Abstract

Introduction

Despite the increasing availability of prevention tools like pre‐exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), HIV incidence remains disproportionately high in sub‐Saharan Africa. We examined PrEP awareness, uptake and persistence among participants enrolling into an HIV incidence cohort in Kenya.

Methods

We used cross‐sectional enrolment data from the Multinational Observational Cohort of HIV and other Infections (MOCHI) in Homa Bay and Kericho, Kenya. The cohort recruited individuals aged 14–55 years with a recent history of sexually transmitted infection, transactional sex, condomless sex and/or injection drug use. Participants completed questionnaires on PrEP, demographics and sexual behaviours. We used multivariable robust Poisson regression to estimate adjusted prevalence ratios (aPRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for associations with never hearing of PrEP, never taking PrEP and ever stopping PrEP.

Results

Between 12/2021 and 5/2023, 399 participants attempted the PrEP questionnaire, of whom 316 (79.2%) were female and median age was 22 years (interquartile range 19–24); 316 of 390 participants (81.0%) engaged in sex work or transactional sex. Of 396 participants who responded to the question, 120 (30.3%) had never heard of PrEP. Of 275 participants who had heard of PrEP, 206 (74.9%) had never taken it. Of 69 participants who had ever taken PrEP, 50 (72.5%) stopped it at some time prior to enrolment. Participants aged 15–19 years more often reported never taking PrEP compared with those 25–36 years (aPR 1.31, 95% CI: 1.06–1.61). Participants who knew someone who took PrEP less often reported never hearing about PrEP (aPR 0.10, 95% CI: 0.04–0.23) and never taking PrEP (aPR: 0.69, 95% CI: 0.60–0.80). Stopping PrEP was more common among participants with a weekly household income ≤1000 versus >1000 Kenyan shillings (aPR 1.40, 95% CI: 1.02–1.93) and those using alcohol/drugs before sex (aPR 1.53, 95% CI: 1.03–2.26). Stopping PrEP was less common among those engaging in sex work or transactional sex (aPR 0.6, 95% CI: 0.40–0.92).

Conclusions

We identified substantial gaps in PrEP awareness, uptake and persistence, which were associated with potential system‐ and individual‐level risk factors. Our analyses also highlight the importance of increasing PrEP engagement among individuals who do not know others taking PrEP.

Keywords: pre‐exposure prophylaxis, HIV, tenofovir, Kenya, implementation science, social determinants of health

1. INTRODUCTION

Kenya has about 1.4 million people living with HIV (4% prevalence) and although the incidence is decreasing, 35,000 people newly acquired HIV in 2021 [1]. HIV epidemiology varies geographically, with nine counties primarily in western Kenya accounting for 57% of all new HIV diagnoses in 2021 [2, 3]. Kenya developed an implementation framework for oral tenofovir‐based pre‐exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in 2017 [4] and introduced it into guidelines in 2018 [5]. Despite increased PrEP initiation country‐wide [6], progress has been slower than desired [4] and studies have reported low uptake and high rates of discontinuation in some populations [7, 8, 9, 10]. Better understanding of implementation gaps and who they affect may inform ways to enhance PrEP engagement, particularly among “key” and other vulnerable populations underserved by Kenya's HIV response [11]. We assessed PrEP awareness, use and persistence among individuals vulnerable to HIV acquisition in western Kenya and identified variables associated with gaps in PrEP implementation.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study population

We used enrolment data from the Multinational Observational Cohort of HIV and other Infections (MOCHI; Clinicaltrials.gov NCT05147519), an HIV incidence study in Kericho and Homa Bay, Kenya. Recruitment occurred primarily in bars, entertainment venues, and fish markets [12]. A target sample size of 400 was chosen for 95% confidence of detecting ≥3 cases/100 person‐years (i.e. incidence sufficient to support efficacy testing of HIV prevention interventions) if the true incidence were at least 4.5 cases per 100 person‐years.

Eligible participants were 14–55 years of age, not living with HIV (based on non‐reactive antibody test) and satisfied ≥1 of the following criteria in the previous 24 weeks: (1) documented newly diagnosed bacterial sexually transmitted infection (STI), herpes simplex virus or acute hepatitis C virus; (2) self‐reported sexual intercourse in exchange for money as a regular source of income; (3) self‐reported condomless vaginal or anal intercourse with ≥3 different partners living with HIV or with unknown status; (4) injection drug use; and (5) self‐reported anal/neovaginal intercourse. A positive urine pregnancy test result was exclusionary to mimic the potential participant population in an early‐phase clinical trial.

Informed consent was required for all participants; parent/guardian consent was not required for those aged 15–17 years per local guidelines [13]. The study was approved by institutional review boards at the Kenya Medical Research Institute (#4237) and Walter Reed Army Institute of Research (#2877).

