Abstract

The purpose of this study was to test the protective effect of Withania somnifera (WS) against the harmful effects of mercuric chloride (HgCl2)-induced kidney failure at the histological, biochemical, and immune levels in Wistar rats. The study assessed the biochemical and immunological changes in five groups (n = 6): Group 1 (G1) was the negative control, and the other rats received a single subcutaneous dose of HgCl2 (2.5 mg/kg in 0.5 mL of 0.9% saline solution) and randomly divided into 4 groups. Group 2 (G2) was the positive control and left without treatment. Groups 3, 4, and 5 (G3, G4, and G5) were treated with different doses of WS root powder for 30 days. The HgCl2-positive group showed significant signs of renal toxicity as reflected by increased levels of kidney function parameters (blood urea nitrogen, urea, and creatinine), inflammatory biomarkers, immunological indices (SDF-1, IL-6, NGAL, and KIM-1), and oxidative stress (SOD, TAC, CAT, GSH, and MDA). The positive group rats also showed drastic pathological changes in renal tissues. Different doses of WS treatment significantly reduced the levels of all biochemical markers and decreased pathological damage to the kidney tissues. The antioxidant, phenolic, and flavonoid constituents of WS root powder helped protect rats' kidneys against HgCl2-induced kidney toxicity in male rats.

Keywords: KIM-1, mercuric chloride, oxidative stress, renal toxicity, SDF-1, Withania somnifera

1. Introduction

Mercury, a heavy metal, is one of the oldest dangerous industrial and environmental poisons that cause drastic alterations in human and animal body tissues, including the kidney and other organs, and it is considered hazardous or poisonous at low concentrations [1–3]. The kidney is susceptible to drug toxicity because it receives 20%–25% of the heart's resting cardiac output; so, it is more exposed to drugs in circulation than any other organ system; the kidney is exposed to higher drug concentrations because the tubules concentrate the filtrate, drug transporters can further increase intracellular drug concentrations, and it is susceptible to nephrotoxic injury because tubules require a lot of energy which occurs when mercury salts are taken up and stored in the kidneys [1].

When inorganic mercury binds to intracellular carboxyl, sulfhydryl, and phosphoryl groups, it becomes toxic in the kidneys like how it accumulates in proximal tubule epithelial cells [4]. The result of these interactions is enzymatic inactivation, inhibition of protein synthesis [5], inhibition of cellular multiplication, decrease in uridine and thymidine uptake, DNA fragmentation, and cellular death [6]. Because inorganic mercury alters the number of thiols within cells, it can cause oxidative stress, lipid peroxidation, malfunction in the mitochondria, and modifications to heme metabolism [7]. The toxicity of mercury has been the subject of numerous investigations. One of the most dangerous forms of mercury is mostly used by the liver and eventually accumulates in the kidneys. As a result, it is believed that the kidneys and liver are the organs most affected [8]. Superoxide dismutase and catalase are two examples of free radical rummaging frameworks that are crushed by mercuric chloride (HgCl2) [9], which also raises the levels of responsive species that aggravate the prooxidant-cell reinforcement balance framework and result in an oxidative pressure state [10].

Withania somnifera (WS), commonly referred to as “ashwagandha” or Indian ginseng, is a well-known medicinal herb that has many therapeutic activities in India, particularly in Ayurveda [11, 12]. It is a small, upright evergreen shrub that can reach a height of four to five feet. It has a variety of benefits, including the ability to reverse the effects of heavy metal-induced oxidative stress and to be adaptogenic, anticonvulsant, cytoprotective, anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory, antiarthritic, and antiapoptotic [11–13]. In addition, it has been shown to have a hepatoprotective effect against the toxicity of paracetamol and acetaminophen [11, 14], with the treatment of liver diseases achieved through inhibition of cyclooxygenase-II, TNF-α, interleukin-1-beta (IL-1-β), and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) [15]. Hepatatorenal protection against ND (nandrolone decanoate) toxicity is induced by WS root, and it does so by reversing marker enzymes and biochemical parameters to almost near-normal levels. When WS is administered orally, it protects the kidneys from renal damage caused by gentamicin/cisplatin, bromobenzene, and mitochondrial dysfunction. It also lowers nephrotoxicity and increases levels of liver marker enzymes such as AST, ALT, and ALP as well as kidney markers such as creatinine, uric acid (UA), and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) [16]. Numerous studies have demonstrated that ashwagandha may add about 20% to a person's lifespan when treating cancer, Alzheimer's disease, and other illnesses [17]. WS roots are used in the Middle East and India as in herbal medicine for protecting and ameliorating kidney function [1, 5].

In this study, HgCl2-induced toxicity was investigated and the protective benefits of WS root powder against kidney metal-induced toxicity were assessed based on biochemical and histological criteria.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

Natural WS (ashwagandha) root powder was purchased from Alharraz commercial company, Cairo, Egypt. HgCl2 was supplied by Sigma Chemical Co.

2.2. Animals

Thirty Sprague–Dawley strain adult male albino rats weighing 200 ± 5 g were obtained from the Agricultural Research Center located in Giza, Egypt. The animals were housed in stainless steel cages (6/each) in a room with controlled temperature (23 + 2°C) and humidity (60 + 2%) and were kept on a 12-h light-dark cycle (7 a.m.–7 p.m.). Water and basal diet [18] were available ad libitum during the experiment, and the laboratory animals' nutritional supply fed the animals a basal diet.

