218333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Müllerova H, Agusti A, Erqou S, Mapel DW. Cardiovascular comorbidity in COPD: systematic literature review. Chest . 2013;144:1163–1178. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-2847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Morgan AD, Rothnie KJ, Bhaskaran K, Smeeth L, Quint JK. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and the risk of 12 cardiovascular diseases: a population-based study using UK primary care data. Thorax . 2018;73:877–879. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2017-210865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Müllerová H, Marshall J, de Nigris E, Varghese P, Pooley N, Embleton N, et al. Association of COPD exacerbations and acute cardiovascular events: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ther Adv Respir Dis . 2022;16:17534666221113647. doi: 10.1177/17534666221113647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Whittaker H, Rubino A, Müllerová H, Morris T, Varghese P, Xu Y, et al. Frequency and severity of exacerbations of COPD associated with future risk of exacerbations and mortality: a UK routine health care data study. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis . 2022;17:427–437. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S346591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rothnie KJ, Connell O, Müllerová H, Smeeth L, Pearce N, Douglas I, et al. Myocardial infarction and ischemic stroke after exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2018;15:935–946. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201710-815OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dransfield MT, Criner GJ, Halpin DMG, Han MK, Hartley B, Kalhan R, et al. Time-dependent risk of cardiovascular events following an exacerbation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: post hoc analysis from the IMPACT trial. J Am Heart Assoc . 2022;11:e024350. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.121.024350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Quint J, Windsor C, Herrett E, Smeeth L. No association between exacerbation frequency and stroke in patients with COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis . 2016;11:217–225. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S95775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Reilev M, Pottegård A, Lykkegaard J, Søndergaard J, Ingebrigtsen TS, Hallas J. Increased risk of major adverse cardiac events following the onset of acute exacerbations of COPD. Respirology . 2019;24:1183–1190. doi: 10.1111/resp.13620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kunisaki KM, Dransfield MT, Anderson JA, Brook RD, Calverley PMA, Celli BR, et al. SUMMIT Investigators Exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and cardiac events: a post hoc cohort analysis from the SUMMIT randomized clinical trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2018;198:51–57. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201711-2239OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Halpin DMG, Decramer M, Celli B, Kesten S, Leimer I, Tashkin DP. Risk of nonlower respiratory serious adverse events following COPD exacerbations in the 4-year UPLIFT® trial. Lung . 2011;189:261–268. doi: 10.1007/s00408-011-9301-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Donaldson GC, Hurst JR, Smith CJ, Hubbard RB, Wedzicha JA. Increased risk of myocardial infarction and stroke following exacerbation of COPD. Chest . 2010;137:1091–1097. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-2029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Goto T, Shimada YJ, Faridi MK, Camargo CA, Jr, Hasegawa K. Incidence of acute cardiovascular event after acute exacerbation of COPD. J Gen Intern Med . 2018;33:1461–1468. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4518-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hirayama A, Goto T, Shimada YJ, Faridi MK, Camargo CA, Jr, Hasegawa K. Acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and subsequent risk of emergency department visits and hospitalizations for atrial fibrillation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol . 2018;11:e006322. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.118.006322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Portegies MLP, Lahousse L, Joos GF, Hofman A, Koudstaal PJ, Stricker BH, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and the risk of stroke: the Rotterdam study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2016;193:251–258. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201505-0962OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Løkke A, Hilberg O, Lange P, Ibsen R, Telg G, Stratelis G, et al. Exacerbations predict severe cardiovascular events in patients with COPD and stable cardiovascular disease—a nationwide, population-based cohort study. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2023;18:419–429. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S396790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nordon C, Rhodes K, Quint JK, Vogelmeier CF, Simons SO, Hawkins NM, et al. Exacerbations of COPD and Their OutcomeS on Cardiovascular Diseases (EXACOS-CV) Programme: protocol of multicountry observational cohort studies. BMJ Open . 2023;13:e070022. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-070022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency. 2022. https://cprd.com/cprd-aurum-may-2022-dataset

