Abstract

The relationship between serum uric acid (SUA) and mortality in patients with cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains controversial. We aimed to explore the relationship between SUA and all-cause mortality (ACM) and cardiovascular mortality (CVM) in adult patients with CVD. This cohort study included 3977 patients with CVD from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2005–2018). Death outcomes were determined by linking National Death Index (NDI) records through December 31, 2019. We explored the association of SUA with mortality using weighted Cox proportional hazards regression models, subgroup analysis, Kaplan-Meier survival curves, weighted restricted cubic spline (RCS) models, and weighted threshold effect analysis among patients with CVD. During a median follow-up of 68 months (interquartile range, 34–110 months), 1,360 (34.2%) of the 3,977 patients with cardiovascular disease died, of which 536 (13.5%) died of cardiovascular deaths and 824 (20.7%) died of non-cardiovascular deaths. In a multivariable-adjusted model (Model 3), the risk of ACM (HR 1.38, 95% CI 1.16–1.64) and the risk of CVM (HR 1.39, 95% CI 1.04–1.86) for participants in the SUA Q4 group were significantly higher. In patients with CVD, RCS regression analysis revealed a nonlinear association (p < 0.001 for all nonlinearities) between SUA, ACM, and CVM in the overall population and in men. Subgroup analysis showed a nonlinear association between ACM and CVM with SUA in patients with CVD combined with chronic kidney disease (CKD), with thresholds of 5.49 and 5.64, respectively. Time-dependent ROC curves indicated areas under the curve of 0.61, 0.60, 0.58, and 0.55 for 1-, 3-, 5-, and 10-year survival for ACM and 0.69, 0.61, 0.59, and 0.56 for CVM, respectively. We demonstrate that SUA is an independent prognostic factor for the risk of ACM and CVM in patients with CVD, supporting a U-shaped association between SUA and mortality, with thresholds of 5.49 and 5.64, respectively. In patients with CVD combined with CKD, the association of the ACM and the CVM with SUA remains nonlinear.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-76970-1.

Keywords: Serum uric acid, Cardiovascular disease, All-cause mortality, Cardiovascular mortality, Cohort study, NHANES

Subject terms: Cardiology, Diseases

Introduction

SUA is the ultimate oxidation product of the purine (adenine and guanine) metabolism. Uric acid(UA) is found in bodily fluids as urate, of which about two-thirds is eliminated through the kidneys1, and the remaining one-third is eliminated through the intestines2. The body’s synthesis and excretion of UA are in equilibrium under physiological conditions. When this balance is frustrated, hyperuricemia results. Many detrimental health effects, including gout attacks, hypertension, diabetes, stroke, atrial fibrillation, metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance, obesity, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, and CKD, have been linked to elevated SUA levels3–6. As a result, those who have elevated SUA may be more susceptible to CVD.

Globally, CVD is now a leading cause of illness and mortality. However, there has been continuous debate about SUA levels with the onset of CVD. There have been conflicting findings about the association between SUA and CVD risk based on epidemiologic studies. While some research has shown an inverse or null association and others have demonstrated that both low and high SUA are linked with increased CVM7,8, other studies have indicated that high SUA is associated with CVD risk. In addition, the linear relationship between SUA and the risk of death has been more discussed, while the nonlinear relationship has been less studied. The exact dose–response relationship between SUA and the risk of CVM is uncertain, and it is not clear whether there is a threshold effect between SUA and mortality. Apart from the well-established influence of gender on UA levels, age is a large and important factor influencing SUA levels. Serum urate concentrations are low in premenopausal women due to the pro-uric acid-excretory effect of estrogen. After menopause, they increase to concentrations similar to those observed in men. However, to date, no study has systematically assessed whether there are age differences in the effect of SUA on mortality risk. Based on a study by Dr. Hu, who explored the association between SUA and all-cause and specific mortality in a US population aged 18–80 years, we further analyzed the association of SUA with the risk of ACM as well as CVM in a CVD population.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

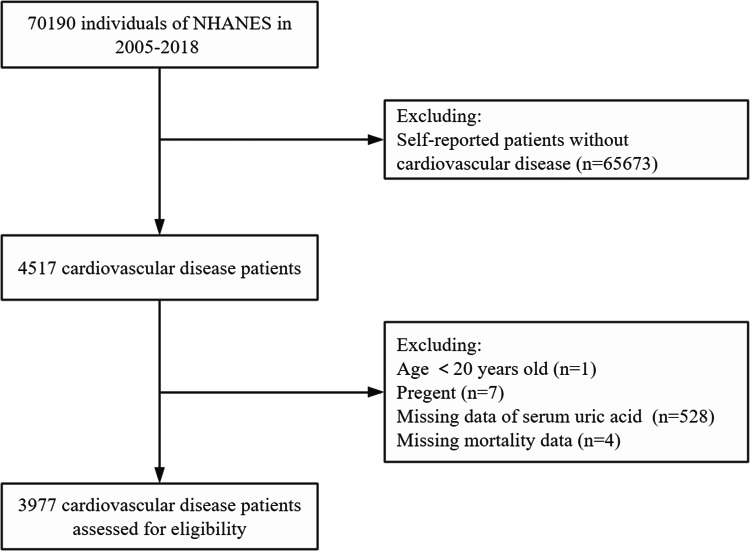

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) is a continuous, stratified, multistage sample study conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) to investigate the health status of the population of all ages in the U.S. NHANES received U.S. With Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Research Ethics Review Board approval, all participants provided informed consent, and the investigation conformed to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. We analyzed NHANES cycle data from seven study cycles (2005 to 2006, 2007 to 2008, 2009 to 2010, 2011 to 2012, 2013 to 2014, 2015 to 2016, and 2017 to 2018). Overall, 4517 of the 70,190 participants were diagnosed with CVD. After excluding individuals younger than 20 years of age (n = 1), pregnant women (n = 7), individuals with unmeasured or ineligible SUA (n = 528), and individuals with missing mortality information (n = 4), 3977 individuals with CVD were included. The process of participant inclusion and exclusion is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The flow chart of participants inclusion and exclusion in current study.

Study exposure and outcomes

In this study, the exposure variable was SUA (mg/dL). All samples were tested at the NHANES Central Laboratory. SUA was measured with the Beckman Synchron LX20 in 2005–2007, with the Beckman UniCel® DxC800 Synchron in 2009–2016, and with the Roche Cobas 6000 (c501 module) Chemistry Analyzer in 2017–2018.

The study’s endpoints were ACM and CVM. Mortality status and cause of death were determined by the NDI Public Access File as of December 31, 2019, associated with NHANES. The primary cause of death was determined according to the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10). We assessed ACM as well as mortality resulting from CVD (heart disease I00-I09, I11, I13, I20-I51, and cerebrovascular disease I60-I69).

