Summary

Background

People with disabilities are at elevated risk of adverse short-term outcomes following hospitalization for acute infectious illness. No prior studies have compared long-term healthcare use among this high-risk population. We compared the healthcare use of adults with disabilities in the one year following hospitalization for COVID-19 vs. sepsis vs. influenza.

Methods

We performed a population-based cohort study using linked clinical and health administrative databases in Ontario, Canada of all adults with pre-existing disability (physical, sensory, or intellectual) hospitalized for COVID-19 (n = 22,551, median age 69 [IQR 57–79], 47.9% female) or sepsis (n = 100,669, median age 77 [IQR 66–85], 54.8% female) between January 25, 2020, and February 28, 2022, and for influenza (n = 11,216, median age 78 [IQR 67–86], 54% female) or sepsis (n = 49,326, median age 72 [IQR 62–82], 45.8% female) between January 1, 2014 and March 25, 2019. The exposure was hospitalization for laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 or influenza, or sepsis (not secondary to COVID-19 or influenza). Outcomes were ambulatory care visits, diagnostic testing, emergency department visits, hospitalization, palliative care visits and death within 1 year. Rates of these outcomes were compared across exposure groups using propensity-based overlap weighted Poisson and Cox proportional hazards models.

Findings

Among older adults with pre-existing disability, hospitalization for COVID-19 was associated with lower rates of ambulatory care visits (adjusted rate ratio (aRR) 0.88, 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.87–0.90), diagnostic testing (aRR 0.86, 95% CI, 0.84–0.89), emergency department visits (aRR 0.91, 95% CI, 0.84–0.97), hospitalization (aRR 0.74, 95% CI, 0.71–0.77), palliative care visits (aRR 0.71, 95% CI, 0.62–0.81) and low hazards of death (adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) 0.71, 95% 0.68–0.75), compared to hospitalization for sepsis during the COVID-19 pandemic. Rates of healthcare use among those hospitalized for COVID-19 varied compared to those hospitalized for influenza or sepsis prior to the pandemic.

Interpretation

This study of older adults with pre-existing disabilities hospitalized for acute infectious illness found that COVID-19 was not associated with higher rates of healthcare use or mortality over the one year following hospital discharge compared to those hospitalized for sepsis. However, hospitalization for COVID-19 was associated with higher rates of ambulatory care use and mortality when compared to influenza. As COVID-19 enters an endemic phase, the associated long-term health resource use and risks in the contemporary era are reassuringly similar to sepsis and influenza, even among people with pre-existing disabilities.

Funding

This study was supported by ICES, which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Long-Term Care. This study also received funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR GA4-177772).

Keywords: Disability, Acute infectious illness, COVID-19, Sepsis, Influenza, Healthcare use

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

People with disabilities are at elevated risk of developing severe adverse outcomes from acute infectious illnesses such as COVID-19, sepsis, and influenza. In part, this is due to a higher prevalence of underlying comorbid medical conditions, residence in congregate living settings, as well as systemic social and health inequities. Current knowledge is limited on how long-term healthcare use outcomes compare across different acute infectious illnesses among this high-risk population.

We searched PubMed and Google Scholar in August 2023 for studies reporting long-term healthcare use and mortality among adults with disabilities following hospitalization for infectious diseases. Search terms used included synonyms of “COVID-19”, “influenza”, “sepsis”, “mortality”, “healthcare use”, “health services”, and “disability”. Prior studies demonstrated that COVID-19 is associated with higher short-term healthcare use and a higher post-discharge risk of death among all adults and among those with pre-existing disabilities, compared to those without disabilities. However, emerging evidence suggests the long-term post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 may be comparable to other acute infections. We did not find any comparative studies examining the long-term impacts of acute infectious illness on healthcare use and mortality experienced by people with disabilities.

Added value of this study

This population-based cohort study of 94,762 older adults with pre-existing disability who survived hospitalization for acute infectious illness in Ontario, Canada found that COVID-19 was not associated with higher rates of healthcare use or mortality over the one year following hospital discharge compared to those hospitalized for sepsis. However, hospitalization for COVID-19 was associated with higher rates of ambulatory care use and mortality when compared to influenza. To the best of our knowledge, this is one of the first population-based comparative analyses of health services use outcomes among people with disabilities hospitalized for acute infectious illness.

Implications of all the available evidence

As COVID-19 enters an endemic phase, these findings aid in understanding healthcare use patterns of people with disabilities across three acute infectious illnesses. They demonstrate that with few exceptions, long-term healthcare use outcomes are generally similar across illness and time. This knowledge has important applications to clinical practice in clinician counselling of patients about the expected trajectories of disease following discharge from hospital. It further supports discharge planning for post-hospital care and informs long-term healthcare resource planning. This may be especially important given that healthcare use and unmet care needs among people with disabilities is generally higher than that of people without disabilities.

Introduction

There have been more than 770 million identified cases of COVID-19 worldwide.1 Post COVID-19 condition is variably defined as the persistence of symptoms (or development of health conditions) for four or more weeks after COVID-19 infection.2,3 These heterogenous symptoms and incident health conditions span multiple organ systems and are associated with reduced function, quality of life, and high health care use.3, 4, 5, 6, 7 Globally, an estimated 1.3 billion people live with disability, including physical disabilities affecting mobility, flexibility, dexterity or levels of pain; sensory disabilities affecting vision or hearing; and intellectual and developmental disabilities affecting cognitive and adaptive skills.8 People with disabilities often experience health disparities due to greater unmet healthcare needs coupled with worse access to healthcare, all of which can lead to worse health outcomes.9, 10, 11, 12 In turn, they are often at elevated risk of developing severe adverse outcomes from acute infectious illnesses such as COVID-19, sepsis, and influenza due to a higher prevalence of underlying comorbid medical conditions, residence in congregate living settings, as well as systemic social and health inequities.13, 14, 15, 16 However, current knowledge is limited on how long-term healthcare use outcomes compare between various acute infectious illnesses among this high-risk population. As COVID-19 enters an endemic phase, this knowledge is essential to inform clinicians as they counsel patients about their disease and manage health resource and discharge planning of people equally across reasons for hospitalization who are at higher risk of requiring additional healthcare supports.

