Abstract

In citrus, the synthetic auxin 3,5,6-trichloro-2-pyridyloxyacetic acid (3,5,6-TPA), applied as a foliar spray at a concentration of 15 mg l− 1 during physiological fruitlet abscission, caused additional fruitlet drop and reduced the number of fruits reaching maturity. The effect was much more pronounced at full physiological abscission than after. In this study, this thinning effect was successfully exploited for the first time in sour orange trees grown in an urban environment, reducing harvesting costs by up to almost 40%. This effect is mediated by the leaves, which alter their photosynthetic activity. Our results show a reduction of carbon fixation and sucrose synthesis in the leaf, by 3,5,6-TPA repression of the RbcS, SUS1 and SUSA genes, its transport to the fruit, as shown by the reduced expression of the sucrose transporter genes SUT3 and SUT4, and its hydrolysis in the fruit, mainly by repression of the SUS1 gene expression. Genes involved in auxin homeostasis in the fruit, TRN2 and PIN1, were also repressed. The coordinated repression of all these genes is consistent with the decrease in the fruit cell division rate, as shown by the repression of CYCA1-1 gene, leading to the production of ethylene, which ultimately induces fruitlet abscission.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-78310-9.

Keywords: Citrus, Sour orange, Urban environment, Synthetic auxin, Thinning, Harvesting costs

Subject terms: Auxin, Agricultural genetics

Introduction

In citrus, minimum fruit size is required for marketing and is a determinant for price. It can be increased directly by increasing cell enlargement or indirectly by reducing competition between fruitlets through thinning. Both effects can be achieved by the application of synthetic auxins and depend on timing and concentration, the most effective auxin being 3,5,6-trichloro-2-pyridyloxyacetic acid (3,5,6-TPA; free acid) when applied at a concentration of 15 mg l− 11–3.

Increasing final size by promoting cell enlargement is a highly effective technique. This is achieved by applying auxin just after the physiological fruitlet abscission1,4,5 and does not alter the number of fruits harvested. However, when applied during the physiological fruitlet abscission it acts as a powerful fruit thinner, inducing intense fruitlet drop1, which increases the size of the remaining fruits on the tree by reducing their competition for carbohydrates6. However, to be effective it must affect at least 60% of the fruits7, which significantly reduces yield.

Therefore, fruit thinning is not the most widely used technique in citriculture to increase final fruit size. However, in some specific cases, such as ornamental citrus, fruit thinning can be of great interest. For example, sour orange trees (Citrus aurantium L.), growing in the gardens and streets of large cities, pose serious management problems, particularly at harvest time. Harvesting is difficult because most of the trees are isolated, both in gardens and roundabouts, and in long rows along pavements. Besides, because their ornamental nature, sour oranges are typically harvested when they reach full maturity and develop a bright orange colour. All this leads to serious inconveniences, as harvesting cannot take place quickly as soon as the fruit is ripe, and the delay causes the fruit to fall, filling the pavements and lanes with fruit that stains the streets, rots, gives off bad odours, etc. It also requires a lot of labour, which significantly increases maintenance costs. Thinning a large number of developing fruitlets would therefore make them much easier to manage and could reduce maintenance and care costs.

However, although the thinning effect of synthetic auxins has been studied extensively, it is not yet fully understood. It is known from a nutritional8–12, hormonal11–15, agronomic1, and genetic perspective (see review by Costa et al., 2019 and references therein)16–18.

With regard to nutritional factors, the propensity of fruitlets to abscise has been correlated with sugar availability in both deciduous species, such as apple19, cherry20, pistachio21, and evergreen species, such as citrus9,10,22, for which the leaves are a carbohydrate store. In citrus, treatments that increase (branch scoring) or decrease (pedicel girdling) photoassimilate availability reduce or increase ethylene production and fruitlet abscission, respectively23,24. The authors suggested that carbon shortage during fruit set acts as a signal that triggers a hormonal sequence involving ethylene biosynthesis, which controls fruitlet abscission and adjusts the number of developing fruitlets to sugar availability6,9,10,22.

Similarly, the application of the synthetic auxin 3,5,6-TPA impairs temporally photosynthetic activity. This phytotoxic effect reduces photosynthate production and supply to the fruitlet, which reduces growth rate, triggers ethylene production and leads to abscission12.

This paper examines the molecular mechanisms underlying the synthetic auxin-induced abscission of fruitlets, thereby contributing to the understanding of the synthetic auxin 3,5,6-TPA action in this process and the sequence of endogenous events in Citrus. Additionally, it considers the potential of this synthetic auxin as a fruit thinner for sour orange trees, which are cultivated for ornamental purposes in urban environments to reduce harvesting costs.

Materials and methods

Plant material, experimental design, treatments and evaluations

Experiments were carried out on 18–20 year old ‘Seville’ sour orange trees (C. aurantium L.) grown in two gardens in Castellón, Spain (39º59’N; 00º03’W), 800 m apart (Garden I and II). The trees were trained to an upright vase shape with a single clear trunk, planted at 5 m x 5 m spacing, with drip irrigation. Fertilization, pruning, and pest management, were in accordance with normal commercial practices. The auxin 3,5,6-trichloro-2-pyridyloxyacetic acid (3,5,6-TPA) as free acid (Maxim, 10% 3,5,6-TPA w/w; Arysta LifeScience Benelux) at a concentration of 15 mg l− 1 was sprayed with a hand gun at a pressure of 25–30 atm, wetting the trees to the point of run-off. A non-ionic wetting agent (alkyl polyglycol ether, 20% w/v) was added at a rate of 0.05% v/v. To determine the appropriate date of treatment, 3,5,6-TPA was sprayed at full physiological fruitlet abscission (16 May 2022) and 15 days later (31 May 2022). Treatment was carried out between 7 and 10 a.m. on both dates. A randomised complete block design with single tree plots of 10 replications each was performed.

