Abstract

Wastewater serves as a reservoir for antimicrobial-resistant bacteria. This study revealed the presence of carbapenem-resistant and carbapenemase-producing Gram-negative bacilli (GNB), established clonal relationships among isolates in hospital and municipal wastewater, and identified a high-risk clone in municipal wastewater. A total of 63 isolates of GNB were obtained, with Enterobacterales being the most frequently isolated group (62%). Carbapenemase-producing Lelliottia amnigena, Kluyvera cryocrescens, and Shewanella putrefaciens isolates were documented for the first time in Mexico. The detectableted carbapenemase genes were blaKPC (55%), blaNDM (12%), blaVIM−2 (12%), blaOXA−48 (4%), blaGES (2%), blaNDM−1 (2%), and blaNDM−5 (2%). Clonal relationships were observed among Klebsiella pneumoniae and Enterobacter spp. isolates, and remarkably the high-risk clone Escherichia coli ST361, carrying blaNDM−5, was identified. This study demonstrates that wastewater harbours carbapenem-resistant and carbapenemase-producing bacteria, posing a public health threat that requires epidemiological surveillance.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-76824-w.

Subject terms: Microbiology, Ecology, Environmental sciences

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) recognizes the emergence of antimicrobial-resistant organisms as one of the foremost threats to global health1. In 2019, 1.27 million deaths were directly attributed to Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR)2. The WHO acknowledges that human health is closely linked to animals and the environment. Therefore, it is important to conduct monitoring in different environments to prevent and control AMR1. For this purpose, specific coordinated actions, known as One Health, are needed. One Health refers to an integrated and collaborative approach aimed achieving optimal and sustainable health outcomes for humans, animals, and ecosystems1.

Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales (CRE) pose a significant concern due to the increasing mortality rates. In the USA, CRE are responsible for 1100 deaths and 13,000 infections annually2,3. Notably, Enterobacterales such as E. coli and K. pneumoniae were responsible accountable for over 250,000 deaths each associated with AMR in 20192. The community transmission of CRE is increasing, largely attributed to asymptomatic carriers, and environmental reservoirs of infections; these sources significantly contribute to spread infections4. Carbapenem-resistant in Enterobacterales can occur through various mechanisms, mainly mediated by expression of carbapenemases, enzymes capable of hydrolysing a wide range of beta-lactams5. Carbapenemase-producing CRE (CP-CRE) can spread and be transmitted through colonized animals6, food7, and wastewater8. Wastewater treatment is primarily focused on reducing commensal and pathogenic organisms; therefore, wastewater can serve as a reservoir for the dissemination of bacteria to different environmental compartments8. Monitoring reports on wastewater-based AMR in Mexico are currently scarce, most focusing only on the search for indicator microorganisms of faecal contamination9. This study aims to search for carbapenemase-producing GNB (CP-GNB), also characterize their genotypic profiles to elucidate clonal relationship, investigate high-risk clones and carbapenemases not previously described in hospital and municipal wastewater in Mexico.

Materials and methods

Study sites and sample collection

This study was conducted at three sites located in Mexico City and the metropolitan area. The sampling period was from May to July 2022. Wastewater samples were collected from open drainage systems (canal system) receiving, domestic, industrial, and hospital wastewater.

Site 1 was located in the municipality of Naucalpan de Juárez, State of Mexico (19° 28′ 22.4″ N 99° 13′ 35.3″ W), and site 2 was situated in the municipality of Tultitlán, State of Mexico (19° 37′ 46.9″ N 99° 09′ 54.2″ W). In both cases, a sample was collected every week for a period of 10 weeks. On the other hand, site 3 was positioned in a paediatric hospital to the south of Mexico City (19° 18′ 24.5″ N 99° 11′ 06.1″ W) and two samples of untreated hospital wastewater were obtained from different locations.

A volume of 500 mL of wastewater was collected in sterile plastic bottles, positioned at the middle of the canal, against the flow, and on the surface in accordance with the Mexican sampling standard10. Samples were immediately transported to the laboratory for analysis.

Isolation of GNB

For the isolation of GNB, the following protocol was devised, which included an enrichment step11,12. A volume of 1 mL of wastewater was added to a tube containing 9 mL of tryptic soy broth (TSB) (Becton Dickinson, Cuautitlán Izcalli, Mexico), supplemented with a 10-µg imipenem (IPM) disk (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, USA). The mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. From the enriched culture, serial dilutions up to 10− 4 in 0.85% saline solution were prepared. Subsequently, 100 µL from the 10− 3 and 10− 4 dilutions were plated on MacConkey agar (Becton Dickinson, Cuautitlán Izcalli, Mexico). Following this, two 10 µg IPM disks (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, USA) were placed, and the plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. Individual colonies exhibiting distinct colonial morphology and located in proximity to the imipenem disk were selected.

