Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The prevalence of uric acid (UA) stones increases regularly due to its high correlation with obesity, hypertension, metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, and aging. Uric acid stone formation is mainly due to an acidic urinary pH secondary to an impaired urinary ammonium availability responsible for UA rather than soluble urate excretion. Alkalization of urine is therefore advocated to prevent UA crystallization and considered effective therapy.

METHODS

We report a large series of 120 patients with UA lithiasis who were successfully treated with potassium (K)-citrate for stone dissolution (n=75) and/or stone recurrence prevention (n=45) without any urologic intervention, with a median 3.14 years followup. The K-citrate was diluted in 1.5 L of water, avoiding gastrointestinal disorders.

RESULTS

Among 75 patients having stones in their kidney at initiation of therapy, a complete chemolysis was obtained in 88% of cases. Stone risk factors decreased under treatment, mainly due to increased diuresis, urinary pH, and citrate excretion. Treatment was stopped in only 2% of patients due to side effects, with no hyperkalemia onset despite a median urinary potassium increase of 44 mmol/day.

CONCLUSIONS

Contrary to other reports, our data show that medical treatment of UA kidney stones is well-tolerated and efficient if regular monitoring of urinary pH is performed.

INTRODUCTION

Urolithiasis is one of the most frequent diseases treated by urologists. The prevalence is 5–13% across European countries, 10% in France,1 and 13% in the U.S.2 Calcium oxalate is the most frequent component (occurring in approximately 70%) of kidney stones;1 however, uric acid (UA) stones are becoming more and more frequent, and currently account for about 10% of all stones. This increased frequency is due to an the higher prevalence of type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and obesity in the general population over the last 30 years.1 Further, the risk of UA stones increases with age1: 23% vs. 6%, respectively, after or before 55 years of age in our study, especially in men. Uric acid stones are also highly recurrent.3

The consequences of calculi can be severe. In addition to painful nephritic colic, they can lead to infection, septic shock, or renal insufficiency.

In terms of treatment, although surgery has greatly progressed — with the use of extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy, percutaneous nephrolithotomy, and flexible ureteroscopy — nephrolithiasis can lead to complications such as hemorrhage, rupture or stenosis of the ureter, and urinary tract infection. In addition, the overall cost of urologic procedures for stone removal is high — more than two billion dollars each year in the U.S.4 Fortunately, UA stones are accessible to medical dissolving treatment; 5–8 however, only very few series of UA stones have been reported as successfully managed by medical therapy; these occurrences are often associated with a significant part of treatment failure.9–11

We report the clinical experience of a single center cohort of 120 patients followed for UA nephrolithiasis between 2017 and 2021. We studied the effect of potassium (K)-citrate for the dissolution of UA calculi in the kidney and for the prevention of new calculi.

METHODS

Patients

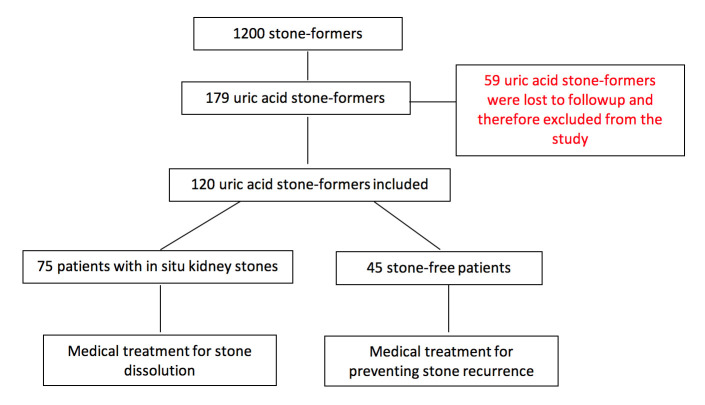

Among a cohort of 1200 patients followed for urolithiasis, 179 patients had UA stones. The diagnosis of UA stones was based on computed tomography (CT) scan imaging, previous stone analysis by infrared spectroscopy or crystalluria (when no stone was available for analysis), and/or acidic urine pH value (<5.4 on morning fasting urine collection). All participants gave their written informed consent. In line with the French legislation on observational studies of routine clinical practice, approval by an institutional review board was not required. Patients were treated with tripotassium citrate (K-citrate) either for dissolving their stone or to prevent recurrence. Fifty-nine patients were excluded because they were lost to followup; thus, 120 patients (88 men and 32 women) were included (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study flow chart.