At 3, 8 and 20 days after treatment (dat), dropped fruits were counted from all trees and 10 fruits were randomly collected from 3 randomly selected trees from each treatment, frozen in liquid N and transferred to the laboratory for further genetic analysis. At maturity, yield was assessed by counting the number of fruits per m2 canopy of all trees.

In 2023, the treatment was repeated in a university orchard in Valencia (39º29’N; 00º32’W), but only 5 trees were treated at full physiological fruitlet abscission (mid-May) and 5 trees were left untreated to serve as controls. At 24 h and at 5, 9 and 15 dat, one leaf per shoot was collected from 5 randomly selected uni-fruiting mixed shoots per tree, and at 24 h and at 2, 3, 9 and 20 dat, fruit was collected from a further 5 randomly selected uni-fruiting mixed shoots per tree. Leaves and fruits were frozen in liquid N, transported to the lab and stored at -80ºC for further gene expression analysis.

In a separate experiment, leaves and fruits of uni-fruiting mixed shoots from 6 trees were treated locally with the same auxin at the same concentration and date as follows. Forty-five of these shoots per tree were randomly selected, and the leaves of 15 shoots and the fruits of a further 15 shoots were treated, while the remaining 15 shoots were left untreated as controls. On 3 trees, 10 dat fruits were harvested from 5 shoots per treatment to assess their ethylene production, and on the 10 remaining shoots, fruit diameter was measured every 5 days during the 20 dat to determine growth rate. On the other 3 trees, shoots that had lost fruit were counted at 25 dat.

Fifteen days after treatment, chlorophyll content was measured in 15 randomly selected uni-fruiting mixed shoots per tree using a SPAD-502 chlorophyll meter (Minolta Corp., NJ, USA), with results expressed in relative units (SPAD values).

Gene expression analysis

Total RNA was isolated from three frozen biological replicates per treatment using phenol reagent as described above. All procedures were carried out on ice with centrifugation steps at 4 °C, and all reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich®. Approximately 500 mg of fresh tissue (leaf and fruit) was ground to a fine powder using a pre-chilled mortar and samples were stored in RNase-free plastic tubes pre-cooled in liquid nitrogen. The lysis/binding buffer (0.2 M TrisBase, 0.2 M sodium chloride, 50 mM ethylendiaminetetraacetic acid trisodium salt hydrate, 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate in DEPC-treated water), phenol solution and β-mercaptoethanol were added to each tube and gently homogenised. The tubes were then incubated at 50ºC for 20 min and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 15 min. The aqueous phase was pipetted into new tubes and an equal volume of (24:1) chloroform: isoamyl alcohol was added, mixed thoroughly and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 20 min. The supernatant was transferred to a fresh tube, 6 M lithium chloride was added and incubated overnight at -20ºC to precipitate the RNA. The tubes were centrifuged at 11,000 rpm for 10 min and the supernatants removed, leaving only the RNA pellet. The pellets were washed with 70% ethanol and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 5 min. The ethanol was then discarded and the RNA pellets were air-dried at room temperature for 2–3 min and resuspended in RNase-free water by passing the solution up and down a pipette tip several times.

We tested the RNA quality with a Nanodrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer, using the OD260/OD280 ratio, and gel electrophoresis. The PrimeScript™ RT Reagent Kit (Perfect Real Time Takara, Japan) was used to produce cDNA from 1 µg total RNA. And, finally, we carried out the quantitative real-time PCR with the TB Green® Premix Ex Taq™ Kit (Takara, Japan) on a Rotor Gene Q 5-Plex (Qiagen, USA). The PCR mix contained a 4-fold cDNA dilution (2.5 µl), 0.3 µM primers, QuantiTect® SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (12.5 µl) (Takara, Japan), having a final volume of 25 µl. Amplification consisted of a pre-incubation of 15 min at 95ºC, denaturation during 40 cycles of 15 s at 94 ºC, 30 s at 60 ºC for annealing and 30 s at 72 ºC for extension. ACTIN was selected as a control reference gene to normalise expression levels. SUT1, SUT2, SUT3 and SUT4 primers were described in25,26. CYCA1-1 and RbcS (Rubisco small subunit) primers were described in27,28, respectively. SUS1 and SUSA primers were described in29 and the PIN1 primer (citrus sequence: Cs2g16620) was described in30. Finally, the Phytozome v13 database (www.phytozome.net) was used to check these sequences and to obtain the Arabidopsis thaliana orthologs genes for citrus: CWIN and TRN2. Primers were designed using Primer 3 v4.1.0 software (http://primer3.ut.ee/). The sequences of the primers are provided in Supplementary Table S1. Relative gene expression levels were determined using the 2-ΔCt method.

Ethylene analysis

Ethylene production was determined by incubating 3 replicates of 10 fruits each into 1 L flasks that were hermetically sealed and maintained at the room temperature. After 3 h of incubation, 1 mL of air samples from the headspace of the flasks was withdrawn with a hypodermic syringe and injected into a gas chromatograph (Perkin Elmer Autosample) equipped with a flame ionization detector and an activated alumina column. Nitrogen was used as carrier gas, and the temperature of the column was maintained at 140 ℃. Results were expressed as nl FW g− 1 and h− 1.

Statistical analysis

Analysis of variance was performed on the data, using the Student–Newman–Keuls’ multiple-range test for means separation. Percentages were transformed to arcsin to homogenise the variance. STATGRAPHICS Centurion XVI software (Statistical Graphics, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA) was used to analyse the data.

