Abstract

Inhaled delivery of messenger RNA (mRNA) using lipid nanoparticle (LNP) holds immense promise for treating pulmonary diseases or serving as a mucosal vaccine. However, the unsatisfactory delivery efficacy caused by the disintegration and aggregation of LNP during nebulization represents a major obstacle. To address this, we develop a charge-assisted stabilization (CAS) strategy aimed at inducing electrostatic repulsions among LNPs to enhance their colloidal stability. By optimizing the surface charges using a peptide-lipid conjugate, the leading CAS-LNP demonstrates exceptional stability during nebulization, resulting in efficient pulmonary mRNA delivery in mouse, dog, and pig. Inhaled CAS-LNP primarily transfect dendritic cells, triggering robust mucosal and systemic immune responses. We demonstrate the efficacy of inhaled CAS-LNP as a vaccine for SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant and as a cancer vaccine to inhibit lung metastasis. Our findings illustrate the design principles of nebulized LNPs, paving the way of developing inhaled mRNA vaccines and therapeutics.

Subject terms: Nanoparticles, Drug delivery, Nucleic-acid therapeutics, Biomaterials - vaccines

The instability of lipid nanoparticles during nebulization hinders inhaled mRNA vaccines. Here, the authors report on a charge-assisted stabilization strategy using a peptide-lipid conjugate to improve lipid nanoparticle stability, enabling mRNA-based mucosal vaccines for SARS-CoV-2 and lung cancer.

Introduction

The approval of messenger RNA (mRNA)-based COVID-19 vaccines has revolutionized the field of vaccine development and opened up a realm of possibilities for developing mRNA medicines targeting a wide range of diseases1. Inhaled delivery of mRNA has emerged as a promising approach for treating various pulmonary diseases, including cystic fibrosis and cancer2. A particularly compelling application of inhaled mRNA lies in its capability to trigger mucosal immune responses that act as the first line of defense against respiratory pathogens by controlling their proliferation and transmission3. Despite its promises, the intricate physiology and protective mechanism of the respiratory system represent significant barriers to efficient inhaled mRNA delivery4. Several carriers such as polymers5,6, exosomes7, and lipid nanoparticles (LNPs)8–11 were recently developed for inhaled mRNA delivery. It’s worth noting that, apart from LNPs, polymer- and exosome-based carriers still lack clinical validation. LNPs approved for clinical use are synthesized through the self-assembly of ionizable lipids, helper lipids, cholesterol, and polyethylene glycol (PEG)-lipids via hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions12. While LNPs have shown good efficacy following injection-based administrations in clinical settings, their use in inhaled delivery encounters distinct challenges13.

For inhaled delivery, solutions of LNPs need to be aerosolized into micron-sized droplets via a nebulizer for deep lung deposition14. However, this nebulization process subjects LNPs to high shear forces15,16, leading to their aggregation, disintegration, and premature mRNA leakage. The leaked free mRNA can barely penetrate the mucus layer and enter cells, resulting in poor pulmonary transfection17,18. Therefore, maintaining LNP colloidal stability during nebulization is a crucial challenge for inhaled mRNA delivery. Recent studies have shown that increasing the PEG-lipid content can enhance LNP stability during nebulization8,9. The thick PEG layer acts as a steric barrier that counterbalances the attractive van der Waals forces responsible for LNP aggregation19. However, the increased PEG-lipid content also significantly reduces the mRNA encapsulation efficiency, cellular uptake, and endosomal escape of LNP, ultimately resulting in unsatisfactory mRNA expression20,21. Consequently, new LNP formulations capable of achieving efficiently inhaled mRNA delivery are still very much needed to fully harness the therapeutic potential of mRNA.

Other than steric hindrance, classic theories of colloidal stability suggest that nanoparticles can also be stabilized by electrostatic repulsions, which are determined by the surface charge of nanoparticles and the ionic strength of the surrounding solution22,23. Notably, the surface charges of clinical LNPs are nearly neutral under physiological conditions24. We hypothesized that introducing additional surface charge could create electrostatic repulsions among LNPs, thus greatly improving the colloidal stability of LNP during nebulization. A recent study showed that using an acidic buffer could confer positive charges to LNPs, thus stabilizing them during nebulization and efficiently delivering mRNA to the lung without apparent toxicity25. These results suggest that lungs may have a better tolerance to positively charged nanoparticles, which often arouse toxicity issues after systemic injections in clinical studies26,27. Nonetheless, these positively charged LNPs mainly transfect epithelial cells of the lung, which are less optimal for delivering mRNA vaccines.

Herein, we developed an LNP formulation termed CAS-LNP (charge-assisted stabilization of LNP) by integrating an optimized amount of negatively charged peptide-lipid conjugates into the traditional four-component LNP (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Movie 1). CAS-LNP demonstrated excellent stability during nebulization and significantly improved mRNA delivery efficacy after inhalation. The proposed mechanism of charge-assisted stabilization of LNP was carefully investigated and demonstrated. The CAS strategy is a universal methodology that can be easily applied to other LNP formulations to improve their mRNA delivery efficiencies after inhalation. We further found that inhaled CAS-LNP predominantly targets dendritic cells within the lungs, making CAS-LNP an ideal candidate for delivering mRNA vaccines. Inhaled delivery of mRNA encoding the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.529 (Omicron variant) using CAS-LNP elicited robust systemic and mucosal immune responses. In addition, we demonstrated the versatility of CAS-LNP as both prophylactic and therapeutic cancer vaccines using mouse metastatic lung cancer models.

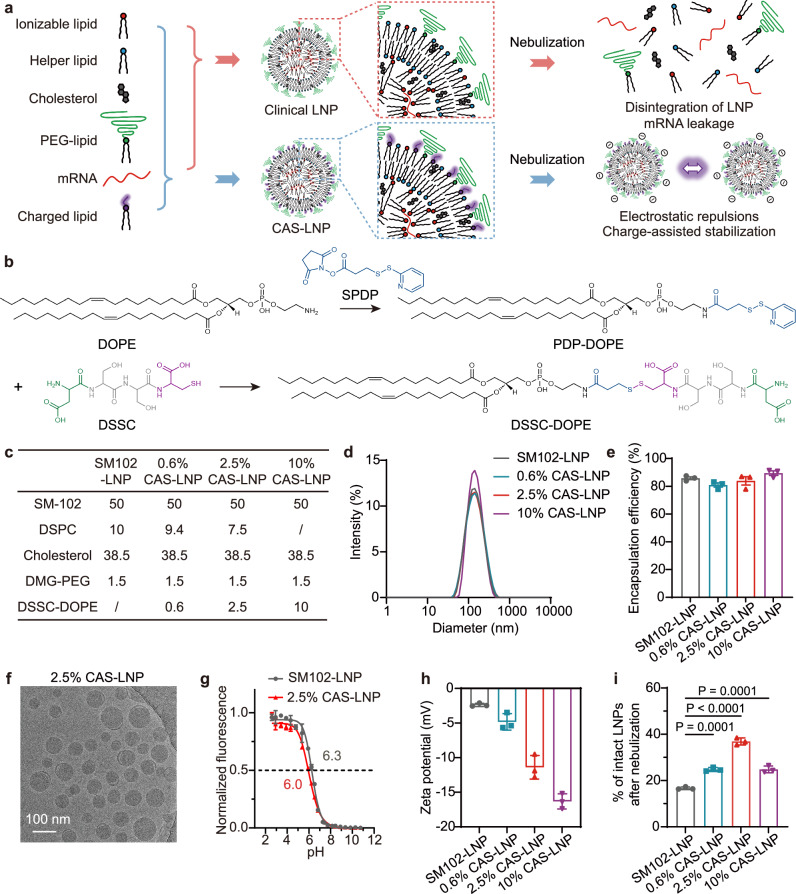

Fig. 1. Synthesis and characterization of CAS-LNP.

a Schematic illustrating the preparation and mechanism of CAS-LNP. By incorporating charged lipids into clinical LNP formulation, the increased electrostatic repulsions among CAS-LNPs enhance LNP stability during nebulization. b Synthetic scheme of DSSC-DOPE. c Formulations of SM102-LNP and CAS-LNPs. d Representative size distribution of LNPs measured by DLS. e The mRNA encapsulation efficiency of LNPs. f A representative Cryo-TEM image of 2.5% CAS-LNP. g pKa of SM102-LNP and 2.5% CAS-LNP measured by 2-(p-toluidino)−6-napthalene sulfonic acid (TNS) assay. h Zeta potentials of SM102-LNP and CAS-LNPs. i Percentage of intact LNPs after nebulization in 0.3×PBS. Data are shown as mean ± standard deviation (SD) (n = 3 technical replicates). Statistical significance was analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Results and discussion

Fabrication of CAS-LNP with negative surface charge

mRNA, which is rich in negative charges due to the phosphate diester on nucleotide monomers, is mainly encapsulated within LNPs through electrostatic attraction with positively charged ionizable lipids. Therefore, if introducing another negatively charged lipid to impart a negative surface charge to LNPs, the group electronegativity and hydrophilicity of this lipid must be carefully considered. The negatively charged lipid could compete with mRNA for binding with ionizable lipid, thus interfering with mRNA encapsulation. In addition, lipids with weak hydrophilic head groups may have difficulty distributing to the LNP surface. Other than phosphate, carboxylic acid is another common negatively charged group in organisms. The pKa of phosphate diester (~ 1.5) is lower than that of carboxylic acid (~ 2–5). Therefore, the positively charged ionizable lipid should have a stronger affinity for binding to the phosphate groups of mRNA than carboxylic acid.

Among different sources of carboxylic acids, we selected amino acids due to their high biocompatibility and facile preparation28. Through the design of amino acid sequences, peptides can effectively enhance hydrophilicity and adjust the charge properties. By linking peptides to long alkyl chain lipids to construct negatively charged peptide-lipid conjugate, it can stably bind to the surface of LNPs. Based on this, we designed the peptide sequence to be aspartic acid, serine, serine, and cysteine (DSSC) because DSSC has one cysteine group for easy conjugation with lipids, one aspartic acid-bearing carboxylic acid side chain to provide a negative charge, and two uncharged, hydrophilic serine to improve the hydrophilicity of peptide-lipid conjugate that drives its presence on the surface of LNP. We then used DSSC to synthesize a negatively charged, amphiphilic oligopeptide-helper lipid conjugate (Fig. 1b). Although PEG-lipid is on the surface of LNP, we did not conjugate DSSC to the PEG-lipid because the amount of PEG has been shown to greatly affect LNP stability during nebulization. To eliminate the effect of PEG on testing our hypothesis of charge-assisted stability of LNP, we chose 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (DOPE) to conjugate oligopeptide because DOPE has been shown to mainly reside on the outer membrane of LNP29.In addition, the amino group of DOPE can be easily modified with N-succinimidyl-3-(2-pyridyldithio)propionate (SPDP) to yield PDP-DOPE for subsequent conjugation with DSSC. The successful synthesis of PDP-DOPE and DSSC-DOPE was demonstrated using mass spectrometry (MS), 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), and ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy (UV-Vis, Supplementary Figs. 1–3).