Radiologic exams

The diagnosis of UA stones is not always obvious because they are radiolucent with plain abdominal X-rays, similar to calculi made of 2.8 dihydroxyadenine, drug, or proteins.

A low-dose non-contrast enhanced CT (NCCT) or simple CT scan was performed in all patients to see the location, number, and density of calculi. Pure UA stones have a low density of <400 Hounsfield units (HU).6

In our series, although the median density was quote low at 431±74 HU (range 319–560), CT did not allow for distinction between UA, dihydroxyadenine, drug, and protein stones; therefore, we made the determination of UA stone via stone analysis and/or crystalluria.

Stone analysis and crystalluria

Stone analysis was performed by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy.12 In case of patient relapse, if the stone was collected, a new analysis was performed for assessing the potential presence of calcium or urate salts due to an excessive alkaline therapy.

If no stone was available for analysis, a study of crystalluria on the first morning urine with a measure of urinary pH was performed to determine the type of UA crystal in urine (types include amorphous UA, UA anhydrous, UA monohydrate, and UA dihydrate).13

Urinary pH

Urinary pH was performed in all cases, as it is a corner-stone for the diagnosis and treatment of UA lithiasis. Indeed, urinary pH is expected to be acidic at <5.4, and in some cases, <5.0. The pH must be verified in the first morning urine in a fasting patient. Patients were advised to use a pH meter with a precision of 0.1 unit, which was preferred to colored strips (precise only to 0.5 unit). The pH meter device most used was the Checker portable pH meter HI98103, with a HI 1270 electrode (Hanna Instruments, Lingo Tanneries, France). Urine pH was determined three times a day before meals for at least two days before and after the beginning of treatment.

Urinary pH measurement and crystalluria were performed regularly during followups in order to check alkalization therapy efficiency. Crystalluria is expected to disappear under treatment.

Patient medication management

Seventy-five patients with in situ kidney stones at the beginning of the study underwent medical therapy to dissolve UA stones. In order to alkalize patients’ urine, K-citrate was used because it has been reported as efficient for both dissolving existing calculi and preventing the formation of new UA stones.14

Because no marketed drug was available in France, K-citrate was prescribed as a preparation containing 4–9 g (mean=7.2±1.8 g, i.e., 23.5±5.9 mmoles) or 39–87 mEq per day (mean=70.5±17.7 mEq) diluted in 1.5 L of water and taken throughout the day. The main objective was to permanently obtain a urine pH from 6.0–7.0 to avoid crystallization of urate salts or calcium phosphates. In patients with in situ UA stones, the target of urine pH during K-citrate treatment was 6.5–7.0. When K-citrate was prescribed for preventing stone recurrence in stone-free patients, the target of urine pH was 6.0–6.5. Recurrence rate was defined as the formation of new stone/patient/year.

Patient monitoring relied on a close self-followup; at the start of treatment, patients were sending their urine pH data — checked three times a day over two days — to the medical team via email, so that treatment could be adjusted as necessary. Adjustment of K-citrate dosage was made according to the urine pH value (Table 1).

Table 1.

Adjustment of K-citrate dose according to urine pH (urine pH was measured three times a day before meals)

| Daily pH readings | Adjustment | |

|---|---|---|

| Three pH <6.5 |

|

the dose of K-citrate by 1–3 g more |

| One pH <6.5 |

|

the intake of water with K-citrate for the same period on the next day |

| Three pH between 6.5 and 7.0 |

|

the patient goes on drinking water with K-citrate in the same way |

| One pH > 7.0 |

|

the intake of water with K-citrate for the same period on the next day |

| Three pH >7.0 |

|

the dose of K-citrate by 1–3 g less |

At baseline, hyperuricemia (>460 μmol/l in men, >400 μmol/l in women) and/or hyperuraturia (>4.2 mmol/d in men, >3.6 mmol/d in women) was found in 49% of cases. In such cases, allopurinol was administered (100 mg tapered up to 300 mg per day according to uricemia target). Among our population, 45% of patients received both K-citrate and allopurinol. No case of hyperkaliemia was noticed (all patients had a glomerular filtration rate [GFR] >30 ml/mm).

