Abstract

Considering the limited information on the impact of PM2.5 content on ocular health, a follow-up study was conducted on 50 healthy adults. Samples were collected twice, once before the PM2.5 exposure season and again after exposure. Daily PM2.5 concentration data was gathered from Thung Satok monitoring station. All subjects completed the self-structured ocular symptom questionnaire. The concentrations of 1-OHP were determined using HPLC-FLD. Logistic regression analysis investigated the relationship between PM2.5 toxicity and ocular symptoms. The findings revealed that daily PM2.5 concentrations surpassed the WHO-recommended range by around threefold. Exposure to PM2.5 significantly raised the likelihood of ocular redness (adjusted OR: 12.39, 95% CI), watering (adjusted OR: 2.56, 95% CI), and dryness (adjusted OR: 5.06, 95% CI). Additionally, these symptoms had an exposure-response relationship with increasing 1-OHP levels. Ocular symptoms worsened in frequency and severity during the high PM2.5 season, showing a strong link to elevated PM2.5 levels. Lymphocyte counts were also positively correlated with redness, watering, and dryness during high PM2.5 exposure. In conclusion, our study shows that subjects exposed to higher PM2.5 levels presented more significant ocular surface alterations.

Keywords: PM2.5, Ocular, Health, 1-OHP

Subject terms: Diagnostic markers, Environmental sciences, Risk factors

Introduction

Environmental pollution is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in third-world countries and a primary issue in developing nations1,2. The changing climate has led to shifts in exposure to air pollutants, including various contaminants. Of them, Ambient Particulate Matter (PM2.5) with a diameter of less than 2.5 μm is particularly worrisome due to its potential to cause detrimental health effects. Additionally, PM2.5 has a considerably larger surface area than PM10, making it potentially more toxic as it can absorb more harmful substances from the air3,4.

Thailand faces unique environmental challenges within the wider framework of worldwide concerns regarding air pollution. Air pollution stands as a critical and persistent problem, particularly in the northern region of Thailand, where agricultural fields burning during the dry season and increased wildfire risk due to the region’s vegetation and climate exacerbate the issue5,6. Air pollution has a significant impact on Chiang Mai, a province located in the mountainous region of Northern Thailand. The air quality levels in this region have surpassed the daily standards recommended by both the World Health Organization (15 µg/m3) and the Thai Pollution Control Department (50 µg/m)7. Both human activity-related airborne pollutants and periodic biomass burning substantially impact air quality in northern Thailand and Southeast Asia8. Certainly, the environment’s ultrafine particles, such as PM2.5, pose a significant threat, causing inflammation and oxidative damage2. Additionally, PM2.5 has been shown to affect mitochondrial function and promote mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis in human ocular cells, contributing to the progression of ocular surface diseases9.

Various toxicological studies have shown that PM2.5 contains a substantial amount of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAH). PAHs are organic compounds with at least two aromatic rings. Due to their low volatile nature, PAHs can be inhaled easily when conjugated with PM10. PAHs encompass several hundred compounds, including pyrene. CYP1A1 metabolizes pyrene into 1-hydroxypyrene (1-OHP), which is conjugated with glucuronide or sulfate and excreted in urine. Urinary 1-OHP is the most crucial indicator for assessing individual exposure to PAHs. It offers a comprehensive measure of total PAH exposure from all pathways, including oral and dermal, instead of solely relying on air PAH levels. Once the body absorbs PAHs, they are metabolized into intermediates, some of which are mutagenic and carcinogenic. Low-weight PAH metabolites are predominantly excreted in urine, while high-weight PAHs are primarily eliminated through feces11–13.

Several epidemiological investigations have demonstrated that elevated concentrations of air pollutants are linked to both short-term and long-term health outcomes. These outcomes include an increased risk of stroke, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, respiratory diseases, and ocular surface diseases. This suggests that exposure to high levels of air pollution may have far-reaching implications for public health14. Previous studies showed that exposure to PM2.5 reduces the proliferation of human corneal epithelial cells (HCECs), which induces subclinical Inflammation by damaging the ocular surface cells15,16. Long-term exposure to air pollution can lead to biological alterations, such as goblet-cell hyperplasia on the ocular surface. PM2.5 exposure has been related to various ocular symptoms, including dry eyes, tear film instability, and general ocular discomfort like irritation and foreign body sensation. Visual problems such as blurred vision and decreased corneal clarity can also occur. Additionally, PM exposure can worsen allergic reactions, resulting in itching, tears, and conjunctival injection. Blepharitis, which is characterized by red eyelids and heavier meibomian gland secretions, can also develop. Chronic exposure can cause corneal damage, conjunctival hyperplasia, and reduced goblet cell density, aggravating pre-existing problems such as dry eye and allergic conjunctivitis. These ocular disorders can substantially influence daily activities and road safety due to discomforts such as burning, redness, dryness, and tears3,17.