We adopted the LNP formulation utilized in the mRNA-1273 COVID-19 vaccine, comprising heptadecan-9-yl 8-((2-hydroxyethyl) (6-oxo-6-(undecyloxy) hexyl) amino) octanoate (SM-102) as ionizable lipid, 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphochline (DSPC) as helper lipid, cholesterol, and 1,2-dimyristoyl-rac-glycero-3-methoxy polyethylene glycol-2000 (DMG-PEG2000), at a molar ratio of 50:10:38.5:1.5, respectively (SM102-LNP)30. To create CAS-LNP, DSSC-DOPE was incorporated into SM102-LNP by replacing equimolar amounts of DSPC during microfluidic mixing with mRNA encoding firefly luciferase (mFluc). We integrated different amounts of DSSC-DOPE (0.6%, 2.5%, and 10% of all lipids by mole) to modulate the surface charge of CAS-LNP (Fig. 1c). Dynamic light scattering (DLS) measurements showed that CAS-LNPs and SM102-LNP have similar hydrodynamic diameters ranging from 130 to 140 nm with narrow size distributions (Fig. 1d). The mRNA encapsulation efficiencies for both CAS-LNPs and SM102-LNP exceeded 80% (Fig. 1e). Cryogenic transmission electron microscopy (Cryo-TEM) image depicted a spherical morphology of 2.5% CAS-LNP with a solid core (Fig. 1f). These results suggest that the incorporation of DSSC-DOPE did not affect the assembly of LNP and the overall mRNA encapsulation. The pKa of 2.5% CAS-LNP is similar to that of SM102-LNP (Fig. 1g). The 2.5% CAS-LNP maintained its colloidal stability in PBS at 37 °C (Supplementary Fig. 4). Zeta-potential measurements indicated that SM102-LNP possessed a nearly neutral surface charge (− 2.39 mV), consistent with previous findings31. The surface potential of CAS-LNPs gradually declined with an increase in the amount of DSSC-DOPE (Fig. 1h), confirming the successful integration of DSSC-DOPE onto the outer membrane of LNP. The zeta-potential data also suggest that the negative charges of DSSC are not entirely shielded by the surface PEG.

Stability and mRNA delivery efficacy of inhaled CAS-LNP

We next evaluated whether CAS-LNP could maintain colloidal stability under high shear force during nebulization. While most LNPs used for intravenous or intramuscular administration are dispersed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)32, the high ion concentration in PBS could shield electrostatic repulsions among CAS-LNPs. To mitigate this effect, we dispersed all LNPs in 0.3 × PBS to reduce the solvent’s ionic strength. We employed a clinically used vibrating mesh nebulizer (Aerogen Solo) that utilizes high-frequency oscillation of a porous metal mesh to aerosolize SM102-LNP or CAS-LNP solutions. To evaluate LNP stability during nebulization, we quantified the percentage of intact LNPs by measuring the amount of encapsulated mRNA before and after nebulization. As shown in Fig. 1i, ~ 17% of intact SM102-LNP was detected after nebulization, suggesting significant disintegration and mRNA leakage. In contrast, all CAS-LNPs exhibited improved stability compared to SM102-LNP, suggesting that increasing LNP surface charge is an effective strategy to enhance its colloidal stability. Interestingly, despite CAS-LNP with 10% of DSSC-DOPE (10% CAS-LNP) having the lowest surface potential, its stability was lower than that of 2.5% CAS-LNP and comparable to that of 0.6% CAS-LNP. Previous studies indicated that LNPs formulated with DSPC exhibit higher stability than those with DOPE due to the higher melting point and fully saturated alkyl chain of DSPC33. These findings suggest that DSPC also contributes to LNP stability during nebulization, but its impact is overshadowed by that of surface charges. Therefore, 2.5% CAS-LNP, which possesses an optimized ratio of DSPC and charged DSSC-DOPE, exhibited the highest stability during nebulization.

We then studied whether the enhanced stability of CAS-LNP during nebulization could improve its mRNA delivery efficacy in mice. To ensure consistent dosing across all groups, equal amounts of SM102-LNP or CAS-LNPs encapsulating mFluc in 0.3 × PBS were nebulized, collected, and administered to mice via oropharyngeal aspiration (Fig. 2a). Mice were imaged by an in vivo imaging system (IVIS) at various time points post-administration. As shown in Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 5, SM102-LNP and CAS-LNPs exhibited similar kinetics of mRNA expression, which peaks at 6 h and gradually declines thereafter. All CAS-LNPs displayed higher luminescence intensity in the lung area compared to SM102-LNP. Quantitative analysis (Fig. 2c) demonstrated that 2.5% CAS-LNP exhibited the highest mRNA expression among all groups. Ex vivo imaging of major organs at 24 h post-administration (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. 6) revealed exclusive mRNA expression in the lung for all LNPs, affirming the efficiency of inhalation as a lung-targeted delivery method with minimal off-target expression. Further quantitative analysis of excised lungs (Fig. 2e) showed a 6.9-fold increase in mRNA expression with 2.5% CAS-LNP compared to SM102-LNP. These findings indicate a direct correlation between the improved colloidal stability of CAS-LNP during nebulization and its enhanced mRNA delivery efficacy.

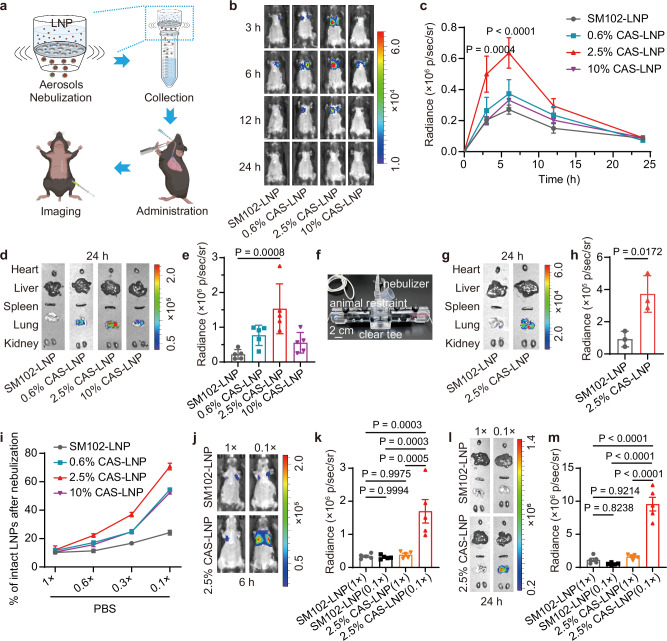

Fig. 2. Stability and mRNA delivery efficiency of CAS-LNP after nebulization.

a Workflow for evaluating mRNA expression of nebulized LNPs in mice. b Representative IVIS images and (c) quantitative analysis of luminescence in mice treated with SM102-LNP or CAS-LNPs in 0.3 × PBS at different time points. d Representative IVIS images of major organs (heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney) and (e) quantitative analysis of lungs at 24 h post-administration. Each dose contains 1 µg of mFluc per mouse (n = 5 biologically independent samples). Data are shown as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical significance was analyzed by two-way (c) or one-way (e) ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. f Photograph of custom apparatus for inhaled administration to three mice simultaneously. g Representative IVIS images of major organs and (h) quantitative analysis of lungs treated with SM102-LNP or 2.5% CAS-LNP in 0.3 × PBS at 24 h post-administration (n = 3 biologically independent samples). Data are shown as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was analyzed by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test. i Percentage of intact LNPs after nebulization in PBS of varying ionic strength (n = 3 technical replicates). Data are shown as mean ± SD. j Representative IVIS images and (k) quantitative analysis of luminescence in mice treated with SM102-LNP or 2.5% CAS-LNP in 1 × or 0.1 × PBS at 6 h post-administration. l Representative IVIS images of major organs and (m) quantitative analysis of lungs at 24 h post-administration (n = 5 biologically independent samples). Data are shown as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was analyzed by one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Figure 2a was created in BioRender. Lu, X. (2024) BioRender.com/y08x203. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To compare the oropharyngeal aspiration method of nebulized solution with inhalation and further validate the enhanced mRNA delivery of CAS-LNP post-inhalation, we connected the nebulizer to a custom apparatus that allowed simultaneous inhalation by three mice (Fig. 2f). Subsequently, nebulized SM102-LNP or 2.5% CAS-LNP containing 100 µg of mFluc was administered. The lungs of mice were excised at 24 h post-inhalation and imaged using IVIS. As shown in Fig. 2g, h and Supplementary Fig. 7, CAS-LNP exhibited a 4.0-fold increase in mRNA expression compared to SM102-LNP, consistent with the results obtained with the oropharyngeal aspiration of nebulized LNP solution (Fig. 2e). These results not only affirm the feasibility of our protocol for evaluating inhaled mRNA delivery of LNP but also reinforce the improved mRNA delivery efficacy of CAS-LNP.

Nevertheless, it is important to rule out the possibility that the increased mRNA delivery efficacy is solely due to changes in LNP formulation, regardless of stability during nebulization. To address this, we administered pre-nebulized 2.5% CAS-LNP or SM102-LNP to mice via intravenous injection. IVIS images (Supplementary Fig. 8) indicated similar biodistribution patterns for both 2.5% CAS-LNP and SM102-LNP, with the liver showing the highest mRNA expression. However, SM102-LNP displayed approximately a 2.3-fold higher mRNA expression compared to 2.5% CAS-LNP, suggesting that the incorporation of DSSC-DOPE negatively affected the mRNA expression of SM102-LNP prior to nebulization. This observation is reasonable considering that CAS-LNP possesses more negative charges, which may exhibit reduced cellular uptake. In vitro cellular uptake studies using dendritic cells indicated that 2.5% CAS-LNP displayed a 2.4-fold lower cellular uptake compared to SM102-LNP (Supplementary Fig. 9). CAS-LNP and SM102-LNP exhibited similar pKa (Fig. 1g), suggesting that DSSC may not affect the endosomal escape of LNP. Indeed, hemolysis study of red blood cell (RBC) indicated that 2.5% CAS-LNP possesses similar membrane disruption capability at endosomal pH with that of SM102-LNP (Supplementary Fig. 10). To better understand the influence of DSSC-DOPE on the cellular uptake, dendritic cells were treated with small-molecule inhibitors of endocytosis, macropinocytosis, and phagocytosis prior to incubation with LNPs. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 11, macropinocytosis was identified as the major pathway for SM102-LNP uptake, consistent with previous reports34,35. CAS-LNP enters cells through both macropinocytosis and caveolae-mediated endocytosis, which is likely due to the different charges and DSSC modification on the surface.

Taken together, these data demonstrate that the effective inhaled delivery of mRNA by CAS-LNP is dependent on its colloidal stability during nebulization, which compensates for the reduced cellular uptake. These findings emphasize a fundamental difference in LNP design principles for nebulized delivery compared to systemic injections. While the efficacy of LNP following intravenous or intramuscular administrations largely hinges on their cellular uptake and endosomal escape, inhaled LNPs necessitate a delicate balance between their colloidal stability during nebulization and subsequent interactions with cells.

