Summary

Background

Nearly all transmitted/founder (T/F) HIV-1 are CCR5 (R5)-tropic. While previous evidence suggested that CXCR4 (X4)-tropic HIV-1 are transmissible, virus detection and characterization were not at the earliest stages of acute infection.

Methods

We identified an X4-tropic T/F HIV-1 in a participant (40700) in the RV217 acute infection cohort. Coreceptor usage was determined in TZM-bl cell line, NP-2 cell lines, and primary CD4+ T cells using pseudovirus and infectious molecular clones. CD4 subset dynamics were analyzed using flow cytometry. Viral load in each CD4 subset was quantified using cell-associated HIV RNA assay and total and integrated HIV DNA assay.

Findings

Participant 40700 was infected by an X4 tropic HIV-1 without CCR5 using ability. This participant experienced significantly faster CD4 depletion compared to R5 virus infected individuals in the same cohort. Naïve and central memory (CM) CD4 subsets declined faster than effector memory (EM) and transitional memory (TM) subsets. All CD4 subsets, including the naïve, were productively infected. Increased CD4+ T cell activation was observed over time. This X4-tropic T/F virus is resistant to broadly neutralizing antibodies (bNAbs) targeting V1/V2 and V3 regions, while most of the R5 T/F viruses in the same cohort are sensitive to the same panel of bNAbs.

Interpretation

X4-tropic HIV-1 is transmissible through mucosal route in people with wild-type CCR5 genotype. The CD4 subset tropism of HIV-1 may be an important determinant for HIV-1 transmissibility and virulence.

Funding

Institute of Human Virology, National Institutes of Health, Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine.

Keywords: HIV-1, CXCR4, Mucosal transmission, CD4 subset, Pathogenesis

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

The vast majority of transmitted/founder (T/F) HIV-1 identified to date use CCR5 exclusively. The biological mechanisms responsible for the transmission advantage of CCR5 tropic HIV-1 are not well understood. We searched PubMed, without language restrictions, from database inception to May 26, 2024, using the terms “HIV-1”, “CXCR4”, and “transmission”. The search yielded 409 publications. While previous evidence suggest that HIV-1 could use CXCR4 to establish clinical infection, to the best of our knowledge, a T/F HIV-1 which strictly uses CXCR4 has not been identified in individuals with wild-type CCR5 genotype who acquired the virus through mucosal transmission.

Added value of this study

We identified and comprehensively characterized an X4 tropic T/F HIV-1 in the RV217 acute infection cohort, which was transmitted through mucosal route in an individual with the wild-type CCR5 genotype. We demonstrated that this T/F virus uses CXCR4 exclusively in primary CD4+ T cells. This X4 tropic T/F virus led to a 5.9-fold faster CD4 decline than infections established by R5 viruses in the same cohort. The rapid CD4 depletion in this participant was mainly due to the loss of the naïve and central memory (CM) CD4 subsets. In contrast, the naïve and CM CD4 subsets were relatively well preserved in participants infected by R5 viruses during the first two years of infection. In contrast to the R5 viruses which have replication advantage in the EM and TM CD4 subsets, this X4 T/F virus preferentially infects the CM CD4 subset during early infection. bNAbs targeting the V1/V2 and V3 loops could not neutralize this highly virulent T/F strain.

Implications of all the available evidence

The findings of the current study, together with previously available evidence, demonstrate that X4 tropic HIV-1 is transmissible through the mucosal route in people with wild-type CCR5 genotype and can cause rapid CD4 depletion. The poor infectivity of the X4 virus in the EM and TM CD4 subsets, which are abundant in the mucosal tissues, could compromise the transmissibility of X4 tropic HIV-1. The increased infectivity of the X4 virus in the naïve and CM CD4 subsets, which are essential for maintaining CD4 homeostasis, could be an important reason for the enhanced pathogenicity of X4 tropic HIV-1. Further studies are needed to better understand the CD4 subset preference in determining HIV-1 transmissibility and virulence, which may provide valuable insights into HIV-1 prevention and functional cure.

Introduction

The vast majority of T/F HIV-1 are CCR5 tropic.1,2 While the biological mechanisms underlying the transmission advantage of R5 tropic HIV-1 remain poorly understood, previous evidence suggested that X4 tropic HIV-1 is transmissible. The best evidence comes from the identification of X4 viruses in people homozygous for the CCR5 delta 32 allele.3, 4, 5, 6, 7 These studies suggested that clinical HIV-1 infection could be established and maintained by the CXCR4 coreceptor. Moreover, the identification of X4 viruses in recently diagnosed HIV-1 infections also indicated that X4 viruses are transmissible, although the chance of transmission was low, and the route of HIV-1 transmission was not always clear for those individuals.8, 9, 10 However, one caveat of the previous studies is that viral identification was not at the earliest stage of acute HIV infection. Therefore, it was not possible to characterize the exact phenotype of the transmitted virus. Because HIV-1 could also use alternative coreceptors other than CCR5 and CXCR4, as assessed by in vitro assays, to establish clinical infection,5,11 the possibility that viral transmission in people homozygous for CCR5 delta 32 was mediated by alternative coreceptors could not be completely excluded. To our knowledge, an X4-tropic T/F HIV-1 which is transmitted through the mucosal route has not been confirmed so far in people with wild-type CCR5 genotype.

In the current study, we identified a participant (40700) who was infected by a pure X4 tropic T/F virus in the RV217 Thailand cohort, a longitudinal study of individuals at high risk of HIV-1 infection who were followed up, while still uninfected, by twice weekly HIV-1 RNA testing.12 The risk factor of HIV-1 transmission for participant 40700 was sexual contact. Participant 40700 had a wild-type CCR5 genotype and expressed normal levels of CCR5 on the CD4+ T cells. An unusually fast CD4 depletion was observed in participant 40700 upon HIV-1 transmission. We comprehensively characterized the genetic and phenotypic property related to the immunopathogenesis of this highly pathogenic, X4 tropic T/F strain.

Methods

Study participants

All study participants were from the RV217 Thailand acute infection cohort as previously reported.12 In brief, this study followed at risk participants twice weekly to identify HIV RNA within a few days of the last negative test, thus allowing observation of HIV evolution and host immune response from the earliest days of infection. Gender was self-reported by the study participants. Participant 40700 became infected around the time of entry and the risk factor for HIV-1 transmission was sexual contact. The subtype of the 40700 T/F virus is CRF01_AE. Participant 40700 initiated ART on day 266 (from the 1st positive test for HIV-1 RNA) and stopped ART on day 282 due to toxicity. ART was restarted on day 388.

Ethics statement

The study was approved by the local ethics review boards, the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, and the institutional review boards of the University of Maryland School of Medicine (number: HP-00089353). Written consent was provided by all participants.

Single genome amplification

Single genome amplification (SGA) was carried out as previously described.13 HIV-1 RNA in plasma was extracted using the QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit (Qiagen). To amplify the 3′ half viral genome, cDNA was synthesized by the SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) using the primer 1.R3.B3R 5′- ACTACTTGAAGCACTCAAGGCAAGCTTTATTG-3’ (nt 9642-9611 in HXB2). The first round PCR was performed using the primers 07For7 5′-CAAATTAYAAAAATTCAAAATTTTCGGGTTTATTACAG-3’ (nt 4875–4912) and 2.R3.B6R 5′-TGAAGCACTCAAGGCAAGCTTTATTGAGGC-3’ (nt 9636–9607), and the second round PCR was performed with the primers VIF1 5′-GGGTTTATTACAGGGACAGCAGAG-3’ (nt 4900–4923) and Low2c 5′-TGAGGCTTAAGCAGTGGGTTCC-3’ (nt 9591–9612). To amplify the 5′ half viral genome, cDNA was synthesized using the primer 07Rev8 5′- CCTARTGGGATGTGTACTTCTGAACTT-3’ (nt 5193–5219). The first round PCR was performed using the primers 1.U5.B1F 5′- CCTTGAGTGCTTCAAGTAGTGTGTGCCCGTCTGT-3’ (nt 538–571) and 07Rev8 5′- CCTARTGGGATGTGTACTTCTGAACTT-3’ (nt 5193–5219), and the second round PCR was performed using the primers Upper1A 5′-AGTGGCGCCCGAACAGG-3’ (nt 634–650) and Rev11 5′- ATCATCACCTGCCATCTGTTTTCCAT-3’ (nt 5041–5066). Two microliters of the first round PCR products were used for the second round PCR amplification. The PCR conditions were as follows: one cycle at 94 °C for 2 min; 35 cycles of a denaturing step at 94 °C for 15 s, an annealing step at 60 °C for 30 s, an extension step at 68 °C for 4 min; and one cycle of an additional extension at 68 °C for 10 min. The PCR amplicons were directly sequenced by the cycle sequencing and dye terminator methods. Individual sequences were assembled and edited using Sequencher (Gene Codes).

Genetic analysis

HIV-1 sequences were aligned by the Gene Cutter tool in the Los Alamos HIV Sequence Database (https://www.hiv.lanl.gov/content/sequence/GENE_CUTTER/cutter.html), followed by manual adjustment to obtain the optimal alignment. Sequences of the env variable loops were extracted using the Gene Cutter tool. N-linked glycosylation sites were analyzed by the N-GlycoSite tool in the Los Alamos HIV Sequence Database.14 Sequence alignment was visualized using the Geneious software (https://www.geneious.com). Phylogenetic tree was constructed by MEGA6 using the maximum likelihood method.15

Pseudovirus preparation and titration

Pseudovirus stocks were prepared as previously described.16 In brief, 2 μg of env clone was co-transfected with 4 μg of the pNL4.3-ΔEnv-vpr + -luc + into 293T cells (ATCC CRL3216) in a T25 flask using the FuGENE6 transfection reagent (Promega). The cells were cultured at 37 °C for 6 h before the medium was completely replaced with fresh medium. The culture supernatants containing the pseudoviruses were harvested at 72 h post transfection, aliquoted and stored at −80 °C until use. The infectious titers (TCID50) of the pseudovirus stocks were determined on TZM-bl cells. The TZM-bl cell line was obtained from the HIV Reagent Program (ARP-8129) and was not validated further.