Prior studies have shown COVID-19 is associated with higher healthcare use after the acute phase of the illness compared to people not diagnosed with COVID-19, as well as a higher post-discharge risk of death compared to historical influenza controls.17,18 However, the post-acute effects among all adults hospitalized for COVID-19 may be comparable to other acute infections.19 Additionally, a study examining healthcare outcomes among people hospitalized for COVID-19 found that people with disabilities had increased short-term healthcare use following hospital discharge compared to people without disabilities.20 The collective limitations of these studies include a lack of specific focus on people with pre-existing disabilities, limited generalizability across age groups, poorly matched cohort comorbidities and prior healthcare use, lack of inclusion of acute illness comparators, a focus on short-term outcomes, and experiences with early pandemic variants prior to vaccination. There is limited research about the effects of COVID-19 experienced by people with disabilities, and to our knowledge no prior studies have specifically examined long-term outcomes of hospitalization due to any type of acute infectious illnesses among people with disabilities.

People with disabilities are traditionally underrepresented in health research, have higher healthcare use, and face systemic obstacles to accessing care.21, 22, 23, 24 For healthcare systems to plan and manage resources to effectively meet the population needs of people with disabilities, policy makers must first understand the nature of their healthcare needs. This remains essential as jurisdictions navigate the post-pandemic landscape and study the healthcare use needs of people with disabilities who survived COVID-19 in comparison to other acute illnesses. Given these knowledge gaps, the objective of this population-level cohort study was to compare the healthcare use of adults with pre-existing disabilities in the one year following hospitalization for COVID-19 against three comparator groups: hospitalization for sepsis before (historical sepsis) and during (contemporary sepsis) the COVID-19 pandemic, and pre-pandemic hospitalization for influenza.

Methods

This study is reported in accordance with guidelines for the Reporting of Studies Conducted Using Observational Routinely Collected Health Data (RECORD).25

Study design, setting, population and data sources

We conducted a population-based cohort study in Ontario, Canada using linked clinical and health administrative databases at ICES (formerly the Institute for Clinical and Evaluative Sciences). These datasets are well validated and commonly used to conduct population-level studies in Ontario (Supplemental Table S1).

The administrative data sets used in this study were linked using unique encoded identifiers at the patient level and analyzed at ICES. Ontario is Canada's largest province, and its more than 15 million adults comprise nearly 40% of the national population. Ontario residents have public insurance for hospital care and physicians' services, and those aged ≥65 years receive prescription drug insurance via the Ontario Drug Benefit program.

ICES is an independent, non-profit research institute whose legal status under Ontario's health information privacy law allows it to collect and analyze health care and demographic data, without consent, for health system evaluation and improvement. The use of the data in this project is authorized under section 45 of Ontario's Personal Health Information Protection Act (PHIPA) and does not require review by a Research Ethics Board.

Study participants

Our study included 1) all Ontario adults (aged ≥18 years); 2) with a pre-existing disability; 3) who were hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 or influenza, or were hospitalized for sepsis (not including COVID-19 or influenza as a cause of sepsis); 4) between January 25, 2020 and February 28, 2022 (COVID-19 and contemporary sepsis group) or January 1, 2014 and March 25, 2019 (historical comparators for influenza and sepsis) and followed for up to 1 year after hospitalization, censoring for death and loss of Ontario Health Insurance Plan eligibility.

Our study excluded 1) people who died during their index hospitalization; 2) were hospitalized for sepsis or influenza in the one year prior to index study date; 3) were missing age or sex; 4) were not residents of Ontario; and 5) were not eligible for the Ontario Health Insurance Plan for ≥3 months in the year prior to study index date.

The index study date was the date of discharge from the hospital. Pre-existing disability was identified before index hospitalization using published algorithms developed to identify physical, sensory, intellectual and developmental disabilities in health administrative data.26, 27, 28 We defined pre-existing disability based on ≥2 physician visits or ≥1 emergency department visit between 2005 and index hospital admission date (Supplemental Table S2).

We did not include a contemporary influenza comparator because rates of influenza were extremely low during the COVID-19 pandemic.29 We used sepsis as a primary comparator because it is a severe acute infectious illness that was prevalent during the COVID-19 pandemic. We separated the hospitalization for sepsis into a pre-pandemic (historical) and pandemic (contemporary) group to compare the same acute infectious illness against COVID-19 during two separate time periods where healthcare use patterns may have significantly changed.

To create mutually exclusive comparator groups, we assigned individuals to each group based on their first occurrence of hospitalization for a specific cause, and once assigned they were removed from the pool of eligible people for other groups.

Exposure definitions

The primary exposure of hospitalization for COVID-19 was identified based on the presence of laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection via polymerase chain reaction testing that was performed within 14 days before admission or within three days after admission to hospital during the study period.30 This method has been shown to have similar accuracy in identifying people hospitalized with a main diagnosis of COVID-19, which has a 98% sensitivity and 99% specificity.30 Hospitalization for influenza was identified based on the presence of laboratory-confirmed influenza infection via polymerase chain reaction testing that was performed within 3 days before or after admission to hospital during the study period. Hospitalization for sepsis was based on a previously validated algorithm that is 72% sensitive and 85% specific.31,32

Outcomes definitions

The primary outcomes were measures of health services use and mortality within 12 months following discharge from index hospitalization. Measures of health services use included ambulatory care visits to primary or specialist care providers; ambulatory diagnostic testing (including cardiac, pulmonary, gastrointestinal, and radiologic); emergency department visits not resulting in hospital admission; hospital admissions; and palliative care visits. We identified the delivery of palliative care based on a set of unique physician claims fee codes.33 These codes were created to specifically indicate the delivery of palliative care and are related to treatments not intended to be curative, such as symptom management or counselling.