2.3. Standard Basal Diet

The basal diet consisted of the following ingredients: casein, corn oil, vitamin mixture, mineral mixture, choline chloride, methionine, cellulose, and corn starch according to AIN-93. While the salt mixture was prepared according to Hegsted et al. [19], the vitamin mixture components employed were prepared according to Campbell [20].

2.4. Experiment Design

This work was performed at Mansoura University, Mansoura, Egypt, according to the ethical guidelines of the University of Mansoura. Ethical approval was granted by the Institutional Research Board (IRB) of Mansoura University Animal Care and Use Community (MU-ACUC), Egypt (Key: SC.MS.22.12.4). The rats were randomly assigned to five groups, six rats each, as follows: G1 (the first group: received only one subcutaneous injection dose of 0.5 mL 0.9% saline solution), and the other remaining rats were rats which received a single subcutaneous dose of HgCl2 (2.5 mg/kg in 0.5 mL 0.9% saline solution) to induce kidney toxicity [21] and were randomly divided into four groups: an untreated positive control group (G2) and three WS-treated groups. The doses of WS in the three groups were chosen to be around what is used in herbal medicine in the Middle East and India in herbal medicine for protecting and ameliorating kidney function as follows: the third group (G3) received a daily dose of 250 mg/kg of WS root powder using gastric gavage for 30 days, the fourth group (G4) received a daily dose of 500 mg/kg of WS roots powder using gastric gavage for 30 days, and the fifth group (G5) received a daily dose of 750 mg/kg of WS roots powder using gastric gavage for 30 days [22]. The 30 days were found enough to induce kidney toxicity and reveal the protective activity of the treating materials [22].

2.5. Euthanasia, Dissection, and Blood Collection

The rats were CO2 euthanized in their cages until narcosis and then translocated. Rats were then dissected; blood samples were collected for biochemical analysis, and kidneys were washed in saline and kept in 10% formalin for histological preparations. The blood samples were frozen at −20°C for analysis after being centrifuged at 2000 g for 10 min at 4°C. The samples were then aliquoted for the appropriate analytical findings.

2.6. Biochemical Analysis

The following biochemical markers were selected carefully to measure kidney functions, renal toxicity, and the protecting activity of WS.

2.7. Kidney Indices

Automated and standardized techniques using a commercial kit (Diamond) from Germany were used to determine serum creatinine. The method used to determine UA was a commercial kit (Diamond). Serum BUN was estimated using a commercial kit (Human). All analyses were done according to the instructions of the suppliers.

2.8. Antioxidants

Serum concentrations of reduced glutathione (GSH), malondialdehyde (MDA), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), total antioxidant capacity (TAC), and superoxide dismutase (SOD) were measured using the procedures outlined by Chance and Mackley [23], DeChatele et al. [24], Beutler et al. [25], Stocks and Dormandy [26], Aebi [27], and Beutler et al. [25], respectively. In addition, a sandwich solid-phase enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was used to measure the levels of stromal-derived factor 1 (SDF-1) ng/mL, interleukin-6 (IL-6) (pg/mL), neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL), and kidney injury molecule-1 (KIM-1) (pg/mL) using commercial kits (Elabsience, RnD system, Bioassay, and Abcam rat kit, respectively).

2.9. Histopathological Preparation

Kidney specimens were obtained, promptly preserved in 10% buffered formalin, dried in an increasing ethanol concentration series (70%, 80%, 90%, and 100%), cleared in xylene, and embedded in paraffin. Hematoxylin and eosin dye were used to generate sections that were 4-5 μm in size [28].

2.10. Statistical Analysis

The Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) 16.0 Program was used to analyze the results of this study. The expression for data from independent experiments is the arithmetic mean ± standard deviation. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and the Student's t-test were used to assess the statistical significance of the mean differences. A significance level of p < 0.05 was used.