Generation of infectious molecular clone (IMC) of the 40700 T/F virus

Infections molecular clone was constructed based on previously described approach.17 To obtain the full-length sequence of the 40700 T/F virus, three overlapping fragments were amplified using plasma or PBMC samples collected at day 20 (from the 1st positive test for HIV-1 RNA). The 5′ half and 3′ half viral genomes were amplified by SGA using day 20 plasma sample as described above. The 5′ LTR-gag fragment was amplified using viral DNA extracted from the day 20 PBMCs with the forward primer 5′- TGGAAGGGCTAATTTACTCCAAGAAAAG-3’ (nt 1–28) and the reverse primer 5′- TCTGATAATGCTGWRAACATGGGTAT-3’ (nt 1294–1319). The full-length 40700 T/F virus was inferred as the consensus sequence of the three overlapping fragments. The consensus sequence generated from day 20 was identical to the consequence sequence generated from day 15. The 40700 T/F sequence was chemically synthesized and cloned into the vector pUC57-Brick (Genescript).

To generate the viral stock of the 40700 T/F IMC, 6 μg of IMC was transfected into 293T cells in a T25 flask using the FuGENE6 transfection reagent (Promega). The cells were cultured at 37 °C for 6 h before the medium was replaced by fresh medium. The culture supernatants were harvested at 72 h post transfection, aliquoted and stored at −80 °C until use. The infectious titer (TCID50) of the viral stock was determined in TZM-bl cells.

Determination of coreceptor usage

Coreceptor usage of the 40700 T/F pseudovirus was determined by both coreceptor inhibition assay in the TZM-bl cell line and entry assay in NP-2 cell lines. For inhibition assay, TZM-bl cells were seeded in a 96-well plate at a density of 1 × 105 cells per well. The next day, the cells were pre-treated with different concentrations of the CCR5 inhibitor Maraviroc or the CXCR4 inhibitor AMD3100 at 37 °C for 1 h. The treated cells were infected with approximately 500 TICD50 of the pseudovirus. The infected cells were lysed at day 3 after infection. The infectivity in each well was determined by measuring the relative luciferase units (RLU) in the cell lysates using the Britelite plus system (PerkinElmer). The percentage of inhibition was determined by comparing the infectivity with positive control wells without drug inhibition.

For entry assay, NP-2 cell lines expressing CCR5 or CXCR4 were seeded in a 96-well plate at a density of 1 × 105 cells per well. The next day, the cells were infected with approximately 200 TCID50 of each pseudovirus (MOI = 0.002). After 6 h of incubation at 37 °C, the infected cells were washed twice with the culture medium and cultured at 37 °C for three days. At 72 h post infection, the infected cells were lysed, and the infectivity was determined by measuring the relative luciferase units (RLU) in the cell lysates using the Britelite plus system (PerkinElmer). Viral infectivity was considered positive if the RLU value was at least 5-fold higher than the background RLU value in the NP-2 parental cell line. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Coreceptor usage of the 40700 IMC was determined in NP-2 cell lines expressing CCR5, CXCR4 and a panel of alternative coreceptors (CCR3, APJ, FPRL1, CCR8, GPR15, CCR2b and CCR1). NP-2 cells were seeded in 96-well plates one day before infection at a density of 1 × 105 cells per well. Approximately 100 TCID50 of viral stock was used for infection (MOI = 0.001). After 4 h of incubation at 37 °C, the infected cells were washed three times with the culture medium and cultured at 37 °C for five days. The p24 concentrations in the culture supernatants were measured on day 5 post infection (PerkinElmer). The NP-2 cell lines were kindly provided by Dr. Hiroo Hoshino and were not validated further.

Determination of viral replication capacity in primary CD4+ T cells

Purified CD4+ T cells from healthy donors were stimulated with 1 μg/mL soluble anti-CD3 (clone OKT3, eBioscience) and 1 μg/mL soluble anti-CD28 (clone CD28.2, eBioscience) in the presence of 50 IU/mL IL-2 (PeproTech) for three days. The stimulated CD4+ T cells were infected by the 40700 T/F IMC at 37 °C for 4 h (MOI = 0.001). The cells were washed three times after infection and were cultured at 37 °C for 7 days. The culture supernatants were collected every day and viral replication kinetics was determined by measuring the p24 concentration in the supernatant (PerkinElmer).

To determine the sensitivity of the 40700 T/F IMC to Maraviroc and AMD3100 inhibition in primary CD4+ T cells, purified CD4+ T cells from three healthy donors were stimulated as described above. The stimulated cells were pre-treated with 10 μM Maraviroc or 10 μM AMD3100 at 37 °C for 1 h before infected by the 40700 T/F IMC at 37 °C for 4 h (MOI = 0.001). Cells without pre-treatment were infected as control. Virus replication was monitored by measuring the p24 concentration (PerkinElmer) at day 5 after infection.

CCR5 genotyping

Genomic DNA (gDNA) was extracted from 1 × 106 PBMCs using the QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen) per manufacturers' instructions. To differentiate between CCR5wt/wt, Δ32/Δ32, and wt/Δ32 genotypes, two primer amplification strategies were employed for each sample. Forward primers CCR5delF1 (5′-ACCGTCAGTATCAATTCTGGAAGA-3′) and CCR5span1a (5′-CATTTTCCATACATTAAAGATAGT-3′) were used to specifically detect the CCR5wt and CCR5Δ32 genotypes, respectively; the reverse primer CCR5del2 (5′-CATGATGGTGAAGATAAGCCTCACA-3′) was common for both (all Sigma–Aldrich; St. Louis, MO). Two PCR master mixes differing only in the forward primer were prepared at a final volume of 10 μL, including 5 μL Platinum SYBR Green qPCR Supermix-UDG with ROX (Invitrogen), 0.1 μM CCR5del2, and 0.1 μM CCR5span1a or CCR5delF1 primers and 10 ng of gDNA sample. PCR was performed in 384 well plates sealed with optical adhesive film (ABI), and amplification performed on Veriti thermal cyclers (ABI) using the following parameters: 50 °C, 2 min; 95 °C, 2 min; 40 cycles of 95 °C, 15 s and 61 °C, 30 s; 4 °C. Dissociation curve analyses were then performed on the 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR instrument using the SDS2.4 software to detect presence or absence of amplified products (both ABI).

CD4 subset analysis and sorting

CD4 subset analysis and sorting were performed as described previously.18 PBMC samples were stained by the following antibodies: CD3-Brilliant Violet 605 (clone OKT3, BioLegend), CD4-PerCP-Cy5.5 (clone OKT4, Biolegend), CCR7-PE-CF594 (clone 2-L1-A, BD Biosciences), CD27-PE (clone M-T271, BioLegend), CD45RO-APC (clone UCHL1, BioLegend). The cells were then stained by the Live-dead aqua (Invitrogen) prior to flow analysis. The stained cells were sorted on a BD FACSAria II cell sorter (BD Biosciences). Four CD4 subsets were defined as follows: naïve (CD45RO−, CCR7+, and CD27+), central memory (CD45RO+, CCR7+, and CD27+), transitional memory (CD45RO+, CCR7-, and CD27+) and effector memory (CD45RO+, CCR7-, and CD27-). The purity of each sorted CD4 subset was higher than 95%.

Flow cytometry

To determine CCR5 and CXCR4 expression on each CD4 subset, PBMCs were stained with the following antibodies: CD3-Brilliant Violet 605 (clone OKT3, BioLegend), CD4-PerCP-Cy5.5 (clone OKT4, BioLegend), CCR7-PE-CF594 (clone 2-L1-A, BD Biosciences), CD27-FITC (clone M-T271, BioLegend), CD45RO-APC (clone UCHL1, BioLegend), CCR5-PE (clone J418F1, BioLegend) or CXCR4-PE (clone Q18A64, BioLegend). The CCR5 and CXCR4 antibodies were titrated to determine the optimal concentration. To determine the non-specific staining, cells was cold-inhibited by a 100-fold excess of the unlabeled CCR5 or CXCR4 antibody (the same clone as the staining antibody) mixed with the respective labeled antibody. A fluorescence minus one (FMO) staining was also determined for CCR5/CXCR4 staining. The highest concentration of the labeled antibody with which the cold inhibition showed virtually overlapping staining with the FMO was used to determine the levels of CCR5 and CXCR4 expression on each CD4 subset.

To quantify the expression of cell activation and proliferation markers, PBMCs were stained with the following antibodies: CD3-Brilliant Violet 605 (clone OKT3, BioLegend), CD4- Alexa Fluor 700 (clone OKT4, BioLegend), CCR7-BV421 (clone G043H7, BioLegend), CD27-PerCP-Cy5.5 (clone M-T271, BioLegend), CD45RO-APC/Fire 750 (clone UCHL1, BioLegend), Ki-67-APC (clone Ki-67, BioLegend), HLA-DR-PerCP (clone L243, BioLegend), CD38-PE-594 (clone HIT2, BioLegend), and PD1-PE (clone EH12.2H7, BioLegend). The flow data were collected using the DIVA 7.0 software on the FACSAria II (BD Biosciences) cell sorter/analyzer and analyzed by the FlowJo software (FlowJo LLC, Ashland, OR).

Quantification of total and integrated HIV-1 DNA

Total and integrated HIV-1 DNA were quantified as previously described.19 The exact number of cells in each PCR reaction was determined by amplifying the human CD3 gene using the primers HCD3OUT5 5′-ACTGACATGGAACAGGGGAAG-3′ and HCD3OUT3 5′-CCAGCTCTGAAGTAGGGAACATAT-3'. To quantify the total HIV-1 DNA, the first round PCR was performed using the primers ULF1 5′-ATGCCACGTAAGCGAAACTCTGGGTCTCTCTDGTTAGAC-3' (nt 436–471, 9521–9556), UR1 5′-CCATCTCTCTCCTTCTAGC-3' (nt 775–793), HCD3OUT5 and HCD3OUT3. To quantify integrated HIV-1 DNA, the first round PCR was performed using the primers ULF1, Alu1 5′-TCCCAGCTACTGGGGAGGCTGAGG-3' (nt 8674–8697), Alu2 5′-GCCTCCCAAAGTGCTGGGATTACAG-3' (nt 6237–6261), HCD3OUT5 and HCD3OUT3. The first-round PCR conditions were as follows: a denaturation step at 95 °C for 8 min; 12 cycles of a denaturing step at 95 °C for 1 min, an annealing step at 55 °C for 40 s (1 min for integrated DNA), an extension step at 72 °C for 1 min (10 min for integrated DNA), followed by an elongation step at 72 °C for 15 min. For all experiments, the first round PCR products were diluted 10-fold and a total of 6.4 μL of the diluted PCR products were used for real-time PCR on the QuantStudio 3 Real-Time PCR Systems (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using the Perfecta qPCR ToughMix (QuantaBio). The copy number of the total and integrated HIV-1 DNA were quantified using the primers Lambda T 5′-ATGCCACGTAAGCGAAACT-3' (nt 1555–1572), UR2 5′- CTGAGGGATCTCTAGTTACC-3' (nt 583–602, 9668–9687), and the probe UHIV TaqMan 5'-/56-FAM/CACTCAAGG/ZEN/CAAGCTTTATTGAGGC/3IABkFQ/-3' (nt 522–546, 9607–9631). The copy numbers of human CD3 gene were determined using the primers HCD3IN5′ 5′-GGCTATCATTCTTCTTCAAGGT-3′, HCD3IN3′ 5′-CCTCTCTTCAGCCATTTAAGTA-3′, and the probe CD3 TaqMan 5'-/56-FAM/AGCAGAGAA/ZEN/CAGTTAAGAGCCTCCAT/3IABkFQ/-3'. The real-time PCR conditions were as follows: A denaturing step at 95 °C for 4 min, 40 cycles of a denaturing step at 95 °C for 3 s, an annealing and extension step at 60 °C for 20 s. The ACH2 cell lysates were used for standard curve.

Quantification of cell associated HIV-1 RNA

To quantify cell-associated HIV-1 RNA, RNA was extracted from sorted CD4+ T cells using the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen). A total of 8.5 μL extracted RNA was subjected to one-step RT-PCR using the Superscript III one-step RT-PCR system (Invitrogen). To amplify the pol region, the one-step RT-PCR was performed using the forward primer Pol F1 5′-TACAGTGCAGGGGAAAGAATA-3’ (nt 4809–4829) and the reverse primer Pol R1 5′-CTTCTTGGCACTACTTTTATGTCAC-3’ (nt 4993–5017). The PCR conditions were as follow: a reverse transcription step at 50 °C for 1h; A denaturing step at 94 °C for 2 min; 16 cycles of a denaturing step at 94 °C for 15 s, an annealing step at 55 °C for 30 s, an extension step at 68 °C for 1 min, and one cycle of an additional extension at 68 °C for 5 min. The first round PCR products were diluted 10-fold and a total of 6.4 μL of diluted PCR products were used for the real-time PCR using the forward primer Pol F1, the reverse primer Pol R2 5′-CTGCCCCTTCACCTTTCC-3’ (nt 4957–4974), and the probe Pol Famzen: 5’-/56-FAM/TTTCGGGTT/ZEN/TATTACAGGGACAGCAG/3IABkFQ/-3’ (nt 4896–4921). The real-time PCR was performed on the QuantStudio 3 Real-Time PCR Systems (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using the following conditions: A denaturing step at 94 °C for 4 min, 45 cycles of a denaturing step at 94 °C for 3 s, an annealing and extension step at 60 °C for 20 s. To amplify the tat/rev transcript, the one-step RT-PCR was performed using the forward primer Tat1.4 AE 5′- TGGCAG GAAGAAGCGGAAG (nt 5971–5989) and the reverse primer Rev AE-ter 5′- TGTCTCTGYCTTGCTCKCCACC-3’ (nt 8433–8454). The real-time PCR was performed using the forward primer Tat2 AE-bis 5′-GTAAGGATCATCAAAATCCTVTACCARAGCA-3’ (nt 6015–6045), the reverse primer Rev AE-ter 5′- TGTCTCTGYCTTGCTCKCCACC-3’ (nt 8433–8454), and the probe Tat-Rev AE 5’-/56-FAM/TT CYT TCG G/ZEN/G CCT GTC GGG TTC C/3IABkFQ/-3’ (nt 8399–8421). The PCR conditions were the same as for amplifying the pol region. The copy number of the input RNA was determined by using the RNA standard generated by in vitro transcription. In brief, the amplicon region (the CRF01_AE consensus sequence was used in the current study) was cloned into the pUC57 vector downstream of the T7 promoter. The DNA fragment containing the amplicon was PCR amplified and the RNA was generated by in vitro transcription using the MEGAscript T7 Transcription Kit (Invitrogen).

Neutralization assay

The neutralization activity of plasma samples and monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) was determined by using a luciferase reporter system in TZM-bl cells as previously described.20 Plasma samples were heat inactivated at 56 °C for 45 min. The inactivated plasma was diluted at a 1:3 serial dilution starting from 1:20. The mAbs were diluted at a 1:3 serial dilution from a starting concentration of 25 μg/mL. The virus stocks were diluted to a concentration that achieved approximately 150,000 RLU in the TZM-bl cells (or at least 10 times above the background RLU of the cells control). The serial diluted plasma samples or mAbs were then incubated with the viruses for 1 h at 37 °C in duplicate before the TZM-bl cells were added. The 50% inhibitory dose (ID50) was determined as the dilution at which the relative luminescence units (RLUs) were reduced by 50% in comparison to the RLUs in the virus control wells after subtraction of the background RLUs in cell control wells.

Statistics

The rate of CD4 decline was determined using a linear mixed effect model (LME) as we previously described.18,21 The LME model was hierarchical in the sense that it estimated a population specific slope and intercept with time, as well as subject-specific slopes and intercepts. According to the LME model estimates, the mean slope of the population was −0.25 and the standard deviation of the subject-specific slopes was 0.225. According to the Empirical Best Linear Unbiased Predictor (EBLUP) for 40700, the estimated slope for this participant was −1.577. Thus, using the LME model assumption of normality for the random effects, the Z-score associated for subject 40700 was −5.89. The P-value of observing a Z-score of −5.89 or smaller under normality was 1.84 x 10−9. Therefore, we concluded that participant 40700 had a significantly faster rate of CD4 decline.

Role of the funders

The founders had no roles in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Results

Identification and characterization of the X4 tropic T/F virus in participant 40700

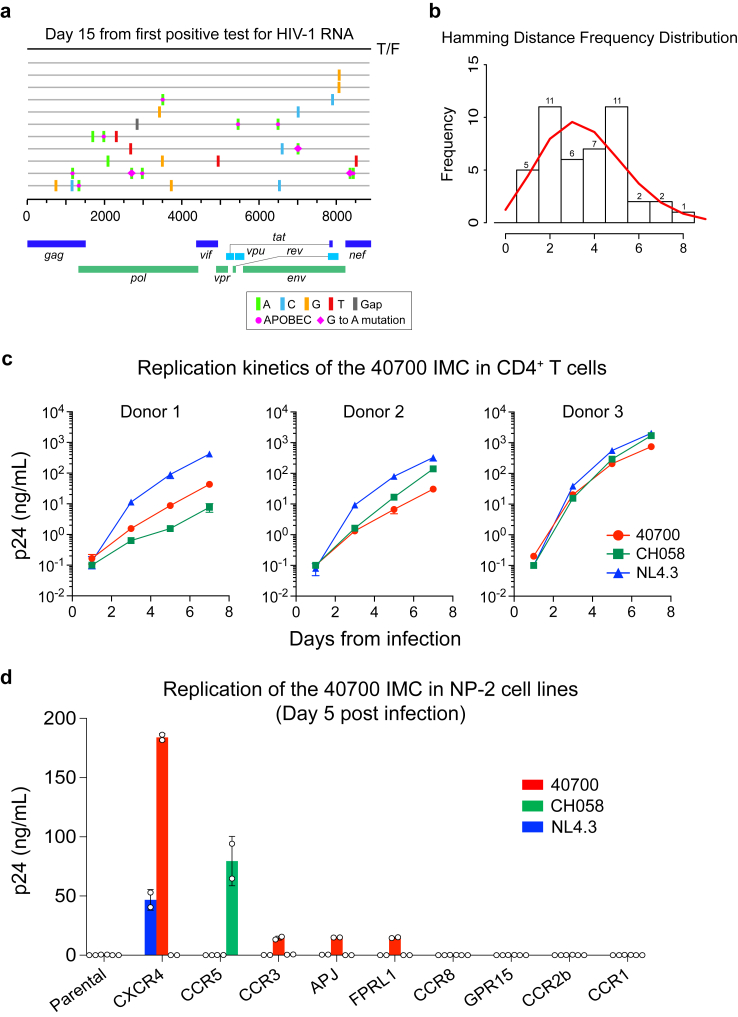

Participant 40700 was identified in the RV217 Thailand acute infection cohort and was infected by a CRF01_AE HIV-1. The first large volume blood draw was 15 days from the first HIV-1 RNA positive test and 23 days from the last HIV-1 RNA negative test. Analysis of near full-length viral genomes obtained by single genome amplification (SGA) identified a homogenous viral lineage at day 15 (Fig. 1a). Genetic analysis using the Poisson-Fitter tool22 showed that the frequency distribution of the Hamming Distance followed Poisson distribution and the sequences exhibited a star-like phylogeny (Fig. 1b). The estimated days from HIV-1 transmission (based on the Poisson-Fitter tool) was 26. These results demonstrated that participant 40700 was identified during acute HIV infection (AHI), which was established by a single T/F virus.

Fig. 1.

Genetic and phenotypic characterization of the 40700 T/F virus. (a) Highlighter plot showing near-full length viral genomes obtained at day 15 from the 1st positive test for HIV-1 RNA. The sequences were obtained by SGA. The consensus sequence (black line on the top) is used as the master sequence. Genetic substitutions compared to the consensus sequence are color coded. (b) Frequency distribution of the pair-wise Hamming Distance of the day 15 viral sequences. The frequency distribution follows Poisson distribution as determined by the Poisson-Fitter tool in the Los Alamos HIV Sequence Database. (c) Replication kinetics of the 40700 IMC in purified CD4+ T cells from three healthy donors. The X4 tropic strain NL4.3 and an R5 tropic T/F virus CH058 were used as controls. All infections were performed in triplicate. The error bar represents the standard deviation (SD). (d) Determination of coreceptor usage of the 40700 IMC in a panel of NP-2 cell lines expressing different HIV-1 coreceptors. The p24 concentration in the culture supernatant was determined on day 5 post infection. The X4 tropic strain NL4.3 and an R5 tropic T/F virus CH058 were used as controls. The infections were performed in duplicate. The error bar shows the SD.

While nearly all T/F HIV-1 identified so far are CCR5 tropic, coreceptor prediction using Geno2Pheno showed a high likelihood of CXCR4 usage by the 40700 T/F virus (FPR = 0.1%).23 All viral sequences obtained from day 15 were predicted to be CXCR4-using (nine sequences had FPR value of 0.1%, and one sequence had FPR value of 0.2%). This observation prompted us to phenotypically characterize the coreceptor usage of this T/F virus. Coreceptor inhibition assay in the TZM-bl cell line showed that the entry activity of the 40700 T/F pseudovirus can be completely blocked by the CXCR4 inhibitor AMD3100, while the CCR5 inhibitor Maraviroc showed no inhibition at the highest concentration (Supplementary Fig. S1a). Coreceptor assay in NP-2 cell lines demonstrated that the 40700 T/F pseudovirus can infect the NP-2 CXCR4 cell line with high efficiency, while no infectivity was observed in the NP-2 CCR5 cell line (Supplementary Fig. S1b). These data suggested that the 40700 T/F virus uses CXCR4 exclusively.

To better characterize the phenotype of the 40700 T/F virus, we constructed a full-length infectious molecular clone (IMC) (Supplementary Fig. S2). A viral replication assay in purified CD4+ T cells from three healthy donors showed that the 40700 T/F IMC was replication competent in primary CD4+ T cells (Fig. 1c). Overall, its replication kinetics was comparable to the X4 tropic strain NL4.3 and to an R5-tropic T/F virus CH058 (Fig. 1c). The replication of 40700 IMC in primary CD4+ T cells can be completely inhibited by the CXCR4 inhibitor AMD3100 (10 μM), while the same concentration of Maraviroc showed no impact on viral replication (we used 10 μM of Maraviroc because it can completely block the entry of CCR5 HIV-1 in TZM-bl cell line, as shown in Supplementary Fig. S1a, and can inhibit >99.9% of CCR5 virus entry in primary CD4+ T cells as demonstrated in our recent study24) (Supplementary Fig. S3). We then determined the replication of the 40700 IMC in a panel of NP-2 cell lines expressing CCR5, CXCR4, as well as another seven alternative coreceptors which can be used by HIV-1 (Fig. 1d). Consistent with the results of the pseudovirus, the 40700 IMC replicated in the NP-2 CXCR4 cell line with high efficiency, while no viral replication was detected in the NP-2 CCR5 cell line (Fig. 1d). The 40700 IMC could also infect the CCR3, APJ and FPRL1 cell lines with low efficiency (Fig. 1d). However, given its poor efficiency in using these alternative coreceptors, as well as the fact that the replication of the 40700 IMC in primary CD4+ T cells can be completely inhibited by the CXCR4 inhibitor AMD3100, we can exclude the possibility that the clinical infection in participant 40700 was established by these alternative coreceptors.

A CCR5 genotyping showed that participant 40700 did not have the CCR5 delta32 mutation (Methods). We then analyzed the CCR5 and CXCR4 expression on the CD4+ T cells from 40700 (isolated at day 20 from the first positive test for HIV-1 RNA) (Supplementary Fig. S4). The CCR5 and CXCR4 expression on the CD4+ T cells of 40700 showed a similar pattern as previously observed in two participants infected by R5 viruses in the RV217 Thailand cohort.18 The CCR5 expression was high on the effector memory (EM) and transitional memory (TM) CD4 subsets, low on the central memory (CM) subset, and was undetectable on the naïve subset. The CXCR4 expression showed a reciprocal pattern (Supplementary Fig. S4). Taken together, these data demonstrated that participant 40700 was infected by a CXCR4 tropic T/F virus lacking demonstrable CCR5 tropism in both CCR5-expressing cell lines and primary CD4+ T cells. The transmission of X4 virus in 40700 could not be explained by an unusual expression of the CCR5 and CXCR4 coreceptors in this participant.

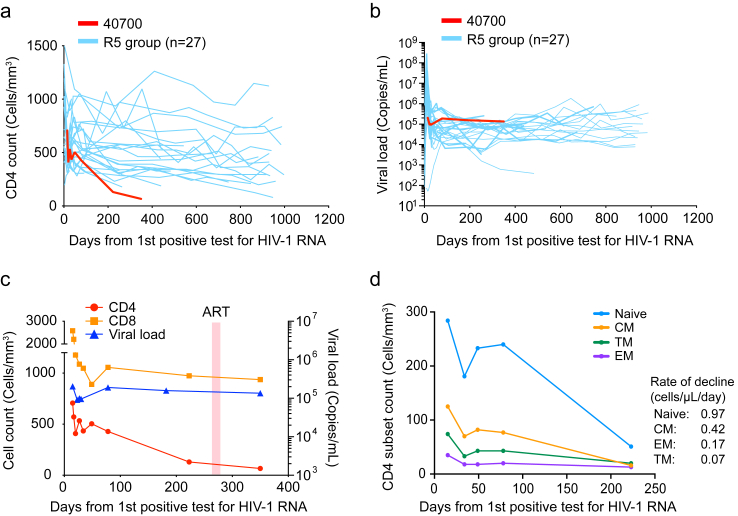

Rapid CD4+ T cell depletion in participant 40700

Participant 40700 experienced significantly faster CD4+ T cell decline compared to infections established by R5 virus in the RV217 Thailand cohort (Fig. 2a). The CD4 count dropped from 707 cells/μL to 130 cells/μL during the first 223 days of infection before ART initiation (Participant 40700 was on and off ART since day 266, as described in Methods). The rate of CD4 decline was 1.6 cells/μL/day in 40700, while the median rate of CD4 decline in the R5 group was 0.27 cells/μL/day (Fig. 2a). By analyzing the mean and variance of the participant specific CD4 slopes with a Linear Mixed Effect (LME) model, we were able to confirm that 40700 had a statistically significant rate of CD4+ T cell decline compared with the R5 group [P < 0.001; normal distribution test] (Fig. 2a). The plasma viral load (VL) in 40700 was sustained above 105 copies/mL (Fig. 2b–c). In comparison to the R5 group, participant 40700 had a relatively high VL set point (Fig. 2b). However, an interesting observation was that at the earliest stage of acute infection (around the time of peak viremia), the plasma VL in 40700 was relatively low in comparison to the R5 group (Fig. 2b). This interesting feature could be explained by the different CD4 subset targeting by 40700 and the R5 T/F virus (as discussed below). The CD8 T cell count in 40700 was relatively stabilized after AHI (Fig. 2c, Supplementary Fig. S5). Analysis of the dynamics of each CD4 subset showed that the naïve CD4 subset declined faster (0.97 cells/μL/day) than the memory subsets (Fig. 2d). Among the memory CD4 subsets, the central memory (CM) subset declined faster (0.42 cells/μL/day) than effector memory (EM) and transitional memory (TM) subsets (0.17 and 0.07 cells/μL/day, respectively) (Fig. 2d). These data suggested that the rapid CD4+ T cells depletion in 40700 was mainly due to the loss of the naïve and CM CD4+ T cells.

Fig. 2.

Rapid CD4+T cell depletion in participant 40700 after HIV-1 transmission. (a) Dynamics of CD4+ T cells in participant 40700 compared to R5 HIV-1 infected participants in the RV217 Thailand cohort. The rate of CD4 decline was calculated using a linear mixed effect model (LME). The statistical significance was determined using a normal distribution test. (b) Viral load dynamics in 40700 compared to RV217 Thailand participants infected by R5 T/F viruses. (c) Dynamics of CD4 count, CD8 count, and plasma VL in participant 40700. The time frame when participant 40700 was on ART is highlighted in red (day 266–282). (d) Dynamics of each CD4 subset in participant 40700 before ART initiation. Four different CD4 subsets (naïve, CM, EM, and TM) are color coded. The rate of CD4 subset decline was calculated by a linear regression model.

Our previous study on two RV217 participants infected by R5-tropic T/F virus, who underwent the coreceptor switch at around two years post infection, demonstrated that the naïve and CM CD4 subsets were maintained at relatively high levels before the coreceptor switch occurred.18 Due to PBMC sample availability, we were unable to determine the dynamic changes of each CD4 subset in the R5 group in the current study. To understand whether there is any difference in CD4 subset compositions between the R5 group and participant 40700, we analyzed the number of each CD4 subset, as well as their frequency in total CD4+ T cells, for 11 participants who were ART-naïve and strictly harbored R5 viruses at around two years after HIV infection.18 The median numbers of naïve, CM, TM, and EM subsets in the R5 group were 314 cells/μL, 115 cells/μL, 34 cells/μL, and 34 cells/μL, respectively, while on day 223 (the last time point before ART), the numbers of naïve, CM, TM, and EM subsets in 40700 were 50 cells/μL, 11 cells/μL, 37 cells/μL, and 19 cells/μL, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S6a). The median frequencies of naïve, CM, TM, and EM subsets in the R5 group were 64.9%, 26.8%, 5.3%, and 6.6%, respectively, while in 40700, the frequencies of naïve, CM, TM, and EM subsets were 38.5%, 8.5%, 28.6%, and 14.7%, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S6b). These data indicate that, in comparison to participant 40700, the naïve and CM CD4 subsets were relatively well preserved in participants infected by R5 viruses during the first two years of infection.

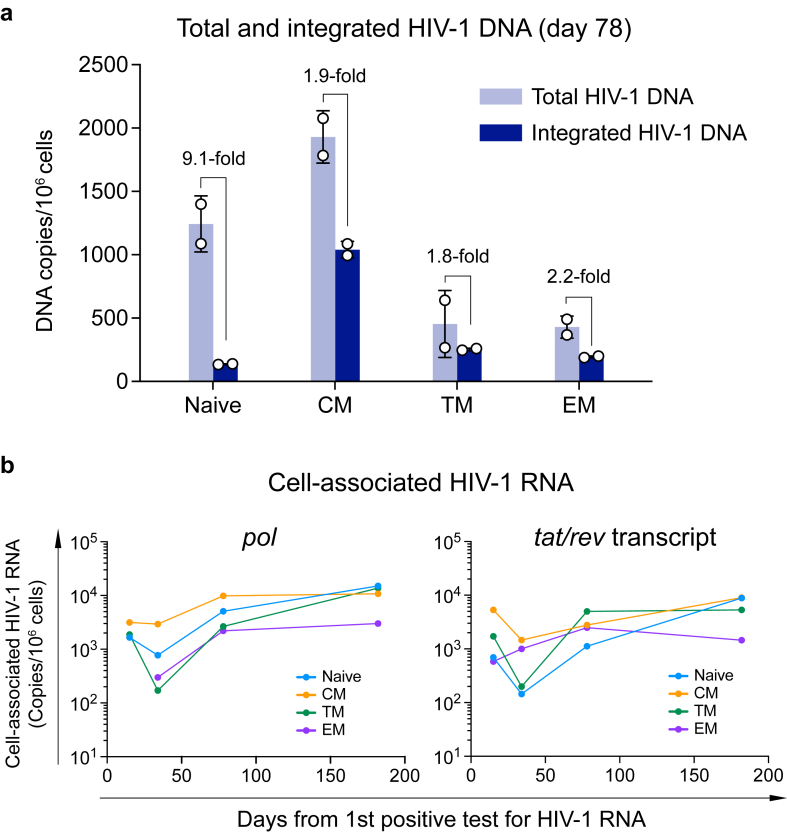

Broad CD4 subset targeting of the 40700 T/F virus

CXCR4 tropic HIV-1 are considered to have a broader CD4 subset targeting than R5 viruses.25 In macaques infected by X4-tropic SHIV, the resting naïve CD4+ T cells were productively infected and rapidly depleted.26 The strict X4 tropism of the 40700 T/F virus provides a unique opportunity to determine the CD4 subset targeting and pathogenesis of the X4 virus in natural HIV-1 infection. The faster depletion of the naïve and CM CD4 subsets in 40700 indicated that they could be preferentially infected. Quantification of total and integrated HIV-1 DNA at day 78 showed that both the total and integrated HIV-1 DNA were detectable in all CD4 subsets (Fig. 3a). The CM CD4 subset contained the highest level of both the total and integrated HIV-1 DNA (Fig. 3a). Possibly due to the relatively low level of CXCR4 expression, the EM and TM subsets contained lower amount of total HIV-1 DNA compared with the CM and naïve subsets (Fig. 3a). In the naïve subset, the level of total HIV-1 DNA was 9.1-fold higher than the integrated DNA, while in the memory subsets, the total HIV-1 DNA was approximately 2-fold higher than the integrated DNA (Fig. 3a). This observation indicated that there may be differences in efficiency of viral integration between the memory and naïve CD4+ T cells, likely due their different levels of cell activation.

Fig. 3.

Quantification of total and integrated HIV-1 DNA and cell-associated HIV-1 RNA in participant 40700. (a) Total (light blue) and integrated (dark blue) HIV-1 DNA was quantified in each sorted CD4 subset at day 78 (from the 1st positive test for HIV-1 RNA). The results are shown as DNA copies/106 cells. The experiments were performed in duplicate. The error bar shows the SD. (b) Dynamics of cell-associated HIV-1 RNA in each CD4 subset. The cell-associated HIV-1 RNA in each CD4 subset was quantified by amplifying the pol region and the tat/rev transcript. Different CD4 subsets are color coded. The pol region in the EM CD4 subset was not amplifiable at the first time point (day 20). The cell-associated HIV-1 RNA viral load is shown as copies/106 cells.

To determine which CD4 subsets were productively infected in 40700, we quantified the cell-associated HIV-1 RNA in longitudinal samples by amplifying both the pol region and the tat/rev transcript (Fig. 3b). Because the tat/rev transcript was generated at relatively late stage of virus life cycle, it could more accurately reflect the productive infection status. The results showed that all CD4 subsets were productively infected in 40700 (Fig. 3b). In contrast, in RV217 Thailand participants who only harbored R5 tropic viruses as we confirmed in a recent study,18 cell-associated HIV-1 RNA was undetectable in the naïve CD4+ T cells at around two years of HIV-1 infection (Supplementary Fig. S7) (Due to sample availability, we were unable to quantify the total and integrated HIV-1 DNA for the R5 group). Quantification of the pol region and the tat/rev transcript showed comparable dynamics of the cell-associated HIV-1 RNA (Fig. 3b). At relatively early time points, the CM CD4 subset contained a relatively high level of cell-associated HIV-1 RNA (Fig. 3b). The naïve and TM subsets contained relatively low level of cell-associated RNA initially but achieved similar levels as in the CM subset at the last time point. The EM subset contained the lowest level of cell-associated HIV-1 RNA at the last time point (Fig. 3b). These results suggested that the CM CD4 subset was preferentially infected by the 40700 T/F virus during early infection. Because HIV-1 mainly target the mucosal sites during acute infection, where the majority of the EM cells reside, the relatively lower infectivity of 40700 in the EM cells might explain why the plasma VL in 40700 was relatively low at the earliest stage of acute infection as compared to the R5 group (Fig. 2b).

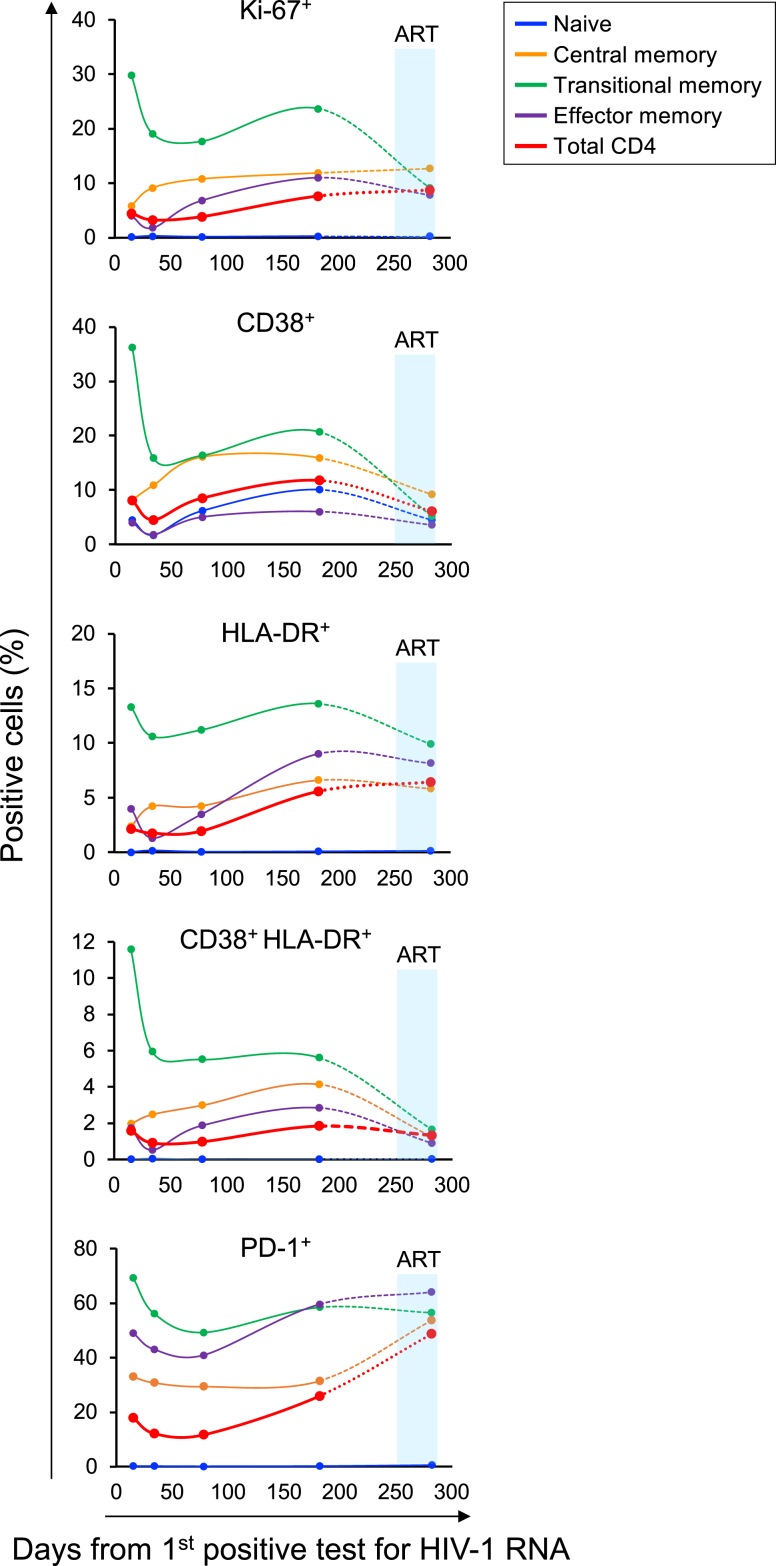

Heightened CD4+ T cell activation over time

Immune activation is correlated with CD4 decline in HIV-1 infection.27,28 The rapid CD4 depletion in 40700 prompted us to determine the level of CD4+ T cell activation over time. Quantification of the expression of T cell activation markers showed that after acute infection, coincident with a brief drop of plasma VL (Fig. 2b), there was a temporary decrease in CD4 activation and proliferation (Fig. 4). However, instead of achieving a steady-state as observed in most people infected with HIV-1,27 the level of CD4+ T cell activation increased after this brief decline. Among different CD4 subsets, the TM subset expressed the highest level of activation and proliferation markers (Fig. 4). The naïve CD4 subset was negative for all investigated markers except for CD38 (Fig. 4). The lack of the Ki-67 expression in the naïve subset suggested that, as previously observed in X4-tropic SHIV infected macaques,26 the naïve CD4+ T cells, which were productively infected and depleted in 40700, were largely quiescent. The level of CD4 activation and proliferation decreased upon ART. However, the expression of PD-1 did not decrease immediately after treatment (Fig. 4). Although the decrease in CD4 activation on day 282 was most likely due to ART (which initiated on day 266), given the relatively long interval between the last two time points (100 days), whether the reduction in CD4 activation was conclusively attributed to ART requires further investigation.

Fig. 4.

Determination of CD4+T cell activation and proliferation in participant 40700. The expression of activation and proliferation markers on total CD4+ T cells as well as on each CD4 subset was determined by flowcytometry. The percentage of cells positive for each marker is shown. The time frame when participant 40700 was on ART (from day 266 to day 282) is highlighted in red. Dotted lines were used to connect the last two time points because participant 40700 was on ART at the last time point.

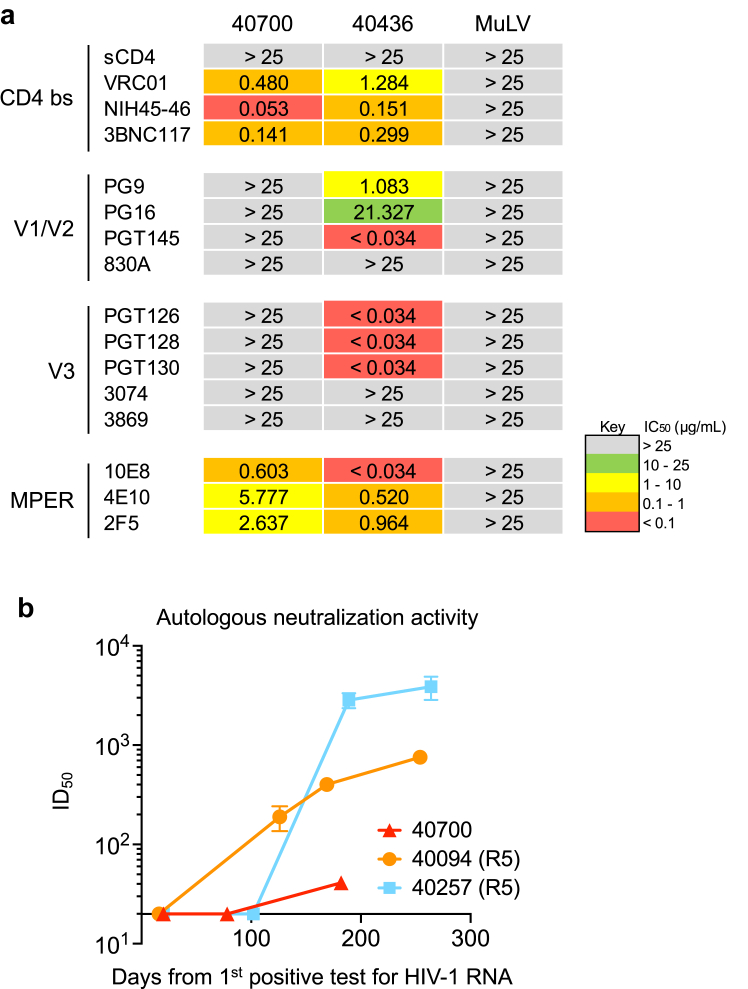

The 40700 T/F virus is resistant to bNAbs targeting the V1/V2 and V3 regions

X4 tropic HIV-1 from different subtypes tend to be more resistant to broadly neutralizing antibodies (bNAbs) targeting the V3 region.18,29, 30, 31 Determination of neutralization susceptibility to a panel of bNAbs showed that while the 40700 T/F virus can be neutralized by bNAbs targeting the CD4 binding site and MPER, it was completely resistant to all investigated bNAbs targeting the V1/V2 and V3 regions (Fig. 5a). Of note, the majority of R5 T/F viruses identified in the RV217 Thailand cohort were sensitive to the same panel of V1/V2 and V3 bNAbs, as demonstrated in our previous study.20 Therefore, the resistance to V1/V2 and V3 bNAbs is a unique feature for the 40700 T/F virus, rather than a commonly observed phenotype for the CRF01_AE HIV-1. Investigation of the kinetics of autologous neutralization activity showed that participant 40700 developed relatively low level of autologous neutralization activity compared with two infections established by R5 T/F viruses (Fig. 5b).

Fig. 5.

Neutralization susceptibility of the 40700 T/F virus to a panel of bNAbs and the autologous neutralization activity induced in 40700. (a) Susceptibility of the 40700 T/F virus to a panel of bNAbs targeting different regions of the HIV-1 envelope. An R5 tropic T/F virus from the same cohort (participant 40436) was used as control. The IC50 (μg/mL) of each bNAb is shown. The murine leukemia virus (MuLV) was used as negative control. (b) Autologous neutralization activity induced by the 40700 T/F virus. Two participants infected by R5 tropic T/F viruses from the same cohort (40257 and 40094) were used as controls.

Analysis of the V3 amino acid sequence identified that the conserved V3 N301 glycan site is lost in 40700 due to the T303I substitution (Supplementary Fig. S8a). Indeed, amino acid substitutions at the N301 glycan site were identified in nearly all X4 viruses in the RV217 Thailand cohort as we reported recently.18 As in most of the CRF01_AE viruses, the N332 glycan site shifted to the N334 position in 40700 (Supplementary Fig. S8a). In comparison to the CRF01_AE consensus sequence, the 40700 T/F virus has two positively charged amino acid substitutions in V3, including the Q313R mutation at the V3 crown (Supplementary Fig. S8a). Moreover, the 40700 T/F virus has a longer V2 loop and an additional N-linked glycan site in the V2 loop as compared to most R5 T/F viruses in the same cohort (Supplementary Fig. S8b and c). There are a total of 30 N-linked glycan sites in the envelope of the 40700 T/F virus, which are comparable to the average number of N-linked glycan sites (N = 29) observed in the R5 group. These findings identified unique genetic features and N-linked glycan arrangements in the V1/V2 and V3 regions of the 40700 T/F virus.

We previously demonstrated that mutations at the N301 glycan site can function as driver mutations for coreceptor switching during natural HIV-1 infection.18 Mutations in V1/V2 regions could also impact the coreceptor usage of HIV-1.32,33 Therefore, we determined the impact of the N301 glycan mutations and the additional V2 glycan on coreceptor usage of the 40700 T/F virus. Deletion of the additional V2 glycan site did not have observable impact on the coreceptor usage of the 40700 T/F virus (Supplementary Fig. S9). However, restoration of the N301 glycan site by mutations K302N and I303T recovered CCR5 usage and partially impaired the CXCR4 usage of the 40700 T/F virus (Supplementary Fig. S9).

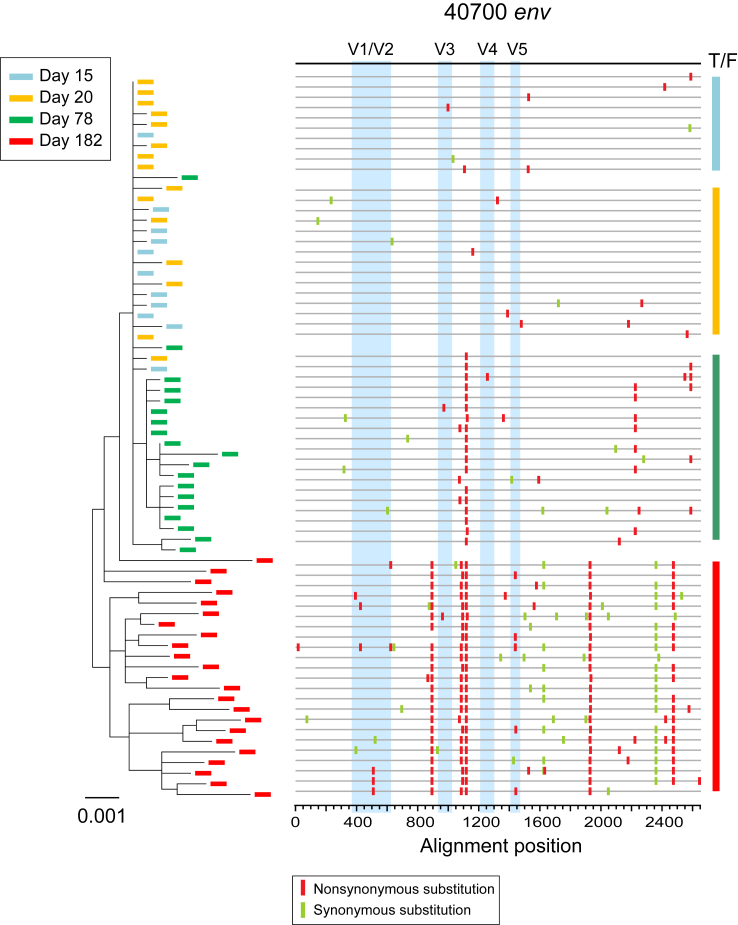

Investigation of longitudinal envelope evolution in 40700 showed that the viral population diversified from the T/F virus by accumulation of point mutations (Fig. 6). Interestingly, during early viral evolution, the variable loops were relatively conserved while most of the fixed or predominant mutations emerged in the conserved regions (Fig. 6). This could be associated with the relatively low level of autologous neutralization response in 40700. There is no change in the total number of N-linked glycan sites during the first 182 days of viral evolution. The viral population at day 182 contained an average of 30 N-linked glycans in env, the same as in the 40700 T/F virus.

Fig. 6.

Phylogenetic tree and highlighter plot showing longitudinal viral evolution in participant 40700. Longitudinal env sequences were obtained by SGA. Evolution of the 40700 T/F virus is illustrated by phylogenetic tree (left) and highlighter plot (right). Sequences from different time points (days from the 1st positive test for HIV-1 RNA) are color coded. The phylogenetic tree was constructed using the maximum likelihood method. In the highlighter plot, the black line on the top represents the T/F virus. The red and green tics indicate non-synonymous and synonymous substitutions compared to the T/F virus, respectively. The variable loops are shaded in blue.

Discussion

The current study demonstrates that HIV-1 with strict X4 tropism can be transmitted through the mucosal route in people with wild-type CCR5 genotype and can cause rapid CD4 depletion in the infected individual. This finding, together with the observation that the 40700 T/F virus is resistant to bNAbs targeting the V1/V2 and V3 regions, underscores the need to monitor the transmission and spread of highly pathogenic X4 HIV-1, which tend to be resistant bNAbs targeting the variable loops.18,29, 30, 31

While it has been well established that R5 tropic HIV-1 has transmission advantage than X4 tropic virus, the underlying mechanisms remain poorly understood. Among CCR5 tropic HIV-1, several functional and structural features are considered to associate with higher transmissibility, such as shorter and less glycosylated variable loops34, 35, 36 and resistance to interferons,37 although some of these features are still controversial and are likely subtype-dependent. However, a long-term question is why X4 viruses are less transmissible despite CXCR4 being expressed on a broader range of CD4+ T cells than CCR5. The current study, together with our previous findings on HIV-1 coreceptor switch,18 suggest that virus preference for different CD4 subsets could be an important determinant underlying the distinct transmissibility of R5 and X4 HIV-1. In our recent study, tracking the coreceptor switch of the T/F virus demonstrated that, immediately after the origin of the earliest X4 virus, the viral population diverged in vivo in terms of CD4 subset targeting.18 While the R5 viral population remained predominant in the EM and TM CD4 subsets, the emerging X4 viruses lost advantage in the EM and TM subsets, while gaining advantage in the CM and naïve subsets.18 In participant 40700, the CM CD4 subset was preferentially infected during early infection stages, while the EM and TM CD4 subsets showed lower levels of infection. Because the EM CD4+ T cells are more abundant in the mucosal tissues than the CM and naïve CD4+ T cells,38, 39, 40 the replication advantage of the R5 virus in the EM CD4+ T cells may provide an advantage during mucosal transmission. Moreover, the EM and TM cells are likely to have higher viral burst size than the naïve and CM cells due to their more activated status, and thus release more virions into the plasma. Indeed, in all participants harboring X4 viruses in the RV217 Thailand cohort, the R5 viruses remained predominant in the plasma.18 This could be another reason for the transmission advantage of R5 tropic HIV-1. Our findings also provide evidence that the EM and TM CD4 subsets could play a more important role in mediating mucosal HIV-1 transmission than the CM and naïve subsets (otherwise, the X4 virus would have a higher chance to be transmitted, given their replication advantage in the CM and naïve CD4 subsets in vivo). However, more cases need to be studied in order to draw broader conclusions. A better understanding of the CD4 subset preference in determining the transmissibility of HIV-1 could open new possibilities for preventing HIV-1 transmission (for example, by downregulation of CCR5 expression on the EM and TM CD4 subsets).

While the altered CD4 subset preference towards the naïve and CM cells may compromise the transmissibility of X4 tropic HIV-1, it could enhance its pathogenicity. In 40700, the rapid CD4 depletion was mainly due to the loss of naïve and CM CD4 subsets. In line with this finding, our recent study on coreceptor switch showed that upon the origin of the X4 viruses in vivo, the CM and naïve CD4 subsets declined faster than the EM and TM subsets.18 Similarly to what was previously observed in macaques infected by X4-tropic SHIV(26), the naïve CD4+ T cells were productively infected and depleted in 40700 despite the quiescent state. The exponentially increased viral load in the naïve CD4 compartment was also similar as previously observed in the macaque model.26 The mechanisms for productive infection and depletion of the resting naïve CD4+ T cells in vivo require further investigation. In addition to productive infection, the role of non-productive (abortive) infection in naive CD4+ T cell depletion also requires further study because abortive infection can induce pyroptosis.41 In addition to direct infection of the naïve CD4+ T cells, the high viral burden in the CM CD4 subset, which is essential for CD4 hemostasis as demonstrated in SIV infected natural hosts and people infected by HIV-1,42, 43, 44, 45 could be another reason for the enhanced pathogenicity of X4 tropic HIV-1. Indeed, in nonprogressive SIV infection, a low viral burden in the CM CD4 subset and the lack of chronic immune activation are considered as two hallmarks.45, 46, 47 While the exact mechanisms underlying the nonprogressive SIV infection remains incompletely understood, emerging evidence suggests that CCR5 could be dispensable for SIV in the natural hosts. Alternative coreceptors, such as CXCR6, might function as the cognate coreceptor for SIV to establish the infection in natural hosts.48 These are supported by the following evidence. First, low levels of CCR5 expression on the CD4+ T cells is observed in multiple species, while the rates of SIV transmission are very high in the wild.49, 50, 51 Second, sooty mangabeys (SM) with defective CCR5 gene (homozygous CCR5-null animals) can acquire SIV infection with similar frequency as the CCR5 wild type animals.52 Taken together, the coreceptor-directed CD4 subset targeting in both HIV and SIV infections, as well as its contribution to viral pathogenesis and chronic immune activation, require more comprehensive studies in the future.

The current study has several limitations. First, we only focused on a single participant. More cases need to be studied in the future to draw broader conclusions about X4 HIV-1 transmission and pathogenesis. Second, because samples from the tissues such as lymph nodes were not available in the current study, the observations were based on cells from peripheral blood. Future research using animal model could lead to a better understanding of the immunopathogenesis of this X4 tropic T/F HIV-1.

Contributors

H.S. and M.H.M. designed the study. M.H.M., S.S., M.B., E.S-B., M.Z., L.W., F.D-M., A.H. and H.S. performed the experiments. M.H.M., M.B., E.S-B., S.T., and H.S. performed viral sequencing and genetic analysis. M.Z., L.W., and V.R.P. contributed to viral neutralization assay. R.T. performed CCR5 genotyping. D.K. and L.F. modeled the CD4 dynamics. Y.T. contributed to the design and data analysis of the flow cytometry and cell sorting experiments. N.C. provided the protocols for total and integrated HIV-1 DNA assay, cell-associated HIV-1 RNA assay, and contributed to discussions of the experiments and data. L.A.E., N.L.M., and M.L.R. were involved in recruiting of the clinical cohorts, analysis of the clinical data and supplied clinical samples. H.S. wrote the manuscript with the input from all authors. H.S. and M.H.M accessed and verified all the data. All authors read the manuscript and approved the submission.

Data sharing statement

All newly generated nucleic acid sequences in the current study were deposited in GenBank with accession numbers OR231807-OR231874 and will be publicly available before publication.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the study participants of the RV217 Thailand cohort. This study was supported by the Institute of Human Virology, University of Maryland School of Medicine. Part of the study was supported by cooperative agreements between the Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine, Inc., and the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD). M.H.M. and H.S. were supported by the NIH grants R21AI147893 and R01AI181601. A.H. was supported by the NIH grant R01AI120008.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2024.105410.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Shaw G.M., Hunter E. HIV transmission. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2(11) doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keele B.F., Giorgi E.E., Salazar-Gonzalez J.F., et al. Identification and characterization of transmitted and early founder virus envelopes in primary HIV-1 infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(21):7552–7557. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802203105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Michael N.L., Nelson J.A., KewalRamani V.N., et al. Exclusive and persistent use of the entry coreceptor CXCR4 by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 from a subject homozygous for CCR5 delta 32. J Virol. 1998;72(7):6040–6047. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.7.6040-6047.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smolen-Dzirba J., Rosinska M., Janiec J., et al. HIV-1 infection in persons homozygous for CCR5-delta 32 allele: the next case and the review. AIDS Rev. 2017;19(4):219–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henrich T.J., Hanhauser E., Hu Z., et al. Viremic control and viral coreceptor usage in two HIV-1-infected persons homozygous for CCR5 Delta32. AIDS. 2015;29(8):867–876. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Theodorou I., Meyer L., Magierowska M., Katlama C., Rouzioux C. HIV-1 infection in an individual homozygous for CCR5 delta 32. Seroco Study Group. Lancet. 1997;349(9060):1219–1220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gorry P.R., Zhang C., Wu S., et al. Persistence of dual-tropic HIV-1 in an individual homozygous for the CCR5 Delta 32 allele. Lancet. 2002;359(9320):1832–1834. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08681-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chalmet K., Dauwe K., Foquet L., et al. Presence of CXCR4-using HIV-1 in patients with recently diagnosed infection: correlates and evidence for transmission. J Infect Dis. 2012;205(2):174–184. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Song H., Ou W., Feng Y., et al. Disparate impact on CD4 T cell count by two distinct HIV-1 phylogenetic clusters from the same clade. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116(1):239–244. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1814714116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Armani-Tourret M., Zhou Z., Gasser R., et al. Mechanisms of HIV-1 evasion to the antiviral activity of chemokine CXCL12 indicate potential links with pathogenesis. PLoS Pathog. 2021;17(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1009526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiang C., Parrish N.F., Wilen C.B., et al. Primary infection by a human immunodeficiency virus with atypical coreceptor tropism. J Virol. 2011;85(20):10669–10681. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05249-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robb M.L., Eller L.A., Kibuuka H., et al. Prospective study of acute HIV-1 infection in adults in east africa and Thailand. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(22):2120–2130. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1508952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Song H., Giorgi E.E., Ganusov V.V., et al. Tracking HIV-1 recombination to resolve its contribution to HIV-1 evolution in natural infection. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):1928. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04217-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang M., Gaschen B., Blay W., et al. Tracking global patterns of N-linked glycosylation site variation in highly variable viral glycoproteins: HIV, SIV, and HCV envelopes and influenza hemagglutinin. Glycobiology. 2004;14(12):1229–1246. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwh106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tamura K., Stecher G., Peterson D., Filipski A., Kumar S. MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30(12):2725–2729. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marichannegowda M.H., Song H. Immune escape mutations selected by neutralizing antibodies in natural HIV-1 infection can alter coreceptor usage repertoire of the transmitted/founder virus. Virology. 2022;568:72–76. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2022.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salazar-Gonzalez J.F., Salazar M.G., Keele B.F., et al. Genetic identity, biological phenotype, and evolutionary pathways of transmitted/founder viruses in acute and early HIV-1 infection. J Exp Med. 2009;206(6):1273–1289. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marichannegowda M.H., Zemil M., Wieczorek L., et al. Tracking coreceptor switch of the transmitted/founder HIV-1 identifies co-evolution of HIV-1 antigenicity, coreceptor usage and CD4 subset targeting: the RV217 acute infection cohort study. EBioMedicine. 2023;98 doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2023.104867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vandergeeten C., Fromentin R., Merlini E., et al. Cross-clade ultrasensitive PCR-based assays to measure HIV persistence in large-cohort studies. J Virol. 2014;88(21):12385–12396. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00609-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuriakose Gift S., Wieczorek L., Sanders-Buell E., et al. Evolution of antibody responses in HIV-1 CRF01_AE acute infection: founder envelope V1V2 impacts the timing and magnitude of autologous neutralizing antibodies. J Virol. 2023;97(2) doi: 10.1128/jvi.01635-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Faraway J. 2nd ed. Chapman & Hall/CRC Texts in Statistical Science; 2016. Extending the linear model with R: generalized linear, mixed effects and nonparametric regression models. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giorgi E.E., Funkhouser B., Athreya G., Perelson A.S., Korber B.T., Bhattacharya T. Estimating time since infection in early homogeneous HIV-1 samples using a Poisson model. BMC Bioinf. 2010;11:532. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lengauer T., Sander O., Sierra S., Thielen A., Kaiser R. Bioinformatics prediction of HIV coreceptor usage. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25(12):1407–1410. doi: 10.1038/nbt1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marichannegowda M., Heredia A., Wang Y., Song H. bioRxiv; 2024. Genetic signatures in the highly virulent subtype B HIV-1 conferring immune escape to V1/V2 and V3 broadly neutralizing antibodies. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Swanstrom R., Coffin J. HIV-1 pathogenesis: the virus. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2(12) doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a007443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nishimura Y., Brown C.R., Mattapallil J.J., et al. Resting naive CD4+ T cells are massively infected and eliminated by X4-tropic simian-human immunodeficiency viruses in macaques. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(22):8000–8005. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503233102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deeks S.G., Kitchen C.M., Liu L., et al. Immune activation set point during early HIV infection predicts subsequent CD4+ T-cell changes independent of viral load. Blood. 2004;104(4):942–947. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hazenberg M.D., Otto S.A., van Benthem B.H., et al. Persistent immune activation in HIV-1 infection is associated with progression to AIDS. AIDS. 2003;17(13):1881–1888. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200309050-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin N., Gonzalez O.A., Registre L., et al. Humoral immune pressure selects for HIV-1 CXC-chemokine receptor 4-using variants. EBioMedicine. 2016;8:237–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.04.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sok D., Pauthner M., Briney B., et al. A prominent site of antibody vulnerability on HIV envelope incorporates a motif associated with CCR5 binding and its camouflaging glycans. Immunity. 2016;45(1):31–45. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Registre L., Moreau Y., Ataca S.T., et al. HIV-1 coreceptor usage and variable loop contact impact V3 loop broadly neutralizing antibody susceptibility. J Virol. 2020;94(2) doi: 10.1128/JVI.01604-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ogert R.A., Lee M.K., Ross W., Buckler-White A., Martin M.A., Cho M.W. N-linked glycosylation sites adjacent to and within the V1/V2 and the V3 loops of dualtropic human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolate DH12 gp120 affect coreceptor usage and cellular tropism. J Virol. 2001;75(13):5998–6006. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.13.5998-6006.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koito A., Stamatatos L., Cheng-Mayer C. Small amino acid sequence changes within the V2 domain can affect the function of a T-cell line-tropic human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope gp120. Virology. 1995;206(2):878–884. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Derdeyn C.A., Decker J.M., Bibollet-Ruche F., et al. Envelope-constrained neutralization-sensitive HIV-1 after heterosexual transmission. Science. 2004;303(5666):2019–2022. doi: 10.1126/science.1093137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haaland R.E., Hawkins P.A., Salazar-Gonzalez J., et al. Inflammatory genital infections mitigate a severe genetic bottleneck in heterosexual transmission of subtype A and C HIV-1. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chohan B., Lang D., Sagar M., et al. Selection for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycosylation variants with shorter V1-V2 loop sequences occurs during transmission of certain genetic subtypes and may impact viral RNA levels. J Virol. 2005;79(10):6528–6531. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.10.6528-6531.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Iyer S.S., Bibollet-Ruche F., Sherrill-Mix S., et al. Resistance to type 1 interferons is a major determinant of HIV-1 transmission fitness. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114(4):E590–E599. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1620144114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grossman Z., Meier-Schellersheim M., Paul W.E., Picker L.J. Pathogenesis of HIV infection: what the virus spares is as important as what it destroys. Nat Med. 2006;12(3):289–295. doi: 10.1038/nm1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bromley S.K., Thomas S.Y., Luster A.D. Chemokine receptor CCR7 guides T cell exit from peripheral tissues and entry into afferent lymphatics. Nat Immunol. 2005;6(9):895–901. doi: 10.1038/ni1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Debes G.F., Arnold C.N., Young A.J., et al. Chemokine receptor CCR7 required for T lymphocyte exit from peripheral tissues. Nat Immunol. 2005;6(9):889–894. doi: 10.1038/ni1238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Doitsh G., Galloway N.L., Geng X., et al. Cell death by pyroptosis drives CD4 T-cell depletion in HIV-1 infection. Nature. 2014;505(7484):509–514. doi: 10.1038/nature12940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Letvin N.L., Mascola J.R., Sun Y., et al. Preserved CD4+ central memory T cells and survival in vaccinated SIV-challenged monkeys. Science. 2006;312(5779):1530–1533. doi: 10.1126/science.1124226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Potter S.J., Lacabaratz C., Lambotte O., et al. Preserved central memory and activated effector memory CD4+ T-cell subsets in human immunodeficiency virus controllers: an ANRS EP36 study. J Virol. 2007;81(24):13904–13915. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01401-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Descours B., Avettand-Fenoel V., Blanc C., et al. Immune responses driven by protective human leukocyte antigen alleles from long-term nonprogressors are associated with low HIV reservoir in central memory CD4 T cells. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(10):1495–1503. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Paiardini M., Cervasi B., Reyes-Aviles E., et al. Low levels of SIV infection in sooty mangabey central memory CD(4)(+) T cells are associated with limited CCR5 expression. Nat Med. 2011;17(7):830–836. doi: 10.1038/nm.2395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brenchley J.M., Silvestri G., Douek D.C. Nonprogressive and progressive primate immunodeficiency lentivirus infections. Immunity. 2010;32(6):737–742. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chahroudi A., Bosinger S.E., Vanderford T.H., Paiardini M., Silvestri G. Natural SIV hosts: showing AIDS the door. Science. 2012;335(6073):1188–1193. doi: 10.1126/science.1217550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wetzel K.S., Yi Y., Elliott S.T.C., et al. CXCR6-Mediated simian immunodeficiency virus SIVagmSab entry into sabaeus african green monkey lymphocytes implicates widespread use of non-CCR5 pathways in natural host infections. J Virol. 2017;91(4) doi: 10.1128/JVI.01626-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pandrea I., Apetrei C., Gordon S., et al. Paucity of CD4+CCR5+ T cells is a typical feature of natural SIV hosts. Blood. 2007;109(3):1069–1076. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-024364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ma D., Jasinska A., Kristoff J., et al. SIVagm infection in wild African green monkeys from South Africa: epidemiology, natural history, and evolutionary considerations. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ma D., Jasinska A.J., Feyertag F., et al. Factors associated with siman immunodeficiency virus transmission in a natural African nonhuman primate host in the wild. J Virol. 2014;88(10):5687–5705. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03606-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Riddick N.E., Hermann E.A., Loftin L.M., et al. A novel CCR5 mutation common in sooty mangabeys reveals SIVsmm infection of CCR5-null natural hosts and efficient alternative coreceptor use in vivo. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.