Abstract

Background

Heart failure is a rare manifestation of metastatic disease of the carcinoma of an unknown primary, malignancy that requires extensive work-up to identify the primary site. Initial consideration of rare etiologies in patients presented with a common clinical syndrome is challenging.

Case presentation

A 35-year-old Black woman presented with shortness of breath at rest, orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, chest pain, a blood-tinged productive cough, and fever for 2 weeks. She also had progressive body swelling, easy fatigability, loss of appetite, and abdominal pain during the same week’s duration. Body imaging revealed large pleural and pericardial effusions, metastatic liver lesions, and bilateral pulmonary vascular segmental and subsegmental filling defects. Pericardial and pleural fluid cytology suggest malignant effusion. Liver lesions and core needle biopsy indicated adenocarcinoma of unknown origin, and the carcinoembryonic antigen level also increased significantly.

Conclusion

Carcinoma of unknown primary origin commonly presents in an advanced stage and is often accompanied by clinical features of site metastasis. This case highlights heart failure as an unusual first manifestation of adenocarcinoma with an unknown primary origin.

Keywords: Adenocarcinoma, Unknown primary, Heart failure

Background

Carcinoma of unknown primary (CUP) origin is a rare metastatic disease in which a primary tumor site cannot be identified [1]. CUP is characterized by a specific and unique phenotype of early and usually aggressive metastatic dissemination compared with other cancers [2]. They are heterogeneous neoplasms that continue to be a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge for physicians [3]. It is a diagnosis of exclusion after extensive work using various serum biomarker tests, imaging modalities, and histologic analysis [4]. The incidence of this diagnosis increases with age; most patients present with metastases involving at least two sites upon diagnosis [5]. The most common histological type was adenocarcinoma (70%), followed by poorly differentiated carcinoma (30%) [5, 6].

They commonly involve the lungs, pancreas, hepatobiliary tract, and kidney but they could also have an unpredictable metastatic pattern [7, 8]. CUP, like other metastatic carcinomas, involves the myocardium and pericardium is extremely rare [4]. The majority (over 90%) of cardiac secondary cancers remain clinically silent and are frequently identified in postmortem examination and CUP is not an exception [9]. Previously, a few case reports have been published that presented the cases of cardiac tamponade owing to CUP [10, 11]. This indicates that it is much more uncommon for heart failure to be the presenting feature of a hitherto undiagnosed cancer of unknown primary origin. We describe a case of heart failure with cardiac tamponade as the first manifestation of metastatic adenocarcinoma of unknown origin in a 50-year-old female patient who presented to our hospital with symptoms dominated by heart failure for about 2 weeks. Despite extensive searches of popular databases, such as PubMed, Google Scholar, and others, no case similar to ours has ever been reported or published. This rare etiology presenting with a common clinical syndrome, such as heart failure, might easily be overlooked, making diagnosis difficult and serving as a learning case for clinicians.

Case presentation

A 35-year-old female Ethiopian patient presented to Yekatitit 12 Hospital Medical College’s emergency department with complaints of shortness of breath at rest, orthopnoea, significant paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnoea, chest pain, a blood-tinged productive cough, and vomiting of ingested matter (2–3 episodes per day) for 2 weeks. She had progressive body swelling that started in the lower extremities and later involved the whole body, easy fatigability, a loss of appetite, a high-grade intermittent fever, and an epigastric burning sensation for the same duration for the same duration of the same week. The patient also experienced an unspecified amount of weight loss and fatigue for the past 2 months. Otherwise, she had no known comorbidities, no risky behavior, such as smoking or alcohol drinking, medications, or a family history of malignancy. She was married, had four children, and had no bad obstetrics history. Her occupation was farming, and she had been living in a rural area. She had never been admitted for a similar complaint.

The patient’s Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) was 15 out of 15, and there were no memory, power, or tone abnormalities. The patient was in severe respiratory distress with oxygen saturation of 70% with atmospheric air, respiratory rate of 30–35 beats/minute, and pulse rate of 120 per minute. She had high-grade fever records up to the level of 39.5 0C and can maintain her blood pressure. The breast examination with ultrasound and mammography was reportedly normal. Lymphadenopathy was not detected in reachable areas.

