SUMMARY

Effort valuation—a process for selecting actions based on the anticipated value of rewarding outcomes and expectations about the work required to obtain them—plays a fundamental role in decision-making. Effort valuation is disrupted in chronic stress states and is supported by the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), but the circuit-level mechanisms by which the ACC regulates effort-based decision-making are unclear. Here, we show that ACC neurons projecting to the nucleus accumbens (ACC-NAc) play a critical role in effort valuation behavior in mice. Activity in ACC-NAc cells integrates both reward- and effort-related information, encoding a reward-related signal that scales with effort requirements and is necessary for supporting future effortful decisions. Chronic CORT exposure reduces motivation, suppresses effortful reward-seeking, and disrupts ACC-NAc signals. Together, our results delineate a stress-sensitive ACC-NAc circuit that supports effortful reward-seeking behavior by integrating reward and effort signals and reinforcing effort allocation in the service of maximizing reward.

eTOC

Fetcho, Parekh et al. show how anterior cingulate-to-nucleus accumbens projecting neurons integrate reward and effort information to support future effortful choices. They show that motivational anhedonia following chronic stress may be driven in part by a disruption in the effort-sensitive reward activity of this circuit.

INTRODUCTION

Decisions to allocate effort in pursuit of rewards play a fundamental role in shaping a variety of behaviors across organisms 1, but the mechanisms regulating effort-based decision-making are incompletely understood. Anhedonia—a core feature of depression 2–8, addictions, and other stress-related psychiatric disorders 9–13—encompasses a variety of deficits in effortful reward-seeking behavior and hedonic function. Anhedonia can be caused by a loss of pleasure in previously rewarding activities (“consummatory anhedonia”), by altered expectations about the rewards associated with a future event (“anticipatory anhedonia”), or by deficits in effort allocation and motivation. Pioneering studies have identified dissociable neural systems underlying consummatory and anticipatory forms of anhedonia in both rodents 14–16 and humans 17–19. In contrast, our understanding of the neural circuits that shape hedonic processing by encoding effort signals and regulating an individual’s willingness to expend effort to obtain a reward is less well developed.

Theoretical models of effort-based decision-making posit the involvement of multiple brain regions and circuits encoding different types of effort signals and outcomes for regulating behavior to maximize reward 20,21. Converging empirical data from multiple species suggests that the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) plays a critical role in this process 22–24. Neuroimaging and behavioral experiments in humans and non-human primates indicate that ACC represents information related to action valuation – a process for selecting actions based upon the relative expected value of various action/outcome contingencies25,26. ACC dysfunction is a consistent finding in neuroimaging studies of depression 27–30 and has been linked to deficits in salience attribution and abnormal reward-seeking behavior in addictions 31. ACC lesions in neurological patients produce a variety of deficits in motivation and effort ranging from apathy and abulia to akinetic mutism 23,32–34. Similarly, in rats and non-human primates, ACC lesions disrupt cost-benefit decision-making and have a pronounced and specific effect on effortful reward-seeking 35,36, such that lesioned individuals still pursue rewards but they tend to favor low-effort / low-reward actions over more effortful actions associated with larger rewards.

The underlying mechanisms by which the ACC regulates effort-based decision-making and reward-seeking—what kind of information is being represented and how it shapes decision-making—are not well understood, especially at the level of neural circuits. Calcium imaging and electrophysiological studies have shown that ACC and medial prefrontal cortical neurons represent reward-related information, including reward value, reward prediction errors, and reward-predictive cues in the environment 37–39. They encode a continuously updated representation of action outcomes to support flexible reward-seeking behavior 40, and they also predict the consequences of actions, monitoring for deviation from those predictions to maximize rewards 41. Together, these studies have established a critical role for ACC neurons in representing various reward-related information. Whether and how ACC cells also encode effort signals and use them to influence decision-making is not as well understood. ACC activity varies with locomotor effort (running, lever pressing) during active reward-seeking 42,43, and in extracellular recordings, a subset of ACC neurons exhibit activity that is correlated with both effort expenditures and rewards 44–46. These studies did not evaluate whether effort signals in ACC are required specifically for supporting effortful reward-seeking. But in conjunction with the ACC lesion results reviewed above, they suggest that ACC neurons are well positioned to guide decision-making by integrating information about the availability of rewards in the environment and about the effort required to obtain those rewards. We set out to test this hypothesis by recording and manipulating the activity of ACC cells in an effortful reward-seeking task and evaluating whether they encode both reward and effort signals and regulate an individual’s willingness to allocate effort in pursuit of rewards.

Importantly, ACC cells are functionally heterogeneous, and it is also unknown whether projection neuron subtypes play specific roles in regulating effortful reward-seeking behavior through effects on specific downstream targets. The ACC sends abundant projections to the nucleus accumbens 47,48, which has been implicated in a variety of reward processing functions 49–51. In a Pavlovian conditioning task, medial prefrontal neurons that project to the nucleus accumbens show excitatory responses to reward-predictive cues, while thalamus-projecting neurons are inhibited 38, highlighting how the functional properties of medial prefrontal neurons vary by subtype and underscoring the importance of accumbens-projecting neurons in representing reward signals. Whether accumbens-projecting ACC cells encode both reward- and effort-related signals is unknown, but lesion studies indicate that both areas are necessary for supporting effortful reward-seeking 52.

By extension, dysfunction in ACC-NAc neurons may also disrupt effortful reward-seeking in chronic stress states. Although this has not been tested directly, previous studies have shown that both prefrontal cortex and nucleus accumbens are susceptible to stress-induced changes in function that disrupt other types of behavior 53–60. In at least one recent study, effortful reward-seeking behavior was disrupted in a chronic CORT model of the neuroendocrine response to stress 61, but it remains unclear whether these deficits are related specifically to ACC dysfunction. We hypothesized that ACC-NAc neurons play a critical role in regulating effortful reward-seeking behavior by encoding effort signals and reinforcing effort allocation in the service of maximizing reward, and that disruptions in ACC-NAc cell activity underlie effortful reward-seeking deficits in chronic stress states.

To test this, we developed an automated effort-based decision-making paradigm for mice and used it to investigate how ACC-NAc cells support effortful reward-seeking behavior. Using fiber photometry and optogenetic techniques to record and manipulate the activity of ACC-NAc cells in freely moving mice, we found that ACC-NAc cells integrate both reward and effort information, encoding a reward-related signal that scales with effort requirements. By optogenetically suppressing ACC-NAc activity in specific task epochs, we found that this effort-modulated reward response is necessary for supporting future effortful decisions. Chronic CORT exposure—a model of the neuroendocrine response to chronic stress—reduces motivation, suppresses effortful reward-seeking, and disrupts ACC-NAc signals in this task.

RESULTS

Validating an automated, physiology-compatible effort-based decision-making task

We began by developing an effort-based decision-making task for freely moving mice, adapting an established paradigm in rats 36 to allow for automated, high-throughput assessments of reward-seeking behavior and effort-based decision-making that is easily compatible with photometry and optogenetics. In this task, mice learn to navigate in a ‘T’ maze to receive rewards. On each trial, they are presented with a choice to turn left or right to obtain a large or small reward (plain water of varying volume). After learning this contingency, an individual’s willingness to expend effort for a larger reward is evaluated by introducing a physical barrier that must be climbed to obtain the high-reward option (Fig. 1A, Supplementary Fig. 1A–C). To summarize the training procedure briefly (see Methods for details), we first habituated mice to the apparatus and then trained them to self-initiate trials by returning to the start zone in the ‘T’ maze (Fig. 1A). Next, mice were trained through a series of session types based upon the amount of effort needed to acquire the high-reward option: no-effort, low-effort and high-effort (Fig. 1B). On each session, reward-seeking behavior was quantified as the percentage of high-reward choices during a session. The relative value of the high and low-rewards (the reward ratio) was independently calibrated for each mouse to promote preference for the high-reward option. When the high-reward option was chosen on more than 70% of trials for two sessions in a row, animals progressed to the next type of session (effort condition). We found that with individualized adjustments to the reward ratio, mice that initially chose not to expend effort for a larger reward would adjust their behavior, as the relative value of the high-reward increased, and eventually reach the training criterion (Fig. 1C,D). On average, mice achieved the learning criteria for the no-effort, low-effort, and high-effort components of training over approximately 15 days (~5–6 days per session type, see Supplementary Fig. 1D–G for additional training data). Importantly, we found that as effort levels increased, animals required larger reward ratios to promote preference for the high-reward (Fig. 1E), confirming that they were integrating the relative value of both the reward options and the effort required to obtain them when making choices in this task.

Figure 1. Anterior cingulate cortex is necessary for decisions that require integration of different reward and effort values.

