Summary:

TGF-β, essential for development and immunity, is expressed as a latent complex (L-TGF-β) non-covalently associated with its prodomain and presented on immune cell surfaces by covalent association with GARP. Binding to integrin αvβ8 activates L-TGF-β1/GARP. The dogma is that mature TGF-β must physically dissociate from L-TGF-β1 for signaling to occur. Our previous studies discovered that αvβ8-mediated TGF-β autocrine signaling can occur without TGF-β1 release from its latent form. Here, we show mice engineered to express TGF-β1 that cannot release from L-TGF-β1 survive without early lethal tissue inflammation of TGF-β1 deficiency. Combining cryogenic electron microscopy with cell-based assays we reveal a dynamic allosteric mechanism of autocrine TGF-β1 signaling without release where αvβ8 binding redistributes intrinsic flexibility of L-TGF-β1 to expose TGF-β1 to its receptors. Dynamic allostery explains the TGF-β3 latency/activation mechanism and why TGF-β3 functions distinctly from TGF-β1, suggesting it broadly applies to other flexible cell surface receptor/ligand systems.

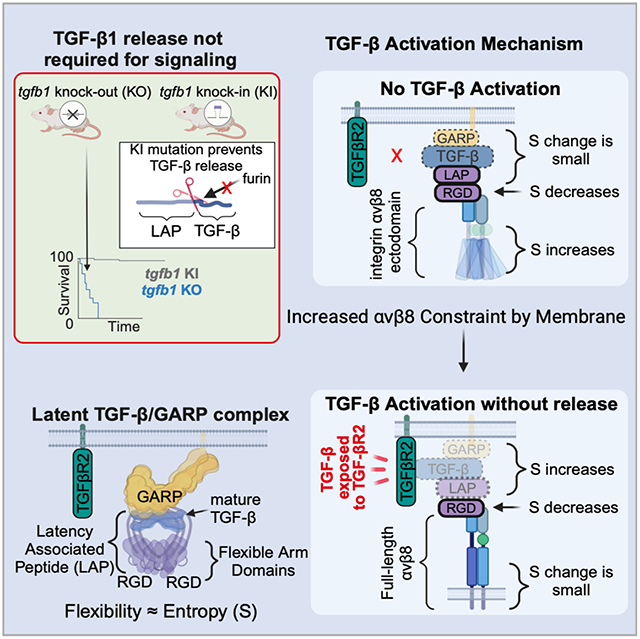

Graphical Abstract

In Brief:

Genetically engineered mice survive with only autocrine but no paracrine TGF-β1 signaling. Structural and functional studies reveal a mechanism for TGF-β1 autocrine signaling driven by conformational entropy redistribution from αvβ8 binding to latent TGF-β1/GARP complex. Integrin-mediated entropy redistribution also underlies TGF-β3 activation suggesting a general mechanism of cell-cell communication.

Introduction:

Transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β1) is a multifunctional cytokine with key roles in development, immunity, cancer, and fibrosis1–3. TGF-β has three distinct gene products (TGF-β1, -β1, and -β3) all expressed in inactive (latent) forms (L-TGF-β) and “activation” is essential for function4. Most therapeutic TGF-β targeting strategies have not focused on specific latency and/or activation mechanisms, but rather on global inhibition of TGF-β signaling and have significant toxicities3. Improved understanding of latency and activation may facilitate better therapeutic approaches targeting TGF-β.

Latency of mature TGF-β is determined by non-covalent association with its N-terminal prodomain cleaved by furin during biosynthesis5,6. The prodomain encircles mature TGF-β homodimer in a ring-shaped disulfide linked homodimer “straitjacket”, (latency-associated peptide, LAP), forming L-TGF-β5. LAPs serve four essential functions: 1) conferring latency through shielding mature TGF-β from its receptors via the lasso domains of the straitjacket5; 2) sequestering L-TGF-β to the matrix or cell-surface through binding to TGF-β milieu molecules such as GARP, which stabilizes and covalently links L-TGF-β to cell surfaces7–9; 3) facilitating proper folding and efficient secretion10; 4) binding to essential activating proteins, in particular, integrins1,11.

Active mature TGF-βs are disulfide-linked homodimers highly conserved in TGF-β receptor (TGF-βR) binding domains, particularly mature TGF-β1 and -β3, which bind with similar affinities to TGF-β receptors (TGF-βR1/TGF-βR2)12,13. Despite this conservation, mice deficient in TGF-β1 or TGF-β3 have distinct phenotypes, potentially due to individual mechanisms of latency and/or activation as predicted by overall low homology between LAPs of TGF-β1 and -β3 (Figure S1)14–17. Interestingly, both TGF-β1 and -β3 LAPs contain the integrin binding motif RGDLXXL/I and bind to two integrins, αvβ6 and αvβ8, which together account for the majority of TGF-β1, and some of TGF-β3 function, in vivo11,18,19. Integrin binding culminates in TGF-β activation leading to autocrine20 or paracrine21 TGF-β signaling by mechanisms that remain speculative18,19,22,23.

Structural and sequence differences between integrins αvβ6 and αvβ8 suggest distinct mechanisms of TGF-β activation likely contributing to context-specific functions of TGF-β11,18,19,22,24–26. In the case of αvβ6, global conformational changes transduce force from the actin-cytoskeleton to L-TGF-β disrupting LAP allowing release of mature TGF-β for paracrine signaling23. This mechanism requires the highly conserved β6-subunit cytoplasmic domain, which binds the actin cytoskeleton19. However, released mature TGF-β1 from αvβ8-mediated activation is difficult to detect, indicating inefficient paracrine TGF-β1 signaling22,27. Accordingly, αvβ8 does not undergo global conformational changes28,29, αvβ8-mediated TGF-β1 activation does not require actin-cytoskeleton force generation, since β8 cytoplasmic domain is not required for activation, and does not bind to actin18. Our previous work revealed that αvβ8 binding induces flexibility in the L-TGF-β1 straitjacket leading us to hypothesize that mature TGF-β1 can be activated without release from the latent complex, which we confirmed in cell-based assays22. Thus, we hypothesized that flexibility generated by binding L-TGF-β1 to αvβ8 is sufficient to expose mature TGF-β1 to TGF-βRs for autocrine signaling without being released22. Yet, it remains unclear how without mechanical force, αvβ8 binding mechanistically induces L-TGF-β flexibility when L-TGF-β is stabilized by binding to GARP, and whether such a mechanism is physiologically relevant, as it is widely assumed that release and paracrine signaling of TGF-β is required for its function1.

In this study, we first validate autocrine signaling without TGF-β1 release is physiologically relevant. We engineer knock-in mice globally expressing only tgfb1 with a mutated furin cleavage site that cannot release TGF-β1. TGF-β signaling in these mice remains intact as they survive, breed, and are spared from lethal early tissue inflammation of TGF-β1 deficiency, proving that mature TGF-β bound to its latent complex can be activated, bind to its receptors and signal30. We next pursue the mechanism allowing TGF-β1 to bind to TGF-βRs without release. We describe a dynamic allosteric model whereby, upon binding to αvβ8, reduction of local conformational entropy around the L-TGF-β RGD binding region increases conformational entropy around distal regions of L-TGF-β/GARP, exposing mature TGF-β to TGF-βRs without release. In support of this model, we determine structures of L-TGF-β3/GARP showing the degree of basal conformational entropy of L-TGF-β1 and -β3 not only determines the basal level of integrin independent TGF-β activation, but also entropy available to drive integrin-dependent TGF-β activation. Higher levels of integrin-mediated entropic change in L-TGF-β3 than -β1 result in paracrine release of mature TGF-β3 but not -β1, indicating isoform-specific mechanisms of autocrine and paracrine TGF-β signaling. Furthermore, the direction of entropy redistribution can be manipulated by stabilizing different flexible domains of αvβ8/L-TGF-β/GARP. Overall, our structural and cell-based approaches reveal a protein dynamic-based allosteric mechanism of redistributing conformational entropy at large distances across protein complexes that is actin cytoskeletal force-independent and determines autocrine and paracrine TGF-β functions. Together, these results advance mechanistic understanding of latency and activation of TGF-β family members providing a roadmap for structural understanding of protein dynamic-mediated signal propagation through flexible cell surface proteins.

Results:

Autocrine TGF-β1 signaling without release prevents lethal tissue inflammation caused by global TGF-β1 deficiency

TGF-β signals through both autocrine and paracrine mechanisms (Figure 1A). TGF-β1 deficient mice lack both autocrine and paracrine TGF-β1 signaling from all cells and die early of widespread tissue inflammation (Figure 1B)30. This is attributed to TGF-β signaling in T-cells, since this same phenotype is observed when TGF-β receptors are deleted from T-cells31,32. Whether T-cells receive primarily autocrine or paracrine TGF-β1 signals is not well understood. Our recent structural and cell-based studies demonstrated that TGF-β1 release was not required for autocrine TGF-β1 signaling22. We test the physiological significance of this finding by creating mice with a mutation in the canonical furin recognition sequence (275RXRR278↓) in TGF-β1 (tgfb1R278A/R278A) that cannot cleave mature TGF-β1 from LAP and are thus only capable of autocrine but not paracrine signaling (Figure 1C–F, S2). We hypothesize that if non-released mature TGF-β1 productively binds to TGF-βRs and induces autocrine signaling, mutant mice are rescued from universal early lethal tissue inflammation of TGF-β1 deficiency30. Tgfb1−/− mice begin to show signs of wasting by 10–14 days and die within 24 days (Figure 1G, H). Tgfb1R278A/R278A mice are phenotypically indistinguishable from tgfb1R278A/WT and WT littermates up to 240 days (at the time of this manuscript submission) showing similar post-natal survival, and weight gain (Figure 1H–J). Genetic approaches to determine the in vivo role of TGF-β1 are confounded by contributions of maternal endocrine TGF-β1 supplied transplacentally during development and after birth through breast milk. Maternal derived TGF-β1 from tgfb1−/− dams partially compensates for fetal TGF-β1 deficiency allowing tgfb1−/− mice to be born alive and survive until weaning before succumbing to autoimmunity30,33. When maternal TGF-β1 is absent, tgfb1−/− mice die immediately after birth34. We demonstrate endocrine release of cleaved mature TGF-β from maternal sources is dispensable since tgfb1R278A/R278A mice can be derived from homozygous tgfb1R278A/R278A dams and show similar post-natal survival, gain weight, and are phenotypically indistinguishable from tgfb1R278A/R278A mice born from tgfb1R278A/WT dams (Figure 1J, Movie S1). The organs of tgfb1R278A/R278A mice are histologically indistinguishable from WT and tgfb1R278A/WT mice, in contrast with tgfb1−/− mice, which display massive immune infiltration of heart, liver and lungs (Figure 1K, L, Table S1). Therefore, autocrine TGF-β1 signaling without release rescues the early lethal tissue inflammation of TGF-β1 deficiency, and endocrine or paracrine release of TGF-β1 is not involved or required for this rescue.

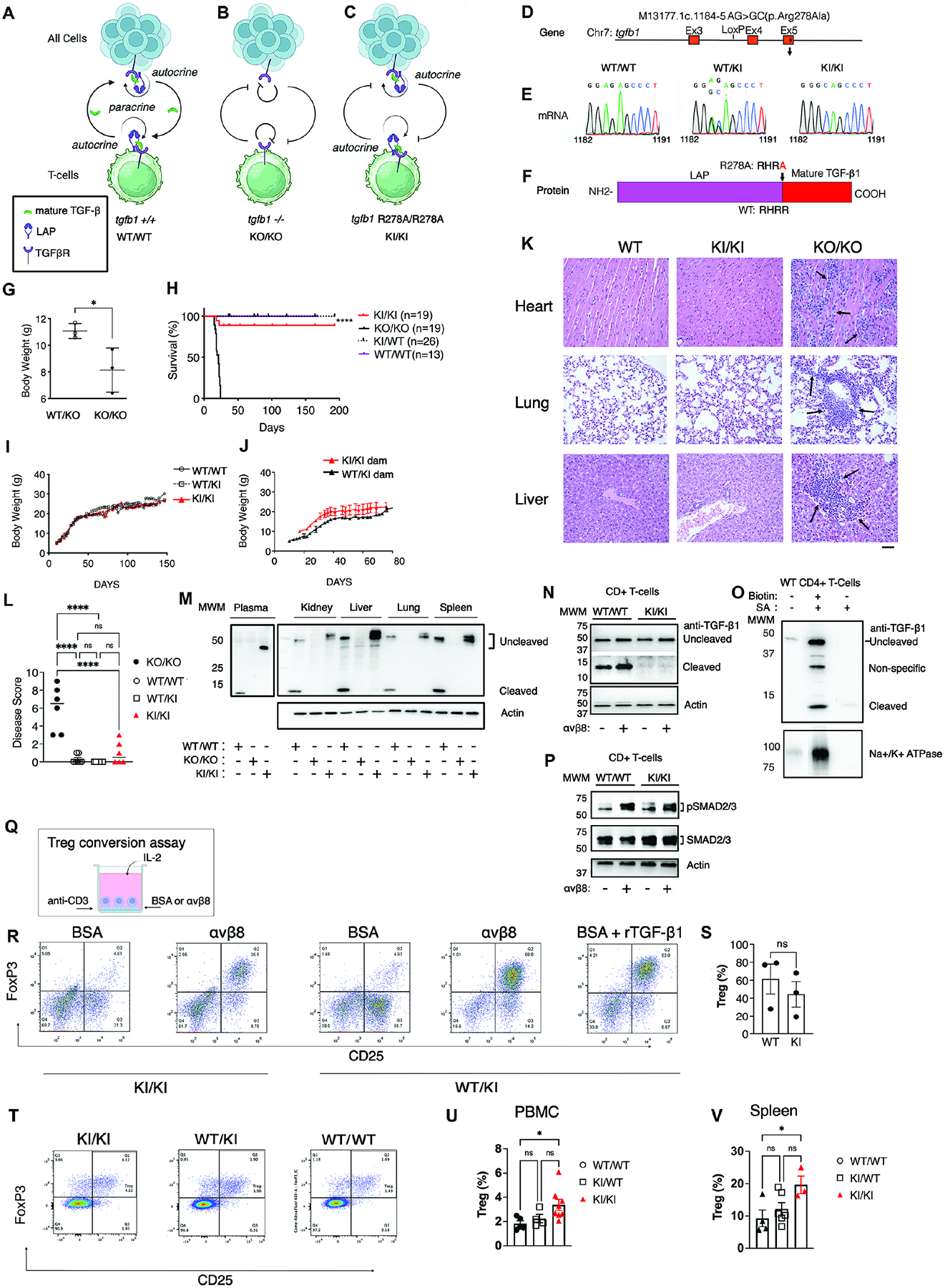

Figure 1. Autocrine TGF-β1 signaling without release prevents lethal tissue inflammation caused by global TGF-β1 deficiency.