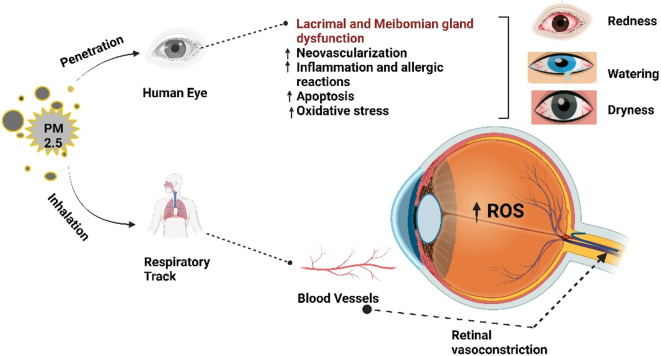

Exposure to PM2.5 has been associated with oxidative stress and inflammatory responses, which are critical mechanisms in developing ocular surface diseases18. The small size of PM2.5 allows it to penetrate deeply into the ocular tissues, leading to cellular damage and inflammation Fig. 1. PM2.5-induced inflammation contributes to oxidative damage through the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), exacerbating ocular surface damage and leading to conditions such as conjunctivitis and dry eye syndrome19. This particulate matter can carry toxic substances like polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), heavy metals, and biological allergens, which further amplify inflammatory processes20. The oxidative stress from PM2.5 generates ROS that damage ocular cells, resulting in symptoms such as dryness, redness, and irritation21. Moreover, the systemic inflammatory response triggered by PM2.5 exposure is reflected in alterations in CBC parameters, including lymphocyte counts. Studies have shown that PM2.5 can modulate immune responses, potentially leading to lymphopenia or an altered lymphocyte profile, which may exacerbate eye inflammatory conditions22. The association between PM2.5 exposure, ocular symptoms, and changes in lymphocyte counts demonstrates the interconnectedness of local and systemic immune responses in the context of environmental pollution23,24.

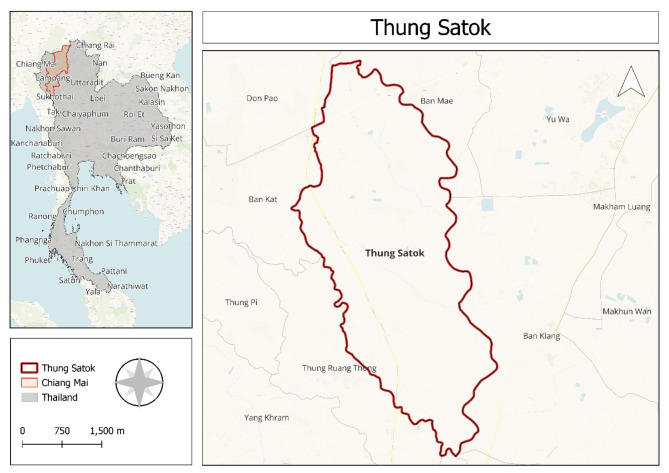

Fig. 2.

The location of the study region and PM2.5 monitoring (The map generated by using QGIS version 3.32.1 -Lima, QGIS is licensed under the GNU General Public License: www.gnu.org/licenses).

Fig. 1.

This illustration clearly portrays the impact of PM2.5 exposure on ocular health through inhalation and direct penetration into the eye. PM2.5 induces lacrimal and Meibomian gland dysfunction, leading to neovascularization, inflammation, apoptosis, and oxidative.

Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the impact of PM2.5 exposure on ocular health, specifically focusing on the severity of eye symptoms and their association with blood parameters.

Materials and methods

Study region

Chiang Mai is situated at latitude 18° North and longitude 98° East. We collected the data from the area of Thung Sa Tok, a subdistrict of San Pa Tong, Chaing Mai, Thailand (Fig. 2). The climate is generally tropical wet and dry, with the average yearly temperature being around 27.82 °C (Thai Meteorological Department).

Study population

The study was rigorously conducted in the Thung Sa Tok, a subdistrict of San Pa Tong, Chaing Mai, Thailand. Only individuals who had been residing in the study area for at least six months were recruited. Participants over 18 years of age underwent a thorough physical examination to confirm their health status. The study unequivocally excluded individuals using eye medications, except for artificial tears or over-the-counter allergy medications, and those with respiratory conditions affecting ocular symptoms. This study is a follow-up study with a sample size of 50. The participants were selected using the convenience sampling method, and samples were collected twice: once during the before- PM2.5 exposure season (October- December 2023) and again after the PM2.5 exposure (February- April 2024).

Monitoring of air quality and PM 2.5 concentrations

The concentrations of PM2.5 were measured and recorded daily; Air pollution data on a daily basis were obtained from the Northern Thailand Air Quality Index(NTAQI) (https://www2.ntaqhi.info/?area-point=50240363). To conduct this study, we calculated the daily average.

Questionnaire

After explaining the study’s purpose, informed consent was obtained from all participants. Participants underwent a structured interview using a standardized questionnaire to gather detailed information about demographics and ocular allergy symptoms. The questionnaire was distributed twice: first, during the before- PM2.5 exposure period (October-December 2023) and second, during the PM2.5 exposure period (February-April 2024).

The questionnaire inquired about the frequency and severity of eye irritation, redness, itching, and tearing. It asked about participants’ history of eye allergies or other eye-related diseases, such as conjunctivitis or dry eye syndrome, and if a healthcare expert had diagnosed them with allergies. The questionnaire also inquired about participants’ exposure to potential allergens such as pollen, dust, and pet dander, as well as how frequently they became subjected to high levels of air pollution, such as in areas with heavy traffic or industrial activity. Participants were also asked about using protective measures to decrease PM2.5 exposure, such as masks or air purifiers, and if they had sought medical treatment or advice for PM2.5-related eye complaints. Finally, the questionnaire asked about current eye medications or treatments, as well as personal measurements and PM2.5 pollution prevention strategies.

Complete blood count parameters

Blood samples were collected from the participants twice. Every sample underwent a full blood count (CBC) via an automated hematology analyzer Sysmex XN1000i (Sysmex Corporation, Kobe, Japan)22.