3. Results

3.1. Histopathology of the Kidney

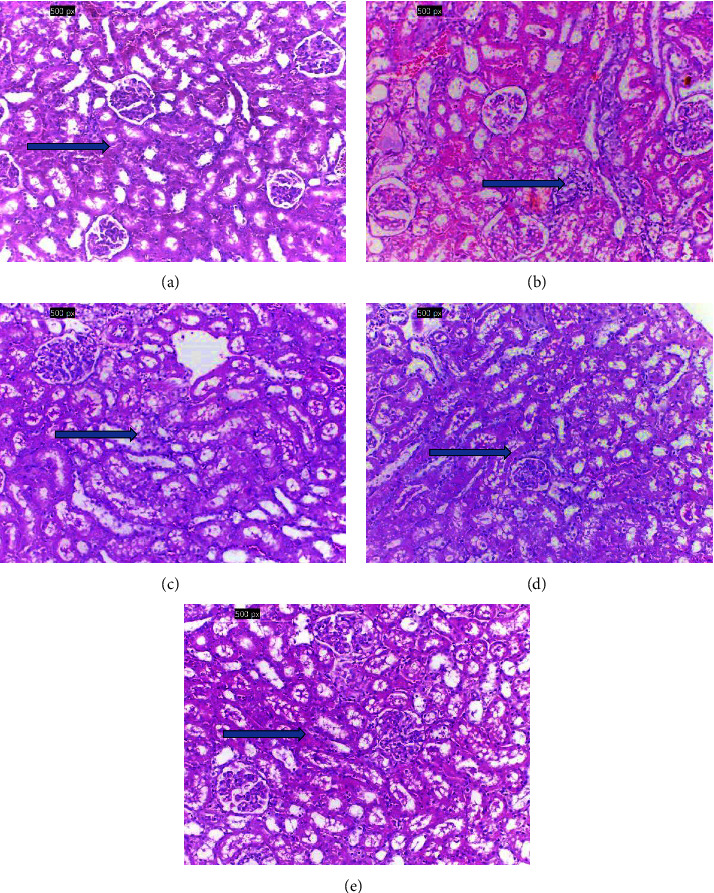

The histological investigations of kidney tissues of various groups are displayed in Figure 1. The control group's renal tissue (G1) showed normal morphological characteristics with normal blood vessels, glomeruli, and interstitial (Figure 1(a)). In contrast, the HgCl2-induced kidney toxicity group (G2) exhibited significant renal alteration such as tubular atrophy and cortical ischemia along with glomerular vascular tuft shrinkage (Figure 1(b)). On the other hand, renal tissue treated groups (G3, G4, and G5) showed significant improvement after treatment with WS roots powder at various doses. Figure 1(c) shows restored and improved renal tissues of G3 with moderate tubular atrophy and mild interstitial inflammation, Figure 1(d) shows normal glomeruli with mild tubular atrophy and scantly interstitial inflammation of G4, and Figure 1(e) shows nearly normal renal tissues with normal cortical tissue and scaled regenerating tubules. The improvement increased with the increase of the treating dose of WS as shown in Figures 1(c), 1(d), and 1(e).

Figure 1.

(a) Normal histological structure of renal parenchyma in G1 with normal renal tissue, blood vessels, and interstitial with no histopathological changes (Arrow), (b) marked cortical ischemia with shrinkage of glomerular vascular tuft and marked tubular atrophy (arrow), (c) improved renal tissues (G3) showing moderate tubular atrophy with mild interstitial inflammation (arrow), (d) showing normal glomeruli (G4) with mild tubular atrophy and scantly interstitial inflammation (arrow), and (e) nearly normal renal tissues showing normal cortical tissue with scaled regenerating tubules (arrow) (X200, H&E).

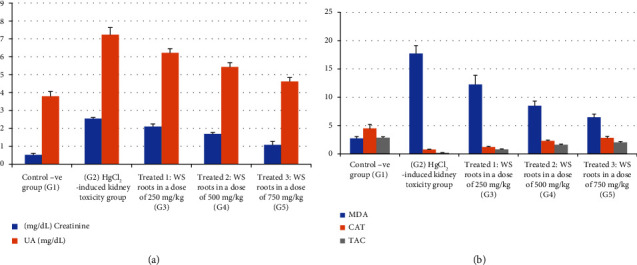

Figure 2(a) and Supporting Table 1 show that the positive control group (G2) had significantly (p < 0.05) higher serum creatinine, UA, and BUN in comparison to the negative control group (G1). In contrast to G2, these kidney function parameters were partially restored in the treated groups (G3, 4, and 5). In G5 (treated with WS roots at a dose of 750 mg/kg), the dose was more effective in lowering the kidney function indices, compared with the other treated groups (G3 and G4).

Figure 2.

Effect of different doses of Withania somnifera on kidney markers, antioxidants, and lipid peroxidation in HgCl2-induced kidney toxicity: (a) creatinine and UA) and (b) MDA, CAT, and TAC.

The antioxidants analyses are shown in Supporting Table 2 and Figure 2(b). The activities of SOD and catalase (CAT), as well as the levels of GSH and TAC, were all dramatically reduced as a result of kidney damage induced by the HgCl2 injection in the positive control group (G2). In contrast to the positive control group (G2), these markers were elevated in the rats treated with WS roots (G3, G4, and G5).

In addition, Supporting Table 2 also shows that exposure to HgCl2 toxicity greatly increased the levels of lipid peroxidation, MDA, and H2O2 compared with the negative control group (G1). On the other hand, WS treatment in G3, G4 and G5 significantly (p < 0.05) decreased MDA and H2O2 levels compared to that of the positive control. There was a substantial decrease in MDA, a measure of oxidative stress, in G5 (p < 0.05) compared with other treated rat groups (groups 3 and 4).

The data presented in Table 1 show that, in comparison with the negative control group (G1), HgCl2 toxicity significantly increased the levels of stromal cell SDF-1, KIM-1, NGAL, and IL-6, whereas treatment with WS roots significantly (p < 0.05) reduced these elevated parameters in the WS-treated groups (G3, G4, and G5) although the levels remained significantly higher (p < 0.05) than those of the negative control group (G1).

Table 1.