Covariates

The following variables were collected through the Demographic and Health Questionnaire of the NHANES survey: age, sex, race, education level, marital status, smoking status, alcohol consumption, and complications such as hypertension, CKD, and diabetes. Race was categorized as non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Mexican American, and others. Education level was categorized as under high school, high school, and above high school. Marital status was categorized as single or married. The poverty income ratio (PIR) was categorized into three groups: < 1, 1–3, and > 3. Body mass index (BMI) and waist circumference (WC) data were obtained from measurements taken by professionals at the Mobile Examination Center (MEC). BMI was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared and was categorized as normal (< 25 kg/m2), overweight (25 ≤ BMI < 30 kg/m2), and obese (≥ 30 kg/m2). Smoking status was categorized as never smokers (less than 100 cigarettes in a lifetime), former smokers (≥ 100 cigarettes in a lifetime, but quit), and current smokers (at least 100 cigarettes in a lifetime, but quit). Alcohol consumption was categorized as never (defined as less than 12 drinks in lifetime), former (defined as ≥ 12 drinks in 1 year and no drinking in the last year, or no drinking in the last year but ≥ 12 drinks in lifetime), mild (defined as an average of ≤ 1 drink per day for females and ≤ 2 drinks per day for males in the past 12 months), moderate (average of 1–3 drinks per day for females and 2–4 drinks per day for males in the past 12 months), and heavy (average of ≥ 4 drinks per day for women and ≥ 5 drinks per day for men in the past 12 months)9. Physical activity was categorized as never exercising (0 min of total exercise in a week), mild exercise (0–149 min of total exercise in a week), moderate exercise (150–299 min of total exercise in a week), and high-intensity exercise (≥ 300 min of total exercise in a week) according to the total amount of time spent per week (week/minute) on a wide range of activities, including work and recreation. The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaborative Group formula. CKD was defined as a physician-diagnosed self-reported outcome or an eGFR < 60 ml/min/1.73 m2. Blood pressure was calculated as the mean of the four eligible values. Hypertension was defined as being on prescription antihypertensive medication or having a mean systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mmHg. Diabetes was defined as the self-reported results of a physician’s diagnosis or glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) ≥ 6.5%. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) was defined as the self-reported results of a physician’s diagnosis. Laboratory tests were performed at the MEC. Laboratory data included: total cholesterol (TC) [mg/dL], triglycerides (TG) [mg/dL], high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) [mg/dL], refrigerated serum glucose [mmol/L], HbA1c [%], alanine aminotransferase (ALT) [U/L], aspartate aminotransferase (ALT) [U/L], uric acid and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio (UHR), white blood cell count (WBC), and platelet count (PLT). Follow-up time was defined as the time from the interview to the date of death or the end date of follow-up. All testing protocols are available on the NHANES website.

Statistical analysis

Following the NHANES Analysis and Reporting Guide10, primary sampling units, pseudo-stratification, and masked variance in sampling weights were used to account for the multistage sampling design and ensure nationally representative estimates. Sample weights were assigned to each individual participating in NHANES. SUA is divided into quartiles from lowest (Q1) to highest (Q4). In order to maximize statistical efficacy and minimize potential bias in the exclusion of covariates in the data analysis for missing data, we used the “mice” software package and multiple interpolation based on the Random Forest approach to fill in the missing data. We also calculated Cronbach’s coefficients to reflect the internal reliability of the interpolated data, and we selected the interpolated dataset with the largest Cronbach’s coefficients for the analysis. In addition to ensure the robustness of the results, a sensitivity analysis of the interpolated datasets was performed, which showed no significant difference in the results between the interpolated datasets(Additional file 1: Supplementary Figure S1). Continuous variables were described by weighted means ± standard errors for differences between quartiles of SUA, and categorical variables were described by unweighted numbers (unweighted proportions). A one-way ANOVA was used for continuous variables and a chi-square test for categorical variables. We diagnosed the proportional hazards assumptions for ACM and CVM in model 3 using the Schoenfeld residual plot test and hypothesis testing (Additional file 1: Supplementary Table S1 and Supplementary Figure S2). Cox proportional risk models were used to estimate risk ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality. Three models controlling for confounders were included. Model 1 adjusted for age, sex, and race; Model 2 adjusted for age, sex, race, education level, PIR, marital status, BMI, smoking status, alcohol consumption, physical activity, hypertension, diabetes, COPD, and CKD. Model 3 was adjusted for age, sex, race, education level, PIR, marital status, BMI, smoking status, alcohol consumption, physical activity, hypertension, diabetes, COPD, CKD, TC, TG, HDL-C, AST, ALT, WBC, and PLT. In addition, RCS was used to visualize potential nonlinear associations between SUA, ACM, and CVM. If nonlinearity was detected, we used a recursive algorithm to calculate the inflection points between SUA and ACM and CVM, respectively, and a two-segment Cox proportional risk model was used on both sides of the inflection point to investigate the association between SUA and the risk of ACM and CVM, which is consistent with the approach of Hu et al.11. Subsequently, analyses were stratified among age, sex, alcohol consumption, smoking status, BMI, CKD, hypertension, and diabetes according to nonlinear threshold subgroups in the general population, and their interactions with mortality outcomes were explored. Further, we used Kaplan–Meier curves to illustrate the probability of survival outcomes and compared them using the log-rank test. Finally, time-dependent ROC analyses were performed using the “time ROC” package12 to assess the accuracy of SUA in predicting survival outcomes at different time points. All statistical analyses were performed using the statistical package R and EmpowerStats 2.0. A bilateral P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of the study population

Participating in this study included 3977 CVD patients (mean age: 64.87 ± 13.31 years; 54.52% male) (Fig. 1). Based on the SUA quartiles, the weighted distributions of sociodemographic characteristics and other covariates of the selected participants are shown in Table 1. The SUA ranges for quartiles Q1 through Q4 were ≤ 4.9, 5.0- < 5.9, 5.9- < 7.0, and ≥ 7 mg/dL, respectively. There were significant differences between SUA quartiles for all included characteristics, except for marital status, PIR, education level, COPD, cancer history, mean systolic blood pressure, and cancer mortality. Individuals in the SUA Q4 group were older, married, former smokers, had more comorbid hypertension and CKD, and had higher BMI, WC, UHR, TG, AST, ALT, ACM, and CVM compared with the other groups. In contrast, there were more current smokers and singles in the Q1 group, and HDL-C and eGFR were higher and negatively associated with SUA.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants.

| Serum uric acid, mg/dL | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Q1, N = 1097 (29%) | Q2, N = 968 (26%) | Q3, N = 960 (23%) | Q4, N = 952 (22%) | P-value |

| Sociodemographic | |||||

| Age, years | 63.57 ± 14.28 | 64.05 ± 13.61 | 65.33 ± 12.45 | 67.04 ± 12.20 | < 0.001 |

| Sex | < 0.001 | ||||

| Female | 651(63.00%) | 406(43.38%) | 345(35.53%) | 315(35.70%) | |

| Male | 446(37.00%) | 562(56.62%) | 615(64.47%) | 637 (64.30%) | |

| Race | < 0.001 | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 580(72.03%) | 536 (75.58%) | 523 (75.88%) | 516 (73.43%) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 197 (9.61%) | 178 (9.34%) | 228 (12.51%) | 258 (13.99%) | |

| Mexican American | 134 (5.44%) | 97(4.52%) | 98(4.68%) | 63 (3.27%) | |

| Others | 186 (12.92%) | 157(10.56%) | 111(6.93%) | 115(9.31%) | |

| Marital status | 0.8 | ||||

| Single | 522(41.93%) | 447(40.16%) | 417(39.88%) | 434 (39.77%) | |

| Married | 575(58.07%) | 521 (59.84%) | 543 (60.12%) | 518 (60.23%) | |

| Education level | 0.4 | ||||

| Under high school | 381 (23.19%) | 311 (22.34%) | 318 (25.12%) | 307 (23.97%) | |

| High school | 281 (28.93%) | 246 (29.82%) | 236 (24.91%) | 237 (24.73%) | |

| Above high school | 435 (47.88%) | 411 (47.85%) | 406 (49.97%) | 408 (51.30%) | |

