Abstract

Background Sorafenib is a standard therapeutic agent for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). However, its efficacy is moderate, as the survival of patients is prolonged for only a few months, and the response rate is low. The mechanism of low efficacy remains unclear. In this study, we investigated the effect of Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3) on the effects of sorafenib on HCC. Methods Polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid [poly(I: C)] was used as a double-stranded RNA analog and TLR3 agonist in subsequent experiments. After orthotopic implantation of HCC tumors in BALBc nu/nu or C57BL/6 mice, survival time, tumor growth, and metastasis in the abdomen and lungs were analyzed. Flow cytometry and cytotoxicity assays were used to analyze NK cells isolated from the spleen or peripheral blood. ELISA was used to detect the expression of plasma interferon (IFN)-γ and monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP)-1. In addition, the expression of phosphorylated-extracellular regulated kinase 1/2 (pERK1/2), phosphorylated-protein kinase B (pAKT), ERK1/2 and AKT was analyzed by Western blotting. Results Sorafenib reduced the number and activity of NK cells in tumor-bearing mice and simultaneously decreased the levels of MCP-1 and IFN-γ in the plasma. The combination of sorafenib and poly(I: C) synergistically inhibited tumor growth and metastasis in tumor xenograft mice and prolonged survival. Poly(I: C) not only exerts a direct inhibitory effect on tumor growth and metastasis by targeting the TLR3 receptor on tumor cells but also facilitates the proliferation and activation of NK cells, indirectly impeding tumor progression. Mechanistically, poly(I: C) decreased the sorafenib-induced inhibition of ERK phosphorylation and increased the phosphorylation of IκB in NK cells, thereby enhancing NK cell function. Conclusion Activation of TLR3 can enhance the antitumor effect of sorafenib on HCC. The combination of a TLR3 activator and sorafenib may be a new strategy for the treatment of HCC.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-78316-3.

Keywords: TLR3, Sorafenib, Poly(I:C), Natural killer cell, Antitumor immunity

Subject terms: Metastasis, Drug discovery, Cancer, Cancer therapy, Cancer therapeutic resistance

Introduction

Sorafenib is an oral multikinase inhibitor that can inhibit BRAF kinase, vascular endothelial growth factor receptors 2 and 3, platelet-derived growth factor receptor, FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3), and c-KIT1. It is the first molecular-targeted agent to be clinically approved for the treatment of patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)2,3. Although the clinical application of sorafenib provides survival benefits, its efficacy is moderate, with patient survival prolonged for only a few months and a low response rate4,5. Notably, some preclinical studies have shown that administering sorafenib and sunitinib before tumor inoculation in mice accelerates the growth of metastatic tumors and reduces overall survival6. Similarly, our previous study revealed that sorafenib has a detrimental proinvasive effect on an orthotopic HCC model by downregulating the tumor suppressor gene HTATIP2, resulting in increased invasiveness and metastatic potential of HCC7. Some studies have shown that many targeted agents, in addition to inhibiting the signaling pathways of cancer cells, may also affect the host’s antitumor immunity. For example, sorafenib can inhibit T-cell proliferation and cytotoxicity in a dose-dependent manner by inducing apoptosis and targeting lymphocyte Cell-Specific Protein-Tyrosine Kinase (LCK) phosphorylation8. Additionally, sorafenib inhibits the maturation and function of dendritic cells (DCs)9. We also reported an increase in tumor growth and metastasis and a decrease in survival in a sorafenib-pretreated xenograft mouse model, which was attributed to the direct inhibition of natural killer (NK) cells by sorafenib10. These findings highlight the importance of exploring combination therapies to improve the efficacy of sorafenib for treating HCC.

Unlike T cells and B cells, NK cells can exert direct cytotoxic effects on tumor cells without prior sensitization and indirectly participate in eliminating tumor cells by secreting antitumor cytokines, thereby limiting the growth and dissemination of various tumor types11. Studies have shown that the frequency of spontaneous tumors induced by methylcholanthrene is greater in mice deficient in key effector molecules of NK cells or their respective receptors12. Currently, multiple methods to augment the cytotoxic activity of NK cells provide insights for novel immunotherapy regimens, such as the chemoattractant cytokine MCP-1, which suppresses tumor progression by enhancing the reactivity of NK cells13. Moreover, blocking the MHC class I-specific inhibitory receptor of NK cells increases the effector function of NK cells against tumor cells in mice14.

Toll-like receptors (TLRs), which are expressed in various immune cells and cancer cells, promote immune responses upon recognition of pathogen-associated molecular patterns15,16. Specifically, TLR3 recognizes endosomal double-stranded RNA (dsRNA)17and initiates signal transduction via the Toll/IL-1R domain-containing adaptor inducing IFN-β (TRIF)18. The TLR3/TRIF pathway also activates nuclear factor-kappaB (NF-κB) and induces the production of proinflammatory cytokines such as IFN-γ18. Polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid [poly(I: C)], a dsRNA analog and TLR3 agonist, induces strong antiviral and antitumor effects along with the activation of NK cells and CD8+T cells19. Notably, it has been found that NK cells are indirectly activated in response to poly(I: C). For example, the coculture of NK cells with DCs induces the production of IFN-γ both in vitro and in mice20. The ability of poly(I: C) to directly induce the expression of granzyme B or IFN-γ in NK cells has not been established.

In the present study, we hypothesized that the inhibition of NK cells accounts for the limited therapeutic effect of sorafenib and that the activation of TLR3 may modulate antitumor immunity. Our results showed that, compared with either agent alone, the combination of sorafenib and poly(I: C) inhibited tumor growth, reduced lung metastasis, and prolonged host survival. Poly(I: C) alleviated the inhibitory effect of sorafenib on the reactivity of NK cells in tumor-bearing mice. Furthermore, we found that the activation of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) and IκB phosphorylation signaling pathways contributed to the activation of NK cells in response to poly(I: C) stimulation in vitro. These results lay the foundation for a potent clinical application of the combination of sorafenib and poly(I: C) in the treatment of HCC.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and animals

The human cell line HepG2 and the mouse cell lines Hepa1-6 and YAC-1 were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection; the human cell line HCC-LM3was established at Fudan University21. Stable red fluorescent protein (RFP)-expressing LM3 (RFP-LM3) cells derived from HCC-LM3cells were kindly provided by Professor WZ Wu22 and were used for in vivo experiments. These cells were maintained at 37 °C with 5% CO2 in an air atmosphere in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) or RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) and antibiotics (100 U/mL penicillin and 100 mg/mL streptomycin).

Male BALB/c nu/nu mice and male C57BL/6 mice aged 4 to 6 weeks and weighing 20 g were obtained from the Shanghai Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Science, and were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions. In this study, the mice were euthanized with carbon dioxide.