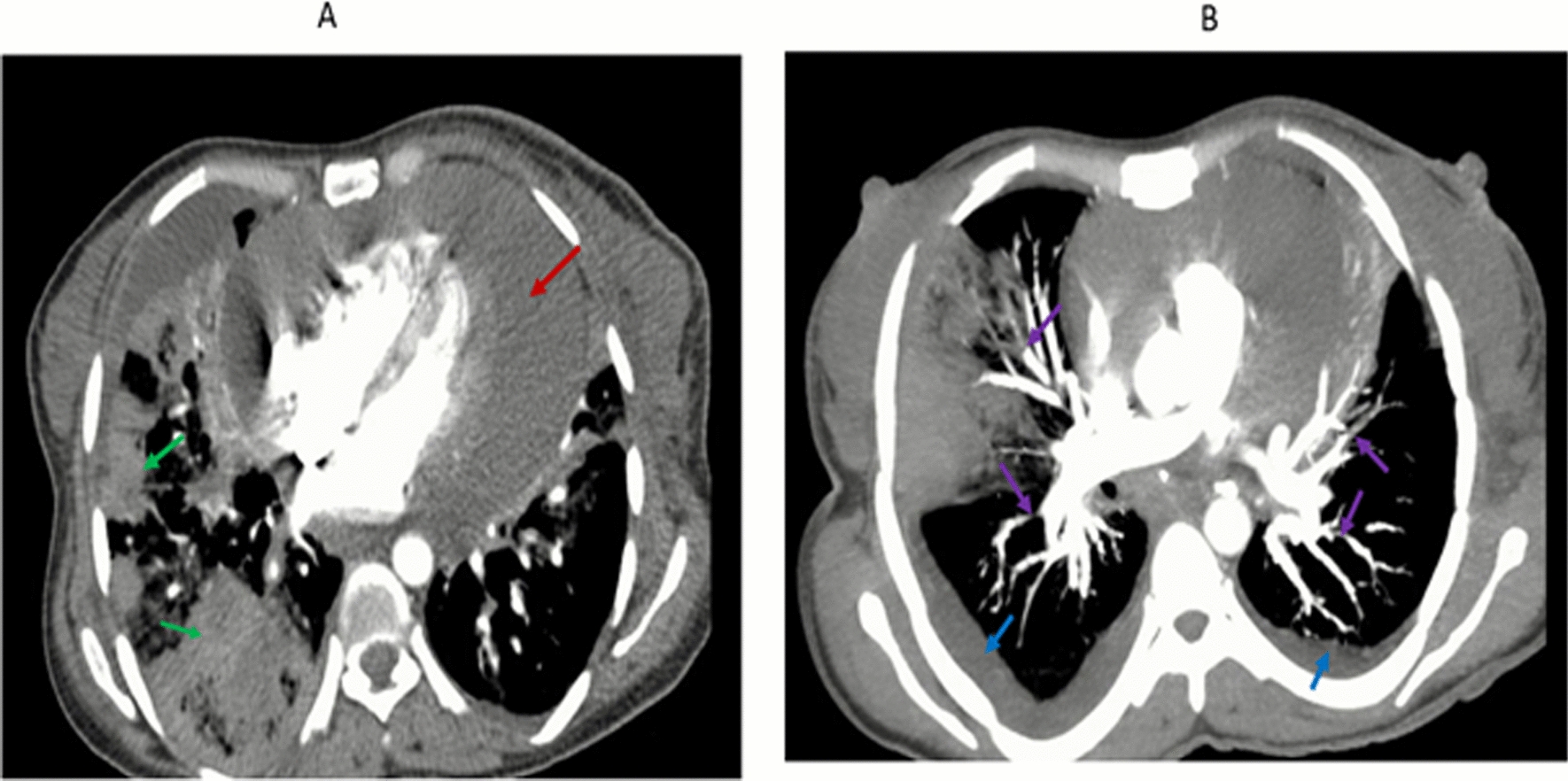

The chest examination revealed signs of pleural effusion that were also revealed in the imaging and were analyzed. A chest computed tomography (CT) with contrast showed pericardial effusion (Fig. 1A) and multifocal pneumonia (Fig. 1B). CT angiography showed a lower lobe segmental pulmonary arterial filling defect on both sides, which suggests pulmonary emboli (Fig. 1B) and pleural effusion on both sides (Fig. 1B). The cytologic smears were reported with sheets of mesothelial cells, neutrophils, and scattered single clusters of large atypical cells with prominent nucleoli suggestive of malignant effusion. The plural fluid analysis had lymphocytic predominant fluid with normal glucose (82 mg/dl), protein (2.2 g/dl), and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) of 592 mg/dl.

