Abstract

This study aimed to examine the association between blood pressure (BP) with health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and emotional states, considering the disease awareness and commitment to treatment among the Iranian adult population. This cross-sectional study uses the data of 7257 and 2449 individuals aged ≥ 20 who had completed data on HRQoL and emotional states, respectively. Linear and logistic regression were used to evaluate the mentioned association. The results showed that commitment to treatment had an inverse association with physical HRQoL in both sexes, except for bodily pain in men. Concerning mental HRQoL, in women, poor medication adherence was linked to a decline in mental HRQoL and social functioning, while good treatment adherence was associated with a reduction in the mental health domain. However, except for a decrease in vitality of hypertensive males with high treatment adherence, no significant association was found between their mental HRQoL and BP. In women, increased commitment to treatment was associated with anxiety, whereas poor commitment was related to depression and stress. The undiagnosed disease was not associated with any HRQoL and emotional state deficits. This study highlights the significance of psychiatric assessment, counseling, and support services while taking into account gender-specific differences among hypertensive patients. It also emphasizes the necessity for customized interventions for both men and women to improve their mental well-being and adherence to treatment.

Keywords: Blood pressure, Health-related quality of life, Emotional states, Disease awareness, Commitment to treatment

Subject terms: Psychology, Cardiology, Health care, Medical research, Risk factors

Introduction

Hypertension, commonly known as high blood pressure (BP), is a leading public health challenge affecting the health and well-being of a large world population. It is responsible for 8.5 million deaths from heart disease, stroke, and end-stage renal disease worldwide1. The global burden and prevalence of hypertension have experienced an increasing trend in the past decade, especially in developing countries2. Two recent studies in Iran showed that hypertension has risen over the past decades and has manifested in about 37% of the adult population2,3. However, the level of awareness of hypertension and efforts to control it are relatively low. A recent report by the World Health Organization revealed that only 42% of affected adults are diagnosed and treated4. Similar to this finding, a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis revealed that more than half of the Iranian adult population were unaware of their disease and were not treated5.

Hypertension is a complex and multifaceted condition with far-reaching consequences for an individual’s health. This underscores the essential need for a multifaceted approach, including lifestyle modifications, medication, and regular monitoring, to address the various physiological, metabolic, and psychological aspects of this complex situation6–8. This condition could be closely aligned with the concept proposed by the Biopsychosocial Model of Health and Disease, which was first introduced by George Engel. This model emphasizes that health and disease are the result of the complex interplay between biological, psychological, and socio-environmental factors, and suggests that the management of a chronic condition like hypertension cannot be fully understood by focusing solely on the biological or physiological aspects, but requires consideration of the social and psychological dimensions such as Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and emotional states as well9.

HRQoL is a multidimensional concept that describes the individual’s perception of their physical, emotional, and social well-being concerning their health status10. HRQoL has increasingly been considered in disease-related studies because it can affect a person’s commitment to treatment, disease severity, and clinical management11,12. On the other hand, while hypertension might not always cause immediate and noticeable symptoms, the health perception of hypertensive patients could be affected significantly based on their differences regarding disease awareness and treatment adherence13–15. In this regard, prior studies in various populations have found that awareness of having high blood pressure was associated with HRQoL in different ways, from inversely14,16 to neutral17 and directly18.

Several studies have demonstrated that individuals with hypertension may undergo significant emotional changes19. Psychological distress, as defined by the American Psychological Association, refers to fluctuations in mood accompanied by distressing physical and mental symptoms, typically characterized by anxiety and depression20. A recent study in Iran reported an escalating prevalence of mental disorders in the general population, with a higher prevalence in women compared to men (27.6 vs. 19.3%)21. The association between hypertension and psychological distress has yielded inconsistent findings, with some indicating a positive association6,22, while others have found no significant association23. Furthermore, certain evidence suggests that individuals with depression or anxiety disorders may exhibit lower blood pressure24. In addition, studies have indicated that the emotional well-being of individuals with high blood pressure may differ based on their adherence to treatment and awareness of their condition25.

Awareness of having high BP and commitment to antihypertensive medications- apart from the well-recognized side effects of drug therapy- are associated with lifestyle changes; hence, it is expected to affect emotional states and different domains and components of HRQoL15,17. Hence, clarifying whether the reported associations are due to the disease process, therapeutic interventions, and/or the consequences of labeling is essential. Most previous studies have primarily focused on investigating the association between self-rated health and emotional distress in individuals who have already been diagnosed with hypertension17. Additionally, the impact of treatment adherence on quality of life and emotional states in the context of hypertension has not been thoroughly examined in population-based surveys conducted in non-western countries like Iran. Furthermore, since perceived self-rated health and emotional states are strongly influenced by sociocultural factors such as cultural norms, beliefs, values, and social support systems26, it is recommended to explore these associations in diverse societies, geographic areas, and across different periods. To the best of our knowledge, none of the previous studies conducted in Iran have examined the association between BP levels, quality of life, and mental health while considering the role of disease awareness and commitment to treatment simultaneously. Therefore, to bridge this knowledge gap, given the controversial findings from previous studies, the high prevalence, and the markedly rising trend of hypertension in Iran, the present study aims to investigate the association between different BP statuses and HRQoL, as well as emotional states while taking into account disease awareness and treatment commitment in a substantial adult population in Iran. By shedding light on the mentioned associations, we hope to gain valuable insights that can inform healthcare strategies, intervention programs, and policy-making aimed at improving the overall health outcomes of individuals affected by hypertension.

