ABSTRACT

Background: The incidence of mental illness has risen since the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. The number of healthcare workers (HCWs) needing mental health support has increased significantly.

Objective: This secondary analysis of qualitative data explored the coping strategies of migrant HCWs living in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic. Our aim was to identify the coping strategies used by migrant HCWs, and how they could be explored post-pandemic as support mechanisms of an increasingly diverse workforce.

Method: As part of the United Kingdom Research study into Ethnicity And COVID-19 outcomes among Healthcare workers (UK-REACH), we conducted in-depth semi-structured interviews and focus groups with clinical and non-clinical HCWs across the UK, on Microsoft Teams, from December 2020 to July 2021. We conducted a thematic analysis using Braun and Clarke’s framework to explore the lived experiences of HCWs born overseas and living in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic. The key themes that emerged were described using Lazarus and Folkman’s transactional model of stress and coping.

Results: The emerging themes include stressors (situation triggering stress), appraisal (situation acknowledged as a source of stress), emotion-focused coping (family and social support and religious beliefs), problem-focused coping (engaging in self-care, seeking and receiving professional support), and coping strategy outcomes. The participants described the short-term benefit of the coping strategies as a shift in focus from COVID-19, which reduced their anxiety and stress levels. However, the long-term impact is unknown.

Conclusion: We found that some migrant HCWs struggled with their mental health and used various coping strategies during the pandemic. With an increasingly diverse healthcare workforce, it will be beneficial to explore how coping strategies (family and social support networks, religion, self-care, and professional support) could be used in the future and how occupational policies and infrastructure can be adapted to support these communities.

KEYWORDS: Healthcare workers, mental health, coping strategies, migrant, COVID-19 pandemic

HIGHLIGHTS

Migrant (non-UK-born) HCWs used various coping strategies to sustain their mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The study conceptualized the coping mechanisms that enabled participants to cope with the COVID-19 pandemic crisis, using Lazarus and Folkman's transactional model of stress and coping.

Future research should explore whether short-term gains due to coping during the pandemic were maintained in the long term.

Abstract

Antecedentes: Los trastornos mentales continúan incrementándose desde la pandemia por la COVID-19. El número de trabajadores de la salud (TSs) que requieren de apoyo en salud mental se ha incrementado significativamente.

Objetivo: Este análisis secundario de información cualitativa exploró las estrategias de afrontamiento de los trabajadores de la salud migrantes viviendo en el Reino Unido durante la pandemia por la COVID-19. El objetivo fue el identificar las estrategias de afrontamiento empleadas por los TSs migrantes y cómo podrían explorarse luego de la pandemia como medios de apoyo para una fuerza laboral cada vez más diversa.

Método: Como parte del Estudio del Reino Unido sobre Etnicidad y Consecuencias de la COVID-19 en TSs (UK-REACH por sus siglas en inglés), se realizaron entrevistas semiestructuradas a profundidad y grupos focales con TSs clínicos y no clínicos a lo largo del Reino Unido a través de Microsoft Teams, desde diciembre del 2020 hasta julio del 2021. Realizamos un análisis temático empleando el marco conceptual de Braun y Clarke para explorar las experiencias de vida de los TSs nacidos en el extranjero, pero que viven en el Reino Unido durante la pandemia por la COVID-19. Los temas principales que surgieron a partir de la información se describieron empleando el Modelo Transaccional de Lazarus y Folkman de Estrés y Afrontamiento.

Resultados: Los temas que surgieron incluyeron los factores estresantes (estrés asociado a gatillantes situacionales), las valoraciones (reconocimiento de situaciones como fuentes de estrés), el afrontamiento centrado en emociones (apoyo social y familiar, y creencias religiosas), el afrontamiento enfocado en problemas (involucrarse en el autocuidado y en buscar y recibir apoyo profesional) y los resultados de las estrategias de afrontamiento. Los participantes describieron el beneficio a corto plazo de las estrategias de afrontamiento como un cambio en el enfoque que se le brindaba a la COVID-19, lo cual disminuyó sus niveles de ansiedad y de estrés. No obstante, el impacto a largo plazo es desconocido.

Conclusión: Se encontró que algunos TSs migrantes presentaron dificultad con su salud mental y que emplearon diferentes estrategias de afrontamiento durante la pandemia. Considerando una creciente y diversa fuerza laboral en el sector salud, resultaría beneficioso explorar cómo es que las estrategias a afrontamiento (las redes de apoyo familiares y sociales, la religión, el involucrarse en el autocuidado y el apoyo profesional) pueden ser empleadas en un futuro y en cómo las políticas ocupacionales y de infraestructura pueden ser adaptadas para brindar apoyo a estas comunidades.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Trabajadores de la salud, salud mental, estrategias de afrontamiento, migrantes, pandemia por la COVID-19

1. Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) declared coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) a pandemic in March 2020 (WHO, 2020). Two years later, WHO reported a 25% global increase in mental health problems triggered by the pandemic, with many people feeling worse (Kupcova et al., 2023; WHO, 2022). There is an increased rate of neuropsychiatric symptoms such as depression, anxiety, and irritability, among others (Flinders, 2022; Passmore, 2013; Rogers et al., 2020). The constraints on access to mental health care and support during the COVID-19 pandemic had a significant impact on people’s mental state and well-being (Yusuf et al., 2024). This is especially common in ethnic minority groups with pre-existing mental health inequalities (Smith et al., 2020). It is important to focus on the well-being of ethnically diverse healthcare workers (HCWs) because of the health inequalities that exist. Health inequalities have been found in the use of health services for common mental disorders (Cooper et al., 2013) and the incidence of diagnosis of severe mental illness (Halvorsrud et al., 2019). Discrimination in the workplace is likely to be a contributor to health inequalities because it causes stress, leading to mental health problems (Tinner & Alonso Curbelo, 2024).

The emergence of a global pandemic exacerbated the underlying pressures of the UK National Health Service (NHS), which affected the mental health of many HCWs (Greenberg et al., 2021; Qureshi et al., 2022). Within the NHS, approximately 15% of HCWs report non-British nationality (Baker, 2022). Evidence suggests that individuals from ethnic minority backgrounds experienced greater mental health needs compared to their White counterparts during the COVID-19 pandemic (Proto & Quintana-Domeque, 2021). The mental health of HCWs deteriorated significantly during the pandemic, with many reporting increased rate of stress, anxiety, fear, trauma, and guilt triggered by prolonged lockdowns and excessive exposure to deaths (Qureshi et al., 2022).

