Abstract

Seven yeast strains were isolated from Tunisian dates. The strains were identified by sequence analysis of the D1/D2 domain of the nuclear large subunit (LSU) rRNA gene. Based on this all strains in the study were almost identical with that of the type strain of Wickerhamomyces subpelliculosus (CBS 5767) indicating that they belong to this species. All strains were characterized physiologically and biochemically. All strains grew in the presence of 50 % sucrose, 10 % sodium chloride and at 42 °C. The potential of these yeasts as biocontrol agent against mycotoxigenic Penicillium species inhabiting date, was evaluated. All yeast strains inhibited the growth of P. citrinum P10 and P. chrysogenum C17 previously isolated from dates, with inhibition percentages ranging between 43.6 % and 70.3 % on dual culture plate assays. Moreover, the volatile compounds (VCs) produced by these yeasts inhibited the mycelial growth rate and sporulation of both fungus strains, up to 76.5 and 100 %, respectively, on inverted culture plate assay. The VCs of W. subpelliculosus strains Y4 and Y24, which exhibit strong inhibitory activity against toxigenic Penicillium, were determined by head-space solid-phase microextraction (HS-SPME) combined with gas chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (GC–MS) analysis. Results revealed significant levels of alcohols (27.36 % for Y4 and 23.35 % for Y24) and esters (66.19 % for Y4 and 75.82 % for Y24). Their significant bioactivity, along with the lack of reported adverse effects on consumer health or the environment, makes them a sustainable and effective alternative to synthetic fungicides for the biocontrol of mycotoxigenic Penicillium affecting stored dates.

Keywords: Dates, Penicillium, Wickerhamomyces subpelliculosus, Yeast volatile compounds, Antifungal activity

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Seven Wickerhamomyces subpelliculosus yeast strains were isolated from dates.

-

•

All yeasts grew in the presence of 50 % sucrose, 10 % sodium chloride and at 42 °C.

-

•

W. subpelliculosus showed antagonistic potential against mycotoxigenic Penicillium.

-

•

W. subpelliculosus strains volatile compounds exhibited antifungal activity.

-

•

Volatile compounds of W. subpelliculosus strains consisted of alcohols and esters.

1. Introduction

Date, the fruit of the date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.), is an emblematic fruit of several countries like Tunisia, Saudi Arabia, Iran, Egypt, Iraq, Pakistan and Algeria [1]. The date sector in these regions contributes a lot to the national and international economy [2]. Currently, Tunisia is the world's leading exporter of dates in terms of value and quality. Tunisia's oases harbor more than 200 varieties of dates. The most widely produced is the variety “Deglet Nour”, which is considered as a luxury product and constitutes almost all of the exported date tonnages [3]. Today, the export of dates to Europe is increasing, and almost all of the exported quantity is addressed to France, Germany, Italy, Spain and United Kingdom. Indeed, Tunisia and Algeria are the main exporters of dates to the European market with a share of 75 % in all dates delivered to the European Union (EU) [4]. Dates represent a rich source of essential nutrients: carbohydrates, proteins, fibers, vitamins, minerals such as potassium and iron, and antioxidants [5]. In addition, dates have medicinal benefits which can be used for the treatment of gastrointestinal diseases and for the prevention against diabetes, cystitis, hepatic and cardiovascular problems. They also have anti-inflammatory and immunostimulant effects [6]. However, dates, like many other agricultural products, are subject to fungal spoilage before, during, and after harvest, as well as during transportation and storage. Pathogenic fungi in dates are essentially Aspergillus spp., Penicillium spp. and Cladosporium spp [7]. Contamination of dates by fungi causes significant economic losses and quality issues. In addition, the majority of pathogenic fungi in dates produce several mycotoxins that can lead to serious health problems [8]. Among the toxins are ochratoxin A (OTA) which possesses nephrotoxic, genotoxic, carcinogenic, teratogenic and immunosuppressive effects [9], aflatoxin B1 (AFB1) which is considered a potent hepatocarcinogen and classified by the International Agency of Research on Cancer (IARC) as a group1 carcinogen [10] and citrinin with high nephrotoxic action [11]. The main ochratoxigenic species are A. ochraceus, A. westerdijkiae, A. niger, A. carbonarius P. verrucosum and P. nordicum [12]. However, some studies have shown that P. chrysogenum also produces OTA [13,14]. Aspergillus flavus and Aspergillus parasiticus are considered the main species producers of AFB1 [15]. Moreover, P. citrinum and P. chrysogenum are known to secrete citrinin [16,17].

In the context of global food safety and security, it is imperative to control mycotoxigenic fungi in date fruits given date's widespread applications as raw materials in the food industry. The predominant method for managing these postharvest pests is the application of chemical fungicide. However, because of their high residual content toxicity, persistence and various detrimental effects on human health, their application is restricted by laws and regulations [18]. The search for natural antimicrobial compounds inhibiting spoilage fungi growth in fresh and dried fruits, is crucial. Several natural alternatives to synthetic antifungal agents have been proposed such as the use of microorganisms. Yeasts emerge as promising biocontrol agents against postharvest fruit rot, exhibiting significant potential in inhibiting the growth of filamentous fungi. It was reported that Aureobasidium pullulans and Sporidiobolus pararoseus have proved high controlling potential in postharvest decay of fruits [19,20]. Moreover, Ruiz-Moyano et al. (2016) [21] reported the antagonistic capacities of Hanseniaspora opuntiae and Metschnikowia pulcherrima, isolated from fig crops, to control the development of common postharvest spoilage fungi. Nally et al. (2012) [22] showed the capacity of Saccharomyces cerevisiae to control Botrytis cinerea which destroys the peel of table grapes. Other investigations proved the antifungal activity of Yarrowia lipolytica against P. chrysogenum [14] and of Debaryomyces hansenii against P. citrinum [23].

Dates serve as natural habitat for yeasts because of their high content of simple sugars, including glucose, fructose and sucrose, ranging from 73 % to 83 % of their dry weight. The majority of these yeasts are termed osmotolerant because they are able to grow in 50 % w/w sugar or higher [24]. Zygosaccharomyces, Saccharomyces, Candida, Debaryomyces, Lodderomyces, Meyerozyma, Wickerhamomyces, Torulaspora, Kluyveromyces, Hanseniaspora, and Pichia are the most well-known genera of osmotolerant yeasts that are found in fruits and their derived products [25,26]. Several osmotolerant yeasts utilize volatile compounds (VCs) against fungal plant pathogens due to their potent antifungal activity. Jaibangyang et al. (2020) [27] and Natarajan et al. (2022) [28,29] demonstrated the efficiency of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Candida spp. VCs to inhibit the mycelial growth of A. flavus. Moreover, several investigations showed antifungal activities of: Meyerozyma guilliermondii VCs against P. digitatum [30] and Hanseniaspora spp. VCs against toxigenic Aspergillus spp. [31].

The objectives of the current study are the characterization of yeast strains newly isolated from dates and the evaluation of their antifungal activities especially the antifungal potential of their CVs against P. citrinum and P. chrysogenum.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Dates sampling and yeasts isolation

In total, 84 date fruit samples (300–500 g) belonging to the variety “Deglet-Nour” were haphazardly collected in 2022 and 2023 from different Tunisian supermarkets. The samples were kept in sterile polyethylene bags at 4 °C. Fruits were washed with water, disinfected by immersion in a 2 % sodium hypochlorite solution for 1 min, and rinsed with distilled water to wash off residual hypochlorite, then, crushed with a sharp knife to extract seeds. 25 g of each date pulp sample was put in a sterile stomacher bag and homogenized using a stomacher (Lab-Blender 400 circulator, Seward Medical, England) with 225 mL of sterile peptone buffered water (BIO-RAD, France) for 5 min. Then, ten-fold serial dilutions were prepared. Subsequently, 100 μL of each dilution were plated on yeast extract peptone dextrose agar plates (YPD: yeast extract 10 g/L, peptone 20 g/L, dextrose 20 g/L, and agar 15 g/L; pH 5.5). The agar plates were incubated at 30 °C for up to 3 days. Each well-separated yeast colony was picked and streaked to obtain pure cultures. Then, each culture was examined microscopically.

2.2. Molecular yeast strains identification

Yeast isolates were identified by sequence analysis of the D1/D2 domain of the 26S rRNA gene [32,33]. Briefly, amplification of this domain was performed with the primers NL-1 (50 -GCATATCAATAAGCGGAGGAAAAG) and NL-4 (50 -GGTCCGTGTTTCAAGACGG) for 36 PCR cycles comprising an annealing phase at 52 °C, an extension phase at 72 °C for 2 min, and a final denaturation step at 94 °C for 1 min. The PCR products were purified with Geneclean II (Bio 101, La Jolla, Calif.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The sequencing of the purified PCR products was assured by Eurofins Genomics Germany GmbH, Germany. For yeast strains identification, a Blast search against the National Center for Biotechnology and Information (NCBI) genbank was performed (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). The closest related type strains sequences were downloaded and aligned with the sequences of the newly isolated strains using MAFFT [34].