1-Hydroxypyrene (1-OHP)

From the study participants, fifty milliliters of morning urine samples were obtained at two different times, i.e., before and after PM 2.5 exposure. Extracted the 1-OHP from urine by using the enzymatic hydrolysis method23. Ten milliliters of urine sample and adjusted its pH to 5.0 using 1 M HCl. The sample was then transferred into a 50 mL screw cap test tube containing 10 mL of 0.1 M acetate buffer and 25 µL of β-glucuronidase from Helix pomatia. The mixture was shaken using a vortex for 10 s and then incubated at 37 °C for 2 h. After that, the samples were vacuum eluted using an SPE VertiPak C18 3mL cartridge, which had been pre-conditioned with 1 mL of methanol (three times) and 1 mL of water (three times). The samples were loaded completely onto the cartridge and washed with 10 mL of water and 10 mL of 20% methanol. The cartridge was then released and left to stand for approximately 10 min. Subsequently, the samples were eluted with 10 mL of methanol. The resulting solution was evaporated to dryness under a stream of nitrogen gas and then reconstituted in 200 µL of methanol. This solution was filtered through a 0.2 μm PTFE syringe filter before analysis. The analysis was performed using an HPLC 1260 infinity II Agilent system under the following conditions: a 20 µL injection volume, with the mobile phase consisting of 45% water (Line A) and 55% acetonitrile (Line B) at a flow rate of 0.80 mL/min. The column used was an Infinity Lab Poroshell 120 EC-C18 (25 cm x 5 mm x 5 μm), maintained at 25 °C. Detection was carried out using a fluorescence detector (FLD) (1260 Infinity II, Agilent, USA) with an excitation wavelength of 242 nm and an emission wavelength of 388 nm. The PMT gain was set to 10, and the response time was 0.25 s. The total run time for the HPLC analysis was 20 min24.

Based on the concentrations of 1-OHP standards of 0.05, 0.25, 0.50, 1.00, and 2.5 ng/mL, a standard curve was generated. Signal response (peak area) was plotted against known concentrations, and the calibration equation was derived using linear regression (y = 1.23x + 0.01, R2 = 0.998). The calculation of sample concentrations was based on this calibration equation. The limits of quantification (LOQ) and limits of detection (LOD) were 0.7140 and 0.0430 ng/ml23.

1-OHP is included as a covariate to control for the confounding effects of PAH exposure, which is closely linked to PM2.5 in the study area. This adjustment allowed for a clearer analysis of the direct impact of PM2.5 on ocular health, independent of PAH exposure.

Ethical considerations

The study protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Associate Medical Sciences, Chiang Mai University (protocol code AMSEC-66EX-062) and the date of approval (03-10-2023) and was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics software (version 22), with data collected at two distinct time points: low PM2.5 season (October-December 2023) and following high PM2.5 season (February-April 2024). To assess data distribution, the Shapiro-Wilk test was employed to evaluate normality for each variable. Variables failing to meet the criteria for normal distribution were analyzed using the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test to compare differences between groups. For variables conforming to a normal distribution, parametric analysis was performed utilizing the Student’s t-test. Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation. The significance level (alpha error) was established at 5% for all statistical tests. Spearman’s rank correlation analysis was utilized to explore the relationships between white blood cell parameters (WBC, neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, eosinophils, basophils) and ocular symptoms (redness, itching, burning, watering, dryness, blurry vision, sensitivity to light), given the nonparametric nature of the data. Logistic regression analyses were conducted to adjust for potential confounders, including 1-OHP levels, gender, and occupation. This analysis assessed the odds of experiencing various ocular symptoms concerning PM2.5 exposure, accounting for these potential influencing factors.

Results

The study encompassed a total of 50 participants, consisting of 29 females and 21 males. A detailed overview of the participants’ demographic characteristics, physical parameters, and lifestyle habits is provided in Table 1. The average age of female participants was 58 ± 7.96 years, while male participants averaged 58.71 ± 7.48 years. There was no significant difference between the two groups (p = 0.750). The average heart rate (HR) for females was 24.76 ± 9.67 beats per minute; for males, it was 24 ± 6.20, with no significant difference evident (p = 0.754). However, there were notable discrepancies in systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP). The average SBP was 124.45 ± 15.85 mmHg for females and 135 ± 18.07 for males (p = 0.033). The average DBP was 74.86 ± 8.21 for females and 81.48 ± 11.63 for males (p = 0.022). The mean body mass index (BMI) for females stood at 23.96 ± 3.94 kg/m2 and for males at 24.92 ± 4.70), demonstrating no significant difference (p = 0.434). Similar smoking habits were observed between the two groups, with 10.3% of females and 14.3% of males reporting smoking (p = 1.000).

Table 1.