Although all HCWs were impacted by the pandemic, migrant HCWs, especially those from ethnic minorities, were at an elevated risk of infection owing to redeployment to areas outside their professional training, increasing their levels of stress and anxiety (Zuzer Lal et al., 2024). There is a clear and urgent need to address the mental health of diverse healthcare workforces through effective prevention, early detection, and treatment (Greenberg, 2022). The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated the already stretched resources and pressurized working conditions within the NHS, with HCWs feeling stressed and experiencing burnout (Søvold et al., 2021). Supporting HCWs to develop their own coping strategies may have a wider positive impact on healthcare services (Diver et al., 2021).

In this analysis, we used the transactional model of stress and coping to conceptualize coping. The transactional model hypothesized and acknowledged the fact that stress happens when an individual encounters a challenging situation. The individual then evaluates the situation’s demands on them, determines whether they can handle it, and decides on a coping strategy to use (Larsen, 2007), be it problem-focused and/or emotion-focused coping (Algorani & Gupta, 2023; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Problem-focused coping addresses the cause of stress and take steps to solve it, whereas emotion-focused coping manages the emotions and response to the stressor rather than addressing the problem (Raypole & Legg, 2020). The themes generated from this secondary analysis of qualitative data were derived using this model, and empirically support Lazarus and Folkman’s (1984) hypothesis.

Coping and adjusting to problems are the transactional relationships that exist between a person and their environment (Berjot & Gillet 2011; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Research has pointed to the possibilities of recreational activities supporting mental health recovery broadly (Litwiller et al., 2017). Furthermore, physical and spiritual resources were identified as enablers for HCWs to cope well during the pandemic (Che Yusof et al., 2022). Despite the pressure and heightened stress working in the health sector, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, previous research has found that HCWs used various types of wellness resources (Chen et al., 2020; Shechter et al., 2020) and meaning-focused coping, such as religion, as well as pursuing their own set goals to sustain their well-being (George et al., 2020).

Conceptualization of the coping strategy using the transactional model of stress and coping enabled critical analysis from a realist perspective. This can provide unique insights (Rees et al., 2023) by focusing primarily on the true-life experiences of HCWs, rather than social perception based on theories (Maxwell, 2023; Queen Mary University of London, 2021). Realism is an approach that facilitates transparency and enables situation to be explored to understand what works for whom and in what context (TASO, 2024). Understanding the experiences of HCWs from diverse backgrounds is essential to inform evidence-based interventions and areas for future research. This analysis sought to explore the experiences of migrant HCWs in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic. We aim to inform strategies to support the mental health of HCWs from diverse backgrounds post-pandemic, and to provide a basis for further helping HCWs to sustain their mental health and well-being.

2. Methods

2.1. Utilizing Lazarus and Folkman's theoretical transactional framework

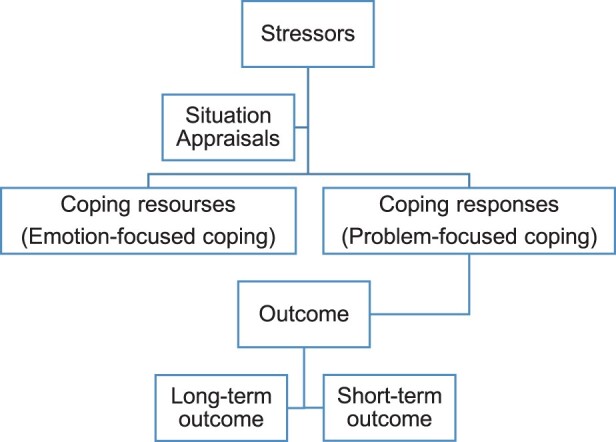

The study conceptualized the coping mechanisms that enabled participants to cope with the COVID-19 pandemic crisis using Lazarus and Folkman's transactional model of stress and coping (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984), as shown in Figure 1. This model empirically shows that COVID-19, and its perceived impact, is the stressor. This determined the coping resources and coping responses deployed by HCWs.

Figure 1.

Model adapted from Lazarus and Folkman's transactional model of stress and coping (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984).

2.2. Study design and setting

The United Kingdom Research study into Ethnicity And COVID-19 outcomes among Healthcare workers (UK-REACH) qualitative study explored the lived experiences of HCWs in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic. In this analysis, we explored the coping strategies of migrant (non-UK-born) HCWs living in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic. A detailed methodology for the wider UK-REACH protocol has previously been reported (Gogoi et al., 2021).

2.3. Study population

The primary study recruited 164 participants into the qualitative study of UK-REACH from all four nations of the UK. A purposive sample of participants was recruited to reflect the diverse population of the UK healthcare workforce. The research team provided the participants with a study information sheet, and informed consent was obtained prior to interviews and focus group discussions, which took place between December 2020 and July 2021. For this secondary analysis, the research team screened and selected participant transcripts based on demographic information and profession.

The inclusion criteria were migrant (non-UK-born) HCWs aged 18 years and above, including those who had trained in the UK; and being a resident in the UK during the pandemic and working in the healthcare sector, including the NHS and social care. Excluded from the analysis were HCWs born in the UK, irrespective of their ethnic background.

The transcripts of all participants recruited into the primary study were screened to determine eligibility for this secondary analysis. Data saturation principles for purposive sampling in qualitative research were used as guidance (Hennink & Kaiser, 2022). Data saturation is the point where new ideas are no longer emerging from participants’ interviews and enough data have been collected to reach a conclusion (Francis et al., 2009). After screening of the database, all eligible transcripts that met the inclusion criteria for the subanalysis were included in the data analysis. These comprised 39 participants’ transcripts, including seven individuals from one-to-one interviews and 32 individuals who participated in focus group discussions. The size of focus groups ranged from five to seven participants. The HCWs included in this study analysis were nurses, doctors, allied health professionals, social workers, pharmacists, administrative workers, and non-clinical HCWs.

2.4. Data collection

Four of the researchers (M. G., F. W., A. A. O., and L. B. N.) conducted semi-structured interviews and focus group discussions via Microsoft Teams or by telephone owing to the COVID-19 lockdown restrictions. This iterative pragmatic approach was used to account for the national lockdown policy during a global pandemic (Institute for Government Analysis, 2021). As part of this study, we conducted in-depth semi-structured interviews and focus groups with clinical and non-clinical HCWs from diverse ethnic backgrounds across the UK to explore the lived experiences of HCWs from diverse ethnic backgrounds born overseas but living in the UK.