2.3. Phenotypic characterization of yeast strains

2.3.1. Sugar fermentation test

The ability of the yeast strains to ferment glucose, fructose and saccharose was tested as described by Kurtzman et al. (2011) [35]. Incubation was done at 30 °C for 3 days. Beside the sugar the basic medium contained 10 g/L yeast extract and 20 g/L peptone 20 g/L. Thereafter, inoculated tubes were incubated at 30 °C for 3 days. Fermentation capacity of the different yeast strains was assessed as described by Matos et al. (2021) [36].

2.3.2. Tolerance to stress conditions

The isolated yeast stains were screened for their ability to grow in the presence of high sucrose or NaCl concentration. Assays were carried out in 20 mL test tubes with a working volume of 5 mL. Each tube was inoculated with 2 % of freshly prepared yeast suspension (initial concentration DO600 = 1.5). The basic medium was composed of 0.3 g/L KH2PO4; 0.1 g/L KCl; 0.6 g/L NaCl; 0.1 g/L CaCl2; 0.1 g/L MgCl2; 1 g/L NH4Cl; 1 g/L yeast extract and 1 mL oligo-elements solution (obtained by dissolving 0.1 g of B4O7Na2, 10H2O; 0.01 g of CuSO4, 5H2O; 0.05 g of FeSO4, 7H2O; 0.01 g of MnSO4, 4H2O; 0.07 g of ZnSO4, 7H2O and 0.01 g of (NH4)6Mo7O24, 4H2O in 1 L of distilled water). This medium was supplemented with sucrose to reach a final concentration of 50 % (w/v). The same medium containing 2 % (W/V) sucrose was used as positive control. To assess the salt tolerance of the different yeast strains, a medium containing 0.5 % yeast extract, 1 % peptone, 2 % glucose and 10 % NaCl (W/V) was used. The positive control did not contain NaCl. After incubation at 25 °C for 48 h the OD 600 was measured. The degrees of sucrose and salt tolerance were expressed as the ratio of the OD600 measured under test conditions by the OD600 measured in the positive control. Calculated degrees were multiplied by 100 to get the tolerance percentages.

The temperature tolerance of the yeast strains was assessed. To this end, the strains were incubated on YPD agar at 37, 40, 42 and 45 °C for 48 h. Tolerance to a certain temperature was indicated by visible growth. The test was done in three repetitions.

2.4. Penicillium strains

Thirty-five strains of Penicillium sp. were originally isolated from fruit samples belonging to the variety “Deglet-Nour” collected from different supermarkets in Tunisia. The strains were demonstrated to produce citrinin by analysis of methanol extracts. Analysis was done by HPLC as previously described [37]. The HPLC system was equipped with a C18 column (Waters Spherisorb 5 μm, ODS2, 4.6 × 250 mm, Milford MA, USA). Mycotoxin detection was achieved with a fluorescence detector (Waters 474, Milford, Massachusetts, U.S.A.) at λexc 330 nm and λem 500 nm. The mobile phase consisted of 10 mM phosphoric acid (pH = 2.5) - acetonitrile (50:50) with a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. Strains C17 and P10 produced the highest amounts of citrinin. They were selected for the further investigation. To determine the species of the two fungus strains, a molecular characterization was conducted by amplifying the internal transcribed spacer (ITS1-5.8S-ITS2) of ribosomal DNA (rDNA) via the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and subsequent amplicon sequencing. ITS region amplification was carried out by using ITS1 (5′-TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG-3′) and ITS4 (5′- TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3′) primers [38]. The PCR reaction mixture (total volume 20 μL) was composed of 4 μL of 5 × reaction buffer, 1.6 μL of MgCl2 (25 mM), 0.3 μL of dNTPs mix (10 mM), 0.3 μL of each primer (10 μM), 1 unit of GoTaq® DNA polymerase (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) and 100 ng of DNA template. Amplification was performed in VERITI thermocycler (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) with an initial denaturation at 94 °C for 3 min, followed by 35 cycles of 30 s denaturation at 94 °C, 45 s annealing (at 58 °C), 30 s extension at 72 °C, and a final extension at 72 °C for 7 min. Amplified products (10 μL) were then loaded on a 2 % (w/v) agarose gel with TAE buffer to check for successful amplification. After that, PCR products were purified and sequenced in both directions with the ITS primer pair (ITS1 and ITS4) as prescribed by the manufacturer (Genome Express, Grenoble, France). The resulting DNA sequences were analyzed as described above for the molecular yeast strains identification (section 2.2).

2.5. In vitro screening of antagonistic activity of yeasts against mycotoxigenic Penicillium: dual culture plate assay

The strong fermenting yeast strains with the highest tolerance to high sugar and salt concentrations as well as elevated temperatures (42 °C) were selected for evaluation of their antagonist activities against Penicillium strains P10 and C17 using dual culture technique [28]. First, the Penicillium strains were grown on potato dextrose agar (PDA) at 25 °C for 7 days. Spore suspensions were prepared in sterile distilled water containing Tween 80 (0.01 %) to reduce spore adhesion. Spore density was adjusted to a concentration of 106 spores/mL using a haemocytometer. The suspensions were stored at 4 °C until utilization [39]. The selected yeasts strains were grown on YPD broth at 25 °C for 48 h. Then, cells were recovered by centrifugation, washed, resuspended in Ringer's solution (0.9 % NaCl). Cell density was determined by means of a haemocytometer and adjusted to a final concentration of 1 × 108 cells/mL [40]. Thereafter, 10 μL of each yeast cell suspension (108 UFC/mL) were streaked orthogonally 2 cm from the edge of Petri dish (60 mm) containing PDA agar (pH 6.0) and incubated for 24 h at 25 °C. After incubation, 10 μl of spore suspension (106 conidia/mL) of each Penicillium strain were placed 2 cm from the opposite edge on the other half of the plate. Dual culture Petri dishes were incubated for 7 days at 25 °C. Positive controls solely inoculated with one of the Penicillium strains were also prepared as shown in Fig. 1. After incubation, mycelial growth reduction percentage was calculated in relation to growth of the control using formula (1):

| (1) |

where I (%) represented the inhibition of the mycelial growth, C was the mycelial width in the control (mm), and T was the mycelial width of fungus in the presence of yeast cultures (mm).

Fig. 1.

Dual culture plate assay for screening the antagonistic activity of isolated yeast strains against mycotoxigenic Penicillium strains.

The test was carried out three times for each yeast strain-Penicillium strain combination. The yeast strains reducing mycelial growth in the dual plate assay were selected for the inverted culture plate assay.

2.6. Inhibition effect of volatile compounds of selected yeast strains against mycelial growth and sporulation of Penicillium: inverted culture plate assay

The yeast strains selected by the dual culture plate assay were further examined in the inverted culture plate assay. In this test was conducted as described by Farbo et al. (2018) [40]. 50 μL of yeast cell suspension (108 cells/mL) were evenly spread on a YPD agar plate (60 mm diameter and incubated at 25 °C for 24 h. After incubation, 10 μL of Penicillium spore suspension (106 conidia/mL) was spotted on the center of an additional PDA agar plate of the same size and allowed to dry for 30 min at room temperature. After drying, the two plate on which the yeasts were grown and the plate on which the spores were placed were arranged face-to-face and firmly connected to each other with a double layer of Parafilm® and a single layer of adhesive tape. The plates were incubated at 25 °C for 7 days. A control treatment was done by replacing the plate with yeast on it by a plate that was not inoculated at all (Fig. 2). Three replicates were done for each yeast strain - Penicillium strain combination.

Fig. 2.

Inverted culture plate assay for testing the inhibition effect of yeast strains volatile compounds against mycelial growth of Penicillium strains.

Diameters of the growing Penicillium colonies were measured daily in two directions at right angles to each other. Colony diameters were plotted against time and the growth rate was calculated by linear regression and expressed in terms of mm/day [41]. The percentage of Penicillium mycelia growth rate inhibition was determined according to formula (2):

| (2) |

where C represented the mycelial growth rate of Penicillium strain in the control (mm/day), and T was the mycelial growth rate of Penicillium stain in combined culture with yeast strain (mm/day).

After mycelial growth was evaluated, all samples were analyzed for yeast influence on fungal spore production. The fungal spores produced in each plate were washed with 15 ml Tween 80 solution (0.01 %). Then spore suspension was collected and centrifuged for 5 min at 2000 g and 20 °C. The supernatant was discarded and re-centrifuged until 1 mL of highly concentrated spore suspension remained. After that, the conidial concentration was determined using a haemocytometer and the number of spores per cm2 of plate was calculated [42].