This study was approved by the Qilu Hospital of Shandong University, and informed consent was obtained from the subjects. The animal experiments in this study were approved by the ethics committee of the hospital and strictly followed the operating standards of animal experiments.

Isolation of NK cells

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated from healthy volunteers by density gradient centrifugation, and NK cells were isolated by MACS (Miltenyi Biotec). The purity of the NK cells was detected by flow cytometry. NK cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 with 10% FBS (containing 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 U/mL streptomycin, and 1000 U/mL IL-2). NK cells were inoculated in culture flasks at a density of 2 × 105/cm2 and placed in a 37 °C culture chamber with 5% CO2. NK cells were isolated from murine spleens by negative selection with the NK Cell Isolation Kit and MACS columns and cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS. Experiments were performed when the purity of the mouse NK1.1+ NK cells was greater than 90%.

Reagents

Sorafenib (Bayer Healthcare, Inc.) was suspended in a vehicle solution containing Cremophor (Sigma), 95% ethanol, and deionized water at a ratio of 1:1:6. Poly (I: C) was purchased from InvivoGen (San Diego, CA). Recombinant human IL-2 (specific activity > 107 units/mg) was purchased from Peprotech (USA). Bay11-7082 (an NF-κB-specific inhibitor) was purchased from Sigma and was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) for further experiments.

Cell proliferation and invasion assays

LM3 cells were incubated in 96-well plates (5 × 103 cells/well) for 24, 48, or 72 h. Proliferation was measured at different times using the MTT method (Dojin Laboratories, Kumamoto, Japan). Cell migration was assessed by a Transwell assay (Boyden Chambers, Corning, Cambridge, MA). Briefly, 10 µL of Matrigel (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, New NJ) was added to each well of a 24-well plate, and after 6 h, 5 × 104 cells in serum-free DMEM were seeded on the membrane (8.0 μm pores). DMEM containing 10% FBS was added to the lower chamber of each well. After 48 h, the cells that had reached the underside of the membrane were stained with Giemsa (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO) and counted at ×200 magnification.

HCC animal models and treatment

For orthotopic HCC tumors in animal models, tumor cells were subcutaneously inoculated into the right flank of 4-week-old male BALBc nu/nu or C57BL/6 mice. After 3 to 4 weeks, nonnecrotic tumor tissues were cut into 1 mm × 1 mm pieces and orthotopically implanted into the liver. For experimental lung metastases of cancer cells, viable tumor cells were suspended in 200 µL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and injected into the lateral tail vein of nude mice.

The mice were randomized into four groups (n = 5 or 6 in each group) according to body weight for the following treatments: vehicle control, sorafenib (60 mg/kg/d, oral gavage, twice a day), poly(I: C) (5 mg/kg/d, intraperitoneally, every other day), and sorafenib plus poly(I: C). To evaluate the function of NK cells in vivo, human NK cells were injected into the lateral tail vein of nude mice biweekly for 4 consecutive weeks after inoculation.

The tumors were excised, and the maximum (a) and minimum (b) diameters were measured to calculate the tumor volume: V = ab2/2. Fluorescent protein–positive (GFP+ or RFP+) metastatic foci were imaged (stereomicroscope: Leica MZ6; illumination: Leica L5FL; C-mount: 0.63/1.25; charge-coupled device: DFC 300FX), and the number and area of metastatic foci were quantified by Image-Pro Plus software (Media Cybernetics, Bethesda, MD)22.

For the tail vein metastasis models of BALBc nu/nu mice, 1 × 106 HCC cells were injected into the mice, and then, the sorted human NK cells were injected into the mice biweekly for 5 consecutive weeks after inoculation.

Flow cytometry analysis of NK cells

Spleen or peripheral blood mononuclear cells were washed once with PBS supplemented with 2% FBS and 0.05% sodium azide (2% FBS-PBS). The washed cells were incubated at 4 °C for 30 min in 2% FBS-PBS supplemented with anti-mouse CD3, NK1.1, CD49b and CD69 antibodies (BD PharmingenTM, USA) or with normal mouse serum as a negative control. The samples were then washed twice with 2% FBS-PBS. The fluorescence intensities were measured by a FACScan (BD Biosciences).

Cytotoxicity assay of NK cells

Isolated murine NK cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with sorafenib or poly(I: C). Cytotoxicity was determined by a lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release assay as previously described23. YAC-1 or Hepa1-6 cells were used as targets to evaluate NK activity. In all the experiments, spontaneous release was less than 15% of the maximum release. In brief, these effector (E) and target (T) cells were plated in 96-well round-bottom plates at appropriate E: T ratios. After 4 h of incubation, LDH in the medium was measured with the nonradioactive Cytotoxicity Detection KitPLUS (LDH) (Roche). Determinations were carried out in triplicate. The percentage of specific cytolysis was calculated from the release of LDH in the test samples and control samples as follows:

|

ELISA of plasma proteins

The levels of plasma IFN-γ and MCP-1 were analyzed by ELISA with Quantikine ELISA kits (R&D Systems). All analyses were carried out in duplicate.

Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis of whole-cell extracts was performed essentially as described previously24. The primary antibodies used included anti-pERK1/2, anti- phosphorylated-protein kinase B (pAKT) (Cell Signaling Technology; Danvers, MA, USA), anti-ERK1/2, and anti-AKT (Abcam; Cambridge, MA, USA) antibodies.

Statistical analysis

Continuous data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. Comparisons were made using independent two-tailed Student’s t test, one-way ANOVA, or the Mann-Whitney U test. All the statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 16.0 (SPSS; Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

TLR3 mediates the synergistic inhibitory effect of sorafenib and poly(I: C) on liver cancer cells in vitro

First, we evaluated the expression of TLR3 in various HCC cell lines and tissues from HCC patients and found that its expression in LM3 and MHCC-97 H liver cancer cells was significantly greater than that in other cell lines (Figure S1A) or in tumor tissues from HCC patients (Figure S2). To further determine the biological significance of TLR3 in NK cells, three shRNA interference sequences were established(Table S1) and was selected an shRNA with high knockdown efficiency. We generated stable TLR3-knockdown LM3 cells to investigate the effect of TLR3 on the function of poly(I: C). Western blot analysis and qPCR confirmed that the expression level of TLR3 in stable TLR3-knockdown LM3 and HepG2 cells was lower than that in parental cells (Figure S1B).