Mechanism of the enhanced delivery efficiency of CAS-LNP

To explore whether the improved stability of inhaled CAS-LNP is due to its surface charge, we first evaluated CAS-LNP stability during nebulization in PBS with varying salt concentrations. The presence of salt can screen electrostatic repulsions among LNPs, potentially compromising the enhanced stability conferred by surface charges. As expected, all CAS-LNPs exhibited nearly identical stability to SM102-LNP in 1 × PBS, indicating the complete loss of charge-assisted stabilization during nebulization (Fig. 2i). However, as we gradually decreased salt concentrations, we observed a progressively more substantial increase in the percentage of intact CAS-LNPs compared to SM102-LNP after nebulization. We then investigate the inhaled delivery efficacy of SM102-LNP and 2.5% CAS-LNP in 0.1 × and 1 × PBS in mice. While SM102-LNP showed low and similar mRNA expression in both solutions, 2.5% CAS-LNP in 0.1 × PBS exhibited robust luminescence signals in the lung (Fig. 2j–m, Supplementary Figs. 12 and 13). Quantitative analysis of mice and excised lungs revealed that 2.5% CAS-LNP in 0.1×PBS achieved approximately 5.5-fold (Fig. 2k) and 20.3-fold (Fig. 2m) higher mRNA expression, respectively, compared to SM102-LNP in 0.1 × PBS. However, mRNA expression significantly reduced when 2.5% CAS-LNP was used in 1 × PBS. Collectively, these findings demonstrate that the colloidal stability of CAS-LNP during nebulization originates from its surface charge. 2.5% CAS-LNP is highly effective for inhaled mRNA delivery when used in a solution with low ionic strength. Therefore, we selected 2.5% CAS-LNP in 0.1 × PBS for further investigation and referred to it as CAS-LNP unless specifically stated otherwise.

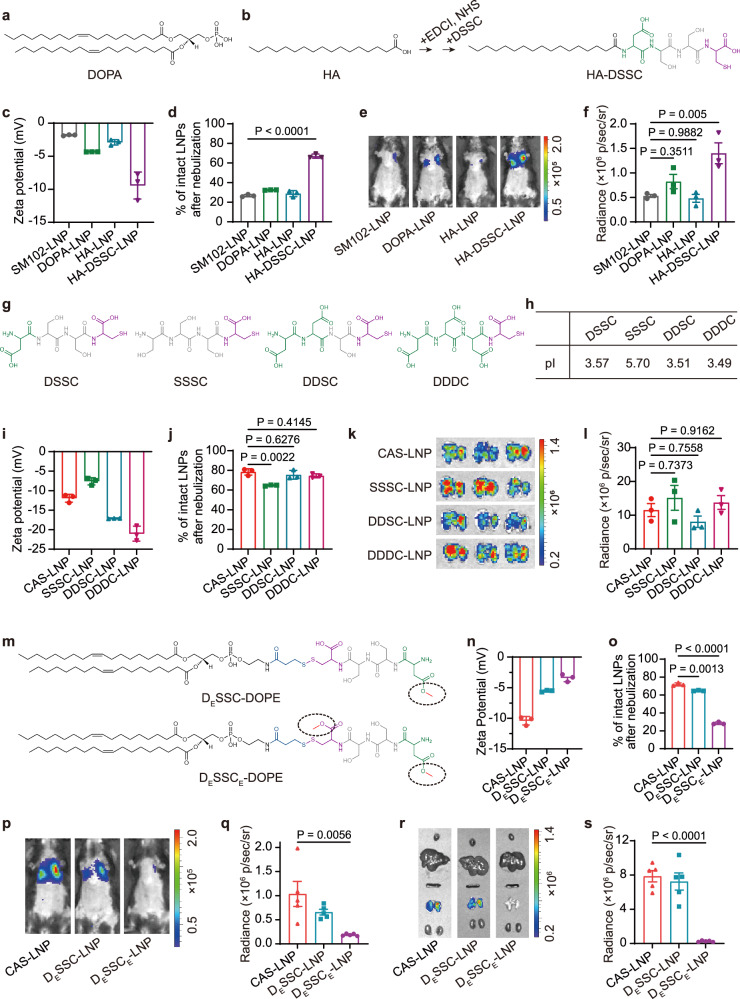

To validate the design principles of DSSC that has to carry carboxylic acid groups as the source of negative charge and sufficient hydrophilicity to present on the LNP surface, we tried different negatively charged molecules including 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphate (DOPA) (bearing a phosphate monoester, Fig. 3a) and heptadecanoic acid (HA) (bearing a carboxylic acid group, Fig. 3b) as alternatives. We replaced DSSC-DOPE in CAS-LNP with an equivalent amount of DOPA or HA to yield DOPA-LNP or HA-LNP, respectively. All LNPs were successfully synthesized with uniform sizes (Supplementary Fig. 14a). However, neither DOPA nor HA improved the stability of LNP during nebulization or nebulized delivery efficiency (Fig. 3d–f and Supplementary Fig. 14c). Specifically, the use of DOPA reduced mRNA encapsulation and exhibited only slightly declined surface potential (− 4.33 mV, Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 14b), suggesting that the phosphate monoester of DOPA may compete with mRNA for binding with ionizable lipids. On the other hand, the incorporation of HA did not affect mRNA encapsulation efficacy (Supplementary Fig. 14b) and the surface potential of LNP (− 2.89 mV, Fig. 3c), suggesting that the hydrophilicity of the carboxylic group of HA was insufficient to allow for its arrangement on the surface of LNPs. Consequently, HA was incorporated into the core of LNPs, failing to impart surface charge to LNPs. Upon modifying HA with DSSC peptide (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 15), the resulting HA-DSSC conjugate effectively decreased the surface potential of HA-DSSC-LNP (− 9.43 mV, Fig. 3c), significantly enhanced LNP stability during nebulization (Fig. 3d) and mRNA expression after nebulization (Fig. 3e, f and Supplementary Fig. 14c). These results underscore the importance of careful design when selecting negatively charged molecules, which should possess ideal pKa and hydrophilicity.

Fig. 3. Mechanism study of CAS-LNP.

a Chemical structures of DOPA, HA, and HA-DSSC (b). c Zeta potentials of SM102-LNP, 2.5% DOPA-LNP, 2.5% HA-LNP, and 2.5% HA-DSSC-LNP (n = 3 technical replicates). Data are shown as mean ± SD. d Percentage of intact LNPs after nebulization in 0.1 × PBS (n = 3 technical replicates). Data are shown as mean ± SD. e Representative IVIS images and (f) quantitative analysis of luminescence in mice at 6 h post-administration (n = 3 biologically independent samples). Data are shown as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was analyzed by one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. g Chemical structures of DSSC, SSSC, DDSC, and DDDC. h Isoelectric points of DSSC, SSSC, DDSC, and DDDC. i Zeta potentials of CAS-LNP, SSSC-LNP, DDSC-LNP, and DDDC-LNP (n = 3 technical replicates). Data are shown as mean ± SD. j Percentage of intact LNPs after nebulization in 0.1 × PBS (n = 3 technical replicates). Data are shown as mean ± SD. k Representative IVIS images of lungs and (l) quantitative analysis at 24 h post-administration (n = 5 biologically independent samples). Data are shown as mean ± SEM. m Chemical structures of DESSC-DOPE and DESSCE-DOPE. Either one or both carboxyl groups of DSSC were converted to methyl esters. n Zeta potentials of CAS-LNP, DESSC-LNP, and DESSCE-LNP (n = 3 technical replicates). Data are shown as mean ± SD. o Percentage of intact LNPs after nebulization in 0.1 × PBS (n = 3 technical replicates). Data are shown as mean ± SD. p Representative IVIS images and (q) quantitative analysis of luminescence in mice treated with CAS-LNP, DESSC-LNP, or DESSCE-LNP at 6 h post-administration (n = 5 biologically independent samples). Data are shown as mean ± SEM. r Representative IVIS images of major organs and (s) quantitative analysis of lungs at 24 h post-administration (n = 5 biologically independent samples). Data are shown as mean ± SEM. The statistical significance of this figure was analyzed by one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To further validate the CAS strategy, we designed three peptides—SSSC, DDSC, and DDDC—carrying one, three, and four carboxylic acid groups, respectively (Fig. 3g). The calculated isoelectric points (pIs) of SSSC, DSSC, DDSC, and DDDC were 5.70, 3.57, 3.51, and 3.49, respectively (Fig. 3h). All these peptides have pIs below 5.7, indicating a negative charge in 0.1 × PBS (pH = 7.4). We synthesized SSSC-DOPE, DDSC-DOPE, and DDDC-DOPE, and used them as replacements for DSSC-DOPE to fabricate SSSC-LNP, DDSC-LNP, and DDDC-LNP, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 16). All LNPs were successfully synthesized with uniform sizes and high mRNA encapsulation efficiencies (Supplementary Fig. 17). The surface potential gradually decreased with the increasing number of carboxylic acid groups (Fig. 3i). These LNPs exhibited greatly enhanced stability during nebulization and inhaled mRNA delivery efficiency compared to SM102-LNP (Fig. 3j–l). While SSSC-LNP showed slightly lower stability, likely due to its less negative surface charge (− 7.6 mV), this did not significantly affect overall mRNA delivery post-inhalation. These results suggest a correlation between the surface charge and LNP stability, with higher negative surface charges providing better stability. However, when the surface charge of LNPs reaches a certain threshold, further increases in negative charge do not result in additional improvements in stability or mRNA delivery efficacy. Collectively, ensuring sufficient negative surface charge is critical for the charge-assisted stability of LNP.

To investigate the role of carboxyl groups on DSSC in conferring negative charges to CAS-LNP, we performed esterification on one carboxyl group of aspartic acid or both carboxyl groups of aspartic acid and cysteine to yield DESSC-DOPE or DESSCE-DOPE, respectively (Fig. 3m). UV-Vis and MS measurements confirmed the successful synthesis of both compounds (Supplementary Figs. 18 and 19). Subsequently, we replaced DSSC-DOPE in CAS-LNP with an equivalent amount of DESSC-DOPE or DESSCE-DOPE to yield DESSC-LNP or DESSCE-LNP, respectively. All LNPs were successfully synthesized with uniform sizes and high mRNA encapsulation efficiencies (Supplementary Fig. 20). The surface potential gradually increased with the increasing number of esterified carboxylic acid groups (Fig. 3n). We then evaluated their stability during nebulization and subsequent mRNA delivery efficacy in vivo. DESSC-LNP, bearing one carboxyl group, exhibited slightly decreased stability (Fig. 3o) and mRNA expression compared to CAS-LNP (Fig. 3p–s and Supplementary Figs. 21 and 22), indicating that even a single carboxyl group contributes to LNP stability. In contrast, despite the presence of a phosphate group on DOPE, DESSCE-LNP, with both carboxyl groups blocked, exhibited a marked decrease in stability during nebulization and reduced mRNA delivery efficacy. Both DESSC-LNP and SSSC-LNP, which contain one phosphate group on DOPE and one carboxyl group on the peptide, exhibited lower surface potential and greatly improved stability compared to DESSCE-LNP. HA-DSSC-LNP, which contains two carboxyl groups but lacks the phosphate group, also demonstrated comparable zeta potential, stability, and inhaled mRNA delivery efficiency with DOPE-DSSC-LNP. Collectively, these data demonstrate that the carboxyl groups on peptides are crucial for providing the negative surface charges of CAS-LNP, thereby enhancing its stability during nebulization and overall delivery efficacy. While the phosphate group on DOPE may contribute some surface charge to CAS-LNP, its overall impact on stability and delivery efficacy is limited.

