Abstract

Background

Evidence suggests that PTSD symptoms following public health emergencies are influenced by many factors. The aim of this study was to investigate the relationship between perceived social support and Post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms and to explore the chain-mediated role of resilience and positive coping style, among medical staff in Hubei Province, China, during a public health emergency.

Methods

Convenience sampling was used to select medical staff from two general hospitals in Hubei Province in July 2022 for this study. A total of 2,751 medical staff were included in the study. Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support, 10- itemConnor- Davidson resilience scale, Simplified Coping Style Questionnaire and The Post-traumatic stress disorder Checklist for DSM-5 were used to assess the levels of perceived social support, resilience, coping style and Post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms of medical staff two years after the public health emergency. Statistical descriptions were conducted using SPSS, and a structural equation model was established using AMOS to analyze the chain-mediated roles of resilience and positive coping style between perceived social support and Post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms.

Results

Structural equation modeling results showed a standardized total effect of perceived social support on Post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms of -0.416 (95%CI [-0.456, -0.374], P < 0.001). Resilience mediated the effect of perceived social support and Post-traumatic stress disorder, with an indirect effect of -0.016 ( 95%CI [0.031, 0.001], P = 0.038). Positive coping mediated the effect of perceived social support and Post-traumatic stress disorder, with an indirect effect of -0.024 (95%CI [-0.035, -0.014], P < 0.001). Resilience and positive coping style chain-mediated between perceived social support and Post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms, mediating 17.1% of the total effect.

Conclusion

Perceived social support has significant direct and indirect effects on Post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms and resilience. In addition, positive coping style act as chain mediators between perceived social support and Post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms. We suggest that strengthening perceived social support for medical staff can enhance their resilience, encouraging them to adopt positive coping, which in turn reduces the level of post-traumatic stress symptoms among medical staff following public health emergencies.

Keywords: Public health emergency, Post-traumatic stress disorder, Perceived social support, Resilience, Positive coping style

Introduction

In December 2019, a public health emergency broke out in Wuhan and gradually swept the world [1]. Studies have shown that severe mental health crises often accompany public health emergencies and can have long-term adverse effects on the population [1, 2]. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a delayed, prolonged group of symptoms that occur after an individual experiences a life-threatening event and is categorized into four symptom clusters: intrusion, avoidance, cognition, and mood alteration and arousal [3]. Previous studies have found that medical staff at emergency response centers for public health emergencies are at a higher risk of developing PTSD symptoms than the general public [4, 5]. Studies have also found that most people experience varying degrees of PTSD symptoms after trauma, especially medical staff. PTSD symptoms in medical staff not only reduce the ability of medical staffto work, increase the level of burnout, and affect the quality of medical care but also may have a long-term, negative impact on health and quality of life, among other aspects of medical staffs’ health and quality of life [6, 7]. There is a wealth of existing research on the current status of PTSD symptoms among medical staff in the context of public health emergencies. However, most studies have started from a single aspect and focused only on the superficial connection between related factors and PTSD symptoms in medical staff. For example, although one study explored the detection rate of PTSD among medical staff and its influencing factors, it only focused on the relationship between general demographic elements, sleep status, and PTSD, while neglecting other key factors such as cognitive evaluation and social support [8]. These studies lack systematic theoretical guidance, and the influencing factors have not been systematically studied, which gives limited value to the subsequent effective psychological intervention strategies that can be provided.

Richard S. Lazarus, an eminent American psychologist, proposed the theory of stress and coping in the 1960s [9]. The theory suggests that the ability to produce stress after a stressor has affected an individual depends on two important psychological processes, including cognitive appraisal and coping. When stressors appear, individuals will first evaluate their external resources and internal capabilities, and then adopt different coping styles according to the evaluation results, which will ultimately affect the occurrence of adverse results. In this study, public health emergencies are stressors. Social support and psychological resilience represent an individual’s external resources and internal capacities, respectively, and PTSD is a possible negative outcome. These elements interact and together determine an individual’s adaptive process and outcome in the face of stress.

Perceived social support is recognized as an important environmental resource for reducing threat perceptions and coping with adverse situations [10]. In recent years, there has been considerable research confirming that social support predicts PTSD. Kshtriya et al. [11]. found that lower perceived social support significantly increased PTSD symptoms among disaster paramedics. A Japanese study showed that poorer perceived social support among paramedics was associated with the severity of PTSD symptoms during public health emergencies [12]. In addition, the level of perceived social support is closely related to, and interacts with, resilience and positive coping style [13, 14]. Resilience is the ability of an individual to recover quickly and adapt positively to adversity after experiencing significant trauma or stress [15]. Existing research suggests that resilience has a positive moderating effect on stress and the mental health of medical staff. Schierberl et al. [16]. conducted a survey in the United States and showed that nurses with higher resilience were better able to adapt to the public health emergency healthcare environment and had a lower risk of developing PTSD symptoms. Another study also showed that the higher the resilience of medical staff, the lower their PTSD symptom scores and the less severe their symptoms [17]. Coping style reflects an individual’s cognitive and behavioral style, and positive coping is considered a positive factor in combating negative emotions such as depression [18, 19]. Positive coping has been found to be a protective factor for PTSD symptoms in medical staff during the public health emergency pandemic. Enhancing the level of resilience in medical staff after trauma and promoting individuals to adopt positive coping strategies may be an effective intervention target for future prevention and intervention strategies [13, 20].

In the context of public health emergencies, several studies have now explored the mediating factors between social support and PTSD. For example, a survey of campus-quarantined nursing students in China confirmed that social support not only directly affects PTSD, but also indirectly affects PTSD through resilience [21]. This finding is consistent with Kumpfer’s transactional model of resilience [22]. In addition, Ting Zhou et al. [23]. showed that positive coping styles mediated social support and PTSD. Social support can reduce PTSD symptoms in frontline medical stafffighting COVID-19 by increasing the use of problem-focused coping strategies. In this way, both resilience and positive coping may be mediating factors.

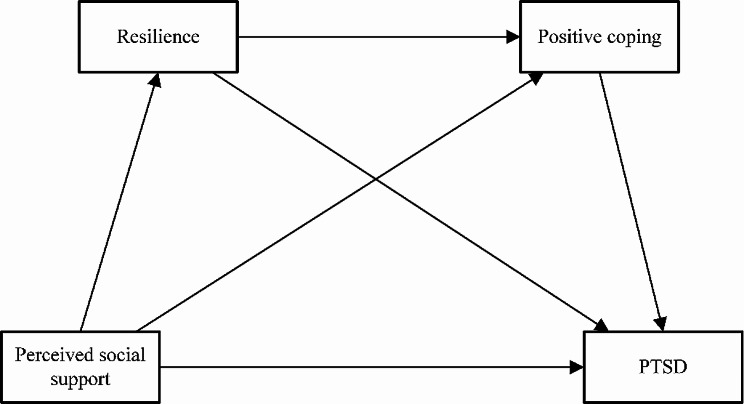

However, no relevant studies were found on the chain-mediating role of psychological resilience and positive coping levels in perceived social support and PTSD symptoms. Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate the relationship between PTSD symptoms, positive coping styles, perceived social support, and resilience. The specific objectives of the study are as follows: H1: Perceived social support is predictive of PTSD symptoms; H2: Resilience mediates the relationship between perceived social support and PTSD symptoms; H3: Positive coping style mediates the relationship between perceived social support and PTSD symptoms; and H4: Resilience is mediated through positive coping style between chain between perceived social support and PTSD symptoms. The theoretical model is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Research theoretical model. Notes: PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder

Methods

Design and participants

This is a cross-sectional study. Convenience sampling method was used to select medical stafffrom two general hospitals in Hubei Province in July 2022 as participants. The inclusion criteria were (1) those who were aged ≥ 18 years, (2) those who obtained a physician’s or nurse’s license, and (3) those who voluntarily participated in this study. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) those with existing psychological problems and (2) those who were uncooperative. It takes about 10–15 min to complete a questionnaire. All questionnaires were completed and stored in an online survey platform (“SurveyStar,” Changsha Ranxing Technology, Shanghai, China).

The data collection process in study consisted of two stages. In the first stage, two general hospitals in Wuhan, China, were selected through a simple random sampling principle. In the second stage, researchers sent online questionnaires through the medical office and nursing department to medical staff at the two selected hospitals and explained the purpose of this study. To prevent duplicate questionnaires, each Internet IP address could fill out the questionnaire only once. Simultaneously, invalid questionnaires were identified by setting up intelligent logic checks in the questionnaire software. Two researchers independently checked all valid questionnaire answers, which were then automatically entered into the data file using the software. In addition, each participant completed the questionnaire only once, and hospital administrators distributed the questionnaires. A total of 2,874 medical staff members were included, and 2,751 valid questionnaires were collected, with a validity rate of 95.7%. Of these 2,751 medical staff, 2,198 nurses participated in the survey, of whom 784 were from Tongji Hospital and 1,414 from Taihe Hospital.

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tongji Medical College of Huazhong University of Science and Technology (No. [2021] IEC (A006). The principles of voluntariness, confidentiality, and non-harmfulness were strictly adhered to throughout the study; the purpose, content, and precautions of the survey were explained to the subjects before the survey was conducted; their consent was obtained before the study was carried out; the subjects were allowed to withdraw from the survey at any time during the survey process; each questionnaire was coded and anonymously entered; and all data and information were not divulged to the outside world in any way, except for the purpose of scientific research.

Measurements

General information

This study was conducted through a literature review, reviewing and referring to relevant literature, and developing a general information questionnaire that included sex, age, marital status, education, type of occupation, department, years of experience, average monthly income of the individual, and whether occupational exposure occurred in the last year.

Multidimensional scale of perceived social support (MSPSS)

This scale was developed by Qianjin Jiang [24] based on the translation and revision of the Perceived Social Support Scale for Appreciation developed by Zimet et al [25]. It is used to assess the individual’s self-understanding and self-perceived perceived social support and has 12 items, including three dimensions: perceived social support from family, friends, and significant others (other than family and friends). The scale was scored on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = “strongly disagree” and 7 = “strongly agree”). The total score of the scale was the sum of the scores of all entries (12–84 points), which was positively correlated with the overall level of perceived social support. The higher the score, the higher the level of perceived social support of the medical staff. The reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the MSPSS have been validated in the Chinese population with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.89 [26]. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha of the MSPSS was 0.982. A confirmatory factor analysis was conducted on this questionnaire, and the fitness-for-purpose scores were acceptable: CFI = 0.924, IFI = 0.924, NFI = 0.923.

10- Itemconnor- davidson resilience scale (CD- RISC- 10)

The scale was simplified from CD-RISC of 25 items by Campbell-shills et al. [27]. The Chinese version was revised by Zhang Danmei et al. [8]. There are 10 entries in the scale. The scale is based on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = “never” and 4 = “always”), and the total score of the scale is the sum of all the scores of the entries. The total score ranges from 0 to 100 points, and the higher the score is, the higher the resilience of the medical staff is. In the Chinese population, the Cronbach’s alpha of the CD-RISC-10 was 0.91 [28]. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha of the CD- RISC- 10 scale was 0.974. A confirmatory factor analysis was carried out on this questionnaire. The results were acceptable: CFI = 0.921, IFI = 0.921, NFI = 0.92.

Simplified coping style questionnaire (SCQS)

The scale was compiled by Xie et al [29]. and includes 20 entries with two dimensions: the 1st–12th entries were considered as the positive coping style and the 13th–20th entries were considered as the negative coming style. The scale adopts a 4-point Likert scale (0 points for not taking, 3 points for often taking), and respondents were scored according to the frequency of coping style taken, with positive coping style scores ranging from 0 to 36 points and negative coping style scores ranging from 0 to 24 points. This study selected only entries related to positive coping style. In the Chinese population, the Cronbach’s alpha of the positive coping style was 0.89 [29]. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha of the scale measured was 0.976. Confirmatory factor analysis was performed on this questionnaire and the fit was acceptable: CFI = 0.907, IFI = 0.907, NFI = 0.906.

PTSD checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5)

The scale was developed by Blevins et al [30]. based on the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for PTSD and uses a self-report method to measure an individual’s level of PTSD symptoms following a traumatic event. The scale has 20 items and includes four dimensions: intrusion, avoidance, cognition, and mood alteration and arousal. The scale is rated on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = “not at all” and 4 = “extremely”). A total scale score of ≥ 33 was considered positive for screening PTSD symptoms, with higher scores indicating more severe PTSD symptoms. The reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the PCL-5 have been validated in the Chinese population with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.91 [31]. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha of the PCL-5 was 0.982. Confirmatory factor analysis was carried out on this questionnaire. The results were acceptable: CFI = 1, IFI = 1, NFI = 1.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS 26.0 (PSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and AMOS 23.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA), and P < 0.05 (two-tailed) was considered statistically significant. Based on the normality criterion proposed by Curran et al. (1996) (i.e., skewness ≤ 2; kurtosis ≤ 7), all variables were first checked to see if they conformed to a normal distribution, and all the variables in this study conformed to the normality assumption. Frequency (n) as well as composition ratio (%) were used to describe the general demographic data, and Mean ± Standard deviation (Mean ± SD) was used to descriptively analyze the scores of perceived social support, resilience, coping style, and PTSD symptoms, respectively; Pearson’s correlation analysis was used to correlate the medical staff’ perceived social support, resilience, coping style, and PTSD symptoms; and AMOS 23.0 software for chained mediation analysis using the maximum likelihood method. The nonparametric percentile Bootstrap method confirmed the significant effect sizes for each pathway (the 95% confidence intervals for direct and indirect effects did not contain 0). Model fit was evaluated with χ2 /df < 5, goodness-of-fit index (GFI), Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), incremental fit index (IFI), and comparative fit index (CFI) greater than 0.90, and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) less than 0.08 (Hu and Bentler, 1999).

Results

Descriptive and correlation analysis

The survey finally included 2,751 medical staff, of which the proportion of women was significantly higher than that of men, accounting for 83.2%; the age range of medical staff participating in the survey was 20–59 years old; 74% of the medical staff were married (2,036), and the number of unmarried people accounted for 24.3% of the total number of people; in terms of occupation, 2,198 nurses/midwives (79.9%) and 533 doctors (79.9%); in terms of years of working experience, the largest number of medical staff were those with more than 10 years of working experience (1,233, 44.8%), and only 260 medical staff with less than or equal to two years of working experience, which accounted for 9.5% of the total number of workers; moreover, 13.2% of the medical staff had experienced occupational exposures during their work on the current public health emergencies. In terms of sleep quality, only 23.7% of medical staff had good sleep quality; 13.5% of medical staff had experienced a major traumatic event in the last year other than that associated with a new coronary pneumonia infection; 5.3% of the participants suffered from chronic diseases; 79.4% had to work night shifts;52.8% of the participants worked more than eight hours a day. The results of single factor analysis showed that the distribution of PTSD symptoms among different age, education level, type of occupation, department, years of working, occupational exposure, sleep quality, experiencing other traumatic events, and daily working hours were statistically different (P < 0.05). The highest PTSD score of 23.33 ± 18.896 was found in medical staffwith very poor sleep quality. (Table 1)

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the participants

| Variables | n(%) | PTSD | t/F | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | -0.533 | 0.594 | ||

| Male | 461(16.8) | 9.42 ± 13.362 | ||

| Female | 2290(83.2) | 9.77 ± 12.648 | ||

| Age (years old) | 18.046 | <0.001 | ||

| 20–30 | 933(33.9) | 8.42 ± 12.051 | ||

| 31–40 | 1416(51.5) | 10.16 ± 12.987 | ||

| >40 | 402(14.6) | 11.09 ± 13.378 | ||

| Marital status | 0.499 | 0.607 | ||

| Single | 668(24.3) | 9.78 ± 12.901 | ||

| Married | 2036(74) | 9.73 ± 12.764 | ||

| Other | 47(1.7) | 7.87 ± 12.769 | ||

| Education level | 2.039 | 0.130 | ||

| Below bachelor’s degree | 154(5.6) | 9.33 ± 12.681 | ||

| Bachelor | 2027(73.7) | 9.99 ± 12.704 | ||

| Master degree and above | 570(20.7) | 8.79 ± 12.995 | ||

| Type of occupation | 3.046 | 0.048 | ||

| Doctor | 533(19.4) | 8.56 ± 12.533 | ||

| Nurse /Midwife | 2198(79.9) | 10.01 ± 12.827 | ||

| Other | 20(0.7) | 7.55 ± 11.095 | ||

| Department | 3.714 | 0.025 | ||

| Emergency Department | 71(2.6) | 10.70 ± 11.626 | ||

| Department of Intensive Care Medicine | 187(6.8) | 12.06 ± 13.943 | ||

| Other | 2493(90.6) | 9.71 ± 12.769 | ||

| Years of working | 6.493 | <0.001 | ||

| ≤ 2 | 260(9.5) | 7.48 ± 12.139 | ||

| 3–5 | 404(14.7) | 8.18 ± 11.308 | ||

| 6–10 | 854(31) | 9.35 ± 12.6 | ||

| 11–15 | 707(25.7) | 11.06 ± 13.5 | ||

| >16 | 526(19.1) | 10.75 ± 13.121 | ||

| Average monthly income (Yuan) | 1.654 | 0.175 | ||

| <5000 | 181(6.6) | 7.98 ± 12.633 | ||

| 5000–9999 | 1317(47.9) | 9.64 ± 12.749 | ||

| 10,000–14,999 | 924(33.6) | 10.23 ± 12.889 | ||

| ≥ 15,000 | 329(12) | 9.48 ± 12.544 | ||

| Occupational exposure | -5.094 | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 364(13.2) | 13.56 ± 15.330 | ||

| No | 2387(86.8) | 9.12 ± 12.229 | ||

| Sleep quality | 159.090 | <0.001 | ||

| Good | 651(23.7) | 5.64 ± 10.317 | ||

| Fair | 1679(61) | 9.73 ± 12.460 | ||

| Bad | 360(13.1) | 14.68 ± 13.584 | ||

| Very bad | 61(2.2) | 23.33 ± 18.896 | ||

| Experiencing other traumatic events | -7.658 | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 371(13.5) | 14.99 ± 15.601 | ||

| No | 2380(86.5) | 8.88 ± 12.066 | ||

| Chronic disease | -0.004 | 0.997 | ||

| Yes | 147(5.3) | 10.64 ± 13.681 | ||

| No | 2604(94.7) | 9.66 ± 12.716 | ||

| Night shift | 1.808 | 0.071 | ||

| Yes | 2183(79.4) | 9.93 ± 12.908 | ||

| No | 568(20.6) | 8.85 ± 12.192 | ||

| Daily working hours | -3.295 | < 0.001 | ||

| >8 | 1453(52.8) | 10.63 ± 13.441 | ||

| ≤ 8 | 1298(47) | 8.68 ± 11.893 |

Pearson’s correlation was used to correlate perceived social support, resilience, coping style, and PTSD symptoms among the medical staff. The results of the correlation analysis showed that the two-by-two correlations among the variables were statistically significant (P < 0.01). Perceived social support, resilience, and coping style were significantly positively correlated (P < 0.01) and significantly negatively correlated with PTSD symptoms (P < 0.01). The conditions of the structural equation modeling (SEM) were met. The detailed results are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Means, standard deviations (SD) and Pearson correlations (N = 2,751)

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Perceived social support | 72.39 | 12.153 | 1 | - | - | - |

| 2. Resilience | 27.82 | 10.72 | 0.316** | 1 | - | - |

| 3. Positive coping | 26.39 | 8.99 | 0.384** | 0.741** | 1 | - |

| 4. PTSD symptoms | 9.71 | 12.769 | -0.416** | − 0.264** | -0.311** | 1 |

Notes: PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder

** p<0.01

Mediating effects models

Chain mediation analysis was performed using AMOS 23.0, using the maximum likelihood method. The nonparametric percentile Bootstrap method confirmed the significant effect sizes for each pathway (95% confidence intervals for direct and indirect effects did not include 0). Therefore, in the context of public health emergencies among medical staff, resilience and positive coping were significant chain mediators between perceived social support and PTSD symptoms (H4). The results of the SEM analyses are presented in Fig. 2; Table 3.

Fig. 2.

The chain-mediated model of resilience and positive coping between perceived social support and PTSD symptom. Notes: PTSD, posttrumatic stress disorder; **. P < 0.01; ***. P < 0.001

Table 3.

Bootstrapping direct and indirect effects and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the mediation model

| Effects | Paths | Standardized estimates |

Bootstrap |

|---|---|---|---|

| 95%CI | |||

| Direct | |||

| Perceived social support→PTSD | -0.345*** | -0.392 to -0.299 | |

| Indirect | |||

| Perceived social support→ Resilience→ PTSD | -0.016* | -0.031 to -0.001 | |

| Perceived social support→Positive coping→ PTSD | -0.024*** | -0.035 to -0.014 | |

| Perceived social support→ Resilience→Positive coping→ PTSD | -0.031*** | -0.043 to- 0.019 | |

| Total | |||

| Perceived social support→PTSD | -0.416*** | -0.456 to -0.374 |

The results showed that perceived social support was negatively associated with PTSD symptoms. The standardized direct predictive effect of perceived social support on PTSD symptoms was − 0.345(95%CI [-0.392, -0.299], P < 0.001) (H1). The indirect effect pathways were as follows: in the perceived social support – resilience – PTSD symptom pathway, the indirect effect was − 0.016(95%CI [-0.031,-0.001], P = 0.038) (H2); in the perceived social support – positive coping – PTSD symptom pathway, the indirect effect was − 0.024(95%CI [-0.035, -0.014], P < 0.001) (H3); and in the pathway of perceived social support – resilience – positive coping – PTSD symptoms, the indirect effect was − 0.031(95%CI [-0.043, -0.019], P < 0.001) (H4). Perceived social support can influence PTSD symptoms directly, through the mediating role of resilience, through the mediating role of positive coping, and sequentially through influencing resilience and positive coping. The model explained 20.1% of the variance in PTSD symptoms (R2 = 0.201). Resilience and positive coping played a partial mediating role, mediating 17.1% of the total effect.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to demonstrate that resilience and positive coping play a chain mediating role between perceived social support and PTSD. This study’s results showed a negative correlation between perceived social support and PTSD symptoms, supporting H1; that is, the higher the perceived social support, the less severe the PTSD symptoms. This is consistent with previous findings that higher perceived social support was a key protective factor for medical staff’s PTSD symptoms during the public health emergency pandemic, and higher levels of perceived social support may help medical staff reduce PTSD symptoms [32, 33]. In addition, a recent study showed that perceived social support from colleagues and organizations could buffer the development of mental health disorders among medical staff [34]. Therefore, in the context of public health emergencies, the perceived level of social support of medical staff can be increased in both the family and workplace to improve the mental health of medical staff.

Additionally, resilience partially mediated the relationship between perceived social support and PTSD symptoms, thus supporting H2. Previous findings have also shown that perceived social support can further influence psychological problems in female college athletes by affecting resilience [35], and medical staff with higher levels of resilience are better able to adapt to the work environment in the face of public health emergencies and are less likely to develop PTSD [36]. Therefore, hospitals and the state should consider strengthening the level of resilience during the training of medical staff to improve the development of PTSD symptoms in the face of public health emergencies.

A positive coping style partially mediated the relationship between perceived social support and PTSD symptoms, supporting H3. A survey in Singapore showed that medical staff who adopted a positive, proactive coping style in the context of a public health emergency also had a lower risk of PTSD symptoms [37]. Conversely, negative and avoidant coping style were associated with higher levels of PTSD symptoms [38]. This study also confirms that active coping is a key resilience factor for people to adapt well to traumatic events and that adopting an active coping style is beneficial for alleviating negative emotions among medical staff [39, 40].

PTSD was significantly and negatively correlated with perceived social support, resilience, and positive coping scores in this study, and resilience and positive coping style acted as chain mediators between perceived social support and PTSD symptoms, supporting H4. This aligns with the findings of a previous study on the psychological status of survivors after flooding storms [41], which showed that social support and resilience can limit avoidance responses in coping style and thus reduce PTSD symptoms. Coupled with the fact that social support has a significant effect on resilience [42], we can, therefore, activate resilience in people at risk of PTSD by providing more social support and appropriate psychotherapy to help them adopt a positive coping style. However, the sample size of this study was limited to medical staff, and the results need to be subsequently validated in other populations.

This study demonstrated the predictive role of perceived social support on PTSD symptoms and the chain mediation of resilience and positive coping style under the guidance of a stress system model among medical staff in Wuhan, China, two years after a public health emergency. The study has both theoretical and practical implications. In terms of theoretical implications, this study extends the literature on the direct and indirect associations between perceived occupational social support and PTSD symptoms among Chinese medical professionals. The chain mediating role of psychological resilience and positive coping between social support and PTSD was argued, providing additional theoretical foundations for subsequent research. In terms of practical implications, this study provides an important reference for the development of clinical interventions for PTSD symptoms among medical staff during major public health emergencies. To reduce the symptoms of PTSD in medical staff, the government and hospital administrators can provide more policy and material support to enhance the psychological resilience of medical staffand improve their coping styles. However, this study has certain limitations. First, which may not be representative of the whole of Hubei Province, we selected health workers from only two tertiary hospitals. Second, the participants in this study were medical staff from Hubei province. There was a lack of participants from other provinces. The results of the study are only representative of regions highly affected by the public health emergency pandemic. In future studies, we hope to include different types of hospitals and different provinces to encompass a broader range of medical staff. In addition, this study used the cross-sectional research method to conduct research and design. Subsequent studies could provide richer empirical evidence using longitudinal research.

Conclusions

This study confirms that the perceived social support of medical staff is negatively correlated with PTSD symptoms two years after a public health emergency. Not only can it directly affect the symptom level of PTSD, but also indirectly through the mediating role of resilience and positive coping style, respectively, as well as indirectly through the chain mediating effect of resilience and positive coping style on the symptoms of PTSD. In the follow-up intervention, PTSD symptoms can be addressed to improve the mental health level of medical staff by strengthening the perceived social support for medical staff, enhancing the resilience of medical staff, and strengthening the adoption of positive coping style by medical staff.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the medical staff who participated in this study and the authors who contributed to this study.

Abbreviations

- PTSD

Post-traumatic stress disorder

Author contributions

YL, LZ and WF designed research. JC, YL, LZ and WF completed Writing-review & editing. YL, ZX, JW, PZ, JZ, LZ and WF collected data. JC, ZC, JT, WF conducted data analysis. JC, YL, JW, LZ performed data visualization. JC and YL Write original draft. ZC conducted data curation. SY and YW completed review & editing.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant. 72104082) and the Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province (Grant. 2022CFB721) and the Program of Excellent Doctoral (Postdoctoral) of Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University (Grant. ZNYB2021003) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant. 2042022kf1151).

Data availability

Date will be made available on request, if necessary, please contact the author Junjie Cao.(1057029143@qq.com).

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All methods in this study were conducted in accordance with the principles stated in the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China (number: 2021-IEC-A006). Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Consent for publication

The authors affirm that human research participants provided informed consent for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Junjie Cao, Yifang Liu and Shijiao Yan are co-first author and contributed equally to this work.

Wenning Fu, Li Zou and Ying Wang are contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Ying Wang, Email: 752460170@qq.com.

Li Zou, Email: zouli1231@whu.edu.cn.

Wenning Fu, Email: wenningfu@hust.edu.cn.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19–11 March 2020[EB/OL]. (2020-3-11) [2023-3-15]. https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-sopening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020

- 2.Oliveira JF, Jorge DCP, Veiga RV, et al. Mathematical modeling of COVID-19 in 14.8 million individuals in Bahia, Brazil. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):333. 10.1038/s41467-020-19798-3. Published 2021 Jan 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5 [M]. American Psychiatric Association Washington, DC; 2013.

- 4.Zhang WR, Wang K, Yin L, et al. Mental Health and Psychosocial Problems of Medical Health Workers during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Psychother Psychosom. 2020;89(4):242–50. 10.1159/000507639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liang Y, Wu K, Zhou Y, Huang X, Zhou Y, Liu Z. Mental Health in Frontline Medical Workers during the 2019 Novel Coronavirus Disease Epidemic in China: a comparison with the General Population. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(18):6550. 10.3390/ijerph17186550. Published 2020 Sep 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chamaa F, Bahmad HF, Darwish B, et al. PTSD in the COVID-19 era. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2021;19(12):2164–79. 10.2174/1570159X19666210113152954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al Falasi B, Al Mazrouei M, Al Ali M, et al. Prevalence and determinants of Immediate and Long-Term PTSD consequences of Coronavirus-Related (CoV-1 and CoV-2) pandemics among Healthcare professionals: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(4):2182. 10.3390/ijerph18042182. Published 2021 Feb 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang R, Hou T, Kong X et al. PTSD Among Healthcare Workers During the COVID-19 Outbreak: A Study Raises Concern for Non-medical Staff in Low-Risk Areas. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:696200. Published 2021 Jul 12. 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.696200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Kiyak S. The relationship of depression, anxiety, and stress with pregnancy symptoms and coping styles in pregnant women: a multi-group structural equation modeling analysis. Midwifery Published Online July. 2024;4. 10.1016/j.midw.2024.104103. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Mattos AIS, Araújo TM, Almeida MMG. Interaction between demand-control and social support in the occurrence of common mental disorders. Rev Saude Publica. 2017;51(0):48. 10.1590/S1518-8787.2017051006446. Published 2017 May 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kshtriya S, Kobezak HM, Popok P, Lawrence J, Lowe SR. Social support as a mediator of occupational stressors and mental health outcomes in first responders. J Community Psychol. 2020;48(7):2252–63. 10.1002/jcop.22403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tatsuno J, Unoki T, Sakuramoto H, Hamamoto M. Effects of social support on mental health for critical care nurses during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in Japan: a web-based cross-sectional study. Acute Med Surg. 2021;8(1):e645. 10.1002/ams2.645. Published 2021 Apr 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kilinc T, Celik AS. Relationship between the social support and psychological resilience levels perceived by nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic: a study from Turkey. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2021;57(3):1000–8. 10.1111/ppc.12648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mai YP, Wu YJ, Huang YN. What type of Social Support is important for Student Resilience during COVID-19? A latent Profile Analysis. Front Psychol. 2021;12. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.646145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Luthar SS, Cicchetti D, Becker B. The construct of resilience: a critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Dev. 2000;71(3):543–62. 10.1111/1467-8624.00164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schierberl Scherr AE, Ayotte BJ, Kellogg MB. Moderating roles of Resilience and Social Support on Psychiatric and Practice outcomes in nurses Working during the COVID-19 pandemic. SAGE Open Nurs. 2021;7:23779608211024213. 10.1177/23779608211024213. Published 2021 Jun 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prout TA, Zilcha-Mano S, Aafjes-van Doorn K, et al. Identifying predictors of psychological distress during COVID-19: a Machine Learning Approach. Front Psychol. 2020;11:586202. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.586202. Published 2020 Nov 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Segerstrom SC, Smith GT. Personality and coping: individual differences in responses to emotion. Annu Rev Psychol. 2019;70:651–71. 10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-102917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Folkman S, Moskowitz JT. Coping: pitfalls and promise. Annu Rev Psychol. 2004;55:745–74. 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Q, Liu W, Wang JY, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms among Chinese health care workers following the COVID-19 pandemic. Heliyon. 2023;9(4):e14415. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e14415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang D, Qin L, Huang A et al. Mediating effect of resilience and fear of COVID-19 on the relationship between social support and post-traumatic stress disorder among campus-quarantined nursing students: a cross-sectional study. BMC Nurs. 2023;22(1):164. Published 2023 May 16. 10.1186/s12912-023-01319-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Ren Chunhua C, Xiaofei P. Association of social support and psychological resilience with post-traumatic stress disorder in college students [J]. Chin J School Health. 2023;44(03):407–10. 10.16835/j.cnki.1000-9817.2023.03.020. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou T, Guan R, Sun L. Perceived organizational support and PTSD symptoms of frontline healthcare workers in the outbreak of COVID-19 in Wuhan: the mediating effects of self-efficacy and coping strategies. Appl Psychol Health Well Being. 2021;13(4):745–60. 10.1111/aphw.12267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiang GJ. Perceptive social support scale (PSSS). Manual of Mental Health Rating Scale [M]. Beijing: Chinese heart Journal of Health; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zimet GD, Powell SS, Farley GK, Werkman S, Berkoff KA. Psychometric characteristics of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. J Pers Assess. 1990;55(3–4):610–7. 10.1080/00223891.1990.9674095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chou KL. Assessing Chinese adolescents’ social support: the multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Personal Individ Differ. 2000;28(2):299–307. 10.1016/S0191-8869(99)00098-7. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Campbell-Sills L, Stein MB. Psychometric analysis and refinement of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC): validation of a 10-item measure of resilience. J Trauma Stress. 2007;20(6):1019–28. 10.1002/jts.20271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang L, Shi Z, Zhang Y, Zhang Z. Psychometric properties of the 10-item connor-davidson resilience scale in Chinese earthquake victims. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2010;64(5):499–504. 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2010.02130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yaning Xie. A preliminary study of the reliability and validity of the Brief Coping Style Scale [J]. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1998(02):53–54. 1998(02):53–54.10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.1998.02.018

- 30.Blevins CA, Weathers FW, Davis MT, Witte TK, Domino JL. The posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): development and initial psychometric evaluation. J Trauma Stress. 2015;28(6):489–98. 10.1002/jts.22059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang L, Zhang L, Armour C, et al. Assessing the underlying dimensionality of DSM-5 PTSD symptoms in Chinese adolescents surviving the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake. J Anxiety Disord. 2015;31:90–7. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2015.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu Y, Zou L, Yan S, et al. Burnout and post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms among medical staff two years after the COVID-19 pandemic in Wuhan, China: social support and resilience as mediators. J Affect Disord. 2023;321:126–33. 10.1016/j.jad.2022.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu Y, Fu W, Zou L, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and depression of Chinese medical staff after 2 years of COVID-19: a multicenter study. Brain Behav. 2022;12(11):e2785. 10.1002/brb3.2785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Riedel B, Horen SR, Reynolds A, Hamidian Jahromi A. Mental Health Disorders in Nurses During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Implications and Coping Strategies. Front Public Health. 2021;9:707358. Published 2021 Oct 26. 10.3389/fpubh.2021.707358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Mikesell M, Petrie TA, Chu TLA, Moore EWG. The Relationship of Resilience, Self-Compassion, and Social Support to Psychological Distress in Women Collegiate Athletes During COVID-19. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2023;45(4):224–233. 10.1123/jsep.2022-0262. PMID: 37474120. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Brown TA, Campbell LA, Lehman CL, Grisham JR, Mancill RB. Current and lifetime comorbidity of the DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders in a large clinical sample. J Abnorm Psychol. 2001;110(4):585–99. 10.1037/0021-843x.110.4.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Phua DH, Tang HK, Tham KY. Coping responses of emergency physicians and nurses to the 2003 severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12(4):322–8. 10.1197/j.aem.2004.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sim K, Chong PN, Chan YH, Soon WS. Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related psychiatric and posttraumatic morbidities and coping responses in medical staff within a primary health care setting in Singapore. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(8):1120–7. 10.4088/jcp.v65n0815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hui FX, Li, Xianghong Fan. Investigation on post-traumatic stress disorder of nursing staff during the novel coronavirus pneumonia epidemic [J]. J Nurs. 2020;35(24):84–6. 10.3870/j.issn.1001-4152.2020.24.084. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kang L, Ma S, Chen M, et al. Impact on mental health and perceptions of psychological care among medical and nursing staff in Wuhan during the 2019 novel coronavirus disease outbreak: a cross-sectional study. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:11–7. 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bistricky SL, Long LJ, Lai BS, Gallagher MW, Kanenberg H, Elkins SR, Short MB. Surviving the storm: avoidant coping, helping behavior, resilience and affective symptoms around a major hurricane-flood. J Affect Disord. 2019;257:297–306. 10.1016/j.jad.2019.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhong MS, She F, Wang WJ, Ding LS, Wang AF. The Mediating effects of Resilience on Perceived Social Support and Fear of Cancer recurrence in Glioma patients. Psychol Res Behav Manage. 2022;15:2027–33. 10.2147/prbm.S374408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Date will be made available on request, if necessary, please contact the author Junjie Cao.(1057029143@qq.com).