The following formula was employed in order to calculate the percent of sporulation inhibition:

where Nc represents the number of fungal spores produced in control plate and Nt is the number of fungal spores produced in treated plate with yeast VCs.

2.7. Analysis of yeast volatile compounds

Volatile compounds (VCs) produced by the effective yeast strains (Y4 and Y24) were analyzed by head-space solid phase microextraction (HS-SPME) combined with gas chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (GC–MS) analysis. For this, 100 μL of freshly grown yeast cell suspension were transferred into a 20 mL amber headspace vial containing 6 mL of YPD agar and sealed with a PTEE/silicone septum and an aluminum crimp and incubated at 26 °C for seven days. YPD agar without yeast served as a control. The yeast VOCs were collected using the SPME fiber (Carboxen/DVB/PDMS (2 cm) 50/30 μm commercially available from Agilent Technologies (USA)). The fiber was conditioned at 260 °C for 30 min in the hot injector of the GC and immediately exposed for 1 h at 25 °C to yeast VCs in the vials. The fiber was desorbed in the injector in splitless mode (5 min) with a transfer line temperature of 260 °C. Gas chromatography analysis was carried out using an Agilent 19091S-433: 2169.66548 GC coupled to an HP-5MS 5 % Phenyl Methyl Silox with a DB Wax capillary column (325 °C: 30 m × 250 μm × 0.25 μm), and Helium as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The ion source temperature was 230 °C, and the quadrupole temperature was 150 °C. The Oven temperature was maintained at 40 °C for 5 min initially, and then raised at the rate of 20 °C min−1 to 250 °C for 15 min. The identification of VCs was carried out by using the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and Wiley 275 reference libraries, and by comparing the retention times and mass spectra of authentic standards. The experiment was performed in three replicates per strain.

2.8. Statistical analysis

Tolerance to stress conditions, dual culture plate and inverted culture plate assays results were statistically evaluated by analysis of variance (ANOVA) using the IBM SPSS Statistics Package (version 20.0). Tukey test was used to assess the differences among the factor levels studied at 5 % significance level.

3. Results

3.1. Molecular identification of yeast isolates

The isolated yeast stains were identified by analyzing the sequences of D1/D2 domain. The results obtained revealed that these isolates belong to Wickerhamomyces subpelliculosus. When compared to the type strain (CBS 1996; accession number KY110141.1), the percentage of substitutions ranged from 97.99 to 100 % as follows for the different isolates: Y2 (99.0 %), Y4 and Y7 (97.99 %), Y6 and Y9 (100 %); Y24 (99.83 %) and Y15 (99.66 %). The accession numbers of strains Y2 (OR971895.2), Y4 (OR971897.2), Y6 (OR971898.1), Y7 (OR971899.2), Y9 (OR971901.1), Y15 (OR971904.1) and Y24 (OR971905.1) were obtained from the NCBI nucleotide database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore).

3.2. Phenotypic characterization of yeast strains

3.2.1. Fermentation capacity

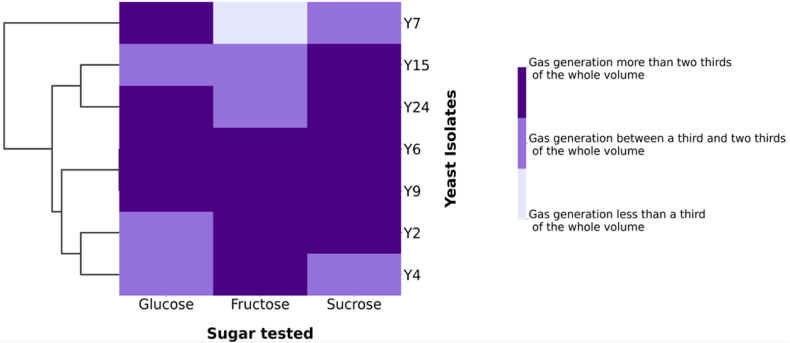

The capacity of the different yeast strains to ferment glucose, fructose and sucrose was compared. These three sugars are the major sugars present in date fruits. All yeasts strains were able to ferment each of sugar after 72 h incubation at 25 °C and generated a high volume of gas reaching from one third to two thirds of the total volume of the inverted Durham tube except of strain Y7 which slowly fermented fructose. In this case the gas volume generated was less than a third of the volume of the inverted tube (Fig. 3). The fermentative capacity differed between strains. Strains Y6, Y9 and Y12 strongly fermented all sugars. Strains Y2, Y15 and Y24 fermented sucrose stronger than strains Y4 and Y7 and strains Y24 and Y7 fermented glucose very strong compared to the other yeasts. Strains Y2 and Y4 fermented fructose stronger than the other strains.

Fig. 3.

Hierarchical cluster heatmap of sugar fermentation profile of the yeast strains after 72 h at 25 °C. Manhattan distance and average linkage were used to cluster the isolates based on their similarities in fermenting sugars. As depicted by the color on the scale bar indicating the level of gas generated from the fermentation process, dark-colored cells reflect a strong capability of the isolates to ferment sugars and light-colored cells reflect less important sugar fermentation.

3.2.2. Stress tolerance

Results relating to the tolerance of the isolated yeast strains to 50 % sucrose and 10 % NaCl are shown in Fig. 4(AandB). The results show that all strains could grow in an environment with a moderately high concentration of solute (50 % sucrose or 10 % NaCl). The ratio calculated from the OD under test conditions by the OD of the control was higher than 0.80 for all yeast strains. Strains Y2 and Y4 showed higher tolerance to 50 % sucrose than all other strains with tolerance percentages of 104 and 108 %, respectively. The tolerance percentage of tested yeasts to 10 % of NaCl is situated between 28 and 40 %. Thus, it is inferred that all tested yeasts were osmotolerant and halotolerant.

Fig. 4.

Tolerance of yeast isolates to: (A) 50 % sucrose, (B) 10 % NaCl, after 48 h of incubation at 25 °C.

Identical letters above the bars indicate no significant differences according Tukey test (p < 0.05).

The tolerance of the yeast strains investigated to different temperatures (25, 30, 37, 40, 42 and 45 °C) is given in Table 1. All yeast strains examined are highly thermotolerant as they grow at 40 °C and 42 °C.

Table 1.

Growth performance of yeast isolates at different temperatures after 48 h incubation.

| Yeast isolates |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y02 | Y04 | Y06 | Y07 | Y09 | Y15 | Y24 | |

| 25 °C | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 30 °C | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 37 °C | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 40 °C | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 42 °C | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 45 °C | – | w | w | w | – | w | – |

+ (growth), w (weak growth), - (no growth).

3.3. Molecular identification of selected fungus strains

The selected fungus strains were identified through sequencing the ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 (ITS) region. The ITS region sequences of strains C17 and P10 showed high identities, equal to 100 % and 99.2 %, with the ITS region sequences of the strains of Penicillium chrysogenum FG23 (MT601877.1) and Penicillium citrinum 4A14 (MN046972.1), respectively.

The GenBank accession numbers of the ITS region sequences for strain C17 and strain P10 are OR965294.1 and OR965295.1, respectively.

3.4. Antifungal activity of yeast isolates against P. chrysogenum C17 and P. citrinum P10

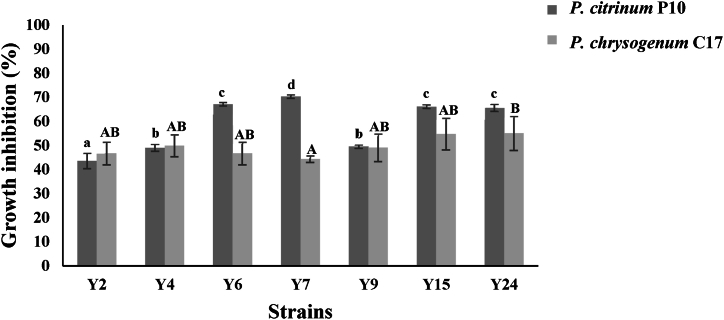

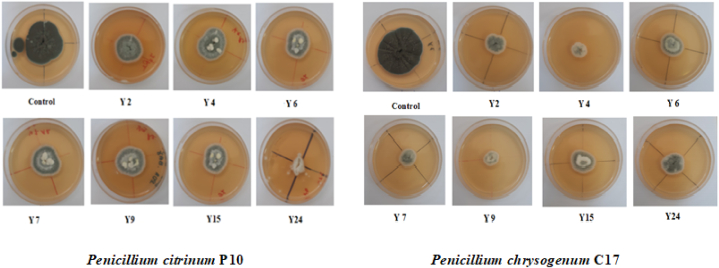

The effect of the newly isolated yeast strains on the growth of P. citrinum strain P10 and P. chrysogenum strain C17 was investigated by dual culture plate assay and the results are shown in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Percent inhibition in mycelial growth of P. citrinum P10 (A) and P. chrysogenum C17 (B) mycelial growth by yeasts in the dual plate assay after seven days of incubation at 25 °C.