(A-C) Cartoons of autocrine and paracrine TGF-β1 signaling in wild type (WT/WT, A), tgfb1−/− (KO/KO, B) and knock-in (KI/KI, C) mice with furin cleavage site mutation (tgfbR278A/R278A). Inset shows symbol key. KI/KI mice generated as in Figure S2A.

(D) Schematic showing location of recombined targeted tgfb1 locus on chromosome 7 (GenBank: M13177.1).

(E) Sequencing chromatograms of WT/WT, WT/KI and KI/KI mice with corresponding sequence shown above.

(F) Schematic of one TGF-β1 protein monomer and position of LAP, furin cleavage site, mutated R278A sequence, and mature TGF-β1 peptide.

(G) Body weights of KO/KO mice at post-natal day 18 compared to littermate WT/KO controls. Shown is the mean and standard error (s.e.m.). *p<0.05 Student’s t-test.

(H) KI/KI, WT/KI and WT/WT mice survive to adulthood compared to KO/KO mice which die by 24 days of multiorgan inflammation. **** p<0.0001 of all groups compared to KO/KO by Mantel-Cox.

(I) Body weights over time of KI/KI, WT/KI and WT/WT mice.

(J) Body weights over time of KI/KI mice born from KI/KI or WT/KI dams.

(K) Organ histology (heart, upper; lung, middle; liver, lower panels) showing hematoxylin and eosin staining of representative fields of tissue sections from WT/WT (left), KI/KI (middle), KO/KO (right) mice (n ≥ 5 mice). Bar = 30 μm.

(L) Scatter plots of disease scores from mice KO/KO (n=6), WT/WT (n=6), WT/KI (n=5), KI/KI (n=6) mice, represented by filled circles, open circles, open squares, or red filled triangles respectively. Shown is mean, s.e.m.. ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test, ****p<0.0001.

(M) Anti-mature TGF-β1 immunoblot using equal amounts of plasma, or organ lysates (kidney, liver, lung, or spleen), under reducing conditions, from WT/WT, KO/KO or KI/KI mice. + or − below indicate respective genotypes. Positions of molecular weight markers (MWM) on left. Expected positions of ~50kDa and 12.5kDa uncleaved and cleaved TGF-β1 bands on right. Below, immunoblot using anti-actin as a protein loading control.

(N) CD4+ T-cells from WT/WT or KI/KI mice cultured on BSA or immobilized αvβ8tr, as indicated below image. Mature TGF-β1 detected by immunoblotting as in M. Upper: shorter exposure; middle: longer exposure to show mature TGF-β1 in WT CD4+ T-cells. Lower panel represents same membrane stripped and reprobed with anti-actin. Shown is a representative experiment (n=3).

(O) Non-cleaved TGF-β1 is present on the surface of WT CD4+ T-cells. Activated WT mouse CD4+ T-cell surface biotinylation, capture on streptavidin agarose (SA), and detection as above. Below, membrane stripped and reprobed with anti-Na+/K+ ATPase, as a cell membrane marker. Shown is a representative experiment of 3 with similar results.

(P) Same lysates from activated CD4+T-cells from N, demonstrating (upper panel) increased αvβ8-mediated TGF-β signaling detected by anti-phospho-SMAD2/3 (pSMAD2/3). Note pSMAD2 migrates slightly slower than pSMAD3; total SMAD2/3 (middle); actin (lower). Shown is a representative experiment (n=3).

(Q) Cartoon showing generation of induced-Treg (iTreg).

(R) CD4+ T-cells in activating conditions from KI/KI compared to controls, WT/WT (or WT/KI) mice plated on BSA (± recombinant TGF-β1 as a positive control) or immobilized αvβ8 ectodomain, as indicated. CD4+ T-cells stained with anti-FoxP3 and anti-CD25 and representative quadrant scatterplots shown. FoxP3+, CD25+ Treg in the upper right quadrant.

(S) Graphs showing Treg as percentage of activated CD4+ T-cells. Shown is s.e.m. ns = not significant.

(T) Representative scatterplots of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from KI/KI, and age and littermate matched controls (WT/WT or WT/KI), as indicated, and stained as in R.

(U, V) Treg enumerated from adult mouse PBMC (n=9 WT/WT and WT/KI; n=8 KI/KI) (U); or spleen at post-natal day ~18–21, n=6 WT/WT and WT/KI; n=3 KI/KI)(V) show no decrease in Treg compared with reduced Treg percentages in KO/KO mice (Figure S2). Shown is s.e.m. ns = not significant. *p<0.05

See also Figure S2.

To validate these findings, we performed several controls. We verified tgfb1R278A/R278A mice show no evidence of mature TGF-β1 cleavage (Figure 1M, N) and found non-cleaved TGF-β1 prominently expressed in WT lysates from organs and CD4+ T-cells (Figure 1M, N) and easily detected on surfaces of WT CD4+ T-cells suggesting autocrine TGF-β1 signaling without release can also occur in WT mice (Figure 1O). We confirmed non-cleaved TGF-β1 induces sufficient TGF-β signaling (Figure 1P) to generate immunosuppressive regulatory T-cells (Tregs) in vitro (Figure 1Q–S), and in vivo (Figure 1T–V).

Taken together, our findings support the physiological relevance of autocrine TGF-β1 signaling without release of mature TGF-β.

Structures of the L-TGF-β1/GARP and αvβ8/L-TGF-β1/GARP complexes

To address mechanisms allowing TGF-β1 to bind to TGF-βRs without release, we use single particle cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM) to study complexes of L-TGF-β1/GARP (Figure 2A, B) and αvβ8/L-TGF-β1/GARP in solution. By mixing L-TGF-β1/GARP with recombinant αvβ8 ectodomain (1:1 molar ratio), we obtained anticipated proportions of 1:1 and 2:1 αvβ8:L-TGF-β1/GARP complexes as revealed by mass photometry (Figure S3A) and single particle cryo-EM (Figures 2C–G, S3). Using a cell-based TGF-β1 activation assay, we demonstrated one αvβ8 is sufficient to activate TGF-β1 from L-TGF-β1/GARP for signaling (Figure S3B). Thus, while we determined structures for both 2:1 (Figure S3E) and 1:1 αvβ8:L-TGF-β1/GARP complexes, we focused on the 1:1 complex obtaining a structure at 2.5Å resolution (Figure 2C, S3E). By further intensive classification, we isolate a small percentage of unbound L-TGF-β1/GARP (4.6% particles, at 3.4Å, Figure 2D) and αvβ8 (1.5% of particles, at 4.5Å, Figure 2E), with remaining particles of the trimeric complex in many different conformations (93.9% of total particles, resolution 2.5Å-8.3Å, Figure 2F–H). In addition, we determined a 3.0Å resolution structure of L-TGF-β1/GARP (Figure S3H) from the purified L-TGF-β1/GARP sample.

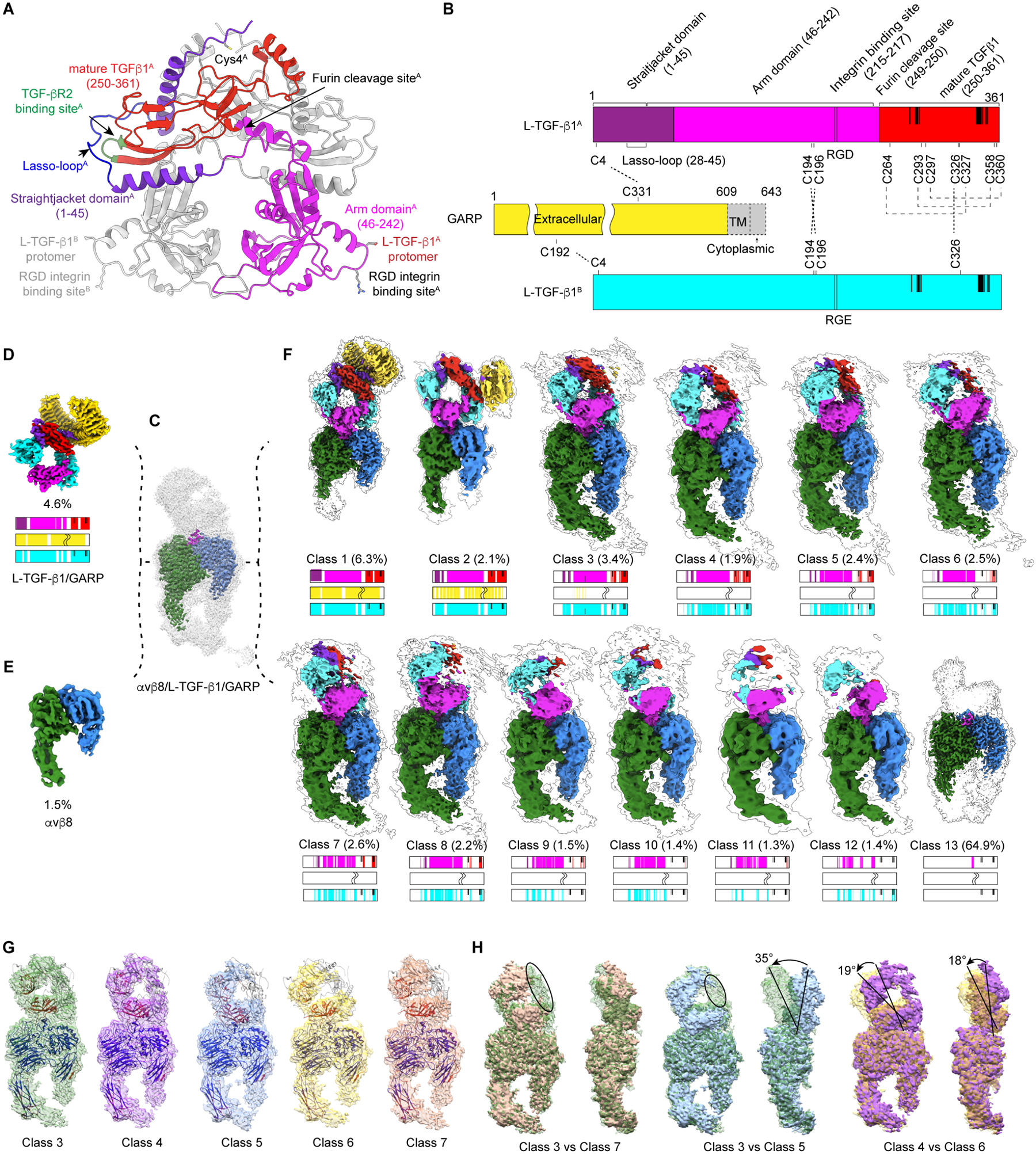

Figure 2. Structures and conformational flexibility of L-TGF-β1/GARP alone and bound with αvβ8.

(A) Atomic model of L-TGF-β1 dimer with domain in protomer A colored and marked.

(B) Schematic of L-TGF-β1/GARP constructs. Numbering starts after signal peptide. Two protomers and their respective RGD motif or RGE mutations, resolved cysteines, TGF-βR2 binding sites, and GARP transmembrane truncation indicated.

(C) Density maps of αvβ8/L-TGF-β1/GARP complex displayed with two thresholds, low in transparent grey, high in solid color. Color code: integrin αv-green, β8-blue.

(D) and (E) Density maps of L-TGF-β1/GARP (D) and αvβ8 (E) determined from classification of (C).

(F) Density maps of 13 sub-classes of αvβ8/L-TGF-β1/GARP, arranged from best to least resolved L-TGF-β1/GARP. Maps of class 3 −12 displayed at same two thresholds. Color scheme of L-TGF-β1 follows schematic in (A). Percentage below each map represents fraction of particles of the class. Bars are colored as in (A), with the unresolved regions shown in white.

(G) Five selected classes from (F) illustrating L-TGF-β1 motion relative to αvβ8. Ribbon diagram of αvβ8 and L-TGF-β1 docked within maps, arbitrarily colored.