Covariates

Covariates were prespecified and identified as potential confounders based on the clinical and research expertise of our team and previous literature. Baseline characteristics measured at index date included age, sex, socioeconomic status, rural residence, comorbidities (labeled as chronic conditions in the tables),34 mental health conditions, surname-based ethnicity,35 hospitalization for pneumonia in the past 5 years, Hospital Frailty Risk Score,36 LACE score to predict risk for 30-day readmission (includes the length of hospitalization stay (L), acuity of the admission (A), comorbidities of patients (C), and the number of emergency department visits in the six months before admission (E)),37 use of mechanical ventilation during index hospitalization, intensive care unit (ICU) admission during index hospitalization, index hospitalization length of stay, health care use in 12 months prior to index hospitalization, and diagnosis of pre-existing subtype of disability (physical, sensory, or intellectual and developmental).26 Comorbidities were identified using the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision codes from the Ontario Health Insurance Plan database and the Discharge Abstract Database, using validated case ascertainment algorithms where available.38

Statistical analysis

We used propensity score-based overlap weighting to balance measured baseline characteristics between exposure groups and estimate the associated effects of COVID-19 hospitalization on our primary outcomes.39 Overlap weighting assigns weights to study cohort members proportional to the probability of that person belonging to the opposite exposure group and perfectly balances baseline characteristics to minimize confounding.39 Each patient was weighted according to their overlap weight, which was defined as their probability of being assigned to the opposite group based on the propensity score model.39 Overlap weights assign larger weights to patients with a high probability of receiving either exposure who have the greatest overlap in observed risk factors and assign lesser weights to patients at the extremes of the distribution.39 This protects against people at the extremes of the propensity score dominating the results and decreasing the precision, which occurs with inverse probability of treatment weighting.40

We defined the propensity score as the probability of being hospitalized for COVID-19 separately against sepsis and influenza, using multivariable random-effects logistic regression including the previously described covariates that are risk factors for severe COVID-19.40,41 Hospital random effects were also included in the propensity score to balance patients discharged from the same hospital to account for potential hospital-specific differences in care, discharge, and outcomes.40, 41, 42, 43 All outcomes are reported using the weighted results, unless otherwise specified.

We used Poisson and Cox proportional hazard regression models, weighted by overlap weights, to estimate adjusted rate ratios (aRRs) and adjusted hazard ratios (aHRs), respectively, between patients hospitalized with COVID-19 compared to those hospitalized with sepsis or influenza. Patients were censored at death. Models included a robust variance estimator to account for the weighting.44,45 We tested the proportional hazard assumption for the Cox model and performed a secondary analysis based on clinically relevant time periods of <30 days, 31–90 days, and >90 days post-hospitalization when the assumptions of proportionality were not met.

We performed additional exploratory analyses using a modified definition of disability that excluded adults exclusively with glaucoma, cataracts, or osteoarthritis as their cause of disability given that these conditions are highly prevalent among older adults and not always disabling in severity.

Statistical tests were 2-sided and performed at the 5% level of significance. All analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

Role of funding source

This study was supported by ICES, which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Long-Term Care. This study also received funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR GA4-177,772). The funders did not have any role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Results

Baseline characteristics

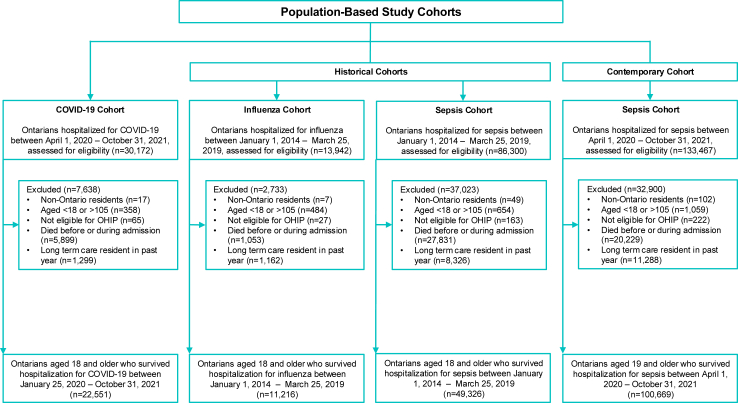

There were 22,551 people in the COVID-19 cohort and 100,669 people in the contemporaneous sepsis cohort (Fig. 1). Compared to people with contemporary sepsis, people with COVID-19 were younger and more likely to live in urban areas; less likely to have multiple disabilities; less likely to have multiple pre-existing comorbidities; and had lower healthcare services use in the 12 months before index. During the index hospitalization, they were less likely to experience delirium, had shorter hospital length of stay, and had lower frailty and LACE scores (Supplemental Table S3). These patterns were generally consistent when comparing the COVID-19 group to the historical sepsis and influenza groups (Supplemental Tables S5 and S7). The baseline characteristics of the weighted study cohorts are summarized in Table 1, and Supplemental Tables S4 and 6 In total, 20% (n = 5899/30,172) of the COVID-19 group, 15% (n = 20,229/133,467) of the contemporary sepsis group, 32% (n = 27,831/86,300) of the historical sepsis group, and 8% (n = 1053/13,942) of the influenza group died during their index hospitalization (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Creation of the study cohort.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study cohorts of adults who survived hospitalization for COVID-19 or contemporaneous sepsis, weighted by propensity-based overlap weights.