To determine whether the enhanced stability of CAS-LNP during nebulization stems from the improved stability of individual LNPs or from the electrostatic repulsions among LNPs, we characterized the mechanical properties of CAS-LNP and SM102-LNP using liquid-phase atomic force microscopy (AFM). Our results showed that Young’s modulus and the maximum force required to break individual CAS-LNP and SM102-LNP are nearly identical (Fig. 4a–d), indicating that the inclusion of negatively charged peptide-lipid conjugate (DSSC-DOPE) had no discernible impact on the mechanical stability of individual LNPs. Therefore, instead of improving the mechanical stability of individual LNPs, the addition of DSSC-DOPE enhances the electrostatic repulsions among LNPs, thus preventing LNPs from aggregation during nebulization.

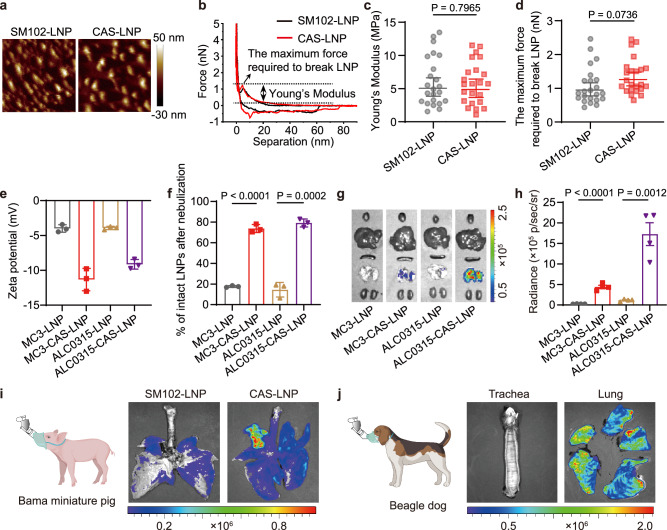

Fig. 4. Universality of CAS-LNP.

a Representative aqueous AFM amplitude images and (b) force curves of SM102-LNP and CAS-LNP. c Young’s modulus and (d) the maximum force required to break LNP calculated from the force curves of individual LNP (n = 23 technical replicates). Data are shown as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was analyzed by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test. e Zeta potentials of MC3-LNP, MC3-CAS-LNP, ALC0315-LNP, and ALC0315-CAS-LNP (n = 3 technical replicates). Data are shown as mean ± SD (f) Percentage of intact LNPs after nebulization (n = 3 technical replicates). Data are shown as mean ± SD. The statistical significance was analyzed by one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. g Representative IVIS images of major organs and (h) quantitative analysis of lungs at 24 h post-administration (n = 4 biologically independent samples). Data are shown as mean ± SEM. The statistical significance was analyzed by one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. i IVIS images of tracheas and lungs of dog and pig (j) at 3 h post-administration. Dog and pig were administered with 0.3 mg/kg of mFluc through the Aerogen Solo nebulizer with a custom nose cone. Figure 4i and j were created in BioRender. Lu, X. (2024) BioRender.com/s18b330. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

CAS is a universal strategy

To evaluate the universality of the CAS strategy, we applied the CAS strategy to other clinical LNP formulations utilized in the patisiran for the treatment of the polyneuropathy of hereditary transthyretin-mediated amyloidosis (MC3-LNP) and the BNT162b2 COVID-19 vaccine (ALC0315-LNP), respectively. MC3-CAS-LNP and ALC0315-CAS-LNP were fabricated by incorporating 2.5% DSSC-DOPE to replace equimolar amounts of DSPC (Supplementary Fig. 23a). Zeta-potential measurements (Fig. 4e) indicated that MC3-LNP and ALC0315-LNP also possessed nearly neutral surface charges (− 3.99 mV and − 3.92 mV, respectively), and the surface potentials of MC3-CAS-LNP and ALC0315-CAS-LNP decreased (− 11.33 mV and − 9.14 mV). We then evaluated their stability during nebulization and subsequent mRNA delivery efficacy in vivo. While MC3-LNP and ALC0315-LNP are unsuitable for nebulized delivery, MC3-CAS-LNP and ALC0315-CAS-LNP exhibited significantly enhanced stability during nebulization (Fig. 4f) and mRNA expression compared to their original formulations (Fig. 4g, h and Supplementary Fig. 23b). These data clearly demonstrate that the CAS strategy can be easily applied on other LNP formulation, making it an ideal strategy to convert LNPs that are originally unsuitable for nebulized delivery into an inhalable formulation.

Furthermore, we have compared the mRNA delivery efficacy of CAS-LNP with recently reported inhaled formulations (Supplementary. Fig. 23a). Our results showed that CAS-LNP shows significantly higher mRNA delivery efficacy compared to T1-525, NLD19 and LNP2-236 (Supplementary. Fig. 23b, c). It is worth noting that those inhaled formulations all utilize the positively charged DOTAP lipid (28% in T1-5, 5% in NLD1, and 50% in LNP2-2). DOTAP carries a quaternary amine that has a stronger binding affinity to mRNA compared to the tertiary amine of ionizable lipids. Therefore, DOTAP mainly resides inside of LNP. For example, SORT LNPs using 10% or 40% DOTAP by mole showed surface potential of ~ 1.34 and 7.57 mV37. Lung SORT LNP with 50% DOTAP showed a surface potential of − 0.89 mV38. These results suggest that adding DOTAP did not introduce a surface charge to LNP. DOTAP may improve pulmonary delivery of LNP through another mechanism that is still not fully elucidated.

Inhaled CAS-LNP delivers mRNA to the lungs of large animals

We next studied whether CAS-LNP could efficiently deliver mRNA in larger animals, which possess more comparable physiology of respiratory system to humans than mice39,40. We first compared the mRNA expression efficiency in Bama miniature pigs after inhalation of SM102-LNP and CAS-LNP. The pigs received 0.3 mg/kg of mFluc in LNPs via nebulization. Three hours post-administration, the trachea and lungs were isolated after intraperitoneal injection of luciferin for subsequent bioluminescence imaging. As depicted in Fig. 4i, the expression of mFluc in the CAS-LNP-treated group is higher than that in the SM102-LNP-treated group. Furthermore, we validated that CAS-LNP can also successfully transfect the lung in Beagle dogs (Fig. 4j). These results demonstrated that CAS-LNP could efficiently deliver mRNA through inhalation across different species, including mouse, dogs, and pigs, suggesting its great potential for further clinical translation.

Inhaled CAS-LNP penetrates the mucus layer and transfects immune cells

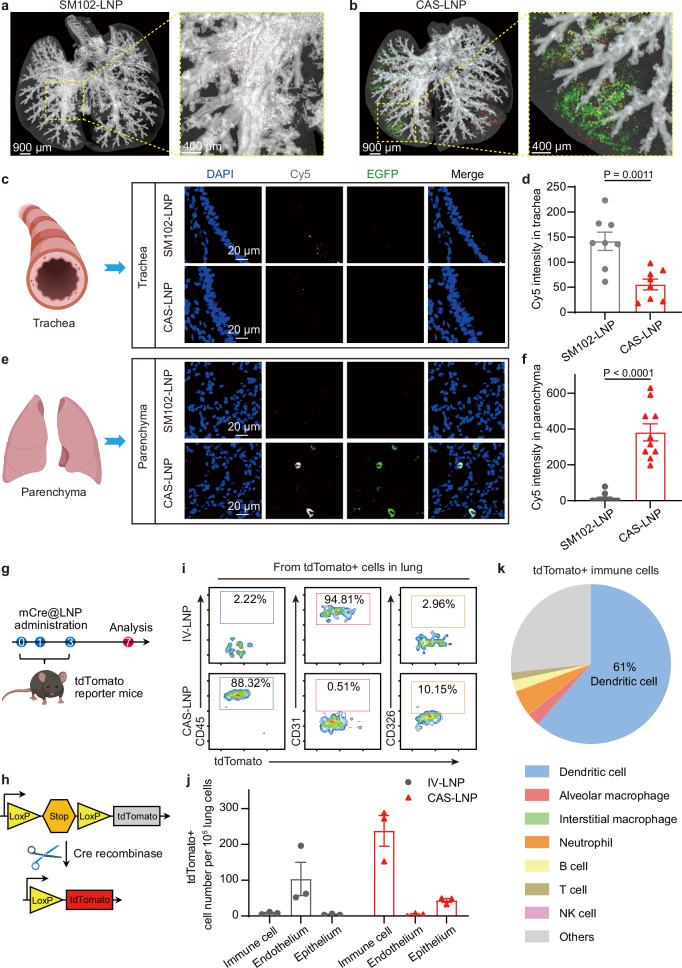

After nebulization, CAS-LNPs need to traverse the mucus layer to reach lung cells for mRNA expression41. Given the preserved structural integrity of CAS-LNP during nebulization, we hypothesized that the PEG-coating of intact CAS-LNP could facilitate its trafficking across the mucus barrier42. To investigate this, we encapsulated Cy5-labeled mRNA encoding enhanced green fluorescent protein (Cy5-mEGFP) in CAS-LNP or SM102-LNP. These LNPs were nebulized, collected, and administered to mice through oropharyngeal aspiration. The whole lungs were isolated at 30 min post-administration and imaged by IVIS and three-dimensional fluorescent imaging. As shown in Fig. 5a, b, and Supplementary Fig. 24, CAS-LNP treated mouse exhibited greatly stronger Cy5 and EGFP fluorescence in the parenchyma than SM102-LNP. We then separated the tracheas and lungs and dissected them into thin slices for confocal laser scanning microscopy. As shown in Fig. 5c–f and Supplementary Figs. 25 and 26, both Cy5 and EGFP signals in lung parenchyma were exclusively found in the CAS-LNP treated group. This suggests effective penetration of the mucus layer by CAS-LNP, leading to EGFP expression in pulmonary cells. In contrast, strong Cy5 signals from the trachea and minimal Cy5 and EGFP signals from parenchyma were observed in the SM102-LNP treated group. Such observation is likely due to the leakage of Cy5-mEGFP from SM102-LNP during nebulization. Leaked mRNA can barely penetrate the mucus layer and is prone to degradation by enzymes or clearance from the airway via mucociliary clearance43.

Fig. 5. Inhaled CAS-LNP delivers mRNA to specific cells of mice.