(H) Comparison between sub-classes shown in (G) illustrate increased flexibility (class 3 vs. 7), degree and direction of motion (class 3 vs. 5, and 4 vs. 6). Structures aligned to each other using αv β-propeller domain showing L-TGF-β/GARP rocking on top of αvβ8.

See also Figure S3.

Overall, the cryo-EM structure of L-TGF-β1/GARP determined alone is largely consistent with its crystal structure (PDB: 6GFF)5, except that we connect the straitjacket domain to the contralateral arm domain on the opposite side of L-TGF-β1. In most of the structure, the resolution is sufficient to resolve sidechains for reliable atomic model building (Figures 3A, left). The local resolution of the density map and the temperature-factor (B-factor) of individual residues obtained from real space refinement of the model are consistent (Figures 3B, S3E). We further subject L-TGF-β1/GARP to 1 μs all-atom molecular dynamics simulations revealing clear correlation between the per-residue root-mean-square-fluctuation (RMSF) and B-factor (Figure S4A). RMSF measures local structural flexibility and dynamics35. Thus, local resolution or B-factor provides quantitative measurement of relative flexibility of specific regions, which clearly show half the straitjacket domain (including the lasso) is more flexible (Figure 3B, enlarged view in the upper panel) than the analogous portion of the other straitjacket within the same L-TGF-β1 (Figure 3B enlarged view in lower panel). Our results suggest, in solution, extensive interaction stabilizes the portion of the straitjacket domain in contact with GARP (Figure 3B enlarged view in the upper panel), and exposure of mature TGF-β1 may require disruption of this extensive interaction.

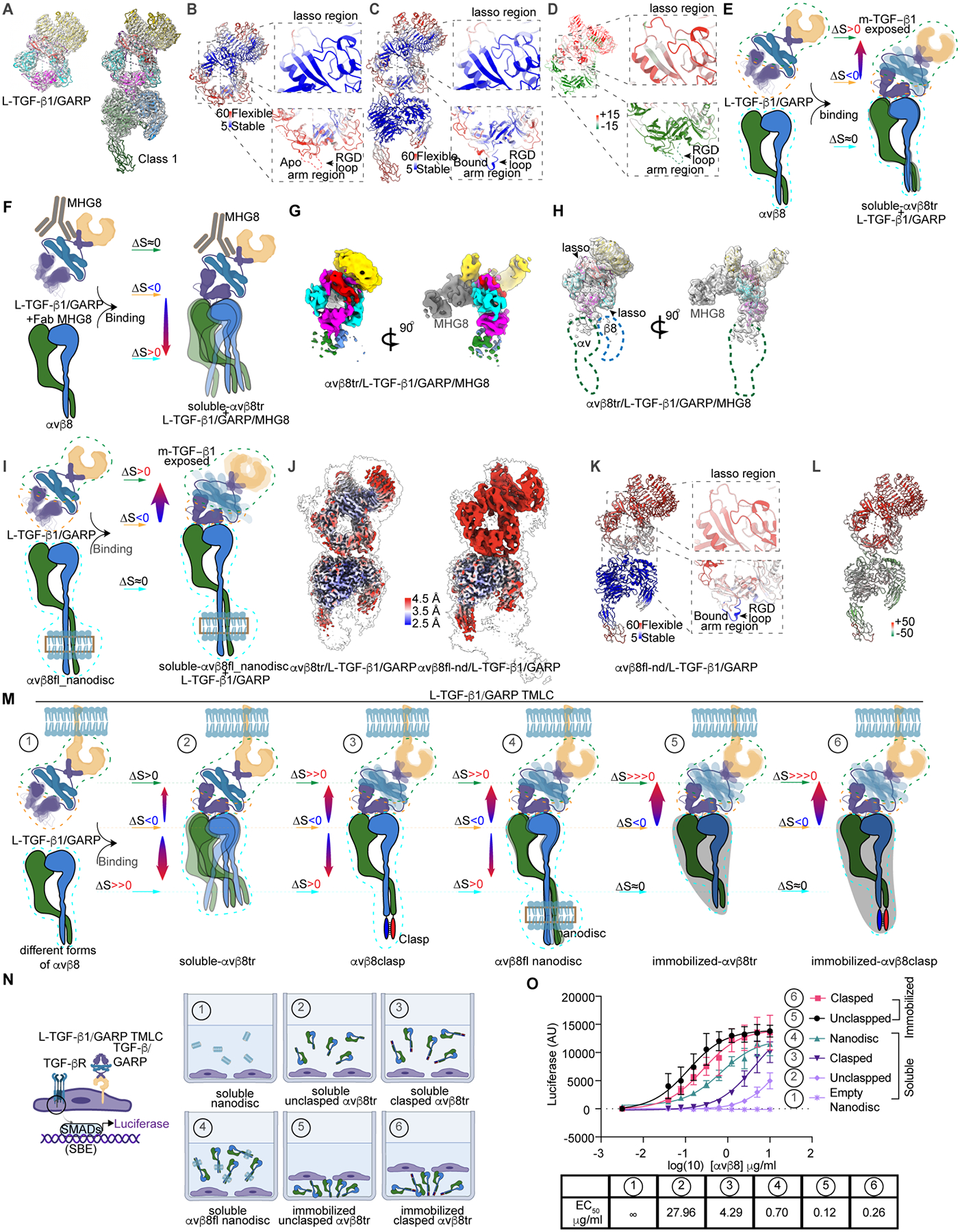

Figure 3. Spatial entropy redistribution upon L-TGF-β1/GARP binding to αvβ8.

(A) Density maps of L-TGF-β1/GARP (left) independently determined and αvβ8/L-TGF-β1/GARP (right, Class 1 from Figure 2F) docked with refined atomic model.

(B) and (C) Ribbon diagram of L-TGF-β1/GARP (B), and αvβ8/L-TGF-β1/GARP (C). Residues colored by normalized B-factors with range indicated by scale bar. Two enlarged views show lasso loop (upper) and RGD containing arm domain (lower). Dashed loop, lower panel (B), indicates unresolved RGD loop.

(D) Ribbon diagram of L-TGF-β1 colored with normalized B-factor changes before and after binding to αvβ8, decreased (green), increased (red). Arm domain binding to integrin becomes stabilized (lower dashed box with enlarged view), while straitjacket (containing the lasso, upper dashed box with enlarged view) and GARP become more flexible.

(E) Model illustrating conformational entropy redistribution upon complex formation. Different regions are circled with colored dashed lines. ΔS<0, reduction of local entropy; ΔS>0, increase of local entropy; ΔS≈0, no change in local entropy. Blurring of ribbon diagrams indicates domain flexibility observed in structures.

(F) Predicted spatial entropy redistribution upon L-TGF-β1/GARP/MHG8 binding to αvβ8. Labeling nomenclature same as (E).

(G) and (H) Two different views of αvβ8/L-TGF-β1/GARP/MHG8 map (G) and docked with atomic model (H). L-TGF-β1/GARP/MHG8 is almost entirely resolved. Only a very small part of the integrin head domain is resolved.

(I) Predicted spatial entropy redistribution upon L-TGF-β1/GARP binding to αvβ8fl-nd.

(J) Comparison of local resolutions between reconstructions of αvβ8tr and αvβ8fl-nd in complex with L-TGF-β1/GARP. Local resolutions color coded by same scale. Both densities are displayed with two density thresholds.

(K) Ribbon diagram of αvβ8fl-nd/L-TGF-β1/GARP. Residues colored by normalized B-factors with range indicated by scale bar. Enlarged views within dashed boxes show lasso loop (upper) and RGD containing arm domain (lower).

(L) Ribbon diagram of αvβ8/L-TGF-β1/GARP colored with changes of normalized B-factor between αvβ8fl-nd and αvβ8tr in complex with L-TGF-β1/GARP, decreased (green) and increased (red).

(M) Predicted entropy redistribution upon binding of soluble αvβ8tr, αvβ8fl-nd and immobilized αvβ8tr to cell membrane bound L-TGF-β1/GARP. Labeling nomenclature same as (E). Anchoring in cell membrane presumably increases stability of L-TGF-β1/GARP (panel 1). Upon binding αvβ8tr, conformational entropy is redistributed from L-TGF-β1 arm towards integrin αvβ8 (panel 2). Stabilization of αvβ8tr via clasped and nanodisc reconstitution of αvβ8fl redistributes conformational entropy largely towards straitjacket domain (panel 3 and 4). Immobilizing αvβ8tr drives entropy redistribution almost entirely towards the straitjacket, inducing sufficient flexibility for efficient TGF-β activation (panel 5 and 6).

(N) Schematics showing design of TMLC reporter cell assays of TGF-β activation without αvβ8 (1), soluble αvβ8tr without (2) or with C-terminal constraint (3), soluble αvβ8fl-nd (panel 4), or globally stabilized immobilized αvβ8tr (5), or clasped αvβ8tr (6).

(O) Activation of TGF-β by soluble and immobilized αvβ8tr (clasped and unclasped), αvβ8fl-nd and immobilized αvβ8tr using the assay configuration and numbering as in (N).

See also Figure S4.

Structural dynamics and induced flexibility of αvβ8/L-TGF-β1/GARP

Based on structures of L -TGF-β1/GARP alone and in complex with αvβ8, we hypothesized that integrin binding to L-TGF-β1/GARP further induces flexibility of GARP, L-TGF-β1 or both, leading to destabilization of the L-TGF-β1/GARP interface and lasso loops. In all snapshots that reflect motion and flexibility of GARP/L-TGF-β1 relative to αvβ8 (Figures 2F–2H and S3C–E), the domain close to the RGD binding loop is always resolved but density of the remaining part of L-TGF-β1/GARP is progressively weaker (Figures 2F). Despite only being resolved in two snapshots (Figures 2F class 1 and 2), GARP is present in all L-TGF-β1 particles, since a disulfide bond forms between GARP and each L-TGF-β1 monomer9. Extensive focused classification and alignment, together with 3D variability analysis (3DVA), reveal rocking motions of L-TGF-β1/GARP relative to αvβ8 (Figures 2G and 2H, S3F and S3G, and movie S2). Beyond rocking, we observe progressive loss of density from GARP to the straitjacket domain as range of motions increase (Figures 2G and 2H, S4B). Visualizing both rocking and progressive changes of local resolution in GARP and the straitjacket rules out the possibility that loss of density is caused by particle misalignment rather than increased flexibility. Thus, we conclude that the disappearance of GARP in the reconstructions is caused by the increased flexibility of the straitjacket domain.

In one snapshot (class 1 in Figures 2F and 3A, right) where GARP is well resolved, which contains only 6.3% of classified particles, the lasso loop of the straitjacket domain interacting with GARP becomes more flexible after binding to αvβ8, as measured from both local resolution and change of normalized B-factor based on a common reference, while local resolutions of remaining portions of L-TGF-β1/GARP are comparable in structures of αvβ8/L-TGF-β1/GARP and L-TGF-β1/GARP (Figures 3B, 3C, S3). As revealed in this best resolved structure of the trimeric complex, the arm domain of L-TGF-β becomes more stable upon binding to αvβ8, indicated by a reduction of ~15Å2 in B-factor from L-TGF-β/GARP alone, but the straitjacket domain, including lasso loop and the interface of GARP with mature TGF-β, becomes more flexible, with a ~15Å2 increase in B-factor (Figure 3D). Consequentially, destabilization of the TGF-β/GARP interface leads to progressive disappearance of L-TGF-β/GARP in the reconstructions, also reflected as progressive increase of B-factor (Figure 2F, class 3 to 8, S4C–D). Thus, binding to αvβ8 not only stabilizes the RGD loop and part of the arm domain that binds to the integrin, but also allosterically induces more flexibility in distal regions of the L-TGF-β1 ring, particularly the lasso loop and straitjacket. These findings suggest that such induced flexibility activates TGF-β1 (Figures 3D–E).

Spatial conformational entropy redistribution drives αvβ8 mediated L-TGF-β activation

What drives the allosteric activation of TGF-β1? The changes between L-TGF-β1/GARP and αvβ8/L-TGF-β1/GARP are not consistent with a “classic allostery” model conceptualized as a “domino effect” of conformational changes between stable structural endpoints36. In the best resolved structures (Figure 3A, class 1), we observed minimal changes of L-TGF-β1 in its overall conformation after binding to integrin (GARP: RMSD 1.3Å, 3950 atom pairs; L-TGF-β1 non-integrin binding subunit A: RMSD 1.9Å, 2496 atom pairs; L-TGF-β1 integrin binding subunit B: RMSD 2.0Å, 2398 atom pairs). Rather, there are obvious changes in local resolution of reconstructed maps, and per residue B-factor in refined structures (Figure 3A–D). Indeed, conformational flexibility instead of a series of discrete conformational changes is thought to drive dynamic allostery37,38,39,40.

Examining allostery through a thermodynamic lens allows connecting ‘classic’ and ‘dynamic’ allostery, where any change to the protein impacts free energy through both entropy and enthalpy. It is hypothesized that dynamic allostery influences free energy, predominantly via entropic contributions37,41. Based on the Boltzmann equation, S=kBln(W), where S is entropy, kB is Boltzmann’s constant and W represents the number of microstates42, higher conformational dynamics equal higher conformational entropy. It has also been observed that, upon binding small molecules, peptides or DNA, proteins tend to redistribute their conformational entropy, i.e. reduce conformational entropy around the binding site and consequentially increase conformational entropy in a distal region39,40,43,44. As proposed previously45,46, spatial redistribution of conformational entropy explains dynamic allostery. Applying this concept to explain dynamic allosteric activation of L-TGF-β1, our results lead to a hypothesis whereby, upon binding to αvβ8, conformational entropy in L-TGF-β/GARP is redistributed from the αvβ8 binding site to the L-TGF-β straitjacket domain (Figure 3E), allosterically exposing mature TGF-β to TGF-βR, leading to signaling.