GNB identification

GNB were identified using MALDI-TOF MS (VITEK®-MS bioMérieux, Marcy-l’Étoile, France). Isolates that were not identified by VITEK®-MS were analysed through 16 S rRNA gene sequencing. DNA extraction was performed using QIAamp® DNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany), and it was employed for all PCR assays. Gene amplification was conducted with universal oligonucleotides13, following previously described protocols14. Amplicons were purified using QIAquick® PCR purification Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) and were subsequently sequenced using an automated method. The obtained sequences were taxonomically classified using the nucleotide Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLASTn)15.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was conducted in Enterobacterales, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Acinetobacter spp. using the disk diffusion method. The following antibiotics were tested: ceftriaxone (CRO) 30 µg, ceftazidime (CAZ) 30 µg (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, USA), piperacillin/tazobactam (TZP) 100/10 µg, cefepime (FEP) 30 µg, aztreonam (ATM) 30 µg, imipenem (IPM) 10 µg, meropenem (MEM) 10 µg, ertapenem (ETP) 10 µg, gentamicin (GM) 10 µg, amikacin (AN) 30 µg, tetracycline (TE) 30 µg, ciprofloxacin (CIP) 5 µg, levofloxacin (LVX) 5 µg, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (SXT) 25 µg, and chloramphenicol (C) 30 µg (Oxoid, Hampshire, Basingstoke, United Kingdom). For Pseudomonas putida and S. putrefaciens isolates, antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed using the automated VITEK-2® system (BioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France). A panel of nine antimicrobials were used: CAZ, CRO, FEP, IPM, MEM, GM, AN, CIP, and SXT. The colistin [(CL) Sigma, Saint Louis, USA] susceptibility testing was performed by the microdilution method. The interpretation of the results was conducted according to the breakpoints established by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI)16. Isolates were classified as multidrug-resistant (MDR) or extensively drug-resistant (XDR) according to Magiorakos et al.17.

Carbapenemase-producers screening

Carbapenemase production in Enterobacterales and P. aeruginosa was assessed using the Modified Carbapenem Inactivation Method (mCIM). The results were interpreted in accordance with the guidelines outlined by the CLSI16.

Beta-lactamase genes detection and sequencing

The presence of beta-lactamase genes was assessed in isolates of Enterobacterales, Pseudomonas spp., Acinetobacter spp., and S. putrefaciens through PCR assays. The assay included primers designed to detect the following beta-lactamase genes: blaKPC, blaIMP, blaVIM, blaGES, blaCTX−M− 1, blaCTX−M− 2, blaCTX−M− 9, blaCTX−M− 8/25, blaDHA, blaLAT, blaACC, blaACT, blaFOX, blaMOX18, blaNDM19, blaOXA− 4820, blaTEM, and blaSHV21 as previously described. Subsequently, the positive products were sequenced by Sanger technology, and analysed using the BLASTx22 database and the BioEdit v. 7.7.1. software (Copyright © 2001-2021Tom Hall) to determine the beta-lactamase subtype.

Molecular typing

Clonal relatedness of Enterobacterales and Pseudomonas spp. isolates was analysed by Pulsed-Field Gel Electrophoresis (PFGE), following previously established methods23. Genomic DNA was digested with the restriction endonuclease XbaI (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Vilnius, Lithuania), and SpeI (New England Biolabs) and the resulting DNA fragments were separated using a CHEF MAPPER system (Bio-Rad, USA). Salmonella enterica serovar Braenderup ATCC BAA-664 served as a molecular size marker. Banding patterns were analysed using Image Lab Software v. 6.1. (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.), and a dendrogram was generated using the Unweighted Pair Method with Arithmetic Mean (UPGMA) algorithm based on the Jaccard index was employed24. PFGE patterns were interpreted according to the Tenover criteria25.

The sequence type (ST) of an E. coli (T3) isolate was determined by Multilocus Sequence Typing (MLST), as previously described26. Alleles and ST were assigned using the PubMLST database27.