Plasma concentrations of stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF-1), kidney injury molecule-1 (KIM-1), neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL), and IL-6 in control and the different treated groups.

| IL-6 pg/mL | NGAL (ng/mL) | KIM-1 (pg/mL) | SDF-1 (ng/mL) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control −ve group (G1) | 36.32 ± 2.72# | 1.02 ± 0.29# | 28.91 ± 3.78# | 2.24 ± 0.629# |

| HgCl2-induced kidney toxicity group (G2) | 78.80 ± 3.23∗ | 7.87 ± 0.40∗ | 115.93 ± 7.79∗ | 6.85 ± 0.42∗ |

| Treated 1: WS roots in a dose of 250 mg/kg (G3) | 61.45 ± 3.42∗# | 6.50 ± 0.23∗# | 93.82 ± 4.48∗# | 5.56 ± 0.25∗# |

| Treated 2: WS roots in a dose of 500 mg/kg (G4) | 54.95 ± 2.15∗# | 4.88 ± 0.21∗# | 72.98 ± 2.65∗# | 4.21 ± 0.40∗# |

| Treated 3: WS roots in a dose of 750 mg/kg (G5) | 44.78 ± 1.99∗# | 2.54 ± 0.21∗# | 54.13 ± 3.62∗# | 3.49 ± 0.32∗# |

Note: The results are expressed as the M ± SD.

∗Shows a statistically significant difference (p < 0.05). (#) Significant, p < 0.05 as compared with the HgCl2-induced kidney toxicity group (G2). (∗) Significant, p < 0.05 as compared with the control −ve group (G1).

On the other hand, Table 2 shows any potential relationships between the parameters under investigation. The study's findings indicate that there were positive and statistically significant connections between the observed antioxidant levels. On the other hand, oxidative stress indicators (H2O2 and MDA) and measured antioxidants showed substantial negative relationships.

Table 2.

Correlations coefficient (r) values in some measured parameters in all groups.

| Creatinine | Uric acid | BUN | IL-6 | SDF-1 | KIM-1 | NGAL | MDA | H2O2 | GSH | CAT | SOD | TAC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Creatinine | — | 0.962∗ | 0.952∗ | 0.949∗ | 0.955∗ | 0.969∗ | 0.978∗ | 0.948∗ | 0.920∗ | −0.967∗ | −0.943∗ | −0.906∗ | −0.965∗ |

| UA | 0.962∗ | — | 0.943∗ | 0.959∗ | 0.955∗ | 0.975∗ | 0.958∗ | 0.953∗ | 0.931∗ | −0.969∗ | −0.925∗ | −0.890∗ | −0.962∗ |

| BUN | 0.952∗ | 0.943∗ | — | 0.960∗ | 0.947∗ | 0.965∗ | 0.955∗ | 0.972∗ | 0.961∗ | −0.963∗ | −0.906∗ | −0.877∗ | −0.964∗ |

| IL-6 | 0.949∗ | 0.959∗ | 0.960∗ | — | 0.951∗ | 0.962∗ | 0.955∗ | 0.970∗ | 0.960∗ | −0.967∗ | −0.895∗ | −0.876∗ | −0.957∗ |

| SDF-1 | 0.955∗ | 0.955∗ | 0.947∗ | 0.951∗ | — | 0.962∗ | 0.945∗ | 0.958∗ | 0.925∗ | −0.959∗ | −0.931∗ | −0.904∗ | −0.952∗ |

| KIM-1 | 0.969∗ | 0.975∗ | 0.965∗ | 0.962∗ | 0.962∗ | — | 0.974∗ | 0.962∗ | 0.943∗ | −0.977∗ | −0.940∗ | −0.905∗ | −0.976∗ |

| NGAL | 0.978∗ | 0.958∗ | 0.955∗ | 0.955∗ | 0.945∗ | 0.974∗ | — | 0.949∗ | 0.933∗ | −0.984∗ | −0.933∗ | −0.903∗ | −0.975∗ |

| MDA | 0.948∗ | 0.953∗ | 0.972∗ | 0.970∗ | 0.958∗ | 0.962∗ | 0.949∗ | — | 0.956∗ | −0.960∗ | −0.910∗ | −0.880∗ | −0.966∗ |

| H2O2 | 0.920∗ | 0.931∗ | 0.961∗ | 0.960∗ | 0.925∗ | 0.943∗ | 0.933∗ | 0.956∗ | — | −0.945∗ | −0.870∗ | −0.876∗ | −0.943∗ |

| GSH | −0.967∗ | −0.969∗ | −0.963∗ | −0.967∗ | −0.959∗ | −0.977∗ | −0.984∗ | −0.960∗ | −0.945∗ | — | 0.935∗ | 0.918∗ | 0.979∗ |

| CAT | −0.943∗ | −0.925∗ | −0.906∗ | −0.895∗ | −0.931∗ | −0.940∗ | −0.933∗ | −0.910∗ | −0.870∗ | 0.935∗ | — | 0.868∗ | 0.955∗ |

| SOD | −0.906∗ | −0.890∗ | −0.877∗ | −0.876∗ | −0.904∗ | −0.905∗ | −0.903∗ | −0.880∗ | −0.876∗ | 0.918∗ | 0.868∗ | — | 0.889 |

| TAC | −0.965∗ | −0.962∗ | −0.964∗ | −0.957∗ | −0.952∗ | −0.976∗ | −0.975∗ | −0.966∗ | −0.943∗ | 0.979∗ | 0.955∗ | 0.889∗ | — |

(∗) Significant, p > 0.05 in each correlations.