Three-dimensional fluorescent imaging of lungs in mice treated with inhaled SM102-LNP (a) or CAS-LNP (b) encapsulating Cy5-mEGFP at 30 min post-administration. Green and red signals represent EGFP and Cy5, respectively. Representative confocal microscopy images of excised tracheas (c) and lungs (e). Quantitative analysis of Cy5 fluorescence intensity in trachea (d) (n = 8 technical replicates) and pulmonary parenchyma (f) (n = 10 technical replicates). Data are shown as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was analyzed by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test. g Treatment scheme for evaluating the mRNA expression in different cell types of inhaled CAS-LNP or intravenously injected IV-LNP. Each mouse received 5 µg of mCre per dose. h Schematic illustrating that the expression of Cre recombinase deletes the stop cassette and activates the expression of tdTomato in C57BL/6-Rosa26-CAG-LSL-tdTomato mice. i Representative flow cytometry measurements and quantitative analysis (j) of immune cells (CD45), endothelial cells (CD31), and epithelial cells (CD326) expressing tdTomato in the lungs after different treatments (n = 3 biologically independent samples). Data are shown as mean ± SEM. k The percentage of tdTomato + dendritic cell, alveolar macrophage, interstitial macrophage, neutrophil, B cell, T cell, and NK cell among immune cells of CAS-LNP treated lungs (n = 4 biologically independent samples). Figure 5c and e were created in BioRender. Lu, X. (2024) BioRender.com/m16g625. Figure 5g was created in BioRender. Lu, X. (2024) BioRender.com/j51w648. Figure 5h was created in BioRender. Lu, X. (2024) BioRender.com/m96i222. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Recent studies have shown successful lung-targeted mRNA delivery through intravenous injection using diverse LNP formulations44,45. However, it is important to note that the specific lung cell subtype targeted by intravenously administered LNPs may differ substantially from those of inhaled LNPs, as the former reaches the lungs through the bloodstream, while the latter enters through the airway. To identify the specific lung cell subtype transfected by intravenously injected LNP (IV-LNP) and inhaled CAS-LNP, we synthesized a lung-targeting IV-LNP following a previously published formulation44. The lung-targeted mRNA expression of IV-LNP was validated (Supplementary Fig. 27). Subsequently, we encapsulated mRNA encoding Cre recombinase (mCre) into CAS-LNP or IV-LNP and administered the same doses of mCre to C57BL/6-Rosa26-CAG-LSL-tdTomato mice via inhalation or intravenous injection, respectively (Fig. 5g). These mice possess a loxP-flanked stop cassette controlling the expression of the fluorescent tdTomato protein, which is activated only when Cre recombinase is present (Fig. 5h). Thus, cells with mCre expression produce tdTomato fluorescence.

After administering three doses of LNPs, we analyzed lung cells with mCre expression using flow cytometry, with specific markers for immune (CD45), endothelial (CD31), and epithelial (CD326) cells (Supplementary Fig. 28). As shown in Fig. 5i, j, IV-LNP exhibited exclusive mRNA expression in endothelial cells, with minimal expression in immune and epithelial cells. In contrast, inhaled CAS-LNP showed the highest mRNA expression in immune cells, intermediate expression in epithelial cells, and minimal expression in endothelial cells. We further analyzed the subpopulations of CAS-LNP transfected immune cells (Supplementary Figs. 29 and 30). As shown in Fig. 5k and Supplementary Fig. 31, over 60% of tdTomato + immune cells are dendritic cells (DCs), the primary antigen-presenting cells, making CAS-LNP an ideal candidate for delivering mRNA vaccines. Inhaled CAS-LNP also showed mRNA expression in neutrophils (~ 5.3%), alveolar macrophages (~ 2.6%), B cells (~ 2.3%), T cells (~ 1.6%), and slight mRNA expression in interstitial macrophages, and natural killer (NK) cells. These results showed the distinct transfection profiles of IV-LNP and inhaled CAS-LNP, highlighting the importance of considering the administration route when utilizing LNPs for mRNA delivery to the lung. The choice of LNP formulation should be carefully tailored to the specific lung cell types targeted. IV-LNP has implications where precise delivery to endothelial cells is desired, whereas inhaled CAS-LNP holds great potential for the development of vaccines or other mRNA-based therapies aimed at modulating immune responses.

Inhaled CAS-LNP induced strong systemic and mucosal immune responses

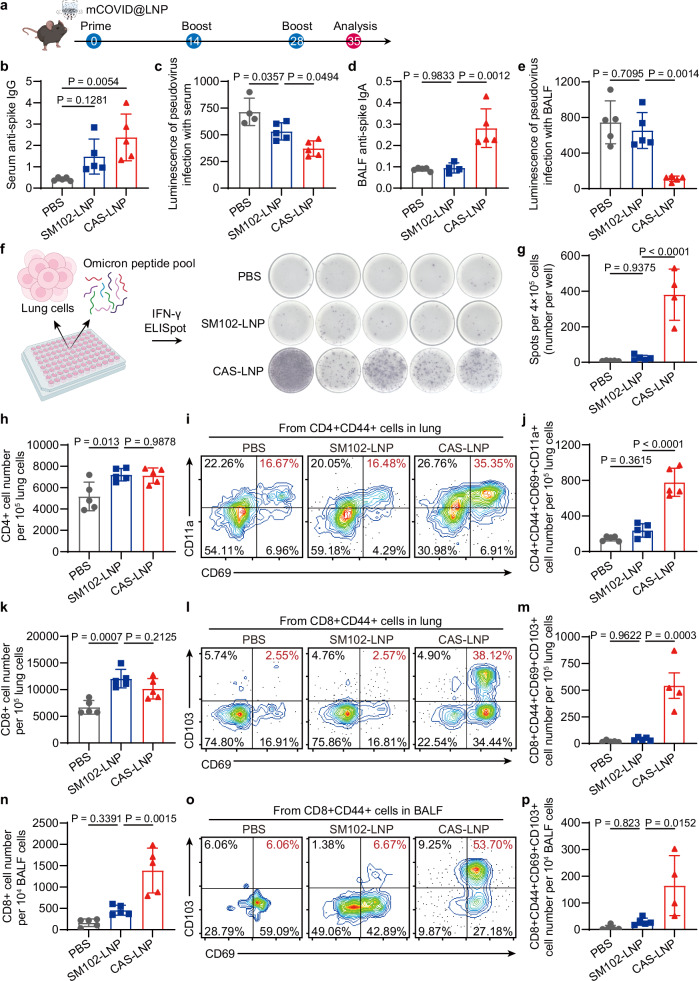

To assess the potential of CAS-LNP as an inhaled vaccine for COVID-19, we synthesized mRNA encoding the spike protein of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant (mCOVID) and encapsulated it into CAS-LNP or SM102-LNP. These LNPs were then nebulized, collected, and administered through oropharyngeal aspiration to female C57BL6 mice on days 0, 14, and 28, with each dose containing 5 µg of mCOVID per mouse (Fig. 6a). Mice receiving inhaled PBS were used as the controls. Subsequently, we isolated serum, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF), and lung tissues to analyze the systemic and mucosal immune responses one week after the third immunization. We first evaluated the antigen-specific total IgG antibodies in serum by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). CAS-LNP induced higher total IgG responses compared to SM102-LNP (Fig. 6b and Supplementary Fig. 32). We then analyzed the neutralizing ability of serum using an Omicron pseudovirus-based assay. Notably, mice vaccinated with CAS-LNP exhibited significantly enhanced neutralizing ability compared to those receiving SM102-LNP and PBS treatments (Fig. 6c), indicating the effectiveness of CAS-LNP in inducing a systemic humoral immune response.

Fig. 6. CAS-LNP induces potent systemic and mucosal immune responses as a COVID-19 vaccine.

a Vaccination regimen in mice. CAS-LNP or SM102-LNP containing mCOVID were nebulized and administered to mice on days 0, 14, and 28. Each dose contains 5 µg of mCOVID per mouse. b ELISA analysis of Omicron spike protein-specific IgG in serum and IgA in BALF (d) from mice treated with PBS, SM102-LNP, or CAS-LNP. The virus-neutralizing ability of serum (c) and BALF (e) was measured using an Omicron pseudovirus assay in ACE2-expressing HEK-293T cells (n = 5 biologically independent samples). Data are shown as mean ± SD. f Optical images and (g) quantitative analysis of IFN-γ-spot-forming cells via ELISpot assay. Lung cells of mice were plated and stimulated with an Omicron peptide pool (n = 5 biologically independent samples). Data are shown as mean ± SD. Number of CD4 + (h) and CD8 + (k) T cells in the lung of mice (n = 5 biologically independent samples). Representative flow cytometry plots and quantitative analysis of CD4 + (i, j) (n = 5 biologically independent samples) and CD8 + (l, m) (n = 5 biologically independent samples for PBS and SM102-LNP treated groups, n = 4 biologically independent samples in CAS-LNP treated group) TRM cells among cells in the lung of mice. Flow cytometry analysis showing the number of CD8 + T cells (n) (n = 5 biologically independent samples) and CD8 + TRM cells (o, p) (n = 5 biologically independent samples for PBS and SM102-LNP treated groups, n = 4 biologically independent samples for CAS-LNP treated group) in BALF. Data are shown as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was analyzed by one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Figure 6a was created in BioRender. Lu, X. (2024) BioRender.com/c71w817. Figure 6f was created in BioRender. Lu, X. (2024) BioRender.com/a39t997. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

COVID-19 viruses enter the bloodstream via the respiratory tract. Mucosal IgA plays a pivotal role as the initial defense against viruses attempting entry through the respiratory mucosa46. To investigate the mucosal immune response, we assessed antigen-specific IgA levels in BALF using ELISA. SM102-LNP exhibited IgA levels comparable to the PBS group (Fig. 6d), indicating its limited ability to trigger an IgA response. In contrast, CAS-LNP induced significantly higher IgA levels, resulting in the potent virus-neutralizing ability of BALF, as measured by the Omicron pseudovirus-based assay (Fig. 6e). These results suggest that CAS-LNP stimulated potent humoral immune responses within the airway, which could confer superior protection against respiratory viruses. Furthermore, we analyzed the cellular immune response in the lung by restimulating lung cells with the peptide pool of Omicron. The interferon-gamma (IFN-γ)-producing cells were analyzed using the IFN-γ enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot (ELISpot) assay. Remarkably, CAS-LNP treatment showed the highest number of IFN-γ-producing cells, which was 15.5-fold and 46.4-fold greater than those observed in the SM102-LNP and PBS-treated mice, respectively (Fig. 6f, g). The robust induction of IFN-γ-producing cells by CAS-LNP indicates the activation of a potent, antigen-specific cellular immune response in the lung, which can efficiently target and eliminate infected cells, thus enhancing pathogen clearance and limiting infection severity.

Tissue-resident memory T (TRM) cells are crucial for protection against various respiratory pathogens and have been proposed as the benchmark of mucosal immune responses47. Recent studies indicate that TRM cells in mucosal tissue offer long-term protection against mucosal pathogens, including SARS-CoV-2, where TRM cells are induced in the lungs of both severe and mild COVID-19 patients and persist for up to 10 months48. We analyzed the population of T cells and TRM in the lungs and BALFs by flow cytometry (Supplementary Figs. 33–37). SM102-LNP and CAS-LNP treatments exhibited similar numbers of CD4 + and CD8 + T cells in the lung, which are both higher than those of PBS treatment (Fig. 6h, k), suggesting that LNPs elicit proinflammatory responses following inhalation. The development of TRM requires exposure of T cells to antigens first. Thus, the enhanced mRNA expression of CAS-LNP could contribute to elevated TRM levels compared to SM102-LNP. Indeed, CAS-LNP treatment led to a significant increase in both CD4 + TRM (CD4 + CD44 + CD69 + CD11a +, Fig. 6i, j) and CD8 + TRM cells (CD8 + CD44 + CD69 + CD103 + Fig. 6l, m) in the lung compared to SM102-LNP and PBS treatments. In addition, CAS-LNP increased the population of CD8 + T cells and CD8 + TRM cells within BALF (Fig. 6n–p).

Taken together, these findings highlight the potency of CAS-LNP in triggering robust systemic and mucosal immune responses. As an inhaled COVID-19 vaccine candidate, CAS-LNP demonstrates the ability to stimulate multiple arms of the immune system to provide comprehensive protection against the virus. The superior stability of CAS-LNP during nebulization plays a crucial role in its efficacy, as it results in significantly enhanced mRNA delivery and expression of the antigen in the respiratory tract compared to SM102-LNP. These findings highlight the importance of lipid nanoparticle formulations in modulating mucosal immune responses and provide valuable insights for the design of future immunization strategies aimed at strengthening mucosal immunity for respiratory protection.