Identical letters above the bars indicate no significant differences according to Tukey test (p < 0.05).

Yeast strain Y7 showed a stronger effect on the growth of P. citrinum strain P10 than the rest of the yeast strains included in the current investigation (p < 0.05). After seven days incubation in the presence of Wickerhamomyces subpelliculosus strain Y7, the growth of P. citrinum strain P10 was reduced by 70.31 % ± 0.74 % compared with its growth in the control without the yeast. Presence of yeast strains Y6, Y15 and Y24 reduced its growth to about 65 %

The effect of the tested yeasts on the growth of P. chrysogenum C17 demonstrated that all strains were able to inhibit the mycelial growth with a percentage of about 50 % after 7 days of incubation. Statistical analysis proved that there are no significant differences between strains (p > 0.05), except between Y7 and Y24. It is concluded that all tested yeasts have an antagonistic effect against Penicillium species included in the current study and reduced significantly their mycelial growth with inhibitions percentages between 43.6 and 70.3 % (p < 0.05). All strains were included in the inverted culture plate assay.

3.5. Effect of volatile compounds of antagonistic yeast strains on Penicillium growth and fungal spore production

The effect of the VCs of the strains selected in the dual plate assay on the growth rate and fungal spore production of P. citrinum strain P10 and P. chrysogenum strain C17 was investigated by inverted culture plate assay. Results are presented in Fig. 6 and Table 2. Statistical analysis showed that VCs of all selected strains inhibited significantly the growth rate of P. citrinum P10 (p < 0.05) with a growth reduction of more than 49 %. The strongest growth reduction was caused by strains Y7 and Y24. These strains inhibited significantly (p < 0.05) the mycelia growth rate of P. citrinum strain P10 to 2.13 ± 0.52 and 2.29 ± 0.52 mm/day corresponding to a reduction of 63.47 ± 8.91 and 60.85 ± 0.52 %, respectively, compared to the control treatment (5.84 ± 0.06 mm/day). The growth rate of P. chrysogenum strain C17 was significantly reduced (p < 0.05) by 46 %. In the presence of strains Y4 and Y9, the growth rate of P. chrysogenum strain C17 from 5.4 ± 0.2 to 1.3 ± 0.1 and 1.5 ± 0.2 mm/day, corresponding to a reduction of 76.5 ± 2.7 % and 71.9 ± 3 %, respectively.

Fig. 6.

Effect of the volatiles produced by different W. subpelliculosus strains on the growth of P. citrinum and P. chrysogenum after seven days incubation at 25 °C.

Table 2.

Effect of volatile compounds produced by different strains of W. subpelliculosus on the growth and spore production by P. citrinum strain P10 and P. chrysogenum strain C17 after 7 days of incubation on potato dextrose agar (PDA).

| W. subpelliculosus strains |

Penicillium citrinum strain P10 |

Penicillium chrysogenum strain C17 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Growth |

Spore production |

Growth |

Spore production |

|||||

| Growth rate (mm/day) | Percentage of inhibition (%) | Spore count (105 spores/cm2) | Percentage of inhibition (%) | Growth rate (mm/day) | Percentage of inhibition (%) | Spore count (105 spores/cm2) | Percentage of inhibition (%) | |

| Control | 5.8 ± 0.1a | 0a | 32.3 ± 1.4a | 0a | 5.4 ± 0.2a | 0a | 45.5 ± 3.9a | 0a |

| Y2 | 2.9 ± 0.1b | 50.9 ± 1.8b | 5.7 ± 0.4b | 82.4 ± 1.3b | 1.9 ± 0bd | 63.8 ± 0.1bd | 1.6 ± 0.4b | 96.5 ± 0.82b |

| Y4 | 2.8 ± 0.1bc | 52.7 ± 1.8bc | 6.3 ± 0.5b | 81.4 ± 0.53b | 1.3 ± 0.1c | 76.5 ± 2.7c | 0.3 ± 0.2b | 99.5 ± 0.3b |

| Y6 | 2.7 ± 0.1bc | 53.9 ± 1.6bc | 4.4 ± 0.5bc | 86.3 ± 1.6bc | 2.2 ± 0.1b | 59.9 ± 2.7b | 1.2 ± 0.2b | 97.4 ± 0.34b |

| Y7 | 2.3 ± 0.5cd | 60.8 ± 8.9cd | 2.8 ± 0.6c | 91.5 ± 1.9c | 1.8 ± 0.1de | 66.6 ± 1.0de | 1.4 ± 0.3b | 97.0 ± 0.7b |

| Y9 | 2.8 ± 0.1bc | 51.9 ± 1.8bc | 5.2 ± 0.7b | 84.0 ± 2.2b | 1.5 ± 0.2ce | 71.9 ± 3.0ce | 0.2 ± 0.1b | 99.3 ± 0.48b |

| Y15 | 2.7 ± 0.2bc | 53.9 ± 3bc | 5.8 ± 0.6b | 82.0 ± 1.9b | 2.5 ± 0.4f | 53.2 ± 6.9f | 2.1 ± 0.2b | 95.3 ± 0.5b |

| Y24 | 2.1 ± 0.5d | 63.5 ± 8.9d | 0.0 ± 0.0d | 100 ± 0.0d | 2.3 ± 0bf | 57.6 ± 0.1bf | 1.2 ± 0.3b | 97.3 ± 0.6b |

a,b,c,d Values with the same superscript in the same column are not significantly different (p < 0.05) according to Tukey test for each fungus. Each value is represented in terms of mean of three replicates ± Standard deviation.

After the incubation period, the number of fungal spores produced by mycotoxigenic Penicillium strains P. citrinum P10 and P. chrysogenum C17 was determined, as presented in Table 2. The results showed that volatile compounds (VCs) from all W. subpelliculosus strains significantly inhibited spore formation, with inhibition rates exceeding 81 % for P. citrinum P10 and 95 % for P. chrysogenum C17 (p < 0.05). The best results were achieved with strain Y24, which completely inhibited spore production by P. citrinum P10, allowing only hyphal development (Table 2, Fig. 6). Additionally, the inhibition of fungal mycelial growth by yeast VCs was correlated with a reduction in the number of spores (Table 2).

3.6. Profiling of yeast volatile compounds

The compounds present in the volatiles of yeast strains Y4 and Y24 presented high antifungal activity against P. citrinum P10 and P. chrysogenum C17, respectively, in inverted-plate culture assay, were identified using HS-SPME combined with GC–MS (Table 3). The volatile compounds profiles of the efficient strains Y4 and Y24 showed high abundances of alcohols: 27.36 and 23.35 %, respectively, and esters: 66.19 and 75.82 %, respectively. The most abundant compounds in the VOCs of the analyzed yeasts were identified as ethyl acetate (49,63 ± 2,16 for Y4 and 53,24 ± 3,15 % for Y24), ethanol (23.15 ± 2.25 for Y4 and 21.05 ± 1.25 for Y24) and 1-Butanol, 3-methyl, acetate (10.43 ± 1.26 % for Y4 and 13.54 ± 2.08 % for Y24). Furthermore, these strains generated notable amounts of 2-Phenylethanol; octanoic acid, ethyl ester; and decanoic acid, ethyl ester (situated between 2 and 5 %).

Table 3.

Volatile compounds emitted by the efficient W. subpelliculosus strains Y4 and Y24 detected by HS-SPME-GC-MS analysis.

| Compounds | Abundance (%) ± S. E |

Molecular formula | Molecular weight (g.mol−1) | Retention time (min) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y4 | Y24 | ||||

| Alcohols | |||||

| Ethanol | 23.15 ± 2.25 | 21.05 ± 1.25 | C2H6O | 46.07 | 2.06 |

| 1-Pentanol | 0.5 ± 0.06 | 0.3 ± 0.02 | C5H12O | 88.15 | 3.05 |

| 3-Methyl-1-butanol | 0.49 ± 0.03 | 0.5 ± 0.01 | C5H12O | 88.15 | 3.22 |

| Dimethylsilanediol | 0.20 ± 0.01 | 0.18 ± 0.04 | C2H8O2Si | 92.16 | 3.97 |

| 2-Phenylethanol | 3.02 ± 0.35 | 2.32 ± 0.21 | C8H10O | 122.164 | 12.13 |

| Esters | |||||

| Ethyl acetate | 49.63 ± 2.16 | 53.24 ± 3.15 | C4H8O2 | 88.11 | 2.22 |

| 1-Butanol, 3-methyl-, acetate | 10.43 ± 1.26 | 13.54 ± 2.08 | C7H14O | 130.18 | 6.15 |

| Octanoic acid, ethyl ester | 2.98 ± 0.66 | 3.64 ± 0.52 | C10H20O2 | 172.27 | 13.89 |

| Hexanoic acid, 3-methylbutyl ester | 0.34 ± 0.19 | 0.25 ± 0.02 | C11H22O2 | 186.29 | 14.98 |

| Nonanoic acid, ethyl ester | 0.19 ± 0.05 | 0.23 ± 0.04 | C11H22O2 | 186.29 | 15.92 |

| ethyl 9-decenoate | 0.22 ± 0.05 | 0.32 ± 0.01 | C12H22O | 198.30 | 17.67 |

| Decanoic acid, ethyl ester | 2.4 ± 0.84 | 4.6 ± 0.92 | C12H24O2 | 200.32 | 17.84 |

Abundance (%) represents the mean of three replicates ± standard deviation.