Table 2 shows a positive correlation found between BUN, Il-6, creatinine, and UA. Furthermore, a strong positive correlation was found between the levels of kidney function indices (BUN, UA, and creatinine) and SDF-1 KIM-1, NGAL, and Il-6. Remarkably, Table 2 also shows a strong negative correlation between the measured antioxidants and (NGAL, IL-6, SDF-1, and KIM-1).

4. Discussion

The results of this study revealed the toxicity of the male rat's kidney as a result of HgCl2 exposure which emphasized that the kidney is sensitive to mercury chloride exposure, which has been identified as a renal toxin [9, 29, 30]. This toxicity occurs because mercury compounds are accumulated in the rats' kidneys [6]. The renal damage was proved by the elevated levels of renal biomarkers, inflammatory markers, immunoglobulin markers, and the drastic renal tissue damage in the kidneys during HgCl2-induced kidney toxicity (G2) [6]. The findings of our investigation align with previous publications that indicate a noteworthy rise in BUN, creatinine, and UA levels after exposure to HgCl2 [6, 21, 31].

The improvement of renal function indices after treatment with WS root powder is corroborated by earlier research showing that WS roots provided a considerable but partial shield against tubular cell injury and avoided the rise in BUN, UA, and creatinine levels seen in rats given HgCl2 in the positive control group [11–14, 31]. The degree of these metabolic profile changes was observed when WS root powder was increased. These results might point to WS root powders' protective mechanism against kidney damage in rats exposed to heavy metals. The assessment of kidney (creatinine, UA, and BUN) indices after WS root powder treatment indicates that WS can reverse the kidney tissue damage produced by HgCl2 toxicity; these results are suggestive of the renal protection provided by WS root against nephrotoxicity [31]. The current results emphasized the antioxidant and protective effect of WS powder against HgCl2-induced nephrotoxicity as revealed by the improved biochemical analyses is supported by previous investigations [11–13].

The current study's histopathology results showed significant changes to the kidney's architecture caused by HgCl2-induced nephrotoxicity [31]. The histopathological evaluation unequivocally shows that the cellular damages in the HgCl2-induced nephrotoxicity group, such as necrosis and blood vessel and sinusoidal congestion, may be caused by a reduction in the body's overall antioxidant capacity [6]. In addition, it has been reported that bodybuilders' use of anabolic steroids resulted in a marked increase in the thickness of their renal parenchyma and renal volume, which may indicate kidney dysfunction [32]. Following WS therapy, there was a significant reduction in cellular damages, cytoplasmic alterations, and congestion in all treated groups [11–14].

The current result showed a decrease in antioxidant enzymes (CAT, GSH, and SOD) activity and TAC and an increase in H2O2 and lipid peroxidation as revealed by the increase in MDA. This may occur thanks to strong thiol-binding agents, mercuric ions, and has been shown to raise intracellular ROS levels and cause oxidative stress, which can lead to tissue damage and nephrotoxicity [31, 33]. This metal's toxicity is linked to the production of superoxide radicals and glutathione depletion [34]. Results from previous studies supported the findings of this study, which show that changes in antioxidant enzyme activities in mercury intoxication are caused by reactive oxygen species (O2 or H2O2), which increase lipid peroxidation levels and decrease glutathione levels [35]. Serum SOD, glutathione peroxidase, and catalase activities, as well as reduced glutathione levels, were also decreased as a result of the induced renal toxicity [33–35].

Supplementing with WS roots may help lessen and moderate the progression of renal disorders, which are otherwise markedly accelerated by oxidative stress. It has already been discovered that dietary WS roots guard against renal toxicity brought on by the negative effects of numerous toxic chemicals [31]. Lipid peroxidation was highly inhibited by WS extracts. Antioxidant activities have been linked to several processes, including scavenging radicals, breaking down peroxides, preventing chain initiation, and reducing capacity [32, 33].

The results showed that the groups treated with WS roots powder restored kidney function in the HgCl2-induced toxicity groups. This may suggest a free radical-scavenging mechanism and detoxifying action, which may be connected to the high phenolic and flavonoid contents [11–14]. Anthocyanins, which have been shown to have anti-inflammatory, hydrolytic and oxidative enzyme inhibition, and free radical scavenging capabilities, are the major phenolic compounds in WS [36].

When there are acute or long-term renal injuries, kidney function is typically used to assess the kidney's state by measures such as a detectable drop in urine production, serum level measurements of urea and creatinine, and/or estimation of the BUN to creatinine ratio. There are drawbacks to these tests. For example, even in cases when both kidneys have failed, it takes approximately 24 hours for the creatinine level to increase. Thus, several substitute indicators have been suggested, including SDF-1 [37], KIM-1 [38], and NGAL [39], which are employed as biomarkers of kidney injury and is most substantially upregulated in kidneys injured following ischemia or toxic injury.