A. Schematic of effort-based decision-making behavioral apparatus.

B. Training structure showing progression from habituation to decision-making sessions.

C. Training trajectories from three example animals.

D. High-reward choice percentages on the final session of each effort type are significantly higher than on the first session of each effort type. N=51 mice from 4 experiments, Wilcoxon paired test ****p<0.0001 for no-effort, low-effort and high-effort.

E. Reward ratios needed to achieve criteria significantly increase with increasing levels of effort. N=48 mice from 4 experiments. One-way ANOVA (Friedman test) p<0.0001 F=67.12. Post-hoc Dunn’s test: no-effort vs. low-effort **p=0.0011; no-effort vs. high-effort ****p<0.0001; low-effort vs. high-effort **p=0.0011.

F. Schematic of infusion cannula placement into ACC.

G. Timeline for muscimol infusion experiment.

H. High-reward choice percentage was not significantly altered by infusion of PBS into ACC. N=10 mice from 1 experiment. Wilcoxon paired test p>0.99.

I. High-reward choice percentage dropped significantly from baseline with muscimol infusion into ACC prior to a low-effort session and returned to baseline levels the next day. N=8 mice from 1 experiment (2 mice excluded due to unsuccessful infusion). One-way ANOVA (Friedman test) p=0.0005 F=13.31. Post-hoc Dunn’s test: baseline vs. muscimol **p=0.01; muscimol vs post **p=0.0053; baseline vs post p>0.99.

J. Intertrial interval times increased significantly with muscimol infusion into ACC. N=8 mice from 1 experiment (2 mice excluded due to unsuccessful infusion). One-way ANOVA (Friedman test) p=0.0003 F=13.0. Post-hoc Dunn’s test: baseline vs. muscimol *p=0.03; muscimol vs post **p=0.001; baseline vs post p=0.95.

K. High-reward choice percentage was not altered on equal effort sessions with infusion of muscimol into ACC. N=8 mice from 1 experiment (2 mice excluded due to unsuccessful infusion). Wilcoxon paired test p=0.5. All bar plots here and in future figures represent the mean +/− S.E.M.; grey lines represent individual animals’ data points.

Next, we sought to determine whether the mouse ACC is playing a necessary role in this decision-making process, in accord with previous lesion studies implicating ACC in a variety of tasks involving effort-based decision-making and cost-benefit analyses in rats 35,36. To test this, we infused the GABA agonist muscimol through surgically implanted infusion cannulae above the ACC (midway along the rostrocaudal axis) to disrupt the function of the region (Fig. 1F). Following 3 weeks of recovery, we trained these mice on the effort-based decision-making paradigm until they reached training criteria for low-effort sessions and then infused either phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or muscimol into the ACC prior to testing on subsequent days (Fig. 1G).

We found that while infusion of PBS had no impact on choice behavior (Fig. 1H), disrupting ACC function via muscimol infusion caused a large shift in behavior away from the effortful high-reward option, and favoring the low-reward choice (Fig. 1I). This disruption was transient: when mice were tested the following day without infusion, they again preferred to expend effort to obtain the larger reward. Interestingly, muscimol infusion (but not PBS) also led to increases in the latency to initiate trials (intertrial interval, Fig. 1J) as well as the time to complete them (trial duration, Supplementary Fig. 1H–J), consistent with a general amotivational state typically observed with ACC dysfunction 9. These results confirm that ACC function is acutely necessary for supporting effortful reward-seeking behavior and for optimizing decision-making to maximize reward, in line with previous work 36.

To evaluate the specificity of ACC function in integrating both reward and effort values, we performed a control experiment in which we equalized the effort required for both the low- and high-reward options such that the choice became one of reward discrimination. We found that when the effort variable was eliminated from the decision-making process, the ACC was no longer necessary: muscimol infusion had no impact on high-reward choice behavior (Fig. 1K). Importantly, muscimol did increase trial durations and intertrial intervals in this condition (Supplementary Fig. 1K), confirming that ACC was indeed disrupted during this control experiment, but there was no effect on decision-making. Together, these results confirm that our effort-based decision-making paradigm requires integration of relative effort and reward values when making choices, and that ACC plays a critical role in supporting decisions to expend effort to obtain larger rewards.

ACC-NAc activity encodes a reward-related signal that is insensitive to reward magnitude

ACC cells are functionally heterogeneous, and their functional properties have been shown to vary with their projection targets 38,62,63. Whether specific ACC neuronal subtypes encode effort-related signals and whether these signals influence decision-making through projections to various downstream targets is unknown. While the ACC has extensive connectivity with many regions 47,48,64, converging data suggest that the ACC projection to the nucleus accumbens (ACC-NAc cells) is a likely candidate for this role: previous studies have shown that NAc-projecting mPFC cells encode reward-predictive cues 38 and that lesions of the ACC and NAc, particularly the core subregion, disrupt effortful reward-seeking in rats 52. The core and shell subregions of the NAc are known to have differential connectivity and support divergent aspects of salience and hedonic value in reward processing and the ACC has been shown to send a clear projection to the NAc core 65,66. To investigate the role of this frontostriatal circuit in effort-based decision-making, we used fiber photometry 67 to record the activity of ACC cells projecting primarily to accumbens core as animals performed our behavioral paradigm (Fig. 2A; Supplementary Fig. 2A). To this end, we injected a retrograde viral vector containing Cre-recombinase into the nucleus accumbens (AAVrg-Cre) and a Cre-inducible genetically encoded calcium indicator (AAV1-Syn-FLEX-GCaMP6s-WPRE) into ACC. We then implanted an optical fiber over ACC to record from cells expressing GCaMP6s during effort-based decision-making behavior (Fig. 2B; Supplementary Fig. 2A).

Figure 2. ACC-NAc activity encodes a reward-related signal that is insensitive to reward magnitude.

A. Schematic of behavioral apparatus with behavioral timepoints of interest.

B. Schematic of strategy for fiber photometry. Image inset: Representative histological image of ACC showing GCaMP6s expressing cell bodies (green) in ACC with fiber optic implant.

C. Example of ACC-NAc activity during a no-effort behavioral session at criterion performance.

D. Average traces of ACC-NAc activity time-locked to behaviors of interest during no-effort sessions at criterion performance. N=16 mice from 3 experiments; trial start 920 trials, decision approach 926 trials, reward approach 905 trials, reward acquisition 896 trials. This and future traces show mean signal with shaded 95% confidence interval.

E. Average trace of ACC-NAc activity time-locked to either high (red) or low (blue) reward acquisition during the first day of no-effort session training. N=16 mice, 3 experiments; high-reward 143 trials, low-reward 231 trials.

F. Left: Heat map showing ACC-NAc activity time-locked to reward acquisition for low- and high-reward trials during no-effort sessions at criterion performance. Each row represents the average signal of an individual animal (N=16 mice, 3 experiments). Right: Average trace of ACC-NAc activity time-locked to either high (red) or low (blue) reward acquisition during no-effort sessions at criterion performance. N=16 mice, 3 experiments; high-reward 598 trials, low-reward 298 trials.

To test whether ACC-NAc cells encode reward signals independent of effort, we first recorded their activity during no-effort sessions, in which task choices are driven by simple reward discrimination. We identified four behavioral epochs of interest that occur during the course of a trial—trial start, decision approach, reward approach, and reward acquisition (Fig. 2A)—and quantified ACC-NAc activity around these periods (Fig. 2C). We found that the largest changes in activity occurred in relation to the approach and acquisition of reward (Fig, 2D). We hypothesized that ACC-NAc cells may convey information regarding relative reward values, scaling with reward magnitude, which could be important for regulating decision-making. To test whether ACC-NAc activity scaled with reward magnitude, we compared activity in this projection on high- vs. low-reward trials during no-effort behavioral sessions. On the first day of training, when animals were not yet preferring the optimal, high-reward choice, we observed increased ACC-NAc activity on high-reward trials compared to low-reward trials (Fig. 2E), suggesting that this circuit may be important for encoding relative reward values early during training and facilitating learning. We also quantified activity during later sessions, when the mice had learned the relative reward values, as evidenced by the fact that they were performing at criterion (preferring high-reward choices). Unexpectedly, during sessions at criterion, we observed similar levels of ACC-NAc activity during reward acquisition on high- and low-reward trials (Fig. 2F; Supplementary Fig. 2B). This indicates that while the ACC-NAc circuit responds to reward acquisition, it is sensitive to reward magnitude only early during training and not after significant experience.

