Thelaziosis is a zoonotic parasitic disease reported in humans and animals, caused by species of Thelazia [1]. In humans, although neglected, it has sporadically been reported [2], rarely in Latin America, including animals [3]. Some species were described only in some regions, e.g., Thelazia callipeda in Asia, Europe and North America [2].

Thelazia spp. may parasitise the orbital cavity, sheltering in the conjunctival sac, nictitating membranes, cornea, ducts and lacrimal glands [4]. Thelazia infection is rarely reported in Neognathae birds.

The present report describes the first record of an ocular infection in Colombia due to T. lacrymalis in a harpy eagle confirmed by genome sequencing.

In 2023, a Harpia harpyja (7.8 kg) was brought from the army to our Wildlife Center (Florencia, Caqueta, Colombia) after being found in Solita (109 km from Florencia, Caqueta), presenting an open fracture of the left thoracic limb at the ulna and radius (Fig. 1), with loss of continuity of the skin, its muscle with a foul odor and greenish colour, and trauma to the left pelvic limb with difficulty standing. Its temperature at income was 41 °C, heart rate of 220 bpm and respiratory rate of 69 rpm. Disinfection of the affected area was performed, immobilising the left thoracic limb. Tramadol orally was started for three days. The next day, sedation was done, and then the affected limb with an open fracture was amputated.

Fig. 1.

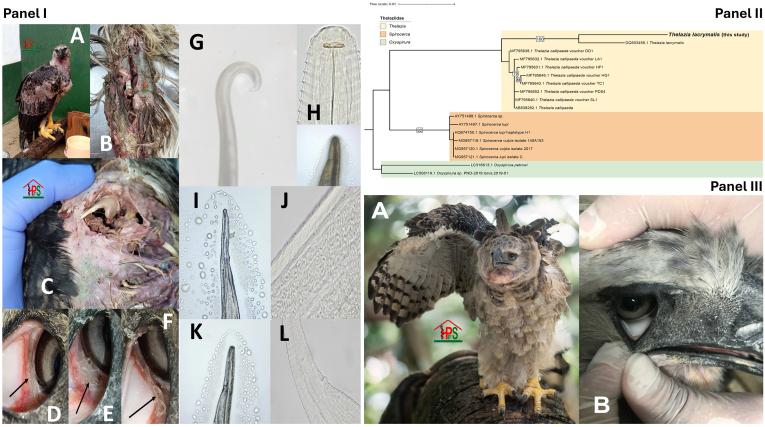

Panel I. Initial clinical findings of the harpy eagle (Harpia harpyja) show the vast lesions of the wing fracture. (A) General appearance of eagle at income. (B). Open fracture of the left thoracic limb at the ulna and radius. (C) Image showing distal fractures of the bones of the left wing. (D, E and F) Nematodes found in the conjunctival sac of the lower forces in the eagle's right eye (black arrows). Morphological findings of the nematode suggest Thelazia (G, H, I, J, K, L). Panel II. Phylogenetic analysis showing the Thelazia lacrymalis sequence obtained from the nematodes of the harpy eagle (https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4798430). Panel III. Follow-up images of the general state of the harpy eagle (Harpia harpyja) and left eye (A) and right eye (B).

In the next 24 hours, the recovery of the amputated limb was assessed. Discomfort in both eyes was evident, constantly closing the nictitating membrane while exhibiting bilateral epiphora. An ophthalmological examination revealed the presence of mobile whitish worms in the conjunctival sac of the lower fornices, around the nasolacrimal duct, and in both corneas. These worms had a cylindrical body attenuated at both ends and measured 1–2 cm (Fig. 1). One hundred worms were extracted and preserved in alcohol at 70 % for analysis.

A blood count, including parasites and blood chemistry, revealed monocytosis, neutrophilia, and mild hyperproteinemia (Table 1). Coproparasitological analyses were done. Treatment with ivermectin (0.2 mg/kg) was started for seven days.

Table 1.

Laboratory test findings.

| Laboratory Tests | At income | One month later | Two months later | Reference interval and unitsa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complete blood counts | ||||

| Hematocrit | 32 | 33 | 32 | 30.69–36.17 % |

| Haemoglobin | 10.4 | 10.8 | 10.5 | 7.47–11.63 g/dl |

| Red blood cells | 1.28 | 1.72 | 1.43 | 1.21-1.74 × 106/μ1 |

| Mean corpuscular volume | 250 | 192 | 224 | 182.47–287.24 fl |

| Mean corpuscular haemoglobin concentration | 33 | 33 | 33 | 22.32–35.16 % |

| Mean corpuscular haemoglobin | 81 | 63 | 73 | 43.92–91.04 pg |

| Total proteins | 6.2 | 6.2 | 5.6 | 4.68–5.80 g/dL |

| Platelets | 160 | 132 | 118 | Not available |

| Leukocyte counts | 19.4 | 20.8 | 19.8 | 11.16-21.89 × 103/μ1 |

| Neutrophils % | 68 | 72 | 71 | 47.75–69.96 % |

| Lymphocytes % | 23 | 20 | 24 | 14.55–33.59 % |

| Monocytes % | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0–4.51 % |

| Eosinophils % | 5 | 6 | 4 | 0–20.88 % |

| Basophils % | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0–1.73 % |

| Neutrophil counts | 13.2 | 15 | 14.1 | 6.12-13.22 × 103/μ1 |

| Lymphocytes count | 4.5 | 4.2 | 4.8 | 1.69-6.36 × 103/μ1 |

| Monocytes count | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0-0.49 × 103/μ1 |

