Abstract

In sub-Saharan Africa, young people are at high risk of HIV infection, representing nearly 4 out of 5 new infections. HIV self-testing (HIVST), a new and proactive testing scheme that involves self-collection of a specimen and interpretation of results, is deemed potentially helpful for increasing testing amongst population groups like young people who do not frequently use routine testing services. This study assessed young people’s intention to use HIVST in urban areas of southern Ethiopia drawing on the Theory of Planned Behaviour. A community-based cross-sectional study was conducted with 634 participants aged 15–24 years from six town administrations of two zones in January to February 2023. The participation rate was 634/636 yielding 99.7%. The OraQuick HIVST kit was demonstrated to young people recruited in a door-to-door survey with a face-to-face interview using an electronic questionnaire in a mobile phone-based application. Intention to use HIVST was measured from a 6-point Likert scale with scores of agreements ranging from 1 to 6. Descriptive statistics and ordinal logistic regression analysis were done using STATA version 18. Most of the participants agreed that they would use HIVST if it was available (86.3% agreeing or strongly agreeing). Interestingly, young people who perceived themselves at some to high risk were 0.51 times less likely to be in the higher order of intention to use when HIVST is available to them than those who perceived themselves at no to low risk. Intention to use HIVST increased by a factor of 1.29, 1.84 and 2.35 for every one-unit increase on the mean favourable attitude, perceived behavioural control, and acceptability scores, respectively. The majority of young people intended to use HIVST. Young people’s perceived behavioural control, and acceptability of HIVST affected their intention to use. Intention and subsequent use of HIVST can be enhanced through an understanding of the role of risk perception and positive attitude, confidence to perform and acceptance of the test. Implementation studies are required to examine the actual uptake of HIVST among young people.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-77728-5.

Keywords: Intention, HIV self-testing, Young people, Urban, Ethiopia

Subject terms: Diagnosis, Disease prevention, Health services, Public health, Health care

Background

Internationally, two-thirds of people living with HIV (PLWH) in 2023 lived in the sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). In 2023, the majority of new HIV infections in SSA occurred among women (over 60%) and younger populations aged 15–34 years (72.5%)1. Eastern and southern Africa are the most affected regions in SSA with 54% and 44% of global HIV prevalence and new infections in 2019 respectively were in these regions2. The joint United Nations Program on HIV (UNAIDS) proposed a second round of its three ambitious targets to end the HIV pandemic in 2030: the so-called 90-90-90 and the 95-95-95 targets set in 2014 and 2020. These aim to test 90/95% of people with HIV infection, enrol 90/95% of those who tested positive into treatment, and achieve 90/95% viral suppression for those on treatment in 2020 and 2025 respectively3,4. To achieve the first target (testing 95% of people with HIV infection) in the context of widespread stigma and discrimination towards HIV, the expansion of testing modalities that ensure the privacy and confidentiality, as well as reducing the subsequent stigma and discrimination, is essential. HIVST is a new and proactive way of testing oneself for HIV in a private place5,6 and is one proposed strategy to increase HIV testing by the World Health Organization (WHO)6. Apart from improving privacy and confidentiality, HIVST may improve access to HIV testing services because of factors such as convenience in saving time and transport related costs enabling it the test of choice for areas and populations with greatest gaps in testing coverage5. Many countries have started to incorporate HIVST policies and strategies into their context, mostly across Eastern and Southern Africa and Western and Central Europe7.

As one of the countries in eastern Africa, Ethiopia had a high prevalence of HIV (3%) in 2013, being one of the 10 countries comprising 80% of PLWH in the SSA8. Even though there has been impressive progress across the years with a national prevalence of less than 1% in the 2016 Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS), there is a significant disparity in urban-rural residences (with HIV prevalence 7 times higher in urban areas)9,10. Only 2 regions in the country (Addis Ababa city administration, and Harari regional state) achieved the testing and treatment of the 90-90-90 targets out of 10 regional states, and two city charters in Ethiopia, and all regions have achieved the third, viral suppression 90 target11. However, the country did not achieve the testing 90 target particularly among young people aged 15–24 years and men12. A recent spatial mapping study based on the 2016 EDHS identified that the Southern Nations Nationalities and Peoples Regional State was one of the regions with a lesser proportion of adolescent girls and young women who had ever tested for HIV, and being in the ages between 15 and 19 was a factor that was negatively associated with the testing rate13. In an urban context in Ethiopia, being male, and between 15 and 19 years old were negatively associated with HIV testing among youths 15–24 years old14. While HIVST has a potential role in increasing HIV testing, there is no existing research in Ethiopia on young people’s likely intention to take up HIVST if it were offered. The present study assesses the intention to use HIVST and factors associated with it among young people residing in urban areas of southern Ethiopia.

Young people, especially adolescent girls and young women, are at a disproportionately high risk for new HIV infection in SSA, accounting for 63% of all new infections in 202215,16. These groups are at particular risk because of complex factors that include engaging in multiple and age-disparate transactional sexual behaviours as a result of being at a socio-economic disadvantage, and religious and cultural factors like early marriage and other harmful traditional practices that encourage gender inequitable norms and practices17. The Ethiopian population-based HIV Impact Assessment (EPHIA) survey identified adolescents and youths at increased risk of HIV infection due to risky sexual behaviors related to early sexual debut and having multiple sexual partners18–20. Despite this risky sexual behavior, the testing rate remained low with only three out of 10 older adolescent boys20 and one in five young people aged 15–24 years tested for HIV14,20. The Ethiopian Public Health Institute also identified that youths between 15 and 24 years had the least awareness of their HIV status (72.6%) compared with those in the older age groups [25–34 (82.2%) and 35–49 (89.9%)]11.

There is limited research examining intention to perform HIV self-testing and existing literature has found varying degrees of intention for different population groups and contexts, albeit there was variation in definitions used to measure intention and factors from study to study. For example, 40.9% of young black transgender women and men who have sex with men (MSM) in the USA21, 38.5% of French people including MSM22, 23.8% of male clients of female sex workers23, 23.7% of migrant male factory workers24, 40% of MSM in China25, 83% of MSM in Spain26, 49.1% of MSM in Brazil27, 86% of women in Nigeria28, and 100% of female sex workers in Benin29 intended to use HIVST. Regarding intention among young people specifically, 90.4% of Columbian youths30, 66% of young university students in Zimbabwe31 and 100% of a predominantly young population (18–24 years) of MSM in South Africa32 were intending to use HIVST. Some of the studies also documented factors associated with participants intention to use HIVST21,22,24–26,31. In studies among key populations and/or adults, intention to test was higher among: young transgender women in the USA who were comfortable in testing at home with the assistance of a friend or partner, and who reported stigma or fear as reasons for not testing21; male clients of female sex workers in China who had a positive attitude, perceived that HIVST uptake is under their control, and perceived at high risk for HIV23; and MSM in China who were older, having a higher monthly income, being informed about HIVST, perceived accuracy of HIVST, and perceived ability to reduce fear during testing25. HIVST intention was lower for young transgender women with high social support and having had a health insurance21; French MSM22; and MSM in China having had higher scores on HIV knowledge25. In terms of young people specifically, young Zimbabwean university students with prior history of HIV testing and who noted the absence of a counselor during HIVST as a distressing situation were more likely to intend to test than those who had no previous history of HIV testing or who did not consider the absence of counselor as distressing situation respectively31. There are no studies examining predictors of HIVST intention in Ethiopia, including for young people.