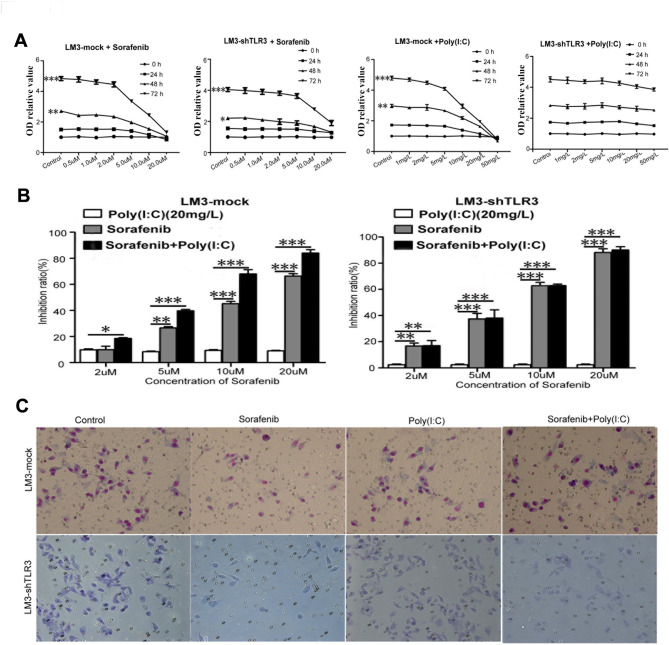

Next, we tested the direct cytotoxic effects of sorafenib and poly (I: C) on LM3-Mock and LM3-shTLR3 cells in vitro at different time points and concentrations. The results showed that sorafenib inhibited the proliferation of both cell types in a dose-dependent manner at a minimal concentration of 5 µM, and the inhibitory effect was more obvious at 72 h (Fig. 1A). Meanwhile, poly(I: C) inhibited the proliferation of LM3-Mock cells in a concentration- and time-dependent manner. In contrast, poly(I: C) did not inhibit the proliferation of LM3-shTLR3 cells. We selected 20 mg/L poly(I: C) to investigate its synergistic effect with sorafenib on LM3-Mock and LM3-shTLR3 cells, respectively. The results showed that with increasing sorafenib concentration, the combination of sorafenib and poly(I: C) synergistically inhibited the growth of LM3-Mock cells but not LM3-shTLR3 cells (Fig. 1B). These results suggest that TLR3 can mediate the direct inhibitory effect of poly(I: C) on tumor cells and that poly(I: C) and sorafenib synergistically inhibit the proliferation of liver cancer cells in vitro.

Fig. 1.

Poly(I: C) increased the inhibitory effect of sorafenib on liver cancer cellsin vitro. (A) Sorafenib inhibited the proliferation of LM3-Mock and LM3-shTLR3 cells in a dose-dependent manner. LM3-Mock and LM3-shTLR3 cells were treated with sorafenib alone or in combination with different concentrations of poly(I: C). We used OD relative value to represent cytotoxic effect, as follows: OD relative value = Cell OD value/0 h OD value of control group.The data from three experiments are presented as means ± SDs. (B) The combination of sorafenib and poly(I: C)(20 mg/L)synergistically inhibited the growth of LM3-Mock cells but not LM3-shTLR3 cells. (C)Sorafenib significantly limited the invasion of LM3-Mock and LM3-shTLR3 cells at a concentration of 10 µM, as measured by a transwell assay. These representative photos were taken 6 h after treatment.

We further investigated the effect of sorafenib on cell invasion and found that sorafenib significantly inhibited the invasion of both LM3-Mock and LM3-shTLR3 cells at a dose of 10 µM (Fig. 1C). We also observed that the inhibitory effect of poly(I: C) on the invasion of LM3-Mock cells was stronger than that on the invasion of LM3-shTLR3 cells. The combination of poly(I: C) and sorafenib also synergistically inhibited the invasion of LM3-Mock cells but not LM3-shTLR3 cells (Fig. 1C). These results further demonstrate that TLR3 can mediate the direct effect of poly(I: C) on tumor cells and that poly(I: C) and sorafenib synergistically inhibit the invasion of liver cancer cells in vitro.

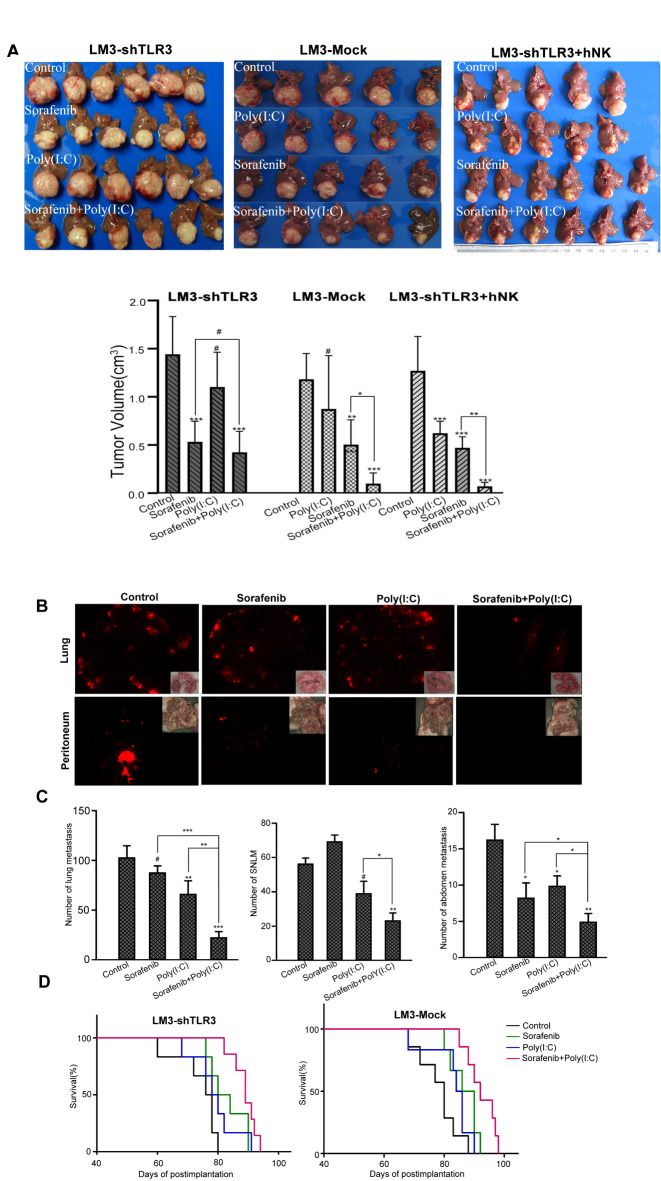

The combination of sorafenib with poly(I: C) has a synergistic inhibitory effect on tumor growth in TLR3-knockdown cells in vivo