Moreover, we observed no overall relationship between reward ratio magnitude and ACC-NAc activity differences during training, further suggesting the reward signal is insensitive to reward magnitude in this context, in this case even as animals are learning changing reward values across all no-effort sessions (Supplementary Fig. 2C). We also observed ACC-NAc activity (albeit diminished) during licking of reward ports when reward was unexpectedly omitted on a subset of trials and these dynamics were similarly insensitive to expected reward magnitude (Supplementary Fig 2D). We did observe a negative correlation between animal velocity and circuit activity during the task, explained in part by the fact that the mice are relatively immobile during reward acquisition (Supplementary Fig. 2E,F). Importantly, in an alternative context, when animals were free to explore an open field, we saw no relationship between velocity and signal level (Supplementary Fig. 2G), lending further support to a reward-related signal that is not confounded by non-specific locomotor activity in the task. Together, our data indicate that early in training, ACC-NAc activity encodes reward values, which may facilitate learning; however, following learning, ACC-NAc activity continues to respond to reward but does not appear to simply encode the value of reward alone. These results are in line with prior work68 as well as our muscimol experiments (Fig. 1F–K) that indicate ACC is not necessary for pure reward discrimination.

Reward-related signals in ACC-NAc cells are modulated by prior effort and support effortful reward-seeking

Together, the results above indicate that ACC does not solely mediate reward discrimination but is required for allocating effort to maximize rewards. Given this, we next asked whether ACC-NAc cells encode effort-related information during the task and specifically, given the observed reward-related response, whether this effort information is integrated into the reward-related activity or if it arises separately, perhaps prior to the decision point. To test this, we again recorded from ACC-NAc cells, this time during low- and high-effort sessions, focusing our analysis on the same four behavioral epochs of interest related to the approach and acquisition of reward (Fig. 3A,B). We observed a large and highly consistent increase in ACC-NAc activity on effortful high-reward trials that was time-locked to the end of effort expenditure, when animals reached the top of the barrier and began their descent to the reward (Fig. 3C; Supplementary Video 1). Furthermore, in contrast to no-effort sessions, we observed significantly higher levels of reward-related activity in ACC-NAc cells on effortful high-reward trials, compared with low-reward trials, even in well-trained mice performing at criterion (Fig. 3D–F). Importantly, we also found that ACC-NAc activity levels were significantly elevated on high-effort sessions compared with low-effort sessions (Fig. 3F; Supplementary Fig. 3A,B). These effort-related signal differences were already present on the first session of a given effort level, suggesting that these differences are not arising due to learning across many sessions (Supplementary Fig. 3C). These signal differences were not driven by differences in velocity as animals descended the ramps, since overall animal velocity was lower on high-reward approach than low-reward approach (Supplementary Fig. 3D,E) nor was there any correlation between acceleration and photometry signal (Supplementary Fig. 3F). To evaluate the specificity of the NAc projecting ACC cell population in mediating effortful reward-seeking behavior, we compared its activity in our task against two other distinct ACC neural populations – basolateral amygdala projecting neurons and somatostatin-positive (SST) interneurons (Supplementary Fig 3K, R). Both the BLA itself and connectivity between the BLA and ACC have been implicated in effort and reward based decision-making69–71. We found that while the ACC-BLA circuit shows similar reward-related activity in our task, modulation by effort was less pronounced (Supplementary Fig. 3K–Q). We also compared the activity of these projection populations to the local ACC SST interneuron population, which we reasoned may be well situated to regulate ACC function in our task via dynamic modulation of inputs onto ACC pyramidal neurons72. We found that SST cells on a population level responded minimally to reward acquisition and effort requirements (Supplementary Fig. 3R–T). Overall, ACC-NAc circuit activity showed significantly greater effort-modulated reward activity when compared to these alternative ACC neural population (Supplementary Fig. 3U), suggesting a unique role for the NAc projecting neurons of the ACC. All together, our data indicate that while ACC-NAc activity responds to reward acquisition, the magnitude of this response is modulated not by reward magnitude but rather by the level of effort that was necessary to acquire the reward. Thus, ACC-NAc activity encodes information related to both reward and effort simultaneously.

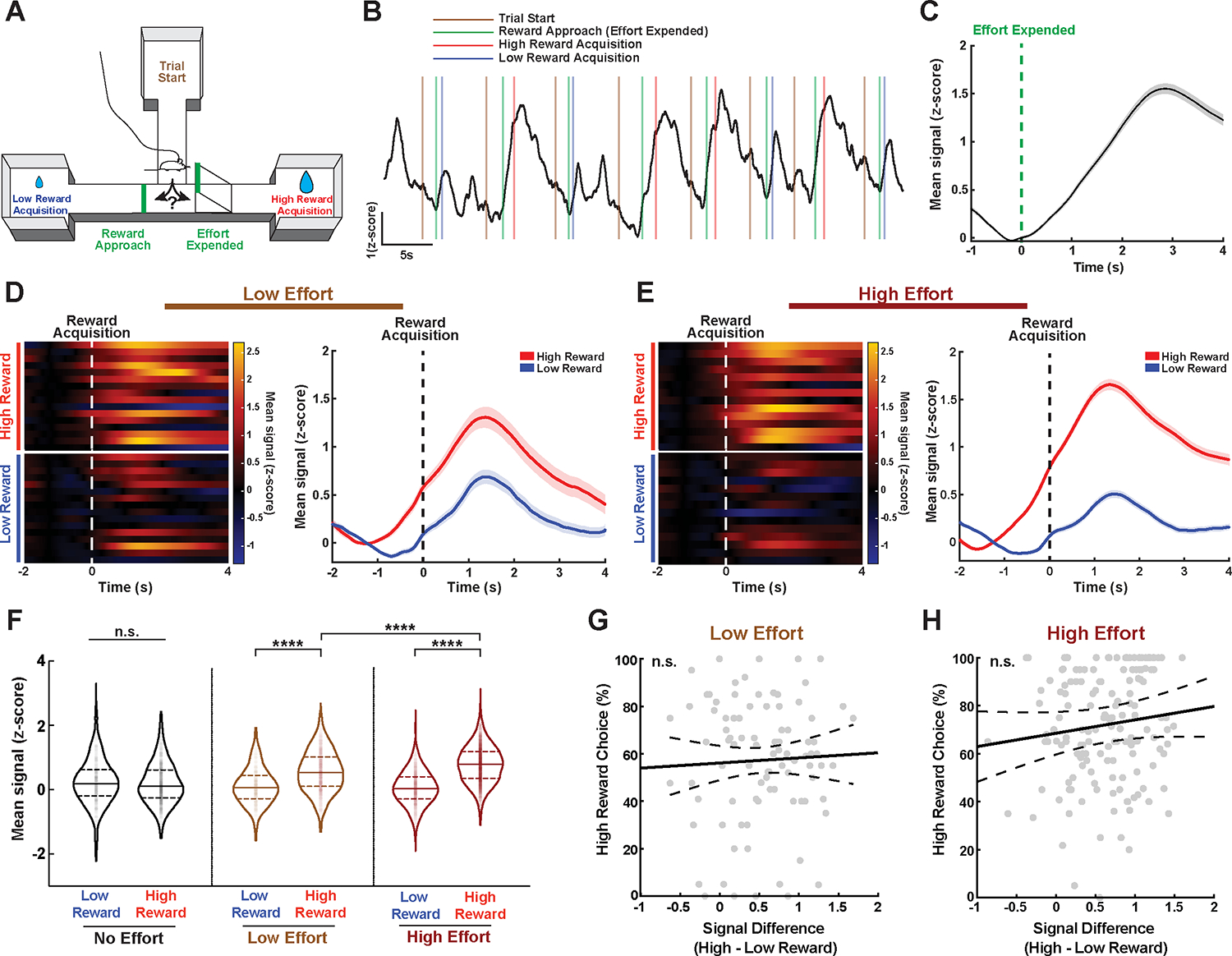

Figure 3. Reward-related signals in ACC-NAc cells are modulated by prior effort.

A. Schematic of behavioral apparatus with behavioral timepoints of interest.

B. Example of ACC-NAc activity during a high-effort behavioral session.

C. Average trace of ACC-NAc activity time-locked to the end of effort expenditure (top of barrier) on high-reward trials during effort sessions. N=16 mice, 3 experiments, 2457 trials.

D. Left: Heatmap showing ACC-NAc activity time-locked to reward acquisition for low- and high-reward trials during low-effort sessions. Each row represents the average signal of an individual animal. Right: Average trace of ACC-NAc activity time-locked to either high (red) or low (blue) reward acquisition during low-effort sessions at criterion performance. N=16 mice, 3 experiments; high-reward 646 trials, low-reward 314 trials.

E. Left: Same as D but for high-effort sessions. Right: Same as D but for high-effort session. N=15 mice (one animal did not reach high-effort sessions), 3 experiments; high-reward 1804 trials, low-reward 724 trials.