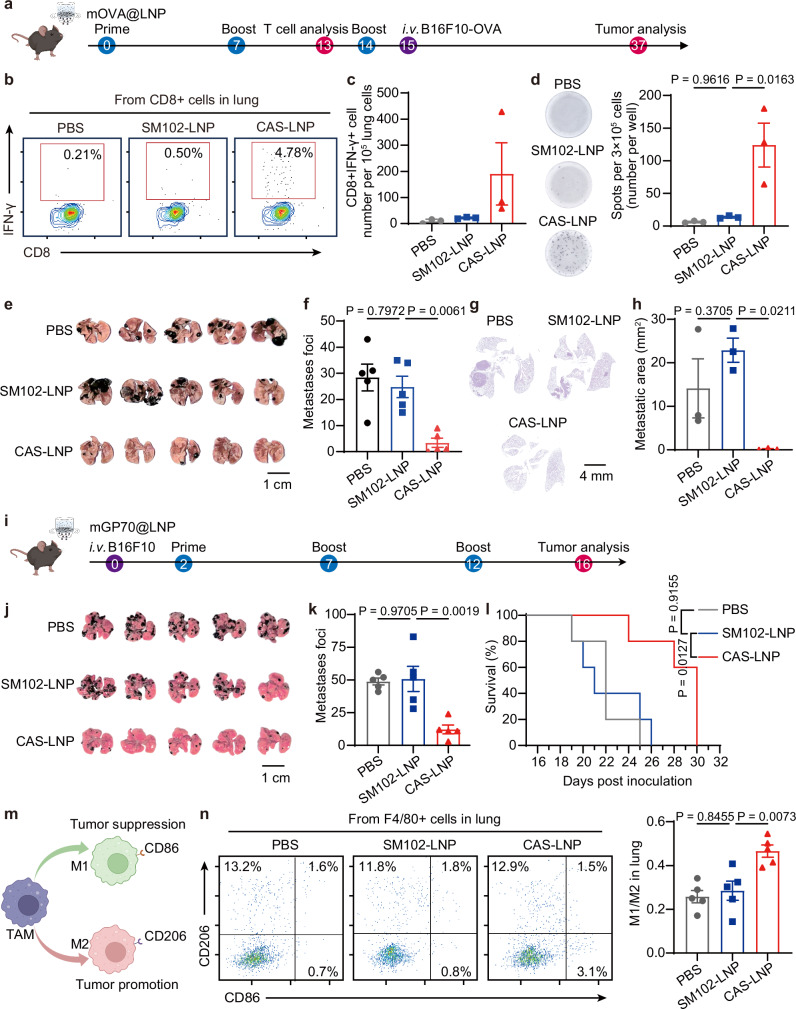

CAS-LNP effectively delivers mRNA cancer vaccines

CAS-LNP could serve as a platform for delivering diverse mRNA-based vaccines and therapeutics to the lungs. To demonstrate its versatility, we conducted a proof-of-concept experiment using CAS-LNP as a prophylactic cancer vaccine to inhibit lung metastasis. We encapsulated an ovalbumin-encoded mRNA (mOVA) into CAS-LNP and SM102-LNP and administered them to mice through inhalation at days 0, 7, and 14 (Fig. 7a). The lungs of mice were isolated on day 13 for the analysis of antigen-specific cytotoxic T cells (Supplementary Fig. 38). CAS-LNP increased the percentage of OVA-specific IFN-γ + CD8 + T cells by approximately 8.7-fold and 21.4-fold compared to SM102-LNP and PBS treatments, respectively (Fig. 7b, c). ELISpot analysis of antigen-specific, IFN-γ-producing cells (Fig. 7d and Supplementary Fig. 39) in the spleen showed the same trend, indicating that CAS-LNP triggered systemic anti-tumor immune response. The enhanced local and systemic anti-tumor immune responses imply good efficacy in inhibiting lung metastasis. To evaluate the prophylactic efficacy of CAS-LNP, we injected 2 × 105 B16F10-OVA (a mouse melanoma cell line expressing OVA) cells into mice through intravenous injection one day after the third immunization. On day 22, after tumor inoculation, the lungs were collected to evaluate tumor metastasis. Notably, CAS-LNP treatment significantly reduced the number of metastatic foci (Fig. 7e, f) and the relative area of tumors in the lungs (Fig. 7g, h and Supplementary Fig. 40) compared to the SM102-LNP and PBS-treated groups, demonstrating its efficacy as a prophylactic cancer vaccine.

Fig. 7. CAS-LNP as cancer vaccines.

a Schematic of treatment regimen on a metastatic B16F10-OVA tumor model. CAS-LNP or SM102-LNP containing mOVA were nebulized and administered to mice on days 0, 7, and 14. Each dose contains 5 µg of mOVA per mouse. b Representative flow cytometry plots and (c) quantitative analysis of IFN-γ + CD8 + T cells among lung cells on day 13 post-prime (n = 3 biologically independent samples). Data are shown as mean ± SEM. d Optical images and quantitative analysis of IFN-γ-spot-forming cells among splenocytes on day 13 post-prime via ELISpot assay. Splenocytes of mice were stimulated with SIINFEKL peptide (n = 3 biologically independent samples). Data are shown as mean ± SEM. e Photographs of lungs bearing metastatic tumors from treated mice. Scale bar is 1 cm. f Number of metastatic foci on the lung of treated mice (n = 5 biologically independent samples). Data are shown as mean ± SEM. g Representative images of H&E-stained lung sections following treatments. h Quantitative analysis of metastatic tumor area among the overall lung area (n = 3 biologically independent samples). Data are shown as mean ± SEM. i Schematic of treatment regimen on a metastatic B16F10 tumor model. CAS-LNP or SM102-LNP containing mGP70 were nebulized and administered to mice on days 2, 7, and 12. Each dose contains 5 µg of mGP70 per mouse. j Photographs of lungs bearing metastatic tumors from treated mice. Scale bar is 1 cm. k Number of metastatic foci on the lung and (l) Survival analysis of treated mice (n = 5 biologically independent samples). Data are shown as mean ± SEM. m Schematic showing the polarization of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs). n Representative flow cytometry plots and quantitative analysis of M1 and M2 macrophages (n = 5 biologically independent samples). Data are shown as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was analyzed by one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Figure 7a was created in BioRender. Lu, X. (2024) BioRender.com/n34x441. Figure 7i was created in BioRender. Lu, X. (2024) BioRender.com/h65g080. Figure 7m was created in BioRender. Lu, X. (2024) BioRender.com/m806034. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To assess the efficacy of CAS-LNP as a therapeutic cancer vaccine, we designed an mRNA encoding the envelope glycoprotein 70 (GP70), a native B16F10 tumor antigen49. After intravenously injecting C57BL/6 mice with 2 × 105 B16F10 cells, we encapsulated mRNA encoding GP70 (mGP70) into CAS-LNP or SM102-LNP and administered these LNPs to mice through inhalation on days 2, 7, and 12 post-tumor inoculation (Fig. 7i). As shown in Fig. 7j–l, CAS-LNP treatments significantly reduced the number of metastatic foci in the lung and prolonged animal survival compared to SM102-LNP or PBS treatments. We further analyzed the phenotype of macrophages within the lung (Supplementary Fig. 41) since the M1/M2 ratio is a commonly reported prognostic indicator of cancer vaccines50,51. M1 macrophages possess pro-inflammatory and tumor-inhibiting properties, while M2 macrophages exhibit immunosuppressive and tumor-promoting characteristics (Fig. 7m). As shown in Fig. 7n, CAS-LNP treatment greatly improved the population of M1 macrophages, resulting in an elevated M1/M2 ratio compared to SM102-LNP or PBS-treatments. These results demonstrated that inhaled CAS-LNP stimulated proinflammatory macrophages and effectively inhibited tumor metastasis as a therapeutic vaccine. Although preclinical models like B16F10 may not fully represent metastatic lung cancer, our study demonstrates the potential of an inhaled mRNA vaccine for treatment. With mRNA’s ability to encode diverse tumor antigens, CAS-LNP shows promise for targeting various lung cancers. Future research should investigate its efficacy and safety in clinically relevant models.

Safety profiles of CAS-LNP

CAS-LNP is prepared by integrating a small quantity of DSSC-DOPE conjugates into the clinically approved LNP formulation. DOPE has been widely used in liposomal formulations for biomedical applications and exhibited good safety profiles52. DSSC is an oligopeptide made of natural amino acids. Therefore, we did not anticipate the apparent toxicity of CAS-LNP. Throughout the treatment period of all in vivo studies, we did not observe any weight loss (Supplementary Fig. 42) or behavior changes in the animals treated with CAS-LNP. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of histological sections of major organs (heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney) showed no obvious change in morphology (Supplementary Figs. 40 and 43). We also evaluated the blood routine, serum biochemical indicators, cytokines, and C-reactive protein at 48 h after administration of CAS-LNPs at three dosages. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 44, CAS-LNP at three different dosages (2.5, 5, and 7.5 µg of mRNA) did not induce noticeable changes in all tests compared to PBS treatment. The CAS-LNP is dissolved in 0.1 × PBS for inhalation. We measured the osmotic pressure (OS) of CAS-LNP in 0.1 × PBS at two different mRNA concentrations. The results showed that CAS-LNP in 0.1 × PBS has comparable OS compared with saline, which is greatly higher than that of 0.1 × PBS (Supplementary Fig. 45). Inhaled drugs are generally tolerant to variations in osmotic pressure, allowing safe use of inhaled solutions such as distilled water53 and hypertonic saline54 in clinical settings. Collectively, these data demonstrated the good safety profile of CAS-LNP.

Collectively, we presented a strategy to enhance the colloidal stability of LNP during nebulization - a critical step for the development of inhaled mRNA vaccines or therapies. Through the integration of negatively charged DSSC-DOPE, the carboxyl groups on the LNP surface induced electrostatic repulsions among LNPs, thus preventing their aggregation and disintegration during nebulization. The molecular design of DSSC-DOPE is critical to endow LNP with a negative surface charge without affecting mRNA encapsulation. The proposed charge-assisted stabilization is inherently different from previous strategies, which use cationic lipids in the core of LNP, excessive PEG on the LNP surface, or excipients in the solution. We demonstrated that CAS is a general strategy that can be easily applied to different LNP formulations to improve their mRNA delivery efficiencies after inhalation. Furthermore, the flexibility of the peptide head group opens broad chemical spaces for optimization of the DSSC-DOPE conjugates to further improve inhaled mRNA delivery efficiency or achieve targeted transfection in different cell types.

Inhaled CAS-LNP exhibits efficient mucus penetration, mRNA expression, and dendritic cell targeting within the lung. Moreover, inhaled CAS-LNP induces robust systemic and mucosal immune responses, positioning CAS-LNP as a promising platform for delivering mucosal mRNA vaccines to control infection, replication, and spread of respiratory pathogens. We further demonstrated the applicability of CAS-LNP as both prophylactic and therapeutic cancer vaccines, indicating its versatility in delivering diverse mRNA vaccines or therapeutics. These findings exemplify the design principles behind inhaled LNPs, which require harmony between colloidal stability during nebulization and subsequent interactions with cells. These results pave the way for a broad spectrum of inhaled mRNA vaccines or treatments targeting a wide range of pulmonary diseases.