| PIR | 0.11 | ||||

| < 1 | 297(19.83%) | 222 (16.94%) | 206 (13.87%) | 226 (16.92%) | |

| 1–3 | 536 (47.57%) | 489 (46.73%) | 482 (46.58%) | 485 (47.12%) | |

| > 3 | 264 (32.61%) | 257 (36.33%) | 272 (39.56%) | 241 (35.96%) | |

| Personal history | |||||

| Smoking status | < 0.001 | ||||

| Never | 472 (43.64%) | 382 (38.13%) | 340 (34.01%) | 365 (39.85%) | |

| Former | 361 (31.18%) | 375 (38.61%) | 409 (44.08%) | 434 (45.02%) | |

| Current | 264 (25.18%) | 211 (23.26%) | 211 (21.91%) | 153 (15.13%) | |

| Alcohol consumption | 0.033 | ||||

| Never | 180 (13.31%) | 131 (11.52%) | 119 (10.03%) | 130 (11.52%) | |

| Former | 331 (27.06%) | 288 (25.30%) | 275 (24.51%) | 305 (31.76%) | |

| Mild | 352 (35.70%) | 359 (39.23%) | 360 (41.93%) | 342 (40.04%) | |

| Moderate | 105 (10.87%) | 94 (10.51%) | 91 (10.98%) | 69 (5.62%) | |

| Heavy | 129 (13.06%) | 96 (13.44%) | 115 (12.55%) | 106 (11.07%) | |

| Self-reported medical conditions | |||||

| Hypertension | 812 (71.91%) | 734 (72.08%) | 763 (75.94%) | 818 (82.49%) | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes | 432 (35.51%) | 395 (35.24%) | 397 (36.75%) | 485 (48.04%) | < 0.001 |

| CKD | 180 (13.64%) | 231 (21.84%) | 307 (30.62%) | 511 (49.27%) | < 0.001 |

| COPD | 154 (13.96%) | 125 (14.78%) | 109 (11.18%) | 146 (15.70%) | 0.2 |

| Cancer history | 232 (22.95%) | 191 (20.71%) | 176(20.84%) | 224 (23.46%) | 0.6 |

| Physical examination | |||||

| BMI, kg/m2 | 28.66 ± 6.30 | 30.33 ± 7.09 | 31.37 ± 7.00 | 32.65 ± 8.00 | < 0.001 |

| WC, cm | 101.16 ± 15.15 | 105.52 ± 15.14 | 108.99 ± 16.04 | 111.35 ± 16.35 | < 0.001 |

| Mean SBP, mmHg | 129.73 ± 20.73 | 129.43 ± 20.46 | 129.36 ± 20.29 | 128.37 ± 21.41 | 0.5 |

| Mean DBP, mmHg | 68.25 ± 13.86 | 68.56 ± 12.39 | 69.02 ± 13.05 | 65.71 ± 13.59 | < 0.001 |

| Physical activity* | 0.004 | ||||

| 0 | 502 (41.67%) | 406 (37.46%) | 388 (37.61%) | 480 (47.71%) | |

| 1–149 | 169 (15.43%) | 138(15.77%) | 161 (16.03%) | 151 (14.32%) | |

| 150–299 | 98 (8.35%) | 113(11.87%) | 98 (10.58%) | 99 (11.93%) | |

| > = 300 | 328 (34.55%) | 311 (34.90%) | 313 (35.79%) | 222 (26.04%) | |

| Laboratory test | |||||

| SUA, mg/dL | 4.15 ± 0.62 | 5.47 ± 0.28 | 6.45 ± 0.32 | 8.13 ± 1.02 | < 0.001 |

| eGFR, ml/min/1.73 m2 | 83.20 ± 21.64 | 76.94 ± 21.16 | 72.49 ± 22.92 | 61.71 ± 23.79 | < 0.001 |

| HDL-C, mg/dL | 54.46 ± 17.21 | 50.34 ± 16.03 | 48.90 ± 14.73 | 46.99 ± 15.75 | < 0.001 |

| UHR | 0.08 ± 0.03 | 0.12 ± 0.04 | 0.14 ± 0.04 | 0.19 ± 0.06 | < 0.001 |

| TC, mg/dL | 181.07 ± 45.37 | 181.02 ± 48.12 | 183.49 ± 44.16 | 174.40 ± 45.76 | 0.006 |

| TG, mg/dL | 153.49 ± 132.62 | 172.00 ± 127.04 | 175.25 ± 120.26 | 177.85 ± 120.23 | < 0.001 |

| WBC,1000cells/uL | 7.44 ± 3.28 | 7.63 ± 4.15 | 7.43 ± 2.49 | 7.88 ± 3.17 | 0.009 |

| PLT,1000cells/uL | 239.69 ± 75.22 | 230.54 ± 65.13 | 225.16 ± 67.78 | 225.82 ± 71.25 | < 0.001 |

| AST, U/L | 24.18 ± 9.93 | 25.96 ± 27.11 | 26.12 ± 12.53 | 26.78 ± 22.81 | < 0.001 |

| ALT, U/L | 22.06 ± 12.56 | 24.03 ± 29.39 | 24.47 ± 14.37 | 25.58 ± 48.15 | 0.003 |

| Glu, mmol/L | 6.40 ± 2.92 | 6.23 ± 2.29 | 6.24 ± 2.31 | 6.67 ± 2.48 | < 0.001 |

| HbA1c, % | 6.13 ± 1.31 | 6.05 ± 1.12 | 6.09 ± 1.17 | 6.25 ± 1.16 | < 0.001 |

| Mortality information | |||||

| Follow-up time, month | 76.14 ± 45.70 | 75.42 ± 45.80 | 78.37 ± 46.18 | 70.18 ± 45.95 | 0.021 |

| All-cause mortality | 323 (25.09%) | 306 (26.32%) | 296 (27.21%) | 435 (41.77%) | < 0.001 |

| Cardiovascular mortality | 119 (9.04%) | 116 (9.66%) | 119 (10.25%) | 182 (16.24%) | < 0.001 |

| Cancer mortality | 48 (4.21%) | 53 (4.20%) | 49. (4.80%) | 83 (6.79%) | 0.085 |

Continuous variables are presented as the weighted mean ± standard error. Categorical variables are presented as an unweighted number (%). All estimates were adjusted for the survey weights of NHANES. BMI: body mass index; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate; HDL-C: high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; UHR: uric acid and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio; TC: total cholesterol; TG: triglycerides; WBC: white blood cell count; PLT: platelet count; AST: aspartate aminotransferase; ALT: alanine aminotransferase; Glu: glucose, refrigerated serum; HbA1c: glycosylated hemoglobin; WC: waist circumference; Mean SBP: mean systolic blood pressure; Mean DBP: mean diastolic blood pressure; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CKD: chronic kidney disease; PIR: the poverty income ratio.

* Physical activity was the sum of three domains of PA: OPA, TPA, and LTPA. For OPA or LTPA, minutes of vigorous PA were doubled and added to minutes of moderate PA. This was then multiplied by the number of days of activity to obtain the total minutes of PA spent in a typical week45.