Fig. 1.

A and B Computed tomography scan showing pericardial effusion (A, red arrow), consolidation (B, green arrow), bilateral filling defect (B, purple arrow), and bilateral pleural effusion (B, blue arrow)

Jugular venous pressure was raised by muffled heart sounds. The echocardiography showed massive pericardial effusion with cardiac tamponade features, preserved ejection fraction (EF 65%), and tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE) greater than 18 mm. An electrocardiogram (ECG) revealed only sinus tachycardia and axis deviation (Fig. 2). An immediate pericardiocentesis was done, a drain of about 250 ml of hemorrhagic fluid was removed, and the pericardial window was secured. Repeated echocardiography imaging revealed a size reduction. The cytology report from the pericardial fluid had numerous lymphocytes together with atypical malignant cells having prominent nucleoli suggestive of malignant effusion.

Fig. 2.

Electrocardiogram revealed right axis deviation with tachycardia

On the abdominal examination, she had positive signs of fluid collection with no ballotable organ. The abdominopelvic CT scan showed an increment in the size of the liver with multiple hypointense hepatic lesions suggestive of metastasis (Fig. 3). The pelvic organs, including the ovaries and uterus, had no identified lesions. A core needle biopsy was performed on the liver lesion, and the results revealed secondary adenocarcinoma.

Fig. 3.

The abdominopelvic computed tomography scan revealed an increased liver size, reduced attenuation, and multiple hypodense hepatic lesions with minimal enhancement lesions (blue arrows), suggesting metastasis

A diagnosis of heart failure caused by malignant massive pericardial effusion secondary to disseminated adenocarcinoma and carcinoma of unknown primary origin involving the lung, pleura, pericardium, and gastrointestinal tract was made. The patient was diagnosed with left upper exterminate extensive deep vein, bilateral segmental pulmonary embolism possible owing to the disseminated CUP. The findings also showed superimposed multifocal pneumonia and mild anemia of chronic disease.

The initial complete blood cell count revealed leucocytosis with a white blood cell count of 24 × 103 per mL, neutrophil predominant (91%), red blood cell count of 3.7 × 106 per µL, mild normocytic anemia [hemoglobin (Hgb) 11.2 mg/dl], mean corpuscular volume (MCV) of 81.2 fl, and severe thrombocytopenia (66 × 103/µL). After antibiotic treatment for pneumonia, the total blood cell count returned to normal (except for Hgb). With normal bilirubin levels, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) increased by more than seven times (263 U/L), while Alanine transaminase (ALT) increased by more than nine times (332 U/L). Serum electrolytes (except for Na + with mild hyponatremia, 129 mEq/L) and renal function tests were normal. Albumin was low (2.12 g/dl). Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels increased almost twofold from the baseline (592 U/L). The human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C viruses were not reactive. Blood and culture of pleural fluid had no growth. A carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) increased over 400 times (1000 µg/L) of the baseline.

The patient was admitted to the general ward. A pericardial window and right-side chest tube insertion were done with a cardiothoracic surgeon along with a cardiologist (see the amount aspirated above). Intermittent therapeutic pleural aspiration was done for the malignant pleural effusion. Once the loading dose (60 mg) of frusemide produced sufficient urine output, this dose was maintained three times (TID) a day. This was then de-escalated, and she was discharged with an oral dose of 20 mg twice a day (BID). A standard dose of enoxaparin was started for pulmonary thromboembolism and left upper extremity acute extensive deep vein thrombosis. Enoxaparin at 40 mg subcutaneous BID was given during hospitalization, which was changed to 5 mg of oral warfarin daily during discharge because of financial issues. The multifocal pneumonia was treated with ceftazidime (1 gm intravenously TID) and vancomycin (1 gm intravenously BID) as per the national standard treatment protocol. The pain was controlled by a potent anti-pain medication (morphine 5 mg intravenously TID) and deescalated and discontinued. She was also on ulcer prophylaxis. The patient was discharged from the medical ward with significant improvement after 14 days of hospitalization and appointed to the oncology unit of the hospital. Thus, for cancer of unknown primary origin, she was given one cycle of chemotherapy (carboplatin/paclitaxel). She was lost on follow-up owing to financial issues, and the patient died at home within 4 months of discharge.

