Abstract

In an era where entertainment is effortlessly at our fingertips, one would assume that people are less bored than ever. Yet, reports of boredom are higher now than compared to the past. This rising trend is concerning because chronic boredom can undermine well-being, learning, and behaviour. Understanding why this is happening is crucial to prevent further negative impacts. In this Perspective, we explore one possible reason—digital media use makes people more bored. We propose that digital media increases boredom through dividing attention, elevating desired level of engagement, reducing sense of meaning, heightening opportunity costs, and serving as an ineffective boredom coping strategy.

Subject terms: Psychology, Human behaviour

In recent years, there has been an increase in both reports of boredom and greater use of digital media. Digital media may exacerbate boredom via multiple pathways including dividing attention and reducing sense of meaning.

Introduction

It has never been easier to access stimulation. Just a few decades ago, we had to wait in front of the television for weekly broadcasts, turn to books or sluggish Internet browsers on clunky desktops for information, and rely on landline telephones for chatting with friends. Today, digital devices let us entertain, work, socialize, and access information anywhere, anytime. Technology has propelled us into an era of constant digital engagement. With endless rewarding stimulation a fingertip away, one would assume that boredom has become a rare experience. Yet, the reverse has happened: there had been a concerning rise in boredom among young people from 2009 to 2020, as revealed by nationally representative surveys1 and a meta-analysis of birth cohort changes2. People are becoming increasingly bored.

The question of why is pressing because chronic boredom can undermine well-being, learning, and behaviour. For example, it is associated with mental health issues like depressive symptoms and anxiety3, undesirable learning outcomes like poorer academic performance4, as well as problematic behaviours like sadistic aggression5. Exploring the reasons is critical to curb the trend and mitigate its adverse effects.

In this Perspective, we synthesize emerging findings and theories to propose a possible reason for the heightening boredom over the past decade: digital media use. We review empirical evidence on digital media use intensifying boredom. We then explore the underlying mechanisms through which digital media might contribute to increased boredom, including how it shifts attention, desire, sense of meaning, opportunity costs, and boredom coping. We begin, however, by discussing boredom and its rise over the years.

What is boredom?

It is unpleasant to be bored6,7. When state boredom (hereafter referred to as boredom) strikes, time appears to pass slowly8,9, while a range of negative emotions, such as sadness, loneliness, tiredness, restlessness, anxiety, anger, and frustration, may descend10–14. Defined as “an aversive state of wanting to, but being unable to, engage in satisfying activities” (p. 483)15, boredom is intricately tied to attention16–20. It is characterized by a feedback loop of attentional shifts, triggered by a gap between how engaged one wants to be and how engaged one is20. For example, situations lacking novelty21,22, meaning7,11,13,18,23, autonomy24, sense of agency25–27, and optimal challenge13,14,28 tend to provoke the feeling of boredom.

Despite its unpleasant experience, boredom serves an important self-regulatory function: it informs people that the current situation lacks meaning and fulfillment, motivating them to do something about it13,29. It can promote prosocial intention23, retrieval of nostalgic memories30, self-reflection31, and search for meaningful engagement23,30,32. Some people recognize these functions, indicating that boredom drives them to make changes, train their patience, as well as help them better discern what is truly meaningful or interesting to them33.

Dysfunction of this regulatory feedback loop, in which people repeatedly fail to attain fulfilling engagement, may prolong the experience of boredom20,34. Boredom proneness has been referred to as “trait boredom”27,35, “chronic boredom”20,36, “the tendency toward experiencing boredom” (p.14)37, and “the average intensity of boredom in response to a set of representative events over a defined period of time” (p. 204)38. Despite recurring criticisms over its conceptual ambiguity27,34,38–40, the importance of this construct is evident for its associations with well-being and at-risk behaviours3,5,41,42. Here, we refer to boredom proneness as chronic boredom—the long-term experience of boredom—given that it is characterized by the frequency and intensity of boredom, as well as a general perception of life as being boring39.

Chronic boredom can undermine mental health, learning, and behaviour. It is associated with depressive symptoms, anxiety, stress, apathy, anhedonia, and lower life satisfaction3,39,41,43,44. Academic boredom results in lower motivations to learn, poorer grades, and reduced academic effort and interest45–52. Behaviourally, momentary experiences of boredom can trigger sadistic aggression5,53, unhealthy snacking54,55, risk-taking42, ingroup favouritism, outgroup devaluation56, political polarization32, self-administering electric shocks54,57,58, as well as self-administering aversive sounds despite the presence of a positive alternative59. Chronic experience of it is linked to poorer self-control60,61, binge drinking62, and rule-breaking63,64.

Rising trends in boredom

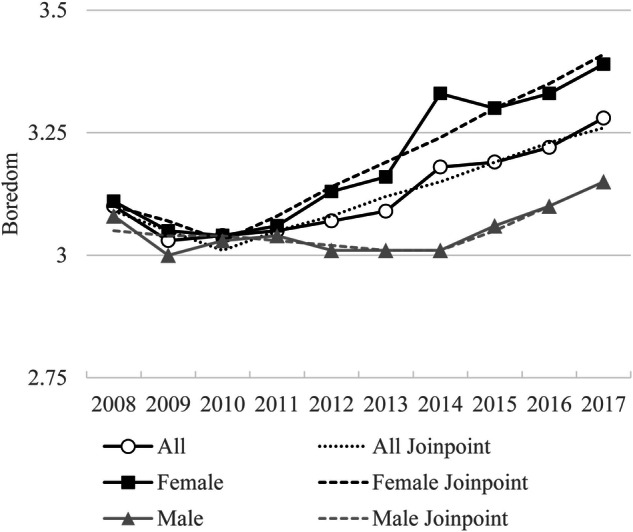

Research reveals a historical population-level increase in boredom over the past decade. One study identifies a rising trend in boredom frequency from 2010 to 2017 using multicohort, nationally representative samples of U.S. secondary school students (Fig. 1)1. Another study reports a similar increase in boredom proneness from 2009 to 2020 through a cross-temporal meta-analysis of 64 studies involving Chinese college students2.

Fig. 1. A historical trend in boredom from 2008 to 2017 in multicohort nationally representative samples of U.S. secondary school students.

Reprinted from Weybright, E. H. et al.1, Copyright (2020), with permission from Elsevier. The y-axis represents boredom, measured by a single item “I am often bored,” rated on a 5-point scale (1 = disagree, 5 = agree).

In the first study, Weybright and colleagues analysed data from annual surveys of nationally representative samples of 8th, 10th, and 12th graders across approximately 400 public and private high schools in the 48 contiguous U.S. states (N = 106,784)1. They observed a historical increase in frequency of boredom, measured by a single item “I am often bored,” rated on a 5-point scale (1 = disagree, 5 = agree). Using joinpoint regression, they found a non-significant decrease in boredom by 1.17% per year from 2008 to 2010, followed by a significant increase of 1.14% per year from 2010 to 2017 (see Fig. 1). Boredom levels were higher for boys by 1.6% per year from 2014 to 2017 and for girls by 1.7% per year from 2010 to 2017. While the slopes for each sex were significantly different, higher levels were evident across both.

The authors used an item with a 5-point scale, which has limitations in capturing variations in boredom due to its narrow range1. However, because the scale is narrow, even small absolute changes can reflect meaningful shifts in boredom. In terms of annual percent change, other studies using joinpoint regression have shown changes of such magnitude that are meaningful. For example, the prevalence of depression among U.S. adults increased by an average of 1.12% per year from 2013 to 202265. The global incidence of anxiety disorders among males increased by 0.35% per year from 2014 to 2019, while the increase among females was 0.25% per year from 2015 to 201966. Social isolation among Americans aged over 15 increased by 0.32% per year from 2003 to 2018, with a sharp rise of 5.65% per year from 2018 to 202067. These changes might appear small, but they carry significant implications as their effects could accumulate over time68.

In the second study, Gu and colleagues analysed data from 64 studies involving college students from mainland China (N = 28,269)2. They identified higher scores in later assessments in boredom proneness, measured by the Boredom Proneness Scale37—the most widely used measure for boredom40. Higher boredom proneness reflects higher frequency and intensity of boredom, as well as a holistic perception of life being boring39. In their cross-temporal meta-analysis, the authors found that the mean boredom proneness score of Chinese college students was higher in 2020 at 118.75 compared to 104.49 in 2009. The effect size of this increase, expressed in terms of Cohen’s d, was 1.57. When interpreted in terms of percentiles, if the mean in 2009 was at the 50th percentile, the mean in 2020 would be close to the 94th percentile of a normal distribution.

Both studies focused on student samples but did not assess boredom specifically within school settings1,2. Their findings, therefore, reflect broader experiences of boredom in daily life. Further research is needed to assess how they generalize to other age groups, cultural contexts, and educational backgrounds. Since the studies did not track boredom levels of the same individuals over time, future longitudinal research should explore within-person changes in boredom. Despite these limitations, both studies reported statistically significant higher levels of boredom in more recent reports, operationalized as boredom frequency and boredom proneness, with magnitudes comparable to other trends, such as rises in depression, anxiety and social isolation65–67, or demonstrating a large effect size2.

Our goal is not to create a moral panic, but rather to highlight a potentially concerning trend. Seemingly small effects of a psychological construct—consider how often it occurs in a day, week, or year—can accumulate over time and impact major life outcomes68. Feeling bored may seem trivial, but it can lead to negative mental health, learning, and behavioral outcomes. People are feeling bored more often. While more research on this increase is urgently needed before drawing any firm conclusions, we believe it is essential to explore the underlying reasons.

Digital media use makes people more bored

To explore the reasons for this increase, one must ask: What significant changes occurred worldwide during this time? While a lot had happened, one notable place to look is the advancement of digital technology. Both groups of researchers who identified the rising trend in boredom speculated that digital media played some role1,2. Indices of digital media use in China, including weekly internet usage per capita, internet penetration rate and mobile phone penetration rate, positively predicted boredom proneness levels from 2009 to 20202.

Over the past two decades, there has been a widespread proliferation of smartphones. The first Apple iPhone was introduced in 2007, and global smartphone sales surged from 122 million in 2007 to over 1.35 billion in 202069. Meanwhile, popular social media platforms emerged, including Facebook in 2004, YouTube in 2005, X (formerly Twitter) in 2006, WhatsApp in 2009, Instagram in 2010, and TikTok in 2016. Over 5 billion people worldwide are using social media in 2024, spending an average of 151 minutes per day on it—up from 40 min in 201570. Furthermore, video consumption gradually shifted from traditional television broadcasts to streaming services like Netflix, YouTube, and Prime Video. In the U.S., streaming video consumption surpassed cable TV viewing in 202271. Research on global trends indicates that daily screen time across devices, including computers, laptops, tablets, mobile phones, televisions, and game consoles, increased from 9 h in 2012 to 11 h in 2019, with time spent on mobile phones increasing by around 2 h72.

The advent of smartphones, along with the rise of social media and streaming platforms, have revolutionized people’s lives. They have amplified the quantity and diversity of information individuals encounter, granting instant access to news updates, insights into others’ lives and opinions via social media, and an abundance of entertainment options. They have reshaped how people access stimulation, making it easier, more convenient, and effortlessly accessible from any time at any location where WIFI or data connection permits. Entertainment73, relaxation74, information seeking75, and boredom relief75–77 are major motivations for digital media use. At the slightest hint of boredom, people can instantly pull out their phones for all aspects of stimulation.

Considering this, one might expect that digital media would reduce boredom. After all, some scholars have suggested that digital technologies leave little room for boredom, and people might even begin to feel nostalgic for times when they were bored78. Why, then, do we observe not only a rising trend in boredom1,2 but also a consistent positive relationship between boredom and digital media use79? Boredom is positively associated with problematic smartphone use80–85, social media use86–90, Internet use91,92, short video use93, as well as phubbing, the behaviour of ignoring a companion in favor of smartphone use94,95. A meta-analysis of 59 empirical studies demonstrates that boredom had a small-to-medium positive association with digital media use, and a medium-to-large association with problematic digital media use79.

Of course, a positive relationship can indicate that boredom drives digital media use, but it can also suggest that digital media use intensifies boredom. Accumulating evidence shows that digital media use, rather than reducing boredom, causally increases it. In one experiment, smartphone use intensified boredom in social interactions96. In another, engaging with social media via smartphone heightened boredom over time97. Moreover, boredom drove people to fast-forward or skip online videos, but this behaviour intensified boredom98. In an experience-sampling study that tracked hourly boredom levels and smartphone use at work, participants were more likely to use their smartphones when bored but reported increased boredom after using them99. In another experience-sampling study using a representative sample, X (formerly Twitter) use was associated with within-person increase in boredom100. Furthermore, a longitudinal study shows a bidirectional association between chronic boredom and problematic smartphone use, with problematic smartphone use being a stronger predictor of chronic boredom than the reverse82. Taken together, emerging research using diverse methodologies converges to suggest that digital media use causes people to become more bored. It is therefore plausible that digital media had contributed to the rising trend in boredom over the past decade.

Despite making a causal claim, we emphasize the need for further investigation to fully understand these relationships. Concerns about new technologies have been raised for centuries, such as Socrates’s worries about how writing might undermine memory101, and Neil Postman’s concerns about the effects of television on critical thinking102. While some of these fears are exaggerated, they might also contain a kernel of truth. The challenges of adapting to new technologies and understanding their effects on emotion, cognition, and well-being continue to evolve. Although we are concerned about the role of digital media in rising boredom, we are not suggesting it is the sole cause. We focus on digital media because, as outlined below, it is one plausible contributor based on existing theoretical and empirical evidence.

How does digital media increase boredom?

We suggest that digital media makes people more bored through dividing attention, elevating desired level of engagement, diminishing sense of meaning, raising opportunity costs, as well as serving as an ineffective boredom coping strategy.

Digital devices divide attention

Digital devices intensify boredom by disrupting attention. Inattention is a defining characteristic of boredom according to multiple theoretical models15,18,20,103–105. It distinguishes boredom from many other negative emotions7. Correlational16,44,106, experimental18, psychophysiological107, neuropsychological17,19, and intervention108 findings consistently suggest a robust relationship between inattention and boredom.

Whereas people feel bored when they fail to stay focused, digital devices bombard people with distracting signals and notifications throughout a day. It is reported that, on a typical day, young people receive a median of 237 notifications on their phones109. These notifications disrupt attention, slow reaction times, worsen task performance110,111, and prompt people to turn away from their current activities to check their phones112. Several experiments illustrate that the mere presence of a phone is sufficient to diminish attention and increase errors in cognitive tasks111,113,114. Smartphone use increases inattention, simultaneously intensifying boredom96,97.

While digital devices are distracting, the way people interact with them further impedes attention. Media multitasking describes the behaviour of engaging in multiple media activities, consuming separate media simultaneously, or performing various media tasks, each with its own objective115. It is common in many aspects of modern life, be it at work116–118, at school119,120, or in daily life121. This multitasking behaviour increases attentional failures122–124 and reduces enjoyment123,125. Switching between digital content, such as fast-forwarding and skipping videos, further reduces attention and intensifies boredom98. A network analysis reveals interlocking relationships between problematic short video use, state boredom, boredom proneness, and attention control93.

People’s habitual urge to check smartphones also disrupts daily activities. A study analysing first-person video recordings of daily smartphone behaviours reports that 89% of interactions were initiated by users, not the devices126. People engaged with their phones for approximately 10 min each hour, in a pattern of 1 min every 5 min. Smartphone checking predicted daily cognitive failures including higher distractibility127. In sum, digital media makes it harder for people to maintain focus on daily activities and reduces their intention to stay focused, thus increasing boredom.

Digital media elevates desired level of engagement

Digital media might also push up one’s desired level of engagement, rendering previously engaging activities boring. Boredom stems from a gap between actual and subjectively desired levels of attentional engagement20. In other words, even when people are engaged, boredom can still arise if they crave more engaging experiences. Theoretically, this desire, or say, the standard of what is sufficiently engaging, can be elevated by chronic exposure to rewarding stimulation20. According to research on affective habituation, repeated exposures to pleasurable stimuli reduce people’s sensitivity to them128,129. Digital media provides a regular stream of rewarding stimulation, including connection, social rewards, entertainment, and information73,74,130,131. It is thus possible that digital media heightens one’s desired level of attentional engagement, making activities that are less stimulating experienced as more boring.

How digital media influences desired engagement requires additional empirical study. For now, there are traces of such heightened desire in people. Over years, social media platforms have gradually shifted their content priorities to maintain user engagement, transitioning from text-based content to pictures, from pictures to videos, and now from longer videos to short-form videos132. This reflects a trend towards shorter, faster, more visually and auditorily stimulating content to capture attention. Shorter videos, for example, tend to receive more likes, comments, and shares133. During leisure, doing one activity at a time is no longer engaging enough so that many people now prefer to perform multiple activities at the same time. It is common for people to use a digital device while watching TV, a behaviour known as second screening134. An experience-sampling study suggests that media multitasking fulfills perceived emotional needs, such as the desire for entertainment or pleasure, but only when those needs are low135. It seems that some people have come to rely on multiple sources of stimulation for adequate engagement, reflecting an increased desire. With this heightened desire, people might readily find activities insufficiently engaging and become more prone to boredom.

Online information induces meaninglessness

Digital media potentially reduces sense of meaning and intensifies boredom by presenting an overwhelming amount of information that lacks coherence. Other than inattention, lack of meaning is another defining characteristic of boredom13,18,136 that differentiates it from other emotions7. The interlocking relationship between meaninglessness and boredom is evident in experimental13,23,32,41,56 and experience-sampling11,137 studies. Meaning emerges from a sense of coherence, that things make sense138–143. It is “the web of connections, understandings, and interpretations that help us comprehend our experience and formulate plans directing our energies to the achievement of our desired future” (p. 165)140. Sense of meaning thus partly hinges on the perception of coherence and reliable patterns139,140,142.

In the past, people primarily received information through traditional media channels like television, radio, newspapers, and books, where content was usually presented in a coherent, narrative format. Today, digital media not only offers an unparalleled amount and variety of information but also delivers it in a much more fragmented manner. For example, how does an Instagram post about pizza relate to a tweet about space exploration? And how do they relate to oneself? Processing the relationships between various pieces of online information can be challenging, if not impossible. Even simple experimental manipulation, such as presenting multiple videos or articles, can increase feelings of meaninglessness and boredom98. Online information tends to be far more incoherent than these experimental stimuli. From a sociological perspective, boredom occurs both with too little and too much information: too little leads to redundancy and monotony that little meaning can be derived from, while too much information is chaotic and noisy for effective meaning making144,145. It is plausible that digital media increases boredom by undermining people’s sense of meaning through its presentation of vast, disjointed information.

Digital devices raise opportunity costs

Digital devices offer countless options for stimulation, potentially raising the opportunity costs of other forms of engagement and thereby giving rise to boredom. Opportunity costs of a chosen activity are the forgone values of alternative activities. Experimental findings suggest that awareness of alternative activities increases the opportunity costs of the current activity, and when the freedom to switch to those alternatives is restricted, boredom arises98,146. For example, participants placed in a room filled with potential activities but instructed to occupy themselves solely with their thoughts experienced greater boredom than those in an empty room146.

Opportunity cost highlights the trade-offs in decision-making. It is related to, but distinct from, desired level of engagement, which refers to how engaged one wants to be20. For example, people might choose an activity with low opportunity costs, like watching a movie during free time, but still wish it was more engaging. Conversely, even if people did an activity with high opportunity costs, like studying instead of playing games, they might still find their engagement level in studying met their desired level. Also, people might have a high desire for engagement in situations where they gave up many interesting activities. These two constructs are interrelated.

While boredom is theorized to be intertwined with opportunity costs147,148, smartphones might readily amplify the opportunity costs of other daily activities by offering numerous entertaining alternatives. Before smartphones, the next best options to a given task included activities like daydreaming, observing the environment, or self-reflection—activities that, while less engaging, were readily available. However, smartphones, being portable and accessible anywhere, provide a variety of more engaging alternatives, such as chatting with friends or watching videos. This raises the opportunity costs of other activities, as smartphone use presents more attractive alternatives. Not to mention they regularly send notifications, like messages, social media updates, or latest podcast episodes, that remind users of the enjoyable activities they have forgone. This might be especially pronounced in environments like the workplace and school, where people are required to focus on other commitments. Taken together, digital devices might increase the opportunity costs of everyday activities, leading to the experience of boredom.

Using digital media to cope with boredom

Thus far, we have reviewed evidence on digital media use intensifying boredom, followed by its potential underlying mechanisms. This might seem counter-intuitive because people often turn to digital media as they believe it will relieve their boredom. Boredom relief is a primary motivation for using smartphone75–77 and social media75. However, using a digital device does not provide relief from boredom but often exacerbates it96,97,99. Boredom drives people to switch between digital content, yet this behaviour exacerbates boredom98.

In other words, people use digital media to avoid boredom, but this coping strategy is ineffective as it intensifies boredom rather than alleviating it. This might form a feedback loop that prolongs the bored experience, potentially leading to chronic boredom. Excessive smartphone use predicts chronic boredom, as shown in correlational, longitudinal, and meta-analytic studies79–85. Increased time spent on digital media72,149 might also reduce the relative time available for other meaningful leisure activities, thereby increasing boredom. People feel more bored using smartphones for entertainment compared to activities like exercising and socializing with others face-to-face11, but longer screen time is associated with less physical activity and outdoor time149.

From a predictive processing perspective, avoiding boredom may cause people to miss important information that this emotion provides150. For example, if people constantly use smartphones to escape boredom, they might overlook its crucial signals such as a lack of purposes or challenges in their lives. This short-term distraction could prevent them from making better long-term decisions to alleviate boredom effectively. Empirical evidence supports the notion that avoidance is ineffective for coping with boredom. People who tend to avoid boredom are more prone to boredom151. Students who adopt behavioral avoidance strategies to cope with boredom experience it more frequently and report lower enjoyment, interest, and effort in class152–154. In contrast, those who tend to use cognitive approach strategies, such as refocusing on the lesson, are less frequently bored153,154. With significant changes in technology and lifestyles over the past decade, people might not have adapted well to handling boredom, contributing to the rising trend in this emotion.

Outlook

Why are people more bored in this digital age? We suggest that digital media might have contributed to the increase in boredom through dividing attention, elevating desired level of engagement, reducing sense of meaning, raising opportunity costs, as well as serving as an ineffective boredom coping strategy. Based on these factors, the trend of rising boredom is likely to persist. People’s habits of interacting with digital media, coupled with their increasingly insatiable desire for stimulation, might result in spirals of boredom. This could gradually render once-enjoyable activities mundane and bring downstream negative learning, behavioral, and mental health consequences. To counter this trend and lessen its detrimental impacts, further research is vital. Here, we underscore several outstanding questions.

By no means are we suggesting that digital media is the only factor contributing to the increasing trend in boredom. Cultural shifts may also play a role, as many aspects of life, such as politics155–157 and religion158, have been subjected to the demands of entertainment102. Other possible factors include economic development2 and changes in social behaviours67. For future investigations, panel study would be helpful in exploring both interpersonal and intrapersonal factors that vary boredom levels over time and across developmental stages. Studying boredom from a population and societal perspective, which is currently lacking in the literature, would also provide valuable insights.

Digital media has irreversibly become an integral part of our lives. The challenge then is not to eliminate digital devices, but to explore how to best use them without exacerbating boredom. Investigations on time use and boredom can offer valuable insights into leading a more meaningful and engaging life. Research should also explore effective and adaptive strategies for coping with boredom, providing alternatives to digital media for individuals seeking relief. Emerging research highlights the link between boredom and sense of agency25–27, which is the perception that one initiates and controls one’s own actions159; future studies could examine how they relate to digital media use.

Given the paramount role of attention in boredom15,20 and evidence that attention training can reduce both state boredom and boredom proneness108, further investigations into strategies for sustaining focus and fostering motivation to stay focused, not only at work or school but also during entertainment, are essential. Research on desired level of engagement, including its determinants and impacts, is also needed. For instance, does frequent consumption of short-form videos impede engagement with longer videos, texts, or educational content? With easy access to stimulation and a heightened desire for engagement, could people become intolerant of even the possibility of feeling bored? Not everything in life is inherently and constantly interesting. There are, for example, stages in learning and practices that are tedious yet essential for personal growth. If people prioritize interestingness when deciding where to focus their attention, serious and important matters that lack immediate stimulation might struggle to hold their attention. In this digital age, learning to navigate mundane moments is more critical than ever.

Supplementary information

Author contributions

Katy Tam: conceptualization, writing – original draft, review & editing. Michael Inzlicht: conceptualization, review & editing, supervision.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications psychology thanks James Danckert and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Jennifer Bellingtier. A peer review file is available.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s44271-024-00155-9.

References

- 1.Weybright, E. H., Schulenberg, J. & Caldwell, L. L. More bored today than yesterday? National trends in adolescent boredom from 2008 to 2017. J. Adolesc. Health66, 360–365 (2020). This study identified a historical increasing trend in boredom from 2010 to 2017, using multicohort nationally representative samples of U.S. secondary school students. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gu, Z., Yang, C., Su, Q. & Liang, Y. The boredom proneness levels of Chinese college students increased over time: A meta-analysis of birth cohort differences from 2009 to 2020. Personal. Individ. Differ.215, 112370 (2023). This study identified an increasing trend in boredom proneness from 2009 to 2020 through a cross-temporal meta-analysis of 64 studies involving Chinese college students who completed the Boredom Proneness Scale. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee, F. K. S. & Zelman, D. C. Boredom proneness as a predictor of depression, anxiety and stress: The moderating effects of dispositional mindfulness. Personal. Individ. Differ.146, 68–75 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Camacho-Morles, J. et al. Activity achievement emotions and academic performance: A meta-analysis. Educ. Psychol. Rev.33, 1051–1095 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pfattheicher, S., Lazarević, L. B., Westgate, E. C. & Schindler, S. On the relation of boredom and sadistic aggression. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol.121, 573–600 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith, C. A. & Ellsworth, P. C. Patterns of cognitive appraisal in emotion. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol.48, 813–838 (1985). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Tilburg, W. A. P. & Igou, E. R. Boredom begs to differ: Differentiation from other negative emotions. Emotion17, 309–322 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martarelli, C. S., Weibel, D., Popic, D. & Wolff, W. Time in suspense: investigating boredom and related states in a virtual waiting room. Cogn. Emot. 1–15 10.1080/02699931.2024.2349279 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Witowska, J., Schmidt, S. & Wittmann, M. What happens while waiting? How self-regulation affects boredom and subjective time during a real waiting situation. Acta Psychol. (Amst.)205, 103061 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fahlman, S. A., Mercer-Lynn, K. B., Flora, D. B. & Eastwood, J. D. Development and validation of the Multidimensional State Boredom Scale. Assessment20, 68–85 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan, C. S. et al. Situational meaninglessness and state boredom: Cross-sectional and experience-sampling findings. Motiv. Emot.42, 555–565 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tam, K. Y. Y. & Chan, C. S. The effects of lack of meaning on trait and state loneliness: Correlational and experience-sampling evidence. Personal. Individ. Differ.141, 76–80 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Tilburg, W. A. P. & Igou, E. R. On boredom: Lack of challenge and meaning as distinct boredom experiences. Motiv. Emot.36, 181–194 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martin, M., Sadlo, G. & Stew, G. The phenomenon of boredom. Qual. Res. Psychol.3, 193–211 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eastwood, J. D., Frischen, A., Fenske, M. J. & Smilek, D. The unengaged mind: Defining boredom in terms of attention. Perspect. Psychol. Sci.7, 482–495 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hunter, A. & Eastwood, J. D. Does state boredom cause failures of attention? Examining the relations between trait boredom, state boredom, and sustained attention. Exp. Brain Res.236, 2483–2492 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yakobi, O., Boylan, J. & Danckert, J. Behavioral and electroencephalographic evidence for reduced attentional control and performance monitoring in boredom. Psychophysiology58, e13816 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Westgate, E. C. & Wilson, T. D. Boring thoughts and bored minds: The MAC model of boredom and cognitive engagement. Psychol. Rev.125, 689–713 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Danckert, J. & Merrifield, C. Boredom, sustained attention and the default mode network. Exp. Brain Res.236, 2507–2518 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tam, K. Y. Y., Van Tilburg, W. A. P., Chan, C. S., Igou, E. R. & Lau, H. Attention drifting in and out: The Boredom Feedback Model. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev.25, 251–272 (2021). This paper proposes a theoretical model in which boredom is characterized by a feedback loop of attention shifts triggered by a gap between one’s desired and actual levels of attentional engagement. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Daschmann, E. C., Goetz, T. & Stupnisky, R. H. Testing the predictors of boredom at school: Development and validation of the precursors to boredom scales: Antecedents to boredom scales. Br. J. Educ. Psychol.81, 421–440 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Hanlon, J. F. Boredom: Practical consequences and a theory. Acta Psychol. (Amst.)49, 53–82 (1981). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Tilburg, W. A. P. & Igou, E. R. Can boredom help? Increased prosocial intentions in response to boredom. Self Identity16, 82–96 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Hooft, E. A. J. & Van Hooff, M. L. M. The state of boredom: Frustrating or depressing? Motiv. Emot.42, 931–946 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eastwood, J. D. & Gorelik, D. Losing and finding agency. In The moral psychology of boredom (ed. Elpidorou, A.) (Rowman & Littlefield, 2022).

- 26.Dadzie, V. B., Drody, A. & Danckert, J. Exploring the relationship between boredom proneness and agency. Personal. Individ. Differ.222, 112602 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gorelik, D. & Eastwood, J. D. Trait boredom as a lack of agency: A theoretical model and a new assessment tool. Assessment 10731911231161780 10.1177/10731911231161780 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Harris, M. B. Correlates and characteristics of boredom proneness and boredom. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol.30, 576–598 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bench, S. W. & Lench, H. C. On the function of boredom. Behav. Sci.3, 459–472 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Tilburg, W. A. P., Igou, E. R. & Sedikides, C. In search of meaningfulness: Nostalgia as an antidote to boredom. Emotion13, 450–461 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lomas, T. A meditation on boredom: re-appraising its value through introspective phenomenology. Qual. Res. Psychol.14, 1–22 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Tilburg, W. A. P. & Igou, E. R. Going to political extremes in response to boredom: Boredom makes political orientations extremer. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol.46, 687–699 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tam, K. Y. Y., Van Tilburg, W. A. P. & Chan, C. S. Lay beliefs about boredom: A mixed-methods investigation. Motiv. Emot.47, 1075–1094 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Struk, A. A., Carriere, J. S. A., Cheyne, J. A. & Danckert, J. A short boredom proneness scale: Development and psychometric properties. Assessment24, 346–359 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mercer-Lynn, K. B., Hunter, J. A. & Eastwood, J. D. Is trait boredom redundant? J. Soc. Clin. Psychol.32, 897–916 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Todman, M. Boredom and psychotic disorders: Cognitive and motivational issues. Psychiatry Interpers. Biol. Process.66, 146–167 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Farmer, R. & Sundberg, N. D. Boredom proneness-the development and correlates of a new scale. J. Pers. Assess.50, 4–17 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Van Tilburg, W. A. P., Chan, C. S., Moynihan, A. B. & Igou, E. R. Boredom Proneness. In The Routledge International Handbook of Boredom (eds. Bieleke, M., Wolff, W. & Martarelli, C.) 191–210 (Routledge, 2024).