Results

Isolation and identification of Gram-negative bacilli

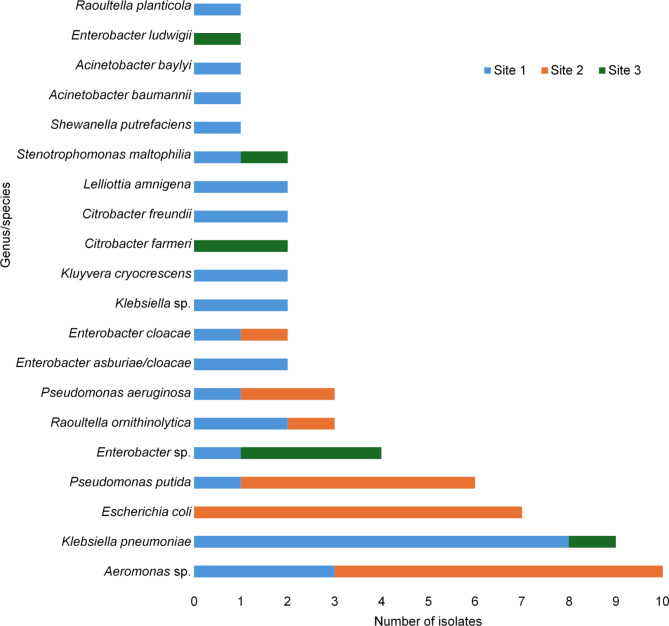

A total of 22 wastewater samples were collected, comprising 10 samples from Site 1 (canal), 10 from Site 2 (canal), and two from Site 3 (hospital wastewater). A total of 63 GNB isolates were obtained. In wastewater from Site 1, thirty-two isolates were retrieved, with K. pneumoniae (n = 8) being the most frequently isolated species. Conversely, in wastewater from Site 2, twenty-three isolates were found, with E. coli (n = 7) prevailing as the most frequently isolated species. Notably, no K. pneumoniae isolates were recovered from wastewater at Site 2, while no E. coli was identified in wastewater at Site 1. For Site 3, eight isolates were obtained, and the predominant genus was Enterobacter (n = 4). Regarding isolates of the genus Aeromonas sp. (n = 10), Klebsiella sp. (n = 2), and Enterobacter sp. (n = 4), species-level identification could not be attained using VITEK®-MS or 16 S rRNA gene sequencing (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Distribution of species obtained from hospital and municipal wastewater. The most frequent genera were Aeromonas and Klebsiella.

Antimicrobial resistance profile of Enterobacterales and non-fermenting gram-negative bacteria

A total of 39 isolates of Enterobacterales were analysed, and susceptibility testing was conducted for 15 antimicrobials. High resistance and intermediate susceptibility to beta-lactams were observed, with 92% (n = 36) of Enterobacterales showing resistant to these antibiotics. All isolates (100%, n = 39) exhibited resistance to the three carbapenems used. In contrast, for CRO, CAZ, FEP, and ATM were 95% (n = 37) resistance rates and for TZP 92% (n = 36) were resistant. High resistance rates were also observed for other antimicrobials, including CIP 95% (n = 37), LVX 72% (n = 28), and SXT 56% (n = 22). However, resistance was relatively low for TE 36% (n = 14), CL 26% (n = 10), GM 26% (n = 10), AN 26% (n = 10), and C 8% (n = 3). All isolates, comprising 100% (n = 39) were classified as MDR. In P. aeruginosa, 100% (n = 3) were resistant to IPM, and MEM; 67% (n = 2); while showed resistance to CIP, and LVX, 33% (n = 1) to ATM and 67% (n = 2) to CL. Only one isolate was classified as MDR. Acinetobacter baumannii isolate was resistant to all tested antimicrobials, except CL classifying it as XDR, while Acinetobacter baylyi exhibited resistance to TZP, CAZ, CRO, IPM, and MEM, but it was intermediate to CL. In P. putida (n = 6) and S. putrefaciens (n = 1), high resistance to IPM 100% (n = 7), MEM 100% (n = 7), CAZ 86% (n = 6), CRO 86% (n = 6), and SXT 71% (n = 5) was observed. Resistance was lower for FEP at 14% (n = 1), and AN at 14% (n = 1), only S. putrefaciens was resistant to CL. All eight isolates were classified as MDR (Table 1).

Table 1.

Antibiotic resistance and beta-lactamase genes in Gram-negative bacilli isolated from hospital and municipal wastewater.

| Genus/species (n) | Number of antibiotics to which it exhibited resistance (antibiotics tested) | mCIM (number of isolates with positive test) | Number of carbapenemases detected (number of isolates) | Detected beta-lactamase genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| K. pneumoniae (n = 9) | 9–14 (16) | 8 | 9 (9) | blaKPC, blaGES−CPS, blaCTX−M−1, blaSHV, blaTEM |

| E. coli (n = 7) | 12 (16) | 7 | 7 (7) | blaNDM−5, blaNDM, blaCTX−M−1 |

| Enterobacter sp. (n = 4) | 9–13 (16) | 4 | 4 (4) |

blaKPC,blaTEM, bla ACT |

| R. ornithinolytica (n = 3) | 4–11 (16) | 3 | 3 (3) | blaKPC, blaOXA−48,blaTEM |

| C. freundii (n = 2) | 10 (16) | 2 | 2 (2) | blaKPC, blaLAT |

| C. farmeri (n = 2) | 11 (16) | 2 | 2 (2) | blaKPC, blaSHV |

| E. asburiae/cloacae (n = 2) | 9–14 (16) | 2 | 2 (2) | blaKPC, blaGES−ESBL, blaACT |