The interview questions were classified into personal and professional life. The average interview and focus group discussions lasted for 60–90 min. Our choice of using semi-structured interviews and focus groups for qualitative data collection was made to identify personal experiences and insights, share sensitive information, and provide a shared environment for a more comprehensive understanding of HCWs’ experiences and opinions (Gill et al., 2008).

The UK-REACH Professional Expert Panel (PEP) and stakeholder group (STAG) developed the topic guide used to explore the lived experiences of HCWs working during the pandemic. This guide enabled the researchers to explore the participants’ fears, challenges, coping strategies, support, etc. During the interview and focus group discussions, the topic guide was refined iteratively as new key issues emerged.

The researchers are experienced qualitative researchers from diverse ethnic backgrounds, including diversity by age, gender, sex, ethnicity, migration status, and professional training. We consistently engaged in active reflectivity to determine how our backgrounds influenced the generation of themes. Two researchers were present during most of the discussions to record the sessions, and consent was obtained from each participant before the session was recorded. Recorded interviews and focus group discussions were then transcribed, anonymized, and checked for accuracy. The research team kept a reflexivity diary, and the process of bracketing was conducted to limit researchers’ presuppositions (Tufford & Newman, 2012).

2.5. Analysis

The interviews were professionally transcribed, and the researchers (J. O. A., J. C., M. G., I. Q., and A. A. O.) thematically analysed the qualitative data (Braun & Clarke, 2006). The process was iterative, with researchers familiarizing themselves with the data. Thereafter, J. O. A. undertook coding for the coping strategies used by HCWs based on their lived experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. The code was discussed collaboratively with all researchers. Discrepancies were discussed and resolved. Themes were agreed only once a consensus had been reached among the research team.

We explored the realist perspective that is true-life experiences, rather than social perception based on theories (Maxwell, 2023). The realist perspective emphasizes true-life experiences over social perception. This enabled the qualitative analysis to focus on the lived experiences of migrant HCWs. This approach allowed thematic organization of the narratives, enabling a comparison of the responses to the questions, which is consistent with Braun and Clarke’s (2023) recommendations on conducting and reporting thematic analysis.

The initial codes were generated inductively and independently, and a coding framework was developed. These themes were conceptualized deductively using a shared topic guide (Braun & Clarke, 2023). This approach was combined with a more inductive approach as more codes describing participants’ coping strategies emerged. Furthermore, J. O. A., J. C., M. G., I. Q., and A. A. O. regularly discussed the coding framework and updated the framework using the topic guide. All codes were transferred into an Excel spreadsheet.

The authors discussed the themes iteratively using Lazarus and Folkman's theoretical framework (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984), which guided the themes generated from the data analysis. Following a process of reviewing, defining, and naming the themes, the authors produced exemplars. The final themes generated were reviewed and agreed by all authors. The reports by Maher et al. (2018) and Johnson et al. (2020) were used to ensure that the data were reliable, accurate, and complete. This was achieved by constant communication between researchers, taking time to understand and reflect on the data independently, and active reflexivity reinforced the credibility of the data. This also allowed each researcher to reflect on bias and ensure that it did not affect the integrity of the findings but, rather, contributed towards its richness and generalizability.

3. Results

3.1. Participants’ demographic data

In total, 39 participants, comprising seven individuals from one-to-one interviews and 32 individuals from the focus group discussions, who met the inclusion criteria, were included in the analysis. The secondary data analysis focused on the coping strategies employed by migrant (non-UK-born) HCWs during the COVID-19 pandemic. The demographics of the research participants are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participants’ demographic data.

| Variable | Total count (n = 39) | % |

|---|---|---|

| Ethnicitya | ||

| Black African/Caribbean | 7 | 18 |

| Asian | 11 | 28 |

| White other | 8 | 21 |

| Unknown/other (but migrant HCW) | 13 | 33 |

| Profession | ||

| Doctor | 12 | 31 |

| Nurse | 9 | 23 |

| Allied health professional/social worker/pharmacist | 10 | 26 |

| Administrative/non-clinical | 7 | 18 |

| Unknown | 1 | 2 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 17 | 42 |

| Female | 21 | 53 |

| Unknown/other | 2 | 5 |

aEthnicity categories were selected using the UK Census (GOV.UK, 2021).

HCW = healthcare worker.

3.2. Data analysis using Lazarus and Folkman's theoretical framework

Based on the transactional model of stress and coping (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984), transactional relationships were evident in the way in which migrant HCWs handled the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the themes were derived by conceptualization of this model. The key themes that emerged from the data include: (1) stressors, i.e. situations triggering stress during the COVID-19 pandemic; (2) appraisal, i.e. situations acknowledged as a source of stress causing harm or deemed a threat to health and well-being; (3) coping resources (emotion-focused coping), i.e. family and social support, and religious beliefs; (4) coping responses (problem-focused coping), i.e. engaging in self-care, and seeking and receiving professional support; and (5) coping strategy outcomes, including short-term outcomes, i.e. mood change and focus change, and long-term outcomes, i.e. on mental health and physical health.

3.2.1. Stressors: situations triggering stress during the COVID-19 pandemic

The qualitative data clearly show that the increased levels of stress due to the effects of the pandemic on work conditions and private life, including responsibilities to others (e.g. children, aged parents), were a stressor, as HCWs were worried about their own health and that of their family members and about passing the virus on to them. The participants experienced challenges to their mental health due to prolonged use of personal protective equipment (PPE), excessive exposure to deaths resulting in flashbacks, and bereavement, in addition to childcare challenges, language barriers, and immigration challenges. These are the stressors and were a direct consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic.

When the first pandemic first happened, I was very nervous … I was driving myself crazy basically … and because I was wearing apron and gloves but then when I needed to reach out for my phone I couldn’t and I was driving myself a bit manic. (Female, pharmacist)

I think working in the critical care unit … was really hard for some of my peers in the sense that they were going home crying, it was just really taking a toll on their mood. (Unknown sex, doctor)

I’ve got aged parents … I think that the government should consider those who need dependants … so difficult and tedious to bring them in, and expensive and just a lot of nit-picking. (Male, doctor)

Many participants reported experiencing sleepless nights, anxiety, loneliness, fear, stress, and feeling depressed as a result of the pandemic. Exposure to the pandemic circumstances with limited opportunity to utilize adaptive coping strategies had an impact on the mental health and well-being of the participants.