Association of serum uric acid with all-cause mortality

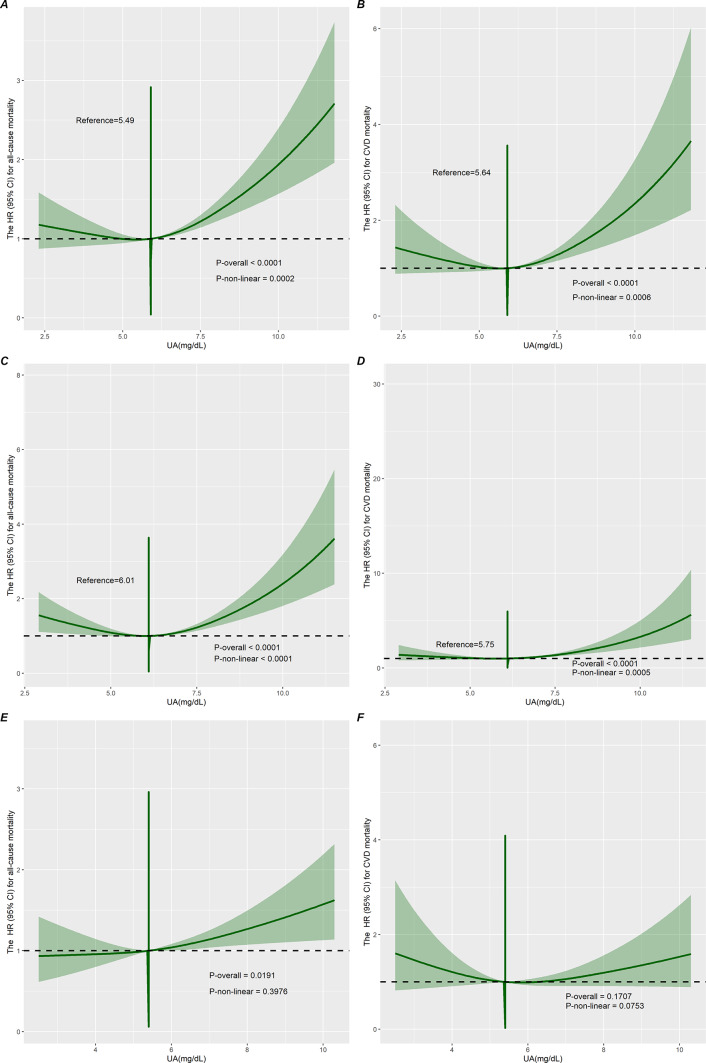

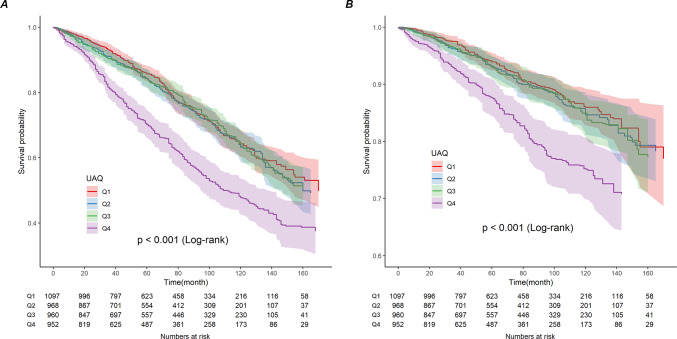

The median follow-up duration was 68 months (interquartile range (IQR), 34–110 months). During the follow-up period, 1360 all-cause deaths occurred, including 536 cardiovascular deaths and 233 cancer deaths. A nonlinear U-shaped connection between SUA and ACM was shown by RCS analysis in individuals with CVD in the overall population (nonlinear p = 0.0002) (Fig. 2A) and in men (nonlinear p < 0.0001) (Fig. 2C). We constructed three models to analyze the independent role of SUA in mortality. The HRs and 95% CIs for these three models are listed in Table 2. In the fully adjusted model (model 3), each 1 mg/dL of SUA higher was associated with a 1% increased risk of ACM. Additionally, we transformed SUA into a categorical variable (quartiles) from a continuous variable. Cox regression analyses showed a significant increase in the risk of ACM in Q4 participants compared to SUA Q1 participants from the crude model (HR 1.83, 95% CI 1.55–2.16) to the adjusted models (Model 1, Model 2, and Model 3) (HR 1.57, 95% CI 1.31–1.88; HR 1.34, 95% CI 1.13–1.58; HR 1.38, 95% CI 1.16–1.64) (Table 2). But there was no meaningful correlation between SUA and cancer mortality (Table 1). Survival rates for Kaplan–Meier ACM differed between different quartiles of SUA (p < 0.001), with participants in the SUA Q4 group having lower survival rates (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 2.

Restricted cubic spline curves showing the association of serum uric acid with the risk of all-cause mortality (A, C, and E) and cardiovascular death (B, D, and F) in the overall population and in male and female populations, respectively.

Table 2.

Association of serum uric acid with all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality in cardiovascular disease.

| Serum uric acid, mg/dL | HR (95%CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Death/No | Crude model | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| All-cause mortality | |||||

| Continuous | 1.18(1.14–1.23) | 1.14(1.08–1.19), < 0.001 | 1.09(1.05–1.14) | 1.10(1.05–1.14) | |

| Quartile | |||||

| Q1, N = 1097 | 323/774 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Q2, N = 968 | 306/662 | 1.06(0.89–1.27) | 1.02(0.85–1.22) | 1.04(0.88–1.23) | 1.06(0.89–1.25) |

| Q3, N = 960 | 296/664 | 1.04(0.88–1.24) | 0.98(0.82–1.18) | 0.96(0.80–1.15) | 0.99(0.82–1.19) |

| Q4, N = 952 | 435/517 | 1.83(1.55–2.16), | 1.57(1.31–1.88) | 1.34(1.13, 1.58) | 1.38(1.16–1.64) |

| P for trend | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.001 | |

| Cardiovascular mortality | |||||

| Continuous | 1.22(1.14–1.31) | 1.16(1.08–1.25) | 1.12(1.03–1.21) | 1.12(1.03–1.21) | |

| Quartile | |||||

| Q1, N = 1097 | 119/978 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Q2, N = 968 | 116/852 | 1.08(0.83–1.41) | 1.02(0.78–1.33) | 1.04(0.80–1.34) | 1.03(0.80–1.33) |

| Q3, N = 960 | 119/841 | 1.09(0.82–1.45) | 1.02(0.75–1.38) | 0.97(0.72–1.30) | 0.97(0.73–1.29) |

| Q4, N = 952 | 182/770 | 1.97(1.50–2.58) | 1.62(1.25–2.12) | 1.38(1.04–1.85) | 1.39(1.04–1.86) |

| P for trend | < 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.055 | 0.048 | |

Crude Model, unadjusted.

Model 1: adjusted for age, sex, race.

Model 2: adjusted for age, sex, race, marital status, BMI, education level, smoking status, alcohol consumption, physical activity, PIR, hypertension, diabetes, CKD, COPD.

Model 3: adjusted for age, sex, race, marital status, BMI, education level, smoking status, alcohol consumption, physical activity, PIR, hypertension, diabetes, CKD, COPD, HDL-C, TC, TG, WBC, PLT, AST, ALT.

Fig. 3.

Kaplan-Meier analysis for all-cause mortality (A) and cardiovascular mortality (B) categorized by serum uric acid level. The Y-axis shows probable survival (%). The x-axis shows the follow-up period (months).