Methods

Study design and participants

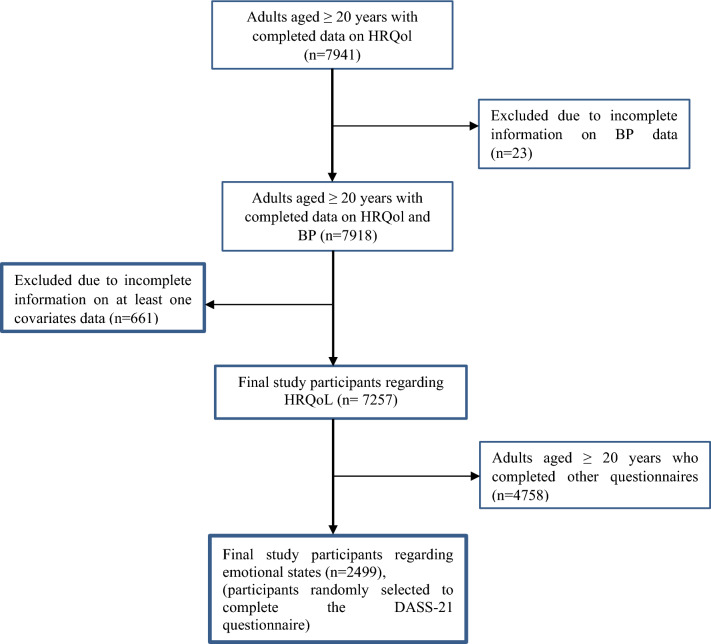

This cross-sectional study was conducted within the Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study (TLGS), a longitudinal population-based study in Tehran, District No. 13, representing the overall Tehranian population. The TLGS employed a cluster random sampling method to select three healthcare centers out of the 20 centers in the district that had field data for over 90% of the covered families. Subsequently, families within these centers were randomly recruited, and all family members were invited to participate in the study. At baseline assessment, 15,005 individuals aged three years and older participated in the TLGS. The TLGS comprises two main periods: the first occurred between February 1999 and August 2001, while the second includes five follow-up phases conducted triennially from 2002 to 201727. For the current study, data from the sixth phase (2014–2017) of the TLGS was utilized, during which several psychosocial variables were added to the TLGS for the first time. Since the participants had already responded to numerous questions assessing their behavioral and clinical characteristics, the study’s planning committee opted to assess psychological concepts through relevant questionnaires administered to more minor, randomly selected groups. However, this decision had an exception in the case of HRQoL, which all participants completed. Consequently, to ensure unbiased results, a double-blind approach was employed to randomly assign participants who completed the HRQoL questionnaire into three groups to fill out other psychological variables, including emotional states. As a result, data on HRQoL was available for 7,941 adult participants, and data on emotional states was only collected for approximately one-third of this subgroup. Based on the previously determined inclusion criteria, the study included participants aged 20 years and older with completed data on HRQoL and covariates including anthropometric measures (weight and height), socio-demographic details (occupation, marital status, and education), behavioral factors (smoking and physical activity), and history of chronic diseases. Thus, before the analysis, data from 23 individuals with incomplete information on blood pressure status, as well as 661 other participants with missing data on covariates were excluded. In this regard, the final analysis included data from 7,257 participants for the HRQoL analysis and 2,499 participants for the emotional state analysis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of participants’ recruitment. HRQoL Health related quality of life, DASS Depression, anxiety, stress.

It is important to note that the study received approval from the Research Institute for Endocrine Sciences (RIES) ethics committee, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants before data collection.

Measurements

Using a pretested socio-demographic questionnaire, trained interviewers collected data on the participants’ age and socio-demographic characteristics, including marital status, education, occupation status, smoking habits, physical activity, and history of chronic disease. Details of the measures have been previously published in the TLGS protocol27,28. Marital status was defined as married and unmarried. Education level was categorized based on the years of education as 1) 0–6 years; 2) 7–12 years; 3) ≥ 13 years. Participants were classified into two groups based on their smoking habits: 1) ever-smokers (daily, occasionally, or ex-smokers) and 2) never-smokers. Chronic disease status was defined as having either of the following conditions: diabetes, chronic kidney disease, history of cancer, and cardiovascular disease. Diabetes was defined as fasting blood glucose ≥ 126 mg/dl or 2-h serum glucose ≥ 200 mg/dl or medical treatment. Chronic kidney disease (CKD) was defined as structural or functional kidney damage or GFR ≤ 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 present for more than three months according to the Kidney Disease Outcome Quality Initiative (K/DOQI) guidelines29. History of cardiovascular disease included coronary heart disease (myocardial infarction, history of heart surgery, angioplasty, and hospitalization in the coronary care unit) and cerebrovascular attack. Physical activity was assessed by the validated Iranian version of the modifiable activity questionnaire (MAQ)30. The total leisure time and work activity were assumed as total physical activity and were expressed in terms of MET-min/wk. Subsequently, participants were categorized into two groups: low/moderate (< 1500) and high (≥ 1500) physical activity. Weight was measured with a digital scale and recorded with an accuracy of 100 g, wearing light clothing without shoes. Height was measured in cm during two positions: 1) the shoulders were standing without shoes, and 2) the shoulders were in a normal position. Finally, body mass index (BMI) was calculated by dividing weight (kg) by square height (m2).

Blood pressure: definition and assessment

Based on the cutoffs recommended for participants ≥ 18 years by the seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of HBP (JNC-VII), hypertension was defined as 1) systolic BP ≥ 140 mmHg or 2) diastolic BP ≥ 90 mmHg or 3) current use of antihypertensive medication31. This study measured the BP following standardized protocols at each TLGS examination phase. After a 15 min rest in the seated position, systolic and diastolic BP was measured twice at a three-minute interval on the right arm by qualified, trained personnel via a standardized mercury sphygmomanometer (calibrated by the Iranian Institute of Standards and Industrial Researches) and the average of two measures was taken as the systolic and diastolic BP. In addition, the study participants were asked about their history of hypertension and medication adherence.

Participants were divided into four categories based on their BP status: (1) normotensive: the reference category- participants who had normal systolic and diastolic BP at the assessment time, had no history of hypertension, and were not taking anti-hypertensive medications; (2) undiagnosed hypertension: subjects with systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mmHg, at the time of assessment, without previous treatment or diagnosis, (3) diagnosed, committed to treatment: patients with known hypertension who had declared that they take anti-hypertensive drugs regularly, (4) diagnosed, non-committed to treatment: patients with known hypertension, who had reported low adherence to anti-hypertensive medications such as never taking medications or taking irregularly. The abovementioned categories were created to differentiate the contribution of awareness and commitment to treatment in the relation between BP with HRQoL and emotional states. Hence, undiagnosed versus diagnosed categories were created to assess the contribution of awareness, and two other categories, including committed versus non-committed to medications, were designed to evaluate the effect of treatment adherence.

Emotional states: depression, anxiety, and stress

To assess the emotional states, we used the Persian version of the depression, anxiety, and stress scale (DASS-21), the short form of the depression, anxiety, and stress scale (DASS). Previous studies have approved this version’s validity and reliability32. In our study, the internal consistency of the DASS-21 was 0.77 for depression, 0.71 for anxiety, and 0.79 for stress, based on the current dataset. This self-reported questionnaire examines how much the respondent has experienced the emotional states of depression, anxiety, and stress over the past week and includes three subscales with seven items per subscale. Items are based on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 (did not apply to me at all) to 4 (applied to me very often or most of the time). The total score of each subscale is obtained from the sum of all related item scores and then multiplied by 2. The normal range for depression, anxiety, and stress is 0–9, 0–7, and 0–14, respectively. Higher scores indicate a greater frequency of these negative emotional states; scores outside this range are considered abnormal.

Health-related quality of life

HRQoL was assessed using a reliable and validated Persian version of the short-form 12-item health survey version 2 (SF-12v2)33. This scale has two physical and mental dimensions, each with four subscales. Physical subscales include physical functioning, role physical, bodily pain, and general health. Mental subscales include vitality, social functioning, role emotional, and mental health. In SF-12v2, each subscale score ranges from 0 as the worst to 100 as the best health condition. Two physical component summary (PCS) and mental component summary (MCS) represent the weighted summary scores of each domain. The reliability of the SF-12v2 questionnaire based on the current data set regarding physical and mental components of HRQoL was 0.75 and 0.78.

Statistical analysis

We used mean ± sd, frequency, and percentages to express normal continuous and categorical variables. We utilized the independent samples T-test, the ANOVA, and the Chi-square test, as appropriate, to compare the distribution of variables among groups. The association of BP status with the HRQoL and DASS scores was assessed using the linear regression model, separately for males and females. We estimated the models’ regression coefficients (β) and 95% confidence intervals. β represents the difference in the mean value of the HRQoL and DASS scores for each BP group compared to the normotensive group. In the current study, variables previously identified as associated with HRQoL and DASS were considered for adjustment34,35. The available variables—age, BMI, chronic disease, occupation, education, marital status, smoking, and physical activity—showed significant differences between the study groups and were selected as the final adjustments. In the current study, there was some missing data on covariates (n = 661); 0.05% (for education and occupation) and 6.1% (for chronic diseases) were the minimum and maximum percent of missing data as a sensitivity analysis; we used multiple imputations to impute missing data. After imputing ten datasets using the chained equations method (wholly conditional specification)36, we estimated the regression coefficients, confidence intervals, and p-values and presented the results in a supplementary file. Statistical analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics version 22 and mi impute command for imputation using Stata (version 14) (Stata Corp LP, College Station, TX USA). A 2-sided P-value < 0.05 was deemed statistically significant.