Selected characteristics show demographic parameters, physical examinations, and lifestyle habits. P-values are based on the independent samples t-test for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. All variables were assessed during the first visit. (p < 0.05 considered to be significant)

| Female | Male | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 29 | 21 | |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 58.00 ± 7.96) | 58.71 ± 7.48) | 0.750 |

| Heart Rate (mean ± SD) | 24.76 ± 9.67) | 24.0 ± 6.20 | 0.754 |

| Systolic BP (mean ± SD) | 124.45 ± 15.85 | 135.00 ± 18.07 | 0.033 |

| Diastolic BP (mean ± SD) | 74.86 ± 8.21 | 81.48 ± 11.63 | 0.022 |

| Body Mass Index (mean ± SD) | 23.96 ± 3.94) | 24.92 ± 4.70 | 0.434 |

| Smoking = yes (%) | 3 (10.3) | 3 (14.3) | 1.000 |

| Body Temperature (mean ± SD) | 35.98 ± 0.55 | 36.03 ± 0.51 | 0.732 |

| Alcohol = yes (%) | 4 (13.8) | 10 (47.6) | 0.021 |

| Weight (mean ± SD) | 56.76 ± 10.20 | 63.17 ± 13.91 | 0.066 |

| Pulse (mean ± SD) | 80.38 ± 11.61 | 75.10 ± 13.76 | 0.148 |

| Total (N = 50) |

Furthermore, the average body temperature (BT) for females was 35.98 ± 0.55 °C, and for males was 36.03 ± 0.51, displaying no significant difference (p = 0.732). Notably, alcohol consumption was significantly higher among males, with 47.6% reporting alcohol use compared to 13.8% of females (p = 0.021). The average weight of female participants totaled 56.76 ± 10.20 kg; for males, it was 63.17 ± 13.91, with a marginally significant difference (p = 0.066). The average pulse rate stood at 80.38 ± 11.61beats per minute for females and 75.10 ± 13.76 for males, with no significant difference (p = 0.148).

PM 2.5 seasonal trends

Figure 3 displays the daily PM2.5 levels measured at the fixed air monitoring station in the subdistrict center. The data obtained from the NTAQHI website, specifically from the Thung Satok station, confirms significant variations in air quality between the high season (February to April) and the low season (October to December). During the high season, the PM2.5 level was notably higher at 44.66 ± 25.08 µg/m2 (p < 0.001) compared to the low season at 11.95 ± 6.10 µg/m2 (p < 0.001, Student’s t-test), highlighting substantial differences in air pollution between the two periods.

Fig. 3.

Daily PM2.5 concentrations found in the Subdistrict, Thung Satok during the sampling period.

1-Hydroxypyrene as a biomarker of exposure to Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAH)

1-Hydroxypyrene (1-OHP) levels were evaluated as a PM2.5 pollution exposure biomarker. The linear regression model revealed a significant relationship between PM 2.5 levels and 1-OHP, with the coefficient for Season (High PM2.5 season) showing a value of 1.496, which was statistically significant (p = 0.007). This positive coefficient indicates that 1-OHP levels were higher during the high PM2.5 (Visit 2) compared to the low PM2.5 (Visit 1). Specifically, 1-OHP levels in the high PM2.5 season were approximately 1.496 units higher than in the low PM2.5 season. During Visit 1, the mean 1-OHP level was 0.3604 ± 0.8441, while in Visit 2, it increased to 1.9261 ± 3.8114 (Fig. 4), confirming a significant difference between the two seasons (p < 0.001).

Fig. 4.

Mean 1-hydroxypyrene (1-OHP) levels (µmol/mol Cr) during low and high PM2.5 seasons. Bars represent mean values with standard deviation (p < 0.001).

Association between seasons and ocular allergic symptoms

Table 2 displays the relationship between seasons and ocular allergic symptoms, adjusting for 1-OHP, gender, and occupation. The findings indicate that during times of high PM2.5 exposure, redness of the eyes had a notably higher odds ratio (OR) with an unadjusted OR of 5.27 (95% CI: 1.07, 25.99) and an adjusted OR of 12.39 (95% CI: 2.45, 62.63), both of which are statistically significant (p < 0.05). Furthermore, watering of the eyes was significantly linked to high PM2.5 exposure, with an unadjusted OR of 2.07 (95% CI: 0.93, 4.62) and an adjusted OR of 2.56 (95% CI: 1.09, 5.99). Dryness of the eyes also displayed a significant association, with an unadjusted OR of 1.83 (95% CI: 0.61, 5.53) and an adjusted OR of 5.06 (95% CI: 1.27, 20.15), indicating an escalated risk during periods of high exposure. On the other hand, symptoms such as itching, burning, blurry vision, and sensitivity to light did not show significant associations with PM2.5 exposure. Even after adjustment, the ORs for these symptoms remained non-significant. There was an evident exposure-response relationship with 1-OHP levels only for redness, watering, and dryness.

Table 2.

Shows the unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for various ocular symptoms after adjusting for 1-OHP, gender, and occupation. An asterisk *typically denotes a statistically significant result.