4. Discussion

Because of their richness in sugar, date fruits are a suitable habitat for osmotolerant yeasts [43]. In this study, we isolated 11 yeast strains from different samples of dates of the variety “Deglet-Nour”. In their D1/D2 domain almost all isolated strains were in full agreement with the D1/D2 domain of the type strain of W. subpelliculosus. The difference detected in the two strains Y2 and Y4 was restricted to a 1bp indel. Therefore, according to the results of Kurtzman and Robnett (1998) [33] and Vu et al. (2016) [44] all strains could be definitively assigned to W. subpelliculosus. This species was often isolated from date suggesting it as a common yeast species in dates, and has demonstrated probiotic properties [45].

The capacity to ferment glucose, fructose and sucrose of all newly isolated W. subpelliculosus strains was investigated. All strains were able to ferment all sugars. Strains Y6, Y9 and Y12 exhibited an outstanding vigorous fermentation of all sugars.

The results suggest that W. subpelliculosus ferments strongly similar to W. anomalus. The fermentation behavior of W. anomalus was thoroughly investigated by Ben Atitallah et al. (2020) [46].

The tolerance of all yeast strains to grow in the presence of 50 % sucrose or in the presence of 10 % NaCl was investigated. All strains grew well in the presence of 50 % sucrose. Strain Y2 and strain Y4 grew better in the presence of 50 % sucrose than in standard medium that contained 2 % sucrose indicating that the strains are not only osmotolerant but true osmophilic. Naturally, a yeast that requires high sugar concentrations for optimal growth does not occur in high osmotic habitats sporadically. True osmophily is a sign that a yeast strain inhabits such habitats permanently. Strong osmotolerance of W. subpelliculosus was reported before by Niu et al. (2016) [24]. The tolerance to 10 % NaCl was similarly strong in all strains.

The ability of the isolated strains to grow at high temperatures was tested. All strains grew at 42 °C but not at 45 °C indicating that they are thermotolerant [47]. Similarly, for strains of W. anomalus isolated from fruits growth at 44 °C was described by Hawaz et al. (2022) [48]. Growth at temperatures of 42 °C or above is rare among yeasts. According to Murata et al. (2015) [49] the application of thermotolerant yeasts in a range of industrial food uses including drying is advantageous, since the drying process usually involves exposure to high temperatures, their thermotolerance trait enables them to survive.

Potential antifungal activity of the newly isolated W. subpelliculosus strains was investigated. As representatives of typical molds on date fruits P. citrinum strain P10 and P. chrysogenum strain C17 were used. In a first approach all strains were included in a dual plate assay. In this assay all yeast strains inhibited the growth of P. citrinum strain P10 and P. chrysogenum strain C17 by 43,6 % and formed an inhibition zone. The antagonistic actions of yeasts against various fungal strains were proved in several investigations. Öztekin & Karbancioglu-Guler, (2023) [50] [51] showed the antifungal activity of Hanseniaspora uvarum, Meyerozyma guilliermondii and Metschnikowia aff. Pulcherrima against Penicillium digitatum which causes green mold in mandarins. Prendes et al. (2021) [51] suggested the antifungal ability of Metschnikowia sp. yeasts against Alternaria alternata. Additionally, Alimadadi et al. (2023) [52] demonstrated the efficiency of Geotrichum candidum against P. expansum which causes blue mold decay in table grapes. Cabañas et al. (2020) [53] reported the antagonistic activity of Pichia terricola, Aureobasidium pullulans, and Zygoascus meyerae against Penicillium glabrum. Moreover, the antagonist activity of Wickerhamomyces sp. against Botrytis cinerea was proved in vitro by Parafati et al. (2015) [54].

Antagonistic yeasts were characterized by the production VCs which have the capacity to inhibit the growth of mycotoxigenic fungi [28,40]. Furthermore, in second approach, volatile compounds of yeasts were tested by inverted culture plate assay against mycelial growth and sporulation of P. citrinum strain P10 and P. chrysogenum strain C17. The VCs of all tested W. subpelliculosus strains exhibited antifungal activity against mycotoxigenic Penicillium strains by inhibiting the growth rate with a percentage situated between 50 and 64 % for P. citrinum P10 and 57 and 77 % for P. chrysogenum C17, and sporulation with a high percentage situated between 81.4 and 100 % for P. citrinum P10 and 95.3 and 99.5 % for P. chrysogenum C17. Results regarding the ability of VCs of W. subpelliculosus strains to inhibit fungal spore production are promising, as mycotoxin synthesis has been probably linked to sporulation according to Brodhagen et al. (2006) [55]. In this context, previous studies reported the relationship between mycotoxin production and sporulation in several mycotoxigenic genera [51,56]. It was reported that the genes responsible for mycotoxin biosynthesis are frequently regulated in conjunction with those involved in sporulation [57,58]. Furthermore, reducing sporulation limited the fungal spread by decreasing the spore load in the atmosphere and on susceptible surfaces [59]. Consequently, inhibiting spore production effectively minimizes the contamination of dates and its derived products with mycotoxigenic Penicillium and associated mycotoxins.

The effectiveness of VCs of yeasts belonging to the genera Wickerhamomyces against a variety of phytopathogenic fungi, such as A. carbonarius, A. flavus, Monilinia fructicola, P. digitatum, A. alternata, Colletotrichum spp. and Cladosporium spp. has been previously displayed by (Oro et al., 2018; Jaibangyang et al., 2020) [29,60]. However, no attempts have been performed to assess the efficiency of VCs produced by W. subpelliculosus against P. citrinum and P. chrysogenum. The current study revealed that the VCs produced by W. Subpelliculosus yeasts effectively inhibited the growth rate of P. citrinum P10 and P. chrysogenum C17.