- 21. Herrett E, Gallagher AM, Bhaskaran K, Forbes H, Mathur R, van Staa T, et al. Data resource profile: Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) Int J Epidemiol . 2015;44:827–836. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyv098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Quint JK, Müllerova H, DiSantostefano RL, Forbes H, Eaton S, Hurst JR, et al. Validation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease recording in the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD-GOLD) BMJ Open . 2014;4:e005540. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rothnie KJ, Müllerová H, Hurst JR, Smeeth L, Davis K, Thomas SL, et al. Validation of the recording of acute exacerbations of COPD in UK primary care electronic healthcare records. PLoS One . 2016;11:e0151357. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rothnie KJ, Müllerová H, Thomas SL, Chandan JS, Smeeth L, Hurst JR, et al. Recording of hospitalizations for acute exacerbations of COPD in UK electronic health care records. Clin Epidemiol. 2016;8:771–782. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S117867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Graul EL, Stone PW, Massen GM, Hatam S, Adamson A, Denaxas S, et al. Determining prescriptions in electronic healthcare record data: methods for development of standardized, reproducible drug codelists. JAMIA Open . 2023;6:ooad078. doi: 10.1093/jamiaopen/ooad078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Amegadzie JE, Gamble J-M, Farrell J, Gao Z. Association between inhaled β2-agonists initiation and risk of major adverse cardiovascular events: a population-based nested case-control study. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis . 2022;17:1205–1217. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S358927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hald EM, Rinde LB, Løchen ML, Mathiesen EB, Wilsgaard T, Njølstad I, et al. Atrial fibrillation and cause-specific risks of pulmonary embolism and ischemic stroke. J Am Heart Assoc . 2018;7:e006502. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.006502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Axson EL, Bottle A, Cowie MR, Quint JK. Relationship between heart failure and the risk of acute exacerbation of COPD. Thorax . 2021;76:807–814. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2020-216390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rothnie KJ, Smeeth L, Herrett E, Pearce N, Hemingway H, Wedzicha J, et al. Closing the mortality gap after a myocardial infarction in people with and without chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Heart . 2015;101:1103–1110. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2014-307251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rothnie KJ, Müllerová H, Smeeth L, Quint JK. Natural history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations in a general practice-based population with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2018;198:464–471. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201710-2029OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Herrett E, Thomas SL, Schoonen WM, Smeeth L, Hall AJ. Validation and validity of diagnoses in the General Practice Research Database: a systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol . 2010;69:4–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2009.03537.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mathur R, Bhaskaran K, Chaturvedi N, Leon DA, vanStaa T, Grundy E, et al. Completeness and usability of ethnicity data in UK-based primary care and hospital databases. J Public Health (Oxf) . 2014;36:684–692. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdt116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Farmer R, Mathur R, Bhaskaran K, Eastwood SV, Chaturvedi N, Smeeth L. Promises and pitfalls of electronic health record analysis. Diabetologia . 2018;61:1241–1248. doi: 10.1007/s00125-017-4518-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nissen F, Morales DR, Mullerova H, Smeeth L, Douglas IJ, Quint JK. Concomitant diagnosis of asthma and COPD: a quantitative study in UK primary care. Br J Gen Pract . 2018;68:e775–e782. doi: 10.3399/bjgp18X699389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cook S, Schmedt N, Broughton J, Kalra PA, Tomlinson LA, Quint JK. Characterising the burden of chronic kidney disease among people with type 2 diabetes in England: a cohort study using the Clinical Practice Research Datalink. BMJ Open . 2023;13:e065927. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-065927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hawkins NM, Scholes S, Bajekal M, Love H, O’Flaherty M, Raine R, et al. The UK National Health Service: delivering equitable treatment across the spectrum of coronary disease. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes . 2013;6:208–216. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.111.000058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Matsumoto K, Read N, Philip KEJ, Allinson JP. Exacerbations in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: clinical, genetic, and mycobiome risk factors. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2023;208:487–489. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202303-0581RR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Celli BR, Fabbri LM, Aaron SD, Agusti A, Brook RD, Criner GJ, et al. Differential diagnosis of suspected chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations in the acute care setting: best practice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2023;207:1134–1144. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202209-1795CI. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sundaram V, Zakeri R, Witte KK, Quint JK. Development of algorithms for determining heart failure with reduced and preserved ejection fraction using nationwide electronic healthcare records in the UK. Open Heart . 2022;9:e002142. doi: 10.1136/openhrt-2022-002142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Raphelson JR, Sanchez-Azofra A, Malhotra A. Sleep apnea and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease overlap: more common than you think? Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2023;208:505–506. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202305-0833LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Whittaker H, Nordon C, Rubino A, Morris T, Xu Y, De Nigris E, et al. Frequency and severity of respiratory infections prior to COPD diagnosis and risk of subsequent postdiagnosis COPD exacerbations and mortality: EXACOS-UK health care data study. Thorax . 2023;78:760–766. doi: 10.1136/thorax-2022-219039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Agusti A, Böhm M, Celli B, Criner GJ, Garcia-Alvarez A, Martinez F, et al. GOLD COPD document 2023: a brief update for practicing cardiologists. Clin Res Cardiol . 2023 doi: 10.1007/s00392-023-02217-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]