Associations of serum uric acid with cardiovascular mortality

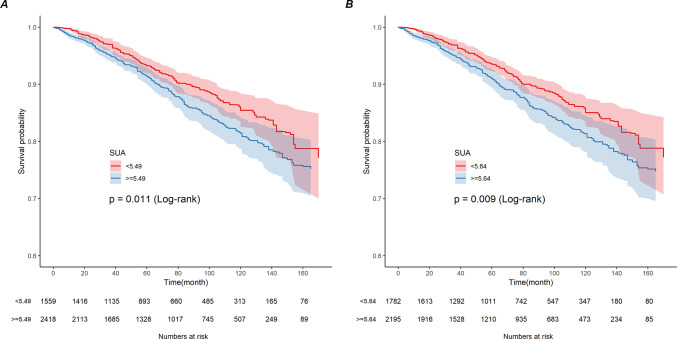

During the follow-up period, 536 cardiovascular deaths occurred. A nonlinear U-shaped correlation between SUA (quartiles) and CVM in the overall population (nonlinear p = 0.0006) and in men (nonlinear p = 0.0005) was demonstrated by the RCS model, which assessed the relationship between SUA and CVM outcomes among the overall population of patients with CVD and in men (Fig. 2B,D). Weighted multivariate Cox regression analysis additionally confirmed the association between CVM and SUA (continuous variables and quartiles) (Table 2). In the fully adjusted model (model 3), we found that every 1 mg/dL rise in SUA increased the risk of cardiovascular death by 12%. After adjusting for confounders (model 1, model 2, and model 3), the correlation between SUA (continuous variable) and CVM remained significant (HR 1.16, 95% CI 1.08–1.25; HR 1.12, 95% CI 1.03–1.21; HR 1.12, 95% CI 1.03–1.21). In the crude and adjusted models (Model 1, Model 2, and Model 3), participants in the Q4 group had significantly increased CVM by 1.97 (95% CI 1.50–2.58), 1.62 (95% CI 1.25–2.12), 1.38 (95% CI 1.04–1.85), and 1.39 (95% CI 1.04–1.86) (Table 2). The Kaplan–Meier survival plots showed a higher CVM in the SUA Q4 group compared to the Q1 patients (p < 0.001) (Fig. 3B). Meanwhile, patients on the right side of the inflection point show a higher rate of CVM than those on the left side of the inflection point, according to grouping based on different thresholds for ACM and CVM in the overall population (Fig. 4A,B).

Fig. 4.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of cardiovascular mortality by all-cause mortality threshold (A) and cardiovascular mortality threshold (B) in the overall population. The y-axis shows probable survival (%). The x-axis shows follow-up time (months).

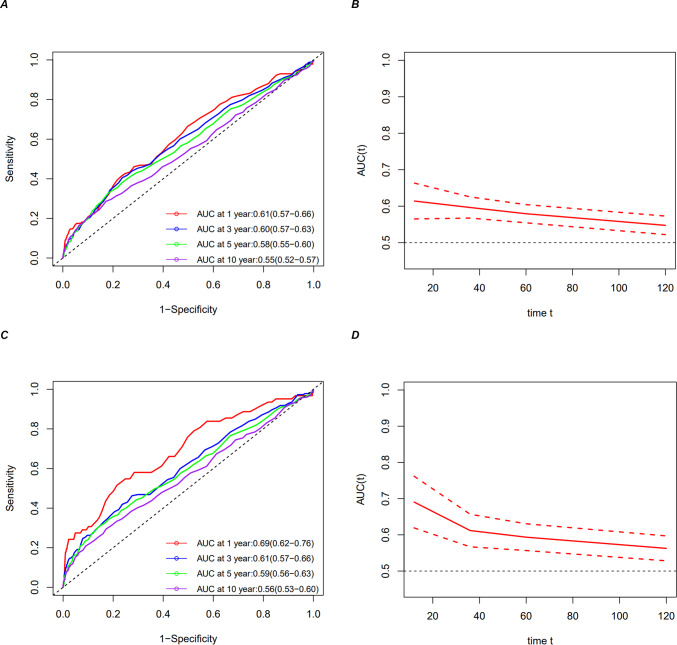

ROC analysis of the predictive value of serum uric acid for all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality in patients with cardiovascular disease

A time-dependent ROC analysis of the value of prediction of serum uric acid for ACM and CVM in patients with CVD was performed to assess the prognostic value of SUA for ACM and CVM among people with CVD. The results showed that the area under the curve (AUC) of SUA 1-year, 3-year, 5-year, and 10-year ACM were 0.61 (95% CI 0.57–0.66), 0.60 (95% CI 0.57–0.63), 0.58 (95% CI 0.55–0.60), and 0.55, respectively (95% CI 0.52–0.57) (Fig. 5A,B). The AUCs for CVM SUA at one, three, five, and ten years were, respectively, 0.69 (95%CI 0.62–0.76), 061 (95%CI 0.57–0.66), 0.59 (95%CI 0.56–0.63), and 0.56 (95%CI 0.53–0.60) (Fig. 5C,D). According to these findings, SUA appears to have a poor predictive impact for long-term ACM and CVM but a valid predictive value for short-term mortality.

Fig. 5.

Time-dependent ROC curves and time-dependent AUC values (with a 95% confidence band) of the serum uric acid for predicting all-cause mortality (A, B) and cardiovascular mortality (C, D).

Nonlinear association between serum uric acid and all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality

RCS was used to investigate nonlinear relationships among SUA, ACM, and CVM in the overall population, men and women, respectively (Fig. 2). After adjusting for age, sex, race, education level, PIR, marital status, BMI, smoking status, alcohol consumption, physical activity, hypertension, diabetes, COPD, CKD, TC, TG, HDL-C, AST, ALT, WBC, and PLT, the results showed a U-shaped relationship between SUA, ACM, and CVM observed only in the overall population and in men (Fig. 2A–D). However, there were differences in the inflection points of SUA for ACM and CVM. The results of the two piecewise Cox regression modeling between SUA and ACM and CVM in the general population and among men are presented in Table 3 (both P for log-likelihood ratio < 0.05), which shows the inflection point for SUA was 5.49 mg/dL for ACM and 5.64 mg/dL for CVM in total and 6.01 mg/dL for ACM and 5.75 mg/dL for CVM in males. When SUA concentrations were less than 5.49 mg/dL or 5.64 mg/dL, a per 1 mg/dL decrease in the SUA level was associated with a 10.2% greater adjusted HR of ACM (HR 0.898; 95% CI 0.813, 0.992). However, there was no association with CVM (HR 0.882; 95% CI 0.759, 1.024). When SUA concentrations exceeded 5.49 mg/dL or 5.64 mg/dL, a per 1 mg/dL increase in the SUA level was associated with a 16.7% and a 23.9% greater adjusted HR of ACM and CVM, respectively (HR 1.167; 95% CI 1.114, 1.223, and HR 1.239; 95% CI 1.151, 1.334, respectively).

Table 3.

The result of a two-piecewise linear regression model between serum uric acid and all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality.

| All-cause mortality HR*(95%CI) | Cardiovascular mortality HR*(95%CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Total | ||

| Cutoff value | 5.49 | 5.64 |

| < cutoff value | 0.898 (0.813, 0.992) | 0.882 (0.759, 1.024) |

| > = cutoff value | 1.167 (1.114, 1.223) | 1.239 (1.151, 1.334) |

| P for log likelihood ratio test | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Male | ||

| Cutoff value | 6.01 | 5.75 |

| < cutoff value | 0.874 (0.786, 0.972) | 0.861 (0.763, 0.971) |

| > = cutoff value | 1.229 (1.152, 1.311) | 1.204 (1.132, 1.281) |

| P for log likelihood ratio test | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

Dichotomous cox regression models adjusted for age, sex, race, smoking status, marital status, PIR, education level, physical activity, alcohol consumption, BMI, TC, TG, HDL-C, AST, ALT, WBC, PLT, hypertension, diabetes, CKD, and COPD in addition to the variables themselves.

*HRs are the relative risk per 1 mg/dL increment of serum uric acid.