The volatile fraction of Y7 and Y24 showed the best antifungal activity against P. citrinum P10 and inhibited its mycelial growth rate with percentages equals to 60.8 ± 8.9 % and 63.5 ± 8.9 % and spore production by 91.5 ± 1.9 % and 100 ± 0.0 %, respectively. Indeed, the VCs of W. subpelliculosus Y4 and Y9 high inhibited the growth rate of P. chrysogenum C17 with percentages equals to 76.5 ± 2.7 % and 71.9 ± 3 % and sporulation to 99.5 ± 0.3 and 99.3 ± 0.48, respectively. The analysis of volatile compounds (VCs) of yeast strains Y24 and Y4, which showed the high potential in controlling tested fungus strains P10 and C17, respectively, revealed that the yeast species W. subpelliculosus produced a variety of low molecular weight metabolites. According to Fialho et al. (2010) [61], these low molecular weight metabolites may play a crucial role in the control of mycotoxigenic fungi. Previous studies demonstrated that yeast VCs influence the protein expression and enzymatic activity of fungi, and their effectiveness may vary depending on the specific pathogen being targeted [62,63]. The volatile profiles of the effective strains Y4 and Y24 revealed high concentrations of alcohols: 27.36 % and 23.35 % and esters: 66.19 % and 75.82 %, respectively. According to Oro et al. (2018) [60], volatile compounds classified as esters and alcohols possess antifungal properties and are considered toxic to fungi. In this context, Fialho et al. (2016) [63] reported that the accumulation of solvents in the fungal plasma membrane causes the loss of essential metabolites, reducing the activity of enzyme associated with the membrane and uptake of nutrients, Furthermore, it might affect metabolic pathways that produce energy within cells, such as the tricarboxylic acid cycle and glycolysis, which in turn influence the growth of the envisioned pathogen. Moreover, the analysis of volatile compounds in W. subpelliculosus strains Y4 and Y24 revealed that these strains produced substantial amounts of ethyl acetate, with abundance percentages of 49.63 ± 2.16 % and 53.24 ± 3.15 %, respectively. Ethanol was also produced in significant quantities, with abundance percentages of 23.15 ± 2.25 % and 21.05 ± 1.25 %. This was followed by 1-Butanol, 3-methyl, acetate (10.43 ± 1.26 % and 13.54 ± 2.08 %, respectively). Additionally, these yeast strains produced notable concentrations of 2-Phenylethanol; octanoic acid, ethyl ester; and decanoic acid, ethyl ester. In this regard, the investigation performed by Oro et al. (2018) [60] demonstrated that according to a head space-gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (HS-GC–MS) analysis of VCs of W. anomalus, the major compound was ethyl acetate (792.9 mg/L), which was followed by isoamyl acetate (26.5 mg/L), additionally, it yields high concentrations of 2-phenylethanol and isobutanol (10–15 mg/L) and low concentrations of ethyl butyrate, ethyl hexanoate and phenyethyl acetate (0–5 mg/L). Moreover, the authors proved that the vapors of ethyl acetate completely inhibited the growth of B. cinerea. Besides, Natarajan et al. (2022) [28] demonstrated that the volatile compound (VC) profile of S. cerevisiae strains contained high levels of alcohols (approximately 50 %), esters (around 23 %), and acids (about 6 %), which could inhibit the growth, sporulation, and aflatoxin production in Aspergillus flavus. The most abundant compounds identified were 1-pentanol (estimated at 38 %) and ethyl acetate (around 22 %). Additionally, S. cerevisiae produced various antimicrobial compounds, including 1-propanol, 1-pentanol, ethyl hexanol, 2-methyl-1-butanol, ethanol, ethyl acetate, dimethyl trisulfide, p-xylene, styrene, and 1,4-pentadiene. The evaluation of the antifungal potential of ethyl acetate, 1-butanol and ethanol against A. flavus, revealing the high efficiency of ethyl acetate and 1-butanol in inhibiting the mycelial growth (40.7 % and 66.7 %, respectively) and aflatoxin production (99.4 % and 93.6 %), whereas ethanol did not exhibit high antifungal and anti-aflatoxigenic activities [28]. In addition, Liu et al., 2022 [64] suggested the capacity of ethyl acetate to inhibit the mycelial growth of Phytophthora nicotianae, which causes tomato fruit rot, by damaging cell membrane of the fruit's cells. Several studies, reported that the 2-phenylethanol plays an important role in the antagonistic activity of W. anomalus against A. carbonarius and A. ochraceus [40]. Additionally, it affects spore germination, growth, toxin production, and gene expression in Aspergillus flavus [65]. Furthermore, Natarajan et al. (2022) [28] demonstrated that the volatile compounds (VCs) profile of Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains contained high levels of alcohols (approximately 50 %), esters (around 23 %), and acids (about 6 %), which could inhibit the growth, sporulation, and aflatoxin production in Aspergillus flavus. The most abundant compounds identified were 1-pentanol (estimated at 38 %) and ethyl acetate (around 22 %). Additionally, S. cerevisiae produced various antimicrobial compounds, including 1-propanol, 1-pentanol, ethyl hexanol, 2-methyl-1-butanol, ethanol, ethyl acetate, dimethyl trisulfide, p-xylene, styrene, and 1,4-pentadiene. The evaluation of the antifungal potential of ethyl acetate and ethanol against A. flavus, revealing that ethyl acetate exhibited significant antifungal and anti-aflatoxigenic activities, whereas ethanol did not. Additionally, Parafati et al., 2015 [54] showed that volatile compounds (VCs) produced by W. anomalus and S. cerevisiae exhibited inhibitory effects on the growth of the pathogenic mold B. cinerea, both in vitro and in vivo. Therefore, the production of antifungal volatile compounds (VCs) by yeasts could serve as a crucial method for managing postharvest fruits, particularly in airtight environments [66]. Accumulated carbon dioxide and reduced oxygen levels might also contribute to inhibiting fungal growth and spore production by fungus [67]. Since, we did not assess these parameters in our experiments, we cannot entirely dismiss the possibility that competition for oxygen influences the yeast-fungus interaction. In this context, several studies suggested that the volatiles of yeasts act as microbial biocontrol agents that may decrease the incidence of toxigenic fungi through various mechanisms, including: induction of oxidative stress in fungal cells by producing reactive oxygen species, which damage cellular components like proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids, leading to cell death [63,68], and disruption of fungal cell membranes resulting in increased permeability and cell lysis, causing leakage of cellular contents and eventual cell death [69]. Additionally, VCs of yeasts can alter the metabolic pathways in fungi, disrupting their ability to regulate growth, spore germination and toxin production [70]. Moreover, some volatiles may inhibit key enzymes involved in mycotoxin biosynthesis [71].

5. Conclusion

Seven yeast strains, belonging to W. subpelliculosus species were found to be multi-stress tolerant (50 % sucrose, 10 % NaCl, high temperature 42 °C and to be well fermenting sucrose, glucose and fructose which are the major date sugars. Additionally, this work provided evidence for the antagonistic potential of date yeasts against P. citrinum and P. chrysogenum. Moreover, it was demonstrated that VCs produced by these yeasts reduced the growth rate and spore production of the molds. Therefore, it would be intriguing to investigate the efficacy of their application as tools for postharvest management of mycotoxigenic fungi. The great advantage of the yeasts compared to conventional preservatives would be that they don't leave any residues because their application does not require direct contact between the fruit's surface and the yeast cells. Finally, those compounds that are responsible for fungal inhibition should be further characterized to allow the design of improved artificial VCs mixtures with high efficiency.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Islem Dammak: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation. Nourelhouda Abdelkefi: Visualization, Methodology, Formal analysis. Imen Ben Atitallah: Methodology. Michael Brysch-Herzberg: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Conceptualization. Abdulrahman H. Alessa: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision. Salma Lasram: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision. Hela Zouari-Mechichi: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision. Tahar Mechichi: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Investigation.

Data availability statement

No data associated in this article has been deposited into a publicly available repository. The data supporting the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This research was carried out under the MOBIDOC scheme, funded by The Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research (Tunisia) through the PromESSE project and managed by the ANPR (Agence Nationale de la Promotion de la Recherche Scientifique).

Contributor Information

Islem Dammak, Email: Islem.dammak.a@gmail.com.

Nourelhouda Abdelkefi, Email: abdelkefinourelhouda@gmail.com.

Imen Ben Atitallah, Email: benatitallahimen@gmail.com.

Michael Brysch-Herzberg, Email: Michael.Brysch-Herzberg@hs-heilbronn.de.

Abdulrahman H. Alessa, Email: alessiabdulrahman@gmail.com.

Salma Lasram, Email: salma.lasram.cbbc@gmail.com.

Hela Zouari-Mechichi, Email: hela.zouari@isbs.usf.tn.

Tahar Mechichi, Email: tahar.mechichi@enis.rnu.tn.

References

- 1.Chandrasekaran M., Bahkali A.H. Valorization of date palm (Phoenix dactylifera) fruit processing by-products and wastes using bioprocess technology - review. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2013;20:105–120. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2012.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amani M.A., Davoudi M.S., Tahvildari K., Nabavi S.M., Davoudi M.S. Biodiesel production from Phoenix dactylifera as a new feedstock. Ind. Crops Prod. 2013;43:40–43. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2012.06.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chniti S., Djelal H., Hassouna M., Amrane A. Residue of dates from the food industry as a new cheap feedstock for ethanol production. Biomass Bioenergy. 2014;69:66–70. doi: 10.1016/j.biombioe.2014.07.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ghnimi S., Umer S., Karim A., Kamal-Eldin A. Date fruit (Phoenix dactylifera L.): an underutilized food seeking industrial valorization. NFS Journal. 2017;6:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.nfs.2016.12.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mohamed R.M.A., Fageer A.S.M., Eltayeb M.M., Mohamed Ahmed I.A. Chemical composition, antioxidant capacity, and mineral extractability of Sudanese date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) fruits. Food Sci. Nutr. 2014;2:478–489. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bouhlali E.T., Bammou M., Sellam K., Benlyas M., Alem C., Filali-Zegzouti Y. Evaluation of antioxidant, antihemolytic and antibacterial potential of six Moroccan date fruit (Phoenix dactylifera L.) varieties. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2016;28:136–142. doi: 10.1016/j.jksus.2016.01.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quaglia M., Santinelli M., Sulyok M., Onofri A., Covarelli L., Beccari G. Aspergillus, Penicillium and Cladosporium species associated with dried date fruits collected in the Perugia (Umbria, Central Italy) market. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2020;322 doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2020.108585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Azaiez I., Font G., Mañes J., Fernández-Franzón M. Survey of mycotoxins in dates and dried fruits from Tunisian and Spanish markets. Food Control. 2015;51:340–346. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2014.11.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.JECFA (Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives) Safety evaluation of certain mycotoxins in food. WHO Food Addit. Ser. 2008;59 [Google Scholar]