Discussion

This report details a middle-aged woman’s case of adenocarcinoma of unknown primary cause that initially presented with symptoms of heart failure superimposed with a chest infection. The patient was evaluated with CT scans of the abdomen and chest, echocardiography, pleura and pericardium body fluid analyses, a core needle biopsy of the liver lesion, and additional laboratory testing.

CUP metastasis occurs most commonly in solid organ sites, such as the lungs, pancreas, hepatobiliary tract, and kidneys [12]. Cardiac metastases are usually silent, though they can cause pericardial effusion with or without tamponade, heart failure or valve dysfunction, and systemic or pulmonary embolism [13]. Since malignant pericardial effusion is gradually growing, heart failure with hemodynamic instability owing to cardiac tamponade is the rare presenting symptom for individuals with CUP [14]. Previously, few cases have been published that present cardiac tamponade as the first manifestation of cancer with no identified primary [10, 11]. In our case, the patient presented with heart failure symptoms with cardiac tamponade in a patient with adenocarcinoma of unknown primary.

Individuals with cancer, including CUP, are at a greater risk of multiple cardiovascular disease subtypes and mortality from cardiovascular disease [13]. It might be related to shared mechanisms underlying both cardiovascular disease and cancer, including chronic inflammation, oxidative stress, metabolic dysregulation, clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential, microbial dysbiosis, hormonal effects, cell senescence, and mechanical complication [15]. Some antineoplastic medications are cardiotoxic and induce cardiovascular disease, although this is not a likely mechanism, as our patient had heart failure signs before starting antineoplastic treatment for CUP [16]. Furthermore, the cancer patient might present with heart failure owing to pulmonary vascular thromboembolic problems, which are common in all cancer patients [17]. Our patient had severe bilateral subsegmental pulmonary emboli; however, there was no echocardiographic evidence of right heart failure as a result of the pulmonary embolism. The particular mechanism by which CUP causes heart failure is unknown; however, it might be attributable to a complication caused by the CUP or the cancer itself.

A diagnosis of cancer of unknown primary origin occurs when metastatic cancer has been found but the primary site cannot be identified, despite extensive imaging, clinical assessment, and pathological investigation [8]. In addition, in patients presenting with metastatic symptoms dominated by specific system presentation, the diagnosis of CUP is only considered late in the diagnostic process. In our case, the patients presented mainly with heart failure symptoms, while the common cause of heart failure was initially considered. More importantly, after CUP consideration, the diagnosis of CUP challenges in resource-limited countries, including Ethiopia, owing to the cost, availability of diagnostic modalities, and human expertise. In our patients, despite trying to conduct CT imaging of the abdomen and chest, echocardiographic imaging, body fluid analysis, biopsy, and limited cancer marking, we could not identify the primary site. Similar to many other reports indicating that 70% of the CUP is adenocarcinoma histologically [12], the core needle biopsy of the liver lesion in our patient showed adenocarcinoma of unknown origin.

The definitive management of heart failure with pericardial tamponade is treating CUP. However, the survival rate of CUP is low (15–20%) using standard regimens consisting of platinum and taxane or platinum and gemcitabine. In our case, the patient was started with carboplatin/paclitaxel for CUP [17]. Malignant pericardial effusion sufficient to require drainage is a poor prognostic factor, with a reported median survival of 6.1 months [17, 18]. A pericardial window is the management of choice to prevent pericardial fluid from reaccumulating following the removal of a pericardiocentesis drain. In our patient, the pericardial window was done by the cardiothoracic surgeon along with the cardiologist, and the effusion had significant accumulation.

Conclusion

Common clinical syndromes, such as heart failure, might be the first to present symptoms of a rare neoplastic disorder, such as cancer of unknown origin. This case depicts heart failure with cardiac tamponade as the initial manifestation of cancer of unknown primary origin in a young, reproductive-age Ethiopian woman. Consideration of uncommon neoplastic disorders as the etiology for common clinical symptoms might help in early detection and treatment.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to the patient for giving consent to publish this case report.