Ethics declarations

This study was approved by the research ethics committee of the Research Institute for Endocrine Sciences (RIES), Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, with the ethics code number IR.SBMU.ENDOCRINE.REC.1402.026. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. All procedures were under the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Results

A total of 7257 adults (45.6% male) were recruited with a mean age of 47.01 ± 15.72 and 46.76 ± 14.29 years for men and women. The BMI of females was higher than males (28.52 ± 5.31 vs 27.43 ± 4.38). Most participants were married (78.7% of males and 75.3% of females). 14.2% had the lowest education level (0–6 years). Men were most employed compared to females (73.5% vs. 18.9%). Most smokers were men (42.0% of males and 5.3% of females). The prevalence of low/moderate or high physical activity was the same for both sexes. 54% of women and 40% of men were diagnosed with either of the chronic diseases. Regarding BP status, most participants were normotensive (78.3% of females and 75.7% of males). Hypertension was more common in women (17.0 vs. 14.7%), the men had less commitment to treatment (2.8 vs. 1.6%), and the prevalence of undiagnosed hypertension was higher in men (9.6 vs. 4.8%). Full details of the participants’ characteristics in the total population are presented in Supplementary Table 1.

Participants’ characteristics and HRQoL according to their BP status

The characteristics of participants and HRQoL across different BP groups are presented in Table 1, focusing on sex-specific differences. Several socio-demographic and behavioral characteristics and the prevalence of chronic diseases differed significantly among the BP groups, except for physical activity in men and marital status in women. Normotensive participants had a significantly lower mean age, BMI, and chronic disease prevalence than the other studied groups. They were also more likely to have higher levels of education and employment. Regarding smoking, males in the undiagnosed disease category and females with diagnosed hypertension who regularly took their medications were likelier than never to be smokers. Regarding physical HRQoL, the mean scores of the PCS and its subscales significantly differed among the BP groups for both sexes, except for bodily pain in men. Normotensive participants reported the highest scores, while hypertensive patients with good medication adherence reported the lowest. Regarding mental HRQoL, the mean scores of the MCS and two dimensions (vitality and role emotional) significantly differed across BP groups in males. Normotensive participants had the lowest scores, while individuals in the disease-unawareness group had the highest scores. In women, three domains of MCS, including vitality, social functioning, and mental health, showed significant differences among the various BP groups. Normotensive females reported the highest scores, while hypertensive patients with medication non-adherence had the lowest scores.

Table 1.

Participants’ characteristics and HRQoL across different blood pressure groups and sex.

| Male (n = 3315) | Female (n = 3942) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normotensive (n = 2510) | Diagnosed Hypertensive | Undiagnosed hypertension (n = 318) | P-value | Normotensive (n = 3085) | Diagnosed Hypertensive | Undiagnosed hypertension (n = 189) | P-value | |||

| Commitment to treatment (n = 395) | Non-commitment to treatment (n = 92) | Commitment to treatment (n = 606) | Non-commitment to treatment (n = 62) | |||||||

| Age (years) | 43.67 ± 14.74 | 63.51 ± 11.29 | 53.79 ± 14.14 | 50.95 ± 14.10 | < 0.001 | 43.09 ± 12.84 | 62.22 ± 9.08 | 55.66 ± 10.71 | 54.24 ± 12.23 | < 0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.95 ± 4.22 | 28.33 ± 4.25 | 29.47 ± 4.32 | 29.53 ± 4.84 | < 0.001 | 27.70 ± 5.07 | 31.59 ± 5.07 | 31.47 ± 4.67 | 31.10 ± 5.30 | < 0.001 |

| Marital status | < 0.001 | 0.553 | ||||||||

| Unmarried | 641 (25.5) | 17 (4.3) | 8 (8.7) | 41 (12.9) | 768 (24.9) | 154 (25.4) | 12 (19.4) | 41 (21.7) | ||

| Married | 1869 (74.5) | 378 (95.7) | 84 (91.3) | 277 (87.1) | 2317 (75.1) | 452 (74.6) | 50 (80.6) | 148 (78.3) | ||

| Education (years) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| 0–6 | 191 (7.6) | 90 (22.8) | 18 (19.6) | 38 (11.9) | 324 (10.5) | 298 (49.2) | 22 (35.5) | 53 (28) | ||

| 7–12 | 1298 (51.7) | 205 (51.9) | 45 (48.9) | 174 (54.7) | 1587 (51.4) | 268 (44.2) | 33 (53.2) | 102 (54) | ||

| ≥ 13 | 1021 (40.7) | 100 (25.3) | 29 (31.5) | 106 (33.3) | 1174 (38.1) | 40 (6.6) | 7 (11.3) | 34 (18) | ||

| Occupation status | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| Employed | 1953 (77.8) | 182 (46.1) | 65 (70.7) | 235 (73.9) | 702 (22.8) | 20 (3.3) | 7 (11.3) | 18 (9.5) | ||

| Unemployed | 557 (22.2) | 213 (53.9) | 27 (29.3) | 83 (26.1) | 2383 (77.2) | 586 (96.7) | 55 (88.7) | 171 (90.5) | ||

| Smoking status | 0.024 | 0.016 | ||||||||

| Ever | 1085 (43.2) | 149 (37.7) | 42 (45.7) | 115 (36.2) | 182 (5.9) | 17 (2.8) | 2 (3.2) | 9 (4.8) | ||

| Never | 1425 (56.8) | 246 (62.3) | 50 (54.3) | 203 (63.8) | 2903 (94.1) | 589 (97.2) | 60 (96.8) | 180 (95.2) | ||

| Physical activity | 0.135 | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| Low/mod | 1491 (59.4) | 256 (64.8) | 56 (60.9) | 202 (63.5) | 1814 (58.8) | 422 (69.6) | 37 (59.7) | 126 (66.7) | ||

| High | 1019 (40.6) | 139 (35.2) | 36 (39.1) | 116 (36.5) | 1271 (41.2) | 184 (30.4) | 25 (40.3) | 63 (33.3) | ||

| Chronic disease | 787 (31.4) | 330 (83.5) | 54 (58.7) | 154 (48.4) | < 0.001 | 1402 (45.4) | 545 (89.9) | 43 (69.4) | 140 (74.1) | < 0.001 |

| HRQoL | ||||||||||

| PCS | 50.79 ± 7.09 | 46.44 ± 8.52 | 47.71 ± 7.72 | 49.97 ± 6.83 | < 0.001 | 48.00 ± 8.44 | 41.88 ± 9.52 | 44.47 ± 9.47 | 45.22 ± 9.64 | < 0.001 |

| Physical function | 90.30 ± 7.09 | 79.94 ± 27.84 | 83.97 ± 22.11 | 88.29 ± 21.07 | < 0.001 | 82.50 ± 25.43 | 65.84 ± 32.31 | 70.16 ± 30.98 | 74.87 ± 28.31 | < 0.001 |

| Role physical | 87.05 ± 18.68 | 81.49 ± 24.28 | 83.56 ± 21.04 | 88.56 ± 17.15 | < 0.001 | 75.96 ± 23.05 | 63.39 ± 27.49 | 66.33 ± 24.65 | 72.02 ± 26.36 | < 0.001 |