F. Mean ACC-NAc signal during reward acquisition for low- and high-reward trials across all effort types at criterion performance. There was no significant difference in mean activity between low- and high-reward trials during no-effort sessions; however, there was a significant difference between low- and high-reward trials during low- and high-effort sessions. Furthermore, mean signals on high-reward trials during high-effort sessions were significantly greater than during low-effort sessions. N=16 mice, 4384 trials from 3 experiments. Linear mixed effect model - ANOVA marginal test, significant interaction between reward type and effort level F(2,4378)=135.38 ****p<0.0001. Post-hoc testing of coefficients: no-effort: low- vs. high-reward F=1.56 p=0.211; low-effort: low- vs. high-reward F=135.2 ****p<0.0001; high-effort: low- vs. high-reward F=846.7 ****p<0.0001; high-reward: low- vs. high-effort F=35.48 ****p<0.0001.

G. Scatterplot indicating no significant relationship between ACC-NAc high- vs. low-reward signal difference and behavioral performance during low-effort sessions. Solid line indicates predicted relationship between variables from model, dotted lines indicate confidence bands for predicted relationship. N=16 mice, 92 sessions from 3 experiments. Linear mixed effects model T(90)=0.45 p=0.66, R2 (with and without random effect)=0.0022.

H. Same as G but for high-effort sessions. N=15 mice, 155 sessions from 3 experiments. Linear mixed effects model T(153)=1.43 p=0.16, R2 (with random effect)=0.24, R2 (without random effect)=0.021.

To better understand how ACC-NAc cells influence behavior, we next asked whether ACC-NAc activity during low- and high-effort sessions varied with task performance over the course of training. Interestingly, we observed no significant correlation between the percentage of high-reward choices and the relative difference in high- and low-reward activity in ACC-NAc cells (Fig. 3G,H). Instead, the circuit was consistently more active on effortful high-reward trials compared with low-reward trials, regardless of the behavioral outcomes. There was also no significant correlation between signal differences and either reward ratio or day of training (Supplementary Fig. 3G–J). This suggests that the ACC-NAc circuit is not single-handedly driving behavioral outcomes on a trial-by-trial basis in this task. Instead, we hypothesized that elevated ACC-NAc activity on effortful high-reward trials may be important for promoting the continued willingness to exert effort to obtain rewards on future trials.

To test this hypothesis, we performed an optogenetic silencing experiment to suppress ACC-NAc activity during specific task epochs. To this end, we injected a retrograde viral vector containing Cre-recombinase bilaterally into the nucleus accumbens (AAVrg-Cre) and a Cre-inducible soma-targeted anion-conducting channelrhodopsin73–75 (AAV1-hSyn-SIO-stGtACR2-FusionRed) bilaterally into ACC in order to express this inhibitory opsin specifically in ACC neurons projecting to NAc. We then implanted a bilateral fiber over ACC to permit opsin activation during specific behavioral epochs (Fig. 4A,B; Supplementary Fig. 4A). We trained these animals to criterion on high-effort sessions and then on the next high-effort session, we silenced ACC-NAc activity during the post-effort period on high-reward trials, i.e. starting when the animals have finished climbing the barrier and stopping when they acquired the reward (Fig. 4B). We found that silencing ACC-NAc cells during this period led to a significant reduction in effortful high-reward choices on future trials within that session (Fig. 4C), an effect that was not observed in a control group expressing AAV1-GFP and was temporally restricted to the optogenetic inhibition session, such that effortful high-reward responding returned to baseline in the next session. Silencing ACC-NAc cells did not alter intertrial interval times, although it did lead to elevated high-reward trial durations (Fig. 4D; Supplementary Fig. 4B,C). When examining this effect on a per trial basis, there was no apparent “accumulation” effect of inhibition across a session (Supplementary Fig. 4D). However, we found that the previous trial’s outcome was predictive of the likelihood of an effortful high-reward choice on the current trial, such that ACC-NAc inhibition during a given high-effort, high-reward trial reduced the probability of high-effort responding on the subsequent trial (Supplementary Fig. 4E–G). Critically, ACC-NAc inhibition in sessions consisting of equalized effort or no-effort both had no effect on choice behavior (and did not impact total trials completed), indicating that this circuit is critical specifically for supporting decisions that involve both reward and effort integration (Fig. 4E,F; Supplementary Fig. 4H–M). Also, in line with our photometry results, silencing ACC-NAc cells during the pre-effort period did not have any effect on future choice behavior or any other measures of motivation (Fig. 4G; Supplementary Fig. 4N–P). Interestingly, inhibiting ACC-NAc only during the reward acquisition period led to a variable but non-significant effect on high-reward choice (Supplementary Fig. 4Q–T). This suggests that while the ACC-NAc signal begins following effort expenditure, prior to reward acquisition, its persistence into the reward period likely plays an important part in the behavioral consequences of supporting effortful choice. Together, these results indicate that ACC-NAc activity specifically encodes reward acquisition, is modulated by the level of effort that was needed to acquire the reward and is critical for supporting future decisions to expend effort to obtain larger rewards.

Figure 4. ACC-NAc activity supports future effortful decisions.

A. Schematic of strategy for optogenetic silencing of the ACC-NAc population. Image inset: Representative histological image of ACC showing bilateral stGtACR2 expressing cell bodies (red) in ACC with dual fiber optic implant.

B. Schematic of optogenetic silencing experiments.

C. Silencing of ACC-NAc following effort led to a significant reduction in effortful high-reward choices within the session. Two-way repeated measures ANOVA, N=29 mice (16 control, 13 experimental), 3 experiments. Significant interaction F(2,54)=10.49 p=0.0001. Post-hoc Bonferonni testing control: baseline vs. stim p=0.60; stim vs. post p>0.99, experimental: baseline vs. stim ****p<0.0001; stim vs. post ****p<0.0001

D. Silencing of ACC-NAc following effort did not alter intertrial interval times. Two-way repeated measures ANOVA, N=29 mice (16 control, 13 experimental), 3 experiments. No significant interaction F(1,27)=1.11 p=0.30.

E. Silencing of ACC-NAc following effort on high-reward choices during an equal effort session did not alter high-reward choice behavior. Two-way repeated measures ANOVA, N=10 mice (4 control, 6 experimental), 1 experiment. No significant interaction F(1,8)=1.96 p=0.20.

F. Silencing of ACC-NAc on high-reward choices during a no-effort session did not alter high-reward choice behavior. Two-way repeated measures ANOVA, N=14 mice (5 control, 9 experimental), 1 experiment. No significant interaction F(1,12)=0.1 p=0.7.

G. Silencing of ACC-NAc prior to effort did not alter high-reward choice behavior. Two-way repeated measures ANOVA, N=10 mice (4 control, 6 experimental), 1 experiment. No significant interaction F(1,8)=0.39 p=0.55.

Chronic CORT disrupts effortful reward-seeking and ACC-NAc function

Anhedonia is a core feature of depression and other stress-related psychiatric disorders, but the mechanisms are not well understood. Previous studies have shown that chronic stress disrupts reward-seeking behavior in rodents 2,16,76, but most studies have focused on consummatory hedonic functions (e.g. sucrose preference) and the underlying circuit-level mechanisms are not well defined. Of note, ACC cells are sensitive to chronic stress, undergoing dendritic retraction and synapse loss in chronic stress states 53,60,77,78. We hypothesized that chronic stress interferes with hedonic function by impairing ACC-NAc circuit activity and disrupting effortful reward-seeking. To test this, we trained a cohort of animals to criterion on high-effort sessions. Following training, we exposed these animals to a vehicle solution or corticosterone (0.1 mg/mL) in their drinking water for 21 days—a well-established model of the neuroendocrine response to chronic stress 79 that induces stress-related behavioral impairments 80,81. We tested these animals on high-effort behavioral sessions before and after chronic corticosterone treatment (Fig. 5A).

Figure 5. Chronic CORT alters effort-based decision-making and impairs ACC-NAc circuit function.

A. Timeline for chronic corticosterone behavioral experiment.

B. Chronic corticosterone treatment led to significantly reduced high-reward choices compared to a vehicle group. Two-way repeated measures ANOVA, N=25 mice (9 vehicle, 16 corticosterone), 2 experiments. Significant interaction F(2,46)=24.09 p<0.0001. Post-hoc Bonferonni testing, baseline: vehicle vs. Cort p>0.99, day 1 post treatment: vehicle vs Cort ****p<0.0001, day 2 post treatment: vehicle vs. Cort ****p<0.0001.

C. Chronic corticosterone treatment led to significantly increased high-reward trial durations compared to a vehicle group. Two-way repeated measures ANOVA, N=25 mice (9 vehicle, 16 corticosterone), 2 experiments. Significant interaction F(2,46)=12.51 p<0.0001. Post-hoc Bonferonni testing, baseline: vehicle vs. Cort p>0.99, day 1 post treatment: vehicle vs Cort ****p<0.0001, day 2 post treatment: vehicle vs. Cort **p=0.0013.