| Characteristic | COVID-19 | Sepsis (contemporary) | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, Median | 70.7 | 70.8 | 0.0 |

| Sex, (%) | |||

| Female | 48.6% | 48.6% | 0.0 |

| Male | 51.4% | 51.4% | 0.0 |

| Neighbourhood income quintile, (%) | |||

| Missing | 0.5% | 0.5% | 0.0 |

| 1 (lowest) | 30.5% | 30.5% | 0.0 |

| 2 | 22.6% | 22.6% | 0.0 |

| 3 | 18.1% | 18.1% | 0.0 |

| 4 | 15.2% | 15.2% | 0.0 |

| 5 (highest) | 13.2% | 13.2% | 0.0 |

| Rural residence, (%) | 6.9% | 6.9% | 0.0 |

| Surname-based ethnicity, (%) | |||

| South Asian | 5.1% | 3.6% | 0.1 |

| Chinese | 2.5% | 3.0% | 0.0 |

| General population | 92.4% | 93.4% | 0.0 |

| Missing information | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0 |

| Type of disability, (%) | |||

| Physical | 34.0% | 34.0% | 0.0 |

| Sensory | 17.4% | 17.4% | 0.0 |

| Intellectual and Developmental | 0.5% | 0.5% | 0.0 |

| Multiple | 48.1% | 48.1% | 0.0 |

| COVID-19 vaccination status, (%)a | |||

| Unvaccinated | 60.1% | 63.5% | 0.1 |

| Initiated primary series | 11.0% | 8.2% | 0.1 |

| Completed primary series | 18.4% | 23.1% | 0.1 |

| Completed primary series with 1 Health Canada-approved booster | 10.2% | 5.2% | 0.2 |

| Completed primary series with 2+ Health Canada-approved boosters | 0.2% | 0.1% | 0.0 |

| Chronic conditions | |||

| Acute myocardial infarction, (%) | 2.0% | 2.0% | 0.0 |

| Asthma, (%) | 11.6% | 11.6% | 0.0 |

| Arrythmia, (%) | 13.0% | 13.0% | 0.0 |

| Cancer, (%) | 36.2% | 36.2% | 0.0 |

| Chronic kidney disease, (%) | 32.6% | 32.6% | 0.0 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, (%) | 14.1% | 14.1% | 0.0 |

| Cirrhosis, (%) | 0.8% | 0.8% | 0.0 |

| Congestive heart failure, (%) | 19.5% | 19.5% | 0.0 |

| Coronary artery disease, (%) | 19.6% | 19.6% | 0.0 |

| Dementia, (%) | 5.2% | 5.2% | 0.0 |

| Depression/anxiety, (%) | 28.8% | 28.8% | 0.0 |

| Diabetes, (%) | 43.1% | 43.1% | 0.0 |

| Hospitalized for pneumonia in the past 5 years (not including pneumonia during index hospitalization), (%) | 7.0% | 7.0% | 0.0 |

| Hypertension, (%) | 67.2% | 67.2% | 0.0 |

| Immunocompromised, (%) | 18.9% | 18.9% | 0.0 |

| Psychotic disorder, (%) | 2.7% | 2.7% | 0.0 |

| Stroke, (%) | 7.0% | 7.0% | 0.0 |

| Substance use disorder, (%) | 5.7% | 5.7% | 0.0 |

| Venous thromboembolism, (%) | 3.1% | 3.1% | 0.0 |

| Myocardial infarction during index hospitalization, (%) | 1.5% | 1.5% | 0.0 |

| Total length of stay of index hospitalization (days), Mean | 14.4 | 14.4 | 0.0 |

| Mechanical ventilation during index hospitalization, (%) | 8.5% | 8.5% | 0.0 |

| ICU admission during index hospitalization, (%) | 20.1% | 20.1% | 0.0 |

| Delirium during index hospitalization, (%) | 16.2% | 16.2% | 0.0 |

| Hospital frailty risk score at discharge, (%) | |||

| 0 | 5.5% | 5.5% | 0.0 |

| 0.1–4.9 | 53.9% | 53.9% | 0.0 |

| 5.0–8.9 | 23.3% | 23.3% | 0.0 |

| 9.0+ | 17.3% | 17.3% | 0.0 |

| LACE score for index episode of care, (%) | |||

| 0–6 | 13.9% | 13.9% | 0.0 |

| 7–10 | 49.9% | 49.9% | 0.0 |

| 11+ | 36.1% | 36.1% | 0.0 |

| Healthcare services use in 12 months prior to index hospitalization | |||

| Number of ambulatory care visits, Mean | 14.3 | 14.3 | 0.0 |

| Palliative care receipt in past 12 months, (%) | 1.5% | 1.5% | 0.0 |

| Number of emergency department, Mean | 1.3 | 1.3 | 0.0 |

| Number of hospitalizations, Mean | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.0 |

| Number of diagnostic tests, Mean | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.0 |

| Number of unique prescription drugs (based on DINs), Mean | 12.1 | 12.1 | 0.0 |

1. IQR stands for interquartile range2. ICU stands for intensive care unit3. LACE score to predict risk for 30-day readmission (includes the length of hospitalization stay (L), acuity of the admission (A), comorbidities of patients (C), and the number of emergency department visits in the six months before admission (E)4. SD stands for standardized difference.

COVID-19 vaccination status was not included in the propensity score.