The current results are consistent with previous studies that demonstrated nephrotoxicity through increased SDF-1, KIM-1, NGAL, and IL-6 by HgCl2 [40]. Liu's study, which examined the nephrotoxicity effect of mercury chloride in mice, found that the compound significantly elevated serum levels of KIM-1 and NGAL as a result of kidney injury, and that HgCl2 inhibited the expression of renal transporter that elevated levels of SDF-1 and IL-6 as a result of kidney injury through glomerulosclerosis and albuminuria in mice [41].

The root powder of WS, supported by its numerous bioactive components, is effective in protecting against IL-6, which arises from induced kidney toxicity and leads to an increase in the duration of chronic inflammation [42]. Furthermore, data from earlier studies indicated that therapy with WS significantly inhibited nephritis, proteinuria, TNF-α, IL-6, and ROS [43, 44]. These findings are in line with our current investigation, which validates the anti-inflammatory activity of WS by lowering IL-6 and TNF-α.

According to data showing a dramatic increase in the production of SDF-1, KIM-1, NGAL, and IL-6, as well as the fact that this increase was significantly inhibited by WS roots powder in all treated groups, our prior findings indicate that enhanced production of ROS through HgCl2 amplifies the inflammatory reaction and contributes to the subsequent kidney damage. Accordingly, our data support the notion that oxidative stress and inflammatory indicators are positively correlated [43].

The findings of our investigation about the optimal dosage of WS is from 500 mg/kg to 750 mg/kg on HgCl2-induced nephrotoxicity revealed that 750 mg of WS was more effective in shielding the kidney from HgCl2-induced nephrotoxicity; however, the precise mechanism responsible for this protection is not known. We think that the low dose of WS concentration; the 250 mg/kg bw is not enough to scavenge free radicals and stop the inflammatory response caused by mercury chloride exposure. In future studies, it is recommended to compare WS groups with other standard chelating agents used in treating mercury toxicity.

5. Conclusion

The current findings unequivocally show that HgCl2 causes renal toxicity as revealed by the altered biochemical renal markers and the histopathology of the renal tissues, whereas WS has a significant medical benefit and possesses amazing antioxidant characteristics, which may be explained by its ability to scavenge free radicals, boost antioxidant activity when combined with natural antioxidants, and also have immunomodulatory effects. Based on the available research, this plant's powdered root could offer a secure and efficient substitute for traditional medications used in treating renal toxicity disorders.

Nomenclature

- AIN-93

Rodent diet

- ALP

Alkaline phosphatase

- ALT

Alanine aminotransferase

- AST

Aspartate aminotransferase

- BUN

Blood urea nitrogen

- BW

Body weight

- ELISA

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- G1

The first group: received only one subcutaneous injection dose of 0.5 mL 0.9% saline solution

- G2

Received a single subcutaneous dose of HgCl2 (2.5 mg/kg in 0.5 mL 0.9% saline solution) to induce kidney toxicity

- G3

Rats received a single subcutaneous dose of HgCl2 [21] (2.5 mg/kg in 0.5 mL 0.9% saline solution) to induce kidney toxicity and treated with 250 mg/kg of WS roots for 30 days

- G4

Rats received a single subcutaneous dose of HgCl2 [21] (2.5 mg/kg in 0.5 mL 0.9% saline solution) to induce kidney toxicity and were treated with 500 mg/kg of WS roots for 30 days

- G5

Rats received a single subcutaneous dose of HgCl2 [21] (2.5 mg/kg in 0.5 mL 0.9% saline solution) to induce kidney toxicity and were treated with 750 mg/kg of WS roots for 30 days

- GSH

Reduced glutathione

- IL-6

Interleukin-6

- iNOS

Inducible nitric oxide synthase

- KIM-1

Kidney injury molecule

- MDA

Malondialdehyde

- NGAL

Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin

- SDF-1

Stromal cell-derived factor 1

- SOD

Superoxide dismutase

- SPSS

Statistical Package for Social Science

- TAC

Total antioxidant capacity

- WS

Withania somnifera

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The authors did not receive any funds for this study.

Supporting Information

Additional supporting information can be found online in the Supporting Information section.

Supporting Table 1: Plasma concentrations of creatinine, uric acid (UA), and BUN in control and the different treated groups.

Supporting Table 2: Concentrations of oxidative stress parameters and antioxidant biomarkers in control and the different treated groups.