We designed additional experiments to test this dynamic allostery hypothesis. First, we tested whether stabilizing the L-TGF-β/GARP interface in αvβ8/L-TGF-β/GARP would change the direction of spatial conformational entropy redistribution towards αvβ8. Using the inhibitory Fab MHG8, which binds to and stabilizes the L-TGF-β1/GARP interface9, we determine αvβ8/L-TGF-β1/GARP/MHG8 structure. Indeed, we find the L-TGF-β1 straitjacket, including the LAP ring and integrin binding site is well-resolved but most of αvβ8, including the head domain, is unresolved confirming redistribution of conformational entropy towards the integrin (Figures 3F–H and S4E).

Following this experiment, we further tested if the direction of spatial conformational entropy redistribution can be altered by stabilizing flexible regions. We determined a cryo-EM reconstruction of L-TGF-β1/GARP in complex with full length αvβ8 (αvβ8fl) reconstituted into lipid nanodisc (αvβ8fl-nd) constraining its otherwise flexible lower legs (Figures 3I, S4F, G). Compared with class 1 of truncated αvβ8 ectodomain (αvβ8tr) bound with L-TGF-β1/GARP, this reconstruction has better resolved αvβ8 leg, but local resolution of L-TGF-β1/GARP is worse with higher B-factor (Figure 3J–L, and S4G). Together, our results suggest conformationally flexible regions in αvβ8/L-TGF-β1/GARP serve as entropic reservoirs that can be regulated or manipulated to alter direction of entropy redistribution.

To further test this directionality of conformational entropy redistribution hypothesis, we constrained L-TGF-β1/GARP into a physiologically relevant membrane and allowed it to bind αvβ8 with various amounts of constraint, ranging from none to global stabilization (Figure 3M). In this system, L-TGF-β1/GARP is expressed in the cell membrane of a transformed mink lung epithelial TGF-β responsive reporter cell (TMLC)47 (Figure 3N), and allowed to bind with empty nanodisc as a control (Figure 3N, panel 1), αvβ8tr without constraint (2), C-terminally clasped αvβ8tr (3), αvβ8fl-nd (4), unclasped αvβ8tr globally stabilized by immobilization (5), or C-terminally clasped αvβ8tr globally stabilized by immobilization (6). For αvβ8tr, we predict that the membrane constraint imposed on L-TGF-β1/GARP directs entropy towards αvβ8 leading to inefficient TGF-β1 activation (Figure 3M). Such constraint would be overcome by increasing the constraint imposed on αvβ8, leading to increasing the efficiency of TGF-β1 activation (Figure 3M).

Indeed, with different forms of αvβ8 showing similar binding to L-TGF-β1/GARP (Figure S4H), soluble αvβ8tr without constraint does not efficiently induce TGF-β signaling (Figure 3O). In comparison, soluble C-terminally clasped αvβ8tr, or αvβ8fl-nd more efficiently activates TGF-β signaling (Figure 3O). Global immobilized C-terminally clasped or unclasped αvβ8tr has the highest activation efficiency (Figure 3O). In this assay configuration there is no mechanical force applied to αvβ8 from the actin cytoskeleton. Thus, the mechanism of αvβ8-dependent TGF-β activation favors dynamic allostery. These experiments support the hypothesis that conformational entropy redistribution is not only sufficient but is the primary mechanism driving αvβ8 mediated L-TGF-β activation.

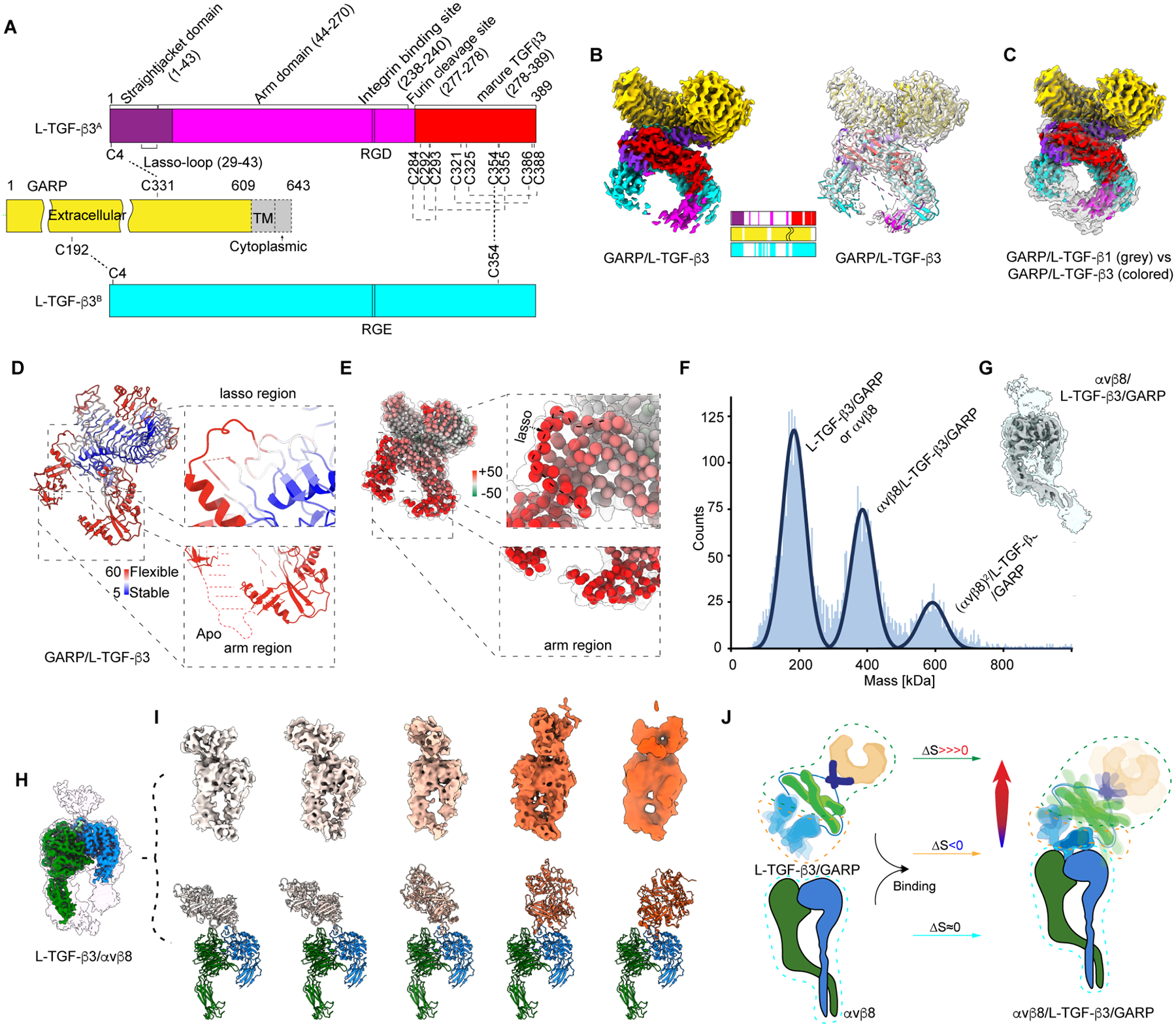

Intrinsic and induced flexibility of L-TGF-β3 and L-TGF-β3/GARP

L-TGF-β3 presented by GARP is essential during development and may also play a role in immunosuppressive immunity in post-natal life48–51. Therefore, we next study the structure and αvβ8 mediated activation of L-TGF-β3 alone and presented by GARP.

Using a similar strategy as for L-TGF-β1, we purified recombinant L-TGF-β3 and the L-TGF-β3/GARP complex (Figure 4A). Single particle cryo-EM studies provided structures of L-TGF-β3/GARP (2.9Å, Figure 4B and S5A), comparable with that of L-TGF-β1/GARP (3.0Å). The portion of the straitjacket in contact with GARP almost identical in both structures (Figures 4C, S5B–D). However, L-TGF-β3 is significantly more flexible in all other regions by B-factor comparison to L-TGF-β1, particularly the arm, which contains the integrin binding site, and the portion of the straitjacket domain, including the lasso loop, that cradles the tip of mature TGF-β containing the receptor binding domain (Figure 4D and E). Such increased intrinsic flexibility suggests that L-TGF-β3 is less constrained and contains higher basal entropy than L-TGF-β1. We hypothesize that increased basal entropy facilitates exposing mature TGF-β3 to TGF-βRs even without binding to αvβ8. After integrin binding, further entropic perturbation would lead to release of mature TGF-β3 from its latent complex.

Figure 4. Intrinsic flexibility of L-TGF-β3/GARP leads to high basal activation of TGF-β3.

(A) Schematic diagram of L-TGF-β3/GARP constructs, with all domains annotated and colored as in Figure 2A.

(B) Left: Density map of L-TGF-β3/GARP with domains colored as in (A). Bars are colored following convention in (A), with the exception that unresolved regions are shown in white. Right: The same map (transparent) with ribbon diagram of L-TGF-β3/GARP displayed within.

(C) Comparison of maps of L-TGF-β1/GARP (transparent grey) and L-TGF-β3/GARP (colored solid surface) shows arm domain of L-TGF-β3/GARP is more flexible than L-TGF-β1/GARP.

(D) Ribbon diagram of L-TGF-β3 with residues colored by normalized B-factors with scale bar. Two enlarged views within dashed boxes show lasso loop (upper) and RGD containing arm domain (lower).

(E) A consensus model of L-TGF-β1/GARP and L-TGF-β3/GARP with each Cα represented by a ball and colored with difference of normalized B-factors between L-TGF-β1/GARP and L-TGF-β3/GARP. Note B-factors of entire L-TGF-β3, particularly straitjacket (upper dashed box) and arm domains (lower dashed box), are much higher (~50Å2) than L-TGF-β1/GARP, indicating L-TGF-β3 is more flexible than L-TGF-β1 presented by GARP.

(F) Mass photometry histogram: Peaks correspond to L-TGF-β3/GARP or αvβ8 alone (~190kd), L-TGF-β3/GARP with one (~390kd), or two αvβ8 integrins (~590kd).

(G) Density map of L-TGF-β3/GARP bound with one αvβ8 at two thresholds. Disappearance of major part of L-TGF-β3/GARP indicates extensive flexibility upon binding to αvβ8.

(H) Density map reconstructed from all particles of L-TGF-β3 bound with one αvβ8. Map displayed at two thresholds.

(I) Upper row: 3D classification of all particles in (H) show flexibility of L-TGF-β3 bound with αvβ8. Bottom row: fitted atomic models of αvβ8 and L-TGF-β3 into corresponding maps shown in upper row.

(J) Cartoon of mechanistic model of intrinsic (left) versus αvβ8-induced flexibility of L-TGFβ3/GARP (right).

See also Figure S5.

To test this hypothesis, we determined structures of αvβ8/L-TGF-β3 (2.7Å) and αvβ8/L-TGF-β3/GARP (~ 4.9–7.2Å) using L-TGF-β3 constructs where the furin cleavage site (R277A) was mutated to ensure mature TGF-β3 remained associated with the latent complex (Figure S5E–F). For image processing, we used the same procedure as applied to αvβ8/L-TGF-β1/GARP avoiding potential bias in data interpretation. Although αvβ8/L-TGF-β3/GARP is stably formed (Figure 4F) and αvβ8 density well resolved, only a small portion of L-TGF-β3 but no density of GARP is resolved (Figure 4G). To simplify structural analysis, we focused on αvβ8/L-TGF-β3 without GARP (Figures 4H, and S5F). Further classification reveals L-TGF-β3 rocks over the top of αvβ8 (Figure 4I) in a much larger range than L-TGF-β1 bound to αvβ822. Indeed, in all conformational snapshots, the L-TGF-β3 straitjacket domains, including mature TGF-β3 peptides, are not resolved (Figures 4H and 4I). Overall, our structural studies of αvβ8/L-TGF-β3 and αvβ8/L-TGF-β3/GARP reveal similar but more dramatic redistribution of conformational entropy as seen in the αvβ8/L-TGF-β1/GARP (Figures 2F class 1), since we could not isolate any subclass with either GARP or complete L-TGF-β3 (Figure S5E–F). Thus, we conclude that intrinsic flexibility of L-TGF-β3 is further enhanced upon αvβ8 binding by a similar conformational entropy redistribution mechanism as seen with L-TGF-β1/GARP (Figure 4J).