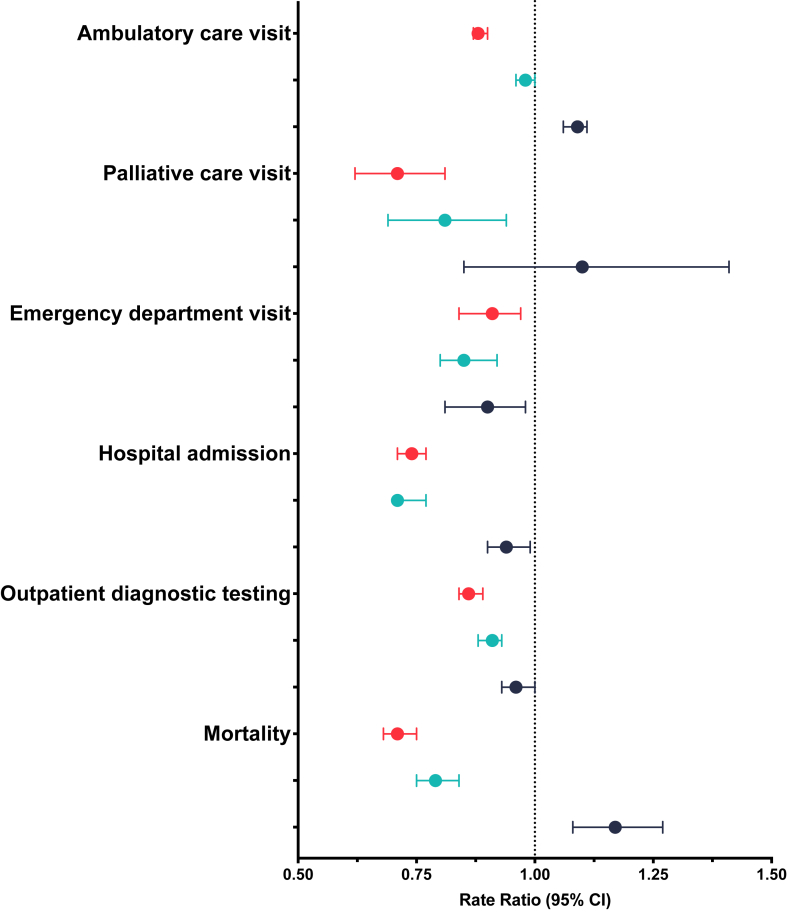

Healthcare services use

Within one year of discharge, COVID-19 was not associated with higher rates of healthcare services use including ambulatory care visits (aRR 0.88, 95% CI, 0.87–0.90), ambulatory diagnostic testing (aRR 0.86, 95% CI, 0.84–0.89), emergency department (aRR 0.91, 95% CI, 0.84–0.97), hospital admission (aRR 0.74, 95% CI, 0.71–0.77), and use of palliative care (aRR 0.71, 95% CI, 0.62–0.81) compared to the contemporary sepsis group. Similar patterns were observed when comparing hospitalization for COVID-19 with the historical sepsis group. Hospitalization for COVID-19 was associated with higher risk of ambulatory care visits (aRR 1.09, 95% CI, 1.06–1.11) compared to hospitalization for influenza (Table 2 and Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Analyses of long-term outcomes of healthcare use.

| Ambulatory care visit | Adjusted rate ratio (95% CI) |

| COVID-19 vs. contemporary sepsis | 0.88 (0.87, 0.90) |

| COVID-19 vs. historical sepsis | 0.98 (0.96, 1.00) |

| COVID-19 vs. influenza | 1.09 (1.06, 1.11) |

| Palliative care visit | Adjusted rate ratio (95% CI) |

| COVID-19 vs. contemporary sepsis | 0.71 (0.62, 0.81) |

| COVID-19 vs. historical sepsis | 0.81 (0.69, 0.94) |

| COVID-19 vs. influenza | 1.10 (0.85, 1.41) |

| Emergency department visit | Adjusted rate ratio (95% CI) |

| COVID-19 vs. contemporary sepsis | 0.91 (0.84, 0.97) |

| COVID-19 vs. historical sepsis | 0.85 (0.80, 0.92) |

| COVID-19 vs. influenza | 0.90 (0.81, 0.98) |

| Hospital admission | Adjusted rate ratio (95% CI) |

| COVID-19 vs. contemporary sepsis | 0.74 (0.71, 0.77) |

| COVID-19 vs. historical sepsis | 0.71 (0.71, 0.77) |

| COVID-19 vs. influenza | 0.94 (0.90, 0.99) |

| Outpatient diagnostic testing | Adjusted rate ratio (95% CI) |

| COVID-19 vs. contemporary sepsis | 0.86 (0.84, 0.89) |

| COVID-19 vs. historical sepsis | 0.91 (0.88, 0.93) |

| COVID-19 vs. influenza | 0.96 (0.93, 1.00) |

| Mortality | Adjusted hazard ratio (95% CI) |

| COVID-19 vs. contemporary | 0.71 (0.68, 0.75) |

| COVID-19 vs. historical sepsis | 0.79 (0.75, 0.84) |

| COVID-19 vs. influenza | 1.17 (1.08, 1.27) |

COVID-19 is the reference category for all analyses.

All outcomes were modelled using Poisson regression except for mortality which used Cox proportional hazard regression.

Fig. 2.

Primary analysis of outcomes (COVID-19 as the reference group). COVID-19 vs. contemporary sepsis is represented with red. COVID-19 vs. historical sepsis is represented in light blue. COVID-19 vs. influenza is represented in dark blue.

Within one year of discharge, COVID-19 hospitalization was not associated with a higher risk of mortality compared to the contemporary (aHR 0.71, 95% CI, 0.68–0.75) or historical sepsis groups (aHR 0.79, 95% CI, 0.75–0.84), but was associated with a higher risk of mortality compared to the influenza group (aHR 1.17, 95% CI, 1.08–1.27) (Fig. 2, Table 2, Table 3). Differences in mortality risk were noted across three distinct but clinically relevant periods. Within 30 days of discharge, COVID-19 hospitalization was not associated with significantly different risk of mortality compared to contemporary sepsis (HR 0.97, 95% CI, 0.89–1.06), but was associated with a lower risk of mortality in the 31–90 days post-hospitalization (HR 0.63, 95% CI, 0.56–0.70), and at >90 days post-hospitalization (HR 0.64, 95% CI, 0.60–0.69). Within 30 days of discharge, COVID-19 hospitalization was not associated with significantly different risk of mortality compared to historical sepsis (HR 0.99, 95% CI, 0.90–1.10), but was associated with a lower risk of mortality in the 31–90 days post-hospitalization (HR 0.68, 95% CI, 0.60–0.77) and at >90 days post-hospitalization (HR 0.75, 95% CI, 0.69–0.81). Within 30 days of discharge, COVID-19 hospitalization was associated with a higher risk of mortality compared to influenza (HR 2.12, 95% CI, 1.78–2.54), but was not associated with significantly different risk of mortality in the 31–90 days post-hospitalization (HR 1.15, 95% CI, 0.96–1.38) and at >90 days post-hospitalization (HR 0.93, 95% CI, 0.84–1.03).

Table 3.