Methods

Synthesis of DSSC-DOPE

All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich or Beijing Innochem Science & Technology unless noted specifically. Equal moles of DOPE (Avanti Polar Lipids) and SPDP (GlpBio) were dissolved in a round bottom flask. Five equivalents of triethylamine were then added to the reaction mixture. The reaction was stirred at room temperature for 12 h and then purified using silica gel chromatography to yield PDP-DOPE. To synthesize DSSC-DOPE, equal moles of DSSC (GL Biochem) and PDP-DOPE were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and mixed in a small glass vial charged with a stir bar. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature and monitored by UV-Vis spectrometry to observe the characteristic absorption peak of 2-mercaptopyridine at 343 nm. When the formation of 2-mercaptopyridine reached a plateau, the reaction mixture was dialyzed against water using a dialysis bag with a molecular weight cutoff (MWCO) of 1 kDa to remove unreacted DSSC. After dialysis, the precipitates were collected by centrifugation and thoroughly washed with ethanol to remove unreacted PDP-DOPE. The final precipitates were then lyophilized to yield DSSC-DOPE. The same methods were used to synthesize SSSC-DOPE, DDSC-DOPE, DDDC-DOPE, DESSC-DOPE and DESSCE-DOPE. These molecules were characterized by ESI-MS (Bruker Solarix), MALDI-MS (Bruker UltrafleXtreme), and 1H NMR spectrometry (Bruker AV III 400 HD and Bruker Fourier 300). All the peptides were synthesized using L-amino acids.

Synthesis of HA-DSSC

Heptadecanoic acid (HA), N-(3-Dimethylaminopropyl)-N′-ethyl carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDCI), N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS), N,N-dimethylpyridin-4-amine (DMAP), and triethylamine (Et3N) were dissolved in dichloromethane at a molar ratio of 2:2:1:0.5:2. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 12 h and then purified using silica gel chromatography with dichloromethane: methanol = 100: 1 as eluent to yield HA-NHS. Then, HA-NHS, DSSC, and Et3N were mixed in DMSO at a molar ratio of 1:2:8 and stirred at room temperature for 12 h. Finally, the reaction mixture was dialyzed against water using a dialysis bag with MWCO of 1 kDa to remove unreacted DSSC, and the HA-DSSC was collected by freeze-drying. The yield of HA-DSSC is ~ 61%.

Preparation and characterization of LNP

LNPs were prepared using a microfluidic device with syringe pumps. SM-102 (SINOPEG), D-Lin-MC3-DMA (SINOPEG), ALC-0315 (SINOPEG), C12-200 (SINOPEG), 7C1, DSPC (Avanti Polar Lipids), 1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane (DOTAP), DOPE, cholesterol, DMG-PEG2000 (Avanti Polar Lipids), ALC-0159 (SINOPEG), DSPE-PEG2000 (SINOPEG) were dissolved in ethanol. DSSC-DOPE, SSSC-DOPE, DDSC-DOPE, DDDC-DOPE, DESSC-DOPE, DESSCE-DOPE, HA, and HA-DSSC were dissolved in DMSO. DOPA (Avanti Polar Lipids) was dissolved in methanol. mRNA was dissolved in 50 mM citrate buffer (pH 4.0). mFluc and Cy5-mEGFP were purchased from APExBIO. mCre, mCOVID, and mOVA were synthesized using T7 RNA polymerase-mediated transcription from a linearized DNA template (GenScript). To prepare SM102-LNP, MC3-LNP, ALC0315-LNP, CAS-LNPs, MC3-CAS-LNP, ALC0315-CAS-LNP, DOPA-LNP, HA-LNP, HA-DSSC-LNP, SSSC-LNP, DDSC-LNP, DDDC-LNP, DESSC-LNP, or DESSCE-LNP, the lipids and mRNA were mixed in a 1:3 volume ratio at 1.2 mL/min speed and a N/P ratio of 5.67:1. LNPs were dialyzed overnight using dialysis bags with a MWCO of 14 kDa. To prepare T1-5 or NLD1, the lipids, and mRNA were mixed in an ionizable lipid/mRNA weight ratio of 10:1. To prepare LNP2-2, the lipid solution was rapidly mixed with mRNA in pyrocarbonate at a volume ratio of 1:1, and N/P ratio of 6:1. To prepare IV-LNP, DOTAP, D-Lin-MC3-DMA, DSPC, cholesterol, and DMG-PEG2000 were dissolved in ethanol at a molar ratio of 50:25:5:19.3:0.8, respectively. The lipid solution was then rapidly mixed with mRNA in citrate buffer (50 mM, pH 4.0) at a volume ratio of 1:3 and N/P ratio of 15.37:1. Zetasizer Nano ZS (Malvern) was used for particle size, polydispersity index, and zeta potential measurements. The zeta potential of LNPs was measured in 0.1 × PBS. The mRNA concentration and encapsulation efficiency of LNPs were measured using the RiboGreen (Invitrogen) assay. The pKa values of LNP were determined using the fluorescence probe TNS according to a previously published protocol. Cryo-TEM image was acquired using Themis 300 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). LNPs stored at 37 °C in an incubator were tested for storage stability. The osmotic pressure was measured by an osmolality detector (Tianjin TianHe Analysis Instrument, SMC 30D).

Stability of LNPs during nebulization

500 µL of LNP solution was nebulized using an Aerogen Solo nebulizer. To collect the aerosolized LNP, a 15 mL centrifuge tube (Corning) was attached to the nebulizer’s outlet. The condensed LNP solutions were subsequently collected through mild centrifugation. The RiboGreen assay was employed to quantify the concentrations of encapsulated mRNA in the LNP both before and after nebulization. The percentage of intact LNP after nebulization was determined by dividing the concentration of encapsulated mRNA after nebulization by the concentration before nebulization.

Liquid-phase atomic force microscopy measurement of LNPs

The mica coated with bovine serum albumin was chosen as a solid substrate. 200 µL of LNPs encapsulated with mFluc (equivalent to 10 ng/µL mRNA) was incubated on the substrate for 30 min, followed by AFM measurement.

AFM imaging and force measurements were carried out in aqueous medium at 26 ± 1 °C by using the MultiMode 8-HR AFM (Bruker). Prior to measurements, a soft cantilever was calibrated by the thermal noise method and was immersed in the sample for about 20 min to obtain thermal equilibrium. The deflection sensitivity was calibrated with the manufacturer’s support. AFM images at a resolution of less than 8 nm/pixel were recorded with the following scanning parameters: set point, 0.1 − 0.3 nN; rate: 1.95 Hz; gain: 5.

Images of the LNPs were then extracted using NanoScope Analysis 1.50, from which the maximum height and area-equivalent diameter of each LNP were determined. Prior to the collection of LNPs mechanical data, we validated the cleanliness of our tips by monitoring the force curve at the substrate.

In the Peak Force QNM mode of MultiMode 8-HR AFM (Bruker), a force versus deformation curve was collected with the following parameters: setpoint: 5 nN; z-length: 200 nm; rate: 1.03 Hz. The force value at the jump-in point of the force curve was defined as the maximum force required to break LNPs. The Young’s Modulus was calculated by Eq. (1):

| 1 |

z: Z position, z0: contact point, d: deflection, d0: noncontact deflection, k: spring constant of the cantilever, Rtip: radius of the tip, RLNP: radius of the LNP, determined as the height of LNP, υLNP: Poisson’s ratio of LNP, determined as 0.5 for soft materials, ELNP: Young’s Modulus of the LNP.

Inhaled delivery of LNPs in vivo

All animal experiments reported here were performed according to a protocol approved by the Peking University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee for using mouse (PUIRB-LA2023156) and the Animal Ethics Committee of Beijing Animals Science Biotechnology Co., Ltd. for using beagle dogs and Bama miniature pig (IACUC-AMSS-20230910-03). The studies, study design, results, and findings are not specific to any sex or gender. The animals were maintained in a controlled environment with a 12-h light/dark cycle. The ambient temperature was maintained at 22 ~ 24 °C, and the humidity level was kept at 40 ~ 60%.

Female C57BL/6 mice (6–9 weeks) were obtained from SPF (Beijing) Biotechnology. For in vivo imaging studies, LNPs encapsulating mFluc were nebulized, collected, and administered to mice through oropharyngeal aspiration. Briefly, the mouse was anesthetized and then placed on a vertical operating table. To inhibit the swallowing reflex, the tongue was gently pulled up. The nebulized LNP solution was then added to the oropharynx, allowing it to be inhaled into the lung. The dose of mLuc per mouse is 1 µg. At different time points following administration, the mice received intraperitoneal injections of 0.2 mL D-luciferin potassium (20 mg/mL in saline). Subsequently, the mice were anesthetized using isoflurane in oxygen within a ventilated anesthesia chamber, and in vivo imaging was performed 10 min after the injection using an IVIS (PerkinElmer). For ex vivo imaging, the major organs, including the heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney, were excised and imaged using the IVIS. The bioluminescent images were quantified using Living Image software (PerkinElmer) from the same area of the region of interest (ROI) for each mouse across all groups.

To administer LNP through direct inhalation, mice were placed into a custom-built nose-only exposure system, which allows inhaled administration to three mice at the same time through a tee-joint and three animal restraints (Yuyan Instruments). The nebulizer was positioned on the upward-facing port of the tee-joint. LNP solutions were added dropwise to the nebulizer at a rate of 50 µL per mouse per droplet. After each droplet was nebulized, the clear tee was observed until the vaporized dose had completely cleared. Additional droplets were then added to achieve the desired dose. Once the vapor had cleared following the last droplet, the mice were carefully removed from the restraints for subsequent imaging analysis.

To visualize the distribution of inhaled LNPs in the lung, LNPs encapsulating Cy5-mEGFP were nebulized, collected, and administered to mice through oropharyngeal aspiration. Each mouse received a dose of 5 µg of Cy5-mEGFP. At 30 min post-administration, the mice were euthanized and transcardially perfused with saline followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). The lungs were then collected, fixed in 4% PFA overnight, and imaged by IVIS to evaluate Cy5 and EGFP fluorescence. Then, the fixed lungs were cleared using a tissue clearing kit (Nuohai Life Science, Cat. NH-CR-210701), and imaged by a light-sheet fluorescence microscopy (Nuohai LS18). Subsequent 3D reconstruction and analysis were performed with Imaris software. The reconstructed bronchioles were derived from the autofluorescence signals of lumen margins. For confocal microscopy imaging, the tracheas and lungs of mice received CAS-LNP or SM102-LNP (1 µg of Cy5-mEGFP per mouse) were also harvested at 30 min post-administration, and embedded in optimum cutting temperature (OCT) compound (SAKURA). The OCT-embedded tissues were sliced into 10 µm sections and sealed with an antifade mounting medium containing DAPI (Beyotime). The slides were then imaged using a confocal laser-scanning microscope (Olympus FV1000-IX81). The images were analyzed by ImageJ software.