2.2. Data collection and measures

Participants completed questionnaires covering demographics, behaviours and PrEP in English or Kiswahili primarily by computer‐assisted self‐interview at the screening and enrolment visits.

Non‐mutually exclusive key populations were defined as follows: people who engaged in sex work or transactional sex (i.e. identifying current occupation as a sex worker or reported transactional sex in the past 12 weeks); males who have sex with males (MSM; i.e. males with a male partner in the past 12 weeks), transgender people (i.e. gender identity other than the sex assigned at birth) and people who inject drugs (i.e. in the past 12 weeks). Inconsistent/no condom use in the past 12 weeks was ascertained by asking about the percentage of sex acts with a condom in separate questions by partner sex, main or casual partner type, sex type (i.e. anal, vaginal, neovaginal) and insertive or receptive role when applicable.

The PrEP questionnaire included questions about PrEP awareness, use and agreement or disagreement with statements related to concerns about PrEP and interest in PrEP options using a 5‐point Likert scale. We defined three implementation gaps related to PrEP awareness and use: (1) never heard of PrEP; (2) never taken PrEP (among those who had heard of it); and (3) ever stopped PrEP (among those who had ever used it). The latter outcome comprised those who reported ever stopping PrEP and those who reported ever taking PrEP but were not taking it at enrolment.

2.3. Statistical analyses

Descriptive analyses included frequencies and proportions for all variables. We used multivariable Poisson regression with robust standard errors [14] to compute adjusted prevalence ratios (aPRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) to examine associations between each implementation gap and exposure variables. Analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Statistical significance was determined by p<0.05.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Participant characteristics

Between December 2021 and May 2023, 485 individuals were screened for eligibility, 407 were enrolled and 399 who attempted the PrEP questionnaire were included in these analyses. Median age was 22 years (interquartile range [IQR] 19–24) and 316 (79.2%) were female (Table 1). Common occupations included sex worker (260; 65.3%), fisher or fish trader (32; 8.0%) and entertainment/hospitality (32, 8.0%). Most participants could be classified as a key population, with 316 (81.0%) participants who engaged in sex work or transactional sex, 43 (10.9%) MSM, 6 (1.5%) transgender people and 15 (3.8%) participants with injection drug use.

Table 1.

Study population characteristics and factors associated with never hearing of PrEP, never taking PrEP and ever stopping PrEP

| All participants (n = 399) | Never heard of PrEP (n = 396) | Never taken PrEP (n = 275) | Ever stopped PrEP (n = 69) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Column % | n | Row % | aPR | 95% CI | n | Row % | aPR | 95% CI | n | Row % | aPR | 95% CI | |

| Total | 399 | 100% | 120 | 30.3 | – | – | 206 | 74.9 | – | – | 50 | 72.5 | – | – |

| Sex assigned at birth | ||||||||||||||

| Male | 83 | 20.8 | 20 | 24.1 | 1.17 | 0.77, 1.77 | 46 | 73.0 | 1.01 | 0.82, 1.23 | 13 | 76.5 | 0.94 | 0.60, 1.45 |

| Female | 316 | 79.2 | 100 | 31.6 | – | – | 160 | 75.5 | – | – | 37 | 71.2 | – | – |

| Age group a | ||||||||||||||

| 15–19 years | 105 | 26.3 | 37 | 35.2 | 0.95 | 0.52, 1.73 | 61 | 91.0 | 1.31 | 1.06, 1.61 | 6 | 100.0 | 0.96 | 0.56, 1.67 |

| 20–24 years | 213 | 53.4 | 69 | 32.4 | 1.08 | 0.59, 1.97 | 103 | 73.0 | 1.07 | 0.86, 1.34 | 27 | 71.1 | 0.87 | 0.56, 1.36 |

| 25–36 years | 81 | 20.3 | 14 | 17.3 | – | – | 42 | 62.7 | – | – | 17 | 68.0 | – | – |

| Marital or relationship status | ||||||||||||||

| Married or cohabitating | 36 | 9.0 | 3 | 8.3 | – | – | 28 | 84.8 | – | – | 4 | 80.0 | – | – |

| Not married or cohabitating | 362 | 91.0 | 116 | 32 | 2.28 | 0.69, 7.52 | 178 | 73.6 | 0.89 | 0.72, 1.11 | 46 | 71.9 | 0.70 | 0.38, 1.26 |

| Years of education | ||||||||||||||

| <12 | 209 | 52.5 | 73 | 34.9 | 0.98 | 0.73, 1.33 | 104 | 78.2 | 1.04 | 0.91, 1.20 | 20 | 69.0 | 0.81 | 0.53, 1.23 |

| ≥12 | 189 | 47.5 | 46 | 24.3 | – | – | 102 | 71.8 | – | – | 30 | 75.0 | – | – |