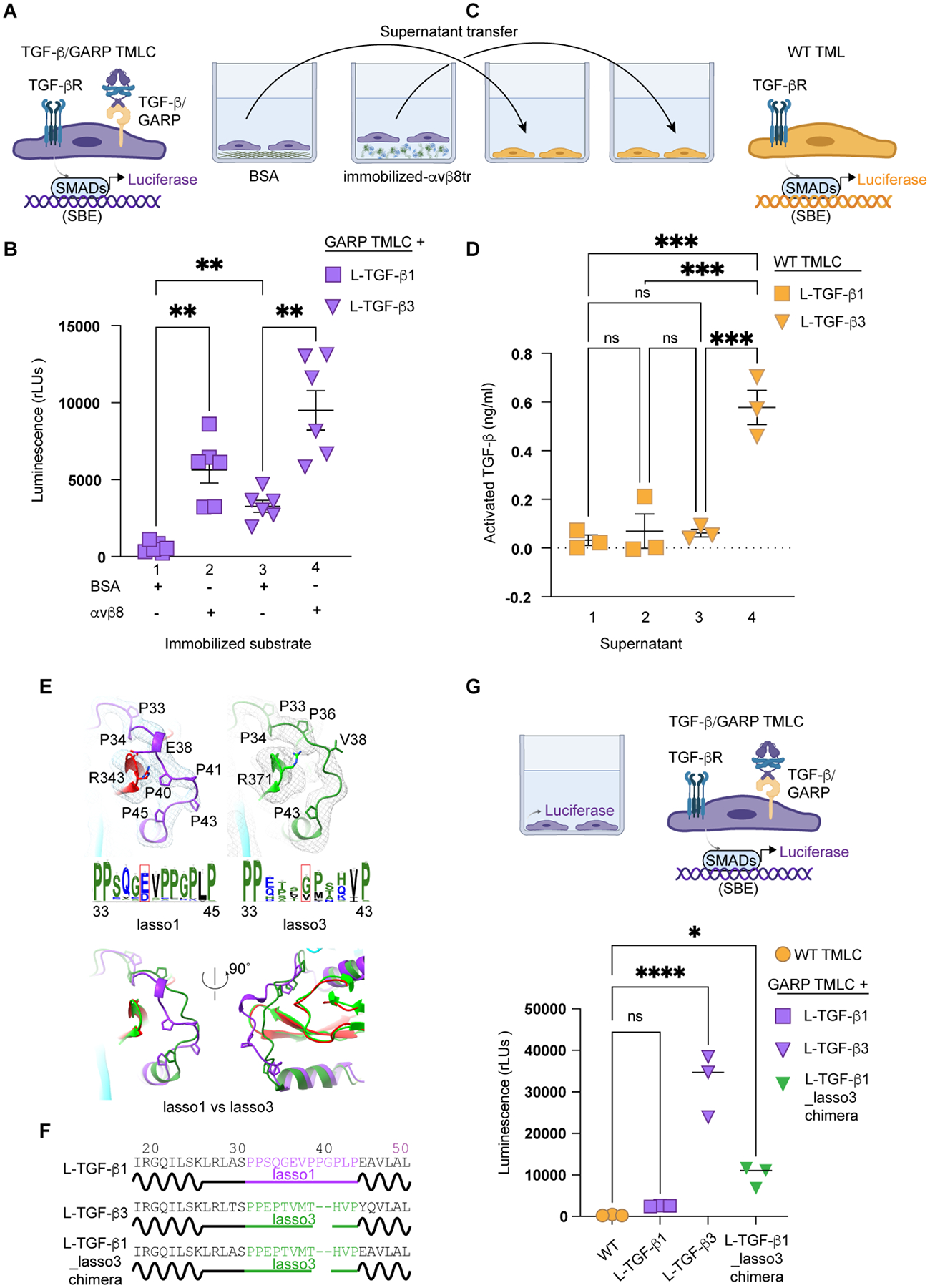

This presents a hypothesis that there is a threshold for flexibility of the straitjacket/lasso to allow mature TGF-β to be exposed to its receptors without being released. If so, increased intrinsic flexibility of L-TGF-β3 presented by GARP allows mature TGF-β3 to be exposed to its receptors, allowing basal activation even without integrin binding. To test this, we expressed L-TGF-β3/GARP and measured TGF-β activation using TMLC reporter cells, which, indeed, has significantly higher detectable basal TGF-β activity than that of L-TGF-β1/GARP with no basal activity (Figure 5A–B, S6). If there is similarly a threshold for flexibility of the straitjacket/lasso allowing mature TGF-β to be released, higher induced flexibility of L-TGF-β3 upon αvβ8 binding could be sufficient to cause release of mature TGF-β3 (Figure 5C). Indeed, analysis of supernatant from L-TGF-β3/GARP TMLC cells cultured on immobilized αvβ8 contained significant amounts of released TGF-β as opposed to supernatant from L-TGF-β1/GARP TMLC cells which did not (Figure 5C–D).

Figure 5. αvβ8 binding to L-TGF-β3 is sufficient to release mature TGF-β3.

(A) Cartoon of TGF-β activation assay, with TMLC cells transfected and sorted to express equivalent levels of L-TGF-β1/GARP or L-TGF-β3/GARP on cell surfaces, cultured on either BSA or αvβ8 coated wells.

(B) TMLC cells expressing either L-TGF-β1/GARP (purple squares) or L-TGF-β3/GARP (purple inverted triangles) were cultured overnight on the indicated substrates and luciferase activity detected and reported as luminescence in relative light units (RLU). **p<0.01 by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-test.

(C) Cartoon of TGF-β activation assay showing supernatants (A) (L-TGF-β1/GARP (yellow squares) or L-TGF-β3/GARP (yellow inverted triangles)) applied to wild-type (WT) TMLC cells detecting released TGF-β.

(D) Following overnight culture in format shown in (C) luciferase activity was detected. Results (C, D) shown as active TGF-β (ng/ml). ***p<0.001 by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-test.

(E) Upper panel: Ribbon models and filtered densities for L-TGF-β1 and L-TGF-β3 lasso-loops. Proline residues of lasso loops, used as landmarks, indicated. Middle panel: Sequence position and species conservation (larger fonts indicate higher conservation) below ribbon models. Lower panel: Overlays of L-TGF-β1 and L-TGF-β3 models in two views illustrating lasso3 does not cover the TGF-βR2 binding site of mature TGF-β as effectively as lasso1.

(F) Sequence alignment showing lasso region of L-TGF-β1, -β3, and chimeric L-TGF-β1 with swapped lasso of L-TGF-β3.

(G) Lasso3 domain destabilizes L-TGF-β1/GARP. Upper: Cartoon. Lower: TMLC stably expressing GARP transfected with constructs encoding L-TGF-β1 (purple square), L-TGF-β3 (purple inverted triangles), or L-TGF-β1 with swapped lasso3 (TGF-β1_lasso3 chimera, green inverted triangles) and sorted for equivalent expression. WT TMLC (yellow circles) or L-TGF-β/GARP expressing cell lines were cultured overnight and luciferase activity reported as luminescence (RLU). *p<0.05, ****p<0.0001 by one-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparison test.

See also Figure S6.

Why mature TGF-β3 as opposed to TGF-β1 is released from its latent complex could be explained by relative differences in intrinsic flexibility of the lasso loop, a critical determinant of latency in all TGF-β superfamily members5,52. A detailed comparison of sequence and structure reveals that the lasso loop of L-TGF-β3 (lasso3) is not only shorter than L-TGF-β1 (lasso1) but also less conserved in key residues interacting with mature TGF-β53 (Figure 5E). We thus hypothesize that lasso3 has evolved to be more flexible providing less coverage to mature TGF-β3 from exposure to its receptor allowing higher basal activity of L-TGF-β3. To test this hypothesis, we swapped the TGF-β3 lasso into TGF-β1 (L-TGF-β1_lasso3) (Figure 5F) and observed significantly increased basal activation of TGF-β1 although not to the level of wild type L-TGF-β3 (Figure 5G and S6). Together, we conclude that levels of conformational entropy of the arm, straitjacket and lasso domains, as well as the structure of lasso loop, are key to maintaining latency, exposure, or release of mature TGF-β.

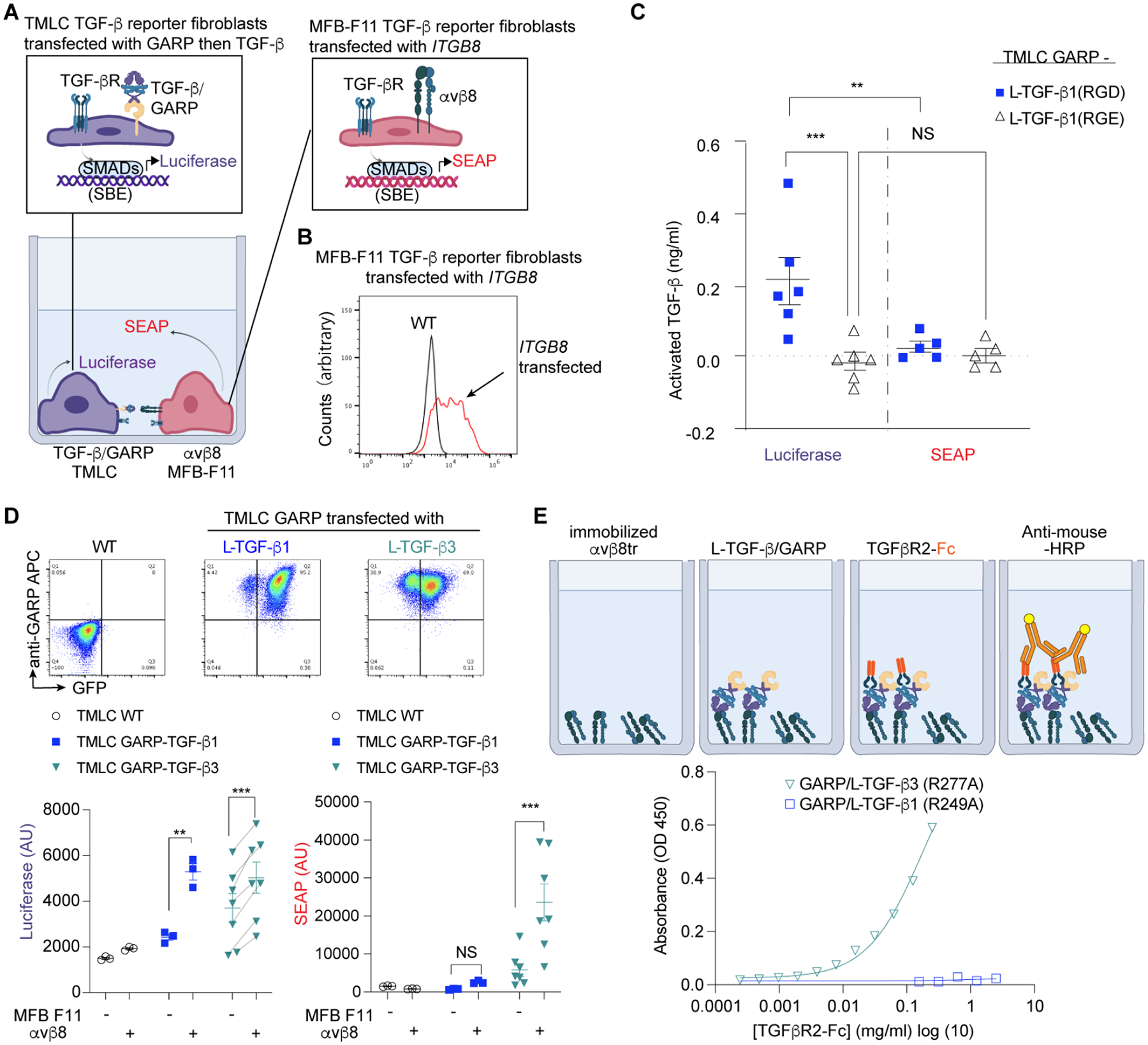

Functional consequences of TGF-β release from αvβ8 mediated L-TGF-β activation.

Under the physiological conditions where αvβ8-mediated TGF-β activation occurs in vivo, αvβ8 is presented by one cell, but L-TGF-β is presented on the cell surface of a contacting cell27. In this scenario, αvβ8 mediated TGF-β activation could result in bidirectional signaling to both cells if TGF-β was released (paracrine), or only in unidirectional signaling on the immune cell presenting TGF-β cell if not released (autocrine). To test whether such αvβ8-mediated directional TGF-β activation occurs, we devised an in vitro co-culture model system where the integrin αvβ8 is expressed by TGF-β1 null embryonic fibroblasts (MFB-F11) stably expressing a TGF-β responsive secreted alkaline phosphatase (SEAP) reporter construct54, and TGF-β is expressed on the surface of TMLC cells (Figure 6A–C). The MFB-F11 reporter cells are highly sensitive to exogenous TGF-β, indicating possession of the full complement of TGF-β receptors and downstream signaling apparatuses54. When co-cultured with L-TGF-β1/GARP expressing TMLC TGF-β reporter cells, SEAP in cell supernatants reports TGF-β signaling from αvβ8 expressing cells while luciferase measured from cell lysates reports TGF-β signaling from L-TGF-β1/GARP TMLC cells (Figure 6A–C). Since MFB-F11 cells are TGF-β deficient, the only cellular source of TGF-β1 in system is from L-TGF-β1/GARP expressing TMLC TGF-β reporter cells.

Figure 6. Intrinsic and integrin-induced entropy of L-TGF-β determines signaling directionality.

(A) Carton of design of dual TGF-β reporter system, TMLC (purple) and MFB-F11 (red), are co-cultured (left). Shown are stably expressed reporter constructs with SMAD-binding elements (SBE) driving indicated reporter proteins, luciferase or secreted alkaline phosphatase (SEAP).

(B) MFB-F11 reporter cells stably transduced with an integrin β8 (ITGB8) expression construct sorted for high αvβ8 expression, using an anti-β8 antibody. Histogram demonstrates expression of αvβ8 only seen in ITGB8 transfected (red curve), not non-transfected (NT) cells (black curve).