We established xenograft tumor models using LM3-Mock cells and LM3-shTLR3 cells. After 4 weeks of treatment, sorafenib significantly reduced the tumor volume compared to the control treatment in the LM3-Mock cell xenograft model (0.51 ± 0.25 cm3versus 1.18 ± 0.27 cm3, P < 0.001) (Fig. 2A) and in the LM3-shTLR3 model (0.53 ± 0.21 cm3versus 1.44 ± 0.36 cm3, P < 0.001) (Fig. 2B). Although there was no significant difference in tumor volume between the poly(I: C) treatment group and the control treatment group in the LM3-Mock model (P = 0.16), the combination of poly(I: C) and sorafenib significantly reduced the tumor volume in the LM3-Mock xenograft tumors compared with sorafenib alone (P < 0.05). Compared with the control, sorafenib inhibited tumor growth, whereas poly(I: C) did not significantly inhibit tumor growth in the LM3-shTLR3 xenograft model. However, the difference between the combination group and the sorafenib group was not significant in the LM3-shTLR3 xenograft tumor(0.42 ± 0.21 cm3versus 0.53 ± 0.21 cm3, P > 0.05) (Fig. 2B). To investigate the effects of NK cells on HCC growth and metastasis in vivo, the LM3-shTLR3 model was intravenously injected with human NK cells biweekly for four weeks. Compared with the control, poly(I: C) significantly inhibited tumor growth in the LM3-shTLR3 xenograft model without human NK cells. The tumor size was significantly smaller in the mice treated with the combination of poly(I: C) and sorafenib than in those treated with sorafenib alone(0.07 ± 0.02 cm3versus 0.47 ± 0.11 cm3, P < 0.001). These results indicate that poly(I: C) may enhance the ability of NK cells to inhibit tumor growth and that TLR3 directly and indirectly mediates the inhibitory effect of poly(I: C) on liver cancer cells.

Fig. 2.

Poly(I: C) increased the antitumor activity of sorafenib and prolonged the survival of the host. (A) Sorafenib significantly reduced the tumor volume, and poly(I: C) enhanced this effect in the LM3-Mock model but not in the LM3-shTLR3 model. However, when treated with human NK cells, poly(I: C) significantly enhanced the inhibitory effect of sorafenib in the LM3-shTLR3 model. These representative photos are shown. (B) Sorafenib reduced the number of lung and abdominal metastases but increased the standardized number of lung metastases (SNLM) in the liver cancer cell metastasis model. Representative images were taken at the end of the experiment. (C) Numbers of lung and abdominal metastases in five mice in different groups are presented as means ± SDs. (D) The combination of poly(I: C) and sorafenib prolonged the survival of tumor-bearing mice (#P > 0.05, *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001).

We also observed the effect of the combination of sorafenib and poly(I: C) on the number of metastases in the LM3-Mock xenograft model. Sorafenib alone significantly reduced the number of lung metastases (89 ± 11 versus 112 ± 10 per lung, P < 0.01). However, when the number of metastases was standardized by the size of the liver tumors, sorafenib significantly increased the standardized number of lung metastases (SNLM) compared with the control treatment (67 ± 7 versus 52 ± 4 per lung, P< 0.05), as we previously reported7. Compared with the control treatment, poly(I: C) treatment alone also did not reduce SNLM (P = 0.41). However, the combination of poly(I: C) and sorafenib reduced both the number of lung metastases (21 ± 6 versus 80 ± 12 per lung, P < 0.001) and SNLM (32 ± 7 versus 68 ± 7 per lung, P < 0.05) compared with sorafenib or poly(I: C) alone. Notably, when sorafenib was administered in combination with poly(I: C), its potential antimetastatic effect was abolished (SNLM: 32 ± 7 in the combination group versus 51 ± 4 in the control group, P < 0.01; Fig. 2B). The synergistic inhibitory effect of the drugs on abdominal metastases was similar to that observed in the lungs of mice receiving combination therapy (combination group 5 ± 2 versus sorafenib group 10 ± 3, P < 0.05; Fig. 2C). These results further indicate that the combination of sorafenib and poly(I: C) has a synergistic inhibitory effect on liver cancer in vivo.

Furthermore, although poly(I: C) alone did not prolong the survival of tumor-bearing mice, combination therapy significantly prolonged the overall survival of both LM3-Mock (88.0 ± 1.6 versus 81.7 ± 2.3, P < 0.05) and LM3-shTLR3 (93.3 ± 1.7 versus 85.7 ± 2.0, P < 0.05) xenograft models compared with sorafenib alone (Fig. 2D).

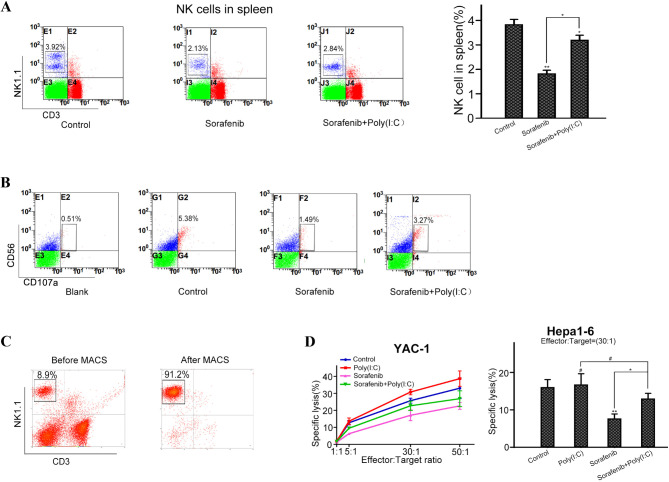

Poly(I: C) attenuates the inhibitory effect of sorafenib on NK cells in vivo

Because the TLR3 agonist poly(I: C) is a dsRNA analog that can induce a strong antineoplastic effect accompanied by the activation of NK cells19, we next evaluated whether poly(I: C)-mediated NK cells could activate the antitumor activity of combination therapy. Previous studies have shown that sorafenib inhibits the reactivity of NK cells against tumor cells both in vitro and in vivo25. We also found that, compared with control treatment, sorafenib treatment alone decreased the number of splenic NK cells in tumor-bearing C57B6 mice (3.26 ± 0.31% versus 2.24 ± 0.96%, P < 0.01). However, compared with sorafenib alone, the combination of sorafenib and poly(I: C) significantly increased the number of NK cells in tumor-bearing C57B6 mice (P < 0.05; Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

Poly(I: C) attenuated sorafenib-mediated suppression of NK cells in tumor-bearing C57BL/6 mice. (A) Percentages of CD3− and NK1.1+ NK cells in the spleen and peripheral blood were measured by flow cytometry. The data from five mice are presented as means± SDs. (B) Representative flow cytometry dot plots of NK cells in the spleen and peripheral blood of each group. (C) Percentages of CD3− and NK1.1+ NK cells in the spleen before and after magnetic-activated cell sorting. (D) The specific lysis of YAC-1 and Hepa1-6 cells by NK cells isolated from different groups (#P > 0.05, *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001).