- 39.Tam, K. Y. Y., Van Tilburg, W. A. P. & Chan, C. S. What is boredom proneness? A comparison of three characterizations. J. Pers.89, 831–846 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vodanovich, S. J. & Watt, J. D. Self-report measures of boredom: An updated review of the literature. J. Psychol.150, 196–228 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fahlman, S. A., Mercer, K. B., Gaskovski, P., Eastwood, A. E. & Eastwood, J. D. Does a lack of life meaning cause boredom? Results from psychometric, longitudinal, and experimental analyses. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol.28, 307–340 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kılıç, A., Van Tilburg, W. A. P. & Igou, E. R. Risk‐taking increases under boredom. J. Behav. Decis. Mak.33, 257–269 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goldberg, Y. K., Eastwood, J. D., LaGuardia, J. & Danckert, J. Boredom: An emotional experience distinct from apathy, anhedonia, or depression. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol.30, 647–666 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Malkovsky, E., Merrifield, C., Goldberg, Y. & Danckert, J. Exploring the relationship between boredom and sustained attention. Exp. Brain Res.221, 59–67 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pekrun, R., Goetz, T., Titz, W. & Perry, R. P. Academic emotions in students’ self-regulated learning and achievement: A program of qualitative and quantitative research. Educ. Psychol.37, 91–105 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pekrun, R., Goetz, T., Daniels, L. M., Stupnisky, R. H. & Perry, R. P. Boredom in achievement settings: Exploring control–value antecedents and performance outcomes of a neglected emotion. J. Educ. Psychol.102, 531–549 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pekrun, R., Hall, N. C., Goetz, T. & Perry, R. P. Boredom and academic achievement: Testing a model of reciprocal causation. J. Educ. Psychol.106, 696–710 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Putwain, D. W., Becker, S., Symes, W. & Pekrun, R. Reciprocal relations between students’ academic enjoyment, boredom, and achievement over time. Learn. Instr.54, 73–81 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sharp, J. G., Hemmings, B., Kay, R., Murphy, B. & Elliott, S. Academic boredom among students in higher education: A mixed-methods exploration of characteristics, contributors and consequences. J. Furth. High. Educ.41, 657–677 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tam, K. Y. Y. et al. Boredom begets boredom: An experience sampling study on the impact of teacher boredom on student boredom and motivation. Br. J. Educ. Psychol.90, 124–137 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tze, V. M. C., Klassen, R. M. & Daniels, L. M. Patterns of boredom and its relationship with perceived autonomy support and engagement. Contemp. Educ. Psychol.39, 175–187 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tze, V. M. C., Daniels, L. M. & Klassen, R. M. Evaluating the relationship between boredom and academic outcomes: A meta-analysis. Educ. Psychol. Rev.28, 119–144 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pfattheicher, S. et al. I enjoy hurting my classmates: On the relation of boredom and sadism in schools. J. Sch. Psychol.96, 41–56 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Havermans, R. C., Vancleef, L., Kalamatianos, A. & Nederkoorn, C. Eating and inflicting pain out of boredom. Appetite85, 52–57 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moynihan, A. B. et al. Eaten up by boredom: consuming food to escape awareness of the bored self. Front. Psychol. 6, 369 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.Van Tilburg, W. A. P. & Igou, E. R. On boredom and social identity: A pragmatic meaning-regulation approach. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull.37, 1679–1691 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nederkoorn, C., Vancleef, L., Wilkenhöner, A., Claes, L. & Havermans, R. C. Self-inflicted pain out of boredom. Psychiatry Res237, 127–132 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wilson, T. D. et al. Just think: The challenges of the disengaged mind. Science345, 75–77 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yusoufzai, M. K., Nederkoorn, C., Lobbestael, J. & Vancleef, L. Sounds boring: the causal effect of boredom on self-administration of aversive stimuli in the presence of a positive alternative. Motiv. Emot.48, 222–236 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bieleke, M., Barton, L. & Wolff, W. Trajectories of boredom in self-control demanding tasks. Cogn. Emot. 1–11 10.1080/02699931.2021.1901656 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 61.Wolff, W. & Martarelli, C. S. Bored into depletion? Toward a tentative integration of perceived self-control exertion and boredom as guiding signals for goal-directed behavior. Perspect. Psychol. Sci.15, 1272–1283 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Biolcati, R., Passini, S. & Mancini, G. “I cannot stand the boredom.” Binge drinking expectancies in adolescence. Addict. Behav. Rep.3, 70–76 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Boylan, J., Seli, P., Scholer, A. A. & Danckert, J. Boredom in the COVID-19 pandemic: Trait boredom proneness, the desire to act, and rule-breaking. Personal. Individ. Differ.171, 110387 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wolff, W., Martarelli, C. S., Schüler, J. & Bieleke, M. High boredom proneness and low trait self-control impair adherence to social distancing guidelines during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health17, 5420 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Xu, Y. et al. Temporal trends and age-period-cohort analysis of depression in U.S. adults from 2013 to 2022. J. Affect. Disord.362, 237–243 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cao, H. et al. Global Trends in the Incidence of Anxiety Disorders From 1990 to 2019: Joinpoint and Age-Period-Cohort Analysis Study. JMIR Public Health Surveill10, e49609 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kannan, V. D. & Veazie, P. J. US trends in social isolation, social engagement, and companionship ⎯ nationally and by age, sex, race/ethnicity, family income, and work hours, 2003–2020. SSM - Popul. Health21, 101331 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Funder, D. C. & Ozer, D. J. Evaluating effect size in psychological research: Sense and nonsense. Adv. Methods Pract. Psychol. Sci.2, 156–168 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 69.Laricchia, F. Number of Smartphones Sold to End Users Worldwide from 2007 to 2023 [Infographic]. https://www.statista.com/statistics/263437/global-smartphone-sales-to-end-users-since-2007/ (2024).

- 70.Dixon, S. J. Number of Social Media Users Worldwide from 2017 to 2028 [Infographic]. https://www.statista.com/statistics/278414/number-of-worldwide-social-network-users/ (2024).

- 71.The Nielsen Company. Streaming claims largest piece of TV viewing pie in July. https://www.nielsen.com/insights/2022/streaming-claims-largest-piece-of-tv-viewing-pie-in-july/ (2022).

- 72.Harvey, D. L., Milton, K., Jones, A. P. & Atkin, A. J. International trends in screen-based behaviours from 2012 to 2019. Prev. Med.154, 106909 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wei, R. Motivations for using the mobile phone for mass communications and entertainment. Telemat. Inform.25, 36–46 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ho, H.-Y. & Syu, L.-Y. Uses and gratifications of mobile application users. In 2010 International Conference on Electronics and Information Engineering vol. 1 V1-315-V1-319 (2010).

- 75.Stockdale, L. A. & Coyne, S. M. Bored and online: Reasons for using social media, problematic social networking site use, and behavioral outcomes across the transition from adolescence to emerging adulthood. J. Adolesc.79, 173–183 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fullwood, C., Quinn, S., Kaye, L. K. & Redding, C. My virtual friend: A qualitative analysis of the attitudes and experiences of Smartphone users: Implications for Smartphone attachment. Comput. Hum. Behav.75, 347–355 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lepp, A., Barkley, J. E. & Li, J. Motivations and experiential outcomes associated with leisure time cell phone use: Results from two independent studies. Leis. Sci.39, 144–162 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 78.Holmboe, R. D. & Morris, S. Introduction: on boredom. in On Boredom: Essays in art and writing 1–6 (UCL Press, 2021).

- 79.Camerini, A.-L., Morlino, S. & Marciano, L. Boredom and digital media use: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep.11, 100313 (2023). This paper presents a meta-analysis of 59 empirical studies on boredom and digital media use published since 2003, reporting a medium-to-large positive association between boredom and problematic digital media use, as well as a small-to-medium association between boredom and digital media use. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhang, L., Wang, B., Xu, Q. & Fu, C. The role of boredom proneness and self-control in the association between anxiety and smartphone addiction among college students: a multiple mediation model. Front. Public Health11, 1201079 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wang, Y., Yang, H., Montag, C. & Elhai, J. D. Boredom proneness and rumination mediate relationships between depression and anxiety with problematic smartphone use severity. Curr. Psychol.41, 5287–5297 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zhang, Y., Li, S. & Yu, G. The longitudinal relationship between boredom proneness and mobile phone addiction: Evidence from a cross-lagged model. Curr. Psychol.41, 8821–8828 (2022). Cross-lagged analyses on longitudinal data suggest a bi-directional relationship between boredom proneness and smartphone addiction, whereas smartphone addiction is a stronger predictor of boredom proneness than the other way around. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yang, X.-J., Liu, Q.-Q., Lian, S.-L. & Zhou, Z.-K. Are bored minds more likely to be addicted? The relationship between boredom proneness and problematic mobile phone use. Addict. Behav.108, 106426 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ksinan, A. J., Mališ, J. & Vazsonyi, A. T. Swiping away the moments that make up a dull day: Narcissism, boredom, and compulsive smartphone use. Curr. Psychol. J. Diverse Perspect. Diverse Psychol. Issues40, 2917–2926 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 85.Elhai, J. D., Vasquez, J. K., Lustgarten, S. D., Levine, J. C. & Hall, B. J. Proneness to boredom mediates relationships between problematic smartphone use with depression and anxiety severity. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev.36, 707–720 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 86.Iannattone, S., Mezzalira, S., Bottesi, G., Gatta, M. & Miscioscia, M. Emotion dysregulation and psychopathological symptoms in non-clinical adolescents: The mediating role of boredom and social media use. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health18, 5 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Malik, L. et al. Mediating roles of fear of missing out and boredom proneness on psychological distress and social media addiction among Indian adolescents. J. Technol. Behav. Sci.9, 224–234 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Donati, M. A., Beccari, C. & Primi, C. Boredom and problematic Facebook use in adolescents: What is the relationship considering trait or state boredom? Addict. Behav.125, 107132 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bai, J. et al. The relationship between the use of mobile social media and subjective well-being: The mediating effect of boredom proneness. Front. Psychol.11, 568492 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Catedrilla, J. et al. Loneliness, boredom and information anxiety on problematic use of social media during the COVID-19 pandemic. In Proc. of the 28th international conference on computers in education 52–60 (2020).