| Eosinophils count | 1 | 1.2 | 0.8 | 0.00-4.00 × 103/μ1 |

| Basophils count | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0-0.24 × 103/μ1 |

| Hemoparasites (Blood smear, Woo and Leukoplatelet Technique) | Extracellular structures compatible with microfilaria were observed in the sample examined. | No structures are compatible with hemoparasites. | No structures are compatible with hemoparasites. | |

| Blood chemistry | ||||

| Albumin | 1.31 | (g/dl) | ||

| ALT (SGPT) | 28.1 | (U/L) | ||

| ALP (FA) | 34.1 | (U/L) | ||

| Total bilirubin | 0.35 | (mg/dl) | ||

| Direct bilirubin | 0.11 | (mg/dl) | ||

| Indirect bilirubin | 0.24 | (mg/dl) | ||

| BUN | 13.3 | (mg/dl) | ||

| Creatinine | 0.7 | (mg/dl) | ||

| Faeces examination | ||||

| Flotation method | ||||

| Colour: | Green, white spots | Mucous: | Positive | |

| Odor: | Sui generis | Hidden blood: | Negative | |

| Consistency: | Liquid | Foreign elements: | None | |

| Microscopic analysis of faeces | ||||

| Vegetal Fibers | + | |||

| Muscle Fibers | Negative | |||

| Bacterial Microbiota | Normal | |||

| Leukocytes | 0 -1 x field | |||

| Hematies | 0 -2 x field | |||

| Free Fat | Negative | |||

| Crystals | Not present | |||

| Starches | Not present | |||

| Spirils | Not present | |||

| Yeasts | Not present | |||

| Fungus Mycelia | Not present | |||

| Seeds | 0 - 1 x field | |||

| Hair | Not present | |||

| Epithelial Cells | 0 - 2 x field | |||

Parasitology: No structures compatible with gastrointestinal parasites were observed in the sample examined.

Bold indicates altered results.

Reference values based on [6].

The nematode specimens featured a slightly ventrally curved posterior end with copulatory organs and spicules that were notably unequal and structurally dissimilar, suggesting the worms belong to the genus Thelazia (Fig. 1). Microscope images sent to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) in Atlanta, Georgia, USA, were described as Thelazia sp. The molecular, genomic and phylogenetic analyses indicated that the helminth corresponded to Thelazia lacrymalis. The phylogenetic analysis reveals evolutionary relationships of the generated consensus sequence with the 18S rRNA of other members of the family Thelaziidae (Fig. 1). The Thelazia sequence reported here is grouped into a monophyletic cluster with the reference sequence of Thelazia lacrymalis (GenBank: DQ503458.1), with a bootstrap value of 100. Although it forms a monophyletic group with other Thelazia spp. (Bootstrap <75), such as Thelazia callipaeda, our sequence is well-distinguished from other genera, such as Spirocerca and Oxyspirura (Fig. 1) (https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4798430). That supports the hypothesis that the helminth identified corresponds to Thelazia lacrymalis. We performed additional PCRs using the ITS1 and the COX1 markers. Both confirmed the species T. lacrymalis.

Further ophthalmological examinations revealed normal palpebral reflexes, threat reflex, positive pupillary reflex, normal dazzle reflex, and movement of the nictitating membrane in an average centrotemporal direction (Fig. 1). The cornea was bright. The fluorescein, Schirmer, and Jones tests were normal. A 3-month follow-up of the amputated limb showed good recovery (Fig. 1).

Thelazia spp. primarily infects animals and occasionally humans. It is a neglected parasite in Colombia and Latin America. After comprehensive database searches, no studies or cases of thelaziosis from this country were found.

In Europe, ocular thelaziosis has been recently considered an emerging human parasitosis [5]. It is growingly reported and concerning in other regions, such as Asia [2]. In humans, ophthalmologists should consider thelaziosis as a differential diagnosis of ocular infections, especially in the tropics. From therapeutic and epidemiologic standpoints, it is essential to differentiate between infectious and allergic conjunctivitis [5].

There is a lack of reports of Thelazia in birds. The molecular and phylogenetic analyses allowed us to confirm an ocular infection due to T. lacrymalis, which was not reported in harpy eagle (H. harpyja), not in other Accipitriformes, nor before in other publications in Colombia or other countries in Latin America [3]. Although incidental, this finding is relevant, providing the baseline for studies in the Amazonian area of Colombia for searching T. lacrymalis and other species of this genus, as well as their vectors and the infection occurrence in birds, mammals and humans. Appropriate diagnosis can help to prevent complications such as corneal ulceration [5].