The relationship between SUA, ACM, and CVM was explored, stratified by age, sex, smoking status, alcohol consumption, BMI, hypertension, diabetes, and CKD (Table 4). The associations between SUA < 5.49 or ≥ 5.49 and ACM were significantly different only for men, previous smokers, and patients with comorbid CKD and hypertension. For every additional 1 mg/dL when SUA was ≥ 5.49, the probability of ACM rose by 18.1%, 12.8%, 16.3%, and 15.4%. For every unit decrease in SUA, there was an increase in the probability of ACM by 14.9%, 15.2%, 18.8%, and 10.9% when the index was less than 5.49. The risk of ACM was higher in the other subgroups that exhibited only SUA greater than the threshold value, except for moderate drinking. There was no difference when SUA was below the crucial value. Similarly, when SUA ≥ 5.64, the risk of CVM increased by 31.6% and 24.1% per 1 mg/dL increase in patients who had never consumed alcohol and had CKD. When the index was < 5.64, the risk of CVM increased by 29.2% and 21.7% for each 1 mg/dL decrease in SUA. With the exception of female patients who consumed moderate amounts of alcohol, other subgroups exhibiting only SUA greater than a critical value were at higher risk for CVM. When SUA was below the crucial value, nothing changed .

Table 4.

Subgroups analysis.

| Cutoff value, mg/dL | N | All-cause mortality HR* (95%CI) | P for log likelihood ratio test | Cardiovascular mortality HR* (95%CI) | P for log likelihood ratio test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 5.49 | > = 5.49 | < 5.64 | > = 5.64 | ||||

| Age | |||||||

| < 65 | 1551 | 0.979 (0.789, 1.214) | 1.174 (1.064, 1.296) | 0.184 | 0.817 (0.575, 1.160) | 1.254 (1.060, 1.482) | 0.065 |

| > = 65 | 2426 | 0.892 (0.797, 0.999) | 1.156 (1.096, 1.218) | < 0.001 | 0.897 (0.761, 1.058) | 1.222 (1.126, 1.326) | 0.005 |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 2260 | 0.851 (0.740, 0.978) | 1.181 (1.113, 1.254) | < 0.001 | 0.884 (0.715, 1.094) | 1.294 (1.181, 1.416) | 0.006 |

| Female | 1717 | 0.936 (0.806, 1.088) | 1.127 (1.043, 1.218) | 0.058 | 0.827 (0.661, 1.034) | 1.115 (0.980, 1.269) | 0.051 |

| Alcohol consumption | |||||||

| Never | 560 | 0.799 (0.634, 1.007) | 1.183 (1.046, 1.337) | 0.013 | 0.708 (0.513, 0.979) | 1.316 (1.096, 1.579) | 0.006 |

| Former | 1199 | 0.908 (0.786, 1.048) | 1.110 (1.030, 1.196) | 0.037 | 0.879 (0.709, 1.089) | 1.192 (1.060, 1.339) | 0.038 |

| Mild | 1413 | 0.911 (0.727, 1.143) | 1.198 (1.099, 1.306) | 0.052 | 0.874 (0.625, 1.222) | 1.284 (1.117, 1.476) | 0.074 |

| Moderate | 359 | 0.898 (0.577, 1.397) | 0.965 (0.746, 1.249) | 0.811 | 2.906 (0.799, 10.574) | 0.707 (0.421, 1.186) | 0.044 |

| Heavy | 446 | 1.359 (0.752, 2.454) | 1.386 (1.107, 1.736) | 0.956 | 1.979 (0.448, 8.735) | 2.493 (1.543, 4.028) | 0.792 |

| Smoking status | |||||||

| Never | 1559 | 0.904 (0.764, 1.070) | 1.192 (1.099, 1.293) | 0.013 | 0.887 (0.707, 1.114) | 1.234 (1.097, 1.389) | 0.033 |

| Former | 1579 | 0.848 (0.728, 0.987) | 1.128 (1.056, 1.206) | 0.004 | 0.820 (0.645, 1.043) | 1.203 (1.076, 1.345) | 0.016 |

| Current | 839 | 0.972 (0.778, 1.215) | 1.191 (1.051, 1.351) | 0.171 | 1.010 (0.694, 1.470) | 1.341 (1.087, 1.654) | 0.262 |

| CKD | |||||||

| No | 2748 | 0.944 (0.832, 1.073) | 1.166 (1.069, 1.272) | 0.024 | 1.001 (0.816, 1.227) | 1.186 (1.018, 1.382) | 0.273 |

| Yes | 1229 | 0.812 (0.681, 0.969) | 1.163 (1.098, 1.232) | 0.001 | 0.783 (0.614, 0.998) | 1.241 (1.137, 1.354) | 0.003 |

| BMI | |||||||

| < 25 | 861 | 0.912 (0.756, 1.099) 0.3326 | 1.178 (1.055, 1.316) | 0.047 | 0.919 (0.696, 1.212) 0.5497 | 1.283 (1.078, 1.526) | 0.087 |

| 25–30 | 1307 | 0.902 (0.761, 1.068) 0.2297 | 1.165 (1.069, 1.269) | 0.024 | 0.966 (0.738, 1.265) 0.8042 | 1.280 (1.116, 1.467) | 0.123 |

| > = 30 | 1809 | 0.859 (0.715, 1.034) 0.1075 | 1.179 (1.104, 1.260) < 0.0001 | 0.006 | 0.789 (0.606, 1.028) 0.0797 | 1.214 (1.089, 1.355) 0.0005 | 0.013 |

| Diabetes | |||||||

| No | 2268 | 0.914 (0.792, 1.054) 0.2155 | 1.121 (1.041, 1.207) 0.0024 | 0.029 | 0.904 (0.725, 1.128) 0.3727 | 1.195 (1.064, 1.342) 0.0026 | 0.059 |

| Yes | 1709 | 0.914 (0.792, 1.055) 0.2196 | 1.191 (1.121, 1.264) < 0.0001 | 0.004 | 0.857 (0.698, 1.054) 0.1431 | 1.271 (1.156, 1.397) < 0.0001 | 0.004 |

| Hypertension | |||||||

| No | 850 | 0.924 (0.735, 1.163) 0.5023 | 1.250 (1.113, 1.406) 0.0002 | 0.047 | 0.836 (0.582, 1.200) 0.3306 | 1.344 (1.112, 1.624) 0.0022 | 0.048 |

| Yes | 3127 | 0.891 (0.797, 0.997) 0.0443 | 1.154 (1.096, 1.215) < 0.0001 | < 0.001 | 0.894 (0.756, 1.056) 0.1870 | 1.226 (1.131, 1.330) < 0.0001 | 0.004 |

When analyzing subgroup variables, age, sex, smoking status, alcohol consumption, BMI, CKD, diabetes, and hypertension were adjusted in addition to the variables themselves.

*HRs are the relative risk per 1 mg/dL increment of serum uric acid.

Discussion

In this large-sample study, we revealed that SUA is an independent prognostic factor for the risk of ACM and CVM in patients with CVD. In CVD,we also discovered U-shaped associations between SUA and ACM and CVM, implying that lower SUA levels were significantly associated with higher ACM and CVM within a certain range Additionally, among individuals with CVD who also had CKD, the relationships between ACM and CVM with SUA remained nonlinear.