(C) Mixing αvβ8 expressing MFB-F11 cells with L-TGF-β1/GARP presenting TMLC cells is required and sufficient to activate TGF-β signaling pathway on L-TGF-β1/GARP expressing cells but not αvβ8 expressing cells. L-TGF-β1(RGD)/GARP TMLC (filled squares), L-TGF-β1(RGE)/GARP TMLC (open triangles, characterized as Figure S3B). Results (vertical axis) normalized against standard TGF-β activation curve. **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 by one-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparison test.

(D) Upper: Transfection of TMLC cells stably expressing GARP and co-transfected with either wild-type L-TGF-β1 or L-TGF-β3 IRES GFP plasmids. Surface expression of L-TGF-β1 and L-TGF-β3 are equivalent. Lower: Co-culture of wild type MFB-F11 (−), or αvβ8 transfected (+) MFB-F11 cells (indicated below graph) with wild type TMLC (black circles), or TMLC expressing L-TGF-β1/GARP (blue filled squares) or L-TGF-β3/GARP (green triangles). Left: TMLC cells have significant basal levels of active TGF-β3 even when cultured without αvβ8-expressing MFB-F11, but further increased by coculture with αvβ8-expressing MFB-F11 cells. Right: Increased SEAP only seen when TMLC L-TGF-β3/GARP cells are cocultured with αvβ8-expressing MFB-F11. Results shown as arbitrary light units (AU). **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 by one-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparison test, with the exception that results for L-TGF-β3/GARP cells on wild type MFB-F11 or MFB-F11 αvβ8 expressing cells are shown as a paired t-test.

(E) TGF-βR2 binds more efficiently to αvβ8 bound L-TGF-β3/GARP compared to L-TGF-β1/GARP. Upper: cartoon showing sequential immobilization of αvβ8 ectodomain, binding of L-TGF-β1 or -β3/GARP complexes, TGF-βR2-Fc (mouse-Fc), and anti-mouse-HRP. Lower: representative experiment (n=3) shown with varying concentrations of TGF-βR2-Fc, signal reported as OD450.

Co-culture of αvβ8 expressing MFB-F11 reporter cells with L-TGF-β1/GARP expressing TMLC reporter cells results in autocrine signaling since only luciferase is detected (Figure 6A–C). Such exclusivity of autocrine signaling can be attributed to insufficient flexibility of straitjacket and lasso loops of L-TGF-β1 allowing mature TGF-β1 to be released but sufficient to be exposed within the latent ring to bind to TGF-βR2 after αvβ8 binding. The next question is whether directionality of L-TGF-β3 activation by αvβ8 is different than L-TGF-β1, since mature TGF-β3 is released upon αvβ8 binding (Figure 5C, D). Indeed, both autocrine and paracrine TGF-β3 signaling are observed since luciferase and SEAP are detected (Figure 6D). We hypothesize that within L-TGF-β, mature TGF-β3 compared to TGF-β1 would be more accessible to TGF-βR2, the first receptor binding mature TGF-β to initiate signaling55.

To test whether TGF-βR2 binds mature TGF-β when exposed within L-TGF-β complexes, we performed TGF-βR2 binding assays to immobilized αvβ8 bound L-TGF-β3 or L-TGF-β1/GARP complexes. In these systems, the furin cleavage site between the mature TGF-β and LAP are mutated at analogous positions as in tgfb1R278A/R278A mice, and thus mature L-TGF-β cannot be released. Consistent with our structural analysis and TGF-β activation assays, we observed more robust complex formation between TGF-βR2 and L-TGF-β3/GARP than to L-TGF-β1/GARP when bound to immobilized αvβ8 (Figure 6E).

Discussion:

Physiological role of TGF-β1 activation without release

TGF-β1 plays major roles in mammalian biology from embryo implantation through the entire lifespan. For all roles, the dogma is TGF-β release is required for both autocrine and paracrine function3. This view is reinforced by numerous biochemical and structural experiments5,53,55–58, but is challenged by our previous study of αvβ8/L-TGF-β1 predicting mature TGF-β1 can be sufficiently exposed to bind to its receptors within L-TGF-β1 without release22.

Here, we provide definitive evidence that mature TGF-β without release supports autocrine signaling. In mice mature TGF-β1 covalently bound to LAP induces sufficient signaling to support immune function, since founders have so far survived 7 months without early immune lethality associated with global TGF-β1 deficiency9,59–61. Our ability to generate live births from homozygous tgfb1R278A/R278A intercrosses in the complete absence of wild type maternal TGF-β1 from conception to adulthood, provides definitive evidence that paracrine release of mature TGF-β1 is not essential either for development or for early immune function.

Our results differ from previous reports where mice with furin conditionally deleted in T-cells develop delayed organ inflammation similar to mice with conditional deletion of TGF-β1 in T-cells20. However, furin potentially cleaves hundreds of substrates other than TGF-β162, and likely has effects independent of TGF-β1. Mice with tgfb1 conditionally deleted in T-cells lack autocrine TGF-β1 signaling by T-cells, whereas autocrine TGF-β1 signaling is preserved in tgfb1R278A/R278A mice. Confirmation that autocrine TGF-β1 signaling without release is sufficient to prevent autoimmunity not only validate our structure-based approach to study the L-TGF-β activation mechanism but demonstrate the power of cryo-EM to reveal structural mechanisms of flexible proteins that would otherwise have been unanticipated.

L-TGF-β activation driven by conformational entropy redistribution

The concept of conformational entropy redistribution, where entropy reduces around the ligand binding site and increases at distant sites is derived from conformational ensembles quantitatively characterized from structures obtained by X-ray crystallography or NMR spectroscopy of relatively small proteins44,46. With single particle cryo-EM, protein conformational dynamics correlate with local resolutions of reconstructed structures, allowing exploration of conformational entropy redistribution in much larger and complex systems. Redistribution of conformational entropy also explains dynamic allosteric communication from ligand binding sites to distant sites without involving propagation of discrete stable conformational changes38,46.

Here, we used cryo-EM to examine conformational entropy redistribution in large and multi-component protein complex, αvβ8/L-TGF-β/GARP, where all components have been shown to be highly flexible in our previous22,28 and current studies. By characterizing changes of conformational flexibility of different regions of L-TGF-β/GARP induced by integrin αvβ8 binding, we show conformational entropy redistribution is the underlying dynamic allostery mechanism of αvβ8 mediated L-TGF-β activation.

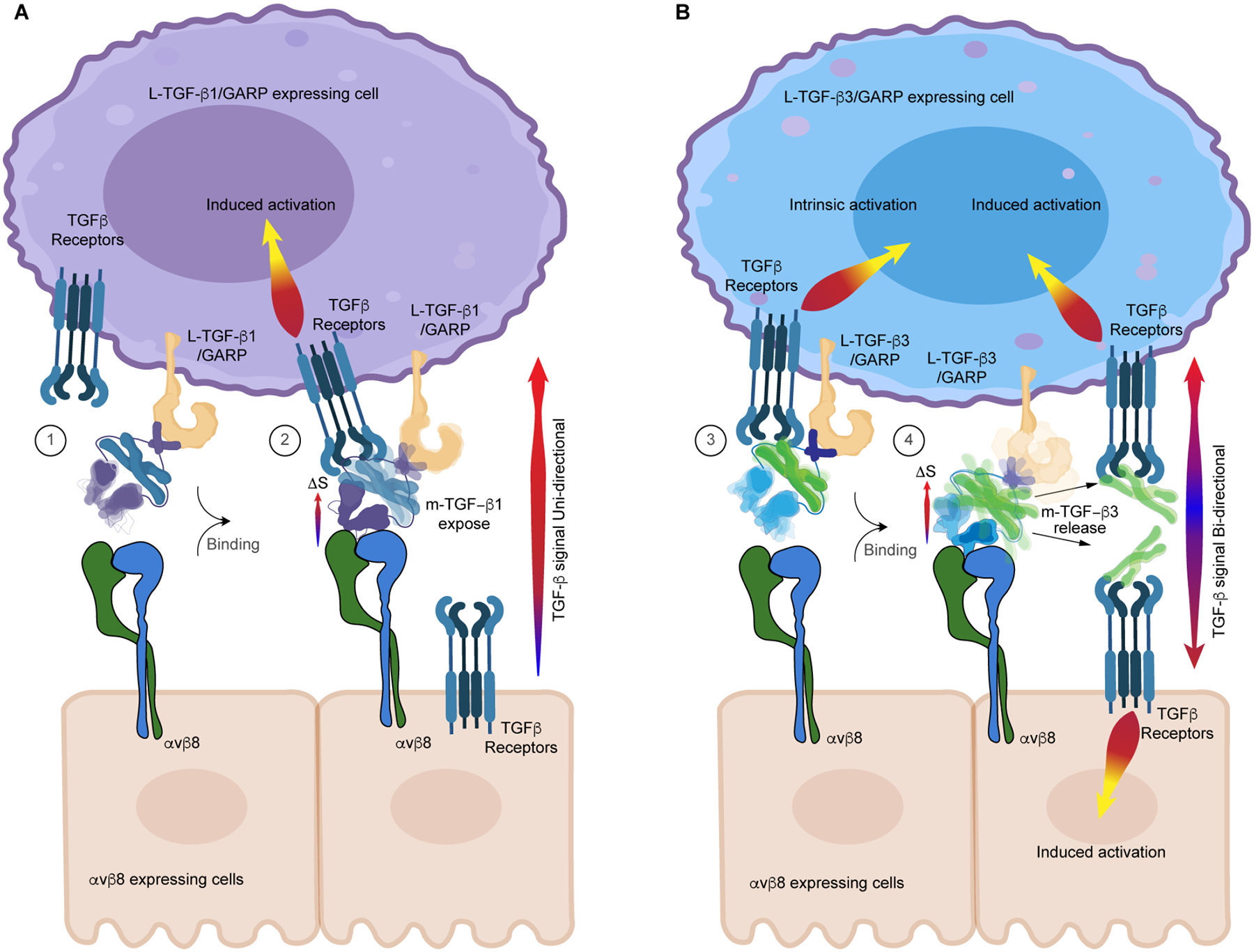

Specifically, we demonstrate that intrinsic flexibility, the basal conformational entropy of L-TGF-β complexes, controls TGF-β latency. In the case of the fully latent L-TGF-β1, the straitjacket and lasso loops are relatively stable (Figure 7A, panel 1), as opposed to the partial latent L-TGF-β3, where the same domains are flexible (Figure 7B, 3). Binding to αvβ8 stabilizes the flexible RGD loop on the arm domain of both L-TGF-β1 and -β3 and reduces local conformational entropy. Spatial redistribution of this entropy towards the straitjacket enhances flexibility of the respective lasso loops. For L-TGF-β1, lower basal conformational entropy results in less entropy redistribution towards the lasso domain, insufficient to release mature TGF-β but sufficient to expose it to its receptor (Figure 7A, 2). Without being released, TGF-β is restricted to autocrine signaling. In contrast, because L-TGF-β3 has higher basal conformational entropy, αvβ8 binding results in more entropy redistribution towards the lasso domain resulting in L-TGF-β3 passing a flexibility threshold sufficient for releasing mature TGF-β3 (Figure 7B, 4). Released TGF-β3 is capable of both autocrine and paracrine signaling to either αvβ8 or L-TGF-β3/GARP presenting cells.

Figure 7. Dynamic entropy-based allosteric model of TGF-β activation.

(A) Cartoon of intrinsic and integrin-induced TGF-β1 activation. 1) L-TGF-β1/GARP has relatively low basal entropy in straitjacket/lasso, insufficient to trigger significant signaling. 2) Binding αvβ8 stabilizes arm domain but redistributes sufficient entropy to expose mature TGF-β1 to TGF-βRs to trigger signaling.

(B) Cartoon of intrinsic and integrin-induced TGF-β3 activation. 3) TGF-β3/GARP has relatively high levels of basal entropy in straitjacket/lasso sufficient to expose mature TGF-β3 to TGF-βRs allowing basal L-TGF-β3 constitutive autocrine signaling. 4) Binding to αvβ8 stabilizes the arm domain redistributing entropy exposing mature TGF-β3 to TGF-βRs, sufficient for paracrine release of mature TGF-β3 for bidirectional signaling to L-TGF-β3 presenting, and αvβ8 expressing cells.

Physiological relevance of dynamic allostery in the activation of the TGF-β3/GARP complex

TGF-β3, as opposed to TGF-β1, is required for palatogenesis13,16,63,64. Our structural and cell-based findings of αvβ8/L-TGF-β3/GARP complex are likely physiological relevant since GARP and TGF-β3 form a covalent complex9,50, GARP and TGF-β350 colocalize to critical regions involved in palatogenesis, their respective genetic deficiencies in mice and/or humans lead to cleft palate16,49,50,65, and human genetic cleft palate syndromes result from missense mutations in the furin or the RGD sequence of TGFB314,66. Interestingly, the cleft palate phenotype in itgb8 null mice is only seen in a subset of live births67,68. We speculate that the intrinsic flexibility of L-TGF-β3 and exposure of mature TGF-β3 provides sufficient basal TGF-β signaling for palatogenesis even without integrin αvβ8 binding.