| Bodily pain | 84.94 ± 20.23 | 82.66 ± 24.03 | 82.88 ± 23.42 | 86.08 ± 20.47 | 0.166 | 75.11 ± 24.62 | 66.96 ± 28.43 | 70.56 ± 27.73 | 71.43 ± 26.88 | < 0.001 |

| General health | 53.18 ± 23.06 | 39.18 ± 21.48 | 42.12 ± 20.28 | 47.96 ± 22.11 | < 0.001 | 48.69 ± 22.81 | 32.88 ± 17.63 | 37.90 ± 24.27 | 38.89 ± 20.19 | < 0.001 |

| MCS | 50.29 ± 10.21 | 51.70 ± 10.48 | 51.40 ± 10.56 | 51.28 ± 10.08 | 0.032 | 46.65 ± 10.77 | 46.25 ± 12.05 | 43.26 ± 13.53 | 46.06 ± 12.16 | 0.208 |

| Vitality | 70.19 ± 23.47 | 66.01 ± 27.68 | 68.48 ± 28.19 | 72.72 ± 23.68 | 0.006 | 60.91 ± 25.33 | 54.66 ± 29.56 | 52.02 ± 30.13 | 59.26 ± 27.29 | < 0.001 |

| Social function | 85.18 ± 23.11 | 84.62 ± 24.98 | 84.51 ± 25.64 | 84.36 ± 25.83 | 0.915 | 78.75 ± 26.59 | 74.51 ± 30.28 | 67.39 ± 29.54 | 73.28 ± 30.62 | < 0.001 |

| Role emotional | 79.84 ± 21.27 | 81.87 ± 22.14 | 82.61 ± 22.69 | 83.29 ± 19.80 | 0.015 | 70.89 ± 23.52 | 69.35 ± 25.65 | 64.92 ± 25.89 | 70.24 ± 26.02 | 0.183 |

| Mental health | 74.62 ± 20.47 | 75.54 ± 22.12 | 74.59 ± 21.25 | 75.00 ± 21.98 | 0.871 | 66.73 ± 21.59 | 60.97 ± 24.66 | 59.07 ± 25.52 | 63.76 ± 24.88 | < 0.001 |

Categorical and continuous variables are expressed as mean ± SD and number (%), respectively.

PCS physical component summary, MCS mental component summary, HRQoL Health-related quality of life.

The P-value was assessed using Chi-square tests for categorical variables and the ANOVA test for continuous variables.

Association of BP status with HRQoL

The findings from the unadjusted regression analysis examining the association between different statuses of BP and HRQoL scores can be found in Supplementary Table 2. Furthermore, Table 2 presents the regression analysis results after adjusting for potential confounders. The adjusted results showed that compared to the normotensive population, high treatment adherence was inversely associated with the PCS scores, with β = −1.76 (p < 0.001) for men and β = −1.53 (p < 0.001) for women. There was a perceived decline in all physical HRQoL domains among hypertensive females with complete treatment adherence. In men, exemplary commitment to treatment was negatively related to physical HRQoL domains, except for bodily pain. Regarding mental HRQoL, the findings illustrated that, except for an inverse association for vitality in participants with good adherence to BP-lowering drugs (β = −3.29, p = 0.024), no significant association was observed between mental HRQoL and BP status in men. However, in women, medication non-adherence was inversely related to the MCS (β = −3.56, p = 0.013) and the social function dimension (β = −9.46, p = 0.008). Furthermore, the findings demonstrated an inverse association between good adherence to treatment and females’ mental health (β = −2.67, p = 0.021).

Table 2.

Adjusted regression coefficient (95% CI) for the association of blood pressure groups with HRQoL according to the sex.

| Male (n = 3315) | Female (n = 3942) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HRQoL | Blood pressure status | β* (95% CI) | P-value | β (95% CI) | P-value |

| PCS | Commitment to treatment | −1.76 (−2.60, −0.92) | < 0.001 | −1.53 (−2.36, −0.70) | < 0.001 |

| Non-commitment to treatment | −1.43 (−2.92, 0.05) | 0.059 | −0.19 (−2.26, 1.88) | 0.855 | |

| Undiagnosed hypertension | 0.41 (−0.44, 1.26) | 0.343 | 0.23 (−0.99, 1.46) | 0.710 | |

| Physical function | Commitment to treatment | −4.18 (−6.61, −1.76) | < 0.001 | −3.69 (−6.29, −1.09) | 0.005 |

| Non-commitment to treatment | −2.37 (−6.66, 1.92) | 0.279 | −3.02 (−9.40, 3.46) | 0.361 | |

| Undiagnosed disease | 1.02 (−1.43, 3.46) | 0.414 | 0.89 (−2.94, 4.72) | 0.649 | |

| Role physical | Commitment to treatment | −3.38 (−5.68, −1.08) | 0.004 | −3.71 (−6.08, −1.34) | 0.002 |

| Non-commitment to treatment | −2.24 (-6.30, 1.83) | 0.281 | −3.21 (−9.11, 2.69) | 0.286 | |

| Undiagnosed hypertension | 2.03 (−0.09, 5.55) | 0.069 | 1.84 (−1.66, 5.33) | 0.303 | |

| Bodily pain | Commitment to treatment | −2.28 (−4.06, 0.20) | 0.062 | −2.71 (−5.27, −0.16) | 0.037 |

| Non-commitment to treatment | −1.88 (−6.26, 2.51) | 0.401 | −0.34 (−6.71, 6.02) | 0.916 | |

| Undiagnosed disease | 1.08 (−1.42, 3.58) | 0.396 | 0.06 (−3.71, 3.83) | 0.975 | |

| General health | Commitment to treatment | −5.77 (−8.35, −3.19) | < 0.001 | −5.27 (−7.39, −3.15) | < 0.001 |

| Non-commitment to treatment | −5.25 (−9.82, −0.69) | 0.024 | −2.90 (−6.03, 0.23) | 0.069 | |

| Undiagnosed hypertension | −1.17 (−3.77, 1.43) | 0.377 | −2.90 (−8.18, 2.38) | 0.281 | |

| MCS | Commitment to treatment | −0.41 (−1.61, 0.79) | 0.505 | −0.73 (−1.86, 0.39) | 0.201 |

| Non-commitment to treatment | 0.11 (−2.02, 2.23) | 0.923 | −3.56 (−6.36, −0.76) | 0.013 | |

| Undiagnosed hypertension | 0.03 (−1.19, 1.24) | 0.965 | −0.79 (−2.44, 0.87) | 0.352 | |

| Vitality | Commitment to treatment | −3.29 (−6.15, −0.43) | 0.024 | −2.48 (−5.12, 0.17) | 0.066 |

| Non-commitment to treatment | −1.15 (−6.21, 3.92) | 0.657 | −6.17 (−12.76, 0.42) | 0.067 | |

| Undiagnosed hypertension | 2.56 (−0.33, 5.44) | 0.082 | 0.80 (−3.10, 4.70) | 0.688 | |

| Social function | Commitment to treatment | −1.68 (−4.49, 1.14) | 0.242 | −1.41 (−4.19, 1.38) | 0.322 |

| Non-commitment to treatment | −1.28 (−6.26, 3.70) | 0.614 | −9.46 (−16.40, −2.52) | 0.008 | |

| Undiagnosed hypertension | −1.61 (−4.45, 1.22) | 0.265 | −3.64 (−7.75, 0.47) | 0.082 | |

| Role emotional | Commitment to treatment | −1.69 (−4.18, 0.81) | 0.184 | −1.63 (−4.05, 0.80) | 0.189 |

| Non-commitment to treatment | 0.82 (−3.59, 5.23) | 0.716 | −5.55 (−11.60, 0.50) | 0.072 | |

| Undiagnosed disease | 1.66 (−0.85, 4.18) | 0.195 | −0.40 (−3.98, 3.18) | 0.825 | |

| Mental health | Commitment to treatment | −0.84 (−3.31, 1.63) | 0.505 | −2.67 (−4.93, −0.41) | 0.021 |

| Non-commitment to treatment | −0.86 (−5.23, 3.51) | 0.699 | −5.43 (−11.06, 0.20) | 0.059 | |

| Undiagnosed hypertension | −0.61 (−3.10, 1.88) | 0.629 | −1.06 (−4.39, 2.27) | 0.533 | |

Models are adjusted for age, BMI, chronic disease, occupation, education, marital status, smoking, and physical activity.