| Weekly household income | ||||||||||||||

| ≤1000 KES b | 133 | 33.4 | 48 | 36.1 | 1.22 | 0.93, 1.59 | 64 | 76.2 | 0.99 | 0.84, 1.15 | 18 | 90.0 | 1.40 | 1.02, 1.93 |

| >1000 KESb | 265 | 66.6 | 71 | 26.8 | – | – | 142 | 74.3 | – | – | 32 | 65.3 | – | – |

| Study site location | ||||||||||||||

| Kericho | 181 | 45.4 | 84 | 46.4 | 1.45 | 0.90, 2.34 | 81 | 85.3 | 1.08 | 0.89, 1.31 | 12 | 85.7 | 1.23 | 0.74, 2.05 |

| Homa Bay | 218 | 54.6 | 36 | 16.5 | – | – | 125 | 69.4 | – | – | 38 | 69.1 | – | – |

| Distance from home to study facility | ||||||||||||||

| ≤3 km | 96 | 24.3 | 14 | 14.6 | – | – | 61 | 75.3 | – | – | 15 | 75.0 | – | – |

| >3 km | 299 | 75.7 | 104 | 34.8 | 0.97 | 0.56, 1.70 | 143 | 74.5 | 0.86 | 0.73, 1.02 | 35 | 71.4 | 0.97 | 0.66, 1.42 |

| Engaged in sex work or transactional sex | ||||||||||||||

| 316 c | 81.0 | 103 | 32.6 | 0.95 | 0.55, 1.63 | 154 | 73.7 | 0.89 | 0.72, 1.09 | 37 | 67.3 | 0.60 | 0.40, 0.92 | |

| Males who have sex with males | ||||||||||||||

| 43 d | 10.9 | 12 | 27.9 | j | j | 15 | 48.4 | j | j | 12 | 75.0 | j | j | |

| Transgender identity | ||||||||||||||

| 6 e | 1.5 | 1 | 16.7 | j | j | 3 | 60.0 | j | j | 1 | 50.0 | j | j | |

| Injection drug use | ||||||||||||||

| 15 f | 3.8 | 3 | 20.0 | j | j | 9 | 80.0 | j | j | 3 | 100 | j | j | |

| Partner with HIV or unknown HIV status in the past 12 weeks | ||||||||||||||

| 279 g | 69.9 | 99 | 35.5 | 1.40 | 0.81, 2.41 | 136 | 76.4 | 1.14 | 0.95, 1.36 | 34 | 81.0 | 1.22 | 0.83, 1.79 | |

| Condom use for anal or (neo)vaginal sex in the past 12 weeks | ||||||||||||||

| Inconsistent | 306 | 79.9 | 89 | 29.1 | 0.94 | 0.67, 1.31 | 159 | 74.3 | 0.99 | 0.83, 1.16 | 41 | 74.5 | 0.80 | 0.51, 1.27 |

| Consistent | 77 | 20.1 | 25 | 32.5 | – | – | 39 | 76.5 | – | – | 8 | 66.7 | – | – |

| Alcohol and/or drugs before sex in the past 12 weeks | ||||||||||||||

| 234 | 60.3 | 86 | 36.8 | 1.24 | 0.88, 1.74 | 113 | 76.4 | 1.06 | 0.90, 1.24 | 28 | 80.0 | 1.53 | 1.03, 2.26 | |

| Self‐reported STI in the past 12 weeks | ||||||||||||||

| 44 | 11.5 | 8 | 18.2 | 0.75 | 0.43, 1.32 | 24 | 66.7 | 0.97 | 0.78, 1.20 | 10 | 83.3 | 1.05 | 0.69, 1.60 | |

| More than one course of HIV PEP in a lifetime | ||||||||||||||

| Yes | 33 | 8.9 | 1 | 3 | j | j | 10 | 31.3 | 0.43 | 0.27, 0.68 | 14 | 63.6 | 0.89 | 0.59, 1.34 |

| No, or never heard of PEP | 336 h | 91.1 | 103 | 30.7 | – | – | 188 | 81.7 | – | – | 32 | 76.2 | – | – |

| Knew someone who took PrEP | ||||||||||||||

| 164 | 41.2 | 8 i | 4.9 | 0.10 | 0.04–0.23 | 95 | 61.7 | 0.69 | 0.60, 0.80 | 43 | 72.9 | 0.88 | 0.49, 1.58 | |

Notes: This table shows frequencies and column percentages for all study population characteristics; frequencies and row percentages for all three implementation gaps; and results from fully adjusted regression models for never heard of PrEP (n = 360), never taken PrEP (n = 239) and ever stopped PrEP (n = 60). Results for never heard of PrEP were limited to the 396 participants who answered the question about having heard about PrEP among the 399 participants who attempted the questionnaire. Results for never taken PrEP were limited to the 275 participants who answered the question about taking PrEP among the 276 participants who reported ever having heard about PrEP. Results for ever stopped PrEP included all 69 participants who reported taking PrEP, since they also all answered the question about stopping PrEP. For the regression models, statistically significant results are bolded. Missing data were handled using listwise deletion.