Broader implication of dynamic allostery mechanism in macromolecular complexes

Our data using the multicomponent αvβ8/L-TGF-β1(-β3)/GARP model system provide evidence that redistribution of conformational entropy is a mode of allosteric regulation in a highly dynamic system. Protein dynamics are quantified as conformational entropy via the Boltzmann equation42. It has been demonstrated that protein dynamics can tune protein function without involving discrete conformational changes38. However, until very recently, examples of such dynamics were limited to side chain rotamer ensembles by X-ray crystallography or methyl or amine group dynamics of small proteins by NMR spectroscopy44. The αvβ8/L-TGF-β/GARP provides a case study of a tunable functional endpoint (i.e. activation) correlating with protein dynamics in a relatively large complex. It is likely that dynamic allostery is a widespread mechanism to tightly regulate protein function, yet underappreciated, since methodology to decipher this new dimension in macromolecular protein function is only beginning to be applied. Single particle cryo-EM is one valuable tool to directly visualize conformational dynamics in larger protein complexes. Combining it with other technologies, such as hydrogen-deuterium exchange mass spectrometry and/or molecular dynamics simulations, etc., it is reasonable to anticipate dynamic allostery driven by conformational entropy redistribution will be found to play important mechanistic roles in many biological systems.

Intrinsic conformational entropy in latency of the TGF-β superfamily

The three TGF-β isoforms are thought to be completely latent, along with a few others in the larger TGF-β superfamily (i.e. GDF8, and GDF11)5,52,69,70. The high basal activity of L-TGF-β3 was unexpected, which we attribute to the increased intrinsic entropy of straitjacket and lasso loops compared to TGF-β1. We propose the relative intrinsic entropy of the straitjacket and lasso is a general evolutionary strategy controlling the degree of latency of TGF-β superfamily members. Thus, as with L-TGF-β3, latency is clearly not absolute, but rather determined by the degree of intrinsic conformational entropy. Extending this concept to non-latent TGF-β superfamily members with available structures, all have highly flexible straitjacket and lasso loops, such as BMP9, BMP10 and ActivinA suggesting they have very high levels of intrinsic entropy allowing their growth factors to be freely exposed to receptors without requiring release (Figure S7). Overall, our data supports an alternative hypothesis where extent of latency is a continuum controlled by levels of intrinsic entropy of the straitjacket, which when sufficiently high allows receptors to bind exposed receptor binding domains of mature growth factors while still within the prodomain complex. Amongst the TGF-β superfamily, L-TGF-β1, with its relatively low entropy appears to be an exception, rather than the rule.

Therapeutic implications

The general concept of latency of TGF-β activation is binary, it is either latent or active. The binary dogmatic view has led to therapeutic approaches targeting released paracrine mature TGF-β and have efficacy and safety issues71–76. The architecture and flexibility of αvβ8/L-TGF-β/GARP suggests L-TGF-β/GARP antibody binding epitopes are highly flexible and unstable, and multiple steric clashes limit access of TGF-βR traps, or antibody inhibitors to TGF-β or TGF-βRs within the complex. Indeed, we have observed poor inhibitory activity of antibody inhibitors to TGF-β, TGF-βRs, L-TGF-β1/GARP or TGF-βR traps for αvβ8-mediated activation of TGF-β27. Thus, it is not surprising that immuno-oncology clinical trials using approaches that target paracrine released TGF-β have been disappointing due to lack of efficacy77. Our results predict antibodies stabilizing L-TGF-β might also face similar efficacy challenges in clinical trials if the activation mechanism is αvβ8-dependent9,78,79.

Mechanistic insights revealed from our study suggest why TGF-β function can be highly context dependent, given dynamic allostery determines where and when TGF-β is activated, whether it signals as an autocrine factor while remaining associated with the latent complex or is released, and ultimately whether it mediates paracrine signaling. Such a mechanism determines if TGF-β primarily directs signaling to TGF-β-presenting or integrin-expressing cells, and cells in proximity or at a distance. Thus, targeting TGF-β activation is highly complex, but such complexity offers opportunities for targeting context-dependent directional TGF-β activation, which can be achieved at multiple levels either through targeting basal entropy, entropic redistribution, or release. Importantly, entropy redistribution can be manipulated to occur in different directions, as demonstrated by our findings (Figure 3F–O). It remains to be determined how targeting entropically driven mechanisms will affect different pathologic scenarios. Overall, our results provide a structural framework for developing therapeutic approaches to inhibit context-specific functions of different TGF-βs and argue against one-size-fits-all targeting strategies.

Limitations of Study

The tgfb1R278A/R278A mouse model is early in establishment and full immune characterization is ongoing. Thus, we cannot exclude delayed effects on tissue inflammation due to lack of paracrine release of mature TGF-β1 as mice age further.

Despite providing a conceptual framework for understanding the mechanism of dynamic allostery, our current description of conformational entropy redistribution is only partially quantitative. More comprehensive quantitative descriptions of large-scale conformational entropy redistribution require major advancements of current methodologies.

STAR METHODS

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead Contact

Further information and requests for reagents may be addressed to Yifan Cheng (yifan.cheng@ucsf.edu).

Materials Availability

All new materials generated in this manuscript, including mice, antibodies, cell lines and plasmids, are available on request from the lead contact with a completed Materials Transfer Agreement.

Data and Code Availability

All cryo-EM density maps, coordinates for the atomic models and local-refined maps generated in this study have been deposited and are publicly available. Accession numbers (EMDB, PDB IDs) are listed in the key resources table.

No new code was included in this study.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Anti-mouse TGF-β1 | Abcam | ab179695 |

| Anti-human, mouse αvβ8, C6D4 | Takasaka et al., 201880 | N/A |

| Anti-human αv, 8B8 | Mu et al., 200218 | N/A |

| Anti-mouse HRP | GE Healthcare | Cat. # NA931V; RRID:AB_772210 |

| Anti-LAP-β1-biotin or APC conjugated | R&D Systems | Cat. # BAF246; RRID:AB_356332 |

| Anti-LAP-β1 | R&D Systems | Cat. # AF426; RRID:AB_354419 |

| Anti-GARP | BioLegend | Cat. # 352502 |

| Anti-human, mouse αvβ8 | This paper | C6D4F12 |

| anti-mouse-APC | Biolegend | Cat. # 405308 |

| anti-HA (clone 5E11D8) | Thermo Fisher | Cat. # A01244-100 |

| Anti-Na+/K+ ATPase | Invitrogen | Cat#MA5-32184 |

| Anti-Actin | Sigma | Cat#A2228 |

| Anti-pSMAD2/3 | Cell Signaling | Cat#8828S |

| Anti-SMAD2/3 | Cell Signaling | Cat#3102S |

| Live Dead Fixable Blue | Thermo | Cat#L23105 |

| ACK lysis buffer | Thermo | Cat#A1049201 |

| Fc receptor block (CD16/32) | BD biosciences | Cat# 553141 |

| Brilliant Staining Buffer | BD biosciences | Cat# 563794 |

| Foxp3 / Transcription Factor Staining Buffer Set | eBioscience | Cat#00-5523-00 |

| Anti-mouse CD3 | Biolegend | Cat#10020 |

| Anti-mouse CD45 (clone 30-F11) | Biolegend | Cat. # 103128 |

| Anti-mouse CD45 (clone 30-F11) | Biolegend | Cat. # 103128 |

| Anti-CD90.2 (clone 53-2.1) | BD biosciences | Cat. # 565257 |

| Anti-mouse CD19 (clone 6D5) | Biolegend | Cat. # 115566 |

| Anti-mouse TCRβ (clone H57-597) | Biolegend | Cat. # 109249 |

| Anti-mouse CD4 (clone RM4-5) | Biolegend | Cat. # 100559 |

| Anti-mouse CD8a (clone 53-6.7) | Biolegend | Cat. # 100740 |

| Anti-mouse CD25 (clone PC61) | Biolegend | Cat. # 102072 |

| Anti-mouse FoxP3 (clone MF-14) | Biolegend | Cat. # 126405 |

| CD4+ T cell isolation kit | Miltenyi | Cat#130-104-454 |

| Serum Free Medium, containing IMDM | Gibco | Cat#12440-053 |

| 1% Insulin-Transferrin-Selenium | Gibco | Cat#41400-045 |

| 2-Mercaptoethanol | Gibco | Cat#31350-010 |

| Retinoic acid | Sigma | Cat#R2625 |

| IL-2 | R&D Systems | Cat#402-ML/CF |

| Recombinant TGF-β1, human | R&D Systems | Cat#240-B |

| Anti-mouse CD25-APC | Biolegend | Cat#102012 |

| anti-mouse Foxp3-PE | Biolegend | Cat#126404 |

| RIPA buffer | Sigma | Cat#R0278 |

| Protease inhibitor cocktail | Thermo Scientific | Cat#87786 |

| Phosphatase inhibitor | Thermo Scientific | Cat#A32957 |

| BCA assay | Thermo Scientific | Cat#23228 |

| Anti-Mouse-IgG | Jackson Immunoresearch | Cat#711-035-152 |

| Anti-Rabbit-IgG | Jackson Immunoresearch | Cat#715-035-150 |

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| DH5a Chemically Competent E. coli | Thermo Fisher | Cat. # 18265017 |

| Biological samples | ||

| None | ||

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Puromycin | Sigma Aldrich | Cat. #P8833 |

| Hygromycin | Thermo Fisher | Cat. # 10687010 |

| G418 sulfate | Thermo Fisher | Cat. # 10131035 |

| HRV-3C protease | Millipore Sigma | Cat. # 71493-3 |

| Gibson Assembly Cloning Kit | NEB | Cat. # #E5510S |

| KAPA Mouse Genotyping Kit | Sigma Aldrich | KR0385_S – v3.20 |

| Protein-G Agarose | Pierce | Cat. # 20398 |

| Strep-tactin agarose | IBA | Cat. # 2-1204-001 |

| Ni-NTA agarose | Qiagen | Cat. # 30210 |

| Lipofectamine 3000 | Thermo Fisher | Cat. # L3000001 |

| rhTGF-β1 | R&D systems | Cat. # #240-B-002/CF |

| NHS-LC Biotin | Thermo | Cat#A39257 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| Luciferase Assay System | Promega | Cat. # E1500 |

| SEAP Assay System | Invitrogen | Cat. # T1017 |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| Mink: TMLC | Abe et al., 199447 | N/A |

| Mouse: MFB-F11 | Tesseur, et al., 200654 | N/A |

| Human: Expi293F | Thermo Fisher | Cat. # A14527 |

| Hamster: ExpiCHO-S | Thermo Fisher | Cat. # A29127 |

| Mouse: MFB-F11 with ITGB8 | This paper | N/A |

| Mouse: MFB-F11 with GARP and L-TGF-β1 | This paper | N/A |

| Mouse: MFB-F11 with GARP and L-TGF-β3 | This paper | N/A |

| Mouse: MFB-F11 with GARP and L-TGF-β1_lasso3 chimera | This paper | N/A |

| Mouse: MFB-F11 with GARP and L-TGF-β1(RGE) | This paper | N/A |

| Phoenix-AMPHO | ATCC | CRL-3213 |

| Experimental models: Mice | ||

| Mouse: B6(Gt(ROSA)26Sortm1(PGK1-cre)Ozg | Ozgene | MGI:5435692 |

| Mouse: 129X1/SvJ | The Jackson Laboratory | Strain #:000691 |

| Mouse: C57BL/6J-tgfb1em2Lutzy/Mmjax | The Jackson Laboratory | Strain #:000691 |

| Mouse: B6.129-tgfb1R278A/R278A | This paper | N/A |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| 5’- tgcacagtacctcatgcaca-3’ | This paper | JaxTGFB1F |

| 5’-gaacacagtgctaggcagg-3’ | This paper | mTGFB1Ex3R1 |

| 5’-ctgtcctggaactcactctgtag-3’ | This paper | TGFb1 1F |

| 5’-gtttggatgttgtggtgaagga-3’ | This paper | TGFB1 KI/cKI 4R |

| 5’-ccacatttggagaaggac-3’ | This paper | TGFb F WT only |

| 5’-catacattatacgaagttatgatctaag-3’ | This paper | TGFb F KI only |

| 5’-gacatacacacacttagagg-3’ | This paper | TGFb WT/KI rev |

| 5’-gctcagttgggctgttttggag-3’ | This paper | ROSAWT F |

| 5’-tagaacagctaaagggtagtgc-3’ | This paper | ROSAFlp F |

| 5’-atttacggcgctaaggatgactc-3’ | This paper | ROSAcre F |

| 5’-ttacacctgttcaattcccctg-3’ | This paper | ROSA R |

| 5’-ctgaaccaaggagacggaatac-3’ | This paper | tgfb1 Ex3/4 cDNA F |

| 5’-gttgtagagggcaaggaccttg-3’ | This paper | tgfb1 ex 6/7 cDNA R |

| 5’-gcaacaacgccatctatgag-3’ | This paper | tgfb1 Ex1/2 cDNA F |

| 5’-gctgatcccgttgatttccac-3’ | This paper | tgfb1 Ex4/5 cDNA R |

| 5’-caggtgtcgtgaggctagcatcg-3’ | This paper | hTGFB1 Stop F |

| 5’-gcgccactagtctcgagttatcag-3’ | This paper | hTGFB1 Stop R |

| 5’-ccctgagccaacggtgatgacccacgtccccgaggccgtgctcgc-3’ | This paper | Lasso3 SOE F |