HRQoL Health-related quality of life, PCS Physical component summary, MCS Mental component summary, CI confidence interval.

*β represents the difference in the mean value of the HRQoL score for each blood pressure group compared to the normotensive.

Association of BP with depression, anxiety, and stress

Table 3 displays the participants’ levels of depression, anxiety, and stress across different BP groups and sexes. According to the DASS-21 results, women compared to men scored higher on DASS-21 subscales, such that the mean score of depression in females with diagnosed hypertension and anxiety and stress in all BP groups was placed out of the normal range. In women, the mean scores of depression and anxiety significantly differed among various BP groups (p = 0.024, p = 0.033, respectively), such that the normotensive females had the lowest scores, and the patients with poor medication adherence reported the highest scores. Simultaneously, no significant difference in the DASS-21 scores was observed between BP statuses in male participants.

Table 3.

Participants’ depression, anxiety, and stress in different blood pressure groups according to their sex.

| Male (n = 1148) | Female (n = 1301) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normotensive (n = 861) | Diagnosed hypertensive | Undiagnosed hypertension (n = 110) | P-value | Normotensive (n = 1029) | Diagnosed hypertensive | Undiagnosed hypertension (n = 57) | P-value | |||

| Commitment to treatment (n = 154) | Non-commitment to treatment (n = 23) | Commitment to treatment (n = 201) | Non-commitment to treatment (n = 14) | |||||||

| Depression | 5.40 ± 6.59 | 4.74 ± 5.40 | 7.22 ± 8.59 | 4.87 ± 6.68 | 0.353 | 7.28 ± 7.84 | 8.54 ± 8.46 | 12.14 ± 9.33 | 6.70 ± 8.64 | 0.024 |

| Anxiety | 5.62 ± 6.06 | 5.36 ± 5.16 | 6.96 ± 5.29 | 5.35 ± 6.93 | 0.659 | 7.53 ± 6.95 | 8.98 ± 8.31 | 11.29 ± 6.78 | 8.42 ± 8.06 | 0.033 |

| Stress | 12.26 ± 8.94 | 11.14 ± 8.44 | 13.39 ± 8.75 | 11.85 ± 9.89 | 0.461 | 14.90 ± 9.60 | 14.64 ± 10.20 | 20.00 ± 7.65 | 12.63 ± 8.78 | 0.059 |

Data are expressed as mean ± SD. The ANOVA test assessed the P-value.

The unadjusted association between BP and emotional states can be found in Supplementary Table 3. Additionally, Table 4 presents the findings of the adjusted regression analysis. Among men, there was no significant association between BP status and the DASS-21 subscales, including depression, anxiety, and stress. However, in women, compared to normotensive patients, good adherence to anti-hypertensive medications was associated with an average increase of 1.44 in the anxiety score (p = 0.027). Conversely, poor commitment to drug treatment was associated with higher scores in depression (β = 4.65, p = 0.031) and stress (β = 5.67, p = 0.029) symptoms.

Table 4.

Adjusted regression coefficient (95% CI) for the association of blood pressure groups with depression, anxiety, and stress according to sex.

| Male (n = 1148) | Female (n = 1301) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β*(95% CI) | P-value | β (95% CI) | P-value | ||

| Depression | Commitment to treatment | 0.22 (−1.02, 1.47) | 0.724 | 0.84 (−0.57, 2.24) | 0.245 |

| Non-commitment to treatment | 2.49 (−0.20, 5.17) | 0.069 | 4.65 (0.42, 8.87) | 0.031 | |

| Undiagnosed hypertension | 0.22 (−1.08, 1.53) | 0.737 | −0.91 (−3.07, 1.24) | 0.406 | |

| Anxiety | Commitment to treatment | 0.37 (−0.79, 1.54) | 0.528 | 1.44 (0.17, 2.72) | 0.027 |

| Non-commitment to treatment | 1.58 (−0.93, 4.08) | 0.217 | 3.75 (−0.10, 7.48) | 0.054 | |

| Undiagnosed hypertension | 0.07 (−1.15, 1.29) | 0.916 | 0.63 (−1.32, 2.58) | 0.527 | |

| Stress | Commitment to treatment | 0.88 (−0.84, 2.59) | 0.315 | 0.87 (−0.82, 2.56) | 0.311 |

| Non-commitment to treatment | 2.08 (−1.61, 5.77) | 0.268 | 5.67 (0.59, 10.75) | 0.029 | |

| Undiagnosed hypertension | 0.49 (−1.31, 2.28) | 0.595 | −2.11 (−4.70, 0.48) | 0.110 | |

Models are adjusted for age, BMI, chronic disease, occupation, education, marital status, smoking, and physical activity.

CI confidence interval.

*β represents the difference in the mean value of the DASS score for each blood pressure group compared to the normotensive.

Sensitivity analysis

Supplementary Table 4 presents the findings of adjusted regression for the association between different BP groups and HRQoL using imputed data. The results indicate that in both sexes, the association of different BP statuses with the MCS and its subscales remains consistent with the results derived from the observed data. Additionally, the results for the PCS and its dimensions are broadly consistent with the findings obtained from the observed data, with a few exceptions. In male participants, compared to the normotensive group, the role physical dimension was significantly higher in the undiagnosed hypertension group (β = 2.29, p = 0.049), and the bodily pain dimension was lower in the high adherence to medications group (β = −2.85, p = 0.019). These findings differ slightly from the observed data. Furthermore, the general health subscale displayed a significant difference compared to the observed data in females with an exemplary commitment to treatment. However, it is worth noting that the three mentioned subscales exhibited marginal significance with the same direction in previous analyses based on the observed data.

Supplementary Table 5 displays the results of adjusted regression analyses examining the association between different BP groups and emotional states using imputed data. The findings from the imputed data were entirely consistent with the results from the observed data in females. In males, the results were broadly similar to the conclusions from the observed data, with one exception related to depression in hypertensive patients with poor medication adherence. However, this association was also borderline significant with the same direction in the observed data results.

Discussion

The present study found that individuals with undiagnosed hypertension, regardless of sex, did not experience any impairment in HRQoL or emotional states compared to those with previously diagnosed hypertension. However, the study did confirm that high adherence to anti-hypertensive medications harmed the physical HRQoL in both men and women. Moreover, a sex-specific association between BP and emotional states was identified. Specifically, in men, no significant association was found between BP and emotional states. However, among hypertensive women, good adherence to treatment was associated with a higher likelihood of experiencing anxiety, whereas those with poor adherence to medications were more likely to manifest symptoms of depression and stress.