According to Ajzen’s Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), intentions are self-instructions to perform behaviors or to obtain certain outcomes33,34.This theory asserts a given behavior like HIVST is driven by the intention to perform that behavior34. Although inconsistencies between intention and behavior can be expected, especially when one alters their intention before performing the behavior34, there is strong evidence that intention explains much of the variance of behavior35,36. Thus, to make important decisions on behaviors required for novel situations, as in the situation with HIVST, intention-driven action, and processing have been indicated as relevant37. Even though not among young people, evidence among women attending antenatal care in Ethiopia38, and other key populations elsewhere39–41 have also signified that HIV testing intention is related with later HIV testing. The TPB is a potentially useful approach to considering HIVST intention for it is a very helpful theoretical model to examine intention for a given behaviour. It is an extension to the theory of reasoned action, considering also perceived behavioural control or self-efficacy as antecedent variables that directly affects a given behaviour as well as indirectly through behavioural intention42.

In the African context broadly and in Ethiopia in particular, young people are at most risk of new HIV infection and report low HIV testing rates. Ethiopia has endorsed an HIVST implementation guideline and optimizing strategy that focuses on accessing HIV testing services to key and priority populations including female sex workers, long truck drivers, and vulnerable young people43–45. While the 90-90-90 targets review called for the application of HIVST as a promising strategy to improve testing rates11, young people more broadly (outside those included in the priority groups like young daily laborers, assistants of long truck drivers, prisoners, etc.) are not yet included in the HIVST guidelines even though assisted HIVST is allowed for those opting in to test based on risk assessment at health facilities and the community. As the final phase of HIVST service delivery will be to move to the provision of unassisted HIVST in open access through social marketing44,46, there is a need to investigate the intention of young people who are generally regarded as at high risk of HIV infection. Thus, before wide scale implementation of the HIVST among young people and the general community in Ethiopia, it is important to assess their intention to use HIVST and the factors associated with intention as there is a dearth of such evidence among young people in the country. Therefore, this study drew on the TPB and aimed to assess the degree of intention of urban young people to self-test for HIV and to identify factors associated with their intention in the south Ethiopian region through employing the constructs of the TPB and other potential factors identified from the literature. The findings from this study offer insights into how to optimise HIVST uptake of young people in the Ethiopian context and will also provide a baseline for future implementation research.

Methods

Overview

We conducted a community-based cross-sectional study aimed to address the intention of HIVST among young people aged 15 to 24 years. After three weeks of piloting the data collection instrument and recruitment of participants, data were collected between 24 January 2023 to 10 February 2023. This study was approved by the Flinders University Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC 5535) and is reported guided by the STROBE guidelines47. The STROBE checklist is given in Supplementary Material 2.

Study setting

The study was conducted in urban administrations of Gamo and Gofa zones in the South Ethiopia Region, which are respectively located 409 and 550 km southwest of Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia. The Ethiopian population in the 2007 population and housing census (the most recent census) was 73,750,93248, and the population growth rate is estimated at 2.5% in 202249.The main administrative centers for Gamo and Gofa zones are Arba Minch and Sawla towns which have populations of 123,446 and 85,704 respectively based on the 2007 Ethiopian census projected for the year 2022. Gamo and Gofa zones have six and four town administrations respectively. The total number of young people aged 15 to 24 years living in the six towns of the study area was estimated to be 61,83450. In the Gamo zone, a total of 14 public health facilities were providing anti-retroviral treatment services and 3 were providing HIVST services. There is an increase in the total number of people who tested positive for HIV (278 (0.4%) to 315(0.5%)) irrespective of age in the Gamo zone from the year 2021 to 202251.

Youth friendly centres located in the health facilities and community youth centres in Ethiopia provide voluntary HIV counselling and testing service, and promotive and preventive activities targeted in risk reduction and awareness raising on HIV52.

Participants

Eligibility criteria

The study population were young people between the ages 15–24 years who were permanent residents (lived for at least six months) in the study area. The definition of young people varies by organization and country. According to the United Nations Population Fund and the WHO, young people is defined as those individuals in the ages of 10 to 24 years53,54. The African Charter defines youths as those in the age group of 15 to 35 years53 and Ethiopia defines its youths as those between the ages 15 to 29 years55. In this study, we have targeted young people between the ages of 15 to 24 years and all genders, to align the lower age boundary with the age of consent for HIV testing in Ethiopia56 and the upper age boundary with global recommendations by the United Nations and WHO53, and the national level classification the EDHS and the EPHIA reports on10,20.

Youths were eligible to participate if they did not have an HIV diagnosis and were willing or able to provide consent, were not critically ill and did not have a disability that prevented participation in an interview.

Recruitment procedure

The study participants were randomly selected from four town administrations of the Gamo zone (Arba Minch, Kamba, Selamber, and Birbir) and two from the Gofa zone (Sawla and Beto) using a systematic, multistage sampling technique with households as sampling units. At first, towns in the two zones were stratified by their size as small (less than 50,000 population) and large towns (greater than or equal to 50,000 population). The main towns in the two zones (Arba Minch and Sawla) were included in the study for they were the only ones to fulfill the large town definition in the two zones. Out of five small-town administrations in the Gamo zone, we selected three towns (Birbir, Kamba and Selamber) using a lottery method of randomly drawing the names of towns on a coiled paper put on a dish. Likewise, one town (Beto) was selected from three small towns (Bulki, Beto and Laha) in the Gofa zone. In the second stage, ‘kebeles’/’ketenas’ (the smallest administrative units) from each of the included towns were selected based on the same lottery method. Households within these ‘kebeles’/’ketenas’ were included using a systematic random sampling allocated by proportional sampling based on the number of young people in each kebele with sampling intervals calculated for each town from the total sample size by weighing to these proportions. Whenever there was more than one young person in a household, one was selected randomly using a lottery method. For closed houses or households with no one at home, before considering it as a non-response, data collectors visited the same house for the second time on the next day of data collection, and if there was still no one at home, they checked the immediate next household for eligible participants. Likewise, when a household eligible by the random allocation using the sampling interval was found to have no eligible participants, the next households in order were approached to recruit eligible participants. Further details on the number of households and sampling intervals for each town is available in the Supplementary Material 3.

Data collection techniques and instrument

Data were collected via face-to-face interviewing of participants at their homes using 18 trained data collectors (five for Arba Minch town, three for each of Sawla, Birbir, and Selamber towns, and two for each of Kamba and Beto towns) who were aged 21–39 years and received a day long training from the research team. The training was aimed to familiarize the data collectors with interviewing skills, demonstration of HIVST kits and adherence to ethical standards. Data collectors were selected purposively based on criteria of prior experience in survey methods, having a smartphone, being female, being a peer navigator trained on HIVST in the main towns, and being a member of youth-friendly center in the respective small town. Four supervisors with a Master of Public Health degree and with prior experience in related field research practice were recruited to monitor and evaluate the data collection process.

The interviewers used a smart-phone based Kobo Toolbox application to record data without the need to have an internet connection or mobile carrier service, with data submission to an online server processed at a later time57. The questionnaire template used for data collection is provided in the Supplementary Material 4.

Because the pilot study found that few of young people had ever heard about HIVST, the attitude of young people toward HIVST was assessed after demonstrating OraQuick HIVST kits to them and describing the procedure for performing the test. The OraQuick HIV-1/2 kit is an innovative HIVST kit which is an immunochromatographic and visually read test that is used to detect antibodies of HIV 1/2 and is one of the recommended test kits by the WHO58. A diagnostic accuracy test conducted in public health facilities of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia showed a high diagnostic performance of the OraQuick HIV self-test and indicated that it has a high potential for use in Ethiopia59.

Variables and Measurement

Outcome variable

The outcome variable of the study is the intention to self-test for HIV. The intention to use HIVST was measured using the item: “If HIVST is available to me, I would use it”. The item is on a six-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (‘1’) to strongly agree (‘6’). We have used a single item to measure intention to use HIVST based on original recommendations by Icek Ajzen60 and later by Fishman et al., 202061. The latter study indicated that a single item used to measure intention demonstrated a strong predictive validity, and little additional value was added with the addition of one or more items61.