| Symptoms | OR (95% CI) Unadjusted |

OR (95% CI) Adjusted |

|---|---|---|

| Redness | 5.27 (1.07,25.99)* | 12.39 (2.45,62.63)* |

| Itching | 1.0 (0.45,2.20) | 1.13 (0.49,2.58) |

| Burning | 1.3 (0.47,3.68) | 1.50 (0.54,4.18) |

| Watering | 2.07 (0.93,4.62) | 2.56 (1.09,5.99)* |

| Dryness | 1.83 (0.61,5.53) | 5.06 (1.27,20.15)* |

| Blurry Vision | 1.54 (0.53,4.45) | 1.56 (0.49,4.92) |

| Swelling | - | - |

| Sensitivity to light | 1.00 (0.19,5.25) | 1.52 (0.28,8.17) |

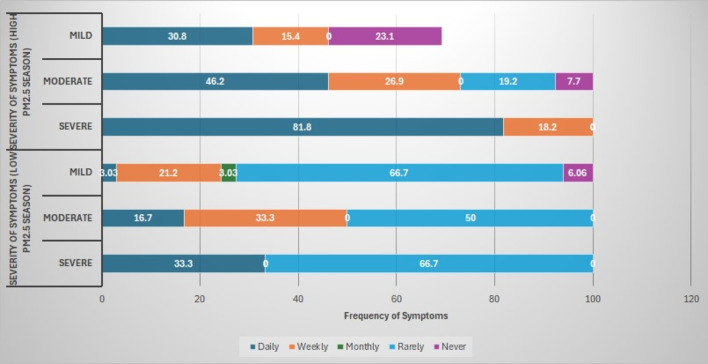

Furthermore, Fig. 5, a bar chart shows a noticeable increase in the frequency and severity of symptoms during the high PM2.5 season. While mild and moderate symptoms are more commonly experienced daily or weekly during high PM2.5 exposure, severe symptoms, in particular, show a stark shift with a significant portion of participants reporting them on a daily basis compared to the low PM2.5 season, where they were mainly rare. This suggests a strong correlation between higher PM2.5 levels and both the severity and frequency of ocular symptoms.

Fig. 5.

A bar chart showing the comparison of the frequency and severity of ocular symptoms between the low and high PM2.5 seasons.

Influence of seasonal PM2.5 variations on hematologic and ocular health indicators

Table 3 provides a detailed analysis of the correlation between white blood cell (WBC) parameters and various ocular symptoms in low and high PM2.5 season. The table focuses on significant correlations to clarify the relationship between WBC parameters and symptoms such as redness, watering, and dryness of the eyes. For redness, a significant positive correlation with lymphocyte levels was observed in high PM2.5 season (r = 0.286, p = 0.049), suggesting that higher lymphocyte counts are associated with increased redness. Neutrophils showed a negative correlation in the low PM2.5 season (r = -0.245, p = 0.093), indicating a potential trend where lower neutrophil levels may relate to increased redness. For watering, significant positive correlations with lymphocyte levels were found both in low (r = 0.315, p = 0.029) and in high (r = 0.315, p = 0.029) PM2.5 season, highlighting that higher lymphocyte counts are consistently associated with more watering of the eyes. A significant negative correlation was noted between neutrophils and watering in high PM2.5 season (r = -0.301, p = 0.038), suggesting that higher neutrophil levels could be associated with reduced watering. Regarding dryness, a positive correlation with lymphocyte levels was significant during high PM2.5 season (r = 0.321, p = 0.026), and a similar trend was seen during low PM2.5 season (r = 0.135, p = 0.351), indicating that increased lymphocyte counts are associated with greater dryness. Additionally, monocytes showed a significant positive correlation with dryness in low PM2.5 season (r = 0.287, p = 0.044). These results suggest that elevated lymphocyte and monocyte levels are linked to increased ocular symptoms such as redness, watering, and dryness, reinforcing the impact of PM2.5 exposure on ocular health. This detailed correlation analysis supports the conclusion that PM2.5 exposure exacerbates ocular symptoms through changes in white blood cell parameters, highlighting the importance of monitoring these parameters for assessing ocular health in polluted environments.

Table 3.

Correlation between White Blood Cell parameters and ocular symptoms during low and high PM2.5 season.

| Symptoms | WBC Parameter | Mean ± S.D (Low PM2.5 Season) | Mean ± S.D (High PM2.5 Season) | Correlation Coefficient (r) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Redness |

Lymphocytes Neutrophils Monocytes |

33.20 ± 7.92 | 33.85 ± 8.08 | 0.286* | 0.049 |

| 55.85 ± 8.87 | 54.12 ± 8.89 | -0.245 | 0.093 | ||

| 7.16 ± 2.23 | 7.27 ± 1.92 | 0.088 | 0.545 | ||

| Watering |

Lymphocytes Neutrophils Monocytes |

33.20 ± 7.92 | 33.85 ± 8.08 | 0.315* | 0.029 |

| 55.85 ± 8.87 | 54.12 ± 8.89 | -0.301 | 0.038 | ||

| 7.16 ± 2.23 | 7.27 ± 1.92 | -0.218 | 0.137 | ||

| Dryness |

Lymphocytes Neutrophils Monocytes |

33.20 ± 7.92 | 33.85 ± 8.08 | 0.321* | 0.026 |

| 55.85 ± 8.87 | 54.12 ± 8.89 | -0.217 | 0.139 | ||

| 7.16 ± 2.23 | 7.27 ± 1.92 | 0.287* | 0.044 |

SD: standard deviation, *significant correlation, Pearson’s Correlation.

Discussion

Our findings strongly demonstrated that research participants were exposed to high amounts of PM2.5, resulting in elevated urine 1-OHP levels. This strong exposure directly correlated with adverse ocular health outcomes, as indicated by observed symptoms such as redness, watering, and dryness. Our research findings echo prior studies, Kahe, et al.25 highlighted a significant sevenfold surge in daily PM2.5 concentrations, while our study reveals a threefold increase, surpassing the WHO-recommended 15 µg/m3 threshold. Notably, the specific levels of PM2.5 concentrations in our study area may differ from those reported in other regions due to local variations in pollution sources and meteorological conditions.

In our investigation into the potential health effects of PM2.5 pollution exposure, we rigorously sought to establish a statistical link between PM2.5 and a specific biochemical indicator (1-OHP) in urine. Our comprehensive analysis of participant data revealed a robust correlation between PM2.5 and 1-OHP concentrations and distinctly higher levels during the high PM2.5 season compared to the low PM2.5 season. Our research results support Huang, et al.26 Ifegwu, et al.27 observations that indicated a rise in levels of 1-OHP with increased exposure to PAH. We found that a considerable proportion of the subjects in our research had 1-hydroxypyrene (1-OHP) urine levels that were higher than other studies’ guideline limits8. As per Ruiz-Vera, the 95th percentile of non-smoking, non-occupationally exposed persons had a basal level of 0.24 µmol/mol creatinine28, which was mostly related to the absorption of PAHs through diet. Our results, however, show that our research participants’ 1-OHP levels are significantly greater than this basal threshold. Our study’s focus on occupational exposure to PM2.5 makes it clear that workplace conditions greatly impact the higher 1-OHP levels that are seen. Given that many of our participants are general employees, it is possible that occupational exposures other than PM2.5 are responsible for the elevated 1-OHP levels. This is consistent with Ruiz-Vera’s findings, which highlight the significance of considering various occupational sources when determining exposure to PAHs. The possibility that alternative PAH sources in the workplace, alongside PM2.5, could be responsible for the higher 1-OHP levels in our investigation highlights the challenge of accurately measuring exposure in occupational health research.

The experimental group’s results in our study were significantly lower than those reported by Zając et al.29, who found no statistically significant differences related to age or gender and reported an overall geometric mean concentration for urinary 1-hydroxypyrene (1-OHP) in the USA of 74.2 ng/g (CI: 64.1–85.9 ng/g). In a similar vein, our results show that there are no gender or age-related statistically significant changes in 1-OHP levels. This agreement with Zając’s results proves that age and gender do not significantly affect urine 1-OHP levels in some groups.

In the context of assessing PAH exposure, the measurement of urinary 1-hydroxypyrene (1-OHP) stands out as a highly sensitive biomarker. However, some studies have reported conflicting findings regarding using 1-OHP as a biomarker. Leroyer, et al.30 found that both 1-OH-Pyr and 3-hydroxybenzo[a]pyrene (3-OH-B[a]P) may not be the most reliable indicators of PAH exposure in general populations. This may be due to variations in exposure sources, individual metabolic differences, the sensitivity of analytical methods, and the timing of urine sample collection in relation to PAH exposure. Despite this ambiguity, our study supports 1-OHP as a valuable biomarker for PAH exposure. Further research into more accurate indicators of PAH exposure may be beneficial.

Several studies have proven the adverse impact of PM2.5 pollution on the respiratory and cardiovascular systems28,31. In addition to this, the effects of PM2.5 pollution on ocular health are well-documented across several studies. According to several epidemiologic research and controlled human exposure clinical investigations, PM exposure damages the surface of the eyes and produces a range of discomforts32. In the current study, we gathered information during both high and low PM2.5 seasons in order to fully assess the effects of air pollution on ocular health. Using this method, we were able to evaluate the effects of seasonal fluctuations in particulate matter exposure on eye health. We employed 1-hydroxy pyrene (1-OHP) as a biomarker of PM2.5 exposure and determined its levels by analyzing urine samples. According to our research, there is a clear link between PM2.5 exposure and declining ocular health because higher levels of PM2.5 are strongly linked to increased ocular symptoms like redness, watering, and dryness because they showed relatively high odd ratios for both unadjusted and adjusted model. Our findings related to the frequency and severity of symptoms align with Song, et al.33 and Novaes, et al.34 that exposure to PM2.5 is associated with increased severity of dry eye syndrome and ocular allergy, characterized by decreased tear volume, increased corneal irregularity, eyelid edema, mast cell degranulation, and elevated inflammatory cytokines. In addition, analysis of blood samples showed that during the high PM2.5 season, lymphocyte levels were greater. This lymphocytosis is indicative of an immune response to particulate matter exposure and supports the hypothesis that PM2.5 adversely affects ocular health, consistent with previous studies linking air pollution to systemic inflammation35.

Akcay Usta and Icoz36 indicate higher eosinophil counts among hazelnut harvesters. Meanwhile, Atum et al.37 report significantly higher mean NLR, PLR, and neutrophils count in BRVO patients compared to control groups, but we found no such association in our study group.

Although other complete blood count (CBC) measures did not significantly correlate with our findings, other research has documented a variety of hematologic alterations in response to air pollution. For instance, research has shown that populations exposed to high levels of air pollution have changes in red blood cell counts, hemoglobin levels, and platelet counts38,39. Even if our results did not support these conclusions, the lymphocytosis that was shown emphasizes how crucial it is that hematologic reactions be taken into account in any future research that looks into the effects of PM2.5 on human health.

To our knowledge, this study represents the first report utilizing 1-OHP as an exposure biomarker, significantly improving the accuracy in evaluating the impact of PM2.5 on ocular health. Additionally, the inclusion of dual-season data allows for a comprehensive analysis of seasonal variations in exposure and their influence on eye health. These methodological advantages provide a solid foundation for understanding how PM2.5 affects ocular conditions such as ocular allergies and dry eye syndrome. However, it’s vital to acknowledge the limitations of this study. The small sample size could impact the generalizability of our findings. Furthermore, relying on self-reported questionnaires for symptom assessment may introduce bias, potentially affecting the precision of reported symptoms and their severity. These variables should be carefully considered when interpreting the results and devising future research with larger and more diverse populations.

Conclusion

In accordance with our aim to elucidate the effects of PM2.5 on ocular health, we analyzed the association between particulate matter (PM2.5) and various ocular symptoms. Our study’s findings demonstrate significant associations between high PM2.5 exposure and symptoms such as redness, watering, and general discomfort. These results underscore the impact of fine particulate matter on ocular health overall. Thus, our findings suggest that PM2.5 exposure triggers inflammatory responses and disrupts ocular surface stability, leading to increased ocular symptoms.

Acknowledgements

This research was partially supported by Chiang Mai University (No. PM10/2566). The authors thank Ms. Suthathip Wongsrithep from the statistics and data unit at the Research Institute for Health Sciences, Chiang Mai University, for her contribution to the statistical analysis. They also wish to acknowledge the School of Health Sciences Research, Research Institute for Health Sciences, and Chiang Mai University for the student research fund under the CMU Presidential Scholarship, grant number 8393(25)/1688, for facilitating the research work.

Author contributions

Sobia Kausar, Supansa Pata, Woottichai Khamduang, Kriangkrai Chawansuntati, Supachai Yodkeelee, Anurak Wongta, and Surat Hongsibsong conceptualized the study. The data curation and study design involved Surat Hongsibsong, Sumed Yadoung, and Shamsa Sabir. Phanika Tongchai, Woottichai Khamduang, Anurak Wongta, and Surat Hongsibsong interpreted the data. Sobia Kausar prepared the draft manuscript. Surat Hongsibsong and Supansa Pata edited and reviewed it. Sumed Yadoung and Phanika Tongchai coordinated the study. Sobia Kausar and Surat Hongsibsong were responsible for the overall content as guarantors. All authors have read and approved the submitted version of the manuscript.

Data availability

The data used and/or analyzed during the current study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

4/28/2025

The original online version of this Article was revised: The Acknowledgments section in the original version of this Article was incomplete. “This research was partially supported by Chiang Mai University (No. PM10/2566). The authors thank Ms. Suthathip Wongsrithep from the statistics and data unit at the Research Institute for Health Sciences, Chiang Mai University, for partly contributing to the statistics. They also would like to thank the School of Health Sciences Research, Research Institute for Health Sciences, and Chiang Mai University for the student research fund and for facilitating the research work.” It now reads: “This research was partially supported by Chiang Mai University (No. PM10/2566). The authors thank Ms. Suthathip Wongsrithep from the statistics and data unit at the Research Institute for Health Sciences, Chiang Mai University, for her contribution to the statistical analysis. They also wish to acknowledge the School of Health Sciences Research, Research Institute for Health Sciences, and Chiang Mai University for the student research fund under the CMU Presidential Scholarship, grant number 8393(25)/1688, for facilitating the research work.” The original Article has been corrected.

References

- 1.Landrigan, P. J. & Fuller, R. Global health and environmental pollution. Int. J. Public. Health60, 761–762. 10.1007/s00038-015-0706-7 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brucker, N. et al. Biomarkers of occupational exposure to air pollution, inflammation and oxidative damage in taxi drivers. Sci. Total Environ.463–464, 884–893. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.06.098 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Upaphong, P., Thonusin, C., Wanichthanaolan, O., Chattipakorn, N. & Chattipakorn, S. C. Consequences of exposure to particulate matter on the ocular surface: Mechanistic insights from cellular mechanisms to epidemiological findings. Environ. Pollut.345, 123488. 10.1016/j.envpol.2024.12348 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheng, Z. et al. Status and characteristics of ambient PM2.5 pollution in global megacities. Environ. Int.89–90, 212–221. 10.1016/j.envint.2016.02.003 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pisithkul, T., Pisithkul, T. & Lao-Araya, M. Impact of air pollution and allergic status on health- related quality of life among university students in Northern Thailand. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health21. 10.3390/ijerph21040452 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Supasri, T., Gheewala, S. H., Macatangay, R., Chakpor, A. & Sedpho, S. Association between ambient air particulate matter and human health impacts in northern Thailand. Sci. Rep.13 (1), 12753 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jarernwong, K., Gheewala, S. H. & Sampattagul, S. Health impact related to ambient particulate matter exposure as a spatial health risk map case study in Chiang Mai. Thail. Atmos.14, 261 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amnuaylojaroen, T. & Parasin, N. Future health risk assessment of exposure to PM2.5 in different age groups of children in Northern Thailand. Toxics11, 291 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu, D. et al. PM2. 5 exposure increases dry eye disease risks through corneal epithelial inflammation and mitochondrial dysfunctions. Cell Biol. Toxicol.39 (6), 2615–2630 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ruiz-Vera, T. et al. Assessment of vascular function in Mexican women exposed to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons from wood smoke. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol.40, 423–429. 10.1016/j.etap.2015.07.014 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jongeneelen, F. J. A guidance value of 1-hydroxypyrene in urine in view of acceptable occupational exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Toxicol. Lett.231, 239–248. 10.1016/j.toxlet.2014.05.001 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jönsson, L. S. et al. Levels of 1-hydroxypyrene, symptoms and immunologic markers in vulcanization workers in the southern Sweden rubber industries. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health82, 131–137. 10.1007/s00420-008-0310-8 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Oliveira Galvão, M. F. et al. Characterization of the particulate matter and relationship between buccal micronucleus and urinary 1-hydroxypyrene levels among cashew nut roasting workers. Environ. Pollut220, 659–671. 10.1016/j.envpol.2016.10.024 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen, R. et al. Global associations of air pollution and conjunctivitis diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health16, 3652 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Han, J. Y., Kang, B., Eom, Y., Kim, H. M. & Song, J. S. Comparing the effects of Particulate Matter on the ocular surfaces of normal eyes and a dry eye rat model. Cornea36, 605–610. 10.1097/ico.0000000000001171 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mo, Z. et al. Impacts of air pollution on dry eye disease among residents in Hangzhou, China: A case-crossover study. Environ. Pollut246, 183–189. 10.1016/j.envpol.2018.11.109 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chang, C. J., Yang, H. H., Chang, C. A. & Tsai, H. Y. Relationship between air pollution and outpatient visits for nonspecific conjunctivitis. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci.53, 429–433. 10.1167/iovs.11-8253 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anderson, J. O., Thundiyil, J. G. & Stolbach, A. Clearing the air: A review of the effects of particulate matter air pollution on human health. J. Med. Toxicol.8, 166–175 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim, Y., Choi, Y. H., Kim, M. K., Paik, H. J. & Kim, D. H. Different adverse effects of air pollutants on dry eye disease: Ozone, PM2.5, and PM10. Environ. Pollut.265, 115039 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin, C. C. et al. The adverse effects of air pollution on the eye: A review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health19, 1186 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang, X. et al. The association between long-term exposure to ambient fine particulate matter and glaucoma: A nation-wide epidemiological study among Chinese adults. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health238, 113858. 10.1016/j.ijheh.2021.113858 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xuan, S. et al. The Implication of Dendritic Cells in lung Diseases: Immunological role of Toll-like Receptor 4 (Genes & Diseases, 2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Li, M. et al. The effect of air pollution on immunological, antioxidative and hematological parameters, and body condition of eurasian tree sparrows. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf.208, 111755 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.He, L. et al. Oral cavity response to air pollutant exposure and association with pulmonary inflammation and symptoms in asthmatic children. Environ. Res.206, 112275 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Akcay Usta, S. & Icoz, M. Evaluation of ocular surface parameters and systemic inflammatory biomarkers in Hazelnut harvesters. Ocul Immunol. Inflamm. 1–6. 10.1080/09273948.2024.2336598 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Sutan, K., Naksen, W. & Prapamontol, T. A simple high-performance liquid chromatography coupled to fluorescence detection method using column-switching technique for measuring urinary 1-hydroxypyrene from environmental exposure. Tandem 15, 16 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chetiyanukornkul, T., Toriba, A., Kameda, T., Tang, N. & Hayakawa, K. Simultaneous determination of urinary hydroxylated metabolites of naphthalene, fluorene, phenanthrene, fluoranthene and pyrene as multiple biomarkers of exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Anal. Bioanal Chem.386, 712–718. 10.1007/s00216-006-0628-6 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kahe, D. et al. Effect of PM2. 5 exposure on adhesion molecules and systemic nitric oxide in healthy adults: The role of metals, PAHs, and oxidative potential. Chemosphere354, 141631 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang, Y. et al. A preliminary study on household air pollution exposure and health-related factors among rural housewives in Gansu Province, northwest China. Arch. Environ. Occup. Health77, 662–673. 10.1080/19338244.2021.1993775 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ifegwu, C. et al. Urinary 1-hydroxypyrene as a biomarker to carcinogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon exposure. Biomark. Cancer4, 7–17. 10.4137/bic.S10065 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guaita, R., Pichiule, M., Maté, T., Linares, C. & Díaz, J. Short-term impact of particulate matter (PM2. 5) on respiratory mortality in Madrid. Int. J. Environ. Health Res.21, 260–274 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zając, J., Gomółka, E. & Szot, W. Urinary 1-hydroxypyrene in occupationally-exposed and non-exposed individuals in Silesia, Poland. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med.25, 625–629. 10.26444/aaem/75940 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leroyer, A. et al. 1-Hydroxypyrene and 3-hydroxybenzo[a]pyrene as biomarkers of exposure to PAH in various environmental exposure situations. Sci. Total Environ.408, 1166–1173. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2009.10.073 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jalali, S. et al. Long-term exposure to PM 2.5 and cardiovascular disease incidence and mortality in an Eastern Mediterranean country: Findings based on a 15-year cohort study. Environ. Health20, 1–16 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang, Q. et al. Effects of fine particulate matter on the ocular surface: An in vitro and in vivo study. Biomed. Pharmacother.117, 109177 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Song, S. J. et al. New application for assessment of dry eye syndrome induced by particulate matter exposure. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf.205, 111125 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Novaes, P. et al. The effects of chronic exposure to traffic derived air pollution on the ocular surface. Environ. Res.110, 372–374 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Künzli, N. et al. Ambient air pollution and atherosclerosis in Los Angeles. Environ. Health Perspect.113, 201–206 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Akcay Usta, S. & Icoz, M. Evaluation of ocular surface parameters and systemic inflammatory biomarkers in Hazelnut harvesters. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 1–6 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Atum, M. et al. Association of neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio, platelet/lymphocyte ratio and brachial retinal vein occlusion (2019).

- 41.Liao, D. et al. Association of higher levels of ambient criteria pollutants with impaired cardiac autonomic control: A population-based study. Am. J. Epidemiol.159, 768–777 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chuang, K. J., Chan, C. C., Su, T. C., Lee, C. T. & Tang, C. S. The effect of urban air pollution on inflammation, oxidative stress, coagulation, and autonomic dysfunction in young adults. Am. J. Respir. Crit Care Med.176, 370–376 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used and/or analyzed during the current study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.