Abstract

Per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), a contentious group of highly fluorinated, persistent, and potentially toxic chemicals, have been associated with human health risks. Currently, treatment processes that destroy PFAS are challenged by transforming these contaminants into additional toxic substances that may have unknown impacts on human health and the environment. Electrochemical oxidation (EO) is a promising method for scissoring long-chain PFAS, especially in the presence of natural organic matter (NOM), which interferes with most other treatment approaches used to degrade PFAS. The EO method can break the long-chain PFAS compound into short-chain analogs. The underlying mechanisms that govern the degradation of PFAS by electrochemical processes are presented in this review. The state-of-the-art anode and cathode materials used in electrochemical cells for PFAS degradation are overviewed. Furthermore, the reactor design to achieve high PFAS destruction is discussed. The challenge of treating PFAS in water containing NOM is elucidated, followed by EO implementation to minimize the influence of NOM on PFAS degradation. Finally, perspectives related to maximizing the readiness of EO technology and optimizing process parameters for the degradation of PFAS are briefly discussed.

Keywords: Water treatment, Electrochemical oxidation, Natural organic matter, Per-fluoroalkyl substances, Boron-doped diamond electrode

1. Introduction

The ever-increasing volumes of wastewater generated by industries and the stringent regulatory policies governing its disposal have accelerated the need to develop innovative technologies to treat them efficiently and economically. Per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances (collectively, PFAS) are anthropogenic compounds extensively employed in various industrial and commercial applications and pose potential environmental and health risks [1–3]. The six most studied PFAS compounds are perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS); perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA); perfluorodecanoic acid (PFDA); perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA); perfluorohexane sulfonic acid (PFHxS); and perfluoroheptanoic acid (PFHpA). These ’forever chemicals’ usually do not degrade naturally; they steadily cycle through and accumulate in the environment. Certain PFAS are also bioaccumulative [4], and several PFAS have been found at detectable levels in human blood [5]. PFAS toxicity is currently being studied, and there is sufficient evidence to inspire efforts to control environmental release and human exposure [6–8]. Also, the varying quantity and quality of organic matter (OM) significantly influence the selection, design, and operation of water treatment processes.

There are numerous barriers when attempting to treat PFAS-laden wastewater, particularly in the presence of other pollutants. Natural organic matter (NOM) is ubiquitous in the different compartments of the aquatic environment [1]. The unique structure of PFAS combines a hydrophilic ionic head (−COOH, −SO3H) with a fluorinated carbon tail, giving them biphasic or surfactant properties [1,9]. NOM may engage in electrostatic or hydrophobic interactions with PFAS [1]. Organic matter, primarily composed of anionic species, can produce repulsive electrostatic interactions when it adheres to materials (e.g., adsorbents) [10]. Reduced long-chain retention caused by a more hydrophilic NOM emphasizes the significance of electrostatic and hydrophobic forces as well as the range that can be achieved depending on the overall net charge and PFAS hydrophobicity/hydrophilicity [11]. Through a hydrophobic interaction between the perfluoroalkyl tail and NOM adsorbed on the adsorbent surface, NOM may also promote the adsorption of PFAS [12]. It is currently unclear how these effects interact and which is dominant. When PFAS are released into the environment, the chemical characteristics that make them useful from an industrial standpoint also make them mobile and recalcitrant [13].

Conventional wastewater treatment methods (i.e., activated sludge) have proved ineffective in the biodegradation of PFAS [1,14–18]. It is attributed to the powerful and stable C-F bond (bond dissociation energy > 500 kJ/mol) [19,20] and the high electronegativity of fluorine in those compounds [21]. PFAS require specialized enzymes for their degradation. The microorganisms in activated sludge treatment systems are typically not equipped with the specific enzymes necessary to break down these compounds. Also, PFAS can inhibit the growth and activity of microorganisms responsible for biodegradation in conventional treatment processes. However, under harsh treatment conditions—high temperature and high pressure—PFAS can be efficiently degraded [22,23]. Most technologies utilize robust oxidizing species such as hydroxyl radicals (•OH) E0 = 1.8–2.7 V vs. normal hydrogen electron (NHE), semiconductor holes, sulfate radical () E0 = ~2.4 V vs. NHE, and reductive species like hydrated electrons () E0 = ~ −2.9 V vs. NHE [24]. The •OH reacts fast with PFOA with rate constants (k) in the order of 108-1010 M−1s−1, while reacts slowly, k ≈ 104 M−1s−1 [25,26]. It is known that •OH radical generated from conventional advanced oxidation processes has a limited capacity to break down PFAS [27]. During the decomposition processes, toxic byproducts may be formed, and it is difficult to achieve complete mineralization and defluorination of PFAS. More importantly, the presence of organic matter reduces the overall efficiency of most processes. The underlying problem in the entire defluorination process (completely transforming all the C-F bonds into F− ions) is still debatable, particularly in the presence of organic matter. Therefore, there is still a need to develop an environmentally friendly and cost-effective method to effectively eliminate PFAS in the presence of organic matter to decrease their harmful impact.

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) health advisory levels of PFOA and PFOS in drinking water previously established at 70 parts per trillion (ppt) have been lowered to 0.004 ppt and 0.02 ppt, respectively [28,29]. It has led to a global quest for effective PFAS degradation technologies. Various technologies have been proposed to remove PFAS from the environment, but complete degradation remains elusive. Advanced electrochemical [30], photochemical [31], plasma [32], electron beam irradiation [33,34], and chemical oxidation [35] techniques are suggested for PFAS destruction. Ongoing research is understanding the effectiveness of these techniques in creating a breakthrough in PFAS degradation.

There are limitations in both oxidative and reductive PFAS degradation. For example, fluorine can be effectively removed by via H/F exchange, but the chemical stability of the resulting fluorotelomer carboxylic acids (FTCAs, CnF2n+1(CH2)m-COO-) increases dramatically with the further exchange of H/F [24]. On the other hand, while the oxidation process using h+, •OH, and can convert the PFAS of long-chain carboxylic acid into small chains [36,37], the strong shielding effect from the dense electron cloud surrounding the fluorine atoms significantly hinders defluorination. Herein, we present a comprehensive review of the electrochemical oxidation (EO) of PFAS in real water matrices. The content of this review is timely because it sheds light on the recent progress made in electrochemical strategies for PFAS degradation. The study delves into various aspects of the electrochemical approach, such as the degradation mechanism employed and the choice of electrode material, which are crucial factors in achieving efficient PFAS degradation. The main objective of this review is to draw attention to how NOM interferes with the EO process. By looking at these factors, we seek to understand better how to decompose PFAS utilizing the EO approach successfully. Finally, to significantly increase the destruction efficiency and result in complete PFAS degradation, we recommend the simultaneous participation or integrated oxidation and reduction process.

2. Advanced oxidation processes (AOPs)

Advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) have received increasing attention for wastewater treatment, particularly in the presence of NOM. NOM plays the dual role of enhancement and inhibition in AOPs [12]. AOPs use •OH to attack persistent organic pollutants and degrade them into smaller components or inorganic ions/molecules [38]. In some instances, NOM can enhance the removal of micropollutants during AOPs by complexing with PFAS via hydrophobic interactions [39,40]. Because of the larger diffusive flux of high-concentration NOM to the electrode in the presence of PFOS-NOM hydrophobic contacts, the transport of PFOS to the site of oxidation at the electrode surface may be enhanced [39]. In contrast, NOM can also exhibit inhibitory effects on AOPs and organic pollutant removal [40]. This inhibition is primarily attributed to the competition for the available radicals between NOM and PFAS [41,42]. Due to their high concentrations in natural waters and complex structure, NOM compounds can readily react with the generated radicals, leading to their consumption [42]. This competition for radicals reduces the available reactive species crucial for micropollutant degradation. Consequently, the presence of NOM can hinder the removal efficiency of AOPs by decreasing the contact time between radicals and target micropollutants.

The production of aggressive oxidant (•OH) radical requires a catalyst to react with ozone (O3), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), or UV light. In addition, -based AOPs have been proven to possess preferable oxidation ability due to the high electrophilic property (+2.437 ± 0.019 V vs. NHE, 25 °C) and longer lifetime [43]. For example, Wacławek et al. reported PFOA degradation with slow reaction kinetics ≈ 104 M−1 s−1 [44]. The process requirements (e.g., chemicals, UV, and catalysis) to generate radicals mean harsh conditions and low environmental compatibility. However, electrochemical processes may have advantages in this aspect, as radicals can be generated in situ via electrochemical reactions.

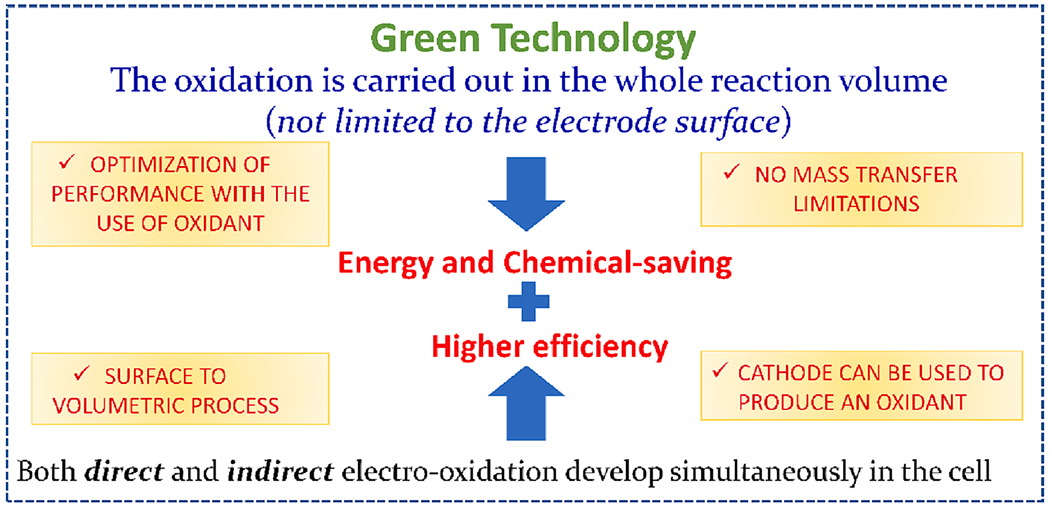

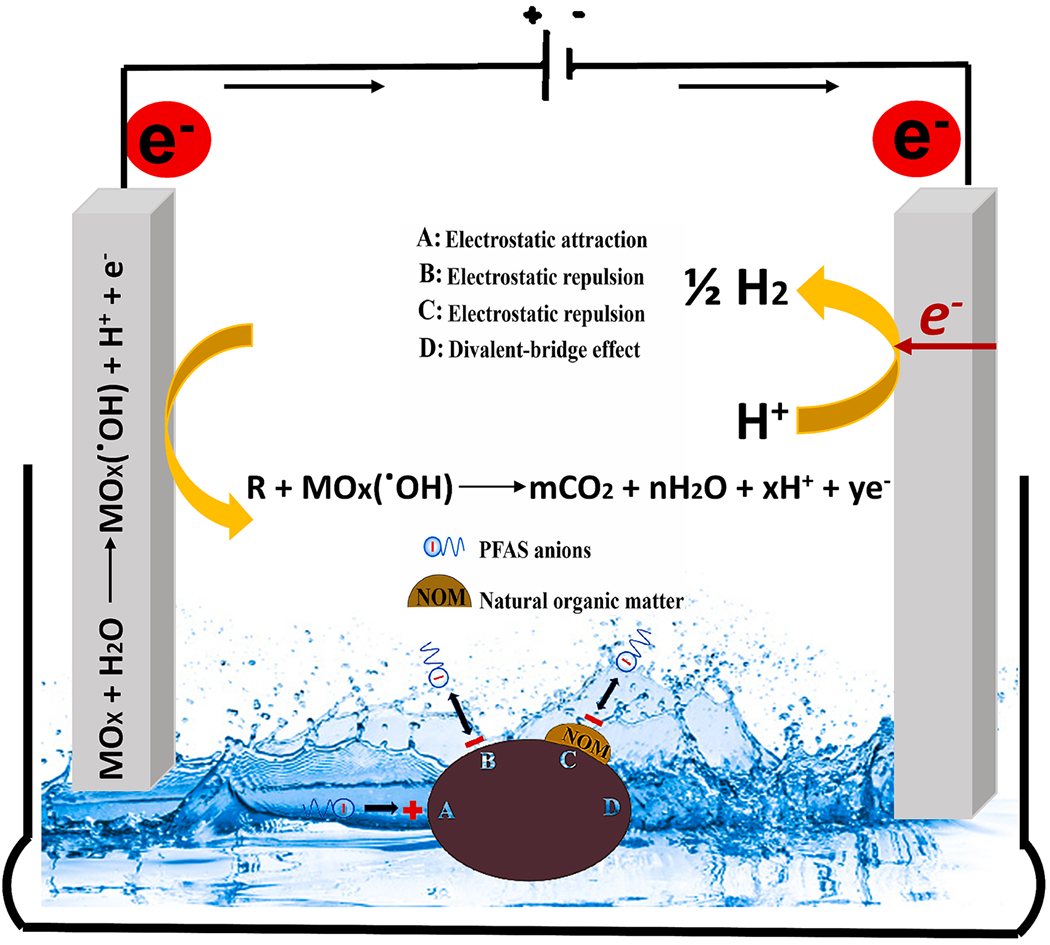

The primary benefit of electrochemical processes is the simultaneous occurrence of numerous electrochemical reactions at anodes and cathodes (Fig. 1). The oxidation/reduction process can be driven by electricity rather than by chemicals to produce radicals. The lower consumption of chemicals, low energy demand (e.g., an opportunity to be integrated with renewable energy sources, including solar or wind power and fuel cells), operation in ambient conditions, and ability to be in a mobile unit makes the process more adaptable, sustainable, and environmentally friendly. Additionally, the electrochemical process can directly oxidize the targeted contaminants or produce other radicals besides •OH (e.g., superoxide radicals () and hydroperoxyl radicals (•HO2)), which can potentially degrade the persistent contaminants that cannot be degraded by •HO alone due to the stable fluoro-carbon skeleton [45]. Electrochemical treatment has shown removal rates of>99% for long-chain PFAS [9]. The processes also have the advantage of oxidizing most organic matter and completely mineralizing them to generate carbon dioxide and water [46]. The in-situ generated •OH is adsorbed by the metal oxide electrode in the oxygen potential zone forming (MOx(•OH)) to oxidize the targeted pollutants.

Fig. 1.

Advantages of the electrochemical process for PFAS degradation.

Electrochemical processes have some limitations, including the possibility of hazardous byproducts (e.g., hydrogen fluoride (HF), perchlorate, and halogenated organics), [47,48] the partial elimination of certain PFAS, efficiency loss owing to mineral contamination build-up on the anode, high cost of electrodes, and possible volatilization of contaminants (mainly HF vapor, which is highly corrosive) [48]. Even though long-chain PFAS have shown to be highly effective at being removed, short-chain PFAS are typically harder for the EO method to degrade. Due to the conversion of precursors, the concentration of short-chain PFAS may even increase after treatment. Despite such challenges, EO can be a promising ’green’ technology for PFAS destruction as it is less energy intensive compared to thermal incineration (>1100 °C) with a possibility of converting hazardous byproducts to high value-added compounds (contributing to the circular economy) [49]. Additionally, compared to single-solute PFAS systems, this technique can effectively degrade multi-solute solutions containing a mixture of PFAS [50]. Other notable benefits include the dual function of PFAS degradation and organic matter removal.

In the following sections, we present the mechanisms that govern the electrochemical processes and the role of electrode materials and reactor design in the degradation of PFAS in water.

3. Electrochemical oxidation (EO) of PFAS

For EO, the applied electrical current densities are in the range of 20–350 A/m2 to optimize the kinetics rates of PFAS degradation [51]. Results showed better removal efficiency at 50 mA/cm2 compared to 10 and 20 mA/cm2, and the removal efficiencies of PFBA and perfluoroalkyl acids (PFAA) were > 95% and 99%, respectively, within 8 h of treating synthetic PFAS samples [52]. Several factors, including electrode properties and surface area, initial PFAS concentration, coexisting contaminants, efficiency target, and voltage, directly influenced the contact time needed to treat PFAS. The degradation of PFAS on the surface of the electrodes was closely related to electron transfer reactions [53]. PFAS can be decomposed via direct and indirect oxidation. In the direct oxidation pathway (also known as anodic oxidation), an electron is transferred from the PFAS compound to the anode. In contrast, the indirect route involves electrochemically created, powerful oxidants—hydroxyl radicals. The following chemical reactions (Eqs 1–4) briefly describe the PFAS degradation mechanism involved in anodes.

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

An electron is transported from the head group of PFAS to the anode under the influence of an electric field to create PFAS radicals (Eq (1), which are then decomposed into (Eq (2). The formed radical would combine with •OH to undergo the subsequent step-by-step removal of −CF2− [54,55]. PFAS are expected to degrade through C–C chain cleavage rather than the C-F bond, especially the CF2-COOH bond in PFOA and the CF2-SO3H bond in PFOS, given the bond strength/energy. In other words, defluorination is more challenging than degradation of the C–C chain via oxidation unless the catalysis is selective to the C-F bond.

The electrochemical degradation of PFOA involves two routes. The first route converts PFOA to perfluoroheptanoic acid (PFHpA having a lesser −CF2 – than PFOA) [56,57]. The steps involved are given in Eqs 5—7.

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

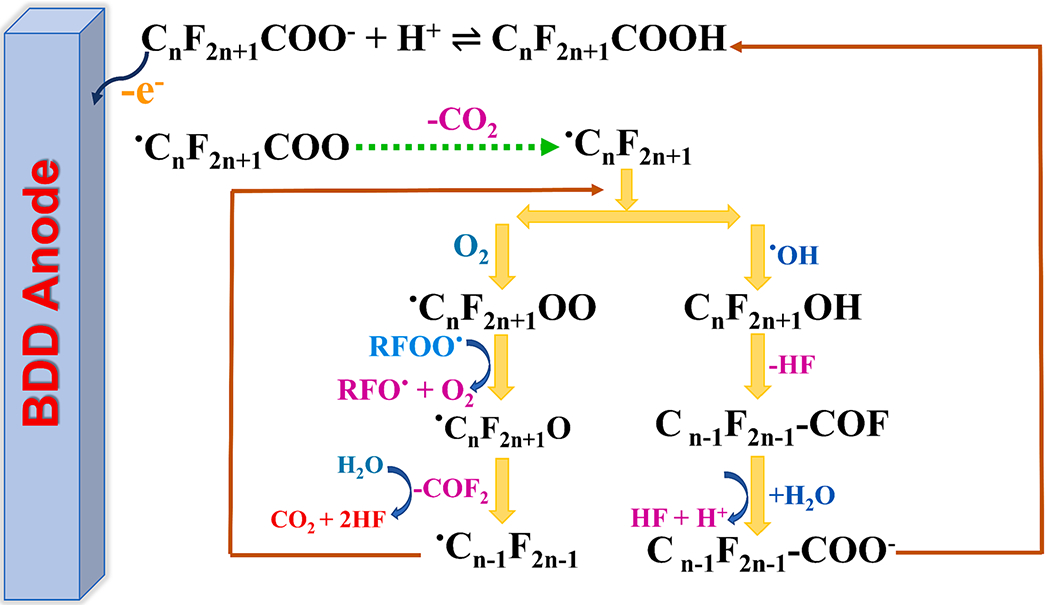

The degradation mechanism is initiated by abundant •OH, resulting in strong chemical reactivity in the electrolysis process [58]. Then, the elimination of HF from C7F15OH to produce acyl fluoride C6F13COF takes place. In the final step, C6F13COF reacts with H2O through hydrolysis to yield C6F13COOH [57]. However, another route may also be possible in which the radicals react with oxygen from water electrolysis to create the C7F15OO• radicals (Eq (8). Subsequently, the C7F15OO• radical would combine with another RCOO• radical (Eq (9), forming a C7F15O• radical [57]. The C7F15O• radical has two potential reaction routes: (i) C7F15OH• formation as a result of a reaction with and (ii) further decomposition to form perfluoroalkyl radicals () and carbonyl fluoride (COF2). In the final step, the produced COF2 decomposes entirely to CO2 and HF (Eqs 10–12).

| (8) |

| (9) |

| (10) |

| (11) |

| (12) |

The complete mineralization of PFOA to CO2, HF, and H+ involves 14 electrons, where the initial step must undergo a series of subsequent steps (Eq (13) [49]. A schematic of the mechanisms that govern PFAS degradation is provided in Fig. 2. The formed HF and the change in pH can affect EO.

Fig. 2.

The proposed degradation mechanism of PFOA.

| (13) |

The electrochemical decomposition mechanisms of PFOS also follow two pathways. One decomposition pathway involves transferring an electron from its head group to the anode material to be converted into [57]. The subsequent electrolysis of by H2O produces C8F17OH, which quickly undergoes hydrolysis to form C7F15COO− [59]. Next, C7F15COO− undergoes a stepwise decarboxylation cycle, eliminating the CF2 units until complete mineralization occurs (Eqs 14–16).

| (14) |

| (15) |

| (16) |

The first step is similar to the previously described mechanism. With a considerable amount of oxygen produced by water hydrolysis, the formed can undergo a reaction that transforms it into C8F17OO• (Eq17), which would then combine with RFOO• to create C8F17O• (Eq (18) [56]. Due to the instability, C8F17O• then breaks down into and COF2 (Eq19). The formed COF2 later reacts with water to produce CO2 and HF. The reprocessing cycle allows for the breakdown of PFOS into CO2 and F−.

| (17) |

| (18) |

| (19) |

4. Electrode materials and reactor design

4.1. Anode material

Electrodes for electrochemical oxidation/reduction play a significant role in PFAS degradation. Anode material determines whether the system can operate stably and efficiently. For anodes with high oxidation power, a high current efficiency for organic oxidation and a low electrochemical activity for oxygen evolution are typically observed [60]. This is due to the weak interactions between these anodes’ electrodes and hydroxyl radicals [60]. The direct electron transfer at the anode typically restricts the rate of PFAS oxidation electrochemically (i.e., the rate-limiting step for PFAS oxidation on an electrode). The resulting perfluoroalkyl radical can then react with •OH, O2, or H2O to degrade the one-carbon shorter perfluoroheptanecarboxylate by severing the head group (−COOH vs. −SO3H) (i.e., perfluoro alkyl carbonate). The newly formed carboxylate, one carbon shorter, then undergoes the same decomposition as the original PFOA, which converts the carboxylic acid head to carbon dioxide, the fluorine atoms to hydrogen fluoride, and the CF2 to another carboxylic acid group in that order. The electrode materials mentioned in the literature include platinum (Pt), carbon or graphite (C), iridium dioxide (IrO2), ruthenium dioxide (RUO2), tin dioxide (SnO2), boron-doped diamond (BDD), lead dioxide (PbCO2), Ti4O7 (Ebonex), as well as TiO2 nanotube array. These electrode materials can boost the productivity of radicals and inhibit the emission of O2. However, BDD is a more promising anode material to carry out EO for the degradation of PFAS.

BDD anodes offer a ’chemical-free’ treatment for PFAS-contaminated water by effectively initiating the electron removal from PFOA and PFOS-like ionic heads. The reason for choosing BDD electrodes as anode material compared to other anodes is the greater overpotential required to oxidize water to oxygen [60,61]. For anodes such as platinum, gold, or glassy carbon, the oxygen overpotential falls within the 1.7 to 2.2 V range [61]. This enables the boron-doped material to act as an anode with better efficacy. The surface of the BDD electrode can produce enough concentration of quasi-free state hydroxyl radical (•OH), and its high redox potential can oxidize almost all refractory pollutants to CO2, H2O, and inorganic ions without selectivity (Eq (20).

| (20) |

Other advantages of BDDs include the ability to generate •OH at a low electrical current, stability at high current densities [62], chemical inertness, long life span, mechanical durability, and less fouling tendency compared to other anodes. In a bench-scale laboratory experiment, BDD was used as the electrode material, and it was found that under ideal circumstances, the degradation efficiency of PFAS was over 90% [63]. This study also showed that current density and treatment time are crucial to achieving the optimum degradation results. Due to cost issues (approximately $7125/m2) [64,65], the BDD anode is often substituted with other anode materials like mixed metal oxide (MMO)—SnO2, MnO2, and PbO2 [66]. MMOs are considered good alternatives but aren’t commercialized due to their short life span and metal leaching issues [67]. The potential surface damage to the MMO electrode caused by fluorination is also a problem. However, F− doping may sometimes prove beneficial in the degradation process. For instance, it was found that PbO2 doped with F− inhibited O2 emission and expedited oxidation, improving the degradation efficiency [68]. The reason is that incorporating F− into the bulk structure reduces the extent of adsorbed water at α-PbO2 or β-PbO2 [69]. Similarly, SnO2 doped with F− has been shown to be promising for highly effective PFOA wastewater treatment [70]. The Magneli-phase (Ti4O7) has recently gained popularity as advantageous electrode material due to its superior electrical activity, conductivity (1000 S/cm), chemical stability, and cost-effectiveness [71,72].

Various other strategies are also developed to produce better anode material for the efficient destruction of PFAS. An effective Ti4O7 electrode loaded with amorphous Pd clusters has been developed [72], outperforming Ti4O7 electrodes loaded with crystalline Pd particles, which have been widely considered as a benchmark to enable the electrode’s catalytic function. This can be explained by the enhanced electron transfer through predominate Pd-O bonds in an amorphous Pd-loaded catalyst. These amorphous Pd clusters were distinguished by their noncrystalline, disordered arrangement of Pd single atoms in close proximity. They also showed that the anodic PFOA oxidation process does not involve any radical formation, which is particularly advantageous for electrocatalytic systems in the water treatment process [72]. This may minimize the quenching of radical species by background species like NOM and subsequent decrease in contaminant removal. Few other techniques (e.g., defect engineering (by doping)) have the potential to improve the catalytic activity and stability significantly by modifying the surface properties and electronic structures [73]. In a different study, the PFOS oxidation rate increased 2.4 times when 3 at. % of Ce3+ dopant was added to the Ti4O7 electrode [73]. The introduction of a minor amount (0.1–2.0% wt%) of carbon materials to the Ti4O7 electrode surface create a heterojunction structure which could significantly enhance the interfacial electron-transfer process because the presence of −C-O(H) on the carbon material surface decreases the electron-transfer resistance [74]. The presence of 0.1 wt% of carbon content resulted in a 13-fold increase of the oxalic oxidation kinetics compared to those of the pure Ti4O7 electrode. Reactive sites of heterogeneous catalysts usually lie on the surface and subsurface, which allow the improvement of the catalytic property via engineering the surface atoms [75]. Sb-doped SnO2 electrodes can also be an appealing electrode material for the anodic oxidation of organic pollutants like PFOA because they have good conductivity and a high overpotential for oxygen evolution of about 1.9 V vs. SHE (i.e., 600 mV higher than Pt). An additional approach is creating 3D porous anodic material, such as BDD, that can be an alternative to the conventional 2D-BDD anode. The reason for choosing 3D anodic materials is their high electrochemical active surface area (ECSA) and higher mass transfer coefficient (PFOA towards PP-BDD is 2.6 × 10−5 m s−1, which is about 6.1 times higher than that of 2D-BDD with 0.42 × 10−5 m s−1), thus achieving PFOA degradation even at high applied current, compared to the 2D anode material [76]. Ti powders with > 99.9% purity were chosen as the original material for 3D printing fabrication and used as the electrode substrate for PFOA removal [76]. The different anode materials used in the electrochemical oxidation of PFAS are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

A summarized table of different anode materials used in the electrochemical oxidation of PFAS.

| Anode | PFAS Type | Experimental Parameters | Initial Concentration | Time (mins) | Removal Efficiency | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zr-PbO2 | PFOA | current density = 10 mAcm−2 Temperature = 25 °C constant current density: 10 mA cm− 2 Initial pH value: 4.8 10 mmol L− 1 NaClO4 supporting electrolyte |

100 ppm | 90 | 97% | [77] |

| Ce-PbO2 | PFOA | current density = 20 mAcm−2 Temperature = 25 °C 10 mmol L− 1 NaClO4 supporting electrolyte |

100 ppm | 90 | 96.7% | [67] |

| Ti4O7 | PFOA | current density = 5 mAcm−2 Temperature = 25 °C, 20 mM NaClO4 supporting electrolyte. |

50 ppm | 180 | 93.1% | [78] |

| Ti/SnO2–Sb/PbO2 | PFOA | current density = 10 mAcm−2 Temperature = 25 °C 10 mmol/L NaClO4 supporting electrolyte. |

100 ppm | 90 | 91.1% | [79] |

| Ti4O7 anode | PFOS | current density = 5 mAcm−2 Temperature = 25 °C 20 mmol/L NaClO4 supporting electrolyte. |

50 ppm | 180 | 93.1% | [78] |

| Ti4O7 REM | PFOS | Temperature = 25 °C pH value: 7.0 100 mM K2HPO4 |

5 ppm | NA | >99.9% | [71] |

| (Ti1-xCex)4O7 (x = 3%) | PFOS | current density = 20 mAcm−2 Temperature = 25 °C current density of 1 A/cm2 the solution pH value was not adjusted |

10 ppm | 240 | >99% | [73] |

| Ti/SnO2-Sb-Bi | PFOA | 1.4 g/L NaClO4 electrolyte constant current = 0.25 A Temperature = 32 °C |

50 ppm | 120 | 99% | [56] |

| F doped Ti/SnO2 | PFOA | current density = 20 mAcm−2 10 mM NaClO4 electrolyte |

100 ppm | 30 | >99.9% | [70] |

| BDD | PFOA | 1.4 g/L NaClO4 electrolyte Temperature = 32 °C pH = 3.0 current density = 23.24 mAcm−2 |

47 ppm | 120 | 97.48 | [61] |

| 2D BDD | PFOA | current density = 20 mAcm−2 Temperature = 24 °C 0.05 M Na2SO4 electrolyte |

200 ppm | 180 | 67 | [76] |

| 3D BDD | PFOA | current density = 20 mAcm−2 Temperature = 24 °C 0.05 M Na2SO4 electrolyte |

200 ppm | 150 | 100 | [76] |

4.2. Cathode material

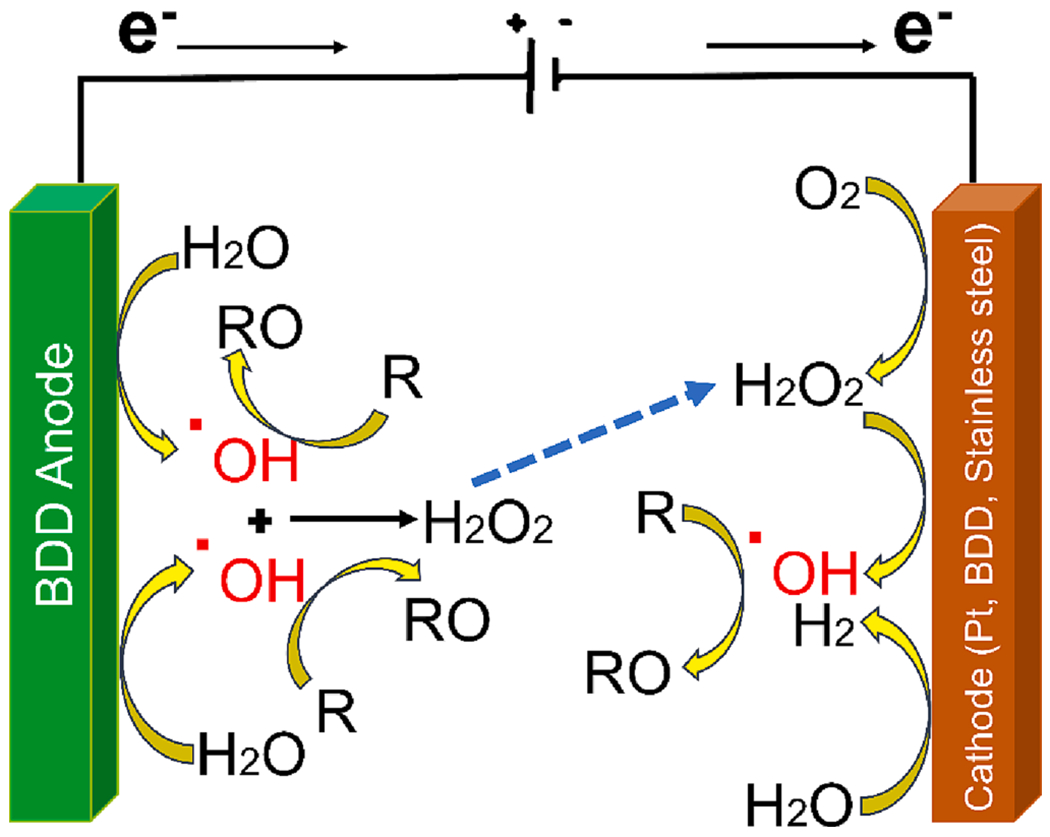

In the electrochemical processes to degrade PFAS, consideration should also be given to the cathode and the reactions occurring at the electrode to recover energy by producing and utilizing the electrical currents. As a required component of an electrochemical cell, the cathodic reaction should be designed to maximize the activity and reduce the energy requirement in PFOA electro-oxidation. The four major roles of cathodic material involve i) H2 evolution, ii) direct reduction of pollutants and intermediates, (iii) metal electrodeposition, and (iv) indirect production of oxidizing agents [80]. O2 and H2O2 are produced during the EO treatment of organic pollutants using a BDD anode [81]. Therefore, it is reasonable to anticipate that these species will undergo cathodic reduction and may even produce •OH, which may aid in global decontamination. The contribution of cathodic hydroxyl radical generation to the enhancement of the electrooxidation process for water treatment is shown in Fig. 3. The defluorination trends are the following: Pt > BDD > Zr > Steel [82]. The hydrogen produced at the surface of the Pt electrode is responsible for the PFOA hydrodefluorination.

Fig. 3.

Cathodic hydroxyl radical production during electro-oxidation (EO) enhances water decontamination (Adapted with permission from Medel et al. [80]Elsevier).

As discussed earlier, the direct electron transfer happens at the anode surface, where the PFOA is inert to the hydroxyl radicals. The alcohol is produced after the reaction of •OH with the adsorbed hydrogen produced by the water electro-reduction at the cathode, releasing 2F− [36]. After the defluorination process from the cathode, the •OH can possibly reattack, forming C6F13COOH. It is important to note that the specific reaction steps depend on the cathode material. The feasibility of electrochemical reductive decomposition of PFOA using an Rh/Ni cathode has been reported [83], in which the cathode material was modified by coating Rh3+ on Ni foil via an electrodeposition process. Hydrodefluorination occurs using DMF as the solvent (medium with a wide electrochemical window where the target pollutant can migrate to the cathode) at a cathodic potential of −1.25 V, and the Rh coating assisted in the adsorption of PFOA through Rh⋯F interactions and facilitated C-F bond activation. The C-F bond eventually dissociated and transformed into the C−H bond via H* substitution due to the continuous interaction of cathode-supplied electrons [83].

4.3. Reactor design

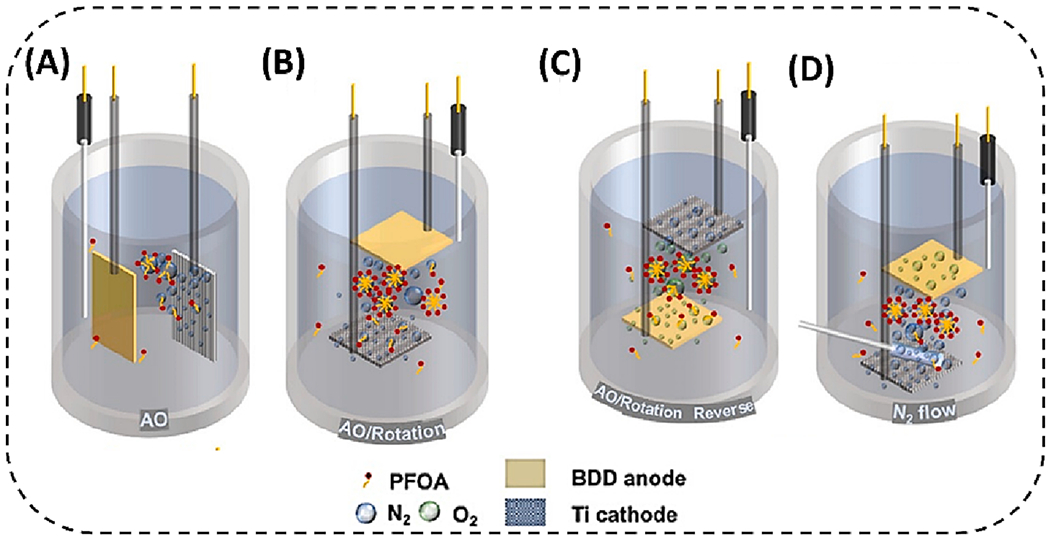

The energy consumption for the PFAS degradation process is a significant issue, and the reactor design is an important parameter that can enhance the overall performance. The optimal cell can reduce energy loss and increase efficacy. In the electrochemical destruction of PFAS, the anodic part is given more attention for EO, whereas the energy utilized in the cathodic part is often overlooked. The bubbles in the electrochemical cell have a significant role in enhancing the activity by concentrating the PFAS. It has been shown that the air bubbles produced on the surface of hydrophobic carbonaceous adsorbents have a substantial role in PFOS adsorption. Using cathodic-produced bubbles during the electrochemical reaction can improve PFAS degradation efficiency [84]. By simply changing the orientation of the cathode by 90°, and when the anode is placed at the top (AO/rotation), as shown in Fig. 4, the PFOA gets concentrated by the cathodic-generated hydrogen bubble and moves towards the anode for further oxidation. In this approach, the PFOA concentration near the anode can be increased more than three times, achieving 50% more PFOA removal at 4.5 V vs. standard hydrogen electrode (SHE) in AO/Rotation system. In another work, the extent of PFOS removal by the pristine carbon nanotubes and graphite decreased by 79% and 74%, respectively, after vacuum degassing for 36 h, indicating that air bubbles are primarily responsible for PFOS adsorption [85]. This reveals that designing a better electrochemical reactor could achieve enhanced removal of PFAS degradation with less energy consumption, making this technology economically viable in practical application.

Fig. 4.

Schematic diagram of (a) AO system, (b) AO/Rotation system, the experimental setup for (c) eliminating bubble interference from cathodic hydrogen evolution reaction, and (d) exploring the influence of bubble flow rate. (Adapted with permission from Wan et al. [84] American Chemical Society).

The mass transfer of PFAS from the bulk solution to the anode surface, which only occurs at or near the anode surface, limits EOP degradation [86]. Reactive electrochemical membrane (REM) operation, which improves interphase mass transfer by filtering polluted samples using porous material that serves as both a membrane and anode, was proposed as a solution to the mass transfer constraint [87]. Therefore, even a single water flow through the membrane may help to improve the overall effectiveness of electrochemical oxidation for removing PFAS. Tthe REM system has been examined to degrade PFOS by utilizing a ceramic membrane with a Magneli phase titanium suboxide [88]. The REM reactor was operated at a 40.0 mL/min flow rate with the target pollutant PFOS (2.0 M) and electrolyte Na2SO4 (100.0 mM). With different current densities, the change in linear PFOS concentration was investigated. Since there was no application of electric current during the first 40 min, there was no difference in the concentration of PFOS in the permeate, which was the same as in the retentate, indicating only modest adsorption of PFOS onto the membrane electrode. Immediately after applying electric current, the concentration of PFOS in the permeate decreased. During 120 min of current supply, the PFOS concentration remained low, but the elimination increased to 98% when the current density climbed to 4.0 mAcm−2. After 120 min, the current flow was cut off, and the concentration of PFOS in the permeate recovered to being similar to that of the retentate. These findings demonstrate that electrochemical degradation is the only mechanism by which PFOS was removed from the permeate stream. A batch reactor-based direct electrochemical oxidation method using a titanium suboxide tubular anode was used to compare the performance of the REM system. PFOS consistently degraded in the batch electrochemical oxidation system, except when the current density was below 0.5 mAcm−2. Similar to the REM system, as the applied current density grew, so did the rate of PFOS degradation in the batch system.

An energy-efficient Magneli phase Ti4O7 REM has also been utlized to oxidize PFOA and PFOS [71]. In one run through the REM, these chemicals were removed around 5-log, with residence durations of 11 s at 3.3 V/SHE for PFOA and 3.6 V/SHE for PFOS. From starting concentrations of 4.14 and 5 mg/L, the permeate concentrations of PFOA and PFOS were 86 and 35 ng/L, respectively. At a permeate flux of 720 L m−2h−1 (residence durations of 3.8 s), the maximum removal rates for PFOS and PFOA were 2436 and 3415 mol m−2h−1, respectively. Energy requirements (per log removal) were 5.1 and 6.7 kWh m−3, respectively, to remove PFOA and PFOS to levels below detection limits. Interestingly these values are the lowest reported for electrochemical oxidation and roughly an order of magnitude lower than those reported for other technologies (such as ultrasonication, photocatalysis, vacuum ultraviolet photolysis, and microwave-hydrothermal decomposition), showing that electrochemical oxidation is not as efficient as other processes.

The following section will discuss the impact of the co-existence of PFAS and NOM in contaminated groundwater and wastewater on EO performance. We aim to highlight that most lab-tested technologies have been tested with synthetic solutions and tend to perform inefficiently in the natural environment due to the interference of NOMs.

5. Electrochemical treatment in the presence of natural organic matter

One of the primary sources of water supply is surface water, which contains NOM- a mixture of organic matter from biological and terrestrial sources [89]. Humic acid, polysaccharides, proteins, and lipids comprise most of its structure. Additionally, it may be aggregated with contaminants such as antibiotics or pesticides. Since lipids and aliphatic proteins include organic materials or monomers with carboxyl groups, these substances are oxidized by electrochemically produced free radicals to acids with lower molecular weight and are then mineralized to produce CO2 and H2O. NOM has the advantage of acting as an electron donor or acceptor with various other redox-active species, mediating reactions between species with varying redox potentials. Due to the extensive coupling of redox-active moieties in NOM via intramolecular conduction, the sample potential sometimes reflects a continuum of electrode response, similar to the NOM redox properties [90]. Also, due to poor contact between the redox-active moieties in NOM and the working electrode surface, conventional electrochemical voltammograms typically produce poor results (with more broad and average features). Advanced techniques like the sequential use of cyclic and square-wave voltammetry (SCV and SWV) can be valuable in interpreting peaks and other features regarding NOM redox processes.

NOM significantly impacts the effectiveness of electrochemical oxidation during wastewater treatment. Therefore, it is crucial to investigate molecules’ specific interactions and oxidation reactions in the electrochemical process and which parts of NOM may preferentially react with free radicals in the electrolyte solution [89]. It is feasible to oxidize the specific saturated functional groups of NOM electrochemically. Electro-oxidation of NOM itself may lead to the formation •OH, indirectly contributing to the degradation of targeted contaminants by participating in secondary reactions and generating additional oxidizing agents. Although many of the unsaturated hydrocarbons in NOM are polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, theoretically, unsaturated bonds are more accessible to oxidize than saturated bonds. However, there is a potential for some unstable chemical bonds to be oxidized into intermediate products that are challenging to degrade when complex unsaturated compounds are reduced to small molecules and combined with other free radicals. Previous results show that NOM contains the main functional groups C = C, C = O, and C–O–C [89]. From Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry (FTICR-MS), the H/C ratio of most molecules in NOM was found to be between 0.3 and 1.8. The H/C ratio of NOM molecules decreases significantly after electrochemical oxidation, primarily between 0.3 and 1.7. It indicates that the extent of NOM unsaturation decreases following the electrochemical oxidation processes. The O/C ratio of most NOM molecules is between 0.05 and 0.8, and the O/C ratio of NOM molecules increases between 0.1 and 0.8, demonstrating that most NOM molecules are oxidized [91]. NOM can form a passivating layer on the electrode surface, which acts as a physical barrier and inhibits the direct contact of contaminants with the electrode. This layer can reduce the electrode’s reactivity and impede targeted contaminant oxidation, making the process less effective. NOM can occupy active sites on the electrode, reducing the availability of these sites for the targeted contaminants. This can hinder the electrooxidation process and decrease the overall efficiency of contaminant removal. Overall, it is crucial to investigate the influence of NOM on the mechanism of the electrochemical oxidation process to degrade PFAS. The effect of NOM on the electrochemical degradation of PFAS is depicted in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Schematic diagram of the NOM effect in the PFAS electrochemical degradation process (Adapted with permission from Lei et al. [92]Elsevier).

A wide variety of electrode materials have often obtained different organic matter efficiencies; however, no comparative benchmark between electrode materials exists for NOM removal. BDD ’nonactive’ anode, a promising anode material for PFAS degradation, is also proven excellent for NOM oxidation [93]. The diamonds in BDD electrodes act as magnetic isolating material, facilitating anodic oxidation in electrochemical water treatment. The hydroxyl radical physically adsorbed on the surface site reacts with organics in the following manner (Eq (21) [81,93],

| (21) |

Additionally, oxygen evolution on inactive electrodes occurs between H2O and BDD(·OH) to form O2 (Eq (22) [94].

| (22) |

For cost-effectiveness, BDD can be replaced by MMO (active anode), as suggested earlier, for the degradation of PFAS [20]. Electrooxidation by BDD and MMO electrodes relies heavily on current density, which is proportional to the number of reactions on the electrode surface. BDD has more active sites than MMO; thus, BDD electrodes showcased a more effective breakdown of NOM [93]. Recently, the EO was used to treat standardized Suwannee River NOM at two different current densities (10 and 20 mA cm−2) and pHs (6.5 and 8.5) [93]. This study showed that BDD electrodes demonstrated higher oxidation of the NOM under a broader range of operating conditions (duration, current, pH). Additionally, BDD-based electrodes had the lowest energy consumption and outperformed MMO electrodes at higher pH and current. On the contrary, the MMO electrode system exhibited improved performance at pH 6.5 and lower current (10 mA cm−2) from 0 to 30 min [93].

6. Challenges in the electro-oxidation approach

The rapid advancement of electrochemical oxidation technology for PFAS degradation is hampered by several essential but commonly disregarded issues. First, this method is ineffective for treating low concentrations (parts per billion) of both long and short chains of PFAS. Second, additional research is needed to understand the synergistic or antagonistic removal mechanism of PFAS in the presence of mixtures of PFAS (i.e., the simultaneous presence of shorter and longer chain PFAS). The proposed technique has been proven for the rapid destruction of high concentration of long-chain PFAS and the profound destruction of organic matter. Still, it faces the challenge of treating short-chain PFAS, where the degradation process is much slower (0.004 mM/h of PFBS vs. 0.0123 mM/h of PFOS in terms of Zeroth order) [95]. Hydrophilicity can be the reason for the this [61]. Shorter chain PFAS are generally more concerning from health and environmental perspectives than longer chain PFAS. They are more water-soluble and have higher bioavailability, meaning living organisms absorb them more easily. Shorter-chain PFAS have been found to bioaccumulate more in organisms than longer-chain PFAS—implying that they can build up in the tissues of living organisms at higher concentrations, increasing the risk of adverse effects. Third, there is a lack of research demonstrating the removal of high PFAS concentration in complex real water matrices, where both organic and inorganic scavengers are present. The fourth issue involves a lack of information on the process’s long-term operation, including lifecycle electrode costs, analyzing process constraints caused by minerals build-up. Fifth possible toxicity concerns (e.g., perchlorate production () during the process). Other anodic materials like PbO2, IrO2, and Ti4O7 also report the formation of during the EO process. This indicates that perchlorate formation is a critical issue in the EO process and is highly challenging. Field demonstration is needed to demonstrate scale-up and optimize process parameters effectively. Finally, the sixth issue is a lack of information on potential PFAS byproducts. It is often seen that incomplete defluorination with PFAS degradation results in fluorinated product formation, which are as persistent or more persistent than parent PFAS. Thus, the transformation product identification and mechanism study during the remediation of PFAS contamination holds special attention.

Multiple processes can be combined to increase efficacy while reducing energy requirements to achieve complete PFAS destruction (including short and long carbon chains at low concentrations). One hybrid treatment system can integrate the electro-oxidation process with advanced reduction technologies that could pave the way for the complete destruction and defluorination of PFAS. EO can effectively break down the long-chain PFAS and has the capability for the destruction of organic matter. In contrast, ARP destroys the residual short-chain PFAS with high efficacy in the absence of natural organic moieties that absorb light and scavenge the aqueous electrons. The potential use of such a hybrid system can be cost-effective for removing PFOS and PFOA with < 20 kWh/m3 to achieve > 90% destruction [96].

7. Conclusions and future perspective

One of the main challenges in predicting and improving treatment conditions is the variability in water composition (e.g., the presence of PFAS compounds in mixtures and at various concentrations). Significant research efforts have been devoted to developing technologies to treat industrial wastewater while considering the system’s technical and financial aspects. Yet, each technique currently used has significant limitations. The EO process has shown to be promising in eliminating persistent contaminants. However, widespread implementation of EO is hampered by poor destruction of short-chain PFAS, its high cost, and electrode lifetimes due to surface fouling by natural water constituents, among other issues. However, EO works efficiently for scissoring the long-chain PFAS and causes profound destruction of organic matter.

Multiple treatment technologies may be needed to effectively treat a mixture of PFAS in complex natural water matrices. A combined system of EOP followed by ARP might work more effectively than an individual one. Advanced reduction processes (ARPs) can be used for the nonselective defluorination of PFAS to nonfluorinated small organics and the fluorine ion due to hydrated electrons (). However, since organic matter is more abundant than PFAS at trace concentrations, they act like scavengers for the generated through ARP. Consequently, the fraction of allocated for the PFAS degradation gets reduced, leading to low treatment efficiency. Therefore, destroying organic matter via EO can help improve the treatment efficiency of ARP. These two technologies working together will have a substantial outcome— high removal rates with minimal expenditure. The two obvious advantages of combining EOP with the ARP are improved radical generation efficiency and enhanced electrode self-cleaning function. Finally, future research should focus on gaining a mechanistic understanding of the role of NOM in the reduction/oxidation of PFAS in a real water system, which can lead to the development of a highly efficient destructive technology for PFAS in the natural environment.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the comments of anonymous reviewers that improve the paper.

8. Disclaimer

The research presented was not performed or funded by EPA and was not subject to EPA’s quality system requirements. The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views or the policies of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- [1].Gagliano E, Sgroi M, Falciglia PP, Vagliasindi FGA, Roccaro P, Removal of poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) from water by adsorption: Role of PFAS chain length, effect of organic matter and challenges in adsorbent regeneration, Water Res. 171 (2020), 115381, 10.1016/j.watres.2019.115381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Schwichtenberg T, Bogdan D, Carignan CC, Reardon P, Rewerts J, Wanzek T, Field JA, PFAS and dissolved organic carbon enrichment in surface water foams on a northern U.S. freshwater lake, Environ Sci Technol. 54 (2020) 14455–14464, 10.1021/acs.est.0c05697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Birch QT, Birch ME, Nadagouda MN, Dionysiou DD, Nano-enhanced treatment of per-fluorinated and poly-fluorinated alkyl substances (PFAS), Curr Opin Chem Eng. 35 (2022), 100779, 10.1016/j.coche.2021.100779. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Gao K, Zhuang T, Liu X, Fu J, Zhang J, Fu J, Wang L, Zhang A, Liang Y, Song M, Jiang G, Prenatal exposure to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) and association between the placental transfer efficiencies and dissociation constant of serum proteins–PFAS complexes, Environ Sci Technol. 53 (2019) 6529–6538, 10.1021/acs.est.9b00715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Lewis R, Johns L, Meeker J, Serum biomarkers of exposure to perfluoroalkyl substances in relation to serum testosterone and measures of thyroid function among adults and adolescents from NHANES 2011–2012, Int J Environ Res Public Health. 12 (2015) 6098–6114, 10.3390/ijerphl20606098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Crawford NM, Fenton SE, Strynar M, Hines EP, Pritchard DA, Steiner AZ, Effects of per fluorinated chemicals on thyroid function, markers of ovarian reserve, and natural fertility, Reproductive Toxicology. 69 (2017) 53–59, 10.1016/j.reprotox.2017.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Domingo JL, Nadal M, Per- and polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) in food and human dietary intake: A review of the recent scientific literature, J Agric Food Chem. 65 (2017) 533–543, 10.1021/acs.jafc.6b04683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Carcinogencity of Perfluoroalkyl Compounds. (2015) 265–304. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Veciana M, Bräunig J, Farhat A, Pype M-L, Freguia S, Carvalho G, Keller J, Ledezma P, Electrochemical oxidation processes for PFAS removal from contaminated water and wastewater: fundamentals, gaps and opportunities towards practical implementation, J Hazard Mater. 434 (2022), 128886, 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2022.128886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Crone BC, Speth TF, Wahman DG, Smith SJ, Abulikemu G, Kleiner EJ, Pressman JG, Occurrence of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in source water and their treatment in drinking water, Crit Rev Environ Sci Technol. 49 (2019) 2359–2396, 10.1080/10643389.2019.1614848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Kothawala DN, Köhler SJ, Östlund A, Wiberg K, Ahrens L, Influence of dissolved organic matter concentration and composition on the removal efficiency of perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) during drinking water treatment, Water Res. 121 (2017) 320–328, 10.1016/j.watres.2017.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Qi Y, Cao H, Pan W, Wang C, Liang Y, The role of dissolved organic matter during Per- and polyfluorinated substance (PFAS) adsorption, degradation, and plant uptake: A review, J Hazard Mater. 436 (2022), 129139, 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2022.129139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Adu O, Ma X, Sharma VK, Bioavailability, phytotoxicity and plant uptake of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS): A review, J Hazard Mater. 447 (2023), 130805, 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2023.130805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Lu D, Sha S, Luo J, Huang Z, Zhang Jackie X, Treatment train approaches for the remediation of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS): A critical review, J Hazard Mater. 386 (2020), 121963, 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.121963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Luft CM, Schutt TC, Shukla MK, Properties and mechanisms for PFAS adsorption to aqueous clay and humic soil components, Environ Sci Technol. 56 (2022) 10053–10061, 10.1021/acs.est.2c00499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Appleman TD, Dickenson ERV, Bellona C, Higgins CP, Nanofiltration and granular activated carbon treatment of perfluoroalkyl acids, J Hazard Mater. 260 (2013) 740–746, 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2013.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Pfotenhauer D, Sellers E, Olson M, Praedel K, Shafer M, PFAS concentrations and deposition in precipitation: An intensive 5-month study at national atmospheric deposition program – national trends sites (NADP-NTN) across Wisconsin, USA, Atmos Environ. 291 (2022), 119368, 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2022.119368. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Xiao F, Simcik MF, Gulliver JS, Mechanisms for removal of perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoate (PFOA) from drinking water by conventional and enhanced coagulation, Water Res. 47 (2013) 49–56, 10.1016/j.watres.2012.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Wen Y, Rentería-Gómez Á, Day GS, Smith MF, Yan T-H, Ozdemir ROK, Gutierrez O, Sharma VK, Ma X, Zhou H-C, Integrated photocatalytic reduction and oxidation of perfluorooctanoic acid by metal-organic frameworks: Key insights into the degradation mechanisms, J Am Chem Soc. 144 (2022) 11840–11850, 10.1021/jacs.2c04341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Duinslaeger N, Radjenovic J, Electrochemical degradation of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) using low-cost graphene sponge electrodes, Water Res. 213 (2022), 118148, 10.1016/j.watres.2022.118148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Ross I, McDonough J, Miles J, Storch P, Thelakkat Kochunarayanan P, Kalve E, Hurst J, Dasgupta SS, Burdick J, A review of emerging technologies for remediation of PFASs, Remediation Journal. 28 (2018) 101–126, 10.1002/rem.21553. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Verma S, Lee T, Sahle-Demessie E, Ateia M, Nadagouda MN, Recent advances on PFAS degradation via thermal and nonthermal methods, Chemical Engineering Journal Advances. 13 (2023), 100421, 10.1016/j.ceja.2022.100421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Lee T, Speth TF, Nadagouda MN, High-pressure membrane filtration processes for separation of Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), Chemical Engineering Journal. 431 (2022), 134023, 10.1016/j.cej.2021.134023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Liu Z, Bentel MJ, Yu Y, Ren C, Gao J, Pulikkal VF, Sun M, Men Y, Liu J, Near-quantitative defluorination of perfluorinated and fluorotelomer carboxylates and sulfonates with integrated oxidation and reduction, Environ Sci Technol. 55 (2021) 7052–7062, 10.1021/acs.est.lc00353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Lutze HV, Brekenfeld J, Naumov S, von Sonntag C, Schmidt TC, Degradation of perfluorinated compounds by sulfate radicals – New mechanistic aspects and economical considerations, Water Res. 129 (2018) 509–519, 10.1016/j.watres.2017.10.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Abdullah AM, Advanced Oxidation Processes for the Remediation of Problematic Organophosphorus Compounds and Perfluoroalkyl Substances, Florida International University, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Dombrowski PM, Kakarla P, Caldicott W, Chin Y, Sadeghi V, Bogdan D, Barajas-Rodriguez F, Chiang S-Y-D, Technology review and evaluation of different chemical oxidation conditions on treatability of PFAS, Remediation Journal. 28 (2018) 135–150, 10.1002/rem.21555. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Drinking Water Health Advisories for PFAS Fact Sheet for Communities, U.S. EPA. (2022). [Google Scholar]

- [29].US Environmental Protection Agency, FACT SHEET PFOA & PFOS Drinking Water Health Advisories, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Radjenovic J, Duinslaeger N, Awal SS, Chaplin BP, Facing the Challenge of poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances in water: Is electrochemical oxidation the answer? Environ Sci Technol. 54 (2020) 14815–14829, 10.1021/acs.est.0c06212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Cui J, Gao P, Deng Y, Destruction of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) with advanced reduction processes (ARPs): A critical review, Environ Sci Technol. 54 (2020) 3752–3766, 10.1021/acs.est.9b05565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Saleem M, Biondo O, Sretenović G, Tomei G, Magarotto M, Pavarin D, Marotta E, Paradisi C, Comparative performance assessment of plasma reactors for the treatment of PFOA; reactor design, kinetics, mineralization and energy yield, Chemical Engineering Journal. 382 (2020), 123031, 10.1016/j.cej.2019.123031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Feng M, Gao R, Staack D, Pillai SD, Sharma VK, Degradation of perfluoroheptanoic acid in water by electron beam irradiation, Environ Chem Lett. 19 (2021) 2689–2694, 10.1007/sl0311-021-01195-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Lassalle J, Gao R, Rodi R, Kowald C, Feng M, Sharma VK, Hoelen T, Bireta P, Houtz EF, Staack D, Pillai SD, Degradation of PFOS and PFOA in soil and groundwater samples by high dose Electron Beam Technology, Radiation Physics and Chemistry. 189 (2021), 109705, 10.1016/j.radphyschem.2021.109705. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Bruton TA, Sedlak DL, Treatment of aqueous film-forming foam by heat-activated persulfate under conditions representative of in situ chemical oxidation, Environ Sci Technol. 51 (2017) 13878–13885, 10.1021/acs.est.7b03969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Zhang Y, Moores A, Liu J, Ghoshal S, New insights into the degradation mechanism of perfluorooctanoic acid by persulfate from density functional theory and experimental data, Environ Sci Technol. 53 (2019) 8672–8681, 10.1021/acs.est.9b00797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Duan L, Wang B, Heck K, Guo S, Clark CA, Arredondo J, Wang M, Senftle TP, Westerhoff P, Wen X, Song Y, Wong MS, Efficient photocatalytic PFOA degradation over boron nitride, Environ Sci Technol Lett. 7 (2020) 613–619, 10.1021/acs.estlett.0c00434. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Wang JL, Xu LJ, Advanced oxidation processes for wastewater treatment: Formation of hydroxyl radical and application, Crit Rev Environ Sci Technol. 42 (2012) 251–325, 10.1080/10643389.2010.507698. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [39].McBeath ST, Graham NJD, Degradation of perfluorooctane sulfonate via in situ electro-generated ferrate and permanganate oxidants in NOM-rich source waters, Environ Sci (Camb). 7 (2021) 1778–1790, 10.1039/DlEW00399B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Ryan DR, Mayer BK, Baldus CK, McBeath ST, Wang Y, McNamara PJ, Electrochemical technologies for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances mitigation in drinking water and water treatment residuals, AWWA Water Sci. 3 (2021), 10.1002/aws2.1249. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Rayaroth MP, Aravindakumar CT, Shah NS, Boczkaj G, Advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) based wastewater treatment - unexpected nitration side reactions - a serious environmental issue: A review, Chemical Engineering Journal. 430 (2022), 133002, 10.1016/j.cej.2021.133002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Zhang S, Hao Z, Liu J, Gutierrez L, Croué J-P, Molecular insights into the reactivity of aquatic natural organic matter towards hydroxyl (•OH) and sulfate (SO4•–) radicals using FT-ICR MS, Chemical Engineering Journal. 425 (2021), 130622, 10.1016/j.cej.2021.130622. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Guerra-Rodríguez S, Rodríguez E, Singh D, Rodríguez-Chueca J, Assessment of sulfate radical-based advanced oxidation processes for water and wastewater treatment: A review, Water (Basel). 10 (2018) 1828, 10.3390/w10121828. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Wacławek S, Lutze H.v., Sharma VK, Xiao R, Dionysiou DD, Revisit the alkaline activation of peroxydisulfate and peroxymonosulfate, Curr Opin Chem Eng. 37 (2022) 100854, 10.1016/j.coche.2022.100854. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Mitchell SM, Ahmad M, Teel AL, Watts RJ, Degradation of perfluorooctanoic acid by reactive species generated through catalyzed H 2 o 2 propagation reactions, Environ Sci Technol Lett. 1 (2014) 117–121, 10.1021/ez4000862. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Särkkä H, Vepsäläinen M, Sillanpää M, Natural organic matter (NOM) removal by electrochemical methods — A review, Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry. 755 (2015) 100–108, 10.1016/j.jelechem.2015.07.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Trautmann AM, Schell H, Schmidt KR, Mangold K-M, Tiehm A, Electrochemical degradation of perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in groundwater, Water Science and Technology. 71 (2015) 1569–1575, 10.2166/wst.2015.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Schaefer CE, Andaya C, Urtiaga A, McKenzie ER, Higgins CP, Electrochemical treatment of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS) in groundwater impacted by aqueous film forming foams (AFFFs), J Hazard Mater. 295 (2015) 170–175, 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2015.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Fang C, Megharaj M, Naidu R, Electrochemical advanced oxidation processes (EAOP) to degrade per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs), Journal of Advanced Oxidation Technologies. 20 (2017), 10.1515/jaots-2017-0014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Nienhauser AB, Ersan MS, Lin Z, Perreault F, Westerhoff P, Garcia-Segura S, Boron-doped diamond electrodes degrade short- and long-chain per- and polyfluorinated alkyl substances in real industrial wastewaters, J Environ Chem Eng. 10 (2022), 107192, 10.1016/j.jece.2022.107192. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Soriano A, Schaefer C, Urtiaga A, Enhanced treatment of perfluoroalkyl acids in groundwater by membrane separation and electrochemical oxidation, Chemical Engineering Journal Advances. 4 (2020), 100042, 10.1016/j.ceja.2020.100042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Maldonado VY, Becker MF, Nickelsen MG, Witt SE, Laboratory and semi-pilot scale study on the electrochemical treatment of perfluoroalkyl acids from ion exchange still bottoms, Water (Basel). 13 (2021) 2873, 10.3390/wl3202873. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Liang S, David Pierce R, Lin H, Chiang S-YD, Jack Huang Q, Electrochemical oxidation of PFOA and PFOS in concentrated waste streams, Remediation Journal. 28 (2018) 127–134, 10.1002/rem.21554. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Lin H, Niu J, Xu J, Huang H, Li D, Yue Z, Feng C, Highly efficient and mild electrochemical mineralization of long-chain perfluorocarboxylic acids (C9–C10) by Ti/SnO 2 –Sb–Ce, Ti/SnO 2 –Sb/Ce–PbO 2, and Ti/BDD electrodes, Environ Sci Technol. 47 (2013) 13039–13046, 10.1021/es4034414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Su Y, Rao U, Khor CM, Jensen MG, Teesch LM, Wong BM, Cwiertny DM, Jassby D, Potential-driven electron transfer lowers the dissociation energy of the C-F bond and facilitates reductive defluorination of perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS), ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 11 (2019) 33913–33922, 10.1021/acsami.9bl0449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Zhuo Q, Deng S, Yang B, Huang J, Yu G, Efficient electrochemical oxidation of perfluorooctanoate using a Ti/SnO 2 -Sb-Bi anode, Environ Sci Technol. 45 (2011) 2973–2979, 10.1021/esl024542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Deng Y, Liang Z, Lu X, Chen D, Li Z, Wang F, The degradation mechanisms of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS) by different chemical methods: A critical review, Chemosphere. 283 (2021), 131168, 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.131168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Ahmed MB, Alam MM, Zhou JL, Xu B, Johir MAH, Karmakar AK, Rahman MS, Hossen J, Hasan ATMK, Moni MA, Advanced treatment technologies efficacies and mechanism of per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances removal from water, Process Safety and Environmental Protection. 136 (2020) 1–14, 10.1016/j.psep.2020.01.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Pica NE, Funkhouser J, Yin Y, Zhang Z, Ceres DM, Tong T, Blotevogel J, Electrochemical oxidation of hexafluoropropylene oxide dimer acid (GenX): Mechanistic insights and efficient treatment train with nanofiltration, Environ Sci Technol. 53 (2019) 12602–12609, 10.1021/acs.est.9b03171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Radjenovic J, Sedlak DL, Challenges and opportunities for electrochemical processes as next-generation technologies for the treatment of contaminated water, Environ Sci Technol. 49 (2015) 11292–11302, 10.1021/acs.est.5b02414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Zhuo Q, Deng S, Yang B, Huang J, Wang B, Zhang T, Yu G, Degradation of perfluorinated compounds on a boron-doped diamond electrode, Electrochim Acta. 77 (2012) 17–22, 10.1016/j.electacta.2012.04.145. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Gandini D, Oxidation of carboxylic acids at boron-doped diamond electrodes for wastewater treatment, J Appl Electrochem. 30 (2000) 1345–1350, 10.1023/A:1026526729357. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Uwayezu JN, Carabante I, Lejon T, van Hees P, Karlsson P, Hollman P, Kumpiene J, Electrochemical degradation of per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances using boron-doped diamond electrodes, J Environ Manage. 290 (2021), 112573, 10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.112573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Chaplin BP, The prospect of electrochemical technologies advancing worldwide water treatment, Acc Chem Res. 52 (2019) 596–604, 10.1021/acs.accounts.8b00611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Qing G, Anari Z, Foster SL, Matlock M, Thoma G, Greenlee LF, Electrochemical disinfection of irrigation water with a graphite electrode flow cell, Water Environment Research. 93 (2021) 535–548, 10.1002/wer.1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Can OT, Gazigil L, Keyikoglu R, Treatment of intermediate landfill leachate using different anode materials in electrooxidation process, Environ Prog Sustain Energy. 41 (2022), 10.1002/ep.13722. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Niu J, Lin H, Xu J, Wu H, Li Y, Electrochemical mineralization of perfluorocarboxylic acids (PFCAs) by Ce-doped modified porous nanocrystalline PbO 2 film electrode, Environ Sci Technol. 46 (2012) 10191–10198, 10.1021/es302148z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Li X, Pletcher D, Walsh FC, Electrodeposited lead dioxide coatings, Chem Soc Rev. 40 (2011) 3879, 10.1039/c0cs00213e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Chaplin BP, Critical review of electrochemical advanced oxidation processes for water treatment applications, Environ. Sci.: Processes Impacts 16 (2014) 1182–1203, 10.1039/C3EM00679D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Yang B, Jiang C, Yu G, Zhuo Q, Deng S, Wu J, Zhang H, Highly efficient electrochemical degradation of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) by F-doped Ti/SnO2 electrode, J Hazard Mater. 299 (2015) 417–424, 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2015.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Le TXH, Haflich H, Shah AD, Chaplin BP, Energy-efficient electrochemical oxidation of perfluoroalkyl substances using a Ti 4 O 7 reactive electrochemical membrane anode, Environ Sci Technol Lett. 6 (2019) 504–510, 10.1021/acs.esdett.9b00397. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Huang D, Wang K, Niu J, Chu C, Weon S, Zhu Q, Lu J, Stavitski E, Kim J-H, Amorphous Pd-loaded Ti 4 O 7 electrode for direct anodic destruction of perfluorooctanoic acid, Environ Sci Technol. 54 (2020) 10954–10963, 10.1021/acs.est.0c03800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Lin H, Xiao R, Xie R, Yang L, Tang C, Wang R, Chen J, Lv S, Huang Q, Defect engineering on a Ti 4 O 7 electrode by Ce 3+ doping for the efficient electrooxidation of perfluorooctanesulfonate, Environ Sci Technol. 55 (2021) 2597–2607, 10.1021/acs.est.0c06881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Xie J, Ma J, Zhang C, Kong X, Wang Z, Waite TD, Effect of the Presence of Carbon in Ti4O7 Electrodes on Anodic Oxidation of Contaminants, Environ Sci Technol 54 (2020) 5227–5236, 10.1021/acs.est.9b07398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Wang Y, Han P, Lv X, Zhang L, Zheng G, Defect and Interface Engineering for Aqueous Electrocatalytic CO2 Reduction, Joule 2 (2018) 2551–2582, 10.1016/j.joule.2018.09.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Li H, Liu G, Zhou B, Deng Z, Wang Y, Ma L, Yu Z, Zhou K, Wei Q, Periodic porous 3D boron-doped diamond electrode for enhanced perfluorooctanoic acid degradation, Sep Purif Technol. 297 (2022), 121556, 10.1016/j.seppur.2022.121556. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Xu Z, Yu Y, Liu H, Niu J, Highly efficient and stable Zr-doped nanocrystalline PbO2 electrode for mineralization of perfluorooctanoic acid in a sequential treatment system, Science of The Total Environment. 579 (2017) 1600–1607, 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.ll.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Lin H, Niu J, Liang S, Wang C, Wang Y, Jin F, Luo Q, Huang Q, Development of macroporous Magnéli phase Ti4O7 ceramic materials: As an efficient anode for mineralization of poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances, Chemical Engineering Journal. 354 (2018) 1058–1067, 10.1016/j.cej.2018.07.210. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Lin H, Niu J, Ding S, Zhang L, Electrochemical degradation of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) by Ti/SnO2–Sb, Ti/SnO2–Sb/PbO2 and Ti/SnO2–Sb/MnO2 anodes, Water Res. 46 (2012) 2281–2289, 10.1016/j.watres.2012.01.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Medel A, Treviño-Reséndez J, Brillas E, Meas Y, Sirés I, Contribution of cathodic hydroxyl radical generation to the enhancement of electro-oxidation process for water decontamination, Electrochim Acta. 331 (2020), 135382, 10.1016/j.electacta.2019.135382. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Marselli B, Garcia-Gomez J, Michaud P-A, Rodrigo MA, Comninellis C.h., Electrogeneration of hydroxyl radicals on boron-doped diamond electrodes, J Electrochem Soc. 150 (2003) D79, 10.1149/l.1553790. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Garcia-Costa AL, Savall A, Zazo JA, Casas JA, Groenen Serrano K, On the role of the cathode for the electro-oxidation of perfluorooctanoic acid, Catalysts. 10 (2020) 902, 10.3390/catall0080902. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Zhu J, Chen Y, Gu Y, Ma H, Hu M, Gao X, Liu T, Feasibility study on the electrochemical reductive decomposition of PFOA by a Rh/Ni cathode, J Hazard Mater. 422 (2022), 126953, 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.126953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Wan Z, Cao L, Huang W, Zheng D, Li G, Zhang F, Enhanced electrochemical destruction of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) aided by overlooked cathodically produced bubbles, Environ Sci Technol Lett. 10 (2023) 111–116, 10.1021/acs.estlett.2c00897. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Meng P, Deng S, Lu X, Du Z, Wang B, Huang J, Wang Y, Yu G, Xing B, Role of air bubbles overlooked in the adsorption of perfluorooctanesulfonate on hydrophobic carbonaceous adsorbents, Environ Sci Technol. 48 (2014) 13785–13792, 10.1021/es504108u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Trellu C, Chaplin BP, Coetsier C, Esmilaire R, Cerneaux S, Causserand C, Cretin M, Electro-oxidation of organic pollutants by reactive electrochemical membranes, Chemosphere. 208 (2018) 159–175, 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Zaky AM, Chaplin BP, Porous substoichiometric TiO 2 anodes as reactive electrochemical membranes for water treatment, Environ Sci Technol. 47 (2013) 6554–6563, 10.1021/es401287e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Shi H, Wang Y, Li C, Pierce R, Gao S, Huang Q, Degradation of perfluorooctanesulfonate by reactive electrochemical membrane composed of magnéli phase titanium suboxide, Environ Sci Technol. 53 (2019) 14528–14537, 10.1021/acs.est.9b04148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Luo M, Wang Z, Zhang C, Song B, Li D, Cao P, Peng X, Liu S, Advanced oxidation processes and selection of industrial water source: A new sight from natural organic matter, Chemosphere. 303 (2022), 135183, 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.135183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Pavitt AS, Tratnyek PG, Electrochemical characterization of natural organic matter by direct voltammetry in an aprotic solvent, Environ Sci Process Impacts. 21 (2019) 1664–1683, 10.1039/C9EM00313D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Du Y, Deng Y, Ma T, Xu Y, Tao Y, Huang Y, Liu R, Wang Y, Enrichment of geogenic ammonium in quaternary alluvial-lacustrine aquifer systems: evidence from carbon isotopes and DOM characteristics, Environ Sci Technol. 54 (2020) 6104–6114, 10.1021/acs.est.0c00131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Lei X, Lian Q, Zhang X, Karsili TK, Holmes W, Chen Y, Zappi ME, Gang DD, A review of PFAS adsorption from aqueous solutions: Current approaches, engineering applications, challenges, and opportunities, Environmental Pollution. 321 (2023), 121138, 10.1016/j.envpol.2023.121138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Snowdon MR, Rathod S, Fattahi A, Khan A, Bragg LM, Liang R, Zhou N, Servos MR, Water purification and electrochemical oxidation: Meeting different targets with BDD and MMO anodes, Environments. 9 (2022) 135, 10.3390/environments9110135. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [94].da Silva SW, Navarro EMO, Rodrigues MAS, Bernardes AM, Pérez-Herranz V, Using p-Si/BDD anode for the electrochemical oxidation of norfloxacin, Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry. 832 (2019) 112–120, 10.1016/j.jelechem.2018.10.049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Liao Z, Farrell J, Electrochemical oxidation of perfluorobutane sulfonate using boron-doped diamond film electrodes, J Appl Electrochem. 39 (2009) 1993–1999, 10.1007/sl0800-009-9909-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Yang Yang, Deep destruction of PFAS in complicated water matrices by integrated electrochemical oxidation and UV-sulfite reduction, 2022. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.