- 91.Skues, J., Williams, B., Oldmeadow, J. & Wise, L. The effects of boredom, loneliness, and distress tolerance on problem Internet use among university students. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict.14, 167–180 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wegmann, E., Ostendorf, S. & Brand, M. Is it beneficial to use Internet-communication for escaping from boredom? Boredom proneness interacts with cue-induced craving and avoidance expectancies in explaining symptoms of Internet-communication disorder. PLOS ONE13, e0195742 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zhou, L. et al. A network analysis perspective on the relationship between boredom, attention control, and problematic short video use among a sample of Chinese young adults. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 10.1007/s11469-024-01392-z (2024). A network analysis reveals significant associations between problematic short video use, state boredom, boredom proneness, and attention control.

- 94.Al-Saggaf, Y. Phubbing, fear of missing out and boredom. J. Technol. Behav. Sci.6, 352–357 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 95.Al-Saggaf, Y., MacCulloch, R. & Wiener, K. Trait boredom is a predictor of phubbing frequency. J. Technol. Behav. Sci.4, 245–252 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 96.Dwyer, R. J., Kushlev, K. & Dunn, E. W. Smartphone use undermines enjoyment of face-to-face social interactions. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol.78, 233–239 (2018). This paper presents a field experiment and an experience-sampling study showing that people reported reduced enjoyment and increased boredom when phones were present (vs. absent) in social interactions. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Barkley, J. E. & Lepp, A. The effects of smartphone facilitated social media use, treadmill walking, and schoolwork on boredom in college students: Results of a within subjects, controlled experiment. Comput. Hum. Behav.114, 106555 (2021). In this experiment, participants in one of the conditions were asked to use their smartphones to engage with social media for 30 min; they reported an increase in boredom over time. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Tam, K. Y. Y. & Inzlicht, M. Fast-forward to boredom: How switching behavior on digital media makes people more bored. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 10.1037/xge0001639 (2024). This paper presents seven experiments demonstrating that boredom prompts people to switch between and within digital content, such as fast-forwarding and skipping videos, but these behaviours intensify boredom. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 99.Dora, J., Van Hooff, M., Geurts, S., Kompier, M. & Bijleveld, E. Fatigue, boredom and objectively measured smartphone use at work. R. Soc. Open Sci. 8, 201915 (2021). In this experience-sampling study, participants reported their level of boredom every hour at work; results indicate that participants were more likely to use their smartphones when they were bored, but they reported increased boredom after having used smartphone. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 100.Oldemburgo De Mello, V., Cheung, F. & Inzlicht, M. Twitter (X) use predicts substantial changes in well-being, polarization, sense of belonging, and outrage. Commun. Psychol.2, 15 (2024). This paper presents an experience-sampling study using a representative sample of U.S. X (Twitter) users; results show that X use was associated with within-person and between-person increases in boredom. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Plato: Phaedrus. (Cambridge University Press, 1972).

- 102.Postman, N. Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business. (Penguin, 1985).

- 103.Eastwood, J. D. & Gorelik, D. Boredom is a feeling of thinking and a double-edged sword. In Boredom Is in your mind: A shared psychological-philosophical approach (ed. Ros Velasco, J.) 55–70 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 10.1007/978-3-030-26395-9_4 2019).

- 104.Fisher, C. D. Effects of external and internal interruptions on boredom at work: two studies. J. Organ. Behav.19, 503–522 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 105.Leary, M. R., Rogers, P. A., Canfield, R. W. & Coe, C. Boredom in interpersonal encounters: Antecedents and social implications. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol.51, 968–975 (1986). [Google Scholar]

- 106.Isacescu, J., Struk, A. A. & Danckert, J. Cognitive and affective predictors of boredom proneness. Cogn. Emot.31, 1741–1748 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Merrifield, C. & Danckert, J. Characterizing the psychophysiological signature of boredom. Exp. Brain Res.232, 481–491 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Ng, H. C., Wong, W. L. & Chan, C. S. The effectiveness of an online attention training program in improving attention and reducing boredom. Motiv. Emot. 10.1007/s11031-024-10081-2 (2024).

- 109.Radesky, J. et al. Constant Companion: A Week in the Life of a Young Person’s Smartphone Use. https://www.commonsensemedia.org/sites/default/files/research/report/2023-cs-smartphone-research-report_final-for-web.pdf (2023).

- 110.Kaminske, A., Brown, A., Aylward, A. & Haller, M. Cell phone notifications harm attention: An exploration of the factors that contribute to distraction. Eur. J. Educ. Res.11, 1487–1494 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 111.Stothart, C., Mitchum, A. & Yehnert, C. The attentional cost of receiving a cell phone notification. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform.41, 893–897 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Dora, J., van Hooff, M., Geurts, S., Kompier, M. & Bijleveld, E. Labor/leisure decisions in their natural context: The case of the smartphone. Psychon. Bull. Rev.28, 676–685 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Ward, A. F., Duke, K., Gneezy, A. & Bos, M. W. Brain drain: The mere presence of one’s own smartphone reduces available cognitive capacity. J. Assoc. Consum. Res.2, 140–154 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 114.Thornton, B., Faires, A., Robbins, M. & Rollins, E. The mere presence of a cell phone may be distracting: Implications for attention and task performance. Soc. Psychol.45, 479–488 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 115.Segijn, C. M., Xiong, S. & Duff, B. R. L. Manipulating and measuring media multitasking: Implications of previous research and guidelines for future research. Commun. Methods Meas.13, 83–101 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 116.Addas, S. & Pinsonneault, A. The many faces of information technology interruptions: a taxonomy and preliminary investigation of their performance effects: Information technology interruptions taxonomy and performance effects. Inf. Syst. J.25, 231–273 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 117.Cao, H. et al. Large scale analysis of multitasking behavior during remote meetings. In Proceedings of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems 1–13 (ACM, Yokohama Japan, 10.1145/3411764.3445243. 2021)