| E. cloacae (n = 2) | 4–10 (16) | 1 | 1 (2) | blaKPC |

| Klebsiella sp. (n = 2) | 12 (16) | 2 | 2 (2) | blaKPC, blaCTX−M−9 |

| K. cryocrescens (n = 2) | 12–15 (16) | 2 | 2 (2) | blaKPC, blaTEM |

| L. amnigena (n = 2) | 11 (16) | 2 | 2 (2) | bla KPC |

| E. ludwigii (n = 1) | 9 (16) | 1 | 1 (1) | blaKPC, blaACT |

| R. planticola (n = 1) | 13 (16) | 0 | 0 (1) | |

| P. putida (n = 6) | 4–6 (10) | NA | 6 (6) | bla VIM−2 |

| P. aeruginosa (n = 3) | 2–6 (10) | 0 | 0 (3) | |

| Acinetobacter spp. (n = 2) | 5–13 (13) | NA | 0 (2) | |

| S. putrefaciens (n = 1) | 6 (10) | NA | 1 (1) | blaNDM−1, blaOXA−48 |

N number of isolates analysed, mCIM modified carbapenem inactivation method, NA not applicable according to CLSI, CPS carbapenemase, ESBL extended spectrum.beta-lactamase.

Carbapenemase producers

A total of 42 isolates, comprising Enterobacterales (n = 39) and P. aeruginosa (n = 3) were evaluated. Among the Enterobacterales, 92% (n = 36) were found to be carbapenemase-producing, while none of the P. aeruginosa isolates tested were positive (Table 1).

Detection of beta-lactamase genes

Molecular analysis was conducted to detect beta-lactamase genes in 51 isolates of Enterobacterales and non-fermenters. Regarding carbapenemase genes, our findings indicate that 55% (n = 28) of the isolates carried blaKPC, 12% (n = 6) blaNDM, 12% (n = 6) blaVIM−2, 4% (n = 2) blaOXA−48, 2% (n = 1) blaNDM−1, 2% (n = 1) blaNDM−5, and 2% (n = 1) blaGES. Notably, KPC carbapenemase gene was detected in different Enterobacterales species, NDM predominated in E. coli, and VIM-2 was only identified in P. putida. Additionally, other beta-lactamase genes were detected, including blaTEM 24% (n = 12), blaCTX−M−1 18% (n = 9), blaACT 12% (n = 6), blaSHV 8% (n = 4), blaCTX−M−9 4% (n = 2), blaLAT 4% (n = 2), and blaGES extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) in 2% (n = 1) of isolates. Remarkably, 82% (n = 32) of Enterobacterales harboured more than one beta-lactamase gene (Table 1).

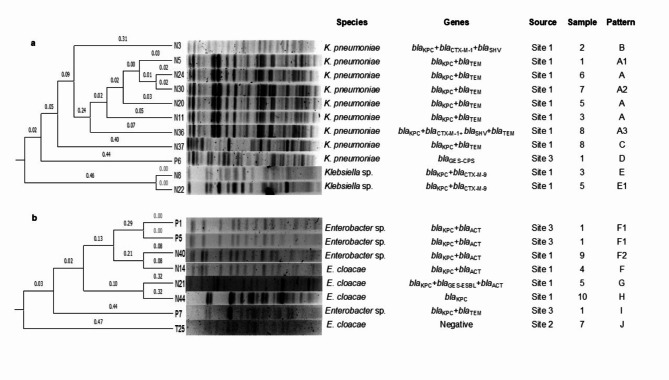

Clonal profile and MLST

PFGE separated K. pneumoniae isolates into four patterns (A–D) with three subtypes (A1, A2, A3), revealing varying gene detections even within the same clone. These patterns differed from those of patterns of Klebsiella sp. (E). Similarly, E. cloacae isolates exhibited four distinct patterns (F, G, H, and J), while Enterobacter sp., one pattern (I) and two subtypes (F1 and F2) were obtained (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Dendrograms based on PFGE patterns after digestion of Klebsiella spp. and Enterobacter spp. with XbaI. (a) Klebsiella spp. (b) Enterobacter spp.

Among isolates of C. farmeri, C. freundii, and L. amnigena, both isolates of each species shared identical patterns (K, L, and M), K. cryocrescens exhibited a single pattern (N) and one subtype (N1). Meanwhile, R. ornithinolytica demonstrated two patterns (O and P) and one subtype (P1) (Supplementary Fig. S1).

In the PFGE analysis of P. aeruginosa, three distinct patterns (R, Q, and S) were observed, while in P. putida, exhibited six patterns (T-Y) (Supplementary Fig. S2). Unpublished results, from PFGE analysis of E. coli isolates indicated an absence of detectable bands. Therefore, we proceeded to analyse one of the isolates by MLST, the allelic profile was adk 10, fumC 99, gyrB 5, icd 91, mdh 248, purA 7 and recA 2 and it was found that the nearest ST were ST361, ST13464, ST15648, the first corresponding to a high-risk clone, it is important to mention that the sequence of the mdh gene had five differences with the mdh 248 allele (180T→129 A, 211G→160 A, 217G→166T, 318G→267 A, 826G→775 A).