The anxiety was large … the flashbacks that you get afterwards in the ICU with things I see, was terrible … . (Female, non-clinical HCW)

3.2.2. Appraisal: situations acknowledged as a source of stress causing harm or deemed a threat to health and well-being

Across the narratives, there were a wide range of activities described by participants that were used to minimize the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on their mental health. What was also evident from the COVID-19 situation was the preparedness of the NHS to deal with a pandemic and its impact on HCWs. There was no clear plan on how to protect the mental health and well-being of HCWs. Situation appraisal enabled the evaluation of the situation around HCWs during the pandemic.

Yeah, I think we will just have to admit that the first wave … the challenges that we faced, I think we just have to admit that we were not prepared … . (Male, nurse)

3.2.3. Coping resources (emotion-focused coping): responding to the overpowering emotions caused by the pandemic

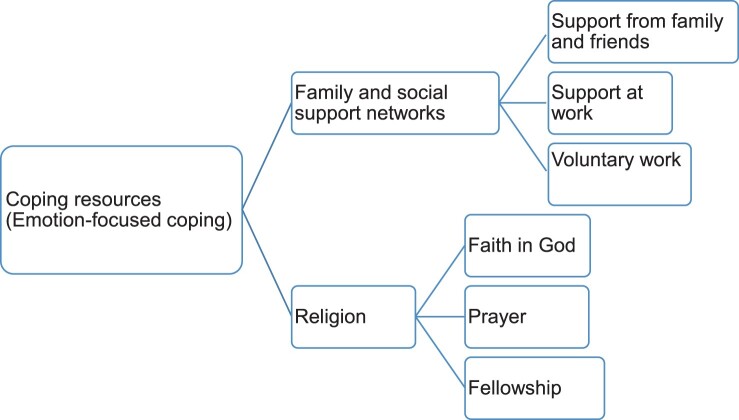

The participants used emotion-focused coping to deal with the overpowering emotions that they experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic. Figure 2 provides a schematic representation of these coping resources.

Figure 2.

Summary of the coping resources (emotion-focused coping) used by migrant healthcare workers.

3.2.3.1. Family and social support networks

Some participants spoke of having strong family support and that this enabled them to deal with the challenges of the pandemic. Spending more time with their family was a positive outcome of the pandemic for some migrant HCWs.

We just had this family time where we watched movies together … So that’s some of the things that really helped me throughout … . (Male, doctor)

One participant spoke about expanding her personal social network during the pandemic by supporting charity organizations. This served as escapism from the reality of the pandemic and enabled the participant to connect with people in the community.

I'm not really very good with coping mechanism in my personal life other than keeping myself busy and that’s what I did. In fact, my kids came with me in a lot of the voluntary work that I did, packing food parcels and delivering food parcels for the local mosque and charity organization … so that part of it we were always connected. (Female, non-clinical HCW)

3.2.3.2. Religion

Religion is an emotion-focused coping resource that was used by the participants. This enabled them to focus on seeking divine or spiritual assistance rather than focusing on the problem itself.

As Christians, the faith we have in God … I was very confident … knowing that I’ve got a Divine protection. So, my faith played a strong role in that. (Male, doctor)

Participants referred to their religious beliefs as their source of strength and inspiration in that it provided reassurance of divine protection. Keeping in touch with their religious community also helped some participants to cope with anxiety and loneliness.

My inspiration really mainly is if I don’t have my faith in God and my family, I think I’m going to be insane this time now with the emotional trauma that we receive during these trying times. (Male, nurse).

I mean the one thing it did do was it got me back in touch with my faith and that was while I was in the mortuary. I wasn’t a practising Christian but seeing all that death … I think that was what got me after a while. (Female, doctor)

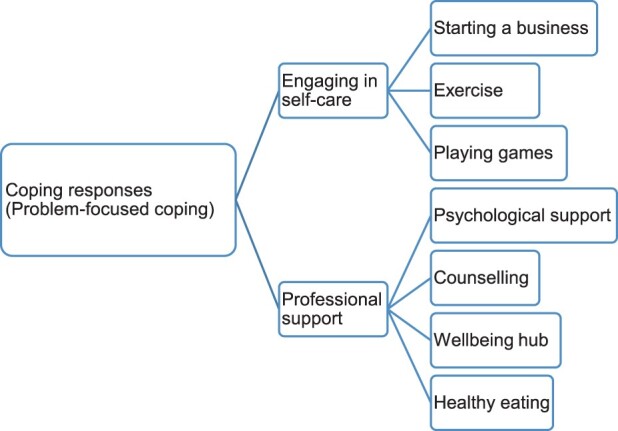

3.2.4. Coping responses (problem-focused coping): responding to the stress caused by the pandemic.

The participants discussed utilizing professional support provided by their employers in addition to engaging in self-care activities to respond to the stress caused by COVID-19 pandemic. These coping responses are summarized in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Summary of the coping responses (problem-focused coping) used by migrant healthcare workers.

3.2.4.1. Engaging in self-care

Participants actively engaged in problem-focused coping responses to mitigate the ripple effect of the pandemic on their mental health and well-being. Engaging in self-care activities such as exercise, walking, running, meditation, yoga, and gardening helped these participants to cope with the pressures of the pandemic (Khasnabis et al., 2010). Puzzles, games, and playing video games were also very helpful tools for distraction, as well as entrepreneurial interests after work to distract from the pandemic situation when isolation occurred. Engaging in self-care activities helped some participants to cope with the stress and anxiety that they experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic. Some participants were instrumental in bringing communities together at a time when face-to-face contact was impossible, by forming online exercise groups and using various ways to keep the mind and body healthy.

I started a business … so I think that shifted my focus a lot from the pandemic to a totally different thing! So, I wasn’t ruminating too much on how my life is being affected and how I can go home, and my attention was shifted somehow, so that helped me cope a little I think. (Female, allied health professional)

Me and my husband … go for a walk in the evenings … I’m lucky enough to have like a little gym area in my home for exercise and stuff and keeping myself right, mentally. (Female, nurse)

I bought myself a new video game console, which I don’t usually play video games, but it’s helped me through this period. (Male, doctor)

… Something really as silly as sharing a playlist of music on Spotify where we all had the same playlist … it’s been really helpful. (Female, allied health professional)

3.2.4.2. Professional support

During the COVID-19 pandemic, although healthcare organizations could not alleviate the consequences of the disease on HCWs at the time, they developed problem-focused strategies to help HCWs to cope with the mental health challenges that were a direct consequence of the pandemic. Support provided by healthcare organizations to their workers was an important coping response (French et al., 2018). Participants shared their experiences of using psychological support, counselling, a well-being hub, which is free, safe, and a confidential space that provides mental health support and advice to HCWs, and healthy eating provided by the healthcare organization. This enabled participants to cope with the impact of COVID-19 on their physical health as well as mental health.