Results

Use of 3,5,6-TPA for fruitlet abscission in garden citrus.

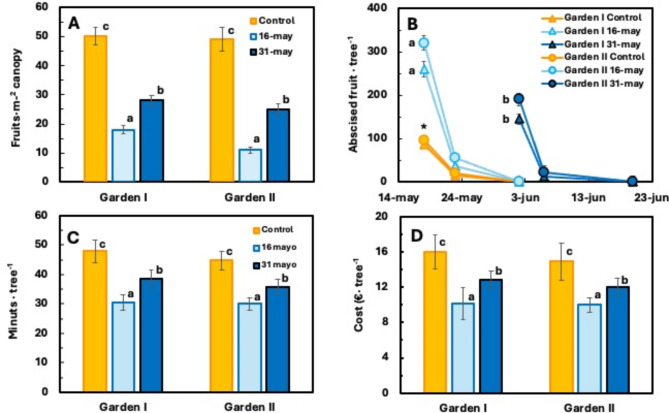

In garden-grown ‘Seville’ sour orange trees, 3,5,6-TPA applied at a concentration of 15 mg l− 1 during physiological fruitlet abscission reduced the number of fruits at harvest. In Gardens I and II, the number of fruits per m2 of leaf canopy decreased from 50 and 49 in the untreated trees to 18 and 11 in the trees treated at full physiological abscission (16 May) and to 28 and 25 in the trees treated 15 days later (31 May), respectively (Fig. 1A). Thus, 2 days after treatment, in trees treated during full physiological fruitlet drop, abscission was more than 260 and 320 fruits per tree in Garden I and II, respectively, whereas in those treated 15 days later, it barely exceeded 145 and 190 fruits, respectively (P < 0.05; Fig. 1B). One week later, the number of abscised fruits per tree was significantly lower (P < 0.05), 37 and 55 fruits for the first treatment day and 13 and 23 fruits for the second treatment day, respectively. Fruit drop in the control trees was significantly lower (P < 0.05), with 90–95 and 15–20 fruits per tree on the two evaluation days for the two trials, with no significant differences between them (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Effect of treatment date with 15 mg l− 1 3,5,6-TPA on final yield (A), fruitlet abscission (B), harvesting time (C) and harvesting cost (D) of ‘Seville’ sour orange trees in two urban gardens 800 m apart. The values of A, C and D correspond to Garden I. Each value is the mean of 10 trees. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences (P < 0.05). B values are for the two Gardens, and different letters indicate statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) between treatment days. * indicates significant difference between control and treated trees (P < 0.05). Standard errors are given as vertical bars.

This reduction in the number of fruits resulted in a reduction in harvesting time. In Garden I, an average of 10 trees per day per worker were harvested from untreated control trees, whereas 15.8 trees were harvested from trees treated at full physiological drop. Harvesting times were 48 and 31 min per tree and costs were 10.1 and 12.8 € per tree, respectively. The delay in treatment, 15 d later, resulted in a loss of efficacy. The number of trees harvested per day per worker was 12.5, with an average harvesting time of 39 min per tree and a harvesting cost of €16.0 (Fig. 1C, D). Overall, for all treated trees, the first treatment saved 36.7% of the harvesting costs and the second treatment saved 20.0%. There were no significant differences between the gardens.

The abscission effect of the synthetic auxin 3,5,6-TPA

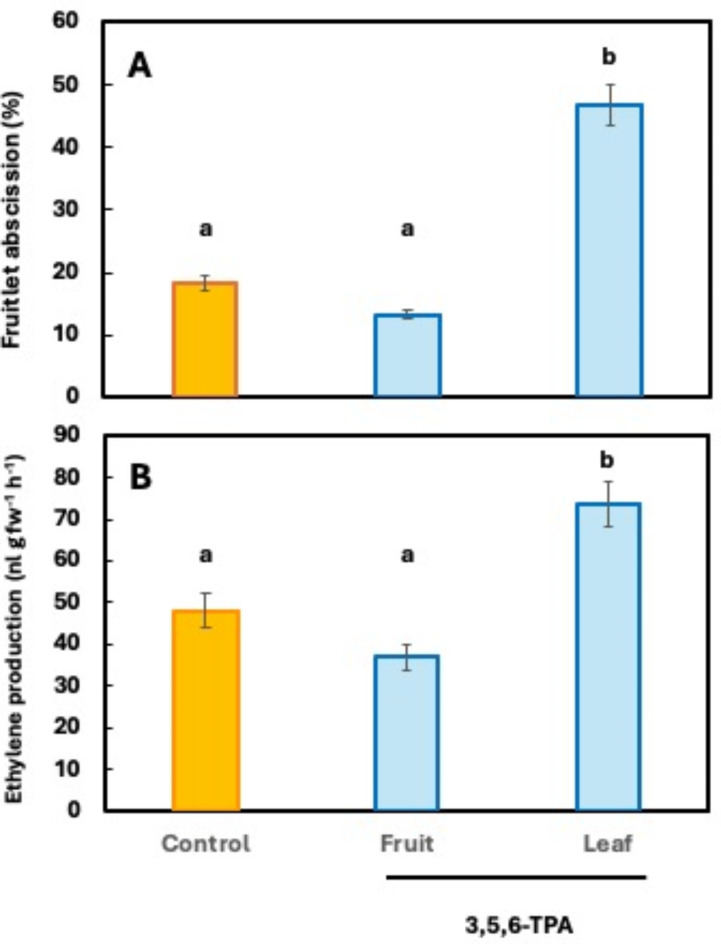

The abscission effect of the synthetic auxin 3,5,6-TPA is mediated by the leaf. Local application of 3,5,6-TPA to the leaves of fruiting shoots resulted in almost 50% abscission of fruitlets, whereas when applied only to the fruit, the percentage of abscission was barely 13% and was not statistically different from untreated controls (18%) (Fig. 2A). Fifteen days after treatment, this correlated with a reduction in chlorophyll content of the treated leaves, 15% lower, measured in SPAD units (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Fig. 2.