Thelazia lacrymalis has been usually associated with infections in equids, domestic and wild ruminants, and apparently transmitted by Musca autumnalis (experimentally) and Musca osiris. There is a lack of molecular studies on this pathogen [3].

In our eagle, as in other cases, ivermectin seems to be helpful as a systemic antiparasitic drug [5]. It has been used in thelaziosis in dogs, humans, cattle, and birds. In an Andean cock-of-the-rock (Rupicola peruvianus) from Peru, 0.2 mg/kg was used to solve the infection after ten weeks. In our case, the same dose was used for one week, with satisfactory results. Although no effective therapy for Thelazia in birds has been established, studies are required.

Additionally, comprehensive studies are warranted to elucidate the transmission, cycle, and phylogenetic relationship of Thelazia spp. and to understand their vectors and hosts, including birds and humans [1].

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Jorge Luis Bonilla-Aldana: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Data curation, Conceptualization. Norma Constanza Ganem-Galindo: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Gloria Elena Estrada-Cely: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Martha Leonor Losada-Cordoba: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Conceptualization. Santiago Sarmiento-Gantiva: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Investigation. Marina Muñoz: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Investigation. Angie L. Ramírez: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Investigation. Luz H. Patiño: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Investigation. Juan David Ramírez: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Investigation. Alberto E. Paniz-Mondolfi: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Conceptualization. Alfonso J. Rodriguez-Morales: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Conceptualization. D. Katterine Bonilla-Aldana: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Project administration, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Ethical statement

We confirm that the manuscript has been read and approved by all named authors and that no other persons have satisfied the criteria for authorship but are not listed. We further confirm that all have approved the order of authors listed in the manuscript. The material is original and is not under consideration for publication elsewhere.

The animal procedures performed were approved by the Universidad de la Amazonia, where the animal was treated. Furthermore, we confirmed that no generative artificial intelligence (AI) or AI-assisted technologies were used in the writing process.

Data availability

Data is available upon reasonable request.

Funding

None.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

To Sarah G. H. Sapp, PhD, from the DPDx Morphology Section, Diagnostics & Biology Team, Division of Parasitic Diseases and Malaria of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta, GA, USA, for her initial support on the preliminary morphological identification of the nematodes. We thank the support of the Faculty of Medicine of the Institución Universitaria Autónoma de las Américas - Sede Pereira, Pereira, Risaralda, Colombia, for the laboratory facilities used for microscopic examinations and photographs of the identified parasite. Also, to the Universidad del Rosario, Bogotá, DC, Colombia, for its support in molecular diagnosis, genome sequencing, and phylogenetics. Some of the authors would also like to dedicate this publication to the memory of Dr. Marlin Pulido, MD, a surgeon from Venezuela, who passed away in September 2024 after struggling with acute myeloid leukaemia, R.I.P.

Handling Editor: Patricia Schlagenhauf

References

- 1.do Vale B., Lopes A.P., da Conceição Fontes M., Silvestre M., Cardoso L., Coelho A.C. Thelaziosis due to Thelazia callipaeda in Europe in the 21st century-A review. Vet Parasitol. 2019;275 doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2019.108957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trenkić M., Tasić-Otašević S., Bezerra-Santos M.A., Stalević M., Petrović A., Otranto D. Prevention of Thelazia callipaeda reinfection among humans. Emerg Infect Dis. 2023;29:843–845. doi: 10.3201/eid2904.221610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fagundes-Moreira R., Bezerra-Santos M.A., Lia R.P., Daudt C., Wagatsuma J.T., de Carmo E.C.O., et al. Eyeworms of wild birds and new record of Thelazia (Thelaziella) aquilina (Nematoda: spirurida) Int J Parasitol: Parasites and Wildlife. 2024;23 doi: 10.1016/j.ijppaw.2024.100910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sobotyk C., Foster T., Callahan R.T., McLean N.J., Verocai G.G. Zoonotic Thelazia californiensis in dogs from New Mexico, USA, and a review of North American cases in animals and humans. Vet Parasitol: Regional Studies and Reports. 2021;24 doi: 10.1016/j.vprsr.2021.100553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pendones Ulerio J., Redero Cascón M., Parra Morales A.M., Muñoz Bellido J.L., Ávila Alonso A. Ocular thelaziosis: an emerging human parasitosis in Europe. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2023;42:793–796. doi: 10.1007/s10096-023-04598-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oliveira M.J., Nascimento I.A., Ribeiro V.O., Cortes L.A., Fernandes R.D., Santos L.C., et al. Haematological values for captive harpy eagle (Harpia harpyja) Pesqui Vet Bras. 2014;34 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available upon reasonable request.