… I think working in the critical care unit there was a group of us … medical students who were all from sort of the same background and we had like once a week psychology support. (Unknown sex, doctor)

They are doing their best on protecting, and a lot of effort is being done, and a lot of support … There is a line that for support if you need any, like, psychological support there, the line available, you can have a chat if you have experienced any difficulties, any kind of difficulties, you can discuss, there is a supervisor who is very helpful, they can support you in many ways. (Male, doctor)

I think at our workplace we had this team … made sure that they provided meals for us throughout that period, so we didn’t have to go anywhere … They brought everything … we were kind of spoilt … so that was helpful. They also provided a room … for staff wellbeing … so if any staff felt stressed, they know that they could go there. (Male, doctor)

3.2.5. Coping strategy outcomes

While the participants discussed the short-term benefits of the coping strategies explored in this data analysis, the long-term benefits are not known. The long-term impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the physical health and mental health of migrant HCWs needs to be explored.

My manager … referred me to this counselling service, which actually really helped, this counselling service for staff, they were very approachable. (Female, pharmacist)

At the end of the night my wife said ‘OK, let’s pray’ and then the next day I’m fine and then the cycle happens every time. Yeah, I’m just so grateful that I have such wonderful family support and of course my belief in God really helped me go through this pandemic. (Male, nurse)

I realized in the pandemic that when I'm doing a bit of gardening it takes me away actually from all of it – I totally forget where I am or the situation that I'm in – and that has been my coping mechanism even to date. (Male, doctor)

When I'm doing jigsaw puzzle I'm not thinking about anything than the puzzle itself. (Unknown gender, administration/non-clinical)

The use of coping strategies enabled these participants to focus on something else rather than dwelling on the reality of the COVID-19 pandemic, and these strategies are known to facilitate general well-being (Margaret et al., 2018). Further research is required to determine whether these short-term coping strategies and outcomes have had an impact on HCWs’ physical health and mental health post-pandemic.

4. Discussion

COVID-19 was a novel disease during the first wave because little was known about how to treat the disease. In addition, people had very limited coping strategies in response to COVID-19 itself. We undertook a qualitative secondary study analysis of HCWs in the UK from diverse migrant backgrounds. In this analysis, we explored participants’ coping strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic. We found that the participants used various strategies to cope with COVID-19 and its consequences, such as guilt, trauma, stress, and anxiety (Qureshi et al., 2022). Using the framework presented by Lazarus and Folkman, 1984, we showed how the participants identified the stressors, critically appraised the situation, and then used available resources to preserve their mental health and well-being. Mental health and physical health challenges were a direct consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic (George et al., 2020), irrespective of people's roles within the NHS.

The participants’ realist perspective of dealing with the pandemic was evident in the data, as they recognized and accepted the true nature and impact of COVID-19 on their physical and mental health and tried to deal with it in the most practical ways possible. Their lived experiences were not a social construction created and adopted based on theories; rather, their experiences convey the existence of a real-world crisis that had a global impact on mental well-being irrespective of perception (Maxwell, 2023). The importance of social connections in times of adversity (Nitschke et al., 2020) was evident from this study, as HCWs reported that the level of support received from family, friends, colleagues, and managers served as a buffer against mental health outcomes such as stress and anxiety. Qureshi et al. (2022) highlighted that HCWs lived with the guilt of potentially infecting loved ones with COVID-19. However, this indicates a significant dilemma considering that this paper highlights support from friends and family as an important emotion-focused coping strategy.

In addition, HCWs experienced increased levels of anxiety due to inconsistent protocols and policy, fear of infection, and trauma due to increased exposure to severe illness and death (Qureshi et al., 2022). The theme in this study relates to the theme highlighted by Qureshi et al. (2022) because the participants used emotion-focused coping, such as religion, family, and social support networks, as an essential coping mechanism. Furthermore, stress due to longer working hours and increased workload (Qureshi et al., 2022) was a challenge to HCWs during the COVID-19 pandemic. Using problem-focused coping as highlighted in this paper was a way of mitigating the impact of COVID-19 consequences on their mental health. HCWs used personal strategies (support from family and friends, support at work, voluntary work, faith in God, prayer, fellowship, starting a business, exercise, playing games, psychological support, counselling, well-being hubs, and healthy eating) to deal with the consequences of the pandemic, which then enabled them to alter and shift their focus away from the reality (Carroll, 2020).

In addition, the participants engaged with support provided by their employers, and there is evidence that workplace mental health needs can be better managed by an integrated approach that aims to prevent harm, promote a positive working environment, and manage illness (LaMontagne et al., 2014). Having professional support was a lifeline to these HCWs. With these resources at their disposal, they were able to seek help and support to address their mental health needs and promote well-being. There is an indication that seeking support can increase someone’s ability to cope, as well as build the ability to be resilient (Van der Hallen et al., 2020). Participants systematically planned and used these coping strategies to survive the pressure of the COVID-19 pandemic and to find a resolution for their concerns (Kepner-Tregoe, 2023).

This secondary study analysis reiterates the benefits of recreational activities in reducing stress (Weng & Chiang, 2014). Participants reported that exercising helped to shift their focus from the impact of COVID-19, reducing their levels of anxiety and stress. This result supports the findings of Litwiller et al. (2017), who suggest that recreational activities can facilitate mental health recovery. What was evident from this analysis was that the participants tried new activities to mitigate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. What is not evident in the discussions is whether they have retained these behaviours post-pandemic and whether any negative coping mechanisms, such as illicit drug use or excessive alcohol consumption, were utilized.

Religion can play an important part in a person’s life (Stibich, 2022), and evidence suggests that the human brain may find comfort in chaotic circumstances through religion (American Psychological Association, 2010). The participants talked about their religious beliefs and how their faith gave them reassurance and a sense of security. Some HCWs described finding their faith and deepening their trust in God during this time. Having religious faith was not specific to a particular gender, ethnicity, or profession; it cut across all groups in these study participants. Previous research has found that there is a positive association between faith and health, including mental health, and coping strategies developed to maintain well-being (Bunn & Randall, 2011; Koenig et al., 2001; Najah et al., 2017; Peneycad et al., 2024).