Effect of the application of 15 mg l− 1 3,5,6-TPA on the abscission of fruits of single-fruiting mixed shoots of ‘Seville’ sour orange treated only on the fruit, only on the leaves and untreated (control) (A) and on fruit ethylene production (B). Abscission values correspond to 25 dat and ethylene to 10 dat. Each value is the mean of 6 trees and 15 shoots per tree (A) and of 3 biological replicates of 5 fruits and 3 analytical determinations each (B). Standard errors are given as vertical bars. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences (P < 0.05).

Fruit drop was accompanied by ethylene production, which was 53–55% higher in fruit from shoots with treated leaves than in fruit from shoots with treated fruit and control shoots (Fig. 2B).

Molecular characterisation of the abscission mechanism

The effect of the auxin on leaf chlorophyll content was accompanied by a reduction in the expression of the small subunit of the enzyme RuBisCo. Indeed, 5 days after treatment (dat), the expression of the RbcS (Rubisco small subunit) gene coding for its biosynthesis was significantly repressed by auxin (P < 0.05), reaching a maximum difference 4 days later (9 dat) (Fig. 3A), coinciding with the maximum difference in fruit growth rate compared to untreated controls (see Fig. 6B); although the effect diminished over time, it persisted until at least 15 dat (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

Time-course of the Rubisco small subunit, RbcS, and SUCROSE SYNTHASE, SUS1 and SUSA, genes expression in leaves of ‘Seville’ sour orange following application of 15 mg l− 1 of 3,5,6-TPA. Standard errors are given as vertical bars. * indicates statistically significant difference (P < 0.05). Values are the mean of 3 biological replicates and 3 analytical determinations each. In some cases, the standard error is smaller than the symbol.

Fig. 4.

Time-course of the SUCROSE TRANSPORTERs SUT1, SUT2, SUT3 and SUT4 genes expression in leaves of ‘Seville’ sour orange following application of 15 mg l− 1 of 3,5,6-TPA. Standard errors are given as vertical bars. * indicates statistically significant difference (P < 0.05). Values are the mean of 3 biological replicates and 3 analytical determinations each. In some cases, the standard error is smaller than the symbol.

The reduction in CO2 fixation led to reduced carbohydrate biosynthesis. Sucrose, the main transported sugar in citrus, was particularly affected. The availability of the enzyme sucrose synthase was significantly reduced (P < 0.05) by the action of 3,5,6-TPA, as evidenced by the lower expression of the SUS1 and SUSA genes. The effect was still present 15 dat (Fig. 3B, C).

This reduction in the sucrose synthase enzyme correlated with a consistent and significant reduction (P < 0.05) in the expression of the SUCROSE TRANSPORTER genes SUT3 and SUT4 over the following 5 dat, whereas SUT1 and SUT2 were little changed and remained at constitutive levels (Fig. 4). Sucrose is transported via the phloem from its source, the leaf, to the sink, the fruit, where it is unloaded to enter the cells, either apoplastically or symplastically.

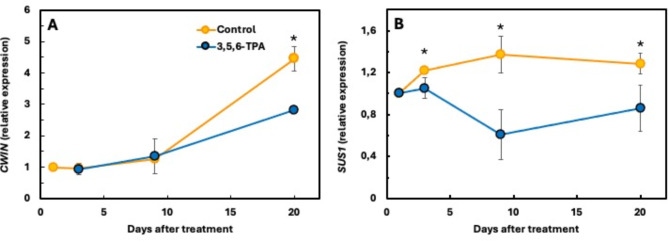

Fig. 5.

Time-course of the CELL WALL INVERTASE, CWIN, and CYTOPLASMIC INVERTASE, SUS1, genes expression in fruits of ‘Seville’ sour orange following application of 15 mg l− 1 of 3,5,6-TPA. Standard errors are given as vertical bars. * indicates statistically significant difference (P < 0.05). Values are the mean of 3 biological replicates and 3 analytical determinations each. In some cases, the standard error is smaller than the symbol.

Once in the apoplast, cell wall invertase can hydrolyse sucrose to fructose and glucose, which are transported into the cell. This pathway is initially unaltered by 3,5,6-TPA, as the gene encoding the invertase, CWIN, reduces the expression 20 dat (P < 0.05) (Fig. 5A). However, sucrose that enters the cytoplasm symplastically, via specific transporters or via plasmodesmata, is immediately hydrolysed for consumption by the action of SUS1. This gene, considered to be the main factor responsible for the accumulation of hexoses in the fruit cells, is markedly altered by 3,5,6-TPA, its expression being significantly lower (P < 0.05) in the fruits of treated trees than in those of untreated trees (Fig. 5B). The effect is detectable 3 dat, the difference is maximal 9 dat and lasts for at least 20 days.

Fig. 6.

Time-course of the mitotic cyclin gene expression, CYCA1-1, in fruits of ‘Seville’ sour orange following application of 15 mg l− 1 of 3,5,6-TPA (A), and time-course of growth rate of fruits from single-fruiting mixed shoots treated only on the fruit, only on the leaves and untreated (control) (B). Standard errors are given as vertical bars. * and different letters indicate statistically significant differences (P < 0.05). Gene expression values are the mean of 3 biological replicates and 3 analytical determinations each, and growth rate values are the mean of 3 trees and 10 fruits per tree. In some cases, the standard error is smaller than the symbol.