Abbreviations: aPR, adjusted prevalence ratio; CI, confidence interval; KES, Kenyan Shillings; PEP, post‐exposure prophylaxis; PrEP, pre‐exposure prophylaxis; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

Although individuals aged 14–55 years were eligible, only participants aged 15–36 years enrolled.

1000 KES was equivalent to approximately 7 USD at the time of the survey and was the 20th percentile of responses.

n = 260 reported their current occupation as “sex worker.”

Among 43 males who have sex with males, n = 19 also reported engaging in sex work/transactional sex and n = 2 also reported injection drug use.

Among six transgender participants, n = 3 were transgender women and n = 3 were transgender men; n = 2 also reported sex work/transactional sex and n = 2 reported engaging in both sex work/transactional sex and injection drug use.

Among 15 participants with injection drug use, n = 10 also reported engaging in sex work/transactional sex.

n = 12 participants had partners known to be living with HIV.

n = 114 had never heard of PEP; n = 184 had heard of PEP but had never taken it; n = 38 had taken one course of PEP.

Likely represents individuals who recalled knowing someone who took PrEP after being provided with information on PrEP during the survey.

Not included in the multivariable model because of insufficient sample size and/or collinearity.

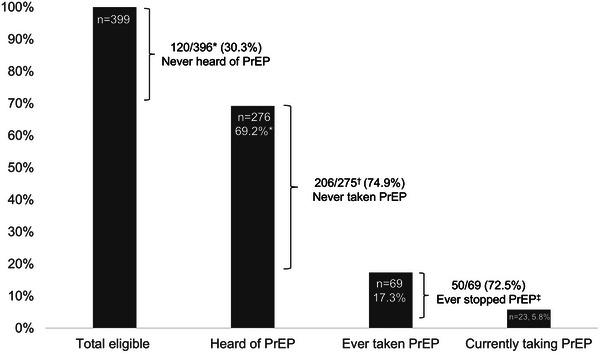

3.2. PrEP awareness and use, and implementation gaps

Of 399 participants, 276 (69.2%) had heard of PrEP, 69 (17.3%) had ever taken PrEP and 23 (5.8%) were currently taking PrEP (Figure 1). Of 396 who answered the question about hearing of PrEP, 120 (30.3%) had never heard of PrEP. Of 275 participants who reported having heard of PrEP, 206 (74.9%) had never taken PrEP. Of 69 participants who had ever taken PrEP, 50 (72.5%) had ever stopped taking it.

Figure 1.

PrEP eligibility, awareness and use among 399 participants vulnerable to HIV acquisition. PrEP, pre‐exposure prophylaxis. *Three participants eligible for PrEP did not respond to the question about hearing of PrEP, so the denominator is 396. †One participant who had heard of PrEP did not respond to the question about ever taking PrEP, so the denominator is 275. ‡Inclusive of participants who reported ever stopping PrEP and participants who reported ever taking PrEP but were not currently taking it. Therefore, the bracket designating having ever stopped PrEP extends beyond the bar for currently taking PrEP. This figure shows the PrEP engagement cascade, starting at the left with the total number eligible for PrEP, the proportion who had heard of PrEP, the proportion who had ever taken PrEP and the proportion who were currently taking PrEP. Between the bar graphs, we show three gaps in PrEP implementation: never hearing of PrEP, never taking PrEP and ever stopping PrEP. PrEP awareness and use among key populations: Among the 316 people who engaged in sex work or transactional sex, 210 (66.5%) had heard of PrEP, 55 (17.4%) had ever taken PrEP and 21 (6.6%) were currently taking PrEP. Among the 43 MSM, 31 (72.1%) had heard of PrEP, 16 (37.2%) had ever taken PrEP and 5 (11.6%) were currently taking PrEP. Among the six transgender people, five (83.3%) heard of PrEP, two (33.3%) had ever taken PrEP and one (16.7%) was currently taking PrEP. Among the 15 people with injection drug use, 12 (80.0%) had heard of PrEP, 3 (20.0%) had ever taken PrEP and 1 (6.7%) was currently taking PrEP.

Among the 23 participants currently taking PrEP, median duration of PrEP use was 6 months (IQR 2–10) and 16 (69.6%) reported 100% adherence in the past week. Most were accessing PrEP at a government clinic (12 [52.2%]) or a community‐based organization (6 [26.1%]) and reported not paying for it (21 [91.3%]). Condom use was reported to be more frequent after using PrEP among 14 (60.9%) participants. One participant reported problems accessing PrEP, related to its availability (e.g. stock outs).