Crude incidence rates (per 100 months) of long-term healthcare use.

| Ambulatory care visit | Crude rate (per 100 months) |

| COVID-19 | 128.9 |

| Contemporary sepsis | 151.1 |

| Historical sepsis | 140.7 |

| Influenza | 123.3 |

| Palliative care visit | Crude rate (per 100 months) |

| COVID-19 | 1.4 |

| Contemporary sepsis | 4.3 |

| Historical sepsis | 3.4 |

| Influenza | 2.0 |

| Emergency department visit | Crude rate (per 100 months) |

| COVID-19 | 8.6 |

| Contemporary sepsis | 12.6 |

| Historical sepsis | 14.8 |

| Influenza | 10.7 |

| Hospital admission | Crude rate (per 100 months) |

| COVID-19 | 4.7 |

| Contemporary sepsis | 9.7 |

| Historical sepsis | 10.8 |

| Influenza | 7.1 |

| Outpatient diagnostic testing | Crude rate (per 100 months) |

| COVID-19 | 41.9 |

| Contemporary sepsis | 58.3 |

| Historical sepsis | 63.3 |

| Influenza | 53.9 |

| Mortality | Incidence rate (per 100 months) |

| COVID-19 | 0.9 |

| Contemporary sepsis | 2.6 |

| Historical sepsis | 2.3 |

| Influenza | 1.2 |

These results were similar when modifying the definition of disability (Supplemental Table S8).

Discussion

This population-based study of all Ontario adults with a pre-existing disability who survived hospitalization for acute infectious illness found that COVID-19 was not associated with a higher rates of healthcare use or mortality over the one year following hospital discharge compared to those hospitalized for sepsis. However, hospitalization for COVID-19 was associated with higher rates of ambulatory care use and mortality when compared to influenza. To our knowledge, this is one of the first population-based analyses of health services use outcomes among people with disabilities hospitalized for acute infectious illness. These findings help in understanding healthcare use patterns of people with disabilities across three acute infectious illnesses, which is important for clinicians to understand as they counsel patients about expected trajectories of disease. These findings also support discharge planning for post-hospital care and inform long-term healthcare resource planning following hospitalization. This may be especially important given that healthcare use and unmet care needs among people with disabilities is generally higher than that of people without disabilities.12,20,46 These findings also help further elucidate the effects of COVID-19 from other acute infectious illnesses and show that with few exceptions, long-term healthcare use outcomes are generally similar across illness and time.

Several factors may partially explain our findings. First, the difference in baseline characteristics (namely age, number of disabilities and comorbidities, lower healthcare services use in 1 year preceding index hospitalization, and shorter index hospitalization length of stay) among the unweighted cohort of people with COVID-19 and sepsis may represent unmeasured care needs (i.e. residual confounding) or healthcare use patterns that influence long-term healthcare use. Second, the presence of a healthy selection bias among those who survived hospitalization with COVID-19 may influence the outcomes given that mortality rates were higher among the hospitalized COVID-19 cohort during the index hospitalization compared to the other groups. Third, it has been demonstrated that the severity of acute infectious illness is closely associated with rates of serious underlying health conditions, which may influence healthcare use following hospitalization, rather than the specific type of infection.45 This is important when considering whether post-hospital care should be organized differently depending on the type of acute infectious illness someone has, and the findings from this study and others strengthen the concept that post-hospital syndrome is a likely driver of higher healthcare use.47

Prior research has found people with disabilities have higher rates of symptoms after COVID-19, longer hospital stays, and elevated readmission risk compared to people without disabilities.20,48 Studies comparing people with disabilities who survived hospitalization for COVID-19 or influenza are lacking. However, prior studies of all hospitalized adults found high rates of death and adverse outcomes in both groups.17,49 Multiple studies comparing COVID-19 to other diseases have emphasized that long-term effects may not be specific to COVID-19, but to the overall severity of illness and hospitalization.19,49,50 However, few studies have compared long-term healthcare use after hospitalization for COVID-19 in people with disabilities. Therefore, our findings offer a significant contribution to the literature by using a comparative analysis to advance the understanding of long-term healthcare use for people with disabilities hospitalized for acute infectious illness and emphasize their long term healthcare needs.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of this study are the methodological and analytical approaches, including the use of population-level data with a diverse set of linked clinical and health measures, and the use of overlap weights to adjust for potential confounders. Additionally, this study focused on people with disabilities who are a population at an increased risk of adverse health outcomes and are traditionally underrepresented in research. In 2023, the NIH added people with disabilities to a group of populations that experience health disparities driven by social disadvantage and stated the need for research that improves understanding of the specific health issues and unmet needs of this population.51 Another strength of this study is the inclusion of historical comparator groups, which allows a relative comparison of healthcare use among people with disabilities before and during the pandemic, when healthcare delivery may have significantly changed.

There are several limitations. First, self-reported disability status is not available in health administrative data so we relied on previously published algorithms to identify disability in our data.26,28 To reduce the chance of selection bias in our study cohort, we ran additional analyses with a narrower definition of disability and observed similar associations in the results (Supplemental Table S1). Second, we are not able to directly attribute the healthcare use outcomes to the infectious diseases being studied. We employed propensity score-based overlap weighting to maximize the comparability of our study groups, but it remains important to recognize our findings are correlational and not causative. Third, we adjusted for the initial severity of acute infection, which may account for some of the associated effects on overall long-term healthcare use. In the contemporary era of COVID-19 variants and vaccination, we focused on whether people require additional healthcare supports beyond those that may be related to the severity of their initial illness to explore for the possibility of other COVID-19-specific effects. Fourth, by first creating cohorts of people with influenza and historical sepsis, we removed them from the potential pool of people who could be included in the COVID-19 and contemporary sepsis cohorts. This may have created healthier COVID-19 and contemporary sepsis cohorts. Despite potentially selecting for a healthier primary comparator group, mortality during index admission and healthcare use rates were similar between the COVID-19 and contemporary sepsis cohorts which strengthens our confidence in the findings. Fifth, there is a risk of misclassification bias based on the somewhat limited accuracy of the sepsis algorithm, the surname-based ethnicity algorithm, and lack of specifically validated algorithm to identify palliative care. Sixth, we did not account for the competing risk of death when measuring rates of healthcare use. Given the higher mortality observed for people hospitalized for sepsis compared to those with COVID-19 during follow-up, we believe that the reported rate ratios likely underestimate the differences. Seventh, while the use of overlap weights adjusts for potential confounders, there is a possibility of residual confounding based on unmeasured care needs of the study participants.