The current study suggests that regardless of gender, individuals with undiagnosed hypertension, irrespective of their treatment adherence, did not experience any impairment in mental and physical HRQoL and mental health. These findings are consistent with previous studies conducted on multi-ethnic Asian17 and Spanish populations16 but contradictory to investigations in Thai18 and Chinese37 populations, which found higher and lower HRQoL among those with undiagnosed hypertension, respectively. In terms of emotional states, the current findings are inconsistent with the study by Hamer et al.19, which found no association, and with the study by Ang et al.38, which found elevated odds of emotional disorders among individuals with undiagnosed hypertension. The asymptomatic nature of hypertension may partly explain the lack of observed associations, as many individuals with undiagnosed hypertension may not experience any symptoms related to high BP and, therefore, report no changes in their HRQoL and emotional conditions39. Another possibility could be related to factors associated with hypertension diagnosis, such as labeling (awareness of being hypertensive). Accordingly, several studies have shown that labeling individuals as hypertensive, beyond the disease itself, can adversely affect specific health indicators and is associated with poorer quality of life and mental distress17,18,40. Therefore, it is reasonable to hypothesize that individuals who are not labeled as hypertensive may not perceive the impact of their condition, potentially leading to difficulties in detecting the association between BP and mentioned outcomes.

The present study indicated that among both men and women, individuals with hypertension who exhibit high adherence to medication reported lower physical HRQoL compared to other study groups. These results align with a previous population-based survey that also demonstrated poorer quality of life among hypertensive patients who were on medication15. However, these findings contradict the results of two prior studies conducted in different countries, namely the USA and India41,42. It is worth noting that the discrepancy between the results underscores the intricate nature of the association between medication adherence and physical HRQoL, suggesting that various factors, including cultural differences, healthcare systems, and variations in study methodologies, may contribute to these inconsistencies. The observed associations between medication adherence and physical aspects of HRQoL may be attributed to several factors. Firstly, hypertension itself can lead to various physical symptoms and complications that may impact overall well-being and quality of life14. Additionally, antihypertensive treatment could also be a contributing factor, such as some medications used to control blood pressure may have side effects that negatively impact physical health and well-being17.

This study reveals that the mental aspects of HRQoL were more affected in women compared to men. The findings demonstrate that in hypertensive men with high adherence to blood pressure-lowering medications, worse mental HRQoL was limited to vitality. However, MCS and all related domains showed significant or nearly significant deterioration in hypertensive women with low medication adherence. Furthermore, women with high medication adherence showed lower scores in the mental health and vitality subscales. These results are consistent with a longitudinal study conducted among older patients with hypertension, which found that low medication adherence harmed mental HRQoL43. However, two previous studies in Pakistan and Iraq revealed that medication adherence was associated with improved self-rated health in hypertensive patients44,45. Additionally, a 2016 systematic review and meta-analysis suggested that good medication adherence enhances the mental HRQoL of hypertensive patients46. A combination of biological, psychological, and social factors can create a unique vulnerability in women with low medication adherence, leading to a more pronounced impairment in mental HRQoL compared to men. Women experience high hormonal fluctuations throughout their lives (e.g., menstrual cycle, pregnancy, menopause) that can affect mood and emotional well-being. In addition, the declined mental HRQoL in low medication adherence women may be partially attributed to their tendency towards stricter adherence to healthy behaviors and practices as such several studies have shown that women are generally more health-conscious, seek medical care more frequently, and have better adherence to treatment47,48. Additionally, women compared to men often employ different coping strategies and may be more likely to internalize stress, leading to higher levels of anxiety and depression49. Furthermore, women may have a stronger association between their health status and self-worth, making them more vulnerable to declines in mental HRQoL when facing health challenges50. Besides, women often face societal pressures regarding caregiving and health management, which can contribute to stress and feelings of inadequacy, especially if they struggle with medication adherence42. On the other hand, the declined mental health subscale among high treatment adherence women may involve several factors. One potential reason is the nature of the disease itself. Living with a chronic condition like hypertension specifically in women could be more stressful and challenging, which can harm mental well-being51. In addition, different societal expectations regarding health and caregiving can create additional stress for women, making them feel inadequate if they perceive their health management as insufficient, even when adhering to treatment. Additionally, the observed association could be somewhat attributed to the adverse psychiatric effects of antihypertensive medications. Some medications used to treat hypertension have been associated with potential side effects that can affect mental health. These adverse effects might include mood changes, depression, anxiety, or cognitive difficulties52,53. Furthermore, the observed decline in vitality of men and women with high adherence to therapy may be explained by the concept of vitality itself, as well as the psychiatric consequences of blood pressure medications. Vitality refers to a psychological sense of aliveness, enthusiasm, or energy, and is assessed through questions about a person’s energy level, fatigue, and overall well-being54. Therefore, it is reasonable to hypothesize that vitality decreases due to the adverse effects of elevated blood pressure on physical functioning. Consistent with this hypothesis, several studies have confirmed that hypertension limits the ability of affected patients to engage in certain activities, such as exercise or social events55. Another possibility could be the adverse effects of antihypertensive drugs, such as tiredness or dizziness, which could exacerbate the limitations mentioned above53.

This study revealed a sex difference in the association between emotional states and BP. Specifically, there was no observed link between different BP states and psychological disorders in men. However, in women, negative emotional states were only evident in those who were aware of their hypertension. These findings align with a cross-cultural population-based European study, which also reported an increased risk of psychological distress among individuals diagnosed with hypertension25. Additionally, other studies have indicated that individuals labeled as hypertensive or mislabeled as hypertensive tend to experience higher mental distress levels than those unaware of their hypertension56. The observed sex difference in the association between emotional states and BP could be attributed to existing biological and hormonal differences between men and women57. Research suggests that women compared to men may have different levels of certain neurotransmitters (like serotonin) that regulate mood. This can make them more vulnerable to anxiety and depression, particularly when they are aware of a chronic health condition58. In addition, women experience significant hormonal changes throughout their lives (e.g., menstrual cycles, pregnancy, menopause) can influence mood and emotional stability, making women more susceptible to experiencing negative emotional states when faced with health issues like hypertension59. Additionally, societal and cultural norms may play a role in shaping the expression and reporting of emotional states in men and women. Men, traditionally, may be more prone to suppressing or downplaying their emotional experiences, which could impact the observed link between emotional states and BP. Conversely, women may be more socially encouraged to express their emotions, potentially leading to a stronger association between emotional states and physiological responses, including BP60. Another possibility is related to different health-seeking behaviors in men and women. Women who are aware of their hypertension may exhibit greater vigilance in monitoring their health, which could lead to a deterioration in their emotional well-being61. Moreover, some evidence suggests that awareness of having high BP can trigger an increase in sympathetic activity, which may partially explain the role of awareness in the deterioration of mental health53,62. The current study further discovered that anxiety was manifested in women with high medication adherence, whereas depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms appeared in those with low commitment to treatment. Berga and Smith, 2012 The manifestation of anxiety in patients with high medication adherence and the negative consequences stemming from disease awareness could be explained by the neuropsychiatric side effects of certain BP-lowering medications63. However, these mechanisms fail to fully elucidate the manifestation of depression, anxiety, and stress in hypertensive females with low medication adherence. In this regard, the study explored the association between mental HRQoL and emotional states to understand these findings better. Our results indicated that the manifestation of negative emotional states in women with poor adherence to anti-hypertensive medication was consistent with a decline in mental HRQoL, including MCS and its related subscales. Previous studies have consistently demonstrated a decrease in HRQoL among individuals experiencing mental distress, with anxiety and stress frequently identified as strong predictors of reduced HRQoL64,65. These findings suggest the possibility of reverse causality in the relationship between emotional states and BP. In this context, hypertension awareness may be associated with psychological distress, and negative emotional states could contribute to poor treatment adherence and uncontrolled BP. Consequently, ongoing concern about the consequences of inadequate BP control may harm mental HRQoL. In other words, this study, which places hypertension awareness as a central concept in line with prior research, confirms an overlap between mental distress and an individual’s self-perception of mental health66.