Among the 50 participants who stopped PrEP, eight (17.4%) reported problems accessing PrEP, including problems related to its availability (4 [57.1%]) or being unable to travel to pick it up (3 [42.9%]). The main reasons for stopping PrEP were trusting their partner (11 [22.0%]), unable to access (5 [10.0%]), side effects (5 [10.0%]) and not wanting others to know (4 [8.0%]).

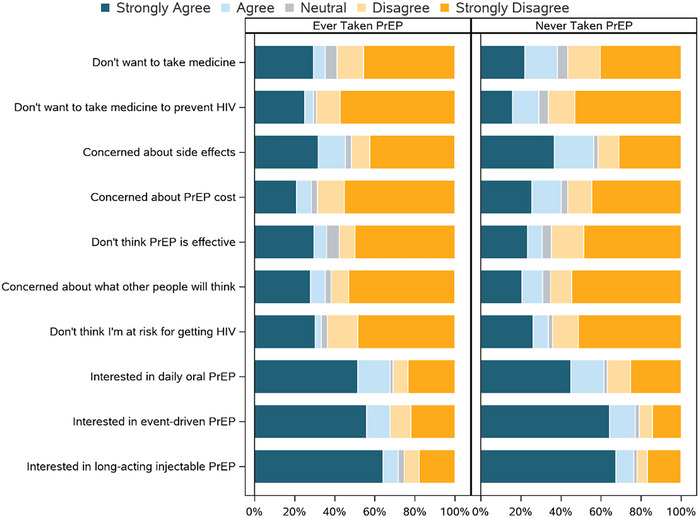

3.3. Concerns about PrEP and interest in PrEP options

The most predominant concern among those who had ever taken PrEP and never taken PrEP was side effects (agree/strongly agree, respectively: 30/66 [45.5%], 163/289 [56.4%]), followed by doubts about PrEP efficacy for those who had ever taken PrEP (agree/strongly agree: 23/64 [35.9%]) and cost for those who had never taken PrEP (agree/strongly agree: 101/251 [40.2%]; Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Concerns about PrEP and interest in PrEP options stratified by ever having ever taken PrEP. PrEP, pre‐exposure prophylaxis. This figure shows responses to agreement/disagreement (based on a 5‐point Likert scale) to statements about concerns about PrEP and interest in PrEP options, stratified by ever taken PrEP (left) and never taken PrEP (right).

Among those who had ever taken PrEP, the strongest interest was for long‐acting injectable PrEP (agree/strongly agree: 48/67 [71.6%]), with the same level of interest for event‐driven PrEP and daily oral PrEP (agree/strongly agree: 46/68 [67.6%], for both options). For those who had never taken PrEP, interest was similarly high for event‐driven PrEP (agree/strongly agree: 235/305 [77.0%]) and long‐acting injectable PrEP (agree/strongly agree: 233/305 [76.4%]), followed by daily oral PrEP (agree/strongly agree: 185/301 [61.5%]).

3.4. Factors associated with never hearing about PrEP, never taking PrEP and ever stopping PrEP

In multivariable models (Table 1), never hearing about PrEP was significantly less common among those who reported knowing someone who took PrEP (aPR 0.10, 95% CI: 0.04–0.23). Never taking PrEP was significantly less common among those who reported having ever taken more than one course of HIV post‐exposure prophylaxis (aPR 0.43, 95% CI: 0.27–0.68) and among those who reported knowing someone who took PrEP (aPR 0.69, 95% CI: 0.6–0.8). Never taking PrEP was significantly more common among participants aged 15–19 years compared with those 25–36 years (aPR 1.31, 95% CI: 1.06–1.61). Ever stopping PrEP was significantly more common among those with a weekly household income ≤1000 versus >1000 Kenyan shillings (aPR 1.40, 95% CI: 1.02–1.93) and those who reported using alcohol and/or drugs before sex versus not (aPR 1.53, 95% CI: 1.03–2.26). Ever stopping PrEP was less common among those who engaged in sex work or transactional sex (aPR 0.60, 95% CI: 0.40–0.92).

4. DISCUSSION

Despite the representation of groups with disproportionately high HIV incidence, PrEP awareness, uptake and persistence were low, corroborating other reports from Kenya and other African countries [7, 8, 9, 10, 15, 16, 17]. Consistent with Kenya's initial tiered rollout of PrEP by county‐level HIV burden [4], we found numerically greater implementation gaps in Kericho versus Homa Bay, which are in low‐ and high‐incidence counties, respectively, but these differences were not statistically significant in multivariable modelling. Kenya's 2022 implementation framework for PrEP included an explicit focus on key populations, in addition to targeting high‐incidence counties [3]. The gaps in PrEP engagement identified among our study population support this additional focus, as key populations are vulnerable to HIV acquisition wherever they reside and should be prioritized for existing and novel HIV prevention tools. Our findings also show the importance of increasing PrEP engagement among the youngest age subgroup (i.e. 15–19 years old) who least often accessed PrEP.