Discussion

Wastewater contains coliforms originating from human excreta and bacteria from domestic waste9. Additionally, antimicrobial-resistant bacteria may be present, potentially originating from hospitals, which are known reservoirs of pathogenic organisms28,29. Among the coliform organisms, E. coli, K. pneumoniae, C. freundii, and E. cloacae are included; all of which belong to the Enterobacterales order9.

This study demonstrates the frequency and diversity of Enterobacterales, which constituted the majority of organisms (62%), resistant to carbapenems, recovered from both hospital and municipal wastewater. The most prevalent Enterobacterales isolated from municipal wastewater (canal system) were K. pneumoniae (n = 8), E. coli (n = 7), and Enterobacter spp. (n = 5). The presence of these species in wastewater is consistent with observations in municipal wastewater in Mexico City, where strains of E. coli were isolated30. Similarly, in the USA, Enterobacterales have been obtained from municipal wastewater, with reported species including K. pneumoniae, E. coli, and Citrobacter spp8. In the hospital wastewater of our study, Enterobacter was the most frequent isolate genus (4/8). While Enterobacter has been detected in hospital wastewater in our country, it has been reported with lower frequency in previous studies29. On the other hand, more isolates of carbapenemasas-producing CRE were obtained from the wastewater at Site 1 compared to Site 2. This discrepancy is attributed to the presence of four hospitals around the sampling site, while Site 2 only had one nearby hospital. Hospitals are recognized as significant contributors to the contamination of antimicrobial-resistant bacteria, which persist throughout wastewater treatment processes31. This study underscores the importance of monitoring and addressing the presence and dissemination of bacteria carrying genes associated with carbapenem-resistance in wastewater.

We implemented a method for detecting carbapenem-resistant bacteria, supplemented medium with imipenem facilitated the isolation CP-CRE, with the vast majority harbouring a carbapenemase gene (37/39). Previous reports have highlighted the efficacy of carbapenem enrichment in enhancing the isolation of carbapenemases-producing Enterobacterales from wastewater8.

Rare species of Enterobacterales and other Gram-negative bacilli are emerging as carbapenemase-producers. The emergence of carbapenemases in uncommon species raises concerns regarding the limited understanding of their pathogenicity, posing a challenge for the subsequent control of infections. Species such as L. amnigena and K. cryocrescens are seldom associated with multidrug resistance or carbapenemase production32–34. L. amnigena, previously classified as Enterobacter amnigenus and redefined in 201334, is primarily found in wastewater and food sources35. It has been implicated in various infections, including urinary tract infections, pyelonephritis, and sepsis in immunocompromised patients33. In our study, both isolates of L. amnigena exhibited carbapenem resistant and harboured blaKPC. Notably, blaKPC−2 positive L. amnigena has been isolated from a blood sample of a hospitalized patient in neurosurgery, the isolate carried the gene on a plasmid33, and L. amnigena blaGES positive strain have been identified in community wastewater in Finland35. Similarly, K. cryocrescens considered a sporadic opportunistic pathogen32. To our knowledge, there are only four reports of K. cryocrescens carrying carbapenemase genes. The isolates obtained in this study from K. cryocrescens demonstrated resistance to carbapenems and carried blaKPC and blaTEM genes. In Italy, it was isolated from a stool sample of a hospitalized patient, and it had the blaVIM gene on a IncA plasmid36; in 2019, from hospital wastewater, an isolate with the blaNDM−1 gene was obtained37; again in 2022, from community wastewater in Finland, this species was isolated and was co-carrying blaGES and blaKPC35. The most recent report included a case from Portugal, were a hospitalized patient harboured a MDR K. cryocrescens and the strain co-carried blaKPC−3 and blaNDM−1 genes32.

Shewanella putrefaciens is an uncommon opportunistic pathogen, and its virulence remains incompletely understood38. It is unknown whether it possesses the capacity to acquire resistance mechanisms such as carbapenemase genes. The only report of S. putrefaciens carrying blaOXA−436 and blaNDM−1 was obtained through environmental surface monitoring in a hospital in Pakistan39. In our study, the isolation of S. putrefaciens carried blaOXA−48 and blaNDM−1. Notably, there are not prior reports from Mexico documenting this species in association with carbapenem-resistance.