| 5’-tggcgtagtagtcggcctc-3’ | This paper | hTGFB1 Bsu36I R |

| 5’-ccatttcaggtgtcgtgaggc-3’ | This paper | hTGFB1 F |

| 5’-gtcatcaccgttggctcaggggggctggtgagccgcagcttggacag-3’ | This paper | Lasso3 SOE R |

| 5’-ctctgatatcccaagctggctagccacc-3’ | This paper | SBPHIS F |

| 5’-cagggcactttgtcttggtgaggaccctgaaacagcacctc-3’ | This paper | SBPHIS SOE R |

| 5’-ttagaggtgctgtttcagggtcctcaccaagacaaagtgccctg-3’ | This paper | HAGARP SOE F |

| 5’-ccgctgtacaggctgttccc-3’ | This paper | HAGARP R |

| 5’-agggccgtgtggacgtgg-3’ | This paper | HAGARP Tr F |

| 5’-tctcctcgagttatcagttgatgttcttcagtccccccttc-3’ | This paper | HAGARP Tr R |

| 5’-ggggactgaagaacatcaacatgtcgtactaccatcaccatc-3’ | This paper | GARP Spy F |

| 5’-ggcttaccttcgaagggcccttagctaccactggatccagta-3’ | This paper | GARP Spy R |

| 5’-ccatgtcacacctttcagccc-3’ | This paper | TGFB3 R277A F |

| 5’-gtccaaagccgccttcttcctctg-3’ | This paper | TGFB3R277ASOER |

| 5’-cagaggaagaaggcggctttggac-3’ | This paper | TGFB3R277ASOEF |

| 5’-gtgttgtacagtcccagcacc-3’ | This paper | TGFB3 R277A R |

| 5’-ggagaactggggcgcctcaag-3’ | This paper | TGFB3 RGE SOE F |

| 5’-ggcgccccagttctccacgg-3’ | This paper | TGFB3 RGE SOE R |

| 5’-gtgttgtacagtcccagcacc-3’ | This paper | TGFB3 R2 |

| 5’-ctctacgcgtactagtggcgcgccgg-3’ | This paper | GFP F |

| 5’-ttacttgtacagctcgtccatgcc-3’ | This paper | GFP R |

| 5’-gactcactatagggagacccaagctgg-3’ | This paper | TGFB3 N Term F |

| 5’-gtccaaggtggtgcaagtggacagggaccctgaaac-3’ | This paper | TGFB3SOER |

| 5’-ctgtccacttgcaccaccttggac-3’ | This paper | TGFB3SOEF |

| 5’-ggtgagcctaagcttgctcaagatctg-3’ | This paper | TGFB3 N Term R |

| 5’-gtccaaggtggtgctagtggacagggaccctgaaac-3’ | This paper | TGFB3C4SSOER |

| 5’-ctgtccactagcaccaccttggac-3’ | This paper | TGFB3C4SSOEF |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| Human TGF-β1_pLX307 | Rosenbluh et al., 201681 | Addgene, Plasmid #98377 |

| Human TGF-β1 RGE_IRES2 EGFP puro pLX307 | This paper | N/A |

| Human TGF-β1 RGD_R249A_IRES2 EGFP puro pLX307 | This paper | N/A |

| Human TGF-β1 RGE_R249A_IRES2 EGFP puro pLX307 | This paper | N/A |

| Human L-TGF-β1_RGD_Lasso3 puro pLX307 | This paper | N/A |

| Integrin αv truncated, αvTr pcDM8 | Nishimura et al., 199425 | N/A |

| Integrin β8 truncated, β8Tr pcDNA6 | Nishimura et al., 199482 | N/A |

| β8 cDNA pBABE puro | Cambier, et al., 20 0024 | N/A |

| HA-GARP pcDNA3 | Cuende et al., 201578 | N/A |

| HIS SBP-GARP tr pcDNA6 | This paper | N/A |

| HIS SBP-GARP tr SpyCatcher pcDNA6 | This paper | N/A |

| Integrin αv full length, αvfl pCDVnRa | Nishimura et al., 199425 | N/A |

| Integrin β8 full length, pCDβ8FlNeo | Nishimura et al., 199482 | N/A |

| SpyCatcher | Keeble, et al., 201983 | Addgene, Plasmid #133447 |

| pLVE-hTGFβ3-IRES-RED | Brunger, et al., 201484 | Addgene, Plasmid #52580 |

| Human TGF-β3 RGD IRES RED pLX307 | This paper | N/A |

| Human TGF-β3 RGD R277A IRES RED pLX307 | This paper | N/A |

| Human TGF-β3 RGE R277A IRES RED pLX307 | This paper | N/A |

| Human TGF-β3 RGE IRES RED pLX307 | This paper | N/A |

| Human TGF-β3 RGD IRES GFP pLX307 | This paper | N/A |

| Human TGF-β3 RGD R277A IRES GFP pLX307 | This paper | N/A |

| Human TGF-β3 RGE R277A IRES GFP pLX307 | This paper | N/A |

| Human TGF-β3 RGE IRES GFP pLX307 | This paper | N/A |

| Human TGF-βR2-Fc | Seed, et al, 202127 | N/A |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| MotionCor2 | Zheng et al., 201785 | https://msg.ucsf.edu/software; RRID:SCR_016499 |

| Relion 3.0 | Zivanov et al., 201886 | https://cam.ac.uk/relion; RRID:SCR_016274 |

| SerialEM | Mastronarde, 200587 | http://bio3d.colorado.edu/SerialEM/; RRID:SCR_017293 |

| cryoSPARC | Punjani, et al., 201788 | https://cryosparc.com; RRID:SCR_016501 |

| PyEM | Daniel Asarnow, Yifan Cheng Lab | https://github.com/asarnow/pyem; https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3576630 |

| UCSF Chimera | Pettersen, et al., 200489 | https://www.cgl.ucsf.edu/chimera; RRID:SCR_004097 |

| UCSF ChimeraX | Meng, et al, 202390 | https://www.cgl.ucsf.edu/chimerax/ RRID:SCR_015872 |

| COOT | Emsley, et al, 201091 | https://www2.mrclmb.cam.ac.uk/personal/pemsley/coot/; RRID:SCR_014222 |

| PHENIX | Adams, et al., 201092 | http://www.phenixonline.org; RRID:SCR_014224 |

| Clustal Omega | Madeira, et al., 201993 | https://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo/; RRID:SCR_001591 |

| Prism 9 | (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). | https://www.graphpad.com/scientific-software/prism/; RRID:SCR_002798 |

| SpectroFlo | CyTek Biosciences | https://cytekbio.com/pages/spectro-flo |

| FlowJo™ v10.10 | Becton Dickinson and Company | https://www.flowio.com RRID:SCR_008520 |

| Deposited data | ||

| αvβ8/L-TGF-β1/GARP | This study | PDB: 8E4B, EMD-27886, EMD-28061, EMD-28062 |

| L-TGF-β1/GARP | This study | PDB: 8EG9, EMD-2811 |

| L-TGF-β3/GARP | This study | PDB: 8EGC, EMD-28114 |

| αvβ8/L-TGF-β3 | This study | PDB: 8EGA, EMD-28112 |

| Other | ||

| QUANTIFOIL® R 1.2/1.3 on Au 300 mesh grids Holey Carbon Film | Quantifoil | Product: N1-C14nAu30-01 |

| UltrAuFoil® R 1.2/1.3 on Au 300 mesh grids Holey Gold Supports | Quantifoil | N1-A14nAu30-01 |

| Quantifoil 400 mesh 1.2/1.3 holey carbon gold grid | Ted Pella | Q425AR-14 |

| Quantifoil 400 mesh 1.2/1.3 holey carbon copper grid | Ted Pella | 658-300-CU |

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND STUDY PARTICIPANT DETAILS

Mice

129SX1V/J × C57BL/6 Tgfb1 fl/+ mice (Jax) with loxP3 sites flanking tgfb1 exon 3 were crossed to 129X1SV/J × C57BL/6 Rosa 26-cre mice (Ozgene) to create tgfb1+/− mice which were intercrossed to produce tgfb1 −/− mice33,94. Tgfb1 mice with a mutation in the furin cleavage site M13177.1c.1184-5AG>GC (p.Arg278Ala) were created at Ozgene (Perth, WA, Australia) using a conditional knock-in strategy on a C57Bl/6 background (Figure S2). The targeting vector consisting of 5’ homology arm containing tgfb1 exon 3 followed a murine tgfb1 cDNA minigene spanning exon 4–7, followed by a neomycin resistance cassette flanked by flippase recognition target sites (Frt), and the entire minigene and neo cassette flanked by loxP3 sites, which was inserted into intron 3, which was followed by exon 4, intron 4 and exon 5 with a mutation (AC to GC) in R278 to change the furin cleavage motif 275RHRR278 to 275RHRA278 (R278A) followed by a 3’ homology arm. Successful targeting and germline transmission was followed by excision of the Frt flanked neo cassette to create a conditional KI (cKI) allele. Upon cre-mediated recombination, the loxP3 wild-type tgfb1 exon 4–7 cDNA minigene can be excised and replaced with the tgfb1 R278A mutant allele (Figure S2). C57BL/6 heterozygous (tgfb1 cKI/+) or homozygous (tgfb1 cKI/cKI) mice were crossed to C57BL/6 Rosa 26-cre mice (Ozgene). The resulting C57BL/6 KI/WT mice were mated to WT 129X1SV/J mice to generate 129X1SV/J × C57BL/6 tgfb1R278A/+ mice. Alternatively, 129X1SV/J × C57BL/6 tgfb1 cKI R278A /+ mice were crossed to 129X1SV/J × C57BL/6 Rosa 26-cre/WT mice (Ozgene) to create knock-in tgfb1R278A/+ mice. Initial genotyping was performed using tail genomic DNA isolated and genotyped by PCR (Kapa) using primers TGFb1 1F, and TGFB1 KI/cKI 4R which produce a 654 bp band for the KI and 620 bp band for the WT allele. Subsequent genotyping was performed using WT or KI specific primers (TGFb F WT only or TGFb F KI only, paired with TGFb WT/KI rev) Tgfb1R278A/+ mice breeding pairs from either strategy were intercrossed to produce tgfb1R278A/tgfb1R278A mice. Mice were screened for flippase (Flp) rosa 26-cre using a primer mixture (ROSAWT F, ROSAFlp F, ROSAcre F, ROSA R) and flp + mice removed from the colony. WT, tgfb1R278A/tgfb1R278Aor tgfb1R278A/tgfb1WT mice heterozygous or null for Rosa 26-cre and null for Flp were intercrossed and used for survival experiments. Live litters containing KI/KI mice were produced from intercrossing tgfb1R278A/tgfb1R278A or tgfb1R278A/tgfb1WT mice, or crossing tgfb1R278A/tgfb1R278A to tgfb1R278A/tgfb1WT.To confirm mutant mRNA production from the KI and knock-out alleles, RNA was extracted from tail clippings, cDNA synthesized and amplified using the respective primer pairs tgfb1 Ex3/4 cDNA F and tgfb1 ex 6/7 cDNA R, and tgfb1 Ex1/2 cDNA F and tgfb1 Ex4/5 cDNA R and the products sequenced. To confirm the absence of mature TGF-β1 protein in the KO and absence of released mature TGF-β1 in the KI mice, immunoblots were performed using an antibody to mouse mature TGF-β1 (Abcam, ab179695). Serum was precleared 3 times with Protein G Sepharose beads to deplete IgG prior to immunoblotting. Spectral flow cytometry was performed on peripheral blood, or spleen from tgfb1−/−, KI/KI (tgfb1R278A/tgfb1R278A) or appropriate age and littermate matched controls (WT/WT. WT/KO or WT/KI). Histologic analysis of various organs were scored on an inflammation scale of 0–3 (0 = no inflammation; 1 = scattered lymphocytes infiltrating into tissues; 2 = distinct aggregates of lymphocytes infiltrating into tissues; 3 = diffuse inflammation infiltrating tissue in dense sheets of lymphocytes) (Table S1). Total inflammation score represents the sum of all individual organ inflammation scores.

Cell lines

Transformed mink lung TGF-β reporter cells (TMLC)47 were a gift from J. Munger (New York University Medical Center, New York, NY, USA) and were stably transfected with L-TGF-β1 (RGD/RGD), L-TGF-β1 (RGD/RGE), L-TGF-β1 (RGE/RGE), L-TGF-β3 (RGD/RGD), L-TGF-β3_lasso3 with or without GARP, as previously described22. TMLC cells were grown in DMEM + 10% FBS + penicillin-streptomycin + amphotericin B, cultured at 37°C in a humidified incubator, 5% CO2.

MFB-F11 cells were a gift from Tony Wyss-Coray (Stanford University, School of Medicine). MFB are a mouse fibroblast line from tgfb1−/− mice which were stably transfected with an SBE-SEAP reporter cassette with a hygromycin resistance cassette and clone F11 isolated by limiting dilution54. MFB-F11 cells were stably transduced with human ITGB8 construct using retroviral particles from the Phoenix amphotropic viral packaging cell line (Phoenix-AMPHO, ATCC). MFB-F11 cells were maintained in DMEM + 10% FBS + penicillin-streptomycin + amphotericin B, cultured at 37°C in a humidified incubator, 5% CO2. β8 expression was maintained by supplementing basal media with 5 μg/mL puromycin. Phoenix cells were maintained in DMEM + 10% FBS + penicillin-streptomycin + amphotericin B, cultured at 37°C in a humidified incubator, 5% CO2.

DNA constructs