Knowing someone who took PrEP was associated with greater PrEP awareness and uptake, highlighting the need to increase PrEP engagement among people who do not have PrEP users in their social networks. Key populations face pervasive stigma and discrimination in healthcare settings [18, 19, 20], yet some like female sex workers have high levels of social connectivity that could be leveraged for HIV prevention efforts [21]. A modification of the Social‐Ecological Model to HIV prevention emphasizes how both an individual's community and interpersonal networks can influence HIV risk and be incorporated into interventions [22]. Implementation strategies that include peers for referral, navigation and/or delivery of PrEP services have the potential to increase PrEP engagement [23, 24, 25] and are recommended by the World Health Organization [26]. More evidence is needed for specific approaches that could be integrated into existing HIV programming.

Stopping PrEP was common and associated with lower income and alcohol/drug use before sex. In the literature, associations for these variables with PrEP discontinuation have been inconsistent [27, 28]. Programmes that provide PrEP services should target individuals experiencing system‐ and individual‐level risk factors with additional monitoring and resources, as they are at greater risk for adverse PrEP outcomes, such as in PEPFAR's Determined, Resilient, Empowered, AIDS‐Free, Mentored and Safe (DREAMS) partnership [29]. Participants who engaged in sex work or transactional sex less often reported to have stopped PrEP, which might reflect a greater perceived ongoing need for PrEP relative to other groups. Perceived HIV risk has been robustly associated with PrEP persistence [30, 31].

The low uptake of PrEP, high prevalence of stopping PrEP, varying concerns about PrEP and interest in different PrEP options highlight the importance of offering PrEP options that meet people's needs. For some, long‐acting injectable PrEP is preferred over oral [32, 33, 34, 35] and its implementation is anticipated to reduce HIV incidence in African countries [36]. However, PrEP modalities that meet other needs, for example dual pregnancy prevention [37], and novel service delivery models, for example through community pharmacies [38, 39], have the potential to increase PrEP engagement. Side effects were a predominant concern, especially among people who had never taken PrEP before, which highlights the importance of education and addressing tolerability. Out‐of‐pocket costs were also a predominant concern among those who had never taken PrEP before; thus, direct and indirect costs are possible barriers to address.

Regarding limitations, our questionnaire did not ask specifically about event‐driven PrEP use, which was not in local guidelines when the study was designed [5]. Future surveys should evaluate event‐driven PrEP in Kenya and identify ways to optimize its use for eligible populations. Our sampling strategy was non‐probabilistic and thus precluded the generation of representative estimates; however, it allowed for the effective recruitment of populations vulnerable to HIV. Some participants from key populations may have been misclassified because our definitions were based on questions with 12‐week recall. We had few participants who were transgender or who injected drugs, precluding a robust assessment of PrEP engagement in these populations.

5. CONCLUSIONS

We identified substantial gaps in PrEP awareness, uptake and persistence in this cohort of people vulnerable to HIV acquisition in Kenya and these gaps were associated with potential system‐ and individual‐level risk factors. Our analyses also highlight the importance of increasing PrEP engagement among individuals who do not know others taking PrEP.

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

MLR, GS, JK, BG and TAC conceived and designed the analysis with critical input at various stages from CC, PA, EL, DC, MY, JAA and FS. CA, RB and DL collected and managed data. GS and AY conducted the statistical analysis. MLR wrote the first draft of the manuscript. GS, JK, CA, RB, DL, CC, PA, BG, EL, DC, AY, MY, JAA, FS and TAC edited and provided input for the manuscript, and approved the final version.

FUNDING

This work was supported by a cooperative agreement (W81XWH‐18‐2‐0040) between the Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine, Inc., and the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD). This research was funded, in part, by the U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (AAI20052001). The investigators have adhered to the policies for protection of human research participants as prescribed in AR 70–25.

DISCLAIMER

This material has been reviewed by the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research. There is no objection to its presentation and/or publication. The opinions or assertions contained herein are the private views of the author, and are not to be construed as official, or as reflecting true views of the Department of the Army or the Department of Defense.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank the MOCHI participants and the members of the study team for their contributions. MOCHI Study Group: Home office: Trevor Crowell (protocol chair), Julius Tonzel, Roger Ying, Julie Ake, Paul Adjei, Brennan Cebula, Curtisha Charles, Linsey Scheibler, Tsedal, Mebrahtu, Brian Liles, Bryce Boron, Ying Fan, Qun Li, Alexus Reynolds, Glenna Schluck, Natalie Burns, Leigh Anne Eller, Michelle Imbach, Jacob Peterson, Addison Walling and Haoyu Qian; Kenya: Josphat Kosgei (Kenya principal investigator), Rael Bor, Christine Akoth, Charles Kilel, Enock Tonui, Seth Oreyo, Joyce Ondego, Onesmus Kibet, Margaret Biomdo, Viviane Saibala and Fred Sawe.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