Carbapenemases-production in Enterobacterales is the most concerning mechanism of resistance to carbapenems, given the easy transmission and dissemination of these genes40. In this study, the most frequent carbapenemase gene was blaKPC at 55% (n = 28/51) of Enterobacterales isolated from both hospital and municipal wastewater samples. Similar prevalence rates of blaKPC have been reported in community wastewater in the USA, with a frequency of 78%8. In Brazil, blaKPC was detected in 20% of hospital and municipal wastewater isolates among 34 Enterobacterales strains41. Conversely, in Finland, was the most frequent detected carbapenemase gene in Enterobacterales, blaGES (n = 25), with blaKPC (n = 6) less commonly observed in municipal wastewater35. In hospital wastewater in Germany, blaOXA−48 predominated as the most frequent carbapenemase gene42. In Mexico City, blaKPC was detected in Klebsiella spp. and E. coli isolates from both treated and untreated hospital wastewater28,29, indicating the circulation of blaKPC in this setting. Moreover, these wastewater sources were found to harbour various types of beta-lactamase genes, including ESBLs and AmpC.

In this study, blaNDM was additionally detected in 14% predominantly in E. coli (n = 7). However, one isolate was characterized as carrying, the blaNDM−5 variant. This finding aligns with a previous report of blaNDM−5 producing E. coli strains from municipal wastewater in Mexico City30, indicating the dissemination of this carbapenemase variant.

In addition, molecular typing of one E. coli isolate using MLST, and revealed the nearest ST361. To confirm this information, it is necessary to submit the complete genome to PubMLST to determine whether it is a new ST; however, this clone has characteristics common to high-risk clone such as the production of NDM-5. This clone is recognized as a high-risk clone (along with ST167, ST405, ST410, ST648) associated with rapid global dissemination and multidrug resistance. ST361 has been reported in various European countries, including Germany, Denmark, Finland, France, Ireland, Norway, Sweden, and the Netherlands, predominantly isolated from nosocomial infections (8%)43. Remarkably, E. coli ST361 has also been identified in humans and pig faecal samples, where harboured resistance genes including blaCARB−2 and blaTEM6, continuous surveillance is crucial to prevent the spread of NDM-5-producing E. coli ST361.

Conclusions

Hospital and municipal wastewater in Mexico City and the metropolitan area serve as reservoirs for CRE and other Gram-negative bacteria, some of which are carbapenemase-producers. Enterobacterales carry genes encoding carbapenemases, ESBL, and AmpC, conferring them resistance to the entire spectrum of beta-lactam antibiotics tested in this study.

This research represents the first documentation of diverse clonal types of carbapenemase-producing L. amnigena, K. cryocrescens, and S. putrefaciens. Furthermore, it is the second instance of NDM-5-producing E. coli identified in wastewater in Mexico. These findings underscore the significance of hospital and municipal wastewater as reservoirs for carbapenem-resistant bacteria, the critical need for continuous surveillance of AMR.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

MMU-A, AA-A, JAC-V, and G.A-O conceived and planned the experiments. MMU-A, JM-V, LB-M, and AJ-A carried out the experiments and contributed with the bioinformatic. AA-A, JAC-V, and G.A-O took the lead in writing the manuscript. M.M.U-A., A.A-A., J.A.C-V., J.M.-V., R.M.R-A., L.B-M., A.J-A., and G.A-O. provided critical feedback, contributed to the interpretation of the results, and helped shape the research, analysis, and manuscript.

Funding

This study was financed by IPN with the following grant numbers SIP20231999, SIP20232124, SIP20232106, and SIP20232094. M.M.U.A. is a PhD student with a scholarship from CONAHCYT.

Data availability

Sequence data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in the NCBI. Data is provided within the supplementary information files: GenBank accession numbers for nucleotide sequences: SUB14263991 N8-16 S PP377866SUB14263991 N10-16 S PP377867SUB14263991 N15-16 S PP377868SUB14263991 N16-16 S PP377869SUB14263991 N22-16 S PP377870SUB14263991 N43-16 S PP377871SUB14263991 N44-16 S PP377872SUB14263991 N45-16 S PP377873SUB14263991 T4-16 S PP377874SUB14263991 T6-16 S PP377875SUB14263991 T40-16 S PP377876SUB14263991 T25-16 S PP377877SUB14263991 P1-16 S PP377878SUB14263991 P5-16 S PP377879SUB14263991 P9-16 S PP377880BankIt2799564 P6-GES PP384147BankIt2799561 N31-NDM-1 PP384148BankIt2799560 N21-GES PP384149BankIt2799554 T3-recA PP384150BankIt2799554 T3-purA PP384151BankIt2799554 T3-mdh PP384152BankIt2799554 T3-icd PP384153BankIt2799554 T3-gyrB PP384154BankIt2799554 T3-fumC PP384155BankIt2799554 T3-adk PP384156BankIt2799554 T3-NDM-5 PP384157BankIt2799562 N16-VIM-2 PP384158BankIt2799562 T11-VIM-2 PP384159BankIt2799562 T21-VIM-2 PP384160BankIt2799562 T32-VIM-2 PP384161BankIt2799562 T33-VIM-2 PP384162BankIt2799562 T41-VIM-2 PP384163.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Juan Arturo Castelan-Vega, Email: jcastelv@ipn.mx.

Gerardo Aparicio-Ozores, Email: gaparico@ipn.mx.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Antimicrobial resistance (2023). https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/antimicrobial-resistance

- 2.Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: A systematic analysis. Lancet. 399, 629–655 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2019 AR Threats Report. (2021). https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/biggest-threats.html

- 4.Tompkins, K. & van Duin, D. Treatment for carbapenem-resistant enterobacterales infections: Recent advances and future directions. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis.40, 2053–2068 (2021). 10.1007/s10096-021-04296-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Caliskan-Aydogan, O. & Alocilja, E. C. A review of carbapenem resistance in enterobacterales and its detection techniques. Microorganisms. 11, 1491 (2023). 10.3390/microorganisms11061491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Messele, Y. E. et al. Phylogenetic analysis of Escherichia coli isolated from australian feedlot cattle in comparison to pig faecal and poultry/human extraintestinal isolates. Antibiotics. 12, 895 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abdallah, H. M. et al. Extended-spectrum β-lactamases and/or carbapenemases-producing enterobacteriaceae isolated from retail chicken meat in Zagazig, Egypt. PLoS ONE. 10, e0136052 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Too, R. J. et al. Frequency and diversity of carbapenemaseproducing Enterobacterales recovered from untreated wastewater impacted by selective media containing cefotaxime and meropenem in Ohio, USA. PLoS ONE. 18, e0281909 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mazari-Hiriart, M. et al. Microbiological implications of periurban agriculture and water reuse in Mexico City. PLoS ONE. 3, e2305 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.SECRETARIA DE COMERCIO Y FOMENTO INDUSTRIAL & Norma Mexicana NMX-AA-003-1980, Cuerpos receptors-Muestreo Diario Oficial de la Federacion (1980). www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/166762/NMX-AA-003-1980.pdf

- 11.Nordmann, P. et al. Identification and screening of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Clin. Microbiol. Infect.18, 432–438 (2012). 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03815.x [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Lolans, K., Calvert, K., Won, S., Clark, J. & Hayden, M. K. Direct ertapenem disk screening method for identification of KPC-producing klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli in surveillance swab specimens. J. Clin. Microbiol.48, 836–841 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Relman, D. A. The search for unrecognized pathogens. Science. 284, 1308–1310 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aquino-Andrade, A., Merida-Vieyra, J., Lara-Hernandez, A., Hernandez-Orozco, H. & De Colsa-Ranero A. Tipificación De aislamientos de Ralstonia mannitolilytica en un hospital pediátrico de la Ciudad De México. Acta Pediatr. Méx.43, 73–78 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang, Z., Schwartz, S., Wagner, L. & Miller, W. A greedy algorithm for aligning DNA sequences. J. Comput. Biol.7, 203–214 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. 34th ed. CLSI supplement M100. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; (2024).

- 17.Magiorakos, A. P. et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: An international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect.18, 268–281 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dallenne, C., da Costa, A., Decré, D., Favier, C. & Arlet, G. Development of a set of multiplex PCR assays for the detection of genes encoding important β-lactamases in Enterobacteriaceae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother.65, 490–495 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nordmann, P., Poirel, L., Carrër, A., Toleman, M. A. & Walsh, T. R. How to detect NDM-1 producers. J. Clin. Microbiol.49, 718–721 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brink, A. J. et al. Emergence of OXA-48 and OXA-181 carbapenemases among Enterobacteriaceae in South Africa and evidence of in vivo selection of colistin resistance as a consequence of selective decontamination of the gastrointestinal tract. J. Clin. Microbiol.51, 369–372 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alcantar-Curiel, D. et al. Nosocomial bacteremia and urinary tract infections caused by extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae with plasmids carrying both SHV-5 and TLA-1 genes. Clin. Infect. Dis.38, 1067–1074 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Altschul, S. F. et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: A new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res.25, 3389–3402 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Modified Pulse-Net Procedure for Pulsed-Field Gel Electrophoresis of Select Gram Negative Bacilli (2014). https://www.cdc.gov/hai/pdfs/labsettings/Modified-PulsedNet-procedure-GNB.pdf