- 10.IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, International Agency for Research on Cancer Some naturally occurring substances: food items and constituents, heterocyclic aromatic amines and mycotoxins. World Health Organization, International Agency for Research on Cancer. 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu T.S., Yang J.J., Yu F.Y., Liu B.H. Evaluation of nephrotoxic effects of mycotoxins, citrinin and patulin, on zebrafish (Danio rerio) embryos. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2012;50:4398–4404. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2012.07.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang Y., Yan H., Neng J., Gao J., Yang B., Liu Y. The influence of NaCl and glucose content on growth and ochratoxin a production by Aspergillus ochraceus, Aspergillus carbonarius and Penicillium nordicum. Toxins. 2020;12(8) doi: 10.3390/toxins12080515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang X., Li Y., Wang H., Gu X., Zheng X., Wang Y., Diao J., Peng Y., Zhang H. Screening and identification of novel ochratoxin A-producing fungi from grapes. Toxins. 2016;8(11) doi: 10.3390/toxins8110333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang M., Zhao L., Zhang X., Dhanasekaran S., Abdelhai M.H., Yang Q., Jiang Z., Zhang H. Study on biocontrol of postharvest decay of table grapes caused by Penicillium rubens and the possible resistance mechanisms by Yarrowia lipolytica. Biol. Control. 2019;130:110–117. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2018.11.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lasram S., Zemni H., Hamdi Z., Chenenaoui S., Houissa H., Saidani Tounsi M., Ghorbel A. Seed essential oils and their major terpene component against Aspergillus flavus. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019;134:11–18. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2019.03.037. Antifungal and antiaflatoxinogenic activities of Carum carvi L., Coriandrum sativum L. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Z., Mao Y., Teng J., Xia N., Huang L., Wei B., Chen Q. Evaluation of mycoflora and citrinin occurrence in Chinese liupao tea. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020;68:12116–12123. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.0c04522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mohajeri F.A., Misaghi A., Gheisari H., Basti A.A., Amiri A., Ghalebi S.R., Derakhshan Z., Tafti R.D. The effect of Zataria multiflora Boiss Essential oil on the growth and citrinin production of Penicillium citrinum in culture media and cheese. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2018;118:691–694. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2018.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiménez M., Ignacio Maldonado M., Rodríguez E.M., Hernández-Ramírez A., Saggioro E., Carra I., Sánchez Pérez J.A. Supported TiO2 solar photocatalysis at semi-pilot scale: degradation of pesticides found in citrus processing industry wastewater, reactivity and influence of photogenerated species. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2015;90:149–157. doi: 10.1002/jctb.4299. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mari M., Martini C., Spadoni A., Rouissi W., Bertolini P. Biocontrol of apple postharvest decay by Aureobasidium pullulans. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2012;73:56–62. doi: 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2012.05.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Q., Li C., Li P., Zhang H., Zhang X., Zheng X., Yang Q., Apaliya M.T., Boateng N.A.S., Sun Y. The biocontrol effect of Sporidiobolus pararoseus Y16 against postharvest diseases in table grapes caused by Aspergillus Niger and the possible mechanisms involved. Biol. Control. 2017;113:18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2017.06.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ruiz-Moyano S., Martín A., Villalobos M.C., Calle A., Serradilla M.J., Córdoba M.G., Hernández A. Yeasts isolated from figs (Ficus carica L.) as biocontrol agents of postharvest fruit diseases. Food Microbiol. 2016;57:45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2016.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nally M.C., Pesce V.M., Maturano Y.P., Muñoz C.J., Combina M., Toro M.E., de Figueroa L.I.C., Vazquez F. Biocontrol of Botrytis cinerea in table grapes by non-pathogenic indigenous Saccharomyces cerevisiae yeasts isolated from viticultural environments in Argentina. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2012;64:40–48. doi: 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2011.09.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.González Estrada R.R., Ascencio Valle F. de J., Ragazzo Sánchez J.A., Calderón Santoyo M. Use of a marine yeast as a biocontrol agent of the novel pathogen Penicillium citrinum on Persian lime. Emir. J. Food Agric. 2017;29:114–122. doi: 10.9755/ejfa.2016-09-1273. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Niu C., Yuan Y., Hu Z., Wang Z., Liu B., Wang H., Yue T. Accessing spoilage features of osmotolerant yeasts identified from kiwifruit plantation and processing environment in Shaanxi, China. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2016;232:126–133. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2016.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tiwari S., Jadhav R., Avchar R., Lanjekar V., Datar M., Baghela A. Nectar yeast community of tropical flowering plants and assessment of their osmotolerance and xylitol-producing potential. Curr. Microbiol. 2022;79 doi: 10.1007/s00284-021-02700-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang H., Hu Z., Long F., Niu C., Yuan Y., Yue T. Characterization of osmotolerant yeasts and yeast-like molds from apple orchards and apple juice processing plants in China and investigation of their spoilage potential. J. Food Sci. 2015;80:M1850–M1860. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.12946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jaibangyang S., Nasanit R., Limtong S. Biological control of aflatoxin-producing Aspergillus flavus by volatile organic compound-producing antagonistic yeasts. BioControl. 2020;65:377–386. doi: 10.1007/s10526-020-09996-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Natarajan S., Balachandar D., Senthil N., Velazhahan R., Paranidharan V. Volatiles of antagonistic soil yeasts inhibit growth and aflatoxin production of Aspergillus flavus. Microbiol. Res. 2022;263 doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2022.127150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jaibangyang S., Nasanit R., Limtong S. Biological control of aflatoxin-producing Aspergillus flavus by volatile organic compound-producing antagonistic yeasts. BioControl. 2020;65:377–386. doi: 10.1007/s10526-020-09996-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Öztekin S., Karbancioglu-Guler F. Biological control of green mould on Mandarin fruit through the combined use of antagonistic yeasts. Biol. Control. 2023;180 doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2023.105186. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Galván A.I., Hernández A., Córdoba M. de G., Martín A., Serradilla M.J., López-Corrales M., Rodríguez A. Control of toxigenic Aspergillus spp. in dried figs by volatile organic compounds (VOCs) from antagonistic yeasts. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2022;376 doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2022.109772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brysch-Herzberg M., Seidel M. Yeast diversity on grapes in two German wine growing regions. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2015;214:137–144. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2015.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kurtzman C.P., Robnett C.J. 1998. Identification and Phylogeny of Ascomycetous Yeasts from Analysis of Nuclear Large Subunit (26S) Ribosomal DNA Partial Sequences. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Katoh K., Rozewicki J., Yamada K.D. MAFFT online service: multiple sequence alignment, interactive sequence choice and visualization. Brief Bioinform. 2018;20:1160–1166. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbx108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kurtzman C.P., Fell J.W., Boekhout T., Robert V. The Yeasts. Elsevier; 2011. Methods for isolation, phenotypic characterization and maintenance of yeasts; pp. 87–110. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matos Í.T.S.R., De Souza V.A., D'Angelo G.D.R., Astolfi Filho S., Do Carmo E.J., Vital M.J.S. Yeasts with fermentative potential associated with fruits of camu-camu (myrciaria dubia, kunth) from north of Brazilian amazon. Sci. World J. 2021;2021 doi: 10.1155/2021/9929059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dammak I., Lasram S., Hamdi Z., Ben Moussa O., Mkadmini Hammi K., Trigui I., Houissa H., Mliki A., Hassouna M. In vitro antifungal and anti-ochratoxigenic activities of Aloe vera gel against Aspergillus carbonarius isolated from grapes. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2018.07.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lasram S., Oueslati S., Ben Jouira H., Chebil S., Mliki A., Ghorbel A. Identification of ochratoxigenic aspergillus section nigri isolated from grapes by ITS-5.8S rDNA sequencing analysis and in silico RFLP. J. Phytopathol. 2013;161:280–283. doi: 10.1111/jph.12044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dammak I., Alsaiari N.S., Fhoula I., Amari A., Hamdi Z., Hassouna M., Ben Rebah F., Mechichi T., Lasram S. Comparative evaluation of the capacity of commercial and autochthonous Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains to remove ochratoxin a from natural and synthetic grape juices. Toxins. 2022;14(7) doi: 10.3390/toxins14070465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Farbo M.G., Urgeghe P.P., Fiori S., Marcello A., Oggiano S., Balmas V., Hassan Z.U., Jaoua S., Migheli Q. Effect of yeast volatile organic compounds on ochratoxin A-producing Aspergillus carbonarius and A. ochraceus. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2018;284:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2018.