REFERENCES

- 1. UNAIDS . UNAIDS Data 2022. 2023. Accessed 18 May 2023. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2023/2022_unaids_data

- 2. National AIDS and STI Control Programme (NASCOP) . Kenya Population‐based HIV Impact Assessment (KENPHIA) 2018: Final Report. Nairobi: NASCOP; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 3. National AIDS & STI Control Programme (NASCOP), Ministry of Health . Framework for the Implementation of Pre‐exposure Prophylaxis of HIV in Kenya. Nairobi, Kenya: NASCOP; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 4. National AIDS & STI Control Programme (NASCOP), Ministry of Health . Framework for the Implementation of Pre‐exposure Prophylaxis of HIV in Kenya. Nairobi, Kenya: NASCOP; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ministry of Health, National AIDS & STI Control Program . Guidelines on Use of Antiretroviral Drugs for Treating and Preventing HIV Infection in Kenya 2018 Edition. Nairobi, Kenya: NASCOP; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 6. AVAC . The Global PrEP Tracker: Kenya. Accessed 23 May 2023. Available from: https://data.prepwatch.org/

- 7. Bien‐Gund CH, Ochwal P, Marcus N, Bair EF, Napierala S, Maman S, et al. Adoption of HIV pre‐exposure prophylaxis among women at high risk of HIV infection in Kenya. PLoS One. 2022;17(9):e0273409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ohiomoba RO, Owuor PM, Orero W, Were I, Sawo F, Ezema A, et al. Pre‐exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) initiation and retention among young Kenyan women. AIDS Behav. 2022;26(7):2376–2386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ogolla M, Nyabiage OL, Musingila P, Gachau S, Odero TMA, Odoyo‐June E, et al. Uptake and continuation of HIV pre‐exposure prophylaxis among women of reproductive age in two health facilities in Kisumu County, Kenya. J Int AIDS Soc. 2023;26(3):e26069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Koss CA, Havlir DV, Ayieko J, Kwarisiima D, Kabami J, Chamie G, et al. HIV incidence after pre‐exposure prophylaxis initiation among women and men at elevated HIV risk: a population‐based study in rural Kenya and Uganda. PLoS Med. 2021;18(2):e1003492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Musyoki H, Bhattacharjee P, Sabin K, Ngoksin E, Wheeler T, Dallabetta G. A decade and beyond: learnings from HIV programming with underserved and marginalized key populations in Kenya. J Int AIDS Soc. 2021;24(Suppl 3):e25729. 10.1002/jia2.25729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. UNICEF . In Homa Bay, teenage girls face high risk of HIV and unintended pregnancy. 2020. Accessed 11 March 2024. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/kenya/stories/homa‐bay‐teenage‐girls‐face‐high‐risk‐hiv‐and‐unintended‐pregnancy

- 13. National AIDS and STI Control Programme (NASCOP) & Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) . Guidelines for Conducting Adolescent HIV Sexual and Reproductive Health Research in Kenya. 2015.

- 14. Zou G. A modified Poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159(7):702–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Were D, Musau A, Mutegi J, Ongwen P, Manguro G, Kamau M, et al. Using a HIV prevention cascade for identifying missed opportunities in PrEP delivery in Kenya: results from a programmatic surveillance study. J Int AIDS Soc. 2020;23(Suppl 3):e25537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. de Dieu Tapsoba J, Zangeneh SZ, Appelmans E, Pasalar S, Mori K, Peng L, et al. Persistence of oral pre‐exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among adolescent girls and young women initiating PrEP for HIV prevention in Kenya. AIDS Care. 2021;33(6):712–720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Heck CJ, Mathur S, Alwang'a H, Daniel OM, Obanda R, Owiti M, et al. Oral PrEP consultations among adolescent girls and young women in Kisumu County, Kenya: insights from the DREAMS Program. AIDS Behav. 2022;26(8):2516–2530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Scorgie F, Nakato D, Harper E, Richter M, Maseko S, Nare P, et al. ‘We are despised in the hospitals’: sex workers' experiences of accessing health care in four African countries. Cult Health Sex. 2013;15(4):450–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shangani S, Naanyu V, Operario D, Genberg B. Stigma and healthcare‐seeking practices of men who have sex with men in western Kenya: a mixed‐methods approach for scale validation. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2018;32(11):477–486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Crowell TA, Keshinro B, Baral SD, Schwartz SR, Stahlman S, Nowak RG, et al. Stigma, access to healthcare, and HIV risks among men who sell sex to men in Nigeria. J Int AIDS Soc. 2017;20(1):21489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Restar AJ, Valente PK, Ogunbajo A, Masvawure TB, Sandfort T, Gichangi P, et al. Solidarity, support and competition among communities of female and male sex workers in Mombasa, Kenya. Cult Health Sex. 2022;24(5):627–641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Baral S, Logie CH, Grosso A, Wirtz AL, Beyrer C. Modified social ecological model: a tool to guide the assessment of the risks and risk contexts of HIV epidemics. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mujugira A, Karungi B, Mugisha J, Nakyanzi A, Bagaya M, Kamusiime B, et al. “I felt special!”: a qualitative study of peer‐delivered HIV self‐tests, STI self‐sampling kits and PrEP for transgender women in Uganda. J Int AIDS Soc. 2023;26(12):e26201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Roberts ST, Mancuso N, Williams K, Nabunya HK, Mposula H, Mugocha C, et al. How a menu of adherence support strategies facilitated high adherence to HIV prevention products among adolescent girls and young women in sub‐Saharan Africa: a mixed methods analysis. J Int AIDS Soc. 2023;26(11):e26189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wairimu N, Malen RC, Reedy AM, Mogere P, Njeru I, Culquichicón C, et al. Peer PrEP referral + HIV self‐test delivery for PrEP initiation among young Kenyan women: study protocol for a hybrid cluster‐randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2023;24(1):705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. World Health Organization . Consolidated guidelines on HIV prevention, testing, treatment, service delivery and monitoring: recommendations for a public health approach. 2021. Accessed 23 May 2023. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240031593 [PubMed]

- 27. Shah P, Spinelli M, Irungu E, Kabuti R, Ngurukiri P, Babu H, et al. Factors associated with usage of oral‐PrEP among female sex workers in Nairobi, Kenya, assessed by self‐report and a point‐of‐care urine tenofovir immunoassay. AIDS Behav. 2024. 10.1007/s10461-024-04455-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Matthews LT, Jaggernath M, Kriel Y, Smith PM, Haberer JE, Baeten JM, et al. Oral preexposure prophylaxis uptake, adherence, and persistence during periconception periods among women in South Africa. AIDS. 2024;38(9):1342–1354. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000003925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. US Department of State . PEPFAR DREAM NextGen Guidance. 2023. Accessed 14 August 2024. Available from: https://www.state.gov/wp‐content/uploads/2024/01/DREAMS‐NextGen‐Guidance‐1.pdf

- 30. Tapsoba JD, Cover J, Obong'o C, Brady M, Cressey TR, Mori K, et al. Continued attendance in a PrEP program despite low adherence and non‐protective drug levels among adolescent girls and young women in Kenya: results from a prospective cohort study. PLoS Med. 2022;19(9):e1004097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pillay D, Stankevitz K, Lanham M, Ridgeway K, Murire M, Briedenhann E, et al. Factors influencing uptake, continuation, and discontinuation of oral PrEP among clients at sex worker and MSM facilities in South Africa. PLoS One. 2020;15(4):e0228620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Little KM, Hanif H, Anderson SM, Clark MR, Gustafson K, Doncel GF. Preferences for long‐acting PrEP products among women and girls: a quantitative survey and discrete choice experiment in Eswatini, Kenya, and South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2024; 28 (3):936‐950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Quaife M, Eakle R, Cabrera Escobar MA, Vickerman P, Kilbourne‐Brook M, Mvundura M, et al. Divergent preferences for HIV prevention: a discrete choice experiment for multipurpose HIV prevention products in South Africa. Med Decis Making. 2018;38(1):120–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lancaster KE, Lungu T, Bula A, Shea JM, Shoben A, Hosseinipour MC, et al. Preferences for pre‐exposure prophylaxis service delivery among female sex workers in Malawi: a discrete choice experiment. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(5):1294–1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Montgomery ET, Browne EN, Atujuna M, Boeri M, Mansfield C, Sindelo S, et al. Long‐acting injection and implant preferences and trade‐offs for HIV prevention among South African male youth. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2021;87(3):928–936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Smith J, Bansi‐Matharu L, Cambiano V, Dimitrov D, Bershteyn A, van de Vijver D, et al. Predicted effects of the introduction of long‐acting injectable cabotegravir pre‐exposure prophylaxis in sub‐Saharan Africa: a modelling study. Lancet HIV. 2023;10(4):e254–e265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Begg L, Brodsky R, Friedland B, Mathur S, Sailer J, Creasy G. Estimating the market size for a dual prevention pill: adding contraception to pre‐exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) to increase uptake. BMJ Sex Reprod Health. 2021;47(3):166–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Vera M, Bukusi E, Achieng P, Aketch H, Araka E, Baeten JM, et al. “Pharmacies are everywhere, and you can get it at any time”: experiences with pharmacy‐based PrEP delivery among adolescent girls and young women in Kisumu, Kenya. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2023;22:23259582231215882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kennedy CE, Yeh PT, Atkins K, Ferguson L, Baggaley R, Narasimhan M. PrEP distribution in pharmacies: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2022;12(2):e054121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.