Furthermore, we performed degranulation assays in cocultures of isolated human NK and K562 cells. Similar to our previous results, sorafenib significantly reduced the expression of CD107a in NK cells in the presence of K562 cells. Compared with sorafenib treatment alone, combination treatment with sorafenib and poly(I: C) upregulated the expression of CD107a (Fig. 3B).

Next, we determined the cytotoxicity of NK cells isolated from tumor-bearing C57BL/6 mice in different treatment groups. First, we isolated NK cells from the spleen by magnetic-activated cell sorting (purity > 90%; Fig. 3C) and determined the reactivity of the NK cells. We found that the number of splenic NK activity cells in the sorafenib-treated mice was significantly lower than that in the control group, whereas the number of splenic NK activity cells in the combination treatment group was partially restored compared with that in the sorafenib-treated group (P < 0.05; Fig. 3D). Our results indicate that poly(I: C) protects NK cells from impairment by sorafenib to a certain extent.

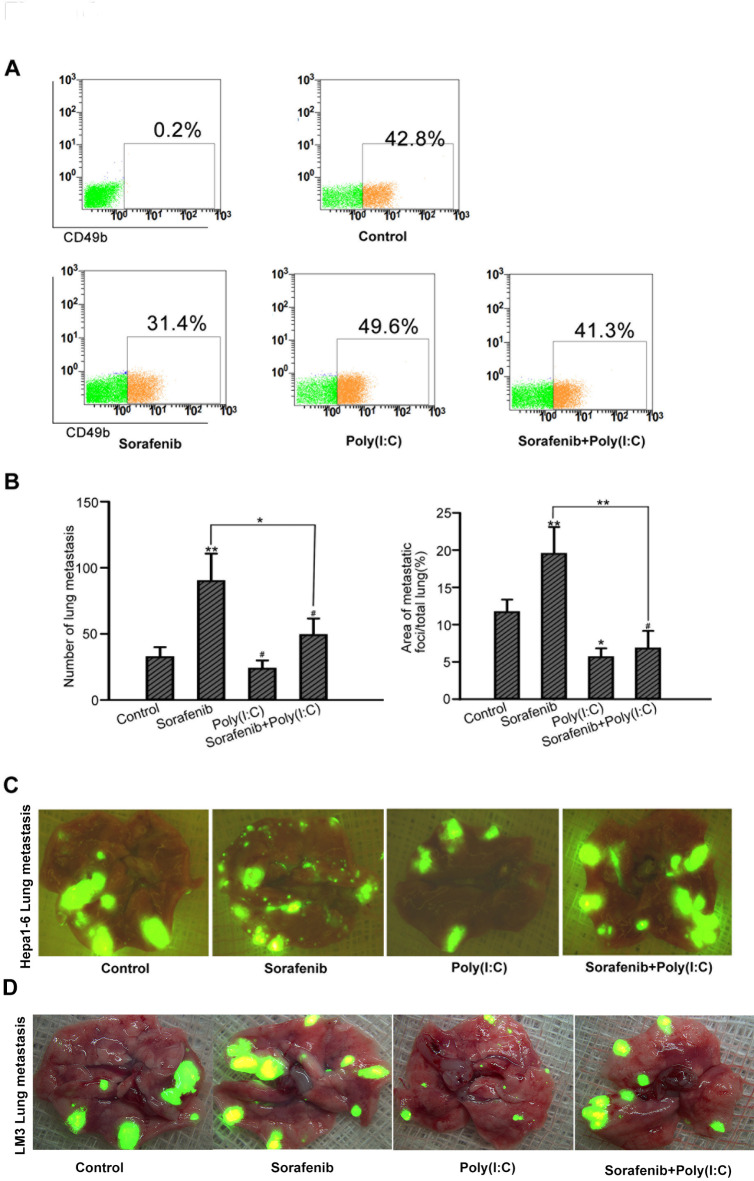

To verify the protective effect of poly(I: C) on NK cells, we used a unique model and administered the two agents separately or in combination before tumor implantation in nude mice. We found that the number of CD49b+ NK cells in sorafenib-treated nude mice was lower than that in control mice, but the difference was not significant in combination-treated mice (Fig. 4A). Consistent with our hypothesis, more lung metastases were found in sorafenib-pretreated mice than in control mice according to the number of tumors (87.1 ± 22.1 versus 46.3 ± 12.3 per lung, P < 0.05) or area (15.1 ± 5.0% versus 9.6 ± 2.1%, P < 0.05). Interestingly, we observed no significant difference in the number of metastases between poly(I: C)-pretreated and vehicle-pretreated mice (42.0 ± 15.6 versus 45.5 ± 12.1 per lung, P = 0.643). However, in terms of area [7], there were significantly fewer lung metastases in poly(I: C)-pretreated mice than in control mice (4.2 ± 2.9% versus 11.2 ± 2.9%, P < 0.05), which might be attributed to the increased reactivity of NK cells induced by poly(I: C). Compared with the control mice, the combination-pretreated mice presented significantly fewer lung metastases (48.5 ± 20.1 versus 86.3 ± 21.6 per lung, P < 0.05), although the difference was not significant (P > 0.05) (Fig. 4B and C), suggesting that poly(I: C) protects NK cells to some extent in vivo.

Fig. 4.

Poly(I: C) reduced lung metastasis in sorafenib-pretreated nude mice. (A) Poly(I: C) enhances sorafenib-induced inhibition of NK cells in mice. The percentage of CD49b+ NK cells in the peripheral blood of nude mice was measured by flow cytometry. The data from five mice are presented as means± SDs. (B) Poly(I: C) enhances the sorafenib-mediated inhibition of NK cells in mice. The number and area of lung metastases in different groups are shown. (C) Representative images of GFP+ lung metastases taken by fluorescence microscopy (#P > 0.05; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001).