Some of the previous studies have shown similar results to ours, suggesting a U- or J-shaped association between SUA and CVM8,13. An older population in Taipei (age ≥ 65) in a longitudinal cohort study showed a U-shaped relationship between SUA, ACM, and CVM. In Taiwan, it was discovered that an SUA of ≥ 8 mg/dL or < 4 m/dL was an independent predictor of an elevated risk of ACM and CVM in the elderly. Furthermore, among individuals with SUA < 4 mg/dL, mild malnutrition status (defined as Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index < 98, serum albumin < 38 g/L, or BMI < 22 kg/m2) was linked to a higher risk of ACM and CVM8.The results of this study confirmed that, when increased levels of SUA were above the threshold, they were positively correlated with older adults’ risk of ACM and CVM, but when they were below the threshold, they were no longer correlated with older adults’ risk of death. Lihua Hu et al. used a data set that included 10,477 adults aged 18–80 years and found that both low and high SUA levels were associated with higher mortality from ACM, CVM, and respiratory disease mortality, as well as a U-shaped relationship with ACM11. An overall SUA of 5.7 mg/dL may be deemed safe for ACM. Hsu et al. observed that patients undergoing hemodialysis would be more likely to die if their SUA levels were in the lowest or highest quintiles14. In contrast, Wen Zhang et al. used data from the Evidence for Cardiovascular Prevention in Observational Cohorts in Japan (EPOCH-JAPAN study) and discovered that the group with the highest quintile of SUA had a higher risk of CVM in a population of Japanese men and women without a history of stroke, coronary heart disease, or cancer at baseline. A U-shaped relationship between the levels of ACM, CVM, and SUA in Chinese men was recently observed15. However, this study was limited by the lack of important covariates such as lipids, glycosylated hemoglobin, smoking, alcohol consumption, and platelet count. In addition, the study did not explore the nonlinear association between SUA, ACM, and CVM. Our study used the RCS to find a nonlinear relationship between SUA ACM and CVM. And, after adjusting for important confounders, we also found U-shaped associations. Thresholds for SUA varied by outcome event. The thresholds corresponding to ACM and CVM were 5.49 mg/dL and 5.64 mg/dL, respectively. The majority of studies have only shown that high levels of SUA are associated with an increased risk of mortality7,8,13,16–20, but it is unclear whether hyperuricemia is a risk factor for the development of CVD21. Some studies, however, disagree with the findings of the present study, showing no association between SUA and ACM and CVM22,23 and no causal relationship between elevated SUA levels and the risk of developing heart failure24. The reasons for these contradictory results may be due to differences in study populations, cohort study characteristics, sample size, and adjustment for confounders. Moreover, SUA levels were categorized differently in these studies.

Two piecewise Cox regression models were used to calculate the connection between SUA ACM and CVM. The results showed that, for patients with CKD, the associations between SUA, CVM, and ACM remained nonlinear. The results might serve as a reference for the SUA risk level and the prognosis of patients with CKD. In fact, increased SUA levels were significantly associated with mortality, regardless of CKD25. Several past studies have reported that elevated SUA levels are associated with the development26–29 or progression of CKD30,31. During a long-term follow-up, Weiner DE et al.27 showed that higher SUA levels were an independent risk factor for the development of renal illness in the US general population. Similarly, a cohort study in a Chinese population found that elevated SUA levels independently predicted the risk of new-onset CKD29. In addition, a study32 by Sankar D. Navaneethan and others noted a significant correlation between high UA levels and mortality in a population without a history of CKD, even after adjusting for confounding factors such as comorbidities and metabolic syndrome. Notably, in non-CKD patients, it has been shown that UA-lowering therapy at baseline SUA levels of 8 mg/dL or lower is associated with an increased risk of new-onset CVD instead33. SUA levels are usually elevated in patients with CKD and may be related to the fact that approximately 2/3 of SUA is excreted from the kidneys1. In addition, elevated SUA may cause direct renal toxicity30. Kohagura K. et al. provided evidence that SUA is associated with small renal artery damage34. The strong association between the occurrence of CVD and CKD may be owing to the prevalence of traditional cardiovascular risk factors in patients with CKD. Studies have shown that conventional cardiovascular risk factors for atherosclerotic vascular disease play an important role in the early stages of CKD35,36. Risk factors such as hypertension, dyslipidemia, and smoking contribute to the progression of CKD through their effects on the renal vasculature37. However, there are also studies with opposite results. A large cohort study of Taiwanese adults did not find a nonlinear U- or J-shaped association between uric acid and new-onset CKD35. However, due to potential variations in study samples, methods, and analyses, additional research is still required to validate this association. The specific mechanisms by which uric acid levels motivate mortality risk remain unclear. High SUA levels may contribute to death in patients with CVD through a combination of mechanisms36,38–41 including oxidative stress, endothelial dysfunction, inflammatory response, RAS system activation, vascular dysfunction, and related genes. According to earlier research, ROS worsens the damage caused by cardiac ischemia/reperfusion by activating the caspase-1 signaling cascade and NLRP3 inflammatory vesicles36. SUA itself leads to endothelial cell inflammation and ROS production. In an experiment based on hyperuricemia-modeling mice, the levels of the renal pro-inflammatory factors IL-1β, IL-12, and IL-18 were dramatically raised38. (P)RR is widely expressed in endothelial cells and induces activation of the RAS system, and studies have confirmed42 that (P)RR plays a key role in vascular inflammation in response to SUA stimulation. In addition to this, a prospective study39 found that the rs7442295 polymorphism of the SCL2A9 gene was associated with SUA levels in patients with angiographically confirmed and clinically stable coronary artery disease. It has been hypothesized that patients with hypouricemia have an increased risk of developing atherosclerotic disease due to decreased antioxidant capacity1,43. Furthermore, malnutrition may be indicated by decreased uric acid levels26,44. In order to fully understand how different SUA levels cause cardiovascular illness, more in vivo and in vitro research is still required.

The main strengths of our study were that it included a large sample of individuals and a long follow-up period, which enhanced the reliability and representativeness of the results. Second, the nonlinear relationship between SUA and mortality was explored using RCS, and the threshold effect analysis of SUA on mortality was observed using a two piecewise Cox proportional risk model. Third, confounders were adjusted, and subgroup analyses were performed to ensure the stability of the results. Meanwhile, the potential limitations of our study should also be noted. First, all individuals were from the NHANES survey, and selection bias may have occurred because those participants without complete data were excluded from the adjusted model. However, for missing covariates, we used multiple interpolations to minimize potential bias due to covariates with missing data being excluded from the data analysis. Second, although we adjusted for several potential confounders in our analyses, we cannot rule out the possibility that SUA was affected by other unknown factors. Third, this study was conducted among patients with cardiovascular disease in the United States. Therefore, the generalizability of the results to other populations, especially Asian populations, requires further validation. Fourth, the small sample size did not allow for a better exploration of the association between SUA and other causes of death. Fifth, we did not adjust for dietary factors and medication history to clarify the effect of nutritional status and medication use on mortality.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we analyzed 3977 participants with CVD from seven cycles of NHANES (2005–2018), revealing that SUA levels are an independent prognostic factor for the risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in CVD patients, supporting a U-shaped association between SUA levels with ACM and CVM with thresholds of 5.49 and 5.64, respectively. And in CVD combined with CKD patients, the association of ACM and CVM with SUA remained nonlinear. Looking forward, further studies are needed to elucidate the actual role and potential biological mechanisms of SUA in ACM and CVM.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Figure S1. Sensitivity analysis for all-cause mortality (A) and cardiovascular mortality (B).

Supplementary Figure S2. Schoenfeld residual plot for all-cause mortality (A) and cardiovascular mortality (B) in model 3.

Acknowledgements

All authors thank the participants and investigators in the NHANES study.

Author contributions

Y.-L.L. conceived and designed the study. Y.-L.L. and K.-X.D. organized all data and analyzed it. Y.-L.L., K.-X.D., X.-B.M., and L.Q. wrote the manuscript and organized the figures. Y.-M.L. reviewed and revised the manuscript. All the authors have agreed to the submission of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was supported by the Key Research and Development Program of Gansu Province [20YF8FA079].