In addition, because stone formation is favored by inappropriate dietary habits, patients were advised to reduce proteins intake (0.8–1 g/kg/d), purine-rich foods, and sodium chloride intake (<9 g/d) in agreement with the 2022 recommendations of the Association Française d’Urologie (AFU) Lithiasis Committee.15 Proteins and sodium chloride intake was assessed from 24h-urine excretion of urea and sodium.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were described as numbers and percentage and continuous variables as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Comparison of biological data before and during therapy were performed using paired t-test and the Chi-squared test for quantitative and qualitative variables, respectively.

RESULTS

Patient average age was 63±12 years, with a male-to-female ratio of 2.7. Table 2 shows patients’ clinical and biological characteristics at baseline, with obesity, hypertension, and diabetes present in 40%, 38%, and 25% of cases, respectively.

Table 2.

Demographic, clinical, and biological data at baseline

| Patient characteristics | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Number of uric acid stone formers | 120 |

|

| |

| Gender (M/F) | 88/32 |

|

| |

| Frequency of stone recurrence (number/patient/year) | 1.29±1.07 |

|

| |

| Median age | 63±12 |

|

| |

| BMI (kg/m 2 ) | 28.9±6.25 |

| Obesity (≥30 kg/m2) | 40% |

| Moderate (<40 kg/m2) | 34% |

| Severe (≥40 kg/m2) | 6% |

|

| |

| Hypertension | 38% |

|

| |

| Diabetes type 2 | 25% |

|

| |

| Occurrence of hyperuricemia | 42% |

|

| |

| Malformative uropathy (no case of polycystic kidney disease or MSK) | 5% |

|

| |

| Median density at CT scan (Hounsfield units) | 431±74 |

|

| |

| First diagnosis of uric acid lithiasis performed by: | |

| Stone analysis | 83% |

| Urinary uric acid crystals (and pH <5.4) | 17% |

|

| |

| Number of patients with in situ stones | 75 |

|

| |

| Number of patients free of stones at the beginning of K-citrate | 45 |

|

| |

| Biochemistry at baseline | |

|

| |

| Blood | |

| Creatinine (mmol/l) | 92.9±19.5 |

| Uric acid (mmol/l) | 368 ±89 |

| Potassium (mmol/l) | 4.21±0.30 |

| Bicarbonate (mmol/l) | 28±2.5 |

|

| |

| 24h-urine biochemistry | |

| Urine volume (L/day) | 1.70±0.46 |

| Creatinine (mmol/d) | 12.94±3.26 |

| Uric acid (mmol/d) | 4.0±1.2 |

| Potassium (mmol/d) | 66.7±23.9 |

| Sodium (mmol/d) | 195±58 |

| Urea (mmol/d) | 425±118 |

| Citrate (mmol/d) | 2.46±1.20 |

|

| |

| Occurrence of high urine sodium excretion (>150 mmol/d) | 77% |

|

| |

| Occurrence of hyperuricosuria (>4.2 mmol/d in men, >3.8 mmol/d in women) | 43% |

|

| |

| Occurrence of hypocitraturia (<1.6 mmol/d) | 27% |

|

| |

| First morning urine | |

| Urine pH <5.4 | 100% |

BMI: body mass index; CT: computed tomography; MSK: musculoskeletal.

Comparison at baseline between diabetic patients (n=33), who are known to be prone to UA urolithiasis, 16–18 and non-diabetic patients (n=87) only shows a small increase of urinary sodium (216±64 mmol/d vs. 187±57 mmol/d, p<0.05) and potassium (75±21 mmol/d vs. 64±22 mmol/d, p<0.05) excretion and a significant increase of oxalate excretion (0.36±0.14 vs. 0.29±0.11 mmol/24h, p< 0.01) in the diabetic group. No significant difference was found for other urine parameters, and diuresis was similar in both groups (1.8±0.47 in diabetics vs. 1.7±0.46 L/d in non-diabetics, p=non-significant).

Uric acid stones outcome

The average number of stones before treatment was 6.11±5.37 per patient. At the beginning of the treatment, 75 patients (63%) had one or several calculi in their kidneys and 45 patients were stone-free and received K-citrate to prevent stone recurrence.

Stone analysis showed that 48% of stones were pure UA anhydrous, 43% contain UA anhydrous mixed with UA dihydrate, and 9% contain UA anhydrous mixed with <10% of calcium oxalate monohydrate. All patients received K-citrate at a dosage required to reach urinary pH targets. Among them, 66 patients received only K-citrate while 54 patients received K-citrate + allopurinol because of hyperuricemia or hyperuricosuria. Mixed stones with a calcium oxalate shell, found in only two patients, were accessible to alkaline-dissolving therapy after treatment with extracorporeal lithotripsy.

K-citrate was well-tolerated in 91% and moderately tolerated in only 9% of cases. In cases of gastrointestinal disorders, K-citrate dosage was decreased and, when possible, slowly tapered up to reach the target urinary pH.

The mean followup during K-citrate treatment was 3.14±2.73 years. Stone recurrence was assessed from either the spontaneous passage of new stones or through the presence of new stones on a new low-dose CT scan performed each year. The recurrence rate dropped from 1.29±1.07 at baseline to 0.03±0.02 calculus/patient/year with K-citrate. Three relapses were observed during followup due to K-citrate withdrawal.

There was no difference between the cohorts of patients receiving K-citrate alone or combined with allopurinol: the recurrent rate was 0.032±0.199 calculus/patient/year with K-citrate alone and 0.028±0.210 calculus/patient/year with K-citrate and allopurinol. Among the 75 patients with a renal stone at baseline, stone number within patients ranged from 1–10 (n=2.20±0.20). Staghorn calculi were present in 11 patients, seven of whom were treated with K-citrate alone and the other four with K-citrate and allopurinol.

A complete dissolution was obtained in 88% of the patients (Figure 2). Partial dissolution was obtained in 12% of patients in whom stone density was >500 HU (corresponding to presence of another component in the calculus, most often calcium oxalate monohydrate).

Figure 2.

Computed tomography scans of two patients’ before (left) and after 3 months of K-citrate treatment (right) showing the dissolution of calculi.

To ensure that the patient complied with the K-citrate protocol, urinary potassium, which is easy to measure, was checked rather than 24-hour citraturia, which is less reliable and less precise.

Biological followup

Before treatment with K-citrate, hypocitraturia (<1.6 mmol/d) was found in 27% of patients, without any difference in the number of calculi per year (1.19±0.95 stone/year vs. 1.32±1.16/year in patients with citrate >1.6 mmol/d, p=non-significant). Protein intake, checked by the dosage of urea, was increased in 73% of cases. Of note, acidic fasting urine pH <5.4 was present in all cases. During treatment, citraturia increased in all cases. No change was observed for 24-hour urine sodium and urea (Table 3). As expected, urinary potassium was increased in all patients.

Table 3.

Biological parameters (24h-urine and blood) for the whole series of patients before and during K-citrate

| Diuresis (L) | Before K-citrate | During K-citrate | p |

| 24h urine | |||

| 1.70±0.46 | 1.95±0.45 | <0.003 | |

| Creatinine (mmol) | 12.95±3.27 | 12.86±3.46 | NS |

| UpH | 5.19±0.35 | 6.25±0.50 | <0.001 |

| Uric acid crystalluria | 47% | 0% | <0.001 |

| Potassium (mmol) | 67±24 | 116±29 | <0.001 |

| Citrate (mmol) | 2.35±1.15 | 3.92±1.32 | <0.001 |

| Uric acid (mmol) | 4.01±1.22 | 3.07±0.92 | <0.001 |

| Urea (mmol) | 425±118 | 412±105 | NS |

| Phosphorus (mmol) | 28.0±7.55 | 27.4±7.27 | NS |

| Magnesium (mmol) | 3.34±1.39 | 3.52±1.29 | NS |

| Sodium (mmol) | 195±57 | 192±59 | NS |

| Blood | p | ||

| Creatinine (micromol) | 92.9±19.5 | 91.2±23.0 | NS |

| Potassium (mmol) | 4.21±0.30 | 4.50±0.34 | <0.001 |

| Uric acid (mmol) | 368±89 | 302±75 | <0.001 |

| Bicarbonate (mmol) | 28.0±2.5 | 28.7±2.0 | NS |

NS: non-significant.

In some cases, we observed an improvement of the GFR, probably due to the dissolution of calculi. This was particularly noteworthy in patients with staghorn stones. No case of hyperkalemia was observed during followup.

Tables 4 and 5 show the biological followup according to treatments, i.e., K-citrate group alone (Table 4) or K-citrate plus allopurinol group (Table 5). We observed a significant increase of 24-hour diuresis, potassium, citrate, and urine pH, and a significant decrease of urate in both groups, whereas a decrease of urea and sodium excretion was noticed only in K-citrate alone group, suggesting no significant changes in dietary habits in patients receiving both K-citrate and allopurinol.

Table 4.

Biological parameters in 24h-urine before and during K-citrate alone (n=66)

| Per 24 hours | Before K-citrate | During K-citrate | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diuresis (L/d) | 1.61±0.48 | 1.90±0.48 | <0.003 |

| Creatinine (mmol/d) | 12.78±3.09 | 12.05±3.04 | NS |

| UpH | 5.21±0.36 | 6.21±0.48 | <0.001 |

| Potassium (mmol/d) | 66±26 | 109±25 | <0.001 |

| Citrate (mmol/d) | 2.20±1.03 | 3.56±1.20 | <0.001 |

| Urate (mmol/d) | 3.78±1.21 | 3.11±0.89 | <0.001 |

| Phosphate (mmol/d) | 26.7±7.2 | 24.4±6.1 | <0.05 |

| Urea (mmol/d) | 408±113 | 360±107 | <0.05 |

| Sodium (mmol/d) | 181±57 | 164±56 | <0.003 |

NS: non-significant.

Table 5.

Biological parameters in 24h-urine before and during K-citrate and allopurinol treatment (n=54)

| Per 24 hours | Before K-citrate | During K-citrate | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diuresis (L/d) | 1.81±0.42 | 2.01±0.45 | <0.003 |

| Creatinine (mmol/d) | 13.14±3.49 | 13.77±3.70 | NS |

| UpH | 5.16±0.34 | 6.28±0.52 | <0.001 |

| Potassium (mmol/d) | 69±21 | 125±29 | <0.001 |

| Citrate (mmol/d) | 2.52±1.25 | 3.56±1.20 | <0.001 |

| Urate (mmol/d) | 4.29±1.19 | 3.04±0.96 | <0.001 |

| Phosphate (mmol/d) | 29.4±8.4 | 30.4±7.7 | NS |

| Urea (mmol/d) | 448±123 | 468±98 | NS |

| Sodium (mmol/d) | 212±53 | 210±54 | NS |

NS: non-significant.

DISCUSSION

It is well-known that factors promoting UA crystallization include an overly acidic urinary pH (UpH), hyperuricosuria, and insufficient diuresis.8–10 It has been shown that the main factor for UA stone formation is obesity responsible for metabolic syndrome and inducing insulin resistance, resulting in decreased ammonia availability and low urine pH.14,19,20

From an epidemiologic standpoint, UA calculi are increasing in most countries due to changes in dietary habits and the progressive increase in body mass index of the general population. In our series, 40% of UA stone-formers were obese. In such conditions, the most important factor for the lithogenesis of UA stones is the acidic urinary pH<5.4,7,17,20–22

Because acidic urine is the main factor for UA formation, alkalizing treatment was successfully proposed for medical stone dissolution.7,23 Bicarbonate or citrate salts were used, with variable results.5,8

In our study, investigating the risk of renal stone recurrence under K-citrate therapy and the success rate of chemolysis in 75 patients with renal UA stones, a complete dissolution was obtained in 88% and partial dissolution in 12%. All the staghorn calculi were dissolved. The reported success rates of oral dissolution therapy in the literature ranges from 15–87%.10,11,24–30

In the recent review by Ong et al, including 1075 patients, the complete or partial dissolution rates were 61.7% and 19.8%, respectively, while 15.7% of patients required surgical intervention.30 Of note, medical treatment of UA stones is more cost-effective than surgical treatment, as clearly shown by Nevo et al.31

Regarding the biological exams, we had no case of hyperkalemia, even in the case of moderate renal insufficiency, and no case of metabolic alkalosis under K-citrate treatment. On the contrary, in some cases, we observed an improvement of the GFR. A durable alkalization and citraturic response were shown to be achieved long-term with K-citrate.32 The dosage of K-citrate at the initiation of the treatment was dependent on three factors: the weight of the patient, the acidity of the urine (dosage was different if basal urine pH was 4.8 or 5.4), and stone disease status (number of calculi per year, the presence or not of stones in the kidney, with or without staghorn).

Currently, a urinary pH of 6.5–7.2 is recommended for the treatment of UA stones11,33 and pH levels of 7.0–7.2 for dissolution.25 To avoid the risk of calcium phosphate precipitation, we recommended a pH range of 6.5–7.0, which was sufficient for a successful dissolution of the stones, and 6.0–6.5 for the prevention of a new calculus.

As reported by Cameron et al, the monitoring of the response to alkali therapy with only one 24-hour urinary pH measurement during followup is not enough because excessive nocturnal and early morning acidity can persist despite apparent alkalization of pooled 24-hour urines.22 As such, a low-dose CT scan and 24-hour urine collection were performed every six months after the start of treatment in order to ensure that calculi were dissolved and that there was no recurrence. In addition, the scans allowed us to check treatment compliance, assessed by an increased kaliuresis.

Tolerance was good in 91% of patients, which is higher than in other studies.10,34 K-citrate was stopped due to gastrointestinal side effects in only 2% of patients. A review by Mattle and Hess reported that up to 48% of patients taking alkali citrate left the treatment pre-maturely because of adverse gastrointestinal effects.10 The fact that K-citrate was dissolved in 1.5 L of water in our study and taken throughout the day probably explains the high tolerance.

Limitations

This is retrospective, observational study performed in a single center, with all the limitations inherent to this type of study. Nevertheless, it shows that using a K-citrate protocol with close patient monitoring (with self-assessed pH measurement and a six-month low-does CT scan) is a good option in the treatment of UA stones.

CONCLUSIONS

Our data suggest that treatment using K-citrate is very efficient both for dissolution of calculi and for prevention of new stones; however, several conditions must be filled. The first is to be sure that the calculus is made of UA, usually confirmed by infrared analysis of a former stone or by a UA crystalluria with an acidic pH, and a low stone density confirmed by CT scan. The second is patient compliance with the protocol (i.e., the need to drink K-citrate diluted in 1.5 L of water throughout the day to avoid gastroenterological problems). The third is patient self-assessment of urine pH several times a day with a pH meter, and communication with the medical team. With these conditions met, using a K-citrate protocol is a feasible option in the treatment of UA stones.

Footnotes

COMPETING INTERESTS: The authors do not report any competing personal or financial interests related to this work.

This paper has been peer reviewed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Daudon M. Épidémiologie actuelle de la lithiase rénale en France. Ann Urol. 2005;39:209–31. doi: 10.1016/j.anuro.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sakhaee K, Maalouf NM. Kidney stones 2012: Pathogenesis, diagnosis and management. J Clin Endocrin Metab. 2012;97:1847–60. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-3492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daudon M, Jungers P, Bazin D, et al. Recurrence rates of urinary calculi according to stone composition and morphology. Urolithiasis. 2018;46:459–70. doi: 10.1007/s00240-018-1043-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Straub M, Hautmann RE. Developments in stone prevention. Curr Opin Urol. 2005;15:119–26. doi: 10.1097/01.mou.0000160627.36236.6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trinchieri A, Esposito N, Castelnuovo C. Dissolution of radiolucent renal stones by oral alkalinization with potassium citrate/potassium bicarbonate. Arch Ital Androl. 2009;81:188–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pearle MS, Goldfarb DS, Assimos DG, et al. Medical management of kidney stones: AUA guideline. J Urol. 2014;192:316–24. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heilberg I. Treatment of patients with uric acid stones. Urolithiasis. 2016;44:57–63. doi: 10.1007/s00240-015-0843-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sakhaee K, Nicar M, Hill K, et al. Contrasting effects of potassium citrate and sodium citrate therapies on urinary chemistries and crystallization of stone-forming salts. Kidney Int. 1983;24:348–52. doi: 10.1038/ki.1983.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chugtai MN, Khan FA, Kaleem M, et al. Management of uric acid stone. J Pak Med Assoc. 1992;42:153–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mattle D, Hess B. Preventive treatment of nephrolithiasis with alkali citrate – a critical review. Urolithiasis. 2005;33:73–9. doi: 10.1007/s00240-005-0464-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsaturyan A, Bokova E, Bosshard P, et al. Oral chemolysis is an effective, non-invasive therapy for urinary stones suspected of uric acid content. Urolithiasis. 2020;48:501–7. doi: 10.1007/s00240-020-01204-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daudon M, Bader CA, Jungers P. Urinary calculi: Review and classification methods and correlations with etiology. Scanning Microsc. 1993;7:1081–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daudon M, Frochot V, Bazin D, et al. Crystalluria analysis improves significantly etiologic diagnosis and therapeutic monitoring of nephrolithiasis. Comptes Rendus Chimie. 2016;19:1514–26. doi: 10.1016/j.crci.2016.04.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sakhaee K, Adams-Huet B, Moe OW, et al. Pathophysiologic basis for normouricosuric uric acid nephrolithiasis. Kidney Int. 2002;62:971–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00508.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lemoine S, Dahan P, Haymann JP, et al. Lithiasis Committee of the French Association of Urology (CLAFU) 2022 Recommendations of the AFU Lithiasis Committee: Medical management – from diagnosis to treatment. Prog Urol. 2023;33:911–53. doi: 10.1016/j.purol.2023.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pak CY, Sakhaee K, Moe O, et al. Biochemical profile of stone-forming patients with diabetes mellitus. Urology. 2003;61:523–7. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(02)02421-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Daudon M, Traxer O, Conort P, et al. Type 2 diabetes increases the risk for uric acid stones. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:20–6. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006030262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sakhaee K. Epidemiology and clinical pathophysiology of uric acid kidney stones. J Nephrol. 2014;27:241–5. doi: 10.1007/s40620-013-0034-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maalouf NM, Cameron MA, Moe OW, et al. Novel insights into the pathogenesis of uric acid nephrolithiasis. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2004;13:181–9. doi: 10.1097/00041552-200403000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Daudon M, Lacour B, Jungers P. Influence of body size on urinary stone composition in men and women. Urol Res. 2006;34:193–9. doi: 10.1007/s00240-006-0042-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cameron MA, Baker LA, Maalouf NM, et al. Circadian variation in urine pH and uric acid nephrolithiasis risk. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22:2375–8. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cameron M, Maalouf NM, Poindexter J, et al. The diurnal variation in urine acidification differs between normal individuals and uric acid stone formers. Kidney Int. 2012;81:1123–30. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kenny JE, Goldfarb DS. Update on the pathophysiology and management of uric acid renal stones. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2010;12:125–9. doi: 10.1007/s11926-010-0089-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sinha M, Prabhu K, Venkatesh P, et al. Results of urinary dissolution therapy for radiolucent calculi. Int Braz J Urol. 2013;39:103–7. doi: 10.1590/S1677-5538.IBJU.2013.01.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gridley CM, Sourial MW, Lehman A, et al. Medical dissolution therapy for the treatment of uric acid nephrolithiasis. World J Urol. 2019;37:2509–15. doi: 10.1007/s00345-019-02688-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salem SM, Sultan MF, Badawy A. Oral dissolution therapy for renal radiolucent stones, outcome, and factors affecting response: A prospective study. Urol Ann. 2019;11:369–73. doi: 10.4103/UA.UA_20_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elsawy AA, Elshal AM, El-Nahas AR, et al. Can we predict the outcome of oral dissolution therapy for radiolucent renal calculi? A prospective study. J Urol. 2019;201:350–7. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2018.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moore J, Nevo A, Salih S, et al. Outcomes and rates of dissolution therapy for uric acid stones. J Nephrol. 2022;35:665–9. doi: 10.1007/s40620-021-01094-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Frolova EA, Tsarichenko DG, Saenko VS, et al. Dissolution of uric acid stones in the ureter. Urologiia. 2022;6:56–60. doi: 10.18565/urology.2022.6.56-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ong A, Brown G, Tokas T, et al. selection and outcomes for dissolution therapy in uric acid stones: A systematic review of literature. Review Curr Urol Rep. 2023;24:355–63. doi: 10.1007/s11934-023-01164-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nevo A, Humphreys MR, Callegari M, et al. Is medical dissolution treatment for uric acid stones more cost-effective than surgical treatment? A novel, solo practice, retrospective cost-analysis of medical vs. surgical therapy. Can Urol Assoc J. 2023;17:E29–34. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.7833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robinson MR, Leitao VA, Haleblian GE, et al. Impact of long-term potassium citrate therapy on urinary profiles and recurrent stone formation. J Urol. 2009;181:1145–50. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Straub M, Hautmann RE. Developments in stone prevention. Curr Opin Urol. 2005;15:119–26. doi: 10.1097/01.mou.0000160627.36236.6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ettinger B, Pak CY, Citron JT, et al. Potassium-magnesium citrate is an effective prophylaxis against recurrent calcium oxalate nephrolithiasis. J Urol. 1997;158:2069–73. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(01)68155-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]