The COVID-19 pandemic lockdown had its positives in the sense that some participants were able to spend more time with their family members, through remote video calls, sharing a playlist, exercising together, or even doing voluntary work together, which many found to be beneficial to their mental health and well-being. Khan et al. (2021) also reported the positive impact of the COVID-19 pandemic despite its negative consequences on public health. In addition, undertaking entrepreneurial endeavours has the potential to create a sense of achievement and meaningfulness essential for well-being (Munoz & Barton, 2024). Although one participant reported that starting a business was beneficial to their mental health, it is not known whether there is a positive correlation between entrepreneurship and mental well-being (Pradana et al., 2023).

There is a clear indication from the data that the participants used various coping strategies to counterbalance the impact of the pandemic on their mental well-being (Molloy, 2012). Specific coping strategies, such as family and social support networks, religion, engaging in self-care, and professional support, emerged from the qualitative data. It is important to focus on these strategies in future research. It would be beneficial to identify how many of these personal strategies and professional services used for coping are still being used and made available to HCWs post-pandemic. Further research may be used to explore whether these coping strategies have been further developed, in order to provide personalized mental health care to HCWs and measure its implications for HCWs’ coping and resilience levels.

4.1. Strengths and limitations

A strength of this study is that the sample is diverse and represents diversity in ethnicity, age, gender, and job role. This study was designed to use both individual interviews and focus groups to enable the participants to share their coping strategies without focusing on positives or negatives. We acknowledge that the methods were not an ideal way to assess internal coping processes and unhelpful coping processes. This may limit the breadth of strategies considered to the more socially acceptable answers.

The main limitation of this study is that we only examined the coping strategies of migrant (non-UK-born) HCWs living in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic. Exploring the coping strategies of HCWs born in the UK would provide a different perspective, which may help to identify further strategies to counter the mental health challenges of an ethnically diverse healthcare workforce.

In addition, the HCWs taking part in this study may have been less open about sharing negative coping strategies owing to the perceived stigma associated with substance use and misuse, including alcohol consumption. However, we have tried to capture these data in the questionnaire study which is part of the wider UK-REACH project.

Furthermore, we did not use mental health measurement tools to assess changes in the mental health and well-being of the participants; therefore, we are unable to analyse the outcome of the coping strategies.

Some participants discussed benefiting from spending more time with their family during the lockdown; however, it is important to state that this may not reveal the true picture, as only 39 participants were included in this study analysis, which is small compared to the number of migrant HCWs living in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The authors identify researcher bias as a potential limitation; however, constant communication between researchers and active reflexivity is a strength of this study. The findings from the present study may not be generalizable to populations outside the UK.

5. Conclusion

We identified a variety of coping strategies used by migrant HCWs in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic to preserve their mental health and well-being. These included engaging in self-care, religious coping, family and social networks, and seeking and receiving professional support. Healthcare organizations should consider how they can use the findings from this study to enable their HCWs to engage in positive coping strategies in the future. The pressures placed on HCWs do not seem to be decreasing post-pandemic; therefore, it is even more important to build on what works for them to help safeguard their mental health in the future.

Supplementary Material

Funding Statement

MRC-UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) and the Department of Health and Social Care through the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) rapid response panel to tackle COVID-19 supported UK-REACH with a grant [MR/V027549/1]. Core funding was provided by NIHR Biomedical Research Centres. M. P. is funded by an NIHR Development and Skills Enhancement Award and receives support from the NIHR Leicester BRC and NIHR ARC East Midlands. L. B. N. is supported by the Academy of Medical Sciences [SBF005/1047]. This work is carried out with the support of BREATHE – the Health Data Research Hub for Respiratory Health [MC_PC_19004]. funded through the UK Research and Innovation Industrial Strategy Challenge Fund and delivered through Health Data Research UK.

Data availability

The UK-REACH data supporting this research are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Algorani, E. B., & Gupta, V. (2023). Coping mechanisms in: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559031/ [PubMed]

- American Psychological Association . (2010). A reason to believe. https://www.apa.org/monitor/2010/12/believe

- Baker, C. (2022). NHS staff from overseas: Statistics. House of Commons Library. https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-7783/CBP-7783.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Berjot, S., & Gillet, N. (2011). Stress and coping with discrimination and stigmatization. Frontiers in Psychology, 2, 33. 10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2023). Is thematic analysis used well in health psychology? A critical review of published research, with recommendations for quality practice and reporting. Health Psychology Review, 17(4), 695–718. 10.1080/17437199.2022.2161594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunn, A., & Randall, D. (2011). Health benefits of Christian faith. The Human Journey, CMF File, 44. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, L. (2020). Problem-focused coping. In Gellman M. D. (Ed.), Encyclopedia of behavioral medicine (pp. 1747–1748). Springer. 10.1007/978-3-030-39903-0_1171 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Che Yusof, R., Norhayati, M. N., & Azman, Y. M. (2022). Experiences, challenges, and coping strategies of frontline healthcare providers in response to the COVID-19 pandemic in Kelantan, Malaysia. Frontiers in Medicine, 9, 861052. 10.3389/fmed.2022.861052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Q., Liang, M., Li, Y., Guo, J., Fei, D., Wang, L., He, L., Sheng, C., Cai, Y., Li, X., Wang, J., & Zhang, Z. (2020). Mental health care for medical staff in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(4), 15–16. 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30078-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, C., Spiers, N., Livingston, G., Jenkins, R., Meltzer, H., Brugha, T., McManus, S., Weich, S., & Bebbington, P. (2013). Ethnic inequalities in the use of health services for common mental disorders in England. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 48(5), 685–692. 10.1007/s00127-012-0565-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diver, S., Buccheri, N., & Ohri, C. (2021). The value of healthcare worker support strategies to enhance wellbeing and optimise patient care. Future Healthcare Journal, 8(1), e60–e66. 10.7861/fhj.2020-0176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flinders, S. (2022). Mental health: We’re monitoring trends in the quality of mental health care. Quality watch. Indicator update. https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/news-item/mental-health-indicator-update? [Google Scholar]

- Francis, J. J., Johnston, M., Robertson, C., Glidewell, L., Entwistle, V., Eccles, M. P., & Grimshaw, J. M. (2009). What is an adequate sample size? Operationalising data saturation for theory-based interview studies. Psychology & Health, 25(10), 1229–1245. 10.1080/08870440903194015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French, K. A., Dumani, S., Allen, T. D., & Shockley, K. M. (2018). A meta-analysis of work–family conflict and social support. Psychological Bulletin, 144(3), 284–314. 10.1037/bul0000120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George, C. E., Inbaraj, L. R., Rajukutty, S., & de Witte, L. P. (2020). Challenges, experience and coping of health professionals in delivering healthcare in an urban slum in India during the first 40 days of COVID-19 crisis: A mixed method study. BMJ Open, 10, e042171. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill, P., Stewart, K., Treasure, E. & Chadwick, B. (2008). Methods of data collection in qualitative research: Interviews and focus groups. British Dental Journal, 204, 291–295. pmid:18356873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogoi, M., Berendt, R., Al-Oraibi, A., Reed-Berendt, R., Hassan, O., Wobi, F., Gupta, A., Abubakar, I., Dove, E., Nellums, L. B., & Pareek, M. (2021). Ethnicity and COVID-19 outcomes among healthcare workers in the UK: UK-REACH ethico-legal research, qualitative research on healthcare workers’ experiences and stakeholder engagement protocol. BMJ Open, 11(7), e049611. 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-049611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOV.UK . (2021). Ethnicity facts and figures. List of ethnic groups. https://www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk/style-guide/ethnic-groups/#2021-census

- Greenberg, N. (2022). Our moral obligation: supporting the mental wellbeing of healthcare workers. https://www.kcl.ac.uk/news/our-moral-obligation-supporting-the-mental-wellbeing-of-healthcare-workers#:~:text=The%20mental%20health%20burden%20is,traumatic%20stress%20disorder%20(PTSD)

- Greenberg, N., Weston, D., Hall, C., Caulfield, T., Williamson, V., & Fong, K. (2021). Mental health of staff working in intensive care during COVID-19. Occupational Medicine, 71(2), 62–67. 10.1093/occmed/kqaa220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halvorsrud, K., Nazroo, J., Otis, M., Brown Hajdukova, E., & Bhui, K. (2019). Ethnic inequalities in the incidence of diagnosis of severe mental illness in England: A systematic review and new meta-analyses for non-affective and affective psychoses. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 54(11), 1311–1323. 10.1007/s00127-019-01758-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennink, M., & Kaiser, B. N. (2022). Sample sizes for saturation in qualitative research: A systematic review of empirical tests. Social Science & Medicine, 292, 114523. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute for Government Analysis . (2021). Timeline of UK coronavirus lockdowns, March 2020 to March 2021. https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/sites/default/files/timeline-lockdown-web.pdf

- Johnson, J. L., Adkins, D., & Chauvin, S. (2020). A review of the quality indicators of rigor in qualitative research. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 84(1), 138–146. 10.5688/ajpe7120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kepner-Tregoe . (2023). The power of situation appraisal – beginnings. https://kepner-tregoe.com/community-post/the-power-of-situation-appraisal/#:~:text=Situation%20Appraisal%20is%20a%20rational,act%2C%20and%20we%20can

- Khan, I., Shah, D., & Shah, S. S. (2021). COVID-19 pandemic and its positive impacts on environment: An updated review. International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology, 18(2), 521–530. 10.1007/s13762-020-03021-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khasnabis, C., Heinicke Motsch K., Achu, K., Al Jubah, K., Brodtkorb, S., Chervin, P., Coleridge, P., Davies, M., Deepak, S., Eklindh, K., Goerdt, A., Greer, C., Heinicke-Motsch K., Hooper, D., Ilagan, V. B., Jessup, N., Khasnabis, C., Mulligan, D., Murray, … Lander, T. (Eds.). (2010). Community-based rehabilitation: CBR guidelines. World Health Organization; Recreation, Leisure and Sports. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK310922/. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig, H. G., McCullough, M. E., & Larson, D. B. (2001). Handbook of religion and health. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kupcova, I., Danisovic, L., Klein, M. & Harsanyi, S. (2023). Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health, anxiety, and depression. BMC Psychology, 11(1), 108. 10.1186/s40359-023-01130-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaMontagne, A. D., Martin, A., Page, K. M., Reavley, N. J., Noblet, A. J., Milner, A. J., Keegel, T., & Smith, P. M. (2014). Workplace mental health: Developing an integrated intervention approach. BMC Psychiatry, 14, 131. 10.1186/1471-244X-14-131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, R. J. (2007). Personality processes in encyclopedia of stress (2nd ed.). ScienceDirect. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Litwiller, F., White, C., Gallant, K. A., Gilbert, R., Hutchinson, S., Hamilton-Hinch, B., & Lauckner, H. (2017). The benefits of recreation for the recovery and social inclusion of individuals with mental illness: An integrative review. Leisure Sciences, 39(1), 1–19. 10.1080/01490400.2015.1120168 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maher, C., Hadfield, M., Hutchings, M., & de Eyto, A. (2018). Ensuring rigor in qualitative data analysis: A design research approach to coding combining NVivo with traditional material methods. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 17(1), 1–13. 10.1177/1609406918786362 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Margaret, K., Ngigi, S., & Mutisya, S. (2018). Sources of occupational stress and coping strategies among teachers in borstal institutions in Kenya. Edelweiss: Psychiatry Open Access, 2, 18–21. 10.33805/2638-8073.111 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell, J. A. (2023). A realist approach for mixed methods research. In Shan Y. (Ed.), Philosophical foundations of mixed methods research (1st ed., chapter 8, pp. 152–169). Imprint Routledge. eBook ISBN9781003273288. [Google Scholar]

- Molloy, M. A. (2012). Counterbalancing to compensate for physical, emotional, intellectual, or spiritual weaknesses. As meditation and prayer helps to counterbalance the emotional and the physical, it also helps to counterbalance the intellectual. HUFFPOST. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/counterbalancing_b_1898025

- Munoz, P., & Barton, M. (2024). MIND your business: Tackling the mental health crisis in entrepreneurship. Durham University Business School. https://www.durham.ac.uk/business/impact/entrepreneurship/mind-your-business-tackling-the-mental-health-crisis-in-entrepreneurship-/#:~:text=It%20offers%20extreme%20rewards%20and,of%20success%2C%20and%20personal%20development [Google Scholar]