This hexose deficit in the fruit cells of the treated trees leads to a reduction in cell division, as shown by the repression of the CYCA1-1 gene. Statistical significance (P < 0.05) is reached at 3 dat and remains practically stationary during the 9 dat (Fig. 6A), the period of greater fruitlet abscission (see Fig. 1B).

This effect coincides in time with a reduction in fruit growth rate. Furthermore, as the action of auxin is mainly through the leaves (see Fig. 2A), the fruits on shoots where leaves were treated individually grew more slowly during the 20 days following treatment than those on shoots where fruits were treated individually or where neither leaves nor fruits were treated (control) (Fig. 6B).

Effect of 3,5,6-TPA on auxin homeostasis in treated fruit

Nine days after treatment, the expression of the plasma membrane-localized TORNADO 2 gene (TRN2), which modulates auxin homeostasis, was significantly lower (P < 0.05) in fruits from trees treated with 3,5,6-TPA than in control fruits (Fig. 7A).

Fig. 7.

Time-course of TORNADO2, TRN2 (A), and PIN-FORMED 3, PIN1 (B), genes expression in fruits of ‘Seville’ sour orange following application of 15 mg l− 1 of 3,5,6-TPA. Standard errors are given as vertical bars. * Indicates statistically significant difference (P < 0.05). Values are the mean of 3 biological replicates and 3 analytical determinations each. In some cases, the standard error is so small that the bar is not visible.

At the same time, the efflux of auxin from the fruit through the pedicel was also reduced by the action of 3,5,6-TPA. This is evidenced by the significantly lower expression (P < 0.05) of the PIN-FORMED 1 (PIN1) gene, which encodes transmembrane proteins involved in intercellular auxin flux (Fig. 7B).

Discussion

Activation of cell division in the ovary is an essential factor in fruit set31. This process is regulated by the ability of the ovule to synthesise gibberellins after fertilisation, which is stimulated by auxin32,33. In the absence of fertilisation, the ovary walls are responsible for their synthesis34. The influence of gibberellins on the fruit setting process in citrus has been demonstrated in both self-compatible and parthenocarpic varieties35,36, mediated by their ability to promote cell division in ovary tissues34.

This ability for cell division requires the supply of carbohydrates to the developing ovary8. Therefore, in citrus, flowers on leafy shoots set fruit in a higher rate than those on leafless shoots37,38, which has been linked to the greater carbohydrates supply received by the former39. In addition, competition for carbohydrates among developing flowers40 and between flowers and young leaves22,41 are determinants of fruit set6, and this dependence persists until the onset of physiological fruit drop, when most ovaries exhibit a high rate of cell division and respiration42. Furthermore, if carbohydrate supply is restricted during this period, the ovaries abscise, with the intensity of abscission increasing as the restriction increases9. Although this can have a negative effect on yield, it can lead to an improvement in fruit size1. Synthetic auxins applied during the cell division can be used for this purpose.

Synthetic auxins, such as 3,5,6-TPA, induce photosynthetic damage through leaf chlorosis11, which is consistent with the low SPAD values found in our experiments. This photosynthetic damage: (1) reduces the effective quantum yield of photosystem II (ΦPSII), (2) reduces photochemical quenching (qP), which indicates the proportion of open reaction centres of photosystem II (PSII), i.e. the energy used in photosynthesis, (3) increases non-photochemical quenching (qN), which indicates the rate of thermal dissipation of excess energy in PSII, and (4) reduces CO2 assimilation12. Similarly, in apple trees, naphthalene acetic acid (NAA) promotes effective fruit thinning by reducing CO2 assimilation and photosynthesis and increasing dark respiration43. Therefore, fruit abscission is due to the effect of auxin on photosynthetic performance, leading to a decrease in leaf carbohydrate concentration44. In citrus, the decrease in PSII electron transport caused by 3,5,6-TPA phytotoxic stress has been shown not to be associated with damage to the photosynthetic apparatus, but rather with a process that can be reversed once the stress is overcome11,12.

In our study, the low CO2 fixation caused by the application of 3,5,6-TPA is explained by the repression of the RbcS gene in treated leaves, which strongly affects the overall catalytic efficiency of the Rubisco complex45. In addition, due to the reduction in substrates for sucrose synthesis, the genes involved in its synthesis, SUS1 and SUSA, are also repressed46,47. Thus, the sucrose content should be lower in both mature and young leaves and in leaves of vegetative and fruit-bearing shoots of treated trees compared to control trees, with differences appearing within a few days of treatment, 5 d in our sour orange experiments and 3 d in the Clementine mandarin experiments12. Consequently, the transport of sucrose to sink organs is also reduced by auxin, as shown by the significantly reduced expression (P < 0.05) of the sucrose transporter genes SUT3 and SUT446,47. The expression of the SUT1 and SUT2 genes must be constitutive and, therefore, there are no significant differences between the leaves of treated and control trees.

As a result, the sucrose content in the fruit of treated trees decreases12, as does its hydrolysis. Indeed, 24 h after treatment, the expression of the SUS1 invertase gene in the fruit was significantly reduced (P < 0.05) in fruits from treated trees; the difference became much more pronounced after 5 d, as was the case with the expression of transport genes. Although it has been noted that the invertase SUS1 has limited relevance in hexose accumulation and that SUS3 is more closely related to the accumulation of glucose and fructose in the initial stages of fruit development48, high expression of SUS1 has been demonstrated in Clementine mandarin during the 40 d following anthesis49. However, the cell wall invertase CWIN gene did not reduce its expression until 20 d after treatment, suggesting that sugar unloading in the fruit during the early stages of development must occur symplastically47,48.