This study contains some strengths and limitations. A large population-based study conducted in a Middle Eastern country provided a unique opportunity to determine the sex-specific association between different BP statutes with HRQoL and emotional states, considering the contribution of awareness and commitment to treatment. However, it is essential to acknowledge the limitations of the study. Firstly, the study’s cross-sectional design limits its ability to establish a cause-and-effect association between the variables. Another limitation is that the assessment of disease awareness relied on self-report, which is susceptible to reporting and recall biases. Additionally, commitment to treatment was assessed using a single question. Although this approach could be an acceptable way to screen for medication adherence, for example, a single-question test for drug use was validated as an effective screening tool in a sample of primary care patients67. Furthermore, the generalizability of the study findings may be limited to communities with similar cultural and socio-economic characteristics. In addition, due to the absence of a universally accepted threshold for determining the clinical significance of HRQoL scores, interpretation of the clinical effects of the results is difficult.

Conclusion

The current study found that the individuals with undiagnosed disease have similar HRQoL and emotional states compared to the normotensive participants, which may explain why these individuals do not seek medical care. The declined physical perception of health in hypertensive patients with high adherence to medications compared with those with low medication adherence and undiagnosed disease implied the prognostic value of commitment to treatment compared to disease awareness on physical HRQoL. In addition, the mental perception of health and emotional states of women, compared to men, were more affected by their BP status, and it was such that the occurrence of negative emotional states was consistent with the decline in mental HRQoL of hypertensive women and mainly in those with low medication adherence. Moreover, our findings highlighted that hypertension awareness was significantly associated with reduced mental HRQoL and depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms, which may lead to low adherence to treatment. This study highlights the significance of psychiatric assessment, counseling, and support services while taking into account gender-specific differences among hypertensive patients. It also emphasizes the necessity for customized interventions for both men and women to improve their mental well-being and adherence to treatment.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We thank the research team members and TLGS participants for contributing to the study.

Author contributions

MN, PA, and FA designed the study. LCH and NI carried out the statistical analysis. All authors contributed to the interpretation of data. MN, AZ, and LCH drafted the manuscript. PA supervised and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-77857-x.

References

- 1.Zhou, B. et al. Worldwide trends in hypertension prevalence and progress in treatment and control from 1990 to 2019: a pooled analysis of 1201 population-representative studies with 104 million participants. Lancet398 (10304), 957–980 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oori, M. J. et al. Prevalence of HTN in Iran: meta-analysis of published studies in 2004–2018. Curr. Hyper. Rev.15 (2), 113–122 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mirzaei, M., Mirzaei, M., Bagheri, B. & Dehghani, A. Awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension and related factors in adult Iranian population. BMC Public Health20, 1–10 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hypertension. (2023).

- 5.Afsargharehbagh, R. et al. Hypertension and pre-hypertension among Iranian adults population: a meta-analysis of prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control. Curr. Hyper. Rep.21, 1–13 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Niknam et al. Improving community readiness among Iranian localcommunities to prevent childhood obesity. BMC Public Health 23(1), 344 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Loke, W. H. & Ching, S. M. Prevalence and factors associated with psychological distress among adult patients with hypertension in a primary care clinic: a cross-sectional study. Malays. Fam. Physician17 (2), 89 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heshmati, H., Maghsouldloo, D. & Mansourian, M. Health related quality of life in patients with high blood pressure in the rural areas of Golestan province, Iran. Health Scope10.17795/jhealthscope-20780 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bolton, D. & Gillett, G. The Biopsychosocial Model of Health and Disease (Springer, 2019). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheraghi et al. How do active and passive cigarette smokers in Iran Evaluate Their Health? A sex-specific analysis on the full-spectrum of quality of life. Nicotine and Tobacco Res. 26(7), 913–921 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Self-rated fair or poor health among adults with diabetes—United States, 1996–2005. Morbidity Mortal. Weekly Rep.55 (45), 1224–1227 (2006). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hayes, D. K., Denny, C. H., Keenan, N. L., Croft, J. B. & Greenlund, K. J. Health-related quality of life and hypertension status, awareness, treatment, and control: National health and nutrition examination survey, 2001–2004. J. Hyper.26 (4), 641–647 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Youssef, R. M., Moubarak, I. I. & Kamel, M. I. Factors affecting the quality of life of hypertensive patients. EMHJ Eastern Mediterranean Health J.11 (1–2), 109–118 (2005). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang, X. et al. Correlation between hypertension label and self-rated health in adult residents in China. Zhonghua liu xing bing xue za zhi=Zhonghua liuxingbingxue zazhi41 (3), 379–384 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adamu, K. et al. Health related quality of life among adult hypertensive patients on treatment in Dessie City Northeast Ethiopia. PLoS One17 (9), e0268150 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mena-Martin, F. J. et al. Health-related quality of life of subjects with known and unknown hypertension: results from the population-based Hortega study. J. Hyper.21 (7), 1283–1289 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Venkataraman, K. et al. Associations between disease awareness and health-related quality of life in a multi-ethnic Asian population. PLoS One9 (11), e113802 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vathesatogkit, P. et al. Associations of lifestyle factors, disease history and awareness with health-related quality of life in a Thai population. PLoS One7 (11), e49921 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hamer, M., Batty, G. D., Stamatakis, E. & Kivimaki, M. Hypertension awareness and psychological distress. Hypertension56 (3), 547–550 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guha M. APA College Dictionary of Psychology. Reference Reviews, 31(2), 11 (2017).

- 21.Noorbala, A. A. et al. Mental health survey of the Iranian adult population in 2015. Arch. Iran. Med.20 (3), 0–0 (2017). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carroll, D., Phillips, A. C., Gale, C. R. & Batty, G. D. Generalized anxiety and major depressive disorders, their comorbidity and hypertension in middle-aged men. Psychosomat. Med.72 (1), 16–19 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yan, L. L. et al. Psychosocial factors and risk of hypertension: the coronary artery risk development in young adults (CARDIA) study. JAMA290 (16), 2138–2148 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Licht, C. M. et al. Depression is associated with decreased blood pressure, but antidepressant use increases the risk for hypertension. Hypertension53 (4), 631–638 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmitz, N., Thefeld, W. & Kruse, J. Mental disorders and hypertension: factors associated with awareness and treatment of hypertension in the general population of Germany. Psychosomat. Med.68 (2), 246–252 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ladak, L. A. et al. Exploring the influence of socio-cultural factors and environmental resources on the health related quality of life of children and adolescents after congenital heart disease surgery: parental perspectives from a low middle income country. J. Patient-Report. Outcomes4, 1–12 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Azizi, F. et al. Prevention of non-communicable disease in a population in nutrition transition: Tehran lipid and glucose study phase II. Trials10 (1), 1–15 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Azizi, F., Zadeh-Vakili, A., & Takyar, M. Review of rationale, design, and initial findings: Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study. International Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism, 16 (4), (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Levey, A. S. et al. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am. J. Kidney Dis.39 (2) (2002). [PubMed]