D, Chronic corticosterone treatment led to significantly reduced high-reward choices on high-effort sessions but high-reward choices remained at baseline levels on equal effort and no-effort sessions following corticosterone treatment. N=9 mice from 1 experiment. Mixed effects model, significant effect of session F(1.69,12.97)=29.54 p<0.0001. Post-hoc Bonferonni testing, baseline vs. high-effort **p=0.0013.

E. Average traces of ACC-NAc activity time-locked to reward acquisition on high-effort sessions following vehicle treatment. N=5 mice from 2 experiments (a subset of animals from B,C); high-reward 196 trials, low-reward 105 trials.

F. Average traces of ACC-NAc activity time-locked to reward acquisition on high-effort sessions following corticosterone treatment in animals with above 35% high-reward choice. N=5 mice from 2 experiments (a subset of animals from B,C); high-reward 88 trials, low-reward 83 trials.

G. Average traces of ACC-NAc activity time-locked to reward acquisition on high-effort sessions following corticosterone treatment in animals with below 35% high-reward choice. N=5 mice from 2 experiments (a subset of animals from B,C); high-reward 52 trials, low-reward 118 trials.

H. Scatterplot indicating no significant relationship between ACC-NAc high vs. low-reward signal difference and behavioral performance during high-effort sessions in the vehicle group. Solid line indicates predicted relationship between variables from model, dotted lines indicate confidence bands for predicted relationship. N=5 mice, 10 sessions from 2 experiments. Linear mixed effects model T(8)=1.77 p=0.11, R2 (with random effect)=0.8, R2 (without random effect)=0.06.

I. Same as H but showing a significant relationship for the corticosterone group. N=5 mice, 10 sessions from 2 experiments. Linear mixed effects model T(10)=4.56, **p=0.002, R2 (with and without random effect)=0.72. (Note: a model combining treatments (vehicle, CORT) indicated a significant interaction between signal and type of treatment on predicting behavioral performance (T(16)=−2.4, p=0.02) leading to modeling these groups individually in panels H and I).

We confirmed that the chronic corticosterone model reliably induced a state of increased serum corticosterone levels (Supplementary Fig. 5A), mimicking one aspect of the neuroendocrine response to stress, with serum corticosterone levels comparable to physiological levels induced by an acute stressor in most individuals, albeit with some individuals showing supraphysiological levels. This model led to a substantial reduction in the willingness of animals to expend effort for the high-reward option, compared to the vehicle control group (Fig. 5B). We also observed increases in trial durations following chronic corticosterone treatment, with no significant changes in intertrial intervals (Fig. 5C; Supplementary Fig. 5B,C). Importantly, high-reward choice (and total completed trial number) was unaffected when we tested the animals in no-effort or equal-effort conditions (Fig. 5D). These results mirrored our muscimol experiments and suggest that chronic corticosterone exposure interferes with the optimal allocation of effort to maximize rewards. Our results are in line with recent work in which Dieterich and colleagues demonstrated that a chronic regimen of lower-dose corticosterone administration over a longer period reduces high-effort choice in a Y-maze barrier task 61. Given our results implicating ACC-NAc in supporting effort-based decision-making, and the established impact of chronic stress on ACC circuits and corticolimbic systems 53,60,77,78, we hypothesized that motivational anhedonia in chronic stress states may be driven in part by dysfunction in ACC-NAc activity.

To test this, we recorded from ACC-NAc cells during high-effort test sessions following chronic corticosterone treatment and tested for effects on the effort-modulated reward signal that we characterized in Fig. 3. We found that in contrast to vehicle control animals, the reward signal in ACC-NAc cells was markedly reduced in corticosterone-treated mice (Fig. 5E–G). In vehicle control mice, we observed an increase in ACC-NAc activity that was time-locked to reward acquisition and was larger on high-effort / high-reward trials, replicating our findings from Fig. 3 (Fig. 5E). In contrast, in corticosterone-treated mice, we observed a blunted ACC-NAc response during sessions in which animals maintained some degree of effortful high-reward choices (greater than 35% of trials), especially during high-reward trials (Fig. 5F). These effects were even more pronounced during the sessions with the most significant behavioral impairments (less than 35% high-reward choices): in these sessions, ACC-NAc activity failed to differentiate high- vs. low-reward trials (Fig. 5G).

In addition to visualizing signal from these two behavioral categories, we investigated whether individual differences in high-reward choice behavior were related to ACC-NAc activity levels following corticosterone treatment. In contrast to our training data in mice untreated with corticosterone (Fig. 3G,H), in this experiment we now found a strong, significant correlation between effortful high-reward choices and the difference in ACC-NAc signal between high- and low-reward trials (Fig. 5H,I). Specifically, the largest ACC-NAc activity differences occurred during sessions in which animals were most willing to expend effort for large rewards. These results support a link between stress-induced impairments in effort-based decision-making and dysfunction in ACC-NAc activity. In parallel to our optogenetic experiment, disruption of effort-modulated reward-related ACC-NAc activity, here via chronic corticosterone exposure, led to reduced effortful high-reward choices.

DISCUSSION

Effort valuation plays a fundamental role in decision-making, and there is increasing interest in the role of effort valuation and ACC dysfunction in depression, addictions, and other neuropsychiatric disorders. While an extensive body of work has identified roles for ACC and medial prefrontal cortical neurons in representing reward-related information, our understanding of the circuit-level mechanisms by which the ACC represents effort-related signals and regulates effort-based decision-making and reward-seeking is not well developed. In this study, we developed and validated an automated, physiology-compatible platform for high-throughput assessments of effort valuation in freely moving mice and used it to elucidate how ACC circuits support effort valuation behavior and how these functions are disrupted in a chronic stress model. First, we confirmed that ACC neurons play a critical role in supporting effort valuation and effortful reward-seeking behavior. Of note, our results are consistent with several studies showing similar effects on effort-based decision-making after irreversible neurotoxic ACC lesions, 35,36,52 but this was not observed in one report in mice 82. This difference may be attributable to differences in the location of the lesion along the rostrocaudal axis (a more anterior location in Solinsky and Kirby, 2013), consistent with a large body of work showing heterogeneity in ACC function along both the rostrocaudal and dorsoventral axes 64.

Second, we showed that ACC-NAc cells support effort-based decision-making by integrating both reward- and effort-related information. Specifically, they encode a signal that responds to reward acquisition and scales with relative effort requirements. Third, we showed that this effort-sensitive, reward-related signal in ACC-NAc cells is required for supporting effort valuation and effort-based decision-making. Optogenetic silencing of this circuit following effort expenditure, but not before (and not if effort is absent or equalized), reduced future effortful reward-seeking, underscoring a specific role for this signal in shaping future behavior and reinforcing future effort allocation. Previous studies have defined various roles for ACC and medial prefrontal neurons in representing reward-related information, linking actions and outcomes, and monitoring for deviation from those predictions to maximize rewards 25,41,74,83,84. Our results show that ACC-NAc neurons shape future behavior not only by linking actions and outcomes but also by encoding an effort expenditure signal and linking it with reward.

Interestingly, we found that the reward signal in ACC-NAc neurons scaled with both effort expenditure and expectations of reward magnitude (high reward > low reward), but only early during learning. With extended task experience, this reward signal no longer differentiated high- vs. low-reward outcomes. This suggests that ACC-NAc neurons may be important for facilitating learning in this task by encoding relative reward values early during training. However, in accord with previous work 85, our equal-effort muscimol control data (Fig. 1K) indicate that ACC is not required for simple reward discrimination. An alternative interpretation is that initially during training in the “no-effort” sessions, selecting the high reward-option may require cognitive effort, despite the fact that there were no differences in physical effort expenditures (i.e. no physical barrier to climb). As described in more detail in the Methods, most individuals had an innate preference for one arm of the maze during the habituation phase, and we intentionally set the high-reward arm of the maze to be the non-preferred arm to control for these differences. Thus, overriding this innate preference may involve a form of cognitive effort analogous to the physical effort associated with climbing a barrier and may account for differences in the reward-related signal observed early during training—a question outside the scope of this work but addressable in future studies.

ACC-NAc cells encoded an effort-sensitive reward signal that preceded reward acquisition and coincided with effort expenditure and was required for reinforcing future effort expenditures to maximize reward. In contrast, we did not observe an increase in activity in this circuit time-locked to the decision to turn left or right, and optogenetic silencing during this task epoch had no effect on behavior. This indicates that ACC-NAc cells are not actively driving action selection or decision-making in the moment. These functions may reside in other ACC neuronal subtypes (e.g. ACC-amygdala projections 69,86) or other circuits 87, and future studies will be needed to elucidate this. Another limitation of our work was that it was not designed to investigate the coding properties of ACC cells at the single-cell level—an important question that could be addressed in future studies using microendoscopic techniques to investigate local population dynamics at a single-cell level within the ACC 43.

Finally, we showed that the ACC-NAc circuit is stress-sensitive and identified a circuit-level substrate for a specific form of motivational anhedonia in chronic stress states. Specifically, we found that chronic corticosterone exposure—a model of the neuroendocrine response to chronic stress—reduces motivation, suppresses effortful reward-seeking, and disrupts ACC-NAc signals. Of note, different stress paradigms present specific advantages for modeling aspects of anhedonia. Social stressors are often considered more “naturalistic” in rodent models and can induce many physiological and behavioral adaptations in depression-relevant circuits 88. A recent report 89 found that mice exposed to chronic social stress made fewer operant responses on a progressive ratio schedule to earn sweet rewards with low-effort/low-reward standard chow available as an alternative. This would suggest that chronic forms of neuroendocrine disruption and psychosocial stress appear to both impair motivated effortful behaviors. It will be important for future work to identify how chronic stress models differentially impact effortful reward-seeking and whether by similar or distinct neural mechanisms. Importantly, in our experiments, individual differences in ACC-NAc circuit function were strongly correlated with effortful reward-seeking after chronic corticosterone treatment. In individuals with moderate reductions in effort expenditure, a reward signal persisted and scaled with effort, but was reduced in magnitude. In individuals with the most pronounced reductions in effort expenditure, the reward signal was reduced by >50% and no longer scaled with effort. Future work should be done to investigate the potential for behavioral rescue of effortful choice by re-establishing ACC-NAc activity following stress-induced dysfunction. Overall, our data suggest that in individuals with the most pronounced stress effects on motivation and effortful reward-seeking, suboptimal effort allocation may be driven by a loss of this effort-sensitive reinforcement signal, which could be a promising target for therapeutic neuromodulation or antidepressant treatment.

STAR Methods

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead Contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Conor Liston (col2004@med.cornell.edu)

Materials Availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Data and Code Availability

The data reported in this paper will be shared by the lead contact upon reasonable request.

This study does not report original code. Fiber photometry acquisition and analysis code were based upon previously published work 67 (http://clarityresourcecenter.com/fiberphotometry.html).

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND STUDY PARTIPANT DETAILS

Adult (postnatal day 90–120) male wildtype C57Bl/6J (Jackson Laboratories) were used for all experiments. Mice were housed under climate-controlled conditions with a 12-hour light/dark cycle with ad-libitum access to food and water. During behavioral training and testing, water access was limited and animals were given a total of 1–1.5mL of water per day. All experimental procedures were approved by the Weill Cornell Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and in accordance with the Eighth Edition of the National Institutes of Health Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

METHOD DETAILS

Injection and Cannula Implantation

For surgical procedures, animals were anesthetized with 1.5% isoflurane and placed into a stereotax (Kopf Instruments). Following subcutaneous injection of bupivacaine, a midline incision was made in order to perform a small craniotomy using a dental drill to allow access for viral injection and/or cannula implantation. For muscimol infusion experiments, a bilateral guide cannula (PlasticsOne) was lowered into the anterior cingulate cortex (in mm) ML +/− 0.3, AP +1.2 from bregma and DV −0.5 from brain surface (an infusion cannula was inserted during experiments 0.25mm past the guide cannula for a total infusion depth of −0.75mm from surface). The guide cannula was fixed to the skull with dental cement (C&B Metabond Parkell Inc.). For fiber photometry ACC-NAc experiments, AAVrg-hSyn-Cre-WPRE-hGh (Addgene #105553-AAVrg) was injected into the nucleus accumbens at ML + 0.73, AP +1.42 from bregma and DV −4.7 from brain surface. AAV1-Syn-FLEX-GCaMP6s-WPRE (Penn Vector Core) was injected into ACC at ML +0.3, AP +1.2 from bregma and DV −0.75 from brain surface. A fiber optic cannula (Doric Lenses, 0.48NA 400um core) was lowered into ACC at ML +0.3, AP+1.2 from bregma and DV-0.55 from brain surface and fixed to the skull. For optogenetic inhibition experiments, AAVrg-hSyn-Cre-WPRE-hGh was injected bilaterally into the nucleus accumbens at ML +/− 0.73, AP +1.42 from bregma and DV −4.7 from brain surface. AAV1-hSyn-SIO-stGtACR2-FusionRed (Addgene # 105677) or AAV1-hSyn-DIO-mCherry (Addgene #50459-AAV1) was injected bilaterally into ACC at ML +/−0.3, AP +1.2 from bregma and DV −0.75 from brain surface. A bilateral fiber optic implant (Doric Lenses, 400um core 0.48 NA) was lowered into ACC at ML +/−0.3, AP +1.2 from bregma and DV −0.55 from brain surface and fixed to the skull. All injections utilized a 10uL Nanofil syringe (WPI) with a 33-gauge beveled needle using a microsyringe pump (UMP3, Micro4) to infuse 400nL of virus per location at a rate of 50nL per minute. Following infusion, the needle was kept at the injection site for another 10 minutes before being withdrawn. Behavioral training and testing began at least 2 weeks following surgery.

Effort-based Decision-making Behavioral Apparatus

A custom behavioral apparatus was constructed for automated behavior training and testing. The elevated T-maze apparatus consists of two reward arms (33cm long) and a central arm (25.4cm long) elevated by 22.8cm. The ends of each arm were enclosed on 3 sides by walls 14.6cm in height to minimize falling and permit dispensing of rewards (plain, autoclaved facility water). This maze apparatus was contained within a sound-proof box that permitted overhead entry of fiber optic patch cords. Effort barriers were custom 3D-printed plastic with handholds to aid climbing and descent (low-effort barrier – 5cm height, high-effort barrier 10cm height). These barriers (as well as 14cm smooth walls for forcing choices) were mounted onto stepper motors (Adafruit) for controlling their movement into the path of the animals. Water delivery via feeding needles mounted through the side walls was regulated by solenoid valves (The Lee Company). Trial start tones (5kHz) were played via a speaker located within the sound-proof box. IR sensors were utilized for determining animal location and detecting licking of the reward ports. An IR USB camera was mounted above the apparatus for recording videos of each behavioral session. Automated behavioral sessions were controlled by custom LabView (National Instruments) software on a laptop located outside of the sound-proof chamber and electronics were regulated via Arduino microcontrollers.

Effort-based Decision-making Behavioral Training

Animals group-housed in cages of 4–5, were water restricted 2–3 days prior to the beginning of training and permitted a total of 1mL of water daily, via behavioral sessions and in supplement following their daily session. Behavioral training occurred during the light phase. A habituation period consisted of sessions in which animals freely explored the T-maze apparatus with free access to water reward from either reward lick port. When water was acquired during this period, a 5kHz tone was played. Following 3 days of habituation, animals began training sessions to learn the task structure. Here, animals were required to enter the middle arm of the maze to initiate trials (the 5kHz tone now plays upon trial initiation) and then must traverse the middle arm and turn either left or right to acquire water reward from either lick port. Trials end either when animals acquired reward or after 20 seconds if reward was not acquired. All sessions began with 6 “forced” trials in which animals were forced to turn in either direction (3 trials per direction). The animals then performed up to 20 “choice” trials in which they are free to choose a reward arm. Every 5 choice trials, a reminder “forced” trial occurred, forcing the animals to turn the direction it has least preferred thus far during that session. Forced trials at the beginning of and intermittently during sessions were included to promote learning of reward and effort values and minimize habit formation by reminding animals of the alternative option. During initial training sessions, both reward arms offered equal volume of reward. Once animals were able to successfully complete all 20 choice trials within the session (maximum of 20 minutes per session) they moved on to “no-effort” sessions. During “no-effort” sessions, one reward arm offered a high-reward volume while the other offered a low-reward volume. These arms were chosen such that the high-reward arm was the arm least preferred by that mouse during training sessions. Initially, the ratio of high-reward volume to low-reward volume was 2:1. Animals underwent daily training sessions, with individualized adjustment of the reward ratio until they preferred the high-reward arm in 70% or more of trials within a session for two sessions in a row. Upon reaching this criterion, animals began “low-effort” training sessions, in which the high-reward arm was always paired with the low-effort barrier, requiring the animals to climb over this barrier to achieve the high-reward. Again, animals were trained daily and reward ratios adjusted until they preferred the high-reward option for 70% of trials or more within a session for two sessions in a row. Animals then began “high-effort” sessions, in which the high-reward arm was always paired with the high-effort barrier. Animals were trained to the 70% high-reward criterion for these high-effort sessions. Animals that did not achieve the criterion within the training period or that exceeded a reward ratio of 8 did not proceed with additional behavioral testing. Experiments were performed alongside this standard training protocol as described in individual sections below.

Muscimol Behavioral Testing

Animals with infusion cannulae underwent behavioral training until reaching the ‘low-effort” session criterion. The following day, 250nL PBS was infused at a rate of 75nL/minute bilaterally via the cannulae into the ACC 1 hour prior to their low-effort behavioral session. Animals then underwent at least 2 additional behavioral sessions without infusion. Next, 250nL of 0.5 mg/mL muscimol (ThermoFisher M23400) was infused at a rate of 75nL/minute bilaterally into the ACC 1 hour prior to their low-effort behavioral session. Animals then underwent at least 2 additional behavioral sessions without infusion. Finally, the muscimol infusion above was repeated prior to an “equal effort” session, in which both reward arms were paired with a “low-effort” barrier. Following this, the animals underwent additional non-infusion behavioral sessions. Animals were excluded due to any issues related to infusion (ie: clogged cannula; 2 mice excluded from muscimol experiments).

Fiber Photometry Recordings

Animals with fiber optic implants were attached via patch cord to the photometry system (see below) prior to training sessions throughout the course of behavioral training. Recordings were acquired for the entirety of each session and were time-locked to the behavioral system to permit analysis of ACC-NAc circuit activity in relation to effort-based decision-making behavior.

Optogenetic Behavioral Testing

Animals with bilateral fiber optic implants were attached via a dual core patch cord (Doric Lenses) throughout all training sessions in order to be comfortable performing the task while tethered. Following criterion performance on “high-effort” sessions, animals underwent a session with post-effort blue light stimulation. The patch cords were connected to a blue laser (473nm, OptoEngine) and laser power was adjusted prior to the session to be 8–10mW out of each side of the bilateral fiber cannula. During this session, an IR sensor located at the top of the high-effort barrier detected when animals had topped out on the barrier which then triggered the laser stimulation. Laser stimulation consisted of constant illumination until the animals acquired the high-reward at which point the light was turned off. This post-effort stimulation session was followed by at least 2 sessions without any stimulation. Finally, animals underwent a pre-effort stimulation session, in which the laser light was triggered at the start of the trial until the animals either reached the top of the barrier or turned and entered the low-reward arm at which point the light was turned off.

Chronic Corticosterone Behavioral Experiment

Animals underwent behavioral training until reaching criterion performance on “high-effort” sessions at which point they began chronic corticosterone treatment. Animals were given free access to their drinking water containing corticosterone (Sigma) dissolved at a concentration of 0.1mg/mL with 1% ethanol (Sigma) or a vehicle solution without corticosterone. After 21 days, water bottles were removed from the cages and water restriction was reinstated for 7 days prior to behavioral testing. During these 7 days, animals were given 1mL of regular drinking water per day. Following this period, “high-effort” behavioral sessions were performed. In the case of post-stress photometry, animals were recorded during these behavioral sessions.

Corticosterone ELISA

A high-sensitivity ELISA (Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Assay; Immunodiagnostic Systems Inc AC15F1) was used to measure serum levels of corticosterone in animals treated with 0.1mg/mL CORT or vehicle in the drinking water over 21 days. Animals were sacrificed by guillotine after treatment and trunk blood was collected into 1.5mL tubes, incubated at room temperature for 60 minutes then spun at 3000 × g for 15 minutes. The supernatant, containing serum, was removed to a separate tube and frozen at −80°C until the assay was performed, following a standard protocol. Samples were tested in triplicate and concentrations were determined as determined by the manufacturer.

Fiber Photometry: Data Acquisition

Fiber photometry recordings were performed using custom constructed optical equipment alongside custom LabView (National Instruments) software. Light from a 470nm LED (Thorlabs, M470F3) was modulated at 521Hz, filtered (Semrock, FF02–472/30) and combined via dichroic (Thorlabs, DMLP425R) to light from a 405nm LED (Thorlabs, M405F1) modulated at 211Hz and also filtered (FB405–10). These beams then passed through an additional dichroic (Semrock, FF495-Di03) and were coupled to a 0.48NA, 400um core patch cord (Doric) connected to the animal. Emitted fluorescence returned through the dichroic and was filtered (Semrock, FF01–535/50) before being focused onto a photodetector (Newport, Model 2151) connected to processing hardware. Optical modulation and lock-in amplification was accomplished via a Field Programmable Gate Array board (National Instruments, sbRIO-9637). TTL pulses from the behavioral system were passed to the recording hardware to permit alignment of photometry with behavioral events.

Fiber Photometry: Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using MATLAB (Mathworks). Raw fluorescence signals were normalized using the isosbestic control channel by least-squares fitting and subtracting the control signal from the raw signal and dividing by the control signal. Animals with poor signal-to-noise across multiple behavioral sessions (determined by the magnitude of signal fluctuation, <1.5% difference between the 95th and 5th percentile) were removed from analysis (one animal). Signals were z-scored within individual sessions to permit across animal and across session comparisons of relative activity changes during behavior. When determining signal changes related to specific behavioral events (ie: reward acquisition), a baseline signal prior to the behavior was determined as the average signal value from −1.5 to −1.0 seconds before the behavior and traces were shifted to set the baseline period at 0. To quantify activity levels related to behavioral events, the average signal for a window +/− 1.0 seconds around the behavior was taken. When quantifying the signal difference between low and high-reward trials during a session, the mean signal for each reward acquisition (window +/− 1.0 seconds) within a session was taken, the average of these signal levels for low-reward trials was then subtracted from the average for the high-reward trials to give an overall signal difference for that session.

Behavioral Video Tracking

In order to identify some behavioral events during trials (decision approach, reward approach and effort expended) it was necessary to utilize video tracking analysis to determine animal location during traversal of the maze. Tracking was done using Ethovision XT 11.5 (Noldus) to identify when the animals entered specific zones along the maze. The raw data was exported to MATLAB for analysis alongside photometry data.

Fixation, Sectioning, and Histology

Tissue fixation and sectioning was conducted to confirm targeting of viral expression and recording. Mice were anesthetized with an injection of euthasol (150mg/kg, i.p.) and brains were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde via aortic arch perfusion. They were then cryoprotected in 30% sucrose in PBS. Coronal sections were cut using a cryostat and mounted onto slides with DAPI for imaging via an epifluorescent microscope.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Statistical analyses were conducted in Prism 8.0 (Graphpad) and MATLAB (Mathworks). Behavioral analyses primarily utilized Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank tests, one-way ANOVAs and two-way ANOVAs with repeated measures as appropriate. Post-hoc testing was performed using either Dunn’s, Bonferonni or Tukey multiple comparisons testing as appropriate. Fiber photometry analyses primarily utilized linear mixed effects modeling in which mouse identity was modeled as a random effect to account for repeated measures from each mouse. Post-hoc testing of linear mixed effects models was performed using coeftest in MATLAB. R2 values for linear mixed effects models are reported for models with and without the random effect of subject to better identify the true predictive value of the fixed effects alone. All reported p values are two-tailed. Average photometry traces are represented as the mean +/− 95% confidence interval and bar plots represent the mean +/ s.e.m. Sample sizes were determined based upon previously published literature in the field.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Video 1. ACC-NAc activity during effort-based decision-making task (Related to Fig. 3).

Example of real-time photometry signal alongside behavioral video recording of a representative animal performing a low-effort session.

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| AAVrg-hSyn-Cre-WPRE-hGh | Addgene (Wilson Lab unpublished) | Addgene viral prep 105553-AAVrg |

| AAV1-Syn-FLEX-GCaMP6s-WPRE | Penn Vector Core | N/A |

| AAV1-hSyn-SIO-stGtACR2-FusionRed | Mahn et al. 73 | Addgene viral prep 105677-AAV1 |

| AAV1-hSyn-DIO-mCherry | Addgene (Roth lab DREADDs unpublished) | Addgene viral prep 50459-AAV1 |

| Biological samples | ||

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Muscimol | Thermofisher | Catalog number: M23400 |

| Corticosterone | Sigma-Aldrich | SKU: C2505-500MG |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| Corticosterone HS EIA | Immunodiagnostic Systems Inc | Product: AC-15F1 |

| Deposited data | ||

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| C57Bl/6J | Jackson Labs | Strain # 000664 RRID:IMSR_JAX:000664 |

| SST-IRES-Cre | Jackson Labs | Strain # 013044 RRID:IMSR_JAX:013044 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| Software and algorithms | ||

| Adobe Illustrator 2021 | Adobe | RRID:SCR_010279 |

| Prism 8.0 | GraphPad | RRID:SCR_002798 |

| MATLAB 2019b | Mathworks | RRID:SCR_001622 |

| LabView | National Instruments | RRID:SCR_014325 |

| Ethovision XT 11.5 | Noldus | RRID:SCR_000441 |

| Other | ||

Highlights.

ACC plays a critical role in supporting effort-based decision-making in mice

ACC-NAc activity integrates both reward- and effort-related information

Effort-sensitive reward activity in ACC-NAc supports future effortful choice

Chronic stress disrupts ACC-NAc activity and induces motivational anhedonia

Acknowledgements.

This work was supported by grants to C.L from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the One Mind Institute, The Hartwell Foundation, the Rita Allen Foundation, the Klingenstein-Simons Foundation Fund, the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation (formerly NARSAD), the Hope for Depression Research Foundation, and the Pritzker Neuropsychiatric Disorders Research Consortium. R.N.F was supported by a Medical Scientist Training Program grant from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award number T32GM007739 to the Weill Cornell/Rockefeller/Sloan Kettering Tri-Institutional MD- PhD Program as well as by an NRSA from the NIMH under award number F30MH115622. P.K.P was supported by a JumpStart Research Career Development Award from Weill Cornell Medicine and a K99/R00 Pathway to Independence award from NIMH (MH127291).

Inclusion and Diversity.

We support inclusive, diverse, and equitable conduct of research.

Footnotes

Competing Interests Statement. C.L is listed as an inventor for Cornell University patent applications on neuroimaging biomarkers for depression that are pending or in preparation. C.L serves on the Scientific Advisory Board of Delix Therapeutics and Brainify.AI and has formerly served as a consultant to Compass, P.L.C. The authors declare no other competing interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hart EE, and Izquierdo A (2019). Quantity versus quality: Convergent findings in effort-based choice tasks. Behav. Processes 164, 178–185. 10.1016/j.beproc.2019.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Treadway MT, and Zald DH (2011). Reconsidering anhedonia in depression: Lessons from translational neuroscience. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 35, 537–555. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Treadway MT, Bossaller N, Shelton RC, and Zald DH (2013). Effort-Based Decision-Making in Major Depressive Disorder: A Translational Model of Motivational Anhedonia. 121, 553–558. 10.1037/a0028813.Effort-Based. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooper JA, Arulpragasam AR, and Treadway MT (2018). Anhedonia in depression: biological mechanisms and computational models. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 22, 128–135. 10.1016/j.cobeha.2018.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang X. hua, Huang J, Zhu C. ying, Wang Y. fei, Cheung EFC, Chan RCK, and Xie G. rong (2014). Motivational deficits in effort-based decision making in individuals with subsyndromal depression, first-episode and remitted depression patients. Psychiatry Res. 220, 874–882. 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.08.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dichter GS, Smoski MJ, Kampov-Polevoy AB, Gallop R, and Garbutt JC (2010). Unipolar depression does not moderate responses to the sweet taste test. Depress. Anxiety 27, 859–863. 10.1002/da.20690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Der-avakian A, and Markou A (2012). The neurobiology of anhedonia and other reward-related deficits. Trends Neurosci. 35, 68–77. 10.1016/j.tins.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Husain M, and Roiser JP (2018). Neuroscience of apathy and anhedonia: A transdiagnostic approach. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 19, 470–484. 10.1038/s41583-018-0029-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salamone JD, Koychev I, Correa M, and McGuire P (2015). Neurobiological basis of motivational deficits in psychopathology. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 25, 1225–1238. 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2014.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salamone JD, Yohn SE, López-Cruz L, San Miguel N, and Correa M (2016). Activational and effort-related aspects of motivation: Neural mechanisms and implications for psychopathology. Brain 139, 1325–1347. 10.1093/brain/aww050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Culbreth Adam J., Moran Erin K., D.M.B. (2016). Effort-Based Decision-Making in Schizophrenia. Physiol. Behav. 176, 139–148. 10.1016/j.cobeha.2017.12.003.Effort-Based. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arnts H, van Erp WS, Lavrijsen JCM, van Gaal S, Groenewegen HJ, and van den Munckhof P (2020). On the pathophysiology and treatment of akinetic mutism. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 112, 270–278. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Le Heron C, Plant O, Manohar S, Ang YS, Jackson M, Lennox G, Hu MT, and Husain M (2018). Distinct effects of apathy and dopamine on effort-based decision-making in Parkinson’s disease. Brain 141, 1455–1469. 10.1093/brain/awy110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tye KM, Mirzabekov JJ, Warden MR, Ferenczi E. a., Tsai H-C, Finkelstein J, Kim S-Y, Adhikari A, Thompson KR, Andalman AS, et al. (2012). Dopamine neurons modulate neural encoding and expression of depression-related behaviour. Nature 493, 537–541. 10.1038/nature11740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lim BK, Huang KW, Grueter B. a., Rothwell PE, and Malenka RC (2012). Anhedonia requires MC4R-mediated synaptic adaptations in nucleus accumbens. Nature 487, 183–189. 10.1038/nature11160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Russo SJ, and Nestler EJ (2013). The brain reward circuitry in mood disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 14, 609–625. 10.1038/nrn3381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Treadway MT, Buckholtz JW, Schwartzman AN, Lambert WE, and Zald DH (2009). Worth the “EEfRT”? The effort expenditure for rewards task as an objective measure of motivation and anhedonia. PLoS One 4, 1–9. 10.1371/journal.pone.0006598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wacker J, Dillon DG, and Pizzagalli DA (2009). The role of the nucleus accumbens and rostral anterior cingulate cortex in anhedonia: Integration of resting EEG, fMRI, and volumetric techniques. Neuroimage 46, 327–337. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.01.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berridge KC, and Kringelbach ML (2015). Pleasure Systems in the Brain. Neuron 86, 646–664. 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.André N, Audiffren M, and Baumeister RF (2019). An Integrative Model of Effortful Control. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 13, 1–22. 10.3389/fnsys.2019.00079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bailey MR, Simpson EH, and Balsam PD (2016). Neural substrates underlying effort, time, and risk-based decision making in motivated behavior. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 133, 233–256. 10.1016/j.nlm.2016.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rushworth MFS, and Behrens TEJ (2008). Choice, uncertainty and value in prefrontal and cingulate cortex. Nat. Neurosci. 11, 389–397. 10.1038/nn2066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Devinsky O, Morrell MJ, and Vogt BA (1995). Contributions of anterior cingulate cortex to behaviour. Brain 118, 279–306. 10.1093/brain/118.1.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rudebeck PH, Walton ME, Smyth AN, Bannerman DM, and Rushworth MFS (2006). Separate neural pathways process different decision costs. Nat. Neurosci. 9, 1161–1168. 10.1038/nn1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hayden BY, Nair AC, McCoy AN, and Platt ML (2008). Posterior Cingulate Cortex Mediates Outcome-Contingent Allocation of Behavior. Neuron 60, 19–25. 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klein-Flügge MC, Kennerley SW, Friston K, and Bestmann S (2016). Neural signatures of value comparison in human cingulate cortex during decisions requiring an effort-reward trade-off. J. Neurosci. 36, 10002–10015. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0292-16.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Drysdale AT, Grosenick L, Downar J, Dunlop K, Mansouri F, Meng Y, Fetcho RN, Zebley B, Oathes DJ, Etkin A, et al. (2016). Resting-state connectivity biomarkers define neurophysiological subtypes of depression. Nat. Med. 10.1038/nm.4246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grieve SM, Korgaonkar MS, Koslow SH, Gordon E, and Williams LM (2013). Widespread reductions in gray matter volume in depression. NeuroImage Clin. 3, 332–339. 10.1016/j.nicl.2013.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pizzagalli DA (2014). Depression, stress, and anhedonia: toward a synthesis and integrated model. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 10, 393–423. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pizzagalli D, Pascual-Marqui RD, Nitschke JB, Oakes TR, Larson CL, Abercrombie HC, Schaefer SM, Koger JV, Benca RM, and Davidson RJ (2001). Anterior cingulate activity as a predictor of degree of treatment response in major depression: Evidence from brain electrical tomography analysis. Am. J. Psychiatry 158, 405–415. 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.3.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zilverstand A, Huang AS, Alia-Klein N, and Goldstein RZ (2018). Neuroimaging Impaired Response Inhibition and Salience Attribution in Human Drug Addiction: A Systematic Review. Neuron 98, 886–903. 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.03.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Paus T (2001). Primate anterior cingulate cortex: Where motor control, drive and cognition interface. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2, 417–424. 10.1038/35077500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jahanshahi M, and Frith CD (1998). Willed action and its impairments. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 15, 483–533. 10.1080/026432998381005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cummings JL (1993). Frontal-Subcortical Circuits and Human Behavior. Arch. Neurol. 50, 873–880. 10.1001/archneur.1993.00540080076020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Walton ME, Bannerman DM, and Rushworth MFS (2002). The role of rat medial frontal cortex in effort-based decision making. J. Neurosci. 22, 10996–11003. 22/24/10996 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]