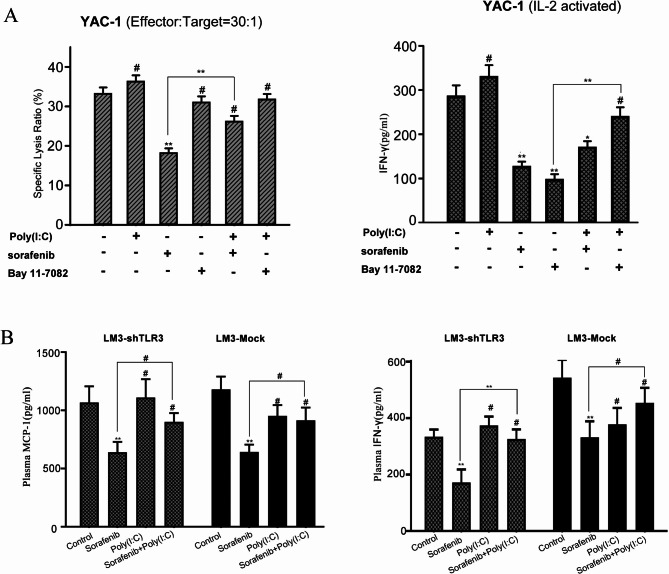

Direct activation of NK cells by poly(I: C) facilitates their antitumor activity

We also investigated whether sorafenib or poly(I: C) directly affects the activity of splenic NK cells from C57BL/6 mice. Compared with the control treatment, sorafenib treatment significantly reduced the cytotoxicity of NK cells to YAC-1 cells, whereas poly(I: C) marginally enhanced the activity of NK cells; the difference was not statistically significant (Fig. 5A). However, compared with sorafenib alone, the combination of sorafenib and poly(I: C) significantly increased the activity of NK cells. Bay 11-7082, an NF-κB-specific inhibitor, alone or in combination with poly(I: C), showed a modest effect on NK cell activity compared with the control, indicating that poly(I: C) enhances the function of NK cells through the rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma (Raf)/mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MEK)/ERK pathway rather than the NF-κB pathway. Notably, both sorafenib and Bay 11-7082 drastically impaired the production of IFN-γ. In contrast, poly(I: C) significantly upregulated the production of IFN-γ by NK cells when it was combined with Bay 11-7082, indicating that NF-κB pathways is involved in the increase in IFN-γ production. Because IFN-γ and MCP-1 are important cytokines of NK cells, we examined their expression levels in plasma by ELISA in the LM3-Mock and LM3-shTLR3 models. Compared with that in vehicle-treated mice, the level of MCP-1 in sorafenib-treated mice decreased by 42.1% in the LM3-Mock model (P < 0.05) and by 39.2% in the LM3-shTLR3 model (P < 0.05). In both models, the plasma IFN-γ level in the sorafenib-treated group was also lower than that in the vehicle-treated group (P < 0.05). In the LM3-Mock model, the plasma MCP-1 level in the combination-treated mice was significantly greater than that in the sorafenib-treated mice (P < 0.05), whereas the difference was not significant (P = 0.35) in the LM3-shTLR3 model (Fig. 5B). These results indicate that the immune-enhancing activity of poly(I: C) on NK cells contributes to the improvement in antitumor efficacy when poly(I: C) is combined with sorafenib.

Fig. 5.

Poly(I: C) directly protects NK cells from impairment by sorafenib. (A) The cytotoxicity of NK cells to YAC-1 cells was measured, and the production of IFN-γ in the presence of sorafenib, poly(I: C), or Bay 11-7028 was measured in vitro. The data from three independent experiments are presented as means ± SDs. (B) Plasma levels of INF-γ and MCP-1 in different groups of LM3-Mock and LM3-shTLR3 model mice were measured by ELISA. The data from three independent experiments are presented as means ± SDs. (#P > 0.05; *P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001).

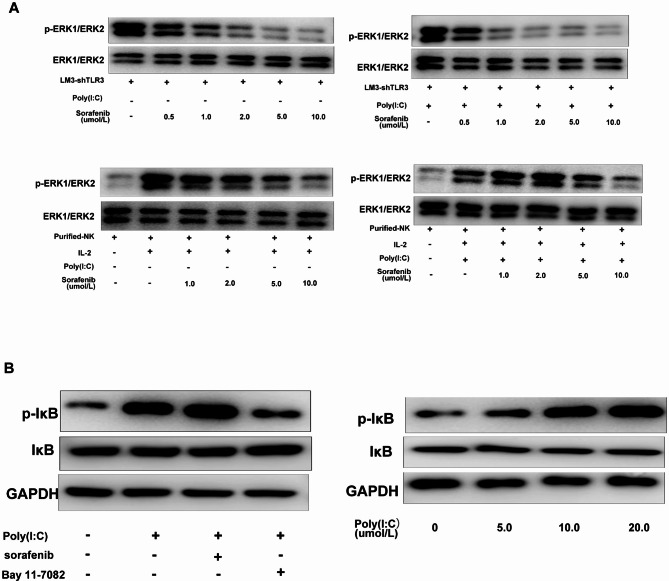

The ERK and NF-κB pathways are involved in the poly(I: C)-induced activation of NK cells

As previously reported by us, sorafenib primarily impairs the reactivity of NK cells by inhibiting the ERK signaling pathway10 rather than the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT or Janus kinase (JAK)/signal transducer and activator of transcription 3(STAT3) pathway. Thus, we examined the signaling molecules involved in this impairment by Western blot analysis and investigated the activation of NF-κB and ERK.

Compared with sorafenib alone, sorafenib inhibited ERK1/2 phosphorylation in LM3-shTLR3 cells in a dose-dependent manner. However, the level of ERK1/2 phosphorylation did not significantly differ between the combination group and the sorafenib alone group, indicating that poly(I: C) does not affect the level of phosphorylated ERK in LM3-shTLR3 cells by the synergistic effect of sorafenib. Isolated human NK cells were treated with sorafenib and/or poly(I: C) followed by IL-2. Subsequently, the cell lysates were analyzed for phosphorylated ERK (pERK1/2) and IκB. The addition of 2 µM sorafenib alone reversed IL-2-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation and almost completely eliminated the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 at 10 µM.

The level of ERK1/2 phosphorylation was reduced in NK cells when poly(I: C) was combined with sorafenib at a concentration of 20 µM. This suggests that poly(I: C) might protect against the damage to NK cell function caused by sorafenib through the upregulation of ERK1/2 phosphorylation (Fig. 6A). Poly(I: C) alone or in combination with sorafenib could increase the level of Iκβ phosphorylation in human NK cells and reverse the downregulation of Iκβphosphorylation in NK cells induced by an NF-κB-specific inhibitor (Bay 11-7082) to a certain extent. Moreover, poly(I: C) induced considerable Iκβ phosphorylation in isolated human NK cells in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 6B). Collectively, these findings suggest that NF-κB signaling pathways are also associated with the activation of poly(I: C)-stimulated NK cells.

Fig. 6.