Paralleling this reduction in carbohydrate loading in the fruit, there was a decrease in its growth rate, which is probably the reason for the increase in its abscission rate and, therefore, the thinning1,8,11. The fact that this effect is more pronounced when leaves are treated than when fruits are treated supports the hypothesis that it is a consequence of the phytotoxic effect of auxin on photosynthetic activity.

The mechanism by which a synthetic auxin induces fruitlet thinning has been correlated with an increase in fruit ethylene production11,12,14,24. This is due to a reduction in the basipetal transport of indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) along the peduncle50,51. IAA is essential for vascular tissues differentiation52, and synthetic auxins have been shown to promote the development of these tissues in the peduncle when applied locally to it53. PIN proteins exhibit polar subcellular localization, which determine the direction of intercellular auxin flow within a specific tissue or organ, either towards or against an auxin gradient54,55. Exogenous auxin application is sufficient to elicit changes in the direction of an auxin-induced PIN relocalization56, in a similar way as shown in our experiment for 3,5,6-TPA, which 9 dat reduced the expression of the PIN1 gene, i.e. IAA efflux towards the peduncle. The treatment also reduced the expression of the TRN2 gene in the fruit; a correlation between the expression of these two genes has also been found in the carpel primordia during flower development in Arabidopsis57. Both effects resulted in the abscission layer being unprotected and the vascular bundles losing their transport capacity, causing fruitlet drop. This is consistent with the effect of branch girdling during the physiological fruitlet abscission, which increases PIN1 expression in the fruitlet, protecting the abscission layer and allowing it to continue to be nourished, thus preventing its drop27.

This reduction in TRN2 and PIN1 expression in our experiment is consistent with the reduction in fruit carbohydrate content reported by12 at 8 dat and consequently with the reduction in cell division rate, i.e. the repression of CYCA1-1.The reduction in basipetal indol-3-acetic acid transport through the pedicel has been correlated with an increase in fruitlet ethylene production15,50 and has been linked to the manner in which synthetic auxins thin developing citrus fruitlets10–13,24.

In this study, the effect of 3,5,6-TPA on fruitlet drop has been successfully exploited for the first time in a seedy cultivar, sour orange trees, in gardening. The effectiveness of the treatment, as in parthenocarpic species/varieties in commercial cultivation, depends on the time of application, being highest during full physiological fruitlet drop, when cell division and carbohydrate demand are maximal, and decreasing with time1. Accordingly, there was a significant reduction (P < 0.05) in the number of fruits to be harvested, particularly at the first treatment date, thus reducing harvesting costs. However, it is interesting to note that at the time of the second day of treatment (31 May) the abscission of the fruits of the control trees and also of the first treated trees is complete (see Fig. 1B), but nevertheless 3,5,6-TPA can still promote the abscission of the remaining actively growing fruits, i.e. those in the phase of dividing cells. This indicates that some of them have overcome the competition for carbohydrates but remain sensitive to auxin. It also shows that competition is indeed a cause of abscission6,41.

It should be noted that the presence of fruits is a strong inhibitor of flowering in fruit trees58–60, including citrus61. In this study, the reduction in the number of fruits that reached maturity allowed for intense flowering the following year, which is desirable for ornamental trees that should look in streets and gardens during the bloom season. In addition, considering that this is a sexually set species that requires pollination, the production in the following year after treatment was abundant. Therefore, the proposed treatment with the synthetic auxin 3,5,6-TPA should be carried out annually if one wishes to maintain the savings achieved and to ensure proper annual flowering.

In summary, the abscission effect of the synthetic auxin 3,5,6-TPA can be used in horticulture to reduce the yield of citrus trees and consequently the cost of harvesting. In treated trees, the chlorophyll content and photosynthetic activity of the leaves are reduced by this auxin. The molecular study shows a reduction in sucrose synthesis in the leaf, its transport to the fruit and its hydrolysis in the fruit, leading to a reduction in the rate of cell division, which correlates with an increase in ethylene production in the fruit, leading to fruitlet abscission.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank to Raúl Aznar for his technical assistance.

Author contributions

M.A. planned and designed the research; C.R. and A.M. performed experiments and conducted the fieldwork; A.M-F. and A.M. carried out biochemical analyses; M.A., C.R. and C.M. analysed the data; and M.A. wrote the manuscript.

Data availability

The data from this work cannot be shared openly because it is part of a study whose privacy we must protect. However, all experimental results analysed in this study are available on request at magusti@prv.upv.es.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Permissions and licenses