- 24.Garcia-Vallvé, S., Palau, J. & Romeu, A. Horizontal gene transfer in glycosyl hydrolases inferred from codon usage in Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Biol. Evol.16, 1125–1134 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tenover, F. C. et al. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: Criteria for bacterial strain typing. J. Clin. Microbiol.33, 2233–2239 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wirth, T. et al. Sex and virulence in Escherichia coli: An evolutionary perspective. Mol. Microbiol.60, 1136–1151 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jolley, K. A., Bray, J. E. & Maiden, M. C. J. Open-access bacterial population genomics: BIGSdb software, the PubMLST.org website and their applications. Wellcome Open. Res.3, 124 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Galarde-López, M. et al. Surveillance of antimicrobial resistance in hospital wastewater: Identification of carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella spp. Antibiotics (Basel). 11, 238 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Galarde-López, M. et al. Antimicrobial resistance patterns and clonal distribution of E. Coli, Enterobacter spp. and Acinetobacter Spp. Strains isolated from two Hospital Wastewater plants. Antibiotics (Basel). 11, 601 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lüneberg, K. et al. Metallo-beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli in the sewage of Mexico City: Where do they come from? Can. J. Microbiol.68, 139–145 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aristizabal-Hoyos, A. M., Rodríguez, E. A., Torres-Palma, R. A. & Jiménez, J. N. Concern levels of beta-lactamase-producing Gram-negative bacilli in hospital wastewater: Hotspot of antimicrobial resistance in Latin-America. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis.105, 115819 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Loiodice, M., Ribeiro, M., Peixe, L. & Novais, Â. Emergence of NDM-1 and KPC-3 carbapenemases in Kluyvera cryocrescens: Investigating genetic heterogeneity and acquisition routes of blaNDM-1 in Enterobacterales species in Portugal. J. Glob. Antimicrobl. Resist.34, 195–198 (2023). 10.1016/j.jgar.2023.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Sheng, J. F. et al. blaKPC and rmtB on a single plasmid in Enterobacter amnigenus and Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from the same patient. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis.31, 1585–1591 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Birlutiu, V., Birlutiu, R. M. & Dobritoiu, E. S. Lelliottia amnigena and Pseudomonas putida coinfection associated with a critical SARS-CoV-2 infection: A case report. Microorganisms. 11, 2143 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tiwari, A. et al. Wastewater surveillance detected carbapenemase enzymes in clinically relevant gram-negative bacteria in Helsinki, Finland; 2011–2012. Front. Microbiol.13, 2011–2012 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gaibani, P. et al. A novel IncA plasmid carrying blaVIM-1 in a Kluyvera cryocrescens strain. J Antimicrob Chemother.73, 3206–3208 Preprint at (2018). 10.1093/jac/dky304 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Li, Y. et al. Characterization of a carbapenem-resistant Kluyvera cryocrescens isolate carrying blandm-1 from hospital sewage. Antibiotics (Basel). 8, 149 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Benaissa, E., Abassor, T., Oucharqui, S., Maleb, A. & Elouennass, M. Shewanella putrefaciens: A cause of bacteremia not to neglect. IDCases. 26, e01294 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Potter, R. F. et al. Draft genome sequence of the blaOXA-436- and blaNDM-1- harboring Shewanella putrefaciens SA70 isolate. Genome Announc.5, e00644 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Teban-Man, A. et al. Municipal wastewaters carry important carbapenemase genes Independent of Hospital Input and can Mirror Clinical Resistance patterns. Microbiol. Spectr.10, e0271121 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zagui, G. S. et al. Gram-negative bacteria carrying β-lactamase encoding genes in hospital and urban wastewater in Brazil. Environ. Monit. Assess.192, 376 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carlsen, L. et al. High burden and diversity of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales observed in wastewater of a tertiary care hospital in Germany. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health. 242, 113968 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Linkevicius, M. et al. Rapid cross-border emergence of NDM-5-producing Escherichia coli in the European Union/European Economic Area, 2012 to June 2022. Euro. Surveill. 28, 2300209 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Sequence data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in the NCBI. Data is provided within the supplementary information files: GenBank accession numbers for nucleotide sequences: SUB14263991 N8-16 S PP377866SUB14263991 N10-16 S PP377867SUB14263991 N15-16 S PP377868SUB14263991 N16-16 S PP377869SUB14263991 N22-16 S PP377870SUB14263991 N43-16 S PP377871SUB14263991 N44-16 S PP377872SUB14263991 N45-16 S PP377873SUB14263991 T4-16 S PP377874SUB14263991 T6-16 S PP377875SUB14263991 T40-16 S PP377876SUB14263991 T25-16 S PP377877SUB14263991 P1-16 S PP377878SUB14263991 P5-16 S PP377879SUB14263991 P9-16 S PP377880BankIt2799564 P6-GES PP384147BankIt2799561 N31-NDM-1 PP384148BankIt2799560 N21-GES PP384149BankIt2799554 T3-recA PP384150BankIt2799554 T3-purA PP384151BankIt2799554 T3-mdh PP384152BankIt2799554 T3-icd PP384153BankIt2799554 T3-gyrB PP384154BankIt2799554 T3-fumC PP384155BankIt2799554 T3-adk PP384156BankIt2799554 T3-NDM-5 PP384157BankIt2799562 N16-VIM-2 PP384158BankIt2799562 T11-VIM-2 PP384159BankIt2799562 T21-VIM-2 PP384160BankIt2799562 T32-VIM-2 PP384161BankIt2799562 T33-VIM-2 PP384162BankIt2799562 T41-VIM-2 PP384163.