The ERK and NF-κB pathways are involved in the poly(I: C)-induced activation of NK cells. Poly(I: C) attenuated sorafenib-mediated inhibition of ERK1/2 phosphorylation in liver cancer cells (A) and isolated NK cells (B). Liver cancer LM3-shTLR3 cells (A) or isolated NK cells (B) were treated with sorafenib (10 µM) without or with poly(I: C) for 24 h. ERK1/2 phosphorylation was determined by Western blotting. Representative images are shown. (C) Sorafenib did not significantly affect poly(I: C)-induced IκB phosphorylation in isolated human NK cells treated with poly(I: C) with or without sorafenib (10 µM) for 24 h. IκB phosphorylation was determined by Western blotting.

Discussion

HCC is one of the most common cancers worldwide with a high mortality rate. Unfortunately, most HCC patients are diagnosed at advanced stages, resulting in a poor prognosis and ineffective treatment26. However, despite rapid developments in surgical techniques, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy, the overall 5-year survival rate of patients with HCC remains unsatisfactory because of the recurrence and metastasis characteristics of HCC and resistance to antitumor drugs27,28. Sorafenib has been widely used in standard systemic treatment for advanced HCC. Unfortunately, sorafenib may have “off-target” harmful effects on immune cells, including T cells, NK cells, and DCs29. Our previous study reported that sorafenib at pharmacological concentrations inhibited NK cell activity in vitro due to impaired ERK phosphorylation, suggesting that the efficacy of sorafenib may be improved if NK cells are activated during HCC treatment. Sorafenib can inhibit the function of DCs, which is characterized by reduced secretion of cytokines and expression of CD1a, major histocompatibility complex, and costimulatory molecules in response to TLR ligands9. In this study, we emphasized the effect of TLR3 in NK cells on sorafenib-based HCC treatment. Specifically, the results showed that the activation of TLR3 enhances the antitumor effects of sorafenib by directly modulating the cytotoxicity of NK cells through the ERK1/2 and NF-κB pathways (a schematic summary is shown in Figure S3).

Poly(I: C) is an agonist of TLR3 and is a promising cancer vaccine adjuvant because it can induce a strong antitumor response, mainly by activating NK cells. Since TLR3 can be expressed by both immune system cells and cancer cells, TLR3 agonists may alleviate sorafenib-induced immunosuppression of NK cells and thereby enhance their therapeutic effect. Previous studies have reported that TLR3 agonists inhibit the proliferation and induce the apoptosis of HepG2cells overexpressing TLR330. Our results revealed that the combination of poly(I: C) and sorafenib did not influence the growth or invasiveness of HCC cells without TLR3 receptors. However, in the orthotopic HCC model, the sorafenib/poly(I: C) combination was superior to sorafenib or poly(I: C) alone in terms of the effects on tumor growth and metastasis, suggesting that poly(I: C) may have indirect antitumor activity. Poly(I: C) is presumed to be an effective agent, as it can regulate the immune response during tumor growth in tumor-bearing animals.

Our results showed that, compared with sorafenib (60 mg/kg/ day) alone, the poly(I: C)/sorafenib combination significantly inhibited tumor growth, reduced lung metastases, and prolonged host survival while increasing the number and reactivity of NK cells. In addition, the percentage of activated CD107a+NK cells was significantly decreased by sorafenib but was significantly increased by the poly(I: C)/sorafenib combination, suggesting that TLR3 activation may protect NK cells from collateral damage caused by sorafenib in vivo. However, there are still some limitations in our study, such as the lack of different doses of sorafenib or the sham operation group in NK cell transfer experiments, which has been discussed in the previous studies31–33.

TLR3 induces the production of ERK and NF-κB-dependent cytokines and cytotoxic molecules in NK cells34,35. The results of our previous study showed that sorafenib reduces the reactivity of NK cells primarily by inhibiting ERK signaling10. We further investigated the mechanism of the effect of poly(I: C) on NK cell cytotoxicity and IFN-γ production through the ERK and NF-κB pathways and found that the NK cell response increased when TLR3 activation was induced. Sorafenib alone reduced ERK1/2 phosphorylation, whereas the combination of poly(I: C)/sorafenib attenuated this effect in NK cells. Moreover, poly(I: C) induced IκB phosphorylation in human NK cells, although the phosphorylation level was not influenced by sorafenib. In this study, we elucidated that poly(I: C) can activate NK cells through the ERK and IκB phosphorylation signaling pathways in vitro. However, other in vitro studies have shown that purified mouse NK cells cannot be directly activated by poly(I: C) and that IFN-γ is produced through coculture of NK cells and DCs19. Thus, the TLR3 signaling pathway may stimulate DCs or macrophages to prime NK cells in mice. In turn, NK cells regulate the functions of DCs, as well as T-cell responses. Further studies are needed to investigate the underlying mechanism of poly(I: C) in restoring sorafenib-impaired NK cells in vivo. In conclusion, our results showed for the first time that the activation of TLR3 alleviated the sorafenib-mediated inhibition of NK cell function through the ERK and NF-κB signaling pathways.

Conclusions

In summary, the antitumor effect of sorafenib on HCC is weakened because of its ability to reduce the number and reactivity of NK cells, suggesting that the inhibition of NK cells may be a critical reason for the decreased efficacy of sorafenib-based HCC treatment. Our study shows that the combination of the TLR3 agonist poly(I: C) and sorafenib can synergistically inhibit tumor progression and prolong host survival and may be a promising combination therapy for HCC.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the supports from the colleague in Department of General Surgery, Qilu Hospital, Shandong University.

Abbreviations

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- NK

natural killer

- TLR

Toll-like receptor

- poly(I

C): polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid

- IFN-γ

interferon-γ

- MCP-1

monocyte chemoattractant protein 1

- RFP

red fluorescent protein

- DC

dendritic cell

- LDH

lactate dehydrogenase

- SNLM

standardized number of lung metastases

- shRNA

short hairpin RNA

- TRIF

Toll/IL-1R domain-containing adaptor inducing IFN-β

- dsRNA

double-stranded RNA

Author contributions

EYL conceived and designed the study. Experiments were performed by QBZ, HW, FX, YS, and RDJ. Data were analyzed by RDJ, QL and QBZ. QBZ wrote the main manuscript text. QBZ, HW, FX, YS prepared figures. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81401972) and the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (No. ZR2020MH253).

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The project design was conducted in line with scientific and ethical principles. The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All animal experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations, and the ethical and animal committee and institutional review board of Qilu Hospital, Shandong University approved this project.

