Abstract

The basal ganglia are a group of interconnected subcortical nuclei that plays a key role in multiple motor and cognitive processes, in a close interplay with several cortical regions. Two conflicting theories postulate that the basal ganglia pathways can either foster or suppress the cortico–striatal output or, alternatively, they can stabilize or destabilize the cortico–striatal circuit dynamics. These different approaches significantly impact the understanding of observable behaviours and cognitive processes in healthy, as well as clinical populations. We investigated the predictions of these models in healthy participants (N = 28), using dynamic causal modeling of fMRI BOLD activity to estimate time- and context-dependent changes in the indirect pathway effective connectivity, in association with repetitions or changes of choice selections. We used two multi-option tasks that required the participants to adapt to uncontrollable environmental changes, by performing sequential choice selections, with and without value-based feedbacks. We found that, irrespective of the task, the trials that were characterized by changes in choice selections (switch trials) were associated with a neural response that mostly overlapped with a network commonly described for the encoding of uncertainty. More interestingly, dynamic causal modeling and family-wise model comparison identified with high likelihood a directed causal relation from the external to the internal part of the globus pallidus (i.e., the short indirect pathway in the basal ganglia), in association with the switch trials. This finding supports the hypothesis that the short indirect pathway in the basal ganglia drives instability in the network dynamics, resulting in changes in choice selection.

Keywords: basal ganglia, decision making, dynamic causal modeling, effective connectivity, globus pallidus, motor flexibility

1 |. INTRODUCTION

The basal ganglia consist in a group of interconnected subcortical nuclei that form a series of parallel circuits with motor, associative and limbic cortical regions, affecting motor as well as cognitive processes, in healthy and in clinical populations (Alexander et al., 1986; Maia & Frank, 2011; Obeso et al., 2014). A long history of studying the architecture of the basal ganglia has revealed multiple converging pathways in this neural system (Albin et al., 1989; Alexander & Crutcher, 1990; Alexander et al., 1986; DeLong, 1983, 1990). Initially, these pathways were assumed to compete against one another to control the output of the circuit (Alexander, 1994; Frank et al., 2004; Gurney et al., 2001a, 2001b). The pro-kinetic direct pathway, involving neurons in the striatum enriched with D1 dopamine receptors and globus pallidus pars interna (GPi), putatively responsible for vigour and action initiation and promotion, was assumed to compete with the anti-kinetic indirect pathway, involving D2-enriched striatum, globus pallidus pars externa (GPe), subthalamic nucleus (STN), and GPi, hypothesized to control (Gurney et al., 2001a; 2001b; Humphries et al., 2006) or suppress motor activity (Brown et al., 2004; Frank et al., 2004; Mink, 1996). However, in-depth analysis of fast basal ganglia dynamics (Bevan et al., 2002; McCarthy et al., 2011) and of the intrinsic connectivity of this circuit (Mallet et al., 2012; Suryanarayana et al., 2019) has revealed a higher degree of complexity than previously thought (Klaus et al., 2019; Nelson & Kreitzer, 2014; Rubin, 2017), thus vastly expanding the functions ascribed to the basal ganglia circuit as a whole (Obeso et al., 2014).

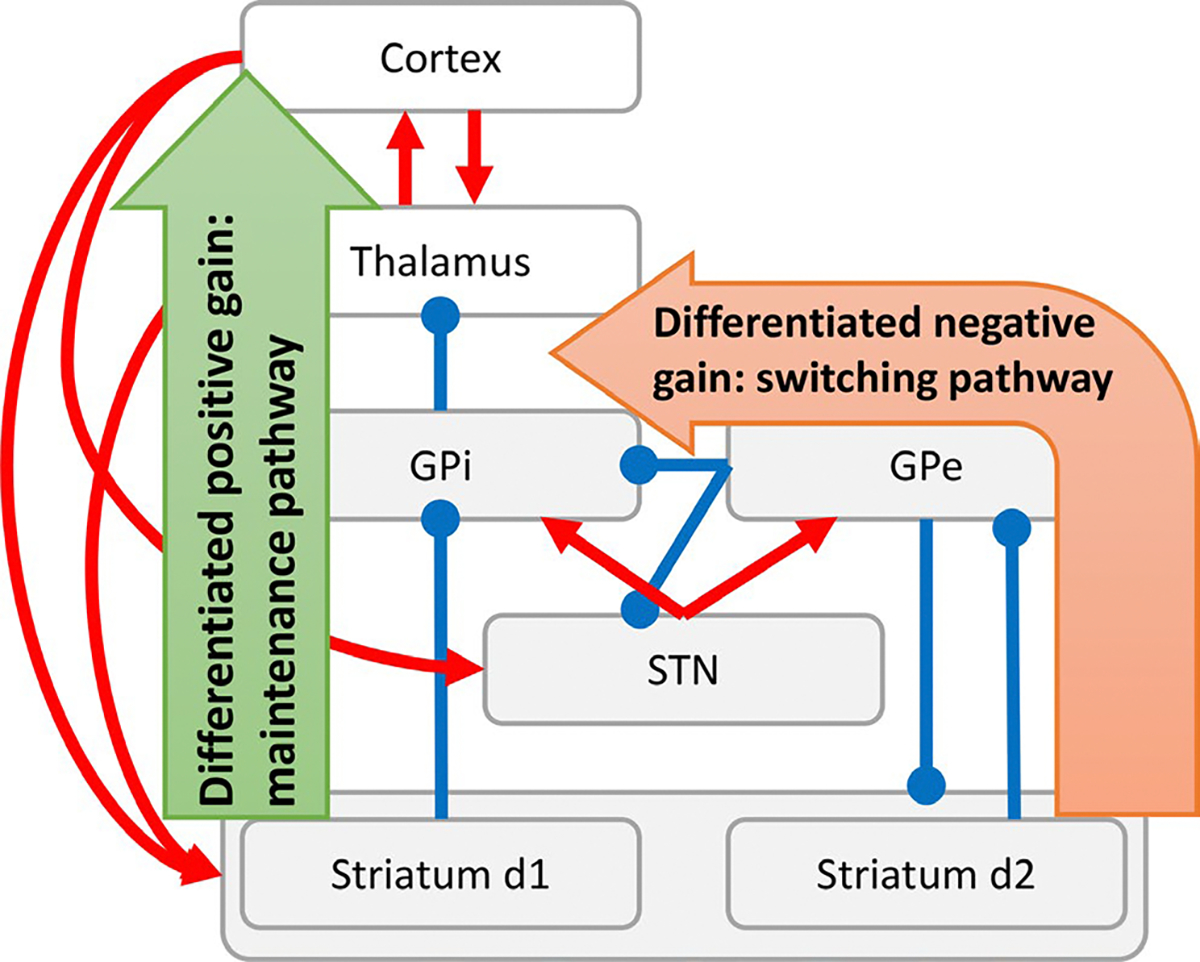

Lately, increasing attention has been paid to the connectivity – and as a consequence to the functions – of the GPe (Bogacz et al., 2016; Gittis et al., 2014; Hegeman et al., 2016; Suryanarayana et al., 2019), due to its direct projections towards all nuclei of the basal ganglia: striatum, GPi and STN (Abdi et al., 2015; Mallet et al., 2012; Mastro et al., 2014). This connectivity makes of the GPe a key node in both short and long indirect pathways (respectively referring to the striatum-GPe-GPi and the striatum-GPe-STN-GPi connectivity; Figure 1), while also interfering with the hyperdirect pathway, which conveys cortical activity to the output nuclei of the basal ganglia, via the STN. Consistently, the GPe function has been also subject of recent scrutiny, after a series of ground-breaking studies have challenged the anti-kinetic hypothesis for the indirect pathways (Jin et al., 2014; Nonomura et al., 2018; Tecuapetla et al., 2014, 2016; Vicente et al., 2016; Yttri & Dudman, 2016).

FIGURE 1.

Basal Ganglia structure and functioning. Illustrative representation of the basal ganglia structure, displaying the architecture of the pathways and their neural components (GPi: globus pallidus pars interna; GPe: globus pallidus pars externa; STN: sub-thalamic nucleus). The diagram highlights in particular the effect on circuit gain of the direct pathway (differentiated positive gain) and the short indirect pathway (differentiated negative gain), hypothesized to be responsible for stabilizing and destabilizing state transitions, respectively

To account for these findings, several theoretical and computational efforts have been made (Klaus et al., 2019; Rubin, 2017). Critically relevant to the purpose of the present investigation, it has been proposed in previous studies (Fiore et al., 2016; Hauser et al., 2016; Schroll et al., 2012; Trapp et al., 2012) that the basal ganglia functions can be understood in terms of the stability of state transitions they determine in the entire cortico–thalamo–striatal circuit. Since state transitions represent changes in network configurations (i.e., attractors), which are associated with the expression of a behaviour (e.g., a choice selection), this perspective suggests that behaviour stability or instability, rather than behaviour suppression or facilitation, is determined by the basal ganglia dynamics. Briefly, this model suggests that the channel-based organization of the Basal Ganglia results in an information conflict in the GPi between the differentiated information conveyed by the striatum and the differentiated information mediated by the GPe and the short indirect pathway (Fiore et al., 2018). If the conflict favours the former, input signal differences are enhanced, in a winner-take-all competition that results in the generation of steep attractors and noise-resistant processing of incoming stimuli (i.e., stability in choice selections is maintained for a prolonged time). If the conflict favours the latter, signal differences are compressed, resulting in equally valued or inverted information, driving the generation of shallow attractors and noise-driven processing of incoming stimuli or even oscillations (i.e., choice selections are unstable and easily changed randomly or in a pattern). Thus, increased effective connectivity (i.e., directed influence) in the direct pathway is expected to promote stability in state transitions [noise-resistant winnerless competitions (Afraimovich et al., 2008) or hyperstable dynamics], whereas increased effective connectivity in the (short) indirect pathway is expected to promote instability (fast meta-stable dynamics and pattern generation). In Marr’s terms (Marr & Poggio, 1976), this hypothesis can be considered as the implementation level for a computational level which assumes the basal ganglia compute a distribution of probabilities among available options (Bogacz & Gurney, 2007; Bogacz & Larsen, 2011). Thus, at the computational level, the direct pathway can be interpreted as narrowing a distribution of probabilities to few or even a single option, whereas the indirect pathway, within a range of effective connectivity configurations (cf. Fiore et al., 2016), would widen this distribution to include multiple alternatives with similar probabilities (Adams et al., 2020; Hauser et al., 2016).

In the present study, we aimed at testing the diverging predictions provided by the pro-kinetic/anti-kinetic model and the alternative stability/instability model, by directly investigating GPe-GPi effective connectivity during changes or repetitions in choice selections, in 28 healthy volunteers. Indeed, despite the detailed characterization of the asymmetrical relation in the anatomical connectome of the GP, the context-dependent directed influence characterizing the GP remains to be determined. To shed a light on these dynamics, we relied on two multi-option decision-making fMRI tasks (Churchland et al., 2008; Tajima et al., 2019) and dynamic causal modeling (DCM; Friston et al., 2003; Stephan et al., 2010) of fMRI BOLD signals. This method was used to estimate, within a specified model space, the time- and activity-dependent directed influence -or effective connectivity- that either GP region exerted over the other (Friston, 2011; Stephan et al., 2010). More precisely, the information flow exchanged directly or indirectly among the two GP parts was investigated in association with either changes or repetitions of choice selections, triggered by the information available in each task.

2 |. MATERIAL AND METHODS

2.1 |. Participants

28 healthy volunteers (16 females; age 24.8 ± 7.0 years) were recruited from the Dallas-Fort Worth (USA) metropolitan area for this study. Participants were excluded from the study if they were taking any psychotropic medication, or had any history of mental disorder or drug abuse. For one of the two tasks, termed card task, one subject was excluded (limited to the MRI-related analysis) due to excessive movement. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Texas, Dallas and the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects and all participants were informed that they could withdraw from the study at any point.

2.2 |. Three-options continuous choice tasks

The bead task (Huq et al., 1988; Figure 2a) was structured in 213 trials divided into three blocks (71 trials per block) and consisted in the presentation of a new coloured bead each trial (red, blue or green), to form a sequence. Participants were instructed that the sequence was determined by the computer, which would extract each bead from one of three jars displayed on screen as containing beads of the three colours in a ratio of 80%:10%:10%. The participants were instructed that the computer would not change the extraction jar every single trial, and it would instead extract beads from the same jar for an unspecified number of trials, before moving to the next. At the beginning of each trial, before revealing a new extracted bead, a grey square would appear to hide the new stimulus for a variable time (2–3.5 s), resulting in a variable inter-trial interval (ITI). After the grey square disappeared and the new bead was revealed, the participants were given 2 s to guess from which of the three jars the latest bead had been extracted. The selected jar would then be highlighted, for a varying time determined by the reaction time (i.e., 2 s minus the reaction time), plus 0.5 s, so that the total duration of the task would not be determined by the behaviour of the participants. The participants started performing their choices at the fifth extraction and the previous four extracted beads in the sequence were always present on screen (Figure 2a). In an initial session of training, participants received immediate deterministic feedback after each selection, but no feedback was provided during the actual MRI task. The training was meant to highlight that a new extracted bead of a different colour was not always associated with a change in the extraction jar, discouraging the use of a simple trial-by-trial colour response selection strategy. Each correct guess was awarded 100 points and the accumulated points of one randomly selected session were used to determine a final compensation (500 points=$1).

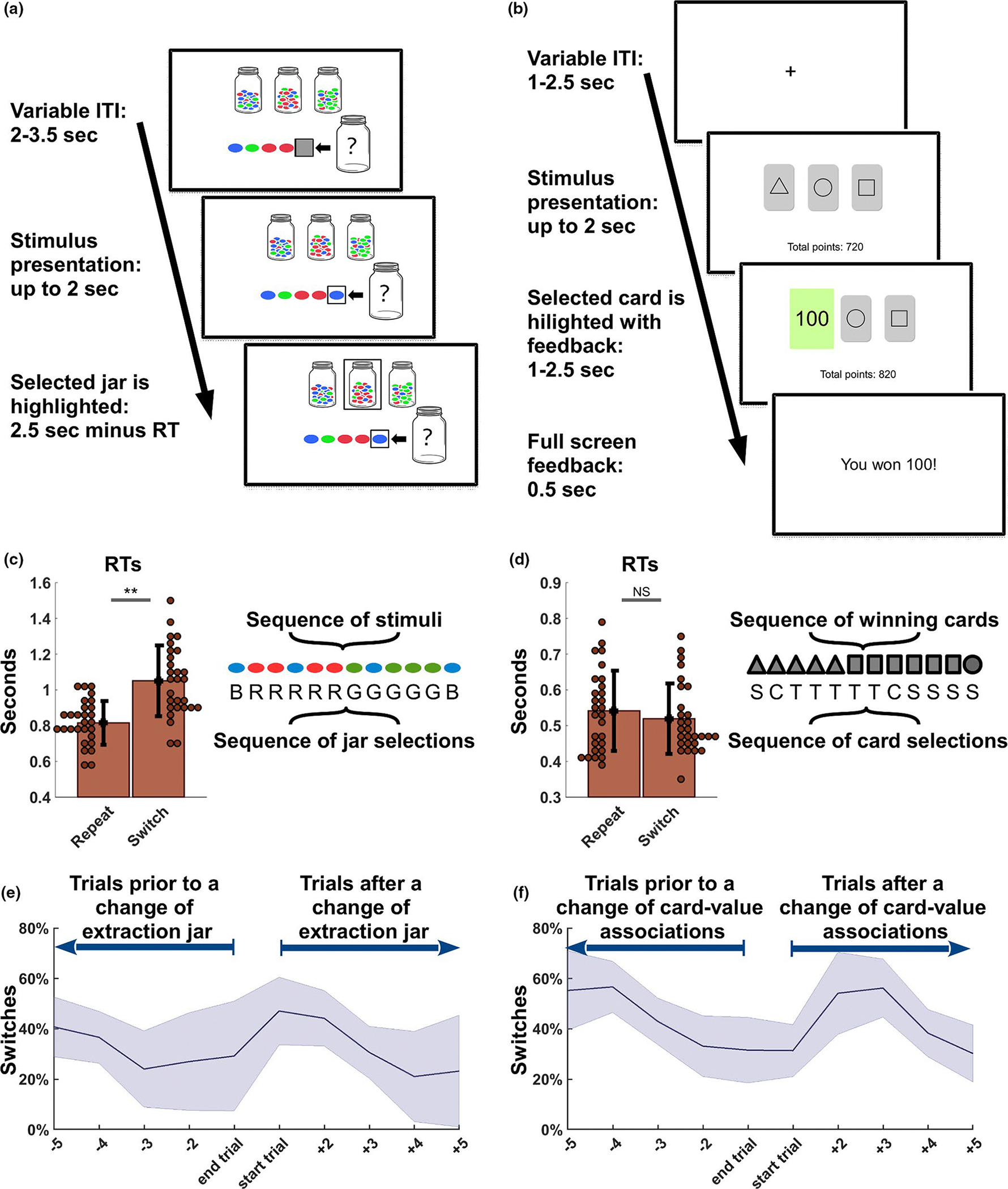

FIGURE 2.

Tasks and behavioural analysis. (a) The Bead task consists of a series of coloured beads extracted by the computer from one of three jars displayed on screen. These contain beads of three colours in a ratio of 80%:10%:10% and the participant can use three buttons to choose from which jar the latest bead has been extracted from. The last five extraction are displayed on screen and participants are informed that the computer will not change extraction jar every trial, so that the latest extractions can be informative in the participants’ estimations. No feedback is provided after choice selections. (b) In the Card task, participants can chose one among three cards displayed on screen. After each selection, a stochastic value-based feedback is presented to the participants, as each card is associated predominantly (80%) and exclusively to 100, 10 or 0 points. The associations change every few trials, motivating the participants to adapt their behaviour depending on the feedback received. (c) In the Bead task, reaction times (RTs) associated with trials resulting in a Switch (a change of selection in comparison with the previous one) show a significant longer time in a within-subject comparison with the RTs recorded for the Repeat trials (i.e., the repetition of a choice selection). A sequence of 12 stimuli and a sequence of 12 jar selections (B, R and G respectively indicate the selection of a jar characterized by predominantly blue, red or green beads) are here displayed to illustrate how a change in stimuli does not always result in a Switch trial, as these are only determined by the actual choices of the participants. Note that the actual changes of extraction jars can be inferred, but they are not directly accessible. (d) In the Card task, no difference was found in the comparison of the RTs characterizing the Switch trials and the Repeat trials. An illustrative representation of a sequence of 12 winning cards (i.e., cards associated with 100 points 80% of the times) is presented jointly with a sequence of hypothetical card selections (S, C and T respectively indicate the selection of a card characterized by a square, a circle or a triangle) to highlight the difference between changes in the card associations and actual behavioural changes or repetitions in choice selections. Note that, in this case, a stochastic feedback was present in the task after each choice, but it is not illustrated in this example. (e-f) Error bands illustrate mean and standard deviation for the percentage of switches recorded across all subjects in the five trials prior to or after any change of extraction jar (Bead task, panel E) or a change in the card-value associations (Card task, panel F). Extraction jars and card values remained unchanged for 5–7 trials, in pre-established pseudorandom sequences that were identical across subjects. Consistently, the number of switches peaks after a sequence change and then slowly decreases in the following trials, across tasks

The card task (Figure 2b) was also structured in 213 trials divided into three blocks (71 trials per block) and represented a modified version of the reversal learning task (O’Doherty et al., 2001). Each trial started with a fixation cross displayed on screen (variable ITI: 1–2.5 s), before the showing a deck of three cards. The participants were required to choose one among the three cards displayed on screen, each characterized by a random geometric figure (triangle, square, circle, star and diamond). After each selection, the participants received a stochastic feedback, highlighted in green, depending on the values pre-assigned to the cards (variable duration: 1–2.5 s). Each card was associated predominantly (80% of the time) to one of three outcomes (100, 10 or 0 points), and less frequently to the two remaining outcomes (10% each for each of the two). The lower part of the screen displayed continuously the total amount of points accumulated per block. Finally, after a written message on white screen signaling again the amount of points accumulated in the trial (fixed interval: 0.5 s), the screen displayed again the fixation cross, before the start of a new trial. As for the previous task, the accumulated points of one randomly selected session were used to determine a final compensation (500 points=$1). For this task, an initial training session was only meant to familiarize with the task and did not present any difference in comparison with the final fMRI version.

In both tasks, the participants were instructed that the computer would randomly change the extraction jar (bead task) or the distribution of predominant values (card tasks) every few trials. The pseudo-random sequences of extraction jars and card-value associations, identical for all participants, were actually pre-determined and changes took place with a pace of 5–7 trials (i.e., with 11 changes of extraction jars and card-value associations, per block, in both tasks), independent of the performance of the participants. Both the task order and the order of the three blocks in each task were counterbalanced across subjects. The fast pace of changes in the environment was conceived to increase the number of changes in the choice selections of the participants, but it was compatible with a performance above chance in both tasks. The participants selected the choice associated with the highest reward 74.7%±7.4 and 55.4%±7.5 of the trials, respectfully for the bead and card task, and they all performed above chance in both tasks (i.e., 33.3%). The two tasks shared a core structure in the organization of the trials, the volatility of the environment, the presence of three options and of three categorical and discrete types of evidence (i.e., three feedback values and the three bead colours). By contrast, the tasks present two key differences: (a) the presence or absence of a stochastic feedback and (b) the dynamics and cost of exploration, as abandoning a choice selection led to unbiased exploration of the remaining two options in the card task, whereas in the bead task the visual stimuli would offer a guide into the new optimal choice. The combination of these two elements is the likely cause of the significant difference that emerged in within-subject comparison of the accuracy measure (t(27) = 11.0, p < .001).

2.3 |. fMRI data acquisition, preprocessing and analysis

The study relied on a Philips 3-Tesla MR scanner at the Advanced Imaging Research Center at University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center to acquire functional MRI data. We used Multi Parametric Maps with a resolution of 1 mm (multi-echo MPRAGE) as anatomical scan sequence. Functional images (EPI) were acquired with a resolution of 3.4 × 3.4 × 4 mm, repetition time of 2 s, echo time of 25 ms, 38 axial slices, flip angle = 90°, and a field of view of 240 mm. Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM12, Wellcome Department of Imaging Neuroscience, running on Matlab R2018b) was used for the standard preprocessing to carry out motion realignment (first volume), coregistration to the participant’s anatomical scan, MNI normalization, and spatial smoothing, using an isotropic 8-mm full-width at half-maximum (FWHM) Gaussian kernel.

We analysed two types of events, termed Repeat and Switch. The former indicated a choice selection that was the same expressed in the previous trial and the latter indicated a change in choice selection, in comparison with the previous trial. Both events were considered independent of the actual stimuli presented to the subjects and only based on their choice selections. In this sense, both a Repeat and a Switch event could take place in association with either a congruent or an incongruent bead extraction, as well as in association with either a continuous or an interrupted streak of 100 points rewards (as illustrated in Figure 2c and 2d). We considered button presses as the key time point in the cognitive process leading to either a change or a repetition of choice selection, so the general linear model (GLM) analysis was time-locked to the button presses onsets. To account for the significantly different reaction times (RTs) associated with Switch and Repeat events (limited to the bead task; Figure 2c and 2d), we used RTs values as trial-by-trial covariates in both tasks. Two Boolean vectors were used as parametric modulators identifying either the Repeat or the Switch trials. The three blocks of each task were concatenated in the fMRI analysis. Finally, we used family-wise error (FWE) correction (PFWE<0.05; Figure 3a–3d) to determine significant whole-brain activations.

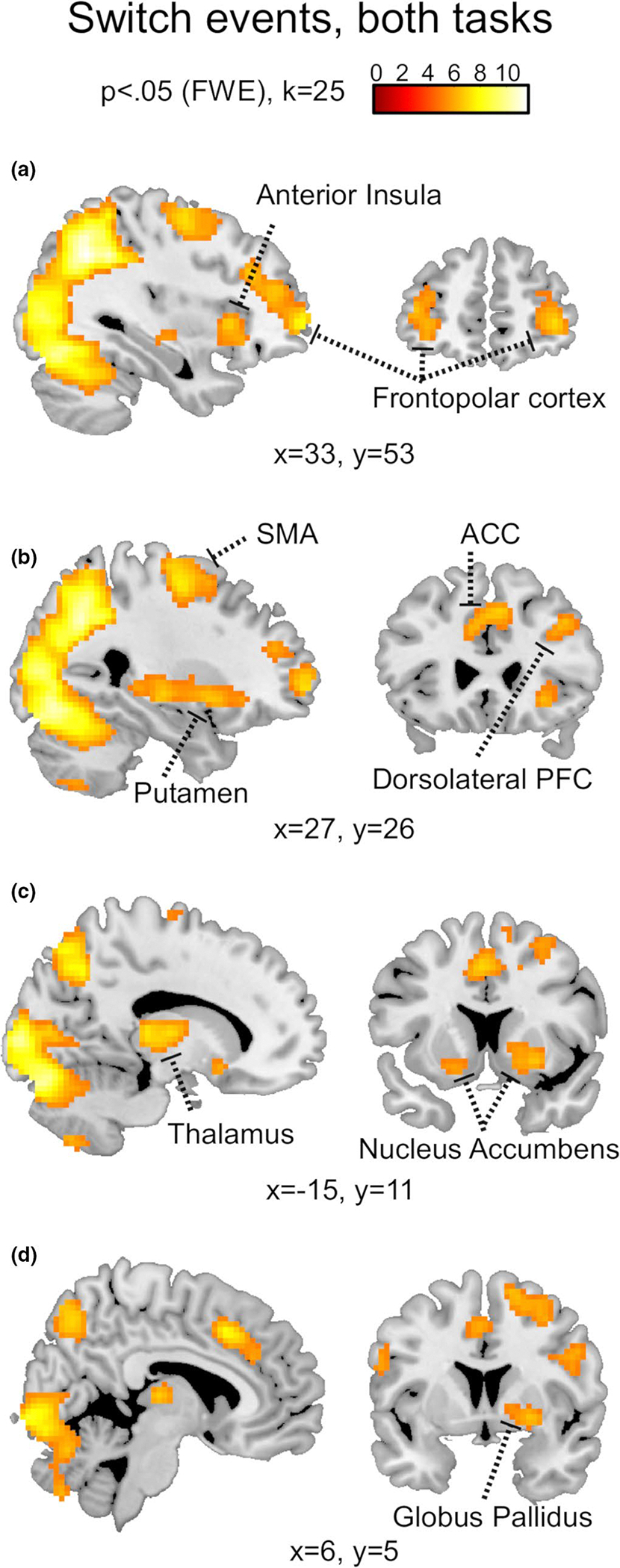

FIGURE 3.

Whole-brain BOLD responses associated with Switch trials. The neural response recorded across tasks in association with the trials characterized by a change in choice selections (PFWE<0.05, k = 25). In particular, the images highlight activity in the bilateral frontopolar cortex (a), right anterior insula (a), right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (b), anterior cingulate cortex (b) and supplementary motor area (b). At the subcortical level, imaging revealed activity in the right putamen (b), left thalamus (c), bilateral nucleus accumbens (c) and right globus pallidus (d)

2.4 |. Dynamic causal modelling

Brain connectivity measures may describe an architecture of synaptic connections (i.e., anatomical connectivity), statistical dependencies (i.e., functional connectivity), or directed causal interactions (i.e., effective connectivity) between single units or neural regions (Friston, 2011). In this study, we estimated the context- and time-dependent effective connectivity among three independent ROIs per hemisphere, using SPM12-DCM default functions. We extracted fMRI time series from the described parametrically modulated GLM analysis, using their principal eigenvariates, from four manually generated anatomical ROIs (available for download: https://identifiers.org/neurovault.collection:8534), defining external and internal parts of the GP in both hemispheres (Figure 4). Both tasks relied on visual stimuli, therefore we followed standard practice (cf. Friston et al., 2003; Stephan et al., 2007, 2008) by including the primary visual cortex (VC) as a network input region and defining a baseline stimulus-driven activation. This was achieved extracting the time series associated with the VC from a non-parametrically modulated GLM, which was also used to define task-specific spherical ROIs (8-mm radius), centred on the peak coordinates: [15 −88 2] and [−18 −94 2] for the bead task, [24–85 11] and [−21 to 94 11] for the card task.

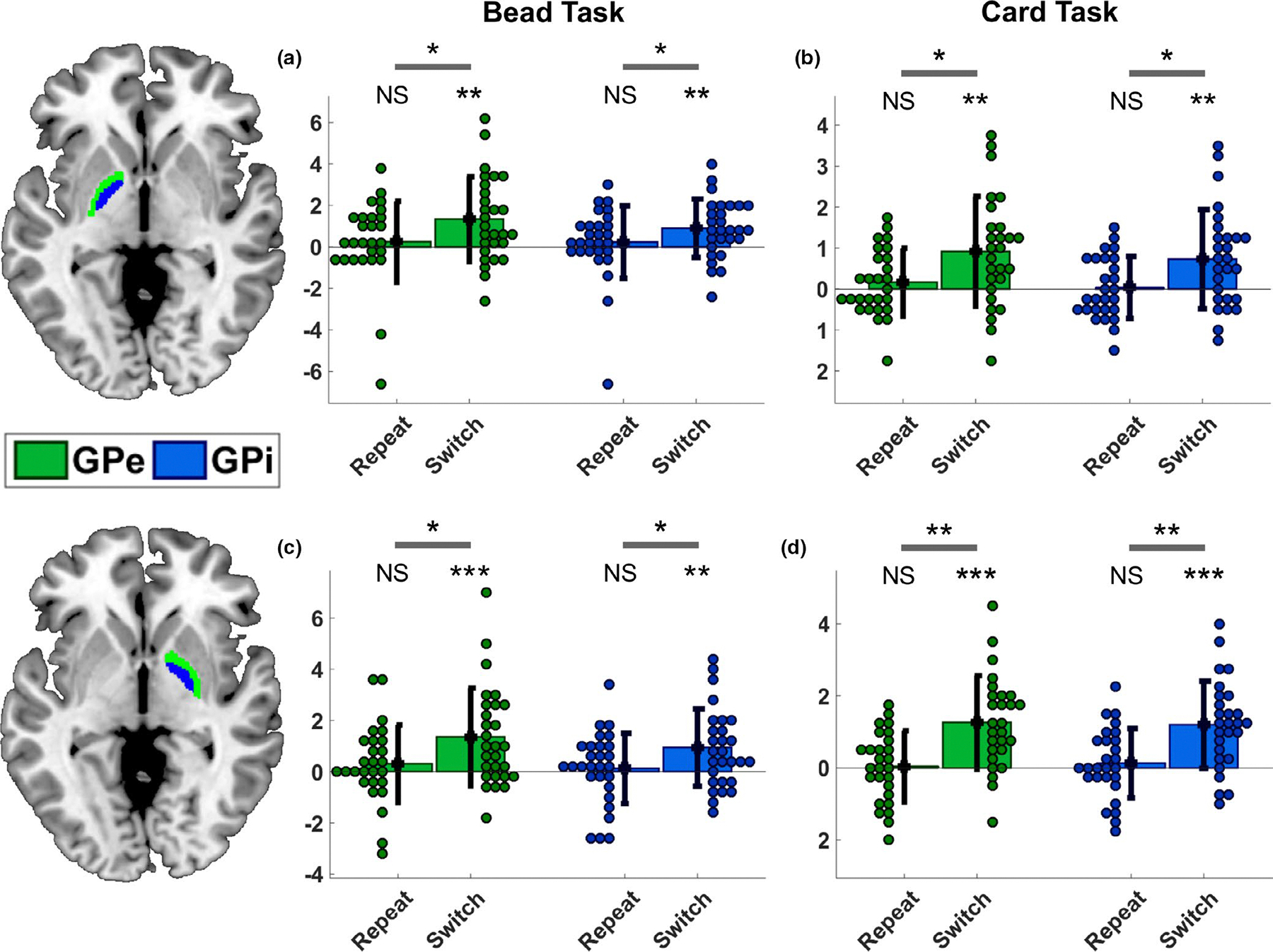

FIGURE 4.

ROI analysis of the globus pallidus. We extracted beta values using manually generated anatomical ROIs for the internal and external parts of the globus pallidus, bilaterally (available here: https://identifiers.org/neurovault.collection:8534). Our analysis (t-test within-subject comparisons) revealed a significant increase of BOLD response in association with Switch trials, but not Repeat trials, across tasks, and in the left (a,b) as well as in the right hemisphere (c,d). Note that the whole-brain analysis only revealed activity in the right globus pallidus after family-wise correction. However, the extracted beta values show that the activity in the globus pallidus in both hemispheres was sufficient to run a DCM analysis across tasks. NS: not significant; *p < .05; **p < .005; ***p < .0005

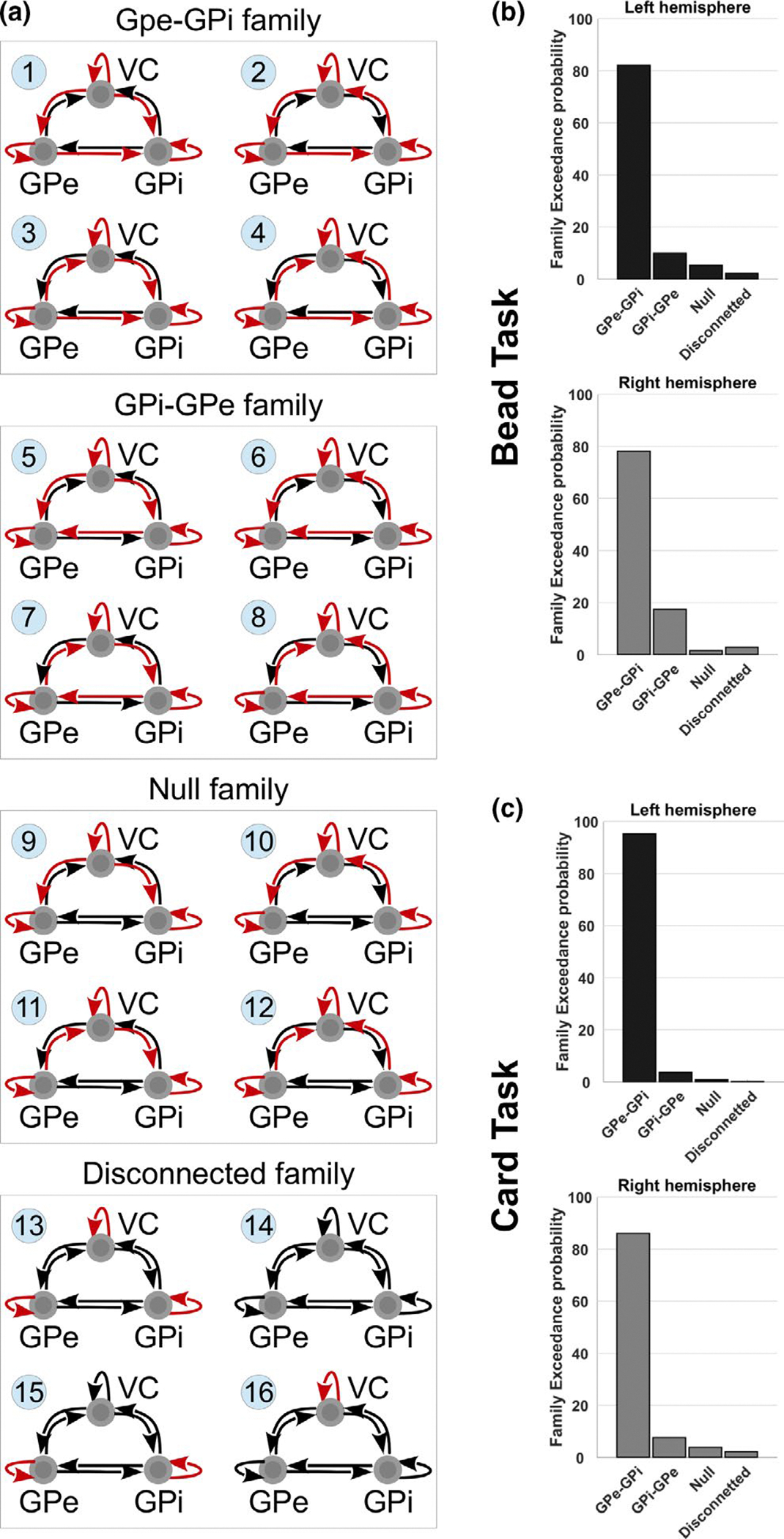

In DCM, competing hypotheses of causal relations among regions of interest are embodied in model architectures, which are compared to establish their relative probability of being correct (Friston et al., 2003; Penny et al., 2010; Stephan et al., 2010). The results of the analysis are summarized in the exceedance probability of each model or family of models, which represents how well a model or family replicates the data of a randomly chosen subject, in comparison with any competing model or family (Friston et al., 2003). Key elements in the definition of these models are three matrices. The A-matrix defines baseline connections of the network equivalent to a task-free network; the B matrix defines which of the A Matrix connections are modulated by the signal of interest, thus allowing context- and time-dependent variations of effective connectivity; finally the C matrix defines where the “driving input” (in this case the visual stimuli), enters the system (Friston et al., 2003; Penny et al., 2004; Stephan et al., 2010). To determine the network architectures to be used in the present DCM analysis, we focused on those structures that could inform about the time- and context-dependent GPe-GPi directional relationships. This was not meant to exhaust all possible model architectures, as we sought a balance between generalizability and feasibility (Stephan et al., 2010). We used two criteria to generate the neural architectures: (a) they had to be characterized by different targets for the modulatory signal, and (b) they had to be computationally comparable in terms of the number of free parameters (cf. Yu et al., 2020). These criteria led to the decision to include an input region in the VC, two nodes (one for each GP part) and assuming each node projected directed connectivity towards all other nodes as well as recurrent self-connections, so defining the A matrix. We then created four basic variations for the targets of the modulatory input (the B matrix), which was represented by the Boolean vector of Switch trials. For these four models, we kept constant the number of modulated connections and we varied the targets of the modulatory signal, so that it would affect all self-connections as well as VC-GPi and VC-GPe connectivity in a single direction. These four models were used to generate three separate families, each characterized by the same four basic architectures, varying the target of the modulatory signal for the GPe-GPi directed connectivity: GPe-to-GPi (models 1–4, Figure 5a), GPi-to-GPe (models 5–8, Figure 5a) or no modulation for the GP (models 9–12, Figure 5a). A fourth family of four models was also included to test various “disconnected” architectures (models 13–16, Figure 5a). These last models were conceived to ensure that: (a) the modulatory signal was necessary to improve the efficacy of the model in replicating the target imaging data; (b) the modulation of the self-connectivity would not be sufficient to explain the target data. Finally, we directed the sensory input towards the node expressing the activity of the VC across all models (C matrix).

FIGURE 5.

DCM results using family-wise comparison. (a) Architecture for the 16 neural models tested using DCM, in association with trials characterized by changes in choice selections (GPi: globus pallidus pars interna; GPe: globus pallidus pars externa; VC: visual cortex). Arrows are used to indicate directed connectivity in the neural model (A matrix), where red arrows indicate those connections that are modulated by the signal of the Switch trials (B matrix). These models were grouped into four families: the first characterized by a GPe-to-GPi modulated connectivity (models 1–4); a second characterized by a GPi-to-GPe modulated connectivity (models 5–8); a third characterized by absence of modulated connectivity between GPe and GPi, in any direction (models 9–12); finally, a fourth family characterized by the absence of modulated connectivity among all three ROIs (models 13–16). Histograms report the family Exceedance probability for the four tested families of models. The family characterized by a modulated connectivity from GPe towards GPi is found to be the most likely to explain the fMRI BOLD activity recorded in association with changes of choice selections in both bead (b) and card tasks (c), across hemispheres. The test was repeated independently across hemispheres and tasks for the cross-validation of the results

The 16 resulting models (Figure 5a) were compared relying on the four described families in a Bayesian family-wise random effect approach. These are standard and orthogonal options available in the SPM12 package for the DCM analysis and were determined for two independent reasons (Friston et al., 2003). First, we relied on a random effect approach to account for the possibility of heterogeneity in the optimal model structure across subjects, as we assumed the switching behaviour could rely on different, that is subject-specific, neuronal implementations (Stephan et al., 2010). Second, we used a family-wise analysis to partition the model space depending on the structural hypothesis of interest (i.e., GPe-GPi-directed connectivity), thus allowing family-level inference and reducing the uncertainty about other aspects of model structure (Penny et al., 2010; Stephan et al., 2010). We subsequently also completed two further exploratory analyses, based on random effect, to investigate whether any single model could be found to drive the main family-wise result, as well as to determine the effective connectivity between the VC and either of the two parts of the GP. Independent DCM analysis was used for both hemispheres and for both tasks to grant a cross-validation of the results within and between tasks.

3 |. RESULTS

First, we analysed the RTs to test whether choice selections in Switch trials (i.e., change of selections in comparison with the one expressed in the previous trials) would differ from those in Repeat trials (i.e., choice selections that confirmed the previous one). In a within-subjects t-test comparison, we used the mean RTs recorded for each type of trial, per participant, and we found that switches required significant longer time than repetitions in the bead task (t(27) = −10.76, p < .001, Figure 2c), but not in the card task (t(27) = 1.4, p = .17, Figure 2d). We speculate that this is because participants in the card task could decide their next choice selection during the ITI, which in the card task took place after the presentation of the value-based feedbacks. Conversely, in the bead task, the ITI took place before the presentation of a new bead, so the RTs are more likely to reflect the deliberation process leading to choice selections.

Next, we used the RTs as trial-by-trial covariates in both tasks to reduce the effect that differential motor efforts have on brain activity and in particular on the basal ganglia (Pessiglione et al., 2007; Spraker et al., 2007; Vaillancourt et al., 2004). We examined the whole-brain neural activations associated with the Switch and the Repeat trials, across tasks, FWE corrected at p < .05. We found that switching choice selection relied on the involvement of multiple brain regions (see Table 1 for details). In particular, bilateral frontopolar and anterior insular cortices (Figure 3a and 3b), right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (Figure 3b), anterior cingulate cortex (Figure 3b), bilateral nucleus accumbens and GP (Figure 3c and 3d). Conversely, BOLD activity recorded in association with the Repeat trials revealed only a response in the left mid insula (peak at coordinates: x = −39, y = −4, z = 14) after FWE correction. Activity in the GPe and GPi was of particular importance for the purpose of this study and was further analysed independently in each task, under both conditions. We found that beta values extracted from our manually generated anatomical ROIs indicated significant increase of activity, in comparison with baseline, in both GPe and GPi, bilaterally, in association with Switch trials, for both bead (GPe-left: t(27) = 3.48, p = .002; GPe-right: t(27) = 3.77, p < .001; GPi-left: t(27) = 3.39, p = .002; GPi-right: t(27) = 3.3, p = .003; Figure 4a and 4c) and card task (GPe-left: t(26) = 3.55, p = .001; GPe-right: t(26) = 5.05, p < .001; GPi-left: t(26) = 3.13, p = .004; GPi-right: t(26) = 5.16, p < .001; Figure 4b and 4d). The same ROIs were not found to be associated with any significant change in BOLD activity in association with the Repeat trials (Figure 4a–4d).

TABLE 1.

Peak activity for key neural regions found active in association with Switch trials, across both tasks (p <.05, FWE correction)

| Cortical Regions | L/R | Coordinates |

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | T | Z | k | ||

| Lateral frontopolar cortex | R | 30 | 59 | −1 | 7.82 | 6.33 | 395 |

| L | −36 | 56 | −4 | 6.56 | 5.58 | 121 | |

| Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex | R | 42 | 32 | 32 | 7.82 | 6.33 | 395 |

| Anterior cingulate cortex | − | 3 | 20 | 41 | 7.86 | 6.35 | 359 |

| Anterior insular cortex | R | 33 | 20 | 2 | 7.21 | 5.97 | 591 |

| L | −30 | 17 | −7 | 6.43 | 5.49 | 73 | |

| Supplementary motor area | R | 27 | −7 | 56 | 7.36 | 6.07 | 382 |

| L | −27 | −10 | 65 | 7.70 | 6.26 | 212 | |

| Subcortical regions | L/R | x | y | z | T | Z | k |

| Thalamus | R | 12 | −13 | 8 | 7.21 | 5.97 | 591 |

| L | −12 | −13 | 8 | 7.53 | 6.16 | 203 | |

| Nucleus accumbens | L | −18 | 14 | −10 | 6.07 | 5.25 | 73 |

| Putamen | R | 24 | 8 | −4 | 6.53 | 555 | 591 |

We had planned to test the directed effective connectivity between GPe and GPi in association with both Switch and Repeat trials. Unfortunately, the BOLD response reported for the two types of GLM only allowed to use DCM in association with the Switch trials. We applied family-wise comparisons independently across hemispheres and across tasks to compare four families of four models (Figure 5a). We found a high likelihood that the Switch trials were associated with a directed influence of the GPe towards the GPi [exceedance probability for the bead task: GPe-GPi:~82%, GPi-GPe:~10%, Null:~5%, Disconnected:~2% (left hemisphere), ~78%, ~17%, ~1%, ~3% (right hemisphere), Figure 5b; card task: ~95%, ~4%, ~1%, ~0% (left), ~86%, ~8%, ~4%, ~2% (right), Figure 5c].

An exploratory random effect analysis for single model comparison did not reveal a clear convergence of results across conditions or hemispheres. Several models characterized by an exceedance probability above 5% were found in the bead task [model 1:~7%, model 2:~27%, model 3:~8%, model 4:~16%, model 5:~6%, model 6:~8% (left hemisphere), model 1:~6%, model 2:~22%, model 3:~5%, model 4:~21%, model 7:~6%, model 8:~10%, model 15:~11% (right hemisphere), cf. Figure 5a], as well as in the card task [model 1:~40%, model 2:~5%, model 4:~23% (left hemisphere), model 1:~8%, model 2:~38%, model 4:~16%, model 5:~8%, model 9:~6% (right hemisphere), cf. Figure 5a]. This result indicates that no single architecture was found to be likely to replicate the target data across tasks or hemispheres, thus confirming the necessity to partition the model space (i.e., comparing families of models) to reduce the uncertainty derived from non-relevant aspects of model structure (Stephan et al., 2010). Consistent with this distribution of results, an exploratory analysis for the VC-GPe and VC-GPi modulated directed connectivity did not reveal converging results within task, across hemispheres.

Finally, a within-subject comparison of the DCM-estimated weights associated with the GPe-GPi connectivity for the left and right hemisphere did not reveal any significant difference for either the A matrix or the B matrix, in the bead task (A matrix, left: 0.10 ± 0.16; right: 0.10 ± 0.17; t(27) = −0.13, p = .90; B matrix, left: −0.04 ± 0.32; right: 0.12 ± 1.27; t(27) = −0.62, p = .54) or the card task (A matrix task, left: 0.20 ± 0.16; right: 0.17 ± 0.22; t(26) = 0.66, p = .52; B matrix, left: −0.09 ± 0.95; right: −0.12±0.98; t(26) = −0.26, p = .8). Thus, we compared the GPe-G Pi estimated connectivity in the two tasks using the subject-specific estimates averaged for both hemispheres. The weights estimated for the B matrix did not show any difference across tasks (bead task: 0.04 ± 0.62 card task: −0.1 ± 0.91; t(26) = 0.57, p = .57). Conversely, a t-test comparison of the estimated A matrix GPe-GPi weights revealed lower values for the bead task in comparison with the card task (bead task: 0.10 ± 0.11 card task: 0.18 ± 0.15; t(26) = −2.12, p = .04). The two tasks also differed in terms of the number of Switch trials per subject (bead task: 55.3 ± 27.4, card task: 38.5 ± 5.6; t(27) = 3.36, p = .002) and in the associated average RTs (bead task: 1.05 ± 0.20, card task: 0.52 ± 0.10; t(27) = 12.03, p < .001). However, the GPe-GPi weights estimated for the A matrix or the B matrix were not found to be correlated with the number of changes of choice selections (bead task A matrix/B matrix: p = .46/p = .88; card task A matrix/B matrix: p = .55, p = .87) or with the average RTs per Switch trial (bead task A matrix/B matrix: p = .42/p = .94; card task A matrix/B matrix: p = .22, p = .49).

4 |. DISCUSSION

We investigated the neural dynamics associated with the choice to either change or confirm a previous choice selection in two multi-options decision-making tasks (Churchland et al., 2008; Tajima et al., 2019). Healthy participants (n = 28) performed a sequence of choice selections, responding to either a sequence of visual stimuli or value-based feedbacks, and adapting to pseudo-random and uncontrollable changes in the environment. We found that, irrespective of the task, the Switch trials (i.e., trials characterized by a change in choice selection) were associated with a widely distributed neural response that partially overlapped with previously described networks associated with the encoding of uncertainty (Ma & Jazayeri, 2014; Morriss et al., 2018; White et al., 2014). Namely, we found that these trials were associated with activities in the anterior insula, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, and anterior cingulate cortex (Figure 3). This finding is consistent with the common task structure, which required a choice among multiple alternatives (Churchland et al., 2008; Tajima et al., 2019), as changes in behavioural policy coincide with the accumulation of conflicting evidence (and therefore uncertainty). This interpretation is also supported by the fact that Switch trials were found to be associated with increased activity in the lateral frontopolar cortex, responsible for mediating exploration and rapid learning about values assigned to behavioural strategies (Boschin et al., 2015). Conversely, the BOLD response recorded across tasks in association with Repeat trials revealed activity in the left mid-insular cortex (PFWE < 0.05). Interestingly, this reduced neural engagement is not always associated with confirming evidence, as the category of the “Repeat trials” includes all trials in which a choice is confirmed, irrespective of the stimulus or feedback available. The finding suggests that within the context of the two chosen tasks, the repetition of previously determined choices may be relying on a form of simplified monitoring of the information available in the environment (Kurth et al., 2010).

Importantly, we found that both the GPe and GPi were significantly active in association with the Switch trials, bilaterally and in both tasks. It might be argued that the response we found for the GPe can be understood within the framework of the pro-kinetic versus anti-kinetic theory (e.g., see: Li et al., 2014), postulating that the indirect pathway is more active when motor activity is slowed down, as for instance indicated by RTs in the bead task. Accordingly, the activity in the GPi would be explained in terms of motor initiation, as a new choice selection is indeed completed in Switch trials. However, longer RTs in these trials were only found in one of the two tasks, while we found significant increase in BOLD activity across tasks. Furthermore, by using RTs as covariates, we likely counteracted or reduced the effects of differential RTs on BOLD responses.

Previous neural mass models had predicted that changes of choice selections (Switch trials) would be associated with a GPe to GPi directed causal influence, whereas repetitions of choice selections would be associated with reduced GPe-GPi influence (Fiore et al., ,2016, 2018). These models hypothesized that the neural dynamics of the basal ganglia circuit are better understood in terms of the stability of the state transitions they determine. Within this framework, the short indirect pathway (D2 striatum-GPe-GPi) would be responsible for destabilizing the circuit and pushing towards alternative selections. We used DCM to estimate the causal relations between GPe and GPi and thus tested such prediction. Our findings supported the hypothesis that changes in choice selection are associated with signaling directed from the GPe towards the GPi, irrespective of the task processes, that is, the presence or absence of explicit outcomes and the different exploration costs. Family-wise DCM indicated with high likelihood that the effective connectivity between GPe and GPi was modulated by the presence of Switch trials, establishing that the GPe is causally affecting the activity in the GPi during these shifts of policy. Since the regressor for this analysis was time-locked with choice selections (button presses), this result again suggests that the directed influence exerted by the GPe towards the GPi contributed to the process of choice changes, rather than triggering motor suppression. To further investigate the relation between GPe-GPi connectivity and behaviour, we analysed the relation between our behavioural measures and DCM-estimated baseline connectivity (i.e., A matrix) or modulation weight for the signal of interest (i.e., B matrix). We found a marginally significant difference in the comparison between tasks limited to the A matrix, but these estimated values were not correlated with behavioural measures such as the subject-specific average RTs for the switch trials or the number of changes in choice selections, per task. As a result, we could not establish a relation between estimated connectivity and either motor suppression (where an increase in connection weights would have predicted longer RTs, as by the pro-kinetic/anti-kinetic model) or changes in choice selections (where a direct correlation was expected between connectivity weights and number of switches, as by the stability/instability model). Finally, this analysis also suggests that differences in terms of the available information (i.e., choice selections with or without explicit feedback) or exploration costs have limited effects on the estimations of the network connectivity weights.

This investigation presents two limitations that suggest further studies are required to solve the theoretical dispute between the pro-kinetic/anti-kinetic model and the stability/instability in state transitions model of the basal ganglia dynamics and functions. First, none of the 16 DCM models that were used for the Switch trials included a node for the sub-thalamic nucleus, thus excluding both a key ROI in the control of the activity of the GPe and the hyperdirect pathway in the basal ganglia (Nambu et al., 2002). This choice was motivated by the voxel size used for the present study, which resulted in a poor signal-to-noise ratio in small volume ROIs, like the sub-thalamic nucleus. A different analysis, based on 7T ultra high field functional images, is required to solve this problem and allow testing DCM architectures that would be closer to the actual neural connectome of the Basal Ganglia. Other circuit improvements, such as the inclusion of the striatum as a fourth node of the network, would have been possible, ideally allowing to investigate context-specific striatal-GP effective connectivity, and differential signal encoding in the direct and indirect pathway (Nonomura et al., 2018; Vicente et al., 2016). However, the striatal neurons affecting the activity in the GPi (the direct pathway) and those affecting the GPe (indirect pathway) are interspersed (Alexander & Crutcher, 1990; DeLong, 1990), therefore fMRI would not discern pathway-specific activity, potentially generating a confound in the interpretation of the results.

The second limitation concerns the Repeat trials, which were expected to be associated with reduced influence of the GPe towards the GPi, thus also offering a control condition for the analysis of the Switch trials. However, the lack of BOLD activity recorded in association with the Repeat trials did not allow this analysis. We hypothesize that the difference in terms of the GP activity associated with either Switch or Repeat trials might have been induced by the task structure. Trials triggering switching have evoked a strong response across multiple cortical regions, possibly due to the high saliency of the trials that motivate a change in choice selections. In turn, the high cortical activity has likely caused an increased response in the two parts of the GP, mediated by the hyperdirect pathway (Sieger et al., 2015). The Repeat trials failed in evoking the initial strong cortical response, thus resulting in reduced GP activation. In this case, a change in the task design might be required to overcome this issue.

5 |. CONCLUSIONS

We reported a directed influence of the GPe towards the GPi that seems to play a key role in actively determining changes of choice selections. This finding confirmed across tasks and across hemispheres, provides yet further elements of validation for a computational representation of the basal ganglia dynamics in terms of their effects on the stability of state transitions in the cortico–striatal circuits (cf. Fiore et al., ,2016, 2018). This change of perspective could transform a one-dimensional pro-kinetic/anti-kinetic account into a multi-dimensional representation of network dynamics. In turn, such a multi-dimensional characterization would account for endophenotypic variations associated with basal ganglia dysfunctions, across multiple sensori-motor and cognitive processes (Addicott et al., 2017; Maia & Frank, 2011).

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Jennifer Jung for her help in setting up the code for both tasks (Psychtoolbox 3 library in Matlab R2015b). VGF is funded by the Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center (MIRECC VISN 2) at the James J. Peter Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Bronx, NY. XG is supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse [grant numbers: R01DA043695, R21DA049243] and National Institute of Mental Health [grant numbers: R21MH120789, R01MH124115, R01MH122611].

Abbreviations:

- DCM

Dynamic Causal Modeling

- GPe

Globus Pallidus pars externa

- GPi

Globus Pallidus pars interna

- RTs

reaction times

- STN

Sub-Thalamic Nucleus

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors report no competing financial or non-financial interests.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Single-subject GLM results and associated DCM estimations are available in the public repository G-Node (DOI: 10.12751/g-node.rmb9z3).

REFERENCES

- Abdi A, Mallet N, Mohamed FY, Sharott A, Dodson PD, Nakamura KC, Suri S, Avery SV, Larvin JT, Garas FN, Garas SN, Vinciati F, Morin S, Bezard E, Baufreton J, & Magill PJ (2015). Prototypic and arkypallidal neurons in the dopamine-intact external globus pallidus. Journal of Neuroscience, 35, 6667–6688. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4662-14.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams RA, Moutoussis M, Nour MM, Dahoun T, Lewis D, Illingworth B, Veronese M, Mathys C, de Boer L, Guitart-Masip M, Friston KJ, Howes OD, & Roiser JP (2020). Variability in action selection relates to striatal dopamine 2/3 receptor availability in humans: A PET neuroimaging study using reinforcement learning and active inference models. Cerebral Cortex, 30(6), 3573–3589. 10.1093/cercor/bhz327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Addicott MA, Pearson JM, Sweitzer MM, Barack DL, & Platt ML (2017). A primer on foraging and the explore/exploit trade-off for psychiatry research. Neuropsychopharmacology, 42, 1931–1939. 10.1038/npp.2017.108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afraimovich V, Tristan I, Huerta R, & Rabinovich MI (2008). Winnerless competition principle and prediction of the transient dynamics in a Lotka-Volterra model. Chaos, 18, 43103. 10.1063/1.2991108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albin RL, Young AB, & Penney JB (1989). The functional anatomy of basal ganglia disorders. Trends in Neurosciences, 12, 366–375. 10.1016/0166-2236(89)90074-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander GE (1994). Basal ganglia-thalamocortical circuits: Their role in control of movements. Journal of Clinical Neurophysiology, 11, 420–431. 10.1097/00004691-199407000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander GE, & Crutcher MD (1990). Functional architecture of basal ganglia circuits: Neural substrates of parallel processing. Trends in Neurosciences, 13, 266–271. 10.1016/0166-2236(90)90107-L [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander GE, DeLong MR, & Strick PL (1986). Parallel organization of functionally segregated circuits linking basal ganglia and cortex. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 9, 357–381. 10.1146/annurev.ne.09.030186.002041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevan MD, Magill PJ, Terman D, Bolam JP, & Wilson CJ (2002). Move to the rhythm: Oscillations in the subthalamic nucleus-external globus pallidus network. Trends in Neurosciences, 25, 525–531. 10.1016/S0166-2236(02)02235-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogacz R, & Gurney K (2007). The basal ganglia and cortex implement optimal decision making between alternative actions. Neural Computation, 19, 442–477. 10.1162/neco.2007.19.2.442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogacz R, & Larsen T (2011). Integration of reinforcement learning and optimal decision-making theories of the basal ganglia. Neural Computation, 23, 817–851. 10.1162/NECO_a_00103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogacz R, Martin Moraud E, Abdi A, Magill PJ, & Baufreton J (2016). Properties of neurons in external globus pallidus can support optimal action selection. PLoS Computational Biology, 12, e1005004.– 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boschin EA, Piekema C, & Buckley MJ (2015). Essential functions of primate frontopolar cortex in cognition. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112, E1020–1027. 10.1073/pnas.1419649112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JW, Bullock D, & Grossberg S (2004). How laminar frontal cortex and basal ganglia circuits interact to control planned and reactive saccades. Neural Networks, 17, 471–510. 10.1016/j.neunet.2003.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Churchland AK, Kiani R, & Shadlen MN (2008). Decision-making with multiple alternatives. Nature Neuroscience, 11, 693–702. 10.1038/nn.2123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLong MR (1983). The neurophysiologic basis of abnormal movements in basal ganglia disorders. Neurobehav Toxicol Teratol, 5, 611–616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLong MR (1990). Primate models of movement disorders of basal ganglia origin. Trends in Neurosciences, 13, 281–285. 10.1016/0166-2236(90)90110-V [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore VG, Nolte T, Rigoli F, Smittenaar P, Gu X, & Dolan RJ (2018). Value encoding in the globus pallidus: fMRI reveals an interaction effect between reward and dopamine drive. NeuroImage, 173, 249–257. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.02.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore VG, Rigoli F, Stenner MP, Zaehle T, Hirth F, Heinze HJ, & Dolan RJ (2016). Changing pattern in the basal ganglia: Motor switching under reduced dopaminergic drive. Scientific Reports, 6, 23327. 10.1038/srep23327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank MJ, Seeberger LC, & O’Reilly RC (2004). By carrot or by stick: Cognitive reinforcement learning in parkinsonism. Science, 306, 1940–1943. 10.1126/science.1102941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friston KJ (2011). Functional and effective connectivity: A review. Brain Connectivity, 1, 13–36. 10.1089/brain.2011.0008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friston KJ, Harrison L, & Penny W (2003). Dynamic causal modelling. NeuroImage, 19, 1273–1302. 10.1016/S1053-8119(03)00202-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gittis AH, Berke JD, Bevan MD, Chan CS, Mallet N, Morrow MM, & Schmidt R (2014). New roles for the external globus pallidus in basal ganglia circuits and behavior. Journal of Neuroscience, 34, 15178–15183. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3252-14.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurney K, Prescott TJ, & Redgrave P (2001a). A computational model of action selection in the basal ganglia. I. A New Functional Anatomy. Biol Cybern, 84, 401–410. 10.1007/PL00007984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurney K, Prescott TJ, & Redgrave P (2001b). A computational model of action selection in the basal ganglia. II. Analysis and simulation of behaviour. Biological Cybernetics, 84, 411–423. 10.1007/PL00007985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser TU, Fiore VG, Moutoussis M, & Dolan RJ (2016). Computational psychiatry of ADHD: Neural gain impairments across marrian levels of analysis. Trends in Neurosciences, 39, 63–73. 10.1016/j.tins.2015.12.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegeman DJ, Hong ES, Hernandez VM, & Chan CS (2016). The external globus pallidus: Progress and perspectives. European Journal of Neuroscience, 43, 1239–1265. 10.1111/ejn.13196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphries MD, Stewart RD, & Gurney KN (2006). A physiologically plausible model of action selection and oscillatory activity in the basal ganglia. Journal of Neuroscience, 26, 12921–12942. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3486-06.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huq SF, Garety PA, & Hemsley DR (1988). Probabilistic judgements in deluded and non-deluded subjects. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. A, Human Experimental Psychology, 40, 801–812. 10.1080/14640748808402300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin X, Tecuapetla F, & Costa RM (2014). Basal ganglia subcircuits distinctively encode the parsing and concatenation of action sequences. Nature Neuroscience, 17, 423–430. 10.1038/nn.3632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaus A, Alves da Silva J, & Costa RM (2019). What, if, and when to move: Basal ganglia circuits and self-paced action initiation. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 42, 459–483. 10.1146/annurevneuro-072116-031033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurth F, Zilles K, Fox PT, Laird AR, & Eickhoff SB (2010). A link between the systems: Functional differentiation and integration within the human insula revealed by meta-analysis. Brain Structure and Function, 214, 519–534. 10.1007/s00429-010-0255-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Friston KJ, Liu J, Liu Y, Zhang G, Cao F, Su L, Yao S, Lu H, & Hu D (2014). Impaired frontal-basal ganglia connectivity in adolescents with internet addiction. Scientific Reports, 4, 5027. 10.1038/srep05027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma WJ, & Jazayeri M (2014). Neural coding of uncertainty and probability. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 37, 205–220. 10.1146/annurevneuro-071013-014017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maia TV, & Frank MJ (2011). From reinforcement learning models to psychiatric and neurological disorders. Nature Neuroscience, 14, 154–162. 10.1038/nn.2723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallet N, Micklem BR, Henny P, Brown MT, Williams C, Bolam JP, Nakamura KC, & Magill PJ (2012). Dichotomous organization of the external globus pallidus. Neuron, 74, 1075–1086. 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.04.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marr D, & Poggio T (1976). From understanding computation to understanding neural circuitry. Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Artificial Intelligence Laboratory. [Google Scholar]

- Mastro KJ, Bouchard RS, Holt HA, & Gittis AH (2014). Transgenic mouse lines subdivide external segment of the globus pallidus (GPe) neurons and reveal distinct GPe output pathways. Journal of Neuroscience, 34, 2087–2099. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4646-13.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy MM, Moore-Kochlacs C, Gu X, Boyden ES, Han X, & Kopell N (2011). Striatal origin of the pathologic beta oscillations in Parkinson’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 108, 11620–11625. 10.1073/pnas.1107748108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mink JW (1996). The basal ganglia: Focused selection and inhibition of competing motor programs. Progress in Neurobiology, 50, 381–425. 10.1016/S0301-0082(96)00042-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morriss J, Gell M, & van Reekum CM (2018). The uncertain brain: A coordinate based meta-analysis of the neural signatures supporting uncertainty during different contexts. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 96, 241–249. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nambu A, Tokuno H, & Takada M (2002). Functional significance of the cortico-subthalamo-pallidal ‘hyperdirect’ pathway. Neuroscience Research, 43, 111–117. 10.1016/S0168-0102(02)00027-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson AB, & Kreitzer AC (2014). Reassessing models of basal ganglia function and dysfunction. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 37, 117–135. 10.1146/annurevneuro-071013-013916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonomura S, Nishizawa K, Sakai Y, Kawaguchi Y, Kato S, Uchigashima M, Watanabe M, Yamanaka K, Enomoto K, Chiken S, Sano H, Soma S, Yoshida J, Samejima K, Ogawa M, Kobayashi K, Nambu A, Isomura Y, & Kimura M (2018). Monitoring and updating of action selection for goal-directed behavior through the striatal direct and indirect pathways. Neuron, 99(1302–1314), e1305. 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obeso JA, Rodriguez-Oroz MC, Stamelou M, Bhatia KP, & Burn DJ (2014). The expanding universe of disorders of the basal ganglia. Lancet, 384, 523–531. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62418-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Doherty J, Kringelbach ML, Rolls ET, Hornak J, & Andrews C (2001). Abstract reward and punishment representations in the human orbitofrontal cortex. Nature Neuroscience, 4, 95–102. 10.1038/82959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penny WD, Stephan KE, Daunizeau J, Rosa MJ, Friston KJ, Schofield TM, & Leff AP (2010). Comparing families of dynamic causal models. PLoS Computational Biology, 6, e1000709.– 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penny WD, Stephan KE, Mechelli A, & Friston KJ (2004). Comparing dynamic causal models. NeuroImage, 22, 1157–1172. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.03.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pessiglione M, Schmidt L, Draganski B, Kalisch R, Lau H, Dolan RJ, & Frith CD (2007). How the brain translates money into force: A neuroimaging study of subliminal motivation. Science, 316, 904–906. 10.1126/science.1140459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin JE (2017). Computational models of basal ganglia dysfunction: The dynamics is in the details. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 46, 127–135. 10.1016/j.conb.2017.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroll H, Vitay J, & Hamker FH (2012). Working memory and response selection: A computational account of interactions among cortico-basalganglio-thalamic loops. Neural Networks, 26, 59–74. 10.1016/j.neunet.2011.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieger T, Serranova T, Ruzicka F, Vostatek P, Wild J, Stastna D, Bonnet C, Novak D, Ruzicka E, Urgosik D, & Jech R (2015). Distinct populations of neurons respond to emotional valence and arousal in the human subthalamic nucleus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112, 3116–3121. 10.1073/pnas.1410709112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spraker MB, Yu H, Corcos DM, & Vaillancourt DE (2007). Role of individual basal ganglia nuclei in force amplitude generation. Journal of Neurophysiology, 98, 821–834. 10.1152/jn.00239.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephan KE, Harrison LM, Kiebel SJ, David O, Penny WD, & Friston KJ (2007). Dynamic causal models of neural system dynamics: Current state and future extensions. Journal of Biosciences, 32, 129–144. 10.1007/s12038-007-0012-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephan KE, Kasper L, Harrison LM, Daunizeau J, den Ouden HE, Breakspear M, & Friston KJ (2008). Nonlinear dynamic causal models for fMRI. NeuroImage, 42, 649–662. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.04.262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephan KE, Penny WD, Moran RJ, den Ouden HE, Daunizeau J, & Friston KJ (2010). Ten simple rules for dynamic causal modeling. NeuroImage, 49, 3099–3109. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.11.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suryanarayana SM, Hellgren Kotaleski J, Grillner S, & Gurney KN (2019). Roles for globus pallidus externa revealed in a computational model of action selection in the basal ganglia. Neural Networks, 109, 113–136. 10.1016/j.neunet.2018.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajima S, Drugowitsch J, Patel N, & Pouget A (2019). Optimal policy for multi-alternative decisions. Nature Neuroscience, 22, 1503–1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tecuapetla F, Jin X, Lima SQ, & Costa RM (2016). Complementary contributions of striatal projection pathways to action initiation and execution. Cell, 166, 703–715. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.06.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tecuapetla F, Matias S, Dugue GP, Mainen ZF, & Costa RM (2014). Balanced activity in basal ganglia projection pathways is critical for contraversive movements. Nature Communications, 5, 4315. 10.1038/ncomms5315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapp S, Schroll H, & Hamker FH (2012). Open and closed loops: A computational approach to attention and consciousness. Advances in Cognitive Psychology, 8, 1–8. 10.5709/acp-0096-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaillancourt DE, Mayka MA, Thulborn KR, & Corcos DM (2004). Subthalamic nucleus and internal globus pallidus scale with the rate of change of force production in humans. NeuroImage, 23, 175–186. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.04.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vicente AM, Galvao-Ferreira P, Tecuapetla F, & Costa RM (2016). Direct and indirect dorsolateral striatum pathways reinforce different action strategies. Current Biology, 26, R267–R269. 10.1016/j.cub.2016.02.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White TP, Engen NH, Sorensen S, Overgaard M, & Shergill SS (2014). Uncertainty and confidence from the triple-network perspective: Voxel-based meta-analyses. Brain and Cognition, 85, 191–200. 10.1016/j.bandc.2013.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yttri EA, & Dudman JT (2016). Opponent and bidirectional control of movement velocity in the basal ganglia. Nature, 533, 402–406. 10.1038/nature17639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J-C, Fiore VG, Briggs RW, Braud J, Rubia K, Adinoff B, & Gu X (2020). An insula-driven network computes decision uncertainty and promotes abstinence in chronic cocaine users. European Journal of Neuroscience, 52, 4923–4936. 10.1111/ejn.14917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Single-subject GLM results and associated DCM estimations are available in the public repository G-Node (DOI: 10.12751/g-node.rmb9z3).