Author contributions

AS, MR, HT, YG, GS, AZ, and ZA took responsibility for the construction of the body of the manuscript; BF, ET, KM, HRR, and BA organized and supervised the course of the project; BA reviewed the article before submission for its intellectual content.

Funding

There is no source of funding for this study.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing does not apply to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval is deemed unnecessary by Yekatit 12 Hospital Medical College Board as this is a single rare case faced during clinical practice.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing of interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ren M, Cai X, Jia L, et al. Comprehensive analysis of cancer of unknown primary and recommendation of a histological and immunohistochemical diagnostic strategy from China. BMC Cancer. 2023;23:1–10. 10.1186/S12885-023-11563-1/FIGURES/3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pavlidis N, Fizazi K. Carcinoma of unknown primary (CUP). Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2009;69:271–8. 10.1016/J.CRITREVONC.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kolling S, Ventre F, Geuna E, et al. “Metastatic cancer of unknown primary” or “primary metastatic cancer”? Front Oncol. 2020;9: 509161. 10.3389/FONC.2019.01546/BIBTEX. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oien KA, Dennis JL. Diagnostic work-up of carcinoma of unknown primary: from immunohistochemistry to molecular profiling. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:x271–7. 10.1093/annonc/mds357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hainsworth JD, Greco FA. Adenocarcinoma of unknown primary site. 2003.

- 6.Pentheroudakis G, Golfinopoulos V, Pavlidis N. Switching benchmarks in cancer of unknown primary: from autopsy to microarray. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43:2026–36. 10.1016/J.EJCA.2007.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yi JH, La Choi Y, Lee SJ, et al. Clinical presentation of carcinoma of unknown primary: 14 years of experience. Tumor Biol. 2011;32:45–51. 10.1007/S13277-010-0089-6/METRICS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Massard C, Loriot Y, Fizazi K. Carcinomas of an unknown primary origin—diagnosis and treatment. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2011;8:701–10. 10.1038/nrclinonc.2011.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al-Mamgani A, Baartman L, Baaijens M, et al. Cardiac metastases. Int J Clin Oncol. 2008;13:369–72. 10.1007/S10147-007-0749-8/METRICS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vlachostergios P. Basic concepts in metastatic cardiac disease. Cardiol Res. 2012. 10.4021/cr155w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cardiac tamponade as the first sign of malignancy: a case report—clinical oncology journal (ISSN 2766–9882). 2024. https://clinicaloncologyjournal.com/article/1000274/cardiac-tamponade-as-the-first-sign-of-malignancy-a-case-report. Accessed 25 May 2024.

- 12.Huntsman WT, Brown ML, Albala DM. Cardiac tamponade as an unusual presentation of lung cancer: case report and review of the literature. Clin Cardiol. 1991;14:529–32. 10.1002/CLC.4960140614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Boer RA, Meijers WC, van der Meer P, et al. Cancer and heart disease: associations and relations. Eur J Heart Fail. 2019;21:1515–25. 10.1002/EJHF.1539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilcox NS, Amit U, Reibel JB, et al. Cardiovascular disease and cancer: shared risk factors and mechanisms. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2024;2024:1–15. 10.1038/s41569-024-01017-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morelli MB, Bongiovanni C, Da Pra S, et al. Cardiotoxicity of anticancer drugs: molecular mechanisms and strategies for cardioprotection. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9: 847012. 10.3389/FCVM.2022.847012/BIBTEX. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tirandi A, Preda A, Carbone F, et al. Pulmonary embolism in patients with cancer: an updated and operative guide for diagnosis and management. Int J Cardiol. 2022;358:95–102. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2022.04.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yoon HH, Foster NR, Meyers JP, et al. Gene expression profiling identifies responsive patients with cancer of unknown primary treated with carboplatin, paclitaxel, and everolimus: NCCTG N0871 (alliance). Ann Oncol. 2016;27:339–44. 10.1093/annonc/mdv543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yonemori K, Kunitoh H, Tsuta K, et al. Prognostic factors for malignant pericardial effusion treated by pericardial drainage in solid-malignancy patients. Med Oncol. 2007;24:425–30. 10.1007/S12032-007-0033-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing does not apply to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.