Consent for publication

“Not applicable” in this section.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Wilhelm, S. M. et al. BAY 43-9006 exhibits broad spectrum oral antitumor activity and targets the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway and receptor tyrosine kinases involved in tumor progression and angiogenesis. Cancer Res.64, 7099–7109. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1443 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson, P. & Billingham, L. Sorafenib for liver cancer: the horizon broadens. Lancet Oncol.10, 4–5. 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70317-6 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palmer, H. D. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl. J. Med.359, 2498 (2008). author reply 2498–2499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheng, A. L. et al. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients in the Asia-Pacific region with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase III randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol.10, 25–34. 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70285-7 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Llovet, J. M. et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl. J. Med.359, 378–390. 10.1056/NEJMoa0708857 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ebos, J. M. et al. Accelerated metastasis after short-term treatment with a potent inhibitor of tumor angiogenesis. Cancer Cell.15, 232–239. 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.01.021 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang, W. et al. Sorafenib down-regulates expression of HTATIP2 to promote invasiveness and metastasis of orthotopic hepatocellular carcinoma tumors in mice. Gastroenterology143, 1641–1649 e1645, doi: (2012). 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.08.032 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Zhao, W., Gu, Y. H., Song, R., Qu, B. Q. & Xu, Q. Sorafenib inhibits activation of human peripheral blood T cells by targeting LCK phosphorylation. Leukemia. 22, 1226–1233. 10.1038/leu.2008.58 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hipp, M. M. et al. Sorafenib, but not sunitinib, affects function of dendritic cells and induction of primary immune responses. Blood. 111, 5610–5620. 10.1182/blood-2007-02-075945 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang, Q. B. et al. Suppression of natural killer cells by sorafenib contributes to prometastatic effects in hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS One. 8, e55945. 10.1371/journal.pone.0055945 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vivier, E., Tomasello, E., Baratin, M., Walzer, T. & Ugolini, S. Functions of natural killer cells. Nat. Immunol.9, 503–510. 10.1038/ni1582 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shankaran, V. et al. IFNgamma and lymphocytes prevent primary tumour development and shape tumour immunogenicity. Nature. 410, 1107–1111. 10.1038/35074122 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nokihara, H. et al. Natural killer cell-dependent suppression of systemic spread of human lung adenocarcinoma cells by monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 gene transfection in severe combined immunodeficient mice. Cancer Res.60, 7002–7007 (2000). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koh, C. Y. et al. Augmentation of antitumor effects by NK cell inhibitory receptor blockade in vitro and in vivo. Blood. 97, 3132–3137. 10.1182/blood.v97.10.3132 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jego, G., Bataille, R., Geffroy-Luseau, A., Descamps, G. & Pellat-Deceunynck, C. Pathogen-associated molecular patterns are growth and survival factors for human myeloma cells through toll-like receptors. Leukemia. 20, 1130–1137. 10.1038/sj.leu.2404226 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kawai, T. & Akira, S. TLR signaling. Semin Immunol.19, 24–32. 10.1016/j.smim.2006.12.004 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matsumoto, M. & Seya, T. TLR3: interferon induction by double-stranded RNA including poly(I:C). Adv. Drug Deliv Rev.60, 805–812. 10.1016/j.addr.2007.11.005 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamamoto, M. et al. Role of adaptor TRIF in the MyD88-independent toll-like receptor signaling pathway. Science. 301, 640–643. 10.1126/science.1087262 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Akazawa, T. et al. Antitumor NK activation induced by the toll-like receptor 3-TICAM-1 (TRIF) pathway in myeloid dendritic cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 104, 252–257. 10.1073/pnas.0605978104 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miyake, T. et al. Poly I:C-induced activation of NK cells by CD8 alpha + dendritic cells via the IPS-1 and TRIF-dependent pathways. J. Immunol.183, 2522–2528. 10.4049/jimmunol.0901500 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li, Y. et al. Establishment of cell clones with different metastatic potential from the metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma cell line MHCC97. World J. Gastroenterol.7, 630–636 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang, B. W. et al. Biological characteristics of fluorescent protein-expressing human hepatocellular carcinoma xenograft model in nude mice. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol.20, 1077–1084. 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3283050a67 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chiu, T. L., Lin, S. Z., Hsieh, W. H. & Peng, C. W. AAV2-mediated interleukin-12 in the treatment of malignant brain tumors through activation of NK cells. Int. J. Oncol.35, 1361–1367 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jia, Q. et al. Dual roles of WISP2 in the progression of hepatocellular carcinoma: implications of the fibroblast infiltration into the tumor microenvironment. Aging (Albany NY). 13, 21216–21231. 10.18632/aging.203424 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krusch, M. et al. The kinase inhibitors sunitinib and sorafenib differentially affect NK cell antitumor reactivity in vitro. J. Immunol.183, 8286–8294. 10.4049/jimmunol.0902404 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elkhenany, H., Shekshek, A. & Abdel-Daim, M. El-Badri, N. Stem Cell Therapy for Hepatocellular Carcinoma: future perspectives. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol.1237, 97–119. 10.1007/5584_2019_441 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Greten, T. F., Lai, C. W. & Li, G. Staveley-O’Carroll, K. F. Targeted and Immune-based therapies for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 156, 510–524. 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.09.051 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stotz, M. et al. Molecular targeted therapies in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: past, Present and Future. Anticancer Res.35, 5737–5744 (2015). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alfaro, C. et al. Influence of bevacizumab, sunitinib and sorafenib as single agents or in combination on the inhibitory effects of VEGF on human dendritic cell differentiation from monocytes. Br. J. Cancer. 100, 1111–1119. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604965 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu, Y. Y. et al. A synthetic dsRNA, as a TLR3 pathwaysynergist, combined with sorafenib suppresses HCC in vitro and in vivo. BMC Cancer. 13, 527. 10.1186/1471-2407-13-527 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 31.Chen, E. B. et al. The miR-561-5p/CX(3)CL1 Signaling Axis regulates pulmonary metastasis in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Involving CX(3)CR1(+) natural killer cells infiltration. Theranostics. 9, 4779–4794. 10.7150/thno.32543 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jung, I. H. et al. In Vivo Study of Natural Killer (NK) Cell Cytotoxicity Against Cholangiocarcinoma in a Nude Mouse Model. In Vivo 32, 771–781, doi: (2018). 10.21873/invivo.11307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Zhang, W. et al. Depletion of tumor-associated macrophages enhances the effect of sorafenib in metastatic liver cancer models by antimetastatic and antiangiogenic effects. Clin. Cancer Res.16, 3420–3430. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2904 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Girart, M. V., Fuertes, M. B., Domaica, C. I., Rossi, L. E. & Zwirner, N. W. Engagement of TLR3, TLR7, and NKG2D regulate IFN-gamma secretion but not NKG2D-mediated cytotoxicity by human NK cells stimulated with suboptimal doses of IL-12. J. Immunol.179, 3472–3479 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lin, Y. et al. Effect of TLR3 and TLR7 activation in uterine NK cells from non-obese diabetic (NOD) mice. J. Reprod. Immunol.82, 12–23. 10.1016/j.jri.2009.03.004 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.