References

- 1.Yu M.-H., Tsunoda H., Tsunoda M. Environmental Toxicology: Biological and Health Effects of Pollutants . Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shetty S. S., Deepthi D., Harshitha S., et al. Environmental Pollutants and Their Effects on Human Health. Heliyon . 2023;9(9):p. e19496. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e19496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clarkson T. W., Magos L., Myers G. J. The Toxicology of Mercury--Current Exposures and Clinical Manifestations. New England Journal of Medicine . 2003;349(18):1731–1737. doi: 10.1056/nejmra022471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mowry J. B. Forty Years of National Poison Data System Annual Reports. Clinical Toxicology . 2023;61(10):713–716. doi: 10.1080/15563650.2023.2286200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu Y. S., Osman A. I., Hosny M., et al. The Toxicity of Mercury and its Chemical Compounds: Molecular Mechanisms and Environmental and Human Health Implications: A Comprehensive Review. ACS Omega . 2024;9(5):5100–5126. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.3c07047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bridges C. C., Zalups R. K. Mechanisms Involved in the Transport of Mercuric Ions in Target Tissues. Archives of Toxicology . 2017;91(1):63–81. doi: 10.1007/s00204-016-1803-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Orr S. E., Bridges C. C. Chronic Kidney Disease and Exposure to Nephrotoxic Metals. International Journal of Molecular Sciences . 2017;18(5):p. 1039. doi: 10.3390/ijms18051039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bridges C. C., Zalups R. K., Joshee L. Toxicological Significance of Renal Bcrp: Another Potential Transporter in the Elimination of Mercuric Ions from Proximal Tubular Cells. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology . 2015;285(2):110–117. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2015.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mahboob M., Shireen K. F., Atkinson A., Khan A. T. Lipid Peroxidation and Antioxidant Enzyme Activity in Different Organs of Mice Exposed to Low Level of Mercury. Journal of Environmental Science and Health, Part B . 2001;36(5):687–697. doi: 10.1081/pfc-100106195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agarwal R., Goel S., Chandra R., Behari J. Role of Vitamin E in Preventing Acute Mercury Toxicity in Rat. Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology . 2010;29(1):70–78. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sivanesan S., Vasavan S., Jagadesan V., Rajagopalan V. Protective Effect of Withania Somniferaon Nandrolone Decanoate-Induced Biochemical Alterations and Hepatorenal Toxicity in Wistar Rats. Pharmacognosy Magazine . 2020;16(68):218–223. doi: 10.4103/pm.pm_349_19. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bharavi K., Reddy A. G., Rao G. S., Reddy A. R., Rao S. V. Reversal of Cadmium-Induced Oxidative Stress in Chicken by Herbal Adaptogens Withania Somnifera and Ocimum Sanctum. Toxicology International . 2010;17(2):59–63. doi: 10.4103/0971-6580.72671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shahriar M., Hossain M., Sharmin F., Akhter S., Haque A., Bhuiyan M. In Vitro Antioxidant and Free Radical Scavenging Activity of Withania Somnifera Root. IOSR Journal of Pharmacy . 2013;3(2):38–47. doi: 10.9790/3013-32203847. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sabina E. P., Rasool M., Vedi M., et al. Hepatoprotective and Antioxidant Potential of Withania Somnifera against Paracetamol-Induced Liver Damage in Rats. Academic Sciences . 2013;5(2):648–651. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Devkar S. T., Kandhare A. D., Zanwar A. A., et al. Hepatoprotective Effect of Withanolide-Rich Fraction in Acetaminophen-Intoxicated Rat: Decisive Role of TNF-α, IL-1β, COX-II and iNOS. Pharmaceutical Biology . 2016;54(11):2394–2403. doi: 10.3109/13880209.2016.1157193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soares M., Abreu I., Assenço F., Borges M. Decanoato de nandrolona aumenta a parede ventricular esquerda, mas atenua o aumento da cavidade provocado pelo treinamento de natação em ratos. Revista Brasileira de Medicina do Esporte . 2011;17(6):420–424. doi: 10.1590/s1517-86922011000600011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumar R., Gupta K., Saharia K., Pradhan D., Subramaniam J. R. Withania Somnifera Root Extract Extends Lifespan of Caenorhabditis elegans. Annals of Neurosciences . 2013;20(1):13–16. doi: 10.5214/ans.0972.7531.200106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Council N. R. Nutrient Requirements of Laboratory Animals . Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 1995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hegsted D., Mills R., Perkins E. Salt Mixture. Journal of Biological Chemistry . 1941;138:p. 459. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Campbell. Dietary Protein Quality Evaluation in Human Nutrition. Report of an FAQ Expert Consultation. FAO Food & Nutrition Paper . 2013;92:1–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Durante P., Romero F., Perez M., Chavez M., Parra G. Effect of Uric Acid on Nephrotoxicity Induced by Mercuric Chloride in Rats. Toxicology and Industrial Health . 2010;26(3):163–174. doi: 10.1177/0748233710362377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jeyanthi T., Subramanian P. Nephroprotective Effect of Withania Somnifera: A Dose- Dependent Study. Renal Failure . 2009;31(9):814–821. doi: 10.3109/08860220903150320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chance B., Mackley A. Assays of Catalase and Peroxides. Methods in Enzymology . 1955;2:764–855. [Google Scholar]

- 24.DeChatelet L. R., McCall C. E., McPhail L. C., Johnston R. B. Superoxide Dismutase Activity in Leukocytes. Journal of Clinical Investigation . 1974;53(4):1197–1201. doi: 10.1172/jci107659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beutler E., Duron O., Kelly B. M. Improved Method for the Determination of Blood Glutathione. The Journal of Laboratory and Clinical Medicine . 1963;61:882–888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stocks J., Dormandy T. L. The Autoxidation of Human Red Cell Lipids Induced by Hydrogen Peroxide. British Journal of Haematology . 1971;20(1):95–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1971.tb00790.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aebi H. Catalase In Vitro. Methods in Enzymology . 1984;105:121–126. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(84)05016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Troiano N. W., Ciovacco W. A., Kacena M. A. The Effects of Fixation and Dehydration on the Histological Quality of Undecalcified Murine Bone Specimens Embedded in Methylmethacrylate. Journal of Histotechnology . 2009;32(1):27–31. doi: 10.1179/014788809794748033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hazelhoff M. H., Bulacio R. P., Torres A. M. Gender Related Differences in Kidney Injury Induced by Mercury. International Journal of Molecular Sciences . 2012;13(8):10523–10536. doi: 10.3390/ijms130810523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ma Y., Shi Y., Zou X., Wu Q., Wang J. Apoptosis Induced by Mercuric Chloride Is Associated with Upregulation of PERK-ATF4-CHOP Pathway in Chicken Embryonic Kidney Cells. Poultry Science . 2020;99(11):5802–5813. doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2020.06.084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaur T., Singh H., Mishra R., et al. Withania Somnifera as a Potential Anxiolytic and Immunomodulatory Agent in Acute Sleep Deprived Female Wistar Rats. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry . 2017;427(1-2):91–101. doi: 10.1007/s11010-016-2900-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bharavi K., Reddy A. G., Rao G. S., Kumar P. R., Kumar D. S., Prasadini P. P. Prevention of Cadmium Bioaccumulation by Herbal Adaptogens. Indian Journal of Pharmacology . 2011;43(1):45–49. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.75669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reus I. S., Bando I., Andrés D., Cascales M. Relationship between Expression of HSP70 and Metallothionein and Oxidative Stress during Mercury Chloride Induced Acute Liver Injury in Rats. Journal of Biochemical and Molecular Toxicology . 2003;17(3):161–168. doi: 10.1002/jbt.10074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Asuku A. O., Ayinla M. T., Ajibare A. J., Olajide T. S. Mercury Chloride Causes Cognitive Impairment, Oxidative Stress and Neuroinflammation in Male Wistar Rats: The Potential Protective Effect of 6-Gingerol-Rich Fraction of Zingiber Officinale via Regulation of Antioxidant Defence System and Reversal of Pro-inflammatory Markers Increase. Brain Research . 2024 March;1826:p. 148741. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2023.148741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Han B., García-Mendoza D., van den Berg H., van den Brink N. W. Modulatory Effects of Mercury (II) Chloride (HgCl 2) on Chicken Macrophage and B‐Lymphocyte Cell Lines with Viral‐Like Challenges In Vitro. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry . 2021;40(10):2813–2824. doi: 10.1002/etc.5169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nielsen I. L., Haren G. R., Magnussen E. L., Dragsted L. O., Rasmussen S. E. Quantification of Anthocyanins in Commercial Black Currant Juices by Simple High-Performance Liquid Chromatography. Investigation of Their pH Stability and Antioxidative Potency. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry . 2003;51(20):5861–5866. doi: 10.1021/jf034004+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hall P., Mitchell E., Smith A., et al. The Future for Diagnostic Tests of Acute Kidney Injury in Critical Care: Evidence Synthesis, Care Pathway Analysis and Research Prioritisation. Health Technology Assessment . 2018;22(32):1–274. doi: 10.3310/hta22320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Waanders F., van Timmeren M. M., Stegeman C. A., Bakker S. J., van Goor H. Kidney Injury Molecule-1 in Renal Disease. The Journal of Pathology . 2010;220(1):7–16. doi: 10.1002/path.2642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Devarajan P. Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin: AÂ Promising Biomarker for Human Acute Kidney Injury. Biomarkers in Medicine . 2010;4(2):265–280. doi: 10.2217/bmm.10.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pollack A. Z., Mumford S. L., Mendola P., et al. Kidney Biomarkers Associated with Blood Lead, Mercury, and Cadmium in Premenopausal Women: a Prospective Cohort Study. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Part A . 2015;78(2):119–131. doi: 10.1080/15287394.2014.944680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sayyed S. G., Hägele H., Kulkarni O. P., et al. Podocytes Produce Homeostatic Chemokine Stromal Cell-Derived factor-1/CXCL12, Which Contributes to Glomerulosclerosis, Podocyte Loss and Albuminuria in a Mouse Model of Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetologia . 2009;52(11):2445–2454. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1493-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sivamani S., Joseph B., Kar B. Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Withania Somnifera Leaf Extract in Stainless Steel Implant Induced Inflammation in Adult Zebrafish. Journal of Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology . 2014;12(1):1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jgeb.2014.01.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Minhas U., Minz R., Bhatnagar A. Prophylactic Effect of Withania Somnifera on Inflammation in a Non-autoimmune Prone Murine Model of Lupus. Drug discoveries & therapeutics . 2011;5(4):195–201. doi: 10.5582/ddt.2011.v5.4.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ku S.-K., Han M.-S., Bae J.-S. Withaferin A Is an Inhibitor of Endothelial Protein C Receptor Shedding In Vitro and In Vivo. Food and Chemical Toxicology . 2014;68:23–29. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2014.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Table 1: Plasma concentrations of creatinine, uric acid (UA), and BUN in control and the different treated groups.

Supporting Table 2: Concentrations of oxidative stress parameters and antioxidant biomarkers in control and the different treated groups.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.