- 118.Lieu, T. A. et al. Evaluation of attention switching and duration of electronic inbox work among primary care physicians. JAMA Netw. Open4, e2031856 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Mendoza, J. S., Pody, B. C., Lee, S., Kim, M. & McDonough, I. M. The effect of cellphones on attention and learning: The influences of time, distraction, and nomophobia. Comput. Hum. Behav.86, 52–60 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 120.Wammes, J. D. et al. Disengagement during lectures: Media multitasking and mind wandering in university classrooms. Comput. Educ.132, 76–89 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 121.Voorveld, H. A. M. & Goot, M. van der. Age differences in media multitasking: A diary study. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media57, 392–408 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 122.Magen, H. The relations between executive functions, media multitasking and polychronicity. Comput. Hum. Behav.67, 1–9 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 123.Oviedo, V., Tornquist, M., Cameron, T. & Chiappe, D. Effects of media multi-tasking with Facebook on the enjoyment and encoding of TV episodes. Comput. Hum. Behav.51, 407–417 (2015). This paper presents two experiments showing that participants reported reduced enjoyment when they interacted with Facebook while watching TV episodes. [Google Scholar]

- 124.Ralph, B. C. W., Thomson, D. R., Cheyne, J. A. & Smilek, D. Media multitasking and failures of attention in everyday life. Psychol. Res.78, 661–669 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Xu, S. & David, P. Distortions in time perceptions during task switching. Comput. Hum. Behav.80, 362–369 (2018). In this experiment, participants who switched between video and reading stimuli reported lower enjoyment than those who watched a video. [Google Scholar]

- 126.Heitmayer, M. & Lahlou, S. Why are smartphones disruptive? An empirical study of smartphone use in real-life contexts. Comput. Hum. Behav.116, 106637 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 127.Hartanto, A., Lee, K. Y. X., Chua, Y. J., Quek, F. Y. X. & Majeed, N. M. Smartphone use and daily cognitive failures: A critical examination using a daily diary approach with objective smartphone measures. Br. J. Psychol.114, 70–85 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Leventhal, A. M., Martin, R. L., Seals, R. W., Tapia, E. & Rehm, L. P. Investigating the dynamics of affect: Psychological mechanisms of affective habituation to pleasurable stimuli. Motiv. Emot.31, 145–157 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 129.Luo, Y., Zhang, X., Jiang, H. & Chen, X. The neural habituation to hedonic and eudaimonic rewards: Evidence from reward positivity. Psychophysiology59, e13977 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Maclean, J., Al-Saggaf, Y. & Hogg, R. Instagram photo sharing and its relationships with social rewards and well-being. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol.2, 242–250 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 131.Roberts, J. A. & David, M. E. The social media party: Fear of missing out (FoMO), social media intensity, connection, and well-being. Int. J. Human–Computer Interact36, 386–392 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 132.Babu, S. et al. Content marketing in the era of short-form video: TikTok and beyond. J. Inform. Educ. Res. 10.52783/jier.v4i2.1179 (2024).

- 133.Zhang, C., Zheng, H. & Wang, Q. Driving factors and moderating effects behind citizen engagement with mobile short-form videos. IEEE Access10, 40999–41009 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 134.Neate, T., Jones, M. & Evans, M. Cross-device media: A review of second screening and multi-device television. Pers. Ubiquitous Comput.21, 391–405 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 135.Wang, Z. & Tchernev, J. M. The “myth” of media multitasking: Reciprocal dynamics of media multitasking, personal needs, and gratifications. J. Commun.62, 493–513 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 136.Barbalet, J. M. Boredom and social meaning. Br. J. Sociol.50, 631–646 (1999). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Anusic, I., Lucas, R. E. & Donnellan, M. B. The validity of the day reconstruction method in the German Socio-Economic Panel Study. Soc. Indic. Res.130, 213–232 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Heine, S. J., Proulx, T. & Vohs, K. D. The meaning maintenance model: On the coherence of social motivations. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev.10, 88–110 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Heintzelman, S. J. & King, L. A. The feeling of) meaning-as-information.Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev.18, 153–167 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Steger, M. F. Experiencing meaning in life: Optimal functioning at the nexus of well-being, psychopathology, and spirituality. in The human quest for meaning 165–184. (Routledge, New York, 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 141.Baumeister, R. F. Meanings of Life. (Guilford, New York, 1991).

- 142.Hicks, J. A., Cicero, D. C., Trent, J., Burton, C. M. & King, L. A. Positive affect, intuition, and feelings of meaning. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol.98, 967–979 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Proulx, T. & Inzlicht, M. The Five “A”s of Meaning Maintenance: Finding Meaning in the Theories of Sense-Making. Psychol. Inq.23, 317–335 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 144.Klapp, O. E. Overload and Boredom: Essays on the Quality of Life in the Information Society. (Greenwood Publishing Group Inc., 1986).

- 145.Danckert, J. & Gopal, A. Boredom as information processing: How revisiting ideas from Orin Klapp (1986) inform the psychology of boredom. J. Boredom Stud. 1–16 10.5281/zenodo.10737026 (2024).

- 146.Struk, A. A., Scholer, A. A., Danckert, J. & Seli, P. Rich environments, dull experiences: how environment can exacerbate the effect of constraint on the experience of boredom. Cogn. Emot.34, 1517–1523 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Kurzban, R., Duckworth, A., Kable, J. W. & Myers, J. An opportunity cost model of subjective effort and task performance. Behav. Brain Sci.36, 661–679 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Agrawal, M., Mattar, M. G., Cohen, J. D. & Daw, N. D. The temporal dynamics of opportunity costs: A normative account of cognitive fatigue and boredom. Psychol. Rev.129, 564–585 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Auhuber, L., Vogel, M., Grafe, N., Kiess, W. & Poulain, T. Leisure activities of healthy children and adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health16, 2078 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Darling, T. Synthesising boredom: A predictive processing approach. Synthese202, 157 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 151.Bieleke, M., Ripper, L., Schüler, J. & Wolff, W. Boredom is the root of all evil—or is it? A psychometric network approach to individual differences in behavioural responses to boredom. R. Soc. Open Sci.9, 211998 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Eren, A. & Coskun, H. Students’ level of boredom, boredom coping strategies, epistemic curiosity, and graded performance. J. Educ. Res.109, 574–588 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 153.Nett, U. E., Goetz, T. & Daniels, L. M. What to do when feeling bored? Students’ strategies for coping with boredom. Learn. Individ. Differ.20, 626–638 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 154.Nett, U. E., Goetz, T. & Hall, N. C. Coping with boredom in school: An experience sampling perspective. Contemp. Educ. Psychol.36, 49–59 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 155.Penney, J. ‘It’s so hard not to be funny in this situation’: Memes and humor in US youth online political expression. Telev. New Media21, 791–806 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 156.Bartsch, A. & Schneider, F. M. Entertainment and politics revisited: How non-escapist forms of entertainment can stimulate political interest and information seeking. J. Commun.64, 369–396 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 157.Matthes, J., Heiss, R. & Van Scharrel, H. The distraction effect. Political and entertainment-oriented content on social media, political participation, interest, and knowledge. Comput. Hum. Behav.142, 107644 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 158.Moore, R. L. Selling God: American Religion in the Marketplace of Culture. (Oxford University Press, USA, 1994).

- 159.Synofzik, M., Vosgerau, G. & Newen, A. Beyond the comparator model: A multifactorial two-step account of agency. Conscious. Cogn.17, 219–239 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.