Conclusion

This study of older adults with pre-existing disabilities hospitalized for acute infectious illness found that COVID-19 was not associated with higher rates of healthcare use or mortality over the one year following hospital discharge compared to those hospitalized for sepsis. However, hospitalization for COVID-19 was associated with higher rates of ambulatory care use and mortality when compared to influenza. As COVID-19 enters an endemic phase, the associated long-term health resource use and risks in the contemporary era are reassuringly similar to sepsis and influenza, even among people with pre-existing disabilities.

Contributors

KQ, TS, HC, SL, YL, CB, AC, AD, SG, MH, FR, AA, HB, and PB conceptualised the study. HC, SL, TS, and KQ conducted the analyses. HC, SL, TS, and KQ verified the underlying data. JL, KQ and HC wrote the manuscript. All the authors had access to the data in the study, contributed to the data interpretation and discussion and approved the final manuscript version. KQ had the final responsibility for the decision to submit the study for publication.

Data sharing statement

The dataset from this study is held securely in coded form at ICES. While data sharing agreements prohibit ICES from making the dataset publicly available, access may be granted to those who meet pre-specified criteria for confidential access, available at www.ices.on.ca/DAS. The full dataset creation plan and underlying analytic code are available from the authors upon request, understanding that the computer programs may rely upon coding templates or macros that are unique to ICES and are therefore either inaccessible or may require modification.

Declaration of interests

Dr. Quinn reported personal fees through part-time employment at Public Health Ontario and stock in Pfizer and BioNTech outside the submitted work. Dr. Detsky reported owning stock in Pfizer and Johnson and Johnson, serving as a member of the TELUS Medical Advisory Committee, and serving on the scientific advisory body for Bindle Systems outside the submitted work. Dr. Razak reported being a salaried employee through Public Health Ontario as the scientific director of the COVID-19 advisory group outside the submitted work. Dr. Verma reported personal fees from Ontario Health and through the University of Toronto Temerty Professorship in AI Research and Education in Medicine outside the submitted work. No other disclosures were reported. Dr. Cheung reported that MediciNova provided drugs (ibudilast and placebo) for the CIHR-funded RECLAIM trial.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lana.2024.100910.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.WHO coronavirus (COVID-19) dashboard. https://covid19.who.int/ [cited 2023 Nov 4]. Available from:

- 2.CDC . Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2023. Post-COVID conditions: information for healthcare providers.https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/clinical-care/post-covid-conditions.html [cited 2023 Dec 5]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nalbandian A., Sehgal K., Gupta A., et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat Med. 2021;27(4):601–615. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01283-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang L., Li X., Gu X., et al. Health outcomes in people 2 years after surviving hospitalisation with COVID-19: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2022;10(9):863–876. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(22)00126-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Al-Aly Z., Xie Y., Bowe B. High-dimensional characterization of post-acute sequelae of COVID-19. Nature. 2021;594(7862):259–264. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03553-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McNaughton C.D., Austin P.C., Sivaswamy A., et al. Post-acute health care burden after SARS-CoV-2 infection: a retrospective cohort study. CMAJ. 2022;194(40):E1368–E1376. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.220728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thaweethai T., Jolley S.E., Karlson E.W., et al. Development of a definition of Postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection. JAMA. 2023;329(22):1934–1946. doi: 10.1001/jama.2023.8823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; 2022. Global report on health equity for persons with disabilities; p. 312.https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240063600 [cited 2024 Jul 1]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krahn G.L., Walker D.K., Correa-De-Araujo R. Persons with disabilities as an unrecognized health disparity population. Am J Public Health. 2015;105 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):S198–S206. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sakellariou D., Rotarou E.S. Access to healthcare for men and women with disabilities in the UK: secondary analysis of cross-sectional data. BMJ Open. 2017;7(8) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mitchell R.J., Ryder T., Matar K., Lystad R.P., Clay-Williams R., Braithwaite J. An overview of systematic reviews to determine the impact of socio-environmental factors on health outcomes of people with disabilities. Health Soc Care Community. 2022;30(4):1254–1274. doi: 10.1111/hsc.13665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Casey R. Disability and unmet health care needs in Canada: a longitudinal analysis. Disabil Health J. 2015;8(2):173–181. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2014.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsampasian V., Elghazaly H., Chattopadhyay R., et al. Risk factors associated with post-COVID-19 condition: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2023;183(6):566–580. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2023.0750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crook H., Raza S., Nowell J., Young M., Edison P. Long covid—mechanisms, risk factors, and management. BMJ. 2021;374 doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1648. https://www.bmj.com/content/374/bmj.n1648.abstract?casa_token=bb-9PqfNmasAAAAA:wt2wTTCa3d_uuipVZ9Xz-SA4al3wWaZnV599DAsb0HdGgRqUXw71b_Z1Jb7d9E_bQ3DV1SuyQWYNWw [cited 2023 Apr 3]. Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuper H., Smythe T. Are people with disabilities at higher risk of COVID-19-related mortality?: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Public Health. 2023;222:115–124. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2023.06.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Public Health Agency of Canada . Government of Canada; 2023. COVID-19 and people with disabilities in Canada.https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/2019-novel-coronavirus-infection/guidance-documents/people-with-disabilities.html [cited 2023 Nov 5]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oseran A.S., Song Y., Xu J., et al. Long term risk of death and readmission after hospital admission with covid-19 among older adults: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2023;382 doi: 10.1136/bmj-2023-076222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lo T., MacMillan A., Oudit G.Y., et al. Long-term health care use and diagnosis after hospitalization for COVID-19: a retrospective matched cohort study. CMAJ Open. 2023;11(4):E706–E715. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20220002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Quinn K.L., Stukel T.A., Huang A., et al. Comparison of medical and mental health sequelae following hospitalization for COVID-19, influenza, and sepsis. JAMA Intern Med. 2023;183(8):806–817. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2023.2228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brown H.K., Saha S., Chan T.C.Y., et al. Outcomes in patients with and without disability admitted to hospital with COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study. CMAJ. 2022;194(4):E112–E121. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.211277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koh H.K., Piotrowski J.J., Kumanyika S., Fielding J.E. Healthy people: a 2020 vision for the social determinants approach. Health Educ Behav. 2011;38(6):551–557. doi: 10.1177/1090198111428646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spong C.Y., Bianchi D.W. Improving public health requires inclusion of underrepresented populations in research. JAMA. 2018;319(4):337–338. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.19138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berghs M., Atkin K., Graham H., Hatton C., Thomas C. Implications for public health research of models and theories of disability: a scoping study and evidence synthesis. NIHR Journals Library; Southampton (UK): 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brooker K., van Dooren K., Tseng C.-H., McPherson L., Lennox N., Ware R. Out of sight, out of mind? The inclusion and identification of people with intellectual disability in public health research. Perspect Public Health. 2015;135(4):204–211. doi: 10.1177/1757913914552583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Benchimol E.I., Smeeth L., Guttmann A., et al. The REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely-collected health Data (RECORD) statement. PLoS Med. 2015;12(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin E., Balogh R., Cobigo V., Ouellette-Kuntz H., Wilton A.S., Lunsky Y. Using administrative health data to identify individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities: a comparison of algorithms. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2013;57(5):462–477. doi: 10.1111/jir.12002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Darney B.G., Biel F.M., Quigley B.P., Caughey A.B., Horner-Johnson W. Primary cesarean delivery patterns among women with physical, sensory, or intellectual disabilities. Womens Health Issues. 2017;27(3):336–344. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2016.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brown H.K., Ray J.G., Chen S., et al. Association of preexisting disability with severe maternal morbidity or mortality in Ontario, Canada. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(2) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.34993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parums D.V. Editorial: a decline in influenza during the COVID-19 pandemic and the emergence of potential epidemic and pandemic influenza viruses. Med Sci Monit. 2021;27 doi: 10.12659/MSM.934949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chung H., Austin P.C., Brown K.A., et al. Effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines over time prior to Omicron emergence in Ontario, Canada: test-negative design study. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2022;9(9) doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofac449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hamilton M.A., Calzavara A., Emerson S.D., et al. Validating international classification of disease 10th revision algorithms for identifying influenza and respiratory syncytial virus hospitalizations. PLoS One. 2021;16(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0244746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jolley R.J., Quan H., Jetté N., et al. Validation and optimisation of an ICD-10-coded case definition for sepsis using administrative health data. BMJ Open. 2015;5(12) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Quinn K.L., Stukel T., Stall N.M., et al. Association between palliative care and healthcare outcomes among adults with terminal non-cancer illness: population based matched cohort study. BMJ. 2020;370:m2257. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muggah E., Graves E., Bennett C., Manuel D.G. The impact of multiple chronic diseases on ambulatory care use; a population based study in Ontario, Canada. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:452. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shah B.R., Chiu M., Amin S., Ramani M., Sadry S., Tu J.V. Surname lists to identify South Asian and Chinese ethnicity from secondary data in Ontario, Canada: a validation study. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2010;10:42. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-10-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gilbert T., Neuburger J., Kraindler J., et al. Development and validation of a hospital frailty risk score focusing on older people in acute care settings using electronic hospital records: an observational study. Lancet. 2018;391(10132):1775–1782. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30668-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Staples J.A., Wiksyk B., Liu G., Desai S., van Walraven C., Sutherland J.M. External validation of the modified LACE+, LACE+, and LACE scores to predict readmission or death after hospital discharge. J Eval Clin Pract. 2021;27(6):1390–1397. doi: 10.1111/jep.13579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mondor L., Maxwell C.J., Hogan D.B., et al. Multimorbidity and healthcare utilization among home care clients with dementia in Ontario, Canada: a retrospective analysis of a population-based cohort. PLoS Med. 2017;14(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thomas L.E., Li F., Pencina M.J. Overlap weighting: a propensity score method that mimics attributes of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2020;323(23):2417–2418. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.7819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li F., Thomas L.E., Li F. Addressing extreme propensity scores via the overlap weights. Am J Epidemiol. 2019;188(1):250–257. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwy201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Austin P.C. The performance of different propensity score methods for estimating marginal hazard ratios. Stat Med. 2013;32(16):2837–2849. doi: 10.1002/sim.5705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saxena F.E., Bierman A.S., Glazier R.H., et al. Association of early physician follow-up with readmission among patients hospitalized for acute myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(7) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.22056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cafri G., Wang W., Chan P.H., Austin P.C. A review and empirical comparison of causal inference methods for clustered observational data with application to the evaluation of the effectiveness of medical devices. Stat Methods Med Res. 2019;28(10–11):3142–3162. doi: 10.1177/0962280218799540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li F., Morgan K.L., Zaslavsky A.M. Balancing covariates via propensity score weighting. J Am Stat Assoc. 2018;113(521):390–400. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lin D.Y., Wei L.J. The robust inference for the Cox proportional hazards model. J Am Stat Assoc. 1989;84(408):1074–1078. [Google Scholar]

- 46.WHO Team Sensory Functions . World Health Organization; 2011. Disability and rehabilitation (SDR). World report on disability.https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241564182 [cited 2024 Jul 1]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 47.Krumholz H.M. Post-hospital syndrome--an acquired, transient condition of generalized risk. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(2):100–102. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1212324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Government of Canada, Canada S . 2023. Experiences of Canadians with long-term symptoms following COVID-19.https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/75-006-x/2023001/article/00015-eng.htm [cited 2024 Feb 7]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xie Y., Choi T., Al-Aly Z. Long-term outcomes following hospital admission for COVID-19 versus seasonal influenza: a cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2023;24(3):239–255. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(23)00684-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Peinkhofer C., Zarifkar P., Christensen R.H.B., et al. Brain health after COVID-19, pneumonia, myocardial infarction, or critical illness. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(12) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.49659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.NIH designates people with disabilities as a population with health disparities. National Institutes of Health (NIH); 2023. https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/nih-designates-people-disabilities-population-health-disparities [cited 2024 Feb 7]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.