To study the inhaled delivery of LNPs in large animals, male beagle dogs (12 ~ 14 months, Marshall BioResources) and Bama miniature pigs (4 ~ 6 months, Beijing Farm Animal Research Center) were acclimatized for at least 14 days before experiments. Beagle dogs or Bama miniature pigs were anaesthetized with isoflurane in oxygen using a nose-only exposure mask. AerogenSolo nebulizer was connected to the nose-only exposure mask, and LNPs encapsulating mFluc were nebulized and inhaled by the animals at a dose of 0.3 mg/kg mFluc. The animals received intraperitoneal injections of 20 mg/kg D-luciferin potassium in saline three hours after administration of LNPs. Ten minutes later, the animals were euthanized. The tracheas and lungs of pigs were isolated and imaged. The trachea and lung of the dog were dissected and soaked in 2 mg/mL D-luciferin potassium solution before bioluminescence imaging.

Cellular uptake of LNPs

DC2.4 cells (a mouse dendritic cell line) were cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) medium 1640 basic (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Corning) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco) at 37 °C supplemented with 5% CO2. DC2.4 cells were seeded in 48-well plates with 10,000 cells per well and incubated overnight. Once the cells reached approximately 50% confluency, LNPs encapsulating 100 ng of Cy5-mEGFP were added to each well. The cells were incubated for an additional 3 h. After three rounds of washing with PBS, the fluorescence of the cells was analyzed using a flow cytometer (CytoFLEX, Beckman Colter).

Internalization pathway of LNPs

Dendritic cells (DC2.4 cell line) were plated in 96-well plates at a density of 105 cells per well 12 h prior to the experiment. The cells were pre-incubated with small molecule inhibitors for 15 min, including 5 μg/mL nocodazole, 10 μg/mL poly I, 10 μg/mL dynasore, 2.5 μg/mL cytochalasin D, 2.5 mg/mL MBCD, and 100 ng/mL wortmannin. Then, the supernatant was aspirated, washed twice with PBS, and SM102-LNP or CAS-LNP encapsulated with Cy5-mEGFP (equivalent to 100 ng mRNA per well) were added into each well of the cells. After 1.5 h incubation at 37 °C, the wells were washed 3 times with cold PBS and replaced with fresh media. The cellular uptake was determined by flow cytometry (CytoFLEX, Beckman Colter), and the mean fluorescence intensity of Cy5 was applied for quantification.

Hemolysis of RBCs

Mouse RBCs were isolated from mouse blood by centrifugation at 300 × g for 5 min. RBCs were then washed with PBS three times and suspended in PBS with a pH of 5.5 or 7.4. 150 µL of RBCs solution was added to each well of a 96-well plate. LNPs containing 200 ng of mRNA or 0.1% Triton-X100 or PBS were added to each well and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. The plate was centrifuged at 300 × g at 4 °C for 5 min. 100 µL aliquot from each well was transferred to a transparent 96-well plate. The absorbance at 540 nm of each well was measured using a microplate reader (Synergy H1, BioTek).

Evaluation of mRNA expression in different cell types in vivo

C57BL/6-Rosa26-CAG-LSL-tdTomato mice (GemPharmatech) were administered with mCre-encapsulating CAS-LNP through oropharyngeal aspiration of nebulized LNP or mCre-encapsulating IV-LNP through intravenous injection at days 0, 1, and 3. Each mouse received 5 µg of mCre per dose. On day 7, the lungs were harvested, minced into small pieces, and digested with collagenase type I at 37 °C for 40 min with gentle shaking. The dissociated tissues were filtered through a 70 µm basket filter and subsequently lysed by incubation with red blood cell lysis buffer (Solarbio) for 10 min. After centrifugation at 350 × g for 5 min, the cells were collected, washed with PBS, and resuspended in FACS buffer (1 × PBS with 2% FBS). To reduce nonspecific staining induced by Fc receptors, the cells were incubated with anti-mouse CD16/32 (BioLegend, Cat. 156603) for 10 min on ice. Subsequently, the cells were incubated with PE/Cyanine7 anti-mouse CD45 antibody (BioLegend, Cat. 103113), APC anti-mouse CD31 antibody (BioLegend, Cat. 160209), and FITC anti-mouse CD326 antibody (BioLegend, Cat. 118207) on ice for 20 min. For the detailed analysis of transfected immune cells in CAS-LNP treated mice, cells were stained with PE/Cyanine7 anti-mouse CD45 antibody, Alexa Flour 488 anti-mouse F4/80 antibody (BioLegend, Cat. 123120), APC anti-mouse CD11b antibody (BioLegend, Cat. 101211), Brilliant Violet 785 anti-mouse CD11c antibody (BioLegend, Cat. 117335) and Brilliant Violet 421 anti-mouse Ly−6G antibody (BioLegend, Cat. 127627) for one panel. The other panel was stained with PE/Cyanine7 anti-mouse CD45 antibody, FITC anti-mouse CD3 antibody (BioLegend, Cat. 100203), Brilliant Violet 421 anti-mouse NK-1.1 antibody (BioLegend, Cat. 108731) and Brilliant Violet 785 anti-mouse CD19 antibody (BioLegend, Cat. 115543). Following incubation, the cells were washed three times with 1 mL of FACS buffer before being analyzed using a flow cytometer (CytoFLEX LX, Beckman Colter).

Efficacy of inhaled CAS-LNP encapsulating Omicron mRNA vaccine

Female C57BL/6 mice (6–9 weeks) were randomly allocated to each group (five mice per group). Animals were immunized by oropharyngeal aspiration of nebulized SM102-LNP or CAS-LNP containing mCOVID at days 0, 14, and 28. Each mouse received 5 µg of mCOVID per dose. At day 35, the mice were euthanized. The serum, BALF (collected by lavage with 3 × 300 µL of PBS through a polyethylene tube cannulated into the trachea), and lungs were isolated for subsequent analysis.

The antigen-specific total IgG or IgA antibodies in serum and BALF were analyzed by ELISA. Briefly, a high-binding 96-well plate (Costar) was coated with 2 µg/mL of SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.529 S1 + S2 trimer protein (Sino Biological) in 100 µL of coating buffer (Dakewe) and incubated at 4 °C overnight. After aspiration, the wells were washed three times with wash buffer (Dakewe) and then blocked with 200 µL of blocking buffer (Dakewe) for 1 h at 37 °C. Following blocking, the plates were washed three times with wash buffer before adding 100 µL of diluted serum (1:10 in dilution buffer (Dakewe)) or BALF samples. The plates were then incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. After incubation, the plates were washed three times with wash buffer before adding 100 µL of anti-mouse IgA-HRP (1:4000 in dilution buffer, Southern Biotech, Cat. 1040-05) or anti-mouse IgG-HRP (0.08 µg/mL in dilution buffer, Acro, Cat. RAS060-C04). After incubation for 1 h at 37 °C, the plates were washed three times with wash buffer. Subsequently, 100 µL of 3,3’,5,5’-tetramethylbenzidine solution (Dakewe) was added to each well. After 15 min of incubation, 100 µL of stop solution (Dakewe) was added to stop the reaction. The absorbance of each well at 450 nm and 630 nm was recorded using a microplate reader (Synergy H1, BioTek). IgG titers were measured by a similar method with serially diluted serum. Endpoint titers were defined by the lowest dilution at which the optical density (OD) = 0.13.

The neutralizing ability of serum and BALF was measured using a pseudovirus neutralization assay. ACE2-expressing HEK-293T cells (Yeasen) were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% of FBS and 100 U/mL of penicillin-streptomycin. ACE2-expressing HEK-293T cells were seeded in a 96-well plate at a density of 1 × 104 cells per well. Diluted serum (1:15 in Opti-MEM (Gibco)) or BALF were mixed with SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.529 pseudovirus carrying a firefly luciferase reporter (Yeasen) at a titer of 2500 TU/mL. The mixture was incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. Next, the pre-seeded ACE2-expressing HEK-293T cells were exposed to 50 µL of the serum-virus or BALF-virus mixture and further incubated for 42 h. After incubation, firefly luciferase activity was measured by adding 100 µL of luciferase assay solution (One-Lite Luciferase Assay System, Vazyme). The bioluminescence was recorded using a microplate reader (Synergy H1, BioTek).

The cellular immune response in the lung was analyzed by ELISpot. The single-cell suspension of the lung was prepared first. ELISpot plates were precoated with IFN-γ-specific antibodies (MabTech, Cat. 3321-4AST-2). The plates were washed with PBS and blocked with culture medium (RPMI medium containing 10% FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 0.1 mM non-essential amino acids, 10 mM HEPES, and 50 mM β-mercaptoethanol) for 3 h. Then, 4 × 105 lung cells were added to each well and stimulated with a 2 mg/mL peptide pool of Omicron for 24 h. Spots were visualized with biotin-conjugated anti-IFN-γ antibody (MabTech) followed by incubation with streptavidin-alkaline phosphatase (MabTech) and BCIP/NBT substrate (MabTech). The number of spots per well was counted by eye using a microscope (Olympus CX43).

For flow cytometry analysis, single-cell suspensions from lung or BALF were incubated with anti-mouse CD16/32 for 10 min on ice. Subsequently, the cells were incubated with PerCP anti-mouse CD8a antibody (BioLegend, Cat. 100731), FITC anti-mouse CD44 antibody (BioLegend, Cat. 103005), PE anti-mouse CD69 antibody (BioLegend, Cat. 104507), and APC anti-mouse CD103 antibody (BioLegend, Cat. 121413) for the analysis of CD8 + TRM cells. For the analysis of CD4 + TRM cells, the following antibodies were used: PerCP anti-mouse CD4 antibody (BioLegend, Cat. 100537), FITC anti-mouse CD44 antibody, PE anti-mouse CD69 antibody, and APC anti-mouse CD11a/CD18 antibody (BioLegend, Cat. 141009). After staining, the cells were washed three times with 1 mL of FACS buffer by centrifugation at 350 × g × 5 min. Finally, the cells were resuspended in 0.5 mL of FACS buffer for analysis using a flow cytometer.

Efficacy of inhaled CAS-LNP encapsulating cancer mRNA vaccine

Female C57BL/6 mice (6-9 weeks) were randomly divided into three groups, with eight mice per group. The mice were immunized by oropharyngeal aspiration of nebulized SM102-LNP or CAS-LNP containing mOVA, or PBS at days 0, 7, and 14. Each administration of LNP contained 5 µg of mOVA per mouse. On day 13, the lung and spleen were harvested for the analysis of antigen-specific cytotoxic T cells. The OVA-specific, IFN-γ-producing CD8 + T cells in the lung were analyzed by flow cytometry. The single-cell suspension of the lung was prepared first and seeded at a density of 1.2 × 106 lung cells per well in a 48-well plate. The cells were stimulated for 6 h with 4 µg/mL SIINFEKL peptide (for restimulation of OVA-specific CD8 + T cell, GL Biochem) and 1 × protein transport inhibitor cocktail (eBioscience). Then, the cells were incubated with anti-mouse CD16/32 for 10 min on ice, followed by staining with PerCP anti-mouse CD8a antibody. After being fixed with fixation buffer (BioLegend) and permeabilized with intracellular staining perm wash buffer (BioLegend), the cells were further stained with APC anti-mouse IFN-γ antibody (BioLegend, Cat. 505809). Finally, the cells were washed and resuspended in 0.5 mL of FACS buffer for flow cytometry analysis.