The C. aurantium L. collection belongs to Universitat Politècnica de València, Spain, and no permissions or licenses are required to collect the material.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Agustí, M., El-Otmani, M., Aznar, M., Juan, M. & Almela, V. Effect of 3, 5, 6-trichloro-2-pyridyloxyacetic acid on clementine early fruitlet development and on fruit size at maturity. J. Hortic. Sci.70, 955–962 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agustí, M., Almela, V., Zaragoza, S., Primo-Millo, E. & El-Otmani, M. Recent findings on the mechanism of action of the synthetic auxins used to improve fruit size in citrus. Proc. Int. Soc. Citriculture2, 922–928 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agustí, M., Martínez-Fuentes, A. & Mesejo, C. Citrus fruit quality. Physiological basis and techniques of improvement. Agrociencia VI nº2, 1–6 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agustí, M., Almela, V., Aznar, M., El-Otmani, M. & Pons, J. Satsuma mandarin fruit size increased by 2, 4-DP. Hortic. Sci.29, 279–281 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- 5.El-Otmani, M., Agustí, M., Aznar, M. & Almela, V. Improving the size of ‘Fortune’ mandarin fruits by the auxin 2, 4-DP. Sci. Horti55, 283–290 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agustí, M., García-Marí, F. & Guardiola, J. L. The influence of flowering intensity on the shedding of reproductive structures in sweet orange. Sci. Hortic.17, 343–352 (1982). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zaragoza, S., Trenor, I., Alonso, E., Primo-Millo, E. & Agustí, M. Treatments to increase the final fruit size on satsuma Clausellina. Proc. Int. Soc. Citriculture2, 725–728 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mauk, C. S., Bausher, M. G. & Yelenosky, G. Influence of growth regulator treatments on dry matter production, fruit abscission, and 14 C-assimilate partitioning in Citrus. J. Plant. Growth Regul.5, 111–120 (1986). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mehouachi, J. et al. Defoliation increases fruit abscission and reduces carbohydrate levels in developing fruits and woody tissues of Citrus Unshiu. Plant. Sci.107, 189–197 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iglesias, D. J., Tadeo, F. R., Primo-Millo, E. & Talón M. Carbohydrate and ethylene levels related to fruitlet drop through abscission zone A in citrus. Trees20, 348–355 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agustí, M., Juan, M. & Almela, V. Response of ‘Clausellina’ Satsuma mandarin to 3,5,6 trichloro-2-pirydiloxyacetic acid and fruitlet abscission. Plant. Growth Regul.53, 129–135 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mesejo, C., Rosito, S., Reig, C., Martínez-Fuentes, A. & Agustí, M. Synthetic auxin 3,5,6-TPA provokes Citrus clementina (Hort. Ex Tan) fruitlet abscission by reducing photosynthate availability. J. Plant. Growth Regul.31, 186–194 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iwahori, S. & Oohata, J. T. Chemical thinning of ‘Satsuma’ mandarin (Citrus Unshiu Marc.) Fruit by 1 naphthalene acetic acid: Role of ethylene and cellulase. Sci. Hortic.4, 167–174 (1976). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirose, K. Development of chemical thinners for commercial use for Satsuma mandarin in Japan. Proc. Int. Soc. Citriculture1, 256–260 (1981). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Okuda, H. & Hirabayashi, T. Effect of IAA gradient between the peduncle and branch on physiological drop of citrus fruit (Kiyomi Tangor). J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol.73, 618–621 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Costa, G., Botton, A. & Vizzotto, G. Fruit thinning: Advances and trends. Hortic. Rev.46, 185–226 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Devoghalaere, F. et al. A genomic approach to understanding the role of auxin in apple (Malus x Domestica) fruit size control. Plan. Biol.12, 7 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eccher, G., Begheldo, M., Boschetti, A., Ruperti, B. & Botton, A. Role of ethylene production and ethylene.receptor expression in regulating apple fruitlet abscission. Plant. Physiol.169, 125–137 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berüter, J. & Droz, P. H. Studies on locating the signal for fruit abscission in the apple tree. Sci. Hortic.46, 201–214 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Atkinson, C. J., Else, M. A., Stankiewicz, A. & Webster, A. D. The effects of phloem girdling on the abscission of Prunus avium L. fruits. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol.77, 22–27 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nzima, M. D. S., Martin, G. C. & Nishijima, C. Effect of fall defoliation and spring shading on shoot carbohydrate and growth parameters among individual branches of alternate bearing ‘Kerman’ pistachio trees. J. Amer Soc. Hortic. Sci.124, 52–60 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iglesias, D. J., Tadeo, F. R., Primo-Millo, E. & Talón, M. Fruit set dependence on carbohydrate availability in citrus trees. Tree Physiol.23, 199–204 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mehouachi, J. et al. The role of leaves in citrus fruitlet abscission: Effects on endogenous gibberellin levels and carbohydrate content. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol.75, 79–85 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gómez-Cadenas, A., Mehouachi, J., Tadeo, F. R., Primo-Millo, E. & Talón, M. Hormonal regulation of fruitlet abscission induced by carbohydrate shortage in citrus. Planta210, 636–643 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Islam, M. Z., Jin, L. F., Shi, C. Y., Liu, Y. Z. & Peng, S. A. Citrus sucrose transporter genes: Genome-wide identification and transcript analysis in ripening and ABA-injected fruits. Tree Genet. Genom11, 1–9 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zheng, Q. M., Tang, Z., Xu, Q. & Deng, X. X. Isolation, phylogenetic relationship and expression profiling of sugar transporter genes in sweet orange (Citrus sinensis). Plant. Cell. Tiss Organ. Cult.119, 609–624 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mesejo, C., Martínez-Fuentes, A., Reig, C. & Agustí, M. Ringing branches reduces fruitlet abscission by promoting PIN1 expression in ‘Orri’ mandarin. Sci. Hortic.306, 111451 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shalom, L. et al. Fruit load induces changes in global gene expression and in abscisic acid (ABA) and indole acetic acid (IAA) homeostasis in citrus buds. J. Exp. Bot.65, 3029–3044 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nebauer, S. G., Renau-Morata, B., Guardiola, J. L. & Molina, R. V. Photosynthesis down-regulation precedes carbohydrate accumulation under sink limitation in Citrus. Tree Physiol.31, 169–177 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu, X., Li, J., Huang, M. & Chen, J. Mechanisms for the influence of citrus rootstocks on fruit size. Agric. Food Chem.63, 2618–2627 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gillaspy, G., Ben-David, H., Gruissem, W. & Darwin, C. Fruits: A developmental perspective. Plant. Cell.5, 1439–1451 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dorcey, E., Urbez, C., Blázquez, M. A., Carbonell, J. & Pérez-Amador, M. A. Fertilization-dependent auxin response in ovules triggers fruit development through the modulation of gibberellin metabolism in Arabidopsis. Plant. J.58, 318–332 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bermejo, A. et al. Auxin and gibberellin interact in citrus fruit set. J. Plant. Growth Regul.37, 491–501 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mesejo, C. et al. Gibberellin reactivates and maintains ovary-wall cell division causing fruit set in parthenocarpic Citrus species. Plant. Sci.247, 13–24 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wiltbank, W. J. & Krezdorn, A. H. Determination of Gibberellins in ovaries and young fruits of Navel Oranges and their correlation with Fruit Growth1. J. Amer Soc. Hortic. Sci.94, 195–201 (1969). [Google Scholar]

- 36.García-Papí, M. A. & García-Martínez, J. L. Endogenous plant growth substances content in young fruits of seeded and seedless clementine mandarin as related to fruit set and development. Sci. Hortic.22, 265–274 (1984). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moss, G. I., Steer, B. T. & Kriedemann, P. E. The regulatory role of infloeescence leaves in fruit-setting by sweet orange (Citrus sinensis). Physiol. Plant.27, 432–438 (1972). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Powell, A. A. & Krezdorn, A. H. Influence of fruit-setting treatment on translocation of 14 C-metabolites in citrus during flowering and fruiting. J. Amer Soc. Hortic. Sci.102, 709–714 (1977). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hoffman, P. J. Abscisic acid and gibberellins in the fruitlets and leaves of the Valencia orange in relation to fruit growth and retention. Proc. 6th Int. Citrus Congress1, 355–362 (1988). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guardiola, J. L., Agustí, M. & García-Marí, F. Gibberellic acid and flower bud development n sweet orange. Proc. Int. Soc. Citriculture2, 696–699 (1977). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rivas, F., Gravina, A. & Agustí, M. Girdling effects on fruit set and quantum yield efficiency of PSII in two Citrus cultivars. Tree Physiol.27, 527–535 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Blanke, M. & Bower, J. P. Small fruit problem in citrus trees. Trees5, 239–243 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Untiedt, R. & Blanke, M. Effects of fruit thinning agents on apple tree canopy photosynthesis and dark respiration. Plant. Growth Regul.35, 1–9 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schaffer, A. A., Goldschmidt, E. E., Goren, R. & Galili, E. Fruit set and carbohydrate status in alternate and non-alternate bearing Citrus cultivars. J. Amer Soc. Hortic. Sci.110, 574–578 (1985). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mao, Y. et al. The small subunit of RTubisco and its potential as an engineering target. J. Exp. Bot.74, 543–561 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ruan, Y. L. Sucrose metabolism: Gateway to diverse carbon use and sugar signaling. Annu. Rev. Plant. Biol.65, 33–67 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hussain, S. B. et al. Assessment of sugar and sugar accumulation–related gene expression profiles reveal new insight into the formation of low sugar accumulation trait in a sweet orange (Citrus sinensis) bud mutant. Mol. Biol. Rep.47, 2781–2791 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Deng, S., Mai, Y. & Niu, J. Fruit characteristics, soluble sugar compositions and transcriptome analysis during the development of Citrus maxima seedless, and identification of SUS and INV genes involved in sucrose degradation. Gene689, 131–140 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mesejo, C., Martínez-Fuentes, A., Reig, C. & Agustí, M. The flower to fruit transition in Citrus is partially sustained by autonomous carbohydrate synthesis in the ovary. Plant. Sci.285, 224–229 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bangerth, F. Abscission and thinning of young fruit and their regulation by plant hormones and bioregulators. Plant. Growth Regul.31, 43–59 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Botton, A. et al. Signaling pathways mediating the induction of apple fruitlet abscission. Plant. Physiol.155, 185–208 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Aloni, R. Ecophysiological implications of vascular differentiation and plant evolution. Trees29, 1–16 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mesejo, C., Martínez-Fuentes, A., Juan, M., Almela, V. & Agustí, M. Vascular tissues development of citrus fruit peduncle is promoted by synthetic auxins. Plant. Growth Regul.39, 131–135 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wisniewska, J. et al. Polar PIN localization directs auxin flow in plants. Science312, 883 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Křeček, P. et al. The PIN-FORMED (PIN) protein family of auxin transporters. Genome Biol.10, 1–11 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vieten, A., Sauer, M., Brewer, P. B. & Friml, J. Molecular and cellular aspects of auxin-transport-mediated development. Trends Plant. Sci.12, 160–168 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yamaguchi, N., Huang, J., Xu, Y., Tanoi, K. & Ito, T. Fine-tuning of auxin homeostasis governs the transition from floral stem cell maintenance to gynoecium formation. Nat. Commun.8, 1125 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Garner, L. C. & Lovatt, C. J. The relationship between flower and fruit abscission and alternate bearing of ‘Hass’ avocado. J. Amer Soc. Hortic. Sci.133, 3–10 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 59.Guitton, B. et al. Analysis of transcripts differentially expressed between fruited and deflowered ‘Gala’ adult trees: A contribution to biennial bearing understanding in apple. BMC Plant. Biol.16, 55 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Monselise, S. P. & Goldschmidt, E. E. Alternating bearing in fruit trees. Hortic. Rev.4, 128–173 (1982). [Google Scholar]

- 61.Muñoz-Fambuena, N. et al. Fruit regulates seasonal expression of flowering genes in alternate- bearing ‘Moncada’ mandarin. Ann. Bot.108, 511–519 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data from this work cannot be shared openly because it is part of a study whose privacy we must protect. However, all experimental results analysed in this study are available on request at magusti@prv.upv.es.