- Najah, A., Farooq, A., & Rejeb, R. B. (2017). Role of religious beliefs and practices on the mental health of athletes with anterior cruciate ligament injury. Advances in Physical Education, 7(2), 181–190. 10.4236/ape.2017.72016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nitschke, J. P., Forbes, P. A. G., Ali, N., Cutler, J., Apps, M. A. J., Lockwood, P. L., & Lamm, C. (2020). Resilience during uncertainty? Greater social connectedness during COVID-19 lockdown is associated with reduced distress and fatigue. British Journal of Health Psychology, 26(2), 553–569. 10.1111/bjhp.12485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passmore, M. J. (2013). Neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia: Consent, quality of life, and dignity. BioMed Research International, 2013, 1–4. Article ID 230134. Retrieved February 26, 2015 from http://www.hindawi.com/journals/bmri/2013/230134/. 10.1155/2013/230134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peneycad, C., Ysseldyk, R., Tippins, E., & Anisman, H. (2024). Medicine for the soul: (Non)religious identity, coping, and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS One, 19(1), e0296436. 10.1371/journal.pone.0296436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradana, M., Elisa, H. P., & Utami, D. G. (2023). Mental health and entrepreneurship: A bibliometric study and literature review. Cogent Business & Management, 10(2), 1–12. 10.1080/23311975.2023.2224911 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Proto, E., & Quintana-Domeque, C. (2021). COVID-19 and mental health deterioration by ethnicity and gender in the UK. PLoS One, 16(1), e0244419. 10.1371/journal.pone.0244419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Queen Mary University of London . (2021). More than 1 in 4 healthcare workers seek mental health support during Covid. https://www.qmul.ac.uk/media/news/2021/smd/more-than-1-in-4-healthcare-workers-seek-mental-health-support-during-covid.html#:~:text=In%20September%202020%2C%20half%20of,ten%20(58%25)%20by%20January

- Qureshi, I., Gogoi, M., Al-Oraibi, A., Wobi, F., Chaloner, J., Gray, L., Guyatt, A. L., Hassan, O., Nellums, L. B., Pareek, M., & Group, U.-R. C. (2022). Factors influencing the mental health of an ethnically diverse healthcare workforce during COVID-19: A qualitative study in the United Kingdom. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 13(2), 2105577. 10.1080/20008066.2022.2105577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raypole, C., & Legg, T. J. (2020). 7 Emotion-focused coping techniques for uncertain times. Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/health/emotion-focused-coping

- Rees, C. E., Davis, C., Nguyen, V. N., Proctor, D., & Mattick, K. L. (2023). A roadmap to realist interviews in health professions education research: Recommendations based on a critical analysis. Medical Education, 58(6), 697–712. 10.1111/medu.15270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, J. P., Chesney, E., Oliver, D., Pollak, T. A., McGuire, P., Fusar-Poli, P., Zandi, M. S., Lewis, G., & David, A. S. (2020). Psychiatric and neuropsychiatric presentations associated with severe coronavirus infections: A systematic review and meta-analysis with comparison to the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(7), 611–627. pmid: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32437679. 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30203-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shechter, A., Diaz, F., Moise, N., Anstey, D. E., Ye, S., Agarwal, S., Birk, J. L., Brodie, D., Cannone, D. E., Chang, B., Claassen, J., Cornelius, T., Derby, L., Dong, M., Givens, R. C., Hochman, B., Homma, S., Kronish, I. M., Lee, S. A. J., … Abdalla, M. (2020). Psychological distress, coping behaviors, and preferences for support among New York healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. General Hospital Psychiatry, 66, 1–8. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2020.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, K., Bhui, K., & Cipriani, A. (2020). COVID-19, mental health and ethnic minorities. BMJ Ment Health, 23, 89–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Søvold, L. E., Naslund, J. A., Kousoulis, A. A., Saxena, S., Qoronfleh, M. W., Grobler, C., & Münter, L. (2021). Prioritizing the mental health and well-being of healthcare workers: An urgent global public health priority. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 2296–2565. 10.3389/fpubh.2021.679397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stibich, M. (2022). What is religion? The psychology of why people believe. Very Well Mind. https://www.verywellmind.com/religion-improves-health-2224007#citation-11

- TASO – Transforming Access and Student Outcomes in Higher Education . (2024). Realist evaluation. https://taso.org.uk/evidence/evaluation-guidance-resources/impact-evaluation-with-small-cohorts/getting-started-with-a-small-n-evaluation/realist-evaluation/#:~:text=Overview,is%20more%20likely%20to%20succeed

- Tinner, L., & Alonso Curbelo, A. (2024). Intersectional discrimination and mental health inequalities: A qualitative study of young women’s experiences in Scotland. International Journal for Equity in Health, 23(1), 45. 10.1186/s12939-024-02133-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tufford, L., & Newman, P. (2012). Bracketing in qualitative research. Qualitative Social Work, 11(1), 80–96. 10.1177/1473325010368316 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Hallen, R., Jongerling, J., & Godor, B. P. (2020). Coping and resilience in adults: A cross-sectional network analysis. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 33(5), 479–496. 10.1080/10615806.2020.1772969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng, P.-Y., & Chiang, Y.-C. (2014). Psychological restoration through indoor and outdoor leisure activities. Journal of Leisure Research, 46(2), 203–217. 10.1080/00222216.2014.11950320 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . (2020). Emergency. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. https://www.who.int/europe/emergencies/situations/COVID-19#:~:text=Cases%20of%20novel%20coronavirus%20(nCoV,pandemic%20on%2011%20March%202020

- World Health Organization . (2022). COVID-19 pandemic triggers 25% increase in prevalence of anxiety and depression worldwide. https://www.who.int/news/item/02-03-2022-covid-19-pandemic-triggers-25-increase-in-prevalence-of-anxiety-and-depression-worldwide

- Yusuf, A., Tristiana, R. D., Aditya, R. S., Solikhah, F. K., Kotijah, S., Razeeni, D. M. A., & Alkhaledi, E. M. (2024). Caregivers caring for mentally disordered patients during pandemic and lockdown: A qualitative approach. Environment and Social Psychology, 9(1), 1–13. 10.54517/esp.v9i1.1752 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zuzer Lal, Z., Martin, C. A., Gogoi, M., Qureshi, I., Bryant, L., Papineni, P., Lagrata, S., Nellums, L. B., Al-Oraibi, A., Chaloner, J., Woolf, K., & Pareek, M. (2024). Redeployment experiences of healthcare workers in the UK during COVID-19: Data from the nationwide UK-REACH study. medRxiv, 1–29. 10.1101/2024.03.03.24303615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The UK-REACH data supporting this research are available from the authors upon reasonable request.