Independent variables

The latent independent variables considered in this study include constructs of the TPB (attitude towards HIVST, subjective norms about HIVST, and Perceived Behavioral Control), knowledge of HIVST, discriminatory attitude about HIV, and acceptability of HIVST. According to Seckhon et al.’s theoretical framework of acceptability62, acceptability is defined distinctly from intention, with its constructs proposed as predictors of intention to use an evidence-based healthcare practice. Advancing on this, a recent theoretical framework that has taken into account the Seckhon et al.’s framework and developed to theorize acceptability of health and social interventions among young people in Africa hypothesized acceptability as a predictor of intention to perform a given health behavior63. Thus, in this study, we assessed the prospective acceptability of HIVST and considered the acceptability of HIVST as one of the potential predictors of intention to use HIVST.

In the context of this study, the basic constructs of the TPB were measured: attitude (perception of how important HIVST is), subjective norms (SN: perceived support of performing HIVST by others valued to the young person), and perceived behavioral control (PBC: the young person’s confidence in their ability to perform HIVST). In the TPB, PBC affects actual behavior directly or through affecting one’s intention34.

SN and PBC were measured from 4 and 2 items that are presented in the questionnaire template (Supplementary material 4). The items used to measure SN and PBC were developed based on the TPB questionnaire originally suggested by Icek Ajzen, 200660. Internal consistency among items used to measure SN was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha (α = 0.63) which is in the acceptable range64,65. The mean score of the four items is used to calculate a SN score for each participant. The minimum mean score was 1.00 and the maximum was 5.75 from the sum of scores given for each of the questions from points 1 to 6 for “strongly disagree”, “disagree”, “somewhat disagree”, “somewhat agree”, “agree” and “strongly agree” respectively yielding total scores ranging from 4 to 24 for the four items. Higher scores indicate more favorable views. The reliability of the two items used to measure PBC was calculated based on suggestions by Eisinga66 using Spearman correlation which showed a positive association between the items (Spearman’s rho = 0.319, p-value less than or equal to 0.001). The total scores ranged from 2 to 12 for the two items.

Attitude questions presented in the questionnaire template (Supplementary Material 4) were adapted from a previous study in a similar setting67 and rated based on a six-point Likert scale response. Principal component analysis (PCA) and reliability analysis were undertaken to check whether the 11 attitude items were measuring the same construct or not. Before conducting the principal components analysis, items 7–11 (Q.3.8–11, Supplementary Material 4) were reverse scored so that high scores on attitude could indicate higher attitude scores. However, at the first iteration step of the PCA, the items showed two distinct factors: the first six items together made a single factor with eigenvalues greater than one and factor loadings greater than 0.4, and the reverse-scored items likewise indicated a distinct second factor. Thus, we considered the attitude variable as two separate variables, favorable and unfavorable attitude towards HIVST. In the latter case, we used the items in their original form (not reverse-scored). The reliability of the positive items measured using Cronbach’s alpha was acceptable (α = 0.78), and the negative items were also found to be acceptable (α = 0.68)64,65. Mean favorable attitude, and mean unfavorable attitude were computed as two distinct variables. Higher scores on favorable attitude indicate a more favorable attitude towards HIVST. Likewise, higher scores on unfavorable attitude indicate a more unfavorable attitude towards HIVST. An additional description of the the PCA analysis and measurement of other latent variables is provided in the Supplementary Material 5.

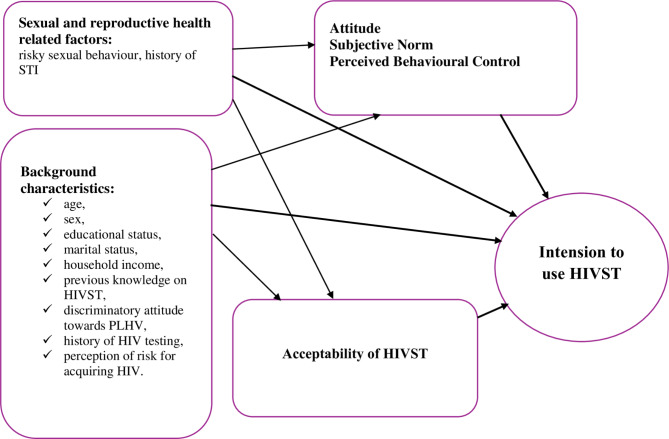

The additional factors considered to predict the outcome variable were socio-demographic factors (age, sex, average annual income, educational status, occupation, marital status); HIV test and risk perception-related factors (history of HIV test, and perceived risk to acquire HIV infection); and sexual and reproductive health-related factors comprising risky sexual behavior (such as condomless sex, and multiple sexual behaviors), being sexually active, age of sexual debut, and having recent (last 12 months) history of sexually transmitted infection. These items were measured from a single item that asked the participants to list or rate about the specific attribute. A conceptual framework depicting hypothesized relationships between the outcome and explanatory variables is presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

A conceptual framework depicting the relationship between intention to use HIVST and explanatory variables among young people in the urban areas of southern Ethiopian region.

Bias

Social desirability bias was anticipated in this survey context as the contents of the survey instrument contain sensitive matters related to one’s sexual and reproductive characteristics, and health service choices. We have taken this into account and designed the chronological order of the questions from less sensitive information about socio-demographic characteristics and knowledge matters to the more sensitive aspects of sexual practice. Data collectors were all female and were peer navigators trained on HIVST and working in the same community to provide HIVST service to key and priority populations in the two main towns and had a rich experience in working with youths at youth-friendly centres in the smaller towns where peer navigators were not yet in practice. The decision to involve only female data collectors was based on a reluctance of female young people to participate in the study when male data collectors approached them during the piloting of the survey instrument. In addition, data were collected in a private place in the participants’ homes. The use of Kobo Toolbox reduced missing of important data to the bare minimum for most alternatives were set as required information before scrolling down and asking the next question/s. As HIVST kits were a new technology to the community, the likelihood of information contamination was also high. Data collectors were advised during initial training to approach young people in private and advise them not to influence their peers.

Study sample size

The sample size was calculated using a single population proportion formula based on assumptions of 95% confidence interval (z α/2 = 1.96 ), 5% degree of precision,, and 75% willingness for future HIVST among young adults in Kenya68. The formula and the calculation are presented as follows.

|

Where n = sample size, zα/2 = reliability coefficient, p = proportion and D = degree of precision69.

A design effect of 2 was used for compensation of error arising from multistage cluster sampling. Moreover, to compensate for potential non-response, a 10% additional number of participants was added. The final sample size was calculated by multiplying the calculated sample size by the design effect and adding the additional 10% samples considered for potential non-response. Hence, based on these assumptions and considerations, the final sample size was 636.

Data processing and analysis

Data were transferred to the STATA software version 18 for cleaning and statistical analysis. Descriptive statistics were calculated to show the frequency of categorical variables in proportions or percentages, to explore the presence of outliers and to transform data as needed, to compute means and standard deviations for continuous variables, and to compute scores for composite variables. Ordinal logistic regression was used to identify independent factors associated with intention to use HIVST.

We checked multicollinearity and goodness-fit-of the model using variance inflation factor (VIF ≥ 5) criteria and a likelihood ratio chi-square test that checks whether there is a significant improvement in the fit of the final model relative to the intercept-only model (p-value < 0.001). The proportional odds assumption of ordinal logistic regression was checked using a test of parallel lines (non-significance of the − 2LL chi-square) (p-value = 0.54) using the omodel logit command70. Further details about data processing and analysis are given in the Supplementary Material 5.

Results

Overview

Of the proposed sample size of 636, we recruited 634 participants into the study yielding a response rate of 99.7%. Two participants did not proceed with providing information after withdrawing consent to participate in the study with complaints of time shortage and perceived inability to provide correct answers. In 147/634 (23.2%) households there was more than one eligible young people (and the lottery method was used) and in 79/634 (12.5%) households, young people were not present at their home on two occasions of consecutive days of data collection.

Participant characteristics

Out of the 634 participants, 350 (55.2%) were females. The mean age of the study participants was 20.17 (SD = 2.51). The average monthly household income was 5,546.01 Ethiopian Birr (SD = 6,013.25) or 103.4 USD. The average number of people living in the household who live on the income was 4 (range 1-11) people. Nearly two-thirds, 382/634 (60.3%) of the participants were single and more than a third of them 252/634 (39.7%) were in a relationship. Regarding their occupation, 402/634 (63.4%) of the participants were students, and 67/634 (10.6%) were self-employed. Nearly half of the study participants, 302/634(47.6%) were attending in secondary education in the high schools, and 127/634 (20%) were enrolled in colleges, and vocational schools.

Intention to self-test for HIV

Young people’s intention to use HIVST was assessed from the question “I would use HIVST if it were available to me”. The majority of the participants (86%) agreed or strongly agreed that they will use HIVST if it is available (Table 1).

Table 1.

Intention, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control of young people towards HIVST in urban areas of Gamo and Gofa Zones, southern Ethiopia, February 2023 (n = 634).

| Variable | Category, frequency (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strongly disagree | Disagree | Somewhat disagree | Somewhat agree | Agree | Strongly agree | ||

| Intention | I would use HIVST if it were available to me | 11 (1.7) | 36 (5.7) | 7 (1.1) | 35 (5.5) | 441 (69.6) | 104 (16.4) |

| Subjective norm | Approval or permission from family is needed for HIVST | 45 (7.1) | 334 (52.7) | 24 (3.8) | 51 (8.0) | 171 (27.0) | 9 (1.4) |

| Approval or permission from friends is required for HIVST | 44 (6.9) | 441 (69.6) | 19 (3.0) | 45 (7.1) | 84 (13.2) | 1 (0.2) | |

| Approval or permission is required from a partner for HIVST | 35 (5.5) | 265 (41.8) | 26 (4.1) | 48 (7.6) | 237 (37.4) | 23 (3.6) | |

| Knowing about HIV status of myself is expected from me | 6 (0.9) | 15 (2.4) | 11 (1.7) | 9 (1.4) | 508 (80.1) | 85 (13.4) | |

| Perceived behavioural control | I am confident to test for HIVST | 8 (1.3) | 17 (2.7) | 14 (2.2) | 36 (5.7) | 439 (69.2) | 120 (18.9) |

| Deciding whether to use HIVST or not is up to me | 6 (0.9) | 269 (4.1) | 10 (1.6) | 28 (4.4) | 470 (74.1) | 94 (14.8) | |

HIV testing history and perception of HIV risk

Slightly over half, 327/634 (51.6%) of young people in the study had not ever tested for HIV and 15/634 (2.4%) of participants were not sure whether they had ever tested or not. Nearly two-thirds 384/634 (60.6%) believed that they were not at risk of HIV infection. The remaining 250/634 (39.4%) varied in their level of HIV infection risk perception; 23/634 (3.6%) high risk, 43/634 (6.8%) at moderate risk, 66/634 (10.4%) somewhat at risk, and 118/634 (18.6%) at low risk. Among those ever tested for HIV, the number of times they tested ranged from 1 to 8, with a mean testing frequency of 2.23 (SD = 1.410). The more recent time of the test was 1 month and the longest time since the last test was 7 years and 4 months, with the average time after the test 12.01 months (SD = 14.98).

Sexual risk behavior and STI history

More than a third of the participants 236/634 (37.2%) responded that they have ever had a sexual intercourse and about 1 in 10 were not willing to respond to their experience on sexual affairs. Out of those who have had any sexual intercourse history, 208/634 (32.8%) had been sexually active in the six months before the survey. Among those who had a recent sexual intercourse history, 71/634 (11.2%) had reported that they had more than one sexual partner. Regarding their condom use during recent sexual practice, only 51/634 (8%) regularly used condoms.

Knowledge about HIVST

Of the 634 young people who participated in the study, 177 (27.9%) had ever heard about HIVST and this was from various sources. Health professionals accounted for the largest source of information (18.8%) followed by the mass media (6.9%). Based on the overall knowledge score from the five reliable items, 23.9% participants had a high level of knowledge while nearly two-thirds (62.6%) had a low level of knowledge (Table 2).

Table 2.

Awareness and knowledge about HIVST among young people in urban areas of Gamo and Gofa Zones z, southern Ethiopia, February 2023 (n = 634).

| Variable | Category | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ever heard about HIVST | Yes | 177 | 27.9 |

| No | 406 | 64.0 | |

| Not sure | 51 | 8.0 | |

| Ever seen HIVST | Yes | 131 | 20.7 |

| No | 464 | 73.2 | |

| Not sure | 39 | 6.2 | |

| HIVST is legal in Ethiopia | Yes | 98 | 15.5 |

| No | 323 | 50.9 | |

| Not sure | 213 | 33.6 | |

| HIVST can be performed from blood samples | Yes | 354 | 55.8 |

| No | 121 | 19.1 | |

| Not sure | 159 | 25.1 | |

| HIVST can be done at home | Yes | 236 | 37.2 |

| No | 157 | 24.8 | |

| Not sure | 241 | 38.0 | |

| HIVST can be done by the assistance of health care professionals | Yes | 461 | 72.7 |

| No | 48 | 7.6 | |

| Not sure | 125 | 19.7 | |

| HIVST can give a negative result if tested in 3 months of HIV infection | Yes | 299 | 47.2 |

| No | 107 | 16.9 | |

| Not sure | 228 | 36.0 | |

| A negative HIVST should be re-tested after 3 months | Yes | 447 | 70.5 |

| No | 36 | 5.7 | |

| Not sure | 151 | 23.8 | |

| A positive HIVST shows a definite HIV infection | Yes | 386 | 60.9 |

| No | 89 | 14.0 | |

| Not sure | 159 | 25.1 | |

| Overall knowledge | Low | 397 | 62.6 |

| Moderate | 85 | 13.4 | |

| High | 152 | 24.0 |

Discriminatory attitude towards people living with HIV

Most of the participants did not report discriminatory attitudes towards PLWH, with 554 (86%) reporting that they would buy fruit and vegetables from a person known to be HIV positive and 605/634 (95.4%) agreed that children should learn together with HIV-positive children. Taken together, 610/634 (96.2%) did not express agreement with either of these two indicators of discriminatory attitude towards PLWH.

The attitude of participants towards HIVST

About two-thirds of young people (70.5%) agreed that HIVST would increase public awareness about HIV status, increase testing frequency (68.0%), increase the chance of early treatment (63.7%), and save time spent at clinics or hospitals (63.4%). Around half of the participants also agreed that HIVST ensures privacy (55.5) and helps for prevention of HIV infection (49.1%). On the other hand, about half disagreed that instructions on the OraQuick HIVST kit are difficult to read and understand (50.3%). More than a third (37.2%) and about half (46.4%) respectively disagreed that HIVST might lead to partner and family member disapproval. Young people were not sure to rate about their attitude in all the items with 1.6–30.8% of the participants in the study responding respectively as they were not sure whether HIVST saves time from clinic or hospital visits and results can be incorrectly interpreted or not. The mean favorable and unfavorable attitude scores for each participant ranged from 1.17 to 7.00, and 1.40 to 7.00 respectively. The total mean computed from all the mean scores of the participants was 5.66 (SD = 0.88) and 4.02 (SD = 1.15) respectively for favorable attitude and unfavorable attitude (Table 3).

Table 3.

Attitude towards HIVST among young people in Urban areas of Gamo and Gofa Zones, southern Ethiopia, February 2023 (n = 634).

| Variables | Category, frequency (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strongly disagree | Disagree | Somewhat disagree | Somewhat agree | Agree | Strongly agree | Not sure | |

| Ensures privacy | 19 (3.0) | 33 (5.2) | 19 (3.0) | 61 (9.6) | 352 (55.5) | 111 (17.5) | 39 (6.2) |

| Help for prevention of HIV infection | 10 (1.6) | 94 (14.8) | 15 (2.4) | 94 (14.8) | 311 (49.1) | 71 (11.2) | 39 (6.2) |

| Increases public awareness about HIV status | 6 (0.9) | 23 (3.6) | 14 (2.2) | 37 (5.8) | 447 (70.5) | 89 (14.0) | 18 (2.8) |

| Saves time spent at clinic or hospitals | 11 (1.7) | 24 (3.8) | 14 (2.2) | 32 (5.0) | 402 (63.4) | 141 (22.2) | 10 (1.6) |

| Increases testing frequency | 5 (0.8) | 16 (2.5) | 11 (1.7) | 40 (6.3) | 431 (68.0) | 116 (18.3) | 15 (2.4) |

| Increases the chance of early treatment | 5 (0.8) | 12 (1.9) | 10 (1.6) | 60 (9.5) | 404 (63.7) | 122 (19.2) | 21 (3.3) |

| Instructions are difficult to read and understand | 50 (8.2) | 319 (52.3) | 29 (4.8) | 325.2 | 96 (15.7) | 24 (3.8) | 84 (13.8) |

| Result can be incorrectly interpreted(N = 633)a | 12 (1.9) | 150 (23.7) | 19 (3.0) | 48 (7.6) | 176 (27.8) | 33 (5.2) | 195 (30.8) |

| People may harm themselves if not counselled and test positive | 12 (1.9) | 63 (9.9) | 17 (2.7) | 116 (18.3) | 302 (47.6) | 60 (9.5) | 64 (10.1) |

| HIVST might lead to partner disapproval | 23 (3.6) | 236 (37.2) | 21 (3.3) | 63 (9.9) | 174 (27.4) | 34 (5.4) | 83 (13.1) |

| HIV might lead to family member disapproval (N = 633)a | 18 (2.8) | 294 (46.4) | 24 (3.8) | 59 (9.3) | 146 (23.0) | 28 (4.4) | 64 (10.1) |

Note: a = One participant declined to answer this question.

Subjective norm and perceived behavioral control

The mean SN calculated from all the means of each participant from the 4 items used to measure SN was 3.87 (SD = 0.87) while the mean PBC score calculated from the mean of each participant’s score was 4.93 (SD = 0.69) with a minimum mean score of 1.5 and maximum 6 (Table 3).

Factors associated with intention to use HIVST

A chi-square test did not show a statistically significant difference in degrees of intention between male and females (Pearson Chi-square p-value = 0.822), younger youths (15-17 yeas old) and older youths (at or above 18 years old) (Pearson Chi Square p-value = 0.995), those having moderate to high knowledge, and those with low knowledge about HIVST (Pearson Chi-square P-value = 0.082), and those with marital or partnership status and were single (Pearson Chi Square = 0.802). However, a significant difference was observed between those who attended to a higher education and those with secondary education or below secondary education (Pearson Chi-square p-value = 0.032). Of 16 variables considered in the initial model, four variables, namely perceived risk for acquiring HIV infection (p-value = 0.03), perceived behavioral control (p-value < 0.001), attitude (p-value < 0.001), and acceptability (p-value < 0.001) showed a statistically significant association with young people’s intention to self-test for HIV in the final ordinal logistic regression model.

The odds of being in the higher order of intention to use HIVST when it is available for those perceiving themselves at some to high risk for HIV infection was 0.51 times that of those who perceived themselves at no to low risk. On the other hand, the odds of being in the higher order of intention to use HIVST increased by a factor of 1.71, 2.62 and 3.93 for every one-unit increase in favorable attitude, perceived behavioral control, and acceptability mean scores. This indicates that young people with a higher mean score on PBC, high mean favorable attitude, and high mean acceptability were more likely to intend to use HIVST (Table 4).

Table 4.

Factors associated with intention to use HIVST among young people living in urban areas of Gamo and Gofa Zones, southern Ethiopia, February 2023.

| Variable | Category | B | Sig | OR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intention to use HIVST | Lower | Upper | ||||

| Perceived risk | Low to no risk | 0a | 1 | |||

| Some to high risk | -0.68 | 0.03 | 0.51 | 0.27 | 0.93 | |

| PBC | 0.96 | < 0.001 | 2.62 | 1.84 | 3.73 | |

| Favourable Attitude | 0.54 | < 0.001 | 1.71 | 1.29 | 2.25 | |

| Acceptability | 1.37 | < 0.001 | 3.93 | 2.35 | 6.56 | |

Note: a = reference group.

Discussion

This community-based cross-sectional study examined urban young people’s intention to use HIVST in Southern Ethiopia in a door-to-door interview after a demonstration of HIVST kits. Our analysis revealed a high intention for HIVST use among young people and participants’ attitudes, perceived behavioral control, perception of risk and acceptance of the test were significantly associated with their intention to use. The Ethiopian government is currently implementing assisted and unassisted HIVST in two successive phases among key and priority populations including female sex workers, long truck drivers and their assistants, prisoners, and daily laborers which consisted of people over a range of ages including many vulnerable young people. They are considering extending HIVST to all community members in an open access scheme through social marketing in the next third phase in the future44. These findings are therefore of note for broader HIVST implementation amongst young people as the study included a general population of young people from various backgrounds including those in and out of schooling and indicated the need to consider intrinsic factors related to their attitude and perception.

The high intention to use HIVST in this study is similar to previous reports among youths in other parts of Africa – for example young university students in Zimbabwe31, and young MSM in South Africa32 and other key populations in Nigeria28, and Benin29. However, the finding is higher than most studies conducted among young and adult key populations in high- and upper-middle-income countries21–25,27. This disparity in intention with most of the studies from high- and upper-middle-income countries and low-income countries like ours might be related to the higher preference of young people to test in private so that they can avoid discrimination from health care practitioners, parents, and the community in the latter context. Stigma and discrimination are some of the commonest barriers to accessing health facility-based reproductive health services including HIV testing among young people as supported by a recent review in SSA71. In addition, in countries with middle to high economies, the routine HIV testing service will likely be confidential, accessible, and of quality that might not necessitate consideration of HIVST72. Study variations may also relate to the timeframe measured for intention. Some studies have examined intention within a short period (6 months to 1 year)21–25,27 and others, such as our own, have left it open or asked about participants’ intentions at any time when HIVST becomes available to them26,28–32. Our findings, and those of other studies seem to indicate that there is a higher reported intention to use HIVST when the time frame is not fixed in advance. In what follows, we present the factors shown to influence the intention to use HIVST among the participants.

In our study, young people with high favorable attitude scores indicating more positive views towards HIVST showed greater intention than those who were less positive. This concurs with what the TPB34 would predict, and the findings of previous studies which considered the attitude of young people73–76 and other population groups24,77–79 as predictor of their intention to use HIV testing services. The independent association of attitude in predicting intention to self-test suggests that young people’s readiness to take up HIVST rests on their intrinsic beliefs about the HIVST. This was further strengthened by the low knowledge about HIVST among the target groups. Although most of the participants had a high attitude score based on the on-site demonstration of kits, high knowledge remains the basic antecedent factor for a positive attitude, intention and subsequent take-up of HIVST. The insignificant association with unfavourable attitudes might imply that young people who had misconceptions also had better intentions to self-test given their high interest and curiosity to take up HIVST.

In terms of the other elements of the TPB, perceived behavioral control was also positively associated with intention. Measured from 4 items that assessed whether young people needed approval or permission from their family, friends, or partner, or they have a normative belief that knowing their own HIV status is something expected of them or not, the subjective norm of the participants did not show a significant association with their intention in this study. Perceived behavioral control has been significantly associated with the intention for HIV testing in various previous studies across the globe24,74,79,80. While a global systematic review conducted in 2017 indicated that there was inconsistent or insufficient evidence to prove the relationship between perceived behavioral control, subjective norm and HIV testing intention, it noted that perceived behavioral control did show a positive association with intention to test in the African context specifically81. Measured from two items in our study which asked about young people’s ability to test and make autonomous decisions to conduct HIVST, young people’s perception that HIVST is under their control might be an essential step for HIVST uptake.

Beyond TPB constructs, a number of other factors were associated with intention. Young people’s perception of risk for HIV infection was negatively associated with HIVST intention in the present study. This surprising finding suggests that young people who perceived themselves as low to no risk were more likely to intend to use when HIVST is available to them than those who perceived themselves at a some to high risk. This contradicts previous literature that documented a positive association between risk perception and intention to use HIVST or HIV testing more generally in the USA, Thailand, and China21,80,82, and no association with behavioral intention to self-test and HIV testing in another study among migrant factory works in China24. The perceived high risk for infection, and its negative relationship with intention to use HIVST, might be related to fear of positive test results. This was a common reflection in the HIVST literature83–88 where young people themselves and other stakeholders had concerns about social harm arising from testing positive in the absence of appropriate counseling. In other words, those who perceived themselves at some or high risk of HIV infection would be frightened of testing positive and those who perceived themselves at low risk to no risk would have a heightened confidence to intend to test out of the expectation that they will test negative for HIV.

Acceptability of HIVST was found to be the strongest predictor of intention to use HIVST in the current study. The association between acceptability and intention to use a health care intervention or service is only a recent suggestion in the public health literature when Seckon et al., 2017 distinctly defined acceptability as a multifaceted construct that can be taken as antecedent to intention to act on a given health care intervention or behavior62, built on by Casale63. Since acceptability was measured as a composite from questions that assessed participants’ perception of taking HIVST (as comfortable, not demanding effort, fair to all, improves knowledge of HIV, clearly beneficial to know their HIV status, and that they can perform it confidently), it is plausible that those having a high mean score of acceptability (who were in more agreement with) would likely intend to use HIVST.

As intention is a strong predictor of prospective behavior (in our case actual HIVST), there is a promising prospect to adopt HIVST among young people in the study region and to the Ethiopian urban young people broadly to increase HIV testing and early linkage to treatment. Thus, the high level of intention in our study is an important finding for policymakers in Ethiopia to consider as they roll out HIVST more generally among young people in the country. The independent association of factors like attitude, perceived behavioral control, and acceptability of HIVST shows young people’s intrinsic feelings about HIVST outweighed any external or non-modifiable factors related to their socio-demographic background. The paradoxical association between low to no perceived risk of acquiring HIV and high intention would suggest the importance of tailoring HIVST promotion on how young people perceived themselves and raising awareness among those who perceived themselves at high risk that HIVST is not confirmatory test or testing positive means not necessarily having the infection. Overall, the factors shown to be associated with young people’s intention to use HIVST are intrinsic to young people’s perceptions and beliefs. This would indicate the importance of the creation of public awareness and clearance of misconceptions through wide-scale promotion of the testing kits using public outlets including the mass-media, and social media, and engaging young people in peer and community conversations locally in advance to the expansion of the HIVST service among young people in the general community. No association with subjective norms of the participants might indicate that young people were not submissive to their role models or significant others, or the lack of culture-motivated advocacy of HIV testing in the study area. This highlights the likely important role of cultural, resource and HIV-specific contexts for these constructs in relation to HIV testing in general and HIVST specifically.

Study strengths and limitations

There were several strengths in our study. This was the first study in Ethiopia to examine HIVST intention amongst young people, as well as explore the predictors of this intention. We used the TPB to hypothesize cognitive variables related to one’s beliefs and perceptions and found a partly consistent finding with what has been formulated in the theory. Our data collectors conducted a demonstration of HIVST at each face-to-face interview, which meant people had an accurate understanding of what was involved with the test. We used data collectors who are trained in HIV self-testing and working as peer navigators and as members of youth-friendly centers in the community. This meant they had highly developed skills in building rapport with young people and discussing sensitive matters and there was a high response rate for the survey. However, there are a few limitations to consider. As noted in “Methods” section, social desirability and information bias were possible because of the sensitive nature of HIV matters. While we sought to address this bias by including only women in the data collection team and through placement of questions to the latter part of the survey, the refusal of some young people to disclose information about their sexual experience might have underestimated the real magnitude of risky sexual behavior in the study area. Although we selected one young people per household for an interview, there were households with complex families of tenants and household heads’ families living together in a single compound. With priority given to permanent residence in the specific town, randomly selecting the young people of the household heads’ family alone might have introduced selection bias. While our purposive selection of two of the main towns for the study was undertaken to balance competing priorities of resource limitation and widening the scope of the study over a range of geographic locations (to ensure recruitment of a wide range of young people with a heightened risk of being engaged into risky sexual behavior and increased demand for HIVST), this might also have introduced selection bias. Regarding the design of the study, its cross-sectional nature limits the causality of association or temporal relationship between the outcome and independent variables, suggesting the need for stronger implementation research on HIVST among the study targets. The other limitation of the study was recruitment of YP based on availability in the randomly selected household while ideally a census of eligible participants would have been done. This was not possible because of resource limitations, and as for absence of participants at the home, we have recruited participants from the neighboring households in order.

Conclusion

The study showed a high intention to use HIVST among young people in the urban areas of Southern Ethiopia. Intention to self-test for HIV was associated with perceived low to no risk of HIV, attitude, PBC, and acceptability of HIVST. Interventions targeting HIVST among young peoples in the general community need to work particularly closely with young peoples with high-risk perception, negative attitude, perceived least control of HIVST, and low acceptance of HIVST.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Our gratitude goes to Flinders University for the provision of a fund for overseas data collection. We also would like to address our sincere appreciation and warmest thanks to the data collectors and supervisors of this survey without whose authentic work the study would not have been possible. We would like to particularly appreciate the cooperation of Mr Teshale Fikadu for his assistance with the creation of the Kobo Toolbox template and synchronization of the application to the mobile phones of each data collector and supervisor.

Abbreviations

- EDHS

Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey

- EPHIA

Ethiopian Population-Based HIV Impact Assessment

- HIV

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

- HIVST

HIV self-testing

- MSM

Men who have sex with men

- PBC

Perceived Behavioural Control

- PLWH

People Living with HIV

- SN

Subjective Norm

- SSA

Sub-Saharan Africa

- TPB

Theory of Planned Behaviour

- WHO

World Health Organization

Author contributions

E.A.Z., J.S., H.A.G., and A.Z. contributed to the study conception and design. E.A.Z. wrote the draft proposal, and obtained ethical clearance through the guidance of A.Z., J.S., and H.A.G. Material preparation, and data collection were performed by E.A.Z., B.M.G., and K.T.W. E.A.Z. conducted data management and analysis with K.T.W. through the guidance of A.Z., J.S., and H.A.G. The first draft manuscript was written by E.A.Z., and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by Flinders University, College of Medicine, and Public Health.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) of Flinders University (Project ID:5535) and the Institutional Research Ethics Review Board (IRB) of Arba Minch University (Reference Number: IRB/1320/2022).

Consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from the participants and from their parents or guardians for minors. This was done using a translated version of a format initially provided by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Flinders University.

Standards of reporting

The STROBE checklist for reporting observational studies was used and is attached in the Supplementary Material.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Nsanzimana, S. & Mills, E. J. Estimating HIV incidence in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet HIV10(3), (2023). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Parker, E. et al. HIV infection in Eastern and Southern Africa: Highest burden, largest challenges, greatest potential. South Afr. J. HIV Med.22(1), 1237 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.HIV/AIDS JUNPo, HIV/Aids JUNPo. 90-90-90: An Ambitious Treatment Target to Help End the AIDS Epidemic (UNAIDS, Geneva, 2014).

- 4.UNAIDS. UNAIDS Prevailing Against Pandemics by Putting People at the Centre. Available from: https://aidstargets2025.unaids.org/assets/images/prevailing-against-pandemics_en.pdf (2020).

- 5.WHO. WHO Recommends HIV Self-Testing – Evidence Update and Considerations for Success: Policy Brief. Available from: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/329968/WHO-CDS-HIV-19.36-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (2019).

- 6.WHO. HIV Self-Testing and Partner Notification Supplement to Consolidated Guidelines on HIV Testing Services (2016). [PubMed]

- 7.WHO. WHO HIV Policy Adoption and Implementation Status in Countries. Available from: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/hq-hiv-hepatitis-and-stis-library/who-hiv-policy-adoption-in-countries_2023.pdf?sfvrsn=e2720212_1 (2023).

- 8.Kharsany, A. B. & Karim, Q. A. HIV infection and AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa: Current status, challenges and opportunities. Open AIDS J.10, 34–48 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kibret, G. D. et al. Trends and spatial distributions of HIV prevalence in Ethiopia. Infect. Dis. Poverty8(1), 90 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Central Statistical Agency (CSA) [Ethiopia] and ICF & Rockville, U. The 2016 Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey: HIV Prevalence Report (2018).

- 11.EPHI. Current Progress Towards 90-90-90 HIV Treatment Achievement and Exploration of Challenges Faced in Ethiopia (2020).

- 12.Lulseged, S. et al. Progress towards controlling the HIV epidemic in urban Ethiopia: Findings from the 2017–2018 Ethiopia population-based HIV impact assessment survey. PLoS One17(2), e0264441 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shimbre, M. S. et al. Spatial mapping and predictors of ever-tested for HIV in adolescent girls and young women in Ethiopia. Front. Public Health12, 1337354 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ajiboye, A. S. et al. Predictors of HIV testing among youth 15–24 years in urban Ethiopia, 2017–2018 Ethiopia population-based HIV impact assessment. PLoS One18(7), e0265710 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.UNAIDS. The Path that Ends AIDS: UNAIDS Global AIDS Update 2023. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2023/global-aids-update-2023 (2023).

- 16.UNAIDS. Global HIV Statistics Fact Sheet (2023).

- 17.Murewanhema, G., Musuka, G., Moyo, P., Moyo, E. & Dzinamarira, T. HIV and adolescent girls and young women in sub-Saharan Africa: A call for expedited action to reduce new infections. IJID Reg.5, 30–32 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Ministry of Health. National Reproductive Health Strategy (2016 – 2020). Available from: https://platform.who.int/docs/default-source/mca-documents/policy-documents/plan-strategy/ETH-CC-10-01-PLAN-STRATEGY-2016-eng-National-RH-Strategy-2016-2020.pdf (2016).

- 19.Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Ministry of Health. National Adolescent and Youth Health Strategy (2016–2020) (2016).

- 20.EPHI (EPHI). Ethiopia Population-Based HIV Impact Assessment (EPHIA) 2017–2018: Final Report. (2020).

- 21.Koblin, B. A. et al. Informing the development of a mobile phone HIV testing intervention: Intentions to use specific HIV testing approaches among young black transgender women and men who have sex with men. JMIR Public Health Surveill.3(3), e45 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Devez, P. E. & Epaulard, O. Perceptions of and intentions to use a recently introduced blood-based HIV self-test in France. AIDS Care30(10), 1223–1227 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lau, C. Y. K. et al. Prevalence of and factors associated with behavioral intention to take up home-based HIV self-testing among male clients of female sex workers in China - An application of the Theory of Planned Behavior. AIDS Care33(8), 1088–1097 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang, K., et al. Low behavioral intention to use any type of HIV testing and HIV self-testing among migrant male factory workers who are at high risk of HIV infection in China: A secondary data analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 20(6), (2023) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Wong, H. T., Tam, H. Y., Chan, D. P. & Lee, S. S. Usage and acceptability of HIV self-testing in men who have sex with men in Hong Kong. AIDS Behav.19(3), 505–515 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koutentakis, K. et al. HIV self-testing in Spain: A valuable testing option for men-who-have-sex-with-men who have never tested for HIV. PLoS One14(2), e0210637 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Magno, L. et al. Acceptability of HIV self-testing is low among men who have sex with men who have not tested for HIV: A study with respondent-driven sampling in Brazil. BMC Infect. Dis.20(1), 865 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adebimpe, W. O., Ebikeme, D., Omobuwa, O. & Oladejo, E. How acceptable is the HIV/AIDS self-testing among women attending immunization clinics in Effurun, Southern Nigeria. Marshall J. Med. 5(3), (2019).

- 29.Boisvert Moreau, M. et al. HIV self-testing implementation, distribution and use among female sex workers in Cotonou, Benin: A qualitative evaluation of acceptability and feasibility. BMC Public Health22(1), 589 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brown, W. 3rd., Carballo-Dieguez, A., John, R. M. & Schnall, R. Information, motivation, and behavioral skills of high-risk young adults to use the HIV self-test. AIDS Behav.20(9), 2000–2009 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mukora-Mutseyekwa, F. et al. Implementation of a campus-based and peer-delivered HIV self-testing intervention to improve the uptake of HIV testing services among university students in Zimbabwe: The SAYS initiative. BMC Health Serv. Res.22(1), 222 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lippman, S. A. et al. High acceptability and increased HIV-testing frequency after introduction of HIV self-testing and network distribution among South African MSM. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr.77(3), 279–87 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Triandis, H. C. Values, attitudes, and interpersonal behavior. Neb. Symp. Motiv.27, 195–259 (1979). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process.50(2), 179–211 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sheeran, P. Intention—behavior relations: A conceptual and empirical review. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol.12(1), 1–36 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Webb, T. L. & Sheeran, P. Does changing behavioral intentions engender behavior change? A meta-analysis of the experimental evidence (0033–2909 (Print)). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behaviour: Reactions and reflections. Psychol. Health26(9), 1113–1127 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mirkuzie, A. H., Sisay, M. M., Moland, K. M. & Astrom, A. N. Applying the theory of planned behaviour to explain HIV testing in antenatal settings in Addis Ababa - A cohort study. BMC Health Serv. Res.Bold">11, 196 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ostermann, J. et al. Trends in HIV testing and differences between planned and actual testing in the United States, 2000–2005. Arch. Intern. Med.167(19), 2128–2135 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Phillips, K. A., Coates, T. J. & Catania, J. A. Predictors of follow-through on plans to be tested for HIV. Am. J. Prev. Med.13(3), 193–198 (1997). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McGarrity, L. A., Huebner, D. M., Nemeroff, C. J. & Proeschold-Bell, R. J. Longitudinal predictors of behavioral intentions and HIV service use among men who have sex with men. Prev. Sci.19(4), 507–515 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Madden, T. J., Ellen, P. S. & Ajzen, I. A comparison of the theory of planned behavior and the theory of reasoned action. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull.18(1), 3–9 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ministry of Health Ethiopia. HIV Self-Testing (HIVST): Implementation Manual for Delivery of Directly Assisted HIV Self Test Service in Ethiopia, (2019).

- 44.Ministry of Health Ethiopia. Unassisted HIV Self Test (HIVST) Implementation Manual for Delivery of HIV Self Testing Service in Ethiopia Federal Ministry of Health Ethiopia, (2020).

- 45.Ministry of Health Ethiopia. Support Document for Optimization of HIV-Self Test Kit Distribution and Use for Targeted Key and Priority Populations, (2022).

- 46.PEPFAR. Ethiopia Country Operational Plan (COP) 2022, Strategic Direction Summary, (2022).

- 47.Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. The lancet. 370(9596), 1453–7 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Office of the Population Census Commission. The 2007 Population and Housing Census of Ethiopia, (2007). Available from https://www.statsethiopia.gov.et/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Population-and-Housing-Census-2007-National_Statistical.pdf

- 49.World Bank. Population Growth(Annual %)-Ethiopia,(2023) [Internet]. Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.GROW?locations=ET (2023).

- 50.Gamo and Gofa Zone Health Department. Mid-year health report: Multi-sectoral HIV Prevention and Control core process.Arba Minch and Sawla, 2022/2023.

- 51.Gamo Zone Health Department. Mid-year health report: Multi-sectoral HIV prevention and control. Arba Minch. 2022/2023.

- 52.Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia. Ministry of Health. Standards on Youth Friendly Reproductive Health Services Service Delivery Guideline & Minimum Service Delivery Package on YFRH Services.

- 53.UNFPA. Adolescent and Youth Demographics: A Brief Overview. Available from: https://www.unfpa.org/resources/adolescent-and-youth-demographicsa-brief-overview.

- 54.World Health Organization. Adolscent Health in the South-East Asian Region Geneva, Switzerland. Available from: https://www.who.int/southeastasia/health-topics/adolescent-health.

- 55.FMOH. National Youth Policy (2004).

- 56.Ministry of Health Ethiopia. National Guideline for Comprehensive HIV Prevention, Care and Treatment (2022).

- 57.KoboToolbox. Making Data Collection Accessible to Everyone, Everywhere. Available from: https://www.kobotoolbox.org/about-us/.

- 58.Pant, P. N. Oral fluid-based rapid HIV testing: Issues, challenges and research directions. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn.7(4), 325–328 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Belete, W. et al. Evaluation of diagnostic performance of non-invasive HIV self-testing kit using oral fluid in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: A facility-based cross-sectional study. PLoS One14(1), e0210866 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ajzen, I. Constructing a Theory of Planned Behavior Questionnaire 1–12 (2006).

- 61.Fishman, J., Lushin, V. & Mandell, D. S. Predicting implementation: Comparing validated measures of intention and assessing the role of motivation when designing behavioral interventions. Implement Sci. Commun.1, 81 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sekhon, M., Cartwright, M. & Francis, J. J. Acceptability of healthcare interventions: An overview of reviews and development of a theoretical framework. BMC Health Serv. Res.17(1), 88 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Casale, M. et al. A conceptual framework and exploratory model for health and social intervention acceptability among African adolescents and youth. Soc. Sci. Med.326, 115899 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hajjar, S. T. E. Statistical analysis: Internal-consistency reliability and construct validity. Int. J. Quant. Qual. Res. Methods6(1), 46–57 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shi, J., Mo, X. & Sun, Z. Content validity index in scale development. Zhong Nan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban37(2), 152–155 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Eisinga, R., Grotenhuis, M. & Pelzer, B. The reliability of a two-item scale: Pearson, Cronbach, or Spearman-Brown?. Int. J. Public Health58(4), 637–642 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gumede, S. D. & Sibiya, M. N. Health care users’ knowledge, attitudes and perceptions of HIV self-testing at selected gateway clinics at eThekwini district, KwaZulu-Natal province, South Africa. SAHARA J: J. Soc. Aspects of HIV/AIDS Res. Alliance15(1), 103–109 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Olakunde, B. O., Alemu, D., Conserve, D. F., Mathai, M., Mak’anyengo, M. O., NAHEDO Study Group et al. Awareness of and willingness to use oral HIV self-test kits among Kenyan young adults living in informal urban settlements: a cross-sectional survey. AIDS Care (8915313, a1o), 1–11 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 69.Arifin, W. N. Introduction to sample size calculation. Educ. Med. J.5(2), (2013).

- 70.Johnston, A. Methods/STATA Manual for School of Public Policy Oregon State University (2013).

- 71.Sidamo, N. B., Kerbo, A. A., Gidebo, K. D. & Wado, Y. D. Socio-ecological analysis of barriers to access and utilization of adolescent sexual and reproductive health services in sub-Saharan Africa: A qualitative systematic review. Open Access J. Contracept.14, 103–118 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Deng, P., Chen, M. & Si, L. Temporal trends in inequalities of the burden of HIV/AIDS across 186 countries and territories. BMC Public Health23(1), 981 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wiwattanacheewin, K. S. S. et al. Predictors of intention to use HIV testing service among sexually experienced youth in Thailand. AIDS Educ. Prev.27, 139–152 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Meadowbrooke, C. C., Veinot, T. C., Loveluck, J., Hickok, A. & Bauermeister, J. A. Information behavior and HIV testing intentions among young men at risk for HIV/AIDS. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol.65(3), 609–620 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ayodele, O. The theory of planned behavior as a predictor of HIV testing intention. Am. J. Health Behav.41(2), 147–151 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bernard Njau GM, Damian Jeremiahb DM. Correlates of sexual risky behaviours, HIV testing, and HIV testing intention among sexually active youths in Northern Tanzania. East Afr. Health Res. J.5(2), (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 77.Abamecha, F., Godesso, A. & Girma, E. Predicting intention to use voluntary HIV counseling and testing services among health professionals in Jimma, Ethiopia, using the theory of planned behavior. J. Multidiscip. Healthc.6, 399–407 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Idris, A. M., Crutzen, R. & Van den Borne, H. W. Psychosocial beliefs related to intention to use HIV testing and counselling services among suspected tuberculosis patients in Kassala state, Sudan. BMC Public Health21(1), 75 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pakpour, A. H., Mo, P. K. H., Lau, J. T. F., Xin, M. & Fong, V. W. I. Understanding the barriers and factors to HIV testing intention of women engaging in compensated dating in Hong Kong: The application of the extended Theory of Planned Behavior. PLoS One14(6), (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 80.Jia, M. Information Exposure to HIV Testing Technologies and Testing Intentions among Undergraduates in Beijing (University of Illinois, Chicago, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 81.Evangeli, M. et al. A systematic review of psychological correlates of HIV testing intention. AIDS Care30(1), 18–26 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Musumari, P. M. et al. Factors associated with HIV testing and intention to test for HIV among the general population of Nonthaburi Province, Thailand. PLoS One15(8), e0237393 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gagnon, M., French, M. & Hebert, Y. The HIV self-testing debate: Where do we stand?. BMC Int. Health Hum. Rights18(1), 5 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Harichund, C. & Moshabela, M. Acceptability of HIV self-testing in sub-Saharan Africa: Scoping study. AIDS Behav.22(2), 560–568 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Koris, A. L. et al. Youth-friendly HIV self-testing: Acceptability of campus-based oral HIV self-testing among young adult students in Zimbabwe. PLoS One16(6), e0253745 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Aizobu, D. et al. Enablers and barriers to effective HIV self-testing in the private sector among sexually active youths in Nigeria: A qualitative study using journey map methodology. PLoS One18(4), e0285003 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nambusi, K. et al. Youth and healthcare workers’ perspectives on the feasibility and acceptability of self-testing for HIV, hepatitis and syphilis among young people: Qualitative findings from a pilot study in Gaborone, Botswana. PLoS One18(7), e0288971 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sircar, N. R. & Maleche, A. A. Perspectives on HIV self-testing among key and affected populations in Kenya. Afr. Health Sci.22(2), 37–45 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.