- 30.Momenan, A. A. et al. Reliability and validity of the modifiable activity questionnaire (MAQ) in an Iranian urban adult population. Arch. Iran. Med.15 (5), 279–282 (2012). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lenfant, C., Chobanian, A. V., Jones, D. W. & Roccella, E. J. Seventh report of the joint national committee on the prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure (JNC 7) resetting the hypertension sails. Hypertension41 (6), 1178–1179 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Asghari, A., Saed, F. & Dibajnia, P. Psychometric properties of the depression anxiety stress scales-21 (DASS-21) in a non-clinical Iranian sample. Int. J. Psychol.2 (2), 82–102 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Montazeri, A. et al. The 12-item medical outcomes study short form health survey version 20 (SF-12v2): a population-based validation study from Tehran Iran. Health Qual. Life Outcomes9(1), 1–8 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jalali-Farahani, S. et al. Socio-demographic determinants of health-related quality of life in Tehran lipid and glucose study (TLGS). Int. J. Endocrinol. Metab.10.5812/ijem.14548 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raeisvandi, A., Amerzadeh, M., Hajiabadi, F. & Hosseinkhani, Z. Prevalence and the affecting factors on depression, anxiety and stress (DASS) among elders in Qazvin city, in the Northwest of Iran. BMC Geriatr.23 (1), 202 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Van Buuren, S. Multiple imputation of discrete and continuous data by fully conditional specification. Stat. Methods Med. Res.16 (3), 219–242 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li, W. et al. Hypertension and health-related quality of life: an epidemiological study in patients attending hospital clinics in China. J. Hyper.23 (9), 1667–1676 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ang, C. W. et al. Mental distress along the cascade of care in managing hypertension. Sci. Rep.12 (1), 15910 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sung, J. & Paik, Y. G. Experience of suffering in patients with hypertension: a qualitative analysis of in-depth interview of patients in a university hospital in Seoul Republic of Korea. BMJ Open12 (12), e064443 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Iqbal AM, Jamal SF. Essential Hypertension. StatPearls [Internet]. TreasureIsland (FL): StatPearls Publishing (2019).

- 41.Patil, M. et al. Assessment of health-related quality of life among male patients with controlled and uncontrolled hypertension in semi urban India. INQUIRY J. Health Care Org. Provision Finan.60, 00469580231167010 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Peacock, E. et al. Low medication adherence is associated with decline in health-related quality of life: results of a longitudinal analysis among older women and men with hypertension. J. Hyper.39 (1), 153 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tedla, Y. G. & Bautista, L. E. Drug side effect symptoms and adherence to antihypertensive medication. Am. J. Hyper.29 (6), 772–779 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Amer, M., Raza, A., Riaz, H., Sadeeqa, S. & Sultana, M. Hypertension-related knowledge, medication adherence and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) among hypertensive patients in Islamabad Pakistan. Trop. J. Pharm. Res.18 (5), 1123–1132 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ghayadh, A. A. & Naji, A. B. Treatment adherence and its association to quality of life among patients with hypertension. Pak. Heart J.56 (2), 44–49 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Souza, A. C. C. D., Borges, J. W. P., & Moreira, T. M. M. Quality of life and treatment adherence in hypertensive patients: systematic review with meta-analysis. Revista de saude publica 50 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Thompson, A. E. et al. The influence of gender and other patient characteristics on health care-seeking behaviour: a QUALICOPC study. BMC Fam. Pract.17 (1), 1–7 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hong, S. H. Potential for physician communication to build favorable medication beliefs among older adults with hypertension: a cross-sectional survey. PLoS One14, e0210169 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nolen-Hoeksema, S. Emotion regulation and psychopathology: The role of gender. Ann. Rev. Clin. Psychol.8 (1), 161–187 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chamberlain, J. et al. Women’s perception of self-worth and access to health care. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstetr.98 (1), 75–79 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Van Wilder, L. et al. Living with a chronic disease: insights from patients with a low socioeconomic status. BMC Fam. Pract.22, 1–11 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pittman, D. G., Tao, Z., Chen, W. & Stettin, G. D. Antihypertensive medication adherence and subsequent healthcare utilization and costs. Am. J. Manag. Care16 (8), 568–576 (2010). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Carnovale, C. et al. Antihypertensive drugs and brain function: mechanisms underlying therapeutically beneficial and harmful neuropsychiatric effects. Cardiovasc. Res.119 (3), 647–667 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Guérin, E. Disentangling vitality, well-being, and quality of life: A conceptual examination emphasizing their similarities and differences with special application in the physical activity domain. J. Phys. Act. Health9 (6), 896–908 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Polegato, B. F. & de Paiva, S. A. Hypertension and exercise: a search for mechanisms. Arquiv. Brasileiros Cardiol.111, 180–181 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pickering, T. G. Now we are sick: labeling and hypertension. J. Clin. Hyper.8 (1), 57 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Colineaux, H., Neufcourt, L., Delpierre, C., Kelly-Irving, M. & Lepage, B. Explaining biological differences between men and women by gendered mechanisms. Emerging Themes Epidemiol.20 (1), 2 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jovanovic, H. et al. Sex differences in the serotonin 1A receptor and serotonin transporter binding in the human brain measured by PET. Neuroimage39 (3), 1408–1419 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Berga, S. L. & Smith, Y. R. Hormones Mood and Affect. In Handbook of Neuroendocrinology (eds Berga, S. L. & Smith, Y. R.) (Elsevier, 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kanbara, K. & Fukunaga, M. Links among emotional awareness, somatic awareness and autonomic homeostatic processing. BioPsychoSoc. Med.10 (1), 16 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shi, P. et al. A hypothesis of gender differences in self-reporting symptom of depression: implications to solve under-diagnosis and under-treatment of depression in males. Front. Psychiatr.12, 589687 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Danarastri, S., Perry, K. E., Hastomo, Y. E. & Priyonugroho, K. Gender differences in health-seeking behaviour, diagnosis and treatment for TB. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis.26 (6), 568 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rostrup, M., Mundal, H. H., Westheim, A. & Eide, I. Awareness of high blood pressure increases arterial plasma catecholamines, platelet noradrenaline and adrenergic responses to mental stress. J. Hyper.9 (2), 159–166 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Trompenaars, F. J., Masthoff, E. D., Van Heck, G. L., de Vries, J. & Hodiamont, P. P. Relationships between social functioning and quality of life in a population of Dutch adult psychiatric outpatients. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatr.53 (1), 36–47 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Berlim, M. T., McGirr, A. & Fleck, M. P. Can sociodemographic and clinical variables predict the quality of life of outpatients with major depression?. Psychiatr. Res.160 (3), 364–371 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pfeuffer-Jovic, E., Joa, F., Halank, M., Krannich, J. H. & Held, M. Anxiety, depression and quality of life in pulmonary hypertension: A comparison of incident and prevalent cases. Respiration101 (8), 784–792 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Smith, P. C. et al. A single-question screening test for drug use in primary care. Arch. Intern. Med.170 (13), 1155–1160 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Murad, H., Basheikh, M., Zayed, M., Albeladi, R. & Alsayed, Y. The association between medication non-adherence and early and late readmission rates for patients with acute coronary syndrome. Int. J. Gener. Med.15, 6791 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.