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dammak I., Hamdi Z., Kammoun El Euch S., Zemni H., Mliki A., Hassouna M., Lasram S. Evaluation of antifungal and anti-ochratoxigenic activities of Salvia officinalis, Lavandula dentata and Laurus nobilis essential oils and a major monoterpene constituent 1,8-cineole against Aspergillus carbonarius. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019;128:85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2018.11.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tzortzakis N.G., Economakis C.D. Antifungal activity of lemongrass (Cympopogon citratus L.) essential oil against key postharvest pathogens. Innovative Food Sci. Emerging Technol. 2007;8:253–258. doi: 10.1016/j.ifset.2007.01.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jdaini K., Alla F., M’hamdi H., Guerrouj K., Parmar A., Elhoumaizi M.A. Effect of harvesting and post-harvest practices on the microbiological quality of dates fruits (Phoenix dactylifera L.) Journal of the Saudi Society of Agricultural Sciences. 2022;21:552–559. doi: 10.1016/j.jssas.2022.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vu D., Groenewald M., Szöke S., Cardinali G., Eberhardt U., Stielow B., de Vries M., Verkleij G.J.M., Crous P.W., Boekhout T., Robert V. DNA barcoding analysis of more than 9 000 yeast isolates contributes to quantitative thresholds for yeast species and genera delimitation. Stud. Mycol. 2016;85:91–105. doi: 10.1016/j.simyco.2016.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Di Cagno R., Filannino P., Cantatore V., Polo A., Celano G., Martinovic A., Cavoski I., Gobbetti M. Design of potential probiotic yeast starters tailored for making a cornelian cherry (Cornus mas L.) functional beverage. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2020;323 doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2020.108591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ben Atitallah I., Ntaikou I., Antonopoulou G., Alexandropoulou M., Brysch-Herzberg M., Nasri M., Lyberatos G., Mechichi T. Evaluation of the non-conventional yeast strain Wickerhamomyces anomalus (Pichia anomala) X19 for enhanced bioethanol production using date palm sap as renewable feedstock. Renew. Energy. 2020;154:71–81. doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2020.03.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Techaparin A., Thanonkeo P., Klanrit P. High-temperature ethanol production using thermotolerant yeast newly isolated from Greater Mekong Subregion. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2017;48:461–475. doi: 10.1016/j.bjm.2017.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hawaz E., Tafesse M., Tesfaye A., Beyene D., Kiros S., Kebede G., Boekhout T., Theelen B., Groenewald M., Degefe A., Degu S., Admas A., Muleta D. Isolation and characterization of bioethanol producing wild yeasts from bio-wastes and co-products of sugar factories. Ann. Microbiol. 2022;72 doi: 10.1186/s13213-022-01695-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Murata Y., Danjarean H., Fujimoto K., Kosugi A., Arai T., Asma Ibrahim W., Suliman O., Hashim R., Mori Y. Ethanol fermentation by the thermotolerant yeast, Kluyveromyces marxianus TISTR5925, of extracted sap from old oil palm trunk. AIMS Energy. 2015;3:201–213. doi: 10.3934/energy.2015.2.201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Öztekin S., Karbancioglu-Guler F. Biological control of green mould on Mandarin fruit through the combined use of antagonistic yeasts. Biol. Control. 2023;180 doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2023.105186. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Prendes L.P., Merín M.G., Zachetti V.G.L., Pereyra A., Ramirez M.L., Morata de Ambrosini V.I. Impact of antagonistic yeasts from wine grapes on growth and mycotoxin production by Alternaria alternata. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2021;131:833–843. doi: 10.1111/jam.14996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Alimadadi N., pourvali Z., Nasr S., Fazeli S.A.S. Screening of antagonistic yeast strains for postharvest control of Penicillium expansum causing blue mold decay in table grape. Fungal Biol. 2023;127:901–908. doi: 10.1016/j.funbio.2023.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cabañas C.M., Hernández A., Martínez A., Tejero P., Vázquez-Hernández M., Martín A., Ruiz-Moyano S. Control of Penicillium glabrum by indigenous antagonistic yeast from vineyards. Foods. 2020;9 doi: 10.3390/foods9121864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Parafati L., Vitale A., Restuccia C., Cirvilleri G. Biocontrol ability and action mechanism of food-isolated yeast strains against Botrytis cinerea causing post-harvest bunch rot of table grape. Food Microbiol. 2015;47:85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2014.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brodhagen M., Keller N.P. Signalling pathways connecting mycotoxin production and sporulation. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2006;7:285–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2006.00338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Calvo A.M., Wilson R.A., Bok J.W., Keller N.P. Relationship between secondary metabolism and fungal development. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2002;66:447–459. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.66.3.447-459.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Trail F. For blighted waves of grain: Fusarium graminearum in the postgenomics era. Plant Physiol. 2009;149:103–110. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.129684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Calvo J., Calvente V., de Orellano M.E., Benuzzi D., Sanz de Tosetti M.I. Biological control of postharvest spoilage caused by Penicillium expansum and Botrytis cinerea in apple by using the bacterium Rahnella aquatilis. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2007;113:251–257. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tzortzakis N.G., Economakis C.D. Antifungal activity of lemongrass (Cympopogon citratus L.) essential oil against key postharvest pathogens. Innovative Food Sci. Emerging Technol. 2007;8:253–258. doi: 10.1016/j.ifset.2007.01.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Oro L., Feliziani E., Ciani M., Romanazzi G., Comitini F. Volatile organic compounds from Wickerhamomyces anomalus, Metschnikowia pulcherrima and Saccharomyces cerevisiae inhibit growth of decay causing fungi and control postharvest diseases of strawberries. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2018;265:18–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2017.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fialho M.B., Toffano L., Pedroso M.P., Augusto F., Pascholati S.F. Volatile organic compounds produced by Saccharomyces cerevisiae inhibit the in vitro development of Guignardia citricarpa, the causal agent of citrus black spot. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010;26:925–932. doi: 10.1007/s11274-009-0255-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mari M., Martini C., Spadoni A., Rouissi W., Bertolini P. Biocontrol of apple postharvest decay by Aureobasidium pullulans. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2012;73:56–62. doi: 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2012.05.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fialho M.B., de Andrade A., Bonatto J.M.C., Salvato F., Labate C.A., Pascholati S.F. Proteomic response of the phytopathogen Phyllosticta citricarpa to antimicrobial volatile organic compounds from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol. Res. 2016;183:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2015.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liu Z., Tian J., Yan H., Li D., Wang X., Liang W., Wang G. Ethyl acetate produced by Hanseniaspora uvarum is a potential biocontrol agent against tomato fruit rot caused by Phytophthora nicotianae. Front. Microbiol. 2022;13(978920) doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.978920. https://doi:10.3389/fmicb.2022.978920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hua S.S.T., Beck J.J., Sarreal S.B.L., Gee W. The major volatile compound 2-phenylethanol from the biocontrol yeast, Pichia anomala, inhibits growth and expression of aflatoxin biosynthetic genes of Aspergillus flavus. Mycotoxin Res. 2014;30:71–78. doi: 10.1007/s12550-014-0189-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Huang R., Li G.Q., Zhang J., Yang L., Che H.J., Jiang D.H., Huang H.C. Control of postharvest Botrytis fruit rot of strawberry by volatile organic compounds of Candida intermedia. Phytopathology. 2011;101:859–869. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-09-10-0255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schalchli H., Hormazabal E., Becerra J., Birkett M., Alvear M., Vidal J., Quiroz A. Antifungal activity of volatile metabolites emitted by mycelial cultures of saprophytic fungi. Chem. Ecol. 2011;27:503–513. doi: 10.1080/02757540.2011.596832. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mauricio B.F., Giselle C., Paula F.M., Ricardo A.A., Srgio F.P. Antioxidative response of the fungal plant pathogen Guignardia citricarpa to antimicrobial volatile organic compounds. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 2014;8:2077–2084. doi: 10.5897/ajmr2014.6719. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yalage Don S.M., Schmidtke L.M., Gambetta J.M., Steel C.C. Volatile organic compounds produced by Aureobasidium pullulans induce electrolyte loss and oxidative stress in Botrytis cinerea and Alternaria alternata. Res. Microbiol. 2021;172 doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2020.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Oufensou S., Ul Hassan Z., Balmas V., Jaoua S., Migheli Q. Perfume Guns: potential of yeast volatile organic compounds in the biological control of mycotoxin-producing fungi. Toxins. 2023;15 doi: 10.3390/toxins15010045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Abdallah M.F., Ameye M., De Saeger S., Audenaert K., Haesaert G. Mycotoxins - Impact and Management Strategies. IntechOpen; 2019. Biological control of mycotoxigenic fungi and their toxins: an update for the pre-harvest approach. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No data associated in this article has been deposited into a publicly available repository. The data supporting the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.