Data availability

The U.S. NHANES data is available online at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The protocols of NHANES were approved by the ethics review board of the National Centre for Health Statistics. All participants provided informed consent. (http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/irba98.htm)

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Johnson, R. J. et al. Is there a pathogenetic role for uric acid in hypertension and cardiovascular and renal disease?. Hypertension41(6), 1183–1190 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yanai, H. et al. Molecular biological and clinical understanding of the pathophysiology and treatments of hyperuricemia and its association with metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular diseases and chronic kidney disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci.22(17), 9221 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gill, D. et al. Urate, blood pressure, and cardiovascular disease: Evidence from mendelian randomization and meta-analysis of clinical trials. Hypertension77(2), 383–392 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li, S. et al. Cohort study of repeated measurements of serum urate and risk of incident atrial fibrillation. J. Am. Heart Associat.8(13), e012020 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson, R. J. et al. Uric acid, evolution and primitive cultures. Semin. Nephrol.25(1), 3–8 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson, R. J., Segal, M. S., Sautin, Y., et al. Potential role of sugar (fructose) in the epidemic of hypertension, obesity and the metabolic syndrome, diabetes, kidney disease, and cardiovascular disease2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Zhang, W., Iso, H., Murakami, Y., et al. Serum uric acid and mortality form cardiovascular disease: EPOCH-JAPAN Study. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Tseng, W. et al. U-shaped association between serum uric acid levels with cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in the elderly: The role of malnourishment. J. Am. Heart Associat.7(4), e007523 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zeng, G. et al. n-3 PUFA poor seafood consumption is associated with higher risk of gout, whereas n-3 PUFA rich seafood is not: NHANES 2007–2016. Front. Nutr.10, 1075877 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Center for Health Statistics (U.S.). National health and nutrition examination survey: analytic guidelines, 1999–2010. In Hyattsville, Maryland: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, (2013).

- 11.Hu, L. et al. U-shaped association of serum uric acid with all-cause and cause-specific mortality in us adults: A cohort study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metabol.105(3), e597–e609 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kamarudin, A. N., Cox, T. & Kolamunnage-Dona, R. Time-dependent ROC curve analysis in medical research: Current methods and applications. BMC Med. Res. Methodol.17(1), 53 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang, R. et al. Elevated serum uric acid and risk of cardiovascular or all-cause mortality in people with suspected or definite coronary artery disease: A meta-analysis. Atherosclerosis254, 193–199 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hsu, S. P. Serum uric acid levels show a “J-shaped” association with all-cause mortality in haemodialysis patients. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant.19(2), 457–462 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang, D. Y. et al. Association between serum uric acid level and mortality in China. Chin. Med. J.134(17), 2073–2080 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cho, S. K. et al. U-shaped association between serum uric acid level and risk of mortality: A cohort study. Arthritis Rheumatol.70(7), 1122–1132 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim, J. Y. et al. Uric acid and risk of cardiovascular disease and mortality: A longitudinal cohort study. J. Korean Med. Sci.38(38), e302 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feng, S. et al. Uric acid levels and all-cause mortality in peritoneal dialysis patients. Kidney Blood Press. Res.37(2–3), 181–189 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao, G. et al. Baseline serum uric acid level as a predictor of cardiovascular disease related mortality and all-cause mortality: A meta-analysis of prospective studies. Atherosclerosis231(1), 61–68 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lamacchia, O. et al. On the non-linear association between serum uric acid levels and all-cause mortality rate in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Atherosclerosis260, 20–26 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sekizuka, H. Uric acid, xanthine oxidase, and vascular damage: Potential of xanthine oxidoreductase inhibitors to prevent cardiovascular diseases. Hypertens. Res.45(5), 772–774 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zalawadiya, S. K. et al. Uric acid and cardiovascular disease risk reclassification: Findings from NHANES III. Eur. J. Prevent. Cardiol.22(4), 513–518 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ong, G., Davis, W. A. & Davis, T. M. E. Serum uric acid does not predict cardiovascular or all-cause mortality in type 2 diabetes: The fremantle diabetes study. Diabetologia53(7), 1288–1294 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.He, Y. et al. Serum uric acid levels and risk of cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes: Results from a cross-sectional study and Mendelian randomization analysis. Front. Endocrinol.14, 1251451 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xia, X. et al. Serum uric acid and mortality in chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Metabolism65(9), 1326–1341 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakagawa, T. et al. Hyperuricemia causes glomerular hypertrophy in the rat. Am. J. Nephrol.23(1), 2–7 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weiner, D. E. et al. Uric acid and incident kidney disease in the community. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol.19(6), 1204–1211 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsao, H. M. et al. Serum urate and risk of chronic kidney disease. Mayo Clinic Proc.98(4), 513–521 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chou, Y. C. et al. Elevated uric acid level as a significant predictor of chronic kidney disease: A cohort study with repeated measurements. J. Nephrol.28(4), 457–462 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kang, D. H. et al. A role for uric acid in the progression of renal disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol.13(12), 2888–2897 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yuan, J., Zhao, J., Qin, Y., et al. Association of serum uric acid with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in chronic kidney disease stages 3–5. Nutr. Metabol. Cardiovasc. Dis., (2024) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Navaneethan, S. D. & Beddhu, S. Associations of serum uric acid with cardiovascular events and mortality in moderate chronic kidney disease. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant.24(4), 1260–1266 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hassan, W. et al. Association of uric acid-lowering therapy with incident chronic kidney disease. JAMA Netw. Open5(6), e2215878 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kohagura, K. et al. An association between uric acid levels and renal arteriolopathy in chronic kidney disease: A biopsy-based study. Hypertens. Res.36(1), 43–49 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang, S. et al. Uric acid and incident chronic kidney disease in a large health check-up population in Taiwan. Nephrology16(8), 767–776 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shen, S. et al. Uric acid aggravates myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury via ROS/NLRP3 pyroptosis pathway. Biomed. Pharmacother. Biomed. Pharmacother.133, 110990 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wilson, P. W. F. et al. Prediction of coronary heart disease using risk factor categories. Circulation97(18), 1837–1847 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu, Y. L. et al. The extract of sonneratia apetala leaves and branches ameliorates hyperuricemia in mice by regulating renal uric acid transporters and suppressing the activation of the JAK/STAT signaling pathway. Front. Pharmacol.12, 698219 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mozzini, C. et al. Serum uric acid levels, but not rs7442295 POLYMORPHISM of SCL2A9 gene, predict mortality in clinically stable coronary artery disease. Curr. Probl. Cardiol.46(5), 100798 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carluccio, E., Coiro, S. & Ambrosio, G. Unraveling the relationship between serum uric acid levels and cardiovascular risk. Int. J. Cardiol.253, 174–175 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pagkopoulou, E. et al. Association between uric acid and worsening peripheral microangiopathy in systemic sclerosis. Front. Med.8, 806925 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang, X. et al. Uric acid induced inflammatory responses in endothelial cells via up-regulating(pro)renin receptor. Biomed. Pharmacother.109, 1163–1170 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ames, B. N. et al. Uric acid provides an antioxidant defense in humans against oxidant- and radical-caused aging and cancer: A hypothesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.78(11), 6858–6862 (1981). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Beberashvili, I. et al. Serum uric acid as a clinically useful nutritional marker and predictor of outcome in maintenance hemodialysis patients. Nutrition31(1), 138–147 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Piercy, K. L. et al. The physical activity guidelines for americans. JAMA320(19), 2020 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure S1. Sensitivity analysis for all-cause mortality (A) and cardiovascular mortality (B).

Supplementary Figure S2. Schoenfeld residual plot for all-cause mortality (A) and cardiovascular mortality (B) in model 3.

Data Availability Statement

The U.S. NHANES data is available online at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm.